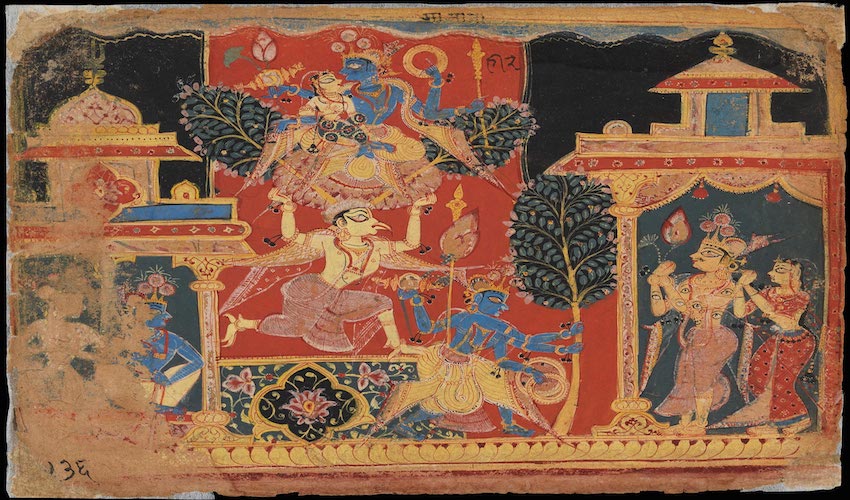

Krishna Uprooting the Parijata Tree from a Bhagavata Purana manuscript, 1525–50, made in Delhi region or Rajasthan, India. Opaque watercolor and ink on paper, 7 1/4 × 9 1/2 in. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, from the Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck Collection, Museum Associates Purchase, M.72.1.26. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

‘Religion’, a chapter from Irfan Habib’s book, ‘Medieval India: A Study of Civilisation’ has been recommended by Shireen Moosvi considering it to be, in her words, “topical for the present”.

For a long time, colonial historiography has dominated our understanding of religion in India, especially the all-encompassing term ‘Hinduism’ as opposed to Islam. “The colonial view of religion in India”, writes Romila Thapar, “differentiated between Islam which they were familiar with from the Crusades and as the religion of west Asia, and the Hindus that were more diverse and less familiar. So the sects of the Hindus were brought under a single umbrella and this was labeled Hinduism.”

But, to ignore the social and cultural contexts of religion in its many layers of history, while looking at the present day sanctity of any religious institution in India, is to ignore its evolutionary process.

Focusing on the history of religion during the Mughal period in India, Irfan Habib writes, “on a first view the continuing coexistence of Hinduism and Islam seems to be the most significant aspect of religious life in Mughal India. This very observation, however, tends to obscure the fact that Hinduism and Islam were not religions in the same sense… In other words, while ‘Hindu’ was the appellation of an Indian who was not a Muslim, it was yet difficult to speak of Hinduism as a single body of doctrine in the same sense as one could speak of Islam or, indeed, of the Semitic religions in general.”

That within the umbrella term ‘Hinduism’, we find countless faiths and forms of worship, rituals, mythologies, arts, and ethics, is a fact that is hardly hidden.

However, “having developed in mutual interaction and expressed in a large part in the same language (Sanskrit),” observes Habib, “the different sects of Hinduism yet shared the same idiom and even the same or similar deities.”

In the chapter reproduced below, Habib goes on to highlight the varied forms of religious identities that existed during the medieval period in India. While Brahmanical texts continued their “assertion” during the Mughal period, according to Habib, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were “essentially the centuries of Vaishnavism.” He goes on to exemplify this by citing:

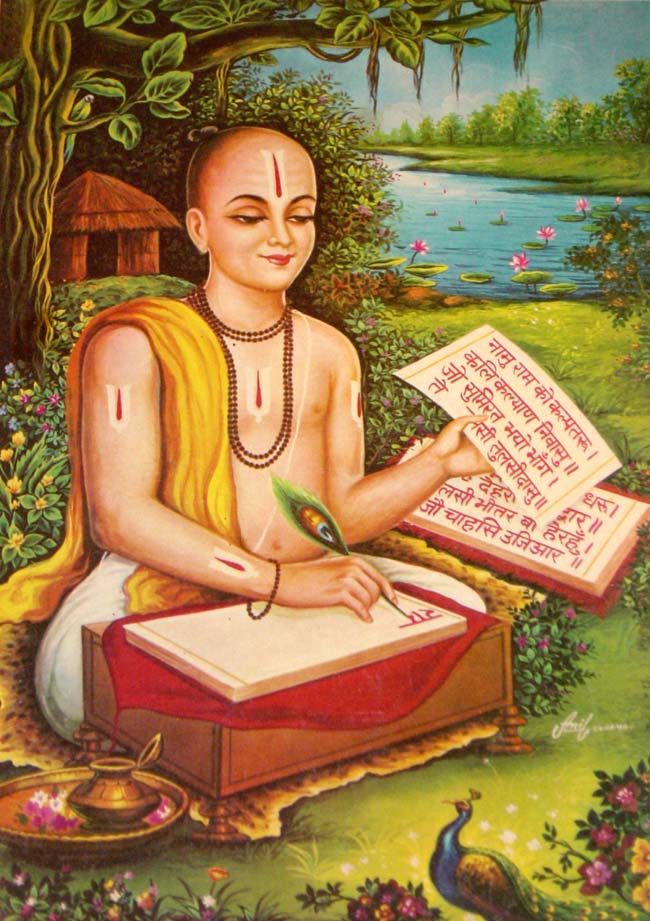

1) Tulsidas’ Ramcharitmanas, written in the Awadhi dialect, that gave a popular garb to the original Ramayana;

2) The cult of Krishna and his female lover Radhā, initiated by Chaitanya, a Brahman priest of Navadvip (Bengal);

3) A Vaishnava sect founded by Shankaradeva in Assam, who avoided image-worship and emphasized an Absolute, Personal God;

4) Vallabhacharya and his son Vitthalnath, who propagated a religion of grace (pushtimarga);

5) Surdās, owing allegiance to this sect, wrote Sur-saravali in the local language, Braj;

6) Eknath, a Brahman, expounded the principle of bhakti and allowed all castes as well as women to assemble and praise the Lord and join in the ecstasy of devotional chants (kirtan);

7) Tukārām, a Shūdra peasant, while addressing himself to Vithoba, the Lord of Pandhari, his God (Vitthal) tends to be closer to the Ram of the monotheist Kabir than to the Krishna of Chaintaya;

8) Rāmdās, who combined the propagation of the worship of Rama as God with the upholding of the dharma (“the Maharashtra Dharma”), i.e. maintenance of “the holiness of the Brahmans and deities”.

And if these different strands of Bhakti movement are not enough to illustrate the varied forms of worship within Hinduism, Habib also goes on to emphasise on the different religions that co-existed during this period, namely Jainism, Sikhism and Christianity, along with, of course, the monotheistic movement by Kabir. For a glimpse into the ways in which these sects provided diversity of thoughts during medieval times, we urge you to read the chapter reproduced below.

What forms the crux of the major debate in the history of religion during mughal period, however, is the influence of Islam. “The continued co-existence [of Islam] with Hinduism”, according to Habib, “brought into focus, in course of time, the problem of assessing non-Muslim faiths and beliefs.” It was during Akbar’s reign that these debates reached their zenith. While initially, Akbar himself began his spiritual journey from within the confines of traditional Islam, he soon became involved in religious discussions with representatives of other sects (Brahman scholars, other Hindu recluses, Jains, Parsis and Christians), at a special building, the ‘ibadatkhana’ (house of prayer), at Fatehpur Sikri.

“These discussions convinced Akbar that no single interpretation of Islam was correct or even forthcoming, and further that no single religion could be true, but that all drew, but only in part, upon the same Truth. It was for him, as the chosen man of God, to assist in the realization of a consciousness of Absolute Peace (Sulh-i Kul) in order to prevent idle strife between the votaries of different religions and factions.” — Irfan Habib

What Habib also states is that it was “more likely that Akbar’s own views took direction, because a policy of tolerance was politically very useful and had, indeed, been adopted much before his philosophical views took the form they did in the last twenty- five years of his life.”

Nevertheless, the culmination of Islam’s recognition of Hinduism reached in Dara Shukoh, the eldest son of Emperor Shähjahān. He could never formally ascend the throne, thanks to the war of succession among the four sons of Shah Jahan and the eventual success of Aurangzeb. Aurangzeb on his part, despite his patronage of the descendants of Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi, could not accept the latter’s extreme spiritual claims, and generally supported traditional and legal Islam.

Read the chapter ahead for further insights into the religious politics during Mughal India.

Shireen Moosvi is an acclaimed historian. She retired as a Professor of History at the Centre of Advanced Study in History, Aligarh Muslim University. She started her career in Aligarh Muslim University as a teacher but ended up being the Chairman of the Department of History, Dean of Faculty of Social Sciences and also contributed as a Director of Centre for Women’s Studies, transforming the centre to an educational hub for gender studies renowned across the country. Apart from publishing widely on Mughal India, she has published numerous papers on colonial economic history and labour conditions. She is a prominent figure of the Indian History Congress. She has also served as a Member of the Council of Indian Council of Historical Research and Member Central Advisory Board of Archaeology.

Moosvi has been a recipient of many fellowships and awards. She held a Senior Fulbright Fellowship, USA, 1983-84. She was awarded Residency at Bellagio Centre, Milan, Italy by the Rockefeller Foundation, 1990- 91. She has also received National Career Award, University Grants Commission, 1986-89. She was a visiting fellow in the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla, June-July, 1994 and in M.S. University, Baroda, March-April, 1984.

She has authored The Economy of the Mughal Empire, c. 1595: A Statistical Study (1987) and People, Taxation and Trade in Mughal India (2010). She has co-edited books like Facets of the Great Rebellion, 1857 (2009) and Capitalism, Colonialism and Globalization (2011). She has also published Episodes in the Life of Akbar (1994).

On a first view the continuing coexistence of Hinduism and Islam seems to be the most significant aspect of religious life in Mughal India. This very observation, however, tends to obscure the fact that Hinduism and Islam were not religions in the same sense. In his remarkable work on the religions of the world, the anonymous author of the Dabistan (written, c.1653), notes that “among the Hindus there are numerous religions, and countless faiths and customs.” In other words, while “Hindu” was the appellation of an Indian who was not a Muslim, it was yet difficult to speak of Hinduism as a single body of doctrine in the same sense as one could speak of Islam or, indeed, of the Semitic religions in general. It was equally true, however, that, having developed in mutual interaction and expressed in a large part in the same language (Sanskrit), the different sects of Hinduism yet shared the same idiom and even the same or similar deities. Written sixty years earlier, Abu’l Fazl’s A’in-i Akbarī (1595) precedes the Dabistan in giving us a very detailed and comprehensive description of Hindu beliefs.

On a first view the continuing coexistence of Hinduism and Islam seems to be the most significant aspect of religious life in Mughal India. This very observation, however, tends to obscure the fact that Hinduism and Islam were not religions in the same sense.

The Mughal period witnessed a continuing assertion in Brahmanical texts of almost all the basic elements of Higher or Orthodox Hinduism that the Ain-i Akbarī and the Dabistan outline. There was a notable exposition of Mimamsa in Narayana Bhatta’s Manameyodaya (c.1600). The school upheld the automatic functioning of the system of transmigration of souls in life-cycles, the station in each life being the result of deeds (karma) in the previous cycles. The author of the Dabistan makes the interesting observation that the “common belief” among the Hindus was that though there was one Creator, the created beings in their lives remained bound by the influence of their own deeds. The emphasis on karma was now the key to dharma, or prescribed conduct of the smriti schools. In this field the traditional doctrine continued to be reasserted in digests, commentaries and elaborations. Vachaspati (c.1510) wrote the Vivädachintamani in Mithila (Bihar). In Bengal, c.1567, Raghunandana of Navadvip wrote his twenty-eight treatises, the Smrititattva, which became an authority on ritual and inheritance. The Nirnayasindhu of Kamalakara Bhatta (1612), which cites Raghunandana as an authority, in turn, obtained legal and religious authority in Maharashtra. An encyclopedic legal work, the Viramitrodaya was compiled by Mitra Mishra under the patronage of Bir Singh, a leading noble of Emperor Jahangir (1605-27).

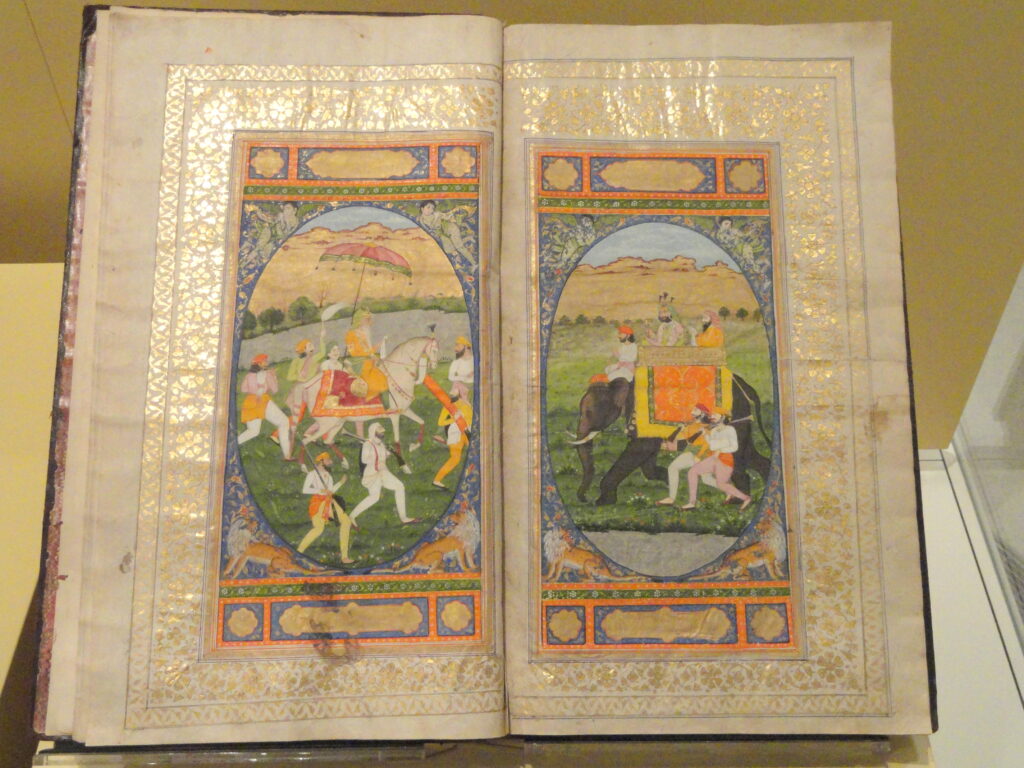

Ain-i-Akbari

![]() These works did not generally make any noteworthy deviations from positions adopted in respect of the supremacy of the Brahmans and the caste-rules as defined by the earlier Smritis. If anything, they repeated and elaborated the restrictions imposed on the lower castes and women. Raghunandana went so far as to declare that the Brahmanas were the only ‘twice-born’ left, since, according to him, the Kshatriyas and Vaishyas had by now fallen among the ranks of the Shudras!

These works did not generally make any noteworthy deviations from positions adopted in respect of the supremacy of the Brahmans and the caste-rules as defined by the earlier Smritis. If anything, they repeated and elaborated the restrictions imposed on the lower castes and women. Raghunandana went so far as to declare that the Brahmanas were the only ‘twice-born’ left, since, according to him, the Kshatriyas and Vaishyas had by now fallen among the ranks of the Shudras!

In Vedanta, the Shankaracharya tradition was influential enough to produce a number of texts. It is clear from various statements in the Dabistan that the pantheism of Shankaracharya had by the mid-seventeenth century permeated a large number of sects and schools. Sadananda in his Vedantasära (c.1500) exhibits an admixture of Samkhya principles. On the other hand, Vijñänabhikshu (c.1650), author of the Samkhyasara, admitted the truth of Vedanta, professing to see the Samkhya Duality as no more than one aspect of the Truth. A similar reconciliation of Vedanta with Shaivite beliefs seems to have been developed by Appayya Dikshita (1520-92) of Vellore, a prolific writer on many subjects. A Shaivite theologian of the south of a later phase was Shivananar (fl.1785).

Commensurate with the widespread currency of Tantrik beliefs and practices reported by the Dabistan, Tantrik literature received considerable additions during this period. Mahidhara of Varanasi wrote the Mantra-mahodadhi in 1589. In Bengal Pürnända (fl. 1571) wrote treatises on philosophy and magical rites; in the next century Krishnänanda Agamavägisha of Navadvip wrote the authoritative textbook, Tantrasara.

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were, however, essentially the centuries of Vaishnavism. In the Northern India the Rama cult had its greatest propagator in Tulsidas who in his Ramcharitmanas, written in the Awadhi dialect, gave a popular garb to the original Rāmāyaṇa. Tulsidas was a firm believer in the dharmashastra, and he regarded the popular monotheistic cults, with their Shudra leaders, as signs of the degradation of the present age (kalijug). Yet this was not the main message of his work. In his fervent verses of devotion and portrayal of a just Rama, the incarnated deity became God, in full control of destiny.

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were, however, essentially the centuries of Vaishnavism.

The expression was still more emotional when the object of bhakti (devotion) was Krishna, another incarnation of Vishnu. Chaitanya (1485-1533), a Brahman priest of Navadvip (Bengal) initiated a cult of Krishna and his female lover Radhā, in which the devotee, repeating the deity’s name, pictured himself as a companion of Krishna at Vrindaban, re-enacting in his mind His “manifest” sports (lilas). These mental visions were the means of a communion with the Lord, in which Krishna too relished the devotee’s love. While Chaitanya had his followers mainly in Bengal, he left very active successors, the gosvamins, at Vrindaban near Mathura, who in a series of Sanskrit works gave a philosophical basis to the cult and outlined its ritual. To his followers Chaitanya himself appeared as a joint incarnation of Krishna and Radha. Though in their life as householders, the devotees followed the caste ritual, the right of worship was not denied to the lower classes; and the Sahajiya sect (eighteenth century) rejected life as ordained by the smritis and introduced shaktik and tantrik practices. In Assam, a Vaishnava sect paralleling that of Chaitanya was founded by a junior contemporary of his, Shankaradeva (d.1568), who however avoided image-worship and emphasized an Absolute, Personal God, to Whom all devotion directed in the form of love for Krishna.

Vallabhacharya (d.1531) and his son Vitthalnath (d.1576) propagated a religion of grace (pushtimarga); and Surdās, owing allegiance to this sect, wrote Sur-saravali (1545) in the local language, Braj, in which the sports of Krishna with Radhā and others were described as manifestations of the Lord’s supreme powers. The sect obtained some popularity in Gujarat and Rajasthan; there developed an excessive adoration of the descendants of Vallabhacharya (now regarded as an incarnation of Krishna), who obtained the designation ‘Mahārāj’, and relied on the following of a rich mercantile community. The Rädha vallabhis owed their foundation to Hita Harivamsha (d.1553) and assigned to Radha the more crucial position in the Duality of Divinity.

Tulsidas composing his famous Avadhi Ramcharitmanas (Wikipedia Commons)

The Vaishnavite movement in Maharashtra contained both Unitarian and conservative elements. Eknath (d.1599), a Brahman, expounded the principle of bhakti and allowed all castes as well as women to assemble and praise the Lord and join in the ecstasy of devotional chants (kirtan). He also tended to discount mere ritual. Tukārām, (d.1649), a Shūdra peasant, might possibly have been influenced by the Chaitanya sect yet while addressing himself to Vithoba, the Lord of Pandhari, his God (Vitthal) tends to be closer to the Ram of the monotheist Kabir than to the Krishna of Chaintaya. He sings of the possibility of recourse to God by a devotee, howsoever lowly in status, and does not hesitate to use the word Allah for his God. Quite different in approach was his junior contemporary, Rāmdās (d.1681), who combined the propagation of the worship of Rama as God with the upholding of the dharma (“the Maharashtra Dharma”), i.e. maintenance of “the holiness of the Brahmans and deities”. He organized maths or centres of ascetics, and was patronized by Shivaji, the Maratha ruler (d.1680),

In Karnataka, the Dāsakūta movement seems formally to have belonged to Madhvächärya’s system. It originated with Shripadaraya (d.1492), but was mainly spread by his disciple Vyasaraya (d.1539). The songs of the sect in Kannada show attachment to Viththala, the deity of Pandharpur, and yet revel in an ecstasy of devotion which recalls Chaitanya. A disciple of Vyasaraya, Kanakadas was a shepherd (Kurub) and in his popular compositions insisted on the lowly to the Lord.

Logic and dialectics (nyaya and tarka) continued to attract attention through the compilation of commentaries and text-books. The Navadvip schools produced Raghunātha Siromani’s commentary (c.1500) on Gañgesha; and on this commentary Gadhādara (c.1700) in turn commented. Shañkara Mishra in Upaskära (c.1600) commented on the Nyāya-sütra. Among textbooks, Annam Bhațța wrote Tarkasamgraha (c.1585) and Jagadisha, the Tarkamyita (c.1700). A.B. Keith comments unfavorably on the obscurity and scholasticism of this literature; he also notes that all the schools were now “fully theistic”.

The survival of the materialist ideas of the Chārvākas, described in the Dabistān as constituting the ninth tradition within Hinduism, is of considerable interest. The Chārvākas believed that only the world perceived by the senses was real; “whether one becomes high or low results from the nature of the world”, and not from divine direction. The existence of a Creator or of gods was denied, and so also the truth of the Vedas. A number of specific criticisms by them of the beliefs in the miraculous and divine are quoted; possibly these circulated by word of mouth or are derived from the texts of opponents, for our author does not name any text or votary of the sect for his source.

The main area of strength of Jainism during this period was Gujarat, though Jain communities were found elsewhere too. Jain religious literature was composed in Gujarati, Sanskrit, Präkrit, Braj, Kannada and other languages, but much of it is described as repetitive or hagiological. The Jain version of dialectics was set out by Yashovijayaji in Jaina tarka-bhāshā, c.1670; he was the author of other religious books as well. Both the sects of the Jains, the Shvetāmbara and Digambara, flourished in the Vijayanagara empire. Jain priests also claimed exceptional proximity to Akbar and his court. The Jain laity was increasingly confined to “the Banya and Bohra castes of tradesmen, most of them selling foodgrains and some taking to service” (Dabistān).

A change of substantive proportions in the Indian mode of religious thought was marked by the preaching of the weaver Kabir (d., c. 1518) of Varanasi. One could, on the other hand, see in his compositions a distilling of Vaishnavite, Nath-yogic, even Tantric beliefs to obtain a rigorous monotheism, parallel to the Islamic; or see, alternatively, a rigorous acceptance of the logic of the monotheism of Islam, while rejecting its theology, with the exposition necessarily offered in a language that those outside the culture of Islam could understand. Strong arguments can be urged in favor of both views; but in whatever manner Kabir came to espouse the views he proclaimed, his contemporaries were deeply struck by their boldness and vigor.

A change of substantive proportions in the Indian mode of religious thought was marked by the preaching of the weaver Kabir (d., c. 1518) of Varanasi. One could, on the other hand, see in his compositions a distilling of Vaishnavite, Nath-yogic, even Tantric beliefs to obtain a rigorous monotheism, parallel to the Islamic; or see, alternatively, a rigorous acceptance of the logic of the monotheism of Islam, while rejecting its theology, with the exposition necessarily offered in a language that those outside the culture of Islam could understand. Strong arguments can be urged in favor of both views; but in whatever manner Kabir came to espouse the views he proclaimed, his contemporaries were deeply struck by their boldness and vigor.

Kabir propounded an absolute monotheism that countenanced no image-worship and no ritual. Servitude to God rather than offer of love to Him is the true means of salvation – love, though not absent, is clearly a subordinate element. This weakens any argument that Kabir derived his thought from either Vaishnav bhakti or Islamic Sufism. It was by one’s faith in God and work in this life one would be judged by God, for –

Kabir, the capital belongs to the Sah (Principal Merchant/Usurer)

And you waste it all.

There would be great difficulty for you

At the time of rendering of accounts.

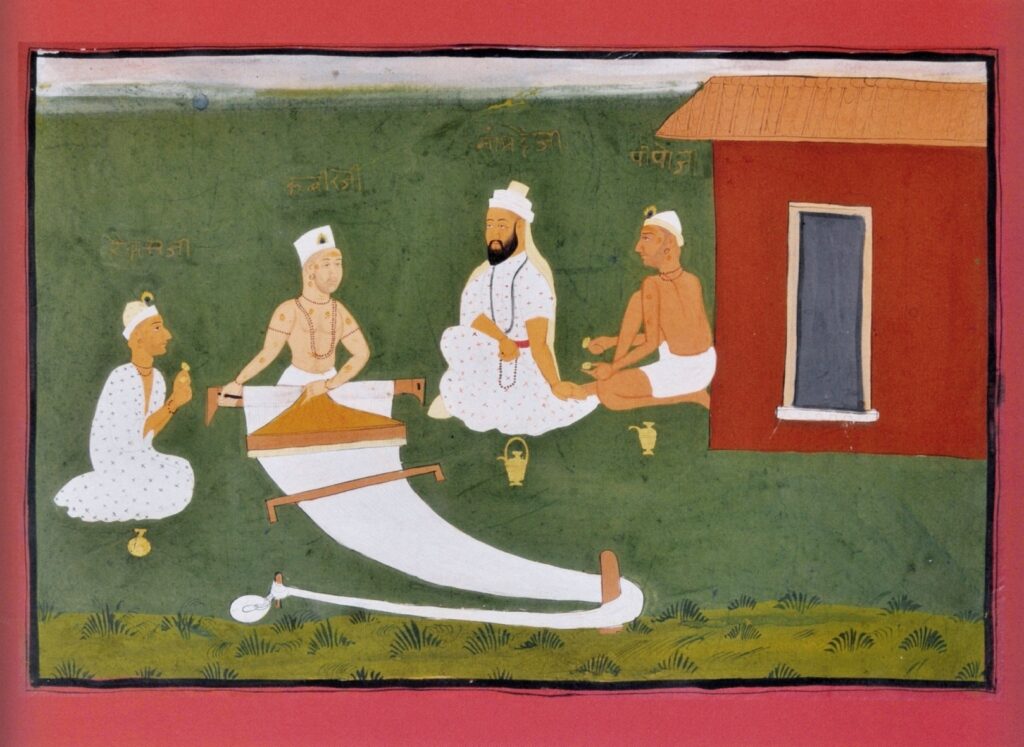

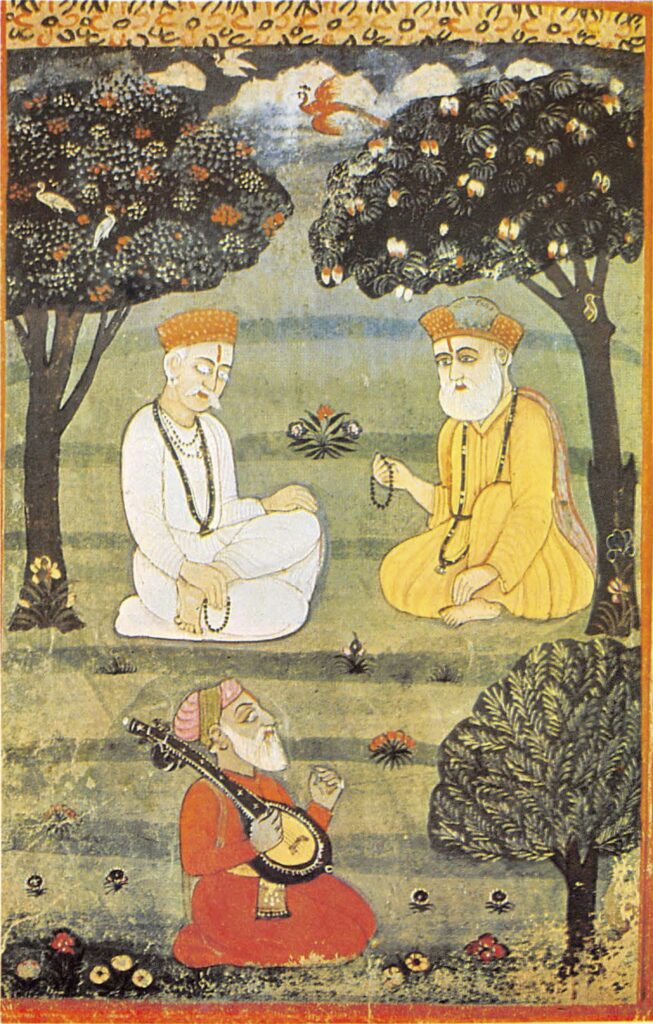

Kabir with Namadeva, Raidas and Pipaji. Jaipur, early 19th century

The Islamic influence in this concept of exact measurement of one’s thought and deed at the Day of Judgement is manifest; at the same time, the vision of God as a usurer certainly reflects not the traditional Muslim, but the impoverished artisan’s natural view of the Master. But if Kabir warns of punishment, he does not look forward to a heaven where one’s desires would be fulfilled this marks another departure from Islamic theology:

As long as man desires to go to heaven,

So long he shall find no dwelling at God’s feet.

Kabir’s rejection of the concepts of ritual purity and pollution, the laws of the smritis and the caste system is uncompromising in its completeness. As a late-sixteenth century summary of his teaching tells us, Kabir refused to acknowledge caste distinctions or to recognize the authority of the six schools of Hindu philosophy; nor did he set any store by the four divisions of life (ashrams) prescribed by the Brahmans.

As for the two contending religions, Kabir says scornfully: The Hindu dies crying “Rām”, the Muslim, “O Khudā (God).”

Says Kabir: He who lives, shall not go amongst either.

And then the triumphant revelation:

Ka’ba has once more become Kāsi, Rām has become Rahim!

Moth (a coarse pulse) has become fine flour; so sits down Kabir to enjoy it.

To a region, now torn in the struggle between temple and mosque, this teaching still retains a living and vibrant message.

Kabir’s audience was the common man, the artisan, the peasant, the village headman; his similes and metaphors came from their life and travels; and his language was the tongue that they spoke. Different regional dialects have left their imprint on his original Awadhi, as he or his verses traveled about. True, he is also influenced by some of the prejudices in his environment (chiefly poor and male) against women. Still, he had found a new dignity for the poor and the downtrodden in the world of his Lord. So came now a procession of his peers, lowly like him, seeking God in this land of Homo Hierarchicus. No one can, perhaps, improve upon how in 1604 Arjan, the fifth gurū of the Sikhs, saw this dramatic movement and made Dhannā, a Jāt peasant, sing of it.

To a region, now torn in the struggle between temple and mosque, this teaching still retains a living and vibrant message.

The evidence of their compositions show that Ravidās (or Räidās), the worker in hides, and Sain, the barber, both belonging to the sixteenth century, regarded Kabir as their precursor. A similar position with regard to Kabir was adopted by Dadū, the cotton-carder (d.1603), who obtained a considerable following in Rajasthan. A little later (1657) there appeared in Haryana the Satnāmi sect, again owing explicit allegiance to Kabir, and counting among its followers “peasants and tradesmen with small capital”. The sects of the follower of these teachers were called panth; in time, in spite of preserving the anti-ritualistic compositions of their founders, these tended to develop rituals of their own and to introduce notions and institutions taken from traditional religion, notably the ascription of avatār status to their original preceptor, and a caste-like status to the monotheistic community itself. Even a Brahman parentage came to be sought for Kabir, the weaver. Such a reshaping of the original message of the masters, is a testimony to the strong roots of ritual and the caste-order in those times; and our own times are, perhaps, no different.

The sixteenth century saw the rise of Sikhism, now one of the recognized religions of the world. It began as a sect (panth) of the followers of Gurū Nanak (1469-1538), a Khatrī (an accountant and mercantile caste) of the Panjab, more or less on the pattern of other sects of the contemporary popular monotheistic movement. The Gurü Granth Sahib, the scripture of the Sikhs, compiled by Gurū Arjan in 1604, includes, besides compositions of Nānak and the succeeding Gurus, those of the Muslim saint Shaikh Farid, and of Nāmdev, Kabir and Ravidās and other bhagats (saints), in the same manner as such compositions are included in the compilations of the Dādū panthis, viz., the Panchvānīs and the Sarbangī of Rajjabdās. This suggests that, at least till the beginning of the seventeenth century, there was a strong sense among Gurū Nānak’s followers that they belonged to a general monotheistic movement, with only some differences of both nuance and substance separating its different components.

Gurū Nanak believed in One God, and saw an intensely personal relationship between Him and the devotee, who would humbly serve and love Him and obtain His grace in return. At the same time God was formless and omnipresent and could not be represented in a physical form. Image worship and ritual were thus condemned. Nānak strongly emphasized ethical conduct, especially kindness to fellow human beings. He condemned arrogance of birth, the cult of ritual pollution and differences of caste. The salvation to be aimed at was nirvān or sach khand, the true abode, when man at last realizes God.

The Gurü Granth Sahib, the scripture of the Sikhs, compiled by Gurū Arjan in 1604, includes, besides compositions of Nānak and the succeeding Gurus, those of the Muslim saint Shaikh Farid, and of Nāmdev, Kabir and Ravidās and other bhagats (saints), in the same manner as such compositions are included in the compilations of the Dādū panthis, viz., the Panchvānīs and the Sarbangī of Rajjabdās. This suggests that, at least till the beginning of the seventeenth century, there was a strong sense among Gurū Nānak’s followers that they belonged to a general monotheistic movement, with only some differences of both nuance and substance separating its different components.

It is not clear to what extent Gurū Nānak gave an organizational form to his sect, nor whether the word gurū used in his compositions, e.g. in Japjī, means God or spiritual guide. But two processes appeared soon enough. First, a line of Gurūs or spiritual successors to Nānak was established. Their status came to be exalted to incarnations of the same perfect spirit (each gurū being known as the mahalla from Arabic mahall, or station); and total obedience to the Gurū was expected from each disciple, the Sikh-Gurū, whence the abbreviated name Sikh.” The second was the expansion of the sect among the Jatts or peasants of the Panjab: the Gurus were all Khatris, but their principal lieutenants, the masands, were already mostly Jatts in the seventeenth century.

Nanak (right) and Mardana (foreground) with Bhagat Kabir (left). This painting is found in the B-40 Janamsakhi, written and painted in 1733. The painting was made by Alam Chand Raj

These two developments provided ground for a third, the acquisition of armed power. After the martyrdom of Gurū Arjan (1606), a conflict with the Mughal authorities could not be long avoided. The military power of the Gurüs reached its apex under the tenth and last Gurū, Gobind Singh (1666-1708). In 1699 he sought to weld his followers into a militant community (Khālsa’) by prescribing a common baptism for men of all castes and appointing the items everyone had to carry, including the dagger or sword (kirpān), which was part of the public bearing of a professional soldier of the time.

Immediately after Gurū Gobind Singh’s death at Nander in the Deccan (1708), his disciple Banda Bahādur returned to the North and raised a massive plebeian rebellion, in which Sikhs, including many fresh converts, joined along with discontented zamindars. He operated over large portions of the Panjab and Haryana plains, retiring to the hills for some time. The rebellion was ultimately suppressed, and Banda was executed in 1716. A period of demoralization and division followed, but recovery began as Mughal power collapsed under the impact of Nādir Shāh’s invasion (1739) and the repeated invasions of Ahmad Shah, the Afghan ruler (1747-73). From the 1750s onwards, the Sikh dals and misals (groups) became more and more powerful, led by individual chiefs (sardārs), who organized troops of increasingly professional mounted musketeers. Many of the chiefs came from peasant or artisan stock, like one of their foremost leaders at this time, Jassa Singh, reputed to be originally a carpenter. A semblance of unity was sought to be maintained by the tradition of an annual ‘sarbat Khālsa‘ at Chak Gurū (Amritsar); but dissensions grew apace, and each chief tended to carve out a separate territory for himself. The process was at last checked by Ranjit Singh (1780-1839), who established a traditional kingdom in the Punjab, ostensibly in the name of the Khālsa.

Islam in India remained ideologically so closely linked to the main currents of Islamic thought transmitted through Arabic and Persian that it may not perhaps be wholly correct to speak of “Indian Islam” as an isolated compartment within the larger world of Islam. Such specificities in customs and beliefs as existed here were partly linked to the fact that India had much greater association with Iran and Central Asia than with the Arab countries. The continued co-existence with Hinduism brought into focus, in course of time, the problem of assessing non-Muslim faiths and beliefs. Sufism or Muslim mysticism, whose ‘chains’ (silsilahs) came from Iran and Central Asia, found a congenial soil in India. By the sixteenth century Sufism had been accepted by most orthodox theologians as a permissible discipline so long as the formal requirements of Sharīa, the law and ritual of Islam, were met. But the comfortable arrangement was seriously disturbed when mysticism opened the doors to the pantheistic doctrines and speculations of ibn al-‘Arabi (d. Damascus, 1240).

It may be justly held that ibn al-‘Arabi’s views were a bold but logical elaboration of the sufic concept of communion with God (fana). With him Separation, from being unnatural, became illusory, and the communion, from being the ultimate object, became the only eternal Reality. His doctrine of Wahdat al-Wujüd (Unity of Existence) had, by the latter half of the fourteenth century, begun to influence sufic circles in India and, despite opposition, had steadily gained adherents. For a country like India, where Islam’s co-existence with the totally different religious tradition of Hinduism could not but lead to inner questioning, ibn al- Arabi’s doctrines seemed to offer a persuasive explanation of diversity that belonged only to the sphere of illusion. Alongside this, there was the proposition of the Perfect Man (insān al-kāmil), in which ibn al-‘Arabi idealized the mystic guide (shaikh) as ‘a microcosm in whom the One is manifested to Himself. This vision inevitably supplemented or reinforced the concept of mahdi, the reformer and redeemer coming in advance of the Day of Judgement, the expectation of whose arrival was part of popular Muslim beliefs. The two concepts could influence each other, and as the close of the first millennium of Islam drew near (AH 1000 = AD 1592), they produced a millenary wave.

The Mahdawi movement was the first indication of the new intellectual turbulence. Saiyid Muhammad of Jaunpur (d.1505), a well-traveled scholar, proclaimed himself Mahdi. Apparently, the hope for redemption by following the Mahdi’s message and his call for ethical conduct, continued to win followers for his sect, who began to establish their communities (da ‘iras) at various places. Theologians tirelessly denounced them; but the sect survived.

In the last quarter of the sixteenth century in the Kabul province of the Mughal Empire there arose another sect with similar millenary tendencies, except that its founder Bāyazid (Miyän Raushan) (d.1585) claimed that he was a Prophet (nabi), and not a Mahdī. Believing in a pantheistic mysticism, he envisioned the state of sukunat, where the self merged with God. His refusal to countenance anyone who refused to accept his message helped forge the Raushaniyas into a militant sect among the Afghans, in whose language (Pashtu) his book Khairu i Bayān was composed. The Raushaniya militancy led to a long war with the Mughals, during which the sect was suppressed.

The great upheaval in thought that was to come under Akbar (emperor, 1556-1605) had its origins partly at least in the same two intellectual impulses of Pantheism and the Messiah-cult, which we have just discussed. Akbar’s religious interests initially lay within traditional Islam. His splendid city of Fatehpur Sikri, dominated by the great mosque, was built early in the 1570’s in honour of Shaikh Salim Chishti (d.1572), the sūfi saint. But in the 1570’s Shaikh Taju’ddin, a protagonist of ibn al-’Arabi, introduced his principal concepts at the Court. Shaikh Mubārak (d.1593) gained in influence, and not only had he read ibn al- Arabi and the Iluminationist (Ishrāqi) doctrines of Shihäbu’ddin Maqtūül (twelfth century), but had also been suspected of Mahdawi inclinations. The popular belief in the need of renewal at the end of the first millennium of Islam, and of a reformer for the purpose, lay partly behind Akbar’s direction in 1582 for the compilation of the Tarīkh-i Alafi, a history of the millennium beginning with the death of the Prophet. Akbar himself could be seen as such a reformer, while being identified as the Perfect Man in the ibn al-’Arabi tradition. An early limited application of this concept was attempted in the mahzar of 1579. This was a statement signed by leading Muslim theologians at the court, declaring that Akbar, in his position as a Just Sultan, was entitled to exercise limited powers of interpretation and elaboration of Muslim law, which was to be binding on all Muslims.

Akbar’s religious interests initially lay within traditional Islam. His splendid city of Fatehpur Sikri, dominated by the great mosque, was built early in the 1570’s in honour of Shaikh Salim Chishti (d.1572), the sūfi saint. But in the 1570’s Shaikh Taju’ddin, a protagonist of ibn al-’Arabi, introduced his principal concepts at the Court.

The growing influence of pantheism, however, soon took matters beyond the rather modest and sectarian position assigned to the Emperor in the mahzar. Discussions had taken place in the presence of Akbar, among representatives of Sunni Muslim scholars, at a special building, the “ibadatkhana (house of prayer), at Fatehpur Sikri. These discussions and debates were now extended to involve Muslim divines, Sunni and Shi’a, şūfis and rational scholars (hakims), and, subsequently, Brahman scholars, other Hindu recluses, Jains, Parsis and Christians (Jesuits), whose first mission reached the court in1580. These discussions convinced Akbar that no single interpretation of Islam was correct or even forthcoming, and further that no single religion could be true, but that all drew, but only in part, upon the same Truth. It was for him, as the chosen man of God, to assist in the realization of a consciousness of Absolute Peace (Sulh-i Kul) in order to prevent idle strife between the votaries of different religions and factions. It was held that both “religion (din) and the, secular world (duniya)” were patterns drawn by “the cloud of duality,” that is, by consciousness of an existence separate from God. This being so, all religions were to be tolerated, but did not need to be followed.

Jesuits at Akbar’s court

For an elite corps of disciples (irādat-gazinān), there was prescribed by Akbar a total submission to the imperial preceptor and certain principles and code of conduct, which his son Jahangir summed up as follows:

Let the disciples not blacken and spoil their time by engaging in hostility with any religious community and let them follow in their relations with members of all religious communities the path of Absolute Peace (Sulh-i Kul). Let them not kill any animal by their own hand, nor wear weapons except in battle or chase… Respect must be shown to the Sun and the Moon, which exhibit the Light of God, according to the degrees of each. God must be conceived as the true Creator and Cause in all times and circumstances, and one should so meditate on this that, whether in seclusion or in company, one’s thought should not be away from God for a single moment.

It may be mentioned that there is no sanction for the belief that Akbar wished to institute any new religion or that it was called Din-i llāhī.

The growing influence of pantheism, however, soon took matters beyond the rather modest and sectarian position assigned to the Emperor in the mahzar. Discussions had taken place in the presence of Akbar, among representatives of Sunni Muslim scholars, at a special building, the “ibadatkhana (house of prayer), at Fatehpur Sikri. These discussions and debates were now extended to involve Muslim divines, Sunni and Shi’a, şūfis and rational scholars (hakims), and, subsequently, Brahman scholars, other Hindu recluses, Jains, Parsis and Christians (Jesuits), whose first mission reached the court in1580.

The policy of equal treatment of all religions (as distinct from a simple policy of tolerance) that Akbar enforced, permitting full freedom of religious expression, conversion and construction of places of worship to all, was consistent with his views as they came to be formulated by the early 1580’s. It was, perhaps, a policy for which it was not easy to find a parallel in the contemporary world – a fact underlined with great pride by his son. It is, however, more likely that Akbar’s own views took direction, because a policy of tolerance was politically very useful and had, indeed, been adopted much before his philosophical views took the form they did in the last twenty- five years of his life. His minister Abu’l Fazl declared that sovereignty is itself in the nature of farr-i izadi, God’s light, and the sovereign, like God, was parent to all mankind; it was therefore his function to ensure that “out of differences of religion, there does not arise the dust of antipathy.” This declaration, it will be seen, draws not on any philosophical or religious tradition, but on a simple assertion of the Sovereign’s absolute power, and the obligation that such absoluteness imposed on him, to keep all his subjects contented.

It is, however, more likely that Akbar’s own views took direction, because a policy of tolerance was politically very useful and had, indeed, been adopted much before his philosophical views took the form they did in the last twenty- five years of his life.

Akbar’s proclamation of belief in pantheism and șulh-i kul, in its turn, had some significant ideological consequences, in that it suddenly threw open orthodox beliefs to criticism ôn the most delicate issues of ethics and theology. Internally, it created within Islam, a recognized niche for the Shi’ite trend in spite of considerable polemics existing between Sunnis and Shi’as. It provoked restatements of orthodox position, while it also generated a fresh interest in reason and science. Finally, a most interesting movement was fostered among Muslims towards a study of Brahmanical texts and of Vedānta, with a view to obtaining a knowledge of “truth” as perceived by Hindus. Akbar initiated a series of translations of Sanskrit works, among which the religious literature included the Atharva-veda, the Mahābhārata, and the Rāmāyana, while the Yogavasishtha was translated for Akbar’s eldest son Salim (the later Jahāngir). In the Ai’n-i Akbarī, Abūl Fazl was able to give a fairly cogent and accurate description of the various Hindu schools of philosophy, theology, beliefs and laws, based on a fresh scrutiny of the texts through translations made “after much difficulty”. Such scrutiny exhibited much common ground between Islam and Hinduism, since “though in some of the purposes and arguments there is room for dispute, it became established that the Hindus believe in the worship of God and in monotheism” (Abū’l Fazl). There is a greater appreciation of the logic of the Karma doctrine; and later, with Jahāngir, came the recognition that Vedānta “is the knowledge of taşawwuf (mysticism)”, presumably because it was pantheistic.

A painting depicting the scenes of the Ibādat Khāna. (Wikipedia Commons)

Islam’s recognition of Hinduism reached its culmination in Dara Shukoh (1615-59), the eldest son of Emperor Shähjahān. Därā began his intellectual career with an immersion in Muslim mysticism through attachment to the Qadiriya order of Mian Mir (d.1635) and Mulla Shah Badakhshi (d.1661); and his early writings were on Muslim mystics. But interest in monotheism and mystic practice led him to the composition of the Majma ‘u-l Bahrain (‘the mingling of two oceans’) in 1654-55. In this tract he explains the major terms and concepts used in Hindu spiritual discourse, and sees an identity between the Hindu and Muslim seekers of God, in all things except language. In 1657 came what was, from the philosophical point of view, the most important effort: a translation of fifty-two Upanishads, under the title Sirru’l Asrar, the Great Secret, a faithful rendering of very difficult texts.

Islam’s recognition of Hinduism reached its culmination in Dara Shukoh (1615-59), the eldest son of Emperor Shähjahān.

This was in some respects a momentous event, since it was this translation which, from its being rendered into Latin by Anquetil Duperron (1801-02), led ultimately to a world-wide recognition of the philosophical richness of these ancient texts. In 1655-56 at Dara Shukoh’s instance Habibullah made a fresh translation of Yogavasishtha.

Indicative of the spirit of the times is a work already referred to, the Dabistān (‘School), written in 1653 by an author who does not divulge his name or religion, but incidentally gives many facts about himself, which suggest he was the member of a Parsi sect, with the pen-name ‘Mobid’. He set out to write in Persian a work giving a truthful, unbiased account of all religions, and so deals in his work with the Parsis, Hindus, Buddhists (Tibetan), Jews, Christians and Muslims, along with different sects within each religious tradition. Most of the information was gathered by the author himself by his reading of the writings of the votaries of each sect or by his conversations with them. His linguistic equipment appears to have been considerable; and it is doubtful whether a work of this kind existed in any other language at this time. Clearly, even if the author was not a Muslim, but a leading light of a Parsi sect, his readership, given the language in which he wrote, consisted largely of Muslims. That the interest it evoked among them was widespread is shown by the large number of manuscripts of the work that have survived.

The freedom of religious discussion accorded to all under Akbar assisted in the transformation of Shi’ism from a ‘heresy’ into a recognized variant of Islam in India. Qāzi Nūrullah Shustarī (1549-1610) was the first isnā- ‘asharī Shi’a theologian in India to have left important writings. Disdaining taqiyya (or permitted dissimulation), expressly on account of the freedom accorded under Akbar, he openly defended Shi’ite position against Sunni criticisms. He died in 1610 as a result of physical punishment inflicted on him at Jahāngir’s orders and is considered a Shi’a martyr. Though the details of the incident are obscure, it was apparently not a part of any general persecution of the Shi’as. Immigrants from Iran, who were mostly Shi’as, held high offices in the Mughal empire; and Shī’a observances were publicly held. Haidarabad in the Deccan in the seventeenth century and Lucknow and Faizabad in Awadh in the eighteenth, became important centres of Shi’ite learning.

Muslim or Sunni orthodoxy responded in various ways to challenges from the free airing of views hitherto thought to be unacceptably heterodox. How complex the responses could be is shown by the ideas of Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi (1564-1624). His first surviving work, a rather slight tract, is devoted to a refutation of Shi’a beliefs (Risāla dar radd-i rawāfiz). His strong attachment to the Shari’a was displayed in his hostility to Akbar’s policies of tolerance and in his bitter opposition to Hindus and Hindu beliefs that he gives expression to in his letters soon after Akbar’s death. But he had in the meantime (1600) become a disciple of the Naqshbandi mystic Bãqi Billāh (d.1603); and from this point onwards he became increasingly concerned with Ibn al-‘Arabi’s theories of Unity of Existence (wahdat al-wujud) and the Perfect Man. His acceptance of the first idea was only partial. The seeker, he asserted, must transcend this notion in order to grasp separateness, the unity being for him now, only the unity of all that he sees, for in the final stage he looks only at God and none else (wahdat ash- shuhud). A rigorous conformity with the Sharī’a was to him as much a requisite for the mystic as for anyone else; and he condemned all innovations. Ibn al-‘Arabi’s theory of the Perfect Man was, on the other hand, incorporated in Sirhindi’s own concept of the qaiyum (‘the maintainer ‘). The possessor of gnosis (ãrif). by being the Perfect Man, is chosen as the qaiyüm, or God’s vizier or vicegerent, and thus attains a function assigned previously to prophets. This function is identified with yet another- that of the renovator (mujaddid) of Islam in its second millennium (alf-i șān). It was clear that to him and his followers both the offices of qaiyüm and mujaddid were united in Shaikh Ahmad himself.

In Mughal India Shaikh Ahmad’s seems to have been the last major statement of a claim to be the Chosen Man within the framework of Islamic theology. Predictably, it invited criticism, notably from ‘Abdu’l Haqq Muhaddiş; and Emperor Jahāngir had Sirhindi briefly imprisoned (1619).

There was, by the side of Shaikh Ahmad’s mystical revivalism, a restatement of the orthodox position in terms of what might be called the Islam of Ghazāli’s conception, a combination of Law (Sharı’a) and Mysticism (Tariqa). The restatement was, by definition unoriginal, though much learning and care often went into it. ‘Abdu’l Haqq Muhaddis (1551 1642), already mentioned, was a prolific writer on Muslim law and a recognized authority on hadīş, or sayings of the Prophet. Yet he fully accepted the sufic tradition, being the author of a volume of biographies of Indian mysties; and he inherited from his father a belief in wahdat al-wujüd. He could also sympathetically refer to the radical monotheist Kabir, while recognizing him to be neither Muslim nor Hindu.

Emperor Aurangzeb (reigned, 1659-1707), despite his patronage of the descendants of Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi, could not accept the latter’s extreme spiritual claims, and generally supported traditional and legal Islam. This was particularly shown by his commissioning of the massive work Fatāwā-i ‘Alamgiri, prepared in Arabic by Shaikh Nizām with the assistance of many scholars and designed to be a comprehensive compendium of jurists’ opinions on diverse matters, systematically arranged.

The Mughal Empire in its decline brought forth the important Muslim thinker and jurist, Shäh Walilullah (1702- 1762). He was exceptional in reflecting on the oppression of peasants and craftsmen as factors behind the decline of the Empire; an oppression he ascribed to growth of love of luxury among the ruling classes. He sometimes linked the enforcement of the various elements of the Shari’a to particular social needs, though these were rather naively formulated. Thus usury is prohibited, because if it is practiced, people would tend to abandon agriculture and crafts altogether in pursuit of usurious gain. On other matters, such as concerning Shi’as, he took an orthodox Sunni position, and translated Sirhindis polemical anti-Shi’a tract into Arabic. He was fairly harsh on non-Muslims who were to be the hewers of wood and drawers of water under an ideal Sharī’a regime. Shäh Waliullah largely accepted the sufic heritage of Islam. Claiming to be a spiritual guide (murshid) himself, he propounded an ‘inspired’ (not reasoned) reconciliation of wahdat al-wuyjüd with Sirhindī’s theory of wahdat ash-shuhūd. Hereafter the element of pantheism in Indian Islamic thought seems to have increasingly receded into the background.

Emperor Aurangzeb (reigned, 1659-1707), despite his patronage of the descendants of Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi, could not accept the latter’s extreme spiritual claims, and generally supported traditional and legal Islam. This was particularly shown by his commissioning of the massive work Fatāwā-i ‘Alamgiri, prepared in Arabic by Shaikh Nizām with the assistance of many scholars and designed to be a comprehensive compendium of jurists’ opinions on diverse matters, systematically arranged.

Syrian Christian and Jewish communities had long lived on the Kerala coast, the Red Sea trade keeping alive their contacts with easternm Christendom and Judaism. With the arrival of the Portuguese, Catholic Christianity also arrived: Francis Xavier (1506-52) was the great pioneer of Catholic missionary activity. Another Jesuit, the Italian Robert de Nobili (1577- 1656), tried the innovation of presenting Christianity in Indian garb, incorporating the caste system by having separate churches for the upper and the untouchable castes. Much use was made by the Jesuits of the printing press to produce literature on Christianity in Indian languages. Goa became an archdiocese in 1557. The decline of Portuguese power, however, affected Catholic activity, and in 1653 a number of Syrian Christian communities in Kerala, which had been previously pressed or persuaded into accepting Papal authority, shifted to their older allegiance to Antioch. In 1759 Portugal itself suppressed the Jesuit order (‘Society of Jesus’). But Catholicism long remained the only version of Christianity that Indians could more easily become familiar with. The Dabistān, in its chapter on Christianity, provides a fairly accurate statement of Catholic beliefs, but the author seems entirely unaware of the Protestant Reformation.

The direct effect of Christianity on the mainstreams of Indian religious thought, whether Hindu or Islamic, was as yet limited; the impact became significant only in the first half of the nineteenth century.

The first Lutheran missionaries under Danish patronage, arrived in 1706 at Tranquebar (Tamilnadu), and one of them, Ziegenbalg, translated the four Gospels into Tamil in 1714. The direct effect of Christianity on the mainstreams of Indian religious thought, whether Hindu or Islamic, was as yet limited; the impact became significant only in the first half of the nineteenth century.

Irfan Habib (born 1931) is an Indian historian of ancient and medieval India, following the approach of Marxist historiography. He is well known for his strong stance against Hindu and Islamic fundamentalism. He has authored a number of books, including Agrarian System of Mughal India, 1556–1707.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Outstanding writing! Thank you so much for bringing your knowledge of history to light.