A day such as our 77th Independence Day begs the question: What was it like before we were free?

Before we were free, the towering figure of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi led movements like the Non-Cooperation and Quit India movements, setting the subcontinent’s imagination on fire.

Before we were free, organisations like the HSRA (Hindustan Socialist Republican Association), coming from a long lineage of revolutionary movements, made the British sit back and wonder about the wisdom of remaining strangers in a strange land whose people they oppressed.

Before we were free, a man named Subhas Chandra Bose travelled the earth to raise an army which, he hoped, would be successful in taking back his country from the other.

But in these meta narratives of the freedom struggle, we continue to focus on the top down, ignoring the obvious and the locally grown.

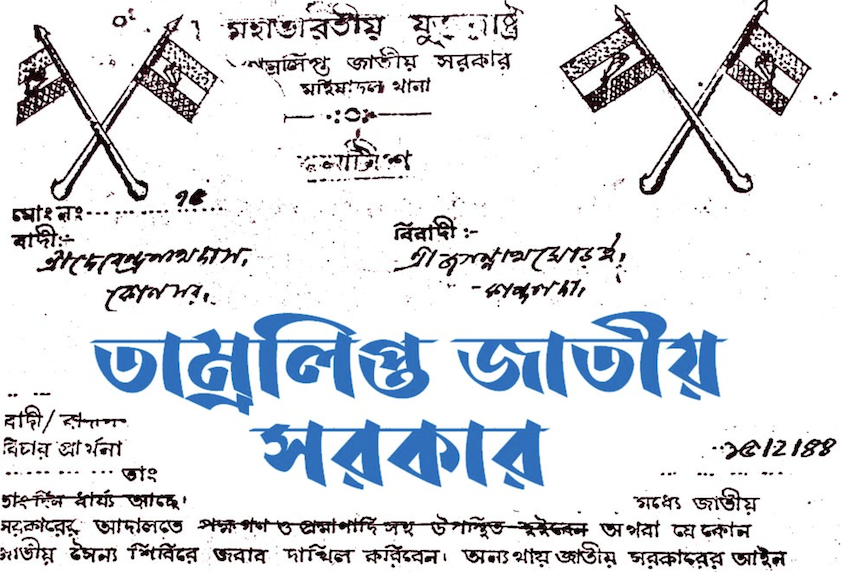

For, before we were free, on the 17th of September, 1942, a parallel government was announced by the Tamluk sub-divisional Congress Committee, at the Tamluk subdivision in Bengal. The government, named the ‘Mahabharatiya Juktarashtra – Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar’ would rule, independently, from the British, over Midnapore’s subdivisions of Tamluk and Contai. Its aim would be to free the region of British authority, offer worthy governance and justice to its people and, eventually, to transform India into a Mahabharatiya Juktarashtra, or a great Indian union of states.

Tamralipta is held by some scholars (though this is disputed by others) to be an ancient port city located where present day Tamluk is to be found, in West Bengal. ‘Jatiya’ indicates ‘community’. ‘Sarkar’ translates into ‘government’.

12 days later, on the 29th of September, processions heralding this cause occupied police stations and government offices in the region, redirecting them to serve the newly instituted Jatiya Sarkar.

The birth of this Sarkar coincided with the area being ravaged by famine in the aftermath of a cyclone and a tidal wave, and British Indian authorities doing nothing to provide relief, despite impassioned pleas to the Governor and Chief Minister of Bengal by political leaders like Syama Prasad Mookerjee (who resigned his post as minister). One proposed reason for such apathy from the authorities was the region’s engaged involvement in the Quit India Movement, for which it had recruited a Bidyut Bahini, comprising men, as well as a Bhagini Sena, comprising women. These became the ‘army’ of the new Sarkar. Pradyot Kumar Maity, whose book Quit India Movement in Bengal and the Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar we’ve referred to continuously below, writes, “No such woman army organisation was formed in any part of India in connection with this movement. (It may well be the case that the formation of Bhagini Sena had influenced the organisers of I.N.A to form the Jhansi Rani Brigade in August, 1943.)”

The Jatiya Sarkar is especially significant when seen in the context of debates of the time, in Britain and India, on ‘Indian Self Rule’. The Sarkar established not just an army but a system of courts as well as departments of Law and Order, Finance, Education, War, Justice, Home and Defence and Education, under different ministers. At the head of government was a Sarbadhinayak, or dictator— a position which was to be occupied on a rotational basis. Biplabi, (or ‘revolutionary’) previously published to communicate the philosophy of the Quit India Movement by the Tamluk Sub-Divisional Congress Committee, became the mouthpiece of the Jatiya Sarkar instead. The Sarkar also had its own postal system, as well as an intelligence agency and action squad called ‘Garam Dal’ (hot team) to act against those suspected of corruption, spying and anti-national activities.

Fazlul Haque, the Bengal Chief Minister said in an address to the legislative assembly, “Midnapore had a parallel government with its military and police forces and intelligence branch. It had its jails where people were imprisoned and, in some cases, the people had actually paralysed the government.” Governor Richard Casey informed Viceroy Lord Wavell in a note, “A high proportion of the inhabitants are in sympathy with the local ‘National Government’ or ‘Jatiya Sarkar’ as it calls itself.”

To be fair, the Jatiya Sarkar was one of at least three parallel governments (there was another in Satara, present day Maharashtra, and one in the United Provinces) which were formed as a consequence of micro-rebellions, after the British clampdown on the Quit India Movement. But—while each of these instances is remarkable in that, instead of a ‘national leader’ directing regional politics we see agency seized by grassroots leaders along the lines of local needs—the Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar stands out not just for its breathtaking audacity but also for the meticulousness with which it set out to execute its vision.

It lasted for 21 months, or nearly two years, till the 31st of August, 1944, after which the Sarkar was dissolved on the insistence of Gandhi. Within the 29th of September, in the same year, 150 Congress workers associated with the Jatiya Sarkar surrendered to the British Indian government.

This is the first in a new series titled ‘IHC Uncovers’, where we dig deep into archives as well as oral history, to shine a spotlight into lesser known or unknown narratives of Indian history. Our investigation into the Mahabharatiya Juktarashtra – Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar will consist of more than one instalment however. This is the first instalment, where we excerpt from primary sources uncovered from the archives of the Nehru Memorial Library as well as excerpts from a scholarly work, to introduce the Sarkar to you. We hope to, in the near future, bring you personal letters, press reports from the time and images which look at the role of youth in the Sarkar and outline the contours of Gandhi’s visit to this parallel government.

Pradyot Kumar Maity in Quit India Movement in Bengal and the Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar describes the Quit India Movement in Midnapore and the formation of a war council and the Bidyut Bahini as follows:

The Quit India resolution of 8 August and the arrest of Congress leaders including Gandhiji on the next day were “immediately followed by peaceful and non-violent popular demonstrations in the shape of hartals and processions over nearly the whole of India” and Tarmluk sub-division, our special field of study, is not an exception. Here also hartals were organised and numerous demonstrations were held after 9th August on many occasions before the government offices, police stations, and law courts, etc. Public meetings were also held in front of these places. The meetings and processions consisted of 5000 to 10,000 people irrespective of caste and creed. In those meetings, the Congress leaders tried to arouse national feeling among the masses and to unite them against the British oppression by reading and explaining the Quit India resolutions. One such meeting was held in front of Mahisadal thana and attended by about two thousand people. Mr. Wazir Ali Shaik, I.C.S., the sub-divisional officer of Tamluk, ordered the attending constables to arrest the speakers of the meeting, but the crowd refused to let them have arrested. Mr. Shaik then asked the constables to make a lathi charge to disperse the demonstrations. But the constables refused. This incident throws light on the solidarity of the freedom-loving masses as well as their faith on the leadership of the local Congress organisation. It is well recorded that hundreds of such meetings were arranged possibly with a view to make close mass contact so that the movement would be successful.

In the meantime, a new sub-divisional Congress Committee was formed and Ajoy Kumar Mukherjee became the secretary the SDCC. The students of this sub-division had played a great role in this movement. The student-force appears to have strengthened the hands of the Tamluk SDCC. Out of the volunteer corps known as Svechchhasevak Bahini that already existed in Mahisadal, Sutahata, and Tamluk thanas, a separate volunteer force, consisting of specially selected young men and students was set up first at Sundara under Mahisadal thana and then at Sutahata, Nandigram and Tamluk thanas. The students and the youths associated with the separate volunteer force received primary military training in drill and attack on the line of guerilla tactics as well as basic training to attend the casualties under the guidance of Sushil Kumar Dhara who commanded the volunteer corps of Mahisadal. Originally this corps had three branches, namely action, intelligence, and nursing. The Mahisadal volunteer corps of especially chosen persons named Bidyut Bahini was formally inaugurated on 26 September 1942 by the veteran Congress leader Sri Baradakanta Kuiti, though the said Bahini functioned since the middle of August. Women volunteers were also recruited at Sutahata and Mahisadal thana to form a Bhagini Sena (Army organisation of woman fighters). This Bhagini Sena scheduled to be inaugurated on the 17 October 1942 was inaugurated on 19 October by Sri Sushil Kumar Dhara at the Village Dariberia under Sutahata thana. Thus the army organisation including men and women was formed under the able guidance Sushil Kumar Dhara who led the militia of Tamluk during the Quit India movement. When the Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar was established this army organisation i.e., both Bidyut Bahini and Bhagini Sena became the National Army of the Jatiya Sarkar and then the total members of this Bahini rose to about five thousand.

Police-mass direct confrontation began in Tamluk sub-division on 8 September, 1942 when a crowd of about two thousand five hundred persons tried to stop the export of rice by the mill-owners at Danipur under Mahisadal thana. The police opened fire and killed three people. The dead bodies were not handed over to the people and were burnt in one single pyre. This enraged the people to a great extent. On the otherhand, to take revenge the District Magistrate raided the surrounding villages next day and arrested two hundred villagers. “They were made to sit in the sun the whole day. They were not given any food. Only thirteen persons were sent up and sentenced to different terms of imprisonment, ranging from 1 year to 2 years. The mill owners had to bow to public opinion. They were fined Rs. 2000/- which was promptly paid. Out of this Rs. 1500/- was paid to the families of the bereaved. The mill owners expressed regret for having exported paddy and promised not to do so in future.”

Another confrontation took place on the 27th September 1942 at Iswarpur in Nandigram thana where the police had gone to arrest two persons in the local congress office. A large crowd surrounded the police who at first set fire on the thatched house of the Congress office and then opened fire in order to find an escape route. As a result, four persons were dead and twenty-five persons were injured. Yet the mob followed the police party up to Narghat Police Camp, situated at a distance at about five K.M. from Iswarpur. To disperse the mob the police first used the lathi charge and then opened fire. The mob dispersed but they destroyed the Narghat ferry bulding, sub-registers office, boats, etc.

Almost similar firing incident occurred next day, 28 September 1942 at Brindabanpore, a nearby village of Iswarpur under Nandigram thana, As a result, two persons died of bullet injuries, and the three persons were seriously injured, Commenting on the police-mass confrontation the District Magistrate writes: “The villagers were roused to a state of fury… They were ready for a sort of guerilla warfare.”

Against this background, the War Council (Samar Parisad) of Tamluk subdivision already formed and the important Congress leaders in a meeting decided to organise mass action against the government, In the history of India’s freedom struggle, September 29, 1942 was remarkable day because on that day a concerted move was taken by the freedom fighters of Tamluk sub-division to occupy the police stations and government offices at Tamluk, Mahisadal and Sutahata purely on a peaceful manner. On the next day, similar attempt was made at Nandigram P.S. of the same sub-division. No such attempts were made at Panskura and Moyna police stations – both belonging to Tamluk sub-division, due to the lack of proper Congress Organisation.

Detailed preparations were made for raiding the police stations and steps were made to assemble as many persons as possible and to isolate the police – station buildings from the outside help. During the night of 28 September, the important link roads of Tamluk sub-division were cut off at several points and many culverts on the roads were broken. Big trees were fallen to block the roads and big holes were dug on the road. Telegraph and telephone lines were cut off.

Tamluk, Mahisadal, and Sutahata Police Stations were raided on the afternoon of the 29 September. At Tamluk town about twenty thousand people marched on towards the Police Station in five processions from different connecting roads, and the seventy-three year old woman Satyagrahi, Matangini Hazra, a widow who was at the head of one such procession was shot at and she died a martyr’s death, still holding on the national flag in her hand. Besides Matangini, other nine persons including Lakshminarayan Das (13) and Purimadhab Prarmanik (14) died martyr’s death on that day at Tamluk town. The Mahisadal police station was raided by a crowd of about 20000 people and heavy firing killed thirteen persons here. Whereas the Sutahata police station fell to the raiders numbering about 40000 persons. The O.C. of the police station and other constables were at once made disarmed and the crowd led by the Bidyut Bahini set fire to the police station building.

The Nandigram police station was raided on the 30 September by a crowd of 10000 persons. As a result of the police firing, four persons died on the spot and another person died later on at the Tamluk Government Hospital.

Though heavy firing had beaten back the mob in three police stations, practically between 29th and 30th September civil administration collapsed in Tamluk sub-division. The region under survey had passed under the control of the Congress organisation which attempted to cut off the police stations from the sub-divisional headquarter. Even attempts were made to isolate the letter from the district headquarter i.e. Midnapore. This chaotic situation had been well recorded by the District Magistrate who writes that “large crowds of peasantry are roaming all over the countryside ready to fall on and overpower any small government agency.”

The people of the Tamluk sub-division became so anti-government that they went on destroying the government offices of any kind, roads, telegraph, and telephone lines with a view to paralyse the British administration there. Referring to these disturbances M.M. Basu, L.C.S. Additional District Magistrate, Midnapore made the remark that “the attacks take place so suddenly and simultaneously that no preventive action could be taken beforehand. In many places, information about threatened attacks was received extremely late owing to the fact that communication had been seriously sabotaged and information had to be sent by special messengers who had to select devious routes for avoiding molestation on the way.”

This national upsurge which was characterized by Herbert, Governor of Bengal, as a “large scale rebellion” made the government very much worried. To cope with the situation military reinforcements were arranged very quickly. But still, the people showed determined courage to oppose military move here and there. Such opposition often resulted in firing. Commenting on it M.M. Basu, A.D.M. writes: “The mob in Tamluk sub-division is apparently not afraid of (police or military) firing.” Almost similar observation had been made by Superintendent of police who felt that “the troops who come should have automatic weapons (Brenguns and Tommyguns) and unlimited ammunition. One can never be sure as to what lengths they (the nationalist rebels) will go.” From these observations and from other Government sources it is known that the people in general were very hostile and unsympathetic to the government… As the movement assumed a vigorous form in the Tamluk sub-division, Indian Gurkha and British soldiers were posted by founding camps in different parts of the sub-division to crush the movement. From these camps they used to go to the villages for raiding and they oppressed men and women … While raiding, the police did not hesitate to commit rape… physical torture, arrest, burning of houses and similar other destructive and punitive measures were regularly carried out by the police.

Midnapore was struck with a cyclonic storm followed by a tidal wave on October 16, 1942, exacerbating the famine Bengal was facing at the time.

Pradyot Kumar Maity’s Quit India Movement in Bengal and the Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar describes this:

In spite of severe repression, the Congress leaders of this sub-division decided to continue the movement … The apathetic British Government took no steps to relieve the woes of the famine-stricken people fighting for freedom. Even the government did not allow private organisations to do the relief work for a pretty long time at Tamluk and Contai sub-divisions. Further the government deliberately delayed to air the news of the havoc caused on 16th October. The reason was to crush the anti-British movement which took a serious character in comparison with other places of India. However, the local Congress leaders took a challenge and organised the ‘Mahendra Relief Committee’ at Tamluk…

A section of Mookerjee’s letter to the Governor of Bengal – Sir John Herbert – 16th November 1942

“The reports which I have received about the callousness and indifference of some of the officers even after the cyclone perhaps find no parallel in the annals of civilized administration. The suppression of news of the havoc by Government and even of appeals for help for more than a fortnight, was criminal. In the presence of the District Magistrate, complaints were received that boats were not made available on that fateful evening or even later to save the lives of the people who were perilously resting for a brief while on the roofs of their houses that ultimately collapsed. One gentleman gave a harrowing description of the manner in which he and others begged of officers to allow a boat found by them to ply for a couple of hours in order to rescue some men,.women and children lying near the area concerned. This request was summarily rejected and the men who had used the boat were threatened with dire consequences. Later on, all the people whom this party wanted to rescue were washed away, never to be found again. After the cyclone, curfew orders continued even in areas where people offered every co-operation. Our intervention in this respect proved fruitless. Transport facilities and movements were extremely restricted even when we visited the district a fortnight later. Cows were requisitioned under the Defence of India Rules. The total destruction of cattle owing to flood and storm would be somewhere between seventy-five and eighty-five percent. Of the cows that remained, although they were giving milk and some were with calf, a good many were snatched away from private houses by the police and the military for the purpose of feeding the troops. Such inhuman callousness is indeed unparalleled. One officer’s report in writing to Government was that relief, whether organised by Government or any private agency, should be withheld for a month and thereby people taught a permanent lesson. Relief measures adopted by local officers were utterly inadequate. Even bonafide private relief workers from Calcutta though they produced their credentials, found themselves in jail under the Defence of India Rules.”

Mookerjee’s letter to the chief minister of the Government of Bengal A.K. Fazlul Huq – 17th January 1943.

“Harrowing tales of loot and destruction of properties of civil population and outrage on ladies in certain villages within Mahisadal P.S. in Tamluk, have reached us from various independent sources. These incidents took place on saturday, the 9th of January last. It is alleged that about one hundred and fifty armed men (it is not clear if these were members of troops or of armed police force) surrounded in the morning the villages of Masuria, Chak Gazipur, Chandipur and Lakhya in Union No. 11, Mahisadal P.S.. They divided themselves into various groups and posted themselves at different points on the main road leading to different villages as also in bushes near about.

Then they carried on searching enquiries into individual houses, forcibly removed the menfolk under arrest and detained them at various places till afternoon. It is alleged these detained persons were severely beaten and some were rendered senseless.

Meanwhile, some of these armed men re-entered into the houses of these villagers, committed outrage on a large number of ladies, destroyed the belongings and decamped with cash and valuables.

I have in my possession written statements of some of the sufferers, including ladies, giving most pathetic descriptions of the incident. The crimes alleged to have been committed were brutal, revolting and unprovoked.

It is essential that there should be an immediate investigation so that the guilty men may be adequately dealt with and proper steps taken to avoid recurrence of such incidents. As you are aware, in such cases panic-stricken people are afraid of giving full information unless they are guaranteed protection. I would request you to visit the place of occurrence yourself or at least to depute one of the Ministers, who should be accompanied by one or two leading non-official gentlemen. There are feelings of great resentment and consternation among the local people some of whom have seen me personally. Action should be immediately taken to protect life and honour of peaceful citizens in areas already greatly affected by acts of both men and nature

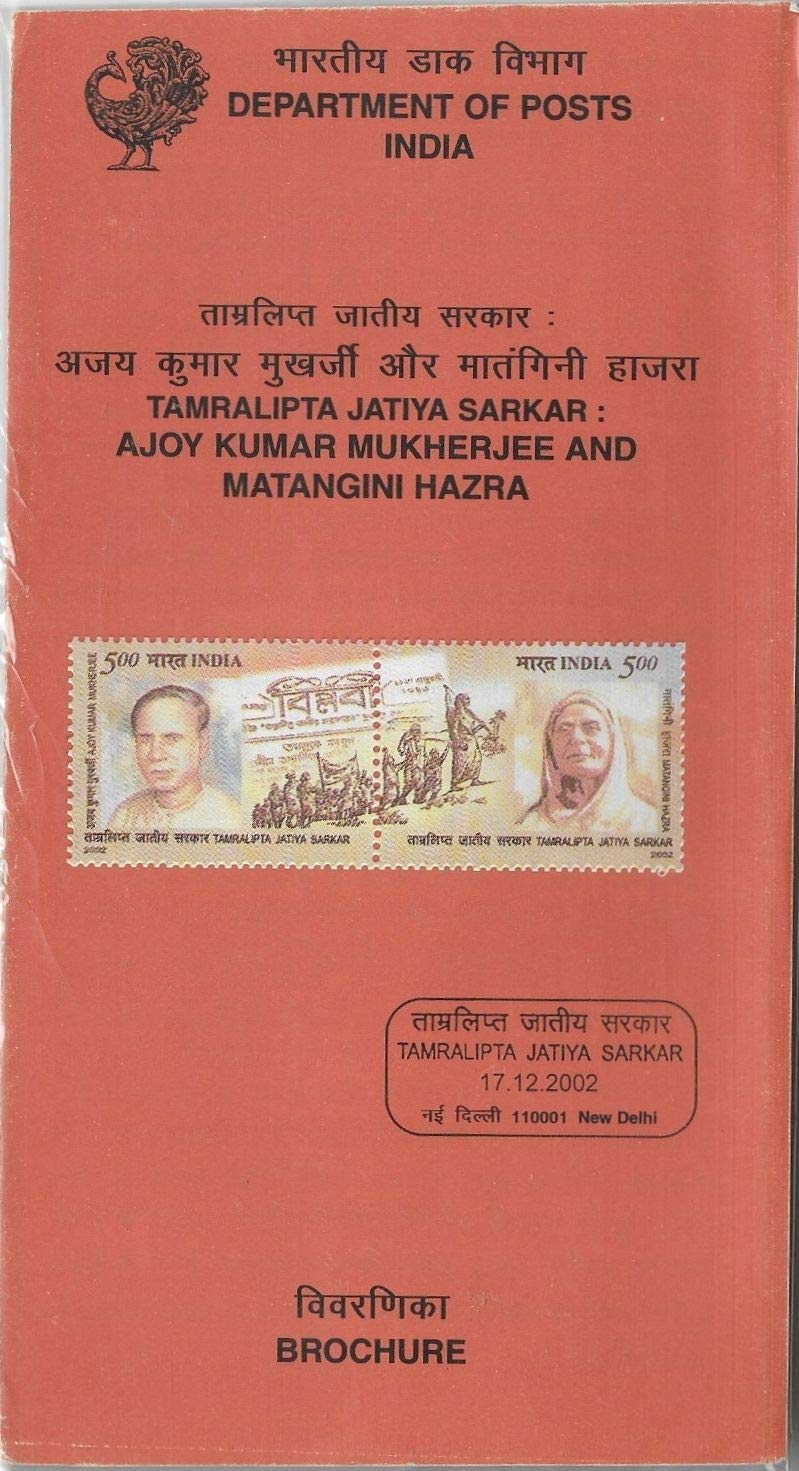

(2002) Commemorative Stamp of the movement

The Mahabharatiya Juktarashtra – Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar was established on the 17th of December, 1942, by the Tamluk sub-divisional Congress Committee at the Tamluk subdivision, with the aim of destroying the British Government in the area and offer better administration to the people as well as transform free India into a ‘Mahabharatiya Juktarashtra’ (great Indian union of states).

Tamralipta is held by some scholars (though this is disputed by others) to be an ancient port city located where present day Tamluk is, in West Bengal. ‘Jatiya’ indicates ‘community’.

The bulletin Biplabi (revolutionary) became the government mouthpiece.

The pamphlet announcing this parallel government read:

“The people of the sub-division (of Tamluk) have come to the clear conclusion that the heartless hypocrisy of official relief or even the most sincere efforts of the non-official organisations will not be able to save them from the impending calamities of severe famine and devastating epidemic. But complete lawlessness and barbaric repression will continue unabated. Consequently within a short period of time this region will turn into a vast graveyard- not a single man will be spared… The people of Tamluk should try to do everything within their power in the final attempt to live in freedom by ending this state of chaos and lawlessness and by establishing peace and order.” (as translated from Bengali by Pradyot Kumar Maity)

Pradyot Kumar Maity’s Quit India Movement in Bengal and the Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar lays this out as follows:

The constitution of this government was in accordance with the following procedure:

These departments were

i) Law and Order,

ii) Finance,

iii) Education,

iv) War,

v) Administration of Justice,

vi) Home and Defence.

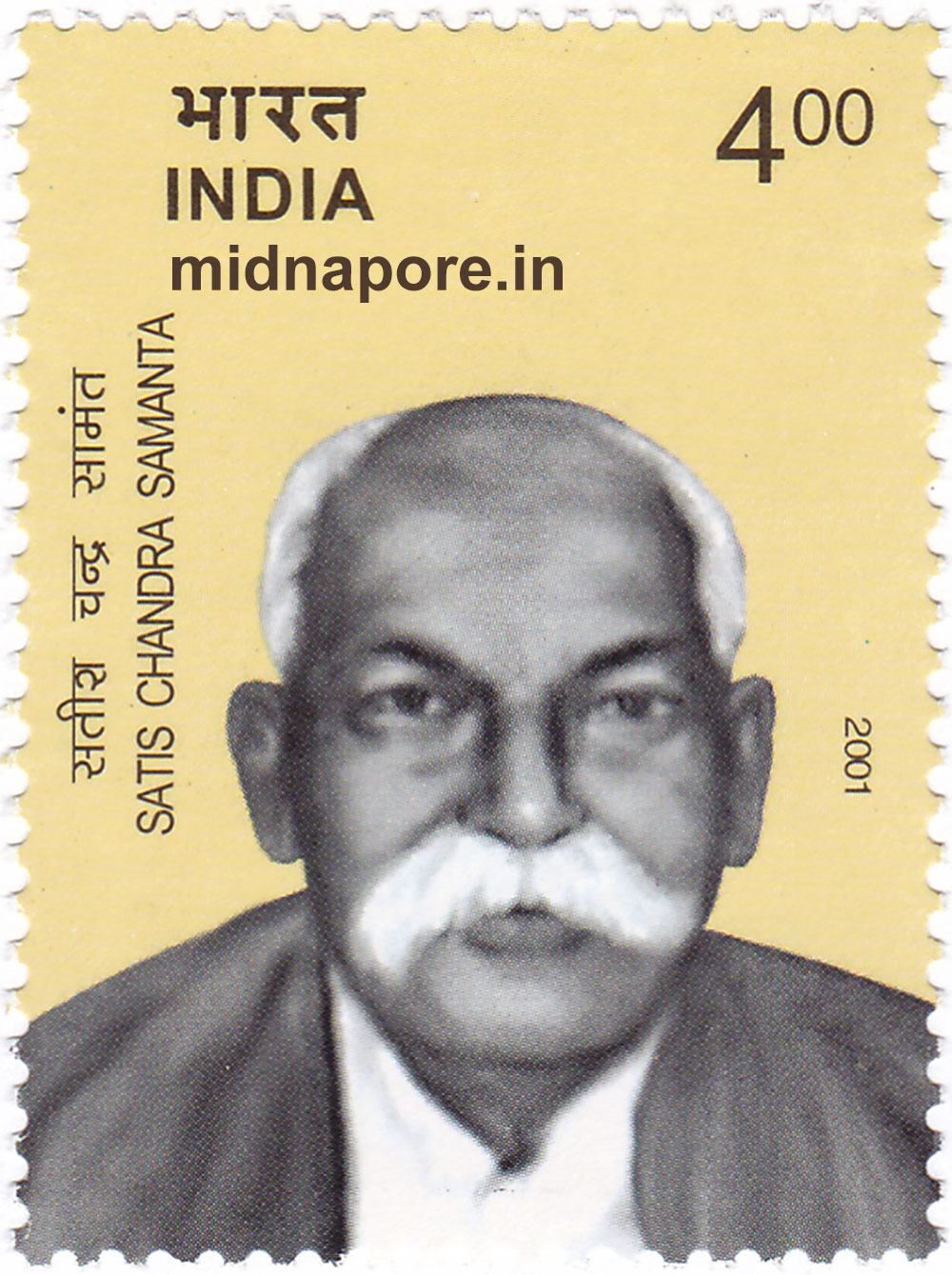

It is to note that on account of the exceptional circumstances of those days of turmoil, elections could not be held. So appointments were made by the Sub-divisional Congress Committee. The Sarbhadinayak was to act freely within the limits set by the Congress Committee. He himself was the war Minister. The first Sarbhadinayak was Satish Chandra Samanta, a veteran leader of the Sub-division. The successive Sarbhadinayaks were Ajoy Kumar Mukherjee, Satish Chandra Sahoo and Barada Kanta Kuiti, all veteran leaders of the Sub-division. Ajoy Kumar Mukherjee became the Finance Minister. Sushil Kumar Dhara, the organiser of the Bidyut Bahini and Bhagini Sena was in charge of the Home and Defence Ministry. The Bidyut Bahini and the Bhagini Sena became the National Militia of the Jatiya Sarkar, the Commander-in-Chief of which was Sushil Kumar Dhara. Mr. Dhara, a legendary figure of the movement also organised a Garam Dal, an action squad to take strong measures against those who were suspected of corruption, spying and anti-national activities. Besides the persons mentioned above, there were other persons who were in charge of the different departments of the Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar. Under the able and efficient leadership, the Jatiya Sarkar gained wide popularity which it enjoyed undiminished till and after the day of its voluntary dissolution.

Now a brief description of the working of the different departments of the Jatiya Sarkar is narrated here:

This was the most popular department of the Jatiya Sarkar. Each Thana Jatiya Sarkar had a Department of Justice in charge of a Minister of Justice. The fee for filing a case was Rs. 1 later changed to Rs. 2.

An additional fee of Rs. 2 was charged from January 1, 1944 for emergency cases. Both civil and criminal cases were adjudicated. Against the order and judgement of the Thana Jatiya Sarkar Court, an appeal lay to the Sub-Divisional Court of the Jatiya Sarkar. Against the order and judgement of this latter court an appeal lay to the Special Tribunal consisting of three judges.

The court used to move and sit in different places to suit the convenience of the public. The public were allowed to be present at the time of the sitting of the court. Sometimes as many as 200 to 300 persons would be present. Many long-standing cases of the Sub-Divisional and District Courts and the High Courts were adjudicated successfully by the Jatiya Sarkar Courts. Sometimes lawyers and mukteers were present… In criminal cases the accused who were found guilty were given different punishments according to the nature of the offence. Warning, fine, detention till the rising of the Court, whipping etc. had been resorted to, in order to meet the ends of justice. Property of absconders was sometimes attached and in some cases, sold in public auction. In the execution of decree, property was in some cases attached. But attachment and sale were allowed only in a few rare cases. For instance, where persuasion failed. The prestige of the Jatiya Sarkar was, however, so high as to bring about settlement through its courts in most cases and get a ready obedience to its decisions. In Sutahata Jatiya Sarkar Court, 836 cases were filed, in Nandigram 222 cases, in Mahisadal 1055 cases and in Tamluk 794 cases. A total of 2,907 cases were instituted. Out of these 1,681 cases were adjudicated. A few cases came up for decision before the Sub-Divisional Court and a few before the Tribunal. Before the dissolution of the Jatiya Sarkar, the depositors of fees of pending cases were given back their money. So high was the Jatiya Sarkar’s prestige that many people were reluctant to take their fees and wanted the Jatiya Sarkar Court to try their cases when it might be revived.

It was, of course, mainly concerned with the resistance movement and for checking the offensive measures of the Government. As, however, the distress caused by the cyclone and famine became acute, aggravated by a deliberate policy of bungling and mismanagement by the authorities, the War Department paid greater attention to relief.

These departments tried their utmost to combat famine and pestilence. Clothing, paddy, rice and money were collected at different places and distributed among the needy. The rice hoarders and profiteers were served with notices by the Jatiya Sarkar to stop exploitation and they were made to pay fair sums of money and paddy which were distributed among the distressed people. In the acute days of famine, the members of the army camp of the Jatiya Sarkar first subsisted on one meal of boiled gram and one meal of rice and then, for nine continuous months, they lived on one meal of 3 chataks of rice and another meal of ½ poa of boiled or fried gram. Medicines of many varieties were distributed. In all Rs 79,000 worth of clothes, medicines, paddy and rice were distributed.

This department with the help of the Intelligence Branch maintained peace in the sub-division. It was responsible for arresting and punishing a good number of thieves and dacoits. Notorious dacoits had been released and encouraged to commit all sorts of offences and on many occasions, the police station refused to give any aid to persons suffering from the depredations of these people. On Jatiya Sarkar taking firm steps to prevent the crimes, they stopped and only a few cases of thefts and dacoities were reported, which also received prompt attention from the Jatiya Sarkar. The Jatiya Sarkar’s remedy was speedy, effective, inexpensive and to the entire satisfaction of all sections of people.

Many schools received regular grants in aid. Schools were regularly inspected by competent inspectors.

Besides these departments there were also the Propaganda and Finance Departments, each headed by a Minister.

(2001) Commemorative stamp of the first Sarbadhinayak or Dictator of the Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar. Image credits – midnapore.in

The Role of Women in the Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar

Maity’s Quit India Movement in Bengal and the Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar describes this in detail:

The participation of women as volunteers known as Svechchhasevak and then as a member of the Bhagini Sena (army organisation of women) were stages of involment in the movement. We have already noticed that when the Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar was established, both the Bidyut Bahini and the Bhagini Sena became the National Army of the Jatiya Sarkar. While the National Army was in the charge of Sushil Kumar Dhara, the Bhagini Sena was in the charge of a woman named Subodhbala Kuiti.

The then Congress organisation also selected a woman dictator for each thana and for the sub-division with the air of inspiring women to take part in the movement in greater numbers. A panel of five dictators for the sub-division was made including Suhasini Devi, Indumati Bhattacharya, Lakshimani Mukherjee, Nityabala Gol and Subodhbala Kuiti. The panel was made so because whenever one would be arrested, the next one from the panel would function as sub-divisional dictator. The thana Dictators were Rajlakshmi Singha (Tamluk), Lakshimani Hazra (Mahisadal) Prabhabati Singha (Sutahata), Prabhabati Maiti (Mayna), Chikanbala Jana (Nandigram) and Kiranbala Devi (Panskura). These thana dictators used to maintain regular contact with the sub-divisional dictator.

Against the background of raping and other torture perpetrated on women by the British police and soldiers, the organiser of Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar, handed over daggers numbering about ten thousand to women so that they could save themselves from brutal attack of the police and the soldiers. Again they were advised to stay in a group when the police force entered a village. Further they were advised to announce the entry of police force or of soldiers in a village by blowing conches. In these ways the women of Tamluk sub-division made themselves prepared for fighting against British imperialistic torture and repression during the course of the Quit India Movement. They helped in the following ways to make the movement a success in their areas:

First, they participated in large numbers in the processions led to occupy the police stations and government offices, purely in a peaceful manner, on the 29th September (30th November at Nandigram P.S.), 1942.

Second, a few women took active part by associating themselves in different organisational activities to strengthen the movement. They were Kadambini Maiti, Matangini Hazra, Saratkumari Samanta, Saralasundari Mandal (under Tamluk P.S.), Khukibala Pramanik, Charusila Jana, Charusila Kuiti, Niradamayee Das, Parulbala Samanta, Parulbala Maiti, Bhagabati Mahapatra, Radharani Patra, Sovarani Mankar (under Sutahata P.S.), Annapurna Maiti, Amiyalata Singha, Ashalata Jana, Indumati Chatterjee, Indumati Dhara, Jnandamayee Das (under Mahisadal P.S.), Charubala Pramanik, Bangabala Pal, Rajabala Chakraborti, Subasini Samanta (under Nandigram P.S.), Prabhabati Maiti (under Moyna P.S.) and Bibharani Chakraborti (under Panskura P.S.).

Third, many women helped the movement by offering food and shelter to the freedom fighters or by assisting otherwise. Among these a few deserve special mentions. Kadambini Maiti (the bulletin ‘Biplabi’ was printed at her house), Khukibala Pramanik (the office of the Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar existed at her house which was also the place of residence of the workers of Bidyut Bahini), Gangamani Sautia and Chanchalabala Mandal (who served as cooks at the camps of the Jatiya Sarkar), Niradamayee Das, Makhanbala Maiti, Jogamaya Pal, Ramanirani Bera, Labangalata Samanta, Sadhanabala Pradhan and Saralabala Devi, a sex worker (they gave food and shelter to the freedom fighters), Makhanbala Singh (a few workers of the Bidyut Bahini also resided at her house), Sobharani Mankar (she used to sing patriotic songs to stir up national feeling among people attending different congress meetings), Ashalata Jana (she helped to maintain communication), Indumati Chatterjee (the Congress office of Mahisadal P.S. and the camp of Bidyut Bahini existed on her lands), Dhirenbala Bag (her house became the camp of Thana Jatiya Sarkar for a long time).

Fourth, a few women also encouraged their husbands to participate in the movement. They were Prabhabati Devi, Parulbala Samanta, Kiranbala Bera, Makhanbala Maiti, Jogamaya Pal, Labangalata Samanta, Surjamukhi Bishoi (of Sutahata P.S.), Indumati Chatterjee, Dhirenbala Bag (of Mahisadal P.S), Charubala Pramanik and Charubala Sanki (of Nandigram P.S).

Fifth, by joining the ‘Bhagini Sena’ (the army of women fighters) they strengthened the movement.

Sixth, three women became members of the ‘Garam Dal’ (Action Squad). Those who acted as spies of the British Government, were punished by this Garam Dal. Among total members of fifty, there were only three female members in this organisation. They were Jyotsna Das, Usha Chaudhuri and Kumudini Dakua.

Seventh, a few of them, namely Subodhabala Kuiti, Kumudini Dakua and Giribala De, participated as speakers in the meeting organised by SDCC for mobilising public opinion— especially among women in favour of the movement.

Finally, the role of a sex worker of Tamluk town deserves special mention in this connection. On 29th September, 1942, the day of peaceful occupation of police stations and government offices by the processionists, Sabirtri Devi, a sex worker, demonstrated great bravery. On that day many processionists were wounded due to police firing and lathi charge. To nurse them Sabitri Devi ran in with a big pot full of water. The soldiers with their guns set to fire asked her not to proceed but she did not care. She nursed the wounded. The female processionists, after collecting bantis (vegetable-cutters) from nearby houses, assisted Sabitri Devi. The soldiers remained indifferent. Sabitri became a hero on that day and henceforth she associated herself with the SDCC of Tamluk in its secret activities as a freedom fighter.

From all these facts one may surmise how the women of Tamluk subdivision involved themselves in the Quit India Movement. The formation of the Bhagini Sena was very significant. It was formed with a view to save the honour of women of the locality. As far as our knowledge goes, no such woman army organisation was formed in any part of India in connection with this movement. (It may well be the case that the formation of Bhagini Sena had influenced the organisers of I.N.A to form the Jhansi Rani Brigade in August, 1943.)

As the women of our place of study participated in greater numbers, they had to suffer in various ways.

1) The military and police have been accused of 73 rapes in connection with this movement. On a single day (January 9, 1943) 46 women from three villages—Chandipur, Masuria and Dihi-Masuria (under Mahisadal P.S.)—were raped.

2) Minor assaults on women were numerous. In many cases the police took away the ornaments of the women on their persons. In some cases they tore earrings off women’s ears.

4) In some cases women, including old women and young girls, were whipped to extract information about the organisers of the movement.

5) Many women suffered imprisonment ranging from one and half months to a year.

6) A seventy three year old woman, Satyagrahi Matangini, suffered a martyr’s death on the 29th of September, 1942.

It is further important to note that though most of the women participants of this movement were illiterate, yet their enthusiasm and love for freedom made them bear untold sufferings as stated above.

The reasons are not far off to seek. The programme of close mass contact since 1930, followed by the Gandhian Congress leaders of SDCC of Tamluk, helped the people of this area in general, and women in particular, to involve themselves in the Quit India movement in great numbers.

Thus, it may be concluded that the role of women of Tamluk subdivision in the Quit India Movement was unparalleled in the history of the freedom movement in India.

Aims to make widely available primary sources, work by professional historians and scholars and writers who bring a fresh insight to historical understanding.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply