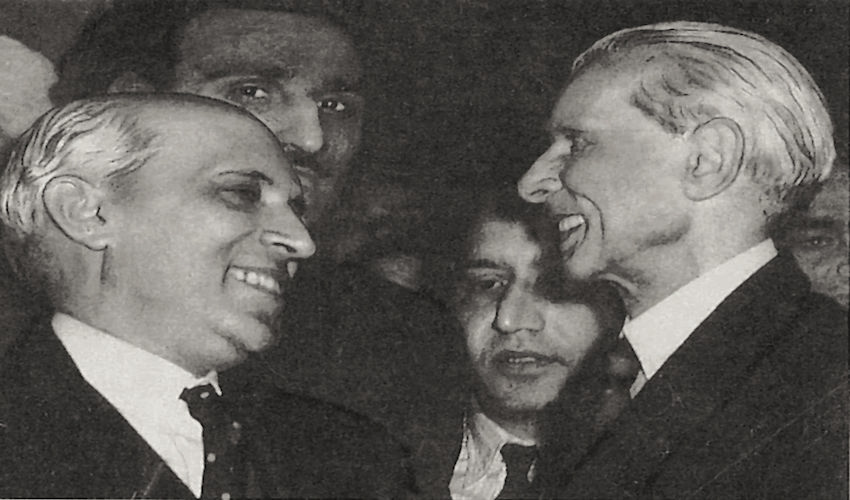

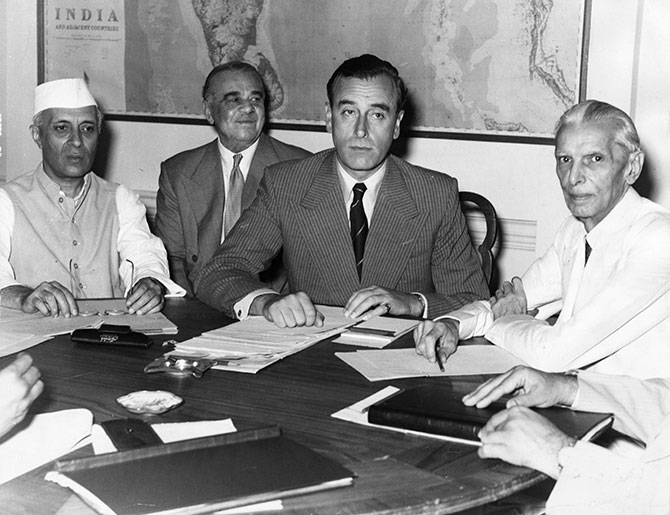

Jawaharlal Nehru and Muhammad Ali Jinnah

“When there is a conflict of opinion, a clarification of the opposing opinions is an essential preliminary to their consideration.” — Jawaharlal Nehru, in this letter to Muhammad Ali Jinnah (4th February, 1938)

Continuing our series titled ‘Great Debates’ (you can read previous debates we have carried in this series, between Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore here and here), we bring to you a heated, yet civil exchange from 1938, between Jawaharlal Nehru and Muhammad Ali Jinnah, on the Muslim representation and the ‘communal question’, as published by Tripurdaman Singh and Adeel Hussain in their book Nehru: The Debates that Defined India.

Both Jawaharlal Nehru and Muhammad Ali Jinnah were hailed as secularists, but when it came to politics their relationship ranged from the respectful to the bitter. They often fundamentally disagreed with one another on how to tackle certain political problems of the day.

But, despite each being a spokesperson for a different political body, their interactions, while often heated, were marked nevertheless, by consistent civility. Jinnah, the president of the Muslim League, a party founded to voice the interests of Muslims on the national level in colonial India, praised Nehru for “his sincerity and genuineness of purpose”. Nehru also referred to Jinnah as a “distinguished leader”.

Jinnah asserted that “there is no progress for India until the Musalmans and Hindus are united,” earning the title of the “best ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity” (bestowed by none other than Sarojini Naidu) for himself. Nehru, however, viewed the “communal question as a conservative reaction to progressive forces”. The employment of religious identity as a primary driver in politics, as denoted by Jinnah’s Muslim League, made him, in Nehru’s eye, “petty-minded”. It also distracted him, according to Nehru, “from the real problems of the country”.

“Broadly secular in his political outlook,” Singh and Hussain tell us, “Nehru never warmed to the idea that religion deserved a place in progressive politics.” Nehru openly raged against the Communal Award of 1932, the chief institution that the British had established to ensure the retention of separate electorates for Indian Muslims. Nehru saw the reservations as opposed to the egalitarian principles of nationalism.

Jinnah, on the other hand, rejected the Nehru Report of 1928 for reasons like its advice to scrap separate electorates and weightage for minorities or vesting residuary powers at the Centre with weaker provinces.

“However, Jinnah was also incensed by the tone of the report,” write Singh and Hussain.

Against the Nehru Report, Jinnah proposed his ‘Fourteen Points’, which sought, among other things, a federal constitutional make-up of India with residual power vested in the provinces, a fixed Muslim representation in the Central legislature and the upholding of separate electorates.

Jinnah often accused Nehru of focusing too much on the international situation and ignoring immediate issues plaguing Indians. Nehru accepted that he was “always fighting shy of the immediate problem [with which he is faced], whether they are in the domain of politics… or in other spheres of national activity”. He conceded this had to do with his theory of change through which he saw “the whole of the world” transforming. For Nehru, Singh and Hussain tell us, “As India’s struggle was interconnected with a broader global issue around imperialism, local issues could only be solved by approaching them from an international perspective.”

Congress, led by Jawaharlal Nehru, emerged victorious in the 1936-37 provincial elections, thereby dealing a blow to Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s vision of uniting Muslims under a political banner, since the Muslim League secured only about half of the reserved seats for the Muslims under the Government of India Act of 1935. Any ideas to do with the formation of a coalition government with the Muslim League were also rejected by Nehru, which then led to a series of increasingly hostile letters exchanged between him and Jinnah, where they discussed their views on Hindu-Muslim relations, the demands of the Muslim League and the idea of Muslim representation.

“In full awareness that the Congress did not require the League to rule, Nehru conducted this communication from a position of strength. Jinnah refused to acknowledge that the election result was an adequate measure of the political value of the Muslim League,” write Singh and Hussain.

Following are three letters from this exchange, written by Nehru and Jinnah to each other in 1938. In this correspondence, Nehru addresses Jinnah’s points of agreements and differences with the Congress, such as those on the question of national language, minority communities and their fundamental rights, as well as larger political and communal issues that the League might have had with regard to the functioning of the Congress. In response, Jinnah disagrees with Nehru’s arguments and, in fact, calls him out for the assertive tone of his letters. The two politicians, at the end of this exchange, decided to publish their correspondence in the press.

Jinnah to Nehru – 17 March 1938

New Delhi,

17 March 1938

Dear Pandit Jawaharlal,

I have received your letter of the 8th of March 1938. Your first letter of the 18th of January conveyed to me that you desire to know the points in dispute for the purpose of promoting Hindu-Muslim unity. When in reply I said the subject matter cannot be solved through correspondence and it was equally undesirable as discussing matters in the press you, in your reply of the 4th of February, formulated a catalogue of grievances with regard to my supposed criticism of the Congress and utterances which are hardly relevant to the question for our immediate consideration. You went on persisting on the same line and you are still of opinion that those matters, although not germane to the present subject, should be further discussed, which I do not propose to do as I have already explained to you in my previous letter.

Jawaharlal Nehru and Muhammad Ali Jinnah

The question with which we started, as I understood, is of safeguarding the rights and the interests of the Mussalmans with regard to their religion, culture, language, personal laws and political rights in the national life, the government and the administration of the country. Various suggestions have been made which will satisfy the Mussalmans and create a sense of security and confidence in the majority community. I am surprised when you say in your letter under reply, ‘But what are these matters which are germane? It may be that I am dense or not sufficiently acquainted with the intricacies of the problem. If so, I deserve to be enlightened. If you will refer me to any recent statement made in the press or platform which will help me in understanding, I shall be grateful.’ Perhaps you have heard of the Fourteen Points.

Next, as you say, ‘Apart from this much has happened during these past few years which has altered the position.’ Yes, I agree with you, and various suggestions have appeared in the newspapers recently. For instance, if you will refer to the Statesman, dated the 12th of February 1938, there appears an article under the heading ‘Through “Muslim Eyes’ (copy enclosed for your convenience). Next, an article in the New Times, dated the 1st of March 1938, dealing with your pronouncement recently made, I believe at Haripura sessions of the Congress, where you are reported to have said: ‘I have examined this so-called communal question through the telescope, and if there is nothing what can you see.

This article in the New Times appeared on the 1st of March 1938, making numerous suggestions (copy enclosed for your convenience). Further you must have seen Mr Aney’s interview where he warned the Congress mentioning some of the points which the Muslim League would demand.

I consider it is the duty of every true nationalist, to whichever party or community he may belong to make it his business and examine the situation and bring about a pact between the Mussalmans and the Hindus and create a real united front and it should be as much your anxiety and duty as it is mine, irrespective of the question of the party or the community to which we belong.

Now, this is enough to show to you that various suggestions that have been made, or are likely to be made, or are expected to be made, will have to be analysed and ultimately I consider it is the duty of every true nationalist, to whichever party or community he may belong to make it his business and examine the situation and bring about a pact between the Mussalmans and the Hindus and create a real united front and it should be as much your anxiety and duty as it is mine, irrespective of the question of the party or the community to which we belong. But if you desire that I should collect all these suggestions and submit to you as a petitioner for you and your colleagues to consider, I am afraid I can’t do it nor can I do it for the purpose of carrying on further correspondence with regard to those various points with you. But if you still insist upon that, as you seem to do so when you say in your letter, ‘My mind demands clarity before it can function effectively or think in terms of any action. Vagueness or an avoidance of real issues could not lead to satisfactory results. It does seem strange to me that in spite of my repeated requests I am not told what issues have to be discussed.’ This is hardly a correct description or a fair representation, but in that case I would request you to ask the Congress officially to communicate with me to that effect, and I shall place the matter before the Council of the All-India Muslim League; as you yourself say that you are ‘not the Congress President and thus have not the same representative capacity but if I can be of any help on this matter my services are at the disposal of the Congress and I shall gladly meet you and discuss these matters with you’. As to meeting you and discussing matters with you, I need hardly say that I shall be pleased to do so.

Yours sincerely,

M.A. Jinnah

[Enclosure I to the above letter]

Through Muslim Eyes

By Ain-el-Mulk

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru’s Bombay statement of January 2 on the Hindu-Moslem question has produced hopeful reactions and the stage has been set for a talk between the leaders of what, for the sake of convenience, may be described as Hindu India and Moslem India. Whether the Jinnah-Jawaharlal talks will produce in 1938 better results than the Jinnah-Prasad talks did in 1935 is yet to be seen. Too much optimism would not, however, be justified. The Pandit, by way of annotating his Bombay statement while addressing the UP delegates for Haripura at Lucknow, at the end of January, emphatically asserted that in no case would Congress ‘give up its principles’. That was not a hopeful statement because any acceptable formula or pact that may be evolved by the leaders of the Congress and the League would, one may guess, involve the acquiescence of the Congress in separate electorates (at least for a certain period), coalition ministries, recognition of the League as the one authoritative and representative organization of Indian Moslems, authoritative and representative organization of Indian Moslems, modification of its attitude on the question of Hindi and its script, scrapping of Bande Mataram altogether, and possibly a redesigning of the tricolour flag or at least agreeing to give the flag of the League an equal importance. It is possible that with a little statesmanship on both sides agreement can be reached on all these points without any infringement of the principles of either, but the greatest obstacle to a satisfactory solution would still remain, in the shape of the communalists of the Mahasabha, and the irreconcilables of Bengal, all of whom are not of the Mahasabha alone.”

The right of the Congress to speak in the name of Hindus has been openly challenged and even the Jinnah-Prasad formula which did not satisfy the Moslems – and nothing on the lines of which is now likely to satisfy them – has been vehemently denounced by the Bengal Provincial Conference held at Vishnupur which recently passed an extremely communal resolution, and that the latest utterances of the Congress President-elect on the communal situation generally and the Jinnah-Prasad formula in particular show some restraint. The only thing for Moslems to do in the circumstances is to wait and hope for the best, without relaxing their efforts to add daily to the strength of the League, for it will not do to forget that it is the growing power and representative character of the Muslim League which has compelled Congress leaders to recognize the necessity for an understanding with the Moslem community.

The Statesman, New Delhi Edition, 12 February 1938.

[Enclosure II to the above letter]

The Communal Question

In its last session at Haripura, the Indian National Congress passed a resolution for assuring minorities of their religious and cultural rights. The resolution was moved by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and was carried. The speech which Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru made on this occasion was as bad as any speech could be. If the resolution has to be judged in the light of that speech, then it comes to this that the resolution has been passed not in any spirit of seriousness, but merely as a meaningless assurance to satisfy the foolish minorities who are clamouring ‘for the satisfaction of the communal problem’. Mr Jawaharlal Nehru proceeded on the basis that there was really no communal question. We should like to reproduce the trenchant manner in which he put forward the proposition. He said: ‘I have examined the so-called communal question through the telescope and, if there is nothing, what can you see.’ It appears to us that it is the height of dishonesty to move a resolution with these premises.

We should like to tell Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru that he has completely misunderstood the position of the Muslim minority and it is a matter of intense pain that the President of an All-India organization, which claims to represent the entire population of India, should be so completely ignorant of the demands of the Muslim minority.

If there is no minority question, why proceed to pass a resolution? Why not state that there is no minority question? This is not the first time that Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru has expressed his complete inability to understand or see the communal question. When replying to a statement of Mr Jinnah, he reiterated his conviction that in spite of his best endeavour to understand what Mr Jinnah wanted, he could not get at what he wanted. He seems to think that with the Communal Award, which the Congress has opposed, the seats in the Legislature have become assured and now nothing remains to be done. He repeats the offensive statement that the Communal Award is merely a problem created by the middle or upper classes for the sake of few seats in the Legislature or appointments in Government service or for Ministerial positions. We should like to tell Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru that he has completely misunderstood the position of the Muslim minority and it is a matter of intense pain that the President of an All-India organization, which claims to represent the entire population of India, should be so completely ignorant of the demands of the Muslim minority. We shall set forth below some of the demands so that Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru may not have any occasion hereafter to say that he does not know what more the Muslims want. The Muslim demands are:

1. That the Congress shall henceforth withdraw all opposition to the Communal Award and should cease to prate about it as if it were a negation of nationalism. It may be a negation of nationalism but if the Congress has announced in its statement that it is not opposing the Communal Award, the Muslims want that the Congress should at least stop all agitation for the recession of the Communal Award.

2. The Communal Award merely settles the question of the representation of the Muslims and of other minorities in the Legislatures of the country. The further question of the representation of the minorities in the services of the country remains. Muslims demand that they are as much entitled to be represented in the services of their motherland as the Hindus and since the Muslims have come to realize by their bitter experience that it is impossible for any protection to be extended to Muslim rights in the matter of their representation in the services, it is necessary that the share of the Muslims in the services should be definitely fixed in the constitution and by statutory enactment so that it may not be open to any Hindu head of any department to ride roughshod over Muslim claims in the name of ‘Efficiency’. Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru knows that in the name of efficiency and merit, the rights of Indians to man the services of their country was denied by the bureaucracy. Today when Congress is in power in seven Provinces, the Muslims have a right to demand the Congress leaders that they shall unequivocally express themselves in this regard.

3 Muslims demand that the protection of their Personal Law and their culture shall be guaranteed by the statute. And as an acid test of the sincerity of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and the Congress in this regard, Muslims demand that the Congress should take in hand the agitation in connection with the Shahidganj Mosque and should use its moral Pressure to ensure that the Shahidganj Mosque is restored to its original position and that the Sikhs desist from profane uses and thereby injuring the religious susceptibilities of the Muslims.

4. Muslims demand that their right to call Azan and perform religious ceremonies shall not be fettered in any way. We should like to tell Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru that in a village, in the Kasur Tehsil, of the Lahore District, known as Raja Jang, the Muslim inhabitants of that place are not allowed by the Sikhs to call out their Azans loudly. With such neighbours it is necessary to have a statutory guarantee that the religious rights of the Muslims shall not be in any way interfered with and on the advent of Congress rule to demand of the Congress that it shall use its powerful organization for the prevention of such an event. In this connection we should like to tell Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru that the Muslims claim cow slaughter as one of their religious rights and demand that so long as the Sikhs are permitted to carry on Jhatka and to live on Jhatka, the Muslims have every right to insist on their undoubted right to slaughter cows. Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru is not a very great believer in religious injunctions. He claims to be living on the economic plane and we should like Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru to know that for a Muslim the question of cow slaughter is a measure of economic necessity and that therefore it [is] not open to any Hindu to statutorily prohibit the slaughter of cows.

5. Muslims demand that their majorities in the Provinces in which they are at present shall not be affected by any territorial redistributions or adjustments. The Muslims are at present in majority in the provinces of Bengal, Punjab, Sind, North West Frontier Province and Baluchistan. Let the Congress hold out the guarantee and express its readiness to the incorporation of this guarantee in the Statute that the present distribution of the Muslim population in the various provinces shall not be interfered with through the medium of any territorial distribution or re-adjustment.

6. The question of the national anthem is another matter. Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru cannot be unaware that Muslims all over have refused to accept the Bande Mataram or any expurgated addition of that anti-Muslim song as a binding national anthem. If Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru cannot succeed in inducing the Hindu majority to drop the use of this song, then let him not talk so tall, and let him realize that the great Hindu mass does not take him seriously except as a strong force to injure the cause of Muslim solidarity.

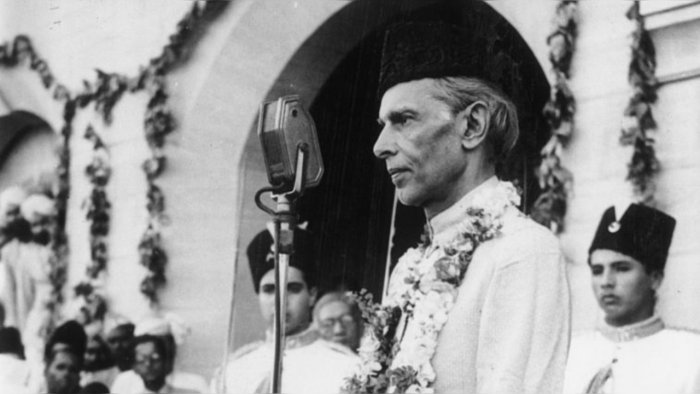

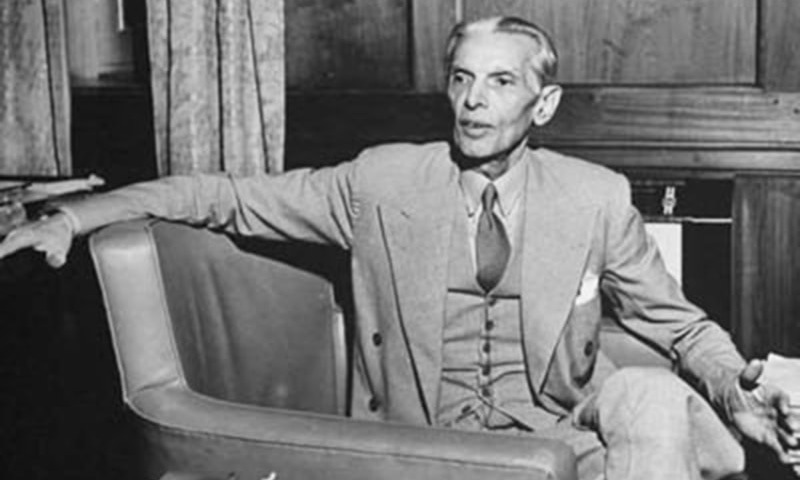

Muhammad Ali Jinnah

7. The question of language and script is another demand of the Muslims. The Muslims insist on Urdu being practically their national language; they want statutory guarantees that the use of [the] Urdu tongue shall not in any wiser manner be curtailed or damaged.

8. The question of the representation of the Muslims in the local bodies is another unsolved question. Muslims demand that the principle underlying the Communal Award, namely, separate electorates and representation according to population strength should apply uniformly in all the various local and other elected bodies from top to bottom.

We can go on multiplying this list but for the present we should like to know the reply of the Congress and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru to the demands that we have set forth above. We should like Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru fully to understand that the Muslims are more anxious than the Hindus to see complete independence in the real sense of that term established in India. They do not believe in any Muslim Raj for India and will fight a Hindu Raj tooth and nail. They stand for the complete freedom of the country and of all classes inhabiting this country, but they shall oppose the establishment of any majority raj of a kind that will make a clean sweep of the cultural, religious and political guarantees of the various minorities as set forth above. Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru is under the comforting impression that the question set forth above are trivial questions but he should reconsider his position in the light of the emphasis and importance which the minorities which are affected by the programme of the Congress place on these matters. After all it is the minorities which are to judge and not the majorities. It appears to us that with the attitude of mind which Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru betrayed in his speech and which the seconder of that resolution equally exhibited in his speech, namely, that the question of minorities and majorities was an artificial one and created to suit vested interests, it is obvious that nothing can come out of the talks that Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru recently initiated between himself and Mr Jinnah. If the Congress is in the belief that this reiteration of its inane pledge to the minorities will satisfy them and that they will be taken in by mere words, the Congress is badly mistaken.

New Times, Lahore, 1 March 1938

Nehru to Jinnah – 6 April 1938

Calcutta,

6 April 1938

Dear Mr Jinnah,

Your last letter of the 17th March reached me in the Kumaun hills where I had gone for a brief holiday. From there I have come to Calcutta. I propose to return to Allahabad today and I shall probably be there for the greater part of April. If it is convenient for you to come there we could meet. Or if it suits you better to go to Lucknow I shall try to go there.

I am glad that you have indicated in your last letter a number of points which you have in mind. The enclosures you have sent mention these and I take it that they represent your viewpoint. I was somewhat surprised to see this list as I had no idea that you wanted to discuss many of these matters with us. Some of these are wholly covered by previous decisions of the Congress, some others are hardly capable of discussion.

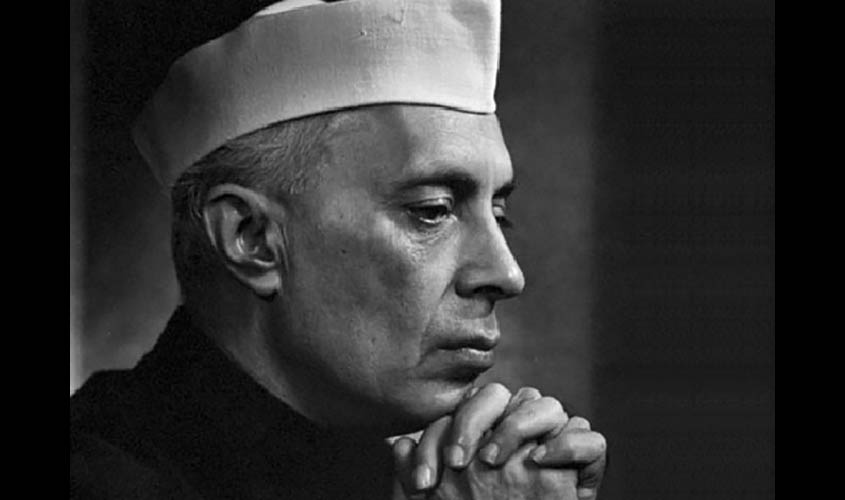

Jawaharlal Nehru

As far as I can make out from your letter and the enclosures you have sent, you wish to discuss the following matters:

1. The Fourteen Points formulated by the Muslim League in 1929.

2. The Congress should withdraw all opposition to the Communal Award and should not describe it as a negation of nationalism.

3. The share of the Muslims in the state services should be definitely fixed in the Constitution by statutory enactment.

4. Muslim Personal Law and culture should be guaranteed by Statute.

5. The Congress should take in hand the agitation in connection with the Shahidganj Mosque and should use its moral pressure to enable the Muslims to gain possession of the mosque.

6. The Muslim’s right to call Azan and perform religious ceremonies should not be fettered in any way.

7. Muslims should have freedom to perform cow-slaughter.

8. Muslim majorities in the Provinces, where such majorities exist at present, must not be affected by any territorial redistribution or adjustments.

9. The Bande Mataram song should be given up.

10. Muslims want Urdu to be the national language of India and they desire to have statutory guarantees that the use of Urdu shall not be curtailed or damaged.

11. Muslim representation in the local bodies should be governed by the principles underlying the Communal Award, that is separate electorates and population strength.

12. The tricolour flag should be changed or, alternatively, the flag of the Muslim League should be given equal importance.

13. Recognition of the Muslim League as the one authoritative and representative organization of Indian Muslims.

14. Coalition ministries.

It is further stated that the formula evolved by you and Babu Rajendra Prasad in 1935 does not satisfy the Muslims now and nothing on those lines will satisfy them. It is added that the list given above is not a complete list and that it can be augmented by the addition of further ‘demands’. Not knowing these possible and unlimited additions I can say nothing about them. But I should like to deal with the various matters specifically mentioned and to indicate what the Congress attitude has been in regard to them.

But before considering them, the political and economic background of the free India we are working for has to be kept in mind, for ultimately that is the controlling factor. Some of these matters do not arise in considering an independent India or take a particular shape or have little importance. We can discuss them in terms of Indian independence or in terms of the British dominance of India continuing. The Congress naturally thinks in terms of independence, though it adjusts itself occasionally to the pressure of transitional and temporary phases. It is thus not interested in amendments to the present constitution, but aims at its removal and its substitution by a constitution framed by the people through a Constituent Assembly.

But before considering them, the political and economic background of the free India we are working for has to be kept in mind, for ultimately that is the controlling factor. Some of these matters do not arise in considering an independent India or take a particular shape or have little importance. We can discuss them in terms of Indian independence or in terms of the British dominance of India continuing. The Congress naturally thinks in terms of independence, though it adjusts itself occasionally to the pressure of transitional and temporary phases. It is thus not interested in amendments to the present constitution, but aims at its removal and its substitution by a constitution framed by the people through a Constituent Assembly.

Another matter has assumed an urgent and vital significance and this is the exceedingly critical international situation and the possibility of war. This must concern India greatly and affect her struggle for freedom. This must therefore be considered the governing factor of the situation and almost everything else becomes of secondary importance, for all our efforts and petty arguments will be of little avail if the very foundation is upset. The Congress has clearly and repeatedly laid down its policy in the event of such a crisis and stated that it will be no party to imperialist war. The Congress will very gladly and willingly cooperate with the Muslim League and all other organizations and individuals in the furtherance of this policy.

I have carefully looked through the various matters to which you have drawn attention in your letter and its enclosures and I find that there is nothing in them which refers to or touches the economic demands of the masses or affects the all-important questions of poverty and unemployment. For all of us in India these are the vital issues and unless some solution is found for them, we function in vain. The question of state services, howsoever important and worthy of consideration it might be, affects a very small number of people. The peasantry, industrial workers, artisans and petty shop-keepers form the vast majority of the population and they are not improved in any way by any of the demands listed above. Their interests should be paramount.

Many of the ‘demands’ involve changes of the constitution which we are not in a position to bring about. Even if some such changes are desirable in themselves, it is not our policy to press for minor constitutional changes. We want to do away completely with the present constitution and replace it by another for a free India.

In the same way, the desire for statutory guarantees involves constitutional changes which we cannot give effect to. All we can do is to state that in a future constitution for a free India we want certain guarantees to be incorporated. We have done this in regard to religious, cultural, linguistic and other rights of minorities in the Karachi resolution on fundamental rights. We would like these fundamental rights to be made a part of the constitution.

I now deal with the various matters listed above.

1. The Fourteen Points, I had thought, were somewhat out of date. Many of their provisions have been given effect to by the Communal Award and in other ways, some others are entirely acceptable to the Congress; yet others require constitutional changes which, as I have mentioned above, are beyond our present competence. Apart from the matters covered by the Communal Award and those involving a change in the constitution, one or two matters remain which give rise to differences of opinion and which are still likely to lead to considerable argument.

2. The Congress has clearly stated its attitude towards the Communal Award, and it comes to this that it seeks alterations only on the basis of mutual consent of the parties concerned. I do not understand how anyone can take objection to this attitude and policy. If we are asked to describe the Award as not being anti-national, that would be patently false. Even apart from what it gives to various groups, its whole basis and structure are anti-national and come in the way of the development of national unity. As you know it gives an overwhelming and wholly underserving weightage to the European elements in certain parts of India. If we think in terms of an independent India, we cannot possibly fit in this Award with it. It is true that under stress of circumstances we have sometimes to accept as a temporary measure something that is on the face of it anti-national. It is also true that in the matters governed by the Communal Award we can only find a satisfactory and abiding solution by the consent and goodwill of the parties concerned. That is the Congress policy.

3. The fixing of the Muslims’ share in the state services by statutory enactment necessarily involves the fixing of the shares of other groups and communities similarly. This would mean a rigid and compartmental state structure which will impede progress and development. At the same time it is generally admitted that state appointments should be fairly and adequately distributed and no community should have cause to complain. It is far better to do this by convention and agreement. The Congress is fully alive to this issue and desires to meet the wishes of various groups in the fullest measure so as to give to all minority communities, as stated in No. 11 of the Fourteen Points, ‘an adequate share in all the services of the state and in local self-governing bodies having due regard to the requirements of efficiency’. The state today is becoming more and more technical and demands expert knowledge in its various departments. It is right that, if a community is backward in this technical and expert knowledge, special efforts should be made to give it this education to bring it up a to higher level.

I understand that at the Unity Conference held at Allahabad in 1933 or thereabouts, a mutually satisfactory solution of this question of state services was arrived at.

4. As regards protection of culture, the Congress has declared its willingness to embody this in the fundamental laws of the constitution. It has also declared that it does not wish to interfere in any way with the personal law of any community.

5. I am considerably surprised at the suggestions that the Congress should take in hand the agitation in connection with the Shahidganj Mosque. That is a matter to be decided either legally or by mutual agreement. The Congress prefers in all such matters the way of mutual agreement and its services can always be utilized for this purpose where there is no opening for them and a desire to this effect on the part of the parties concerned. I am glad that the Premier of the Punjab has suggested that this is the only satisfactory way to a solution of the problem.

Jawaharlal Nehru

6. The right to perform religious ceremonies should certainly be guaranteed to all communities. The Congress resolution about this is quite clear. I know nothing about the particular incident relating to a Punjab village which has been referred to. No doubt many instances can be gathered together from various parts of India where petty interferences take place with Hindu, Muslim or Sikh ceremonies. These have to be tactfully dealt with wherever they arise. But the principle is quite clear and should be agreed to.

7. As regards cow-slaughter there has been a great deal of entirely false and unfounded propaganda against the Congress suggesting that the Congress was going to stop it forcibly by legislation. The Congress does not wish to undertake any legislative action in this matter to restrict the established rights of the Muslims.

8. The question of territorial distribution has not arisen in any way. If and when it arises it must be dealt with on the basis of mutual agreement of the parties concerned.

9. Regarding the Bande Mataram song the Working Committee issued a long statement in October last to which I would invite your attention. First of all, it has to be remembered that no formal national anthem has been adopted by the Congress at any time. It is true, however, that the Bande Mataram song has been intimately associated with Indian nationalism for more than thirty years and numerous associations of sentiment and sacrifice have gathered round it. Popular songs are not made to order, nor can they be successfully imposed. They grow out of public sentiment. During all these thirty or more years the Bande Mataram song was never considered as having any religious significance and was treated as a national song in praise of India. Nor, to my knowledge, was any objection taken to it except on political grounds by the Government. When, however, some objections were raised, the Working Committee carefully considered the matter and ultimately decided to recommend that certain stanzas, which contained certain allegorical references, might not be used on national platforms or occasions. The two stanzas that have been recommended by the Working Committee for use as a national song have not a word or a phrase which can offend anybody from any point of view and I am surprised that anyone can object to them. They may appeal to some more than to others. Some may prefer another national song. But to compel large numbers of people to give up what they have long valued and grown attached to is to cause needless hurt to them and injure the national movement itself. It would be improper for a national organization to do this.

10. About Urdu and Hindi I have previously written to you and have also sent you my pamphlet on ‘The Question of Language’. The Congress has declared in favour of guarantees for languages and culture. I want to encourage all the great provincial languages of India and at the same time to make Hindustani, as written both in the Nagri and Urdu scripts, the national language. Both scripts should be officially recognized and the choice should be left to the people concerned. In fact this policy is being pursued by the Congress Ministries.

About Urdu and Hindi I have previously written to you and have also sent you my pamphlet on ‘The Question of Language’. The Congress has declared in favour of guarantees for languages and culture. I want to encourage all the great provincial languages of India and at the same time to make Hindustani, as written both in the Nagri and Urdu scripts, the national language. Both scripts should be officially recognized and the choice should be left to the people concerned.

11. The Congress has long been of opinion that joint electorates are preferable to separate electorates from the point of view of national unity and harmonious co-operation between the different communities. But joint electorates, in order to have real value, must not be imposed on unwilling groups. Hence the Congress is quite clear that their introduction should depend on their acceptance by the people concerned. This is the policy that is being pursued by the Congress Ministries in regard to Local bodies. Recently in a Bill dealing with local bodies introduced in the Bombay Assembly, separate electorates were maintained but an option was given to the people concerned to adopt a joint electorate, if they so chose. This principle seems to be in exact accordance with No. 5 of the Fourteen Points, which lays down that ‘representation of communal groups shall continue to be by means of separate electorate as at present, provided that it shall be open to any community, at any time, to abandon its separate electorate in favour of joint electorate’. It surprises me that the Muslim League group in the Bombay Assembly should have opposed the Bill with its optional clause although this carried out the very policy of the Muslim League.

May I also point out that in the resolution passed by the Muslim League in 1929, at the time it adopted the Fourteen Points, it was stated that ‘the Mussalmans will not consent to join electorates unless Sind is actually constituted into a separate province and reforms in fact are introduced in the NWF Province and Baluchistan on the same footing as in other provinces’. Since then Sind has been separated and the NWF Province has been placed on a level with other provinces. So far as Baluchistan is concerned the Congress is committed to a levelling up of this area in the same way.

12. The national tricolour flag was adopted originally in 1929 by the Congress after full and careful consultation with eminent Muslim, Sikh and other leaders. Obviously a country and national movement must have a national flag representing the nation and all communities in it. No communal flag can represent the nation. If we did not possess a national flag now we would have to evolve one. The present national flag had its colours originally selected in order to represent the various communities, but we did not like to lay stress on this communal aspect of colours. Artistically I think the combination of orange, white and green resulted in a flag which is probably the most beautiful of all national flags. For these many years our flag has been used and it has spread to the remotest village and brought hope and courage and a sense of all India unity to our masses. It has been associated with great sacrifices on the part of our people, including Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, and many have suffered lathi blows and imprisonment and even death in defending it from insult or injury. Thus a powerful sentiment has grown in its favour. On innumerable occasions Maulana Mohamed Ali, Maulana Shaukat Ali and many leaders of the Muslim League today have associated themselves with this flag and emphasized its virtues and significance as a symbol of Indian unity. It has spread outside the Congress ranks and been generally recognized as the flag of the nation. It is difficult to understand how anyone can reasonably object to it now.

Communal flags cannot obviously take its place for that can only mean a host of flags of various communities being used together and thus emphasizing our disunity and separateness. Communal flags might be used for religious functions but they have no place at any national functions or over any public building meant for various communities.

May I add that during the past few months, on several occasions, the national flag has been insulted by some members or volunteers of the Muslim League. This has pained us greatly but we have deliberately avoided anything in the nature of conflict in order not to add to communal bitterness. We have also issued strict orders, and they have been obeyed, that no interference should take place with the Muslim League flag, even though it might be inappropriately displayed.

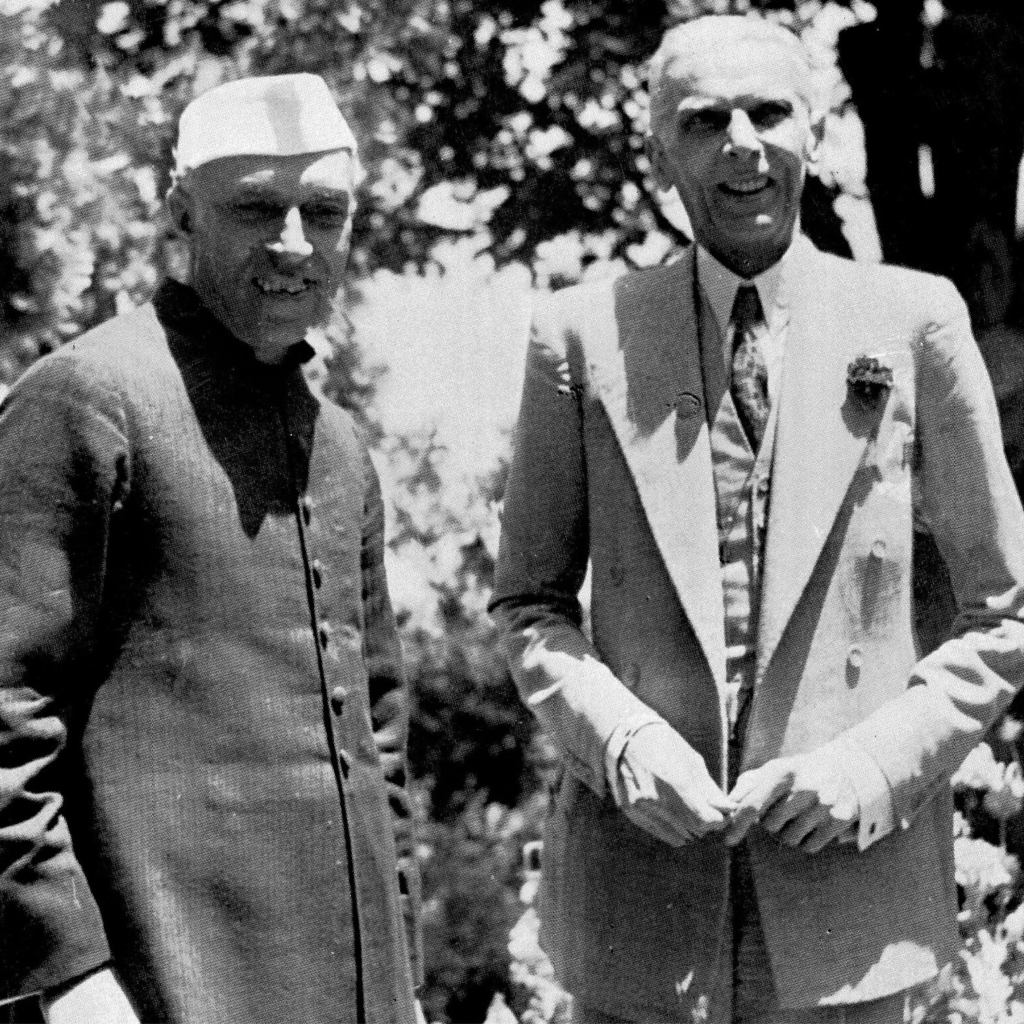

Jawaharlal Nehru and Muhammad Ali Jinnah in a meeting with Lord Mountbatten

13. I do not understand what is meant by our recognition of the Muslim League as the one and only organization of Indian Muslims. Obviously the Muslim League is an important communal organization and we deal with it as such. But we have to deal with all organizations and individuals that come within our ken. We do not determine the measure or importance or distinction they possess. There are a large number, about a hundred thousand, of Muslims on the Congress rolls, many of whom have been our close companions, in prisons and outside, for many years and we value their comradeship highly. There are many organizations which contain Muslims and non-Muslims alike, such as trade unions, peasant unions, kisan sabhas, debt committees, zamindar associations, chambers of commerce, employers’ association, etc., and we have contacts with them. There are special Muslim organizations such as the Jamiat-ul-Ulema, the Proja Party, the Ahrars and others, which claim attention. Inevitably the more important the organization, the more the attention paid to it, but this importance does not come from outside recognition but from inherent strength. And the other organizations, even though they might be younger and smaller, cannot be ignored.

14. I should like to know what is meant by coalition ministries. A ministry must have a definite political and economic programme and policy. Any other kind of ministry would be a disjointed and ineffective body, with no clear mind or direction. Given a common political and economic programme and policy, cooperation is easy. You know probably that some such cooperation was sought for and obtained by the Congress in the Frontier Province. In Bombay also repeated attempts were made on behalf of the Congress to obtain this cooperation on the basis of a common programme. The Congress has gone to the assemblies with a definite programme and in furtherance of clear policy. It will always gladly cooperate with other groups, whether it is a majority or a minority in an assembly, in furtherance of that programme and policy. On that basis I conceive of even coalition ministries being formed. Without that basis the Congress has no interest in a ministry or in an assembly.

I have dealt, I am afraid at exceeding length, with the various points raised in your letter and its enclosures. I am glad that I have had a glimpse into your mind through this correspondence as this enables me to understand a little better the problems that are before you and perhaps others. I agree entirely that it is the duty of every Indian to bring about [a] harmonious joint effort of all of us for the achievement of India’s freedom and the ending of the poverty of her people. For me, and I take it for most of us, the Congress has been a means to that end and not an end in itself. It has been a high privilege for us to work through the Congress because it has drawn to itself the love of millions of our countrymen, and through their sacrifice and united effort, taken us a long way to our goal. But much remains to be done and we have all to pull together to that end.

Personally the idea of pacts and the like does not appeal to me, though perhaps they might be necessary occasionally. What seems to me far more important is a more basic understanding of each other, bringing with it the desire and ability to cooperate together. That larger cooperation, if it is to include our millions must necessarily be in the interests of these millions. My mind therefore is continually occupied with the problems of these unhappy masses of this country and I view all other problems in this light. I should live to view the communal problem also in this perspective for otherwise it has no great significance for me.

Personally the idea of pacts and the like does not appeal to me, though perhaps they might be necessary occasionally. What seems to me far more important is a more basic understanding of each other, bringing with it the desire and ability to cooperate together. That larger cooperation, if it is to include our millions must necessarily be in the interests of these millions. My mind therefore is continually occupied with the problems of these unhappy masses of this country and I view all other problems in this light. I should live to view the communal problem also in this perspective for otherwise it has no great significance for me.

You seem to imagine that I wanted you to put forward suggestions as a petitioner, and then you propose that the Congress should officially communicate with you. Surely you have misunderstood me and done yourself and me an injustice. There is no question of petitioning either by you or by me, but a desire to understand each other and the problem that we have been discussing. I do not understand the significance of your wanting an official intimation from the Congress. I did not ask you for an official reply on behalf of the Muslim League. Organizations do not function in this way. It is not a question of prestige for the Congress or for any of us, for we are keener on reaching the goal we have set before us, than on small matters of prestige. The Congress is a great enough organization to ignore such petty matters, and if some of us have gained a measure of influence and popularity, we have done so in the shadow of the Congress.

You will remember that I took the initiative in writing to you and requesting you to enlighten me as to what your objections were to the Congress policy and what, according to you, were the points in dispute. I had read many of your speeches, as reported in the press, and I found to my regret that they were full of strong attacks on the Congress which, according to my way of thinking, were not justified. I wanted to remove any misunderstandings, where such existed, and to clear the air.

I have found, chiefly in the Urdu press, the most astounding falsehoods about the Congress. I refer to facts, not to opinions, and to facts within my knowledge. Two days ago, here in Calcutta, I saw a circular letter or notice issued by a secretary of the Muslim League. This contained a list of the so-called misdeeds of the UP Government. I read this with amazement for there was not an atom of truth in most of the charges. I suppose they were garnered from the Urdu press. Through the press and the platform such charges have been repeated on numerous occasions and communal passions have thus been roused and bitterness created. This has grieved me and I have sought by writing to you and to Nawab Ismail Khan to find a way of checking this deplorable deterioration of our public life, as well as a surer basis for cooperation. That problem still faces us and I hope we shall solve it.

I have mentioned earlier in this letter the critical international situation and the terrible sense of impending catastrophe that hangs over the world. My mind is obsessed with this and I want India to realize it and be ready for all consequences, good or ill, that may flow from it. In this period of world crisis all of us, to whatever party or group we might belong and whatever our differences might be, have the primary duty of holding together to protect our people from perils that might encompass them.

I have mentioned earlier in this letter the critical international situation and the terrible sense of impending catastrophe that hangs over the world. My mind is obsessed with this and I want India to realize it and be ready for all consequences, good or ill, that may flow from it. In this period of world crisis all of us, to whatever party or group we might belong and whatever our differences might be, have the primary duty of holding together to protect our people from perils that might encompass them.

Our differences and arguments seem trivial when the future of the world and of India hangs in the balance. It is in the hope that all of us will succeed in building up this larger unity in our country that I have written to you and others repeatedly and at length.

There is one small matter I should like to mention. The report of my speech at Haripura, as given in your letter and the newspaper article, is not correct.

We have been corresponding for some time and many vague rumours float about as to what we have been saying to each other. Anxious inquiries come to me and I have no doubt that similar inquiries are addressed to you also. I think that we might take the public into our confidence now for this is a public matter on which many are interested. I suggest, therefore, that our correspondence might be released to the press. I presume you will have no objection.

Yours sincerely,

Jawaharlal Nehru

Jinnah to Nehru – 12 April 1938

Bombay,

12 April 1938

Dear Pandit Jawaharlal,

I an in receipt of your letter of the 6th April 1938. I am extremely obliged to you for informing me that you propose to return to Allahabad and shall probably be there for the greater part of April and suggesting that, if it would be convenient for me to come there, we could meet, or, if it suits me better to go to Lucknow, you will try to go there. I am afraid that it is not possible for me owing to my other engagements, but I shall be in Bombay about the end of April and if it is convenient to you, I shall be very glad to meet you.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah

It seems to me that you cannot even accurately interpret my letter, as you very honestly say that your ‘mind is obsessed with the international situation and the terrible sense of impending catastrophe that hangs over the world’, so you are thinking in terms entirely divorced from realities which face us in India. I can only express my great regret at your turning and twisting what I wrote to you and putting entirely a wrong complexion upon the position I have placed before you at your request.

As to the rest of your letter, it has been to me a most painful reading. It seems to me that you cannot even accurately interpret my letter, as you very honestly say that your ‘mind is obsessed with the international situation and the terrible sense of impending catastrophe that hangs over the world’, so you are thinking in terms entirely divorced from realities which face us in India. I can only express my great regret at your turning and twisting what I wrote to you and putting entirely a wrong complexion upon the position I have placed before you at your request. You have formulated certain points in your letter which you father upon me to begin with as my proposals. I sent you extracts from the press which had recently appeared simply because I believed you when you repeatedly asserted and appealed to me that you would be grateful if I would refer you to any recent statements made in the press or platform which would help you in understanding matters. Those are some of the matters which are undoubtedly agitating Muslim India, but the question how to meet them and to what extent and by what means and methods, is the business, as I have said before, of every true nationalist to solve. Whether constitutional changes are necessary, whether we should do it by agreement or conventions and so forth, are matters, I thought, for discussion, but I am extremely sorry to find that you have in your letter already pronounced your judgment and given your decisions on a good many of them with a preamble which negatives any suggestion of discussion which may lead to a settlement, as you start by saying ‘I was somewhat surprised to see this list as I had no idea that you wanted to discuss many of these matters with us; some of these are wholly covered by previous decisions of the Congress, some others are hardly capable of discussion’, and then you proceed to your conclusions having formulated the points according to your own notions. Your tone and language again display the same arrogance and militant spirit as if the Congress is the sovereign power and, as an indication, you extend your patronage by saying that ‘obviously the Muslim League is an important communal organization and we deal with it as such, as we have to deal with all organizations and individuals that come within our ken. We do not determine the measure of importance or distinction they possess,’ and then you mention various other organizations. Here I may add that in my opinion, as I have publicly stated so often, that unless the Congress recognizes the Muslim League on a footing of complete equality and is prepared as such to negotiate for a Hindu-Muslim settlement, we shall have to wait and depend upon our inherent strength which will ‘determine the measure of importance or distinction it possesses’. Having regard to your mentality it is really difficult for me to make you understand the position any further. Of course, as I have said before, I do not propose to discuss the various matters, referred to by you, by means of and through correspondence, as, in my opinion, that is not the way to tackle this matter.

Your tone and language again display the same arrogance and militant spirit as if the Congress is the sovereign power and, as an indication, you extend your patronage by saying that ‘obviously the Muslim League is an important communal organization and we deal with it as such, as we have to deal with all organizations and individuals that come within our ken. We do not determine the measure of importance or distinction they possess,’ and then you mention various other organizations.

With regard to your reference to certain falsehoods that have appeared about the Congress in the Urdu press, which, you say, have astounded you, and with regard to the circular letter referred to about the misdeeds of the UP Government, I can express no opinion without investigation, but I can give you [a] number of falsehoods that have appeared in the Congress press and in statements of Congressmen with regard to the All-India Muslim League, some of the leaders and those who are connected with it. Similarly I can give instances of reports appearing in the Congress press and speeches of Congressmen which are daily deliberately misrepresenting and vilifying the Muslim composition of the Bengal, Sind, Punjab and Assam Governments with a view to break those governments, but that is not the subject matter of our correspondence and besides no useful purpose will be served in doing so.

With regard to your request that our correspondence should be released to the press, I have no objection provided the correspondence between me and Mr Gandhi is also published simultaneously, as we both have referred to him and his correspondence with me in ours. You will please therefore obtain the permission of Mr Gandhi to that effect or, if you wish, I will write to him, informing him that you desire to release the correspondence between us to the press and I am willing to agree to it provided he agrees that the correspondence between him and myself is also released.

With regard to your request that our correspondence should be released to the press, I have no objection provided the correspondence between me and Mr Gandhi is also published simultaneously, as we both have referred to him and his correspondence with me in ours. You will please therefore obtain the permission of Mr Gandhi to that effect or, if you wish, I will write to him, informing him that you desire to release the correspondence between us to the press and I am willing to agree to it provided he agrees that the correspondence between him and myself is also released.

Yours sincerely,

M.A. Jinnah

These letters have been republished from Nehru: The Debates that Defined India, courtesy the permission of Tripurdaman Singh and Adeel Hussain. You can buy the book here.

Jawaharlal Nehru needs no introduction. He was central to Indian politics both before and after Independence. He was Independent India’s first Prime Minister and went on to hold that position till his death 17 years later. His legacy as a statesman and as architect of an independent India is undeniable. While parts of it are often disputed, it continues to loom large above us all. But Nehru lives on in more than history. His written work – comprising mostly books, articles and letters – are some of the most stellar samples of Indian English writing in the twentieth century. You can read more about him here.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah was a lawyer, politician and the founder of Pakistan. He served as the leader of the All-India Muslim League from 1913 until the inception of Pakistan on 14 August 1947, and then as the Dominion of Pakistan’s first governor-general until his death. He is revered in Pakistan as the Quaid-i-Azam (‘Great Leader’) and Baba-i-Qaum (‘Father of the Nation’). You can read more about him here.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply