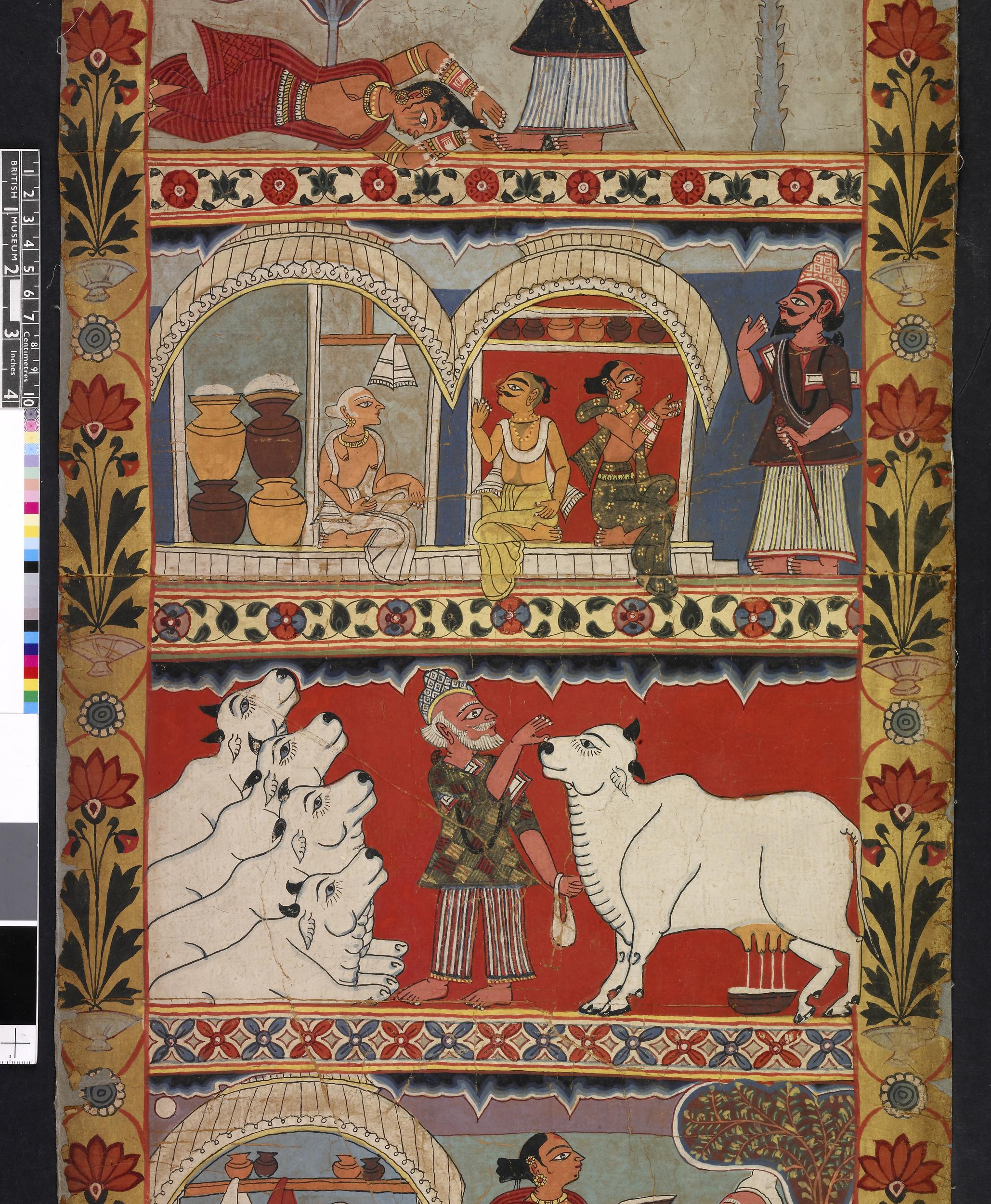

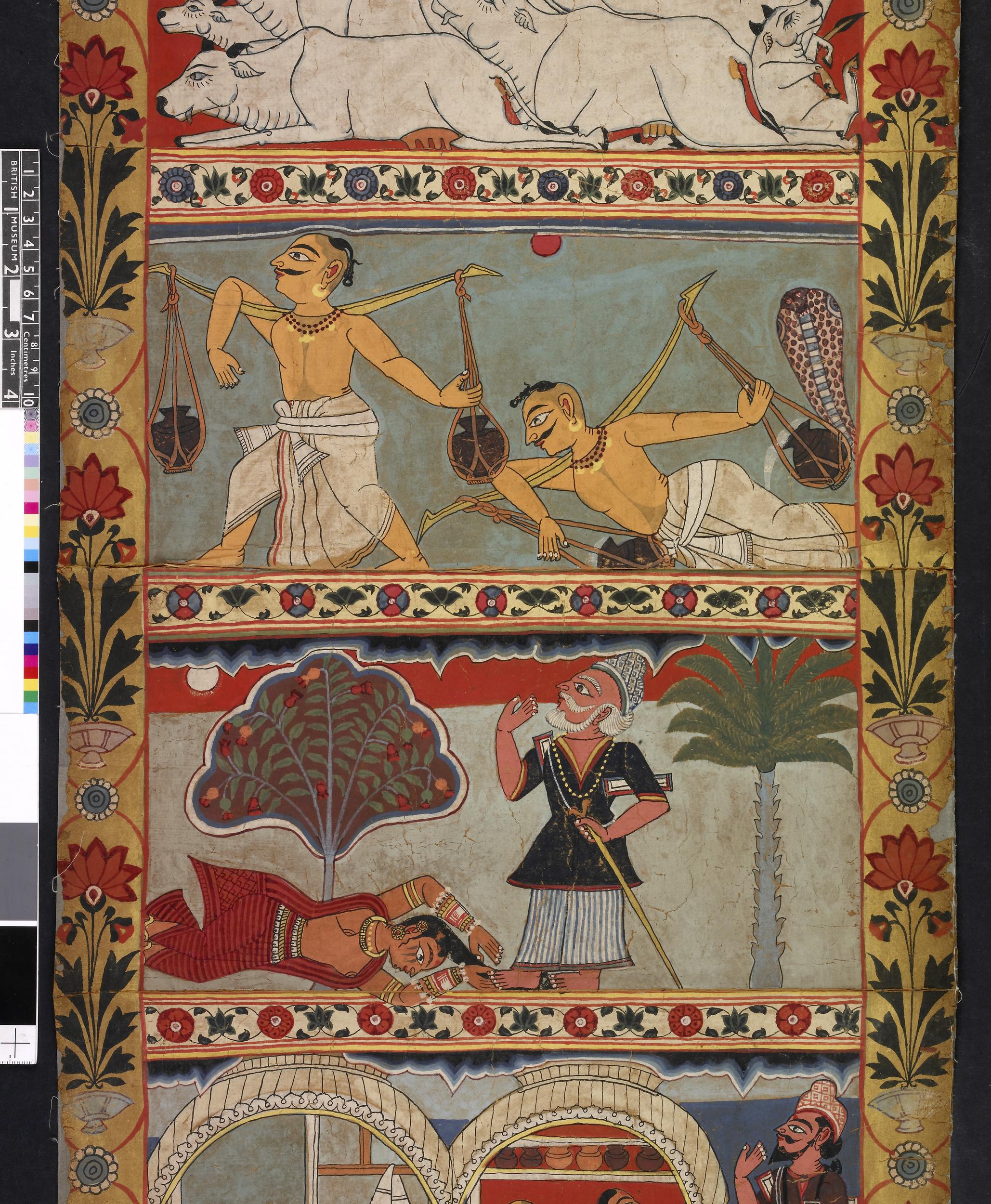

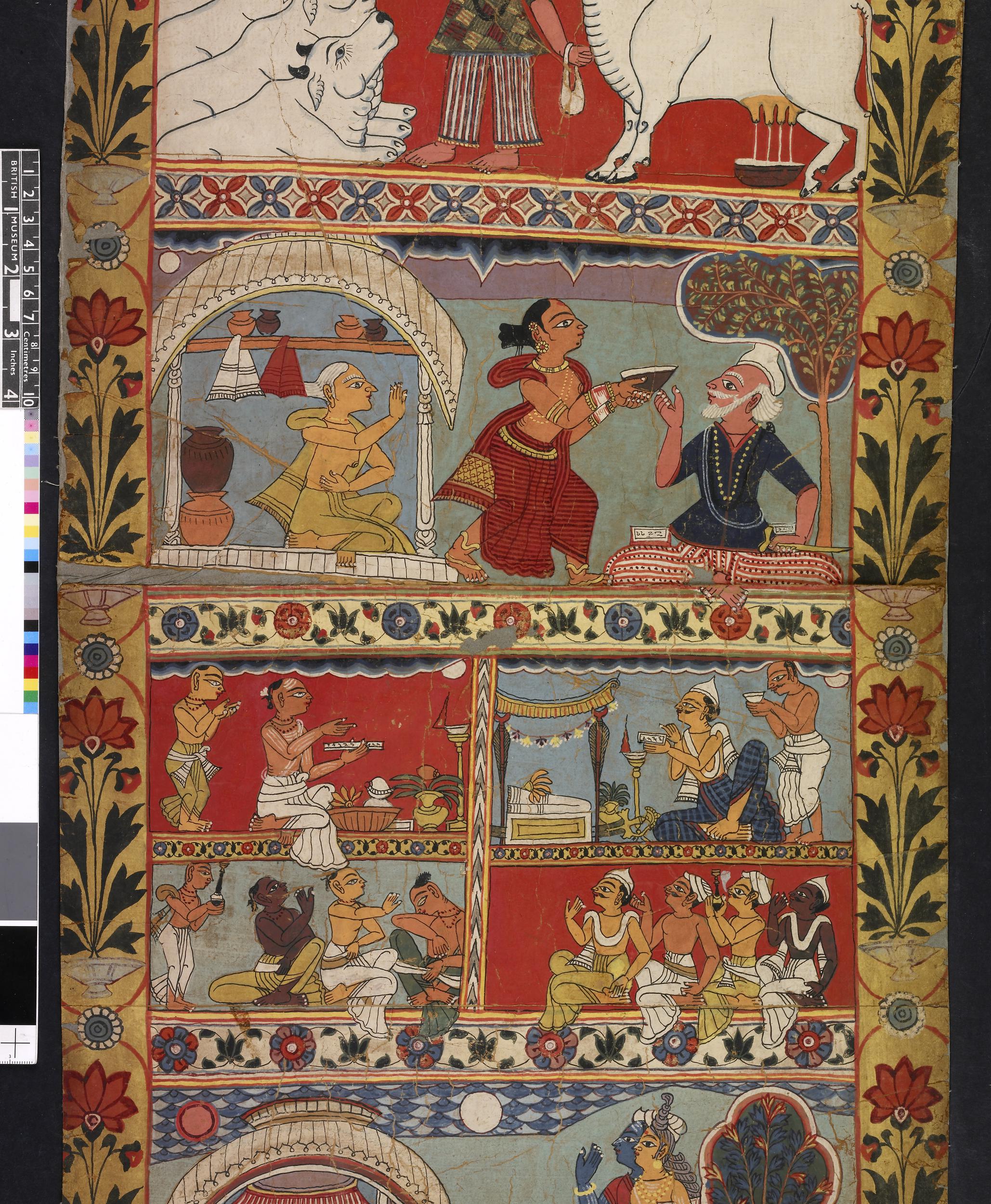

Pir Gazi on a painted scroll or ‘pata’ – circa -1800, Murshidabad. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Bengali Muslims constitute the world’s third-largest Muslim ethnicity and the largest ethnicity of Muslims in South Asia.

This was not always the case.

In fact, one of the great conundrums of Bengali history is that despite Muslim regimes ruling the region since the 13th century, no noticeable community of Muslim cultivators emerged alongside them. The Muslim population in Bengal till the 16th century was quite small and remained confined to urban centres. The Bengali Muslim cultivator class began to emerge only under 16th-century Mughal rule, which was strictly against any sort of conversion/proselytism. So, how exactly did Bengal become Muslim?

In this classic essay “Who are the Bengal Muslims?: Conversion and Islamicization in Bengal’, esteemed historian Dr. Richard M. Eaton attempts to answer the question.

But before moving on to Dr. Eaton’s theory we must pay heed to what Dr. Romilla Thapar writes in her Introduction to the “Public Intellectual in India”. She writes “The scrambling together of religious sects into a monolithic Hinduism and a monolithic Islam, and the confrontation of these two monolithic religions communities, and their projection back in history as maintained in colonial times, was a departure from existing religious self perception.” What she is arguing here is that communities in the past understood religious identity radically differently than we do. They did not see themselves as being singularly defined by the sealed-off religious categories of Hindu and Muslim. Therefore, in studying past communities, an attempt must be made to understand them in their own context.

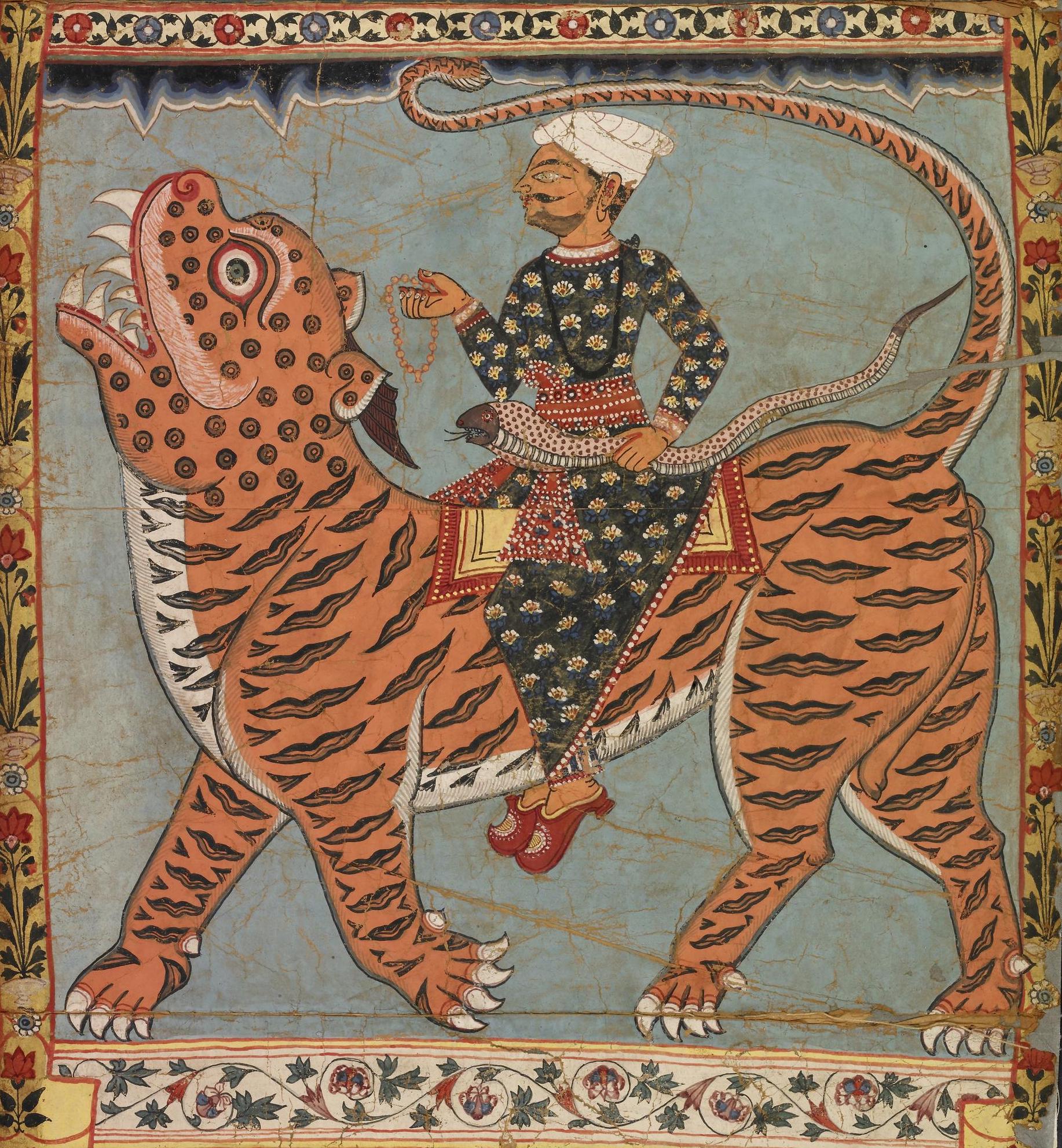

Similarly Dr. Eaton states that in the pre-modern Bengal frontier Islam entered as “ a fluid context in which Islamic superhuman agencies… gradually seeped into local cosmologies that were themselves dynamic. This ‘seepage’ occurred over such a long period of time that one can at no point identify a specific moment of ‘conversion’” . This fact is also corroborated by the images from a ‘pata’ or a painted scroll (circa 1800, Murshidabad) displayed throughout this excerpt. Sourced from the British Museum, the painted images from the scroll tell stories of the miracle-working saints or ‘pirs’—Gazi and Manik. The curator’s comments tell us how the religious cosmologies of Bengal prior to colonisation were not sharply divided in the binary between Hinduism and Islam. While noting the Bengali Islamic symbolism in the paintings the curator cautions that “It is important to record that Hindus also appear scattered throughout the narrative, reflecting the historically mixed and interpenetrated nature of Bengal society, especially in the countryside. At one point we see a blue-coloured male figure accompanied by a female, who are presumably Radha and Krishna in the mystically joined form popularized by Chaitanya. This reminds us that in the early modern period Bengali authors, writing of figures such as the holy men seen in this scroll-painting, have suggested that the gods of the Puranas, above all Krishna, and the god of the Qur’an are one and the same and should thus receive the equal homage of the people.”

Moving back to our central question, however—who were the Bengali Muslims?—we find in Dr. Eaton’s essay that contrary to popular belief, Islam in Bengal was not a product of proselytisation but a matter of environmental, socio-economic and temporal specificities of Bengal in the 16th century. In telling the story of how a specific community of Bengali Muslim cultivators emerged in this period, Dr. Eaton is asking us to question the more simplistic prevailing narrative of “forced conversion” and “manipulation” being at the root of Islam’s rise in the subcontinent.

His main argument, which is expanded in the excerpt below, is that the rise of the cultivator class of Bengali Muslims can be traced to the clearing of forest areas in Eastern Bengal for agricultural purposes. The Mughal land policy, which was geared towards taxes from land and exports, incentivised this activity by providing parcels of tax-free land to yeoman Sufis and other religious persons of the region, who went into the forest and recruited indigenous people of the Eastern Delta to do this labour with them. They also, it must be imagined, convinced the indigenous people to settle in this land and practice agriculture.

Another factor that facilitated this process was a change in the trajectory of the river Ganga that happened in the 16th century. This connected it with the river Padma and allowed riverine access straight to the heart of the Eastern Delta from the West. Before this, the lack of riverine access had restricted Indo-Aryan influence in the Eastern delta. The exports, especially to Spain and Portugal, flooded the local markets, with New World silver allowing an enriched local economy to fund an even more rapid push of the agrarian frontier.

The indigenous people settled on this newly deforested area over generations and were incorporated into an Islamic cosmology. There was a slow evolution of local Islam around the cultivators’ socio-economic realities and earlier cultural practices. Their Islam was radically different from the Ashraf Islam of the North Indian Persio-Arabic variety. For example, while Ashrafs found cultivation to be a degraded occupation (like other Hindu upper castes), here the cultivators’ Islam distinguished itself significantly from the former, by arguing theologically that cultivation was the natural occupation given to the first man, Adam. North Indian Mughal administrative or military elite in Bengal or Ashraf classes thought of themselves as North Indian foreigners in alien land. They had much more in common with Rajputs than Bengali Muslims. To quote Dr. Eaton, “They (Mughals) had virtually become Rajput themselves.” To them, the Bengali muslims were a different social category altogether. Contemporaneous foreign accounts corroborate this view of the Bengali cultivators by the Ashraf Muslims. The 16th century Portuguese priest Fray Sebastien Manrique, corroborated this view when describing the three groups that composed Bengal’s population “the Portuguese, the Moors, and the natives of the country.”

This essay further elaborates on the nuances that make India the country it is and has been reproduced with generous permission from the Oxford University Press, India. It first appeared in Rafiuddin Ahmed, ed., Understanding Bengali Muslims: Interpretative Essays (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2001), 26-51.

A striking feature of Islam in pre-modern Bengal is the cleavage that emerged between a folk Bengali variant, which was built upon indigenous roots, and a variant practiced and patronized primarily by urban-dwelling, ashraf classes. This divide lay behind the nineteenth century reform movement and contributed to the twentieth century upheavals that led first to the inclusion of eastern Bengal in the state of Pakistan, and ultimately to its secession from that state. The present essay examines the evolution of the Bengal Muslims between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, a period when evidence of the religious culture of both ashraf and non-ashraf communities is especially well-documented. It also explores why and how Islam became the dominant religious tradition in Bengal but not in upper India, the epicentre of Indo-Muslim political culture, and in the eastern, but not. the western, portion of the Bengal delta.

In the Bengali context, the ashraf generally included those Muslims claiming descent from immigrants from beyond the Khyber- or at least from beyond Bengal- who cultivated high Perso- Islamic civilization and its associated literatures in Arabic, Persian, and Urdu. Soon after the Turkish conquest of the delta in 1204, Muslim immigrants from points west settled in cities like Gaur, Pandua, Sargaon, Sonargaon, and Chittagong, principally as long-distance traders, administrators, soldiers, and literati. But from 1342 to 1574, under the rule of a succession of independent Muslim dynasties, Bengal became isolated from north India, and immigration from points west was largely curtailed. In the wake of the Mughal conquest of 1574, however, Muslim immigrants from north India once again settled the delta, in such numbers that it was their understanding of Islam that came to define ashraf religious sensibilities in modern Bengali history.

Although the Mughals had originated in fifteenth century Central Asia, by the time they conquered Bengal in the late sixteenth century they had already assimilated the political traditions of north India, a process accelerated by Akbar’s policy of admitting Rajputs into his ruling class. In fact, they had become virtual Rajputs themselves. In the early seventeenth century, for example, we already hear of Muslim officers in Bengal indulging in the Rajput practice of jühar, the destruction of women and children as an alternative to suffering their capture by an enemy. The Mughals in Bengal also preferred Ayurvedic medical therapy to the Yunani system inherited by medieval Islamic civilization.

Islam Khan, the first governor to establish permanent Mughal dominion in the delta, sent for an Indian physician when he fell terminally ill in 1613. As one was not available, the Governor only reluctantly accepted the services of a Muslim healer (hakim), who was later blamed for having administered the wrong treatment and unnecessarily killing him. Reliance on Indian systems of medical theory in the face of fatal illness, and on Rajput customs when faced with immanent annihilation in battle both of them life-threatening situations suggests the degree to which Indian, and especially Rajput, values had penetrated Mughal culture by the early seventeenth century.

Conversely, from the Mughal-Rajput perspective Bengal was a distinctly alien land. Abu’l-fazl, Akbar’s chief counselor and ideologue, described the region as a house of turbulence (bulghik-khana). As he wrote in 1579, shortly after Akbar’s armies had seized the province from its Afghan rulers,

The country of Bengal is a land where, owing to the climate’s favouring the base, the dust of dissension is always rising. From the wickedness of men families have decayed, and dominions ruined. Hence in old writings it was called Bulghak-khana (house of turbulence).

In effect, we have here a theory of socio-political decay: an enervating climate corrupts men, corrupted men ruin sovereign domains and, implicitly, ruined domains pave the way for conquest by more virile, manly races. In its linking of Bengal’s climate with the debased behaviour of the people exposed to it, Abu’l-fazl’s theory of decay at once recalls similar views later adopted by British colonial officials.’

‘Pata’ or a painted scroll circa 1800 -Murshidabad © The Trustees of the British Museum

The Mughals’ alienation from the land was accompanied by feelings of superiority or condescension toward its people. Especially in matters of language, dress, or diet, officials newly arrived to the delta experienced profound differences from the North Indian culture to which they had been accustomed. The Bengali diet of fish and rice, for example, contrasted sharply with the wheat and meat diet of the Punjab and seems to have posed a special stumbling block for immigrants. At the same time, Mughal officers associated Bengalis with fishing, a mode of life they despised. Around 1620 two Mughal officers, aiming to belittle the martial accomplishments of one of their comrades, challenged the latter with the words: ‘Which of the rebels have you defeated except a band of fishermen who raised a stockade at Ghalwapara? In reply, the other observed that even the Mughals’ most formidable adversaries in Bengal, ‘Isa Khan and Musa Khan, had been fishermen. ‘Where shall I find a Dawud son of Sulayman Karrani to fight with, in order to please you?’ he asked rhetorically, and with some annoyance, adding that it was his duty as an imperial officer to subdue all imperial enemies in Bengal, ‘whether they are Machwas [fishermen] or Mughals or Afghans’. This exchange reveals the notion that the only opponents truly worthy of the imperial forces were Mughal rebels or Afghans like the recently-defeated Karranis; Bengalis, being fishermen, apparently occupied a separate category of less worthy adversaries.

Mughal officials thus saw themselves as the land’s natural rulers, distinguished from Bengalis not only as tax-receivers as opposed to tax-payers, but as north Indian fighting men as opposed to docile fishermen. On one occasion Governor Islam Khan’s chief naval officer, Ihtimam Khan, expressed resentment that the Governor had treated him and his son like ‘natives’. The idea that ashraf Muslims occupied a social category altogether separate from the ‘natives’ was echoed in the observation of an outside observer, Fray Sebastien Manrique, who in 1629 described Bengal’s population as composed of three groups ‘the Portuguese, the Moors, and the natives of the country’. According to this system of social classification, Muslims were, by definition, foreigners to the land. The idea that ‘natives could also be ‘Moors’-that is, that there could be Bengali Muslims was, from the perspective of members of the urban, Mughal ruling class whom Manrique met, conceptually impossible.

Regarding the religion of the Mughal ashrāf, three features stand out: (a) a special link with the pan-Indian Chishti order, (b) a conceptual separation of religion and state, and (c) a disinclination to convert Bengalis to Islam. Most Muslims in the imperial corps brought to Bengal styles of Islamic piety that had already evolved in north India during the preceding century. We can glimpse a profile of this piety from the remarks of Mirza Nathan, a middle-level imperial officer whose unofficial memoir is filled with references to witchcraft, astrology, and notions of the paradisiac afterlife associated with Mughal soldiers he called ghazis. All of these elements were well integrated into his worldview. Above all, Nathan’s religion was characterized by a vivid sense in which Allah mediated his blessings to believers through the agency of saints. These, however, were not the village pirs who played such important roles in the world of rural Bengalis, but shaikhs belonging to the Chishti order of Sufism, the order most clearly associated with Mughal, and before that, Tughlug imperialism. This was also the most authentically Indian of Sufi brotherhoods, its wealth and power centred on the enormous cults based on the tomb-shrines of north Indian saints such as Muin al-Din Chishti (d. 1236) in Ajmer, Rajasthan; Nizam al-Din Auliya (d. 1325) in Delhi; or Farid al-Din Shakarganj (d. 1265) in Pakpattan, Punjab. Since the Tughlug period, this order enjoyed a very special status among Delhi’s rulers, who lavishly patronized the descendants of the great Chishti shaikhs with magnificent tombs and considerable tax-free land. Mirza Nathan was himself a ‘faithful disciple’ (murd-i bandag) of Farid al-Din Shakargani, probably because the writer’s ancestors had come from the Punjab where Baba Farid’s cult was especially prominent. Moreover, Islam Khan, Bengal’s first permanent governor (1608-13) and the man most responsible for consolidating Mughal rule in Bengal, was the grandson of Akbar’s chief spiritual guide, Shaikh Salim Chishti. It was on this account that the Governor on one occasion referred to Sufism as ‘our ancestral profession’ (fagin ki kasb-i buzurgun-i mast). One feature of ashraf piety, then, was a close and enduring connection with the Chishti order.

Second, ashraf Muslims conceptually distinguished religion and state, which was reflected, among other ways, in a functional specialization of their cities. As a provincial capital and administrative centre, Dhaka was primarily devoted to revenue collection, administration, politics, and military reviews. The city was also involved in considerable trade and money-making. Fray Manrique, who was there in 1640, wrote that merchants of Dhaka have raised the city to an eminence of wealth which is actually stupefying, especially when one sees and considers the large quantities of money which lie principally in the houses of the Cataris (Khatri), in such quantities indeed, that, being difficult to count, it is usually commonly to be weighed. In short, Dhaka was a secular city. Even its most imposing mosques, such as the Satgumbad Mosque (ca. 1664-76) or the mosques of Haji Khwaja Shahbaz (1679) and Khan Muhammad Mirza (1704), bear the stuccoed stamp of their north Indian patrons, and seem intended more to display imperial power than to inspire piety.

On the other hand the ancient capitals of Gaur and Pandua, denied any political significance under the Mughals, emerged under their rule as Islamic sacred centres. The sanctity of Gaur focussed in part on the Qadam Rasul, a reliquary established by Sultan ‘Ala al-Din Husain Shah in 1503, containing a dais and black marble stone purporting to bear the impression of the Prophet’s footprint. But the shrines most lavishly patronized by the Mughals were the older and more important shrines in nearby Pandua-the tombs of Shaikh ‘Ala al-Haq (d. 1398) and Shaikh Nur Qutb-i ‘Alam (d. 1459). Both shaikhs were members of the Chishti order; in fact, they were the most prominent Chishtis ever to have settled in Bengal. The shrine of Nur Qutb-i’Alam had been the object of state patronage ever since the son and successor of Sultan Jalal al-Din Muhammad (r. 1415-32), Sultan Ahmad (r. 1432-33), became a disciple of the famous shaikh. By the end of the fifteenth century it had become the focus of annual pilgrimages performed by Sultan ‘Ala al-Din Husain Shah (r. 1493-1532). A century later, in 1609, the Mughal officer Mirza Nathan made a three-day pilgrimage to the shrine, having vowed to do so should his father recover from an illness. And on the occasion of his own marriage, he made a pilgrimage to Gaur’s Qadam Rasul and Pandua’s shrine of Shaikh ‘Ala al-Haq. Later, while in Bengal in 1624, the future emperor Shah Jahan distributed Rs 4,000 at Nur Qutb-i ‘Alam’s shrine, his largest cash contribution in all of Bengal.

Thirdly, ashraf Muslims in Bengal adopted a strictly hands-off policy toward the non-Muslim society that surrounded them everywhere. Unlike the contemporary Ottoman Empire where non-Muslim military recruits were converted to Islam as part of their assimilation into the ruling class, in India non-Muslims were given full admission into the Mughal officer corps as non-Muslims. What bonded together Mughal officers of diverse cultures was not a common religion, then, but the ideology of ‘salt,’ the ritual eating of which served to bind people of unequal sociopolitical rank to mutual obligations: the higher-ranked person swore to protect the lower, in return for which the latter swore loyalty to the higher. Such bonds of loyalty among Mughal officers not only ran across religious or ethnic communities, but persisted over several generations. At the same time, when making vows or swearing oaths, members of the imperial corps appealed to different deities according to their particular religious identities. On one occasion, a copy of the Qur’an and a black geode worshiped in the form of Vishnu (salagram) were brought to a mixed group of Mughal officers about to swear on oath. Placing their hand on the Qur’an, the Muslim officers took solemn oaths in the name of Allah; while the Hindu officers, placing their hand on the geode, did the same in the name of Vishnu.

‘Pata’ or a painted scroll circa 1800 -Murshidabad © The Trustees of the British Museum

The invocation of a Hindu deity in this political ritual shows that, unlike the early Sultans of Bengal, Mughal officials did not patronize Islam as a state religion. Except for a brief episode of anti-Hindu persecution in the early 1680s, Bengal’s rulers maintained a strictly non-interventionist position in religious matters, despite pressure from local religious functionaries (mullas) and Sufis to support Islam over other religions. This point is seen most dramatically in the way local judges adjudicated disputes between Hindus and Muslims. In August 1640, a Bengali Muslim was brought before the judge (shiqdar) of Naraingarh in modern Midnapur District, having been accused of violating the religious sensibilities of nearby Hindu villagers by killing and eating a couple of peacocks. Turning to the accused, the judge, himself a Bengali Muslim, asked, ‘Art thou not, as it seems, a Bengali and a Musalman…? How then didst thou dare in a Hindu district to kill a living thing?’ The judge then explained that sixty-six years earlier, when the Mughals conquered Bengal, Akbar had given his word ‘that he and his successors would let [Bengalis] live under their own laws and customs: he [the judge] therefore allowed no breach of them.’ With that, the judge ordered the accused to be whipped. The larger point, of course, is that the Mughals were determined not to allow religion to interfere with their administration of Bengal.

One consequence of this hands-off policy was that Mughal officials refused to promote the conversion of Bengalis to Islam. Islam Khan is known to have discouraged the conversion of Bengalis and on one occasion actually punished one of his officers for allowing it to happen. In 1609 when the Governor’s army was moving across the present Bogra region subduing hostile chieftains, one of his officers, Tuqmaq Khan, defeated Raja Ray, the landholder (zamindar) of Shahzadpur. Shortly after this, Tugmag Khan employed the son of the defeated raja as his personal servant and at the same time converted him to Islam. This news deeply annoyed the Governor, who punished Tuqmaq Khan by transferring him from his jagir.” Clearly, the Governor did not view government service as a reward for conversion to Islam; to the contrary, in this instance the man responsible for causing the conversion was censured and transferred. Moreover, it was not only Islam Khan who opposed the conversion, but also ‘the other officers of the State, suggesting that the hands-off policy was a general one.

This observation points to one of the great paradoxes of Bengali history, namely, that although Muslim regimes had ruled over Bengal since the early thirteenth century, a noticeable community of Muslim cultivators did not emerge there until the late sixteenth century, under: a regime that did nothing to encourage the conversion of Bengalis to Islam and in fact opposed such conversions. Communities of Muslim cultivators were first reported in the Dhaka region in 1599, at a time when the balance of power in that region was gradually shifting from powerful zamindars like ‘Isa Khan and the other so-called twelve chieftains (bara bhagan), to Mughal imperial authorities. Communities of Muslim cultivators were first reported in the Noakhali region in the 1630s, and in the Rangpur region in the 1660s.

It is significant that the areas where communities of Muslim cultivators were first noticed —Dhaka, Noakhali, Rangpur — are located in the eastern half of the Bengal delta, and not the western delta. The reasons for this appear related to the extraordinary economic growth that the eastern delta was then experiencing relative to the west. Prior to the sixteenth century, eastern Bengal had been a heavily forested region that, being isolated from the main centres of Brahmanic culture, had been only lightly touched by Indo-Aryan civilization. Archaeological data on the distribution and relative size of Bengal’s ancient urban centres show that, between the Mauryan and Sena periods (fourth century BC-AD twelfth century), the western delta was more densely populated than the east. Greater urbanization suggests greater occupational specialization and social stratification. As a result, prior to the Turkish conquest of 1204, western Bengal had become far more deeply penetrated by Indo-Aryan civilization generally, and in particular by Brahman settlement and the diffusion of Brahmanic notions of hierarchical social organization and caste specialization. Around 1590, the poet Mukundaram, a native of Burdwan, described the highly elaborated caste society that by that time had appeared in western Bengal. No such evidence exists for the east.

Two major obstacles inhibited the advance of Brahmanical society into the eastern delta: heavy forestation, and an absence of direct riverine contact with upper India. Today, West Bengal gets about 55 inches of rain annually, whereas central and eastern Bengal get 60 inches to 95 inches, with the mouth of the Meghna receiving from 100 inches to 120 inches and eastern Sylhet about 150 inches. Assuming this climatic pattern held in ancient times, the density of vegetation in the delta’s hinterland, formerly covered with thick forests of sal would have increased dramatically as one moved eastward. Cutting and clearing the land would have required much more labour and organization, even with the aid of iron implements, than was the case in the less densely forested westerly regions. The other obstacle to economic growth in the east was its isolation from the great Ganges river system. In ancient times, the Ganges flowed down the delta’s western corridor though the present Bhagirata-Hooghly channel, emptying into the Bay near Calcutta, where the river is still known as the Adi-Ganga, ‘original Ganges’. This left eastern Bengal disconnected from the Ganges system. Due to continual sedimentation, however, the Ganges in very early times began to spill out of its former river-bed and find new channels to the east — the Bhairab, the Mathabhanga, the Garai-Madhumati, the Arialkhan- until finally, in the late sixteenth century, it linked up with the Padma, enabling its main course to flow directly into the heart of East Bengal. European maps dated 1548, 1615, 1660, and 1779 clearly show this riverine movement.

The implications of the Ganges’s eastward migration, moreover, were far-reaching. For one thing, it linked eastern Bengal’s economy with wider markets since it opened up a heavily forested and formerly isolated region to direct commercial contact with upper India. More importantly, however, the great river’s eastward migration carried with it the epicentre of Bengali civilization, since its annual flooding deposited the immense loads of silt that made possible the cultivation of wet rice, which in turn could sustain ever larger concentrations of population. Changes in the Mughal revenue demand between 1595 and 1659 reflect the changes in the relative fertility of different parts of the delta, since such figures were based on the capacity of the land to produce grain. Over the course of those sixty-four years, revenue demand jumped by 117 per cent in the delta’s most ecologically active southeastern region, and by 97 per cent in the northeast. On the other hand, it increased by only 54 per cent in the less active southwest, whereas in the ecologically moribund northwest it actually declined by 13 per cent.

Moreover, the merger of the Ganges with the Padma occurred at the very moment that the whole of Bengal was absorbed into one of the largest imperial systems ever seen in South Asia–the Mughal Empire under Akbar. Unlike earlier Muslim rulers of Bengal, who situated their capitals in the northwestern delta (i.e., Gaur, Pandua, Tanda), the Mughals in the early seventeenth century planted their provincial capital in the heart of the eastern delta, Dhaka. This meant that for the first time ever, eastern Bengal, formerly an underdeveloped, inaccessible, and heavily forested hinterland, became the focus of concerted and rapid political and economic development. In fact, already by the late sixteenth century Bengal was producing so much surplus grain that rice emerged as an important export crop, which had never before happened. From two principal seaports, Chittagong in the east and Satgaon in the west, rice was exported throughout the Indian Ocean to points as far west as Goa and as far east as the Moluccas in Southeast Asia. Although the eastward export of rice declined after about 1670, in lower Bengal it remained cheap and abundant throughout the seventeenth century and well into the eighteenth. In this respect, rice now joined cotton textiles, the delta’s principal export commodity since at least the late fifteenth century, and a major one since at least the tenth. It was the delta’s textile industry, of course, that attracted Portuguese, Dutch, and English merchants, and by the end of the seventeenth century, Bengal had emerged as Europe’s single most important supplier of goods in all of Asia. In exchange for manufactured textiles, both European and Asian merchants poured into the delta substantial amounts of silver which, minted into currency, fueled the booming agrarian frontier by monetizing the local economy.

In the ecologically active portions of the delta, and more particularly on the cutting edge of East Bengal’s agrarian frontier, the pivotal figure was the forest pioneer, tied economically to the land and politically to the expanding Mughal state. Concerned with bringing stability to their turbulent and undeveloped eastern frontier, the Mughals did more than plant their provincial capital in the heart of the eastern delta. They also granted favourable or even tax-free tenures of land to industrious individuals who were expected to clear and bring into cultivation undeveloped forest tracts. The policy was intended to promote the emergence of local communities that would be both economically productive and politically loyal. Every recipient of such grants, Hindu or Muslim, was required to support his dependent clients and to pray for the long life of the Mughal state. Hundreds of Mughal records dating from the mid-seventeenth century down to the advent of British power in 1760 document these pioneers’ steady push into virgin jungle and their recruitment of local peoples to clear the jungle and bring the land into rice cultivation. Because they mobilized local labour for these purposes, these men played decisive roles in the socio-economic development of the eastern delta. Through their agency, much of this region witnessed either the introduction or an intensification of wet rice cultivation, while local communities formerly engaged mainly in hunting, fishing, or shifting agriculture began devoting more time to full-time wet-rice peasant agriculture.

These pioneers also played decisive roles in the religious development of the region, since one of the conditions for obtaining a grant was to build on the land a mosque or temple, to be supported in perpetuity out of the wealth produced on site. Grants made out to Hindu institutions (e.g., brahmottar, devottar, vishnottar, sivottar) tended to integrate local communities into a Hindu-ordered cultural universe, whereas grants authorizing the establishment of mosques or shrines tended to integrate such communities into an Islamic-ordered cultural universe. Subsequent demographic patterns evolved from these earlier processes. Since most pioneers were Muslims, however, mosques comprised the majority of institutions established, with the result that the dominant mode of piety that evolved on East Bengal’s economic frontier was Islamic. To be sure, the mosques themselves were not architecturally comparable with the great stone or brick religious monuments that the Mughals built in the cities. They were, rather, humble structures built of thatching and bamboo.

‘Pata’ or a painted scroll circa 1800 -Murshidabad © The Trustees of the British Museum

Nonetheless, such simple structures exercised considerable influence among the indigenous peoples of the eastern delta. For one thing, long after the founding pioner died, the mosque he had built would continue to diffuse Islamic religious ideals amongst local communities, since Qur’an readers, callers to prayer, and preachers were also supported in perpetuity according to terms specified in the foundational grants. Furthermore, by the Mughal period the peoples of rural eastern Bengal, unlike those of the more Hinduized western delta, had not yet been integrated into a rigidly-structured caste society informed by Brahmanical notions of hierarchy and order. That is, they were not yet ‘Hindu,’ meaning that in much of the eastern delta rice agriculture and Islam were introduced simultaneously and grew together, both of them focused on these humble mosques. As a result, many pioneers who had obtained the land grants, mobilized labour, and founded these institutions passed into subsequent memory as powerful saints, or pirs. In not a few cases, tomb cults grew up on their gravesites.

The religious authority possessed by the hundreds of tiny mosques and shrines that sprang up along the eastern frontier was further enhanced by the simultaneous diffusion of papermaking technology. Traceable to the fifteenth century and unmistakably identified with Islamic civilization–the ordinary Bengali for ‘paper’ (kagaj) and ‘pen’ (kalam) are both Perso-Arabic loan words the new technology fostered attitudes that endowed the written word with an authority qualitatively different from oral authority. With the proliferation of books and the religious gentry in the countryside, a ‘culture of literacy” began to spread far beyond the Mughal state’s bureaucratic sector or the delta’s urban centres. Contemporary government documents confirm that Qur’an readers were attached to rural mosques and shrines as part of their endowments, while Bengali sources dating from the fifteenth century refer to the magical power popularly attributed to the Qur’an. In particular, the culture of literacy endowed the cult of Allah with a kind of authority-that of the unchangeable written word–that the delta’s preliterate forest cults had theretofore lacked. For, apart from those areas along the older river valleys where Hindu civilization had already made inroads among indigenous peoples, most of the eastern hinterland was populated by communities lightly touched, if touched at all, by Hindu civilization and its own ‘culture of literacy’. In the east, then, Islam came to be understood as a religion, not only of the axe and the plough, but also of the book.

Thus, although the Mughal government does not appear to have intended to Islamize the East Bengali countryside, such an outcome nonetheless resulted from its land policies. Seen from a global perspective, moreover, at the very time that the region became integrated politically with the Mughal Empire— that is, from 1574 — it was also becoming integrated economically with the whole world, since silver originally mined in South or Central America and shipped to Spain ultimately ended up fueling the eastward push of Bengal’s economic frontier. This occurred when silver imported to pay for Bengal’s textile exports was coined into Mughal currency and locally invested, as when Hindu financiers advanced capital to Muslim pioneers, who in turn organized local labour for cutting forested regions and founded mosques around which new agrarian communities coalesced. All of this fostered a kind of cultural authority that was in the first instance Mughal, but ultimately Islamic. Ironically enough, Europe’s early modern economic expansion in the ‘New World’ contributed to the growth of Islam in the ‘Old World,’ and especially in Bengal, which by the end of the seventeenth century had become one of the most dynamic economic zones in all Eurasia.

It is true, of course, that deltaic peoples had been transforming forested lands to rice fields long before the Mughal age. What was new from at least the sixteenth century on, however, was that this process had become particularly associated with Muslim holy men, or perhaps more accurately, with industrious and capable forest pioneers subsequently identified as holymen. In popular memory, some of these men swelled into vivid mythico-historical figures, saints whose lives served as metaphors for the expansion of both religion and agriculture. They have endured precisely because, in the collective folk memory, their careers captured and telescoped a complex historical socioreligious process whereby a land originally forested and non-Muslim became arable and predominantly Muslim. For this reason, one finds evidence of medieval Bengal’s socio-economic and religious transformations not only in Mughal revenue documents, but also in contemporary Bengali literature.

For example, the Candi-Mangala, composed around 1590 by the poet Mukundaram, celebrates the goddess Chandi and her human agent, the hunter Kalaketu. In this poem the goddess entrusts Kalaketu with temporal sovereignty over her forest kingdom on the condition that he, as king, renounce the violent career of hunting and bring peace on earth by promoting her cult. To this end Kalaketu is enjoined to oversee the clearing of the jungle and to establish there an ideal city whose population will cultivate the land and worship the king’s benefactor, Chandi. The poem can thus be seen as a grand epic dramatizing the process of civilization-building in the Bengal delta, and more concretely, the push of rice-cultivating civilization into virgin forest. It is true that the model of royal authority that informs Mukundaram’s Candi-Mangala is unambiguously Hindu. The king, Kalaketu, is both a devotee of the forest goddess Chandi and a raja in the classical Indian sense, while the peasant cultivators in the poem show their solidarity with the king by accepting betel nut from his mouth, an act drawing directly on the Hindu ritual of devotion performed for a deity, that is, puja. Yet the principal pioneers responsible for clearing the forest, the men who made it possible for both the city and its rice fields to flourish, were Muslims. The Great Hero (Kalaketu] is clearing the forest’, the poet proclaimed,

Hearing the news, outsiders came from various lands.

The hero then bought and distributed among them

Heavy knives (kath-da), axes (kuthar), battle-axes (tango), and pikes (ban).

From the North came the Das (people),

One hundred of them advanced.

They were struck with wonder on seeing the Hero, Who distributed betel-nut to each of them.

From the South came the harvesters,

Five hundred of them came under one organizer.

From the West came Zafar Mian,

Together with twenty-two thousand men.

Sulaimani beads in their hands,

They chanted the names of their pir and the Prophet.

Having cleared the forest,

They established markets.

Hundreds and hundreds of foreigners

Ate and entered the forest.

Hearing the sound of the axe,

The tiger became apprehensive and ran away, roaring.

Muslim pioneers in this poem are associated with three interrelated themes: (a) subduing a tiger, that is, taming Bengal’s untamed wilderness, (b) clearing the jungle, thus preparing the land for the cultivation of rice, and (c) establishing markets, that is, introducing commerce and a cash economy into a theretofore undeveloped hinterland. Moreover, these men are said to have come from the west, suggesting origins in upper India or beyond, in contrast to the aboriginals who came from the north and the harvesters who came from the south, that is, from within the delta. In point of numbers, the twenty-two thousand Muslims far surpassed the other pioneers, We also see that the Muslims were led by a single man, ‘Zafar Mian,’ evidently the chieftain or the organizer of the Muslim workmen. Finally, these men practiced a style of Islamic piety that focussed on chanting the name of a pir, who quite possibly was Zafar Man himself. Although the narrative cannot be understood as an eyewitness account, it probably had some basis in what was happening in Mukundaram’s own day. Even if there had been no historical ‘Zafar Mian’, the poet was clearly familiar with the theme of thousands of Muslims entering and transforming the forests under the leadership of capable chieftains or charismatic pirs.

The muslim pir Gazi on a painted scroll or ‘pata’ – circa -1800, Murshidabad. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Similar themes are seen in the legend of Shaikh Jalal al-Din Tabrizi, found in another sixteenth century text, the Sekasubhodaya. Although the events described in Mukundaram’s poem take place in a ‘time-out-of-time,’ those described in the Sekasubhodaya are set in the period just prior to the Turkish conquest; indeed, its author purports to have been the minister of Lakshmana Sena, the Hindu king defeated by the Turks in 1204. Both poems belong to a genre of pre-modern Bengali literature, the mangala-kavya, which typically glorified a particular deity and promised the deity’s followers bountiful auspiciousness in return for their devotion. But the hero of the Sekasubhodaya is not a traditional Bengali deity, but Shaikh Jalal al-Din Tabrizi, a figure said to have come from somewhere west of Bengal. He was instructed by Pradhan-purusa (‘Great Person,’ i.e., God) to go to ‘the eastern country,’ where he would meet Raja Lakshmana Sena, in whose kingdom he would build a ‘house of God’ (devasadana), or mosque. The shaikh did as he was told. Walking on the Ganges River with his magical shoes, Shaikh Tabrizi reached the Senas’ capital at Padua, and upon meeting Raja Lakshmana Sena he challenged the king to cause a nearby heron to release a fish caught in its bill. When Lakshmana Sena declined, the shaikh merely glanced at the bird, which at once dropped the fish.Seeing this, the astonished king asked for the shaikh’s grace (prasad) and vowed to remain his steadfast devotee.

Shaikh Tabrizi then set about building the mosque. After Lakshmana Sena donated some forest land for the purpose, the holyman prepared the site by clearing the area of demons and offering handfuls of holy water to Pradhanpurusa, to the Himalayas, and to various other personages. This done, Shaikh Tabrizi ‘invited people from the country and had them settled in that land’ Here we see a clear division of labour between the Hindu monarch and the Muslim holyman: the former donates forest land for the mosque while the latter performs the ritual feats necessary to establish the institution and invites local people to settle a formerly forested land. The shaikh issued formal documents of settlement to these men, who now cultivated the fields whose income would be used to support the mosque.

As with ‘Zafar Mian’ in Mukundaram’s poem, we should not hope to recover in this text the historical ‘Shaikh Tabrizi’. Rather, both men represent metaphors for changes experienced by people all over the delta, and in particular, the gradual cultural shift–well under way by the sixteenth century – from a Bengali Hindu world to a Bengali Muslim world. The Sekasubhodaya accomplished this by presenting the new in the guise of the familiar: Shaikh Tabrizi radiated a ‘glow of penance,’ or tapahprabhab, the power acquired through the practice of ascetic austerities; the ‘grace’ he gave to the king was prasad, the food a Hindu deity gives a devotee; the shaikh’s consecration of the mosque followed a ritual program consistent with that of a temple, and the shaikh’s patron deity, ‘Allah,’ was given the generic and hence portable name Pradhanpurusa, ‘Great Person’. Shorn of its fabulous embellishments, the text presents us with a model of patronage a mosque linked economically with the hinterland and politically with the state that was fundamental to the historical expansion of Muslim agrarian civilization throughout the delta. The Sekasubhodaya and the Candi-Mangala thus present us with literary versions of a process of socio-economic and cultural change that confirm the evidence of such change found in administrative documents of the period.

A more complex and self-consciously ‘Islamic’ work is Sayid Sultan’s great epic poem, the Nabi-Bamsa. Composed in the Chittagong region and also dating to the late sixteenth century, this ambitious work seeks to carve out a theological space for Islam amidst the various religious traditions already nested in the Bengal delta. For example, the work treats the major deities of the Hindu pantheon, including Brahma, Vishnu, Siva, Rama, and Krishna, as successive prophets of God, followed in turn by Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad. By commenting in this way on Vedic, Vaishnava, and Saiva divinities, in addition to biblical figures, the Nabi-Bamsa fostered the claim that Islam was the heir, not only to Judaism and Christianity, but also to the religious traditions of pre-Muslim Bengal. In this way, rather than repudiating those older religious traditions, Sayid Sultan’s epic served to connect Islam with Bengal’s socioreligious past, or at least with that part of it represented in the high textual tradition of the Brahmans.

But it would be wrong to characterize the work as merely ‘syncretic’; on fundamental points of theology, the poet clearly drew on Judeo-Islamic and not on Indic thought. For example, although the author freely interchanges the Arabic term nabi with the Sanskrit avatara, his meaning is not the Indic conception of repeated incarnations of the divine, but rather the Judeo-Islamic ‘once-only’ conception of prophethood. Similarly, the epic does not view cosmic time as oscillating between ages of splendour and ages of ruin in the cyclical manner characteristic of classical Indian thought. Rather, as religion in the time of each nabilavatara became corrupt, God sent down later prophets with a view to propagating belief in one god, culminating in the last and most perfect nabilavatara, Muhammad. Already in the four Vedas, the poet states, God (Kartar) had given witness to the certain coming of Muhammad’s prophetic mission.

It is in its characterizations of Adam and Abraham, however, that the epic poem’s agrarian dimension comes through most clearly. Adam, for his part, made his first earthly appearance on Sondwip Island, off Bengal’s southeastern coast. There the angel Gabriel instructed him to go to Arabia, where at Mecca he would construct the original Ka’ba. When this was accomplished, Gabriel gave Adam a plough, a yoke, two bulls, and seed, addressing him with the words, ‘Niranjan [God] has commanded that agriculture will be your destiny.’ Adam then planted the seeds, harvested the crop, ground the grain, and made the bread. Similar ideas are found in the poet’s treatment of Abraham, the supreme patriarch of Judeo-Christian-Islamic civilization. Born and raised in a forest, Abraham is said to have travelled to Palestine, where he attracted tribes from nearby lands, mobilized local labour to cut down the forest, and built a holy place, Jerusalem’s Temple, where prayers were offered to Niranjan. Clearly, the main themes of Abraham’s life as presented here his sylvan origins, his recruitment of nearby tribesmen, his leadership in clearing the forest, and his building a house of prayer–mirrored rather precisely the careers of the hundreds of pioneers who, during the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, had been given state land-grants for the purpose of mobilizing local clients in the Bengali countryside for just such activities.

Here, then, was a remarkable fit between social reality and religious thought. To be a good Muslim, so it was believed, one must cultivate the earth, as Adam did. Present-day Muslim, cultivators attach a similar significance to Adam’s career. Cultivators of Pabna District identify the earth’s soil, from which Adam was made, as the source of Adam’s power and of his ability to cultivate the earth. In their view, farming the earth successfully is the fundamental task of all mankind, not only because they themselves have also come from (i.e., were nurtured by the fruit of) the soil, but because it was God’s command to Adam that he reduce the earth to the plough. It was by farming the earth that Adam obeyed God, thereby articulating his identity as the first man and as the first Muslim. Hence all men descended from Adam, in this view, can most fully demonstrate their obedience to God- and indeed—their humanity by cultivating the earth. A 1913 village survey in Dhaka District noted that Muslims there ‘entirely fall upon agriculture as their only source of income, and unless driven to the last stage of starvation they never hire themselves for any kind of service, which is looked upon with contempt on their part. In 1908 the gazetteer for Khulna District noted that the Muslim masses ‘are descendants of semi-Hinduized aborigines, principally Chandals and Pods, and of low caste Hindus, who were converted to Islam …. [They] do not, however, know or admit that they are the descendants of converts to Islam; according to them they are the tillers of the soil, while the Ashraf do not cultivate the land with their own hands.’

The last phrase in this passage takes us back to the socio-religious cleavage referred to at the outset of this essay. I have argued that what defined ashraf identity was the cultivation of high Perso-Islamic civilization and a claimed descent from immigrants from west of Bengal. But this fails to go far enough. What served most profoundly to distinguish Bengali Muslim cultivators from ashraf classes, as the evidence cited above suggests, was the plough. Whereas farmers defined their Muslim identity around cultivating the soil, the ashraf disdained the plough and refused to touch it. A 1901 survey among Muslims of Nadia District found that ‘the Ashrafs will not adopt cultivation for their living. They consider cultivation to be a degraded occupation and they shun it for that reason.’ And in the Census for the same year H. H. Risley wrote that ‘like the higher Hindu castes, the Ashraf consider it degrading to accept menial service or to handle the plough. After all, the bulk of the Turks, Afghans, Iranians or Arabs who had migrated to India from the eleventh century onward no more saw themselves taking up agriculture than did English servants of the East India Company. Like the British, foreign-born Muslims saw themselves as having come to India to administer a vast empire whose wealth they could appropriate, and not to participate with Indians as fellow cultivators.

Over the past fifteen centuries, Islam has been continuously redefined, reinterpreted, and contested, as competing social groups have risen or fallen in prominence and influence. To the historian, the challenge is to identify those groups and, by situating them in their unique historical contexts, to determine how they constructed the religion in the particular way they did. From this perspective, it becomes unproductive, or simply wrong, to speak of one group’s understanding of Islam as orthodox’ and another’s as ‘unorthodox,’ or of one variant as ‘fundamentalist’ and another as ‘syncretic,’ or whatever. Such rhetorical labels may help in identifying and sorting out competing social classes in a given historical situation, or in determining who is on whose side in a particular debate. But as analytical tools they are quite useless.

In the same way, it would be wrong to view Islam as a monolithic essence that simply ‘expanded’ across space, time, and social class, in the process assimilating great numbers of people into a single framework of piety. In Bengal as elsewhere, Islam was continuously reinterpreted as different social classes in different periods became its dominant carriers, spokesmen, or representatives. Thus, in the thirteenth century, Islam had been associated with the ruling ethos of the delta’s Turkish conquerors, and in the cities, at least, such an association persisted for several centuries, sustained especially by Sufi shaikhs of the Chishti order. Later, the Mughal conquest permitted an influx of a new elite class of ashrāf Muslims immigrants from points west of the delta, or their descendants who were typically administrators, soldiers, mystics, scholars, or long-distance merchants. For them, a rich tradition of Persian art and literature served to mediate and inform Islamic piety, which most of them subordinated to the secular ethos of Mughal imperialism. In particular, the ashraf classes refused to engage in agricultural operations, and some Mughal officers even opposed the Islamization of native Bengalis who did. By the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, however, owing principally to phenomenal levels of agrarian and demographic expansion in East Bengal, the dominant carriers of Islamic civilization in the delta were no longer the urban ashrāf, but peasant cultivators of the eastern frontier, who in extraordinary ways had assimilated Islam to their agrarian worldview.

What made this possible was that in the Mughal period, Bengal’s agrarian and political frontiers had collapsed into one. From Sylhet through Chittagong, the government fused the political goal of deepening its authority among dependent clients rooted on the land with the economic goal of expanding the state’s arable land area. This was achieved by issuing grants, aiming at the agricultural development of the forested hinterland, most of whose recipients were petty mullās, pilgrims returned from Mecca, preachers, charismatic pirs, and local chieftains seeking tax-free land. These men oversaw, or undertook to oversee, the clearing of forests and the construction of mosques or shrines, which in turn became the nuclei for the diffusion of Islamic ideals along the agrarian frontier.

Above all, the local communities that fell under the economic and religious influence of these institutions do not appear to have perceived Islam as alien, or as a closed, exclusive system to be accepted or rejected as a whole. Although today one habitually thinks of world religions as self-contained and complete systems with well-defined borders, such a static or fixed understanding does not apply to Bengal’s premodern frontier, a fluid context in which Islamic superhuman agencies, typically identified with local superhuman agencies, gradually seeped into local cosmologies that were themselves dynamic. This ‘seepage occurred over such a long period of time that one can at no point identify a specific moment of ‘conversion,’ or any single moment when peoples saw themselves as having made a dramatic break with the past. Islam in Bengal absorbed so much local culture and became so profoundly identified with the delta’s long-term process of agrarian expansion, that the cultivating classes never seem to have regarded it as ‘foreign’ even though some Muslim and Hindu literati and foreign observers did, and still do.

In the context of premodern Bengal, then, it would seem inappropriate to speak of the ‘conversion’ of ‘Hindus’ to Islam. What one finds, rather, is an expanding agrarian civilization, whose cultural counterpart was the growth of the cult of Allah. This larger movement was composed of several interwoven processes: (a) the eastward movement and settlement of colonizers from points west, (b) the incorporation of frontier tribal peoples into the expanding agrarian civilization, and (c) the natural population growth that accompanied the diffusion or the intensification of wet rice agriculture and the production of surplus food grains. Because this growth process combined natural, political, economic, and cultural forces, we find in eastern Bengal a remarkable congruence between a socioeconomic system geared to the production of wet rice and a religious ideology that conferred special meaning on agrarian life. It is testimony to the vitality of Islam and one of the clues to its success as a world religion that its adherents in Bengal were so creative in accommodating local socio-cultural realities with the norms of the religion.

Dr. Richard M. Eaton is one of the leading historians of medieval and early modern India. His books have covered a wide range of subjects such as – slavery in South Asia, social histories of the Deccan, the social role of Sufis in the Sultanate of Bijapur, and several works on Islam in India, to name a few. He currently teaches at the Arizona State University in the Department of History.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply