The British Museum

The first edition of Jadunath Sarkar’s Shivaji and His Times was published in 1919. The excerpt that we are carrying below is from the fifth edition of the same book, published in 1952, six years before Sarkar passed away.

Shivaji and His Times is considered a classic work of medieval history, particularly noteworthy for the range of sources, and the depth of research, that has gone into making it. Henry Beveridge, an orientalist and ICS officer in British India wrote: “All his books are good; but perhaps the best of them is the Life and Times of Shivaji. It is full of research, and gives a striking picture of the great event – the birth and development of the Maratha nation.” Indologist and historian Vincent Arthur Smith said that Sarkar’s reputation as “a sound critical historian” would be “confirmed and extended” by this work. And that the “bold and deliberately provocative book merits the closest study”.

We have chosen to carry the concluding chapter of the book: ‘Shivaji’s Achievement, Character and Place in History’. As with the rest of the book—which, more than the biography of one person is the painstaking reconstruction of a time and a society—so in this chapter, Sarkar uses carefully chosen detail to lay out the context in which we may evaluate Shivaji’s legacy. This context comprises a detailed and incisive look at Maratha society and government, institutions and economic and foreign policy.

Divided into nine sections, the chapter begins with an investigation into “mulk-giri” (a concept used to describe raids into neighbouring countries as well as any extortion of consideration when the raiders agree to refrain from raiding) and how this fitted into the foreign policy of Shivaji as well as Muslim rulers. It goes on to examine the reasons for Shivaji’s failure in building a lasting State: the leading cause among these being caste quarrels but also the greed for land and status based subdivisions within Hindu society (even within castes) as well as leaders being blind to the people’s interests. Sarkar goes on to expose flaws in the Maratha economic policy and explain how a Krieg-staat (a Government that lives and grows only by wars of aggression) could never succeed in the long run. Finally, he criticizes the Maratha over-reliance on intrigue and “diplomatic trickery” and puts this down as a reason for them being crushed by “the mailed fist of Wellesley”. “The man of action, the soldier-statesman,” writes Sarkar. “Always triumphs over the mere scheming Machiavel.”

This brings us finally to Sarkar’s portrait of Shivaji: an analysis of his character, his genius and the reasons for his success despite such odds (this includes, among various other factors, “his impartial respect for the holy men of all sects, Muslim as much as Hindu, and toleration of all creeds”). “When he chose to declare his independence,” writes Sarkar. “The Mughal empire seemed to be at the height of its glory. Every local chief who had, anywhere in India, revolted against it had been crushed. For a small jagirdar’s son to defy its power, appeared as an act of madness, a courting of sure ruin. Shivaji, however, chose this path, and he succeeded.”

Sarkar makes allowances for Shivaji not being able to “work out his political ideal” (i.e. beyond a Krieg-staat) due to the constant conflicts he was engaged in, coupled with the relatively short duration of his reign. In this context, Sarkar examines the complex Maratha relationships with the Mughal empire as well as the state of Bijapur. Sarkar ends—in a section titled ‘His influence on the spirit’—with his interpretation of Shivaji’s legacy in terms of what it meant to Marathas and Hinduism in India.

The chapter is most notable for the detail Sarkar employs to bring alive another time, another place. “The society of Shivaji’s age and country was so different from our own that some straining of the historical imagination is necessary before we can understand the difficulties that he had to combat,” he writes. And contributes significantly in enabling us to achieve this.

Shivaji’s Achievement, Character and Place in History

Shivaji’s State policy, like his administrative system, was not very new. From time immemorial it had been the aim of the typical Hindu king to set out early every autumn to “extend his kingdom’ at the expense of his neighbours. Indeed, the Sanskrit law-books lay down such a course as the necessary accomplishment of a true Kshatriya chief. (Manu. vii. 99-103, 182.) In more recent times it had also been the practice of the Muhammadan sovereigns in North India and the Deccan alike. But these conquerors justified their territorial aggrandisement by religious motives. According to the Quranic law, there cannot be peace between a Muhammadan king and his neighbouring “infidel” States. The latter are dar-ul-harb or legitimate seats of war, and it is the Muslim king’s duty to slay and plunder in them till they accept the true faith and become dar-ul-islam, after which they will become entitled to his protection.

The coincidence between Shivaji’s foreign policy and that of a Quranic sovereign is so complete that both the history of Shivaji by his courtier Krishnaji Anant and the Persian official history of Bijapur use exactly the same word, mulk-giri, to describe such raids into neighbouring countries as a regular political ideal. The only difference was that in theory at least, an orthodox Muslim king was bound to spare the other Muslim States in his path and not to spoil or shed the blood of true believers, while Shivaji (as well as the Peshwas after him) carried on his mulk-giri into all neighbouring States, Hindu no less than Islamic, and squeezed rich Hindus as mercilessly as he did Muhammadans. Then, again, the orthodox Islamic king, in theory at least, aimed at the annexation and conversion of the other States, so that after the short sharp agony of conquest was over those places enjoyed peace like the regular parts of his dominion. But the object of Shivaji’s military enterprises, unless his Court-historian Sabhasad has misrepresented it, was not annexation but mere plunder, or to quote his very words, “The Maratha forces should feed themselves at the expense of foreign countries for eight months every year, and levy blackmail.” (Sabh., 26.)

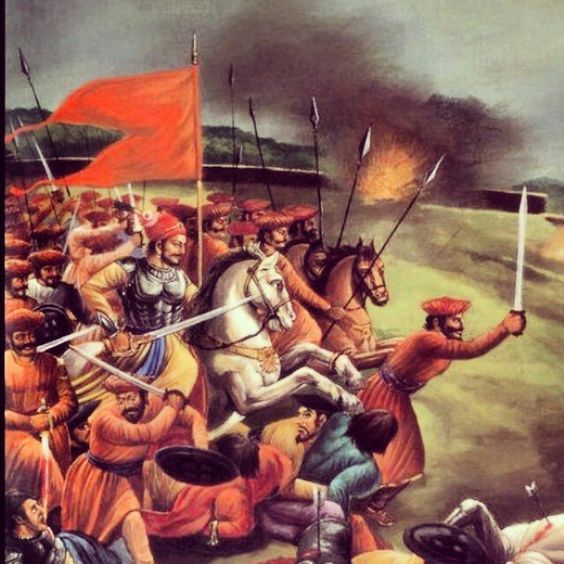

An artist’s representation of a Maratha attack

(“Instead of commencing with the removal of the existing government, and the general assumption of the whole authority to himself, a Maratha chieftain begins, by appearing at the season of harvest, and demanding a consideration for his forbearance in withholding the mischief he has it in his power to inflict. This visit is annually repeated, and the demand proportionally enhanced. Whatever is thus exacted is called the chauth, and the process of exaction a mulk-giri expedition.” (Prinsep’s History… of the Marquess of Hastings, i. 22.))

Thus, Shivaji’s power was exactly similar in origin and theory to the power of the Muslim States in India and elsewhere, and he only differed from them in the use of that power. Universal toleration and equal justice and protection were his distinctive features in the permanently occupied portion of his realm, as we have shown elsewhere.

The coincidence between Shivaji’s foreign policy and that of a Quranic sovereign is so complete that both the history of Shivaji by his courtier Krishnaji Anant and the Persian official history of Bijapur use exactly the same word, mulk-giri, to describe such raids into neighbouring countries as a regular political ideal. The only difference was that in theory at least, an orthodox Muslim king was bound to spare the other Muslim States in his path and not to spoil or shed the blood of true believers, while Shivaji (as well as the Peshwas after him) carried on his mulk-giri into all neighbouring States, Hindu no less than Islamic, and squeezed rich Hindus as mercilessly as he did Muhammadans. Then, again, the orthodox Islamic king, in theory at least, aimed at the annexation and conversion of the other States, so that after the short sharp agony of conquest was over those places enjoyed peace like the regular parts of his dominion.

Why did Shivaji fail to create an enduring State? Why did the Maratha nation stop short of the final accomplishment of their union and dissolve before they had consolidated into an absolutely compact political body?

An obvious cause was, no doubt, the shortness of his reign, barely ten years after the final rupture with the Mughals in 1670. But this does not furnish the true explanation of his failure. It is doubtful if with a very much longer time at his disposal he could have averted the ruin which befell the Maratha State under the Peshwas, for the same moral canker was at work among his people in the 17th century as in the 18th. The first danger of the new Hindu kingdom established by him in the Deccan lay in the fact that the national glory and prosperity resulting from the victories of Shivaji and Baji Rao I created a reaction in favour of Hindu orthodoxy; it accentuated caste distinctions and ceremonial purity of daily rites which ran counter to the homogeneity and simplicity of the poor and politically depressed early Maratha society. Thus, his political success sapped the main foundation of that success.

In the security, power and wealth engendered by their independence, the Marathas of the 18th century forgot the past record of Muslim persecution; their social grades turned against each other. The Brahmans living east of the Sahyadri range despised those living west of it, the men of the hills despised their brethren of the plains, because they could now do so with impunity. The head of the State, though a Brahman, was despised by his Brahman servants belonging to other branches of the caste— because the first Peshwa’s great-grandfather’s great-grandfather had once been lower in society than the Desh Brahmans’ great-grandfathers’ great-grandfathers! While the Chitpavan Brahmans were waging social war with the Deshastha Brahmans, a bitter jealousy raged between the Brahman ministers and governors and the Kayastha secretaries. We have unmistakable traces of it as early as the reign of Shivaji. “Caste grows by fission.” It is antagonistic to national union. In proportion as Shivaji’s ideal of a Hindu swaraj was based on orthodoxy, it contained within itself the seed of its own death. As Rabindranath Tagore remarks :

“A temporary enthusiasm sweeps over the country and we imagine that it has been united; but the rents and holes in our body-social do their work secretly; we cannot retain any noble idea long.

“Shivaji aimed at preserving the rents; he wished to save from Mughal attack a Hindu society to which ceremonial distinctions and isolation of castes are the very breath of life. He wanted to make this heterogeneous society triumphant over all India! He wove ropes of sand; he attempted the impossible. It is beyond the power of any man, it is opposed to the divine law of the universe, to establish the swaraj of such a caste-ridden, isolated, internally-torn sect over a vast continent like India.”

(From his Rise and Fall of the Sikh Power, as translated by me in Modern Review, April 1911.)

The first danger of the new Hindu kingdom established by him in the Deccan lay in the fact that the national glory and prosperity resulting from the victories of Shivaji and Baji Rao I created a reaction in favour of Hindu orthodoxy; it accentuated caste distinctions and ceremonial purity of daily rites which ran counter to the homogeneity and simplicity of the poor and politically depressed early Maratha society. Thus, his political success sapped the main foundation of that success.

Shivaji and his father-in-law Gaikwar were Marathas, i.e., members of a despised caste. Before the rise of the national movement in the Deccan in the closing years of the 19th century, a Brahman of Maharashtra used to feel insulted if he was called a Maratha. “No,” he would reply with warmth, “I am a Dakshina Brahman.” Shivaji keenly felt his humiliation at the hands of the Brahmans to whose defence and prosperity he had devoted his life. Their insistence on treating him as a Shudra drove him into the arms of Balaji Avji, the leader of the Kayasthas, and another victim of Brahmanic pride. The Brahmans felt a professional jealousy for the intelligence and literary powers of the Kayasthas, who were their only rivals in education and Government service, and consoled themselves by declaring the Kayasthas a low caste not entitled to the Vedic rites and by proclaiming a social boycott of Balaji Avji who had ventured to invest his son with the sacred thread. Balaji naturally sympathised with his master and tried to raise him in social estimation by engaging Gaga Rhatta who “made Shivaji a pure Kshatriya”. The high-priest showed his gratitude to Balaji for his heavy retainer by writing a tract [or rather two] in which the Kayastha caste was glorified, but without convincing his contemporary Brahmans.

(Nor has he succeeded in convincing posterity. In 1916, Mr. Rajwade, a Brahman writer, published a denial of the Kayastha claims (Chaturtha Sam. Britta), on the occasion of editing this tract. He has provoked replies, one of which, Rajwade’s Gaga Bhatti by K. T. Gupte makes some attempt at reasoning and the use of evidence, while another, The Twanging of the Bow by K. S. Thakre, has the same tone as Milton’s Tetrachordon or Against Salmasius! This is happening in the 20th century, and yet Mr. Rajwade and Prof. Bijapurkar—who persistently treated Shivaji’s descendants at Kolhapur as Shudras—are nationalists, even Chauvinists. It was with a house so divided against itself that the Puna Brahmans of the 18th century hoped to found an all-Indian Maratha empire, and there are Puna Brahmans in the 20th century who believe that the hope failed only through the superior luck and cunning of the English!)

There was no attempt at well-thought-out organised communal improvement, spread of education, or unification of the people, either under Shivaji or under the Peshwas. The cohesion of the people in the Maratha State was not organic but artificial, accidental, and therefore precarious. It was solely dependent on the ruler’s extraordinary personality and disappeared when the country ceased to produce supermen among its rulers.

A Government of personal discretion is, by its very nature, uncertain. This uncertainty reacted fatally on the administration. However well-planned the machinery and rules might be, the actual conduct of the administration was marred by inefficiency, sudden changes, and official corruption, because nobody felt secure of his post or of the due appreciation of his merit. This has been the bane of all autocratic States in the East and the West alike, except where the autocrat has been a “hero as king” or where a high level of education, civilization and national spirit among the people has prevented the evil.

There was no attempt at well-thought-out organised communal improvement, spread of education, or unification of the people, either under Shivaji or under the Peshwas. The cohesion of the people in the Maratha State was not organic but artificial, accidental, and therefore precarious. It was solely dependent on the ruler’s extraordinary personality and disappeared when the country ceased to produce supermen among its rulers.

The society of Shivaji’s age and country was so different from our own that some straining of the historical imagination is necessary before we can understand the difficulties that he had to combat.

Land was the only stable thing in an ever-changing world subject to the appalling outbursts of nature’s forces, which swept away man and his handiwork, and the even more violent transformations of political revolution. But the new conquerors always left the land to the old peasant because he alone could till it in that age of sparse population, and they continued the revenue collection in the hands of the old hereditary middleman, because they alone knew the details of the locality and could ensure some payment from the land to a distant sovereign who would have found it impossible to collect his dues from each petty tiller of the soil directly. The offices in connection with land, therefore, tended to become hereditary and the contractor of revenue blossomed in time into a landowner with a permanent family claim to a portion of the yield of his village or district. Attachment to one’s ancestral land was the strongest passion in the age of little trade and small scale industries. I know of a Brahman family which migrated from the Ratnagiri district to Ahmadabad six generations ago and no longer owned an inch of land in their ancient home nor keep any business connection with it, and yet they have carefully preserved for two centuries the old title-deeds of their long-abandoned lands.

And in that age land rights were unsettled and perplexing by reason of the variety and complication of the personal claims to one and the same tract. Illustrations of this state of things can be found almost everywhere in the Deccan; I give the case of Savant-vadi as readily available in print. In this small region there was in the 16th century a desai (or zamindar) of the Prabhu caste at Kudal for collecting the revenue on behalf of the Bijapur Sultan, with a dalvi or captain of the Rajput caste under him to lead his troops. The dalvi rebelled against his master the desai and sought the help of a neighbouring savant or chief of the Maratha caste. At first the desai suppressed the rebel with the support of his sovereign. But in the third generation an able savant rose to power, secured the desai-ship of Banda from Adil Shah, and after extirpating most of the Prabhu desais annexed the Kudal pargana. But some members of the dispossessed family escaped and revived their claim of land. Next, Shivaji stepped in to oust the savant! Further complications were introduced by two branches of the same family (often two brothers) fighting for the same estate and transmitting their disputes to their sons and grandsons.

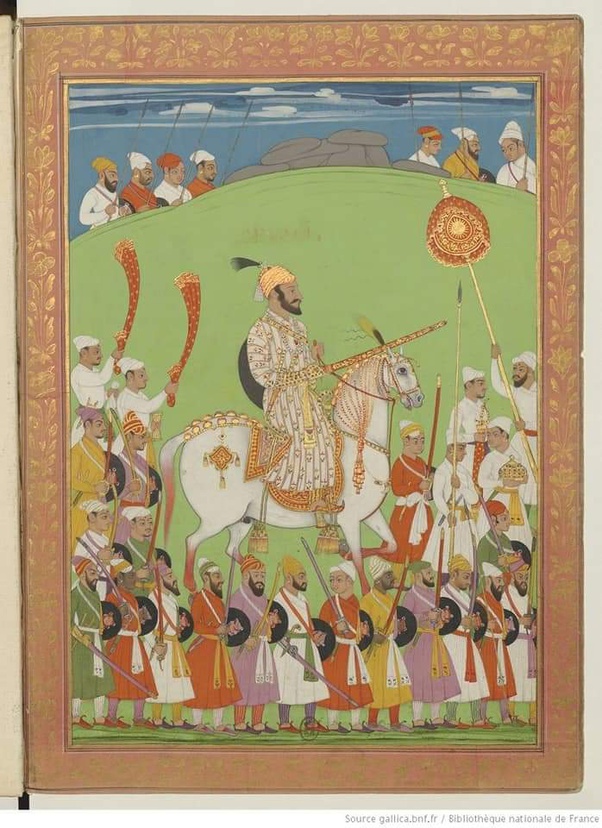

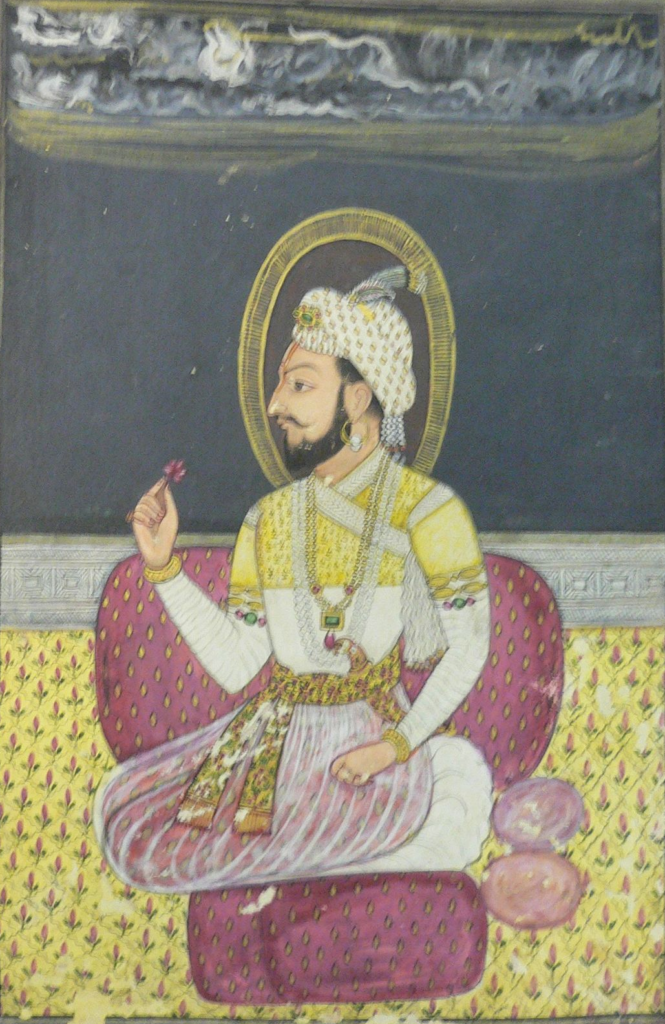

Shivaji by Mir Mohammad (Courtesy: National Library of France)

Into this world if bewildering confusion of land-rights and revenue offices—where nothing was generally known for certain or acknowledged as a clear final settlement—Shivaji (like all other conquerors) burst as a new dissolving force. He had to give his own decision on these claims. All who lost their suits before him, all who were displaced in office by his nominees, immediately turned against him and tried to make their claims good by joining his enemies and opposing his Government. There was no national feeling, no spirit of accepting the law of the land even when honestly administered.

To every one in that age his own fief (watan) was the only reality, the only object of a man’s lifelong endeavour, his highest reward on earth, while Fatherland (patria), if thought of at all, was felt to be an abstract idea, a nonentity. Watan could yield honour, power and the pleasures of life, while patria was a mere word, a figment of the imagination.

To every one in that age his own fief (watan) was the only reality, the only object of a man’s lifelong endeavour, his highest reward on earth, while Fatherland (patria), if thought of at all, was felt to be an abstract idea, a nonentity. Watan could yield honour, power and the pleasures of life, while patria was a mere word, a figment of the imagination.

A further hindrance to the growth of patriotism was the infinitely minute sub-division of society, which made the formation of one nation, or a compact body of men moved by the community of life, thought and interests, impossible, and even inconceivable. Apart from the impassable chasm between the Hindus and the Muslims living on the same soil and under the same rulers, the Hindus themselves were split up into innumerable mutually warring (or, at best, contemptuously detached and indifferent) fragments. Not only did one caste despise and persecute another, but even among the members of the same caste there were distinctions as sharp as those marking off the Muhammadan from the Hindu or the Shudra from the Brahman. Certain families claimed to be of nobler blood (kulin) than all others of the same caste and locality, and depressed and insulted the latter in society. The highest aim of a Hindu in that age—as even in our times—was to elevate his own family (and often also his own sub-division of a caste) in the social scale by lavish bounty to the Brahmans and the caste elders, by hypergamy, or by a nearer approach to the practices of the highest or “twice-born” castes. But the dominant families (or castes) tried to keep the newer or lower ones down at their former level of degradation by turning all the engines of social persecution against them. They took away from such daring aspirants and disturbers of the primeval stereotyped usage and custom, not only the benefit of the clergy but also all the amenities of social life and the services of the public servants of the village. This boycott or outcasting (gramanya) was a more terrifying penalty than death itself.

It was only human nature if the noblest members of the despised families (or castes) resented this injustice and tyranny of society and, in the bitterness of public humiliation, sought to be avenged on the prosecuting church and State by going over to the enemies of their country and faith. Such action, on the part of the oppressors and the oppressed alike, is impossible where a true sense of nationality has taken root. Patriotism could not grow on the Indian soil (except among compact clans of blood-kindred like the Rajputs). The State, as an impersonal, continuous being—higher and more durable than our individual selves—could not be conceived of by the rulers of Hindu India whose sole care was for the benefit of self and not for the good of the community as a whole.

As an acute English observer wrote in 1803: “Every Maratha prince, and every jagirdar or military chief in the [Maratha] empire, has a khazana or collection of treasure, consisting of specie and jewels, which is lodged in a secret depository within the walls of a strong fortress, often erected for the purpose, on one of the most inaccessible mountains in his dominions. This private treasure is the first and never-ceasing object of his ambition to increase … No want of money for supporting a war, even in defence of his own territory, ever induces a Maratha chief to supply the deficiency from his private treasury; the loss of which would be to him a much more grievous calamity than the subjugation of his country.”

(Asiatic Annual Register for 1803, p. 4. A recent example was that of Daulat Rao Sindhia in 1809, as described by Capt. Broughton: “While Sindhia is daily submitting to these and similar insults, from his unpaid soldiery, he possessed a privy purse of 50 lakhs; which no distress either of himself or his troops is sufficiently powerful to induce him to violate.” Letters from a Mahratta Camp, Const. Ed., p. 160.)

The dominant families (or castes) tried to keep the newer or lower ones down at their former level of degradation by turning all the engines of social persecution against them. They took away from such daring aspirants and disturbers of the primeval stereotyped usage and custom, not only the benefit of the clergy but also all the amenities of social life and the services of the public servants of the village. This boycott or outcasting (gramanya) was a more terrifying penalty than death itself.

It was only human nature if the noblest members of the despised families (or castes) resented this injustice and tyranny of society and, in the bitterness of public humiliation, sought to be avenged on the prosecuting church and State by going over to the enemies of their country and faith.

Such were the men among whom Shivaji tried to build up his edifice of an independent national State, the men whom he had to employ as his instruments, the men to whom he had to leave his uncompleted task. The leaders were actuated by an insane pride of birth, an all-devouring jealousy about precedence, an ambition that blinded them to all consequences, an incapacity for self-subordination to law and corporate loyalty that marks the lesser breeds, a lack of political vision and of practical realism. As for the masses, they were human sheep, worthy to be led by such shepherds; their horizon was bounded by the hard conditions of their daily toil, with a simple emotional faith as their only solace.

In such conditions not even a superman can create a nation and leave an enduring State behind him. Shivaji with his transcendent genius could have barely laid their true foundations if a long reign of internal peace had been granted to him and he had been followed by a line of worthy successors. But he lived for less than six years after his coronation, and his kingdom perished with his sons.

The Maratha rulers neglected the economic development of the State. Some of them did, no doubt, try to save the peasantry from illegal exactions, and to this extent they promoted agriculture. But commerce was subjected to frequent harassment by local officers, and the traders could never be certain of freedom of movement and security of their rights on mere payment of the legal rate of duty. The internal resources of a small province with no industry, little trade, a sterile soil, and an agriculture dependent upon scanty and precarious rainfall— could not possibly support the large army that Shivaji kept or the imperial position and world-dominion to which the Peshwas aspired.

Gopal Krishna Gokhale

The necessary expenses of the State could be met, and all the parts of the body-politic could be held together only by a constant flow of money from outside its own borders, i.e., by a regular succession of raids. As the late Mr. G. K. Gokhale laughingly told me when describing the hardships of the present rigid land assessment in the Bombay Presidency, “You see, the land revenue did not matter much under Maratha rule. In those old days, when the crop failed our people used to sally forth with their horses and spears and bring back enough booty to feed them for the next two or three years. Now they have to starve on their own lands.”

Thus, by the character of his State, the Maratha’s hands were turned against everybody and everybody’s hands were turned against him. It is the Nemesis of a Krieg-staat (a Government that lives and grows only by wars of aggression) to move in a vicious circle. It must wage war periodically if it is to get its food; but war, when waged as a normal method of supply, destroys industry and wealth in the invading and invaded countries alike, and ultimately defeats the very end of such wars. Peace is death to a Krieg-staat; but peace is the very life-breath of wealth. A State founded on war, therefore, kills the goose that lays the golden eggs. To take an illustration, Shivaji’s repeated plunder of Surat scared away trade and wealth from that city, and his second raid (in 1670) brought him much less booty than his first, and a few years later the constant dread of Maratha incursion entirely impoverished Surat and effectually dried up this source of supply. Thus, from the economic point of view, the Maratha State had no stable basis, no normal means of growth within itself.

It is the Nemesis of a Krieg-staat (a Government that lives and grows only by wars of aggression) to move in a vicious circle. It must wage war periodically if it is to get its food; but war, when waged as a normal method of supply, destroys industry and wealth in the invading and invaded countries alike, and ultimately defeats the very end of such wars. Peace is death to a Krieg-staat; but peace is the very life-breath of wealth. A State founded on war, therefore, kills the goose that lays the golden eggs.

Lastly, the Maratha leaders trusted too much to finesse. They did not realise that without a certain amount of fidelity to promises no society can hold together. Stratagem and falsehood may have been necessary at the birth of their State, but it was continued during the maturity of their power. No one could rely on the promise of a Maratha minister or the assurance of a Maratha general. Witness the long and finally fruitless negotiations of the English merchants with Shivaji for compensation for the looting of their Rajapur factory. The Maratha Government could not always be relied on to abide by their treaty obligations.

Yashwantrao Holkar and Daulat Rao Sindhia

Shivaji, and to a lesser extent Baji Rao I, preserved an admirable balance between war and diplomacy. But the latter-day Marathas lost this practical ability. They trusted too much to diplomatic trickery, as if empire were a pacific game of chess. Military efficiency was neglected, war at the right moment and in the right fashion was avoided, or, worse still, their forces were frittered away in unseasonable campaigns and raids conducted as a matter of routine, and the highest political wisdom was believed to consist in raj-karan or diplomatic intrigue. Thus, while the Maratha spider was weaving his endless cobweb of hollow alliances and diplomatic counter-plots, the mailed fist of Wellesley was thrust into his laboured but flimsy tissue of state-craft, and by a few swift and judicious strokes his defence and screen was torn away and his power left naked and helpless. In rapid succession the Nizam was disarmed, Tipu was crushed, and the Peshwa was enslaved. While Sindhia and Holkar were dreaming the dream of the overlordship of all India, they suddenly awoke to find that even their local independence was gone. The man of action, the soldier-statesman, always triumphs over the mere scheming Machiavel. Punic perfidy never succeeds in the long run.

Shivaji’s private life was marked by a high standard of morality. He was a devoted son, a loving father and an attentive husband, though he did not rise above the ideas and usage of his age, which allowed a plurality of wives and the keeping of concubines even among the priestly caste, not to speak of warriors and kings. Intensely religious from his very boyhood, by instinct and training alike, he remained throughout life abstemious, free from vice, devoted to holy men, and passionately fond of hearing scripture readings and sacred stories and songs. But religion remained with him an ever fresh fountain of right conduct and generosity; it did not obsess his mind nor harden him into a bigot. The sincerity of his faith is proved by his impartial respect for the holy men of all sects (Muslim as much as Hindu) and toleration of all creeds. His chivalry to women and strict enforcement of morality in his camp was a wonder in that age and has extorted the admiration of hostile critics like Khafi Khan.

He had the born leader’s personal magnetism and threw a spell over all who knew him, drawing the best elements of the country to his side and winning the most devoted service from his officers, while his dazzling victories and ever ready smile made him the idol of his soldiery. His royal gift of judging character was one of the main causes of his success, as his selection of generals and governors, diplomatists and secretaries was never at fault, and his administration was a great improvement on the past.

His army organisation was a model of efficiency; everything was provided for beforehand and kept in its proper place under a proper caretaker; an excellent spy system supplied him in advance with the most minute information about the theatre of his intended campaign; divisions of his army were combined or dispersed at will over long distances without failure; the enemy’s pursuit or obstruction was successfully met and yet the booty was rapidly and safely conveyed home without any loss. His inborn military genius is proved by his instinctively adopting that system of warfare which was most suited to the racial character of his soldiers, the nature of the country, the weapons of the age, and the internal condition of his enemies. His light cavalry, stiffened with swift-footed infantry, was irresistible in the age of Aurangzib. More than a century after his death, his blind imitator Daulat Rao Sindhia continued the same tactics when the English had galloper guns for field action and most of the Deccan towns were walled round and provided with defensive artillery, and he therefore failed ignominiously.

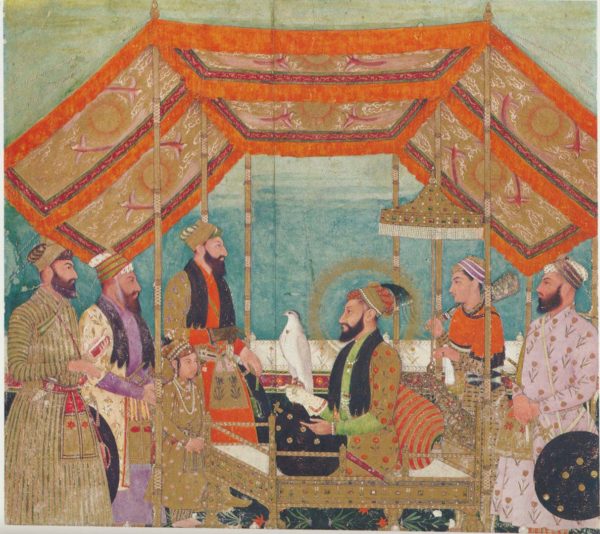

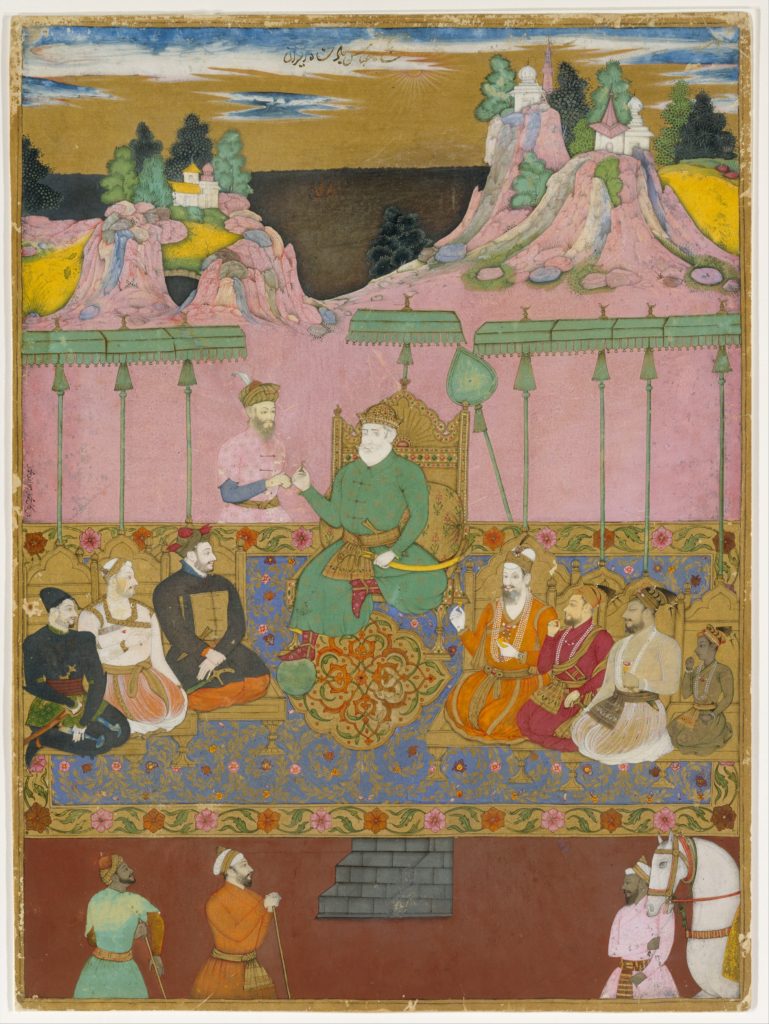

Aurangzeb holds court

Intensely religious from his very boyhood, by instinct and training alike, he remained throughout life abstemious, free from vice, devoted to holy men, and passionately fond of hearing scripture readings and sacred stories and songs. But religion remained with him an ever fresh fountain of right conduct and generosity; it did not obsess his mind nor harden him into a bigot. The sincerity of his faith is proved by his impartial respect for the holy men of all sects (Muslim as much as Hindu) and toleration of all creeds.

The greatness of Shivaji’s genius can be fully realised not from the extent of the kingdom he won for himself, nor from the value of the hoarded treasure he left behind him, but from a survey of the conditions amidst which he rose to sovereignty.

He was truly an original explorer, the maker of a new road in mediaeval Indian history, with no example or guide before him. When he chose to declare his independence, the Mughal empire seemed to be at the height of its glory. Every local chief who had, anywhere in India, revolted against it had been crushed. For a small jagirdar’s son to defy its power, appeared as an act of madness, a courting of sure ruin. Shivaji, however, chose this path, and he succeeded.

His success can be explained only by an analysis of his political genius. First and foremost he possessed that unfailing sense of reality in politics, that recognition of the exact possibilities of his time (tact des choses possibles) which Cavour defined as the essence of statesmanship. His daring was tempered and guided by an instinctive perception of how far his actual resources could carry him, how long a certain line of action or policy was to be followed, and where he must stop. For the lack of this political insight his rash son Shambhuji came to a miserable end and undid the work of Shivaji’s life.

Shambhuji. Late 17th Century

Shivaji possessed the true master’s gift of judging character at sight and choosing the fittest instruments for his work. This is proved by the successful execution of his agents in his absence. Many of the distant expeditions of his reign were conducted not by himself but by his generals, who almost always carried out his orders according to plan. This is a novel feat in an Asiatic monarchy, where everything depends on the master’s presence. It was the training gained in Shivaji’s service, aided by the Maratha national character for personal independence and initiative, that enabled the disorganized Maratha people to stand up against the resources of the mighty Aurangzib for eighteen years after the murder of Shambhuji and ultimately to defeat him, even though they had no king or capital to form the centre of the national defence.

His reign brought peace and order to his country, assured the protection of women’s honour and the religion of all sects without distinction, extended the royal patronage to the truly pious men of all creeds (Muslims no less than Hindus), and presented equal opportunities to all his subjects by opening the public service to talent irrespective of caste or creed. This was the ideal policy for a State with a composite population like India.

(He was himself a Hindu, sincere in belief and orthodox in practice, and yet he had a number of Muhammadan officers in the highest positions, such as Munshi Haidar (who became Chief Justice of the Mughal empire on entering Aurangzib’s service), Siddi Sambal, Siddi Misri, and Daulat Khan (admirals), besides commanders like Siddi Halal and Nur Khan. (Dil. i. 100.) He gave legal recognition to the Muslim qazis in his dominions.)

His gifts were peace and a wise internal administration. The stability of these good conditions was the only thing necessary for giving permanence to Shivaji’s work and ensuring national consolidation and growth. But that stability was denied to his political creation. Only his example and name remained to inspire the best minds of succeeding generations with ideals of life and government, not unmixed with vain regrets.

Shivaji possessed the true master’s gift of judging character at sight and choosing the fittest instruments for his work. This is proved by the successful execution of his agents in his absence. Many of the distant expeditions of his reign were conducted not by himself but by his generals, who almost always carried out his orders according to plan. This is a novel feat in an Asiatic monarchy, where everything depends on the master’s presence.

Did Shivaji merely found a Krieg-staat? Was he merely an entrepreneur of rapine, a Hindu edition of Alauddin Khilji or Timur?

I think it would not be fair to take this view. For one thing, he never had peace to work out his political ideal. The whole of his short life was one struggle with enemies, a period of preparation and not of fruition. All his attention was necessarily devoted to meeting daily dangers with daily expedients and he had not the chance of peacefully building up a well-planned political edifice.

In the vast Gangetic valley and the wide Desh country rolling eastwards through the Deccan, Nature has fixed no boundary to States. Here a kingdom’s size changes with daily changes in its strength as compared with their neighbours’. There can be no stable equilibrium among them for more than a generation. Each has to push the others as much for self-defence as for aggression. Each must be armed and ready to invade the others, if it does not wish to be invaded and absorbed by them. Where friction with neighbours is the normal state of things, a huge armed force, sleepless vigilance, and readiness to strike the first blow are the necessary conditions of the very existence of a kingdom. The evil could be remedied only by the establishment of a universal empire throughout the country from sea to sea.

Shivaji could not for a moment be sure of the Delhi Government’s pacific disposition or fidelity to treaty. The past history of the Mughal expansion into the Deccan since the days of Akbar, was a warning to him. The imperial policy of annexing the whole of South India was as unmistakable to Shiva as to Adil Shah or Qutb Shah. Its completion was only a question of time, and every Deccani Power was bound to wage eternal warfare with the Mughals if it wished to exist. Hence Shivaji lost no chance of robbing Mughal territory in the Deccan.

Sikandar Adil Shah

With Bijapur his relations were somewhat different. He could raise his head or expand his dominion only at the expense of Bijapur. Rebellion against his liege-lord was the necessary condition of his being. But when, about 1662, an understanding was effected between him and the Adil-Shahi ministers, he gave up molesting the heart of the Bijapur kingdom. With the Bijapuri barons whose fiefs lay close to his dominions, he had, however, to wage war till he had wrested Kolhapur, North Kanara and South Konkan from their hands. In the Kamatak division, viz., the Dharwar and Belgaum districts, this contest was still undecided when he died. With the provinces that lay across the path of his natural expansion he could not be at peace, though he did not wish to challenge the central Government of Bijapur. This attitude was changed by the death of Ali II. in 1672, the accession of the boy Sikandar Adil Shah, the faction-fights between rival nobles at the capital, and the visible dissolution of that Government. But Shivaji helped Bijapur greatly during the Mughal invasions of 1679.

Ali Aadil Shah II of Bijapur

Shivaji’s real greatness lay in his character and practical ability, rather than in originality of conception or length of political vision. Unfailing insight into the character of others, efficiency of arrangements, and instinctive perception of what was practicable and most profitable under the circumstances— these were the causes of his success in life. To these must be added his personal morality and loftiness of aim, which drew to his side the best minds of his community, while his universal toleration and insistence on equal justice gave contentment to all classes subject to his rule. He strenuously maintained order and enforced moral laws throughout his own dominions, and the people were happier under him than anywhere else.

His splendid success fired the imagination of his contemporaries, and his name became a spell calling the Maratha race to a new life. His kingdom was lost within nine years of his death. But the imperishable achievement of his life was the raising of the Marathas into an independent self-reliant people, conscious of their oneness and high destiny, and his most precious legacy was the spirit that he breathed into his race.

The mutual conflict and internal weakness of the three Muslim Powers of the Deccan were, no doubt, contributory causes of the rise of Shivaji. But his success sprang from a higher source than the incompetence of his enemies. I regard him as the last great constructive genius and nation-builder that the Hindu race has produced. His system was his own creation and, unlike Ranjit Singh, he took no foreign aid in his administration. His army was drilled and commanded by his own people and not by Frenchmen. What he built lasted long; his institutions were looked up to with admiration and emulation even a century later in the palmy days of the Peshwas’ rule.

Shivaji was illiterate; he learnt nothing by reading. He built up his kingdom and Government before visiting any royal Court, civilised city, or organised camp. He received no help or counsel from any experienced minister or general. But his native genius, alone and unaided, enabled him to found a compact kingdom, an invincible army, and a grand and beneficent system of administration.

Before his rise, the Maratha race was scattered like atoms through many Deccani kingdoms. He welded them into a mighty nation. And he achieved this in the teeth of the opposition of four great Powers like the Mughal empire, Bijapur, Portuguese India, and the Abyssinians of Janjira. No other mediaeval Hindu has shown such capacity.

Before he came, the Marathas were mere hirelings, mere servants of aliens. They served the State, but had no lot or part in its management; they shed their lifeblood in the army, but were denied any share in the conduct of war or peace. They were always subordinates, never leaders.

Shivaji was the first to challenge Bijapur and Delhi and thus teach his countrymen that it was possible for them to be independent leaders in war. Then, he founded a State and taught his people that they were capable of administering a kingdom in all its departments. He has proved by his example that the Hindu race can build a nation, found a State, defeat enemies; they can conduct their own defence; they can protect and promote literature and art, commerce and industry; they can maintain navies and ocean-trading fleets of their own, and conduct naval battles on equal terms with foreigners. He taught the modern Hindus to rise to the full stature of their growth.

The mutual conflict and internal weakness of the three Muslim Powers of the Deccan were, no doubt, contributory causes of the rise of Shivaji. But his success sprang from a higher source than the incompetence of his enemies. I regard him as the last great constructive genius and nation-builder that the Hindu race has produced. His system was his own creation and, unlike Ranjit Singh, he took no foreign aid in his administration. His army was drilled and commanded by his own people and not by Frenchmen. What he built lasted long; his institutions were looked up to with admiration and emulation even a century later in the palmy days of the Peshwas’ rule.

Emperor Jahangir

He has proved that the Hindu race can still produce not only jamadars (non-commissioned officers) and chitnises (clerks), but also rulers of men, and even a king of kings (Chhatrapati.) The Emperor Jahangir cut the Akshay Bat tree of Allahabad down to its roots and hammered a red-hot iron cauldron on to its stump. He flattered himself that he had killed it. But lo! Within a year the tree began to grow again and pushed the heavy obstruction to its growth aside!

Shivaji has shown that the tree of Hinduism is not really dead, that it can rise from beneath the seemingly crushing load of centuries of political bondage, exclusion from the administration, and legal repression; it can put forth new leaves and branches; it can again lift up its head to the skies.

For the purposes of easier reading, this excerpt has been carried without citations present in the original. You can buy Shivaji and His Times here.

Jadunath Sarkar (1870-1958) was one of the foremost historians of his time. He was a Vice-Chancellor of Calcutta University. His many books include India of Aurangzib, a five-volume History of Aurangzib, a four-volume Fall of the Mughal Empire, Chaitanya: His Pilgrimages and Teachings, The History of Bengal, Economics of British India, Military History of India and Shivaji and His Times. Besides his original works, Sarkar also translated into English and Bengali many Persian and Marathi documents and was a considerable force behind the work of Indian Historical Records Commission and the National Archives of India. You can read more about him here, here and here.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply