In the mainstream narratives of world history (dominated by western discourse), sea voyages undertaken by Europeans during the medieval centuries are considered to be one of the most crucial events in the past that changed the course of history. The implications of their obsession to ‘discover’ new trade routes were visible in age of renaissance and enlightenment when ‘new knowledge’ was produced. The age of discovery not only meant a new future for Europe, but also for the ‘newly discovered’ world that was subsequently colonised.

Did this mean that the people in the colonised world had no history of travel across the seas? The people of the Indian subcontinent, for one, were equipped enough with knowledge to answer this question by the late nineteenth century. What they really had to fight was not the orientalist mindset that mocked their inability to ‘discover’ new knowledge from across the world; but a peculiar taboo within their religion against overseas travel.

“This was especially true for upper-caste Hindus, but it was a concern for Muslim gentry as well. In both cases, travel overseas was seen as “denationalising” as it made it difficult to adhere to (or to prove that one had adhered to) rules about diet and personal conduct,” writes Rahul Sagar in his introduction to To Raise a Fallen People, an anthology of essays from the nineteenth century (three of which are reproduced below).

Over the nineteenth century, as more and more Hindus began crossing the seas, the debate over the issue of being discarded from the caste became acute. Should they be accepted back in the society upon their return? It needs to be remembered here that this was a period of social reform in India, and the debate between conservatives and reformists was gaining grounds on several issues, such as women’s education or her sexuality.

“The orthodox held travelers to be ‘irretrievably forfeiting caste and religion,’ while reformists pled that they were entitled to be reincorporated on pain of ‘penances.’” — Rahul Sagar

That this issue was painstakingly even more difficult for a woman can be guaged from a remarkable speech that Anandibai Joshi dared to give to a male audience at the College Hall in Srerampore in 1883, while defending her choice to go to America to study medicine.

“The knowledge of history as well as other places is not to be neglected. The present state of things is the consequence of the former, and it is natural to enquire what were the sources of the good that we enjoy or the evils we suffer. . . Here begins the true use of seeing other countries. We enlarge our comprehension by new ideas and perhaps recover some arts lost by us, or learn what is imperfectly known in our country.”

As to the threat of excommunication, Joshi added, she did not “fear it in the least,” because she would “make no change in my customs and manners, food or dress,” stressing that she intended to “go as a Hindu, and come back here to live here as a Hindu.” In the event, “why should I be cast out,” she asked, “when I have determined to live there exactly as I do here?”

It was unprecedented for a woman (even upper-caste women were afforded very little social mobility) to address such a gathering. Even more so, to travel abroad to become a doctor. Her path wasn’t easy. At only 9 years of age she was married to a man 17 years older than her.

Her husband, Gopalrao Joshi, enrolled her in a missionary school. Anandibai would later recall how she was jeered at, abused and even spat at by men while going to school in Bombay. Writes Kavitha Rao, “So obsessed was Gopalrao with Anandibai’s education that he would beat her if she attempted housework instead.”

In 1883, Anandibai moved to Pennsylvania to study at the historic Women’s Medical College from where she graduated in 1886, becoming modern India’s first female doctor. Unfortunately, Anandibai did not live long to carry her work forward, succumbing to tuberculosis only a year after her graduation and never being able to practise medicine, something for which she had strived so hard.

In Calcutta, Rahul Sagar tells us, the controversy led to the formation of a “Sea Voyage Movement” that declared itself “the tangible expression of a natural desire felt by the Hindu community to supplement its growing knowledge by travel in foreign countries, and to add to its resources by the expansion of its commerce.” Its leaders declared their intent to proceed along “orthodox lines” by seeking to “ascertain” from a range of eminent pandits (priests) “whether sea voyage and residence in foreign countries are permissible on the part of Hindus” so long as the requisite rules are followed. They left little doubt about what they expected to find, declaring, “The elasticity of the Hindu system is indeed its most remarkable characteristic. Its wonderful vitality is due to the readiness with which it recognises the pressure of external circumstances, and the ease with which it falls in with them.”

The committee appointed by the Sea Voyage Movement wrote to Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, seeking his views on whether the shastras permitted sea voyage. Interestingly, Chatterjee argued that “Sea-voyages are conformable to religion because they tend to the general good. Therefore, whatever the Dharma Sastras may say, sea-voyages are conformable to the Hindu religion.” According to him, what really mattered was whether individuals had “the necessary means” to undertake the journey— and when they did, tradition was simply ignored.

Read more about their views in the excerpts of their words reproduced below.

. . . Our subject to-day is, “My future visit to America, and public inquiries regarding it.” I am asked hundreds of questions about my going to America. I take this opportunity to answer some of them. . .

Anandibai Joshi

Why do I go to America? I go to America because I wish to study medicine. I now address the ladies present here, who will be the better judges of the importance of female medical assistance in India. I never consider this subject without being surprised that none of those societies so laudably established in India for the promotion of sciences and female education have ever thought of sending one of their female members into the most civilized parts of the world to procure thorough medical knowledge, in order to open here a College for the instruction of women in medicine. There is probably no country that would not disclose all her wants and try to stand on her own feet. The want of female doctors in India is keenly felt in every quarter. Ladies both European and Native are naturally averse to expose themselves in cases of emergency to treatment by doctors of the other sex. There are some female doctors in India from Europe and America, who, being foreigners and different in manners, customs and language, have not been of such use to our women as they might. As it is very natural that Hindu ladies who love their country and people should not feel at home with the natives of other countries, we Indian women absolutely derive no benefit from these foreign ladies. They indeed have the appearance of supplying our need, but the appearance is delusive. In my humble opinion there is a growing need for Hindu lady doctors in India, and I volunteer to qualify myself for one.

There is one College at Madras, and midwifery classes are opened in all the Presidencies; but the education imparted is defective and not sufficient, as the instructors who teach the classes are conservative, and to some extent jealous. I do not find fault with them. That is the characteristic of the male sex.

Are there no means to study in India? No. I do not mean to say there are no means, but the difficulties are many and great. There is one College at Madras, and midwifery classes are opened in all the Presidencies; but the education imparted is defective and not sufficient, as the instructors who teach the classes are conservative, and to some extent jealous. I do not find fault with them. That is the characteristic of the male sex. We must put up with this inconvenience until we have a class of educated ladies to relieve these men.

I am neither a Christian nor a Brahmo. To continue to live as a Hindu and to go to school in any part of India is very difficult. A convert who wears an English dress is not so much stared at. Native Christian ladies are free from the opposition or public scandal which Hindu ladies like myself have to meet within and without the zenana. If I go alone by train or in the street some people come near to stare and ask impertinent questions to annoy me. Example is better than precept. Some few years ago, when I was in Bombay, I used to go to school. When people saw me going with my books in my hands, they had the goodness to put their heads out of the window just to have a look at me. Some stopped their carriages for the purpose. Others walking in the streets stood laughing and crying out so that I could hear:—

“What is this? Who is this lady who is going to school with boots and stockings on?”

“Does not this show that the Kali Yuga has stamped its character on the minds of the people?”

Ladies and gentlemen, you can easily imagine what effect questions like these would have on your minds if you had been in my place!

Once it so happened that I was obliged to stay in school for some time, and go twice a day for my meals to the house of a relation. Passers-by, whenever they saw me going, gathered round me. Some of them made fun, and were convulsed with laughter. Others, sitting respectably in their verandahs, made ridiculous remarks, and did not feel ashamed to throw pebbles at me. The shopkeepers and venders spit at the sight of me, and made gestures too indecent to describe. I leave it to you to imagine what was my condition at such a time, and how I could gladly have burst through the crowd to make my home nearer!

If I go to take a walk on the Strand, Englishmen are not so bold as to look at me. Even the soldiers are never troublesome; but the Babus lay bare their levity by making fun of everything. “Who are you?” “What caste do you belong to?” “Whence do you come,” “Where do you go?” are, in my opinion, questions that should not be asked by strangers.

Yet the boldness of my Bengali brethren cannot be exceeded, and it is still more serious to contemplate than the instances I have given from Bombay. Surely it deserves pity! If I go to take a walk on the Strand, Englishmen are not so bold as to look at me. Even the soldiers are never troublesome; but the Babus lay bare their levity by making fun of everything. “Who are you?” “What caste do you belong to?” “Whence do you come,” “Where do you go?” are, in my opinion, questions that should not be asked by strangers. There are some educated native Christians here in Serampore who are suspicious; they are still wondering whether I am married or a widow; a woman of bad character or ex-communicated! Dear audience, does it become my native and Christian brethren to be so uncharitable? Certainly not. I place these unpleasant things before you, that those whom they concern most may rectify them, and those who have never thought of the difficulties may see that I am not going to America through any whim or caprice.

Anandibai Joshee graduated from Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP) in 1886. Seen here with Kei Okami (center) and Sabat Islambooly (right). All three completed their medical studies and each of them was among the first women from their respective countries to obtain a degree in Western medicine.

Why do I go alone? It was at first the intention of my husband and myself to go together, but we were forced to abandon this thought. We have not sufficient funds; but that is not the only reason. There are others still more important and convincing. My husband has his aged parents and younger brothers and sisters to support. You will see that his departure would throw those dependent upon him into the arena of life, penniless and alone. How cruel and inhuman it would be for him to take care of one soul and reduce so many to starvation! Therefore I go alone.

Shall I not be excommunicated when I return to India? Do you think I should be filled with consternation at this threat? I do not fear it in the least. Why should I be cast out, when I have determined to live there exactly as I do here? I propose to myself to make no change in my customs and manners, food or dress. I will go as a Hindu, and come back here to live here as a Hindu. I will not increase my wants, but be as plain and simple as my forefathers, and as I am now. If my countrymen wish to excommunicate me, why do they not do it now? They are at liberty to do so. I have come to Bengal and to a place where there is not a single Maharashtrian. Nobody here knows whether I behave according to my customs and manners, or not. Let us therefore cease to consider what may never happen, and what, when it may happen, will defy human speculation.

Shall I not be excommunicated when I return to India? Do you think I should be filled with consternation at this threat? I do not fear it in the least. Why should I be cast out, when I have determined to live there exactly as I do here? I propose to myself to make no change in my customs and manners, food or dress. I will go as a Hindu, and come back here to live here as a Hindu.

What will I do if misfortune befall me? Some persons fall into the error of exaggerated declamation, by producing in their talk examples of national calamities and scenes of extensive misery which are found in books rather than in the world, and which, as they are horrid, are ordained to be rare. A man or a woman who wishes to act does not look at that dark side which others easily foresee. On necessary and inevitable evils which crush him or her to dust, all dispute is vain. When they happen they must be endured, but it is evident they are oftener dreaded than experienced. Whether perpetual happiness can be obtained in any way, this world will never give us an opportunity to decide. But this we may say, we do not always find visible happiness in proportion to visible means. It is not a thing which may be divided among a certain number of men. It depends upon feeling. If death be only miserable, why should some rejoice at it, while others lament? On the other hand, death and misery come alike to good and bad, virtuous and vicious, rich and poor, travelers and housekeepers; all are confounded in the misery of famine and not greatly distinguished in the fury of faction. No man is able to prevent any catastrophe. Misery and death are always near, and should be expected. When the result of any hazardous work is good, we praise the enterprise which undertook it; when it is evil, we blame the imprudence. The world is always ready to call enterprise imprudence when fortune changes.

Some say that those who stay at home are happy, but where does their happiness lie? Happiness is not a readymade thing to be enjoyed because one desires it. Some minds are so fond of variety that pleasure if permanent would be insupportable, and they solicit happiness by courting distress. To go to foreign countries is not bad, but in some respects better than to stay in one place. [The knowledge of history as well as other places is not to be neglected. The present state of things is the consequence of the former, and it is natural to enquire what were the sources of the good that we enjoy or the evils we suffer. To neglect the study of sciences is not prudent; it is not just if we are entrusted with the care of others. Ignorance when voluntary is criminal, and one may perfectly be charged with evils who refused to learn how he might prevent it. When the eyes and imagination are struck with any uncommon work, the next transition of an active mind is to the means by which it was performed. Here begins the true use of seeing other countries. We enlarge our comprehension by new ideas and perhaps recover some arts lost by us, or learn what is imperfectly known in our country. So I hope my going to America will not be disadvantageous.]

[I have seriously considered our manners and future prospects and find that we have mistaken our interests.] Everyone must do what he thinks right. Every man has owed much to others. His effort ought to be to repay what he has received. [This world is like a vast sea, mankind like a vessel sailing on its tempestuous bosom. Our prudence is its sails; the sciences serve us for oars; good or bad fortunes are the favorable or contrary winds and judgement is the rudder; without this last the vessel is tossed by every billow and will find ship-wreck in every breeze.] Let us follow the advice of Goldsmith who says: “Learn to pursue virtue of a man who is blind, who never takes a step without first examining the ground with his staff.” I take my Almighty Father for my staff, who will examine the path before He leads me further. I can find no better staff than He.

I ask my Christian friends, “Do you think you would have been saved from your sins, if Jesus Christ, according to your notions, had not sacrificed his life for you all?” Did he shrink at the extreme penalty that he bore while doing good? No, I am sure you will never admit that he shrank! Neither did our ancient kings Shibi and Mayurdhwaj. To desist from duty because we fear failure or suffering is not just. We must try. Never mind whether we are victors or victims. Manu has divided people into three classes.

And last you ask me, why I should do what is not done by any of my sex? [To this I cannot but say that we are bound by the rights of society to the labours of individuals. Everyone has his duty and he must perform it in the best way he can; otherwise his fear and backwardness are supposed to be a desertion of duty. It is very difficult to decide the duties of individuals. It is enough that the good of the whole is the same with the good of an individual. If anything seems best for mankind, it must evidently be best for an individual and that duty is to try one’s best, according to his sentiments to do good to the society.] According to Manu, the desertion of duty is an unpardonable sin. So I am surprised to hear that I should not do this, because it has not been done by others. [I cannot help asking them in return “who should stand the first if all will say so?”] Our ancestors whose names have become immortal had no such notions in their heads. I ask my Christian friends, “Do you think you would have been saved from your sins, if Jesus Christ, according to your notions, had not sacrificed his life for you all?” Did he shrink at the extreme penalty that he bore while doing good? No, I am sure you will never admit that he shrank! Neither did our ancient kings Shibi and Mayurdhwaj. To desist from duty because we fear failure or suffering is not just. We must try. Never mind whether we are victors or victims. Manu has divided people into three classes. [Those who do not begin for fear of failure, are reckoned among the meanest; those who begin but give it up through obstacles belong to the middle class; and those who begin but [do] not give it up till they attain success, through repeated difficulties, are the best. Let us not therefore be guilty of the very crime we absolutely hate. The more the difficulties, the greater must be the attempt. Let it be our boast never to desist from anything begun. Sufferance should be our badge.]

— Standing Committee on the Hindu Sea-Voyage Question

. . . Hindoo young men, in appreciable numbers, proceed to England to receive education in the universities, to qualify for the Bar, to compete for the Indian Civil Service, for the Medical Service, and in various other ways to equip themselves for the practical work of life. The number is on the increase, of gentlemen, who, if all restrictions were removed, would like to proceed to Europe for purposes of travel, and all the pleasures and profits it brings. There is a growing desire also in some quarters to make excursions to the West for commercial purposes. It cannot be a matter of indifference to the Hindoo community if the gentlemen who come back from Europe after perfecting their education and enlarging their experience are to be received back into society or excluded from it. It cannot be a matter of indifference also whether adventurous gentlemen should have free scope given to them in the matter of travel, or they should have their ambition curbed by social restrictions. The welfare of a country is the welfare of its individuals, and no subject can be of greater national importance than the discussion of the limits which custom may have prescribed to the liberty of movement of the men who compose the nation.

On economic grounds alone the question of sea-voyages is of great practical importance. People may feel themselves driven by sheer necessity to try their fortune in remote countries, to seek new careers, learn the arts of foreign nations, and come back home with added qualification and augmented resources. If these poor, adventurous souls should be denied the opportunities they sought, it is not they alone that would be sufferers, but the country as well. Social restrictions, however, are likely to prove an effectual barrier to most of them, and the legitimacy of those restrictions therefore deserves serious consideration. The possibility of natives of India marching out in quest of occupation to distant lands may now appear to be too remote, and as a dream. But there are reasons to believe that if the restrictions were repealed or relaxed, opportunities of adventure would often be utilized.

Hindoo society is governed by rules which have their basis in the Hindoo religion. That religion is enshrined in the shastras, of which the recognised, authoritative interpreters are the Pandits. The Pandits give their vyavasthas or ordinances founded upon the texts. These are accepted by the leaders of the different castes which make up society, and they thus come to regulate usage. On the subject of sea-voyage, therefore, the first thing necessary was to obtain the opinions of the Pandits. That step has already been taken. It was not of course to be expected that the opinion of every single Pandit in Bengal should be obtained, but many of the leading Pandits have been consulted. . . . The next step that was taken was to refer the subject to some of the leading members of Hindoo society, all of the higher castes, and their opinions have also been recorded. Attention may be specially called to the opinion of so distinguished an apostle of Hinduism as Bankim Chandra Chatterjee. Lastly, a large body of public opinion from various sources, which had been elicited by the discussion, has been set forth in its proper place. It includes the opinions as well of eminent Englishmen as of newspapers, Hindoo and English. These opinions have a value which must not be overlooked. Pandits interpret the shastras; social leaders judge practicability; but an intelligent public have also a right to be heard, for, unfettered by considerations of authority and custom, they are able to utter the voice of abstract reason. Mere reasonableness is not an excuse for an innovation, but it will hardly be denied that a practice which is manifestly contrary to reason cannot long remain unmodified, and that so long as it does exist it will work mischief. The opinions, therefore, of intelligent and educated men who are even outsiders to our society have an importance that should not be underrated. . . .

For a full appreciation of the issues involved in the sea-voyage question it is necessary to bear in mind a few well-known facts which may be thus stated:

What is the inference to be drawn from these facts? Obviously this, that it would not be fair or consistent to exclude from society men who had made only a voyage by sea without transgressing Hindoo rules of living. Surely it cannot be contended that a mere crossing of the sea is a grosser offence than living in a non-Hindu style, or even as gross as that. When open, or, at any rate, well-known violations of Hindoo rules of eating and drinking are connived at and excused, neither reason nor orthodoxy demands the exclusion of men who living as Hindoos had merely travelled to the West. . . That a voyage by sea as such, does not militate against Hinduism seems to be tacitly admitted by Hindoo society by the manner in which it has been treating Swami Vivekananda’s visit to America. The Swami, so far from being regarded as an apostate by reason of his visit, is being looked up to as a prince of Hindoos and the pride of Hinduism. It is inconceivable, therefore, that the sea-voyage movement should be opposed on grounds either of religion or logic. If there could be any objection to it, it would be its conservative rather than its revolutionary character. . .

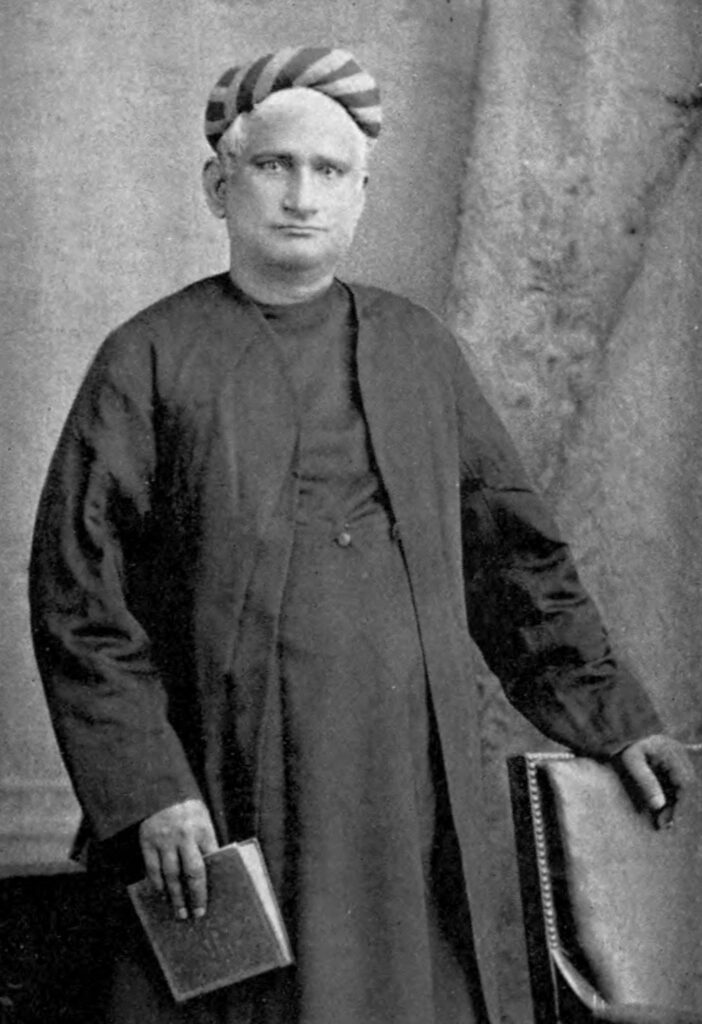

— Bankim Chandra Chatterjee

. . . The questions which you wish me to answer are such as are best answered by professors of the Dharma Sastras. I do not profess the Dharma Sastras, nor am I prepared to undertake the office of expounding them. But I have no objection to offer a few observations regarding the present agitation about sea-voyages by Hindus.

Bankim Chattapadhyay

In the first place, I do not believe that it is either possible or desirable to promote social reforms by invoking the authority of the Sastras. I had to object on the same ground to the late lamented Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar’s proposals to suppress polygamy with the aid of the Sastras; and I have seen no ground since then to change my opinion. This opinion I hold on two grounds. The first is, that Bengali society is governed not by the Sastras but by custom. It is true, that very often custom follows the Sastras; but as often again custom conflicts with the Sastras. When there is such a conflict custom carries the day.

You seek to collect the behests of the Sastras, regarding sea-voyages, and to induce society to follow them;—are you prepared to induce society to be guided by the Sastras on all other matters as well? One of the precepts of the Dharma Sastras is, that it is the duty of the Shudras to perform menial offices for the Brahmins and other superior castes;—do the Shudras of Bengal follow the precept?

The second reason for my opinion is that if society were everywhere governed by the Sastras, it is doubtful whether the result will be social welfare. You seek to collect the behests of the Sastras, regarding sea-voyages, and to induce society to follow them;—are you prepared to induce society to be guided by the Sastras on all other matters as well? One of the precepts of the Dharma Sastras is, that it is the duty of the Shudras to perform menial offices for the Brahmins and other superior castes;—do the Shudras of Bengal follow the precept? The Sastras are not a guide here. Are any of you prepared to enforce this precept? Do you think that any endeavours to enforce it will succeed? Will a Sudra Judge of the High Court leave the bench, or will the prosperous Shudra zamindar leave the zamindar’s seat, to respectfully tend the feet of the Brahmin manufacturer of eatables? By no means. Bengali society obeys a portion of the Dharma Sastras according to its necessities. The rest it has cast off because of its necessities. The same feeling of necessity may induce it to cast off what still remains. What good then there is in seeking to ascertain the commands of the Dharma Sastras?

My own conviction is that it is impossible to carry out social reformation regarding any particular practice merely on the strength of the Sastras without religious and moral regeneration along the whole line. This I have tried to explain at length in my work on Krishna Charitra. I have already stated that society here is governed by custom, not by the Sastras. Reforms in custom can be achieved only when there is an advance in religion and morals along the whole line. The present agitation is the outcome of the advance that has already taken place. As society advances gradually in religion and morals, the objections against sea-voyages will disappear, or if any opposition should still continue to exist, it would be powerless. But so long as the full measure of advance is not attained, so long it will be impossible to make sea-voyages acceptable to society.

But it has also to be observed that none of us are aware of the exact measure of opposition which exists in Bengali society towards sea-voyages. I see that whoever commands the necessary means and is otherwise favorably circumstanced, does proceed to Europe when willing to do so. I have not come across a single instance in which the journey to Europe was abandoned out of respect to the authority of the Sastras. But I am also bound to admit that most of those who return from Europe remain outside the pale of Hindu society. It is a question whether the fault lies with them, or with Hindu society. On their return to this country they voluntarily keep away from Bengali society by adopting European habits and customs. They separate themselves from us by adopting foreign costumes, foreign habits of living, and foreign usages. Those who on their return from Europe did not adopt this course have in many instances been re-admitted into Hindu society. If gentlemen returning from Europe did generally resume habits and usages conformable to Hindu society, it is impossible to say that they would be as a body left outside its precincts.

I have not come across a single instance in which the journey to Europe was abandoned out of respect to the authority of the Sastras. But I am also bound to admit that most of those who return from Europe remain outside the pale of Hindu society. It is a question whether the fault lies with them, or with Hindu society.

Lastly, I have to point out that before deciding the question as to whether sea-voyages are in conformity to the Dharma Sastras of the Hindus, it is necessary to decide whether it is not in conformity to Dharma (religion) itself. Must we reject that which is conformable to religion but opposed to the Dharma Sastras, merely because it is opposed to the Dharma Sastras? Many will say that alone which is conformable to the Hindu Dharma Sastras is religion; and that which is not conformable to them is irreligion. I am not prepared to admit this. None of the older sacred books of Hindus say so. Krishna in the Mahabharata says— “Dharma is so called because it holds all. Know that for certain to be Dharma, which contributes to the general welfare.” If the Mahabharata is not guilty of a falsehood, if he whom the Hindus worship as the Divine Incarnation is not guilty of falsehood, then that which is for the general welfare is religious. Now, are sea-voyages for the general welfare or not? If they are, why should they be opposed because they do not happen to be encouraged by the Smritis? . . . Sea-voyages are conformable to religion because they tend to the general good. Therefore, whatever the Dharma Sastras may say, sea-voyages are conformable to the Hindu religion.

These excerpts have been carried courtesy the permission of Rahul Sagar and Juggernaut. You can buy To Raise a Fallen People, here.

Dr. Anandibai Gopalrao Joshi was the first Indian female doctor of western medicine. She was the first woman from the erstwhile Bombay presidency of India to study and graduate with a two-year degree in western medicine in the United States.

Bankim Chandra Chatterjee (also Chattopadhayay) was an Indian novelist, poet, Essayist and journalist. He was the author of the 1882 Bengali language novel Anandamath, which is one of the landmarks of modern Bengali and Indian literature. He was the composer of Vande Mataram, written in highly sanskritized Bengali, personifying Bengal as a mother goddess and inspiring activists during the Indian Independence Movement.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply