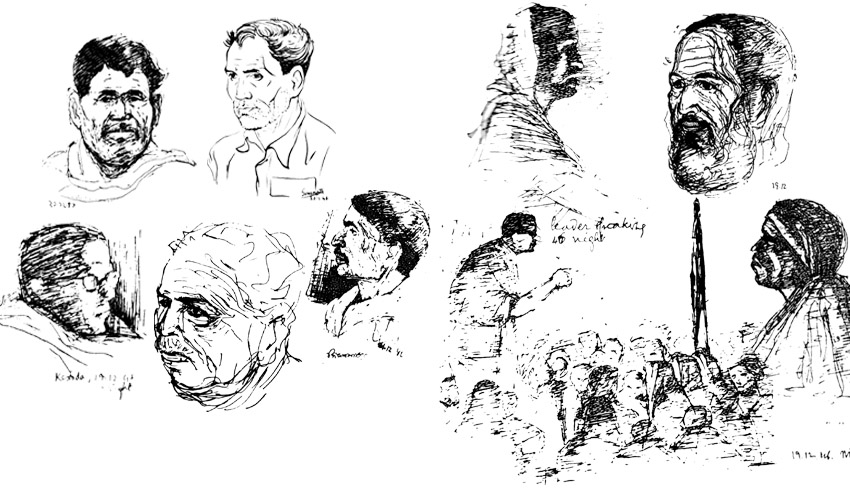

Wood Engraving by Somnath Hore depicting a meeting during the Tebhaga Movement. Courtesy Seagull Books.

Sociologist D. N. Dhanagare, who specialized in the study of farmer’s movements, called the Tebhaga movement of 1946-47 in Bengal “the outgrowth of left-wing mobilization of the rural masses” and “the first consciously attempted revolt by a politicized peasantry in Indian history”. Such facts and many others lie embedded in culture and art critic Samik Bandyopadhyay’s illuminating introduction to Tebhaga: An Artist’s Diary and Sketchbook by Somnath Hore (translated from Bengali by Somnath Zutshi).

To understand the movement, as well as Hore’s work, we have to first understand the context in which both arose. Here’s a brief summation of the history that Bandyopadhyay outlines.

Dhanagare described the Tebhaga (which translates into ‘sharing by thirds’) movement as “a struggle by sharecroppers to retain a two-thirds share of the produce for themselves and thereby to reduce the rent they paid to jotedars – a class of rich farmers who held superior rights in land – from one-half to one-third of their produce’.

To get a clear picture of the hierarchy, dating back to the Permanent Settlement of 1793, there were:

– the original zamindars,

– the jotedars, who the zamindars leased out their estates to, as intermediary tenure-holders,

– bargadars, or adhiars (from adhi, or ‘a half share’), or bhagchashis (literally translating into sharecroppers), who the jotedars sublet their plots to. These sharecroppers provided seeds, cattle, agricultural implements and manure and did all the farming themselves. They had no permanent right to reap the same land every year and had to pay the jotedars a rent of half of what they harvested.

This unjust system was kept in place by the fact that the jotedars, almost always, were also moneylenders who held the sharecroppers (and small holders of land) in their debt.

In 1938, the Land Revenue Commission appointed under Fazlul Haque’s government in Bengal recommended that the sharecroppers be treated as “protected tenants” and “the share of the crop, legally recoverable from them, be reduced from half to one-third of the produce”. Haque’s coalition government failed to act upon this recommendation, but it was indicative of a growing agrarian class struggle led by the freshly emerged Communist Party. The Communist leaders on ground were made up of locals and outsiders (many of the outsiders were revolutionaries released from the state prisons in 1937-38, and many of them had accepted Marxism in prison). They went to work in villages setting up units of the Kisan Sabha, a national union of peasants which had come under Communist control.

In September, 1946 – against the backdrop of communal riots in Bengal – the Bengal Provincial Kisan Sabha gave the call for the Tebhaga movement. The movement grew powerful in North Bengal and the Sundarban region of South Bengal (“where,” writes historian Partha Chatterjee, “the sharecropping was a widespread historical form of subtenancy with inferior rights”).

Somnath Hore, today remembered as one of India’s major painter-sculptors, was in his second year as a student at the Government Art College in Calcutta then. He was assigned by the Communist Party to document the Tebhaga movement in North Bengal. He wrote of how Communist leaders Somnath Lahiri and Nripen Chakraborty said to him in December, 1946: “If you want to have a look at the Tebhaga movement, go to Rangpur.” Bandyopadhyay, a Communist Party member himself, writes, “In the early 1940s, with the international struggle against fascism shaping a radical camaraderie among writers and artists all over the world, the Communist Party in India showed a genuine interest in forging connections between writers and artists and peasant and working-class insurgency.”

This is how Hore’s diary, covering 12 days, and his sketches from these days, came to be published in Ekshan. We have chosen to carry two diary entries from two days here: 19 and 25 December, of 1946.

The first entry – on 19 December, 1946 – takes you straight to the heart of the Tebhaga movement, bringing alive the evening before the sharecroppers are about to harvest the crop and – instead of handing the harvest, and consequently the power, over to the jotedars’ godowns – store it themselves. Hore sketches out the anticipation of the evening and night before, as well as the fears and doubts in the minds of sharecroppers and their overcoming these – with a feeling of hope – beautifully, in images as well as in simple but poignant prose (that Zutshi’s translation does great justice to).

He also exposes how the jotedars are trying to divide the movement along communal lines, something readers following the farmers’ protests of today would not be entirely unfamiliar with. As Bandyopadhyay writes, “Even before the political radicalization of Bengal in the 1920s could turn to land relations, communalism reared its ugly head in 1925-27, curbing the possibilities of a concerted movement by or for a growing poor peasant-sharecropper-agricultural labour class ruthlessly exploited by a rich peasant-moneylender-trader class.” Those following pre-electoral politics in the state of West Bengal today, too, may find it interesting to re-examine it through this lens.

In the second diary entry we have carried – from 25 December, 1946 – Hore examines another familiar theme, the collusion of the wealthy with the state (in this case the jotedars and the police) to try and break the peasant movement down by threatening arrests on unfounded grounds. Readers may need a little context here. According to a previous diary entry, Koramal, a jotedar, had gotten together with him a group of men and beaten Mani Sen, a Communist activist, with a lathi, while the latter was at a local sharecropper’s house. Upon a fellow activist and the sharecropper’s mother retaliating they were attacked too, and Koramal then fled to a nearby shed he owned, firing two guns he had with him to deter the crowd that had gathered, and made a getaway. Both Sen and his comrade were badly injured. And now false charges were being alleged against Harikanta Sarkar, one of the local leaders of the movement, by the same Koramal. Hore also explores the use by Jotedars of misinformation and false news. Again, very relevant to our times. Upon exhausting other means, the jotedars were running a campaign claiming that the Communist workers were actually “government agents”. Writes Hore: “The jotedars are obviously in a state of panic.”

Both diary entries also reflect a sense of nuance that only on-ground embedded reporting, over a period of nearly two weeks, can achieve. Hore details how peasants are swindled by grain-lending jotedars, by the devious trick of using a larger scoop while the peasants return the rice they have borrowed from them. Then there is the character of Harikanta Sarkar, who is himself “a fairly important jotedar” (as mentioned in another diary entry) and whose niece is married to the son of a jotedar opposing the Tebhaga movement. Yet Harikanta-da is a local Tebhaga leader himself and careful not to let jotedars he is related to “wrangle an exemption” from Tebhaga.

Besides the politics, Hore’s entries also throw up nuggets of local culture: the custom of kain, whereby a widow and widower can marry (progressive for its times, but it came with a brutal catch) and food cultures and dietary habits of the places he visits.

Hore’s entries – these ones as well as others – also convey a sense of how the Communist Party in Bengal was at work ‘on the ground’ in those days. The Tebhaga movement met a violent end, but possibly it did go on to provide a blueprint to the Communist Party (later: ‘parties’) for the kind of grassroots activism, and on-ground aid, it would persist in, leading – much after independence – to its sway in West Bengal politics and a land reform legitimising sharecroppers and assuring them of their dues like Operation Barga.

“Hore’s diary covers only 12 days and bears the mark of a young radical watching and admiring the revolutionary fervour and solidarity of a peasantry that he had never really seen from so close before,” writes Bandyopadhyay. So these entries must be viewed with that understanding. They also do not predict, in any way, the collapse of the movement under – as Partha Chatterjee writes – “direct and massive state repression, supported by the armed strength of the jotedar class”. After the police opened fire on a peasant demonstration, on 5th January, 1947, the land revenue minister, Fazlur Rehman, announced that the Bengal government would soon bring a bill to prevent the eviction of the sharecroppers, and assure them of two-thirds share. Such a bill was published in the Calcutta Gazette on 22 January, 1947. But, writes activist historian Sunil Sen, “the government was not serious about passing the Bargadars Bill, but had embarked on a repressive policy… In the face of police repression the peasants… were showing signs of vacillation… In the third week of February police repression began in full swing, and the government made it clear that the object was a knock-out blow.”

It is therefore important to view Hore’s art on Tebhaga on two different dates. The first: his drawings from the December of 1946. “One should not expect any artistic skill from them,” Hore wrote, modestly, in 1989. “Still, even today, my attachment to these drawings remains strong.” Bandyopadhyay describes Hore’s use of lines as “impersonal” and “photographic”, so as to “construct volume” and “reveal personality in the faces”, his commitment being to “objectivity” and “the immediate truth of the moment”. Hore was, at this time, the artist as a journalist. The work on the Tebhaga movement by Hore’s contemporary artists Chittaprasad and Debabrata Mukhopadhyay, by contrast, reveal what Bandyopadhyay calls “more conscious style”.

Then there is the Hore of six years later. In the early 1950s. The Communist Party, having supported the Congress at the time of the transfer of power, during independence, later called for a revolt against the government, was banned and subject to state repression due to which it went underground. It re-emerged as parliamentary opposition during the first general elections in 1951.

Hore himself went underground, as a Communist Party activist, in 1949. Later he went to Shantiniketan and came into contact with the artist Benode Behari Mukherjee, whose advice played a key role in his artistic evolution. Pranabranjan Ray writes the latter “awakened him (Hore) to the necessity of recognizing the vital role of pictorial space in any composition, and of the necessity of not treating the pictorial space as representing the natural space.”

And so we have the wood engravings that we have reproduced here, by a different Hore, six years after he had sketched what he saw of the Tebhaga movement. Bandyopadhyay writes of “the sharper opposition of black and white” in the pictures underscoring “a kind of illumination, a light glowing on the faces, chiselling them out of the darkness”. Also: “Hore brings to the experience of the night meetings the glow of awareness and faith that blazed in the villages he visited in 1946.” By now, Hore had become the artist as interpreter. And as with many great artists, his medium (in this case wood), and how he treated it, was his message. “Hore persisted with a dogged determination in his penetration of a reality which he defines in terms of man’s inhumanity to man, power riding roughshod over people, leaving them destitute and broken, with no fresh mobilization in sight,” Bandyopadhyay writes. “To penetrate into that reality, Hore set up for himself the barriers of material which he had to break into… or mould.”

First Row (L to R): Rupkanta-da; Mohan-da; a peasant leader speaking at the meeting on 19 December, 1946; a participant at the night meeting of 19 December, 1946. Second Row (L to R): Keshto-da; a jotedar; Dinesh-da; the meeting on the night of 19 December, 1946; listening to the speeches during the meeting of 19 December, 1946. Courtesy Seagull Books.

I set out around half-past nine in the morning after breakfast, to visit one of the centres of the Tebhaga movement. Prior to this, I had only heard about it from various comrades, and read about it in the papers. We, that is, Keshto-da, Ramen Banerjee, Ghulam Aziz and I were going to Badgachha. A little beyond Domar station, a farmer called out to Ghulam Aziz, ‘Comrade, we’re for Tebhaga.’ There were three or four of them, harvesting rice on their own land. Aziz shouted back, ‘You’re growing rice on your own land, through your own hard work. It’s not Tebhaga for you, it’s one hundred per cent. What on earth would you be doing Tebhaga for? That’s only for those who make fortunes by exploiting the labour of others and squeeze the peasant’s land dry. They’ll have to accept Tebhaga.’ The farmers nodded in agreement. ‘You’re right brother. Carry on with Tebhaga.’

We chatted with a few peasants as we entered Badgachha village, but their response was rather depressing. They seemed quite unenthusiastic about the rice harvest. We were here because we had heard that the rice harvesting had started in this village. Yet it seemed as though these people knew nothing about it. But we soon perked up as we went further. Two peasant women talked to us and said, ‘We did some harvesting yesterday. The comrades are on the other side of the village.’ The women were very enthusiastic. With real warmth they directed us to the red flag camp and seemed very pleased to hear that we were part of the Tebhaga movement.

Some lads working in a tobacco field answered Ghulam Aziz’s questions with great eagerness, saying that they dared the jotedars to do their worst. Tebhaga was what they believed in; they intended to complete harvesting the rice the next day. Their excited conversation was all about when they would get to the field all together, the slogans they would shout and how they would store the paddy in their own granaries once the harvesting was done.

Some lads working in a tobacco field answered Ghulam Aziz’s questions with great eagerness, saying that they dared the jotedars to do their worst. Tebhaga was what they believed in; they intended to complete harvesting the rice the next day. Their excited conversation was all about when they would get to the field all together, the slogans they would shout and how they would store the paddy in their own granaries once the harvesting was done.

Finally, we got to the camp. Comrade Narayan Banerjee was busy discussing the rice harvesting programme with some farmers. They greeted us with a red salute. We answered in kind. Everyone was saying the same thing, ‘We want Tebhaga. No one’s afraid of the jotedars. They’ve lost their nerve after the hat hartal. Khoka Thakur, the one who tried to stop the drumming in the market-place, has said that he is going to agree to our demands.’

Rupkanta-da, a local peasant leader, Mohan-da and Comrade Panchu turned up. It was decided to call a closed meeting that night. We expressed doubts—would there be a large enough gathering at such short notice? Rupkanta-da said, ‘Don’t worry about it. Once people hear that Tebhaga leaders from Calcutta have arrived, they won’t be able to stay away.’

I wandered off, notebook and pen in hand. Men of all ages, from children to grandfathers, were working in the tobacco fields, clad in the briefest of loin-cloths. Women wrapped from chest to knee were grazing their cows. They were not a well-built people, neither the men nor the women. One look could tell that they worked very hard for very little to eat. Their huts were small and built of mud and straw; they had cows for ploughing but these were thin and scrawny. I saw no other domestic animals apart from a few stray goats; certainly no ducks, hens or pigeons.

I returned for a bath and a quick meal. Rice, dal, and, through the kindness of a peasant comrade who had caught it, some fish. Dinesh Lahiri arrived in the evening. In Rangpur I had been told that Dinesh-da was the local gazette. He told me a lot of things about local customs and conditions, including kain. This is a custom prevalent among the local sharecroppers. A sharecropper who becomes a dena or widower faces a lot of difficulties and has problems raising a family, cultivating his land and running a household. If he is lucky enough to fall in love with a widow, he has a way out. If both are agreeable, they can live together as man and wife in his house. This sort of marriage is known locally as kain. Unfortunately, there’s one rather serious drawback. The children born of such relationships are considered illegitimate, and therefore have no status in local society.

The jotedars have thousands of crafty tricks for exploiting the peasants. For instance, when they loan grain to a peasant, they use a small scoop called a done with which they dole out the rice. But when the peasant comes to repay the debt of paddy, the jotedar invariably uses a larger scoop. Should the peasant enquire about the previous scoop, pat comes the reply, ‘God only knows what the kids have done with it.’

The jotedars have thousands of crafty tricks for exploiting the peasants. For instance, when they loan grain to a peasant, they use a small scoop called a done with which they dole out the rice. But when the peasant comes to repay the debt of paddy, the jotedar invariably uses a larger scoop. Should the peasant enquire about the previous scoop, pat comes the reply, ‘God only knows what the kids have done with it.’

In one village, some Muslim jotedars decided to try and start a communal riot between the Hindu and Muslim share-croppers. They told the Mulsims, ‘If you stop the Hindus from harvesting the rice, we’ll give you extra shares.’ The Muslims said, ‘Sorry, we’ll have nothing to do with it.’ The irate jotedars next went to a local fair and told the Muslim traders, ‘We’ll burn your houses down. But don’t worry, we’ll compensate you for your losses; all you have to do is say that the Hindus did it.’ The traders retorted with folded hands, ‘Please don’t involve us in all this, we’re not interested. And if you pressurize us we’ll move out at once with our stalls and everything.’ The frustrated jotedars finally got the message— they decided to seek a compromise with the peasants.

The meeting took place as scheduled at night, under the open sky, on the straw laid out on the ground inside the roofless shed of a sharecropper. Keshto-da was the principal speaker. The meeting started at about half-past nine, with close to 200 sharecroppers and peasants attending. Some of them had walked more than two miles on a bitterly cold winter’s evening in order to take part.

Keshto-da spoke about harvesting the rice. ‘You must finish harvesting the rice. Don’t wait for the others. Just organize yourselves into groups and start. You mustn’t store the harvested grain in the jotedar’s shed. Keep it in your homes and then distribute it according to the Tebhaga principle: two-thirds and one-third. And insist on a receipt. If a landlord refuses, keep his share of the harvest at your own house or deposit it at the Samiti’s stores. Organize volunteer forces, cut branches for lathis, raise banners, pick up your sickles and shout, “We want Tebhaga!” ’

From time to time Keshto-da interspersed his speech with slogans which were shouted back by a hundred voices. Occasionally there were questions, such as ‘What do we do if the police come?’ and ‘How can we break the law?’ and so on. They became silent once the questions were answered to their satisfaction. The excitement and enthusiasm were infectious. When Keshto-da shouted, ‘We’ll harvest the rice tomorrow!’ everyone roared back, ‘We’ll harvest the rice tomorrow! We will!’

In one village, some Muslim jotedars decided to try and start a communal riot between the Hindu and Muslim share-croppers. They told the Mulsims, ‘If you stop the Hindus from harvesting the rice, we’ll give you extra shares.’ The Muslims said, ‘Sorry, we’ll have nothing to do with it.’

A few of the jotedars’ hirelings were also present at the meeting. These were the ones who had raised the bogey of the law. After Keshto-da’s speech, the sharecroppers said, ‘Whatever we do is the law, there’s no other law. We’ll form our committees and set up our own courts. If the jotedars make mischief, we’ll teach them justice.’

Dinesh-da spoke next, in the local dialect. ‘No use creeping into your shells like tortoises everytime you see a rich man. Start walking with your heads held high. The rich say that we are dancing like whores to the refrains of Tebhaga. What I want to know is, who made whores of us anyway? And having turned us into whores, why does it hurt them to see us dance? Let the rich say what they want, we are going to harvest the rice and have the Tebhaga!

Hearing their innermost feelings expressed in their own language, the people were elated: they clapped loudly, cheered and sat up expectantly, eager to hear what Dinesh-da would say next.

The place began to resound with slogans. ‘We want our two thirds, not just half’; ‘No rice without a receipt’; ‘No interest on rice loans’; ‘Remove the harvest to your own homes’; ‘Long live the Krishak Samiti’; ‘Long live the revolution’ and so on. Some of the peasants didn’t join in to begin with. As soon as Dinesh-da announced that he would consider those who kept silent to be the jotedars’ stooges, however, everyone, young and old, started shouting slogans with great gusto. The handful of hirelings present had perforce to join in, otherwise they would have been marked out at once, and there’s nothing as bad as being identified as a landlord’s hirelings at such gatherings, for the jotedar is the peasant’s enemy, the country’s enemy.

Since arriving at this village, there’s one word which I have heard fre- quently: freedom. ‘The peasant is winning his freedom,’ they say. As I entered the village this morning, a young sharecropper said, ‘We are free at last.’ And, at night, I heard the same words from young and old alike: they were on their way to freedom. They were not afraid of either the police or the landlord’s thugs; they were ready to give their lives, but not their rice; they might die but those who remained would live as free men and women.

The meeting decided that the harvesting would start the next day and be completed in seven days’ time. The various rice fields to be harvested were also decided upon.

After the meeting broke up, the sharecroppers were beaming. Such excitement on every face! Since arriving at this village, there’s one word which I have heard fre- quently: freedom. ‘The peasant is winning his freedom,’ they say. As I entered the village this morning, a young sharecropper said, ‘We are free at last.’ And, at night, I heard the same words from young and old alike: they were on their way to freedom. They were not afraid of either the police or the landlord’s thugs; they were ready to give their lives, but not their rice; they might die but those who remained would live as free men and women. No one would dare oppress them any more.

Working in the tobacco field. Courtesy Seagull Books.

I was sketching a peasant hut in Harikanta-da’s house when the police arrived—a sergeant and a constable. ‘We want Harikanta-babu?’ ‘Why?’ ‘Don’t you know, the inspector wants to see him.’ ‘Well, where is the inspector?’ ‘He’s in the car outside.’ After I told them that Harikanta-babu was not in, the pair fidgeted for a while and then left.

I heard later that Harikanta-babu had met this lot. The officer had threatened to arrest him on charges of looting jotedar Koramal’s granary. Of course Harikanta-da paid not a jot of attention to this nonsense—the man was out of uniform, had no warrant and, above all, was travelling in Koramal’s car as if he was on his way to his in-laws. Meeting Harikanta-babu on the road, he had said, ‘I’ve got an unpleasant piece of news to give you. I have to arrest you.’

Everyone knew that the inspector was lining his pocket. ‘Koramal goes and attacks someone and this man comes to arrest Harikanta Sarkar on charges of looting Koramal’s granary! They must think we people are fools.’ This was the comment I heard everywhere I went. And the rumour was that the inspector had said that there were similar charges of looting against 30 or 35 people. (Later we learnt that he was merely a sergeant from Dimla and not an inspector.)

I heard later that Harikanta-babu had met this lot. The officer had threatened to arrest him on charges of looting jotedar Koramal’s granary… the man was out of uniform, had no warrant and, above all, was travelling in Koramal’s car as if he was on his way to his in-laws. Meeting Harikanta-babu on the road, he had said, ‘I’ve got an unpleasant piece of news to give you. I have to arrest you.’

I heard from comrade Mohi that apparently Koramal had earlier asked the inspector from Dimla Police Thana to stop the harvesting. This man had told Koramal that they didn’t have the authority to do so, but, if he could organize some kind of fracas and build a case on that, then they could find a way to help him out.

A few days later, Mani Krishna Sen was attacked. And today, there was this threat of arrest.

The ordinary peasants fear that the jotedars and the corrupt officials are conspiring to arrest the leaders of the movement and keep them in the lock-up for a few days, so that the jotedars can use the opportunity to harvest the rice and remove it to their own granaries. Obviously, the real motive is to simultaneously harvest the rice and break the movement, for it is quite clear that the charges will not stick. So the peasants have decided that they will prevent the arrests of their leaders and harvest the rice as soon as possible, storing it in their own houses. Then they will wait and see how far the legal games go.

Preparations were going on at full speed for non-stop harvesting. The sharecroppers seemed absolutely determined to overcome every obstacle and make a success of the movement.

Today, the Khadibadi landlord Umesh Sarkar’s rice was harvested. About 50 volunteers went to the fields armed with lathis. In all, seven sharecroppers’ rice has been harvested.

The harvesting is in full swing all around. Generally, the volunteers begin the harvesting of a sharecropper’s rice and remove it to his granary. From the next day onwards, the sharecropper does the harvesting on his own. Where there is a possibility of an attack by the jotedars’ men, the volunteers complete the task of storing the grain as an added source of protection.

I ate with comrade Jatin in the afternoon. Rice, dal and fritters of small fish and brinjal.

Since coming to these parts I’ve noticed that the people here eat their rice with just dal and a piece of fried vegetable or fish. It was the same at Badgachha. There don’t seem to be as many vegetables available here as we have in our district. And the same goes for fish. In any case, the poor sharecropper tends to think of rice and dal, or rice and some fried vegetable, as enough of a meal. It’s remarkable that people can live on so little protein and vitamin. Of course, the local rice is of fine quality and is rich in vitamins. Presumably that is what nourishes them somewhat. The quality of cooking is very poor.

Since coming to these parts I’ve noticed that the people here eat their rice with just dal and a piece of fried vegetable or fish… There don’t seem to be as many vegetables available here as we have in our district. And the same goes for fish. In any case, the poor sharecropper tends to think of rice and dal, or rice and some fried vegetable, as enough of a meal. It’s remarkable that people can live on so little protein and vitamin. Of course, the local rice is of fine quality and is rich in vitamins. Presumably that is what nourishes them somewhat.

We ate saoda at Harikanta-da’s elder brother’s house at night. Saoda is the curd, khoi (parched rice) and chida (flattened rice) that married daughters bring with them when they visit their parents. There was plenty of it. After the meal I learnt that this saoda had come from the house of jotedar Umesh Sarkar whose crop had been harvested that day. Harikanta-da’s niece is married to Umesh Sarkar’s son.

Umesh Sarkar had tried to use this relationship to influence Harikanta-da and wangle an exemption from Tebhaga. He was doomed to disappointment. A comrade joked, ‘He must be trying to cool us down with this curd on a winter’s night. But we won’t cool off!’

I had no inclination to have dinner after eating saoda. But I had to, for they had cooked ‘mutton-rice’. It’s only when I sat down to the meal that I realized what ‘mutton-rice’ was—it was mutton curry and rice.

One of Somnath Hore’s wood engravings on the Tebhaga Movement. Courtesy Seagull Books.

Harikanta-da, Abani Bagchi and some other comrades left for a meeting after finishing their meal. Early next morning Koramal Daga’s fields were to be extensively harvested. The meeting had been called to co-ordinate the preparations for it.

After the meal I learnt that this saoda had come from the house of jotedar Umesh Sarkar whose crop had been harvested that day. Harikanta-da’s niece is married to Umesh Sarkar’s son. Umesh Sarkar had tried to use this relationship to influence Harikanta-da and wangle an exemption from Tebhaga. He was doomed to disappointment.

A comrade returned from Teparhat with the report that the landlords were carrying out a campaign to the effect that Harikanta-da and the other comrades were government agents. The jotedars are obviously in a state of panic.

In one of the rooms a young sharecropper is singing:

The sun brings glory to the day,

To the night, the moon.

A ploughman’s glory is his ploughing

And land’s is in its paddy.

He has a sweet voice.

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of Seagull Books. You can buy Tebhaga: An Artist’s Diary and Sketchbook here.

Somnath Hore, one of India’s major painter-sculptors, worked in various media – print-making, drawing and watercolour – before turning to sculpture in his later years. Hore taught at Indian Art College and Delhi Polytechnic before coming to teach at Kala Bhavan, Shantiniketan and was also Visiting Lecturer at M. S. University, Baroda, for a short time. Author of Tebhagar Diary and Aamaar Chitro Bhabona, Hore received the Padma Bhushan (posthumously), the Aban-Gagan Puroshkar, the Lalit Kala Ratna and the Rabindra Bharati University Award, among many others. Hore lived and worked in Santiniketan till his death in 2006. You can read more about him and his work here.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply