ARCHIVE

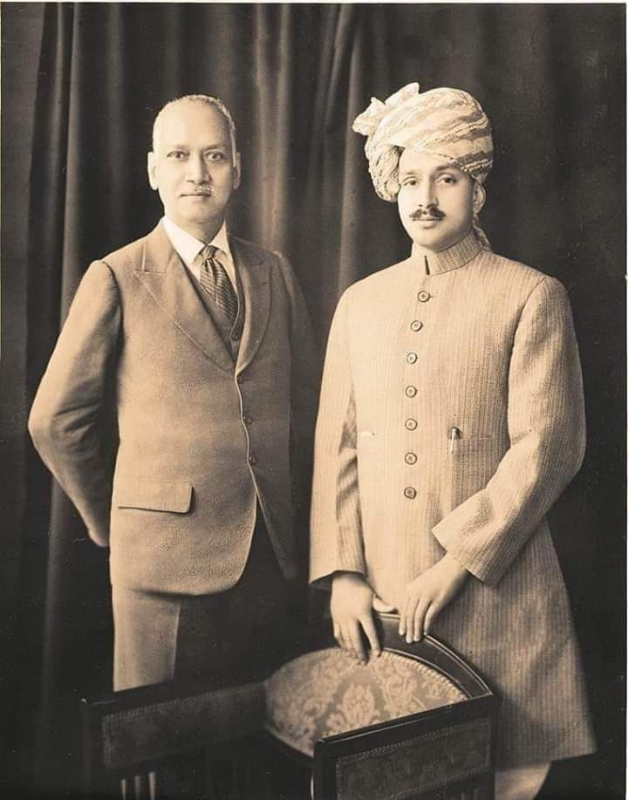

RAGHUBIR SINH

A Princely Historian

Far removed from the middle–class origins and professional careers of Sarkar and Sardesai is the third actor in this history. Raghubir Sinh — heir to the princely state of Sitamau, located in the patchwork of princely states aggregated by the colonial state in the mid–nineteenth century as the Central India Agency. As such kingdoms went, Sitamau was not small — its ruler bore the title of His Highness and Raja and was entitled to a salute of eleven guns. Within its boundaries of some 350 sq. miles were ninety-three villages. The kingdom of Sitamau had come into being at the end of the seventeenth century, founded by a cadet branch of Rathor Rajputs from Ratlam — which in turn had been founded by Ratan Singh, a descendent of the ruling clan of Jodhpur.

The Rajput ruling houses of Ratlam and Jodhpur thus defined one aspect of Sitamau’s geographical and political environment. The state was also bordered by the large princely states of Gwalior and Indore — founded respectively by the powerful Maratha clans of the Scindias and the Holkars. Sitamau, from the late eighteenth century, had passed into the control of Scindia’s armies and it was a tributary to Gwalior until the appearance of the British on the scene who established a new paramountcy.

The princely state of Indore was Sitamau’s major neighbour and Indore city its closest major urban centre. Sitamau’s history is, therefore, permeated by all the friction of Maratha—Rajput interface that informed so much of Raghbir Sinh’s scholarship and historical research. Much of what Sarkar and Sardesai researched in the fall of the Mughals and the rise of the Marathas and the final extinction of both powers, formed Sinh’s personal inheritance — in terms of family and clan history.

Raghubir Sinh was born in Sitamau in February 1908, the eldest son of the ruler, Raja Sir Ram Singh. His early studies were at the Daly College, Indore, and thereafter at the Baroda High School. Unusually for a ruling prince, he went on to study further — a BA and thereafter a law degree from the Agra University — and taught at the Sitamau high school before securing an MA in history also from the Agra University. What explained this professional and middle–class trajectory for a scion of a ruling house in central India? Raghubir Sinh was often to be asked this question and he would relate the tradition of literature and poetry for which Sitamau rulers had achieved some local distinction. One of his ancestors was thus named as a friend by Suryamal Mishran, the author of Vansh Bhaskar, an important early–nineteenth–century chronicle of the Hada Rajputs of Bundi. His father, Maharaja Sir Ram Singh, too took pride in being a poet and encouraged others including his children in literary activity. Incidentally, he would personally teach English to his children.

Raghubir Sinh was born in Sitamau in February 1908, the eldest son of the ruler, Raja Sir Ram Singh. His early studies were at the Daly College, Indore, and thereafter at the Baroda High School. Unusually for a ruling prince, he went on to study further — a BA and thereafter a law degree from the Agra University — and taught at the Sitamau high school before securing an MA in history also from the Agra University.

Yet, notwithstanding these literary traditions, it was an external event that focused Ram Singh’s attention on the future of the Indian princes and in particular how his sons would manage without a kingdom. This event was the Russian Revolution and the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas. On the afternoon this news came, Sinh recollected that he had found his father worried and somewhat bewildered. He did not begin the customary English tuition but instead spoke about the earlier revolutions in France and England and the fates that had met Louis XVI and Charles I. He then said: ‘At the moment everything is quiet in India but no one knows what the future holds and it is possible that the princely states will face great change and they may well come to an end. It is therefore essential that each of you should be fully educated and learn to stand on your own feet.’

In Raghubir Sinh’s account, doing a BA and then obtaining a law degree was thus chartered out for him then, but his father’s prescience extended to his other progeny also and became a tradition for the Sitamau ruling family. Raghubir Sinh’s own children and grandchildren too were to lead lives in different vocations and careers including the civil services and the corporate world. Their family inheritance has, unlike many other erstwhile princely families of India, not been treated as an asset but as a tradition. Raghubir Sinh gave early evidence of what was to become a lifelong interest in historical research, and history. While still a young man of twenty–two and possibly with little historical training, his first book Poorva Madhyakalin Bharat (Pre–Medieval India), was written in 1930 and published in 1931. It, he reminisced later, enjoyed a brief success largely because there were not many such works then available in Hindi. The book is intended as a reflective look at the Delhi Sultanate — and is novel to the extent it looks at that period of history not in dynastic terms but in terms of broader social and military trends.

Raghubir Sinh subdivided the sultanate history into five themes: Military Rule (1206—94), Progressive Governance (1254—1351); Religious Governance (1251—1388); Period of Weak Governance and Instability (1388—1450); and, Feudal Dominated Government (1450—1526). Such a conceptual disaggregation was intended to provide an overview of sultanate history consciously different from more conventional approaches exemplified by Ishwari Prasad’s History of Medieval India — published in 1925 and which remained for decades later the standard work. Raghubir Sinh’s book shows the author as a serious young man who was embarking on a study of history with high motives. The opening sentence of the book is a quote from Leibnitz, ‘The present began in the past.’ But more novel are the reasons that he advanced for writing the book:Raghubir Sinh gave early evidence of what was to become a lifelong interest in historical research, and history. While still a young man of twenty–two and possibly with little historical training, his first book Poorva Madhyakalin Bharat (Pre–Medieval India), was written in 1930 and published in 1931. It, he reminisced later, enjoyed a brief success largely because there were not many such works then available in Hindi.

Sarkar gave a strong endorsement to Raghubir Sinh’s book in the form of a testimonial:

Yet despite such a strong recommendation from India’s greatest living historian and notwithstanding being prescribed as a text in the Banaras Hindu University and the Nagpur University, the book faded away quickly. A separate story, however, surrounds how Sarkar wrote this recommendation for it, although it was written after Poorva Madhyakalin Bharat was published. Possibly, it was at Raghubir Sinh’s request to establish its worth. He reminisced years later that the acquaintance of the historian with the Sitamau rulers began in 1926 when a difference of opinion arose on a sanad granted by Aurangzeb to Keshav Das, the founder of the Sitamau state. Sarkar studied the available documentation and gave an opinion that settled these disputes. Raghubir Sinh, however, maintained contact with Sarkar thereafter and this possibly explains the endorsement. Sinh was also to recall that his teacher in Agra, J.C. Taluqdar, also introduced him to Sarkar as a possible research student.

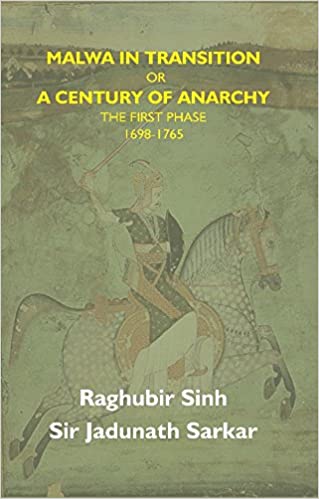

Following a brief visit to Sitamau by Sarkar and his family in October 1934 the relationship crystallized with Sarkar agreeing to act as research guide for Raghubir Sinh’s DLitt. thesis. This resulted in Sinh’s best known work, Malwa in Transition. Sarkar himself does not appear to have required much encouragement in accepting Sinh as a student — the idea of guiding the research efforts of the scion of a Rajput state would have been appealing and despite almost a forty–year age gap between the two, a close relationship developed which is apparent from even a cursory reading of their letters. Incidentally, Sarkar, during his visit to Sitamau, was accompanied by his wife, two daughters, a son–in–law and a servant and he was travelling to Ujjain after visiting the battlefield at Haldighati and the fort complex at Chittorgarh, en route. Sitamau was on the way as Sarkar was also visiting Fatehabad, where a major battle between Aurangzeb’s and Shah Jahan’s armies — the battle of Dharmat — took place in 1658.

Following a brief visit to Sitamau by Sarkar and his family in October 1934 the relationship crystallized with Sarkar agreeing to act as research guide for Raghubir Sinh’s DLitt. thesis. This resulted in Sinh’s best known work, Malwa in Transition. Sarkar himself does not appear to have required much encouragement in accepting Sinh as a student — the idea of guiding the research efforts of the scion of a Rajput state would have been appealing and despite almost a forty–year age gap between the two, a close relationship developed which is apparent from even a cursory reading of their letters.

Raghubir Sinh was once asked whether his princely status meant any special privileges or treatment from Sarkar. He had reminisced:

The history of Malwa, the region in which Sitamau is located, in the eighteenth century was Raghubir Sinh’s chosen subject. ‘It is,’ Sarkar wrote to the young prince in March 1934, ‘a fascinating subject, but the difficulty of writing it is no less than its interest.’ The difficulty arose ‘… from the interplay of an immense and complicated variety of races and forces and the lack of written records. … Your task can best be likened to the work of a jeweller also in reconstructing a mosaic which has been shivered into bits and some components/parts of which are missing.’ Sarkar’s advice was characteristic: ‘Collect the extant traditions … of important families (or clans) and of towns too in different parts of Malwa.’ Again, ‘I have always told my research students that a general knowledge is absolutely necessary even for a specialised study and that they must read not only in but also about their chosen subject.’ The initial reading list forwarded by Sarkar included works in Urdu, Persian and Marathi, apart from in English, and contained also the advice that Sinh had to gradually improve his skills in all these languages.

Jadunath’s advice and assistance was that of the research guide of a doctoral student and extended from suggesting lists of primary sources, help in obtaining manuscript resources from the British library, as also loaning manuscripts from his own collection. From 1933 to end of 1935, correspondence between the two concerned the minutiae of manuscript sources to establish the chronology and main developments in Malwa in Sinh’s chosen period of study. Sarkar’s own experience of researching in the backwater of Patna without access to a research library and having to rely on a personal network to tap manuscript sources, clearly informs his guidance of Sinh in even more obscure Sitamau. Sarkar’s advice and assistance stand out and explain much of the close relationship that developed between the two:The history of Malwa, the region in which Sitamau is located, in the eighteenth century was Raghubir Sinh’s chosen subject. ‘It is,’ Sarkar wrote to the young prince in March 1934, ‘a fascinating subject, but the difficulty of writing it is no less than its interest.’ The difficulty arose ‘… from the interplay of an immense and complicated variety of races and forces and the lack of written records. … Your task can best be likened to the work of a jeweller also in reconstructing a mosaic which has been shivered into bits and some components/parts of which are missing.’

On another occasion:

Sinh was fortunate that his guide also had a converging interest in the first half of the eighteenth century and that there was so much overlap of manuscript sources. In 1933 and 1934 Sarkar himself was engaged with Volume II of his Fall of the Mughal Empire which dealt with the period 1754 to 1771 covering Maratha expansion in the north, the battle of Panipat and developments thereafter in Delhi, Rajasthan and Punjab. Some of this, therefore, overlapped with the broad coverage of Raghubir Sinh’s study of Malwa.

Sarkar’s guidance also extended to the drafting of the thesis and to all matters of style and presentation. Thus, as Sinh began writing, his guide wrote: ‘Avoid verbosity by all means, adhere to a methodical arrangement of the matters of fact; terseness of expression and citation of authority should characterise every chapter. Leave reflections to the concluding paragraphs of each chapter or to a separate chapter.’

We also have Sarkar commenting on an early draft of some of the chapters of the thesis:

There are also numerous advisories regarding correct grammar and style:

Writing style was very clearly a passion with Sarkar. Over a decade before correcting Sinh’s errors he had written:

Sinh was fortunate that his guide also had a converging interest in the first half of the eighteenth century and that there was so much overlap of manuscript sources. In 1933 and 1934 Sarkar himself was engaged with Volume II of his Fall of the Mughal Empire which dealt with the period 1754 to 1771 covering Maratha expansion in the north, the battle of Panipat and developments thereafter in Delhi, Rajasthan and Punjab.

When the thesis was nearing completion in early 1936, Sarkar arranged for Nirad Chaudhuri, later to be a well–known writer, to proofread the draft. Nirad Chaudhuri was then, of course, truly an unknown Indian and Sarkar referred to him on occasion as ‘the MA gentlemen’. Nirad Chaudhuri was then unemployed and with a family to maintain was financially in dire straits. His reflections about the young Raghubir bear repetition:

Sarkar’s supervision of Sinh’s work was, however, close and on one occasion a draft was sent to the press before Nirad Chaudhuri had time to go through it. It had many errors and we have Sarkar admonishing Sinh:

You have done your work with less than the necessary heedfulness in some cases; P1 of the final typed copy sent to the press reads ‘The anarchy was rampant’ whereas the definite article is ungrammatical here. … You can easily imagine how European examiners would be shocked on reading sentences like ‘the anarchy was rampant’.

As the thesis neared completion G.S. Sardesai and the English historian P.E. Roberts were appointed as its external examiners. While sending the thesis to Sardesai, Sarkar wrote: ‘This candidate’s work gives me much hope for his future as a worthy recruit to our campaign of sound historical research’, and:

Roberts too was impressed with the work and we have Sarkar informing Sinh in September 1936. I sent my report on the thesis along with Sardesai’s (both favourable) to the examiners in England by the sea mail. But in the meantime, he (P.E. Roberts) quickly read the thesis and sent to me by air mail an even stronger recommendation than ours.’

[P.E.] Roberts too was impressed with the work and we have Sarkar informing Sinh in September 1936. I sent my report on the thesis along with Sardesai’s (both favourable) to the examiners in England by the sea mail. But in the meantime, he (P.E. Roberts) quickly read the thesis and sent to me by air mail an even stronger recommendation than ours.’

And finally, in October 1936 when the thesis was approved and the book printed, Sarkar was effusive in his praise:

It gives me great pleasure to be able to address you as a Doctor of Literature. Your book will remain a standard authority on its special theme and certainly reflect credit on your university as setting the standard of its doctorate degree by the example of the work done…

Your success may have been facilitated by my guidance and loan of manuscripts but I feel you have legitimately contributed to the happy result by your intense application and sincere devotion to the task of clearing the history of your native province.

When an occasional critical review of the book appeared, or others criticized his student, Sarkar was characteristically protective:

Along with some perfunctory complementary remarks the review had said: ‘Maharajkumar Raghubir Singh’s narrative does not possess the charms of Sir John Malcolm’s memoirs. … The average reader may find the volume dull reading for the author is so deeply interested in the individual trees that he seldom takes notice of the wood.’ The review is unsigned but may well have been by Dr Surendranath Sen whose differences with Sarkar we will touch upon in Chapter V. Its authorship is suggested by the following sentences in the review very evidently targeted at Jadunath Sarkar: ‘Those who prefer the chronicle to a scientific history of the modern type will find better guides in such masters of narrative as Gibbon and Macaulay than in the Indian Chelas of William Irvine.’ There was, in fact, much in the thesis that would have appealed to Sarkar and the stamp of his approach to writing an authentic history is visible throughout in Malwa in Transition: chronological accuracy, evaluating the authenticity of a source from different angles and comparing various sources to establish a correct sequence of events, discarding in the process, wherever necessary, older interpretations. Yet, whatever the extent of the guidance from Sarkar, the work clearly bears the stamp of Raghubir Sinh’s own reflections on Malwa history.

Malwa in Transition, Raghubir Sinh’s most well-known work.

Malwa in Transition or A Century of Anarchy tells the story of an extinction of identity — in this case the identity of Malwa — in the eighteenth century. For Sinh the eighteenth century apart from being a century of anarchy was also a ‘century of revolutions’ as the ‘social and cultural map of India was completely changed’ and ‘many an old political entity was wiped off from the map of India’. This view was deeply embedded in Sinh’s mind and repeatedly recurs both in his historical works as also in his future activities as a politician and public intellectual. In Sinh’s treatment, the anarchy of the eighteenth century meant that his home region lost out in political, cultural and military terms and this was entirely on account of the Marathas. Local Malwa reaction, and especially from the leading Rajput families, to the Marathas was that they appeared ‘more as enemies than as friends’. We will engage in greater length with this perspective and how it was to interface with the views of Sardesai on Maratha expansion and Sarkar on Mughal decline.

Malwa in Transition or A Century of Anarchy tells the story of an extinction of identity — in this case the identity of Malwa — in the eighteenth century. For Sinh the eighteenth century apart from being a century of anarchy was also a ‘century of revolutions’ as the ‘social and cultural map of India was completely changed’ and ‘many an old political entity was wiped off from the map of India’. This view was deeply embedded in Sinh’s mind and repeatedly recurs both in his historical works as also in his future activities as a politician and public intellectual.

Building a Research Library

Even as Malwa in Transition was being researched and written, other facets of the Sarkar—Sinh relationship had also developed: Sarkar acting as a mentor in the collection of books and manuscripts for Sinh’s private library (which also supplemented Sarkar’s and Sardesai’s own historical research), and secondly, Sinh as an ally in hunting for and securing manuscript sources on Maratha and Rajput history from individuals and families reluctant to part with them. If in the initial years of the Sarkar—Sinh relationship we see much more of the guide and doctoral student at work, clearly the other aspects were as important virtually from the start: ‘You have my best wishes in your endeavour to build up an original and authentic history of Malwa in the 18th century … this will be a greater achievement than winning doctorate.’

And:

I am equally pleased to learn of your enthusiastic and judicious acquisition of rare books and still more precious Persian MSS … I can visualise a day when you will find that your library has grown so large and useful to scholars that you will move it from your residential palace to a building of easier access to the public.

In the years following the publishing of Malwa in Transition, Sinh established himself as a leading historian of Malwa and Rajasthan in his own right. In the Poona Residency Records series, of which Sarkar and Sardesai were the general editors, Sinh edited the Selections from Sir C.W. Malet’s Letter Book 1780–84 (1940), Daulat Rao Sindhia and North Indian Affairs 1800– 1803 (1943) and The Treaty of Bassein and the Anglo–Maratha War in Deccan 1802–04 (1951). Soon after Malwa in Transition but different in scope and intent was a full length study titled Indian States and the New Regime (1938) which addressed, as we shall see, the issues of a future federal India and the role the princely states could play in it. Through the 1930s he worked as a judge in the Sitamau high court and in other administrative capacities in the state administration. Service in the army during the war years added another dimension to Sinh’s public duties.

Indian States and the new regime.

With Independence, the claims of public life became stronger. Yet, the pull of history remained. The Sitamau library expanding from a small personal collection was now a major centre for research in its own right and in 1949 Sinh published a descriptive list or catalogue of its main holdings. The kernel of this was a presentation Sinh had made at the famous Kamshet conference in 1938 at Sarkar’s suggestion. Sarkar had then written to Sinh: ‘A small list (say, 8 or 12 pages) of your Persian MSS and Photostat acquisition would be well appreciated at Kamshet and though it must not be regarded as a final descriptive catalogue, it would add greatly to the value of your speech there.’

With Independence, the claims of public life became stronger. Yet, the pull of history remained. The Sitamau library expanding from a small personal collection was now a major centre for research in its own right and in 1949 Sinh published a descriptive list or catalogue of its main holdings. The kernel of this was a presentation Sinh had made at the famous Kamshet conference in 1938 at Sarkar’s suggestion.

The 1949 detailed catalogue had a glowing Foreword by Jadunath Sarkar. ‘The creation of this library,’ he wrote, ‘is due to the patriotic zeal, foresight, and persistence of an enlightened prince.’ Sarkar explained the reason behind Sinh’s venture:

The Raghubir Library now filled this gap. It was, Sarkar wrote:

Sarkar had been a partner in the growth of this library and remained so till his death. The following letter with all its detailed instructions is only one of many.

I have just secured through an ex–pupil of mine in Bihar, an imperfect MS of the letters of Ahmad Shah Abdali to Sawai Madho Singh of Jaipur. Please set your best munshi immediately to copy the leaves marked in blue pencil 1 to 34 on one side of the paper.At the end of the folio 34 back, leave the rest of the page of the copy blank as there is a gap here.

Then on a new sheet start copying the two folios marked 36 and 37 — in all 73 pages. (To be copied only 71 pages not 73, because folio 35 is a blank.)

Please send the original back to me with the copy made at Sitamau and after taking notes I shall return the copy to your library.

Kindly keep it a secret from the Jaipur Darbar (and indeed from all other people) that I have secured these records of their ancestor’s dealings with Abdali. Very likely they have lost the originals.

The letters in question related to 1759—61 and one may therefore well wonder whether the emphasis on secrecy came from an exaggerated sense of self–importance or an excessive caution. But equally, perhaps, given the sensitivities at play — which both Sinh and Sarkar were conscious of — the caution was not entirely misplaced. The letters show the ruler of Jaipur, Madho Singh, more concerned about evicting the Marathas and reducing their influence from his territory and willing to do what he could in the matter in concert with the Afghans led by Ahmad Shah Abdali. That the historical conjuncture in which this correspondence took place was before and after the battle of Panipat when the Marathas were defeated added to their significance. The caution had, therefore, some basis.

Sarkar explained the reason behind Sinh’s venture: “The oldest, completest, and best–transcribed copies of most Persian histories and State–papers of the Muslim period are preserved in the public libraries of Europe, and our patriotism naturally feels hurt at so many of our best historical material having gone out of our country.”… The Raghubir Library now filled this gap.

But there is also — amidst the talk of sources, manuscripts and historical personages — regular and detailed practical advice to Sinh on his growing library:

In 1937–38, Sinh introduced a technological leap in the research culture of the time with its reliance on copying of manuscript sources by hand, engaging paid copyists and clerks. Sinh recollected later:

From 1937–38 microfilms were in use which were cheaper. … I began corresponding with England and read in a newspaper that Kodak had introduced a special amplifier called Recordek to read microfilms. I wrote to the Kodak people in Bombay that I wanted to buy a Recordek. They replied that they did not know what it was and would get in touch with suppliers in England. The Recordek reached Sitamau in Nov–Dec 1938.

Evidently Sinh had consulted Sarkar earlier for we have this excited letter of October 1937: ‘What you say about micro– filming has thrilled me. We can now get all that we need for our historical workshop, at a cost within our means.’

The microfilm reader in Sitamau is believed to be the first in use in India. A decade later this quantum leap still fascinated Sarkar and in an introduction to the handbook on the Sitamau Library we have the following description:

The discovery of the possibility of photographing records and then being able to store them on microfilm or take copies for use in case microfilms were not available opened up many possibilities. The research by Sarkar and Sardesai in the Peshwa Daftar and the Poona Residency Records and their familiarity with this archive meant that with a microfilm reader available in Sitamau, records in Poona could be filmed and then transferred to Sitamau. We see a somewhat unusual enterprise now emerging. The good offices of Sarkar and Sardesai meant that Sinh was able to get the government authorities concerned to approve the filming of selected records in the Poona Archives.

The discovery of the possibility of photographing records and then being able to store them on microfilm or take copies for use in case microfilms were not available opened up many possibilities. The research by Sarkar and Sardesai in the Peshwa Daftar and the Poona Residency Records and their familiarity with this archive meant that with a microfilm reader available in Sitamau, records in Poona could be filmed and then transferred to Sitamau. We see a somewhat unusual enterprise now emerging.

This was easier said than done since the process involved the documents being physically sent to another government office — the Government Photo Registry Office in Poona — to be filmed there and thereafter the microfilms being sent by railway parcel to Sitamau. That at least one of Sardesai’s former assistants and a historian in his own right, V.G. Dighe, was employed or working at the Poona Archives, made the logistical work of separating the documents to be filmed and then sent to the Photo Registry Office easier. Even with Sarkar’s full help in terms of getting the necessary permissions, the fact that this task could be carried out with two government establishments coordinating and cooperating with each other to see the task to fulfilment is testimony to Sinh’s own persistence and powers of persuasion as also his commitment to the task by investing the not inconsiderable sums required.

A thick file in Sitamau in the Raghubir Library is a silent witness to these efforts as it shows a long and protracted correspondence for over a decade with the Poona Archives and the Photo Registry Office. The documents chosen for filming were the Persian records in the archives and comprised a mass of papers including newsletters (akhbarat) sent to the British resident in Poona during the period 1796–1817. In all, the work involved some 15,000 exposures and its scale was further compounded with wartime shortages of film, paper, equipment, etc. The task in brief is a classic illustration of how a new technology could be successfully applied in an environment, prima facie adverse.

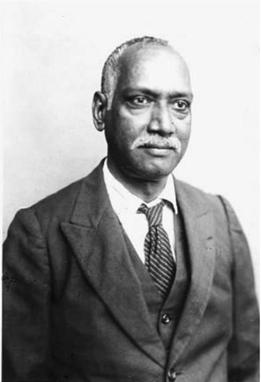

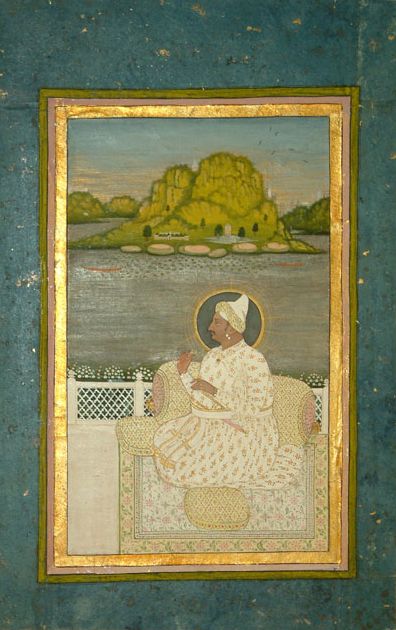

Jadunath Sarkar

From the 1940s onwards Sardesai’s often poor health and concerns about the fate of his own not inconsiderable library of books and records after his death led Sarkar to explore the possibility of the Sitamau Library being the final custodian of the Sardesai collection. We have this letter to Sinh in March 1948:

And a little later:

But there were other bidders and in particular the Government of Bombay. A little over a year later Sarkar cautioned in a note marked ‘Confidential’:

The desire of the owner of the Maratha historical library at Kamshet is to sell it to the highest bidder and hand over the price money to the School at Kamshet as a part of its endowment fund. Dr P.M. Joshi will bid anything to get it. Govt. money ‘has no father or mother’.It would not be advisable for the owner of the Raghubir Library to spend recklessly at this auction — as there are more pressing demands — rare old Eng. Books yet to be acquired

Raghubir Sinh had, in fact, quickly acquired a dual role in Sarkar’s and by extension Sardesai’s life. He was the younger colleague, and student, to be guided, encouraged and treasured. Yet Sinh as scion of a princely state, howsoever small, also fulfilled another role. He, in building up his own research collection and library, had resources, access and connections that neither Sarkar nor Sardesai could match to acquire or have copied manuscripts that would be valuable to their own research.

Raghubir Sinh had, in fact, quickly acquired a dual role in Sarkar’s and by extension Sardesai’s life. He was the younger colleague, and student, to be guided, encouraged and treasured. Yet Sinh as scion of a princely state, howsoever small, also fulfilled another role. He, in building up his own research collection and library, had resources, access and connections that neither Sarkar nor Sardesai could match to acquire or have copied manuscripts that would be valuable to their own research.

Secondly, with regard to Sinh’s dual role, by reason of his birth alone, Sinh had an intimacy with Rajput history and with the Rajput—Maratha interface which made him invaluable for Sarkar’s and Sardesai’s own research. Being a part of the fraternity of the ruling princes of central India meant also a close relationship and in some cases even friendship with the ruling houses of princely states such as Scindia, Jodhpur, Kota, Jaipur, Indore, etc., — the history of each of which figured substantively in Sarkar’s major research work of the 1930s and 1940s, namely, the Fall of the Mughal Empire. A letter of February 1938 from Sarkar to Sardesai illustrates this role and brings out an almost paternal pride with which it was regarded:

Dr Raghubir Sinh when on a visit to Gwalior at the end of January last at the invitation of Maharajah Sindhia, had had a talk with Sir Manubhai, who promised to take steps in the matter of the Meenavali Daftar. The Maharajkumar adds, ‘I made a casual reference to the matter while talking to Maharaj Sindhia also … I did not talk (at length) otherwise it would have touched Sir Manubhai whose cooperation is most essential just now.’ You mark the young Diplomat!!!

Raghubir Sinh had, in fact, direct access to a vast corpus of Rajput history which could illustrate and animate the Rajput— Maratha interface in the late eighteenth century:

Sarkar wrote in September 1937:

Sinh was in fact a full–fledged member of the circle extracting and unearthing manuscripts and Sarkar had often the role of the equally enthusiastic researcher but also a more careful older voice of caution. A letter to Sinh in January 1941 says:

But in other cases, even Sarkar, normally a hard bargainer, realized the need for expedition as in this letter of August 1938:

…with regard to Sinh’s dual role, by reason of his birth alone, Sinh had an intimacy with Rajput history and with the Rajput—Maratha interface which made him invaluable for Sarkar’s and Sardesai’s own research. Being a part of the fraternity of the ruling princes of central India meant also a close relationship and in some cases even friendship with the ruling houses of princely states such as Scindia, Jodhpur, Kota, Jaipur, Indore, etc., — the history of each of which figured substantively in Sarkar’s major research work of the 1930s and 1940s, namely, the Fall of the Mughal Empire.

A Supportive Fraternity of History

Following the award of the DLitt. for ‘Malwa in Transition’ we find Sarkar trying to refocus Raghubir Sinh’s next research interest on Mirza Rajah Jai Singh:

Sarkar’s recommendation followed: ‘You should master the Persian language (historical prose only) sufficiently to make yourself independent … and to be able to pick information out of MSS directly without having to wait for their being transcribed and translated.’ In January 1937, Sarkar pressed both points again — learning Persian, and ‘I anticipate that the career of Mirza Rajah Jai Singh will fascinate you so much that you will concentrate on him and, most probably continue the study of the dynasty of Amber up to 1698 and forget for a time your beloved Malwa.’

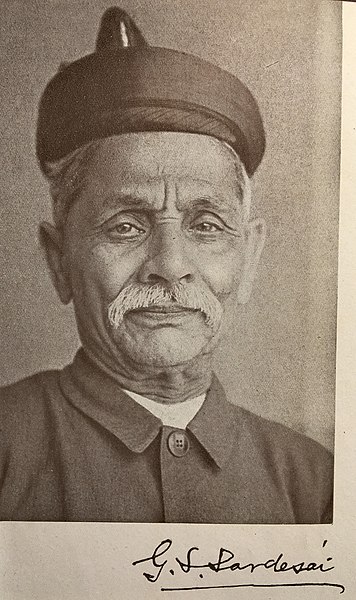

GS Sardesai.

While this particular idea does not appear to have generated sufficient enthusiasm in Sinh, Sarkar had in fact put his own reputation in getting him acknowledged as a major historian.

Sarkar suggested that Sinh buy the letter book of Charles Malet for the period 1780–84 from a rare book and transcript dealer in London who had put it up for sale. These letters would be a valuable supplement to the documents relating to Malet included in the Poona Residency Records series. Sarkar’s practical advice to Sinh was that since these letters were not available in the Poona records in editing the Malet letter book ‘… you will not be called upon to visit Poona’.

In case Sinh was unsuccessful in securing the letter book, Sarkar outlined his backup plan: ‘I shall arrange with Sardesai to give you the editing work of some other volumes of the Poona Residency Records.’ In the event Sinh’s attempt at securing the manuscript was successful. We have Sarkar writing to Sinh of how ‘thrilled’ he was at the news of ‘this great victory’ which he attributed to Sinh having sent a cable to secure the document (which also Sarkar had not just advised but also sent a draft of the telegram).

Sarkar’s recommendation followed: ‘You should master the Persian language (historical prose only) sufficiently to make yourself independent … and to be able to pick information out of MSS directly without having to wait for their being transcribed and translated.’ In January 1937, Sarkar pressed both points again — learning Persian, and ‘I anticipate that the career of Mirza Rajah Jai Singh will fascinate you so much that you will concentrate on him and, most probably continue the study of the dynasty of Amber up to 1698 and forget for a time your beloved Malwa.’

In the preparation of the edited volume of Malet’s letters Sarkar’s instructions were detailed and precise: ‘You will have to consult Sardesai on the details of Maratha affairs during the four or five years covered in it.’ And:

And later:

Sarkar’s efforts to establish Sinh as a historian of repute in his own right in fact were many. He arranged for Raghubir Sinh to speak at the 1937 session of the Indian Historical Records Commission and present in summary form the contents of Malet’s letter book. Similarly, in September 1938 before the Kamshet meeting we have him advising Sinh that a report on his manuscript collection would ‘add greatly to the value of your speech’. Selections from Sir C.W. Malet’s Letter Book 1780–1784 appeared in 1940 and it is listed as a supplementary volume in the Poona Residency Records series. By mid–1939 Sarkar and Sardesai decided that the responsibility of editing a second volume in the Poona Residency Correspondence could also be given to Sinh. By this time the Malet letter book volume was nearing finalization — and Sinh was assigned the period 1800–03. The volume finally formed Vol. IX of the Poona Residency Correspondence with the title ‘Daulat Rao Sindhia and North Indian Affairs 1800–1803’ and was published in 1943. A third volume forming Volume X in the Poona Residency Correspondence collection was also edited by Sinh and published in 1951 as The Treaty of Bassein and the Anglo Maratha War in Deccan 1802–1804.

Raghubir Sinh, however, continued to be associated with public issues to a far greater extent than either G.S. Sardesai or J.N. Sarkar or the other historians and scholars in their circle. As heir to the throne of a princely state, howsoever small, it was inevitable that Raghubir Sinh would have a public life outside history, notwithstanding his passion for historical research and studies. His life as a historian, in fact, followed a complementary and parallel track of his role as the heir. Having a law degree, he had been appointed a judge of the high court of Sitamau — a post he held from 1932 till 1940. He was, as heir, also assigned the responsibility over other departments of Sitamau’s administration — revenue, education, health and others, apart from being associated with the Chamber of Princes.

Sarkar’s efforts to establish Sinh as a historian of repute in his own right in fact were many. He arranged for Raghubir Sinh to speak at the 1937 session of the Indian Historical Records Commission and present in summary form the contents of Malet’s letter book. Similarly, in September 1938 before the Kamshet meeting we have him advising Sinh that a report on his manuscript collection would ‘add greatly to the value of your speech’.

His participation in the sessions of the Chamber of Princes led to an intervention on the issue of princely states which should be seen in the context of the wider political debate then under way in India. The intervention was in the form of a book, Indian States and the New Regime, published in 1938 and is an early attempt to address issues arising from the 1935 Government of India Act for a future independent and federal India and the role of the princely states in such a federation. The book had a forward by Sir C.P. Ramaswamy Iyer, then dewan of Travancore a and who was in the eyes of many a virtual institution of law and politics of early twentieth century India.

Ramaswamy Iyer wrote: ‘It is a sign of the times that the heir apparent of the Sitamau State in Central India, should not only win academical distinctions and a doctorate for his writings on historical topics but should publish a comprehensive and well–conceived monograph dealing with the history of the relations of the Indian states with the Paramount Power.’

The reason for embarking on this treatise — the book runs into some 500 pages — were stated by Raghubir Sinh as: ‘The tide of democracy is rising with an added force: it would not be very long before this rushing tide will overflow the bounds that separate the Indian States from British India and will flood the Indian States as well.’

Raghubir Library and Research Institute. [Credits: natnagarsitamau.com]

The answer lay for Raghubir Sinh in a federal arrangement requiring cooperation between the princely states. While this process was assisted by the creation of a Chamber of Princes, it remained weak and faltering on account of differences between the larger and the smaller princely states. A reviewer in International Affairs, the journal of the Royal Institute of International Affairs, pointed out ‘… the author found fault with “small” states though he himself is connected with a “small” state’.

His participation in the sessions of the Chamber of Princes led to an intervention on the issue of princely states which should be seen in the context of the wider political debate then under way in India. The intervention was in the form of a book, Indian States and the New Regime, published in 1938 and is an early attempt to address issues arising from the 1935 Government of India Act for a future independent and federal India and the role of the princely states in such a federation.

For scholars as driven as Sardesai and Sarkar, Raghubir Sinh’s public commitments, howsoever worthy, were nevertheless also costly distractions from historical research. While Sarkar is more forgiving of his protégé and favourite student, Sardesai often was not. We have a letter he wrote to Sarkar in January 1940 with regard to the Malet Letter Book that Raghubir Sinh was editing:

Sarkar’s defence of his protégé is also characteristic:

During the war years Raghubir Sinh joined the British Indian Army — not uncommon for princes. He rose to the rank of major before resigning his commission in 1945. He did not see active service and was posted at Peshawar and Madras while in uniform. Decades later Raghubir Sinh reminisced that he was prompted to join the army to learn something new: understanding military tactics would help in understanding history. Sarkar’s letter to Sinh on the latter’s joining the army also merits to be quoted:

The correspondence with Sarkar continued through this period and with it a steady stream of proofs of the Poona Residency Correspondence, copies of manuscripts and suggestions of books and papers to acquire for Raghubir Sinh’s now growing library.

For scholars as driven as Sardesai and Sarkar, Raghubir Sinh’s public commitments, howsoever worthy, were nevertheless also costly distractions from historical research. While Sarkar is more forgiving of his protégé and favourite student, Sardesai often was not.

For instance, Sarkar wrote in September 1943:

And in April 1944:

Over time, as the relationship matured, we see, as in the case of Sardesai and Sarkar, concern and affection becoming more visible in the Sinh—Sarkar correspondence. The younger man’s obvious esteem and regard are made evident in ways that move the now ageing and grief–stricken Sarkar greatly. Writing about the Hindi edition of A Short History of Aurangzeb which Sinh was helping prepare, Sarkar wrote in June 1950:

In fact, as the two masters aged and grew more frail their students had formed a protective cloak around them. We have the following letter from Qanungo to Raghubir Sinh in January 1957:

And again a few weeks later in in March 1957:

Through the early and mid–1950s, although Sarkar had been regularly in correspondence with Sinh the letters of the last few years show a gradual and unmistakable role reversal as the former student now becomes a principal support. The daily grind of frailty and old age, worries about his family and further tragedies are a prominent part of the letters that Sarkar writes.

Through the early and mid–1950s, although Sarkar had been regularly in correspondence with Sinh the letters of the last few years show a gradual and unmistakable role reversal as the former student now becomes a principal support. The daily grind of frailty and old age, worries about his family and further tragedies are a prominent part of the letters that Sarkar writes.

In September 1955: ‘After five years of decline my sole surviving son … left us. His agonies have ended but his mother’s know no consolation.’

And in April 1957:

And in addition to his wife’s and his own ill health there is the ever–present concern regarding Sardesai:

But despite all these preoccupations, the engagement over history and straightening the most obscure historical detail remains a priority. Thus, we have Sarkar writing to Raghubir Sinh in November 1955 again with regard to the battle of Dharmat:

In question was the date of the battle of Dharmat, important as we shall see both for Sardesai and Sinh, in which Aurangzeb had secured his first victory against Shah Jahan and Dara Shukoh’s armies led by Jaswant Singh, the Raja of Jodhpur. One of Jaswant Singh’s principal commanders was Raghubir Sinh’s ancestor Ratan Singh, the ruler of Ratlam who was killed in this battle.

The Raghubir Library is a treasure trove of rare manuscripts and documents. [Credits: natnagarsitamau.com]

And again: ‘… for the past week or so, I was enjoying the company of these elders who are no more while reading the proofs … Oh, what a grand company it was and what an enjoyable experience was mine.’

Contacts between the circle of historians around G.S. Sardesai and Jadunath Sarkar continued after their mentors’ death. S.R. Tikekar, Sardesai’s devoted associate, and Raghubir Sinh in particular wrote regularly to each other for over two decades — about old times and the masters, gossiping occasionally about the new history establishment that now called the shots but also occasionally discussing possible new projects.

Tikekar’s letters bring out all the difficulties of working with the government in a project such as this even though he himself worked in the Maharashtra State Archives. However, when the work appeared in 1975 it enthused both Tikekar and Sinh to think of publishing Sarkar’s letters to his other students. The Tikekar—Sinh correspondence also occasionally dissected specific occasions of the masters’ lives. On one occasion, while the editing of Making of a Princely Historian was in progress, Tikekar inquired whether Sarkar had written to Sinh after Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination and, if not, the reason for this. Sardesai had then written to Sarkar on 2 February 1948: ‘The wicked act of the Mahatma’s murder will remain a standing disgrace to the Brahmans of Maharashtra.’ With regard to the absence of any reference to the assassination in Sarkar’s letters to himself, Sinh wrote:

Whatever be the cause, I feel that he was in no mood to comment or soliloquize on the tragic event. I feel that the partition of the country, separation of his own hometown and district from the Indian dominion, his dear ones and his own property thus going into the foreign land must have only aggrieved his feelings which were sufficiently scarred by the sad death of his elder son, A.N. Sarkar, during the pre–partition riots in 1947. Hence this ominous silence.

He also related the concerns Sarkar may have had about his (Sinh’s) future:

Raghubir Sinh and Tikekar also relieved in their own letters many of the regional parochialisms their mentors had experienced. After The Making of a Princely Historian was published, we have Tikekar writing:

Raghubir Sinh’s reply also underwrote the long afterlife of older rivalries: ‘These bloody Poona Pandits must have been quite shocked and now (are) busy cursing you with all their heart.’ And a few weeks later Tikekar wrote about other fronts: ‘What’s the princely reaction that you have received so far? I don’t know how the Bengali gang is going to react to the publication.’

The Bengali gang, Sinh replied, would welcome the book although many ‘… who think highly of themselves without much real worth will necessarily be very jealous’ and there would be others who would not be happy ‘… as it means a propaganda for a former prince’. The letter concluded somewhat characteristically: ‘This is all your mischief, for which I shall remain grateful.’

Tikekar’s letters bring out all the difficulties of working with the government in a project such as this even though he himself worked in the Maharashtra State Archives. However, when the work appeared in 1975 it enthused both Tikekar and Sinh to think of publishing Sarkar’s letters to his other students. The Tikekar—Sinh correspondence also occasionally dissected specific occasions of the masters’ lives

Raghubir Sinh was to remain a committed letter writer all his life. Apart from the correspondence with Sarkar, at least two other collections of his letters have been published and these too underline lifelong interest in Rajput and Malwa history, literature and, most of all, authentic manuscripts.

A Historian in Public Affairs

At the same time Raghubir Sinh himself was now moving on to a larger national stage. In May 1952 he was nominated a member of the Upper House — the Rajya Sabha — of the Indian parliament and remained so up to 1964. In 1951 he published two works in Hindi, Ratlam Ka Pratham Rajya (The First Kingdom of Ratlam) and Poorva Adhunik Rajasthan (Pre–Modern Rajasthan) and we will engage with both these works later. This was also the year in which the Hindi translation of Sarkar’s abridged version of Aurangzeb was published on which Sinh had worked so hard and which had so touched Sarkar. Later in his life he was to write popular but accurate and well–researched works in Hindi such as Maharana Pratap (1973) and Durgadas Rathor (1975). Revised and updated works on Maharana Pratap appeared in 1980 and 1983.89 As a member of parliament, Sinh is described as having followed in particular issues such as culture, literature and Hindi as the national language.

Writing history in Hindi — rigorously researched and lucidly written — had become and was to remain a priority for Sinh. The commitment to Hindi led to an unusual situation at the 1952 session in Gwalior of the Indian History Congress where Sinh had been invited to deliver the presidential address to the Local History Section. Sinh wanted to ‘… deliver this address of mine in Hindi, the national language of our beloved motherland’. Although this ‘… would have been a real departure from the past practice’, Sinh said he was confident ‘that all those interested in the history of the land of Bhartrihari and Bhoj, even though coming from the distant non–Hindi speaking regions, know Sanskrit sufficiently enough to understand such an address in Hindi’. Sinh, as it happened, was persuaded to do otherwise and address the session in English although he issued a Hindi version of his address as he felt ‘… he must speak to the people of my home province only in Hindi’.

In Sinh’s engagement with public affairs at the national stage we see a clearer, sharper focus on what had been earlier his principal research interest: the preservation of regional identity, its integration into a larger national edifice and the writing of objective history to smoothen the interface between the regional and the national. In his 1952 address to the Local History Section of the Indian History Congress he underlined that ‘… in a vast country like India, a really complete and fully comprehensive national history cannot be prepared without the help of the authoritative histories of the different provinces, as these regional histories provide the solid foundations of the national history’.

In Sinh’s engagement with public affairs at the national stage we see a clearer, sharper focus on what had been earlier his principal research interest: the preservation of regional identity, its integration into a larger national edifice and the writing of objective history to smoothen the interface between the regional and the national.

If in the early years after Independence, the regeneration and reconstruction of India, was ‘the primary concern’, history also pointed to the danger of centrifugal tendencies:

For independent India the answer, in Sinh’s view, could only be constituting the regional units so that ‘… they provide for a solid foundation… as the integrant parts of a composite body politic’. This was essential because ‘the Constitution of India’, Sinh asserted, ‘cannot by itself perpetuate the Union.’

Sitamau State Coat of Arms.

This argument was clearly derived from his research on Malwa’s history. Malwa’s identity had disintegrated in parallel with the fall of the Mughal Empire and by the time of its transfer to the Marathas it was parcelled into a number of principalities of Rajput rajas, Muslim nawabs and Maratha warlords. The Peshwa ‘generally gave their generals more than one non–contiguous areas interspersed with the lands ruled by others … [and this] cut deep at the very roots of the cultural homogeneity of Malwa’. The British may have established peace and security but ‘… they failed to restore to Malwa its political unity and thus the centuries–old historical continuity of the region was completely cut off and lost in the maze of the political boundaries of the different states into which it was divided’. For a historian, therefore, the task was to supersede the dynastic and family–oriented multiple histories emanating from Malwa ‘through which family rivalries, dynastic jealousies, racial animosities and interstate antagonisms … gained added importance’.

In these circumstances, the priorities, for Sinh at least, was to expedite the rise and growth of a ‘new regional outlook’ that would supersede the dynastic. For which it was essential that ‘… regional history be compulsorily taught even at lowest classes of the schools and encouraged in later years of college studies.’ Regional history would be the building block for national history just as regional identities would reinforce the nation. It is easy to see the themes that predominated in Malwa in Transition and the non–dynastic treatment of political history that characterized his 1951 book Poorva Adhunik Rajasthan informing these views.

But most of all Independence meant an opportunity to undo the historical wrong done to Malwa in the eighteenth century with the collapse of the Mughals and Maratha expansion. We get occasional glimpses of how much the subject of Malwa engaged Sinh’s attention in the post–1947 period from occasional comments in letters of Sarkar. In March 1948 he wrote to Sinh: ‘The Union of Malwa when accomplished will heal a long–standing grievous wound in the body of mother India.’

In these circumstances, the priorities, for Sinh at least, was to expedite the rise and growth of a ‘new regional outlook’ that would supersede the dynastic. For which it was essential that ‘… regional history be compulsorily taught even at lowest classes of the schools and encouraged in later years of college studies.’ Regional history would be the building block for national history just as regional identities would reinforce the nation.

Sinh’s policy takeaway from his research and understanding of regional identity and history, however, comes through most strongly in a long memorandum he submitted to the Indian States Reorganisation Commission in 1954 titled’. ‘The Reorganisation of the States of Madhya Bharat.’

Madhya Bharat had existed as an improvised administrative unit since Independence comprising the large princely states of Gwalior and Indore along with some dozen and a half smaller princely states. Sinh’s memorandum is a compression of the administrative history of this region under the Mughals, the Maratha and the British as equally an analysis of the linguistic and cultural diversity within the region. In the writing of the memorandum and in framing its recommendations there is very evidently a reliance on his understanding of the forces and factors he had identified as a historian of Malwa.

For instance, writing of contemporary administrative problems and difficulties, Sinh said: ‘The first and foremost of all such problems is the very well–known rivalry and tussle between the cities of Indore and Gwalior. Even though originally a direct result of the dynastic jealousies and state rivalries between those of Sindhia and Holkar, it has continued unabated…’ The memorandum, in fact, is deeply permeated by Sinh’s study of the late eighteenth century in Malwa in Transition and his recommendation to the States Reorganisation Commission emerge out of his view of the rupture in the history of Malwa in the eighteenth century.

The substance of this submission was a demand for a separate state of Malwa to replace the administrative expediency adopted after 1947 of accumulating disparate areas from different princely states into Madhya Bharat, which was based on the ‘… old pattern originally laid down by the British rulers of the country during the latter half of the XIXth century’. Madhya Bharat as constituted after 1947 was based on boundaries of princely states ‘… finalised and duly demarcated by Sir John Malcolm’. This, therefore, meant that predispositions of the British — ‘very much carried away by their own supposed notions of dynastic affinities or historical continuity’ — were not corrected and needed to be rationalized. Sinh gave numerous examples of the irrationality and arbitrary approach by which small princely states were allocated to Madhya Bharat or to the Rajputana Agency later to be reconstituted as Rajasthan.

The memorandum could only have been written by a historian of Malwa and, in fact, it is the political argument emerging from Malwa in Transition. His argument in brief was that Malwa’s ancient and well–defined administrative and cultural unity faced erosion with the decline of the Mughals and the rise of the Marathas. The failure of the latter to create a viable central structure in Poona meant that Malwa became the theatre of a bitter Scindia—Holkar rivalry and from the end of the eighteenth century ‘… commenced a period of serious unrest and unmitigated rivalry’ and ‘by 1817 the disorganisation in Malwa had reached a climax’. British intervention in central India thereafter led to a ‘… most amazing and quite a difficult jigsaw puzzle’ — in brief a further dilution of Malwa’s identity.

His argument in brief was that Malwa’s ancient and well–defined administrative and cultural unity faced erosion with the decline of the Mughals and the rise of the Marathas. The failure of the latter to create a viable central structure in Poona meant that Malwa became the theatre of a bitter Scindia—Holkar rivalry and from the end of the eighteenth century ‘… commenced a period of serious unrest and unmitigated rivalry’ and ‘by 1817 the disorganisation in Malwa had reached a climax’. British intervention in central India thereafter led to a ‘… most amazing and quite a difficult jigsaw puzzle’ — in brief a further dilution of Malwa’s identity.

The thrust of Raghubir Sinh’s submission was to radically redraw boundaries of Madhya Bharat and re–establish Malwa’s old identity. The evidence he presented was administrative, linguistic and political — but this was emphatically most of all a historian’s argument. ‘Since very ancient times the Malwa region has figured very prominently in Indian history. Its well–known chief town, Ujjain, had become even in Buddhistic times an important seat of Indo–Aryan culture.

Raghubir Sinh’s short point was that it was only under the Marathas that Malwa’s political and administrative unity was ‘completely shattered’. This ‘could not be duly restored even by the British’. However, in the more recent past with education, growth in knowledge about their past, growth of cultural consciousness and, above all, rapid political awakening, Malwa’s own traditions and regional unity had become live factors and ‘… must necessarily be duly taken care of in any scheme for the reorganization of the existing states in the region’.

The recommendation he made, in brief, was for Madhya Bharat to be reconstituted as Malwa by a process of significant subtractions and additions to its territory. The significant subtraction was detaching Gwalior state from the new state. The most significant addition was adding most of the old princely state of Bhopal to it as also the Hoshangabad and Nimar districts of the Central Provinces of British India. This restructuring and reorganization of Madhya Bharat will mean that ‘… the new state of Malwa will most definitely be a very great tower of strength to the Indian Union and a really powerful source of inspiration to the Indian nation’.

Raghubir Sinh’s enthusiasm for a new state of Malwa was, however, not widely shared and his oral testimony before the States Reorganisation Commission saw some close cross– questioning of his memorandum by an unconvinced K.M. Panikkar, an accomplished historian and administrator and a member of the Commission. When, asked Panikkar, was Malwa last in existence? On receiving ‘1742’ in answer from Raghubir Sinh, Sardar Panikkar went on to say: ‘There is no mention of anything belonging to Malwa. From the historical point of view for the last 212 years there is no such thing. So, you want to make a case for Malwa today.’

Panikkar remained unconvinced and pointed to the larger concerns which obviously the Commission heeded — the financial viability of the state, the implications for future hydroelectric and irrigation projects on the Chambal and the Narmada, etc. That Sinh sounded, and was unconvincing, is not surprising: his argument was almost entirely a historical one. To Panikkar’s comment that Malwa had not existed now for over two centuries, Raghubir Sinh replied: ‘…certain traditions and certain things have gone on.’ To buttress his arrangement for Hoshangabad district being detached and included in Malwa he argued: ‘In Hoshangabad district there is a town named Seoni. To distinguish it from another town of same name, the former is called Seoni Malwa.’

Raghubir Sinh’s enthusiasm for a new state of Malwa was, however, not widely shared and his oral testimony before the States Reorganisation Commission saw some close cross– questioning of his memorandum by an unconvinced K.M. Panikkar… When, asked Panikkar, was Malwa last in existence? On receiving ‘1742’ in answer from Raghubir Sinh, Sardar Panikkar went on to say: ‘There is no mention of anything belonging to Malwa. From the historical point of view for the last 212 years there is no such thing. So, you want to make a case for Malwa today.’

As the hearing concluded, the sceptical Panikkar, however, had a final piece of advice for Raghubir Sinh:

What emerged from the States Reorganisation Commission was a giant Madhya Pradesh, literally the old Central Provinces — in which to the original British Central Provinces all the princely states of the region were added — Bhopal, Gwalior, Indore and a host of smaller ones including Sitamau. If no separate state of Malwa was then or has since been created, it remained nevertheless central to Raghubir Sinh’s thought, and to this day the postal address of the institute he founded remains the one he had always used: Shree Natnagar Shodh Samsthan, Sitamau, Malwa.

After two terms as a member of parliament, from 1964 onwards he devoted himself to his principal priorities — history, research and the building up of his research library in Sitamau. The extent of Jadunath Sarkar’s and Sardesai’s influence is illustrated by his commitment to the finalizing of their incomplete projects, which he made his own and saw to some kind of fruition when old age and frailty had incapacitated and then removed his mentors. We shall touch on each of these later. Each was no less than a quest — pursued over decades — and animating, in the process, a shared friendship and love of history.

Family tragedies of the kind that had struck Sarkar and Sardesai did not spare him either. In 1967 a young son died tragically in a swimming accident within days of his marriage followed by the death of Sinh’s father. He chose then not to be the titular raja of Sitamau state and stepped aside in favour of his son. Till his death in February 1991, Sinh was active in research, editing and compiling of documents on Rajput, Maratha, Mughal and Malwa history. The library in Sitamau remained to the end his passion. An annual research conference held in its premises in his memory remains today a testimony of Sitamau’s prince who chose instead to be a historian.

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of TCA Raghavan. You can buy History Men: Jadunath Sarkar, GS Sardesai, Raghubir Sinh and their Quest for India’s Past here.

ARCHIVE

Shivaji’s Achievement, Character and Place in History

-

Shivaji’s policy how far traditional

Shivaji’s State policy, like his administrative system, was not very new. From time immemorial it had been the aim of the typical Hindu king to set out early every autumn to “extend his kingdom’ at the expense of his neighbours. Indeed, the Sanskrit law-books lay down such a course as the necessary accomplishment of a true Kshatriya chief. (Manu. vii. 99-103, 182.) In more recent times it had also been the practice of the Muhammadan sovereigns in North India and the Deccan alike. But these conquerors justified their territorial aggrandisement by religious motives. According to the Quranic law, there cannot be peace between a Muhammadan king and his neighbouring “infidel” States. The latter are dar-ul-harb or legitimate seats of war, and it is the Muslim king’s duty to slay and plunder in them till they accept the true faith and become dar-ul-islam, after which they will become entitled to his protection.

The coincidence between Shivaji’s foreign policy and that of a Quranic sovereign is so complete that both the history of Shivaji by his courtier Krishnaji Anant and the Persian official history of Bijapur use exactly the same word, mulk-giri, to describe such raids into neighbouring countries as a regular political ideal. The only difference was that in theory at least, an orthodox Muslim king was bound to spare the other Muslim States in his path and not to spoil or shed the blood of true believers, while Shivaji (as well as the Peshwas after him) carried on his mulk-giri into all neighbouring States, Hindu no less than Islamic, and squeezed rich Hindus as mercilessly as he did Muhammadans. Then, again, the orthodox Islamic king, in theory at least, aimed at the annexation and conversion of the other States, so that after the short sharp agony of conquest was over those places enjoyed peace like the regular parts of his dominion. But the object of Shivaji’s military enterprises, unless his Court-historian Sabhasad has misrepresented it, was not annexation but mere plunder, or to quote his very words, “The Maratha forces should feed themselves at the expense of foreign countries for eight months every year, and levy blackmail.” (Sabh., 26.)

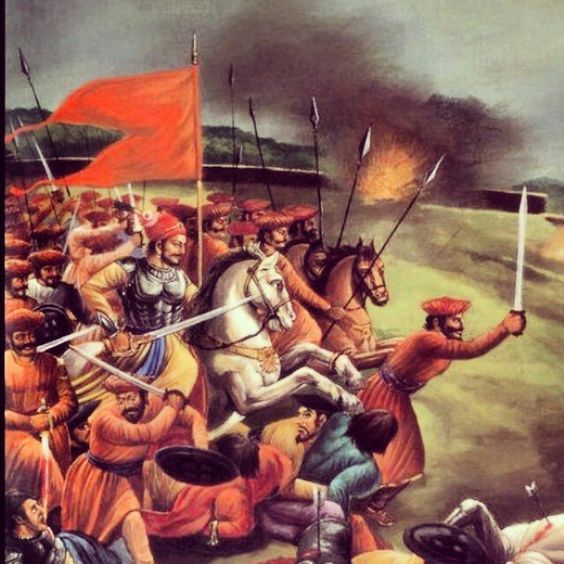

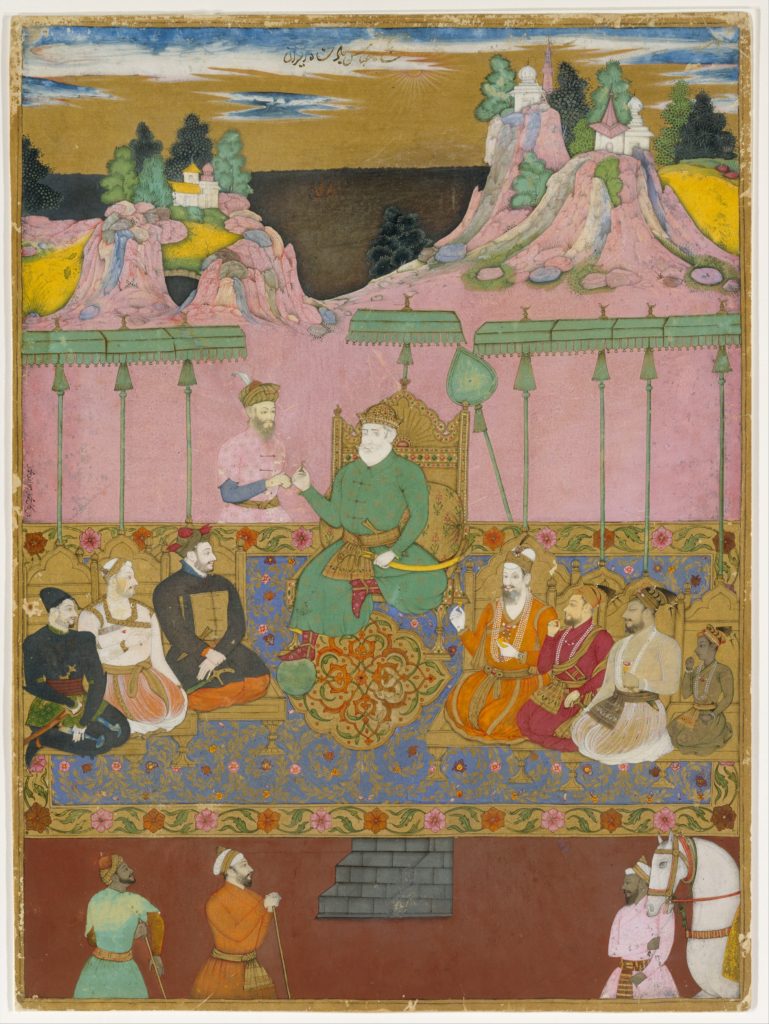

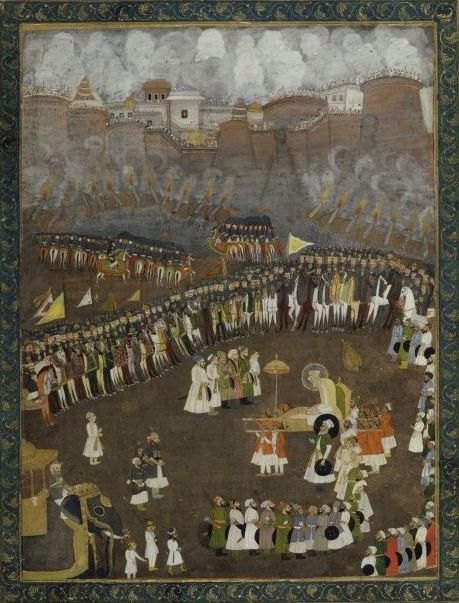

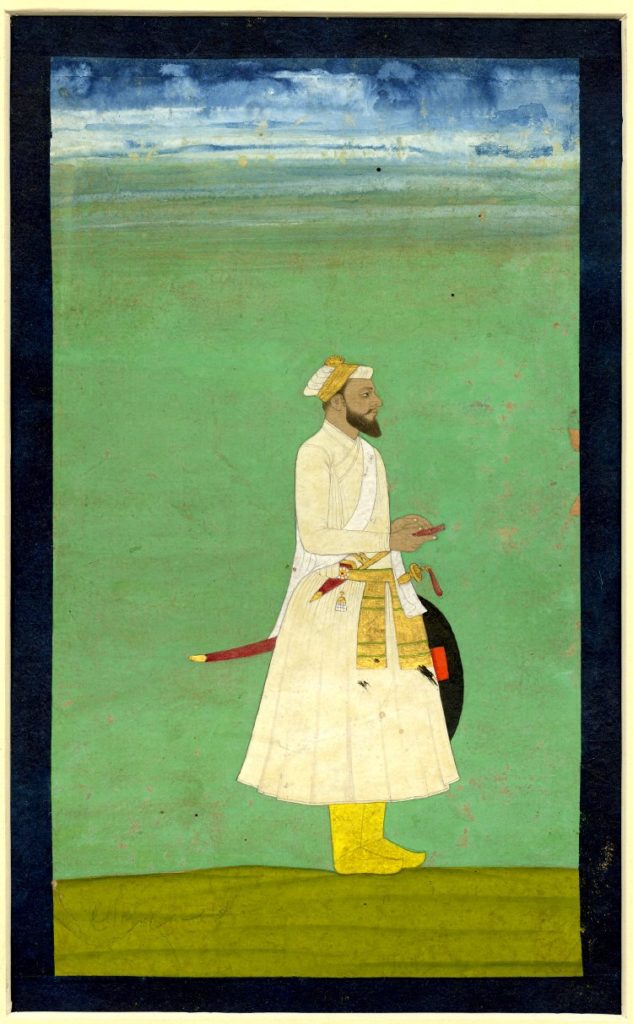

An artist’s representation of a Maratha attack

(“Instead of commencing with the removal of the existing government, and the general assumption of the whole authority to himself, a Maratha chieftain begins, by appearing at the season of harvest, and demanding a consideration for his forbearance in withholding the mischief he has it in his power to inflict. This visit is annually repeated, and the demand proportionally enhanced. Whatever is thus exacted is called the chauth, and the process of exaction a mulk-giri expedition.” (Prinsep’s History… of the Marquess of Hastings, i. 22.))

Thus, Shivaji’s power was exactly similar in origin and theory to the power of the Muslim States in India and elsewhere, and he only differed from them in the use of that power. Universal toleration and equal justice and protection were his distinctive features in the permanently occupied portion of his realm, as we have shown elsewhere.

The coincidence between Shivaji’s foreign policy and that of a Quranic sovereign is so complete that both the history of Shivaji by his courtier Krishnaji Anant and the Persian official history of Bijapur use exactly the same word, mulk-giri, to describe such raids into neighbouring countries as a regular political ideal. The only difference was that in theory at least, an orthodox Muslim king was bound to spare the other Muslim States in his path and not to spoil or shed the blood of true believers, while Shivaji (as well as the Peshwas after him) carried on his mulk-giri into all neighbouring States, Hindu no less than Islamic, and squeezed rich Hindus as mercilessly as he did Muhammadans. Then, again, the orthodox Islamic king, in theory at least, aimed at the annexation and conversion of the other States, so that after the short sharp agony of conquest was over those places enjoyed peace like the regular parts of his dominion.

-

Causes of Shivaji’s failure to build an enduring State

Why did Shivaji fail to create an enduring State? Why did the Maratha nation stop short of the final accomplishment of their union and dissolve before they had consolidated into an absolutely compact political body?

An obvious cause was, no doubt, the shortness of his reign, barely ten years after the final rupture with the Mughals in 1670. But this does not furnish the true explanation of his failure. It is doubtful if with a very much longer time at his disposal he could have averted the ruin which befell the Maratha State under the Peshwas, for the same moral canker was at work among his people in the 17th century as in the 18th. The first danger of the new Hindu kingdom established by him in the Deccan lay in the fact that the national glory and prosperity resulting from the victories of Shivaji and Baji Rao I created a reaction in favour of Hindu orthodoxy; it accentuated caste distinctions and ceremonial purity of daily rites which ran counter to the homogeneity and simplicity of the poor and politically depressed early Maratha society. Thus, his political success sapped the main foundation of that success.

In the security, power and wealth engendered by their independence, the Marathas of the 18th century forgot the past record of Muslim persecution; their social grades turned against each other. The Brahmans living east of the Sahyadri range despised those living west of it, the men of the hills despised their brethren of the plains, because they could now do so with impunity. The head of the State, though a Brahman, was despised by his Brahman servants belonging to other branches of the caste— because the first Peshwa’s great-grandfather’s great-grandfather had once been lower in society than the Desh Brahmans’ great-grandfathers’ great-grandfathers! While the Chitpavan Brahmans were waging social war with the Deshastha Brahmans, a bitter jealousy raged between the Brahman ministers and governors and the Kayastha secretaries. We have unmistakable traces of it as early as the reign of Shivaji. “Caste grows by fission.” It is antagonistic to national union. In proportion as Shivaji’s ideal of a Hindu swaraj was based on orthodoxy, it contained within itself the seed of its own death. As Rabindranath Tagore remarks :

“A temporary enthusiasm sweeps over the country and we imagine that it has been united; but the rents and holes in our body-social do their work secretly; we cannot retain any noble idea long.

“Shivaji aimed at preserving the rents; he wished to save from Mughal attack a Hindu society to which ceremonial distinctions and isolation of castes are the very breath of life. He wanted to make this heterogeneous society triumphant over all India! He wove ropes of sand; he attempted the impossible. It is beyond the power of any man, it is opposed to the divine law of the universe, to establish the swaraj of such a caste-ridden, isolated, internally-torn sect over a vast continent like India.”

(From his Rise and Fall of the Sikh Power, as translated by me in Modern Review, April 1911.)

The first danger of the new Hindu kingdom established by him in the Deccan lay in the fact that the national glory and prosperity resulting from the victories of Shivaji and Baji Rao I created a reaction in favour of Hindu orthodoxy; it accentuated caste distinctions and ceremonial purity of daily rites which ran counter to the homogeneity and simplicity of the poor and politically depressed early Maratha society. Thus, his political success sapped the main foundation of that success.

Shivaji and his father-in-law Gaikwar were Marathas, i.e., members of a despised caste. Before the rise of the national movement in the Deccan in the closing years of the 19th century, a Brahman of Maharashtra used to feel insulted if he was called a Maratha. “No,” he would reply with warmth, “I am a Dakshina Brahman.” Shivaji keenly felt his humiliation at the hands of the Brahmans to whose defence and prosperity he had devoted his life. Their insistence on treating him as a Shudra drove him into the arms of Balaji Avji, the leader of the Kayasthas, and another victim of Brahmanic pride. The Brahmans felt a professional jealousy for the intelligence and literary powers of the Kayasthas, who were their only rivals in education and Government service, and consoled themselves by declaring the Kayasthas a low caste not entitled to the Vedic rites and by proclaiming a social boycott of Balaji Avji who had ventured to invest his son with the sacred thread. Balaji naturally sympathised with his master and tried to raise him in social estimation by engaging Gaga Rhatta who “made Shivaji a pure Kshatriya”. The high-priest showed his gratitude to Balaji for his heavy retainer by writing a tract [or rather two] in which the Kayastha caste was glorified, but without convincing his contemporary Brahmans.

(Nor has he succeeded in convincing posterity. In 1916, Mr. Rajwade, a Brahman writer, published a denial of the Kayastha claims (Chaturtha Sam. Britta), on the occasion of editing this tract. He has provoked replies, one of which, Rajwade’s Gaga Bhatti by K. T. Gupte makes some attempt at reasoning and the use of evidence, while another, The Twanging of the Bow by K. S. Thakre, has the same tone as Milton’s Tetrachordon or Against Salmasius! This is happening in the 20th century, and yet Mr. Rajwade and Prof. Bijapurkar—who persistently treated Shivaji’s descendants at Kolhapur as Shudras—are nationalists, even Chauvinists. It was with a house so divided against itself that the Puna Brahmans of the 18th century hoped to found an all-Indian Maratha empire, and there are Puna Brahmans in the 20th century who believe that the hope failed only through the superior luck and cunning of the English!)

There was no attempt at well-thought-out organised communal improvement, spread of education, or unification of the people, either under Shivaji or under the Peshwas. The cohesion of the people in the Maratha State was not organic but artificial, accidental, and therefore precarious. It was solely dependent on the ruler’s extraordinary personality and disappeared when the country ceased to produce supermen among its rulers.

A Government of personal discretion is, by its very nature, uncertain. This uncertainty reacted fatally on the administration. However well-planned the machinery and rules might be, the actual conduct of the administration was marred by inefficiency, sudden changes, and official corruption, because nobody felt secure of his post or of the due appreciation of his merit. This has been the bane of all autocratic States in the East and the West alike, except where the autocrat has been a “hero as king” or where a high level of education, civilization and national spirit among the people has prevented the evil.

There was no attempt at well-thought-out organised communal improvement, spread of education, or unification of the people, either under Shivaji or under the Peshwas. The cohesion of the people in the Maratha State was not organic but artificial, accidental, and therefore precarious. It was solely dependent on the ruler’s extraordinary personality and disappeared when the country ceased to produce supermen among its rulers.

-

Hindrances to true nationality in Shivaji’s age

The society of Shivaji’s age and country was so different from our own that some straining of the historical imagination is necessary before we can understand the difficulties that he had to combat.

Land was the only stable thing in an ever-changing world subject to the appalling outbursts of nature’s forces, which swept away man and his handiwork, and the even more violent transformations of political revolution. But the new conquerors always left the land to the old peasant because he alone could till it in that age of sparse population, and they continued the revenue collection in the hands of the old hereditary middleman, because they alone knew the details of the locality and could ensure some payment from the land to a distant sovereign who would have found it impossible to collect his dues from each petty tiller of the soil directly. The offices in connection with land, therefore, tended to become hereditary and the contractor of revenue blossomed in time into a landowner with a permanent family claim to a portion of the yield of his village or district. Attachment to one’s ancestral land was the strongest passion in the age of little trade and small scale industries. I know of a Brahman family which migrated from the Ratnagiri district to Ahmadabad six generations ago and no longer owned an inch of land in their ancient home nor keep any business connection with it, and yet they have carefully preserved for two centuries the old title-deeds of their long-abandoned lands.

And in that age land rights were unsettled and perplexing by reason of the variety and complication of the personal claims to one and the same tract. Illustrations of this state of things can be found almost everywhere in the Deccan; I give the case of Savant-vadi as readily available in print. In this small region there was in the 16th century a desai (or zamindar) of the Prabhu caste at Kudal for collecting the revenue on behalf of the Bijapur Sultan, with a dalvi or captain of the Rajput caste under him to lead his troops. The dalvi rebelled against his master the desai and sought the help of a neighbouring savant or chief of the Maratha caste. At first the desai suppressed the rebel with the support of his sovereign. But in the third generation an able savant rose to power, secured the desai-ship of Banda from Adil Shah, and after extirpating most of the Prabhu desais annexed the Kudal pargana. But some members of the dispossessed family escaped and revived their claim of land. Next, Shivaji stepped in to oust the savant! Further complications were introduced by two branches of the same family (often two brothers) fighting for the same estate and transmitting their disputes to their sons and grandsons.

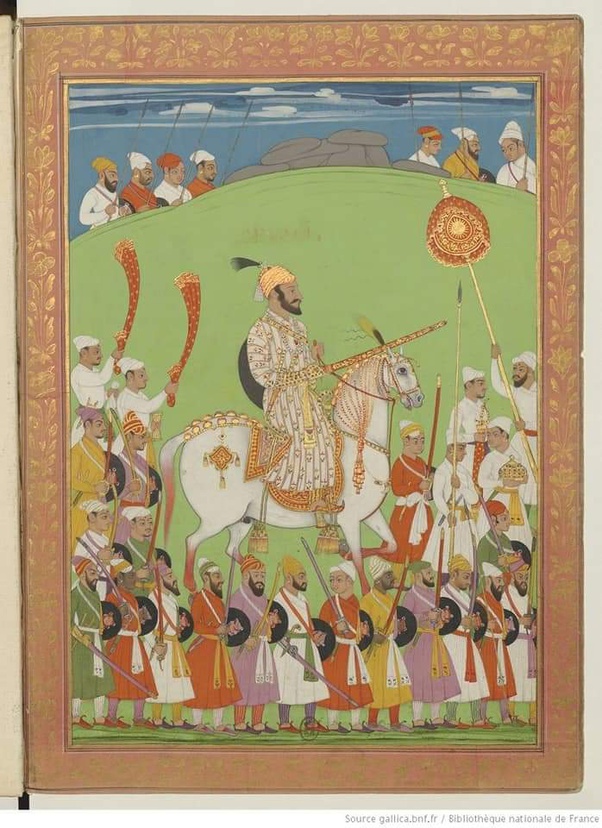

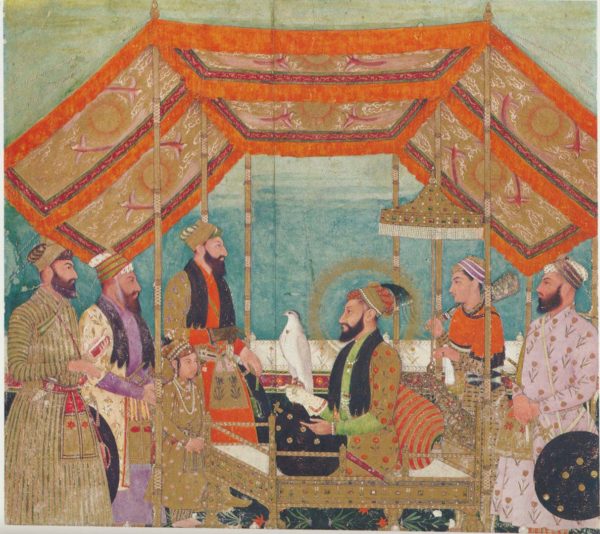

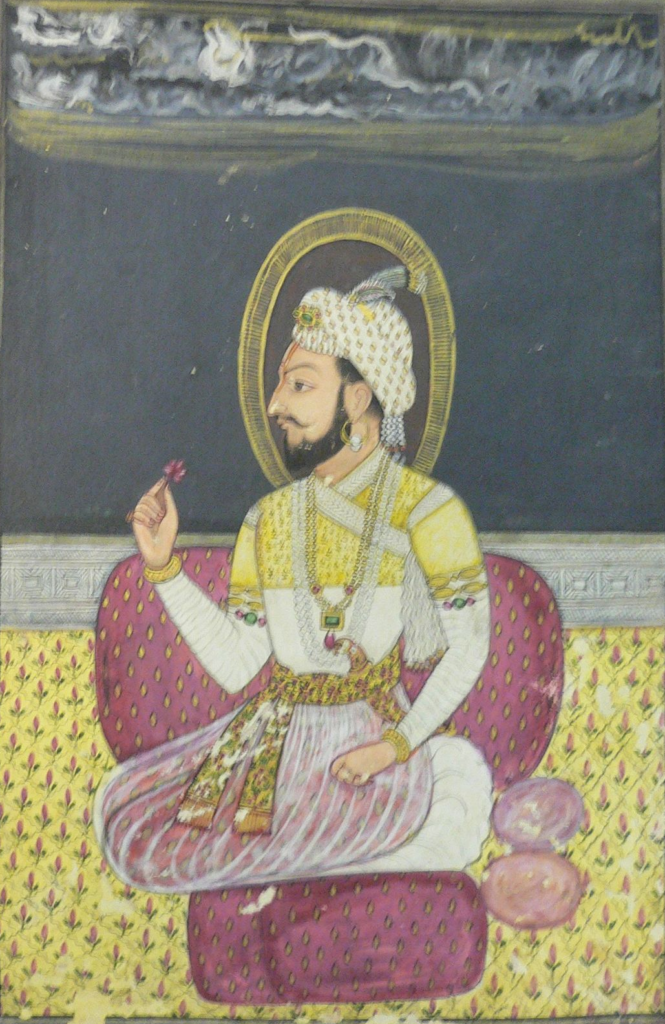

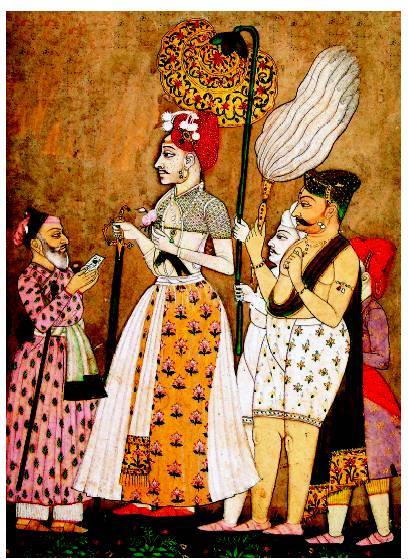

Shivaji by Mir Mohammad (Courtesy: National Library of France)