The Great War, as the First World War came to be known, is widely considered to be a European conflict. In spite of that several Indians fought on various fronts of the war owing to the fact that India was a British colony then. The India Gate, located in the epicentre of the new capital built by the British, stands to commemorate those Indian soldiers who lost their lives in this war. Andrew T. Jarboe in the introduction to his book Indian Soldiers in World War I: Race and Representation in an Imperial War writes, “More than one million Indian soldiers were deployed overseas to fight on behalf of the British Empire in the Indian Army during World War I. They fought in France and Belgium, Egypt and East Asia, Gallipoli, Palestine and Mesopotamia.” Nariman Karkaria, a Parsi from Navsari in Gujarat, was one of the few soldiers who not only saw action on three different fronts, lived to tell the tale, but also left a first-hand account of the War. Originally in Gujarati, Karkaria’s account of the Great War was titled Rangbhoomi par Rakhad and has only recently been translated into English by Murali Ranganathan as The First World War Adventures of Nariman Karkaria. So far it is only one of the two known first-hand accounts of Indians soldiers who fought in World War I.

What is also interesting is that Karkaria fought in the Great War not as part of the British-Indian Army but as part of the British Army. “Karkaria’s preference for a British regiment was rooted in how the Parsi elite constructed their self images,” writes Ranganathan while introducing the book. His preference for the British army was not without precedent. Even before him, Karesasp Naoroji, who also happens to be the grandson of the illustrious Dadabhai Naoroji, had managed to enlist himself with the 24th Middlesex Regiment. Karkaria joined the Middlesex Regiment as a private and was dispatched to the Western Front. It was at this front that Karkaria fought in the now iconic Battle of the Somme. One the deadliest battles of the First World War and fought in Northern France between the joint British and French forces against the Germans, the offensive at the Somme was intended to hasten a victory for the Allied Powers. While the result of the battle did not quite achieve that, it gave the Allied Powers or the Triple Entente the hope that they could win the war. The British Commander in Chief, General Sir Douglas Haig, in his report of the battle, wrote, “The enemy’s power has not yet been broken, nor is it yet possible to form an estimate of the time the war may last before the objects for which the Allies are fighting have been attained. But the Somme battle has placed beyond doubt the ability of the Allies to gain those objects.”

Karkaria’s account also depicts the deadliness of the battle with great immediacy. In one instance, he writes, “We were staring death in the eye. But as luck would have it, there had been a fierce battle on this very site just four days ago, and the bodies of the dead soldiers were lying all around us. These corpses proved very useful in sheltering us from the enemy gunfire. As we advanced, we would lie behind these corpses, and they would act as our shield taking all the gunfire. Ah, what a terrible experience! Just one bullet and we would also have joined the army of cold corpses!” Although injured at the Somme, Karkaria would not only live to tell his tale, but also later on join the 5th Middlesex Regiment and take part in the action at the Western Asian front, including the battle that led to the Allied conquest of Jerusalem, and then again at the Balkan front as part of King Edward’s Horse.

“On his return to India in May 1920,” writes Ranganathan, “He would have received a hero’s welcome. He had returned home to Navsari, Gujarat, after nearly six years, and there were many listeners eagerly waiting for him to recount his adventures. This might have been the genesis for his column in a Gujarati newspaper chronicling his war experiences. The column was serialized from late 1920 all through 1921. The articles were then collected and published in the form of a book titled Rangbhoomi par Rakhad, which was published in 1922.”

What is truly remarkable about Karkaria’s account is that is contains all the anti-war elements of an All Quiet on the Western Front, while also being, in Amitav Ghosh’s words, “in every sense a unique work, in the story that it tells, in the swashbuckling manner of its telling, and not least, in the excellence of Murali’s translation, which conveys the writer’s spirit so vividly that one can almost hear him reminiscing aloud to enthralled listeners at the Ripon Club in Mumbai, or the Meherjirana Library in Navsari”.

The chapter from the translation that we have reproduced below, titled ‘The Battle of the Somme’ bears testimony to these words.

The Battle of the Somme

Nariman Karkaria

At last, it was our turn to see action, something we had been waiting for with our eyes peeled. Some of the soldiers were very eager to see the Germans in person and flaunt their muscle power, while quite a few were most distressed by the orders to advance forward to the front lines. We were to participate in the Battle of the Somme, which has already achieved legendary status in the Great War.

The Role of the Indian Army

Indian bicycle troops at a crossroads on the Fricourt-Mametz Road, Somme, France. Dated July 1916. From the collection of Imperial War Museums, London.

The Indian Army also took part in the Battle of the Somme.

The Bengal Lancers advanced under heavy fire from the Germans right up to the German trenches and forced them to retreat. On this occasion, our platoon was ordered to advance to the firing line. Our undercover march started at about one o’clock in the night. We had been strictly warned not to utter a single word. With great difficulty, we managed to advance, digging a few trenches and walking all through the night, only to find ourselves in a very unfortunate position in the morning. A German observation balloon which had been flying above us had spotted us, and very soon our route came under heavy fire. Shells were exploding all around us. To escape them, we would lie flat on the ground for a short while before running to advance a little forward. A wave of fear rippled through our platoon. Soldiers were falling all around us with piteous shrieks, but there was nothing that could be done. Each man was on his own and could not be bothered about anybody else. Others would advance by stepping on those injured soldiers who had fallen to the ground. We had no option but to move forward. We also had no idea what kinds of difficulties we were to face as we advanced. Many of our men were lagging behind, but we could not wait for them, and at about twelve noon we reached the famous jungles of Del Ville Wood where we felt we could finally heave a sigh of relief. But fate had other things in store for us. There were no trenches beyond the next twenty-five yards from where we were located. We could not step out of the trenches as we would have been sitting ducks for German guns. The Germans were hardly at any distance from where we were—say about a hundred yards away in their trenches. In spite of this situation, the Commanding Officer gave orders to advance further. We had no option but to run, and we ran in pairs. We would advance about ten steps before throwing ourselves flat on the ground. Our progress did not last very long. Soon enough, the enemy started firing at us with their machine guns.

We were staring death in the eye. But as luck would have it, there had been a fierce battle on this very site just four days ago, and the bodies of dead soldiers were lying all around us. These corpses proved very useful in sheltering us from the enemy gunfire. As we advanced, we would lie behind these corpses, and they would act as our shield taking all the gunfire. Ah, what a terrible experience! Just one bullet and we would also have joined the army of cold corpses!

War in the Skies

After a very desperate battle and the loss of over fifty soldiers, we were lucky enough to be able to take possession of the trenches. Because of the non-stop action during the night and the better part of the day, we had not even had a cup of tea, much less anything to eat. I had managed to eat a couple of biscuits while moving forward. This was all I had had, with which I had to be content for the whole day. Once we took possession of the trenches, the different companies of the platoon were immediately assigned positions. While the A and C Companies were assigned the forward trenches, the B Company was assigned the communication line, which was about ten yards behind us, and the D Company was a further fifteen yards behind them in the support line. We were immediately ordered to make structural improvements in the trenches, which meant more digging. These trenches were not deep enough for a man to stand erect. The soldiers were tired of standing with their backs bent for extended lengths of time. The trenches were also rather narrow and we could hardly move around in them. We began using our small shovels and spades, and started digging at a steady pace, making as little noise as possible. We had hardly started digging when the sky above us was criss-crossed by enemy planes. They had been sent to monitor our progress and signal our position. Soon enough, our lines were bombarded by their artillery positions and we had to suspend our digging operations. Before we go further ahead with our story, let us take a look at the role of these aeroplanes in the war.

These aerial barques would fly high over enemy camps and their trenches, and photograph our positions to determine where the enemy was concentrated and how their lines were positioned. They would then go back and relay all the information to the base. They were, however, most deadly when they worked in conjunction with the artillery. These planes would be assigned to specific batteries; during an assault, these planes would hover above the enemy lines and relay back information on where the shells were landing. If the shells were landing at too short or too long a distance from the enemy trenches, they would immediately ask the battery to adjust its range. If they spotted a shell that had landed at the right place, they would immediately signal a ‘repeat fire’ to completely pulverize the position. Sometimes they would come in huge numbers and we would be carpeted with aerial fire. These aerial barques completely terrorized everybody in the trenches. The minute they appeared above us, we would be ordered to remain as still as possible. If we froze in our positions, it was possible that they might not spot us.

These planes were also mounted with machine guns that would merrily go ‘Bang! Bang!’ and wreak havoc on those below. Occasionally, planes from both the sides would engage each other in the skies, and this was indeed a sight to behold.

To contain these demons of the skies, a different kind of specially designed artillery known as ‘anti-aircraft guns’ would be deployed. They would keep up a relentless fire on the planes from the minute they were spotted.

Storm on a Dark Night

This being our first day in the firing-line trenches, all the soldiers were not assigned specific duties. Some of them were free while others were stationed at specific locations on sentry duty in batches. As these trenches were not deep enough for the soldiers to stand erect and peep over them to monitor the enemy’s movements, a special glass contraption was designed, which could be attached to the tip of the bayonet of one’s gun. This helped the sentry sit down and monitor the space between our trenches and those of the enemy. At short intervals, they would slightly raise their guns very carefully, and peep into the glass and see if there were any enemy advances. Every so often, German snipers would shoot at the bayonets of these soldiers with perfect aim. These German snipers were a real nuisance. At night, snipers from both sides would emerge from the trenches and shoot at the slightest movement. Besides these man-made miseries, we also had to face the fury of nature. In addition to the relentless noise of heavy guns firing through the dark night, we had to brave the most frightful thunder accompanied by incessant rain. It would rain all through the night and the trenches would be flooded. We would be standing in chest-deep water, wondering when the enemy would mount a surprise attack. Even as our boots and clothes were weighed down by the squelching mud and water, our officers would keep braying at us: ‘Beware! The enemy might attack!’ Buffeted from all sides and terrorized by the incessant guns, there were many soldiers who felt it would be far better to emerge from the trenches and take a chance with the enemy gunfire. There were others who were so paralysed by fear that they would appear almost insane and would not stir from their positions. Even if they had to answer nature’s call, they would be unable to take a single step. They would just dig a shallow hole right where they were and do their dirty business. In spite of their paralysis, they were somehow drafted to do some work by the booming orders of the officers. As mentioned earlier, the front line was manned by batches, each batch consisting of one sentry and five soldiers, with a non-commissioned officer in charge of them. They were responsible for holding the front line, and each soldier had to be on strict lookout for one hour at a time. A Lewis gun or a machine gun would be placed between every three batches. If the sentry felt that the enemy was trying to make an advance or if there was the slightest movement detected in the enemy lines, the guns would start firing. These Lewis guns played a very important role in this devastating war. These lightweight guns weighed only twenty-nine pounds and could be easily handled by one man who could move it from place to place, and when ordered, start firing at the rate of four hundred bullets per minute. Each of these guns was equivalent to a hundred rifles. We always had to be prepared at the firing line with all these arrangements.

Tear-Inducing Chilli Bombs

Indian infantry in the trenches, prepared against a gas attack [Fauquissart, France]. Dated 9th August, 1915. From the HD Girdwood collection, British Library.

After spending a miserable night in the trenches, we were shivering in our wet clothes in the morning. Suddenly we were ordered to ‘Stand to!’ Now what was this for? Even as we were wondering what it was all about, a gas that felt like chillies began pervading the trenches. Shrill orders to wear our goggles were urgently issued.

When the gas first attacked us, we could hardly understand what was happening. The gas began to envelop us from every direction and gas shells lobbed from the enemy lines were silently exploding all around us. Our eyes were in a state of extreme irritation. It felt as if they would burst.

We could hardly see anything; tears were flowing freely from our eyes, and it felt dark and terrifying. In spite of all this, everybody got into fighting position, facing the enemy lines and waiting for the inevitable attack. It was generally understood that the enemy released this gas just before it launched an attack. It rendered our soldiers blind and immobile for a brief while, and during this period, they could get the better of us and wrest our trenches. We could hardly open our eyes since the chilli gas had caused our eyes to turn red and swell up. How was a soldier to fight under such adverse circumstances? Along with this chilli gas, regular artillery fire was also kept up by the enemy, which further exacerbated the situation. To combat the nuisance of these ‘tear shells’ and to protect the eyes, a special kind of protective spectacles had been designed. They were made of ordinary glass through which everything could be seen, and the frame was fringed with flannel which ensured that the gas did not make contact with the eyes. The only saving grace was that exposure to tear gas, unlike poison gas, was not fatal; it merely left you blind for a short while.

On a Starvation Diet

Besides all the problems described above, we had yet another major problem to contend with: how to silence our hunger pangs. Soldiers on the firing line had to remain awake day and night and had no chance to lie down. To make matters worse, they had to scrounge for food. Admittedly, there was a lot of food dumped beyond the support lines as the motor transport guys would weave through the heaviest artillery fire to supply the food. Transporting the food from the dump to the firing lines was a major challenge for the soldiers. They would step out in large numbers to bring the food stuffed in small gunny bags back from the dump to the front line. The extreme conditions in the trenches, what with them being flooded with rainwater and slush, and the incessant firing of the enemy many a time prevented them from returning safely. They would be injured and fall down en route, and the food would also lie rotting there. The situation at the firing line was indeed desperate. The D Company had been assigned the support line and was responsible for supplying us with food, but as they came under heavy fire, they could not venture out of their trenches. Even though we were at the very front, the lines immediately to our rear suffered the most, bearing the brunt of the artillery fire. At least fifteen to twenty men from one company would get injured every day, and the condition of the injured was indeed very pitiable. How was food to reach us under this situation? We had to subsist on the few packets of biscuits and bully beef we had carried with us. Where was the question of getting a hot cup of tea? Not a single wisp of smoke was supposed to escape from the trenches. If the enemy spotted smoke coming from a trench, they would consider it to be a live target and fire immediately. The poor soldiers would go scrounging around for cigarette stubs.

Such was the dire situation at the front lines—starvation, mud and slush—and the relentless artillery fire had so harassed the soldiers that they were a pathetic sight to behold.

They had not shaved for days. How do you think they looked? It is best left to the imagination!

Our Final Assault

King George V inspecting Indian troops attached to the Royal Garrison Artillery, at Le Cateau on 2 December 1918. Imperial War Museums, London.

This was to be our last day at the famous Del Ville Wood. After many days of suffering and troubles, would it be too much to say that our imminent relief seemed like a new lease of life to us? Early in the morning, the news had already spread in the trenches that we were to be relieved tonight; our faces were aglow with delight. Just after noon, more authoritative news reached us, which was slightly different. We were indeed to be relieved, but we would have to perform some more arduous tasks tonight; the soldiers welcomed this news as a means of getting out of the trenches. All of us had been eagerly looking forward to being relieved for many days. Instead of spending yet another day in the slushy trenches, it was more preferable to emerge from them and show our courage in hand-to-hand combat. As per the orders issued to us, we were to launch our attack at ten in the night. Two companies were to lead the attack while the other two companies were to support us in the assault, and the trenches which we were to evacuate were to be occupied by the 4th Suffolk Regiment. All preparations had been made for a full-on artillery assault at the same time. Some of the soldiers were eagerly looking forward to the hour of the assault, while the colour had drained out of the faces of others. This supposedly minor assault was sure to claim the lives of many soldiers, but nobody knew who it would be. As things turned out, luck was on our side on this dark and evil night. It was pitch dark and the rain was falling steadily, and the roads were so slushy that they were of a porridge-like consistency. The enemy might have felt that there was very little likelihood of an attack from us in such awful weather. Our strategy was to attack under the cover of bad weather. Every minute seemed like an hour. As we waited, we could hear our hearts beating within our chests. After a seemingly eternal wait, it was finally the dark hour when we were to launch our attack. Just as orders were barked out to get us ready for the final assault, a volley of artillery fire passed over our heads towards the enemy lines. Within the blink of an eye, the Germans returned fire. Hundreds of shells were exploding loudly all around us. Their smoke darkened the skies, and we were already so scared that any enthusiasm we might have had for escaping from the trenches evaporated. Before we could think any further, orders were screamed out: ‘Over the top! Best to luck!’ The minute we heard the orders, we jumped out of the trenches and emerged into the open. We could soon hear the plaintive screams of our fellow soldiers, many of whom had fallen victim to the fire from the mortars and the machine guns. The rest of us braves, mindless of the fate of our colleagues, kept advancing. Lying flat on the ground, we crawled for over an hour and were lucky enough to finally make it to the enemy front lines. We then lobbed small bombs into their trenches and soon jumped into the trenches for a face-to-face duel. At this stage, many soldiers lost their lives to close-range enemy bullets, while some were bayoneted to death. We were able to take ten prisoners and capture one machine gun. We were about to turn back but heavy enemy artillery fire prevented us from doing so.

This was the heaviest bombardment I had ever seen, with thousands of shells exploding simultaneously all around us.

Because of the rain, mud and slush, our clothes felt like they weighed a ton. Dragging all this paraphernalia with us, a few of us were lucky enough to get back to our lines. Even as we were luxuriating in our good fortune, Lady Luck finally deserted us. A heavy shell landed just ten yards from where we were and exploded very loudly; we tried to jump away from it, but were not lucky enough to escape without being hit. I was also hit by a fragment. Even though I jumped as quickly as I could into a trench, my leg was injured in a gruesome manner. This had to happen just on the very last day when we were about to be relieved from trench duty. When fate turns against you, there is nothing you can do!

Adding Insult to Injury

Like me, there were hundreds of injured soldiers moaning and lying unattended in the trenches.

There was nobody to listen to our groans or pay any attention to us. Our troubles were just starting. If you managed to reach the dressing station, your troubles could come to an end. But in this bloody battle, it seemed like an impossibility. It was routine for hundreds of soldiers to get injured every day, and each platoon had its own stretcher-bearers who were supported by men from the Royal Army Medical Corps. For this assault, special working parties had also been formed. The firing and the destruction was, however, so severe that all these arrangements came to nought. Unlucky soldiers with stomach or leg injuries would frequently die a painful death in the trenches. If an injured soldier managed to drag himself away from the action, he stood a better chance of survival. Once you reached the dressing station, you would be one among thousands of injured soldiers crying for medical attention. The best possible care was given to them. There would be trolleys and vehicles from the Ambulance Corps to take them to the casualty clearing station. Once you reached this location, you could safely assume that your troubles had come to an end. All it needed was a cup of hot tea to make the injured soldier feel much better. After the seemingly endless days of nightmarish existence starving in the trenches, a cup of tea and the ministrations of female nurses felt like heaven. And then it was ‘Back for Blighty!’

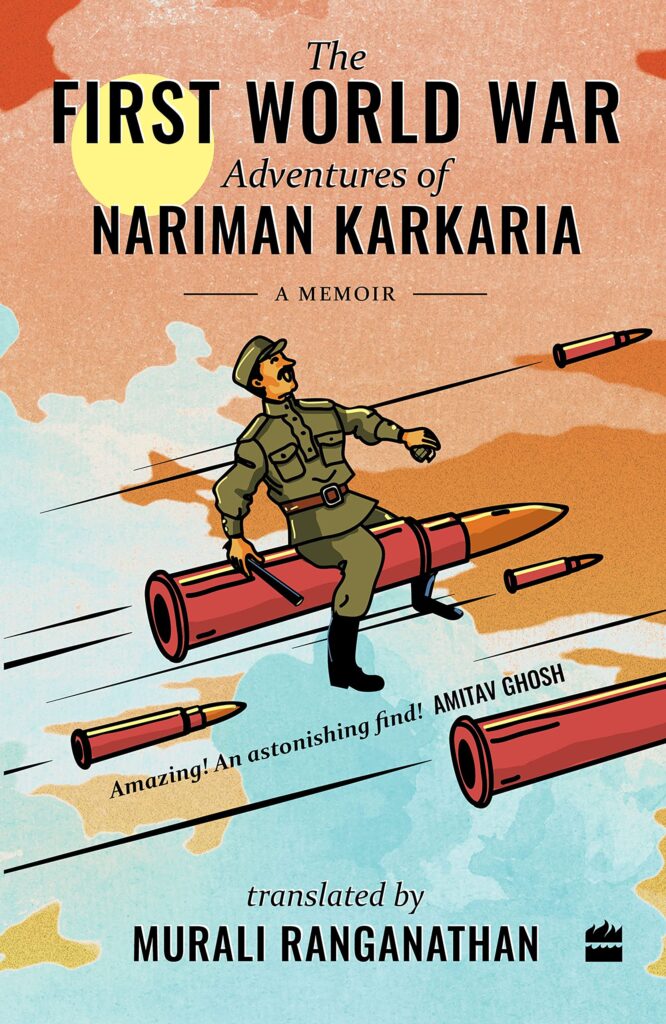

This excerpt has been reproduced in arrangement with Harper Collins Publishers India Private Limited from the book The First World War Adventures of Nariman Karkaria: A Memoir written by Nariman Karkaria and translated by Murali Ranganathan. All rights reserved. Unauthorised copying is strictly prohibited. You can buy the book here.

An Indian-Parsi soldier who fought in World War I, Karkaria is one of the two Indian soldiers who have left behind a first-hand account of the War. Karkaria was also one of the few soldiers who saw action on three different theatres or fronts of the Great War-the Western front, the Western-Asian (Middle-Eastern) front and ultimately the Balkans front, being part of some of the most important battles as well such as the Battle of Somme and the Battle of Jerusalem. He returned to his hometown of Navsari, Gujarat in May 1920 and started writing columns in a Gujarati newspaper chronicling his war experiences. These columns were then collected and published in the form of a book titled Rangbhoomi par Rakhad. This has been recently translated into English by Murali Ranganathan as The First World War Adventures of Nariman Karkaria: A Memoir.

Leave a Reply