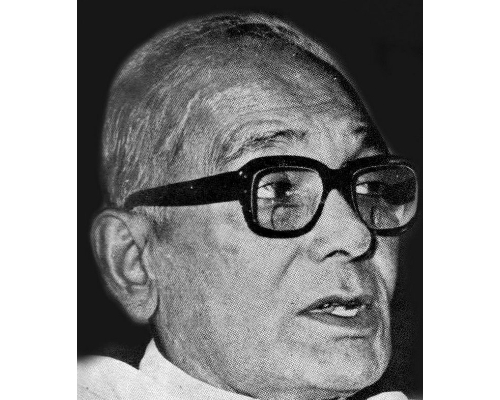

Madhukar Dattatreya Deoras, popularly known as ‘Balasaheb,’ was the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh’s third sarsanghchalak (i.e. head). He followed in the footsteps of KB Hedgewar and MS Golwalkar, but is not as known and spoken about as his predecessors, despite his long tenure of twenty years. The lack of work on Deoras is a particularly noticeable gap in scholarship on Hindu nationalism and the spread of the ideology of Hindutva, because he played a major role in bringing the RSS into the mainstream.

A crucial work filling this lacunae is Prof. Pralay Kanungo’s in-depth analysis of Deoras’ reign, from his book RSS’s Tryst with Politics: From Hedgewar to Sudarshan. In an extremely lucid and clear analysis, he traverses many phases in the organisation’s recent history – the alliance with Jayaprakash Narayan, the ban during the Emergency, the Janata Party experiment, the establishment of the BJP and, arguably the most important, the Ram Janmabhoomi movement.

The RSS was founded in 1925 by KB Hedgewar in Nagpur. Since its inception, it maintains that it is merely a “cultural organisation”. Kanungo, through the course of his work, emphasises that this claim does not stand up against scrutiny: “The evolution of the RSS, its organisational structure and functions, the ideology of the Hindu Rashtra and its homogenising agenda unveil its political mission.” However, Kanungo observes that, despite its political orientation, it is true that the RSS has, for a long portion of its history, kept away from active politics. It has a large network of affiliates, such as the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), who participate in its stead.

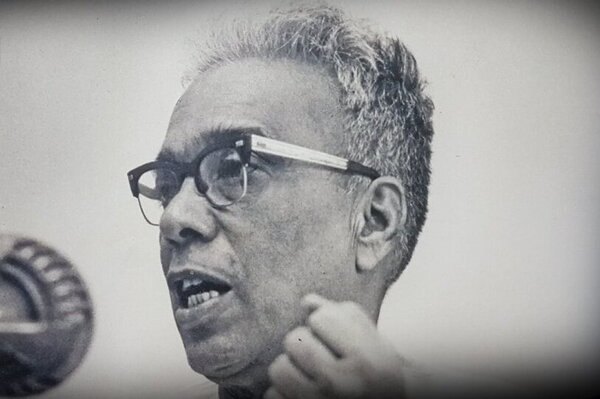

Kanungo traces this back to a time prior to the BJP’s establishment in 1980, when the political affiliate of the RSS was the Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS). The latter came into being in 1951 and contested elections right from its inception. However, until the late 1960s, it was unable to garner any significant support from the Indian populace. This can be partially attributed to the Congress’ hegemonic position as the single largest and most popular party during this period.

The tide began to change around the time Deoras assumed the reigns of the RSS. Jawaharlal Nehru – and subsequently, Lal Bahadur Shastri – had passed away and created a vacuum which the leadership hoped to fill with the as-yet unproven Indira Gandhi. Kanungo writes that the “Congress system seemed to have exhausted its potential and was losing its political hegemony by the early 1970s”. At the same time, despite attempts by erstwhile Congress leaders as well as other parties, there seemed to be no political force in the country which could pose as an alternative to Mrs. Gandhi.

Deoras, reading the writing on the wall, “thought it ideal for the RSS to enter the political fray with its alternative national agenda”. Though he only became the chief of the Sangh in 1973, Deoras was by no means a new face. He had been a part of the organisation since the age of twelve and had established himself as a favourite of both Hedgewar and Golwalkar. As Kanungo puts it, “Deoras was thus rightly described as a true child of the organisation.”

Considered “a man of organisation and pragmatic orientation”, one of the first actions Deoras undertook after assuming his position was to bring about changes in the organisational set-up of the RSS so as to make it more “capable of political action”. Further, he also began setting up other important affiliates besides the Bharatiya Jana Sangh as he understood that, despite an increase in its seats, the BJS’s performance had not been up to the mark. Under his aegis, the ABVP and the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS) expanded their bases amongst students and workers respectively.

This policy paid a huge dividend in the 1970s. In keeping with his pragmatic approach, Deoras did not shy away from making political compromises if and when these were required. Thus not only was the RSS, through its affiliates, able to capitalise on the anti-Indira sentiment in the early 1970s, it was also able to garner the support of the staunch Gandhian Jayaprakash Narayan, who led the nation-wide agitation against the Congress Prime Minister.

JP’s support was instrumental in bringing the RSS into mainstream public view, and that too in a positive light. The organisation had not been fully accepted by all sections of Indian society and it had been unable to shrug off the “the old stigma of ‘Mahatma Gandhi’s murderer’”. It was only with Narayan’s support that this charge could be “considerably blunted”.

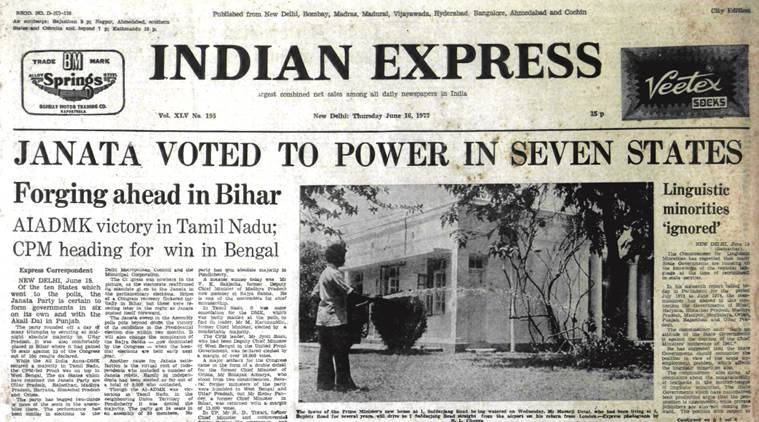

The movement was clearly strong enough to threaten Mrs. Gandhi and, soon after in 1975, she declared an Emergency which lasted till 1977. In these two years, the RSS was banned and many of its leaders, including Deoras, arrested. When the Emergency was lifted, all major Opposition parties came together under the banner of the ‘Janata Party’. The coalition had members from all ends of the political spectrum: from the Communists to the Jana Sangh.

In order to establish stability within the Janata Party, the RSS adopted a “politics of accommodation and ideological flexibility”. When other Janata Party constituents began to question its communal orientation, the organisation “announced the opening of its doors to non-Hindus”. However, the coalition could not sustain. It collapsed due to internal friction and Chaudhary Charan Singh became the next Prime Minister in 1979.

The Sangh had never before possessed such an influence on government and this brief stint gave it “the opportunity to acquire an all-India status”. Kanungo writes: “The RSS got a lot of publicity, its organisation and affiliates became known throughout the country and its leadership acquired a national stature and respect.” However, there was another point of view within the organisation, backed by traditionalists who were “disillusioned with the evil effects of power politics” and this gave birth to a dilemma for the Sangh to resolve urgently.

Perhaps in response to this very dilemma, the BJP was formed in a convention held by the Jana Sangh group of the Janata Party, on the 5th of April, 1980. The new party “tried for a synthesis of ideology and realpolitik”: it retained and continued certain traditions, particularly symbols, of the Janata Party while “in terms of the leadership structure and recruitment patterns, the BJP continued with its Jana Sangh and RSS heritage”. The new party “appointed RSS men in key position” while at the same time “co-opting a few leaders from a non-RSS and non-Jana Sangh background”. In terms of ideology, it retained Deendayal Upadhyay’s ‘Integral Humanism’ while adopting ‘Gandhian Socialism’ in its statement of first principles.

Simultaneously, Deoras continued to expand the reach of the RSS and its affiliates. He was a proponent of Golwalkar’s Hindu Rashtra; for him, too, the “problem of Hindustan” was not the “Muslim” or the “Christian”, but the “disunity among the Hindus”. And so, his tenure saw the revival of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), which had been “lying low” for decades.

The trigger for this was the mass conversion of 1500 Dalits to Islam in Tamil Nadu. In response, the VHP raised the call of “Hinduism in Danger!” and called on all Hindus to unite against this threat. It went on to organise massive events and evolved a potent political mode: “tirth yatras“. Ostensibly only religious events, these pilgrimages became vehicles of mobilization for the RSS and “religious symbols” and “ritual paraphernalia” were used to “create a community consciousness among Hindus”. The evolution of the yatra as a political tool, however, must also be seen in the context of Indira Gandhi’s usage of Hindu rhetoric and ritual for political messaging, a strategic shift in Congress messaging in the early eighties, that was leading it to electoral victory in erstwhile BJP strongholds. Eventually, after the BJP’s electoral rout in 1984, with most of its “upper-caste support” going to Rajiv Gandhi’s Congress, the Bharatiya Janata Party reverted to its “ultra-Hindu posture”. Kanungo writes: “Deendayal’s ‘Integral Humanism’ replaced ‘Gandhian Socialism’ as the basic philosophy of the party in October 1985.”

This politics of mobilisation culminated in the Ram Janmabhoomi movement. Seeing the effectiveness of the yatras, Deoras was on the look-out for a “powerful and popular Hindu symbol” and he found his answer in “Lord Ram”. As early as 1984, the VHP had announced its intention of “liberating” the birthplace of Rama at Ayodhya.

In a few years, this nascent movement got a great opportunity when the Babri Masjid was thrown open on 1st February 1986. Simultaneously, the Shah Bano case and the subsequent Muslim Women’s Bill gave the Sangh Parivar a great opportunity to sharpen its anti-Muslim rhetoric. With these twin tools and a well-oiled, rapidly growing organisation, Deoras went on the offensive.

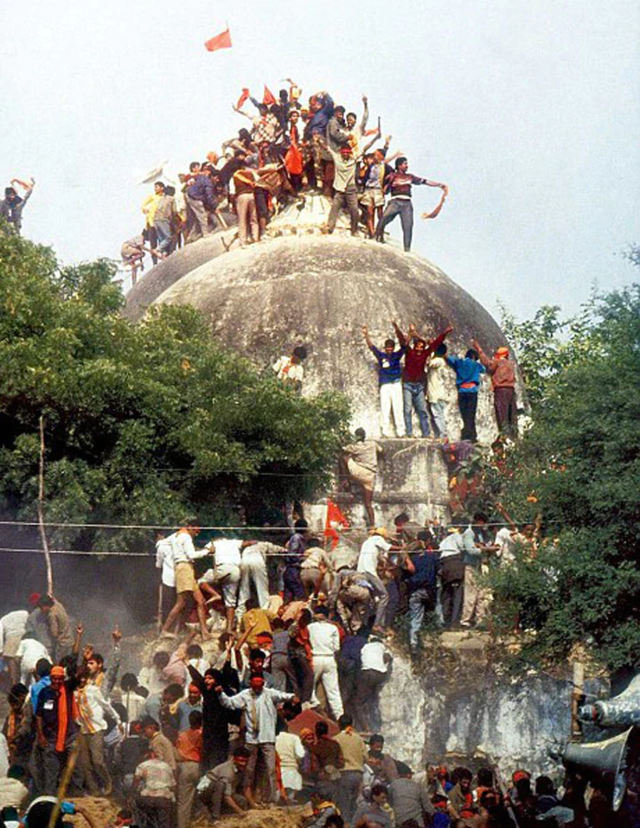

In the last years of the 1980s and early 1990s, the Ram Janmabhoomi movement swept through the nation. The mobilisation, along with multiple rath yatras, brought the BJP great electoral dividends in the 1991 General Elections— it was now a national party in all senses of the term. It also came into power in multiple states, including Uttar Pradesh. With a BJP Chief Minister active in the state, the RSS and its affiliates stepped up the movement and the Babri Masjid was demolished in 1992. Kanungo writes: “On 16 December 1992, 300,000 kar sevaks assembled at Ayodhya and thronged the domes of the Babri Masjid. Within five hours the mosque was razed to the ground and a new make-shift Ram temple was constructed amid the rubble of the disputed structure. It was a smooth operation. The Sangh Parivar celebrated the event as a historic victory.”

A measure of the RSS’s influence at this stage is indicated by the toothlessness of the Narasimha Rao-led Congress government at the Centre, despite the massive communal violence that the Sangh Parivar’s actions led to.

“Unlike the previous bans of the RSS in 1948 and 1975,” writes Kanungo. “This time the government adopted a conciliatory rather than a firm attitude towards the RSS. Only a relatively small number of people were taken into custody under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. Key cadres had gone into hiding. Even this crackdown was soon relaxed and the seven leaders were freed on 10 January 1993. The government’s policy was further constrained by certain judicial decisions. The Madhya Pradesh High Court ordered in the end of December that the RSS offices in Jabalpur and Indore be opened. On 22 April 1993, it overturned the imposition of President’s rule in the state and ordered the restoration of the legislative assembly in Madhya Pradesh.”

Kanungo writes of the immediate aftermath of the demolition:

“The Ayodhya demolition was carefully planned by the Sangh Parivar and was facilitated by the UP government headed by Kalyan Singh. According to the ‘Citizens’ Tribunal on Ayodhya’ the demolition was pre-planned and finalized at a meeting held on 5 December 1992 and attended by HV Sesdhadri, KS Sudarshan, LK Advani, MM Joshi, Vijaya Raje Scindia, Ashok Singhal, Vinay Katiyar, Uma Bharti, Sadhvi Ritambhara, Acharya Dharmendra, Pramod Mahajan, BL Sharma and Champat Roy, apart from Moreshwar Save of the Shiv Sena. However, the RSS does not admit so. Seshadri argued that the demolition was not a part of the plan on that day and they could not gauge the intensity of the feelings of the kar sevaks. Unexpectedly they broke the human chain of the swayamsevaks guarding the place. Deoras attributed the demolition to outside elements. BJP’s White Paper on Ayodhya claims that the demolition was ‘an uncontrolled and, in fact uncontrollable upsurge of spontaneous nature.’”

The stage was therefore set for the BJP – and by extension the RSS – to assume a major role in politics as the primary alternative to the Congress. The journey was not linear, however. The party suffered a set-back in the UP, MP and Himachal Pradesh assembly elections of 1993. “These elections,” Kanungo writes. “Were widely regarded as a referendum on the demolition.”

However, the party’s fortunes would turn soon. Though Deoras stepped down as sarsanghchalak in 1994, owing to ill-health, and passed away on 17th June 1996, he was able to see the fruits of his labour when BJP leader Atal Behari Vajpayee became the Prime Minister of India one month before his death. “The Ram Janmabhoomi movement and the Rath Yatra reversed the political future of the BJP, from a marginal political party to the national alternative,” writes Kanungo. “The RSS, its ideological mentor and organisational master, no longer remained peripheral; it had now come to occupy the centrestage of Indian politics as an indispensable player.”

(Quotes, where unattributed, are from Pralay Kanungo’s RSS’s Tryst with Politics: From Hedgewar to Sudarshan)

The evolution of the RSS, its organisational structure and functions, the ideology of the Hindu Rashtra and its homogenising agenda unveil its political mission despite the insistence that it is merely a cultural organisation. This chapter seeks to contest this ‘cultural claim’ further by explaining the emergence of the RSS as an important political actor on the Indian political scene, particularly under the leadership of Balasaheb Deoras. Responding to the changing dynamics of Indian politics the RSS has changed the course of its political journey –– from moderate, pragmatic, and accommodative to militant, rigid and intolerant. It also examines how the RSS promoted its political mobilisation during the Ram Janmabhoomi agitation through an innovative use of Hindu cultural and religious symbols, thereby wrapping its political agence in a cultural cover.

Deoras: A Child of the Organisation

Three sealed letters of Golwalkar addressing ‘To all Swayamsevak Brothers’ were opened soon after his death in 1973. As per his wish expressed in the first letter, Balasaheb Deoras became the next sarsanghchalak. Golwalkar thus followed the same tradition set by Hedgewar. Unlike Golwalkar, who was a late entrant to the RSS, Balasaheb came under the influence of Hedgewar at the age of twelve and soon became one of his favourite swayamsevaks. Having thus entered the RSS that had been formed only two years earlier, Balasaheb grew with it and in it. He was adventurous and displayed leadership qualities since childhood. In 1939, Balasaheb became a full-time RSS pracharak in Nagpur. Then he was sent on an assignment to Calcutta for a year. After his return, he became the city secretary of Nagpur. This was a strategic position as Nagpur was the key to organisational control. In 1942, Balasaheb trained a big batch of RSS workers of Nagpur and dispatched them to different provinces. When Bhayaji Dani was sarkaryavah, Balasaheb acted as sar-sarkaryavah for many years. In 1965, Balasaheb was appointed sarkaryavah and continued in that office till 1973. Doeras was thus rightly described as a true child of the organisation. He was more of a ‘machine operator’ who had been controlling the RSS ever since the days of Hedgewar.

![MS Golwalkar, the second sarsanghchalak of the RSS. [Photo Credit: rss.org]](http://indianhistorycollective.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Golwalkar.jpeg)

MS Golwalkar, the second sarsanghchalak of the RSS. [Photo Credit: rss.org]

Practical and Pragmatic

Balasaheb himself admitted that he was a student of philosophy, he lacked interest in pursuing the systems of thought. Like Hedgewar, he was known for his pragmatism, prompting Golwalkar to announce before a group of swayamsevaks as early as 1944: “If you you want to know Dr. Hedgewar, look at this young man!” He has been described as a person ‘without inhibitions’, ‘practical and pragmatic’ and ‘without any taboos regarding rites and rituals, or the practice of religiosity.’ Besides his pragmatism, he had ‘a sharp critical understanding and ability to analyse situations and suggest solutions.’ Thus the RSS clarified that his pragmaticism did not shun ideology and Hindutva was no less important to Deoras.

Three sealed letters of Golwalkar addressing ‘To all Swayamsevak Brothers’ were opened soon after his death in 1973. As per his wish expressed in the first letter, Balasaheb Deoras became the next sarsanghchalak. Golwalkar thus followed the same tradition set by Hedgewar. Unlike Golwalkar, who was a late entrant to the RSS, Balasaheb came under the influence of Hedgewar at the age of twelve and soon became one of his favourite swayamsevaks.

Organizational Reorientation: Evolving an Innovative Mechanism

As a man of organisation and pragmatic orientation, Deoras brought about changes in the organisational set-up to make it capable of political action. First, the old hierarchical structure was brought in line with the electoral constituency division. Each RSS district would now cover one or two parliamentary constituencies; below that came the assembly and municipal constituency divisions. The purpose was to build up a well-oiled election machinery. The shakhas were assigned a much wider role; they became the basic centres not only for elections to legislatures but also for managing elections of various trade unions, student unions and other socio-cultural organisations of the Sangh Parivar working within their respective areas. Secondly, the area of work between the RSS and its affiliates were properly divided; while the latter would concentrate on propaganda, the ground organisation would be controlled and manned by the former. Thirdly, married men were encouraged to take up full-time work. And to tackle the financial burden, an elaborate plan was prepared to secure control over educational and other institutions where the full-time workers could be given employment without any cost to RSS as such. Finally, changes were brought in the system of fund collection. In the past the collection through Guru Dakshina was kept secret. This was replaced by a new system whereby the head of a shakha would come to know what contribution has been made by whom. As a result it was found out that the amount of collection was more in the Jana Sangh-ruled areas.

The Early RSS Team. Sitting (L-R): Appaji Joshi, Dr KB Hedgewar, MS Golwalkar

and Buban Rao Pandit. Standing (L-R) Vithal Rao Patki and Balasaheb Deoras.

Soon after his takeover, Deoras reiterated his commitment to Golwalkar’s Hindu Rashtra. For him, too, the problem of Hindustan is not the Muslim or the Christian, but the disunity among the Hindus. Therefore, the aim of the Hindu sangathan should never be undermined: ‘We are convinced that when the Hindu becomes strong and united, the whole country will become strong and united.’ Despite the confirmation of ideological continuity, Deoras made a break with Golwalkar’s hesitation towards politics. Unlike Golwalkar, he had ‘no inclination towards the spiritual.’ In contrast to Golwalkar’s idealism and quietism, Deoras displayed a flair for pragmatism and activism. But it was not just his personal flat for politics that impelled him to carve out an active political role for the RSS. Rather certain objective conditions in the country facilitated the direct political intervention of the RSS.

Seeking an Alternative National Ideology and Politics

The Indian political scene was quite volatile when Deoras took over the RSS. The Congress system seemed to have exhausted its potential and was losing its political hegemony by the early 1970s. Many senior and well-known leaders (the syndicate) had deserted the Congress party but were neither able to challenge Indira Gandhi effectively nor provide an alternative socio-economic model of development. On the other hand Indira Gandhi’s Garibi Hatao campaign was turning out to be more popular than substantive. Meanwhile, in 1964, there occurred a split in the communist party of India; both the Communist Parties, the CPI and CPI (M), were mainly confined to their regional bases. The Naxalite movement, which emerged subsequently by challenging the CPI(M), had also splintered into a dozen of groups.

The Indian political scene was quite volatile when Deoras took over the RSS. The Congress system seemed to have exhausted its potential and was losing its political hegemony by the early 1970s. Many senior and well-known leaders (the syndicate) had deserted the Congress party but were neither able to challenge Indira Gandhi effectively nor provide an alternative socio-economic model of development.

Further, post-independent India had passed through some unique experiences. A sovereign polity had already emerged on the foundation of universal franchise. Centralised rule had consolidated the national market. The communications network expanded with the use of radio and television. There was also a substantial increase in literacy rates. These developments had brought the Indian masses from diverse regions and social backgrounds into direct contact and inter-dependence. All these factors had created an objective situation for the re-casting of an all-encompassing pan-Indian identity. In the absence of any anti-imperialist struggle, anti-colonialism had lost all attraction as a binding force. An alternative national definition was needed in such a changed socio-economic-political scenario. But neither the Congress nor the Left were capable of providing such a definition.

Deoras was quick to grasp this fluidity and uncertainty in the national political scene and thought it ideal for the RSS to enter the political fray with its alternative national agenda. He thus announced that ‘the extreme opinion that the swayamsevak of the Sangh should have nothing to do with the world around him is patently wrong’ and gave a call to swayamsevaks ‘to participate in every field of national life for reformation according to RSS thinking.’ It was a daring adventure of Deoras to bring the RSS into open politics, a strategic shift from the cautious approach taken by Golwalkar.

A New Political Strategy: Rejuvenating the Affiliates

This decision of the forest to enter the political arena was also partly attributed to the growing strength of the RSS over the last thirty three years of Golwalkar’s long reign; it has undergone a phenomenal expansion having shakhas in almost every part of the country. Besides the parent organisation, the other family members were shaping up quite well particularly the BJS, the ABVP and the BMS. The political front, the BJS, had traveled a long way since its first session at Kanpur in 1952. The 1973 Kanpur session of the party showed the strength the party had acquired in the last two decades. Its labour affiliate, the BMS, had emerged as one of the strongest labour organisations in the country. Its student affiliate the ABVP had set up about 600 branches having 1,65,000 members and 24 full-time workers.

Therefore, Deoras was confident that the RSS, with its wider family network, could take up a new challenging role. Accordingly, he adopted a new strategy that reflected his political astuteness. Deoras rightly understood that despite the expansion of the BJS, its performance in the parliamentary election of 1971 and subsequent assembly elections in 1972 was quite dismal. Hence, instead of relying totally on this affiliate, the RSS should look forward to other affiliates. Thus Deoras concentrated on the two most promising affiliates, the ABVP and BMS, working among students and labour respectively. He foresaw that both these affiliates along with the BJS would play a leading role in the political struggle in the future.

Gujarat provided the first opportunity to Deoras to test the viability of his new strategy. The Congress party had begun to lose its political base there. After the 1969 split in the party, Indira Gandhi adopted a personalized and populist style to establish her party in the province. The state government announced reservations for lower castes, which was opposed by massive agitations. Thus Gujarat became the site for competitive populism resulting in riotous street politics.

Accordingly, he adopted a new strategy that reflected his political astuteness. Deoras rightly understood that despite the expansion of the BJS, its performance in the parliamentary election of 1971 and subsequent assembly elections in 1972 was quite dismal. Hence, instead of relying totally on this affiliate, the RSS should look forward to other affiliates. Thus Deoras concentrated on the two most promising affiliates, the ABVP and BMS, working among students and labour respectively.

RSS galvanized ABVP to spearhead the struggle, under the banner of Nav Nirman Samiti, against the allegedly corrupt government of Chimanbhai Patel. The movement succeeded by overthrowing the government. The ABVP proved its political potential. The RSS gained confidence at this success and thought of carrying out such struggles against the corrupt inefficient Congress government in other states. Thus using mass street mobilizations to topple governments became a standard practice. The next stage was set in Bihar.

Aligning with Jayaprakash Narayan against Indira Gandhi

Meanwhile Indira Gandhi’s authoritarian style of functioning was getting pronounced day by day. The RSS was quick to understand the nature of her functioning and started opposing it. For example, the RSS took strong objection to the question of supercession of senior judges of the Supreme Court in the appointment of the Chief Justice. An editorial of the Organiser warned that ‘the politically conscious elements of Indian society will have to exert themselves to keep the press free, the judiciary independent and the legislatures responsive – if India is not to drift into the nightmare of a corrupt dictatorship.’ Referring to the appeal of the Congress leader Shashi Bhushan for a ‘limited dictatorship,’ L.K. Advani cautioned: ‘it seems the Congress-I is seriously toying with the idea of scuttling democracy, and supplanting it with a totalitarian or quasi-totalitarian set-up.’ Thus, the RSS started taking a strong position against the authoritarian tendency of Indira Gandhi.

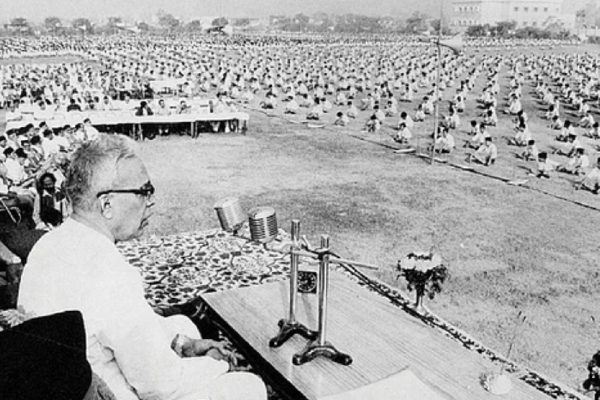

Jayaprakash Narayan’s support played a significant role in bringing the RSS into the mainstream

Jayaprakash Narayan launched a protest movement against the corrupt Congress government of Bihar. The ABVP became a part of the Chhatra Sangharsh Samiti (CSS) and joined the JP movement. In late 1974, the movement changed its character by moving beyond Bihar and targeting Indira Gandhi. JP’s concept of ‘total revolution’ was endorsed by the RSS. The ABPS of the RSS took the unusual step of supporting Narayan’s ‘total revolution,’ though it maintained its tradition of keeping a loop from political activities. In a rally at Delhi Balasaheb Deoras called JP a ‘saint’ who had ‘come to rescue society in dark and critical times.

Jayaprakash Narayan launched a protest movement against the corrupt Congress government of Bihar. The ABVP became a part of the Chhatra Sangharsh Samiti (CSS) and joined the JP movement. In late 1974, the movement changed its character by moving beyond Bihar and targeting Indira Gandhi. JP’s concept of ‘total revolution’ was endorsed by the RSS.

Jayaprakash reciprocated the compliment by publicly praising the Sangh Parivar. He attended the 20th All-India session of the Jana Sangh and declared, ‘If Jana Sangh is fascist, then I, too, am a fascist.’ He further complimented the RSS for its efforts to reduce economic inequality and corruption. Both JP and the RSS needed each other. While JP had the leadership, the RSS had committed cadre. Any struggle against Indira Gandhi demanded a close cooperation between the two. JP’s approbation certainly enhanced the public stature of the RSS. The old stigma of ‘Mahatma Gandhi’s murderer’ was considerably blunted with the certificate from a former close associate of Mahatma Gandhi.

RSS and Anti-Emergency Struggle

On 5 June 1975, the Allahabad High court declared Indira Gandhi’s election to the parliament invalid due to violations of election law. The opposition parties demanded her resignation. They formed the Lok Sangharsh Samiti (LSS) to coordinate the activities of the JP movement. Nana Deshmukh, a former RSS pracharak, and the organising secretary of the BJS, became its general secretary. On 25 June 1975 JP gave a call to the defence forces not to carry out the ‘illegal order.’ The next morning a state of Emergency was declared and the political opponents of Indira Gandhi including Balasaheb Deoras were arrested. The RSS was banned on 5th July 1975 under Defence of India Rules, 1971, and a large number of RSS members were arrested.

The initial response of the RSS was cautious. Madhavrao Mulay, the general secretary, declared the organisation has been dissolved. However, the RSS kept alive an effective skeleton organisation, although in shakhas, training camp, parades and other activities were stopped. Soon some leading pracharaks, after consulting imprisoned Balasaheb Deoras, met at Bombay in late July to chart out the action plan for their banned organisation. They decided that the RSS would work closely with the LSS, thus breaking the RSS tradition of keeping the organisation aloof from political movements. The coordinating work of the RSS with the RSS would be carried out by the four zonal pracharaks: Yadavrao Joshi (south), Rajendra Singh (north), Moropant Pingale (west), and Bhao Rao (east). In addition, while Rambahu Godbole was entrusted with the task of contacting the opposition party leaders, Eknath Ranade was to liaison with the government. Incidentally, Ranade was assigned the same job during the previous ban of 1948-9. This meeting also charted the following course of action for the band organisation: (a) to keep up the moral of the swayamsevaks by arranging some form of congregations; (b) to establish an underground press; (c) prepare for the nationwide satyagraha, establishing contact with significant non-political figures and with prominent representatives of the minority communities; and (d) solicit overseas Indian support for the RSS in the underground activities of the LSS. However, many critics believe that the RSS was keen on a compromise rather than fight Indira Gandhi.

Balasaheb Deoras (on wheelchair) was also jailed during the Emergency

Despite these versions, other evidence suggests that the RSS played a key role in the struggle against Emergency. Its cadre was the backbone of the LSS which spearheaded the JP movement. After the arrest of JP, Nana Deshmukh assumed the responsibility of leading the LSS. When Deshmukh was arrested, D.B. Thangadi, the general secretary of the BMS, took charge. Thus the RSS contributed its cadre and leaders to the LSS of the anti-Emergency struggle. Thousands of its members were arrested while offering satyagraha against the authoritarian regime of Indira Gandhi.

Despite these versions, other evidence suggests that the RSS played a key role in the struggle against Emergency. Its cadre was the backbone of the LSS which spearheaded the JP movement. After the arrest of JP, Nana Deshmukh assumed the responsibility of leading the LSS. When Deshmukh was arrested, D.B. Thangadi, the general secretary of the BMS, took charge. Thus the RSS contributed its cadre and leaders to the LSS of the anti-Emergency struggle.

However, it is not to argue that it was only the RSS and its affiliates that participated in the struggle. All opposition parties like the Samyukta Socialist party (SSP), the Bharat Lok Sal (BLS) the Congress (Organisation), the CPI (Marxist), and Naxalites opposed the Emergency. Even many students, teachers, lawyers, doctors, actors, writers, peasants, workers and other professionals, who did not have any party-affiliation, sacrificed their career to join the struggle against dictatorship and authoritarianism. Thus, it was a concerted effort of all individuals, groups and political parties who wanted the restoration of democracy in India. Therefore, the credit goes to the Indian people who participated and sympathized with the struggle.

Post Emergency Era: Politics of Accommodation and Ideological Flexibility

The Emergency experience greatly exposed the cadres and the leaders of the RSS to the political environment of the country and made them ambitious. They felt proud of having participated in the ‘second freedom struggle.’ This baptization was badly needed for any political claim in the future as the RSS avoided the fight against colonialism during the freedom struggle. This participation gave them a unique opportunity to feel the political pulse of the people. It also widened the limited political outlook of the Jana Sangh experiment. Their interaction with different political parties, groups and individuals prove to be immensely beneficial.

All these new experiences compelled the RSS leaders to ponder whether they should continue to stick to the old and logical framework of the Hindu Rashtra or should they redefine it in the light of the changed political dynamics. Deoras rightly realised that to remain in the mainstream of national politics, the RSS should opt for a politics of accommodation. Therefore, as the realpolitik demanded, there should be no hesitation to redefine its exclusivist ideological moorings and seek a politics of pragmatism and accommodation. This changing attitude of the RSS leadership helped the formation of the Janata alliance of the opposition parties when general elections were announced. The RSS cadre campaigned vigorously against Indira Gandhi. The Janata alliance won the elections. After the victory the ban on the RSS was lifted on 4 July 1977.

RSS during Janata Period

The Janata alliance became Janata Party on 1 May 1977. The RSS approved the merger of the BJS in this new party which formed the first non-Congress government in New Delhi. Three of its swayamsevaks from the Jana Sangh group, A.B. Vajpayee, L.K. Advani and Brij Lal Verma, got cabinet berths in the Morarji government. After the June assembly elections, the Jana Sangh members became chief ministers in three States, Himachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan and in the Union Territory of Delhi; and shared power in UP, Bihar Haryana and Orissa. Again most of them were RSS swayamsevaks.

The Janata Party had many phenomenal victories in the 1977 elections

The other constituents of the Janata Party, particularly the erstwhile socialists, were quick to grasp the growing influence of the RSS. They feared, on the basis of its large disciplined cadres and its influence of the erstwhile Jana Sangh members, the RSS would soon become too powerful and eclipse other constituents of the Janata Party. Therefore the devised a strategy to keep the RSS under control. It was suggested that the RSS should merge with the youth wing of the Janata Party to form a united volunteer organisation. This was rejected by the RSS.

The Janata alliance became Janata Party on 1 May 1977. The RSS approved the merger of the BJS in this new party which formed the first non-Congress government in New Delhi. Three of its swayamsevaks from the Jana Sangh group, A.B. Vajpayee, L.K. Advani and Brij Lal Verma, got cabinet berths in the Morarji government.

Deoras did not accept the proposal, which he thought, would certainly adversely affect the long-term objectives of his organisation. This would not only invite intense political attack from detractors, but would also bring decadent political culture to the RSS. Therefore, the RSS, as an organisation, should never become a part of the government. Even the BMS and the ABVP were not allowed to merge the identities with respective labour and student counterparts of the Janata Party. Besides ,being strongly entrenched in the Janata government and with political affiliates taking care of the RSS interests, Deoras not feel any real need for such a merger.

Thus Deoras cleverly avoided the politics of competition and bickering. He rather preferred to concentrate in and spend his energy on other areas where there was hardly any competition and the RSS could expand its support base more quickly and effectively. Accordingly, the RSS sought mutual cooperation with the Janata government in the areas of adult education, social welfare, youth affairs etc. Government patronage, the RSS reasoned, would ensure the flow of resources for these welfare activities.

There was another dimension: the RSS and its affiliates had been growing at a fast pace and the financial burden was becoming heavier for the maintenance of its growing number of whole-timers and another karykartas. Their involvement in the RSS projects would provide them engagement as well as financial assistance. With this strategy, the RSS expanded its sphere of influence in the government as well as non-government sectors and grew rapidly during the Janata regime.

Controversy on ‘Dual Membership’ and admitting non-Hindus

This rapid growth of the RSS alarmed other Janata constituents. They became apprehensive that the erstwhile BJS, backed by the strong and disciplined RSS cadre, would soon control the organisational apparatus of the party. Therefore, they raised the question of dual membership and demanded the members of the old BJS should sever their links with the RSS as the party constitution denied membership to any anybody belonging to any other political party, communal or other, which has a separate membership, constitution and programme. They pleaded that any association of the members of the Janata party with the RSS, a ‘Hindu communal organisation’ would undermine the secular credentials of the party. The Jana Sangh faction countered that the RSS was a cultural organisation and there was no restriction to be associated with it.

Surprisingly, the RSS phenomenon did not come up either during the parliament elections or the time of the merger of the Jana Sangh with the Janata Party. They were raised only when the struggle for power became intense between the constituents of the party. This issue of ‘dual membership’ was used to both gain leverage against the Jana Sangh group and to damage their capacity to mobilize additional support within the Janata party.

Thus Deoras cleverly avoided the politics of competition and bickering. He rather preferred to concentrate in and spend his energy on other areas where there was hardly any competition and the RSS could expand its support base more quickly and effectively. Accordingly, the RSS sought mutual cooperation with the Janata government in the areas of adult education, social welfare, youth affairs etc. Government patronage, the RSS reasoned, would ensure the flow of resources for these welfare activities.

To tackle the issue of dual membership, the RSS announced the opening of its doors to non-Hindus. As discussed earlier, the Emergency experience had softened its attitudes towards non-Hindus. Jayaprakash Narayan, the new political mentor of the RSS, had been emphasizing this issue for quite some time. Moreover, the Jana Sangh constituent of the Janata Party wanted its parent party to adopt an inclusive policy of admission, which would save its leaders from constant criticism and embarrassment in the Party forum. While Adopting the open door policy, the RSS did not compromise on its traditional goal of uniting the Hindu community. Its leadership was clearly reluctant to take any action which might undermine the brotherhood’s commitment to each other and to the RSS.

Demise of the Janata party and Disillusionment of the RSS

Even this gesture of the RSS could not stop the division of the party. Raj Narayan was the first to leave the party to form the Janata (Secular) Party, thereby claiming that the Janata Party was ‘unsecular.’ The next exit was of the Charan Singh group which also took a strong anti-RSS stance. Morarji Desai lost his majority and resigned 15 June 1979. The Jana Sangha faction threw its weight with Jagjivan Ram, a Harijan leader, thus attempting to shed its upper-caste image. However, the President invited Charan Singh to form the government. The caretaker government, being unable to muster support, resigned, and general elections were held in January 1980. The election gave a massive mandate to Indira Gandhi and proved to be a disaster for the Janata Party.

![Jagjivan Ram (Left) and Chaudhary Charan Singh. [Photo Credits: charansingh.org]](http://indianhistorycollective.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/CSandJagjivanram.jpeg)

Jagjivan Ram (Left) and Chaudhary Charan Singh. [Photo Credits: charansingh.org]

The leaders of the Janata Party analysed the causes of the electoral defeat. On the one hand, Jagjivan Ram attributed the defeat to the ‘hostile activities of the RSS,’ and also charged that a ‘secret’ understanding existed between the RSS and Indira Gandhi. On the other hand, some other leaders argued that the presence of the RSS members in the party gave it a communal image, thereby resulting in the loss of support of the minorities and lower castes and leading to the pole debacle. The Janata Party had to sort out the RSS issue once and for all.

Some leaders of the Janata party again raised the question of ‘dual membership’ and wanted the Jana Sangh group to sever ties with the RSS. This time the Jana Sangha constituent left it on the wisdom of the RSS leadership, which preferred to keep deliberate silence. In the light of the new political configuration, it was perhaps a wise option. The RSS was thoroughly disillusioned with the internal bickering of the Janata Party. It saw the writing on the wall and thought it would be futile to attempt its resurrection. The RSS leadership realised it was high time for the Jana Sangh constituent to come out of the party and form an alternative of its own.

RSS Dilemma: Power Politics or Ideological Purity?

The political experience, though exciting, was not all that pleasant for the RSS leaders. It was exciting because it gives them an opportunity to acquire an all India status. They felt elated when each major decision of the national government required their approval, or at least their considered opinion. The RSS got a lot of publicity, its organisation and affiliates became known throughout the country and its leadership acquired a national stature and respect. Perhaps, except the Congress party, no other organisation had achieved this status.

The political experience, though exciting, was not all that pleasant for the RSS leaders. It was exciting because it gives them an opportunity to acquire an all India status. They felt elated when each major decision of the national government required their approval, or at least their considered opinion. The RSS got a lot of publicity, its organisation and affiliates became known throughout the country and its leadership acquired a national stature and respect. Perhaps, except the Congress party, no other organisation had achieved this status.

However, many traditionalists within the RSS got disillusioned with the evil effects of power politics. They thought that the ideology of the Hindu Rashtra was compromised when the RSS opened its doors to non-Hindus despite the fact that there was hardly any entry. Many RSS leaders did not appreciate the way the RSS was dragged into each and every controversy and advocated to go back to Golwalkar’s policy of quiet expansion. Moreover, factional politics was alien to their culture. Though they manage to suppress the revolt of Balraj Madhok with no difficulty, Subramanian Swamy’s public criticism of Vajpayee caused a lot of embarrassment to the RSS leaders.

All this mixed experience called for an introspection. What should be the ideological parameters? Should it go back to the old and rigid ideological roots of the Hindu Rashtra of Golwalkar era or stick to the softer version that it had been experimenting with during the post-Golwalkar phase? The positive gains of power politics far outweighed the negative experiences. It could not overlook the fact that its newly acquired power and status were primarily the fruits of power politics and a politics of accommodation. At the same time the RSS also could not ignore that there always remained a threat of slipping into pure power politics and losing its ideological goal. Therefore, it was gripped by a dilemma; in its search for an alternative political structure, the RSS could neither ignore the strength of its ideology nor the benefits of power politics.

Attempting a Synthesis: Birth of the Bharatiya Janata party (BJP)

In the midst of this dilemma, the Jana Sangh group of the Janata Party organised a convention on 5 April 1980 and announced the birth of the Bharatiya Janata Party. The new party, reflecting the RSS mind, tried for a synthesis of ideology and realpolitik. As it aspired to extend its geographical, demographic and ideological reach, the BJP required retaining and continuing certain traditions of the Janata Party. It retained the name of Janata, adopted the Lotus as a party symbol rather than the lamp of the Jana Sangh. Its new flag was half saffron and half green, the latter symbolising secularism. Though the party appointed RSS men in key positions, it co-opted a few leaders from a non-RSS and non-Jana Sangh background. Its organisation; structure was designed on the basis of participatory democracy rather than the democratic centralism of the RSS. However, in terms of the leadership structure and recruitment patterns, the BJP continued with its Jana Sangh and RSS heritage.

In the midst of this dilemma, the Jana Sangh group of the Janata Party organised a convention on 5 April 1980 and announced the birth of the Bharatiya Janata Party. The new party, reflecting the RSS mind, tried for a synthesis of ideology and realpolitik. As it aspired to extend its geographical, demographic and ideological reach, the BJP required retaining and continuing certain traditions of the Janata Party.

In terms of ideology, the party retained the Integral Humanism’ of Deendayal Upadhyay, while adopting Gandhian Socialism as the party’s statement of first principles. Its ideological modification of the militant Hindu nationalism of the Jana Sangh could be further noticed in its commitment to five principles (panch-nishtha), such as nationalism, national integration, democracy, secularism and value-based politics.

All these terms of synthesis reflected the ground political reality within the Sangh Parivar. The leading affiliates of the RSS, after the national political exposure and power sharing, were in no mood to return to the traditional ‘cultural’ line. More importantly, the BJP leaders hope to convert the party into a national alternative to the Congress. Therefore, it felt the necessity of moving beyond its old confines of high-caste, urban middle class, Hindi-speaking north India. The RSS fully endorsed this understanding of its political affiliate and tried to offer an ideological rationale through a mix of Hindu Rashtra and Gandhian Socialism. But certain hardliners in the party ranks were opposed to this hybrid ideology. These protests were perhaps supported by a section of RSS leadership, which did not appreciate this new line.

![Atal Behari Vajapayee during the BJP's first convention at Bandra. [Photo Credits: @indianhistorypics, Twitter]](http://indianhistorycollective.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/ABV.jpeg)

Atal Behari Vajpayee during the BJP’s convention at Bandra. [Photo Credits: @indianhistorypics, Twitter]

To some of the observers of Indian politics, this new ideological line of the BJP, particularly the adoption of Gandhian socialism indicated its ideological independence from the RSS. But it needs to be remembered that it was Deoras, who a year before the formation of the BJP, proudly claimed that ‘we are real followers of Gandhi’s principles of tolerance and non-violence.’ Then the RSS argued that on most issues nobody was closer to Gandhi then itself and claimed that his Hind Swaraj could very well be an RSS text. Further, since the days of the Bihar agitation, the RSS closely identified itself with Jayaprakash Narayan, a practitioner of Gandhian politics. Under his influence, the RSS had been consciously integrating Gandhian ideals in its various programmes to enhance its popularity and acceptability. Rajendra Singh, successor of Deoras, claimed that the Sangh Parivar had been following the legacy of Gandhi by trying ‘to fulfill his cherished dream of Ramrajya and Swadeshi:’ cow protection by the VHP, Swadeshi by SLM, upliftment of the tribals by VKA, Gandhiji’s gram-swaraj by DRI, and restoration of Bharatiya languages by Vidya Bharati. Moreover, the swayamsevaks’ life is the best example of Gandhiji’s precept of simple living.

Therefore, BJP’s adoption of Gandhian socialism was not at all contradictory to the RSS position. It rather reflected the ideological dilemma and confusion of the RSS, whicheasis pondering whether to go back to the ideological roots of Hindu Rashtra or adhere to Gandhi for political expediency. Further, A.B. Vajpayee and other moderates might try to influence the RSS leadership to permit them to experiment with this new line. But there was no evidence to suggest they were pursuing a line at the expense of the RSS. They could hardly afford to do so.

To some of the observers of Indian politics, this new ideological line of the BJP, particularly the adoption of Gandhian socialism indicated its ideological independence from the RSS. But it needs to be remembered that it was Deoras, who a year before the formation of the BJP, proudly claimed that ‘we are real followers of Gandhi’s principles of tolerance and non-violence.’… Further, since the days of the Bihar agitation, the RSS closely identified itself with Jayaprakash Narayan, a practitioner of Gandhian politics.

New Religio-political Strategy: Revival of the VHP

During these years of introspection, an incident occurred at Meenakshipuram in Tamil Nadu. Here, in 1981, some 1500 Harijans were converted to Islam. The RSS expressed its deep concern over the mass conversions and calls upon the government to impose a legal ban on conversion. It also called upon the ‘entire Hindu Society to bury the deep internal caste dissensions and pernicious practice of untouchability and stand up as one single homogenous family. In the prevailing circumstances, the incident provided an opportunity to the RSS to re-oriented its strategy.

As discussed earlier, Deoras, after taking over the leadership, adopted a strategy of activating and assigning the affiliates like the ABVP and the BMS a frontal role in the turbulent political years. These affiliates carried out their tasks quite successfully during and after the Emergency and also in the Janata days. In the context of new emerging possibilities on the issue of Meenakshipuram, a new strategy has to be adopted. Which affiliate could be entrusted to carry out the new assignment? The RSS found none of the tried affiliates suitable for this purpose. The VHP seemed to be ideal. Though set up way back in 1964, it was lying low till then. The VHP was primarily active among the tribals and untouchables by setting up schools, clinics and temples. Its main purpose was to block the influences of Christianity and Islam.

BJP’s inaugural conference, Bombay, 1980.

The Meenakshipuram incident brought a metamorphosis in the VHP. In the RSS strategy for the coming years, it was going to be the torchbearer. VHP took the assignment and raised the alarm of ‘Hinduism in Danger!’ It warned that, unless the conversions were immediately banned and reversed, Hindus would become minorities in India. The RSS sought to introduce the VHP to the various sects of Hindu religion and seek legitimacy for its future role as the vanguard of Hindu interests. Therefore, it organised a Hindu Unity conference in Delhi in September 1981 on the issue of Meenakshipuram, in which representatives from different Hindu organisations including the VHP participated. Karan Singh chaired the conference and it was decided to float a society called ‘Virat Hindu Samaj.’ The following office bearers were nominated to manage Virat Hindu Samaj: Karan Singh, president; Lala Hans Raj Gupta, working president; PC Gupta, commerce secretary, and Ashok Singhal, organising secretary. All of them trusted RSS men, except Karan Singh whose presence was primarily symbolic. As an able statesman and man of letters he was widely known among the educated. Moreover, as an erstwhile scione of the Hindu royal family of Jammu, his symbolic leadership would ensure the support of various Hindu sects to the imminent VHP-led movement. The Samaj decided to hold a ‘Virat Hindu Sammelan’ in Delhi on October 1981.

The Meenakshipuram incident brought a metamorphosis in the VHP. In the RSS strategy for the coming years, it was going to be the torchbearer. VHP took the assignment and raised the alarm of ‘Hinduism in Danger!’ It warned that, unless the conversions were immediately banned and reversed, Hindus would become minorities in India. The RSS sought to introduce the VHP to the various sects of Hindu religion and seek legitimacy for its future role as the vanguard of Hindu interests.

The Sangh Parivar organised the Virat Hindu Sammelan, a massive rally of the Hindus ‘for national identity and national integrity.’ The slogans raised in this rally are significant enough to be mentioned.

‘Hindu sare ek, ped ek hai shakha anek’ (All Hindus are one; it is one tree, even though it has innumerable branches); ‘Dhokha, lalach, petrodollar, nahin chalega, nahin chalega’ (fraud, corruption and petrol dollars shall not prevail); ‘Ek hi patni, ek Vidhan, Hindu ho ya Musalman’ (let there be one law and monogamy –– for Hindus and Muslims). These slogans reminded one of the ideal ideological thrust of the Golwalkar era by proposing a Hindu unity on the foundation of an anti-Muslim tirade. Another slogan which needs a special mention was ‘Hindu Hindu sab mil Jao, chooa chhot ka bhoot bhagao’ (let all Hindus unite and exercise The monster of untouchability). Golwalkar never gave priority to the abolition of untouchability. The Meenakshipuram conversion compelled the RSS to adopt a clear line on the issue. Deoras also understood that to become a national political force, the RSS had to co-opt the Untouchables on a much bigger scale. Therefore, the Virat Hindu Sammelan adopted the abolition of untouchability as one of its objectives.

Strategic Shift of the Congress: Indira Gandhi’s Hindu card

This religio-political strategy of the RSS got a further boost by Indira Gandhi’s new political approach. In fact, the post-Emergency Indira Gandhi government was a different one from her pre-Emergency regime. The radical slogan of Garibi Hatao was no more heard. Terms like ‘secular’ and ‘socialist’ fell out of favour. Rather, she preferred to remain under the spiritual guidance of Swami Dhirendra Brahmachari, made pilgrimages to sacred rivers, shrines and temples across the country and spoke of ‘Hindu hegemony’ in the Hindi heartland. Karan Singh was a prominent Congressmen and his participation in a RSS sponsored meeting must have been in her knowledge.

All these may be tactical as the Congress base among the minorities was shrinking and the conflict in Punjab and Kashmir had acquired a religio-political dimension. But Indira Gandhi’s new approach certainly generated enthusiasm among the leaders and cadres of the RSS. They felt happy that she was facilitating the growth of Hindu consciousness in the Hindi heartland, which the RSS had been aspiring all along. Some people in the RSS had raised the question: how far is it correct for the BJP to pursue diluted Hindutva, when ironically the Congress was taking a pro-Hindu posture.

Indira Gandhi’s thrust on Hindu rhetoric and rituals paid rich dividends to the Congress in the election of Jammu & Kashmir and Delhi held in early 1983. Surprisingly, the BJP was completely wiped out from the Jammu area, which had been traditional stronghold of the Jana Sanga. Most surprisingly for the party, in the Delhi elections, the Congress scored a convincing victory in the metropolitan council and corporation. Some speculated that the RSS cadres maintained a neutral stance in the elections as there was an understanding between the RSS and the Congress. However, no authentic information is available to substantiate this allegation. Many swayamsevaks of course voted for the Congress, as the RSS showed no enthusiasm for the BJP.

This religio-political strategy of the RSS got a further boost by Indira Gandhi’s new political approach. In fact, the post-Emergency Indira Gandhi government was a different one from her pre-Emergency regime. The radical slogan of Garibi Hatao was no more heard. Terms like ‘secular’ and ‘socialist’ fell out of favour. Rather, she preferred to remain under the spiritual guidance of Swami Dhirendra Brahmachari, made pilgrimages to sacred rivers, shrines and temples across the country and spoke of ‘Hindu hegemony’ in the Hindi heartland.

Though it is difficult to ascertain whether Indira Gandhi had a secret pact with the RSS, but her electoral victory certainly taught the RSS a few lessons: first, a distinct Hindu constituency still existed in the Hindi heartland, and if properly aroused, could give definite electoral dividends; and secondly, the loyalty of this constituency is not fixed and could be manipulated by any political party which had the ability to arouse it more passionately. These lessons had some implications for the RSS: first, its religio-political strategy, with VHP at the centre, needed to be further accentuated for mass mobilization of Hindus; secondly, the future ideological-political line of the BJP ought to be redefined.

Mass Mobilisation by VHP: Politics of Yatras

In the context of Indira Gandhi’s wooing of the Hindus, the VHP was perceived as an ideal instrument for the rival mobilization of the Hindus, particularly in north-India. The RSS carefully planned out the strategy. The traditional Hindu rituals of pilgrimage (tirth-yatras) had to be revived to reinforce the community consciousness among the Hindus. Accordingly the VHP organised three major ‘pilgrimages’ under the slogan of ‘Pilgrimage for Unity’ (Ekatmata Yatra) between mid-November and December 1983, for the whole of India: from Haridwar in the foothills of Himalayas to Rameshwaram in Tamil Nadu; from Pashupatinath in Nepal to Kanyakumari; and from Gangasagar in West Bengal to Somnath in Gujarat. Incidentally, all these three yatras intersected at Nagpur, the headquarters of the RSS.

The aim of these pilgrimages was to gloss over caste, sect and denominational differences and invoke the spirit of unity among Hindus. The message was clear: ‘Hinduism was in danger and no danger was more sinister than the possibility of a concerted movement of Muslim and untouchable communities working together; Signatories of the appeal to join the yatras include not only the members of the Sangh Parivar, but also the Arya Samaj, the Rotary Club, the Lions Club and also, more notably, the Jain Sampradaya, the Vaishnav Parivar, Sikh Parivar, Bauddha Sampradaya and Bharatiya Dalit Varga Sangh. Therefore, an attempt was made to associate virtually all non-Hindu communities with the yatras and to isolate the Muslims.

Balasaheb Deoras addressing a rally.

According to the VHP, this month-long campaign mobilized sixty million people and covered 85,000 km. The roots of the yatras were so designed that they touched maximum numbers of Hindu shrines and religious places. The chariots (rathas) of the VHP carried a huge portrait of Mother India (Bharat Mata) and urns (kalasha) containing Ganga water throughout the journey. Throughout the campaign, religious books, portraits of Bharat Mata, badges and stickers depicting ‘Om,’ yogasan charts and pictures of great men were sold through stalls setup on the road. Thus the VHP used a lot of Hindu religious ritual paraphernalia and sacred symbols to create a community consciousness among Hindus.

In the context of Indira Gandhi’s wooing of the Hindus, the VHP was perceived as an ideal instrument for the rival mobilization of the Hindus, particularly in north-India. The RSS carefully planned out the strategy. The traditional Hindu rituals of pilgrimage (tirth-yatras) had to be revived to reinforce the community consciousness among the Hindus. Accordingly the VHP organised three major ‘pilgrimages’ under the slogan of ‘Pilgrimage for Unity’ (Ekatmata Yatra) between mid-November and December 1983, for the whole of India…Incidentally, all these three yatras intersected at Nagpur, the headquarters of the RSS.

Invoking Politics of Ram: Deploying the Most Popular Hindu Symbol

The favourable response of the Hindus to these yatras then encouraged the RSS to search for a powerful and popular Hindu symbol that would further boost the mobilization. Ram, the most popular Hindu god of North India, fitted ideally into the scheme. In April 1984, the VHP, for the first time, announced its intention of liberating the Ram Janmabhoomi, the ‘birthplace of Ram’ at Ayodhya, which was allegedly destroyed by Babur to construct a mosque in the early sixteenth century. Few popular symbols like this could have mobilized the Hindus on such a gigantic scale.

The mobilization strategy was carefully worked out. The VHP Dharma Sansad gave a clarion call to free Lord Ram who was still behind bars and the Ram Janmabhoomi Mukti Yojana was launched. A huge chariot cavalcade – actually motorcade of trucks carrying images of ‘Lord Ram behind bars,’ were by a thousand karsevaks with swords and tridents – marched from Bihar towards Ayodhya. However, this march was interrupted due to Indira Gandhi’s assassination. 1985 witnessed the Ram-Janaki Rath Yatra. The stated aims were: first, to create a Hindu awakening and Hindu unity by emphasizing the need to transcend caste and sect differences in the worship of Lord Ram; and secondly, to popularize the concept of Ram Rajya, the ideal state.

Thus the most popular Hindu religious symbol of Ram was deployed to facilitate the politics of the Sangh Parivar.

The RSS announced that places like Somnath, Rameshwaram and Ayodhya were not merely religious places – but also points of national faith and unity. ‘Desecration of such points of national faith is an open aggression on our national life. And all such desecrated spots are verily blots on our national freedom. And eradication of all such stigmas is nothing less than vindication of our national ethos and honour.’ It viewed the Ram Janmabhoomi agitation as ‘a battle for national self-assertion’. In a surprising judgement in 1986, the Faizabad district judge ordered opening of the locks on the shrine allowing unhindered access to Hindu devotees. The VHP threatened to start a satyagraha if the locks were not open. The government complied with the court order and the temple was open to the devotees amidst much fanfare on 1 February 86.

Meanwhile, the issue of the Muslim Personal Law became a centre of controversy with the judgement of the Supreme Court in the Shah Bano case. The Rajiv Gandhi government not accept the Supreme Court ruling and introduced the Muslim Women’s Will under severe communal pressure. Why did the government yield to communal pressure? The Congress felt the need to stem the anger of Muslims over the Shah Bano verdict which was reflected in the results of various by-elections in Assam, Kishanganj (Bihar), Baroda (Gujarat) and other places. These defeats compelled the Congress to bring the Muslim Women’s Bill to retain its Muslim constituency. The Shah Bano controversy provided the Sangh Parivar a convenient handle to intensify their anti-Muslim campaign against the pretext of ‘appeasement of minorities.’ In the assessment of the Parivar leaders, this event marked a watershed in the mobilization of Hindus.

Ram, the most popular Hindu god of North India, fitted ideally into the scheme. In April 1984, the VHP, for the first time, announced its intention of liberating the Ram Janmabhumi, the ‘birthplace of Ram’ at Ayodhya, which was allegedly destroyed by Babur to construct a mosque in the early sixteenth century. Few popular symbols like this could have mobilized the Hindus on such a gigantic scale.

Consolidating the Organisation for Militant Offensive

During the decade 1979-89, the number of swayamsevaks of the RSS had swelled from 10 lakh to 18 lakh. The number of shakhas increased to 25,000 spreading over 18,880 cities and villages. It had 38 front organisations and 50 lakh people were connected with their activities. More importantly, the RSS showed spectacular growth in south India. For example, 3,000 daily shakhas and 900 weekly gatherings were organised in 12 out of 14 districts in Kerala. Therefore, the RSS was confident of its strength before it decided to go in for the offensive.

The centenary celebration year (1988-9) of K.B. Hedgewar provided the opportunity to the RSS to galvanize the cadre and propagate its ideology. Deoras spelt out three objectives during the year: first, to acquaint people with Hegdewar’s pre-RSS life; secondly, to propagate its ideology of Hindu Rashtra; and thirdly, to acquaint the people with its service projects. While centenaries of other patriots were ‘sarkari centenaries’ being sponsored by the government, this would be a ‘people’s centenary’ being solely ponsored by the RSS. On the government’s refusal to release a centenary stamp, the Rss, in protest, printed 1 crore cards having the picture of Hegdewar on the front and the map of Akhand Bharat with the saffron flag at the back. It planned that its swayamsevaks would read more than 2 lakh villages during the year. Thus this year was spent in preparation before the onslaught. Incidentally, the year 1999 was also celebrated as the silver jubilee of the VHP and various programs were undertaken to revitalize it.

A meeting of the top leaders of the Sangh Parivar took place at Ahmedabad on 24 March 1989. Beside Deoras, other important leaders of the Parivar who attended it were H.V. Sheshadri, Rajendra Singh Yadav, Rahul Joshi of the RSS, Ashok Singhal of the VHP, L.K. Advani, A.B. Vajpayee and S.S. Bhandari of BJP, B.P. Thengadi of BMS and Madan Das Devi of ABVP. A close coordination among the leading members of the RSS family was obviously required before going for the offensive.

Militant Offensive: Ramshila Pujan

Soon after the VHP’s decision to construct a temple in Ayodhya, the ABKM of the RSS appealed to all Hindus to extend their generous help for the purpose. The Allahabad High Court issues an interim directive to maintain the status quo of the disputed property. The RSS announced the Ram Janmabhoomi was beyond the purview of the court. The VHP now argued that if the government could overrule a judgement in the Shah Bano case through legislative action, it should also override the judgement on Ayodhya.

The event that became the eye of the storm, was Ramshila Pujan. The VHP launched a campaign to carry consecrated bricks, called Ramshilas, from every village with a population of 2,000 or above for the construction of the Ram temple. This programme was meticulously planned out. The bricks were taken to Ayodhya through panchayat centres, district headquarters and state capitals. A minimum contribution of Rs. 1.25 per head was collected. The VHP organised kirtans, prayers, discourses, musical concerts and symposia in the villages. The aim was to carry the ideology of Hindutva to each village and town and mobilize the Hindu through the medium of Ram. RSS leaders attended all the important Shila Pujan functions. The brick programme was simultaneously traditional in its vestments while highly innovative in form. Hindus of all regions and persuasions would engage in a common act of devotion to a single deity – Ram. No sponsor of a temple had ever before involved the general public in temple building on such a large scale.

During the decade 1979-89, the number of swayamsevaks of the RSS had swelled from 10 lakh to 18 lakh. The number of shakhas increased to 25,000 spreading over 18,880 cities and villages. It had 38 front organisations and 50 lakh people were connected with their activities. More importantly, the RSS showed spectacular growth in south India.

The beatific smile of Ram in VHP posters had been replaced by a war-like image – Ram with his trident and bow ready. This new imagery of Ram came from television epics – Ramanand Sagar’s Ramayana and BR Chopra’s Mahabharat. The latter especially glorified a militaristic and virile Hinduism. The telecasting of these epics on Doordarshan resulted from the decision of an insecure Congress party. Though Ram existed all along, popular perceptions were vague and varied. The telecasting of Ramayana, which was primarily based on the Ramcharitmanas of Tulsidas, ignored the traditions of ‘many Ramayanas’ projecting a uniform version. The serials certainly concreticised certain perceptions of Ram. For instance, when people were asked about Ayodhya before the telecast, though they identified Ayodhya as the birthplace of Ram, their idea about the place was still vague. After the telecast, they defined it as a town in UP. Thus the broadcasting of Ramayana and Mahabharata helped to create a national Hindu identity, a form of consciousness that had not hitherto existed.

It became easier for the VHP to project a militant Ram, a symbol of strength and power. Passionate slogans rent the air: ‘Saugandh Ram ki khate Hain hum Mandir vahin banaenge’ (We swear by Ram we will build the temple at the same site), ‘Baccha-baccha Ram ka, janma-bhoomi ke kaam ka’ (Every child belongs to Ram and for Ram Janmabhoomi) and ‘Jis Hindu ka khoon na khaule, khoon nahi vo pani hai; janmabhoomi ke kaam na aaye, vo bekaar jawanee hai’ (That Hindu whose blood does not boy has gotten his veins, you that is not do that does not serve the Ram Janmabhoomi is youth lived in vain). Therefore, the Ramshila campaign was not only mobilisational, it was confrontational as well. It became aggressively anti-Muslim and provoked communal violence. The government again yielded to the pressure of the RSS and VHP and permitted shilanyas.

BJP’s Metamorphosis: From Communal Harmony to ultra-Hinduism

Since the Meenakshipuram incident the VHP had taken a frontal role in religio-political mobilization. Being pushed back to the background, the BJP has been undergoing a transformation in tune with the new RSS strategy. The ideological dilemma that prevailed during its birth had gradually disappeared. In the beginning, in its attempt towards a synthesis, it demonstrated its commitment towards communal harmony. BJP’s ‘positive secularism’ promised ‘full protection of the life and property of the minorities.’ In his addressed to National Council of the party in 1982, Atal Behari Vajpayee advised the opposition parties to ‘resist the temptation of compromising with religious and communal fanaticism…simply to get power.’ The National Executive of the party passed a resolution on ‘Communal Harmony and Social Cohesion’ in 1983, which stated: ‘No religion encouraged or condones hatred of violence against one’s fellow beings…A Hindu, Moslem, Christian or whosoever maimed or killed is an Indian disabled or lost. Life and property lost is not just Hindu loss or Muslim loss but a national loss.’

The beatific smile of Ram in VHP posters had been replaced by a war-like image – Ram with his trident and bow ready. This new imagery of Ram came from television epics – Ramanand Sagar’s Ramayana and BR Chopra’s Mahabharat. The latter especially glorified a militaristic and virile Hinduism. The telecasting of these epics on Doordarshan resulted from the decision of an insecure Congress party.

The BJP began reverting to its ultra-Hindu posture after its 1984 electoral rout. It realized that the dilution of its earlier position as a champion of the Hindu had cost it dearly. Rajiv Gandhi’s landslide victory was attributed partly to his ability to win over most of the upper-caste support that previously went to the BJP. Therefore, a return-to-the-roots was to be adopted as the BJP’s main strategy. Deendayal’s ‘Integral Humanism’ replaced ‘Gandhian Socialism’ as the basic philosophy of the party in October 1985. LK Advani was installed as the new president of the party in May 1986.

LK Advani filing his election nomination. Narendra Modi (L), then an RSS worker, assisting him.

The BJP hardened its anti-Muslim position on the Shah Bano judgement and the subsequent Muslim Women’s Bill. While the party welcomed the judgement of the Supreme Court as ‘pre-eminently just and sensible,’ it strongly rejected the Muslim League knew that this judgement was an interference in the religious affairs of Muslims. Rajiv Gandhi’s move to amend the law was described as ‘retrograde, anti-women and a surrender to obscurantism bigotry.’ Advani observed that the Muslim Women Bill ran counter to the Directive Principles of the Constitution (Article 44) enjoining the state to frame a Uniform Civil Code. He reiterated that the concept of sarva dharma sama bhava should never make any distinction between one citizen and another on the ground of religion. The BJP intensified its anti-Muslim campaign by accusing the government of promoting ‘minorityism.’ LK Advani summed up ‘minorityism’ as the promotion of a minority complex among the minorities, which serves neither national interest nor even minority interest. He branded the secularism of the government as ‘pseudo-secularism.’

Besides the Shah Bano case, certain other factors facilitated the BJP’s anti-Muslim propaganda. A massive Hindu backlash was building up because of the situation in Punjab and Kashmir. The poll analysis of the Assam assembly elections confirmed the understanding of the RSS that if a party could get a block of Hindu votes, it had a fair chance of coming to power. The Asom Gana Parishad (AGP), despite the Muslim opposition, could get the majority on the basis of block Hindu votes. Henceforth the BJP decided to aim at the consolidation of Hindu votes in its favour. For garnering the Hindu votes, it became a practical necessity to harden its stance on controversial issues like Art. 370, Minorities Commission and Ayodhya. The BJP found particular potential in the Ayodhya dispute, which could not only refurbish its Hindu identity, but also create a solid Hindu vote bank.

Babri Masjid to Ram Janmabhoomi

It is interesting to note that the early party documents recognised the existence of the Babri Masjid at Ayodhya without any reservations. In the national executive meeting of the party held between December 1986 and January 1987, LK Advani condemned a Muslim organisation’s boycott call of Republic Day celebrations ‘in protest against the Babri masjid issue.’ Hence the BJP did not mention Ram Janmabhoomi or Ram Temple until then. It is only on June 1989 the national executive of the BJP adopted its first detailed resolution on Ayodhya at Palampur (Himachal Pradesh). The resolution categorically blamed Babur for destroying the temple situated at Ram Janmasthan at Ayodhya and constructing a mosque in its place. It made clear that the court ‘cannot adjudicate’ this dispute. As the resolution of the party demanded: ‘The sentiment of the people must be respected and Ram Janmasthan handed over to the Hindu – if possible through a negotiated settlement, or else, by legislation. Litigation certainly is no answer.’

The BJP began reverting to its ultra-Hindu posture after its 1984 electoral rout. It realized that the dilution of its earlier position as a champion of the Hindu had cost it dearly. Rajiv Gandhi’s landslide victory was attributed partly to his ability to win over most of the upper-caste support that previously went to the BJP. Therefore, a return-to-the-roots was to be adopted as the BJP’s main strategy.

Thus, with the Palampur resolution, the Babri Masjid was changed to Ram temple; and the BJP publicly committed to a militant Hindu line. The Palampur resolution signalled that the time had come for the BJP to take the leading role in the Ram Janmbhoomi agitation, which was so far under the control of the VHP. This new role further demanded that the party had to intensify its fanatically anti-Muslim and aggressively pro-Hindu campaigns. In this atmosphere Lok Sabha elections took place at the end of 1989.

Giant Electoral Leap: Courtesy Hindutva

The BJP election manifesto criticized the Congress on the Shah Bano case, its attempt to recognise Urdu as a second language in UP and above all, for not allowign the rebuilding of the Ram temple at Ayodhya. After the 1989 elections, no party won an absolute majority in parliament. However, the BJP increased its strength to a hefty 86 compared to a meagre 2 in the previous parliament. In the Uttar Pradesh assembly elections, it increased its tally from 16 to 57. During the subsequent elections for the 8 state assemblies held in early 1990, the BJP increased its tally to 496 from 162 in the previous assemblies. This electoral performance further convinced the Sangh Parivar that militant Hindutva could pay further electoral dividend.

The Janata Dal led National front formed a minority government with the support of the BJP as well as the left parties. BJP’s support to the National Front government, spelt out that in Advani’s letter of 29 November 1989, referred to specific ‘reservations’ – Article 370, Uniform Civil Code, Human Rights Commission and Ram Janmabhoomi. However, the BJP, as a major supporter of the government, acquired a decisive say in the affairs of governance. Though it did not participate in the government, it had its pound of flesh; its leaders were appointed as Governors in a few states. Through the appointment of Jagmohan as the Governor of Jammu and Kashmir it tried to monitor the Kashmir policy. As the nature of this new government was fragile, major political parties soon competed to expand their own support beside bases anticipating a mid-term poll. While the BJP continued to consolidate its Hindu constituency through the movement of the RSS, VP Singh announced various concessions to the Muslims in order to strengthen his hold among Muslims.

RSS objects to VP Singh’s Muslim appeasement

The Sangh Parivar objected to the following gestures of VP Singh’s government towards the Muslims. First, the Prime Minister met the Shahi Imam of Jama Masjid to express his ‘indebtedness.’ Secondly, he appointed a Muslim as the Home Minister of India for the first time. Thirdly, he ordered to throw open all protected mosques under the supervision of the Archaeological Survey of India for prayers during the Ramzan period. The RSS reminded the Prime Minister that Indira Gandhi had resisted the pressure and allowed prayers at Safdarjung only for a day in 1984. Moreover, VP Singh granted Rs. 50 lakh for renovation of the Jama Masjid, which did not fall under the protector category of monuments. The RSS argued that the masjid did not require any renovations and the grant would only benefit the Imam.