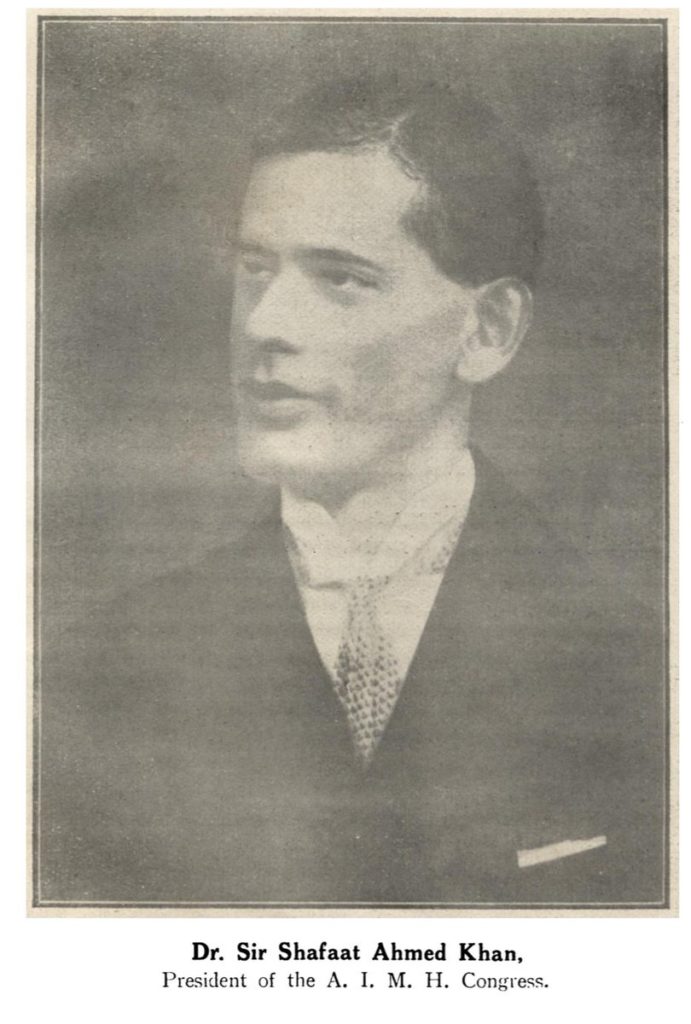

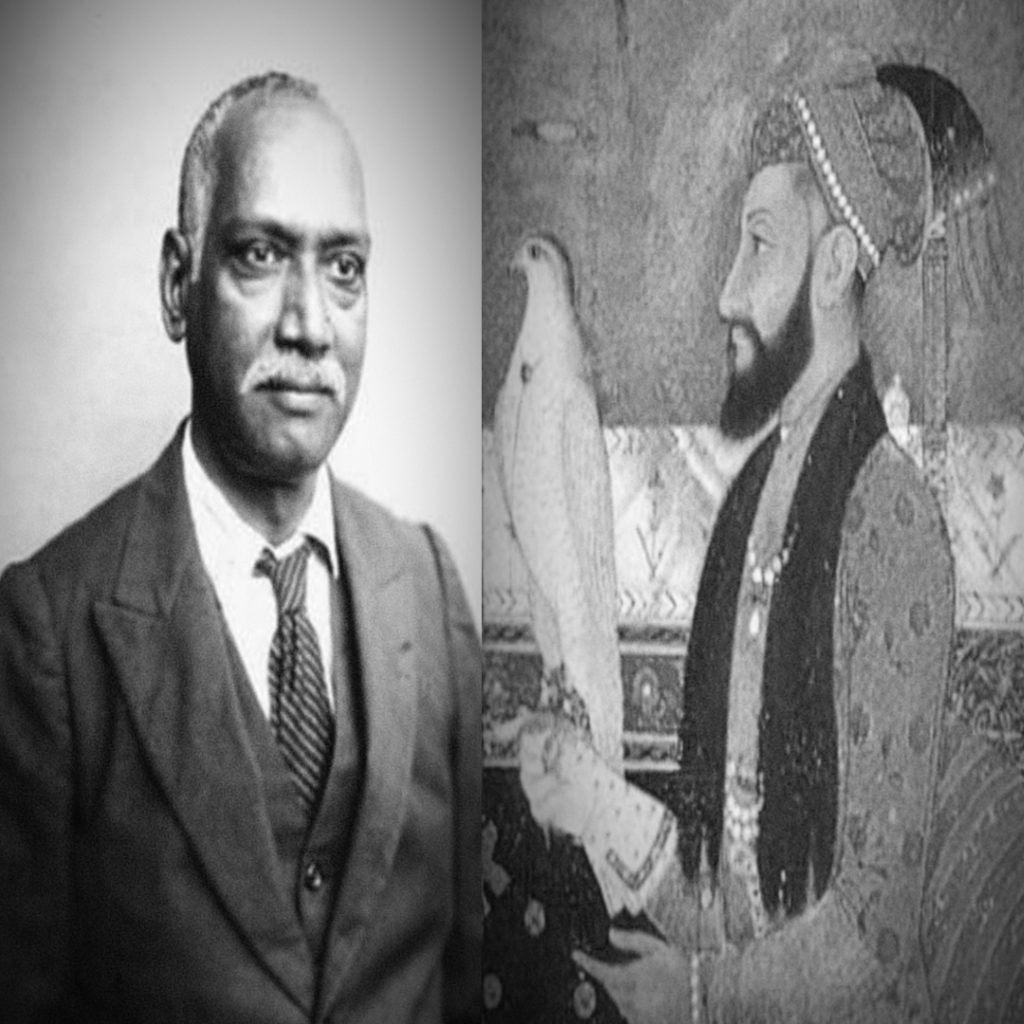

What does the ‘business of history’ entail? So many edifying books, essays and articles, and painstakingly retrieved and translated primary sources that we see and hear of, that are organised and available so that the researchers of today can stand on the shoulders of giants as well as the shoulders of the giants these giants stood on— how did they all come to be? This landmark address by Sir Shafaat Ahmad Khan, at the founding of the stalwart institution that we have come to know today as the Indian History Congress, gives us a sense of this— a holistic sense.

Sir Shafaat was not just a remarkable historian but also a remarkable personality and political figure in the first half of the twentieth century. Besides the bio we have provided at the end, you can read more about his life and career here. Sir Shafaat’s immense address from 1935, provides not just a clear idea of the Indian historyscape of the 1930s—so that we may set aside some moments to appreciate the blood and sweat of archivists, scholars and institution builders who have played a significant role in providing us with the history we treasure so—but also teachings and predictions that can serve, and may hopefully continue to serve, as crucial aids for the historian and history-lover of today.

The address has been plotted into 22 sections that take you through the workings of history as an art and a science— from the “high tradition of selfless and unostentatious research” that accompanies the collation, translation and publication of manuscript material, for instance, to the fact that “History consists, not merely in the organization, collection and examination of material, but also in its interpretation” and that “Interpretation is the core of history”.

Here below is an outline of the vast study that Sir Shafaat’s address comprises:

– the work done by the Maharashtra School of historians and the fact that “the National consciousness which found vigorous expression in the brilliant achievements of some of our foremost leaders” and “the supremacy of Maharashtra in the national movement of modern India” could be traced to this;

– he compares the work done by historians in India and abroad and their different approaches;

– historical biases and prejudices that creep in—prompted by culture (especially with regard to understanding the conflict as well as synthesis between cultures)—and objective standards they should be gauged against (the “archive method of history” without “prejudices” or “passions” but “a keen and earnest desire to seek the truth”);

– historical research being undertaken by agencies of the (British) Indian central government as well as those of princely states;

– the urgent need for coordination among various agencies and bodies;

– gaps in research and new ideas and fields that need to be explored (eg. not just a focus on political history but the histories of village organisations, religious towns and connected ideas and movements, economic history, art history etc.);

– the role of the All India Modern History Congress (which became the Indian History Congress)— especially the necessity of avoiding “history in tabloid form” and to be wary of spending an inappropriate amount of resource and energy in “tracing a particular plot”;

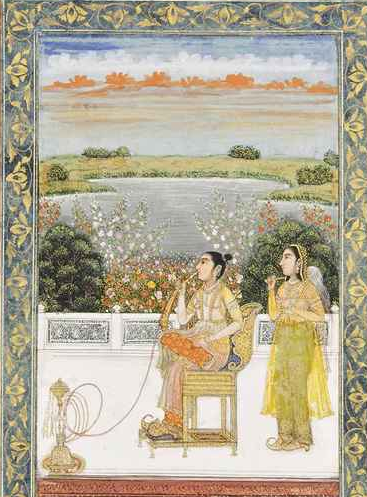

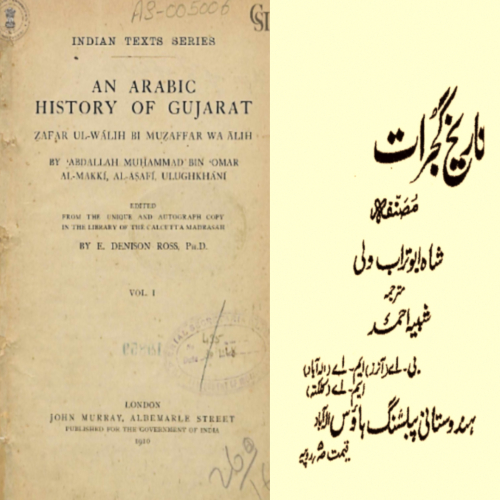

– the state of historical work on the pre-Mughal and Mughal period; the importance of context, and the need to differentiate between eulogies produced by courtiers and actual history (eg. by employing “effective correctives” via the accounts of private citizens and foreign travellers); the importance of Farmans among primary sources of history and so much other manuscript material in vernacular, which require publication and translation; the listing of voids in historical knowledge during these periods (eg. the Arab conquest of Sindh, the history of Muhammad Ghori and early Slave Kings of Delhi, the administration of Balban, Qutbuddin Aibek, Jalāluddin Firuz Khilji, Sayyid and Lodi dynasties, Humayun, a serious attempt to effect a partial separation between religion and administration during Akbar’s reign, procedure at Mughal courts, the functions of the Kotwãl, the Diwan, the Bakhshi and the Subedār, revenue administration under Sher Shah and Akbar, the relative merits of the Zamindāri and Raiyatwãri systems, Indian art, religion and social movements during the Moghul period, military history, architecture) that need to be filled with more intensive research and the role institutions can play in this;

– histories of the smaller kingdoms: Eg. the Sharqi dynasty of Jaunpur (a culture-state like medieval Brussels or Florence), the dynasties of Malwa and Gujarat, Kashmir, the medieval kingdoms of Bengal, the Bahmani Empire and its off-shoots, histories of architecture in many princely states, a new history of Rājputāna (the causes of the decay of the Rajput States in the 18th century);

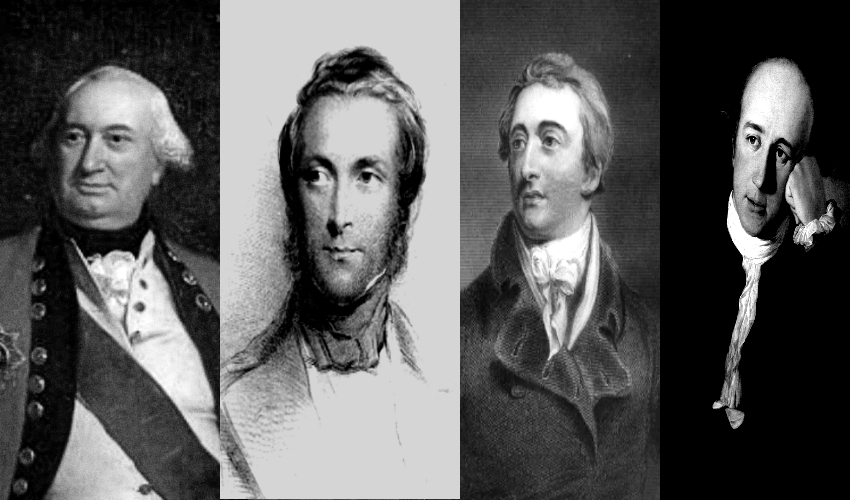

– the period of British Indian history stands “in marked contrast with that traversed so far”, due to “a mass of voluminous and prolific material, which it would be difficult to parallel in other countries”. “The reason for it is to be found in the fact that the Directors of the Company being six thousand miles away from the scene of operation were most suspicious of any departure from the minute and vexatious restrictions which they imposed on their factors.”; the histories of successive Governor Generals; the direction for further research outlined;

– The Mutiny and After: “The post-Mutiny period is too recent, and too much involved in controversies which are still going on, to be capable of dispassionate and balanced treatment. Important documents are not yet accessible; the minutes of the Governor-General’s councils must remain hermetically sealed till after a century, while the secrets of the India Office records must be closely preserved and jealously guarded for some time.”; the study of “institutions and constitutions”; tracing the relation of the Provincial to the Central Government throughout Indian history; the policy adopted by various provincial governments towards self-governing bodies within their jurisdiction; the work of the Bramho Samaj, the Arya Samaj, the Servants of India Society, etc., “still awaits historians of the ‘requisite training and breadth of view. The work should not be undertaken from a sectional point of view, but should be studied in its bearings on the spiritual growth and the intellectual progress of the people of India as a whole”; “We need competent and comprehensive histories dealing with the evolution of the present constitution, not in a spirit of gross adulation or blind partisanship, but in a spirit of steadfast, honest inquiry, conducted not with a view to any personal or political aims, but solely with the object of objective and scientific study.”

– an impartial investigation of history: “I dread the prospect of a long line of histories of India written by Muslims, Mahrattas, Sikhs, Bengalis and Pathans, each from his own point of view, denouncing things, measures and governments with which such writers are in disagreement, in a language of license, with the rancour and vigour of professional scribblers. Such a contingency has not yet arisen. I pray and hope that it will never arise, for if once the flood-gates of sectional histories are let loose, it would be quite impossible to dam them. The danger must be guarded against with all the strength at our command, in order that our national histories may be free from the incubus of fanaticism.”

– the collation and publication of manuscripts material (especially from families who have inherited such from their ancestors); the need for a manuscripts commission to undertake work of an ‘all-India character’;

– the documents at the Peshwa’s Daftar in Poona to be open to all students of history;

– the need for expert archivists, trained in the methods, under the auspices of universities;

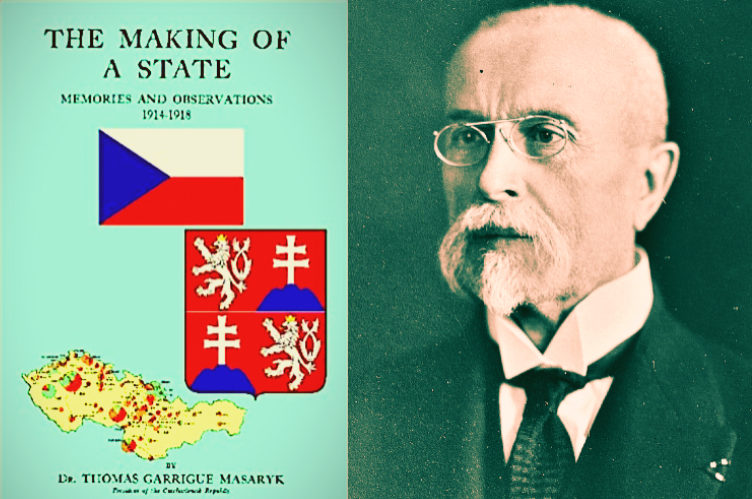

– the need for a revised edition of Elliot and Dowson’s History of India as told by its own Historians

– a list of problems with universities and their teaching of history and contribution to historical research (“Have the present Universities succeeded in organizing and stimulating research on a scale which would justify our regarding them as nurseries of learning and culture? Have they given evidence of the creative energy and brilliant leadership which even a third-rate German University has frequently shown? What progress has actually taken place in the adaptation of our Universities to the complex problems with which India will be faced in the immediate future? To what extent, if any, have the numerous problems of history referred to in this address been solved by them?”); a list of reforms suggested to address such problems;

– emphasizing the function of the Congress: “the exchange of views among scholars, the lack of which has been severely felt by many historians, will be frequent and effective, and the experience gained by researchers in other fields will be available to all, in a way which has never been possible so far”; “to give an impetus to research on an all-India basis, in a systematic and organized form, on a permanent basis, through a strong and effective organization”; Most importantly: “The All India Modern History Congress knows no politics; it will not serve the interest either of our national life and thought propagandists who paint the glories of their country’s past in a flamboyant language and consider Western influence and European culture primarily responsible for the low position which their country occupies in the society of autonomous communities, nor will it support writers who, obsessed with prejudice and racial pride, have completely ignored those features of which have maintained and preserved the continuity of our cultural life, and the stability and permanence of our indigenous institutions”; Also: “The Congress is not the forum for the dissemination of theories of racial supremacy or political predominance, and nothing can be or is more fatal to the healthy formation of sound opinion on the history of India than the manipulation and distortion of facts of history to serve the ends of political parties in the country. It is exclusively intended for scholars of history, and to the brotherhood of historians the controversies of the day make no appeal”;

– a new Indian nationalism and where Indian historical research and interpretation fits into this: “no Indian historian should ignore the broad generalisations which should underlie Indian historical research as a whole… We must not divide ourselves into watertight compartment classes of Mahratta, Sikh, Muslim, and Bengali historians. While the subject may be concerned only with a small period of Indian History, every Indian historian should aim at a conception of united India. This is the noblest and truest legacy of fifty years of rapid progress. We are not merely Mahrattas and Muslims, we are also part of a larger whole, and it is our duty as historians to emphasise this point, and bring home to the young the spiritual energy and intellectual force which impelled many of our national heroes to work, not merely for the limited and circumscribed sphere in which they moved and breathed, but also for the general progress and improvement of our Motherland.”

– further: “While history is the record of truth, and nothing but the truth, it deals with the human organism, with its passions and prejudices, its sub-conscious impulses and lofty ideals. It is a record of human activity, and is instinct with life. We deal, not with fossils, but with the achievements of persons who have left imperishable monuments of their glory in the Indian Society of to-day. The present is linked up with the past by the strongest forces in the world. It is the sacred duty of historians of India to attempt the interpretation of her annals in a way that is in harmony with the basic conception of her common nationality. This does not and ought not to involve importation of our modern theories into the solid mass of material concerning small and limited periods of history. All that it implies is that, the spirit in which we undertake this task must be entirely different from that which has unfortunately disfigured some writings, both Indian and English.”

Manan Ahmed Asif, whose recommendation this address is, writes of it in the afterword of his book The Loss of Hindustan – The Invention of India. Here are excerpts from the same:

“One of the most searing examples of a historian confronting a despairing unfolding reality is the address given by Shafa’at Ahmad Khan at the inauguration of the first national gathering of Hindustani historians…

“Shafa’at Ahmad Khan, in his inaugural presidential address to the assembled historians, cautioned that ‘history has not yet attained the status of an exact science,’ that it was neither Euclidean nor Newtonian, and, in fact, ‘the Hegelian conception of history, when applied to the concrete facts of Indian development, will make moral shipwreck of most traditions and ideals.’ Shafa’at Ahmad Khan, was less convinced that European sciences, or even colonial rule, would be the necessary salve for healing the subcontinent into an utopia. In fact, he saw grave dangers ahead, based on the recent histories of ‘perverted sectionalism,’ as he put it. These histories were creating ‘a gross prejudice,’ one that historians could not ignore or fail to confront.

“He spoke about the great moral calamity facing the subcontinent and how quickly the narratives of separation would move from books to the market: ‘I have been watching the onset of this disease for some years and I can no longer remain silent. It has a far-reaching effect on the future of our entire political structure, for the ideas that take root in the formative and impressionable years of youth are difficult to dislodge, and the prejudices of worthless history text-books are imported into the Council Chamber, the market place and the public platform.’ With the future of the political structure at stake, Shafa’at Ahmad Khan asked his fellow historians to ‘decide on the launching of a campaign that will clear up the miasma of suspicion, insinuation and downright untruth, which is served up as history to the virile and hardy youth of India.’ He wanted historians to reject any ‘fixed idea’ (namely, Muslim outsider-ness to the subcontinent) and not to ‘devote years to the elaboration of our curious prejudices and sub-conscious impulses.’ Instead, he argued that the Indian historian ought to take the ‘slow but difficult task of conscientious and honest investigation of elusive material.’ He imagined a critical role for the gathered historians. He asked them to function as a guild, to ‘perform the function of an Academy and regulate the standards [of historical writing] with strenuous vigilance and scrupulous honesty…

“Yet, across the subcontinent we now confront a crisis of the past, with an explicit understanding of difference as destiny. The majorities of the subcontinent have accumulated power to govern, and they have condemned the minorities to be marginalized or to be expunged. The majoritarians believe that this current state of exception, where one’s religion and linguistic heritage determine belonging and exclusion in Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh, is the rule. The majoritarian Sunni or Hindutva projects ask that we, as historians, consider them inevitable and immutable. Yet, this cannot stand. It is instructive for us to reengage with the urgency with which Shafa’at Ahmad Khan laid out the collective intellectual project facing the colonized historian, in 1935. While we face differently articulated versions in majoritarian readings of the medieval, we ought to recognize the same sense of despair, the same urgency to take collective action in the face of majoritarian claims on the past.”

And this, too, is a key reason why this critical, if lengthy, address must be read.

Manan Ahmed Asif, Associate Professor at Columbia University, is a historian of South Asia and the littoral western Indian Ocean world from 1000-1800 CE. His areas of specialization include intellectual history in South and Southeast Asia; critical philosophy of history, colonial and anti-colonial thought. He is interested in how modern and pre-modern historical narratives create understandings of places, communities, and intellectual genealogies for their readers. He has written the books The Loss of Hindustan: The Invention of India, A Book of Conquest: The Chachnama and Muslim Origins in South Asia and Where the Wild Frontiers Are: Pakistan and the American Imagination. He is also the founder of the blog Chapati Mystery which explores “the histories and cultures of Hindustan”, and co-founder of Columbia’s Group for Experimental Methods in Humanistic Research. You can read more about him and his work here.

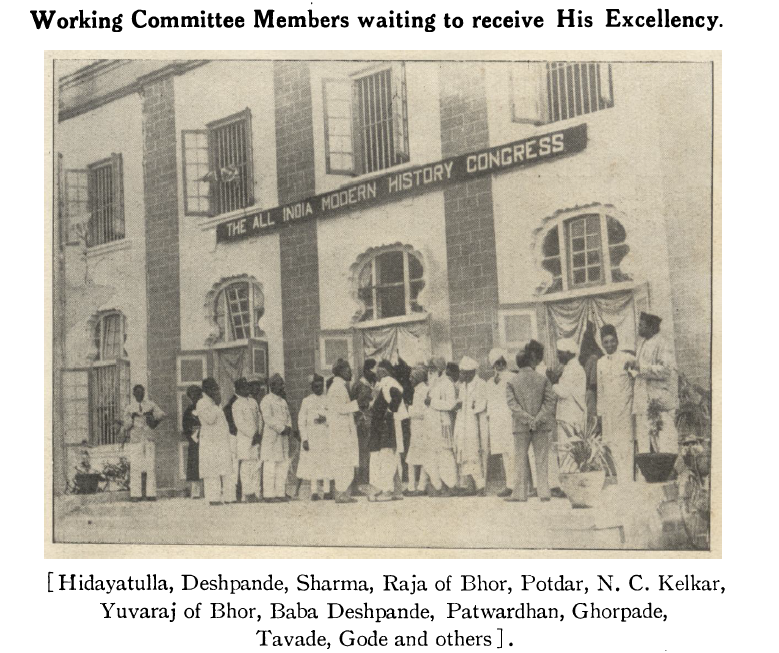

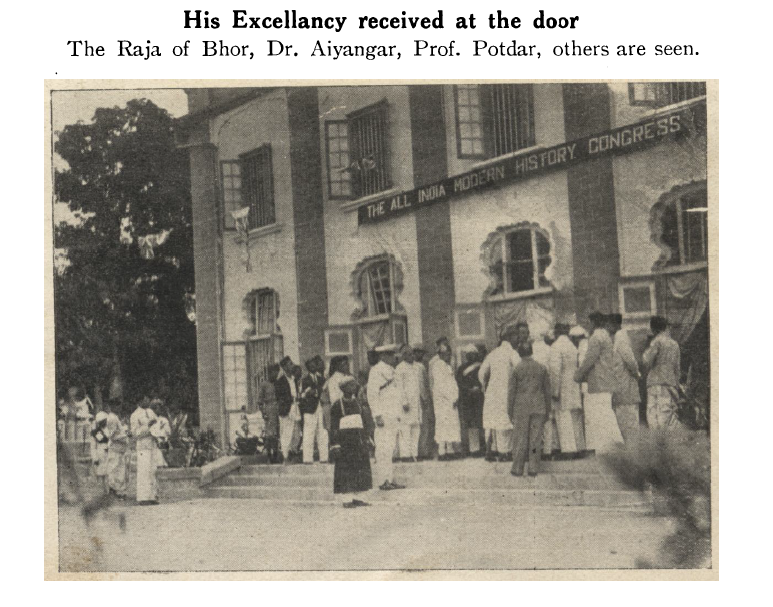

Your Excellency, Raja Sahib of Bhor, Ladies and Gentlemen,

I am deeply grateful to you for the honour you have conferred upon me by asking me to preside over the deliberations of the All India Modern History Congress. I feel that I am the least worthy of this honour, as the little work that I have attempted, in a limited field of Indian History, does not entitle me to the presidentship of a body, wherein are gathered together all the brilliant intellects of a wonderfully virile and progressive province, where intellect and character are so happily blended and poised, that it is difficult to mark off a scholar from a man of action. Maharashtra has always struck me as preeminently the territory wherein the noblest and choicest gifts of mind have served the highest and truest ends of prudent statesmanship and far-sighted reforms. The names of Rânadé and Tilak conjure up visions of intellectual giants who did not lay aside their pens in the vigorous and strenuous pursuit of political and social endeavour. One could go farther back and recall scholarly Peshwas and their learned advisers laying aside for a moment—but only for a brief though exciting interlude—their sustained and laborious researches into abstruse studies, and planning either the conquest of my own home-land, the Rohilkhand division in the United Provinces, or the administration of a mighty province is North India. I do not indulge in a vein of mock modesty when I state that I find myself singularly disqualified for the onerous responsibility which your kindness and indulgence have laid on my shoulders. As you have been kind enough to confer this honour on me, I will try to discharge my obligations to the best of my limited ability.

Ladies and Gentlemen, The All India Modern History Congress owes its birth to the foresight and energy of a band of brilliant scholars in Maharashtra, who conceived the idea of organizing a body that will serve as the focus of Indian historical research, by which the unconnected and uncoordinated researches, which are being prosecuted in different parts of India, will be systematised and duly arranged. It will be an authoritative organ of historical scholarship, imbued with the principles which have made history in the West almost an exact science, and guided by canons which are acknowledged to be essential for the objective and scientific study of this subject. The object is one with which every scholar will sympathise, and I have no doubt whatsoever that this lusty baby, fondled with the paternal care and affection, which only the Maharashtra people know how to bestow, will develop into a powerful and vigorous individual, with a tremendous capacity for hard and laborious work, and a graceful plasticity, characteristic of the true child of Maharashtra, capable alike of assimilating new material and initiating new enterprises. The need for such a body had long been felt, and historians in the north, no less than in the south of India, had constantly pressed for the establishment of such an institution. In my own province, researches are carried on by the Universities of Lucknow, Allahabad, Benares, Agra and Aligarh and there are some very promising students in these Universities, with a record of original work which will compare favourably with that conducted in other parts of India. In Bengal, the Calcutta Historical Society, the Asiatic Society of Bengal, and the Universities of Calcutta and Dacca, have published works of an exceedingly high order, throwing new light on some of the most obscure and gloomy recesses of our national story. Madras has not lagged behind, and the Universities and the Societies there have vied with each other in the production of monographs which are of the highest value for the study of South Indian History. In the Punjab, thanks to the wide and tactful guidance of a highly cultured and scholarly Governor, Sir Edward Maclagan, the Punjab Historical Society has published a series of monographs of the highest value to the students of the history of Northern India, and the Punjab University has organized inquiries into problems which have abiding value and interest to the Punjabees. These achievements, however, pale into insignificance in comparison with the great and lasting work which the Maharashtra school of historians has accomplished. The Maratha intellect, keen as a Sheffield blade, and as practical as a commercial traveller, found the greatest and purest expression of its ideals and aspirations, its traditions and achievements, in the systematic and orderly arrangement of the sources of its national history, the solid and painstaking researches conducted with German thoroughness, and inspired by burning enthusiasm for the glorious annal of their forefathers. It was not the work of Dry-as-Dusts, burning midnight oil over unfamiliar and scraggy material, and wading wearily through a mass of incongruous lumber. It was a work of piety and devotion, which knit up every fibre of national life, and served as inspiration to a generation that threatened to forget the clamant and insistent demands of tradition, in its eager desire to swallow the varied fare of western culture which had been temptingly placed before it. The work done by the historical school of Maharashtra is a land-mark in our National History. To it may be traced the National consciousness which found vigorous expression in the brilliant achievements of some of our foremost leaders – Tilak and Rânadé – and from it were derived the basic conceptions which changed the entire outlook of India as a whole. History on this, as on other occasions, served as a beacon to many a brilliant youth, and the supremacy of Maharashtra in the national movement of modern India was a clear and decisive sign of the signal triumph of the pioneers of the Maharashtra renaissance. The only true test of ability in a man is action, taken in its widest sense, and the Maharashtra School succeeded precisely because it combined an infinite capacity for taking pains with a peculiar aptitude for action. Into the dry bones oř history, and the musty worm-eaten parchments, was infused a life which has changed the structure of Indian thought and action. The work done by the Bharat Itihas Samshodhak Mandal has elicited warm praise from every historical scholar, and no student of seventeenth, eighteenth or nineteenth century Indian history can afford to ignore it. It is of supreme value to students of modern Indian history, and India owes a debt of gratitude to the men who have worked unostentatiously, for a number of years, and placed the history of the Mahratta people on a secure and firm basis. Mention may be made, in this connection, of the researches conducted by the Bombay branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, the Historical Research Institute of St. Xavier’s College, and the works of Hodiwälä, Modi and others.

Top L to R: Historical Research Institute of St. Xavier’s College; Bharat Itihas Samshodhak Mandal

Bottom L to R: Bal Gangadhar Tilak; Mahadev Govind Ranade

I have given this brief survey to show that a great deal of research work is being carried on in different parts of India on various periods of Indian history. Necessarily, it is a work of varying degrees of importance. In some cases, where supervision and guidance have been effectively exercised, the results have been excellent. It can compare favourably with the products of some of the best and most authoritative treatises in Germany or England. The data have been carefully sifted, conclusions have been tentatively drawn, and the apparatus of historical criticism has been applied with due regard to the nature of the material and the atmosphere of the period. On the other hand, several works have been published lately, in which racial bias is so palpable and gross, that no historian can approve of them. They are appallingly partisan and partial. I do not think that such cases are peculiar to India. On the contrary, you find examples of it throughout the world, where each new Dictator commandeers Universities and schools and orders the writing of history according to the strictest principles and practice of his theories. I have not read many books on the history of Mexico during the last sixty years, but I imagine that it would be extremely difficult, if not impossible to carry on researches into Mexican history with complete impartiality and publish a history of Porforio Diaz during the volcanic eruption of the Carranza regime. Such ebullitions of national frenzy are not uncommon, but modern India, it must be confessed, has hitherto been singularly free from the insidious pressure which reigning potentates and dictators bring to bear on the historians of their countries. It would be difficult, if not impossible, to find impartial and scientific history in any of the works published in modern Germany or Italy. The danger however is real, and Indian historians must be constantly on their guard against the temptations to which they are peculiarly liable. In the case of European countries, the process of centralisation and unification has levelled down all barriers of provincial and even racial prejudices, and the nation thinks as one man. There government is natural, legitimate and genuinely representative of every phase of national life. Literature, art, education, culture in its widest and most comprehensive sense, are a source, not merely of a creative energy, but of the initiative which even a third-rate power in Europe constantly calls forth. They serve as the most effective instruments for the consolidation of national unity and racial self-consciousness. Society there is more powerful than Government, as society contains, in its varied and variegated strata, elements which are constantly nourishing and vitalising almost every channel of Government. National drama and national festival, which have invariably been regarded as the most potent agencies for the propagation of national spirit and the creation of national unity, occupy a place, in the highly centralised States, whose value and work are justly appreciated by every Government. In India, private agencies and institutions carry on this work perfunctorily, without effective guidance or farsighted supervision. I have not adduced these facts for the purpose of advocating bureaucratic control, nor is it my desire to extend the range of Government over spheres of our national life which have been wisely left to private individuals. These examples have been given solely with a view to showing the great difference between the position of the Indian historian and that occupied by his fellow-investigators in other countries. The history of our motherland may be conceived either as a record of continuous deterioration of intellect and character, with a few happy interludes, or it may be regarded as the orderly, slow development of the Indian people through centuries of confusion and disorder. Neither view would, in my humble opinion, be correct. There are no immutable laws ordaining the development of any people by fixed and regular stages. History has not yet attained the status of an exact science, and human motives and natural forces, which constantly act and react, cannot be calculated in a mathematical form with the precision and rigidity of a Euclidean proposition. The Newtonian equipoise, which some historians take for granted in the fascinating pursuit of mathematical and scientific inquiry, is a clear indication of the necessity of guarding against ideas, imaginatively conceived, by a continued process of make-shift in policy seeking to cover itself by the make-believe of verbiage. This theory of the science of history identifies the real with the ideal and, carried to its logical limits, it will make every stage in our national history the realisation of the highest moral ideal. The Hegelian conception of history, when applied to the concrete facts of Indian development, will make moral shipwreck of our most cherished traditions and ideals, and condemn us to a Pharisaical defence of the most iniquitous acts perpetrated by some of the worst tyrants in some parts of India during the last one thousand years. It surely is not necessary, either for the efficacy of our new-born zeal for “evolutionary history”, or for the application of some fanciful scheme conceived in moments of frenzy, to champion fervently a doctrine which is historically inaccurate and morally indefensible.

What then should be the attitude of historians in India? Should they roll up like a scroll events that have moulded the fate of millions of persons during the last one thousand years, and treat everything that has occurred since as an unfortunate incident in the chequered annals of our country? Are the glories of Akbar and the flowering of our racial self-consciousness in the Konkan valley, in the land of the five rivers, as well as, in the scorching torrid plains of Hindustan and Rajputana, to be relegated to the limbo of oblivion? Can we start with a clean slate and try to construct a Utopia, wherein the Indian world of to-day would be drastically remade? I have put these questions in the boldest and crudest form, in order that the position which Indian historians ought to occupy should be made clear. The historian of India is presented with difficulties which are without a parallel in other countries. We have, at one and the same time, two mighty cultures, existing side by side, working irresistibly, by the sheer force and momentum of their existence, into the very nerve and fibre of their respective adherents. A conflict is inevitable whenever culture is armed with power, and the conflict goes on with complete disregard of the genuine merits of the rival cultures. Clashes occur with startling frenzy and ferocity. The opprobrious expressions regarding the Hindus, which Amir Khusrau uses in his Khazāinul Futuh, can be paralleled by some passages in the writings of many an author in South India. It seems at first, that contact is impossible, and toleration, which has been incorporated in the pattern of our ordinary life, is out of question. Gradually, however, we find emerging a feeling of appreciation, crystallizing ultimately into a synthesis of Hindu and Moslem cultures. This reached its fullest and perfect development in the reign of our national king Akbar the Great. We find a number of Moslems in his reign who had attained considerable proficiency in Sanskrit. Al Beruni led the way and was followed by numerous others. Maulana Izud-dia-Khalid Khani was ordered by Firoz Shah to compile a work on philosophy which he called Dalayal Firoz Shahi. In the reign of Akbar we have Faizi, Abdul Kadir, Nakib Khan, Mulla Shah Muhammad, Mulla Shabri, Sultan Haji, Haji Ibrahim and many others. In Bengal, Muslim savants and rulers devoted their life to the propagation of indigenous culture. The Hindus particularly the Kayasthas, Khatris and Kashmiris, attained a mastery of Persian, and even Arabic, which was hardly inferior to the skill and knowledge displayed by the Muslims in their own languages. The two cultures, as well as the two races coalesced, for all practical purposes, so far as the interests of the State were concerned and we attained a conception of a common nationality which worked with irresistible force in the palmy days of the Mughal Empire. I am not competent to speak of the South, but I believe I am correct in saying that the movement in the South, too, ran pari passu with that in the North. During the strife of cultures as well as of governments it was inevitable that the two races should express their hostility in their writings. History never speaks with two voices; but in the case of some historians there is such a chasm that it is difficult to arrive even at an approximation of truth, if we read only one version. The Muslim historians of the reign of Aurangzib could not, and did not, look on the life and achievements of the great Maharashtra hero, Shivaji, with the same feeling with which he was regarded throughout the length and breadth of the Maharashtra. We must not overlook real difficulties by simply shutting our eyes to them or deliberately ignoring them. We have to admit the fact that it is difficult to assess the real merit of a policy or of a ruler, whether in Northern or Southern India, if we confine our gaze solely to the partial, blurred and, in some cases, perverted accounts of partisan writers. Objective history is impossible if the tales told by credulous, intolerant and fanatical adherents of either side are served up as a sober recital of authenticated and true facts. The same spirit runs through many of the histories written during the mediaeval period of Indian history. Writers who supply accurate data are exceedingly rare, while panegyrists, courtiers, bards and persons intoxicated with religious frenzy abound. The Indian historian must, therefore, guard himself against the risks to which this conflict between the two cultures peculiarly exposes him. The history of Germany, France, England and other organized States is comparatively simple, as the differences that divided the Parisian from the Norman, the Gascon from the Breton, have completely disappeared, and there is only one country with which a French historian is concerned, La Belle France. In Germany, the quarrels between the Guelf and Ghibelline, between the Prussian and the Bavarian, are completely forgotten, and we have now a steam-roller constantly at work, levelling down all provincial, racial and class barriers. In India we have not arrived at a stage when the differences of religion could be completely ignored in our treatment of controversial periods of Indian history. It may be confessed, and I do so quite frankly and without the least hesitation, that the history of the Punjab from 1780 to 1848, the history of the Deccan from 1670 to 1730, the history of Bengal from 1756 onward, the entire administration of Lord Dalhousie, and the whole reign of Emperor Aurangzib, have been written with a certain bias, and there is a close, if not exact, resemblance in spirit and method between the histories of Ireland in the 17th and 18th centuries, and the monographs, brochures and forbidding tomes on those critical and controversial periods of Indian History. There are some European, Hindu, and Muslim historians who have risen above the narrow and limited confines of prejudice and passion and have furnished a wonderful example of impartiality which it behoves every one of us to imitate. Could we not give a lead to the rest of India by purging our minds of the gross prejudice which hampers at every step the orderly progress of an art which, with all its imperfections, is the supreme art for the statesman, the patriot and the student? Should history be tied to the chariot wheels of perverted sectionalism, deriving its strength from a mass of passionate material, which may have been useful during the time it was written, but is now acting as a most serious obstacle to the growing nationalism of India as a whole? Could we not decide on the launching of a campaign that will clear up the miasma of suspicion, insinuation and downright untruth, which is served up as history to the virile and hardy youth of India? Are the foundations of national unity to be undermined by the insidious statements of a third or fourth-rate penny-a-liner, who serves his own ends and lines his pockets by catering to the lowest and basest instincts of racialism, and holds up to ridicule and contempt persons, whether Hindu or Moslem, who are honoured and respected by millions in this land? I have been watching the onset of this disease for some years and I can no longer remain silent. It has a far-reaching effect on the future of our entire political structure, for the ideas that take root in the formative and impressionable years of youth are difficult to dislodge, and the prejudices of worthless history text-books are imported into the Council Chamber, the market place and the public platform. Let me make an appeal, not merely to the professional writer of school text-books, but also to the historical scholar himself, to whatever locality or sect he may belong. While a search for truth must be carried on without the least regard for personalities, and our researches must be conducted in an atmosphere of complete impartiality, Indian historians should aim, not at emphasizing or accentuating differences, but discussing that subject from the point of view solely of research. History is not propaganda, nor is it publicity. It avoids Hollywood and its film fans, its super stars and budding stars etc. It is a cold dispassionate examination of records, conducted in a spirit of severe impartiality and complete neutrality, and a careful deduction of conclusions from the material that has been rigorously sifted. It is essentially the archive method of history that appeals to me and to historians in general. We do not start with a fixed idea and devote years to the elaboration of our curious prejudices and sub-conscious impulses. In objective history there are neither prejudices nor passions, but a keen and earnest desire to seek the truth, and a mind which, braced up for the laborious task, is always open, frank and impartial. This is the attitude of a historical researcher, and I am confident that I am voicing your feelings when I say that this is the object at which Indian historians ought to aim.

L to R: Al Beruni (imaginary rendition); Portrait of Faizi

Let me complete my account of historical societies by mentioning the excellent work done by the Government of India in preserving the antiquities of this country and fostering research. I am not competent to discuss the work of the Archaeological Department, nor does it come within the purview of this Congress. But I feel that the striking work carried on by the Indian Historical Records Commission ought to be gratefully acknowledged by all scholars. It may not be great in bulk, but it is certainly great in promise and greater still in the unique facilities for mutual exchange of views and heart-to-heart discussion, which the meetings of the Indian Historical Records Commission generally provide. As one who has been a member of that body for a number of years, I can say without any hesitation that the inspiration which most of us drew from a concourse of brilliant men, whose names are a household word throughout India, the momentum which such gatherings produced, were of the highest value in fostering a spirit of camaraderie among members of our craft. The Commission has undoubtedly done good work and, if financial stringency had not proved the main obstacle, it would have done much more useful work during the last three years. Mention may also be made of the reports of the Archaeological Department, as well as memoirs published by them at various periods. Some of the memoirs have been written with special knowledge and deserve careful study by students of Muslim art and architecture. Local Governments have not been idle, and both the Bombay and Madras Governments have published very useful calendars and press-lists on the 17th and 18th century. The Madras Records Office was reorganized by Mr. Dodwell with great care and interest, and the publications issued from there have been of the greatest value to students of British Indian History. The Punjab Government has also published selections, while the lists published by the Bengal Government have supplemented, in material particulars, information at our disposal.

I cannot speak of many States from personal knowledge but, as one who toured through and inspected the Libraries and Record Offices of Gwalior, Jodhpur, Udaipur, Indore, Jaipur and Hyderabad Deccan, I can say without hesitation that the material preserved in these States is of the highest value. Some States have developed Record Offices with great care and attention, but it will be very invidious on my part to single them out here. Historical research is, however, considerably hampered in some States, and investigation into the origin and foundation of the new States that have arisen over the debris of old kingdoms or empires is by no means relished by certain rulers. Apart altogether from this aspect, it must be conceded that a number of Indian States have co-operated whole-heartedly in the process, while there are a number of rulers whose devotion to the history, culture, and art of their country is unrivalled in India. The President of the Reception Committee of this Congress is a shining example of the ruler of a State, who combines in his person devotion to culture and fostering care for the material welfare of his subjects. In a movement for the organization of historical research the cooperation of Indian States is absolutely vital.

Ladies and Gentlemen, from this brief analysis of existing Societies it is clear that there is in India a vast amount of unorganized material, and considerable work is being done on important periods of Indian history by Societies and by the provincial and central Governments. I have not mentioned here the labours of private individuals who have carried on their researches without any special aid from organizations. Their number is fairly large and some of them are still happily with us. I may also refer here to the work in Indian History by European savants and scholars. It is a work of special value to us, as it represents the ripe scholarship, the balanced view and dispassionate judgment of a group of men who can truly be called pioneers in their respective fields. A tradition of scholarship was built up by the early English administrators of India, and it was maintained and even enhanced by some who combined rare intellectual gifts and critical acumen with great practical insight and administrative capacity. If we take into account the work of the institutions mentioned above, together with the treatises published by numerous writers, it will be found that the amount of material at our disposal is sufficiently vast. But most of this work is uncoordinated. Each organization is working entirely in its own sphere, and is completely out of touch with the work, the needs and requirements of other bodies. There is not even informal contact with institutions inter se, and this chaotic and confused state of affairs has gone on for a considerable period. In ancient Indian history, the Government of India wisely took the lead, and, under the fostering care of its enlightened guidance helped by the active zeal arid energy of a number of Indian Universities, there is an amount of unity in the organization of this subject which is sadly lacking in modern Indian history. The lack of any co-ordination has rendered it almost impossible for researchers in various periods to keep abreast of the researches of other workers in their own country. In Calcutta alone there are four important organizations carrying on historical research with great ability and zeal, yet there is no co-ordination among these bodies. The Universities are the foundry in which investigations are normally carried on, and it is through them that the young carry on the torch of learning and illumine the dark recesses of the National story throughout the four corners of the world. Strange to say, there is no co-operation even among Indian Universities in the domain of research, and research scholars in different Universities are ploughing their lonely furrow utterly oblivious of the quality or quantity of work conducted by their contemporaries in neighboring institutions. This disorganization has become almost a scandal, and the worker in the field has to create for himself the most rudimentary and elementary material, sometimes with the crudest devices, and prosecute his study in an atmosphere of uncertainty and vagueness. It is only through journals that he comes across workers on his subject in other fields, and then only if he cares to order the journals and accumulate, after considerable trouble and expense, the scattered material. This is not an atmosphere in which research can be profitably prosecuted, nor is the spirit created by discouraging conditions sufficiently strong to resist the tendency towards immature and unsatisfactory work.

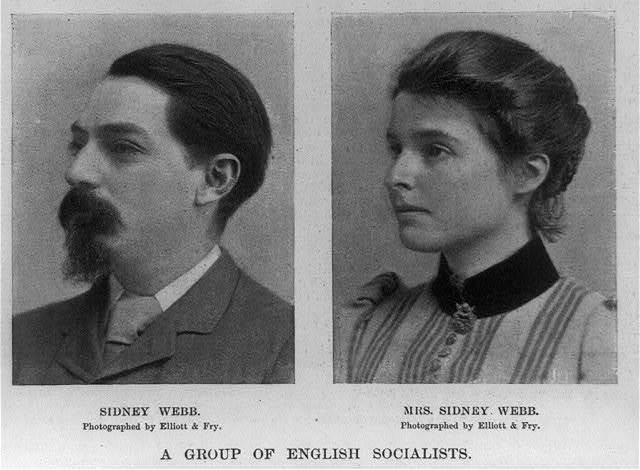

Our preoccupation with the purely political history of India is responsible for the most unfortunate conception of Indian Society, and trite and mechanical repetition is often indulged in, for instance, to illustrate the anarchy and confusion in 18th century India. This would have lost a great deal of its force, if some of us had undertaken a systematic study of those fundamental bases of our national life which have acted and are still serving as sustaining pillars of Indian Society. None has seriously undertaken a scientific study of village organization in India in the 18th century, though Punchayat has acted as a most important social unit in our national development. We have had brilliant studies on the history of the English parish; while the history of the English borough has claimed a succession of able and devoted workers, whose industry has changed in a striking degree our crude and bizarre ideas of local self-government which prevailed till that time. I need only mention the honoured names of Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Webb. The German Universities are a bee-hive of industry and research, and German towns have been the subject of solid and painstaking investigations by a growing band of young and enthusiastic workers. They have carried on their work in a spirit of piety and zeal, tempered by a strong dose of sound commonsense and impartiality. England has not lagged behind other countries, and the series published in the Victoria County History represents the profound research, dispassionate judgment and provincial patriotism of some of the ablest historians of England. I have given these two examples to show the importance which historians all over the world attach to what is popularly called local history. I will not deal here with the marvellous work done by the band of economic historians of mediaeval England, Germany and France, nor can I discuss here the vigorous schools founded by these writers. We have only just begun the study of our mediaeval and ancient institutions, and it is only within comparatively recent times that such studies have been prosecuted. There are towns in India which are more sacred and evoke warmer feelings of devotion and piety than any place in any part of the world. Around them cluster sentiments alike of religion and of patriotism, and from them are propagated ideas and movements which have frequently changed the map of India. Yet there are few good histories of such towns. Bombay has, no doubt, produced some able annalists, and the long history of that graceful city has been recorded by a few brilliant writers in a few solid monographs. Calcutta and Madras have also claimed their champions, but the chequered history of Lahore is described in a dull and laborious work, while some of the most important Indian towns have remained unnoticed and unrecorded. Poona stands for the glory and splendour of the Mahratta power. It stands for the supreme part which it has played in many of the most important movements, political and social, of modern times. The intellectual virility of its citizens ought to have been expressed in a monumental work on the rise and growth of their beautiful city. Yet, I have not come across any important work in English tracing the history of this city with the wealth of detail and industry which we expect from its foremost citizens. I need not mention other towns of India. The subject opens up a brilliant vista of an unexplored field which is awaiting an energetic corps of enthusiastic workers. I have indicated briefly only one line of activity in which the energy of many brilliant and promising scholars could be engaged. But there are numerous other spheres which have been insistingly claiming recognition and admission. Economic history is almost a virgin field and the material for the subject is voluminous. The history of art is another fascinating theme for the young researcher, and, though Indian art has been dealt with, of late, by some very competent and scholarly investigators, the field for enquiry and investigation is enormous.

The All India Modern History Congress ought not to confine its activities to the dull and dreary recital of the third-rate intrigues of a worthless minister, nor should its work be restricted to elaborate researches in the vagaries of self-willed and ruthless tyrants. A man may devote his whole life tracing a particular plot. There are gentlemen who have written volumes on the Gun-powder Plot of England. Such works are, no doubt, interesting, but we shall not be justified in regarding them as history. They are simply the result of morbid curiosity and brooding melancholy, and are written to satisfy some peculiar craving of an abnormal individual. The Modern History Congress should not serve history in a tabloid form, and should discourage ephemeral and juvenile productions, the outcome of vanity rather than of industry and research, launched on the crest of a popular wave and backed by the ignorant energy and puerile zeal of third-rate scribblers. The canons of historical research must be applied without the least regard for persons or institutions, if the standards of our noble science are to be scrupulously maintained. Drama is not history, and imagination must be harnessed to the slow but difficult task of conscientious and honest investigation of elusive material and tortuous diplomacy. I have deemed it necessary to utter this warning as I have found, in the course of my wanderings, that infinite harm is being done to the dignity and integrity of our noble art. Nothing is more fatal to the advancement of research than the production of half-baked and crude history, prepared by persons whose zeal is in inverse proportion to their knowledge and judgment. The Congress should perform the function of an Academy and regulate the standards with strenuous vigilance and scrupulous honesty.

Ladies and Gentlemen, I have dealt at some length with the work of this Congress as I feel, and I am sure I am voicing your sentiments in this matter when I say that the progress of historical study in this country will depend, to a large extent, upon the direction and guidance furnished by this body. If we are able to establish our new organization on sound lines, if historical investigators in all parts of India look up to us for advice and guidance, if the work entrusted by this body to persons in whom it reposes confidence is faithfully discharged, we shall have succeeded in changing, in a very short time, our conception of the entire frame-work of Indian historical thought. A very heavy responsibility lies upon us—a responsibility of whose gravity and complexity nobody is more conscious than myself. While the responsibility is great, greater is the opportunity which such a body affords to scholars. What then are the functions of the Congress? Along what lines should its activities be directed, if the work performed by it is to be commensurate with the amount of labour involved therein? What are the main problems upon which our attention should be focused?

These are some of the questions which inevitably arise in any consideration of Indian historical problems. Before the Congress can organize its work and initiate new lines of policy, it ought to be in a position to understand the relative importance of the different epochs into which our history is conveniently divided, and evaluate the material which is the main source for the formulation of our conclusions. I do not wish to discuss here the lines of inquiry which should be undertaken, or the weight of authority and credibility which should be attached to the history written during the period. Such detailed and minute work is best reserved for a monograph or a treatise, and I should be wasting your time if I occupy myself with an elaborate disquisition, on the comparative merits of different historians. I shall, however, be failing in my duty as Chairman of this honourable and august body, if I do not indicate to you the serious gaps and lacunae in the important periods of our history and the methods by which they can be filled. I do this, because I feel that historical scholars should concentrate on a well organized movement for filling in gaps in some of the most important and critical stages of our national history. The sketch, and it is an exceedingly brief sketch, will show that there is an enormous amount of field to be traversed by us. The problems that are awaiting sound solution are so many and varied that it is difficult for any one person to solve them single-handed. Solution must come with co-operation and mutual help expressed through an organization of this kind. The sketch is necessarily brief, and is confined to points which deserve fuller study and investigation by Indian scholars. Again, in dealing with mediaeval India, I have to confine myself to Northern India, as my knowledge of South Indian languages and literature is almost nil, and is derived mainly from authorities printed in the English language, and I am not competent to speak with authority on many of the subjects which have served the starting point of some brilliant inquiries recently instituted in Southern India.

What are the chief points on which Indian scholars should concentrate in order that a correct and impartial view of our country’s growth may be formed? Let me start first with the pre-Moghul period. This is an exceedingly difficult period for we have to rely in many cases on the professional panegyrists of the Sultans, who were commissioned to write history and were bound to praise the monarch who had raised them to the exalted position of historiographers. They are histories written to order and showing, by the exuberance of their language, the pomposity of their style, and withal a sprinkling of metaphors and hyperboles and devices, of alliteration, the utter lack of balance and sound judgment on the most ordinary and commonplace actions of the Emperor. One has only to read the stilted phraseology and appalling metaphors of Amīr Khusrau to be convinced of this statement. He is a typical example of this species of historiographer. He lived long enough to serve under Balban, Kaikobād, Jalāluddin Khilji, Alāuddin Kbilji, Kutbuddin Mubarak Khilji, Khusru Shah and Ghiyãsuddin Tughluq, and bestowed fulsome praise on each and every one of them. Most of you are, no doubt, aware of the works of Khusrau, but if anybody has not read any, I will recommend Professor Habib’s translation of Khazain-ul Futuh. That will give some idea of the flamboyant language used by this writer, and bring home to many persons the difficulty, in some cases the impossibility, of constructing scientific history out of such appalling material. As a general rule, the task of compiling historical records in pre-Moghul India was entrusted to those who were under the patronage of the court, and, as it was their duty to carry out the orders of their sovereigns, it is not surprising that much of the so-called history of the period is “official” history or history written with the specific and avowed object of praising the reigning monarch and extolling his virtues to the skies. Muhammad Ufi, Hasan Nizāmi, Minhājus Siraj, Amīr Khusrau, Ziyauddin Barni, to some extent Shamsi Siraj Afif, and Yahya-bin-Abdullah were all courtiers who basked in the sunshine of royal favour. The “histories” they wrote, if not inspired by the court, were written under its influence and patronage, and there is no dearth of high-flown and exaggerated metaphors and deliberate and calculated examples of suppressio veri. The violent denunciation and unbalanced language of Ziyauddin Barni, regarding the measures and achievements of Kaikobād, Khusrau Shah and Muhammad Tughluq, shake one’s faith both in the sanity and moderation of the man, and in the sound commonsense and judgment of the historian. In order to heighten the contrast in favour of Firoz Tughlak, Ziyauddin Barni sometimes suppresses the benevolent measures of Muhammad Tughluq. If a court historian failed to discharge his duties satisfactorily, if his standard fell short of that set up by his predecessors, he was promptly relegated to the shelf.

Emperor Shah Jahän, who wished to imitate the glory and splendour of Akbar’s reign, wanted another Abul Fazl and called on Muhammad Aminai Qazwini and Tabātabāi to his aid. When they failed to realise his expectations, Abdul Hamid Lahori was appointed. The greatest example of a court historian is, however, furnished by Abul Fazl. He was, not an ordinary historiographer, with a commonplace stock of stilted phrase and appalling melaphors, and plebeian similes, but a brilliant and accomplished administrator well-versed in the practical problems of administration and dowered with a mind of singular plasticity and brilliance. The arrangements made by the great Akbar were on a scale that has rarely been attempted by any other Moghul ruler. The records of all departments were placed at his disposal, and private individuals were requested to reduce their memories and recollections of important measures to writing. The response to this appeal by the Emperor seems to have been fairly successful, and the results of Abul Fazl’s labours were embodied in his monumental work, the Akbar Nāmah and its adjunct, the Ain-i-Akbari. These two works represent an amount of labour and industry which no individual could have accomplished without the help and patronage of the court. It is a noble monument to a gracious monarch and is a mine of information to every student of history. Its treasures have been frequently utilised by modern writers, but the wealth of material which it contains has not yet been effectively tapped. Neither Babar nor Jahāngīr appointed court historians, though Mu’tamad Khan, to a certain extent, performed the functions of a historiographer. Aurangzib appointed Mumahamad Kasim and the first ten years of the Emperor’s regime are recorded in the Alamgir Nāmah. The post of court-historian then fell into desuetude, and we are henceforward forced to rely upon private enterprise.

I have necessarily compressed the material on such a vast subject, as the problem with which we are faced is an essentially practical one. What should be our attitude towards these histories? Are they to be taken at their face value? Should our history be constructed out of these panegyring prose, in which all the arts of accomplished courtiers are lavished on the production of stilted and artificial apologia? Should the political fancies of persons intoxicated with their love of hyperbole and verbosity be deemed a durable and strong foundation for objective history? My answer unhesitatîngly is, Most certainly not. We must use with the greatest caution inspired eulogies of kings who fed, clothed and maintained these courtiers. While we cannot ignore Amir Khusru, or omit to study Qiranus Sadain, Khazain-ul Futuh, Tughluq Nāmah, Nuh Sipihr, Dewal Devi Khizr Khani, we must, remember all along that we are reading chronicles of courtiers containing a small amount of solid matter and a very large amount of romance and imagination. In such works, accuracy is sacrificed to literary finish, and an event is distorted in order that the metaphor may be apt and a sentence may be rounded off with a brilliant phrase. The crude devices of appalling antitheses are mechanically employed, and the effect of elaborate and almost pyramidal piling up of metaphors, similes and hyperboles is almost suffocating. Abul Fazl is, no doubt, an exception. There is a certain fineness of contour about him, not at all gross or coarse, in the setting of silky and gaudy furnishings. The drawbacks of the other writers are made worse by their violent prejudices. The fanaticism which burns, luridly in describing the demolition of temples, or of mosques, and the organisation of a campaign, may repel a beginner at first sight, but the phenomenon is so general, the phraseology employed is so crude and mechanical that one is sometimes forced to put the question, Why does not the past decently bury itself instead of waiting to be admired by the present? History seems to look like Adonis, fully prepared for an unconscionable time in dying. But this will be a wrong impression altogether, as words had ceased to have effect on such writers. They had ceased to arouse curiosity or excite indignation, but were incorporated in the pattern of daily life and intercourse, as the characteristic expression of the tragic muse, expressing itself in high-flown phraseology and rhodomontade. Modern historians must take these factors into account in evaluating the primary sources of the Muslim period; then only will they be able to assess the value of court histories. Had it been possible for us to discard these productions and rely entirely upon the unaided and independent writings of persons who were swayed neither by court frowns and favours, nor by fanatical zeal and prejudice, the task of Indian historians would have been greatly facilitated. But we cannot and ought not to take such a course, as it will deprive us of our main source for the study of that period. We cannot utilise histories written by persons in their private capacity, as their number during the Sultanate period is insignificant. Ibn Batutah and Abdur Razzāk supply very strong and, in some cases, effective correctives to court panegyrists, and Ziauddin Barni’s glaring and violent prejudices are corrected by the comparative impartiality and shrewdness of Ibn Batutah. Razzāk’s account takes note of the conditions of the common people, the customs and traditions of various classes, while the court of Vijayanagar is described in a series of inimitable chapters, which throw considerable light on the achievements of that empire. Unfortunately, there are few other books which could be added to the small list of foreign travellers, and we are forced to rely upon the unbalanced and distorted account of court historians. In the discussion and analysis of court history we must distinguish between histories and histories. There are some works of the highest value to the student and few scholars can afford to ignore them. No student of Moghul India can remain ignorant of Abul Fazl’s masterpiece, while the student of Shah Jahān and Aurangzeb has to study with close and sustained attention the histories written by the court historians. Moreover, during the Moghul period we have works written by private persons, which are of the highest value. Mullah ‘Abdul Kãdir Badauni is not an impartial writer as the style of the book and the temperament and expressions of the historian will show. But he supplies a much needed corrective to the fulsome eulogies and gross flattery of his rival Abul Fazl. Badauni’s style is trenchant, vigorous and clear, and in his history he has struck an entirely new line by castigating some of the innovations of the ruling king, and subjecting them to a barrage of very keen criticism. The Memoirs of Gulbadan Begam, of Jauhar, Bãyazld, Wàqiãti Mushtaqi, Wikaya-i~Asad Beg, Amal-i-Sāleh of Muhammad Salih Kambu, the Muntakhab-ut Tawarikh, the Tabaqati Akbari of Nizāmuddin, Iqbal Nāmah of Mu’tamad Khan, the work of ‘Ārif, Muhammad Qandhari and a large number of Shah Jahān Nāmahs, besides Muntkhabul Lubab, are only a few of a large number of works written in the 16th and 17th centuries. Of Memoirs written by Emperors, I need only mention two. Everyone has read the memoirs of Babar and every student of Moghul history is acquainted with the Tuzaki Jahāngīri.

Ibn Battuta, as imagined by 19th century artist Paul Dumouza

There is another class of material in vernacular which should be taken into account in a discussion of the primary sources of Indian history. We have a large collection of Farmans lying scattered throughout the length and breadth of India, which are of the greatest value to the historian. The number of Farmans is exceedingly large but no systematic attempt has so far been made to collect them in a central place. Their value varies, but they are of special importance for the study of Moghul institutions and procedure. The material in the vernaculars is growing rapidly and the information contained therein is supplemented by the wealth and variety of documents which the patient research of some devoted savants has brought to light. Pandit Gauri Shankar Ojha has written valuable works on some Rajput States on the basis of materials collected by him; the Bharat Itihas Samshodhak Mandal of Poona has earned the gratitude of Indian scholars by the devotion and zeal it has displayed in preserving and utilising the material in Marâtbi, while the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal has published a number of very competent and sound monographs on some of the most obscure periods of mediaeval Indian history. The number of Hindi, Marāthi and Bengali documents that are of importance to the students must be considerable and an organized effort ought to be made to collect them. The manuscript material on the history of Muslim kings of Delhi is fairly large. Leaving aside the provincial kingdoms, it appears, from a work published by Khan Bahadur Zafar Hasan, that, out of 307 works in Persian, only 53 have been printed so far. Of this number, only a small proportion has been translated into English. Besides works in Persian, Arabic and Indian vernaculars, we have accounts published by foreign travellers. Their number is considerable though their value varies. Some are of great importance, while others contain garbled accounts of customs and manners of the people and are prejudiced, partial and misleading.

Gulbadan Begam

Ladies and Gentlemen, I am afraid I have wearied you with the dreary recital of works which are known to every student of our historical literature. It is not my object to supply you with a catalogue of books and manuscripts but to point out a few suggestions for research work in India. We have been accustomed to go through familiar works so often that no systematic efforts have been made for increasing the range or depth of our knowledge. The same monotonous and almost mechanical repetition of hackneyed manuscripts, the same trite and commonplace remarks, and precisely the same method and manner! We are so conservative and hide-bound by custom and tradition that it seems difficult to strike a new line, or initiate a new departure. Very few manuscripts have been printed in recent years, while the generation of European scholars represented by Smith, Lane-Poole, Raverty, Grant Duff, Malcolm and Kaye has passed away, leaving few worthy successors to take their place. True, we have a few living in our own times, who are trying to keep up the old tradition. But their number could be counted on the fingers of one’s hand and I feel that India will have to rely entirely upon her own efforts in elucidating the problems of her national growth, and tracing the chequered period of contemporary history. Administration in India has become so complex and complicated that it leaves a person in government service little or no time for the pursuit of literature or of history; and the difficulty has been greatly increased by the increasing tendency towards specialisation. In the History Department of the Allahabad University researches are being carried on in the Tughluq and Moghul periods, while Prof. Habib has worthily maintained the traditions of Aligarh by sustained research in pre-Moghul history. I am not aware of any other University where investigation into this subject is keenly pursued. The Universities of Southern India are wisely confining their activities to periods in which they are specially interested. This, together with the work in the Moslem period published by some learned societies such as the Asiatic Society, is the sum total of our efforts. This is a record of which Indian scholars cannot be very proud. It shows, not actual progress, but definite retrogression, and if this state of affairs continues we shall be in danger of losing what we have acquired after patient effort and ceaseless toil. The Arab conquest of Sind ought to have attracted the attention of a large number of inquirers, as it represents a striking and novel problem to students of the Caliphate, as well as to the scholars of Indian history. Yet the modern works were all published in the nineteenth century and we have the usual authorities starting from Ibn Khurdadb whose Kitābul Masālik wal Mamālik was translated in the Journal Asiatique in 1865, and ending with Major Raverty’s article on The Mihran of Sind and Its Tributaries, published in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, in 1892. No period affords greater opportunity for the study alike of the Imperial policy of the great Caliphs and of the organization and administration of India in the 8th and 9th centuries of the Christian era. Mahmūd Ghazni has been more fortunate, for a few monographs have lately appeared, which throw considerable light on a period which had been strangely enough completely ignored by historians. Muhammad Ghori and his brilliant general, however, still await a competent historian and we have not yet pursued systematic researches into the history of earlier Slave Kings of Delhi. Balban attracts greater notice, but even his administration must be pieced together from Barni, Khusrau, Mir Khwand, Firishta and Nizāmuddin Ahmad. Why? Not because there is a lack of sufficient material, but because it has not been carefully organized and the work is haphazard and jejune. The Khilji dynasty has, of late, received some attention and Indian scholars have published valuable monographs on the invasion of the Deccan, and on the administration of Alāuddin Khilji. It is, however, true to say that the full story of Qutbuddin Aibek and his successors, of Jalāluddin Firuz Khilji and even of Alāuddin has yet to be written. What shall we say of the Sayyid and Lodi dynasties? It is practically a blank. It is true that the material for this period is scanty, but the Sayyids, who organised some remarkable and distinctive institutions, have not yet found capable historians. The Lodi dynasty also goes unrecorded, and there is no clear and complete account of this dynasty. Sher Shah struck the imagination of his contemporaries, and we have a few competent articles and monographs on this remarkable man. It may be said of the period as a whole, that scholars have devoted comparatively little attention to the Slave and Lodi dynasties, partly because the material is scanty, and partly owing to the conventional mediocrities who ascended and descended from their thrones, without exciting the interests or evoking admiration of their contemporaries. Yet, there is reason to believe that it was a formative period of Indian history and witnessed the birth of literary and religious movements which had a profound effect on the country. We are on firmer ground when dealing with the Moghul Empire. Babar is a household word in Asia, and his memoirs are on the lips of every student of Moghul history. His fascinating personality has charmed generations of readers, and we have some brilliant monographs on this versatile man. Humayun does not fill the same space, but a full-length biography of Humayun is an urgent necessity. Jauhar supplies us with a wealth of information but we need a detailed and carefully documented account of this ineffective but beloved ruler. Of Akbar I need say little. He has claimed probably the largest number of competent and brilliant scholars, and the India of Akbar is as familiar to us as the India of John Company. The sayings of Akbar, the deeds of his famous marshals and the splendour of his court, are the subject of numerous works in English and the vernaculars. There is little likelihood of any fresh material being gleaned that will materially change our ideas of his character and achievements. The researches of Vincent Smith, Count Noer, Moreland and a host of Indian historians have succeeded in unravelling a tangled and complicated period in which we can legibly trace signs of new ideas and movements, the emergence of a feeling of national unity and a conception of a national Government. In Akbar’s reign religion and administration are not conceived as integral and indissoluble, and a serious attempt is made to effect a partial separation. The movement needs careful study and, though a number of articles and monographs have been published, there is no satisfactory or authoritative account, in English, of the religious, artistic and literary activity of the period.

WH Moreland and Akbar

There are, however, certain gaps in our knowledge of the Moghul period which could be filled satisfactorily, if a competent band of historians is organized and systematic research undertaken. The history of Moghul institutions is yet to be written. It is no disparagement of the works of scholars who have published some very useful monographs on this subject to state that Moghul history offers rare opportunities for the students of institutions. We have not yet been able to produce a single good book in English on procedure at the Moghul courts, while the functions of the Kotwãl, the Diwan, the Bakhshi and the Subedār have not yet been thoroughly investigated. Many of these officials were the pivots round whom the administrative machinery revolved, and a carefully documented history of some of the important Moghul offices will be of great value to students of institutions. The history of the judiciary under the Moghuls awaits a skilful researcher. Again, it is commonplace to assert that the most characteristic and brilliant contribution of the Moghul Empire to modern India consisted in the administration of revenue. I am not here to defend or criticise the system of revenue administration inaugurated by Sher Shah and Akbar; nor is it my function as a historian to discuss the relative merits of the Zamindāri and Raiyatwãri systems. I am concerned chiefly with the fact of its introduction and the consequences that flowed irresistibly from it. It was an undertaking of great magnitude and significance, and was introduced in India after careful and elaborate preparation. The material for its study is abundant, and it has been very effectively used by many scholars. The system was greatly modified in the eighteenth century, and completely transformed by the British in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. The works of Sarkar, Moreland, Ramsbotham, Smith, Firminger and others, have thrown considerable light on the subject, but it will be hazardous to state that no fresh inquiry is needed. We need a good work on the revenue and judicial administration under the Later Moghuls, when the impact of foreign invasions, the impoverishment of the people, and the general insecurity of life produced profound changes in the system. The Moghul secretariat continued to function regularly, and the canons formulated by the wise prudence and keen foresight of the early Moghuls seem to have been rigidly followed in the eighteenth century. The letters of Surman, who went to the court of Farukhsiyar to secure a Farmān for the Company, show that the Moghul secretariat was as vigilant and alert as ever. But the administration had become a huge soulless machine, lacking both initiative and momentum. A good work on Moghul bureaucracy is a great desideratum, and a comparative study of Moghul bureaucracy in the eighteenth century, Byzantine bureaucracy in the eighth and ninth centuries and the French bureaucracy as elaborated and perfected under Louis XIV will repay perusal. A few works have lately been published on Indian Art, Religion and Social movements in India during the Moghul period. I am, however, bound to say that the abundant and extensive material on this subject has not yet been effectively tapped. Moghul and Rajput paintings have received considerable attention of late, and the works of Brown, Dr. Coomarswami and others cannot be commended too highly. However, a visit to any famous library, such as the Rampur Library, will show the rich field that awaits the workers. I may here refer also to the military organization of the Moghuls. On the Mansabdāri system, as well as on the Moghul army, some brilliant articles have been written. But there is no connected history of the Moghul army, while the accounts of battles and campaigns are reproduced from the exaggerated and highly coloured language of the old chroniclers. The problem of the Mansabdāri has not yet been solved, and schools of thought still exist which are not yet agreed on the essential features of this system. There is no work on the administration of Afghanistan by the Moghuls. Kabul was then, as it is now, the stormy petrel of Asia. Yet, the Moghuls maintained their grip on the turbulent inhabitants of the city for more than a century. Was it an ordinary achievement to rule Kabul, manage the trans-border tribes, which then as now despised law and order, and acknowledged no overlordship? I do not know if the Afghan archives have preserved records dealing with the Moghul period, nor am I sure if the Persian Government can point to any important documents throwing light on its relations with the Moghul Empire. Attempts should be made to get transcripts of such records, if they exist, and some of our scholars should bring out an impartial history of the Moghul Empire in Kabul, Kandahar, and its relations with foreign powers. We have many references to foreign powers, in Moghul histories, and ambassadors from some States of central Asia and Persia. But the material has not been woven together into a coherent whole, while the subject itself has not been thoroughly investigated by historians. I would appeal to young Indian scholars to study this period as it will give an insight into the principles of Moghul imperialism.