The Indian Express

Happening within the hundred years of the “first war of Independence” — popularly known as the Sepoy Mutiny or the 1857 rebellion — the mutiny in 1946 that shook the stronghold of the British in Indian waters, is often forgotten from historical records and discourses. EH Carr while talking about “historian’s approach to causes” stated that an event’s interpretation by a historian often depends on the latter’s hierarchy of “significant causes”. So, whether the naval mutiny on the eve of Indian Independence struck the final chord in the achievement of independence or not, is a matter of debate, but its relevance as a mass movement, even for a sporadic period cannot be ignored. Pramod Kapoor takes up that fateful incident in his recent book ‘1946 Royal Indian Navy Mutiny: Last War of Independence’ and sheds light on the clock-time details of what happened and how it spread and finally succumbed to misfortune.

The European dominance on Indian seas, replacing the Maratha Sea prowess, began in 1612 when the first Indian marine Corps was instituted. After that, following a brief period of serving as a non-combatant force, Her Majesty’s Indian Marines were posted in Egyptian Campaigns in 1882 and 1885, and in Third Anglo-Burmese War in 1889. However, the establishment of the Royal Indian Navy in 1934 began a new chapter in Indian naval history. Sardar K.M. Pannikar, statesman, diplomat, and historian, highlighted the importance of establishing the Royal Indian Navy when he wrote: “After the destruction of the Maratha naval power in 1751, Indians were sailing the seas for the first time in warships – small and insignificant units no doubt, but symbolic of the resuscitation of the old forces which had for at least two millennia held the mastery of the Indian seas.”

What fuelled the mutiny in the navy? Was it merely a spontaneous uprising or a premeditated one?

Ranajit Guha in his article ‘The Prose of Counter-Insurgency’ talked about how administrators saw the peasant rebellions as “spontaneous and unpremeditated affairs.” However, according to him, “…they had far too much at stake and would not launch into it except as a deliberate, even if desperate, way out of an intolerable condition of existence. Insurgency, in other words, was a motivated and conscious undertaking on the part of the rural masses.”

A similar scenario applies to the 1946 naval mutiny as well.

“The first warnings of the brewing mutiny came on 1 February 1946. On that day, Rating R.K. Singh (whose full name is unknown) did something unprecedented. He resigned. In the RIN, you could be dismissed, demobilized, or retire, but you could not resign.”

The initial germination of the “seeds of mutiny” started from the day of the recruitment of the ratings. With the ongoing Second World War, the number of recruits was increasing day by day but the facilities that were promised to them were denied upon recruitment. Training facilities were inadequate, the living conditions were wretched, and the abusive languages that their senior authorities used made them feel like they were nothing more than slaves. Thus, much like the slaves in the Atlantic Slave trade, 200-220 Indian ratings were packed in ships that could hold only 100-120. Demobilization, along with surrender of kits and uniforms, and worst food quality were other factors that contributed to the rage against the British authorities. Hence, the overall atmosphere was reeling with a sense of betrayal. With the Quit India call and more recently, Azad Hind Fauz, in mind as inspiration, the Indian ratings staged a rebellion against the British.

However, to the misfortunes of the ratings, the political leaders of the country didn’t support the rebels’ cry. Pramod Kapoor writes, “The mutiny presented a dilemma for the leaders of the three main parties. The national sentiment was strongly in favor of the mutineers and they realized it would not benefit them politically to publicly go against the tide. So, at one level, they had to show solidarity in spirit with the movement. But at another level, it did not suit them to support a rebellion when the peaceful transfer of power seemed in their grasp.”

While the communists were in open support, Congress leaders were consistently asking the ratings to surrender. As for the Muslim League leaders, it was in no way connected to the freedom struggle. Instead, “Ibrahim Chundrigar, president of Bombay Provincial Muslim League, termed the episode an ‘unfortunate situation’”. Only Aruna Asaf Ali stood apart from her Congress counterparts and even went to the extent of publicly defying Gandhiji on the matter. On the latter’s advice of asking the rating to resign, Aruna Asaf Ali said, “If they did that they will have to give up their only means of livelihood. Moreover, they were fighting for principles…”.

If the main political leaders of the would-be country stayed “soft-pedaled” in this strike, who were the main architects of the mutiny? Was it only confined to Bombay and among the ratings? Or did it get support from the outside as well?

Even if the spread of the mutiny was not as wide and long-drawn as the 1857 mutiny, it wasn’t only confined to Castle Barracks, a shore establishment in Bombay, and HMIS Talwar, the RIN signal-training establishment and the main platform of rebellion. “By the morning of February 20, the strike had spread to Calcutta, Karachi, Madras, Jamnagar, Vishakapatnam, Cochin and other navy stations”, writes Anirban Mitra.

On 17th February, the B.C. Dutt and his fellow rebels decided to instigate other ratings around the cause of bad food and thus the following day when the call for assembly rang, the ratings didn’t show up. Followed by the battle cry “No food no work”, “Cries of ‘Inquilab Zindabad’” and “Quit India” echoed across the Talwar. Soon from the Talwar, the HMIS Gondwana, Akbar, Khyber, Clive, Punjab, Teer, Dhanush, Sind, Mahratta, Jamna, Kumaon, Oudh, Berar, Moti and eleven shore establishments including Castle Barracks, Fort Barracks, etc. joined in the strike. The next day Union Jack was brought down and flags of the Muslim League, Congress, and Communist Party were hurled. The demands of the mutineers weren’t only restricted to resolving the food problems, or racial discrimination, but it also had political demands such as releasing INA personnel and political prisoners, “immediate withdrawal of Indian troops from Indonesia and the Middle East” and inquiry regarding open firing all over India. These demands caused considerable problems for those who were negotiating the other set of ‘apolitical’ demands, however, the ratings were firm in their resolve to get whatever they wanted, at least initially!

As the mutiny reached its 5th day, Pramod Kapoor writes, “The mutiny was no longer confined to Bombay, nor was it purely a naval affair.” Royal Indian Air Force called a strike in sympathy with the ratings. The city of Bombay stood firmly behind the ratings. The mutiny even spread to Karachi whose political and naval importance was paramount. However, here also the political parties, except the Communists, refrained from supporting the mutiny. HMS Hindustan, Travancore, Champak, and Himalaya were some of the ships that played a key role in the Karachi mutiny.

Even if the Commission of Enquiry concluded otherwise, the planning for the 1946 RIN mutiny started much early, at the end-1945. The flat of Pran and Kusum Nair in the Riviera Building was where the mutiny was initially planned. The Nairs were the political mastermind of the mutiny and they chose the “ringleaders” of the mutiny. They were Balai Chandra Dutt, Rishi Dev Puri, Madan Singh, Muhammad Shuaib Khan, Y.K. Menon among others. However, despite all these plannings and executions, M.S. Khan, the signalman in HMS Talwar and the main leader of the mutiny, and his group of rebels had to finally surrender which in Khan’s words, was a “surrender to India and not to the British.” Their fights continued in the places where they were imprisoned. Upon release, the ratings were deemed unfit for any kind of employment in the Indian navy and as Pramod Kapoor writes, “it is thus that most of them became lost to history.”

Following the surrender of the rating, a routine Commission of Enquiry was formed to inquire into the whole matter. However, Pramod Kapoor writes, “it served more as a political tool than a judicial inquiry.” The Commission of Enquiry examined 229 witnesses.

Throughout its public proceedings, many stories of the mutiny or the “mass strike against the brutal treatment of the British officers” (as the ratings preferred to call it), came up. The full chapter on the Commission of Enquiry is produced below as an excerpt.

Two months after the surrender, a Commission of Enquiry was announced. This turned out to be just a smokescreen for displaying the so-called British sense of fair play and an attempt to cool the political temperature. It served more as a political tool than a judicial enquiry.

The mutiny was discussed in the Central Legislative Assembly on 22 and 23 February and by the Defence Consultative Committee on 8 March 1946. The navy had already appointed boards of enquiry to study the events at every individual establishment and ship in detail.

At this 8 March meeting the C-in-C of Indian armed forces, Claude Auchinleck, announced that he would recommend that the Government of India appoint a commission to enquire into the causes and origin of the mutiny.

Following this, an announcement was made by the Government of India in early April. ‘The Central government has been pleased to appoint a commission of enquiry to enquire into and report on the causes and origin of the recent mutinies in the Royal Indian Navy in February 1946.’

The Commission of Enquiry would have as chairman, the Honourable Sir Sayyid Fazl Ali, chief justice of the Patna High Court (Judge, Supreme Court of India [1951–52], later Governor of Orissa [1952–56], and Assam [1956–59]). The judicial members were Justice K.S. Krishnaswami Iyengar (chief justice, Cochin State), and Justice Meher Chand Mahajan (Chief Justice, Supreme Court of India, January 1954 to December 1954; prime minister Jammu and Kashmir [1947–48]; judge, Lahore High Court). The service members were Vice Admiral W.R. Patterson, Flag Officer Commanding, Cruiser Squadron in the East Indies Fleet and Major-General T.W. Rees, Indian Army, commanding the 4th Indian Division.

The secretary to the commission was Lt Col Visheshar Nauth Singh. Sardar Patel and Aruna Asaf Ali asked the well-known Bombay lawyer, Purshottam Tricumdas, president of the Ex- Services Association, to appear on behalf of the Congress Defence Committee.

It was decided that the proceedings would be public, unless the chairman decided that it was in public interest to hold some part in camera. A total of 229 witnesses were examined, and a large number of official documents were studied.

At Bombay and Karachi, members of the commission visited a number of naval establishments and ships to see their galleys and mess decks. They even tasted the food served to the ratings.

The commission held its first sitting on 18 April 1946 in Delhi. Its first witness was Lt Col. Malik Haq Nawaz of the Morale Directorate at the General HQ. He deposed that he saw seeds of unrest in December 1945, when he enquired into the state of morale of the officers and ratings in Bombay and Karachi. Along with Col A.A. Rudra, security liaison officer, who was the second witness, Nawaz admitted that racial discrimination and political awakening were the primary causes.

The proceedings of the committee were, like the INA trials, open to the public, but it turned out to be a prosaic affair by comparison to the dramatic INA trials. The commission concluded its sitting in Delhi on Saturday, 27 April. It moved to Bombay on the 2nd of May, where it sat on the third floor of the Bombay High Court.

The witnesses included the FOCRIN, Admiral J.H. Godfrey, who was examined on 22 April 1946. He was memorably pulled up by Justice Sayyid Fazl Ali when he contended, ‘But in this country where there is nothing like public opinion, not one word has been raised against this (ratings’ complaint of bad food)’. Hearing this, Justice Fazl Ali replied sharply, ‘I consider the statement made by you ill advised. Aren’t you prepared to revise your opinion?’ The admiral apologized.

Speaking about the causes of the mutiny itself, Admiral Godfrey contended that left-wing Congressmen and Communists had considerable influence on the RIN ratings and this, along with the strong political spirit among many of the ratings, were the root causes which eventually led to the mutiny. The FOCRIN contended that media too had played its role with papers such as the Free Press Journal promoting anti-British feelings.

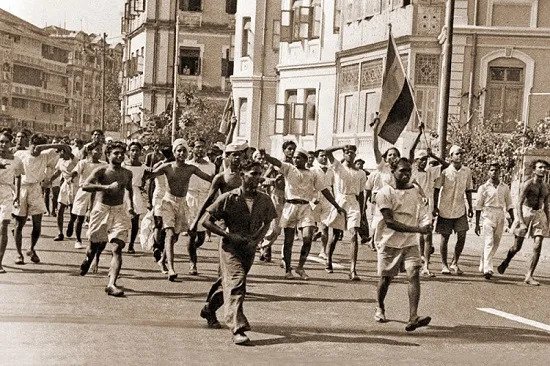

Ratings arrested credits https://news.abplive.com/blog/militants-strike-britain-out-the-1946-naval-indian-mutiny-1513953

Questioned about his controversial broadcast that had enraged the ratings to boiling point, Admiral Godfrey said that the broadcast was directed mainly at the mutineers in Bombay who had their guns trained on barracks and other establishments, and not towards the other ratings. He contended that such actions warranted the use of force and it was for this reason that large military forces were deployed in Bombay, along with two squadrons of Mosquitoes.

The atmosphere within the courtroom was very tense as Admiral Godfrey’s testimony continued through the day. He remained unapologetic about his actions, as he believed that force was the only means he had at his disposal to get the ratings to surrender unconditionally. At the same time, he expressed his regret that the RIN men had been made to return their kit when they were demobilized. This was not in the tradition of the British Navy, he admitted.

It was clear from Admiral Godfrey’s tone that he and other British officers firmly believed that the mutiny was pre-planned. How else could the ratings have had Congress, Muslim League and Communist Party flags at hand when they hoisted them on all the ships and shore establishments and lorries used by them? These flags were not on the ships, or readily available.

Admiral Godfrey also pointed that in Bombay there was a very good wireless organization between the shore establishments and ship-borne mutineers, which must have taken some time to work out. As a result, the HMIS Chamak in Karachi was ready for mutiny and only waiting for a signal from Bombay.

On their part, giving evidence few days later, the RIN ratings and others pointed out several fallacies in Admiral Godfrey’s testimony. They continued to emphasize that it was not a mutiny, but a mass strike against brutal treatment by the British officers, who routinely called them ‘bastards’ and assaulted them if they complained. Often, they claimed, the officers got drunk and slapped and kicked ratings who could not hit back.

Kusum Nair had been part of the uprising, albeit clandestinely. On Saturday, 27 April 1946 the Bombay Chronicle published a syndicated column under her pseudonym ‘Birbal’, which ridiculed Admiral Godfrey for saying that terrible food was not one of the causes of the mutiny.

The column also questioned Colonel Malik Haq Nawaz’s contentions that some of the most senior and outstanding leaders of the strike were Muslims, and said communal and provincial unity and harmony was one of the most marked features of the strike. Condemning the summary trial and sentencing of the ratings it alleged that the British put pressure on the police to forcibly put them on trains under custody, and then put them in jails of the respective districts to which they belonged. This was to ensure that these ratings could not depose in front of the commission.

On a lighter note, some of the ratings complained that while British seamen of Royal Navy were allowed to smoke on work, and take girls on dates outside the barracks, Indian ratings were punished if they ever dared to do that.

One of the early witnesses in Bombay, when the commission started its hearing on 2 May, was Lt Surendra Nath Kohli, who later become chief of naval staff. Well-built and smart, Kohli had joined the RIN in 1936 where he began his initial training in England and joined Talwar on 4 February 1946, barely a fortnight before the strike began.

At the time of the mutiny, he was the chief instructional officer. Thus, he was well-positioned to give an assessment of the state of the ratings’ minds before the mutiny. Cross examined on the first day, Kohli stated that he was one of the officers who had made reports about the mutiny to the CO.

Asked as to his opinions to the causes of the mutiny, he pointed to the officer and rating ratio. While there were 1,150 ratings in Talwar, there were just ten executive officers. These officers were technically qualified but lacked experience of sailing and administrative abilities to keep in proper touch with the ratings. More than double the number of officers was needed to maintain morale at the Talwar.

But this, he said, was a long-term problem and not the proximate cause.

Kohli believed the immediate trigger points was the arrest of B.C. Dutt, Commander King’s use of foul language, and the uncertainty caused by a poorly managed demobilization.

Some of the exchanges went like this:

Mr Justice Mahajan: We have been told that some of the British and Indian officers were having drinks and dances at the time these complaints (inedible food) were lodged. Is that correct?

Lt Surendra Nath Kohli: That is true. In the ratings’ club, though the dances are completely prohibited.

Justice Mahajan: Would you regard the arrest of Dutt for shouting ‘Jai Hind’ justifiable?

Kohli: If ‘Jai Hind’ is said to mean ‘Long Live India’, I feel his arrest was unjustifiable.

Kohli also agreed with the commission member, Major General Rees, that the more educated ratings were highly motivated and influenced by politics.

On Friday, 3 May 1946, Chief Petty Officer Sher Alam, master of arms at Mulund and drafting master of arms at Castle Barracks was the first witness. He was asked frivolous questions like, ‘I believe you are a chain smoker and that you spend as much as Rs 30 per month on smoking. How would you manage when you resign the service?’ His simple reply was, ‘Yes it will be difficult for me to maintain the same standard.’

Another leading telegraphist, E. D’Cullie narrated an incident when a telegraphist, fed up of constant abuse and ill treatment in Talwar, had committed suicide by hanging himself from a tree.

From Bombay the commission went to Poona and visited HMIS Shivaji at Lonavla, where 900 trainees had gone on strike in support of their brethren. On the way, they also inspected HMIS Akbar at Thana. After the weekend, the committee returned to Bombay where they interviewed more ratings.

Among them was nineteen-year-old P.G. Bokle, a Saraswat Brahmin who complained that when he joined the navy his sacred thread (janeyu) had been cut off as he was told that in the navy no rating could wear the thread. Bokle also claimed that he was called an ‘Indian bastard’ on many occasions by British officers.

In a startling statement on Thursday, 9 May 1946, Lt Mahendra Pal Singh of the HMIS Clive, a training ship in Bombay, contended that the COs of various ships on hearing the first rumbles of the mutiny became ‘funky’ and ran away from their posts ‘to rest in peace and return after a couple of days.’ The officers did not bother to show leadership but instead were content to hide themselves in the confines of the nearby Sea Green Hotel on Marine Drive.

Asked if the situation that first took place aboard the Talwar could have been averted, Singh said it could have been. ‘The situation in the Talwar would have been averted if the authorities had sent officers who had the confidence of the ratings to handle the situation, such men as Lt Hassan or Lt Batra. But instead, they sent Lt Kohli and Lt Nanda, who were hooted out by the ratings.’

‘It is my personal opinion that when officers became unpopular there is something definitely wrong with them.’ He added: ‘The allegation that the strike was pre-planned was totally untrue.’

He also denied that the Congress and League flags that were hoisted on the ships and establishments during the mutiny were purchased from the market. He deposed these were made on the ships itself, from parts of other flags. All the posters that were seen were put up only after the mutiny had started.

Another Indian officer, Lt Ghatak, speaking from his personal experience said: ‘Although the Indian and British officers messed together, British always sat on one side.’ Excessive drinking and disorderly behaviour under the influence of liquor brought the officers into contempt with their men. Dances and parties had often been the subject of derisive comments among the ratings.

Testifying in Bombay on Monday, 13 May 1946, a leading telegraphist bitterly complained about the medical officers who instead of taking care of the ratings ended up harming and even getting them killed through sheer callousness. Giving the example of a deceased rating, Gulam Hussein, he stated that Hussein had complained of acute abdominal pain to a doctor who instead of giving him medicine advised to take a swift run around the courtyard. Putting faith in the doctor’s ‘prescription’, Hussein ran around once and then dropped dead. But his death did not change the attitude of the doctors.

The most startling testimony the commission heard was probably from Ahmed K. Brohi. A customs clerk before he joined the navy as a telegraphist, Brohi was arrested as soon as the mutiny ended and first put in Mulund camp before being transferred to the dreaded Kalyan camp.

Termed one of the kingpins in the RIN Mutiny as joint secretary of the NCSC, Brohi appeared before the commission in a dark brown jacket and white shorts, sporting a small unkempt beard. Calm and collected, Brohi spoke in a low determined voice which made his testimony all the more compelling.

‘Have you ever noticed why we like to read Russian literature or why communism is spreading in India at atomic speed? Why do we not read instead French literature? We are not revolutionary because we have fallen in love with the reds of Moscow but because we know they are the staunch enemies of your system of government, which has proved to be a second edition of Nazimrule.

Our aim, ambition, and future policy is to revolt against British imperialism.’

Naval Uprising Memorial, Bombay, Credits- Wikipedia.

Questioned by the committee as to the strike and his role in it, Brohi had this to say.

Q. Did you know that the strike was to begin on the 18th of February?

A. I knew only by intuition, it was only an accident that the strike occurred that day. In my mind, the 17th of February has got some association. On that date in 1942, 30,000 Indian soldiers were handed over to the Japanese in Singapore by their British colonel. That made me think it had something to do with INA. Yes, some INA literature was distributed among the ratings.

When asked why he did not report his misgivings to higher authorities, he replied, ‘I am not a member of the CID.’ During his testimony, Brohi read out a long statement to the commission, which was termed as a ‘fine essay’ by the chairman, Justice Fazl Ali.

In his written statement, Brohi said the main causes for the strike were: the INA trials, disappointing demobilization conditions, hatred of the British, the Indonesian issue where Indian ratings were reluctant to fight for the Dutch colonizers agains the Indonesians, the RIAF strike, free availability of communist literature, and press propaganda regarding disturbances specially in Calcutta, loose discipline in HMIS Talwar, and the abusive language of Commander King.

Impressed by his statement, Justice Fazl Ali asked how long it took him to write the statement. Brohi’s short reply was: ‘Six hours.’ Speaking during his cross-examination, Brohi said, ‘Mischiefmongers among the RIN strikers in February last, signalled to ships in Bombay harbour to open fire, and if the men on the ships had done so thinking that the instructions had come from responsible persons, terrible havoc would have been caused.’

Purshottam Tricumdas then asked him for further elucidation of the statement to which Brohi replied that he was referring to some signals given from the Gateway of India and Ballard Pier to ships to open fire.

Confirming what others had said, Brohi also categorically stated that 99 per cent of the ratings were interested in politics, and bore deep hatred against the British. They also felt that like the INA personnel, they wanted to do something outstanding for the country.

Brohi went on to blame national leaders for misguiding the ratings by preaching non-violence to men who had been taught to fight. So, national leaders were responsible in a big way. ‘Till the moment the ratings took up the arms, the national leaders were red hot in their speeches. But when the ratings actually took up the arms, what did they find? The leaders began to talk of non-violence. How could men trained in warfare think in terms of spinnin wheels? How could men taught to kill take up the charkha?’

During cross-examination, Brohi contended that despite everything the strike would have remained peaceful if the British had not pushed the men into taking up arms.

He pointed out that the British had imprisoned B.C. Dutt and R.K. Singh – heroes to many of the ratings. He added, ‘Government forced them to take up arms. They imprisoned their brothers. They stopped the water and food supply. The ratings therefore had no other way but to take up arms. Admiral Godfrey made his threat to sink the navy and this made the ratings adamant. I do not mind what will happen to me in the future, whether I live or whether I receive bullets in my chest, but the butchering of so many of my comrades will ever haunt my memory in days to come.’

On being asked by Justice Mahajan which newspapers incited the mutiny, he named the Free Press Journal, the Bombay Chronicle, and Blitz. ‘The ratings were dead against imperialism. Indeed, British imperialism was a second edition of Nazi rule. Hence the ratings looked for a friend, everybody who was anti-imperialist. They know of the historic Mutiny of 1857.’

Basant Singh, one of the ratings transferred to and detained at the Kalyan camp, deposing in front of the commission on 14May, stated: ‘Some kind of matters and literature about INA, Subhas Bose’s pictures and pamphlets such as “Blood and Thunder” were freely distributed among the ratings. The situation in India was peculiar. Political prisoners had been released, INA trial had started. In some respects, we became jealous of the INA deeds. They are being worshipped as heroes. But we are looked down upon as British stooges and despised. We too are patriots. We wanted to make clear to the public what we wanted to do and we struck work.’

The other notable witness after this was B.C. Dutt, the man who had started the mutiny by writing nationalist slogans on the walls of the Talwar. Testifying before the commission, Dutt described serving in the naval service in India as a ‘living hell’.

Dutt claimed that he was disillusioned by his life in the navy and wrote of this in a letter to his brother, which was found and heavily censored and he himself was threatened with dismissal. A diary seized from Dutt’s locker in the Talwar was produced in the court. It contained references to a ‘boss’, ‘HQ’ and to a ‘Whisp Camp’. The last, Dutt explained, meant ‘Whispering Campaign’ and referred to his effort to educate other ratings.

Dismissing the charges of mutiny, Dutt claimed that he was charged with political affiliation solely because at the time of his arrest when his locker was searched, a communist book was found. British records reveal that when Dutt’s locker was opened and searched, a number of articles and papers that included two diaries, a receipt for Rs 206 from Azad Hind Army Relief fund, a copy of INA pledge and a book on the Indian Mutiny of 1857 by Asoka Mehta, and a letter on a postcard from the secretary of the Indian Ex-Services Association Y.K. Menon were found. Clearly, this was all much more than just a ‘communist book’.

During his testimony, Dutt refused to answer questions on a few occasions saying he had already stated the answers before the Board of Enquiry, which had inquired into the Talwar incident. However, he was more forthcoming on his political beliefs. On being asked when he gained a liking for political activity, Dutt replied that after joining the navy he had the opportunity of visiting places, mixing with British soldiers and seeing how people lived in free countries. That is how his interest in politics began.

‘When Indians are struggling for freedom, I think every Indian should join in the struggle… I would have joined the INA, if I was in Malaya.

Balai Chand Dutt, Credit- Twitter

Questioned about his views on the ‘Azad Hindis’ and the fact that they were referred to as ‘Dutt and his group’, Dutt had little to say. The question was: This cadre (Azad Hindis) would join no political organization but would infiltrate into all services. Do you agree with this?

Answer: ‘For the cause of freedom anything can be done.’

He did add, ‘I would take the Azad Hind Fauj pledge as all Indians should,’ and he pointed out that all the ratings had contributed to the INA fund. He was however, quick to emphasize that the mutiny started in spite of him, as he was under detention on 17 February.

While Dutt was most forthcoming about his interest in politics, he was understandably less so about the entries in his diary. When asked about his visits to ‘N’, and ‘HQ’, he purposely gave misleading answers stating N stood for Nambiar, who was not in Bombay, and not Lt Nayyar, and HQ stood for the Headquarter of Communist Party on Sandhurst Road (and not to any headquarters of any secret organization). In reality this was the Riviera, Marine Drive home of Kusum and P.N. Nair where all the planning for the mutiny was done.

Q. Do you remember that you gave a book called March of Events to Rishi Dev Puri?

A. I had some books at the signal school and sometimes he used to give me one or two books, but I can’t remember what happened to this book. So many things have happened after that.

Q. On 3 January you entered in your diary: ‘Went with Devu to HQ.’ May I suggest that it was Lt Nair’s flat?

A. No.

In this way, Dutt continued his bid to mislead and stonewall the commission. When asked about the ‘Whisp Camp’ reference in his diary, he said it meant ‘whispering campaign’ which was to educate some ratings about the history of the Indian National Congress and not to excite them. Asked about references in the diary to meetings with RIAF men, Dutt explained that these were made in connection with the formation of Ex-Services Association. In reality though, the British contended that Dutt was meeting them at the Nairs’ home in a bid to get them to support and join the RIN Mutiny. The material seized from Dutt’s locker was placed before the commission as exhibits.

As the cross-examinations continued, other interesting stories emerged. One of these was about Lieutenant J.A.G. Tottham who testified as one of the witnesses at Kalyan camp on 1 May 1946. In his evidence, Tottham related an incident, which highlighted the contempt and lack of trust the British held for Indians:

‘In the Persian Gulf one of our leading signalmen reported one evening at 5.30 p.m. that he had sighted three suspected German U-Boats. This was subsequently reported to the senior officer commanding at Bandar Abbas, who asked for the name, ranking and the ability of the rating who had reported. He was told “RIN rating, signalman of very good ability.” (On hearing that he was an Indian), we got back the reply, “Do not rely much upon RIN leading signalman’s report.” The same night, in that very area, three ships were sunk. The commander in the Persian Gulf stationed at Basra put an enquiry board on it and the officers in Bandar Abbas practically told us “to keep our mouths shut about the incident”.’

By 16 May, almost 100 witnesses, Indian and British, had been cross-examined. Another interesting witness was Commander S.G. Karmarkar who was transferred from an establishment in Lonavla to HMIS Talwar on 19 February after the outbreak of the mutiny. This was the Indian officer who had kept an eye on the Riviera ‘HQ’ from his flat in the same building. He deposed that there was no serious ground for the mutiny. The grievances and discontent, he claimed, were not of a serious nature. He blamed political influence for the mutiny. He said he believed the prime cause was acute political tension in the country.

Karmarkar added that the other trigger was the effect of articles published in newspapers. He admitted that he had got threatening letters from the ratings stating that if he did not mend his ways of siding with British officers, they would ‘make Commander King out of him’.

He admitted that when in Bombay, he stayed in a building at Marine Drive. ‘Until recently Mr Nayyar, formerly a lieutenant in the navy, lived in the same building, and he noticed that ratings visited Nayyars.’

Despite his full support to the British and the navy, he said: ‘Alleged abusive language of Commander King was another incentive for the Mutiny.’ He also admitted that the effect of Admiral Godfrey’s threat to destroy the navy was unfavourable.

There were some lighter moments when Karmarkar was cross examined.

Justice: You said that the WRINS (Women ratings of Royal India Navy) had preferential treatment.

A. Fortunately I had nothing to do with WRINS [laughter].

Tricumdas: Is it wrong on the part of the ratings to meet a politician?

A. It depends upon the type of political leaders he meets [laughter].

Q. You met Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. Is Pandit Nehru a safe person? [Laughter]

Karmarkar did not reply.

Q. When you met Pandit Nehru, was a British intelligence officer with you? A.

You may ask Pandit Nehru himself [loud laughter].

Captain Inigo-Jones was the CO of the Castle Barracks until 18 February. On the 18th he was sent to the Talwar to take over from Commander King. He was described by a young rating before the commission as ‘Butcher of the RIN’. His testimony added some colour to the proceedings. Inigo-Jones repeatedly wore a monocle to read extracts from his statement made before the Board of Enquiry at the HMIS Talwar. When asked if he had made those statements, he replied, ‘I presume so.’

Lt Sachdev was a colleague of Lt Batra at the Talwar during the mutiny. Both of them were well-liked by the ratings as they were sympathetic to their grievances. Testifying before the commission he said, ‘It was the frustration of the ratings’ representation to the junior officers, and the frustration of the junior officers’ representation to the authorities, which suddenly exploded into the Mutiny.’

* * *

The most striking testimony from the British officers’ side was that of Commander Frederick William King, CO of the Talwar until 18 February. Giving his testimony on Monday, 20 May 1946, King denied his use of foul language was one of the reasons for the mutiny, and denied having used any foul language at all.

He asserted that there was not just the political but revolutionary movement behind the mutiny. ‘Unfortunately, navy was not in a position to show them the other side of the picture.’ King said the revolutionary fervour only grew especially when on a particular day the ‘Quit India’ slogan was found written on his motor car and the tyres deflated. He regarded this as a serious act of sabotage and consequently tried to get the number of ratings reduced.

Replying to a question if he knew any of those fourteen ratings who had complained against him, King replied that he did not remember having seen any of them. When asked if his administration had through being over-strict, created resentment, King replied that the ratings themselves had his deepest sympathy, especially Dutt who was very clever and who would do credit to any navy.

‘Most of the complaints against me were influenced by outsiders. I tried to call them to my office but it’s very different when there are a large number of men involved and they are refusing to take orders from their immediate senior.’

Q. It has been stated in the evidence before us that when you came to know of the trouble, you gave no instructions to the officers.

A. All that is in the report of the Talwar enquiry. When I came to know of the trouble, I visited Vithal House. I saw the admiral there. He did not give me any instructions. He may have said, “Try to get hold of the representatives of the ratings” and that is what I have been trying to do.’

Q. You stated in the Talwar enquiry that some catcalls were made against the WRINS. What were they like?

A. I can’t imitate the calls.

Q. What was the implication behind them?

A. It was embarrassing for the women – bad discipline and bad manners.

When Chairman Fazl Ali asked if the accusation that he was accustomed to using bad language was correct, King replied he sometimes used ‘friendly language to his friends’.

Q. Which may not be parliamentary?

A. May not be.

Fazl Ali: You cannot categorically refute that you use language that may not be parliamentary, and may be misconstrued as bad language.

A: I use words occasionally which are not in the dictionary. Some words are more expressive.

Sayyid Fazl Ali then read out a statement by Lt Nanda before the Talwar board of enquiry which stated: ‘Have had quite a lot of conclave (sic) with Commander King. I have heard him very often use bad language, which comes to him unintentionally. Commander King explained he sometimes expressed himself freely.’

Testifying next before the commission was Lt S.M. Nanda (then a divisional officer in the HMIS Talwar, and later the navy chief). Lt Nanda stated that he had gone to Vallabhbhai Patel during the mutiny and gathered from him that Lt Nayyar and Mrs Aruna Asaf Ali had approached Sardar Patel to get the support of the Congress for the mutineers and that they had been disappointed. He also stated that ratings wanted Mrs Asaf Ali to mediate between them and the authorities.

Speaking in support of Commander King, Lt Nanda categorically said ‘No’, when asked if Commander King’s statement that ‘ratings would not mind overcrowding if they got good food’ was indeed true. On the actions of mutiny, he was more forthcoming.

Lt Nanda emphatically said that the writing of slogans in Talwar on the eve of Navy Day was not the work of certain disgruntled ratings. ‘It was the work of some organized body which was trying to disrupt the discipline of the establishment in general, and to rouse feelings against the government and to magnify the service grievances.’ He also emphasized that the presence of revolutionary elements in Talwar was well known.

‘On the Navy Day the slogan writing was in full form and the officers were quite handicapped on how to put a check upon it. The indifferent attitude of the authorities towards the hunger strike at two messes added fuel to the fire. Lt Cole and myself volunteered to speak with the ratings. I asked the ratings that the authorities wanted to know their grievances. I also asked them to appoint representatives from amongst themselves, but they resented the idea and expressed a keen desire to have some national political leader represent them.’

Members of the Ex-Services Association, the organization accused of having political affiliations with the mutineers, also came forward to testify before the commission. It was here that Lt Commander Powar, a member of the commission, who was said to be a British sympathizer, began aggressively cross-questioning the witnesses.

Lt Powar asked Lt Nanda if a rating in the Talwar named Rishi Dev, was related to Lt Nayyar, an officer in Talwar. To that Justice Mahajan interrupted that Rishi Dev was a Puri, a Punjabi Brahmin (incidentally incorrect because Puris are Punjabi Khatri) and that Nayyars came from South India (also incorrect because this Nayyar was also a Punjabi). This remark led to some laughter in the court. Lt Cdr Powar sat down, protesting that every time he puts a question, he is ridiculed.

The next interesting witness was an officer of the Indian army, Lt Sachdev. The commission first asked whether he was a member of the Ex-Services Association and then read out a resolution passed by them on 20 February 1946 supporting the mutiny. Did he, they asked Lt Sachdev, know of this resolution? If so, did he condone it?

In reply Lt Sachdev said he was a member of the association but did not support this resolution. He was then asked.

Q. Who took you to the meeting?

A. I was told by Lt Commander Arland to go over there.

The commission then drew attention to the picture published in the Blitz. It was a picture of Jayaprakash Narayan with Lt Chandramani of the RIN, while contingents of the three Indian services gave the guard of honour.

Asked for his comments on the picture, Lt Sachdev simply replied, ‘I want to keep aloof from the party politics.’ Sachdev continued to play this game of cat and mouse until finally a question came up that ended all doubts about his loyalties.

Q. Do you realize under what government you are serving?

A. Yes, it is the British government of which we are all slaves… We are ruled by the Britishers as slaves and I do mean what I say.

Y.K. Menon, secretary of the Indian Ex-Services Association was the next important witness to be cross-examined. He described himself as author, journalist, correspondent of many foreign papers and contributor to the Tribune (which until recently had been associated with Sir Stafford Cripps). During his cross-examination, he mentioned that the association was mainly concerned with the resettlement of discharged servicemen and it would be wrong and libellous to say that one of its objects was to subvert the loyalty of people in the armed forces. There was no political tinge to the association.

Menon also pointed out that the association was formed on 20 February, which was after the mutiny had already broken out and that the resolution passed by the association to congratulate the strikers was not political but a humanitarian one. It should be viewed in that context.

He explained that the first meeting of fourteen persons was held on 17 December 1945 to consider a Draft Constitution. After four such provisional meetings, the association came into existence on 20 February 1946, when a resolution expressing sympathy towards the RIN strikers was also carried by the house. He said the association had almost 1,000 members in Bombay alone.

Both Tricumdas and Menon put up a strong effort before the commission to prove that the Ex-Services Association was not a political body and not responsible for the RIN Mutiny. They cited examples of other organizations such as the Indian Merchants Chamber, the Forward Bloc, British Portuguese Chamber of Commerce, and other important organizations, which were represented by well-known members of these bodies when they conducted a joint meeting.

Dr P.A. Wadia, a noted economist, was present as well in this 20 February meeting, where Mrs Lilavati Munshi was in the chair and a small committee was formed to collect funds. Some other prominent people who attended the meeting were Mr Gazdar representing the Tatas, Mrs Violet Alva of the Forum, wellknown actor Prithviraj Kapoor, and Miss Lynette Solomon of the Bombay Sentinel.

It had been decided that Jayaprakash Narayan should be invited to inaugurate the fund and Tricumdas mentioned that it was recommended that the association should seek support from the government of Bombay and the collector of Bombay. He even suggested that it should work hand-in-hand with the district sailors, airmen and soldiers’ association of which the collector was the chairman.

Menon denied that the association in any way was political in nature and that it had any hand in the mutiny though there were many members who had associations with the navy. Tricumdas added that the Ex-Services Association was moved by the pitiable condition of the demobbed soldiers and navy men. It was with the intention of doing some good for them that the association was formed.

Judge advocate Powar asked Menon: ‘If non-violence were to fail would you believe in violent methods?’ Without even a hint of hesitation, Menon answered, ‘I would,’ and emphatically added that he would adopt any means to get freedom. He, however, denied that he knew Dutt before the mutiny nor could he single him out in a crowd. Menon admitted, however, that he did know R.D. Puri.

The next witness was Prem Nath (P.N.) Nair, or Nayyar. Formerly a welfare officer in the HMIS Talwar, Nayyar stated that he joined the navy ‘as he loved the sea’ but left it when he found that conditions there were terrible.

‘I have never seen more callous people who have utter disregard for human sentiments as in the navy,’ he shared. However, he denied taking part in any subversive activities saying such accusations were baseless.

Nayyar, however, was quick to point out the follies and discriminatory practices carried out by the British. Talking about racial prejudice, he said that a young British officer, Lt Horabin, who was a favourite with everyone in the Talwar, fell into disfavour after he married an Indian girl whom he loved. His wife was never invited to any of the naval functions or parties just because he had married a ‘black girl’.

Indian ratings during RIN mutiny, credits- https://www.newsintervention.com/a-mutiny-that-petrified-london/

By 23 May 1946 the commission had completed three weeks in Bombay and, according to local newspaper reports, its hearings were humdrum affairs. It needed Mrs Nair, the only lady witness to be called, to inject some excitement into the proceedings.

Smartly dressed, Kusum Nair’s answers delivered with quick confidence impressed everyone and she lent the commission an aura of glamour, which had hitherto been missing. One of the prominent visitors in the packed courtroom when she was examined, was Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, former president of the All-India Women’s Conference.

Describing herself formerly a member of the Women’s Auxiliary Corps (India) [WAC (I)] Mrs Nair also stated that she was a journalist and the owner of a newspaper syndicate company in Bombay. Asked for her views on the mutiny, she said the mutiny was entirely an internal matter, and credit or discredit for it should go to the ratings.

Then asked to account for her movements, she admitted that she was seen near the HMIS Talwar on 22 February, and at Castle Barracks and other places in Bombay during the days of the mutiny. But she said she went there only to fulfil her journalistic duties.

Reiterating the objectives of Menon, Kusum Nair said the common man felt that the armed forces should participate in the freedom struggle and added daringly that she believed that it was the patriotic duty of every Indian to fight for freedom. Though she denied knowing B.C. Dutt, she admitted she knew R.D. Puri.

Kusum Nair’s true sentiments came to the fore though when she stated that she felt sure that demobbed personnel would join the armed forces of free India at half their current salary. Questioned about a message attributed to her that the ratings should salute Azad Hind style, she denied it. She also admitted that an article ‘Indian Mutiny’ had been sent out through her syndicate.

No one could be in any doubt as to where her sympathies lay. Kusum Nair’s statements were all the more impressive given the cross-examination that Lt Commander Powar the judge-advocate, and a supporter of the British, subjected her to.

He pointed towards her writings in an INA pamphlet, ‘Even the armed forces are in a ferment.’ She replied that she was referring to the RIAF strikes, the arrest of B.C. Dutt, and the statement to that effect by Auchinleck in the Assembly, concluding: ‘I hadn’t the faintest idea that there would be widespread trouble in RIN.’

Powar, however, was determined to drive her to admit that she had full knowledge about the strike from beforehand. However, she was unperturbed. Being asked by him about a quotation in a piece distributed under her pen-name Birbal, which said: ‘Just wait for the next struggle. The fighting forces will walk over next time,’ she replied with authority, ‘This is an assurance to the Congress leaders that the armed forces are with the country… If there is a mass uprising, I think every Indian should participate in the struggle.’

However, Powar was not done yet. He then asked her, ‘Were you in sympathy with the strikers?’ a dangerous and leading question. Circumventing it with ease, she said, ‘I tried to do my best to help the situation. I even went personally to Sardar Patel and persuaded him to use his good offices with the authorities and with the boys to stop it.’

Kusum Nair was a rock-solid witness on the stand. None of the commission’s questions could shake her. On being asked accusingly by Vice Admiral Patterson that if she agreed, or was willing to concede that a reading of her political views in print would weaken the loyalty of the armed forces, and might have incited the mutiny, she replied firmly in the negative. She also said she believed that the mutiny was a spontaneous action by the ratings themselves.

‘No political organization could have commanded the mutiny. If an organization like the Indian National Congress could not influence the Muslims during August 1942 (Quit India Movement), when there was a spontaneous action and mass upsurge all over the country and even the army remained aloof from the struggle, how could outside political influence have any affect during February 1946, when the international situation was far more favourable to the government than in 1942?’

* * *

Everyone was most interested to hear the testimonies of the mutineers themselves. The commission cross-examined Lt Sobhani, the only officer to be arrested and punished for ‘making seditious speeches’ and ‘inciting other fellow officers’. Facing court martial on twelve charges, he was brought from a naval prison to appear before the commission under guard. Asked about the causes for the RIN mutiny, Subhani said that strike was due to long frustration among the ratings.

The newspapers gave wide coverage to the Commission of Enquiry proceedings and revealed some interesting sidelights. The column ‘Twilight Twitters’ (Bombay Sentinel, 17 May), was ironical. ‘You will hardly believe – That Ahmed Brohi told RIN Court that politics was a vast and confusing subject. Who said it was also the last refuge of a scoundrel?

‘That Telegraphist Brohi told the commission that as it was accustomed to deal with criminal cases, it suspected everything under the sun. Another way of saying a man is known by the company he keeps?

‘That the witness informed the judges if he had good memory, he would have been the premier of some province. Brohi should know that Premiers have short memories, as they forget their election promises.’ The commission concluded its last hearing on Saturday, 1 June 1946 in Karachi after five consecutive days of sitting in Muslim Hostel. It examined over forty witnesses there, including two COs, and three other officers. Commander A.K. Chatterji, CO of Chamak was the first witness on the last day, and the last to be examined was Jaswant Singh, a rating who was discharged and had recently emerged from jail after serving a term of imprisonment.

After concluding the cross-examination in Karachi, the commission left for Simla on Tuesday, 4 June 1946, to draft the report. It was expected that the report would be submitted to the government within a month. The report was duly submitted in October but it was not made public until the third week of January 1947. Even now, it’s not entirely clear if the full report has been placed in the public domain, although 598 pages of it are available.

The Times of India and other newspapers carried excerpts from the report on 21 January 1947. Wrote the TOI: ‘The lessons of the mutiny, the government say are, first, that officers must consider the welfare of their men before their own comfort or safety and that grievances must not be explained away but redressed and, secondly, too rapid an expansion without proper provision for the training of officers is unwise, and the aim for the services in peace must be to prepare for expansion in war. ‘

The government mentioned that the inquiry commission is unanimous that the basic cause of the mutiny was widespread discontent arising mainly from a number of service grievances which had remained un-redressed for some time and were aggravated by the political situation.

‘With references to politics, the Government of India expresses their belief that healthy interest in the affairs of the country is to be encouraged but that the use of politics as a lever to get the grievances redressed is highly dangerous and must be discouraged in the interest of the service.

‘Officers and men are being instructed that although every man is entitled to his personal views, participation in party politics is not admissible to members of such a service.’

The report stated as follows: Nine ratings, one officer, killed (34 were missing and reported as deserter), 41 ratings and one officer wounded. [Looking at the scale of mayhem this appeared to be highly understated data.]

It further concluded

1. Mutiny was not organized by outside agency. It was not pre-planned.

2. Politics and political influence had great effect in unsettling the men’s loyalty and in preparing the ground for the mutiny and its prolongation.

3. The glorification of the INA had undoubtedly the most unsettling effect on the morale of the men of the services.

4. The mutiny never assumed the shape of a political revolt.

5. Naval authorities did not take more active steps before the mutiny.

6. FOB Rear-Admiral Rattray did not step in over Commander King’s head on hearing of the complaint about his conduct.

7. The duty officer in Talwar did not take active steps on 17/18 February over food and did not bring the grievances to the attention of Flag Officer Bombay.

8. There was indecision and inaction on the part of Commander King.

9. There was delay in taking action on 18 February by FOB, CO and other officers.

10. FOB Rattray failed to isolate Talwar and prevent rumours, which often becomes news and did not prevent news from travelling.

‘It seems to us,’ the commission said, ‘that but for these mistakes this great catastrophe which caused so much damage, suffering and bloodshed, which has ruined so many young lives and careers which have left so much unhappiness and bitterness in the services would not have occurred.’

The naval authorities, as a result of the report issued the following instructions:

1. European officers will be encouraged by all means to acquire a full knowledge of their men not only in the services but in their homes too.

2. Everything possible is being done to eliminate any suspicion of racial discrimination and Indian officers are being posted to the command of the ships or to posts of executive officer in ships, and to higher staff appointments, as they acquire sufficient seniority and experience.

The Free Press Journal of 21 January 1947 carried the headline ‘ALL STEPS TO REDRESS GRIEVANCES of RIN, Government Assurance. FORGET THE PAST NOW AND LOOK TO THE FUTURE…’

The FPJ further added that only Indians should be selected for permanent commission and the present naval canteens should be improved in India. It also deplored the fact that the report ignored the victimized men.

‘The Report may have generally satisfied the Navy but has been severely criticized by the officers for recommending nationalization of the navy. The ratings, and ex-ratings are unhappy and despondent over non-references to the “victimized young men called as mutineers” and that they are not in general viewed favourably by the men of the navy.’

Aruna Asaf Ali criticized the report, ‘The interim government’s steps to implement the recommendations have curiously enough the white man’s touch about them. There is surprisingly enough no reference to measures for reinstating of ratings discharged for mutiny… The tragic chapter in the RIN history could very well have become grim if the ratings had continued their resistance. They surrendered only after they were assured by eminent leaders now in the interim government that no vindictive action would be taken against them. Many were court martialled and many more were dismissed summarily.’

Aruna also added that the commission’s conclusions suggest that the causes that led to RIN revolt were related to genuine grievances.

‘This justification is further upheld by the government’s somewhat reluctant admission that the mutiny “may not be entirely without good results”. After having realized this, to ignore the men who risked their lives to revolutionize this denationalized branch of India’s fighting services is to submit to the arguments of the White bosses of India.’

She further said, ‘Left to himself the British Admiral would not have hesitated to destroy the entire Indian Navy for reasons of prestige. …or again to be apologetic about these individuals who owing to war and post war strain acted mistakenly.’

In a narrow sense, the enquiry did lead to better service conditions for Indians on other ranks in the RIN. But it ignored the way in which the ratings had been mistreated, imprisoned and summarily dismissed, without receiving their dues.

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of Roli Books. You can buy 1946 Royal Indian Navy Mutiny: Last War of Independence, here.

Founder and publisher of Roli books started in 1978, Pramod Kapoor is one of the leading names in the Indian publishing industry. He has been honored with the prestigious Chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur for his enormous contribution to publishing path-breaking books. His 2016 book “Gandhi: An Illustrated Biography” has received international acclaim. An awardee of the Mahatma Award 2021 for lifetime achievement in publishing, Pramod Kapoor has been the face of change in the world of publishing.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply