Nehru Memorial Museum & Library

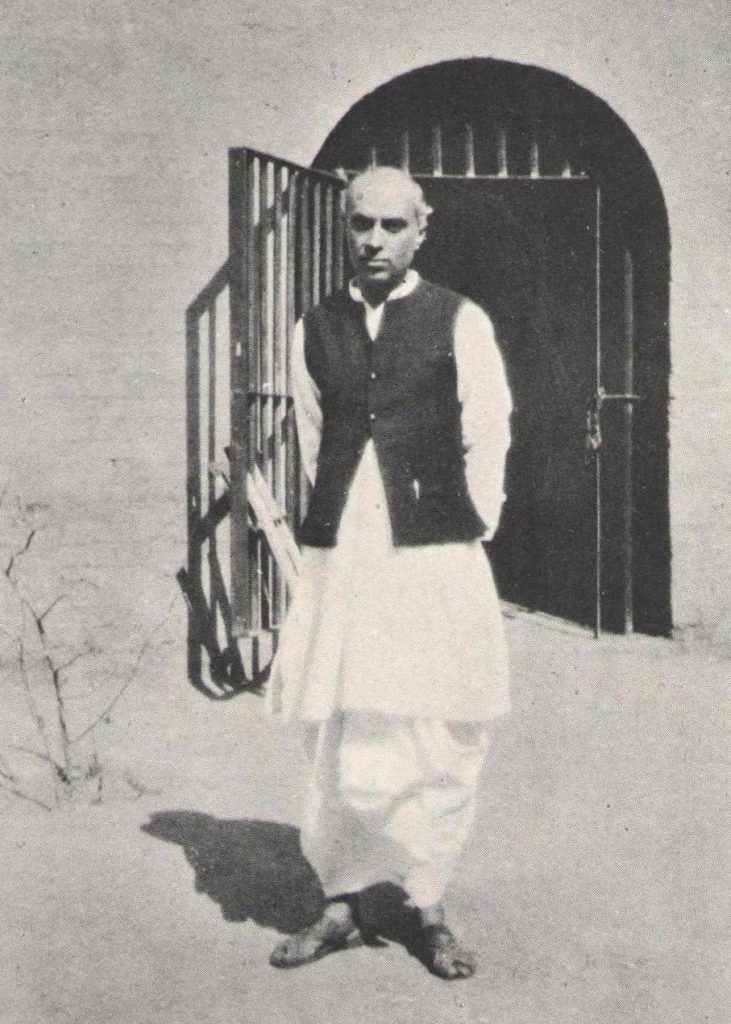

Some 85 years ago, sitting in Almora Jail, Jawaharlal Nehru penned some thoughts on the Indian justice system. Although he called it The Mind of a Judge, his essay ranged across the nature of the justice system and also touched upon the state’s use of violence to maintain law and order and prevent “smaller violences” as he termed it.

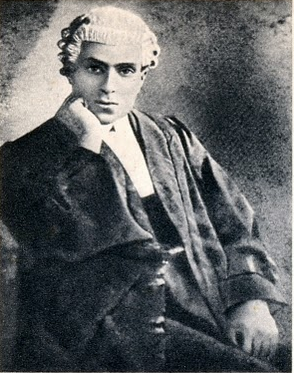

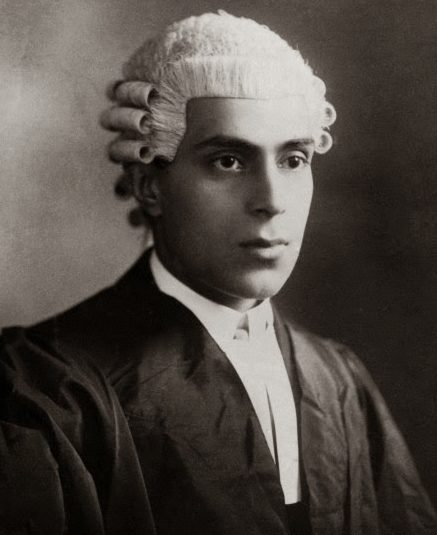

It is important to note that Nehru was a barrister, and the son of a famous barrister, and also that he had spent many years in jail by this period. He knew the justice system inside out and this lends an air of authenticity to the essay.

It is also worth noting that, by 1935, the Indian Imperial Police Service was largely staffed by Indians, and so was the Indian Civil Service. There were plenty of Indians officiating in the judiciary as well. The “other ranks” of the Raj’s justice system, policemen, prison staff, were entirely Indian in composition.

Reading this essay in 2020, one might be driven to despair because the abuses that Nehru so eloquently rails against are still very much in evidence nine decades later. But that continuity offers us a historical perspective that helps, to some extent, to make this explicable. Independence made little difference to the contours of the justice system. Exactly the same people, trained in the same Imperial Macaulay-ite tradition, continued to run it in 1947 and their successors inherited their mind-set too.

Nehru speaks of the gulf between the class of the typical judge and the typical criminal and how there is this utter lack of empathy between the one who passes down a sentence and the prisoner who serves it. That gulf remains.

He speaks of the fact that “a harsh penal code does not improve the social morals of a group, nor a harsh sentence those of an individual who has lapsed from grace.” This was hardly the prevailing opinion when the Indian Penal Code was imposed in the 1860s and it was an unpopular point of view in 1935. The deterrent value of harsh punishment was considered the best policy. Unfortunately the IPC remains stuck in 1861 and so apparently does the mindset of those who manage the justice system.

In addition, there was the shambolic mismanagement and lack of capacity which led, in 1935, to thousands of petty accused sitting in jail for years while awaiting trial. That situation is even worse in 2020. There were also the absurd charges where a criminal who stole one rupee (about Rs 75 in 2020 purchasing power) was sentenced to serve three years. A similar situation prevails today when somebody accused of stealing a light bulb spends years in jail.

It is when Nehru speaks of the treatment of political prisoners that the resonances are the strongest and most bitter.

“The usual political sentence now for a speech or a song or a poem which offends the Government is two years rigorous imprisonment (in the Frontier Province it is three years) and a lavish use of this is being made from day to day; but even this seems trivial when compared with the cases of large numbers of those people who are kept confined for four or five years or more, indefinitely, without conviction or sentence.”

“It is also well known that many people, who are considered politically undesirable by the police, are proceeded against under the bad livelihood or similar sections of the code and clapped in prison as bad characters with no special offence being brought up against them.”

Sundry anti-terrorism acts have been patched onto the IPC to make this an even more common situation circa 2020. Political prisoners are eliminated by encounters, or routinely incarcerated without bail for speaking up. The Bhima Koregaon case, the incarceration of a pregnant woman and of barely legal teens for expressing opinions that the government doesn’t like, are occurrences that barely make it to the mainstream news.

At the extreme limit of libertarian philosophy, one of the definitions of a state is that it has the right to collect taxes and that it has a monopoly on lawful violence. Nehru acknowledges that when he says state violence may be preferable to “numerous petty private violences”.

But as he adds that “when a State goes off the rails completely and begins to indulge in disorderly violence, then indeed it is a terrible thing, and no private or individual effort can compete with it in horror and brutality”.

Those of us who have witnessed the engineered pogroms that started in the 1980s – and have since been raised to an art-form – will concur wholeheartedly with this sentiment. Ditto for those who have witnessed the policing methods commonly used to combat left wing insurgencies and separatists in the North East and Kashmir.

Nehru offered few policy prescriptions beyond the Utopian: those who run the Justice system should voluntarily spend some time in prison.

It is a sad, sad commentary on our justice system and on our ritualistic observances of the forms of parliamentary democracy that Nehru’s essay could have been written yesterday.

—Devangshu Datta

The days when I practiced at the Bar are distant and far-off, and I find it a little difficult now to recapture the moods that must have possessed me. And yet it was only sixteen years ago that I walked out of the web of the law in more ways than one. Sometimes when I look back on those days, for in prison one grows retrospective and, as the present is dull and monotonous and full of unhappiness, the past stands out, vivid and inviting. There was little that was inviting in that legal past of mine and at no time have I felt the urge to revert to it. But still my mind played with the ifs and possibilities of that past – a foolish but an entertaining pastime when inaction is thrust on one – and I wondered how life would have treated me if I had stuck to my original profession. That was not an unlikely contingency, though it seems odd enough now: a slight twist in the thread of life might have changed my whole future. I suppose I would have done tolerably well at the Bar and I would have had a much more peaceful, a duller, and physically a more comfortable existence than I have so far had. Perhaps I might even have developed into a highly respectable and solemn-looking judge with wig and gown, as quite a number of my old friends and colleagues must have done.

How would I have felt as a judge? I have wondered. How does a judge feel or think? This second question used to occupy my mind to some extent even when I was in practice conducting or watching criminal cases, lost in wonder at the speed and apparent unconcern with which the judge sent men to the scaffold or long terms of imprisonment. That question, in a more personal form, has always faced me when I have stood in the prisoner’s dock and awaited sentence, or attended a friend’s trial for political offences. That question is almost always with me in prison, surrounded as I am with hundreds or thousands of persons whom judges have sent there. (I am not concerned for the moment with political offenders; I am only referring to the ordinary prisoners.) The judge had considered the evil deed that was done and he had meted out justice and punishment as he had been told to do by the penal code. Sometimes he had added a sermon of his own, probably to justify a particularly heavy sentence. He had not given a thought to the upbringing, environment, education (or want of it) of the prisoner before him. He had paid no heed to the psychological background that led to the deed, or to the mental conflict that had raged within that dumb, frightened creature who stands in the dock. He had no notion that perhaps society, of which he considers himself a pillar and an ornament might be partly responsible for the crime he is judging.

He is, let us presume, a conscientious judge, and he weighs the evidence carefully before pronouncing sentence. He may even give the benefit of the doubt to the accused, though our judges are not given to doubting very much. But, almost invariably, the prisoner and he belong to different worlds with very little in common between them and incapable of understanding each other. There may sometimes be an intellectual appreciation of the other’s outlook and background, though that is rare enough, but there is no emotional awareness of it, and without the latter there can never be true understanding of another person.

Sentence follows, and these sentences are remarkable. As the realization comes that crime is not decreasing, and may even be increasing, the sentences become more savage in the hope that this may frighten the evil-doer. The judge and the power behind the judge have not grasped the fact that crime may be due to special reasons, which might be investigated, and that some of these may be capable of control; and further that in any event a harsh penal code does not improve the social morals of a group, or a harsh sentence those of an individual who has lapsed from grace. The only remedy they know, both for political and non-political offences, is punishment and an attempt to terrorise the offender by what are called deterrent sentences. The usual political sentence now for a speech or a song or a poem which offends the Government is two years rigorous imprisonment (in the Frontier Province it is three years) and a lavish use of this is being made from day to day; but even this seems trivial when compared with the cases of large numbers of those people who are kept confined for four or five years or more, indefinitely, without conviction or sentence.

Political cases, however, depend greatly on the moods of Government and a changing situation, and do not help us in considering the ordinary administration of the criminal law. To some extent the two overlap and affect each other, for instance, many agrarian and labour cases in courts are often definitely political in origin. It is also well known that many people, who are considered politically undesirable by the police, are proceeded against under the bad livelihood or similar sections of the code and clapped in prison as bad characters with no special offence being brought up against them. Ignoring such cases and considering what might be called the unadulterated crimes, two facts stand out: both the numbers of convictions and the length of sentences are growing. Every year the various provincial prison reports complain of the increasing number of prisoners and the necessity of additional accommodation. The peak years, when the civil disobedience movement sent its scores of thousands to prison, become the normal years even without this special influx of political. Occasionally the difficult is overcome by discharging a few thousand short timers before their time, but the strain continues.

The Central Prisons are full of ‘lifers’, prisoners sentenced for life, and others sentenced to long terms. Most of these ‘lifers’ come in huge bunches in dacoity cases and probably a fair proportion are guilty, though I am inclined to think that many innocent people are involved also, as the evidence is entirely one of identification. It is obvious that the growing number of dacoities are due to the increasing unemployment and poverty of the masses as well as the lower middle classes. Most of the other criminal offences involving property are also due to this terrible prospect of want and starvation that faces the vast majority of our people.

Do our judges ever realise this or give thought to the despair that the sight of a starving wife or children might produce even in a normal human being? Is a man to sit helplessly by and see his dear ones sicken and die for want of the simplest human necessities? He slips and offends against the law, and the law and the judge then see to it that he can never again become a normal person with a socially beneficial job of work. They help to produce the criminal type, so-called, and then are surprised to find that such types exist and multiply.

The major offences lead to a life sentence of ten years or so. But the petty offences and the way they are treated by judges are even more instructive. The vast majority of these are buried in court files and get no publicity: only rarely do the papers mention such a case. Three such cases, taken almost at random from recent issues of newspapers, are given below:

Rahman was an old offender with 12 previous convictions, the first of which dated back to 1913. The present offence was one of theft of clothes valued at a few rupees. Rahman pleaded guilty and requested the court to send him to a reformatory or some such place from where he could emerge thoroughly reformed. The judge, who was the Judicial Commissioner in Sind, refused this request and sentenced him to seven years, adding: “If this seven-year sentence of hard labour does not reform you, God alone must come to your aid.” (Karachi: May 23, 1935.)

Badri who had four previous convictions, was sentenced to two years’ rigorous imprisonment under Sections 411/75 IPC for having dishonestly received a stolen cheddar (cloth sheet). (Lucknow: July 3, 1935.)

Ghulam Mohammad, an old offender, was sentenced to three years’ rigorous imprisonment for stealing one rupee by picking the pocket of a man. (Sialkot: July 15, 1935.)

These and similar sentences may be perfectly correct from the point of view of the Indian Penal Code but it does seem to me astonishing that any judge should imagine that by inflicting such sentences he is reforming the offender. Evidently the Judicial Commissioner in Sind had himself some doubts about the efficacy of his treatment for he hinted that God might be given a chance on the next occasion.

There they sit, these judges, in their courts, and a procession of unfortunates passes before them – some go to the scaffold, some to be whipped, some to imprisonment, to which may be added solitary confinement. They are doing their duty according to their abstract ideas of justice and punishment; they must consider themselves as the protectors of society from anti-social criminal elements. Do their thoughts ever go beyond these set ideas and take human shape considering the miserable offender as a human being with parents, wife, children, friends? They punish the individual but at the same time they punish a group also, for the ripples of suffering spread out and go far. Those who have to die at least die swiftly, the agony is brief. But the agony is long for those who enter prison.

“Behind the door, within the wall

Locked, they sit the numbered ones…”

Two years, three years, seven years stolen from life’s brief span – each year of twelve months, each month of thirty days, each day of twenty-four hours – how terribly long it all seems to the prisoner, how wearily time passes!

All this is very sad and deplorable no doubt, but what is the poor judge to do? Is he to wallow in a sea of sentimentality and give up sentencing offenders against the laws? If he is so soft and sensitive he is not much good as a judge and will have to give place to another. No, no one expects the judge to embrace every offender and invite him to dinner, but a human element in a trial and sentence would certainly improve matters. The judges are too impersonal, distant, and too little aware of the consequences of the sentences they award. If their awareness could be increased, as well as a sense of fellow-feeling with the prisoner, it would be a great gain. This can only come when the two belong to more or less the same class. A financier who has embezzled vast sums of public money will have every sympathy from the judge, not so the poor wretch who has picked up a rupee or stolen a sheet to satisfy an urgent need. For the judge and the average offender to belong to the same class means a fundamental change in social structure, as indeed every great reform does. But even apart from and in anticipation of that, something could certainly be done.

It was Bernard Shaw, I think, who suggested that every judge and magistrate, as well as every prison official, should spend a period in prison, living like ordinary prisoners. Only then would they be justified in sentencing people to imprisonment, or to governing them there. The suggestion is an excellent one although it may be difficult to give effect to it. I ventured to suggest it once to the Home Member and the Inspector-General of Prisons of the U.P. Government for their personal adoption, but they did not seem to favour it. At least one well-known prison official, however, has adopted it. This was Thomas Mott Osborne of the famous Sing Sing prison in New York. He trained himself by undergoing a term of voluntary imprisonment and, as a result of this, he introduced later on many remarkable improvements in the social rehabilitation and education of the prisoners.

Such a term of voluntary imprisonment will do a world of good to the bodies and souls of our judges, magistrates and prison officials. It will also give them a greater insight into prison life. But obviously no such voluntary effort can ever approach the real thing. The sting of imprisonment will be absent as well as the peculiarly helpless and broken feeling before the armed and walled power of the State, which a prisoner experiences. Nor will the voluntary prisoner ever have to face bad treatment from the staff. The essence of prison is a psychological background of having been cast off from society like a diseased limb. That will necessarily be absent. But with all these drawbacks the experience will be worthwhile and will help in making the administration of the criminal law more human and beneficial. The great invasions of our prisons by middle-class people during the non-co-operation and civil disobedience movements had indirectly a marked effect. As the prison-goers did not become judges or prison officials the direct effect was little. But a knowledge of prison conditions and a sympathy for the prisoner’s lot became wide-spread, and public opinion and the crusading efforts of some Congressmen bore substantial results.

I do not know whether I am over soft but I do not think I err on the musky and sentimental side. Other people and even many of my close colleagues have considered me rather hard. Mr. C. R. Dass once referred to me at a meeting of the All-India Congress Committee as being “cold-blooded”. Perhaps it all depends on the standard of comparison as well as on the fact that some display their emotions more than others. However that may be, I do hate the idea of punishment and especially “deterrent” punishment and all the suffering, deliberately caused, that it involves. Perhaps it cannot be done away with completely in this present-day world of ours, but it can certainly be minimized, toned down and almost humanized.

At one time I was strongly opposed to the death penalty and, in theory, my opposition still continues. But I have come to realize that there are many things far worse than death, and if the choice had to be made, and I was given it, I would probably accept a death sentence rather than one of imprisonment for life. But I would not like to be hung; I would prefer being shot or guillotined or even electrocuted; most of all other methods I would like to be given, as Socrates was of old, the cup of poison which would send me to sleep from which there was no awaking. This last method seems to me to be by far the most civilized and humane. But in India we favour hangings, and last year the official mind showed us the texture of which it was made by organizing public hangings in Karachi or somewhere else in Sind. This was meant to terrify would-be evil-doers. It turned out to be a huge mela where thousands gathered to witness the ghastly spectacle. I suppose the mentality behind such public exhibitions bears a family resemblance to that which prompted the autos-da-fé of the Spanish Inquisition.

A friend of mine who became a High Court Judge had a ‘crisis of conscience’ when he had first to sentence a man to death. The idea seemed hateful to him. He overcame his repugnance, however, (he had to or else he would not have long continued in his job) and I suppose he soon got used to sending people to the scaffold without turning a hair. He was an exception and I doubt if many others in his position have ever had such scruples. It is probably easier to sentence a man to death than to see the sentence carried out. And yet even sensitive people get used to this painful sight. A young English member of the Indian Civil Service had to attend hangings in the local gaol. At his first hanging, he told me, he was thoroughly sick and felt bad all day. But very soon the sight had no unusual effect on him whatever and he used to go straight from the execution to his breakfast table and have a hearty meal.

I have never seen a death sentence being carried out. In most of the gaols where I have lived as a prisoner executions did not take place, but on three or four occasions there were hangings in my gaol. These took place in a special enclosure, cut off from the rest of the prison, but the whole gaol population knew of it, perhaps because the unlocking of the various barracks and cells took place at a later hour on those mornings. I experienced a peculiar feeling on those days, an ominous stillness and a tendency for people to talk in low voices. It is possible that all this was the product of my own imagination.

And yet with all my repugnance for executions, I feel that some method of eliminating utterly undesirable human beings will have to be adopted and used with discretion. The real objection to the infliction of capital punishment as well as other punishments is of course not so much the resultant suffering of the person punished, as the brutalization of the community that authorizes such punishment, and more particularly of the individuals who carry it out. This is especially noticeable in the case of whipping, which is widely prevalent in India. The official defence for the punishment of whipping is that it is meant for horrible crimes, like rape with violence. In practice it has a much wider range and in 1932 (as was stated in the British House of Commons) five hundred civil disobedience prisoners were whipped. This was the official figure, unofficial jail beatings not being included. These political prisoners were whipped either for purely political offences or for breaches of gaol discipline. No violence or crime was involved. It has now been laid down officially that in serious cases of hunger-strikes in gaol whipping may be resorted to. We thus have it that in the opinion of the British Government in India a hunger-strike or breaches of gaol discipline stand on the same level as rape with violence.

Whipping is usually administered in prisons by some low caste prisoner. No prisoner likes the job but he has little choice in the matter. The higher caste prisoners would in any event refuse to whip, and even the warders are reluctant to do so. A case came to my notice once when a warder was asked to whip. He refused absolutely and was punished for this contumacy. It is interesting to compare the sensitiveness to whipping of the prisoners and warders with that of our judges and prison officials who order it and our Government which authorizes and defends it.

I was reading the other day about the film censorship in Britain. It was stated that one of the grounds for censorship was the avoidance of cruelty scenes. In animal films no kill was to be shown. Films “showing pain or suffering on the part of an animal, whether such pain is caused by accident or intention” are not allowed as these are supposed to have a bad effect on spectators, especially children, and “undermine moral character.”

We also in India have our film censorships and an active Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Unfortunately human beings are not included in the category of animals and so they cannot benefit by the activities of the Society. And our film censorship justifies itself by banning films dealing with “Quetta Earthquake Topical” or “National Congress Scenes” or “Departure of Mahatma Gandhi for the Round Table Conference” and similar dangerous topics.

Sentences of death and whipping impress us and pain us, but, after all, they affect only a very small number of the scores of thousands who are sentenced by our courts. The vast majority of these go to prison, mostly for long periods over which their punishment is spread out. It is a continuing torture, a never-ceasing pain, till mind itself grows dull and the body is blunted to sensation. The criminal type develops, the ugly fruit of our gaols and our criminal law, and there is no fitting him in then with the social machine outside. He is the square peg everywhere, with no roots, no home, suspicious of everybody, being suspected everywhere, till at last he comes back to his only true resting-place, the prison, and takes up again the tin or iron bowl which is his faithful companion there. Do our judges ever trouble to think of cause and effect, of the inevitable consequences of an act or decision? Do they realize that their courts and the prisons are the principal factories for the production and stamping of the criminal type?

In prison one comes to realize more than anywhere else the basic nature of the State; it is the force, the compulsion, the violence of the governing group. “Government”, George Washington is reported to have said, “is not reason, it is not eloquence – it is force! Like fire, it is a dangerous servant and a fearful master.” It is true that civilization has been built up on co-operation and forbearance and mutual collaboration in a thousand ways. But when a crisis comes and the State is afraid of some danger then the superstructure goes or, at any rate, is subordinated to the primary function of the State – self-protection by force and violence. The army, the police, the prison come into greater prominence then, and of the three the prison is perhaps the nakedest form of a State in miniature.

Must the State always be based on force and violence, or will the day come when this element of compulsion is reduced to a minimum and almost fades away? That day, if it ever comes, is still far off. Meanwhile, the violence of the governing group produces the violence of other groups that seek to oust it. It is a vicious circle, violence breeding violence, and on ethical grounds there is little to choose between the two violences. It always seems curious to me how the governing group in a State, basing itself on an extremity of violence, objects on moral or ethical grounds to the force or violence of others. On practical grounds of self-protection they have reason to object but why drag in morality and ethics? State violence is preferable to private violence in many ways, for one major violence is far better than numerous petty private violences. State violence is also likely to be a more or less ordered violence and thus preferable to the disorderly violence of private groups and individuals, for even in violence order is better than disorder, except that this makes the State more efficient in its violence and powers of compulsion. But when a State goes off the rails completely and begins to indulge in disorderly violence, then indeed it is a terrible thing, and no private or individual effort can compete with it in horror and brutality.

“You must live in a chaos if you would give birth to a dancing star,” says Nietzsche. Must it be so? Is there no other way? The old difficulty of the humanist is ever cropping up, his disgust at force and violence and cruelty, and yet his inability to overcome these by merely standing by and looking on. That is the recurring theme of Ernst Toller’s plays:

“The sword, as ever, is a shift of fools

To hide their folly.”

“By force, the smoky torch of violence.

We shall not find the way.”

Yet force and violence reign triumphant today everywhere. Only in our country has a noble effort been made to combat them by means other than those of force. The inspiration of that effort, and of the leader who lifted us out of our petty selves by his matchless purity of outlook, still remains, though the ultimate outcome be shrouded in darkness.

But these are big questions beyond the power even of judges. We may not perhaps be able to find an answer to them in our time, or, finding an answer, be unable to impress it on wayward humanity. Meanwhile, the smaller questions and problems pursue us and we cannot ignore them. We come back to the job of the judge and the prison governor and we can say this, at least, with certainty: that the deliberate infliction of punishment or torture of the mind or body is not the way to reform anyone, that (though this may break or twist the victim) it will not mend him, that it is much more likely to brutalize and deform him who inflicts it. For the inevitable effect of cruelty and torture is to degrade both the sufferer and the person who causes the suffering.

Almora District Jail 1-9-1935.

The Modern Review was founded in 1907 by Ramananda Chatterjee, who also founded and edited the Bengali magazine, Prabasi and the Hindi magazine, Vishal Bharat. All three periodicals can be best described as journals of opinion.

The Modern Review published essays by practically every well-known leader of the Indian nationalist movement, along with the views of foreign sympathisers. It also carried rousing editorials from Ramananda Babu himself. After his demise in 1943, his son Kedarnath carried on the good work until he passed away in 1965. The magazine also published fiction, book and art reviews, travelogues, etc., including essays by pioneers like the anthropologist Verrier Elwin and historian, Jadunath Sarkar.

Ramananda Babu allowed his contributors to present every shade of opinion and argue their cases, while ensuring the magazine itself maintained an impartial editorial stance. He was happy to publish long multi-issue arguments between luminaries like Tagore-Gandhi and Subhas Bose-Sardar Patel about the shape and direction of the nationalist movement. Contemporary opinions about topics such as education, women’s rights, the relations between religions and castes, electoral politics, India’s place in the world, and international relations can be accessed and contextualised by leafing through the archives of this journal of record.

—Devangshu Datta

To read a select anthology of articles, interviews, poetry and fiction published from 1907-1947 in the Modern Review, you can buy‘Patriots, Poets and Prisoners’ here.

Jawaharlal Nehru needs no introduction. He was central to Indian politics both before and after Independence. He was Independent India’s first Prime Minister and went on to hold that position till his death 17 years later. His legacy as a statesman and as architect of an independent India is undeniable. While parts of it are often disputed, it continues to loom large above us all. But Nehru lives on in more than history. His written work – comprising mostly books, articles and letters – are some of the most stellar samples of Indian English writing in the twentieth century. You can read more about him here.

Devangshu Datta is consulting editor and science and technology correspondent at the Business Standard. He is an editor, along with Nilanjana S. Roy and Anikendra Nath Sen of Patriots, Poets and Prisoners.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply