On the eve of the counting and declaration of votes for the Bihar state assembly elections of 2020 as well as on the day itself, one would anticipate that much of the conversation and analysis will revolve around caste politics in Bihar, particularly in light of the political alliance led by Tejashwi Yadav, Lalu Prasad Yadav’s son, being one of two contenders for the Chief Ministership. Whenever there is talk of the history of ‘backward’ and ‘lower’ caste movements in Bihar, particularly in the English media and social media discourse, then such conversations are wont to extend to the rise of Lalu Prasad Yadav in the nineties, with a cursory mention of Karpoori Thakur and the ‘JP Movement’, before sinking into a black hole that is glossed over.

It is because of this that we have chosen to present today the paper Caste Politics in Bihar: In Historical Continuum by Rakesh Ankit, which traces the history of caste politics in the state back to the Janeyu Andolan of the 1920s “which saw the Yadavs and other lower castes sanskritising themselves by wearing the Brahmanical thread” and led to violent clashes between “the Yadav, Kurmi and Koeri castes and their upper-caste adversaries”.

From here, Ankit catalogues, meticulously, how caste politics in Bihar has evolved, through state records, news editorials and English as well as Hindi scholarship. Ankit’s paper suggests, in its introduction, that while most English analysis of this subject is more focused, if not obsessed, with the recent decades and the political personalities of figures like Lalu Prasad Yadav and Nitish Kumar, the relevant Hindi literature may be credited for possessing greater depth as well as covering a more sweeping expanse of time. He cites Satta ke Sutradhar and Bihar: Rajniti ka Apraadhikaran by Vikas Kumar Jha, and Bihar mein Samajik Parivartan ke Kuch Aayaam, Swarg par Dhawa: Bihar mein Dalit Aandolan 1912-2000 and Bahi Dhaar Triveni Sangh Ki: Bihar mein Samajik Nyaya ka Pehla Sangharsh, by Prasanna Kumar Chaudhary and Shrikant, as examples.

Alongside the 1920s Janeu movement – “the first modern milestone on the long road to mobility” – which paved the path for Yadavs (the most numerous in Bihar who – F. G. Bailey suggests – after the acquisition of wealth and land, saw sanskritization as a way to raise their position in the social order), Kurmis and Koeris, arose the Momin movement which “challenged the dominance of Syeds, Sheikhs and Pathans”. Ankit points to the domination of “caste orientation”, rather than “class orientation” during this period that even “fed a clash between the upper elite dominated national freedom movement and the social movement of agricultural communities and backward castes”.

The latter movement found expression in bodies like the Kisan Sabha, the Yadav Mahasabha, the Momin Conference and the Triveni Sangh. Ankit calls Triveni Sangh, born in 1933, “the first step to consolidate and produce a comprehensive political ideology for the ‘backwards’ out of their various caste-based legends and myths” and “the first attempt to apply independent political pressure and form an autonomous political party in opposition to the indifference of Congress to upper-caste domination”.

Ankit points out how not a single person belonging to the ‘lower’ castes was a member of the Bihar Pradesh Congress Committee between 1934 and 1946. He also writes: “Brahmans, Rajputs, Bhumihars and Kayasthas commanded over 40% of Congress legislators from 1952 to 1962 and controlled ‘vote-banks’ of the Scheduled Castes and the Muslims.” While the Bihar Land Reforms Act of 1950 produced a “new class of people” from among “occupancy tenants” which affected the traditional social pyramid, this led mostly to patronage networks and caste alliances, with the reins still in the hands of the ‘upper’ castes.

Ankit then describes how the Socialists, having broken away from the Congress in 1948, decided to target the “backward caste agricultural groups” to establish their political base. Ram Manohar Lohia, who led this charge, gave the slogan “pichhda pave sau mein saath [60% benefits to the backwards/downtrodden] / Socialists ne bandhi gaanth [Socialists have given their pledge]” which was popularised by Karpoori Thakur, “the emerging Socialist leader from the ‘lower’ Shudra nai or barber caste”.

Ankit goes on to break up the happenings of the politically volatile sixties, seventies and eighties into key dates, events, numbers in the Lok Sabha and Bihar Vidhan Sabha, commentary from the papers and journals of the times as well as scholarly interpretation in hindsight— with a focus on caste politics in Bihar. Here is a staccato summary.

1965. The Socialists led “the largest post-independence popular movement in Bihar” on the issues of “fee-increase in educational institutions, food crises, inflation and the corruption of the Congress government”. 1966. The devaluation of the Rupee. Unprecedented inflation. Famine and lawlessness in Bihar. A new, post-independence generation was coming of age and increasingly disillusioned with the Congress. 1967. The first non-Congress government in Bihar, drawn from different parties. In national elections the number of Congress Scheduled Caste MPs is reduced to more than half of the reserved seats (23/45) for the first time, with 13 of the remaining going to Socialists and Communists. 1968. The Samvid Sarkar (led by Mahamaya Prasad Sinha and Karpoori Thakur) in Bihar falls and is followed by ministries of B. P. Mandal (Samyukta Socialist Party) – “the first person from the Backward Classes to become Chief Minister” and B. P. Shastri (Congress) – “the first person from the Scheduled Castes to become Chief Minister”. 1969. Mid-term elections indicate Scheduled Castes are continuing to move away from the Congress. The number of Congress Scheduled Caste MPs is further reduced to 15.

In the four years after 1967 “Bihar had five chief Ministers (CMs) from the Backward Castes, two Scheduled Caste CMs”. “However,” writes Ankit. “The accessions of these ‘backward caste/scheduled caste ministers’ had been the result of political compromise and did not alter the social vantage.” An exception was Karpoori Thakur’s decision, as Education Minister, to abolish English from school and college curriculum as well as its requirement in higher education institutes, which “led to a dramatic change in the social composition of institutes of higher education, with an influx of students from rural areas and Backward Castes, and a rise of the ‘forward among the backwards’ (Yadavs, Kurmis, Koeris)”.

In the elections held in 1972, after the Bangladesh War, the Congress recovered in Bihar. Also in the early seventies, the Naxalite movement gathered support in Bihar, where it “continued till about 1976, even leading the Harijans of the Patna area”. This culminated in the early eighties in “a Naxalite Belt” in Bhojpur, Patna, Gaya and Aurangabad.

But the watershed moment was to be the 1974 JP (Jayaprakash Narayan) movement, where “the seeds of the politics of the 1990s were sown” and which produced “almost all of the later political leaders of the 1990s”. “Bihar,” writes Ankit, “Had become the battlefield of the largest nation-wide student movement against Indira Gandhi’s rule, led by the Bihar Chhatra Sangharsh Samiti, fed by popular alienation among the urban middle classes against the Congress, and supported by the student fronts of Jan Sangh and Samyukta Socialist Party.”

The movement addressed dissatisfaction on a gamut of micro and macro issues: galloping inflation, shortage of essentials, unemployment, economic stagnation, student union rights and representation, and outrage against political murders, prevalent in Bihar from the early 1970s. Writes Ankit: “Despite not being expressly centred on the social questions of caste, this movement provided a boost to the process of the shifting of power and proved to be a training ground for the new breed of leaders. Just as the older generation of leaders had the reference of the struggle for ‘first independence’; the new leaders now had the reference of the ‘second freedom’.”

1977. In the assembly and national elections after the JP Movement and Indira Gandhi’s Emergency, Congress won no Lok Sabha seats from Bihar and only 57 out of 324 seats in the state assembly. However, out of these 57, “Yadavs for the first time headed the list with 10, edging out the Brahmans (9), followed by the Rajputs (7), Bhumihars (6) and Koeris (4) and Kurmis (2)”. In Bihar, Karpoori Thakur formed the Janata Ministry as Chief Minister.

1978. Thakur implements 25% reservation for the Other Backward Classes in government services and decides to hold Panchayat elections which breaks the dominance of the upper-castes in local government. 1979. Thakur’s government is brought down and Ram Sunder Das replaces him with more than 50% ‘upper’ caste ministers in his cabinet. 1980. Indira Gandhi, back in power, dismisses Das’s government and Congress comes back to power in Bihar with 167 seats and 34.17% of the votes.

Throughout the eighties the Congress continued to install ‘upper’ caste CMs: three Brahmins and two Thakurs. During this period, Ankit writes, “the squabbling and short-lived Janata government and the sympathy factor after Mrs. Gandhi’s assassination had overshadowed the question of empowerment of the backwards. Therefore, in this period in the legislative assembly, the representation of the backwards remained steady without being spectacular. But, by the 1990 election, backward empowerment had become the only question.”

The 1980s witnessed a meteoric rise in political violence: “violent incidents increased from 260 in 1977 to 617 in 1984, nearly 100 people were killed in the 1985 election, compared with 34 in 1977, including 4 candidates”. Also, the period between 1972 and 1990 saw a rise of armed groups – led by rebels like Mohan Bind (Kaimur region) and Kailash Mandal (Diayara) – targeting the dominance of the upper castes. Between 1988 and 1989, Bihar saw the rise of caste armies like the Lorik Sena (Bhumihars), the Kunwar Sena (Rajputs), the Lal Sena (landless labourers) and the “Naxalite parallel government” in parts of the state.

Ankit quotes from Atul Kohli’s Democracy and Discontent: India’s growing crisis of governability: “The ‘turmoil in Bihar’ was seen as ‘a product of two related but independent struggles: a political struggle for control of the state pitting the forward castes against the backward castes, and a socio-economic struggle of the landless lower castes against the land owning forward and backward castes’.”

It was in such circumstances, after Karpoori Thakur’s removal from the post of leader of opposition, that Lalu Prasad Yadav filled that position and then the position of Chief Minister of Bihar, which he was to hold for 15 years. Ankit also chronicles, with insightful observations and citations, the rise and fall of Lalu Prasad Yadav (and a juxtaposition of him with Nitish Kumar and what he is seen to stand for), a story of sweeping change as well as great disappointment, that is better known. But it is essential to understand the historical context in which he emerged— a context in which he continues to remain relevant.

To borrow from the paper’s quoting of the poet Nagarjuna: “The decline of Bihar is not a story of yesterday. Actually, history remains invisible to the common people, therefore they start losing hope.”

Movements for social change in Bihar have endured for longer than popularly perceived and their ‘changing contours’ require a historical narrative as well as an ethnographic analysis. Personified by Lalu Prasad Yadav since 1990, their electoral emergence were earlier regarded as representing a ‘new phase’. Lately, it has been proffered as the product of a ‘state formation that produced structures of power and identity within which a caste-based politics democratically captured the state in order to systematically weaken it’. In India, where caste remains omnipresent and omnipotent, ‘interrogating’ it has dominantly been anthropological and sociological, the Republic of Bihar included. Old accounts of caste in Bihar politics were framed in binaries of social stagnation or economic growth, while newer works juxtapose the categories of democracy and development. In the writings of Harry Blair on Bihar, spanning from early-1970s to 1990s, one can see the entire gamut. Starting from talking about caste as a ‘differential mobiliser’ to tracking the consequent ‘social change’ and studying contemporary political behaviour of castes to establishing their electoral support, Blair produced a corpus on the intersection of caste and politics and called it Bihariana. In the last decade, land, religion, conflict management, government transfers and the Naxal struggle have provided various entry-points into Bihar’s present political pathologies. Simultaneously, Lalu Prasad Yadav and, his successor, Nitish Kumar have seen books written on them in attempts to understand the state’s unmaking and making through their making and remaking, respectively.

On the other hand, when one turns towards the existing relevant literature in Hindi, one finds works, singular in their scope, intense in their content and sweeping in their treatment of time. Vikas Kumar Jha wrote an exhaustive volume on the post Independence politics of Bihar titled Satta ke Sutradhar (‘The Narrators/Protagonists of Power’, Delhi: D. K. Publishers, 1996). His other book, Bihar: Rajniti ka Apraadhikaran (‘Criminalisation of Politics in Bihar’, Delhi: D. K. Publishers, 1991) was a smaller volume. Then, there are the three definitive works of Prasanna Kumar Chaudhary and Shrikant: Bihar mein Samajik Parivartan ke Kuch Aayaam (‘Some Aspects of Social Change in Bihar’, New Delhi: Vani Prakashan, 2001), Swarg par Dhawa: Bihar mein Dalit Aandolan 1912-2000 (‘The Dalit Revolution in Bihar 1912-2000’, New Delhi: Vani Prakashan, 2005) and Bahi Dhaar Triveni Sangh Ki: Bihar mein Samajik Nyaya ka Pehla Sangharsh (‘Triveni Sangh: The First Institutional Struggle for Social Justice in Bihar’, Patna: Loktantra Prakashan, 1998), respectively.

Following in their wake and drawing upon state archives and provincial newspapers, particularly The Indian Nation and The Searchlight, this article attempts to frame a rather known story in a longer context. At the heart of the caste ‘politics’ from 1990 lay the caste ‘structure’ of old – ‘local relations of dominance and subordination’ – that led to a ‘“territorial democracy” of caste empowerment’. Bihar politics has often been characterised by fragile institutions of liberal modernity, indeterminate political personalities, populist discourse, corruption and criminal activities. It arguably began with ‘the British never manage [ing] to establish more than a “Limited Raj”’. ‘Institutional decay’ in Bihar emerged with the two-decade rule of the Indian National Congress after the transfer of power (1947-67), was exacerbated by the crises, excesses and emergency of the following decade (1967-77) as well as the populist response to it led by Jayaprakash Narayan (in 1974-75), and arrived at a critical point with the subsequent widening of social and religious divides within the north Indian society (1986-89). At the turn of the 1990s, the question for Bihar was the age-old one: does it ‘need a society derived from political power or politics derived from social fabric’? As the Bihar District Gazetteer from 1970 offered:

“The Rajas, the big Zamindars, the Chairman of Local Bodies, Government Pleaders and Public Prosecutors mattered most. The businessman got scant notice and the common man was seldom thought of… The middle classes sponsored many social and educational institutions.The caste played a great role in society.”

In Francine Frankel’s vivid words, in Bihar, ‘Brahmins, Bhumihars and Rajputs held sway over society for at least one thousand years’ until challenged by the ‘Upper Shudras, the Yadavs, Kurmis and Koeris’. Among Muslims, the highest ranked were ‘Ashrafs, including Saiyads, Sheikhs and Pathans – landowning classes’ – followed by the Razil or ‘labouring people’. Together with each other and the Kayasths, these groups formed the ‘respectable’ people against the rest, ‘from the Ahirs, the [Momins]… to the Chamars, Julahas…’ Politically, Bihar Kayastha Provincial Sabha (1889), Bihar Landholders Association, Bihar Provincial Muslim League (1908) and Gopajatiya Sabha (1909), and later, Bihar Pradesh Congress Committee, All-India Yadav Mahasabha (1923) and Bihar Pradesh Kisan Sabha (1929), were vehicles of these forces.

The corresponding economic matrix was headed by the landlord and followed by his tenants, and therein emerged a four-fold churning of/by: (a) social categorisation, (b) agrarian distress, (c) socio-religious reform and (d) national freedom movement. An undertow of caste mobilisation and organisation, propped up each of these. Colonialism gave it a new character by consecrating the old and contributing to the new identities but this too was an intervention, and not an invention, by the Raj and thus has long outlasted it. Then, there was the national freedom movement, which launched, intensified and/or suppressed regional, social movements. While it cohered the elites, it did not determine, nor desire, a social reconstruction and entrenched a caste politics of ‘exclusion’.

Against this backdrop, the process of backward or lower-caste empowerment began with the Janeyu Andolan, which saw the Yadavs and other lower castes sanskritising themselves by wearing the Brahmanical thread, through the early years of the 1920s. This led to counter-measures by the Brahmans and there were violent as well non-violent encounters between peasants of the Yadav, Kurmi and Koeri castes and their upper-caste adversaries. The Janeyu Movement reached its apogee between 1921 and 1925. This was the first modern milestone on the long road to mobility. It provided the Yadavs with a social-cultural legitimacy, which paved a political path. Yadavs, also known as Goalas and Ahirs, were/are the most numerous caste in Bihar. They were ‘cultivators of all kinds’ and also ‘herdsmen and milkmen’. Kurmis and Koeris too were among the ‘great cultivating castes of Bihar’. Koeris were also known for being ‘skillful and industrious cultivators’, ‘the best tenants’ and ‘market-gardeners of Bihar’.

During the period of the aforementioned five years both north and south Bihar, excluding Chota Nagpur area, were affected. Confrontations took place in twenty villages of the districts of Patna and Munger of central-south Bihar and Darbhanga and Muzaffarpur in north Bihar. Simultaneously, a Momin movement ‘challenged the dominance of Syeds, Sheikhs and Pathans’. Like ‘other organisations of the oppressed social groups, such as the Kisan Sabha, Yadav Mahasabha, Triveni Sangh etc., the Momin Conference also emerged mainly from Bihar’. M. N. Srinivas, relying on the Census of the India Report for 1921, referred to the violent reaction of upper-caste men in north Bihar against the Yadavs’ attempts at sanskritisation. The Census Reports ascribe the attempt of lower castes at social uplift to the efforts of their respective caste sabhas. They emphasise the socio-economic oppression of the lower-caste peasants in general and the Yadavs in particular by the landlords of upper-castes as the root cause for violent upsurge. F. G. Bailey observed:

“The acquisition of substantial wealth by the two dominant castes led to investment in land, for land is still the best investment and without it a man has no prestige. They followed this by Sanskritizing their customs and rituals in order to raise their position in the caste system.”

Bihar in this period was economically barely developed barring the southern, industrial region of Jamshedpur, and agriculture remained primitive. Society was in the pre capitalist stage and class interests did not achieve full economic articulation. Economic elements were inextricably linked to socio-political and cultural-religious factors. Action against socio-economic oppression in Bihar was thus imbricated with the promotion of caste interests. Historian Ramakrishna Mukherjee, among others, has shown this contradiction between upper castes/class and lower caste/class. It was the ‘caste orientation and not class orientation that dominated at the manifest level’, and, fed a clash between the upper elite dominated national freedom movement and the social movement of agricultural communities and backward castes. In Bihar, like elsewhere but especially so, the defaulting, exclusive upper-middle classes/elites did not engage with the socio-political and cultural-economic aspirations of the lower castes and ex communicated their attempts to politicise these.

Against this backdrop of ‘planter-zamindar-government alliance’, confronted by Gandhi in Champaran in 1917, Swami Vidyanand in Darbhanga in 1919 and Sahajanand Saraswati in 1930s, it is instructive to remember the first consolidated political attempt at social equality made by the Yadavs, Kurmis and Koeris, the three landed castes among backward castes, seventy years ago. This was the Triveni Sangh, the organisational result of the Janeyu movement. Born on 30 May 1933 in Kargahar village of Shahabad district, Triveni Sangh was the first step to consolidate and produce a comprehensive political ideology for the backwards out of their various caste-based legends and myths. The Congress, which had been afflicted by caste factionalism and manoeuvring since the early 1920s, was proving inadequate in reflecting the growing ambitions of the backward castes and lower middle classes. Triveni Sangh was the first attempt to apply independent political pressure and form an autonomous political party in opposition to the indifference of Congress to upper-caste domination.

It should have provoked introspection in the Congress as to why those castes that formed the largest proportion of the state’s population and their representatives were absent from its leadership. But, as the tallest Congressman in Bihar, Rajendra Prasad, wrote, ‘orthodoxy reigned supreme among the Hindus’. Given the way the Kayasths politically dominated the Congress, the Bhumihars and the Brahmins dominated organisations like the Kisan Sabha, it was inevitable for an organisation to emerge, which would confront and cast a long shadow. After all, not one person of the lower castes was a member of the Bihar Pradesh Congress Committee between 1934 and 1946.

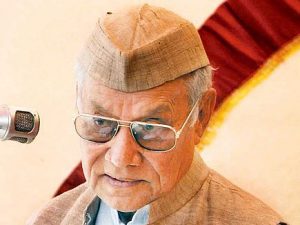

K.B. Sahay

That though did not deter the launch of the ‘bakasht struggles’ of the Kisan Sabha, with its estimated 250,000 members, and spurred the formation of Bihar Provincial Khet Mazdoor Sabha by Jagjivan Ram in 1937. Thirty-five years later, analysing the poll prospects of different parties before the elections of 1972, an editorial in The Searchlight wrote: ‘Caste, like sex, is the Freudian instinct in Bihar where everything – particularly politics – veers around it’. Thus, much before Lalu Prasad Yadav, Congressmen like S. K. Singh (1887-1961), M. P. Sinha (1900-71), A. N. Sinha (1887-1957) and K. B. Sahay (1898-1974) had been great purveyors of caste identity politics. The decades from the 1930s to 1960s saw deep factionalism and fragmentation within Congress. Its ‘leadership’ was a ‘function of coalescence brought in a musical-chair game amongst the caste-based factions of the party’. Brahmans, Rajputs, Bhumihars and Kayasthas commanded over 40% of Congress legislators from 1952 to 1962 and controlled ‘vote- banks’ of the Scheduled Castes and the Muslims, ‘inclined to be docile [and] appendages’ (quotes from Francine Frankel’s Caste, Land and Dominance in Bihar: Breakdown of the Brahmanical Social Order). Bihar State Backward Classes Federation (1947), its Hindi weekly, Pichara-Varg, universal adult suffrage (1950, 1952), the Government of India’s Backward Classes Commission (1953), with its report (1955) were the key milestones of the politics of caste, at this time. The stymied Bihar Land Reforms Act (1950) did produce a ‘new class of people’ from among the occupancy tenants and would contribute in giving a ‘death blow to the traditional social pyramid’, albeit by developing a ‘patronage network’, linking a ‘caste alliance’.

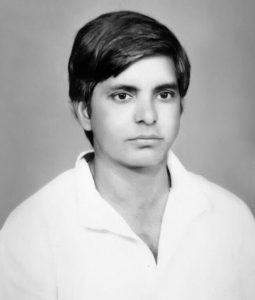

Jayaprakash Narayan

The emergence of Socialists as the major opposition power in Bihar occurred against this aforementioned ‘cultural crisis’, existing within and emanating from the Congress. There emerged an ideology, which significantly influenced the emerging middle-classes among the backward castes and their rise as a political power. Subsequently, almost all parties reflected a socialist and populist creed. However, to adapt George Bernard Shaw, this ‘social revolution’ in Bihar, ‘did not end tyranny; it merely shifted the burden to other shoulders’. After separating from the Congress in 1948, the Socialists had to face a two-fold struggle of establishing their separate political and ideological identity as well as consolidating their social base. This was met by the uncompromising Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia (1910-67) and the malleable Jayaprakash Narayan (1902-79), in their own ways, after the 1952 electoral debacle and the consequent difficult years. Within his ‘New Socialism’, Lohia retained Liberal Populism and Gandhism but replaced Marxism with his own understanding (since called ‘Lohia-ism’), which linked the continuing caste and social-assertion movements of the backwards with the socialists. In so doing he recognised a home-truth of Bihar Politics, as The Indian Nation re-affirmed fifty years ago: ‘The general impression is that almost everyone is casteist’.

A.N. Sinha

To build a powerful opposition to Congress, Lohia decided to turn to the backward caste agricultural groups as his political base. The rising groups within the backward castes were also looking for a party that could represent their political ambitions. It was here that Lohia’s slogan, ‘pichhda pave sau mein saath’ [‘60% benefits to the backwards/downtrodden’], was popularised by Karpoori Thakur, the emerging Socialist leader from the lower Shudra nai or barber caste: ‘Socialists ne bandhi gaanth’ [Socialists have given their pledge]. Lohia also launched the comprehensive idea of ‘sapt-kranti’ (seven-fold revolution) bringing together the issues of social exploitation with racial, national, sexual questions and linking them with the imagery triad of ‘vote-spade-jail’ thereby attempting to consolidate the anti-Congress forces. Another initiative was the anti-English emphasis of the Socialist’s language policy, which emotionally resonated with the youth and the students of the north Indian backward-agricultural castes. In August 1965, the Socialists led the largest post-independence popular movement in Bihar on the issues of fee-increase in educational institutions, food crises, inflation and the corruption of the Congress government. 1966 followed with the devaluation of rupee leading to an unprecedented inflation. Bihar suffered famine and lawlessness. A new, post-independence generation was coming into its own and decidedly breaking away from the Congress, being thwarted by the vested status quo of the Grand Old Party.

Ram Manohar Lohia

The 1967 elections were held against this background ending Congress’ two-decade long electoral domination and a ‘non-Congress government was formed with tremendous goodwill… drawn from [different] political parties’. The number of Congress’ Scheduled Caste MPs, for the first time, was reduced to about half of the reserved seats for them (23/45). The rest went to different political parties including 13 to Socialists and Communists. After the fall of this Samvid Sarkar (SVD ministry) of Mahamaya Prasad Sinha and Karpoori Thakur, followed by the ministries of B. P. Mandal – ‘the first person from the Backward Classes to become Chief Minister’ and B. P. Shastri – the first person from the Scheduled Castes to become Chief Minister – mid-term elections were held in 1969 and the Scheduled Castes continued to move away from the Congress. The number of their MPs in Congress (15) was now equal to those in Samyukta Socialist Party (13) and Praja Socialist Party (2) combined. Later, the pro-Janata wave of 1977 saw the Congress being reduced to 2/45 in the reserved constituencies.

However, in the elections held after the Bangladesh war in 1972 and after the fall of the Janata experiment in 1980, the Congress recovered. Similarly, after the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in October 1984, the sympathy vote saw the figures regaining the heights of the 1950s in the 1985 elections. But, by/through the 1990s, Janata Dal/Rashtriya Janata Dal replaced the Congress in the vanguard of the political movement of the backward groups. Thus, the importance of that 1967 elections in Bihar’s socio-political history can be gauged from the fact that it was that particular election, which ‘brought in a coalition [politics] setting urban disillusionment/apathy and rural splinter-ism/assertion’. Albeit, in the short-term, as The Indian Nation opined in 1968: ‘There is one word to describe the present state of Bihar politics – ramshackle’. By now, the major demands of the Backward and Dalit movements, removal of untouchability and reservation in government jobs, had been given a constitutional framework by the 1950s-60s, though their execution had been far from satisfactory. Nevertheless, since independence, a middle class among intermediate castes had emerged. Writing prophetically, The Indian Nation warned the Congress in early 1972 that:

“Politically conscious backward castes, classes [and] tribals are struggling for recognition and representation and Congress’ drive for ‘social justice’ must embrace them. The coalition politics from ’67 to ’72 was an unstable disillusionary phase and Mrs. Indira Gandhi’s golden period of ’71- 72 has brought back stability in Bihar but complex social undercurrents should not be neglected.”

The 1974 JP movement was to be the watershed, which decisively turned this class away from the Congress. As well-known, almost all of the later political leaders of the 1990s were a product of this movement. The Naxalite Movement, on the other hand, emerged from the ideological struggle and splits within the Indian Communist Movement. By early 1970s, the Naxalite Movement was losing support in the rest of the country but in Bihar, it continued till about 1976, even leading ‘the Harijans of the Patna area’. By the early 1980s, a ‘Naxalite Belt’ would emerge in Bhojpur, Patna, Gaya and Aurangabad. Later, however, they would have to contend with Lalu Prasad Yadav, who would boast:

“I have proven that ballot boxes are more powerful than machine guns. Votes can decide whether a man will be in the dust or riding in an airplane. I am a true Naxalite [militant, communist revolutionary], from birth, a democratic Naxalite.”

His revolution would remain ‘incomplete’, by getting reframed as ‘Yadav Raj’. Even so, every failed revolution has its socio-political consequences, especially a democratisation of socio-political space that enhances subsequent mobilisation on the larger issues of public interest.

The period from 1967 saw the social movement of the Backwards reaching the corridors of power for the first time. In the next four years, Bihar had five chief Ministers (CMs) from the Backward Castes, two Scheduled Caste CMs, as well as the only Backward Caste minister from Congress. Between 1967 and 1972, Bihar had nine governments, including ones that lasted as briefly as for three days and nine days. However, the accessions of these ‘backward caste/scheduled caste ministers’ had been the result of political compromise and did not alter the social vantage. The single most significant piece of social legislation for the Backward Castes, in this period, was the decision of Karpoori Thakur, as Education Minister in the Samvid Sarkar (1967-69), to abolish English education from school and college curriculum as well as to abolish its requirement in institutes of higher education. This led to a dramatic change in the social composition of institutes of higher education, with an influx of students from rural areas and Backward Castes, and a rise of the ‘forward among the backwards’ (Yadavas, Kurmis, Koeris). In contrast, Congress’ cohort of landed, educated and contracted elite headed by men like Harihar Singh, L. N. Mishra, Daroga Prasad Rai, Kedar Pandey and Abdul Ghafoor did not alter in that ‘the majority both before and after the 1969 split, remained with the Forwards and the Upper Backwards’.

A JP Movement procession

Twenty years before Lalu Prasad Yadav polarised Bihar’s electoral scene, Jayaprakash Narayan (JP) had already articulated the cardinal aphorism of Bihar politics. In 1974, he had said, ‘Caste is the biggest political party in Bihar’. By now, Bihar had become the battlefield of the largest nation-wide student movement against Indira Gandhi’s rule, led by the Bihar Chhatra Sangharsh Samiti, fed by popular alienation among the urban middle classes against the Congress, and supported by the student fronts of Jan Sangh and Samyukta Socialist Party. The Indian Nation had written in January 1974, of ‘back breaking prices, acute shortage of essential commodities, galloping inflation, mounting unemployment and virtual economic stagnation. However, the opposition could not make any substantial gains as they had neither the ability nor the leadership’. Now, helmed by JP, it became a nation-wide popular campaign. Initially, it had an eight-point agenda involving student union rights, provision of vocational education, bank loans for business, unemployment allowance, accommodation and scholarship, effective student representation, inflation, affordable food and study material. The traditional New Year piece of The Indian Nation in 1975 attempted to capture the ambiguity in this period:

“1974 was a year of processions and demonstrations, trials and tribulations, conflicts and confrontations for Bihar. It gave a shock treatment to the party in power, which had been fleecing the people. Significantly, the agitation took wings and spread over other parts of the country posing the first-ever serious threat to the party in power. Whether that would strengthen or weaken the country is a matter of opinion.”

Among other burning issues, the inflation rate reached 30% by August 1974 and there was outrage against the political murders which had become prevalent in Bihar from early 1970s, viz., those of freedom-fighter Suraj Narain Singh on 21 April 1973 and the then-Union Railway Minister Lalit Narayan Mishra on 2 February 1975. Between 1971 and 1981, Bihar saw ‘an average of 178 Ordinances compared to 15 Legislations’ and between 1966-7 and 1977-8, the state’s growth rate was 2.5%. After 34 years of planning, Bihar was ‘at the bottom’. Despite not being expressly centred on the social questions of caste, this movement provided a boost to the process of the shifting of power and proved to be a training ground for the new breed of leaders. Just as the older generation of leaders had the reference of the struggle for ‘first independence’; the new leaders now had the reference of the ‘second freedom’. However, ‘the tragedy of 1974’, was pronounced by contemporary commentary as {in The Indian Nation}*,

“…a double whammy: the government failed to protect the people; the opposition failed to give a right direction to the movement, which launched an orgy of violence shaking the conscience of people and nerves of the government. Ideally it should have happened the other way around.”

Nevertheless, the seeds of the politics of the 1990s were sown in this social movement of the 1970s. As the poet Nagarjuna wrote, ‘The decline of Bihar is not a story of yesterday. Actually, [since] history remains invisible to the common people therefore they start losing hope’. The elections of 1977 were a disaster for Congress with no Lok Sabha seats from Bihar and only 57 out of 324 seats in the state assembly. It had been clear for some time that ‘the flabby Congress, deeply involved in power politics, held only a tenuous touch with the masses as a result of its weakened base’. The party managed only a 23.5% share of the vote, an all-time low. But of greater significance is the caste composition of its 57 MLAs. Yadavs for the first time headed the list with 10, edging out the Brahmans (9), followed by the Rajputs (7), Bhumihars (6) and Koeris (4) and Kurmis (2). This was against the backdrop of the 1975-77 ministry of the maithil Brahman, Jagannath Mishra. But, the danger of empty and negative, anti-incumbency politics was not lost on all, amidst the widespread euphoria at the ouster of the Congress party from the corridors of power. The hollowness of the ‘Janata Wave’ was remarked upon thus {in The Indian Nation}*:

“The Janata wave was a natural outcome of the repression let loose in the country. Emergency had choked the people and, their mute struggle threw the political dictatorship, once they became fully awake and sat up, but beyond that, the JP Janata wave is no more on the move because it could not [be].”

It was not long before disillusionment with the new non-Congress regime set in. Three months into the new government and a sense of helplessness can be detected as The Searchlight declared that ‘as long as narrowness prevails, governments may change, but things will not improve.’ By then, Karpoori Thakur had formed his Janata Ministry on 22 June 1977 and on 9 March 1978 decided to implement the 25% reservation for the Other Backward Classes in government services. The second major decision of the government was to hold Panchayat elections. Held amidst widespread election violence, these broke the traditional dominance of the upper-castes in local government forever. Unsurprisingly, Thakur’s government was brought down in April 1979 and Ram Sunder Das succeeded him and formed a cabinet, which had more than 50% of its ministers from upper castes. Das did not last long either. By January 1980, Indira Gandhi was back in power and she dismissed his ministry on 18 February 1980. The non-Congress forces were divided in the state and Congress came back to power in Bihar with 167 seats and 34.17% of the votes; figures that increased to 196 and 38.62% respectively in 1985. Even the number of Scheduled Caste MLAs rose to respectable figures (24/48 and 33/48), but these should not be construed as indicators of their return to the Congress’ fold. The decade of the 1980s in general and the two years of 1988-9, in particular, with four CMs, witnessed incredible episodes of anarchy and violence, unprecedented misrule and opportunist vote bank politics, led the way for a permanent eclipse of Congress rule in Bihar and made it easier for anti-Congress groups to succeed. Certainly as another editorial in The Indian Nation put it:

“…the schizophrenic Congress [had] made both democratic politics and democratic governance meaningless. But which brand of change? The Jan Sangh brand? The Socialist brand? The Congress (O) brand? A mixture? This question remains unanswered.”

The Congress in the 1980s was still installing upper-caste CMs; three were Brahmins and two Thakurs. The backward groups, meanwhile, continued towards their goal of political representation and power. At the outset of this period in the 1967 elections, there had been 82 Backward Caste MLAs compared to their 133 caste counterparts. By 1989, there were 90 Backward Caste MLAs and their caste adversaries had come down to 118.

During this time, national issues like the Bangladesh war, the emergency and the following election, the squabbling and short-lived Janata government and the sympathy factor after Mrs. Gandhi’s assassination had overshadowed the question of empowerment of the backwards. Therefore, in this period in the legislative assembly, the representation of the backwards remained steady without being spectacular. But, by the 1990 election, backward empowerment had become the only question. This is best illustrated by the ‘political odyssey of Karpoori Thakur after the 1980 elections until his death in 1988’, which saw {Frankel’s Caste, Land and Dominance in Bihar: Breakdown of the Brahmanical Social Order}:

“…the emergence of two contradictory potentialities in the consolidation of larger political identities within the framework of the division between the Backward Classes and Forward Castes. Over all, the larger caste categories, i.e., forward and backward, were strengthened as the basic units of political identity. At the same time, within the Backward Classes, divisions emerged along class lines which simultaneously created an attrition in ‘Backward’ strength, and opened up the potentiality of a broader coalition of the poor.”

Moreover, between 1972 and 1990, there was a rise of armed rebel groups, which played a major part in breaking the dominance of the upper castes. Two prominent rebel leaders of this period were Mohan Bind in the Kaimur region and Kailash Mandal in Diayara area. The Hindustan Weekly noted in its 22 December 1991 issue that, ‘The criminalisation of politics and the politicisation of criminals have turned Bihar into the largest arena of political violence’. The Hindustan Times wrote on 10 January 1992 that, ‘Violence has become the way of life in Bihar. Bihar has become the test-tube of the ironies of India’. Between 1980 and 1986, ‘there had been more political murders in Bihar than in Punjab’, resulting in “warlordism”/“second serfdom”, while resulting from ‘decreasing effectiveness of government and the erosion of established patterns of domination in Bihar’s predominantly agrarian society’.

The ‘turmoil in Bihar’ was seen as ‘a product of two related but independent struggles: a political struggle for control of the state pitting the forward castes against the backward castes, and a socio-economic struggle of the landless lower castes against the land owning forward and backward castes’. The ‘always factionalised’ political elite of Bihar – whether Brahmans, Kayasths, Bhumihars, Rajputs or Yadavs, Koeris and Kurmis – always sought ‘a correlation among high status, landownership and political power’. This superbly summed ‘circulation of elites’ thrived on ‘co-option’, starting with the ‘middle peasantry’. By late-1980s, government ineffectiveness, party disarray and power conflict that had been increasing since 1967, was completed by a going together of ‘ballot and bullet’. This ‘democracy by gun’ saw the anti-Indira rebellion, the emergency, Jagannath Mishra’s ‘dark period’ – violent incidents increased from 260 in 1977 to 617 in 1984, nearly 100 people were killed in the 1985 election, compared with 34 in 1977, including 4 candidates – and Rajputs, Bhumihars and Kayasths move away from the Congress.

In the 1980s, ‘professionalism of the police [was] snuffed out by political interference [and] personalism’. And among personalities and private armies, ‘both politically and social, Karpoori Thakur symbolised a new phase in Bihar’s politics: the simultaneous consolidation of an alternative to Congress and the political rise of the backward castes’ – one of Harry Blair’s ‘rising kulaks’ {‘kulak’ is a term earlier used to describe peasants owning over 8 hectares of land during the last days of the Russian empire}. While often seen as personifying ‘the organisation of the poor in a double assault on the caste system and the class structure’, ‘it is important to note that Thakur did not win the 1977 poll solely or even mostly on the basis of his backward leadership; rather it was anti-Congress sentiment’. Karpoori Thakur himself acknowledged that ‘the main enemy was not the forward castes but the Congress party’. And yet, between 1988 and 1989, Bihar had four Brahman chief ministers, under whose ineffectual-ism rose caste armies like the Lorik Sena (Bhumihars), the Kunwar Sena (Rajputs), the Lal Sena (landless labourers) and the “Naxalite parallel government” in parts of the state. This culminated the long history of agrarian struggles in Bihar starting from tenant against landlords and ending with ‘caste-class conflict, police brutality, anarchic conflict, dacoity and criminal violence’. In June 1985, after the so-called Operation Black Panther, the state conceded that ‘Gaya, Aurangabad, Patna, Bhojpur, Rohtas, Munger, Bhagalpur, West and East Champaran were extremist-dominated areas’. No wonder, Jagannath Mishra prophesied in 1986 thus:

“The poor are being neglected by all parties. My own party is losing support among the SC and the ST. The old left has also lost the initiative. Politics, however, does not like a vacuum. Someone will move in.”

Lalu Prasad Yadav

Karpoori Thakur died an untimely death in 1988. By then, ambitious and younger Yadav legislators had already harassed and undermined him to the point of exhaustion, particularly the trinity of Anoop Lal, Srinarayan and Lalu Prasad Yadav. They collaborated with the Speaker of the State Assembly, Shiv Chandra Jha, and had Thakur removed from the post of leader of opposition in a dubious episode. The void left by Karpoori Thakur’s ousting and death was the one which Lalu Prasad Yadav filled with some luck and some help. He assumed the chair of Karpoori Thakur but neither by a unanimous decision nor a majority choice, rather as a compromise candidate. Devi Lal and Sharad Yadav ensured his succession over that of Anup Lal Yadav because, among other reasons, the latter had invited the Brahmin Hemvati Nandan Bahuguna for a meal.

Anup Lal Yadav

The ‘Subaltern Saheb’ began his political life as the Patna University Student Union’s President. He had been a member of the student organisation committee for the 1974 movement. He entered the Lok Sabha in 1977 and Vidhan Sabhas in 1980 and 1985, emerging as the leader of opposition in the latter, in 1988-89. In March 1990, he became the CM despite not contesting the 1990 state elections, having earlier won the Chhapra Lok Sabha seat in the 1989 general elections. The 1989 Lok Sabha and 1990 Vidhan Sabha contests had, as their major issues, the Bofors Scandal, the corruption of Rajiv Gandhi’s Central Government and the permutations forged by Vishwanath Pratap Singh, Devi Lal, Chandrasekhar, the BJP and the Left front. But the strongest undercurrent was that of backward empowerment, encapsulated in the word ‘Mandal’ apart from the ‘Mandir/Kamandal’ politics around Ayodhya Ram-temple. In the 1989 Lok Sabha elections, Janata Dal won 31 seats out of 54 in Bihar and for the first time the number of Backward Caste MPs (18) (Yadavs (11), Kurmis (3), Koeris (4)) was equal to that of upper caste MPs (18). This issue of backward empowerment became even more important in the 1990 Vidhan Sabha elections. Janata Dal emerged victorious with 121 seats leaving behind Congress (71), BJP (39), CPI (23), CPM (6), and JMM (19). Independents also emerged as a major force having won 30 seats.

While in 1990 there were 117 Backward Caste MLAs as against 105 upper caste MLAs, by 1995 there were 161 Backward Caste MLAs as against 56 upper caste MLAs. The composition among the four ‘forward among backward’ castes in these two elections was as follows: 1990: Yadavs (63), Kurmis (18), Banias (16), and Koeris (12); 1995: Yadavs (86), Kurmis (27), Banias (18), and Koeris (13). In the 1991 Lok Sabha elections, there were 24 backward castes MPs in all – Yadavs (13), Kurmis (6), Banias (1) and Koeris (4). These three elections thus saw a conclusive displacement of the upper-castes from the corridors of political power at the hands of the ‘forward among backward’ castes. Analysing the reasons for the defeat of the Congress, The Indian Nation on 2 March and 6 March 1990, identified, ‘Lost goodwill, tarnished image, useless tactics, need for strategy and rebels’. In a hard-hitting editorial on 3 March 1990, The Hindustan Times gave its own verdict:

“The image of its leadership, indefinite postponement of organizational elections, and the arrogance of power on the part of leaders at different levels, factional squabbles and frequent change of CMs by the High Command had done incalculable harm to the party.”

The next seven days had elements of high drama as a row over the Bihar Janata Dal (JD) leadership came out in the open. A keen tussle developed between Ram Sunder Das, Lalu Prasad Yadav and Raghunath Jha. The Sunday edition of 4 March 1990 of The Hindustan Times almost anointed Ram Sunder Das as the next leader and provided the inevitable reason for it:

Ram Sunder Das

“Coalition government in Bihar [is] likely to be headed by Ram Sunder Das who is emerging as a consensus candidate – Mr. Laloo Yadav’s casteist image, his inexperience [and] his attempt to dominate the party with anti-social elements, plus the fact that [the] neighbouring Uttar Pradesh has a Yadav Chief Minister have militated against his serious candidature.”

Lalu Prasad Yadav’s candidature became public only on 5 March 1990 and a serious challenge was mounted over the next two days. He claimed the support of 79 MLAs, mostly those from the old guard of the Lok Dal and the Karpoori Thakur group. The situation was so chaotic that a fourth candidate, Anoop Lal Yadav, announced his bid the next day. Finally in the leadership contest held on 7 March 1990, Lalu Prasad Yadav (58 votes) defeated Ram Sunder Das (54) and Raghunath Jha (14). The victor was the candidate of Devi Lal, Sharad Yadav, Nitish Kumar and Jagdanand camp, while VP Singh and George Fernandes supported Ram Sunder Das and Chandrasekhar had put up Raghunath Jha. On 10 March 1990, the new CM took oath in public at the sprawling Gandhi Maidan. The early image of himself, which he sought to cultivate was that of a ‘leader of the people’ (from The Hindustan Times):

Raghunath Jha

“After a difficult election Laloo Yadav heads an unsteady coalition government, a difficult administration and the greenhorn CM – already being hailed as a “leader of the people” – would have to prove that he has the wherewithal to lead a government, if it has to last long…”

Proving everyone wrong, the incumbent went on to rule Bihar for fifteen years, first and foremost, as an aggressive representative of the drive for backward empowerment. This was his power, but this also provided an intrinsic limit to his power. His ability to ‘connect’ with his social and electoral base and his projection of his personality as his politics were a symbol of pride for them. Even before him, there had been lower or Scheduled Caste CMs, but they had not personified empowerment, barring Karpoori Thakur. Lalu Prasad Yadav, the grassroot Lohiaite, hardened by JP’s Total Revolution, became the prince of social justice and secularism in power. His (from Mohammad Sajjad’s Muslim Politics in Bihar: Changing Contours):

“ …arrest of the Hindu nationalist L.K. Advani and the stopping of his Rath Yatra, firm handling of communal riots, combined with his strong opposition to upper caste hegemony with his characteristic native wit and rustic wisdom, made him tremendously popular among the Muslims (and lower caste Hindus). His electoral equation, Muslim-Yadav, became the famous mantra for his subsequent electoral successes.”

He gave his constituency; the Backwards and Muslims, a hitherto unprecedented sense of belonging and dignity by making them believe that he was their man, ruling on their behalf, for their benefit. He, then, brilliantly employed it by his knowledge of the nature of caste antipathies, social estrangements and constituency arithmetic. Once installed, he went about creating an iconoclastic image of the ‘common Chief Minister’. In the process, neither did he have to nor did he wish to govern Bihar in order to rule it; the twin themes of Mandal and Mandir, giving him an electoral ascendancy that the need for performance fell by the wayside. He emerged as a popular anti-establishment underdog and a rustic messiah. Among the heterogeneous caste/class groups within the Backwards, the economically rich and politically influential Yadavs (the so-called creamy layer) cornered most of the benefits of the ‘Lalu Raj’, while the larger mass of Backwards remained poor. But, they supported Lalu Prasad Yadav till 2005 because he provided them with a sense of pride and participation.

Politics is an act of self-location. Lalu Prasad Yadav loomed large because he emerged at a particular historical conjunction. With his advent, also emerged the ‘backwards among the backwards’. The one real change Lalu Yadav brought was a change of the caste character of the exploitative order. He gave the Backwards a sense of political participation and the Muslims a qualified sense of security in fractured times. He undid the hegemony of the upper castes and installed his own. He was a product of Caste and not its producer. Political violence and electoral malpractice in Bihar much predated him and his constituency had long been the victims. Be it corruption or political crime, caste war or anarchy, the Congress had set the precedents. Lalu Prasad Yadav was a response.

In the process, by mid-1990s, ‘the killing fields of Bihar… the site of persistent warfare against the poor, the weak, and the exploited of the rural countryside’ had descended in ‘the seven years of Lalu Prasad Yadav’s chief ministership as the populist champion of the poor, into “administrative atrophy” and “anarchy”’. Besieged by fodder scam charges, while Lalu Prasad Yadav was battling his (lack of) ‘right or suitability to continue’ as president of his party and chief minister of his state, the state seemed ‘on the verge of infrastructural collapse at the most fundamental levels of administering a civil society’. Lalu had an unvarnished and unrestrained ‘social justice theme’ in his first term, ‘of assuring izzat i.e., self-respect to the socially and economically deprived of the land’. Deep into his second term (completed by his wife Rabri), ‘the political calculus [showed] splits in the backward caste, untouchable-Dalit, and Muslim alliance which Lalu had crafted so brilliantly before and after the 1990 and 1991 elections’. As Mohammad Sajjad has shown, ‘Muslim society also underwent change in challenging upper caste hegemony [during] Lalu Yadav’s Chief Ministerial tenure. The Momins/Ansaris, the Rayeens, the Kulhaiyas, Pamarias and the Bhatiyaras mobilised their caste groups for access to social justice, not only reservations… but also a share in political power’. In his ally-turned-opponent, Syed Shahabuddin’s words:

“For Lalu Yadav, who swears by Mandal, social justice means the substitution of Bhumihar-Rajput Raj by Yadava Raj, that is, dominance and pre-eminence of the Yadavas in every walk of life.”

thus leading to a section of Muslims [The Pasmanda], in addition to the Koeris and the Kurmis, deserting Lalu.

By the turn of the century, for many, his ‘limiting “tunnel vision” reduced him to the status of yet another Yadav leader’. One of the visible factors for this was the brazen and cynical ‘Yadavisation’ of state administration, which fed ‘the formation of the Samata Party in 1994 by the engineer and Kurmi leader, Nitish Kumar’. In a subterranean sense, as shown by the historian Arvind Das, upwardly mobile middle castes and classes were ‘people not likely to be attracted by Lalu’s politics of poverty’, while being ‘concerned about a civil society of law and order of everyday life, no matter one’s social status or professional position’. A second ‘reality of post-Laloo dominance’ was ‘the softening of [his] scheduled caste-Dalit support base’. It is what has been crystallised as ‘specific secular and political interests, economic interests and personality interactions, which are decisive in determining how people vote… true for any social or religious segment of society; these are never unitary solidarities in any political sense’. As Walter Hauser proffered too:

“…issues of political freedom as well as economic and social freedom and the allied issues of social justice and self-respect have a long history in Bihar… Laloo Prasad Yadav brought the idea to a new level of awareness… But, the concept [went back to] Swami Sahajanand… and Jayaprakash Narayan, and Karpoori Thakur. And, movements like the Kisan Sabha, the Triveni Sangh, the Bihar Socialist Party, and the CPI, the CPI (ML).”

Nitish Kumar

The story of Lalu Prasad Yadav then was also his transformation from being ‘the solution’ to becoming the problem, through the 15 years from 1990 to 2005. Since then, ‘just as Indira was not India, so Lalu is not Bihar’. Nitish Kumar’s government ‘expedited the enquiry process into the Bhagalpur riots (1989) and many aggressors [were] convicted. Most of these [were] Yadavs, which raised uncomfortable questions about Lalu’s famous mantra of the Muslim-Yadav electoral partnership’. Nitish Kumar’s governments have also shown ‘arguably better performance in matters of law and order, road construction, electric supply, reservation of seats for the EBCs and women, 15-point package for minorities… gestures which are looked at with some hope by the common Muslim communities, even though some suspicions and uncertainties do persist among the Muslims due to his alliance with the Hindu BJP’. The quest for social justice in Bihar then, among Backward and Scheduled Castes as well as Muslims since the 1990s has mystified much social commentary and ‘demystified’ many political vote-banks.

Lalu Prasad Yadav

Today, Bihar is a heartland of an estimated 100 million people, 40% of whom are below poverty line and 90% of whom continue to have a rural existence. They share a collective trajectory that can be traced to the colonial creation of rent-seeking landlords by the permanent settlement of 1793. That set Bihar on becoming a ‘classic enclave economy’ through the British Raj. Post-independence, the ‘freight equalization scheme’, an ‘explosive mix of caste and class struggles’, ‘transfer of caste power [and] material benefits to [hitherto] marginalized’, a ‘deinstitutionalized state apparatus and curtailed development’, and, large social groups, from the 14% twice-born castes, 39% OBCs (20% upper OBCs, 19% lower OBCs, 12% Yadavs, 3.5% Kurmis, 4.1% Koeris), 15% Dalits, 16% Muslims have operated within a paradigm of continuity of caste and class conflict. In these seven decades, from the Congress’ ‘social coalition of extremes’ dominated by the upper castes, followed by first the emergence and then the fragmentation of the OBCs, if Karpoori Thakur symbolised what was a precursor for the following Lalu Prasad Yadav, then the latter personified a ‘democratic upsurge’, a ‘plebeian politics [of] narrow-poor redistributive coalitions’. Since 2005, Nitish Kumar has represented a ‘wide-poor coalition [of] Dalits and upper castes’, with the 2015 Bihar assembly elections showing that ‘themes of identity remain central to mobilization efforts of political parties’. Indeed (from Sajjad’s Muslim Politics in Bihar: Changing Contours),

“ …it is said that the class and caste neutral economic policies of Nitish Kumar have broad sub-national support, and have triggered the formation of a ‘Bihari’ identity for the first time, especially after the implementation of positive discrimination for women, lower backwards, and the Dalits in the Panchayati Raj Institutions and [he] essentially represents the agglomeration of non-powerful social categories (Ati Picchra which also includes most of the Arzal and Ajlaf communities of Muslims, and Maha Dalits).”

On the other hand is the view that Nitish Kumar’s ‘governmental concern of welfare and development’ vis-a-vis Lalu Prasad’s ‘agenda of justice, dignity and distribution of governmental resources’ are complimentary to each other. One’s caste-based politics is matched by the other’s functional social engineering; ‘for an emancipative politics of the Dalits, this history holds a clue’. This article has tried to show that the electoral victories achieved from 1989 onwards and the emergence of the legend of Lalu Prasad Yadav represents continuity in this cycle of democratic empowerment and ‘breakdown of the Brahmanical social order’. It is another milestone on this road of identity assertion in Indian and Bihar politics. Bihar has always been severely limited by a deeply divided social structure. Since 1937, Congress adopted the strategy of dealing with these divisions by co-opting the elite into the power structure, providing affirmative actions for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and increasingly the Other Backward Castes, and granting considerable, if conditional and contradictory, cultural autonomy to Muslims. This strategy left much of the ugly social reality untouched. Nevertheless, social mobility was always on the rise widening access to political, economic and social power. In democratic India, castes – as a social unit – have always been perceived as a strong vehicle of improving access to power and promotion of interests and it continues to matter. Increased political significance of castes has provided them a greater social hold. Democracy, industrialisation and an equitable economic redistribution have softened their edges but have not eroded their bases. In fact, they have provided an added economic dimension.

Conflicts have plagued Bihar not so much from economic deprivation, but a deep sense of exclusion and marginality along caste-lines, which must be moderated as much by means of a social transformation as by economic development. The question is whether social mobility in Bihar, having been expressed through the sphere and language of politics, will ultimately reflect a proper economic dimension – a new ‘social contract’ – what {Jeffrey} Witsoe alternatively calls ‘popular sovereignty’: ‘the experience of local power’ and ‘everyday interactions with state institutions’ that revolved around ‘dignity’; a democratic demand that ‘verily characterizes India’s postcolonial democracy’. It was a question that had first emerged during the Janeyu Movement during the 1920s and then evolved during the tetchy relationship between the Indian National Congress and the Triveni Sangh between the 1930s and 1950s. Having surveyed that, the article then showed the rise, fall and eclipse of the Socialists and the Congress on the caste question for two decades from the 1960s, especially 1967, and thereby set the historical scene for the advent of Lalu Prasad Yadav. Like many era-inaugurating events, hindsight has since distorted our understanding of this process, akin to Borges’ ‘forking paths’ or, closer home, ‘changing rivers’ in the heartland of Bihar, whose saga is one of resurrection.

Rakesh Ankit’s paper Caste Politics in Bihar: In Historical Continuum has been carried with the permission of its author. It has been presented without its abstract, citations and footnotes and bibliography for purposes of easier reading. You can read this paper in its entirety here.

* Braces – {} – have been used within quotes wherever an explanation has been added by us.

Rakesh Ankit is a lecturer in History and International Politics at the Loughborough University, UK. He studied history at Delhi, Oxford and Southampton and taught at OP Jindal University (Sonipat, India). His previous research was on the evolution of the Kashmir conflict against the twin backdrops of Decolonisation and the Cold War. His current project looks at the Interim Governments in India, 1946-52. You can read more about him and his work here.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply