Vyangya Chitravali, 1930

In 2015, the Pinjra Tod movement asked a critical question, why do women have to face hostel curfews when men don’t? The traditional answer to the question is ‘simple’: women are under threat of sexual violence and curfew timings are there to ‘protect’ and keep women ‘safe’.

Meanwhile, women who trespass on this ‘safety’ by venturing into public spaces during ‘odd’ hours and in ‘odd’ places or attire are held responsible for inviting violence and the lecherous male gaze. Why don’t we instead hold men responsible and impose curfew restrictions on them for threatening women’s safety? In the book ‘Why Loiter?: Women & Risk on Mumbai Streets’ scholars Phadke, Khan and Ranade argue that “safety for women is framed through the creation of a fallacious opposition between the middle-class respectable woman and the vagrant male (read: lower class, often unemployed, often lower caste or Muslim). By creating the image of certain men as the perpetrators of violence against women, women’s access to public space is further controlled and circumscribed and acquires an unquestionable rationality.”

Saurav Kumar Rai’s essay ‘Gazing at the Woman’s Body’ historicises this unfortunately familiar discourse by tracing it to the late 19th-century United Provinces (corresponding to today’s Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh). His central argument in the essay shows how the threat of the male gaze was used by the newly emerging and ‘reforming’ middle class during the colonial period to restrict access to employment and public space strategically, to maintain a patriarchal division of labour. Despite and because of reforms aimed at bettering the lives of women during the colonial encounter, the Indian patriarchal social structure found itself under increased threat during the 19th and 20th centuries. In this period, women got unprecedented access to education, travel, public space and employment. Rai argues that to manage the threat of women entering supposedly male-only spaces and occupations, didactic literature aimed at women readers but written by men, sprung up. The cartoons and write-ups in this genre of literature aimed to make women aware of the threat of the lecherous male gaze in various spaces. Ultimately, The goal was for women to self-discipline or regulate their movement in spaces to avoid this gaze and maintain their respectability.

This essay was published first in the journal – Social Scientist – Vol. 47, No. 1-2, 2019 and is re-published here with the author’s generous permission. Dr Rai’s new book ‘Ayurveda, Nation and Society: United Provinces, c. 1890–1950’ is out now. Please click on the book jacket cover below the essay to purchase a copy and support critical scholarship.

The interviews of the defence lawyers M.L. Sharma and A.P. Singh in the ‘Nirbhaya’ case in 2015, in the BBC documentary India’s Daughter, exposed a disturbing aspect of the patriarchal social structure which blames women for arousing the ‘lustful’ and ‘lecherous’ male gaze and subsequent repercussions. Making highly offensive and misogynistic remarks, lawyer M.L. Sharma claimed: ‘If you will keep sweets on the street then dogs will come and eat them.’ Commenting on women’s attire, he further added, ‘If you are fully covered, nobody will disrespect you or hurt you.’ Moreover, drawing on a misogynistic anecdote of women as flowers and men as thorns, he shamelessly argued, ‘Where is the question of rape? Had she stayed home, this would never have happened and therefore she is responsible for what happened. Why should you put yourself in a situation where you cannot protect yourself? She gave the men an opportunity to misbehave with her.’

The aforementioned instance of holding girls/women responsible for unnecessarily arousing the lustful and lecherous male gaze through their ‘careless’ attire and movement outside the household sphere during ‘odd’ times is not new. We have numerous instances of instructions and guidelines being issued by politicians, community leaders, religious heads, institutions, etc., advising women to keep themselves away from the lustful and lecherous male gaze by adopting ‘proper’ attire and restricting their movements in public as much as possible. For example, Banwari Lal Singhal, an MLA from Rajasthan, in 2012, asked the Chief Secretary of the state to impose a ban on skirts as school uniform and to replace skirts with trousers or salwar-kameez. Singhal explained that his intention was to keep schoolgirls away from men’s lustful eyes. In his words, ‘It is not a Talibani type of thinking or restriction on girls’ freedom or rights but a concern for their safety.’

Incidentally, when one looks at this entire phenomenon of restricting and streamlining women’s mobility, visibility, and clothing historically, one finds an interesting corollary to it in colonial India, particularly with the emergence of the middle class in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. It was the emergence of the middle class in India that precipitated new kinds of debates on women’s clothing and accessibility in public places. In this context, the present paper attempts to historicise the patriarchal didactics over women’s clothing, mobility, access to public sphere, etc., with special reference to early twentieth-century United Provinces (present-day Uttar Pradesh). Simultaneously, it also brings out the dilemma of the middle class over social reforms associated with women, which in many ways, as the paper argues, was/is the product of a patriarchal social structure. In other words, it traces the historical roots of the middle-class desperation to control women’s sexuality and mobility by using the threat of the lustful and lecherous male gaze.

Gaze as a Controlling Tool

Gazing as a concept was popularised by the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. According to Lacan, gazing makes an individual conscious of his/her appearance, often to the extent of anxiety and shame. The gaze, as argued by Lacan, is presented to us in the form of a strange contingency which in turn generates unrealistic anxiety. It surprises and disturbs the individual subjected to the gaze and often reduces him/her to a feeling of shame. In other words, an individual subjected to someone’s gaze (whether real or imaginary) turns him/her into a self-conscious being, thereby losing a degree of autonomy upon realising that he or she is being viewed.

This Lacanian concept of the gaze can be used to analyse the phenomena of ‘lust’ and ‘lechery’ in a patriarchal society. Both the terms broadly indicate unrestrained inordinate sexual desire basically associated with the male gaze in a patriarchal set-up. Interestingly, patriarchy in many ways firstly makes women conscious of the lustful and lecherous male gaze, and then, instead of blaming the male sex for having such disturbing gaze, advises women not to come within the sphere of such gaze. In other words, the patriarchal logic attempts to invisibilise women from prospective sites of the lustful lecherous male gaze instead of curbing that gaze. This leads to numerous didactic texts and directives forced upon women regarding what to wear, where to go, what jobs to take up, so on and so forth.

In other words, the lecherous gaze becomes one of the tools in the hands of a patriarchal social structure to control women. In fact, as will be shown later, the lustful male gaze in many ways becomes an excuse to reinforce purdah (veil) and to restrict women’s mobility in the public sphere. The newly emerged Indian middle class in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century particularly used this controlling tool to reinvent Patriarchy.

The Dilemma of the Indian Middle Class

The women’s question dominated nineteenth and twentieth-century middle class-led social reforms in India. In fact, questions concerning women became so central to the social reform agenda of this period that whether it was the so-called ‘revivalists’ or ‘reformists’, both engaged with this issue in one way or another. This was largely because the degraded conditions of Indian women had become one of the chief indicators of India’s inferior status in the hierarchy of civilisations. Incidentally, based on the degraded conditions of women, western observers, like James Mill, even developed a ‘civilisational critique of India’.

The Indian middle class and the nationalist elite were quick to respond to this ‘civilisational critique’ levied against India, and came up with a series of reform movements pertaining to women. However, as some of the recent historiographical writings on women’s social reform in the colonial period have shown, whether it was the colonial state, Christian missionaries or Indian reformers, all of them were driven by their own respective self-interest while addressing the issue of women’s reform. In other words, ‘women’s reform’ was just a symbolic gesture and was never a substantial concern as eventually all of them reinvented patriarchy in some way or other. To restrict our discussion to the Indian middle class, for them, reform of women’s condition was essential in order to counter the ‘gendered critique of Indian civilisation’ that was so prominent in the colonial discourse. According to Mrinalini Sinha, the colonial discourses on India from very early on were ‘gendered’, as the colonised society was feminised and its ‘effeminate’ character, as opposed to ‘colonial masculinity’, was held as a justification for its loss of independence. It was in this context of a gendered colonial discourse that the Indian reformers had to take up the issue of women’s reform.

Similarly, according to Partha Chatterjee, with the emergence of incipient nationalism in the nineteenth century, women became a part of the ‘uncolonised inner sphere’, and this sphere attracted most of the nationalist and middle-class intellectuals and social reformers to assert their autonomy vis-à-vis the colonial state, which is why issues related to women became particularly important for them. In fact, commenting on the class bias of these reforms, scholars like Sumit Sarkar, Charles Heimsath and others have characterised the social reforms of the period as being particularly an elite, urban phenomenon that was primarily concerned with upper- and middle-class women and rarely looked at lower-class women. In a similar vein, subaltern and early feminist writings of Lata Mani, Mrinalini Sinha, Uma Chakravarti, etc., have shown how an inherently male-dominated discourse on the women’s question led to a ‘recasting of patriarchy’ and women were reduced to being just ‘sites of contesting traditions’ in most of the middle class-led debates on social reforms, such as in the case of sati, widow remarriage, prohibition of female infanticide, age of consent debate, child marriage, so on and so forth.

However, as recent feminist writings by Andrea Major, Tanika Sarkar, Anindita Ghosh, Janaki Nair, Charu Gupta, etc., have shown, it is very hard to draw a neat and clean picture or concrete conclusion on any issue related to gender and middle class-led social reform movements. While ‘recasting of patriarchy’ did take place, at the same time it also provided women tools and means to break away from the existing boundaries, which is very much evident in the case of women’s education. For example, as argued by Charu Gupta, once women were given education, howsoever traditional it might be, it was very hard to control what kind of books they read and the uses to which they put their knowledge. Similarly, as pointed out by Anindita Ghosh, women were not passive receptors of these male-dominated, hegemonic discourses on women’s reforms; rather, they recorded their resentment through the ‘power of print’ and sometimes through the ‘everydayness’ of their resistance, which has been captured brilliantly by Haynes and Prakash in their edited volume.

At the same time, modern means of communication and the emergence of a new kind of public sphere also facilitated greater mobility of women during the period under discussion. For instance, there was a spurt in women going to bathing ghats during religious festivals/occasions. Railways and other modern means of transportation particularly made going on pilgrimages much easier by increasing mobility. Similarly, new kinds of public spheres were coming up where women could go, especially in cities, such as educational institutions, cinemas, theatres, parks, clubs, social service organisations, etc.

The duality of social reforms and opening up of new avenues for women’s mobility with the advent of colonial modernity threatened and placed the Indian middle class in a dilemma. The root cause of this dilemma was the patriarchal structure which the Indian middle class had been clinging on to. The middle class wanted women’s reforms not to overthrow the patriarchal social structure, but to counter the critique levied against them and the Indian civilisation by the colonial state. However, the way things moved once the reforms started and colonial modernity came into play, it posed a real challenge to the patriarchal social structure. It was in this context that the Indian middle class realised the need of didactic literature for ‘reformed’ and ‘respectable’ women of their own class and caste. A close analysis of such literature emanating from the United Provinces in the early twentieth century clearly brings out this dilemma of the Indian middle class and the way they were trying to ‘reinvent patriarchy’ in their own way. Interestingly, in this entire process of ‘teaching’ women, the threat of the lecherous and lustful male gaze became one of the frequently occurring templates of such didactic literature.

Dictating through Didactics

The early twentieth century witnessed a thriving print culture. The number of printing presses in the United Provinces rose from 177 in 1878–79 to 568 in 1901–02 and 743 in 1925–26. Also, by 1925–26, the United Provinces had surpassed Bengal in the production of vernacular books. The newly emerged middle class was particularly active in this thriving vernacular print culture of the United Provinces. In fact, print was a tool in the hands of the upper-caste/middle-class elite of the province to propagate and substantiate their own ideas in the society. In this regard, as argued by Pierre Bourdieu, although the literary field is a ‘relatively autonomous’ structured space and has its own ‘laws of operation’, it is always embedded within and subject to the indirect influences of a larger field of socio-political and economic power. Similarly, drawing upon the conceptual framework of Peter Hohendahl, Francesca Orsini has shown that the educated Indians often advanced their political and social agendas through ‘literary institutions’ (publishing houses) active in the Hindi public sphere over the period 1920–40. In such a situation, these socio-political interventionist forces also impacted the production of vernacular tracts in the United Provinces, and often exhibited middle-class concerns, enthusiasm and dilemmas.

In the aforesaid context, a very popular genre of literary production of early twentieth-century United Provinces was didactic literature. This didactic literature attempted to enshrine upper-caste/middle-class norms, values and concerns within the society. Of course, control of women’s sexuality and mobility was one of the foremost concerns of such literature. Numerous didactic tracts, journals and cartoons were produced during this period which exhibited the efforts of the middle class to command the sexuality and mobility of ‘their’ women or the so-called ‘respectable’ women by invoking the threat of the lustful and lecherous male gaze. Middle-class journals like Chand, Madhuri, Saraswati, etc., were particularly active in this regard.

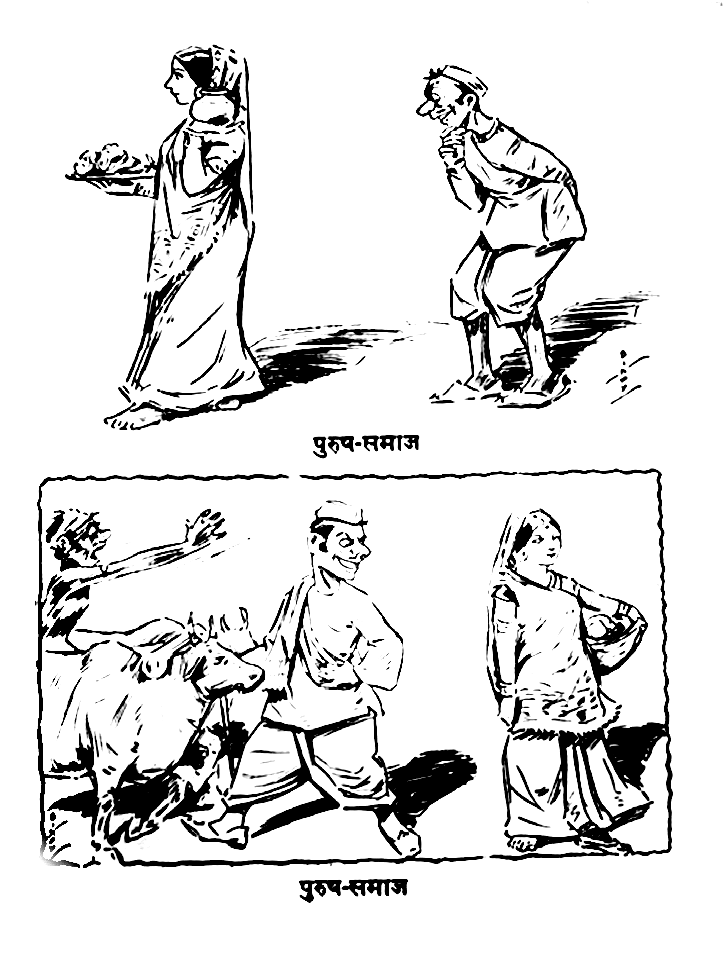

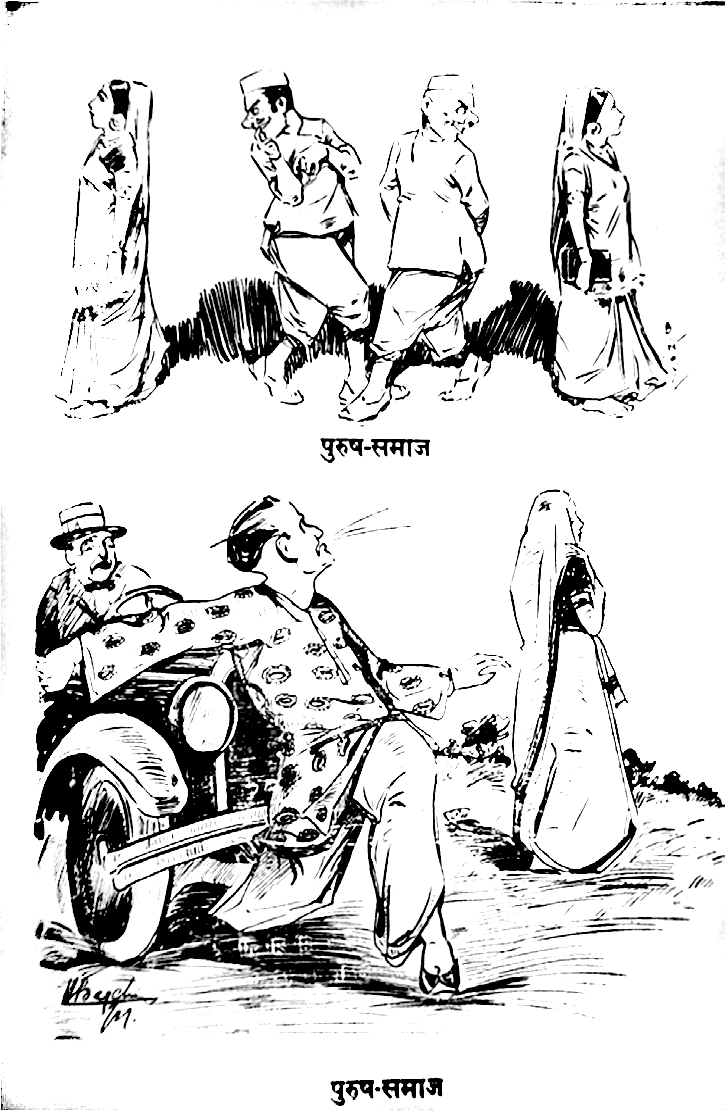

In fact, Chand came up with a special issue in 1930 which presented interesting caricatures of ‘purush samaj’ or patriarchal society with the lustful and lecherous male gaze (see figures 1–3). These caricatures can be viewed from two different angles. On the one hand, they can be seen as a (feminist) satire or critique of patriarchal society for its lustful gaze towards women; conversely, they can be viewed as a tool in the hands of patriarchal society to restrict the mobility of women outside the household by invoking the threat of the lecherous gaze prevailing in public spaces. Incidentally, when one juxtaposes these cartoons/caricatures with articles published in different issues of Chand and other such journals, it becomes clear that these were actually made to convey a message to the middle-class women to avoid public places like stations, ghats, markets, etc. In other words, these were actually controlling tools in the hands of the patriarchal middle class to restrict the mobility and guide the dress of ‘their’ women. It was an interesting example of how self-criticism of patriarchal society led to imposing restrictions on women. This reveals how, in a patriarchal structure, even self-criticism may be used for dramatic purposes. Instead of instructing men to avoid the lustful and lecherous gaze, it was used to uphold guidelines for women right from their dressing habits to movement outside the household. An interesting aspect related to this is the debate over the veil that took place amongst the middle class during this period, as exhibited through literature.

Figure 1: Purush Samaj (source: Vyangya Chitravali, 1930)

Figure 2: Purush Samaj (source: Vyangya Chitravali, 1930)

Figure 3: Purush Samaj (source: Vyangya Chitravali, 1930)

Re-Veiling Women

With the spurt of social reforms for women in nineteenth- and twentieth-century India, a lot of debate took place over the purdah (veil). As was the case with many other women-oriented reform movements in colonial India, the veil was an issue particularly significant for upper-caste Hindus and the middle class as it was they who celebrated purdah (veil) as a symbol of ‘honour’ and ‘prestige’. This was largely because purdah or veil was intrinsically linked with social status in Indian society. That is why often, many intermediary castes also adopted purdah in the course of their upward social mobility. However, for the British it was a symbol of the low and subservient condition of women in society, which, in turn, had a direct bearing on the ranking of India in the ‘hierarchy of civilisations’.

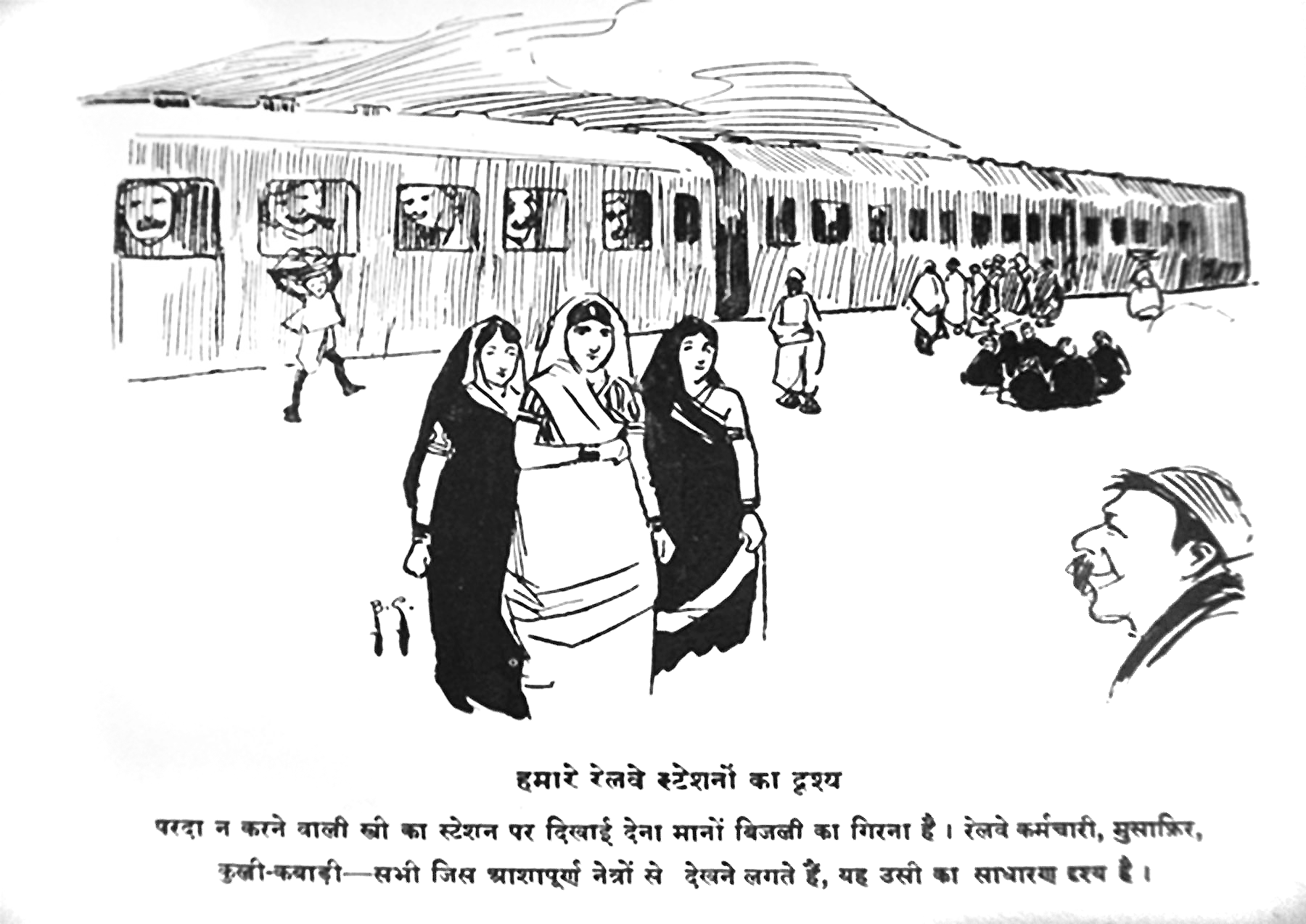

This put Hindu social reformers and the newly emerged middle class in a precarious position. While on the one hand they had to oppose purdah to show the British their liberal attitude towards women, on the other hand they tried to rationalise it occasionally by invoking the presence of a society full of lustful and lecherous male gaze. ‘Lajja’ or shame, as argued by Charu Gupta, was deemed as the biggest adornment of women and attempts were made to convince women to adopt purdah on their own. It was argued that a ‘respectable’ woman did adopt purdah in public. Thus, in the middle-class literary discourse, efforts were made to position purdah as a kind of ‘voluntary compulsion’ on the part of women to avoid the lecherous male gaze, especially at railway stations, bathing ghats, markets, etc. In fact, these were the places seen as having licentious males with lustful gazes (see figure 4). Often, such characterisation of licentious males having lecherous gaze acquired casteist and communal overtones as well. As for instance in figure 4, where the licentious male (a porter) at the railway station has been caricatured to resemble a stereotypical Muslim. However, such characterisation was not limited to any particular caste and community, and was extended to other railway staff and passengers as well who might be of any caste and community.

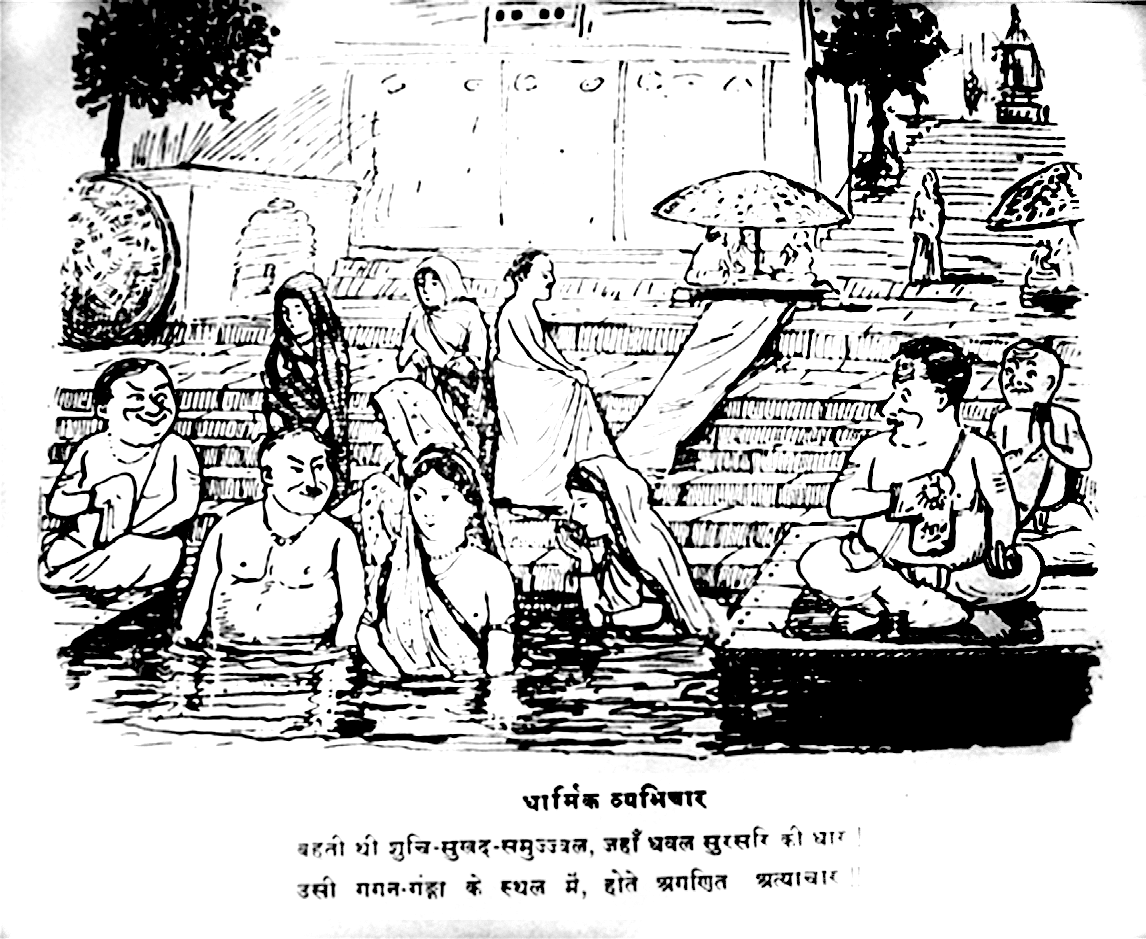

A corollary to this was the debate over women bathing at ghats on ceremonial occasions. In this case upper-caste Brahmin pandas (priests) were portrayed as having the lustful and lecherous male gaze (see figures (5 and 6). Women bathing semi-nude at public ghats became a symbol of ‘uncivilised’ ‘shameless’ activity in the middle class imagination. Brahmin pandas were severely criticised for their lecherous gaze at bathing ghats and women were warned against such licentious ‘holy’ men. While some of them argued for separate bathing ghats for women or ‘zenana ghats’ to protect ‘their’ women from such lustful eyes of pandas, others issued several guidelines to women while undertaking public bath on religious occasions. There were also voices which completely opposed such ‘sexualised’ public bathing.

Interestingly, as argued, often caste, class and community oriented biases and prejudices were also reflected in the middle class discourse over purdah or veil. A middle class women was seen as different from ‘shameless’ and ‘immoral’ women belonging to lower castes/class. In fact, a lower-caste/ class woman working openly in the fields and roaming unveiled in public spaces was always viewed as ‘available’ to all to satisfy the lecherous and lustful male gaze. The popular bawdy local proverb from the eastern part of the province – Garib ki joru sab ki bhaujai (A poor man’s wife is a fair game) – exquisitely captures this upper-caste/class patriarchal mindset. Similarly, Hindu social reformers of the United Provinces stressed on the necessity of the veil by exaggerating the lust of Muslim men and nawabs historically. Ogling of Hindu women’s breasts at public ghats by low-caste Hindu and Muslim men (besides licentious Brahmin pandas) was a constantly invoked image in the middle-class literary discourse of the period under discussion.

Figure 4: Scene at our railway stations. The very sight of an unveiled woman at the railway station is like a flash of lightning and crash of thunder. Railway staff, passengers, porters – everyone starts looking at them with lustful eyes, as shown above. Source: Vyangya Chitravali, 1930.

Figure 5: A licentious Brahmin panda. These are not real ascetics who have left all worldly fancies. Their real interest still lies in the irresistible charm of beautiful women. Source: Vyangya Chitravali, 1930

Figure 6: Religious corruption at bathing ghats. The place where once flowed the pure, pleasant and dazzling stream of the Ganges, has now been turned into a site of religious corruption of several kinds. Source: Vyangya Chitravali, 1930.

Commenting on this moral dilemma of the newly emerged Indian middle class and its efforts to control women’s attire and visibility in the public sphere, Himani Bannerji, in the context of Bengal, argues that while advocating education for women and other reforms, the middle class nowhere wished destabilisation of traditional gender roles and real autonomy of women. That is why a reformed woman or bhadramahila was essentially a part of the ‘inner’ domain and she was not supposed to do ‘what men do’, viz. striding in the ‘outer’ domain. Efforts to re-dress or re-veil women in ‘civilised attire’ had less to do with restricting sexual exploitation or curbing the vulnerability of women, and was more connected with the middle-class project to confine women in their ‘traditional’ roles within the household, thereby re-establishing the patriarchal sexual division of labour. It should be noted that earlier also women had access to public spheres but this nowhere challenged the patriarchal structure; in the past, women’s accessibility to public places never undermined the established sexual division of labour. However, with social reforms such as in the sphere of women’s education, middle-class women acquired the potential to break the traditional sexual division of labour in their capacity as intellectual interlocutors of men, as students, and as professionals such as teachers, clerks or doctors. It was in this context of the ‘unnaturalness’ of the social presence of middle-class women and their potentiality to challenge the established sexual division of labour that patriarchal middle-class men felt the need to launch a moral regime for ‘their’ reformed women in which the veil acquired significance. Conceptualisation of a ‘licentious and lustful male society out there’ was an important tool to restrict reformed middle-class women from coming outside in the public sphere.

Further, as argued by Bannerji, since women’s body had acquired larger moral–social–functional implications in the colonial context, the middle-class men felt it as their ‘responsibility’ to streamline women’s sexuality. It was in this context that the attainment of chaste sexual morality, minimization of a woman’s physicality, her decency, etc., became the goal of middle-class sartorial projects. The middle class even injected their sartorial concerns related to women in the ongoing nationalist movement and thus, the matter of clothing, of even fashion design, became one of the several concerns of nationalism. In fact, as Fred Davis has argued, hemlines started dropping with the gradually increasing fervour of the nationalist movement. Similarly, Emma Tarlo has shown important linkages between clothing and the construction of identities, families, castes, class and regions in colonial India.

Interestingly, support for the veil was not always as open and vocal as in the aforesaid examples. Middle-class men often resorted to less expressive, shuttle infusion of the idea of the veil in women’s minds. As argued earlier, owing to the colonial discourse on the direct connections between women’s position and liberty in the society and the ranking of the civilisation, Indian middle-class men were in a precarious position vis-à-vis the veil. They wanted ‘their’ women to adopt it ‘voluntarily’. Hence, any voluntary adoption of veil by women was indirectly cheered, praised and even celebrated. One can cite here a speech of Rai Pooran Chand, who was an Ayurvedic practitioner, on the plague, delivered at the All India Vaidya Sammelan in Kanpur in 1912. In the speech, he described an incident when he had gone for the medical check-up of a female patient on the request of a reputed client. When he visited her for the first time, she was unconscious and unveiled. He checked her pulse and gave some medicine. When he visited her the second time, she had regained her consciousness. And when he was checking her pulse this time, she veiled herself in modesty. To quote Rai Pooran Chand: ‘Us din rogi ne apne se nadi dikhlaya. Mujhe dekh lajja prakash kar ghonghat de liya jabki barah ghante pehle ghar walon ke yatna karne par bhi tanik lajja na ki thi’ (That day the patient showed me her pulse on her own. She veiled herself in modesty, although twelve hours earlier [when she was unconscious], despite the attempts of the family members, she had shown no such signs of modesty). In this entire description, we find indirect reinforcement of the purdah by a medical practitioner. In his speech, he very cleverly showed the connection between purdah and its vital importance in so far as a conscious person was concerned. Thus, once the woman patient regained her consciousness, she found it obligatory to veil herself during the check-up.

Concluding Remarks

From the above discussion it is clear that controlling women’s sexuality and mobility by invoking the extant threat of the lustful and lecherous male gaze that women might encounter in the public sphere is not a new thing. In fact, the patriarchal social and family structure makes a girl/woman conscious of such lecherous male gaze as soon as she attains adolescence. Several familial and societal restrictions are put on her attire, mobility, access to public places, etc. Often such patriarchal restrictions acquire communal and political overtones. It is in this context that one can locate community and political leaders making public statements over the banning or donning of particular kinds of attire by women. Moreover, attempts are also made to restrict women’s mobility as much as possible. Certain jobs are deemed as ‘safe’ or ‘congenial’ for women. For instance, teaching jobs, especially at primary level, are supposed to be most suited to women. The basic attempt here is to maintain the traditional sexual division of labour as much as possible even when some autonomy is granted to women.

Following the above logic, unsafe public spaces or workplaces turn in favour of the patriarchal structure as it helps in maintaining traditional gender roles. Threats of a lecherous and lustful environment juxtaposed with culturalist arguments offer a perfect excuse for maintaining gender inequality. Thus, the middle-class discourse of women’s liberty often imparts ‘pseudo-autonomy’ and remains at the level of an idealised discourse as the broader social structures on the ground still remain gender-biased. This is largely because in terms of ideological orientation, despite all its progressive ideas, the middle class still carries the same patriarchal norms. Control over women’s sexuality and mobility is as important for this class as it is for its feudal predecessors, and the gaze becomes an important control mechanism in this pursuit.

To support Dr Rai’s scholarship, please click on the book jacket below to purchase a copy of his new work ‘Ayurveda, Nation and Society: United Provinces, c 1890-1950’ or recommend its purchase to your institutional library.

Saurav Kumar Rai currently works as a research officer at the Gandhi Smriti and Darshan Samiti, New Delhi. He previously served as a senior research assistant at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library. Rai regularly writes on themes such as Gandhian thought, Gender, and Social Histories of Health and Medicine. In 2024, he published his book ‘Ayurveda, Nation and Society: United Provinces, c. 1890–1950’ under Orient BlackSwan’s ‘New Perspectives in South Asian History’ series.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply