Ramesh Chandra Majumdar (1888-1980), or R.C. Majumdar – as he is better known – is not just a major historian of the past century but also one of its intriguing figures. His vast body of work, written across a long career, ranges from ancient to regional to international histories and includes a history of the independence struggle as well as an extensive (if controversial) series which he edited and contributed to called The History and Culture of the Indian People. Appointed by the government to head a committee to write the history of the freedom struggle, he left over differences with the Education Ministry, publishing his own work on the subject separately instead. (You can read more about him in his bio.)

Even those who contradict or differ from him, make an allowance for his scholarship. Marxist historian Irfan Habib, for instance, disagrees vehemently with some of Majumdar’s interpretations, particularly those running through The History and Culture of the Indian People. Writes Habib:

“To him the entire period from c. 1200 onwards was one of foreign rule; Muslims were alien to Indian (Hindu) culture; the Hindus, oppressed and humiliated, wished nothing better than to slaughter ‘the Mlechhas’ (Muslims); the British regime was a successor more civilised than ‘Muslim rule’; yet real opposition to the British came from Hindus, not Muslims, even in 1857; and, finally, the national movement’s course was throughout distorted by concessions made to Muslims by Gandhiji, who was so much personally to blame for Partition.”

“The often unproven hypotheses and inferences that he bequeathed,” writes Habib. “Have all become firm truths for a very large number of educated people in India.”

Nonetheless, Habib states unequivocally that Majumdar was a “distinguished”, “tall” and “serious” historian and “whatever he speaks is on facts that all historians admit to be true”. Further, that Majumdar’s “great industry must extract admiration from his worst critics”.

Ramachandra Guha, in his book Democrats and Dissenters laments the lack of “conservatives of the past” like Majumdar; a historian “with whom one could have a debate”.

The excerpt we are carrying below is from Majumdar’s Historiography of Modern India, published in 1970. It was curated for Swapan Dasgupta’s Awakening Bharat Mata: The Political Beliefs of the Indian Right, which comprises – after three introductory chapters spanning 150 pages by Dasgupta, establishing context – a collection of primary sources expressing the Indian conservative viewpoint; interviews, addresses and writings with and/or from personalities as varied as Sister Nivedita, Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay, R.G. Bhandarkar, V.D. Savarkar, Ramananda Chatterjee, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, V.S. Naipaul and historians like Jadunath Sarkar and R.C. Majumdar.

In the following excerpt Majumdar points out flaws in Indian historiography (the writing of history based on a critical examination of sources) around three broad areas:

– A false glorification of India’s early past, such as in K.P. Jayaswal’s “theory of a Parliamentary form of Government in Ancient India, which is a replica of the British Parliament including the formal Address from the Throne, etc.” Also, “conscious attempts” made to “explain away, ignore, or minimize, the harsh treatment accorded by the high caste Hindus to the lower castes, particularly Sũdras and Caṇḍālas”. Also, the Gandhian idea that non-violence as an ideal “has been followed throughout the course of Indian history”.

“One rubs his eyes with wonder,” writes Majumdar. “For not only are all the known facts of Indian rulers against the assumption that they were averse to war, but war has been recommended by political texts as a normal practice and sanctioned by religion through the aśvamedha sacrifice and eulogy of digvijaya. The Court-poets flattered the patron king by giving him the proud epithet of ‘hero of hundred fights’.”

– Secondly, with regard to Medieval India, Majumdar sees “a distinct and conscious attempt to rewrite the whole chapter of the bigotry and intolerance of the Muslim rulers towards Hindu religion… prompted by the political motive of bringing together the Hindus and Musalmans in a common fight against the British.” This can be seen, according to Majumdar, in the repudiation of charges that “Muslim rulers ever broke any Hindu temple”, the assertion “that they were the most tolerant in matters of religion” and that “the Hindu population was better off under the Muslims than under the Hindu tributaries or independent rulers”, the exoneration of “Mahmūd of Ghaznī’s bigotry and fanaticism”, and “several writers in India” defending “Aurangzīb against Jadunath [Sarkar]’s charge of religious intolerance.”

Similarly, Majumdar takes issue with the thesis “that the Hindus and Muslims had no cultural conflict” and most certainly with the assertion made by Lala Lajpat Rai “that the Hindus and Muslims have coalesced into an Indian people very much in the same way as the Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Danes and Normans formed the English people of today”.

Referring to a presidential address at a 1965 Indian History Congress, held at Allahabad, Majumdar writes: “We are told that ‘Akbar’s political outlook was an outcome of the accumulated political wisdom of the generations that had gone by and was a logical development inherent in the very nature of the situation’. Unfortunately, nothing is said about his successors, particularly Aurangzīb… ”

– Finally, when it comes to the British period, Majumdar feels “national sentiments” “prejudiced a calm consideration” of episodes such as “(1) the Black Hole Tragedy and character of Sirāju’d-daulah; and (2) the nature of the outbreak of 1857”. Later, he provides an illustration by way of the official history of the ‘Freedom Movement in Bihar’ (1957):

“Much has been said in it of Kunwar Singh as the local organizer and a hero of the great ‘War of Independence’ in 1857. But no mention has been made of a document which shows that the local sepoys, who had already mutinied, threatened to plunder his house and property if he did not join them. It can hardly be excused on the ground of ignorance, for it was the author of this history who first brought this document to light and published it in a local magazine.”

This illustration – of the author of a history (in this case Kalikinkar Datta), excluding from it a document of significance that the author had himself brought to light – brings us to the larger points Majumdar raises in this excerpt, which go beyond the areas of Indian historiography he points out flaws in, to what Majumdar sees as the root cause of these flaws.

For some of Majumdar’s historiographical assertions have themselves been questioned. The approach reflected in his generalized statement regarding “the whole chapter of the bigotry and intolerance of the Muslim rulers towards Hindu religion”, for example, has been refuted by Habib who examined Majumdar’s perspective alongside that of Ishtiaq Hussain Qureshi who projected “the history of ‘Muslims in India’… as a struggle for a separate nation right from A.D. 712, when Muhammad ibn Qasim entered Sind at the head of an Arab army.”

“In 1961,” writes Habib. “When I wrote an article criticizing what I held to be communal approaches by two distinguished historians, R.C. Majumdar and I.H. Qureshi, I noted that while their interpretations (mainly in laying blame or lavishing praise) were so different, their ‘facts’ were often identical, derived from the same evidence.”

Those interested in this debate might also like to read excerpts we have carried from Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya’s Representing the Other? Sanskrit Sources and Muslims and Manan Ahmed Asif’s The Loss of Hindustan – The Invention of India.

This particular excerpt, however, is more about the larger points Majumdar raises as to the roots of historiographical bias, which are as relevant today as they were then:

– Does History have an objective ‘greater’ than itself? Is “the real task of history” to “reveal the spirit of humanity and trace the course of progress towards liberty”?

Majumdar quotes passages from the proceedings of Indian History Congresses held in 1964 and 1965, which argue in favour of this:

“History has a mission and obligation to lead humanity to a higher ideal and nobler future. The historian cannot shirk this responsibility by hiding his head into the false dogma of objectivity, that his job is merely to chronicle the past. His task is to reveal the spirit of humanity and guide it towards self-expression.”

History must avoid “ghastly aberrations of human nature, of dastardly crimes, of divisions and conflicts, of degeneration and decay, but of the higher values of life, of traditions of culture and of the nobler deeds of sacrifice and devotion to the service of humanity.”

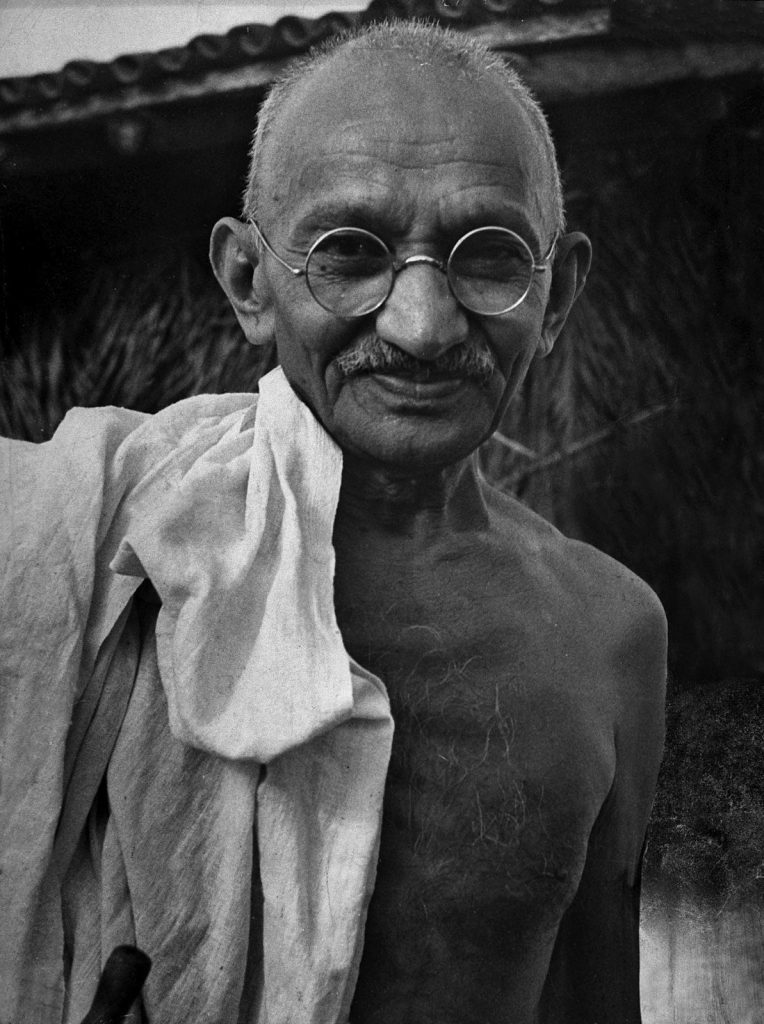

“The most important subject awaiting the critical touch of the historian, however, is the national movement, particularly the age dominated by Mahatma Gandhi, which restored the independence of the country. The historian has to get behind the external of the events and detect the spirit which animated them, and thereby reveal the soul of India. That approach alone will help to surmount the danger of provoking communal, regional, linguistic and class hatreds which unfortunately beset history writing.”

“In other words,” writes Majumdar. “History should record the spread of Buddhism by Aśoka, but not the horrors of the Kaliṅga war, carefully avoid all references to the devastation and massacre of Mahmūd of Ghaznĩ, destruction of temples by Aurangzīb, the Jallianwala Bagh massacre by General Dyer, the holocaust during communal riots, and so on. The reason for these omissions is that such things bring some ‘unhealthy trends which militate against the concept of national solidarity or international peace’.”

Majumdar rejects this idea of historical study entirely. “The real purpose of history,” he writes. “Is to report correctly the progress of events, which did not in all cases mark the progress towards liberty”.

To reiterate, he quotes Jadunath Sarkar:

“I would not care whether truth is pleasant or unpleasant, and in consonance with or opposed to current views. I would not mind in the least whether truth is or is not a blow to the glory of my country. If necessary, I shall bear in patience the ridicule and slander of friends and society for the sake of preaching truth. But still I shall seek truth, understand truth, and accept truth. This should be the firm resolve of a historian.”

– The second question: Is the historical data available suitable for the generalisations often posited by Indian historians?

Majumdar prefaces this question by quoting the views of certain European historians on such generalisations:

“No; there is no one rhythm or plot in history, but there are rhythms, plots, patterns, even repetitions. So that it is possible to make generalizations and to draw lessons.” —A L Rowse

“History is a series of interesting happenings, often illogical and cataclysmic, not a logical and orderly development from causes to inevitable results. In short, history

is full of ‘might have beens’, and these sometimes deserve as much attention as the actual, but by no means necessary, course of events.” —Sir Charles Oman

Then, writes Majumder: “But whatever view we may adopt in this matter so far as the history of Europe is concerned, our very inadequate knowledge of data in Indian history renders such generalizations a difficult and risky process.”

He quotes Sarkar again:

“We have yet to collect and edit our materials, and to construct the necessary foundation—the bed-rock of ascertained and unassailable facts—on which alone the superstructure of a philosophy of history can be raised by our happier successors. Premature philosophizing, based on unsifted facts and untrustworthy chronicles, will only yield a crop of wild theories and fanciful reconstructions of the past.”

– The third question: How can one save history from the policy of the government of the day “which is at best the policy of a political party”?

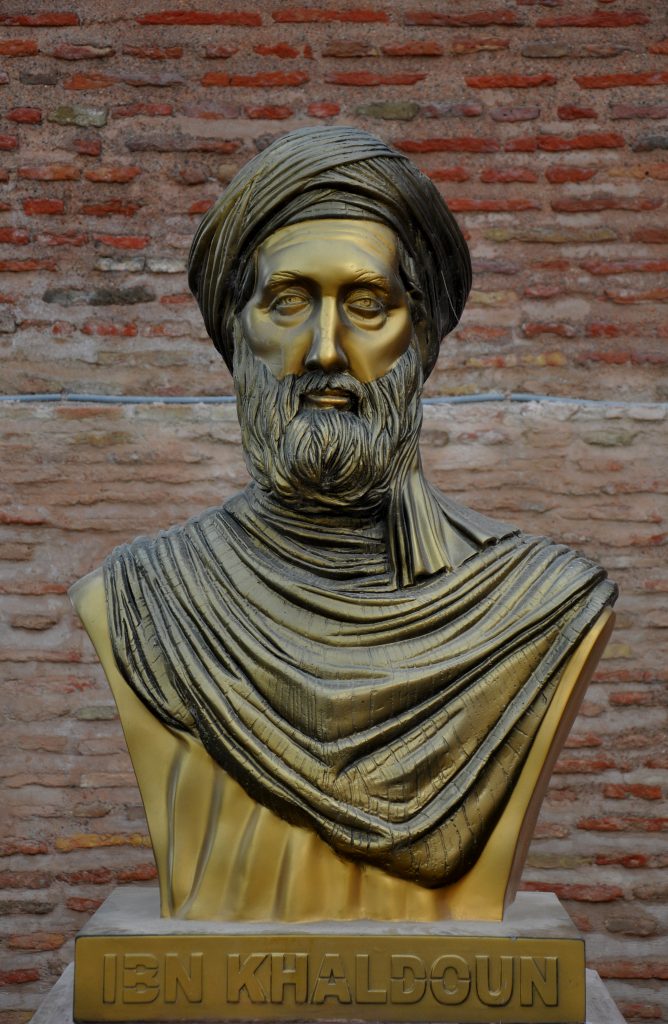

Majumdar quotes Arab historian Ibn Khaldun who includes, in a long list of defects of historians:

“a very common desire to gain the favour of those of high rank, by praising them, by spreading their fame, by flattering them, by embellishing their doings and by interpreting in the most favourable way all their actions.”

Majumdar places the Indian National Congress government squarely in the dock for ‘inspiring’ or at least ‘influencing to a large extent’ the trends in historiography which he has raised issues with. Also, for “seeking to utilize history for the spread of ideas which they have elevated to the rank of national policy to their own satisfaction”.

“They are not willing to tolerate any history which mentions facts incompatible with their ideas of national integration and solidarity,” he writes. “They do not inquire whether the facts stated are true or the views expressed are reasonable deductions from facts, but condemn outright any historical writings which in their opinion are likely to go against their views about such things as Hindu-Muslim fraternity, the non-existence of separate Hindu and Muslim cultures on account of their fusion into one Indian culture, etc.”

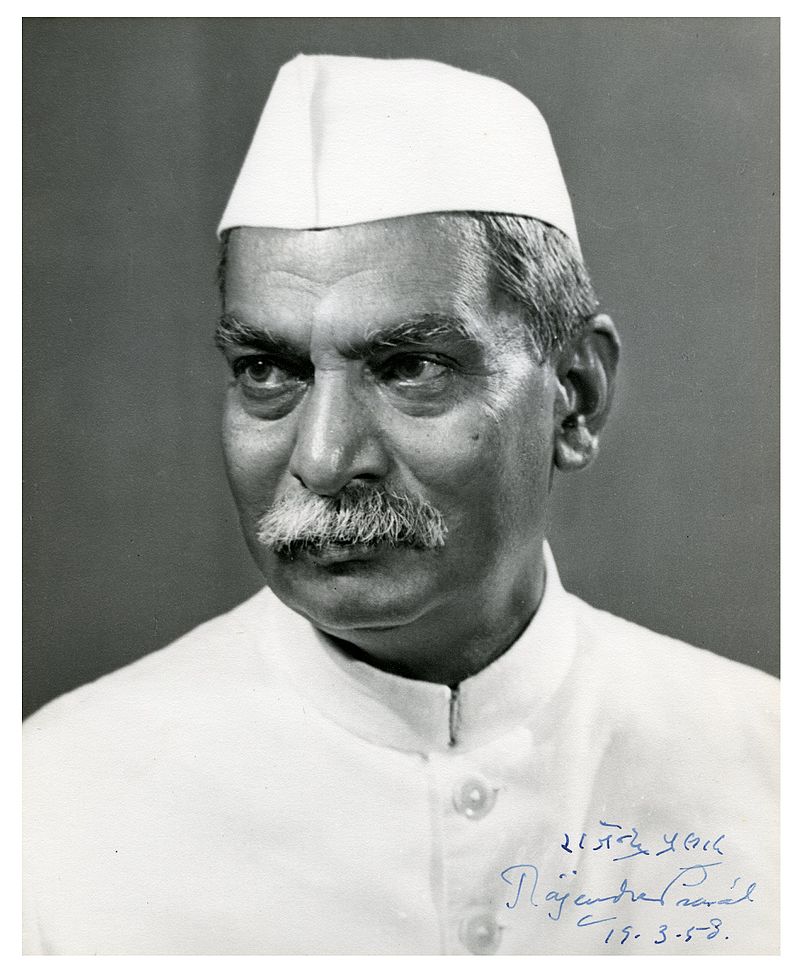

Majumdar shares the story of Jadunath Sarkar’s exchange with President Rajendra Prasad on what a national history of India should look like. According to Sarkar, it should “not… try to suppress or whitewash everything in our country’s past that is disgraceful”. Prasad’s reply throws light on what could be at least one real purpose of history:

“No history is worth the name which suppresses or distorts facts. A historian who purposely does so under the impression that he thereby does good to his native country really harms it in the end. Much more so in the case of a country like ours which has suffered much on account of its national defects, and which must know and understand them to be able to remedy them.”

To drive his point home, Majumdar ends by quoting a book which critiques historiographical research in the authoritarian Soviet Union:

“The partisan approach to history prevents the observer from recognizing the sanctity of objective facts and requires him, where necessary, to deny the evidence of his senses; for there are occasions when he must subordinate his own personal concept of truth to that held by an individual or group of individuals, namely the party.”

Why is all of this relevant today, when there is neither any Soviet Union in the world, nor an Indian National Congress leading the national government agenda? Because the “party system” underlined by Majumdar, that constitutes “dangerous impediments to the growth of true historiography” still very much exists. The “ideas… elevated to the rank of national policy” may have changed, but the principal idea – of utilizing history to spread these ideas – has not gone anywhere.

It is irrelevant, in this context, what you think of ideas such as national integration or cultural essentialism. What is relevant is whether you believe history should be subservient to any agenda but its own – which is finding out the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth – rather than national mythmaking.

It would be interesting to wonder how Majumdar might have reacted to the government of this day. He has referred to the killing of cows for the purpose of giving away their meat in charity – in the Mahabharata – in The History and Culture of the Indian People, and Habib often narrates an anecdote about him refusing to write for The Organiser after “it had published a paper alleging that monuments like the Red Fort and Taj Mahal had really been built by Hindu rulers”, and declining “to agree with K.M Munshi’s theory of an Aryan homeland in India”. In the following excerpt too, Majumdar refers in passing to a “recent acrimonious discussion on the killing of cows” and “a truly scientific spirit of history” being “sacrificed in discussions of such subjects as, ‘Did the Aryans come to India from outside?’, ‘Was there a caste system in the Ŗgveda?’”

R.C. Majumdar – whether or not you agree with him – was nobody’s fool. He was an independent and unique mind, which many of us haven’t heard enough from. It is time that – irrespective of what our ideological or historiographical convictions are – we hear more of what he had to say.

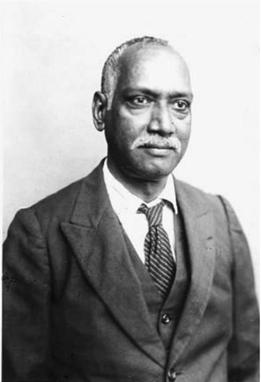

R.C. Majumdar

So far about the British historians. As regards the Indian historians the chief defect arose from national sentiments and patriotic fervour which magnified the virtues and minimized the defects of their own people. It was partly a reaction against the undue depreciation of the Indians in the pages of British histories like those of Mill, and partly an effect of the growth of national consciousness and a desire for improvement in their political status. It is a noticeable fact that these defects gained momentum with the movement for political reforms, and later, in the course of the struggle for freedom.

An extreme example is furnished by K.P. Jayaswal. The repeated declarations of British historians that absolute despotism was the only form of Government in Ancient India provoked Indian historians, who, following the footsteps of Rhys Davids, emphasized the existence of republican and oligarchical forms of Government. This reaction was, generally speaking, kept within reasonable limits of historical truth; but Jayaswal carried the whole thing to ludicrous excess in his Hindu Polity, by his theory of a Parliamentary form of Government in Ancient India, which is a replica of the British Parliament including the formal Address from the Throne, etc.; and many other statements of the kind. Similarly, historical discussions on social and religious matters are not unoften coloured by the orthodox views on the subject. The recent acrimonious discussion on the killing of cows shows how even clearly established facts of history are twisted to suit present views. A truly scientific spirit of history is often sacrificed in discussions of such subjects as, ‘Did the Aryans come to India from outside?’, ‘Was there a caste system in the Ŗgveda?’, and conscious attempts are often made to explain away, ignore, or minimize, the harsh treatment accorded by the high caste Hindus to the lower castes, particularly Sũdras and Caṇḍālas.

Thomas William Rhys Davids

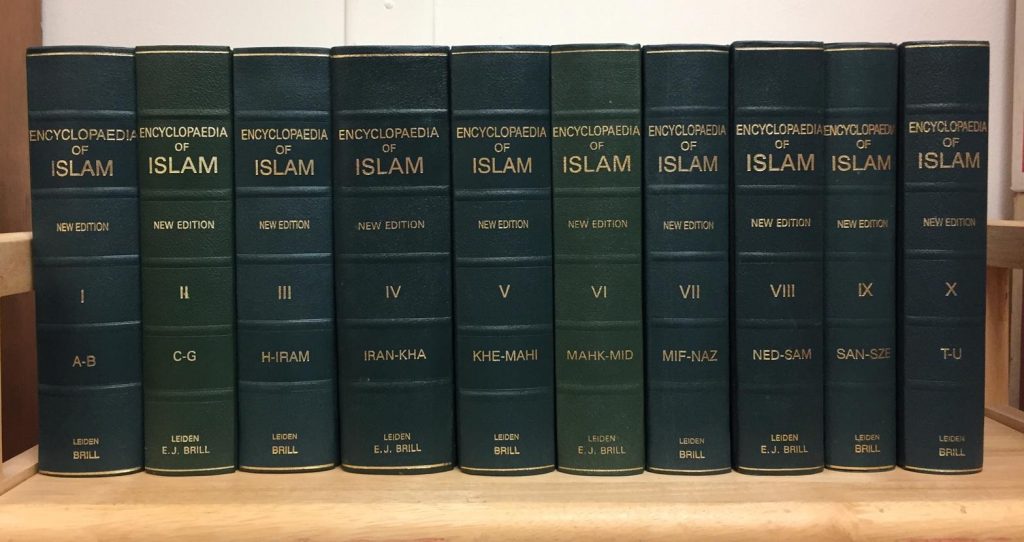

So far as Medieval India is concerned, there is a distinct and conscious attempt to rewrite the whole chapter of the bigotry and intolerance of the Muslim rulers towards Hindu religion. This was prompted by the political motive of bringing together the Hindus and Musalmans in a common fight against the British. A history written under the auspices of the Indian National Congress sought to repudiate the charge that the Muslim rulers ever broke any Hindu temple, and asserted that they were the most tolerant in matters of religion. Following in its footsteps a noted historian has sought to exonerate Mahmūd of Ghaznī’s bigotry and fanaticism, and several writers in India have come forward to defend Aurangzīb against Jadunath’s charge of religious intolerance. It is interesting to note that in the revised edition of the Encyclopaedia of Islam, one of them, while rewriting the article on Aurangzīb originally written by Sir William Irvine, has expressed the view that the charge of breaking Hindu temples brought against Aurangzīb is a disputed point. Alas for poor Jadunath Sarkar, who must have turned in his grave if he were buried. For after reading his History of Aurangzeb, one would be tempted to ask, if the temple-breaking policy of Aurangzīb is a disputed point, is there a single fact in the whole recorded history of mankind which may be taken as undisputed? A noted historian has sought to prove that ‘the Hindu population was better off under the Muslims than under the Hindu tributaries or independent rulers’. While some historians have sought to show that the Hindu and Muslim cultures were fundamentally different and formed two distinct and separate units flourishing side by side, the late K.M. Ashraf sought to prove that the Hindus and Muslims had no cultural conflict. But the climax was reached by the politician-cum-historian Lala Lajpat Rai when he asserted ‘that the Hindus and Muslims have coalesced into an Indian people very much in the same way as the Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Danes and Normans formed the English people of today’. His further assertion ‘that the Muslim rule in India was not a foreign rule’ has now become the oft-repeated slogan of a certain political party. The pity of the whole thing is that history books which do not incorporate these views are not likely to be prescribed as textbooks, and anyone who challenges these statements would be included in the black list of the Government of India.

Encyclopaedia of Islam

Lala Lajpat Rai

Coming to the British period, national sentiments prejudiced a calm consideration of several episodes. Two of these are, (1) the Black Hole Tragedy and character of Sirāju’d-daulah; and (2) the nature of the outbreak of 1857. Having myself written on both these topics I would not like to dwell on the merits of the different points of view. Reference has already been made above to other episodes where historians have been influenced by racial or national sentiments. To these may be added many questions concerning economic and administrative systems; in almost all of which the British and Indian views have been influenced more or less by national or patriotic feelings.

K. M. Ashraf

To this long array of defects of modern historiography in India, may be added another charge mostly levelled by Indians in recent times. It is said that the historians merely collect facts but do not make any generalizations or frame laws on their basis, while the real task of history is to reveal the spirit of humanity and trace the course of progress towards liberty. I do not think the charge is a legitimate one and would try to rebut it by the observations of some eminent scholars. The views of Fisher already quoted by me have been rebutted by other eminent historians like Acton who looks upon history as ‘the unfolding story of human freedom’. A.L. Rowse also refutes Fisher’s view and says: ‘No; there is no one rhythm or plot in history, but there are rhythms, plots, patterns, even repetitions. So that it is possible to make generalizations and to draw lessons.’ On the other hand, Sir Charles Oman in a way supports Fisher.

Left to Right: Acton, Fisher, A.L. Rowse, Sir Charles Oman

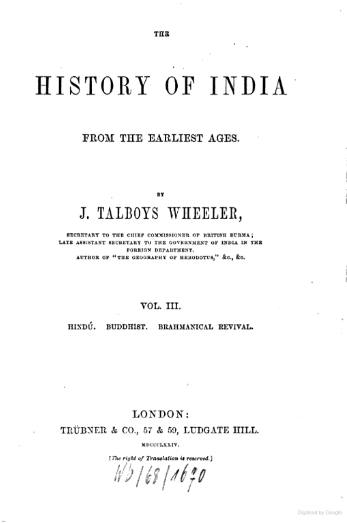

‘History’, says he, ‘is a series of interesting happenings, often illogical and cataclysmic, not a logical and orderly development from causes to inevitable results. In short, history is full of “might have beens”, and these sometimes deserve as much attention as the actual, but by no means necessary, course of events.’ But whatever view we may adopt in this matter so far as the history of Europe is concerned, our very inadequate knowledge of data in Indian history renders such generalizations a difficult and risky process. I fully share the views expressed by Sir Jadunath Sarkar in the course of his estimate of Sir William Irvine as a historian. He observes: ‘Some are inclined to deny Mr. Irvine the title of the Gibbon of India, on the ground that he wrote a mere narrative of events, without giving those reflections and generalizations that raise the Decline and Fall to the rank of a philosophical treatise and a classic in literature. But they forget that Indian historical studies are at present at a much more primitive stage than Roman history was when Gibbon began to write. We have yet to collect and edit our materials, and to construct the necessary foundation—the bed-rock of ascertained and unassailable facts—on which alone the superstructure of a philosophy of history can be raised by our happier successors. Premature philosophizing, based on unsifted facts and untrustworthy chronicles, will only yield a crop of wild theories and fanciful reconstructions of the past like those which J.T. Wheeler garnered in his now forgotten History of India, as the futile result of years of toil.’

J.T. Wheeler’s History Of India

Jadunath Sarkar

During the post-Independence period, certain new trends are noticeable among the Indian historians in addition to those noted above. Strangely enough, these were foreseen by the great Arab historian Ibn Khaldun. He includes, in a long list of defects of historians, ‘a very common desire to gain the favour of those of high rank, by praising them, by spreading their fame, by flattering them, by embellishing their doings and by interpreting in the most favourable way all their actions’. He then justly observes that all this gives a distorted version of historical events. This characteristic is a growing menace to historiography in Modern India. The evil is enhanced by the fact that the Government, directly or indirectly, seeks to utilize history to buttress some definite ideas, such as the Gandhian philosophy of non-violence, the artificial conception of fraternal relation between the two great communities of India sedulously propagated by him, and several popular slogans evoked by the exigencies of the struggle for freedom. These have been accepted as a rich legacy by the Government, even though it practically means in many cases the sacrifice of truth, the greatest legacy which Gandhi meant to bequeath to mankind.

Mahatma Gandhi

Thus the cult of non-violence is an ideal devoutly to be wished for, but when historians of India seriously maintain that this ideal has been followed throughout the course of Indian history, one rubs his eyes with wonder, for not only are all the known facts of Indian rulers against the assumption that they were averse to war, but war has been recommended by political texts as a normal practice and sanctioned by religion through the aśvamedha sacrifice and eulogy of digvijaya. The Court-poets flattered the patron king by giving him the proud epithet of ‘hero of hundred fights’.

Such distortion of history can never be excused even in the name of Mahatma Gandhi. Similar distortions have been made on other topics mentioned above. The net result has been that the oft-quoted phrase, ‘History is past politics’, is likely to be substituted soon by a new phrase, ‘History is present politics’. The attitude of the British Government towards Cunningham who dared include unpalatable truths in history, has not quitted India along with the British, and an Indian historian today is not always really free to write even true history if it is likely to offend the ruling party. I know from personal experience that any expression of views, not in consonance with the officially accepted view, is dubbed as anti-national, and is likely to provoke the wrath of the Government.

Kunwar Singh

No wonder that even eminent historians feel shy of, even if not prevented from, telling the whole truth. An apt illustration is furnished by the official history of the ‘Freedom Movement in Bihar’ (1957). Much has been said in it of Kunwar Singh as the local organizer and a hero of the great ‘War of Independence’ in 1857. But no mention has been made of a document which shows that the local sepoys, who had already mutinied, threatened to plunder his house and property if he did not join them. It can hardly be excused on the ground of ignorance, for it was the author of this history who first brought this document to light and published it in a local magazine. Some other documents of similar nature have also been withheld.

Bust of Arab historian Ibn Khaldun

When I was writing out the first draft of this lecture, the Proceedings of the Indian History Congress in 1964 and 1965 reached my hands. The Address of the General President in the 1964 session contains an elaborate presentation of the trends and concepts of history which appear to me to be a great departure from the ideals and concepts of history which I have outlined above. It may be reasonably assumed that these trends and concepts dominate at least a section of Indian historians today, and as such deserve careful scrutiny. ‘History,’ we are told, ‘has a mission and obligation to lead humanity to a higher ideal and nobler future. The historian cannot shirk this responsibility by hiding his head into the false dogma of objectivity, that his job is merely to chronicle the past. His task is to reveal the spirit of humanity and guide it towards self-expression.’ Some concrete steps are suggested for achieving this noble end. History must not call to memory ‘ghastly aberrations of human nature, of dastardly crimes, of divisions and conflicts, of degeneration and decay, but of the higher values of life, of traditions of culture and of the nobler deeds of sacrifice and devotion to the service of humanity’. In other words, history should record the spread of Buddhism by Aśoka, but not the horrors of the Kaliṅga war, carefully avoid all references to the devastation and massacre of Mahmūd of Ghaznĩ, destruction of temples by Aurangzīb, the Jallianwala Bagh massacre by General Dyer, the holocaust during communal riots, and so on. The reason for these omissions is that such things bring some ‘unhealthy trends which militate against the concept of national solidarity or international peace’. We are further told that ‘the purpose of history was to trace the course of progress towards liberty’. To crown all, it is declared that even ‘facts of Indian history and the Process of its march have to be judged by the criterion of progress towards liberty, morality and opportunities for self-expression’. So far as I understand, all these mark a definite departure from the accepted principles of historiography. As a concrete instance of the radical difference in the ideals of historiography which animates the post-Independence era in India, I may quote another passage from the Presidential Address: ‘The most important subject awaiting the critical touch of the historian, however, is the national movement, particularly the age dominated by Mahatma Gandhi, which restored the independence of the country. The historian has to get behind the external of the events and detect the spirit which animated them, and thereby reveal the soul of India. That approach alone will help to surmount the danger of provoking communal, regional, linguistic and class hatreds which unfortunately beset history writing.’

I must confess that in writing the ‘History of Freedom Movement’ I have not kept all this high ideal before me. I have preferred to follow the footsteps of Ranke, and may say in his words: ‘My book does not aspire to such lofty functions as are laid down in the Presidential address. Its aim is merely to show what actually occurred, with such comments as are obviously suggested by it.’

For a similar reason I demur to the principle that the purpose of history is to trace the course of progress towards liberty, and that even facts have to be arranged and judged by that criterion. The real purpose of history is to report correctly the progress of events, which did not in all cases mark the progress towards liberty. When all this is coupled with a definite instruction for avoiding mention of violent deeds, or even such facts as militate against the concept of national solidarity or international peace, we cannot but feel that Gandhian philosophy, which sought in vain to regenerate politics by infusing morality into it, has succeeded in inoculating history with his moral ideas. It may be a laudable project, but then, I would humbly suggest that history as a subject of study be omitted from our curriculum and replaced by books containing Gandhi’s philosophy and morality. The lack of knowledge of history may perhaps be made good by development of moral character.

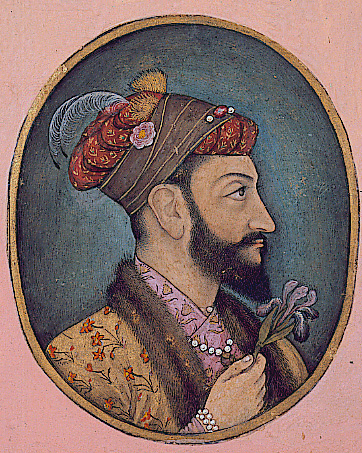

Aurangzeb, 1650

I would cite only one more example which gives a forecast of the shape that Indian history would take in the future. The President of Section II (Medieval India) of the Indian History Congress held at Allahabad in 1965 begins his address by pointing out the chief errors of Sir Henry Elliot and other Anglo-Indian writers of Medieval India. One of these is, to quote his own words, ‘the wholly impossible and erroneous conclusion that the Musalmans, as such, were a governing class, while the Hindus, as such, were the governed’. Another error is that ‘while pointing out the crimes of the medieval kings and their governing classes they quite overlooked what was happening at the same time in contemporary Europe’.

The President then refers to ‘India’s contact with Islam which had a deep impact on social, cultural, political and economic life of the country’. The net result of this is reflected in the following successive stages in the evolution of Medieval India. First, the Turkish State of the Ilbarites; second, the Indo-Muslim State of the Khaljī and the Tughlaqs, and third, the emergence of the Indian State of the Mughals. We are told that ‘Akbar’s political outlook was an outcome of the accumulated political wisdom of the generations that had gone by and was a logical development inherent in the very nature of the situation’. Unfortunately, nothing is said about his successors, particularly Aurangzīb, though it is claimed that on account of the continuity in this cultural evolution, the Mughal empire lasted longer than the whole of the Sultanate period.

Akbar with Lion and Calf, by Govardhan

There is hardly any doubt that the modern trends of Indian historiography noted above are inspired, or at least influenced to a large extent, by the attitude of the Government in deliberately seeking to utilize history for the spread of ideas which they have elevated to the rank of national policy to their own satisfaction. They are not willing to tolerate any history which mentions facts incompatible with their ideas of national integration and solidarity. They do not inquire whether the facts stated are true or the views expressed are reasonable deductions from facts, but condemn outright any historical writings which in their opinion are likely to go against their views about such things as Hindu-Muslim fraternity, the non-existence of separate Hindu and Muslim cultures on account of their fusion into one Indian culture, etc. I mention these particular instances, as I am in a position to substantiate them by documentary evidence, but reference may be made to many other illustrations, less susceptible to positive evidence. All these things are done in the name of national policy, which is at best the policy of a political party. But it violates the only national policy, which cannot be challenged by any party, namely ‘Truth shall prevail’, the motto engraved on our national emblem. This policy also underlies the most advanced ideal of historiography, as I have discussed above, and was expressed more than fifty years ago by the greatest historian of India, Sir Jadunath Sarkar, as chairman of a historical conference in Bengal. The following is a literal English translation of the original Bengali passage: ‘I would not care whether truth is pleasant or unpleasant, and in consonance with or opposed to current views. I would not mind in the least whether truth is or is not a blow to the glory of my country. If necessary, I shall bear in patience the ridicule and slander of friends and society for the sake of preaching truth. But still I shall seek truth, understand truth, and accept truth. This should be the firm resolve of a historian.’

Rajendra Prasad

Later, when Dr. Rajendra Prasad launched a scheme to write a comprehensive national history of India on a cooperative basis and requested Jadunath to become its chief editor, Jadunath wrote to him on 19 November 1937: ‘National history, like every other history worthy of the name and deserving to endure, must be true as regards the facts and reasonable in the interpretation of them. It will be national not in the sense that it will try to suppress or whitewash everything in our country’s past that is disgraceful, but because it will admit them and at the same time point out that there were other and nobler aspects in the stages of our nation’s evolution which offset the former. . . . In this task the historian must be a judge. He will not suppress any defect of the national character, but add to his portraiture those higher qualities which, taken together with the former, help to constitute the entire individual.’

In his reply to the above, dated 22 November 1937, Dr. Rajendra Prasad wrote: ‘I entirely agree with you that no history is worth the name which suppresses or distorts facts. A historian who purposely does so under the impression that he thereby does good to his native country really harms it in the end. Much more so in the case of a country like ours which has suffered much on account of its national defects, and which must know and understand them to be able to remedy them.’

Jadunath Sarkar

Contemporary History in the Soviet Mirror

I solemnly hope and pray that these words would be remembered by the present and future generations of Indian historians, for I see great dangers lurking ahead. I was reading recently a book entitled Contemporary History in the Soviet Mirror published in 1964. I was struck by many passages, a few of which I quote at random.

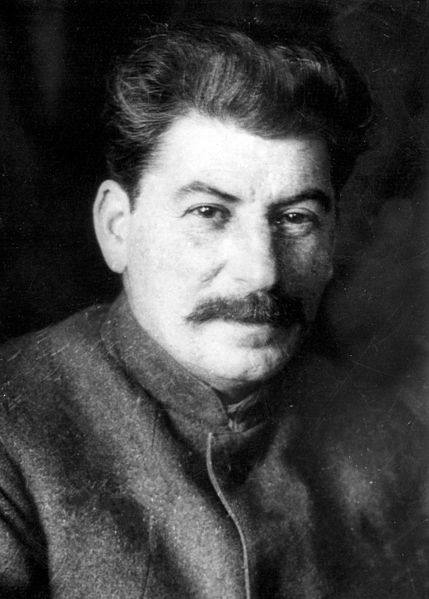

Stalin

‘The present official line in historiography is, if anything, even more militantly partisan than it was in Stalin’s day.’

‘The Soviet politicians have a narrow and utilitarian view of the functions of scholarship.’

‘Nothing could be more destructive of historical scholarship than the claim that the party is the repository of supreme wisdom. . . . In the Soviet Union today historians, like everyone else, are required to believe that, by some mysterious process unfathomable to an ordinary mortal, the party has been infallible.’

‘The partisan approach to history prevents the observer from recognizing the sanctity of objective facts and requires him, where necessary, to deny the evidence of his senses; for there are occasions when he must subordinate his own personal concept of truth to that held by an individual or group of individuals, namely the party.’

I hope it would be obvious to most people that these symptoms constitute dangerous impediments to the growth of true historiography. What is less obvious is that our country, dominated by party system, is rapidly moving towards the same tragic end.

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of Swapan Dasgupta. You can buy Awakening Bharat Mata: The Political beliefs of the Indian Right here.

Ramesh Chandra Majumdar is one of the major Indian historians of the past century. His work ranges from ancient Indian history (Corporate Life in Ancient India, 1919) to regional history (The History of Bengal, 1943) to Far Eastern and South-East Asian history (Ancient Indian Colonies in the Far East, 1927). Initially appointed by the government of India to helm a committee to write the history of the freedom struggle in India, he left after disagreements with the Education Ministry and published his own The Sepoy Mutiny and the Revolt of 1857. Later he published History of the Freedom Movement in India in three volumes. He also wrote An Advanced History of India (1960) and (as general editor and contributor) was behind the 11 volume series The History and Culture of the Indian People (1951-1977). He has many more works to his name. You can read more about him and his work here and here.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply