There is so much Islamophobia that plagues the world today, that it is easy to forget that Islam has had a rich and varied journey with modernity that flourished particularly in the 19th century. It is easy to forget feminists like Tahereh, writers and intellectuals like Ibrahim Sinasi and Islamic modernists like Muhammad Abduh and Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani. Closer home, it is easy to forget the Freedom of Intellect Movement that arose in Dhaka, espousing the cause of rational humanism.

You may have things that you agree or disagree with these modernists on, but the fact that they were grappling with key questions of the future, revisiting the meaning of Islam, and in the process changing not only themselves but worlds around them and worlds to come is irrefutable. Syed Ahmad Khan was one such person. A scholar, philosopher, pragmatist and reformer in 19th century British India, he advocated Islam’s rationalist or Mu ‘taliza tradition to make the religion more compatible with science and present day living. One could debate Syed Ahmad’s (Or ‘Sir Syed’s’, as he was called by many after knighthood) support of the British during the 1857 revolt, or the credence he contributed to the two-nation theory, but his indefatigable work in re-interpreting Islam (incurring fatwas from members of his own community), developing the Urdu language and setting up institutions like the Gulshan and Victoria schools, the Scientific Society of Aligarh and the Muhamaddan Anglo-Oriental College (today’s Aligarh Muslim University) is undeniable.

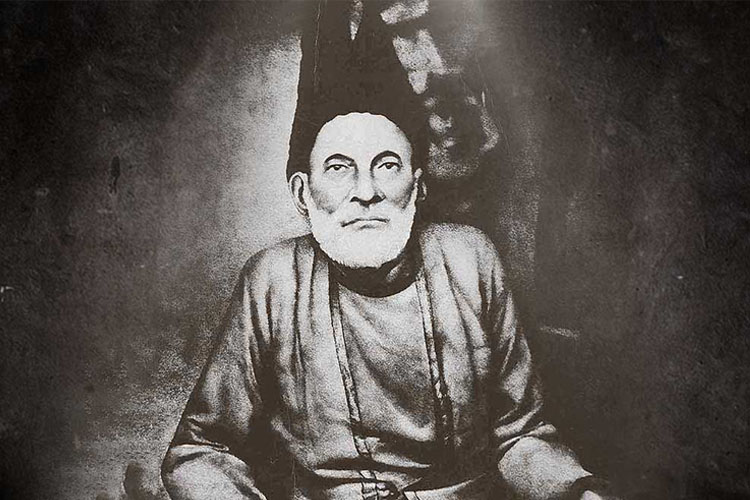

But this item harks back to before a lot of this happened, to a time when Syed Ahmad was nearing his forties and Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib – that giant of Urdu and Persian poetry as well as prose who needs no introduction – was nearing his sixties. Syed Ahmad had just finished at that time a new edition of Abi’l-Fazl’s Ai’n-e Akbari and requested Ghalib to write a preface for it. Ghalib rejected the idea, but rejection with Ghalib was never a simple affair. He responded to Syed Ahmad’s request with this Persian Poem that is available to English readers thanks to the efforts of writer, poet, critic and theorist Shamsur Rahman Faruqi. Through this poem, Ghalib reprimands Syed Ahmad, “made up entirely of wisdom and splendour”, for wasting his considerable talents by delving into the past and the work of those who are long gone. Instead he suggested he look to the “Sahibs of England” and the “laws and rules” and “science and skills” they have produced, overtaking the “efforts of the forebears (ancestors)”.

“The poem was unexpected,” Faruqi writes in an essay titled ‘From Antiquary to Social Revolutionary: Syed Ahmad Khan and the Colonial Experience’. “But it came at the time when Syed Ahmad Khan’s thought and feelings themselves were inclining toward change. Ghalib seemed to be acutely aware of an European [English]-sponsored change in world polity, especially Indian polity. Syed Ahmad might well have been piqued at Ghalib’s admonitions, but he would also have realized that Ghalib’s reading of the situation, though not nuanced enough, was basically accurate. Syed Ahmad Khan may also have felt that he, being better informed about the English and the outside world, should have himself seen the change that now seemed to be just round the corner.”

Faruqi says, towards the conclusion of his essay: “I don’t need to dilate upon the poem’s contents. It makes the pastness of the past extremely clear. The present and the future are here, and they are in the hands of the innovators, the technologists, the information-expediters and controllers. Small wonder that Sir Syed Ahmad Khan never again wrote a word in praise of the Ai’n-e Akbari and in fact gave up taking active interest in history and archaeology.”

He adds: “He did edit another two historical texts over the next few years, but neither of them was anything like the A’in: a vast and triumphalist document on the governance of Akbar. The A’in was also the world’s first anthropological text and gazetteer, and much else besides.”

You can read the essay here:

The poem that follows, besides reflecting a turning point of sorts in significant thinking of the times, also stands as a testament to the diversity of thought. In doing so it annihilates another bias common to Islamophobists as well as other bearers of prejudice— progress and modernity are products of an interaction and simultaneous growth of minds, not homogenous opacities. Also, there is no one kind of ‘Indian Muslim’ just as there is no one kind of ‘Muslim’ or ‘Hindu’ or ‘Christian’ or ‘Indian’. Scholars understand this. It is time we all did too.

Is now open, because of the Syed’s grace and fortune,

The eye began to see, the arm found strength

That which was wrapped in ancient clothes, now put on a new dress.

And this idea of his, to establish its text and edit the A’in

Puts to shame his exalted capability and potential,

He put his heart to a task and pleased himself

But did something like freeing a servant who was already free.

One who isn’t capable of admiring his quality

Would no doubt praise him for this task,

For such a task, of which this book is the basis

Only a hypocrite can offer praise.

I, who am the enemy of pretence

And have a sense of my own truthfulness,

If I don’t give him praise for this task

It’s proper that I find occasion to praise.

I have nothing to say to the perverse

None know what I know of arts and letters,

In the whole world, this merchandise has no buyer.

What profit could my Master hope from it?

It should be said, it’s an excellent inventory

So what’s there to see that’s worth seeing?

And if you talk with me of Laws and Rules

Open your eyes, and in this ancient halting-place

Look at the Sahibs of England.

Look at the style and practice of these,

See what Laws and Rules they have made for all to see

What none ever saw, they have produced.

Science and skills grew at the hands of these skilled ones

Their efforts overtook the efforts of the forebears.

This is the people that owns the right to Laws and Rules

None knows to rule a land better than they,

Justice and Wisdom they’ve made as one

They have given hundreds of laws to India.

The fire that one brought out of stone

How well these skilled ones bring out from straw!

What a spell have they struck on water

That a vapour drives the boat in water!

Sometimes the vapour takes the boat down the sea

Sometimes the vapour brings down the sky to the plains.

Vapour makes the sky-wheel go round and round

Vapour is now like bullocks, or horses.

Vapour makes the ship speed

Making wind and wave redundant.

Their instruments make music without the bow

They make words fly high like birds:

Oh don’t you see that these wise people

Get news from thousands of miles in a couple of breaths?

They inject fire into air

And the air glows like embers,

Go to London, for in that shining garden

The city is bright in the night, without candles.

Look at the businesses of the knowledgeable ones

In every discipline, a hundred innovators!

Before the Laws and Rules that the times now have

All others have become things of yesteryears,

Wise and sensitive and prudent one, does your book

Have such good and elegant Laws?

When one sees such a treasure house of gems

Why should one glean corn from that other harvest?

Well, if you speak of its style, it’s good

No, it’s much better than all else that you seek

But every good always has a better too

If there’s a head, there’s also a crown for it.

Don’t regard that Generous Source as niggardly

It’s a Date-Palm whose fruit drops like sweet light,

Worshipping the Dead is not an auspicious thing

And wouldn’t you too think that it’s no more than just words?

The Rule of silence pleases my heart, Ghalib

You spoke well doubtless, not speaking is well too.

Here in this world your creed is to worship all the Prophet’s children,

Go past praising, your Law asks you to pray:

For Sd Ahmad Khan-e Arif Jang

Who is made up entirely of wisdom and splendour

Let there be from God all that he might wish for

Let an auspicious star lead all his affairs.

Aims to make widely available primary sources, work by professional historians and scholars and writers who bring a fresh insight to historical understanding.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Love the article and enjoyed reading it.