Some of the circumstances will seem strange to a 21st century reader. Some will not.

A lower-caste candidate – a “chamar” (leather-worker) referred to only as “Hari” (short for “Harijan”) – is inducted as a candidate in an Allahabad municipal election in 1936. Although he is an educated and capable man, he loses. Indeed, he stands little chance. A coalition of the bigoted – comprising upper caste Hindus, those offended by this audacious individual from a ‘low’ caste background, those whose economic interests may be affected, etc. – aligns against him.

That scenario would be easily understood by a 21st century social scientist. A similar dynamic to the one that operated in Civil Lines, Allahabad in the United Provinces in 1936, continues to operate today in Civil Lines, Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh. Anybody acquainted with UP politics in 2020 will intuit the prejudices a Dalit candidate would have to confront if he stood for elections in Civil Lines.

What will be unfamiliar is the nuts and bolts of the electoral system during the latter days of the British Raj. Elections began in the 1920s with municipal bodies. The Government of India Act (1935) copy-pasted the British bicameral structure with an Upper Chamber that contained the nominated, and an elected Lower Chamber. Provincial elections occurred in 1936-37 in six provinces.

But the structural elements, such as the demarcation of constituencies and seats, and the lists of eligible voters, were very different in 1936. There were reserved constituencies, for Muslims, Christians, “Europeans”, Sikhs and Scheduled Castes. In these, candidates and voters had to belong to the concerned community. This was supposed to ensure that the interests of various communities were represented. There was a very public argument between Gandhi and Ambedkar on the subject of caste-based reservations for the ‘low’ caste. Ambedkar won.

There were also general seats where anybody could stand, and seek the vote of the eligible voter. But this wasn’t a universal franchise by any means. The right to vote depended on qualifications like ownership of property, payment of income tax, payment of municipal tax, the holding of land, etc. In practice only the creamy layer – perhaps 5 percent of Indians, or even less, had the vote.

It was considered a daring experiment when the new Indian republic decided on universal franchise – giving the vote to every citizen. The General Elections of 1951-52 saw over 170 million voters (India had a population of about 360 million according to the 1951 Census) exercise their right in what was by far, the largest democratic exercise ever undertaken. The voting lasted for almost six months.

The new republic also eliminated the concept of the reserved constituency though it introduced the concept of the reserved seat where only an SC/ST candidate could stand although everybody could vote. Much later, the concept of gender reservation has been introduced at the Panchayat level, where up to one-third of seats are reserved for women candidates.

Does this work better than the old system with reserved seats for specific communities? Perhaps. But it certainly hasn’t led to an elimination of caste bigotry. Indeed, that appears to have been successfully exported, going by the ongoing legal battle between Cisco and the State of California.

—Devangshu Datta

December 3rd – polling day – was approaching and Prayag Dutt, the canvasser, tried to speed up the delivery of the candidate’s cards. “Who is this Hari,” enquired the Brahman elector, an Advocate of the High Court, “and what is his caste?” Prayag Dutt canvassing on behalf of the Harijan candidate replied that the candidate was a Chamar by caste.

Thereupon the Advocate spoke in his persuasive manner: “Why don’t you Chamars stick to the ancestral work of shoe-making? It should pay well. Why do you want to stand for the Municipal Election- what can a Chamar do in the Municipal Corporation?”

Prayag Dutt agreed that shoe-making would be profitable work. But he said: “We pure Chamars would never have given up the shoe trade but for the fact that in this city there are now a number of mongrel Chamars.”

“Who are these mongrel Chamars?” asked the Advocate, and Prayag Dutt replied: “A number of Brahmans, Khatris, and Baniyas have set up shops of imported boots and shoes and are making profits by underselling the hard-working Chamar in the shoe business.”

The Allahabad Municipal Corporation building

The elector felt disconcerted and perhaps in order to get rid of the canvasser expressed his willingness to vote for the Harijan candidate.

The local Congress Committee had decided to help the poor to win a seat during the recent Municipal Election at Allahabad from the Civil Lines, which includes a number of Bastis with hundreds of voters who are for the most part poor manual workers. With its modern roads, which serve the houses of the high and mighty, surrounded by gardens and lit with electricity, the Civil Lines area is a contrast to the Bastis of the poor whose hubs are taxed by the Municipality, which has, however, never shown any anxiety to make a road or provide the poor with water or even oil lamps. During the rains water collects in pits in the dust tracks and little children die by drowning in the very midst of the Bastis.

The nomination of a Harijan candidate from the Civil Lines caused a flutter in the dove-cotes of orthodoxy. While some of the educated and respected middle-class voters took this as a personal affront to their intellectual attainments, others regarded it as a challenge to caste superiority and the sacred principle of private property. The Advocates’ Association sensed the coming danger instinctively and some of the learned fraternity asked the writer to explain why the Congress had dared to nominate a Chamar for a seat from the Civil Lines. A Kashmiri Pandit asserted with vehemence that he would never tolerate a Harijan candidate. His attention was drawn to the fact that caste was immaterial; the candidate was a Kashtkar (farmer), literate and a nationalist and was chosen by the local Congress committee as a straightforward and incorruptible man. Indeed, he was personally known to many as a faithful servant of the late Pandit Motilal Nehru. But the learned Counsel was adamant. He said he would be prepared to vote for a Chamar or even a Mehtar if the latter were “reformed” by Islam or Christianity!

The issue was thus side-tracked. It was not one of religion or of caste. It was purely secular. The poor knew where the shoe pinched and it was their right, if they so chose, to elect as a representative from among themselves one who would bring the grievances of the poor and needy before the Municipal Commutes and get them redressed as far as possible. The reactions of the so-called high castes and the intellectuals revealed that they were either unconscious of the sufferings of large numbers of the so-called depressed classes or that they refused to act justly towards masses of the poor born within the fold of Hinduism who were perpetually on the anvil under the blows of a hundred hammers.

The issue involved in Hari’s candidature was thus misinterpreted. Hari’s canvassers included enthusiastic students and some Advocates who had volunteered their services. When they presented his card and appealed to the high-caste voters they found many of them forgot, in their anger, that the candidate was set up by the Congress. One of the Brahman Advocates was amazed that he should have been asked to vote for a Chamar. He tore up the card and threw it in the face of the Advocate canvasser.

At first in the Indian Clubs it was considered a joke, but when the canvassing in favour of Hari, the representative of the working class, became increasingly successful the menace was considered too grave for the high castes to ignore it. The tension ended in a storm of opposition in the Civil Lines against the very idea of the candidature of a Chamar.

Ranjit Sitaram Pandit

In the Civil Lines there are two seats for the Non-Muslim constituency, which is a joint constituency for Europeans and Indians, Hindus, Christians, Parsees and others. With one solitary exception, about nineteen years ago when a Hindu was returned, the Civil Lines area has been represented heretofore only by Europeans, Anglo-Indians or Christians. The Congress Committee had set up a candidate to contest one out of the two seats with the bonafide desire to train the voters among the poor and manual workers to exercise their rights. Two Hindu candidates were in the field this year, besides three Christians, for the two seats. Municipal elections had heretofore evoked no enthusiasm in the Civil Lines, but this was a dangerous departure.

Every house now discussed the pros and cons of this problem and opinion was sharply divided until the orthodox of all kinds combined and determined to reduce the support Hari had already gained by a vigorous campaign of counter canvassing. Single voting for the high-caste candidates was resorted to to secure the defeat of Hari. The substantial support already secured among all classes of voters, including Europeans, Parsees, Professors, Doctors, Advocates, Theosophists, Christians and others was thus neutralised.

The working classes, such as the Kashtkar, the carpenter, the mason, the dhobi, the petty shop-keepers at street corners were easily divided by the agents of the high-castes. The poor lacked organization and their support was undermined, without much difficulty, by methods commonly employed in elections. The orthodox and respectable of all sections had combined to save religion and respectability from the menace of the Harijan. And they won.

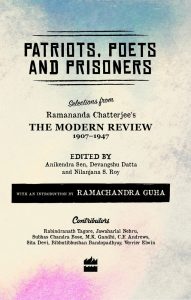

The Modern Review was founded in 1907 by Ramananda Chatterjee, who also founded and edited the Bengali magazine, Prabasi and the Hindi magazine, Vishal Bharat. All three periodicals can be best described as journals of opinion.

The Modern Review published essays by practically every well-known leader of the Indian nationalist movement, along with the views of foreign sympathisers. It also carried rousing editorials from Ramananda Babu himself. After his demise in 1943, his son Kedarnath carried on the good work until he passed away in 1965. The magazine also published fiction, book and art reviews, travelogues, etc., including essays by pioneers like the anthropologist Verrier Elwin and historian, Jadunath Sarkar

Ramananda Babu allowed his contributors to present every shade of opinion and argue their cases, while ensuring the magazine itself maintained an impartial editorial stance. He was happy to publish long multi-issue arguments between luminaries like Tagore-Gandhi and Subhas Bose-Sardar Patel about the shape and direction of the nationalist movement. Contemporary opinions about topics such as education, women’s rights, the relations between religions and castes, electoral politics, India’s place in the world, and international relations can be accessed and contextualised by leafing through the archives of this journal of record.

—Devangshu Datta

To read a select anthology of articles, interviews, poetry and fiction published from 1907-1947 in the Modern Review, you can buy‘Patriots, Poets and Prisoners’ here.

Ranjit Sitaram Pandit was an Indian barrister, politician, linguist and scholar. He is one of those near-forgotten individuals who devoted his life to the Indian Freedom Movement (particularly the Non-Cooperation Movement). As a young lawyer with family connections to Mahatma Gandhi, he was building a promising practice in Calcutta when he came into contact with the Nehru family. He ended up marrying Motilal Nehru’s daughter, Swarup aka Vijaya Lakshmi, on the anniversary of the Indian Rebellion of 1857: 10th May, 1921. He moved to Allahabad and started focusing on cases connected to the freedom struggle. He endured multiple stints in prison due to his involvement in the freedom movement. The last such incarceration, in 1944, contributed to an early death at the age of 50. He was in very poor health when he was released and died within a few weeks.

From the early 1920s, Pandit was a contributor to The Modern Review (the founder-editor Ramananda Chatterjee had strong connections to Allahabad and, of course, the journal was Calcutta-based). Anecdotes suggest that it may have been his contributions to the Review that drew Motilal’s attention and led to Pandit being considered a suitable boy. Also, that it was only after reading an article by Pandit in the Review that Swarup met him for the first time, and agreed to marry him. He is also remembered for his English translations of Sanskrit texts such as Mudrarakshasa, Rtusamhara and Rajatarangini.

Devangshu Datta is consulting editor and science and technology correspondent at the Business Standard. He is an editor, along with Nilanjana S. Roy and Anikendra Nath Sen of Patriots, Poets and Prisoners.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply