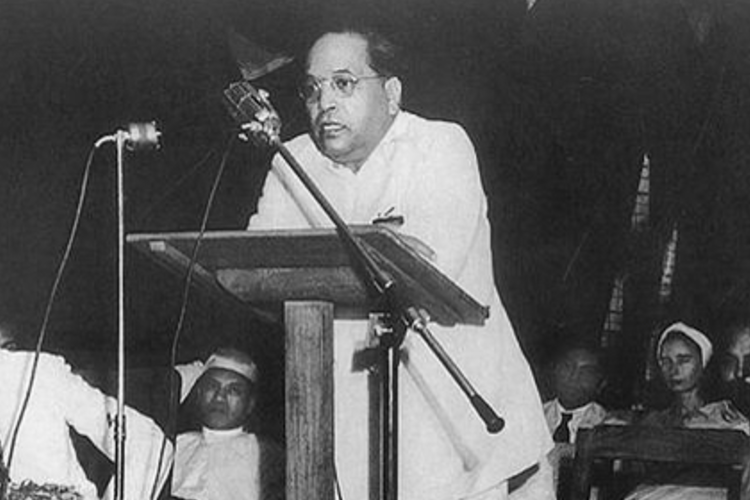

At the final reading of the bill to enact the new constitution into law, in November, 1949, Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, lovingly called ‘Babasaheb’, warned the Constituent Assembly of the dangers to India’s Constitution as well as its Independence. He also indicated a way in which this could be avoided.

It is advisable, when you’re not sure of how to deal with a great creation, to go to its source. Often enough, one is confronted with the question of ‘safeguarding’ the Constitution. What can one do? What is one’s duty? These are questions that lie nowadays on a few lips, a few minds.

One such source would be Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar’s speech to the Constituent Assembly at the final reading of the bill to enact our constitution into law, in November 1949. His prescriptions, in hindsight, seem prophetic.

The excerpt from the speech that follows begins with tracing the history of the democratic ethos to ancient India, from limited and/or elected monarchies to Buddhist Sanghas. Then, Ambedkar goes on to caution against India remaining a democracy “in form” while becoming a “dictatorship in fact”.

To prevent this Ambedkar puts forward three ideas. First, interestingly, he rules out not only armed revolutions or coups but also Gandhian methods of protest such as “civil disobedience, non-cooperation and satyagraha”. Calling all of these the “grammar of anarchy”, he holds that they have no place in an India where there are “constitutional methods” to avail of. Second, he invokes John Stewart Mill to alert us to the evil of hero worship, something Ambedkar has steadfastly spoken and written against at other times as well. He quips that while “bhakti”, or devotion, may lead to “salvation” in religion, in politics it is a path to “degradation and dictatorship”. Finally, and most importantly, he stresses the need for India to be a “social democracy”, rather than just a “political” one.

Through his last prescription Ambedkar highlights two necessities. One, that we strike the right balance between “liberty” and “equality”. He posits a social liberalism that safeguards the rights of the “many” from “the supremacy of the few”, while at the same time being mindful that our quest for liberty doesn’t kill individual initiative.

But for liberty and equality to “become a natural course of things”, says Ambedkar, we will need “fraternity” or a feeling of friendship and mutual support. And this brings us to the second requirement Ambedkar points to. That liberty, equality and fraternity become the guiding “principles” of an Indian “way of life”, not mere words in our constitution or political science text books. As such, Ambedkar extends the meaning of democracy in India beyond elections and constitutional safeguards (the “political”) to an intuitive understanding and belief in the minds and hearts of the Indian people (the “social”). He seems to be drawing from the preamble of the Indian constitution to pose a question that lies at the heart of our discourse even today: We the people of India on that twenty-sixth day of November, 1949, adopted, enacted and gave to ourselves this constitution, but do we, the people of India, really understand and believe in what we have adopted, enacted and given to ourselves?

While Ambedkar doesn’t say this outright, it is evident that the responsibility for transforming India from a mere political to a social democracy falls upon the liberal elite. For only when they leave no stone unturned in spreading the message at the heart of our constitution will the principles of liberty, equality and fraternity sing in the hearts of Indian citizens, as religious hymns do today. On the day this happens we will not require, to borrow from Ambedkar, a “constable” to enforce these principles. They will “become a natural course of things”.

On the 26th of January 1950, India would be a democratic country in the sense that India from that day would have a government of the people, by the people, and for the people. The same thought comes to my mind. What would happen to her democratic Constitution? Will she be able to maintain it or will she lose it again? This is the second thought that comes to my mind and makes me as anxious as the first.

It is not that India did not know— what is Democracy. There was a time when India was studded with republics, and even where there were monarchies, they were either elected or limited. They were never absolute. It is not that India did not know Parliaments or Parliamentary Procedure. A study of the Buddhist Bhikshu Sanghas (monastic orders) discloses that not only there were Parliaments —for the Sanghas were nothing but Parliaments—but the Sanghas knew and observed all the rules of Parliamentary Procedure known to modern times… This democratic system India lost. Will she lose it a second time? I do not know. But it is quite possible in a country like India—where democracy from its long disuse must be regarded as something quite new—there is a danger of democracy giving place to dictatorship. It is quite possible for this new born democracy to retain its form but give place to dictatorship in fact. If there is a landslide, the danger of the second possibility becoming actuality is much greater.

If we wish to maintain democracy not merely in form, but also in fact, what must we do? First thing in my judgment we must do is to hold fast to constitutional methods of achieving our social and economic objectives. It means we must abandon the bloody methods of revolution. It means that we must abandon the method of civil disobedience, non-cooperation and satyagraha. When there was no way left for constitutional methods for achieving economic and social objectives, there was a great deal of justification for unconstitutional methods. But where constitutional methods are open, there can be no justification for the unconstitutional methods. These methods are nothing but the Grammar of Anarchy and the sooner they are abandoned, the better for us.

We must make our political democracy a social democracy as well. Political democracy cannot last unless there lies at the base of it social democracy. What does social democracy mean?

The second thing we must do is to observe the caution which John Stewart Mill has given to all who are interested in the maintenance of democracy, namely not “to lay the liberties at the feet of even a great man or to trust him with powers which enable him to subvert the institutions”. This caution is far more necessary in the case of India than in the case of any other country. For in India, Bhakti or what may be called the path of devotion or hero-worship, plays a part in its politics unequalled in magnitude by the part it plays in the politics of any other country in the world. Bhakti in religion may be a road to the salvation of the soul. But in politics, Bhakti or hero-worship is a sure road to degradation and to eventual dictatorship. The third thing we must do is not to be content with mere political democracy. We must make our political democracy a social democracy as well. Political democracy cannot last unless there lies at the base of it social democracy. What does social democracy mean? It means a way of life which recognizes liberty, equality and fraternity as the principles of life. These principles of liberty, equality and fraternity are not to be treated as separate items in a trinity. They form a union of trinity in the sense that to divorce one from the other is to defeat the very purpose of democracy. Liberty cannot be divorced from equality, equality cannot be divorced from liberty. Nor can liberty and equality be divorced from fraternity. Without equality, liberty would produce the supremacy of the few over the many. Equality without liberty would kill individual initiative. Without fraternity, liberty and equality could not become a natural course of things. It would require a constable to enforce them.

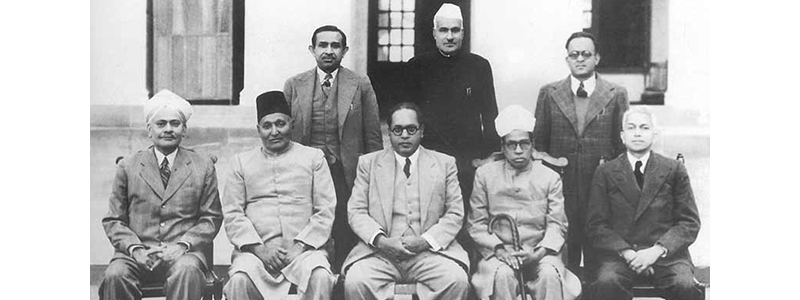

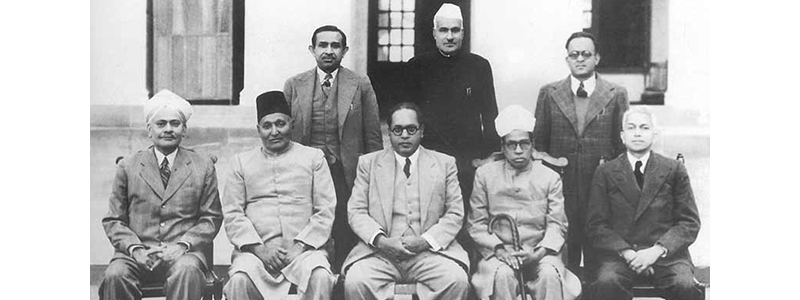

Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar can be said to be one of the foremost architects, not just of the Indian constitution, but also of modernity in India as we know it. His excellence spanned many disciplines. As a jurist, economist, political leader and advocate of social justice, he is one of the twentieth century’s most formidable minds, whose voice campaigned tirelessly, and impactfully, for Dalits and other marginalised Indians. He was also independent India’s first law and justice minister. You can read more about his life here.

[…] may do well to remember Dr B.R. Ambedkar’s last speech to the Constituent Assembly, in which he said, “If we wish to maintain democracy, not merely in form, but also in fact … the first thing in […]