Munshi Premchand is perhaps the first person that comes to mind when one thinks of Indian literature. But, from a historical perspective, it must be noted that his work was in fact a radical departure from the kind of stories that made up the bulk of Indian literature before him.

Born to a post-office clerk on 31st July, 1880, he wrote about the lives of common people, about “real human beings of bones and flesh.” Shining a light on the murkier aspects of human life – corruption, exploitation and poverty – he introduced ‘realism’ into Hindustani literature, which was before him, for a great part, telling stories “only for entertainment, or to satisfy our sense of wonder.”

He began writing in the early 1900s, under the pen-name ‘Nawab Rai’ (a derivative of his real name, Dhanpat Rai which would literally mean ‘wielder of wealth’). He adopted ‘Premchand’ as a name in 1909, after his first collection of short stories, Soz-e-Watan had drawn the ire of the British government, who declared the work to be seditious and had all copies of it burnt.

Till his demise in 1936, Premchand wrote several novels and short stories that would become iconic texts of Hindi and Urdu literature, all the while himself keeping his ear to the ground and becoming the voice of the marginalised and the exploited. However, his stories were not merely tales of passive victims; he centred them around moments of hope, compassion and resistance: a lodestone of sorts for the subaltern.

In doing so, he also became the guiding light for a new generation of writers in Hindustani: a few decades after Premchand, a wave of ‘progressive’ writers would emerge in India, whose stories, novels or poems spoke of the oppressed and imagined a radical new society free from exploitation and injustice.

These writers came together to form the Progressive Writers’ Association in 1935. The first initiative was taken by a group of young writers in London (including the likes of Mulk Raj Anand and Sajjad Zaheer), who published an eponymous Manifesto outlining their revolutionary philosophy of literature. It was Premchand who provided them with their first platform, by publishing the document in his influential Hindi journal, Hans.

The first meeting of the fledgling Progressive Writers’ Association was held in April, 1936 at Lucknow and was attended by the likes of Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Habib Jalib, Ismat Chughtai and Saadat Hasan Manto. These writers would eventually become the voice of a newly liberated subcontinent whose struggles against imperialism was followed by the shock of partition.

Premchand inaugurated this ambitious meeting as President, with the address we have reproduced for you below. A translation of this speech, originally in Hindi, was published in the Social Scientist in the November – December, 2011 issue (Vol. 39, No. 11/12).

Defining literature as a “criticism of life,” Premchand argues that literature in the present age has taken up the task of providing “spiritual and moral guidance.” Voicing what was then an unconventional outlook in Indian literature, he says that any work which does not have any “utility” must be rejected.

However, his definition of utility was not one tied to economic productivity or cold calculations. Rather, he spoke of a social utility: he wanted literature to rouse people, to instil in them the desire to challenge society and its oppressive system, and most of all, he wanted it to be free of “the apron strings of a particular class.”

Yet, he did not mean that literature must be judged only according to its social message. An artists’ tool would still be the “inherent sense of beauty” in all human beings, but our measure of beauty itself needed to be redefined. According to Premchand, beauty lay not in hiding the ugly aspects of human life. Truly beautiful literature made us “face the grim realities of life in a spirit of determination.”

Premchand’s address thus exemplified all that the PWA was to become: a radical redefinition of the nature and purpose of literature and its aesthetics.

(Quotes, where unattributed, are from Munshi Premchand’s speech ‘The Nature and Purpose of Literature.’)

The Nature and Purpose of Literature

Presidential Address of Munshi Premchand, delivered at the First All India Progressive Writers’ Conference, held at Lucknow on 10 April 1936. (Translated from Hindustani.)

This conference is a memorable occasion in the history of our literature. Hitherto we had been content to discuss language and its problems; the existing critical literature of Urdu and Hindi has dealt with the construction and the structure of the language alone. This was doubtless an important and necessary work. And the pioneers of our literature have supplied this preliminary need and performed their task admirably. But language is a means, not an end; a stage, not the journey’s end. Its purpose is to mould our thoughts and emotions, and to give them the right direction. We have now to concern ourselves with the meaning of things, and to find the means of fulfilling the purpose for which language has been constructed. This is the main purpose of this conference.

Literature properly so-called is not only realistic, true to life, but is also an expression of our experiences and of the life that surrounds us. It employs easy and refined language which alike affects our intellect and our sentiments. Literature assumes these qualities only when it deals with the realities and experiences of life. Fairy tales and romantic stories of princely lovers may have impressed us in olden days, but they mean very little to us today. Unless literature deals with reality it has no appeal for us. Literature can best be defined as a criticism of life. The literature of our immediate past had nothing to do with actuality; our writers were living in a world of dreams and were writing things like Fasanai Ajaib or Chandra Kanta; tales told only for entertainment, or to satisfy our sense of wonder. Life and literature were considered to be two different things which bore no relation to each other. Literature reflects the age. In the past days of decadence the main function of literature was to entertain the parasitic class. In this literature the dominant notes were either sex or mysticism, pessimism or fatalism. It was devoid of vigour, originality, and even the power of observation.

But our literary taste is undergoing a rapid transformation. It is coming more and more to grips with the realities of life; it interests itself with society or man as a social unit. It is not satisfied now with the singing of frustrated love; or with writing to satisfy only our sense of wonder; it concerns itself with the problems of our life; and such themes as have a social value. The literature which does not arouse in us a critical spirit, or satisfy our spiritual and intellectual needs, which is not ‘force-giving’ and dynamic, which does not awaken our sense of beauty, which does not make us face the grim realities of life in a spirit of determination, has no use for us today. It cannot even be termed as literature.

The literature which does not arouse in us a critical spirit, or satisfy our spiritual and intellectual needs, which is not ‘force-giving’ and dynamic, which does not awaken our sense of beauty, which does not make us face the grim realities of life in a spirit of determination, has no use for us today. It cannot even be termed as literature.

In the past, religion had taken upon itself the task of striving after man’s spiritual and moral guidance; it used fear and cajolery, reward and retribution as its chief instruments in this work. Today, however, literature has undertaken a new task, and its instrument is our inherent sense of beauty; it tries to achieve its aim by arousing this sense of beauty in us. The more a writer develops this sense through his observation of nature, the more effective will his writing become. All that is ugly or detestable, all that is inhuman, becomes intolerable to such a writer. He becomes the standard bearer of humanity, of moral uprightness, of nobility. It becomes his duty to help all those who are downtrodden, oppressed and exploited — individuals or groups — and to advocate their cause. And his judge is society itself: it is before society that he brings his plaint. He knows that the more realistic his story is, the more full of expression and movement his picture, the more intimate his observation of human nature, human psychology, the greater the effect he will produce. It is not even enough that from a psychological point of view, his characters resemble human beings; we must further be satisfied that they are real human beings of bones and flesh. We do not believe in an imaginary man; his acts and his thoughts do not impress us.

A postage stamp released by the Government of India to commemorate Premchand

The question may be asked, but what is beauty? Why does a waterfall, the sunset, and other such natural scenes and phenomena affect us? Because, there is a certain harmony of colour or sound in them. We ourselves are created by a harmony of elements, and our spirit always seeks the same balance and harmony in everything else. It is the harmony which creates beauty. Nature demands that this harmony should exist everywhere, and, the more art keeps in touch with nature and with reality, the better it will be.

In this sense, the name ‘progressive writer’ is defective: an artist or a writer is by his very nature progressive. But perhaps it is necessary to use this qualifying word because progress has a different meaning for different people. For us ‘progressive’ is that which creates in us the power to act; which makes us examine those subjective and objective causes that have brought us to such a pass of sterility and degeneration; and finally which helps us to overcome and remove those causes, and become men once again. We have no use today for those poetical fancies which overwhelm us with their insistence on the ephemeral nature of this world and whose only effect is to fill our hearts with despondency and indifference. We must, resolutely, give up writing those love romances with which our periodicals are flooded. We have no time to waste over sentimental art. The only art which has value for us today is that which is dynamic and leads to action.

For us ‘progressive’ is that which creates in us the power to act; which makes us examine those subjective and objective causes that have brought us to such a pass of sterility and degeneration; and finally which helps us to overcome and remove those causes, and become men once again. We have no use today for those poetical fancies which overwhelm us with their insistence on the ephemeral nature of this world and whose only effect is to fill our hearts with despondency and indifference. We must, resolutely, give up writing those love romances with which our periodicals are flooded.

According to us, subjective art is that which drags us down to inaction and passivity; and such an art is good neither for the individual nor for the society. I have no hesitation in saying that I judge art from the point of view of its utility. Undoubtedly, the aim of art is to satisfy our sense of beauty; and it is the key to our spiritual happiness. But happiness itself is a thing of ‘utility’. The same object from this point of view, may stir in us feelings of joy or sorrow.

But beauty like everything else is not absolute; it too has relative value. The same thing which gives happiness to one, causes pain to another. A rich man sitting in his beautiful garden and listening to the song of the birds thinks of paradise; to a poor but intelligent human being who regards this pomp of wealth as being tainted with the blood of workers, it is the most hateful thing.

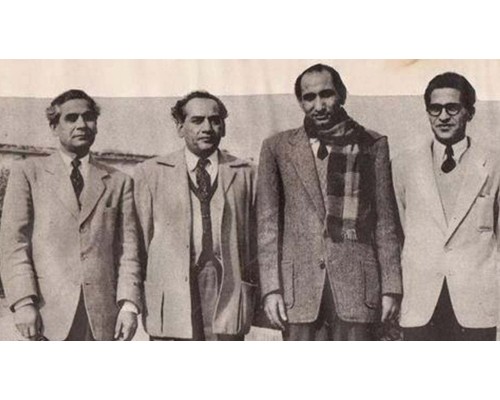

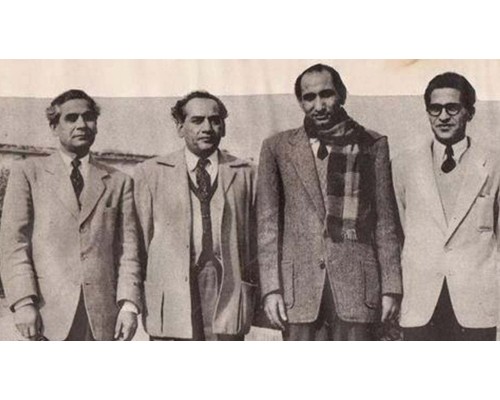

Progressive writers (left to right) Sibte Hasan, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Hameed Akhtar and Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi.

Brotherhood and equality, from the dawn of human culture and civilisation have been the golden dream of idealists. Religious leaders have made repeated attempts to realise their dream by creating religious, moral and spiritual sanctions. But they have not succeeded. Buddha, Christ, Mohammed, all the prophets, tried without success to lay the foundation of their equality on moral precepts without any success. Today the distinction between high and low, rich and poor, is manifesting itself with a brutality which has never been surpassed before. There is a saying amongst us that to try that which has already been tried is a sign of stupidity— we shall fail again if we attempt to attain our goal with the help of religion or ethics.

Are we then to give up our ideals? If that were so, the human race might as well perish. The ideal which we have cherished since the dawn of civilisation; for which man has made God knows how many sacrifices; which gave birth to religion — the history of human society is a history of the struggle for the fulfilment of this ideal — we too have to place that ideal before ourselves; we have to accept it as an unalterable reality and then see the vulgar pride, ostentation and lack of sensibility in the one, the strength of modesty, faith and endeavour in the other. And our art will notice those things only when our artistic vision takes the entire universe within its purview; when the entire humanity will form its subject matter, then it will no longer be tied to the apron strings of a particular class. Then we shall no longer tolerate a social system under which a single individual can tyrannise over thousands of human beings; then our self-respecting humanity will raise the standard of revolt against capitalism, militarism and imperialism; and we shall not sit quiet and inane after doing a little bit of creative work on pieces of paper, but we shall actively participate in building that new order which is not opposed to beauty, good taste and self-respect. The role of literature is not simply to provide us with amusement, or recreation; it does not follow, but is, on the contrary, a torch-bearer to all the progressive movements in society.

Then we shall no longer tolerate a social system under which a single individual can tyrannise over thousands of human beings; then our self-respecting humanity will raise the standard of revolt against capitalism, militarism and imperialism; and we shall not sit quiet and inane after doing a little bit of creative work on pieces of paper, but we shall actively participate in building that new order which is not opposed to beauty, good taste and self-respect. The role of literature is not simply to provide us with amusement, or recreation; it does not follow, but is, on the contrary, a torch-bearer to all the progressive movements in society.

We sometimes complain that literary men are not given an honourable place in society. That is to say, in Indian society. In other civilised countries, literary men are placed very high on the ladder of social esteem. The highest placed people in the land consider it an honour to meet and to know these men. But, then, India is still in many ways living under medieval conditions. If our writers have played the sycophant to the rich to earn their livelihood by flattery, if they are unaware of the dynamic forces working in modern society, if they choose to shut themselves up in ivory towers, completely oblivious of their surroundings, it is not surprising that they find themselves as a class more and more discarded by society. It is true that writers are born and not made, but we should not forget that rigorous intellectual, moral, spiritual and emotional discipline which Aristotle has prescribed for them. With us a simple inclination to write is considered sufficient reason for a man to take to the profession of writing. He need not equip himself for it, he need have no knowledge of politics, economics or psychology; and still he will be a writer. This should not be so, for it is a sign of stagnation.

Progressive Writers Rashid Jahan (second from right) and Mahmood-uz-Zafar (extreme left), who contributed to the short story collection ‘Angarey,’ considered the genesis of the PWA

The ideal which we want to put before literature today is not that of subjectivism or individualism, for literature does not see the individual as something apart from society, but considers him as a social unit; because his existence is dependent on the society as a whole. Taken apart from society he is a mere cypher and non-entity. It follows, therefore, that those of us who have the good fortune to be educated and who have been endowed with a trained intellect, have certain obligations towards society. Just as we consider the capitalist to be an usurper and an oppressor, because he lives on the labour of others, in the same way we should strongly condemn the ‘intellectual capitalist’, who, after having received the best education uses it for his own private ends. It is the duty of our intellectuals to serve society in every possible way. They should acquire not only the art of writing well, but should also acquaint themselves with the general condition of society. If we read the reports of International Writers’ Conferences we find that there is hardly a subject concerning life, literature, economic problems, historical controversies, philosophy, which is not discussed there. When we compare ourselves with these people, we really feel ashamed of our ignorance. We must, therefore, raise the cultural level of our writers. I know it is difficult under the present economic system, but let us at least strive after this. Even if we do not reach the top of the mountain, we shall at least raise ourselves from the surface of the earth to a higher place. With love to guide our activities, and with the service of humanity as the outward manifestation of this love, there is no difficulty which we cannot overcome. For those who are after wealth and riches, there is no place in the temple of love. If we place our services at the disposal of the masses of this country, we shall have done our duty. The happiness which we get from serving humanity will be our reward. We stand or fall with society, and as true artists we should disdain self advancement and cheap exhibitionism.

Just as we consider the capitalist to be an usurper and an oppressor, because he lives on the labour of others, in the same way we should strongly condemn the ‘intellectual capitalist’, who, after having received the best education uses it for his own private ends. It is the duty of our intellectuals to serve society in every possible way. They should acquire not only the art of writing well, but should also acquaint themselves with the general condition of society.

Such are the objects which have led to the formation of the Indian Progressive Writers’ Association. It wants literature to bear the message of efforts and action. It is not concerned with the problems of language as such. With a correct ideology, language will become simpler and better. So long as the content of our writing is on the right lines, we need not worry about the form. The literature which is patronised by the privileged classes will adopt their forms of expression; the literature which is of the masses will speak their language. Our object is to create such an atmosphere in this country as would help the growth of progressive literature. We want to establish branches of our Association in all the literary centres of India; we want to organise the creative literary life in those centres, by reading papers, by discussions and through criticism. It is in this way that our literary renaissance will take place. We want a branch of the Association in every province and in every linguistic zone, so that we can carry our message to all parts of the country. For some time past, Indian writers have been feeling the necessity for such an organisation. At various places some steps have already been taken in this direction. Our object is to help all such progressive tendencies in our literary world. We writers suffer from one great defect, and that is the absence of action in our lives. It is a bitter reality; we cannot shut our eyes to it. Indeed, this absence of an active life was considered to be a virtue by our writers, for it was agreed, an active life leads to intolerance and narrow-mindedness. A puritan, enforcing his doctrine on others, is certainly a greater nuisance than a libertine; the latter may save himself, whereas there is no hope for an arrogant puritan. So long as the object of literature was mere entertainment, so long as it was a means of escape from life, when it demanded a mere shedding of tears over life and its sorrows, an active participation in the social struggles was not required from a literary man. We, however, have a different conception of literature and the duties of a writer. We shall consider only that literature as progressive which is thoughtful, which awakens in us the spirit of freedom and of beauty; which is creative; which is luminous with the realities of life; which moves us; which leads us to action and which does not set on us as a narcotic; which does not produce in us a state of intellectual somnolence— for, if we continue to remain in that state it can only mean that we are no longer alive.

Leave a Reply