The first half of the 1800s was a period marked by great turmoil and churn in India, especially in Bengal, and Calcutta, the centre of the East India Company’s empire. Enlightenment ideals from the ‘age of reason’ were flowing in from the West and spreading among the elite and middle classes, aided by printing presses that were churning out books, periodicals and newspapers at a rate hitherto unseen. Indians were either resisting these ideas outright or wondering how to contextualize them within their own lives and traditions. Some, like Raja Mohan Roy, were going back to the early roots of Indian heritage, to find a bridge between modernity and tradition in works like the Upanishads. This culminated in his campaigns against Sati and child marriage, among various reforms he championed, as well as his foundation of the ‘Brahmo Sabha’ (which went on to become the Brahmo Samaj), which led to further churn. Even those bhadralok (the elite upper and middle class) severely opposed to reform and enlightenment thinking, however, agreed that a Western education for their children would – from a utilitarian point of view (in terms of furthering career and business prospects) – be beneficial to them and their families. This led to a paradoxical situation where many members of Bengal’s wealthy elite – despite belligerently opposing any challenge to their traditions or customs – sponsored institutions of Western education where the seeds of such challenge would be born, and grown.

It would require a book to do full justice to the legacy Derozio – poet, journalist and, most importantly, educator – left behind in the course of his short life (little more than 22 years and eight months). Here, using some of his writing – three poems, a letter and what was probably his last article – we examine key aspects of his legacy.

First, a poem. Derozio’s ‘To India—My Native Land’, published in 1828, is considered one of the first modern Indian ‘nationalist’ poems. Written as a petrarchan sonnet, it is influenced by the Irish and English patriotic Romantic poets (such as Shelley, driven more by emotion and intuition, as opposed to the Enlightenment Poets, such as Pope, driven more by intellect and reason) read in Derozio’s time. Some commentators consider this to possibly be an early expression of the Indian nationalist sentiment that grew into our freedom struggle. However, it is important to note, as Mukherjee points out: “Derozio’s poetry is perhaps best described as patriotic and seen as a variant on Shelleyan idealism. His ideas did not contain any adumbration of anti-imperial subversion and, therefore, were somewhat different from the form that Indian nationalism acquired from the early 20th century.”

In the poem Derozio first evokes India’s past glory – “A beauteous halo circled round thy brow / and worshipped as a deity thou wast.” – then laments, feelingly, the state of the nation in his time:

“Thy eagle pinion is chained down at last,

And grovelling in the lowly dust art thou:

Thy minstrel hath no wreath to weave for thee

Save the sad story of thy misery!”

To understand the import of this poem it is important to understand where Derozio came from. Born in what is today Entally-Padmapukur in Kolkata, his mother and stepmother (who raised him) were English and his father was of mixed Portuguese and Indian descent. Mukherjee writes: “Derozio was by no means well-connected in Calcutta… His residence, located as it was in what E W Madge (an early Derozio biographer) called ‘the suburban side of Lower Circular Road,’ was clearly not a part of the White Town where the elite lived. Derozio was of Anglo–Portuguese descent, his grandfather being described in the St John’s baptismal register as a ‘Native Protestant.’ The Derozio family were seen as East Indians {an ethno-religious Indian Christian community who trace their roots to those who converted to Christianity in the 16th century when Portugal took over Bombay}*, and therefore as somewhat inferior to the white population… There is no evidence to suggest that Derozio was brought up in an ambience of any affluence; indeed, the fact that he had to seek employment as a mere adolescent suggests the contrary.”

Having been a gifted student of a school known as the ‘Drummond’s Academy’ or ‘Durrumotollah Academy’ in Calcutta, Derozio left at 14 to work for James Scott & Co, where his father was the chief accountant, which he left after two years to work in his uncle’s indigo factory at Bhagalpore. He joined the Hindu College, as a teacher, at the young age of 17. Mukherjee surmises that he got this job thanks to the recommendation of David Hare – Scottish watchmaker and philanthropist who founded many important educational institutions and had been appointed ‘Visitor’ to Hindu College, for which he had donated land – who was known for “his generosity in helping the underprivileged youth of Calcutta”. He also speculates that the Hindu College had accepted Derozio at such a young age, without prior teaching experience, because it was in “dire financial straits” at the time. “Unequal salaries, determined by colour of skin, were an accepted principle from the time of the college’s inception,” writes Mukherjee. “When it was established, its two secretaries, Irvine and Mookerjea, were paid monthly salaries of 300 and 100, respectively… It will not be entirely illogical to surmise that the same principle of difference operated on the teaching side as well… ”

There was also, of course, the fact that – as Ronsika Chaudhuri notes – Derozio’s academic excellence, and prizes he had won, had been noted in leading newspapers and periodicals of the time, such as the India Gazette and the Calcutta Journal. Also, he had begun to publish his poems in periodicals and journals prolifically by the time he was 16, and these had been well received.

To put it simply, therefore, the college had found a talented, young East Indian it could employ for less that it would cost them for a white teacher, at a time when the going was rough.

Mukherjee further notes an incident where the Headmaster of the Hindu College, D’Anseleme, raised his hand to slap Derozio “who avoided it by backing away” in the presence of Hare. This, coupled with his dismissal from the college after a few years of his joining, without even being given even the right to present his defence, gives you a sense of Derozio’s position in the prevailing hierarchy. Writes Mukherjee: “Given the status of East Indians in early colonial Calcutta, it is worth noting that the headmaster and the Hindu members of the managing committee could treat Derozio in the way they did because of his social standing, or rather the absence of it. It goes without saying that no European could have been dismissed without a hearing or have faced the threat of being slapped in a professional space.”

Derozio would use the pseudonym ‘An East Indian’ for some of his poems as well as, possibly, letters in the correspondence columns of the India Gazette. The East Indian was also the name of the paper he ran after being dismissed from the Hindu College. This Eurasian group was, at the time, accepted neither by the British, nor the Hindu and Muslim societies. All of this is important to reiterate the fact that Derozio was not himself a member of any category of ‘Calcutta elite’. Hence, when he wrote the words “And grovelling in the lowly dust art thou:” to describe the state of the nation, they came not from the pen of an entitled person fashioning a romantic turn of phrase, but was born, possibly, out of personal experience.

Also, as a person existing in between the worlds that influenced Indian discourse in those days – the worlds of the Britishers and Europeans, the Hindus and the Muslims – Derozio was perhaps best placed, with a bird’s eye view, to propel this discourse forward with the spirit of freethinking. Take the last lines of the poem:

“And bring from out the ages, that have rolled

A few small fragments of these wrecks sublime,

Which human eye may never more behold;

And let the guerdon of my labour be

My fallen country! One kind wish from thee!”

Some commentators choose to see Derozio as a revolutionary only, urging all to break every tie with the past. But this poem as well his some of his other writings suggest otherwise: that what he was in fact encouraging was a free and dispassionate review of history, with an eye on the future, to retract what can be useful from within it, and then bring about change with an inspiring mix of the old and new (while recognizing, full well, what is past and must be discarded), as well as the consent of a people who were ‘educated’ in the truest sense of the word.

Mukherjee writes: “When, in a short piece, he had to remember great names and their influence, he recalled Bacon, John Milton, John Locke, Stewart, Shelley and Isaac Newton… Here is clear evidence of his Enlightenment intellectual lineage… This strong influence of the Enlightenment notwithstanding, or maybe because of it, Derozio was not an unequivocal supporter of the abolition of sati. Before its abolition, he wrote, ‘It will be impossible therefore to make an attempt at overthrowing this system [sati], before education is generalized, without wounding the tenderest feelings of human nature… How… can we stand acquitted from the charge of intolerance, if we exercise our power in violently suppressing so popularly respected a ceremony among the Hindoos? Neither is society injured by the practice, nor will the poor native females be the better for its abolition.’ The influence of the Enlightenment informed what he thought was his duty as a teacher.” And so, alongside Derozio the patriot, enlightenment advocate, and freethinker, we have, possibly, Derozio the wary democrat.

Now that we have an idea of Derozio the person, let us examine his impact as an educator and creator of a ‘public sphere’, without which his legacy might not have persisted till this day. We will do this through two of his writings: the letter he wrote upon his dismissal from the Hindu College and what was possibly the last article he wrote before his premature death at the age of 22.

While Mukherjee has addressed the events leading up to Derozio’s dismissal, as well as the socio-political forces behind it in his essay, you will find a linear record of the primary documentation connected with events here.

Mukherjee draws from the limited material available to sum up Derozio’s characteristics as a teacher:

“First, Derozio emphasised that students should think for themselves: this was their ‘sacred duty.’

“Second, there should be a free exchange of ideas and everyone should express clearly what they felt.

“Third, he encouraged students to read books that they would not have read as part of the curriculum. He often read aloud to them.

“Fourth, he impressed upon his students the importance of truth and virtue.

“Finally, he encouraged students to meet him outside the classroom and the college and to speak frankly to him… His age, no doubt, helped in such interactions {Derozio was only a few years older than his students}*. What Derozio was attempting to do was nothing more and nothing less than what good teachers and pedagogues invariably do, namely, encourage reading and critical thinking to open up the minds of their students.”

The opening lines from Derozio’s own poem (reproduced in full below), written for his students, read:

“Expanding, like the petals of young flowers,

I watch the opening of your infant minds,

And the loosening of the spell that binds

Your intellectual energies and powers”

The spell was loosened. His adolescent students, mostly from upper caste Hindu families, had grown up in traditional hierarchies bound tightly by religion and caste that they now began to question, defy and untangle. Mukherjee lists primary sources which indicate the stir the Derozians (as his students came to be known) were causing. A letter by Radhakanta Deb, who was key in establishing the Hindu College and played an influential role in its management, and who, writes Mukherjee, “for all his philanthropic zeal was a diehard conservative”, reads:

“It has been reported to me from time to time, and also published in the Bengalee papers, that the conduct of some of the adult students of the College is in the highest degree disorderly and irregular, and in various modes inconsistent with the Laws and usages of our caste; that in direct contradiction to its dictates, they eat and drink prohibited articles… with Mahomedans and Christians.”

The Oriental Magazine put it more colourfully, describing the “progress” the Derozians were “making by actually cutting their way through ham and beef and wading to liberalism through tumblers of beer”.

To sum up what followed in a line, articles, Hindu College notices and meetings between the members of college management ensued. Derozio was dismissed.

If you ask Calcuttans today you will find that many popular recollections of Derozio’s life as a teacher stop here. Here was a teacher, such recollections seem to say, who taught his students the tenets of the enlightenment. They began to eat ham and beef, drink alcohol and mix freely with those from other castes and religions and then he was dismissed. This would be a reductivisation of the accomplishments of not just Derozio but also the Derozians.

To deal with the first, let’s examine the contents of the letter he wrote to Horace Hayman Wilson (ex officio member and vice president of the college’s managing committee) after his dismissal. He addressed three charges brought against him:

– Did he believe in God?

– Did he think respect and obedience to parents no part of moral duty?

– Did he think the intermarriage of brothers and sisters to be innocent and allowable?

On the second and third questions, Derozio rejects the suggestions that he was encouraging students to disrespect and disobey their parents, or advocating marriage between brothers and sisters, as blatantly false, and here we have a historical record of the phenomena that has come to be notorious today as ‘fake news’. Derozio insists that while he has “condemned that feigned respect which some children evince, being hypocritical and injurious to the moral character” he has “always insisted upon respect and obedience to parents” and provides instances to back up his claim. Similarly, he refuses believing in, or advocating, the “intermarriage of brothers and sisters” and here he writes: “I am aware that for some weeks some busy bodies have been manufacturing the most absurd and groundless stories about me, and even about my family. Some fools went so far as to say that my sister, while others said my daughter (though I have not one) was to have been married to a Hindoo young man!!! I traced the report to a person named Brindabun Ghoshal, a poor Brahmin, who lives by going from house to house to entertain the inmates with the news of the day, which he invariably invents.”

But Derozio’s most interesting response by far, is the one to the first question, on his belief in God, which he doesn’t answer, indicating its irrelevance to the larger issue of an educator’s duty. Instead he traces the instance of the question to his acquainting the students with “Hume’s celebrated dialogue between Cleanthes and Philo, in which the most subtle and refined arguments against Theism are adduced”. Also, he uses the question as a pretext to lay out elements of enlightened enquiry.

For one, the admission of ignorance. “I am too thoroughly imbued with the deep sense of human ignorance and of the perpetual vicissitudes of opinion,” writes Derozio. “To speak with confidence even of the most unimportant matters. Doubt and uncertainty besiege us too closely, to admit the boldness of dogmatism to enter an enquiring mind, and far be it from me to say ‘that is’ and ‘that is not’, when after the most extensive acquaintance with the researches of science, and after the most daring flight of genius, we must confess with sorrow and disappointment that humility becomes the highest wisdom—for the highest wisdom assures man of his ignorance.”

For another, the importance of doubt. Derozio quotes Bacon (a leading figure in the fields of natural philosophy and scientific methodology, called the father of empiricism by some, and whom Derozio had cited as a major influence) here: “If a man will begin with certainties, he shall end in doubt.” He further emphasizes what ‘beginning with certainties’ will lead to: a “contended ignorance”, which when “roused too late to thought” will have the consequence of “universal skepticism” (skepticism for its own sake, with no beliefs to build on or live by).

Third. The need for argument. “Is it consistent,” Derozio asks. “With an enlightened notion of truth to wed ourselves to only one view of so important a subject, resolving to close our eyes and ears against all impressions that oppose themselves to it?” He also writes: “How is any opinion to be strengthened but by completely comprehending the objections that are offered to it and exposing their futility? And what have I done more than this? Entrusted as I was for some time with the education of youth, peculiarly circumstanced, was it for me to have made them pert and ignorant dogmatists by permitting them to know what could be said upon only one side of the grave questions?”

After this, placing such principles in the context of his duty at the Hindu College, Derozio goes on to say: “Setting aside the narrowness of mind which such a course might have evinced, it would have been injurious to the mental energies and acquirements of the young men themselves.”

All of this brings us to Derozio’s real achievement beyond “what good teachers and pedagogues invariably do”, which Chaudhuri highlights in her paper ‘The Politics of Naming: Derozio in Two Formative Moments of Literary and Political Discourse, Calcutta 1825-1831’: his contribution towards the creation of a public sphere (a space for individuals of a society to come together to identify and discuss societal ills and through these discussions influence action and possibly change).

Derozio encouraged his students to form, in 1828, a debating society called the Academic Association. Subjects debated, as listed by Nitish Sengupta, included, “Free will, free ordination, fate, faith, the sacredness of truth, the high duty of cultivating virtue, and the meanness of vice, the nobility of patriotism, the attributes of God, and the arguments for and against the existence of the deity… the hollowness of idolatry and the shames of priesthood.”

The Academic Association was significant for two reasons: for one, it opened up the field of debate beyond Hindu College and its students as others too would attend and report and write on what was argued (audience members included prominent members of society and academia like David Hare, Col. Benson, the Governor General’s private secretary, and Dr. Mills, the principal of Bishop’s College); and, secondly, it transformed Derozians like Rasik Krishna Mallick, Krishna Mohan Banerjee, Ramgopal Ghosh, Radhanath Sikdar, Dakshinaranjan Mukherjee and Hara Chandra Ghosh into brilliant public speakers. It could be said that the Academic Association was instrumental in his students’ journey from being ‘Derozians’ to becoming what they were to be better known as: ‘Young Bengal’. After Derozio, the president of the association, died in 1831, David Hare took over and the body survived till the late 1830s.

Another way in which Derozio committed himself towards the building of a public sphere was through journalism. A contributor to various publications himself, after his dismissal from Hindu College, Derozio went on to launch the newspaper The East Indian. What is probably the last article he wrote is reproduced below. He is pleased to note about his alma mater: “The most pleasing feature… is its freedom from illiberality… At some of the schools in Calcutta objections are made to native youth, not so much on the part of the masters as of the Christian parents who have children at those schools. At the Durrumtollah Academy however, there is none of this illiberal feeling; and it is quite delightful to witness the exertions of Hindoo and Christian youth, striving together in the same classes for academical honors.”

He uses a couplet to emphasise this feeling:

When man to man the world o’er,

Shall brothers be and a’ that

These lines are pertinent because they were written at a time when the walls between communities were even more rigid than they are today and syncretic spaces for education, work and social mixing were often criticized and censured. Also, because Derozio’s paper was for a largely Christian readership, which he wasn’t hesitant to criticize.

But Derozio’s real contribution to journalism was through his students. Souraprovo Chatterjee has examined this in a paper titled ‘Journalistic Contributions of Derozio and His Disciples: A Critical Exploration’ that traces these contributions from The Parthenon, a Hindu College publication begun when Derozio was alive, and with his support, to the numerous publications the Derozians used to channel their ideas into society after his death.

But before considering the Derozians let us examine lines from the last item we have republished below, a poem by Derozio named, simply, Death.

The poem begins with an equanimous approach to “Death! my best friend”, before turning into something more:

“But man’s eternal energies can make

An atmosphere around him, and so take

Good out of evil, like the yellow bee

That sucks from flowers malignant, a sweet treasure—

O tyrant Fate! thus shall I vanquish thee,

For out of suffering shall I gather pleasure.”

It is worth contemplating whether these last lines are indicative of the fact that Derozio was very much aware of what he was doing, that he knew that the “atmosphere” his “eternal energies” would “make” “around him” would, indeed be what would lead him to “vanquish” the “tyrant Fate”.

To understand the above better, let’s examine what this “atmosphere” comprised. The Derozians, or ‘Young Bengal’ were what kept Derozio’s legacy alive and kicking well after his death at the age of 22. Their impact needs to be examined collectively, as well as individually.

But before doing so it is important to note, broadly, the chief criticisms levelled against ‘Young Bengal’. The first, obviously, was that they were too radical. The second, that they were too elite— that the concerns of these men, mostly from wealthy, ‘upper caste’ families, did not match those of the masses, and that the conveyance of their ideas to a larger public was limited. The third allegation, directed from a communal angle, was that ‘Young Bengal’ was either motivated by or unwitting accomplices to furthering the British imperialistic and/or Christian missionary agenda, as the toasting of enlightenment ideals and questioning, defiance and, in some cases, ridicule and condemnation of traditional Hindu norms and practices amounted to an indirect endorsement of British rule as well as an attack on Indian and Hindu morale.

This third allegation found support, at the time, with the conversion of a few Derozians into Christianity, particularly Krishna Mohan Banerjee who was the first president of the Bengal Christian Association. Also, with the simultaneous presence, during this period, of Alexander Duff – a Christian missionary who played a significant role in the development of higher education – and who was instrumental in the conversion of Lal Behari Dey, educator, evangelist and reputed journalist and author.

But consider Derozians like Ramgopal Ghosh, and his speeches and writings in support on the British ‘Black Acts’ – four draft acts that sought to bring the judicial treatment of Indians on par with Europeans, which the Europeans had vociferously opposed – for which he had to lose his position as Vice President of the Agri-Horticultural Society. He was also one of the first, if not the first, to demand the eligibility of Indians in the Indian Civil Service examinations. Or consider another Derozian, Dakshinaranjan Mukherjee, whose essay, Present Conditions of the East India Company’s Courts of Judicature and Police under the Bengal Presidency was called “seditious” and “treasonable” for its calling out of the abuses of the British government. Or Rasik Krishna Mallick, who – according to Sengupta – “criticised police corruption, attributed the lack of protection of the peasantry to the Permanent Settlement {an oppressive agreement between the East India Company and Bengali zamindars to fix land revenue to be raised}*, and advocated the abolition of the political power of the merchant {East India}* company.” Mallick may have shocked society in his time by refusing to take a court oath by touching a copper vessel containing water from the river Ganga (“I do not believe in the sacredness of the Ganges,” he is reported to have said) but he was also an unrelenting advocate for the use of the mother tongue as a medium of education. According to Samaren Roy, when the cry for Derozio’s dismissal from the Hindu College arose, some orthodox Christians were as intent on it as orthodox Hindus were.

These as well as other such examples demolish the simplistic narrative of the Derozians being mere British or Christian ‘agents’. On the contrary, one discovers, on closer examination, that the Derozians were actually using the same principles of enlightenment that the British championed against the British themselves, a strategy that was later to become the hallmark of the Indian National Congress. It is of interest, for instance, that Surendranath Banerjee, one of the early leaders and founding members of the Congress, said of the Derozians that they were “the pioneers of the modern civilization of Bengal, the conscript fathers of our race whose virtue will excite veneration and whose failings will be treated with gentlest consideration.”

The criticism that the Derozians, with a few exceptions, came from elite Bengali families holds true. Also true, is the fact that their economics was classical liberal. Here is a descriptor from Andrew Sartori’s book Bengal in Global Concept History: Culturalism in the Age of Capital: “With respect to the questions relating to Political Economy, they all belong to the school of Adam Smith. They are clearly of opinion that the system of monopoly, the restraints upon trade, and the international laws of many countries, do nothing by paralyse the efforts of industry, impede the progress of agriculture and manufacture, and prevent commerce from flowing in its natural course.”

And yet one of the major crusades certain members of the Young Bengal fought was for the cause of the have-nots. Take Derozian Peary Chand Mitra’s fiery essay The Zamindar and the Ryots in support of ryot (peasant or tenant farmer) rights (a cause to which Mitra as well as some other Derozians like Mallick were fiercely devoted). “The idea of property, as being the product of labour, is natural with man,” Mitra writes. “Land unreclaimed from sterility is common property. It is the first tillage and cultivation which constitute private property.” Sartori cites this to examine further how Mitra rails against Zamindars who are absent and “alien to the internal economy of their zemindaries” and who compound “exorbitant rents with illegal cess taxes, complemented by a class of money lenders preying on the hand-to-mouth existence of the cultivators.”

When it comes to making their ideas available to a larger public, we have the instance of Peary Chand Mitra’s popularization of a simple, spoken Bengali prose style with his novel Alaler Gharer Dulal. He employed Cholitobhasha (colloquial Bengali) and the style of prose he introduced came to be known as ‘Alali’, after the novel’s title. Mitra took this idea further to journalism, by collaborating with fellow Derozian Radhanath Sikdar to begin Masik Patrika, a magazine using simple Bengali prose everyone could understand.

Also, over and above their contribution to the sciences, journalism, literature, reform and the law, the Derozians were seriously committed to women’s education. Haramohan Chattopadhyay, a Hindu College clerk at the time, said of the Academic Association debates: “The degraded state of Hindus formed the topic of many debates; their ignorance and superstition were declared to be the cause of such a state, and it was then resolved that nothing but a liberal education could enfranchise the mind of the people. The degradation of the female mind was viewed with indignation; the question at a very large meeting was carried unanimously that Hindu women should be taught.”

Mitra and Sikdar’s Masik Patrika was targeted at women readers of the time, and its content often revolved around women’s empowerment. Derozians Hara Chandra Ghosh and Ramgopal Ghosh provided much needed help to John Elliot Drinkwater Bethune in establishing what is one of Asia’s first educational institutions for women, in Kolkata. Another Derozian, Dakshinaranjan Mukherjee, provided land for the project. Derozian Sib Chandra Deb opened a girl’s school in his own home which he later shifted to another building.

Overall, Sartori sums up, ‘Young Bengal’ stood for:

– “More representational government

– “More native appointments in the government services

– “A more equitable, more efficient and less corrupt administration of justice

– “An end to the conflation of governmental and commercial functions in Company rule

– “The promotion of education throughout Hindu society (including among its women)

– “The universal protection of rights and promotion of general social utility.”

The accusation that the Derozians were radical holds true for its time. From the point of view of the Hindu society as well as the British. Sartori writes: “Young Bengal assumed the position of a loyal opposition too sharp in its criticism for the comfort even of many self-declared Whigs {a British political faction, built on liberal ideals, that stood in opposition to the Tories in early 19th Century Britain}*.” But then, Young Bengal wore its radicalism proudly, as a badge of identity almost, striking out in every direction. “The Young Bengal movement,” N S Bose writes. “Was like a mighty storm that tried to sweep away everything before it. It was a storm that lashed society with violence causing some good, and perhaps naturally, some discomfort and distress.”

The list of accomplishments of individual Derozians is too long and their lives too colourful to record here in entirety. To get a sense, beyond what has been mentioned already (Many of the following is available thanks to Shibnath Shastri’s book Ramtanu Lahiri O Tatkalin Banga Samaj):

Krishna Mohan Banerjee, educationist and litterateur, author of plays and books on Indian and Christian philosophy, started the publication The Inquirer to address social evils.

Sib Chandra Deb joined the British survey department and then the general administration to become a Deputy Collector as well as a prominent leader of the Brahmo Samaj and then the Sadharan Brahmo Samaj (his decision to conduct his son’s marriage without Brahmin priests and the sacred fire led to public protests in Calcutta, with violence threatened against the groom, but he stood firm).

Hara Chandra Ghosh became the first Bengali to become a judge of the Calcutta Small Causes Court. His contribution to the judicial service is still spoken of.

Ramgopal Ghosh, went from being a small shopkeeper’s son to a successful businessman, reformer and orator (he was called the “Indian Demosthenes” and when he father asked him to declare, publicly, his faith in the Hindu religion, as it was practised he said “I am ever willing to obey you and bear any pains for that but I cannot tell a lie.”).

Ramtanu Lahiri was a teacher and social reformer whose biography by Shibnath Shastri Ramtanu Lahiri O Tatkalin Banga Samaj is a great resource for studying the Young Bengal movement as a whole. His decision to discard his sacred thread or poita when he was living and working in Bardhaman created an uproar.

Rasik Krishna Mallick was a journalist, reformer and educationist who was editor of the bilingual periodical Jnanveshan and the Bengali monthly newspaper Jana Sindhu Taranga and set up a free school in Sumilia. As a Deputy Collector he had a great reputation for honesty.

Peary Chand Mitra was a literary institution of sorts whose Alaler Gharer Dulal, about the society of a bohemian in early 19th century Calcutta, is often cited as the first Bengali novel. Other literary works include Modh Khaoya Bada Day Jat Thakar ki Upay, Ramaravjika, Krsipath, and Bamatoshini, as well as books in English. Reverend James Long called him the ‘Dickens of Bengal’. As a journalist he contributed to English and Bengali newspapers and periodicals and co-ran Jnanveshan with Mallick and Masik Patrika with Sikdar. He began his career as a deputy librarian at Calcutta Central Library and went on to become its Secretary. An entrepreneur in his later life, he was a partner or director in concerns like the Great Eastern Hotel Company Ltd., Port Canning Grand Investment Co., and Howrah Docking Co.

Dakshinaranjan Mukherjee was publisher of the Jnanvesan as well as, in his later life, the Lucknow Times, Samachar Hindustani and Bharat Patrika from Lucknow. An orator and contributor to various publications, he was a practising lawyer and the first Indian to be appointed as Collector of the Calcutta Municipality. He also worked as Deputy Collector of the Maharaja of Bardhaman and eloped with the Maharaja’s widow (his 8th wife), which caused a scandal. Mukherjee and his wife, who had married by registration, spent the rest of their lives in Lucknow, where Mukherjee established the Canning College. While his essay, Present Conditions of the East India Company’s Courts of Judicature and Police under the Bengal Presidency had kicked up a storm for exposing the abuses of the British government, in his later life Mukherjee helped the British during the sepoy mutiny and was rewarded with the Shankarpur Taluk, an honorary assistant commissionership of Lucknow and Awadh and eventually the title of ‘Raja’. After this, however, he campaigned for the formation of a provincial government with an equal number of nominated and elected legislators, under the banner of the Awadh British Indian Association, which he had founded, causing him to lose favour with the British.

Radhanath Sikdar, a brilliant mathematician, joined the Great Trigonometric Survey as a computer, invented his own geodetic processes and introduced innovations which were to become standard procedure (such as the formula for the conversion of barometric readings taken at different temperatures). Measuring the snow capped peaks near Darjeeling, he calculated the height of Mount Everest, concluding that it was the tallest peak in the world. The norm followed by Surveyor General George Everest himself was that the local name would be preferred while naming a peak. If this was subscribed to by his successor Col. Andrew Scott Waugh Sikdar’s name might have been assigned to the peak today. But Waugh decided to name the peak after Everest instead. Sikdar also wrote large sections of the Survey Manual which proved to be an invaluable guide to future surveyors.

A body the Derozians established after, or in the last years of, the Academic Association was ‘The Society for the Acquisition of General Knowledge’ which published papers such as: Nature of Historical Studies and Civil and Social Reform, Interests of the Female Sex and The State of Hindustan. This and other organisations founded by Young Bengal became forerunners for later influential societies like the Landholder’s Society, British India Society and the British Indian Association, which the Derozians were also a part of.

But more than such formal societies, the informal links between the Derozians are worth considering. When financial needs arose, for instance, they seem to have stood steadfastly by one another. When Krishna Mohan Banerjee was thrown out of his house for converting to Christianity it was fellow Derozian Dakshinaranjan Mukherjee who provided him support as well as protection. Ramgopal Ghosh helped out Rasik Krishna Mallick and Ramtanu Lahiri when they were in need. Then there were the professional collaborations: Peary Chand Mitra running different publications with Radhanath Sikdar and Rasik Krishna Mallick and Dakshinaranjan Mukherjee is just one example.

The Derozians were a network, but what distinguished them from any other old boy’s club was their commitment to change, built on shared ideas that they had been introduced to, together, as teenagers. They learnt to adapt and implement these ideas, individually and collectively, in the Indian context, and grow with them. They stood at the cusp or beginning of a period which some historians would later call the ‘Bengal’ or ‘Indian’ ‘Renaissance’. Some historians disagree vigorously with this phrase and interpretation. But whether or not you call them ‘Renaissance men’, there is no doubting they were a phenomenon of the mid-1800s.

The funniest thing is Derozio had mythologised what Young Bengal was to become, in poetry, long before any of this came to be. Note the last lines of his sonnet addressed to the students of Hindu College:

“…O! how the winds

Of circumstances, and gentle April showers

Of early knowledge, and unnumbered kinds

Of new perceptions shed their influence:

And how you worship truth’s omnipotence!

What gladness rains upon me, when I see

Fame, in the mirror of futurity,

Weaving the chaplets you are doomed to gain,

And then I feel I have not lived in vain.”

* Braces – {} – have been used within quotes wherever an explanation has been added by us.

It was in this milieu of turmoil and churn that the figure of Henry Louis Vivian Derozio emerged. The Hindu College (later renamed the Presidency College), where he taught, was such an institution. As Rudrangshu Mukherjee puts it, in his essay titled ‘The Derozio Affair: An Annal of Early Calcutta’, such elite members of Bengali society as referred to above “wanted Western learning for their sons and wards but not the critical thinking abilities that came with that tradition of learning. For the fathers and the Hindu members of the managing committee {of Hindu College}*, Western education was functional and instrumental—a means to an end—the end being government jobs in the lower rungs of the growing colonial administration. Derozio’s interest was not in reducing education to a glorified variety of language teaching. His vision was more profound and was drawn from the Latin root of the word educate (educere, meaning to lead forth).”

My country! in thy days of glory past

A beauteous halo circled round thy brow

and worshipped as a deity thou wast.

Where is thy glory, where that reverence now?

Thy eagle pinion is chained down at last,

And grovelling in the lowly dust art thou:

Thy minstrel hath no wreath to weave for thee

Save the sad story of thy misery!

Well—let me dive into the depths of time,

And bring from out the ages, that have rolled

A few small fragments of these wrecks sublime,

Which human eye may never more behold;

And let the guerdon of my labour be

My fallen country! One kind wish for thee!

Henry Louis Vivian Derozio

Dear Sir,

Your letter which I received last evening should have been answered earlier, but for the interference of other matters which required my attention, I beg your acceptance of this apology for the delay, and thank you for the interest which your most excellent communication proves that you continue to take in me. I am sorry, however, that the question you have put to me will impose upon you the disagreeable necessity of reading this long justification of my conduct and opinions. But I must congratulate myself that this opportunity is afforded me of addressing so influential and distinguished an individual as yourself upon matters which if true might seriously affect my character. My friends need not however be under any apprehension for me; for myself the consciousness of right is my safeguard and my consolation.

(1) I have never denied the existence of God in hearing of any human being. If it be wrong to speak at all upon such a subject I am guilty; for I am neither afraid nor ashamed to confess having stated the doubts of philosophers upon his head, because I have also stated the solution of those doubts. Is it forbidden anywhere to argue upon such a question? If so, it must be equally wrong to adduce an argument upon either side, or is it consistent with an enlightened notion of truth to wed ourselves to only one view of so important a subject, resolving to close our eyes and ears against all impressions that oppose themselves to it?

How is any opinion to be strengthened but by completely comprehending the objections that are offered to it and exposing their futility? …Entrusted as I was for sometime with the education of youth, peculiarly circumstanced, was it for me to have made them pert and ignorant dogmatists by permitting them to know what could be said upon only one side of the grave questions?

How is any opinion to be strengthened but by completely comprehending the objections that are offered to it and exposing their futility? And what have I done more than this? Entrusted as I was for sometime with the education of youth, peculiarly circumstanced, was it for me to have made them pert and ignorant dogmatists by permitting them to know what could be said upon only one side of the grave questions? Setting aside the narrowness of mind which such a course might have evinced, it would have been injurious to the mental energies and acquirements of the young men themselves. And (whatever may be said to the contrary) I can indicate my procedure by quoting no less orthodox authority than Lord Bacon. “If a man” says this philosopher (and no one had a better right to pronounce an opinion upon such matters than Lord Bacon) “will begin with certainties, he shall end in doubt”. This I need scarcely observe is always the case with contented ignorance, when it is roused too late to thought, one doubt suggests another and universal skepticism is the consequence. I therefore thought it my duty to acquaint several of the college students with the substance of Hume’s celebrated dialogue between Cleanthes and Philo, in which the most subtle and refined arguments against Theism are adduced. But I have also furnished them with Dr. Reids and Dugald Stewart’s more acute replies to Hume, replies which to this day continue unrefuted. This is the head and front of my offending. If the religious opinions of the students have become unhinged in consequence of the course I have pursued, the fault is not mine. To produce conviction was not within my power, and if I am condemned for the Atheism of some, let me receive credit for the Theism of others. Believe me my dear Sir, I am too thoroughly imbued with the deep sense of human ignorance and of the perpetual vicissitudes of opinion to speak with confidence even of the most unimportant matters. Doubt and uncertainty besiege us too closely, to admit the boldness of dogmatism to enter an enquiring mind, and far be it from me to say “that is” and “that is not”, when after the most extensive acquaintance with the researches of science, and after the most daring flight of genius, we must confess with sorrow and disappointment that humility becomes the highest wisdom—for the highest wisdom assures man of his ignorance.

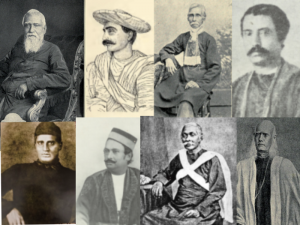

The ‘Derozians’ or ‘Young Bengal’. First Row (L to R): Ramtanu Lahiri, Tarachand Chakraborti, Sib Chandra Deb, Ramgopal ghosh. Second Row (L to R): Radhanath Sikdar, Dakshinaranjan Mukherjee, Peary Chand Mitra, Krishna Mohan Banerjee

Doubt and uncertainty besiege us too closely, to admit the boldness of dogmatism to enter an enquiring mind, and far be it from me to say “that is” and “that is not”, when after the most extensive acquaintance with the researches of science, and after the most daring flight of genius, we must confess with sorrow and disappointment that humility becomes the highest wisdom—for the highest wisdom assures man of his ignorance.

(2) Your next question is “Do you think respect and obedience to parents no part of moral duty?” For the first time in my life did I learn from your letter that I am charged with having inculcated so hideous, so unnatural, so abdominal a principle. The authors of such infamous fabrications are too degraded even for my contempt. Had my father been alive, he would have repelled the slander, by telling my calumniators that a son who had endeavoured to discharge every filial duty as I have done could never have entertained such a sentiment. But my mother can testify how utterly inconsistent it is with my conduct, and upon her testimony I might rest my vindication. However, I will not stop short there. So far from having even maintained or taught such opinion, I have always insisted upon respect and obedience to parents. I have indeed condemned that feigned respect which some children evince, being hypocritical and injurious to the moral character. But I have always endeavoured to cherish the genuine feelings of the heart, and to direct them into proper channels. Instances, however, in which I have insisted upon respect and obedience to parents, are not wanting. I shall quote two important ones for your satisfaction, and as the parties are always at hand, you may at any time substantiate what I say. About two or three years ago, Dukhinaranjan Mookerjya (who has made so great a noise lately) informed me that his father’s treatment of him had become utterly unsupportable, and that his only chance of escaping it was by leaving his father’s house. Although I was aware of the truth of what he had said, I dissuaded him from taking such a course, letting him know that much should be endured from a parent, and that the world would not justify his conduct, if he left his home without being actually turned out of it. He took my advice, though I regret to say, only for a short time. A few weeks ago he left his father’s house, and to my great surprise, engaged another in my neighbourhood. After he had completed his arrangements with his landlord, he informed me for the first time of what he had done, and when I asked him why he had not consulted me before he took such a step: “because,” replied he, “I knew you would have prevented it” The other instance relates to Mohes Chunder Singh. Having recently behaved rudely to his father, and offended some relatives, he called upon me at my house, with his uncle, Umacharan Bose, and his cousin, Nundolall Singh. I reproached him severely for his contumacious behaviour, and told him until he sought forgiveness from his father, I would not speak to him. I might mention other cases, but these may suffice.

I have always insisted upon respect and obedience to parents. I have indeed condemned that feigned respect which some children evince, being hypocritical and injurious to the moral character. But I have always endeavoured to cherish the genuine feelings of the heart, and to direct them into proper channels.

(3) “Do you think marriages of brothers and sisters innocent and allowable?” This is your third question. “No”, is my distinct reply, and I never taught such an absurdity. But I am at a loss to find out how such misrepresentations as those to which I have been exposed, have become current. No person who has ever heard me speak upon such subjects could have circulated these untruths; at least I can hardly bring myself to think that one of the College students with whom I have been connected could be either such a fool as to mistake every thing I ever said, or such a knave as willfully to mistake my opinions. I am rather disposed to believe that weak people who are determined upon being alarmed, and finding nothing to be frightened at have imputed these follies to me. That I should be called a sceptic and an infidel is not surprising, as these names are always given to persons who think for themselves in religion; but I assure you that the imputations which you say are alleged against me, I have learned for the first time from your letter, never having dreamed that sentiments so opposed to my own, could have been ascribed to me. I must trust, therefore, to your generosity to give the most qualified contradiction to these ridiculous stories. I am not a greater monster than most people; though I certainly should not know myself, were I to credit all that is said of me. I am aware that for some weeks some busy bodies have been manufacturing the most absurd and groundless stories about me, and even about my family. Some fools went so far as to say that my sister, while others said my daughter (though I have not one) was to have been married to a Hindoo young man!!! I traced the report to a person named Brindabun Ghoshal, a poor Brahmin, who lives by going from house to house to entertain the inmates with the news of the day, which he invariably invents. However, it is a satisfaction to reflect, that scandal, though often noisy, is not everlasting. Now that I have replied to your questions, allow me to ask you, my dear Sir, whether the expediency of yielding to popular clamour can be offered in justification of die measures adopted by the Native Managers of the College towards me? Their proceedings certainly do not record any condemnation of me, but does it not look very like condemnation of a man’s conduct and character to dismiss him from office when popular clamour is against him? Vague reports and unfounded rumours went abroad concerning me; the Native Managers confirm them by acting towards me as they have done. Excuse my saying it, but I believe there was a determination on their part to get rid of me, not to satisfy popular clamour, but their own bigotry. Had my religion and morals been investigated by them, they could have had no grounds to proceed against me. They therefore thought it most expedient to make no enquiry, but with anger and precipitation to remove me from the Institution. The slovenly manner, in which they have done so, is a sufficient indication of the spirit by which they were moved, for in their rage they have forgotten what was due even to common decency. Every person who has heard of the way in which they have acted is indignant, but to complain of their injustice would be paying them a greater compliment than they deserve.

I am aware that for some weeks some busy bodies have been manufacturing the most absurd and groundless stories about me, and even about my family… Vague reports and unfounded rumours went abroad concerning me; the Native Managers confirm them by acting towards me as they have done. Excuse my saying it, but I believe there was a determination on their part to get rid of me, not to satisfy popular clamour, but their own bigotry.

In concluding this letter, allow me to apologise for its inordinate length; and to repeat my thanks for all that you have done for me in the unpleasant affair by which it has been occasioned.

I remain, Sir, & c.

H.L.V. Derozio.

April 26,1831

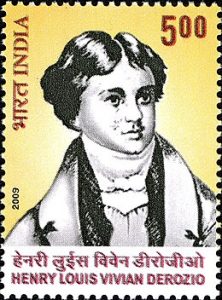

A stamp in Derozio’s honour

The Examination of the Pupils of the Durrumtollah Academy, conducted by Messrs. Drummond and Wilson, took place on Saturday last. Many ladies and gentlemen were present at this interesting exhibition, which appeared to give very general satisfaction Dr. Bryce, Dr. Tytler, Dr. Grant, Mr. D. L. Richardson, Mr. Adam, the Reverend A. Duff, Mr. Speed of the Hindoo College, Muha Rajah Kaleekrishun, Baboo Radha Prasad Roy and other distinguished gentlemen encouraged the youthful candidates by their presence. Dr. Tytler examined the Mathematical, Geographical, and Astronomical classes, with the proficiency of which he was quite satisfied. The Book-keeping class was put to severe test by Mr. Speed; but the boys were too knowing to be puzzled, and in a few minutes they satisfied him of their ability to journalize and post into the ledger any mercantile transaction. We believe that Mr. Drummond has the merit of having first introduced into the schools here the practice of teaching book-keeping by means of brass counters, which pass among the boys for goods and species. Thus, the transactions which their books exhibit are bonafide real ones; and the interest which their purchases and sales excite among themselves is the principal cause of their retaining the instruction which is communicated to them. The Durrumtollah Academy maintains, in this respect, the character which it has always enjoyed. The French class acquitted itself with more ease and tact than any of the French classes in the other schools. The Examination terminated at about 4 o’ clock.

The most pleasing feature in this institution is its freedom from illiberality. We have a particular reason for noticing this circumstance. At some of the schools in Calcutta objections are made to native youth, not so much on the part of the masters as of the Christian parents who have children at those schools. At the Durrumtollah Academy however, there is none of this illiberal feeling; and it is quite delightful to witness the exertions of Hindoo and Christian youth, striving together in the same classes for academical honors. This amalgamation will do much towards softening those asperities which always arise in hostile sects; and when the Hindoo and the Christian have learned from mutual intercourse how much there is to be admired in the human character without reference to differences of opinion in religious matters, shall we not be brought nearer than we now are to that happy condition

When man to man the world o’er,

Shall brothers be and a’ that

To those parents who object to the bringing up of their children among native youth, we desire to represent the suicidal nature of their conduct. Can they check the progress of knowledge at certain schools; can they close the gates of the Hindoo College and other institutions of a similar description? If not, is it not obvious that they cannot withhold knowledge from Hindoo Youth? And if they manifest an illiberal feeling towards those youth are they not afraid of a re-action? In a few years the Hindoos will take their stand by the best and the proudest Christians; and it can not be desirable to excite the feelings of the former against the latter. The East Indians complain of suffering from proscription: is it for them to proscribe? Suffering should teach as not to make others suffer. Is it to produce a different effect upon the East Indians? We hope not. They will find after all, that it is their best interest to unite and co-operate with the other native inhabitants of India. Any other course will subject them to greater opposition than they have at present to encounter. Can they afford to make more enemies?

To those parents who object to the bringing up of their children among native youth, we desire to represent the suicidal nature of their conduct. Can they check the progress of knowledge at certain schools; can they close the gates of the Hindoo College and other institutions of a similar description? If not, is it not obvious that they cannot withhold knowledge from Hindoo Youth? And if they manifest an illiberal feeling towards those youth are they not afraid of a re-action? …The East Indians complain of suffering from proscription: is it for them to proscribe? Suffering should teach as not to make others suffer. Is it to produce a different effect upon the East Indians?

-East Indian, 17th December, 1831

Derozio’s grave

Death! my best friend, if thou dost open the door,

The gloomy entrance to a sunnier world,

It boots not when my being’s scene is furled,

So thou canst aught like vanished bliss restore.

I vainly call on thee, for Fate the more

Her bolts hurls down as she has ever hurled:

And in my war with her, I’ve felt, and feel

Griefs path cut to my heart by misery’s steel.

But man’s eternal energies can make

An atmosphere around him, and so take

Good out of evil, like the yellow bee

That sucks from flowers malignant, a sweet treasure—

O tyrant Fate! thus shall I vanquish thee,

For out of suffering shall I gather pleasure.

Expanding, like the petals of young flowers,

I watch the opening of your infant minds,

And the loosening of the spell that binds

Your intellectual energies and powers

That stretch, like young birds in soft summer hours,

Their wings, to try their strength. O! how the winds

Of circumstances, and gentle April showers

Of early knowledge, and unnumbered kinds

Of new perceptions shed their influence:

And how you worship truth’s omnipotence!

What gladness rains upon me, when I see

Fame, in the mirror of futurity,

Weaving the chaplets you are doomed to gain,

And then I feel I have not lived in vain.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

The writeup was simply superb after reading which I have fallen in love with Derozio. To the point. Clear language. Apt headings. Not even a sentence unrelated. Tone maintained properly. Totally giving out profusely what it intended. Bravo!