Hanumangarhi

Ours is a nation of a fractured past. Of fissures that cannot be wished away by their overlooking, yet ones that risk being widened by those driven by dangerous ideas. These fissures need to be identified, studied and understood, in order to enable their filling.

A reviewer has called Valay Singh’s Ayodhya: City of Faith, City of Discord “a must-read for scholars who wish to explore the politics of Hindutva”. But it is more than that. A comprehensive and meticulously researched history of a city that goes back nearly 3,300 years in time, the book identifies the history of Ayodhya as “a microcosm of the history of the north Indian heartland”, a “history of the evolution of Vaishnavism in the Hindu consciousness” and “the formation and propagation of an aggressive Hindu cultural and religious consciousness that can be traced back all the way back to the advent of the East India Company”.

The chapter we have chosen to present here deals with the period 1800-1857. Through a painstaking perusal, selection and contextualization of primary sources from the period, Singh lays bare two essential truths.

One. Though the year 1855 is often cited as the year of the commencement of the Ram Janmabhoomi–Babri Masjid dispute, “the bloody conflict that took place was not over the supposed birthplace of Ram”. “It was over the Hanumangarhi temple and the claims by certain Sunnis that the Bairagis (adherents of the Vaishnava tradition) of Hanumangarhi had destroyed a mosque that existed atop it.” On 28 July, 1855, Maulvi Ghulam Hussein with – as per records – around 400 to 500 followers, charged on the 70 feet high Hanumangarhi (the temple sits on a hillock) from the Babri Masjid, located less than a kilometre away. They were routed by Bairagis, Naga Sadhus (also Vaishnavas) and Hindus from the surrounding areas who numbered “more than 8000”. Hussein and his followers retreated to the Babri Masjid, which was then attacked by the Bairagis. The British troops, 150 men with a few guns led by Captain Alexander Orr, for the most part, played witness to the carnage without intervening. Orr records that 70 of the Shah’s people were killed, and “as many perhaps or more of the Byragees and their allies”.

“In this way,” writes Singh, “the site of the Babri Masjid became embroiled in the dispute over Hanumangarhi.” A commission of enquiry comprising Orr, Raja Man Singh and Chukledar Aghai Ally Khan was constituted following this event. “Almost 150 years later,” Singh writes, “Another commission of enquiry would be set up by the Government of India, under its archaeology wing, but as we shall see, it would have nothing to do with Hanumangarhi or the alleged destruction of a mosque on it. In a remarkable diversion from the original, primeval source of dispute the masjid from which Captain Orr said the Muslims launched their attack on Hanumangarhi would become the site of the same claims and counterclaims.”

“In 1855,” Singh writes. “No extant British record of the Hanumangarhi conflict identifies the said mosque as Ram Janmabhoomi.”

The second truth that Singh’s research and presentation lays bare is more complex. Any dispute, more often than not, is about more than what the parties to it claim. Imagine then the number of layers hidden underneath a dispute such as the one that revolved around Ayodhya, which has reshaped our political landscape in recent decades and brought into question what concepts like ‘pluralism’ and ‘secularism’ mean for today’s India.

Singh’s historical investigation and dispassionate analysis complicates the simplistic narrative of a Hindu-Muslim conflict in 1850s Ayodhya. It does so by exposing the key political players behind the scenes, and their agendas.

First, there was Wajid Ali Shah, a Shia Muslim ruler presiding over a population that was two-thirds Hindu and which consisted of a large number of Muslims who were Sunnis. After the incident of 28 July, 1855, “given the rising anger in his Muslim subjects against the massacre of Muslims in Ayodhya, the nawab was worried about a backlash”. At the same time, as Lucknow Resident Outram reminded him, “the Hindu chiefs were powerful and would not remain quiet and unmoved if ‘the contest were renewed and any further outrages were committed on shrines which from time immemorial had been held by them as peculiarly sacred’.” Himself “avowedly irreligious and secular”, Wajid Ali Shah proposed a radical solution “that the King should build a mosque resting on one wall, but outside of the ghuree… and the dividing wall be so raised as to prevent either Moslem or Hindoos interfering with each other, or either party even seeing into the others’ place of worship”. There seems to have been no takers for this.

Secondly, there were the Sunni religious leaders Maulvi Ghulam Hussein, who had led the charge on Hanumangarhi, maulvis Ameer and Ramzan Ali of Amethi (the former led a second charge on Ayodhya but was intercepted before he got there), and maulvis Hafizullah and Nihaluddeen who led an independent enquiry which asserted that there had been a mosque at Hanumangarhi.

To understand this conflict, it is important to understand their dynamic vis-a-vis the ruler Wajid Ali Shah. “There existed a historical rivalry between the mostly Sunni Afghan-origin Pathans and the more recent arrivals, non-Afghani Shias,” Singh writes, “But more than anything it was the defiance of rulers by religious leaders that incited the conflict. Muslim religious preachers had started to blame the godlessness of the rulers for the enslavement by the British, and openly preached jihad.”

“Since the massacre by the Bairagis and their supporters—mostly men from neighbouring villages, the Muslims of Ayodhya had moved out to other safer places,” writes Singh. “At the same time, the news of this defeat was bringing in Muslims from neighbouring districts to Faizabad every day. The usually more hardline Pathans among them had united under the banner of two maulvis, Ameer Ali and Ramzan Ali of Amethi, who were now said to be marching towards Ayodhya.”

The fact that the findings of Hafizullah and Nihaluddeen’s enquiry were negated by the tripartite commission of Orr, Man Singh and Aghai Ally Khan aggravated the issue. Aghai Ally Khan was Nawab Wajid Ali Shah’s local nazim or agent of the district, and a Shia. “Hindus favoured a Shia over a Sunni member in the enquiry commission,” Singh writes. “And, as Captain Orr had believed, Muslims themselves being largely Sunni, did not trust Aghai Ally Khan because of his Shia persuasion.” At Asaf-ud-daula’s Imambara in Faizabad, neighbouring Ayodhya, the high priest, after Eid celebrations had “showered curses” on Aghai Ally Khan and “alleged that he, a Shia, had accepted bribes to favour the Hindus”.

Thirdly, there were the Hindu Bairagis of Hanumangarhi, preparing for further conflict after 28 July, 1855, “fortifying their defences and making small holes in the walls of the temple-fortress through which arms could be fired”. “The word on the street in Ayodhya, Faizabad and Lucknow,” writes Singh, “was that Hanumagarhi was also receiving aid from the kingdoms of Gwalior, Jodhpur and the local talukdars or chiefs of Awadh.” Information received by Outram listed Hindu chiefs willing to support the Bairagis of Hanumangarhi: “Rajahs of Bansee, Pyrespore, Ramnuggur, Dumeree, Souhan—Ranee of Dairwa— and Maharajahs of Gwalior and Joudhpore.”

In the commission, as mentioned, Hindus were represented by Raja Man Singh, who was in charge of Sultanpur, under which Ayodhya fell, and of whom Orr wrote that “his followers openly espoused the cause of the Byragees” and “his claims to impartiality must therefore be much questioned”.

Finally, the most strategic players in this politically religious drama were the British themselves, “the de facto rulers of Awadh”. Nawab Wajid Ali Shah was reliant on British forces to contain hostilities. Yet Governor General Lord Dalhousie wrote, from Calcutta, “the British troops ought upon no account to be moved to the assistance of the royal troops if hostilities should again break out at Awudh”. “Dalhousie seemed to have been hoping that Awadh would soon be engulfed in communal bloodshed,” Singh writes. “And to make sure it was not impeded by the interference of British troops, he directed his officers to stand by, just as they had done in July when Shah Ghulam Hussein had attacked Hanumangarhi.”

And why would Dalhousie be hoping for this “communal bloodshed”? The Treaty of 1801, gave the British control over more than half of Awadh’s richest cultivable lands in return for an annual stipend to the nawab of Awadh and an agreement to defend Awadh against external and internal aggressions. This had prevented the British annexation of Annexation so far. But, writes Singh, “In the event of the explosion of further violence between Hindus and Muslims, the British would have found a dramatic justification to annex the province.”

“The British were preparing the ground to annex Awadh,” Singh concludes. “And the Hanumangarhi incident was being woven into that plan.”

Yet, despite Dalhousie’s efforts at abstinence, things didn’t quite go according to plan. Wajid Ali Shah tried reaching out to Ameer Ali, who was marching towards Ayodhya, for a compromise. When this failed he issued a proclamation warning all who supported the maulvi’s crusade of “dire consequences”. Outram reported to Dalhousie two instances of landlords refusing to do so (“with the help of a large spy network, the British officers ensured that they were in step with the developments in the province”). He wrote in a letter dated 6 November, 1985: “the effect of the proclamation has been most satisfactory, scarcely an individual from the British districts [land ceded under the Treaty of 1801] having joined the large assemblages of Mahomedans or Hindoos which have been threatening the peace of Oude for some time past”.

A battle with British troops soon after, at Dhaurahra, left the maulvi and 400 of his followers dead. 80 men were killed from the other side.

It has now been nearly two weeks since the foundation stone laying ceremony at Ayodhya’s Ram Temple, where the Babri Masjid once stood. We have just celebrated our 74th Independence Day. Judgment for the demolition of the Babri Masjid is still pending.

It would be timely perhaps, at such a time, to read about events playing out in the Ayodhya of 1855 – in the lead up to our ‘First War of Independence’ – that mirror, to some extent, and link up, to some extent, with the tragic events and aftermath of 1992.

A glimpse of life during this period in Ayodhya is hard to come by, but rare interstices in the form of British gazettes give us fleeting insights. Published in 1828, Walter Hamilton’s gazette is devoid of any specific details. But it does capture the general attributes of Awadh—the province and Ayodhya. Written twenty-six years before the great rebellion of 1857 and almost an equal number after the Treaty of 1801, it describes the Hindus of the province as:

‘ …a very superior race, both in their bodily strength and mental faculties, to those of Bengal and the districts south of Calcutta… Rajpoots or military class here generally exceed Europeans in stature, have robust frames, and are possessed of many valuable qualities in a military point of view. From the long predominance of the Mahomedans a considerable proportion of the inhabitants profess that religion, and from both persuasions a great number of the Company’s best sepoys are procured.’

This is also perhaps how the moniker of Awadh being ‘a nursery of sepoys’ came into being. About Ayodhya, the town of Ram, Hamilton writes:

‘This town is esteemed as one of the most sacred places of antiquity.

‘Pilgrims resort to this vicinity, where the remains of the ancient city of Oude, the capital of the great Rama, are still to be seen; but whatever may have been its former magnificence it now exhibits nothing but a shapeless mass of ruins. The modern town extends a considerable way along the banks of the Goggra, adjoining Fyzabad, and is tolerably well peopled; but inland it is a mass of rubbish and jungle, among which are the reputed sites of temples dedicated to Rama, Seeta, his wife, Lakshman, his general, and Hunimaun (a large monkey), his prime minister. The religious mendicants who perform the pilgrimage to Oude are chiefly of the Ramata [Ramawat] sect, who walk round the temples and idols, bathe in the holy pools, and perform the customary ceremonies.’

The Hamilton Gazette

It is noteworthy that Hamilton finds not one temple worthy enough to be described in detail. He merely sums up the religious affiliation—belonging to the Ramanandi Ramawat sect—of the monks, and his account also makes no mention of Ram’s birthplace temple or the Hanumangarhi or even the ancient Nageshwarnath temple. Hamilton recorded what he saw, and perhaps this was all there was to be found: a town in the wilderness, within which lay ruins that had come to be woven with cobwebs and legends of Ram. The majority of Ayodhya’s population stayed close to the river, and some isolated temples had come up across the inland keorah (a tree used for perfumes and spices) forests. In short, it was (unlike it is now) a place shorn of the humdrum of a big pilgrim centre or the buzz of the religious bazaar of other Hindu centres like Haridwar and Banaras.

It is noteworthy that Hamilton finds not one temple worthy enough to be described in detail… Hamilton recorded what he saw, and perhaps this was all there was to be found: a town in the wilderness, within which lay ruins that had come to be woven with cobwebs and legends of Ram… In short, it was (unlike it is now) a place shorn of the humdrum of a big pilgrim centre or the buzz of the religious bazaar of other Hindu centres like Haridwar and Banaras.

The year 1855 was momentous in the history of Ayodhya. It is often cited as the year in which the recorded history of the Ram Janmabhoomi– Babri Masjid dispute commences. It should also be seen as a marker of the half-truths that have come to systematically shroud the vexed issue. This is because in 1855, the bloody conflict that took place was not over the supposed birthplace of Ram. It was over the Hanumangarhi temple and the claims by certain Sunnis that the Bairagis of Hanumangarhi had destroyed a mosque that existed atop it. The Muslims charged on the Hanumangarhi but were repelled and routed. They hid inside the mosque of Babur that lay at a distance of less than a kilometre from Hanumangarhi. In this way, the site of the Babri Masjid became embroiled in the dispute over Hanumangarhi. At the time of the 1855 riot, the Bairagis had not claimed the Babri mosque as the birthplace of Ram. It was only much later that the conflict of 1855 came to be associated primarily with the Babri Masjid instead of the Hanumangarhi temple. Today, it is widely believed that the first recorded Hindu struggle for Ram’s birthplace dates back to the events of 1855.

…in 1855, the bloody conflict that took place was not over the supposed birthplace of Ram. It was over the Hanumangarhi temple and the claims by certain Sunnis that the Bairagis of Hanumangarhi had destroyed a mosque that existed atop it.

It is ironic that despite voluminous British and other contemporary records of the incident, it is this falsified version that is accepted as the ‘truth’. There are however, some incontrovertible facts about it:

Firstly, that the Muslims claimed that there was a mosque on Hanumangarhi and that it was destroyed by the Bairagis.

Secondly, that there took place a bloody battle in which Muslims were routed and that they took shelter in the Babri mosque.

And finally, at least till the 1855 dispute, the Babri Masjid had not been claimed as Ram’s birthplace.

Hanumangarhi, a temple of Hanuman, Ram’s most devout devotee, is built atop a small hillock that also happens to be the highest point in Ayodhya. Today, it is a well-fortified temple, with fourteen cannons adorning its ramparts. At its foot live hundreds of Bairagis, the more important ones live in modern buildings equipped with all conveniences. It is the most favoured temple for the lakhs of devotees who visit Ayodhya every year. For them a trip to Ayodhya has always meant a dip in the Sarayu, followed by a visit to Nageshwarnath and Hanumangarhi. Hanuman is special even to Ram; therefore it is no surprise that for Hindu pilgrims too, he is sometimes revered more than Ram himself.

Even though Hanuman is identified with Ram by most lay devotees, he is claimed by both Vaishnavas and Shaivas (in fact to lay devotees, Ram, Shankar, Vishnu, Hanuman and Ganesh are all forms of the same god).

Devdutt Pattanaik, in some ways a modern version of Valmiki himself, explains Hanuman’s all-round appeal thus:

‘According to Shaivites, Shiva himself descended as Hanuman to destroy Ravana, an errant Shiva-bhakta. They said that Ravana had offered his ten heads to Shiva and obtained boons that made him very powerful. But as Rudra, Shiva has eleven forms. Ravana’s offering of ten heads satisfied ten forms of Rudra. The eleventh unhappy Rudra took birth as Hanuman to kill Ravana. Hence Hanuman is also Raudreya.

‘To establish their superiority, Vishnu-worshippers argued that Hanuman, hence Shiva, obeyed instructions given by Vishnu. To counter this, Shiva-worshippers said that without Hanuman’s help, Ram would never have found Sita. In many stories, it is Hanuman who enables the killing of Ravana. For example, in one Telugu retelling, despite knowing that Ravana’s life resided in his navel, Ram shot only at the head of Ravana as he was too proud a warrior to shoot below the neck. So Hanuman sucked in air into his lungs and caused the wind to shift direction causing Ram’s arrow to turn and strike Ravana’s navel. Association with Shiva, and with celibacy, was reinforced by Hanuman’s association with the various ascetic schools of Hinduism, from the Nath-jogis who followed the path of Matsyendranath from around 1,000 years ago, to the Vedantic mathas who followed Madhva-acharya from around 700 years ago, to Sant Ramdas who inspired many Maratha warriors 400 years ago. The latter sages, especially during the bhakti period, introduced the idea of connecting celibacy with service; you give up your worldly pleasures and work for the worldly aspirations of society. Just as the hermit Shiva becomes the householder Shankara for the benefit of Humanity, they spoke of how the ascetic Hanuman became Ram’s servant for the benefit of society.’

So, irrespective of whether it was the Bairagis or the Shaiva Sanyasis or Nath-Yogis who were the original founders of Hanumangarhi, at the time of the 1855 conflict, Ayodhya and Hanumangarhi both had become centres of the Ramanandis.

Land was first allotted to one Abhayaram Das of Hanumangarhi in the time of Saadat Khan, who, as we have seen earlier, was the first governor of Awadh, between 1722–1739 CE. Subsequently, his successors, Safdarjung as well as Shuja-ud-daulah, supported the temple’s construction with more revenue land grants. Finally, in the time of Asaf-ud-daulah, the Hanumangarhi temple was completed. It is important to note here that according to tradition, the first land grant made to Hanumangarhi was after the Galta conference of 1718 CE, and the completion of Hanumangarhi happened only in 1799 CE under Diwan Tikait Rai during Asaf-ud-daulah’s governorship of Awadh. Asaf-ud-daulah, as we have seen, moved the capital even further away from Ayodhya—from Faizabad to Lucknow. Earlier, Safdarjung had moved the capital from Ayodhya to Faizabad. Some writers find the shifting of the capital as evidence of the Muslim nawabs recognizing the Hindu pre-eminence of Ayodhya. There is no evidence to suggest that this was the reason, but from a strategic point of view, Faizabad would have made more sense as it was more suited for the founding of a capital with its vast plains and the river Sarayu’s wide channel protecting it in the west.

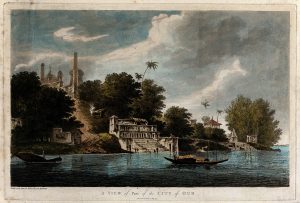

Ayodhya as seen from the river Ghaghara, Uttar Pradesh. Coloured etching by William Hodges.

Land was first allotted to one Abhayaram Das of Hanumangarhi in the time of Saadat Khan, who, as we have seen earlier, was the first governor of Awadh, between 1722–1739 CE. Subsequently, his successors, Safdarjung as well as Shuja-ud-daulah, supported the temple’s construction with more revenue land grants. Finally, in the time of Asaf-ud-daulah, the Hanumangarhi temple was completed… Asaf-ud-daulah, as we have seen, moved the capital even further away from Ayodhya—from Faizabad to Lucknow… Some writers find the shifting of the capital as evidence of the Muslim nawabs recognizing the Hindu pre-eminence of Ayodhya. There is no evidence to suggest that this was the reason, but from a strategic point of view, Faizabad would have made more sense…

By 1855, the British had become the de facto rulers of Awadh. British troops were present in places like Faizabad, Lucknow and Gorakhpur to ensure the stability of areas under their direct control. With the help of a large spy network, the British officers ensured that they were in step with the developments in the province. In February 1855, the Resident of Lucknow, Major General G. B. Outram of the Awadh Frontier Police, had written to Wajid Ali Shah, warning him of a ‘dreadful breach of peace’ by Muslims led by one Shah Ghulam Hussein. Muslim fundamentalists in north India had gained much currency owing to the weakening of the absolute supremacy of rulers. In Awadh, the situation was a little more suitable for people like Hussein, given that the rulers of the province were Shia and a large number of the Muslim population were Sunni. In addition to this, there existed a historical rivalry between the mostly Sunni Afghan-origin Pathans and the more recent arrivals, non-Afghani Shias. But more than anything it was the defiance of rulers by religious leaders that incited the conflict. Muslim religious preachers had started to blame the godlessness of the rulers for the enslavement by the British, and openly preached jihad.

In Awadh, the situation was a little more suitable for people like Hussein, given that the rulers of the province were Shia and a large number of the Muslim population were Sunni. In addition to this, there existed a historical rivalry between the mostly Sunni Afghan-origin Pathans and the more recent arrivals, non-Afghani Shias. But more than anything it was the defiance of rulers by religious leaders that incited the conflict. Muslim religious preachers had started to blame the godlessness of the rulers for the enslavement by the British, and openly preached jihad.

The letter Major General Outram to the King of Awadh, Wajid Ali Shah, dated 8 February 1855, stated with the certitude of foreknowledge and forewarning:

‘ …it appears that Shah Ghulam Hussein has assembled a large force of Musulmans at Kotuaha in the neighbourhood of Fyzabad and is intent upon committing some dreadful breach of the peace and is determined to destroy and ruin the Hunnooman Ghurrie which is inhabited by Hindoos… His Lieutt. [astt.] called the Maulvee Sahib (Three maulvis or Muslim priests feature in reference to Faizabad and the 1857 mutiny. Ghulam Hussein; Ameer Ali of Amethi who was killed by the Awadh forces while on a march to attack Hanumangarhi; Maulvi Ahmadulah Shah who appeared in Faizabad in 1856 and was imprisoned by the British for his anti-British speeches.) is even more diabolically inclined and ready for strife—hence the mendicants and devotees, who are there at Hunnooman Ghuree in defence of their lives have been obliged to arm themselves… therefore the Resident feeling exceedingly anxious on this subject entreats His Majesty to despatch a very swift camel messenger with all possible speed, to convey to the King’s servants, most peremptory orders to cause the immediate apprehension of Ghulam Hussein and his coadjutors.’

Maulvi Ghulam Hussein claimed to his followers that the Bairagis of Hanumangarhi had destroyed a mosque atop that hillock which needed to be redressed by rebuilding it. A large number of Muslims gathered on his side in support of this cause, and having the confidence of belonging to the religion of the ruler, charged at the 70-feet-high Hanumangarhi on 28 July 1855. With help from Hindus from surrounding areas, the Bairagis and the more militant Naga sadhus (Vaishnavas), repulsed this attack and routed the maulvi and his followers. The Muslims retreated to the Babri Masjid, which was then attacked by the Bairagis. More than sixty-five Muslims were killed and the Bairagis allegedly held possession of the mosque for three days. The bodies of Ghulam Hussein’s men (he managed to escape) were buried around the mosque and the area later came to be known as Ganj Shaheeda, or Martyr’s Place or Quarters.

Captain A. P. Orr, as the British officer in charge of the troops stationed in Faizabad, acting on intelligence about the impending attack, had secured a temporary peace between the Bairagis and Shah’s followers a day earlier. The peace he had secured was by dint of placing his troops between the Hanumangarhi and the Babri Masjid. Orr expected reinforcements the following day; however, as he realized later, the few buildings that existed then were all filled with the supporters of the Bairagis. Having prevented violence for a day by invoking the power of the king and the British Resident, Orr returned to his house at night.

Maulvi Ghulam Hussein claimed to his followers that the Bairagis of Hanumangarhi had destroyed a mosque atop that hillock which needed to be redressed by rebuilding it. A large number of Muslims gathered on his side in support of this cause, and having the confidence of belonging to the religion of the ruler, charged at the 70-feet-high Hanumangarhi on 28 July 1855.

Ghulam Hussein and his band of ‘fanatic’ followers used the Babri Masjid as the launching place for the attack that finally took place on 28 July 1855 at around 1 p.m. A. P. Orr’s first-person account gives us an insight into how the British viewed the entire episode. After the battle, Orr in a letter to his superior, G. K. Weston, superintendent of the Awadh Frontier Police, wrote:

‘ …with regard to Shah’s people all our remonstrances were of no avail; persuasion, entreaty, threats, all were lost on these fanatics. On the other hand the Byragees were perfectly willing to listen to us and to obey the government orders… the answer that we last obtained from the Shah’s people was that at the time of Johur Nemaz [Muslim prayer after mid-day] they would attack the Byragees and not listen to further proposals as they could no longer restrain the Ghazees [volunteers ready to die in a religious cause].’

By the morning of 28 July 1855, Orr’s small force had been augmented by more troops led by Captain Hearsey, another officer, and in all they had 150 men and a few guns. Deciding not to intervene, they moved to a better vantage point from where the imminent battle between the two parties could be observed. Orr continues:

‘ …the Mahomedans may at the outset have numbered 4 or 500 men, the Byragees with their allies more than 8000. The leaders of the Shah’s party were soon laid prostrate while endeavouring to cheer on their men towards the Hunooman Gurrie, the greater portion of the Shah’s allies i.e Mahomedan inhabitants of Oude and of Fyzabad fled on every side and his own immediate followers together with few friends who still remained staunch to him, retreated.’

The maulvi and his Ghazees were badly routed and they ran back to the masjid ‘pursued by the Hindoos’.

In the letter, Orr records for the first time the use of the Babri Masjid as a hiding place by the retreating followers of Ghulam Hussein.

That day a general massacre of those hiding in the masjid took place. Orr described it as a ‘deadly contest’, in which ‘the Byragees yelling and furious though obstinately resisted closing on the Musjid hemmed it in on every side and after a few desperate efforts stormed it and gave no quarter’. Orr records that seventy of the Shah’s people were killed, ‘and as many perhaps or more of the Byragees and their allies’.

In the letter, Orr records for the first time the use of the Babri Masjid as a hiding place by the retreating followers of Ghulam Hussein.

That day a general massacre of those hiding in the masjid took place. Orr described it as a ‘deadly contest’, in which ‘the Byragees yelling and furious though obstinately resisted closing on the Musjid hemmed it in on every side and after a few desperate efforts stormed it and gave no quarter’.

Watching the massacre from a distance as a passive observer needed to be explained to his superiors, and Orr did so by suggesting that their numbers were too few and thus if they had intervened, and failed, a general insurrection would have been likely. ‘Thus we remained passive though during the whole of this fray we endeavoured by every means in our power to restore peace,’ Orr wrote. Hostilities were briefly interrupted because of a monsoon storm and during this short break, Orr tried to get the Muslims in the masjid to take shelter in his position which was defended by small cannons and guns, but they refused to do so. Soon enough the rain stopped and fighting resumed, which ended only when all the Muslims were either dead or had escaped.

The concluding part of Orr’s letter—in which he demarcates the different equations at play in this affair—is more important. He writes that the nawab’s local nazim or agent of the district, Aghai Ally Khan, was a Shia and Ghulam Hussein and his followers Sunni; therefore a compromise would not have been reached. About the Hindu leadership, Orr wrote, ‘as to Raja Maun Singh, his followers openly espoused the cause of the Byragees, his claims to impartiality must therefore be much questioned’. Raja Man Singh was in charge of Sultanpore under which Oude (or Ayodhya) also fell.

He (Orr) writes that the nawab’s local nazim or agent of the district, Aghai Ally Khan, was a Shia and Ghulam Hussein and his followers Sunni; therefore a compromise would not have been reached. About the Hindu leadership, Orr wrote, ‘as to Raja Maun Singh, his followers openly espoused the cause of the Byragees, his claims to impartiality must therefore be much questioned’. Raja Man Singh was in charge of Sultanpore under which Oude (or Ayodhya) also fell.

Another reason for Orr to not intervene in the battle was that he doubted the loyalties of his Hindu and Muslim soldiers if he ordered them into a three-way fight. Thus, the first bloody battle in Ayodhya came to an end, with a cynical British force overseeing it from a vantage point. And once all seventy odd Muslims and many more Hindus were killed, Orr seemed to justify his inaction; in characteristically colonial style, he blamed the Hindus and Muslims for their own deaths. Orr reasoned, ‘in conclusion though none can more than ourselves regret that so many blind misguided creatures have been so summarily disposed of, yet, it may truly be said that their blood is on their own head’. This—as British history in India vindicates—was a pattern: the British were somehow always ‘too few in number’ to prevent a massacre of Indians by Indians.

Outram, Resident at Lucknow.

A series of letters, secret communiqués and meetings followed the massacre at Faizabad. In August 1855, the British and the nawab were so completely occupied with this matter that not a day passed without the Resident, G. B. Outram, weighing in on this issue, either in letters to Governor General Lord Dalhousie in Calcutta, or in meetings with Wajid Ali Shah, even as he continued to exchange reports and instructions with his subordinates like Orr.

It seems the nawab had been warned about the possibility of such violence before it occurred and it was brought up by Resident Outram when he met Wajid Ali Shah on 1 August 1855 at a conference held at a palace called Zard Kothi. The nawab was surprised to learn this and denied any prior knowledge at which point Outram produced a copy of an earlier letter of warning.

The nawab, cautious not to appear to be siding with the Hindus, did not, at first, agree with the Resident’s suggestion of setting up a tripartite commission of enquiry made up of ‘Hindus, Muslims and a Christian judge’. The nawab’s own view was to first allow for a cooling of tempers on both sides before such a step was taken. Given the rising anger in his Muslim subjects against the massacre of Muslims in Ayodhya, the nawab was worried about a backlash.

Outram, taking up the cudgels on behalf of Hindus, reminded the nawab that over two-thirds of Awadh’s population was Hindu and that it wouldn’t be wise to give them any cause for enmity. The Hindu chiefs were powerful and would not remain quiet and unmoved if ‘the contest were renewed and any further outrages were committed on shrines which from time immemorial had been held by them as peculiarly sacred’.

The nawab having been persuaded by Outram, issued instructions for the constitution of a commission comprising Captain Alexander Orr (who had watched the bloody battle), Raja Man Singh and Chukledar Aghai Ally Khan to ‘commence an immediate investigation into all the particulars connected with the melancholy loss of life—assuring all parties that they should have a patient hearing and most complete redress’. This tripartite commission of enquiry became the first such body to be appointed in the case of Ayodhya.

Almost 150 years later, another commission of enquiry would be set up by the Government of India, under its archaeology wing, but as we shall see, it would have nothing to do with Hanumangarhi or the alleged destruction of a mosque on it. In a remarkable diversion from the original, primeval source of dispute the masjid from which Captain Orr said the Muslims launched their attack on Hanumangarhi would become the site of the same claims and counterclaims. After the 1857 rebellion and the victory of the British to 1980s–1990s India, Hindus would go on to expand their claims to argue that the mosque referred to by Orr was built exactly atop Ram’s birthplace, while Muslims would deny this by saying it was a concocted story.

The nawab having been persuaded by Outram, issued instructions for the constitution of a commission comprising Captain Alexander Orr (who had watched the bloody battle), Raja Man Singh and Chukledar Aghai Ally Khan to ‘commence an immediate investigation… ’… Almost 150 years later, another commission of enquiry would be set up by the Government of India, under its archaeology wing, but as we shall see, it would have nothing to do with Hanumangarhi or the alleged destruction of a mosque on it. In a remarkable diversion from the original, primeval source of dispute the masjid from which Captain Orr said the Muslims launched their attack on Hanumangarhi would become the site of the same claims and counterclaims.

Back in 1855, Outram, the cautious Resident, after getting the commission of enquiry constituted, set about ensuring that the military presence of the British remained strong in Lucknow. He also detailed the entire sequence of events in a letter to Governor General Dalhousie and brought him abreast of the happenings. On 4 August, three days after his meeting with Wajid Ali Shah, Outram stated that the removal of any troops from Lucknow would be hazardous to peace and stability given the high state of vengeful excitement that he claimed the Muslims were in. He also seems to have acted against the advice of his officer, Captain A. P. Orr, by getting the king to set up the commission under Man Singh and Aghai Ally Khan. Orr believed that the two neither got along nor could they be trusted to act above their religious affiliations. Patting both himself and the Hindus on the back, Outram omitted this fact from his letter to Dalhousie. He wrote:

‘I hope the mixed commission consisting of Captain Orr, Aghai Ally Khan and Rajah Maun Singh possessing as it does an equal Mahomeddan and Hindoo element with a Christian Umpire may inspire confidence so as to induce the belligerents to submit to their mediation; for the victorious Hindoos have heretofore displayed the most praiseworthy forbearance and the humbled Mahomedan factions are more likely now to listen to reason.’

Reverting to his fears about the possible fallout of the withdrawal of troops, he concluded his letter by saying:

‘ …but certainly any weakening of the British troops at Lucknow at this juncture when such exaggerated reports of the success of the Sunthal rebels prevail and the already reduced strength of the Cawnporre Brigade is known would be highly dangerous as calculated to encourage the excited Hindoos who form 4/5th of the Oude population to aim at higher objects.’

It appears that Outram knew quite well that he was playing with fire. While he was endeavouring to implement a British plan to annex Awadh, he wanted to be careful not to allow the situation to go out of control. The violence over Hanumangarhi had given the British another pretext to decry the Awadh king, but if not handled with care, Hindu fury and Muslim anger could turn into a general insurrection against the British as well.

It appears that Outram knew quite well that he was playing with fire. While he was endeavouring to implement a British plan to annex Awadh, he wanted to be careful not to allow the situation to go out of control.

Wajid Ali Shah

In Ayodhya, things were moving at a fast pace in the usually quiet temple town. Since the massacre by the Bairagis and their supporters—mostly men from neighbouring villages, the Muslims of Ayodhya had moved out to other safer places. At the same time, the news of this defeat was bringing in Muslims from neighbouring districts to Faizabad every day. The usually more hardline Pathans among them had united under the banner of two maulvis, Ameer Ali and Ramzan Ali of Amethi, who were now said to be marching towards Ayodhya. Through hurriedly written letters, Outram and Wajid Ali Shah had informed each other of the developments at almost the same time. Outram pleaded with the king to direct his servants to ensure that the events of July were not repeated, he implored the king to order the stopping of ‘Pathans and others who are bent in proceeding to Fyzabad and especially to cause the arrest of the two Maulavees’. Wajid Ali Shah, the nawab-king of Awadh, equally concerned by the threat of more violence along religious lines, wrote to Resident Outram:

‘ …it appears from newswriters’ reports that numerous Hindoos and Musulmans are flocking into that place from all sides and that many more are determined to join them. The King is most anxious to put an end to this rupture and therefore entreats the Resident to be good enough to address the various Magistrates of adjacent districts to prevent bodies of armed devotees whether Hindoo or Mahomedan from entering Oude and to take steps to forbid their coming.’

Wajid Ali Shah’s tone makes it clear who the real ruler of Awadh was. The districts from which the mobs were flocking were all in the traditional zone of Ayodhya’s religious influence. There were also Muslim strongholds in the list sent by Wajid Ali Shah. Gorakhpur, Jaunpur, Allahabad, Fatehpur, Kanpur, Farrukhabad, Shahjahanpur and Azamgarh were the chief regions of Sunni populations and these were governed by British magistrates; thus the nawab hoped that his request to Outram, if fulfilled, would deprive the maulvis of Amethi from gaining more followers.

‘The King is most anxious to put an end to this rupture and therefore entreats the Resident to be good enough to address the various Magistrates of adjacent districts to prevent bodies of armed devotees whether Hindoo or Mahomedan from entering Oude and to take steps to forbid their coming.’ … Wajid Ali Shah’s tone makes it clear who the real ruler of Awadh was.

Meanwhile, the Bairagis of Hanumangarhi had signed a bond alluding to their complete willingness to abide by the findings of the tripartite commission of enquiry, whatever they may be. Under Mahant Bilramdass, three other priests put their signature to this bond in which they also spoke of past friendships and a willingness to compromise. Interestingly, the Hanumangarhi priests who were Ramanandis belonging to the Nirvani Akhada did not object to the presence of Aghai Ally Khan. They perhaps knew that as a Shia Muslim, he was not going to be overtly excited by the prospect of Sunni claims. Hindus favoured a Shia over a Sunni member in the enquiry commission and, as Captain Orr had believed, Muslims themselves being largely Sunni, did not trust Aghai Ally Khan because of his Shia persuasion.

Irrespective of all this, the bond signed by Hanumangarhi priests on 10 August 1855 must have brought peace to the mind of the avowedly irreligious and secular Wajid Ali Shah.

The bond promised that:

‘ …having in view our former friendship and acquaintance we declare we have no enmity towards them [Gholam Hussein and others], and agreeing to Aghai Alee Khan, Rajah Maun Singh, Captain Orr as our arbitrators we solemnly swear by Mahabir [another name for Hanuman] and hereby write that we will not on any account create any disturbance or tumult on condition that no one molests us or abuses us. All the Byragees who are of our tribe will not do anything contrary to what we have written… if we act contrary to what we have written we confess that we are deserving of whatever punishment may decree.’

…the bond signed by Hanumangarhi priests on 10 August 1855 must have brought peace to the mind of the avowedly irreligious and secular Wajid Ali Shah. ‘ …having in view our former friendship and acquaintance we declare we have no enmity towards them [Gholam Hussein and others], and agreeing to Aghai Alee Khan, Rajah Maun Singh, Captain Orr as our arbitrators we solemnly swear by Mahabir [another name for Hanuman] and hereby write that we will not on any account create any disturbance or tumult on condition that no one molests us or abuses us.’

In Lucknow, the nawab, anxious to avoid a confrontation with the maulvis, sought the help of the influential chiefs of neighbouring Hadergarh and Gosainganj. The nawab wanted them to persuade the Muslims at Amethi to desist from marching to Ayodhya. In his communiqué to Outram on 11 August 1855, Wajid Ali Shah also apprised him of his plan of seeking religious opinion on how to tackle the belligerent maulvis. On the whole, the nawab appeared to be confident that his plan of peaceful resolution would work, obviating the need for arrests and violence. The king’s seeking of religious sanction was made necessary because of the nature of the maulvis’ campaign. In order to enlist more followers they had declared a planned revenge-attack on Hanumangarhi, a jihad, or religious crusade, against infidels. The king was aware that a jihad could be declared only by the king in a Muslim-ruled country; his plan was to counter the maulvis theologically and take the wind out of their proposed jihad. Ever careful, Wajid Ali Shah concluded his note to Outram with the words ‘but the future is in the disposal of God’.

This, however, was not enough for Outram to repose faith in Wajid Ali Shah’s abilities. Outram was also acting on his own secret intelligence which said that the nawab was only buying time and that once the Sawan mela (the sawan mela is one of the three melas held in Ayodhya every year, it is held in the month of July and marks the start of the rains) in Ayodhya was over, he had promised the maulvis that the mosque would be rebuilt in Hanumangarhi.

In Lucknow, the nawab, anxious to avoid a confrontation with the maulvis, sought the help of the influential chiefs of neighbouring Hadergarh and Gosainganj. The nawab wanted them to persuade the Muslims at Amethi to desist from marching to Ayodhya.

In Faizabad, Captain Orr had his ear to the ground. Consistent with the first report he sent to his superior police officer, G. K. Weston, the superintendent of the Awadh Frontier Force, Orr again advised against any immediate enquiries by the tripartite commission. In this he was echoing Nawab Wajid Ali Shah’s own instinct. However, Orr also warned about the effect of the presence of certain Muslims in Faizabad.

On 11 August 1855, the same day that the king informed the Resident of his aversion to arresting the maulvis, Orr wrote to G. K. Weston again regarding certain decisions taken by the committee comprising Aghai Ally Khan, Raja Maun Singh, Captain A. P. Orr and Captain J. Hearsey. He opened his letter by stating forthrightly that ‘it would not be safe in the present state of affairs to institute enquiries regarding the existence in the midst of Hanooman Gurrie of a Musjid’.

Ameer Ali, the radical preacher who had vowed to avenge the deaths of Muslims in Ayodhya, was gathering numbers for his jihad near Amethi. Meanwhile, certain Muslim notables said to be deputed by the court in Lucknow, were in Faizabad and Ayodhya. They were conducting their own enquiry and were collecting signatures and testimonies vouching for the existence of the mosque in Hanumangarhi. As we will see later in the book, such campaigns continue to take place in contemporary Ayodhya.

Captain Orr also worried about the adverse effect these persons were having in an already tense atmosphere. In the same letter Orr categorically mentions the danger posed by the presence of these ‘notables’ and requests his superior to ensure that they are removed from there.

Captain Orr’s fears about the independent enquiries by the notables from the Lucknow court proved to be justified as the next day, on 12 August 1855, Outram, the Resident, received another communiqué from the king of Oude. Along with the dispatch, the king had also sent for his perusal the documents collected through the above-mentioned notables’ efforts.

The king’s letter summed up the findings thus:

‘The purports of these papers is that A MOSQUE WAS BUILT BY ONE OF THE FORMER SOVEREIGNS OF DELHIE, that this fact is notorious, that in the days of Borhanool Muk [Saadat Ali Khan I] Sobahdar of Oude, there was a quarrel of the same kind but the Hindoos subsequently declared that they had no intention of meddling with the mosque. One witness who declares he is 104 years old asserts that he has repeatedly seen the mosque. One Chuprasee Dhunnee Singh, a Hindoo, declares that he saw the mosque in the time of Hakeem Mehudee who was a minister in the days of Nusseeruddeen Hyder (1827–1837), one Chedee, a Hindoo, declares he has often seen the Musjid. The tenor of all these papers casts all the blame on the Hindoos and details their atrocities—two leaves of the Koran which were found on one of the slain is sent for His Majesty’s inspection; they have been trampled upon, burnt and torn.’

The note then proceeds to record the various crimes committed by Hindus, including destroying the tomb of Khwaja Huttee Shah and slaying a pig in the mosque while it was in their possession. It ends by describing the genesis of the Hindus’ aggression and says that, ‘the Hindoos first began to interfere and became powerful when the district of Sultanpore fell into the hands of Durshan Singh Chukledar and their encroachments commenced and have progressed’.

The next day, Resident Outram responded with disdain to these documents and summarily declared them to be ‘untrue’ in a letter to the king. While doing so he employed the age-old argument of ‘obtained under duress and coercion’ that is used against suspicious affidavits and testimonies.

The Resident wrote, ‘His Majesty must be well aware that it is very easy for interested parties to obtain seals and signatures to any representations they may choose to make in the heat of religious excitement and doubtless the opposite party would easily obtain similar testimony in support of their assertions.’ The Resident then declared the documents and the claims made by the nawab-king to be baseless. He also goes on to dismiss the claims about the slaying of a pig, desecration of the Quran, and destruction of Khwaja Huttee’s tomb in Hanumangarhi. He explained his dismissal saying:

‘The enclosed representations are obviously untrue in one particular in as much as they attribute the whole of the blame to Hindoos, whereas it is notorious and moreover officially reported by Capt Orr that they were ready to submit their grievances to the King’s decision, even when victorious they abstained from all violence and from the commission of any excesses and enormities. His Majesty can not fail to be convinced of the truth of this when His Majesty peruses the bond signed by the leaders of the Byragees in which they profess their readiness to submit to terms and which reached the King yesterday. It is well known that the Mahomedans would not listen to reason and that they began the conflict.’

The Resident then concludes that ‘the alleged atrocities of the Byragees such as trampling on the Kuran and the sacrifice of swine (in the musjid) may prove equally unfounded and baseless’.

The Hanumangarhi temple

Though Outram doesn’t specify the mosque he is referring to, it could only either be the one atop Hanumangarhi, which was destroyed by the Bairagis, or the Babri Masjid from where the Muslims had launched the attack. In 1855, curiously enough, no extant British record of the Hanumangarhi conflict identifies the said mosque as Ram Janmabhoomi. The next day, on 15 August 1855, Captain Orr reported to Superintendent Weston a series of steps he had taken for the officially appointed tripartite commission to carry on its work. Owing to the sawan mela a large number of Hindus had gathered in Ayodhya. As the presence of thousands of Hindus had increased the risk of violence erupting again, the commission had been unable to make probes regarding the existence of a masjid on Hanumangarhi. Therefore, Orr finally decided that Raja Man Singh should conduct ‘private and strict enquiries as to the existence of the supposed Musjid and to report the result of his personal researches, which would eventually be verified’ by other members of the committee. The reason Orr gave for reposing such faith in Man Singh was curious and contradictory to his own earlier view regarding Man Singh’s impartiality. Orr said, ‘the Rajah being of the Hindoo persuasion could more easily effect the object the Committee had in view than any other of its members’. In July, Orr had cited the same ‘Hindu persuasion’ to report to Weston the untrustworthiness of Man Singh. But now, Man Singh had become fit to be trusted again and he lived up to the expectations of the British by quickly completing his ‘private and strict’ probe. As Orr put it in his letter:

‘Raja Maun Singh had succeeded, not only in obtaining the desired information stating that to the best of his belief no Musjid existed in the Gurrie, but also obtained from the Mahunt Byragees of Hannooman Gurrie two papers signed and sealed by them, by which they bind themselves to allow the Committee to make any investigations necessary to satisfy the demands of the government.’

Though Outram doesn’t specify the mosque he is referring to, it could only either be the one atop Hanumangarhi, which was destroyed by the Bairagis, or the Babri Masjid from where the Muslims had launched the attack. In 1855, curiously enough, no extant British record of the Hanumangarhi conflict identifies the said mosque as Ram Janmabhoomi.

Having obtained this bond, and armed with Man Singh’s findings, the committee called a public meeting of prominent Muslims of Faizabad–Ayodhya and surrounding areas in Gulab Bari, the magnificently built tomb of Shuja-ud-daulah. The purpose of this meeting was to give Muslims an opportunity to put forward their claims, grievances and evidence regarding the mosque in contention. A large number of Muslims had fled Ayodhya after the massacre in July, and now a number of them spoke up to say that even if such a masjid existed, it was in the domain of the king of Oude to recover it. All that these Muslims ‘now wished was to obtain some security of life and property in order to return to their homes at Awudh, which they have abandoned since the late disturbance’, wrote Orr.

Interestingly, it was also decided that the individuals who had claimed to have seen the masjid, including the Hindus Chedee Singh and Dhunee Singh, should be taken to Hanumangarhi, asked to show the spot where the masjid stood, and prove the veracity of their assertions. Orr reported to his superior Weston that this was now possible as the Hanumangarhi priests had agreed to ‘allow us to dig open any one spot pointed out by the Mahomedans as containing their Musjid’. If there was a quid pro quo deal affected by Raja Man Singh with the priests, Orr’s letter doesn’t reveal it. Seemingly satisfied with the committee’s work so far, Orr concluded that ‘surely such an investigation will satisfy the most bigoted’.

Outram was pleased to hear that Orr had been successful in defusing the situation with the help of Man Singh and Aghai Ally Khan. Outram transmitted the contents of Orr’s letter to Governor General Dalhousie in Calcutta. As Lucknow was under his direct supervision, he also added the latest update on the situation there:

‘In this city especially the excitement was very great. War with the Hindoos was openly preached in the mosques in spite of the exertions of the authority to prevent it and fanatic moolahs erected the standard of Islam at Qurcita 7 miles distant where all true Moslams were urged to assemble. Some hundreds did so and thousands in this city who were prepared to join, were with difficulty deterred by the most stringent measures of the Government.’

Outram’s self-serving portrayal of the situation at Lucknow and Ayodhya was only partially true. Indeed, the Muslim clergy, including some Shia priests, were by now roused by the British-backed handling of the Hanumangarhi situation. Just a week after Outram had shared his satisfaction at the abatement of the conflict, a mujtahid, a high priest or Shia imam, raised the hackles of the British once again.

Spies brought news that after the Eid celebrations at Asaf-ud-daulah’s Imambara, the high priest had openly showered curses on Aghai Ally Khan, a member of the Hanumangarhi committee, and alleged that he, a Shia, had accepted bribes to favour the Hindus. Many notables from Wajid Ali Shah’s court were present on this occasion but remained silent.

Four days later, on 28 August, the Hanooman Ghuree Commission’s petition was received by Wajid Ali Shah. The commission had concluded its work and was ready to present itself and the various witnesses and deponents it had examined to the king in Lucknow. Orr, the unofficial head of the commission, also wrote to Weston, forwarding with the letter the various depositions collected by the king’s committee under Maulvi Hafizullah, the eleven depositions given to the tripartite committee (including Orr, Man Singh and others), the statement of a Muslim bricklayer, Joomun Khan, bonds furnished by the priests of Hanumangarhi, sunuds (royal grants) furnished by the priests of Hanumangarhi, and the committee’s urz-dasht (written petition).

Spies brought news that after the Eid celebrations at Asaf-ud-daulah’s Imambara, the high priest had openly showered curses on Aghai Ally Khan, a member of the Hanumangarhi committee, and alleged that he, a Shia, had accepted bribes to favour the Hindus.

The findings of the other so-called independent committee led by maulvis Hafizullah and Nihaluddeen were rejected as false and fake by Orr. He considered them as having been ‘preconsented’ and full of discrepancies.The sunuds shown by the Hanumangarhi priests on the other hand were taken to be legitimate and because ‘no reference whatsoever is made to the existence of a Musjid, neither within nor near the precincts of the Gurhee’. Orr thought it was proof that no masjid could have existed there. Orr further stated that the deposition of Joomun Khan corroborated his conclusions. Moreover, according to Orr, more proof lay in the

‘ …depositions furnished by two of the Mahunts of the Guree, they contain total denial of the Musjid having ever existed, with a shrewd and in my opinion just remark, that had a Musjid stood in their Gurree at all events within the last 25 or 30 years would it not have been remarked by the Kotwal of the City Mirza Mooneem Beg, whom they cite, as having on more than one occasion visited their building.’

Finally, Orr clinches the anti-mosque argument by stating that even those Muslims who had claimed to have seen and even prayed in the mosque at Hanumangarhi were unable to point to the spot where it could have existed. Some even blundered by pointing out a directionally implausible spot as Muslims offer prayer while facing the west. Thus Orr concluded with certitude:

‘no traces however slight of such a building now exist… In fact it seems of itself improbable that two buildings consecrated to such opposite creeds, could ever have stood in so close proximity—and is it not moreover extraordinary that during so many years, that is at the very lowest calculation from the time of Munsoor Ali Khan Soobadar of Oudh, to the present period, no one, either ruler or subject should with the exception of Shah Ghulam Hussein and his followers, have taken cognizance of such matter had they been worthy of consideration.’

Thus, the claims of Muslims being deemed bogus, fake and time-barred, were rejected and the commission sought to close the matter.

Upon learning the outcome of the commission’s enquiry, Maulvi Ameer Ali, who had reached Lucknow and was under house arrest, set out on his jihad once again. With more than 200 devoted followers the maulvi seemed to have been discreetly supported by the Shia clergy in addition to the Sunni clergy. In order to halt his march, Wajid Ali Shah dispatched some envoys who were able to convince the maulvi to postpone it for the time being and allow the peaceful resolution of the dispute. Ameer Ali was also warned that if he disobeyed the nawab’s order, he would be forcibly restrained. What Wajid Ali Shah had in mind was a plan that would ‘satisfy all parties’. The proposal was radical; it suggested ‘that the King should build a mosque resting on one wall, but outside of the ghuree… and the dividing wall be so raised as to prevent either Moslem or Hindoos interfering with each other, or either party even seeing into the others’ place of worship’. Wajid Ali Shah also stated that Hanumangarhi priests would be suitably awarded any reasonable demands of land if they agreed to this proposal. Resident Outram reported these details to Dalhousie with scepticism about the success of the proposal.

What Wajid Ali Shah had in mind was a plan that would ‘satisfy all parties’. The proposal was radical; it suggested ‘that the King should build a mosque resting on one wall, but outside of the ghuree… and the dividing wall be so raised as to prevent either Moslem or Hindoos interfering with each other, or either party even seeing into the others’ place of worship’.

In Calcutta, upon learning of the developments in Awadh, Governor General Dalhousie stressed that this was ‘further proof, if further proof were necessary, of the unfitness of the King of Oude and of his Durbar to hold the powers of Government in that country and fortify the opinion which I lately submitted to the Hon’ble Court that the administration should be entirely taken out of their hands’. The British were preparing the ground to annex Awadh and the Hanumangarhi incident was being woven into that plan.

Back in Ayodhya, Orr, who was tasked with getting the Hanumangarhi priests to agree to the king’s compromise formula, failed to convince them. Orr conveyed his failure to Outram, who transmitted it to Dalhousie on 16 September. The Bairagis, reported Outram, declared ‘that if it is attempted to build a Mosque adjoining the Hunooman Ghuree, they will vacate the place and at the same time desert every one of the temples of Awudh, which in other words really means that they are prepared to resist any such attempt to the death, for never in life would they abandon these holy shrines’. Rhetoric was building up again on both sides—on three sides if one includes the British, who were desperately hoping to convert this conflict into a dramatic cause so that they could annex Awadh.

When Outram met with Wajid Ali Shah a few days later on 29 September, he tried his utmost to impress upon him the need to take immediate action to restrain Maulvi Ameer Ali. No doubt this would have made Wajid Ali Shah extremely unpopular among his co-religionists in the court and outside. He was aware that any action by him that was perceived to be anti-Islam would make his position even more untenable. Unsympathetic to Wajid Ali Shah’s predicament, Outram also alleged that the nawab-king had made a secret pledge to Ameer Ali about the construction of the mosque at an appropriate time even though Wajid Ali Shah had dismissed such allegations as ‘preposterous’. The nawab-king was convinced that the matter could be resolved to the satisfaction of all. In order to buy more time, he now proposed the formation of a second commission comprising an equal number of Hindus and Muslims. It seems from Outram’s account that Wajid Ali Shah was not convinced of the Bairagis’ version of the dispute. According to the minutes of a meeting between Outram and him, the king believed, ‘much misconception prevailed… as to the sanctity of the ground generally known as Hanooman Guree—in fact—but a very small portion of it was sacred, the rest having been quietly added by the Hindoos to the ground granted by His Majesty’s ancestors more than a century ago’.

And therefore, Wajid Ali Shah expected the Hindus to agree to the proposal of sharing the space atop Hanumangarhi with a mosque. Outram agreed but added a caveat. The minutes of that meeting record him issuing a warning to the king of Oude.

‘The Resident declared that he would be delighted to learn that the Hindoos could be persuaded to yield compliance but he did not hesitate to warn His Majesty against any such attempt to take even one yard of ground without the fullest and most unqualified consent of the Hindoos—on no other ground could His Majesty attempt to build the Musjid without lighting up the flames of civil discord in his territories.’

What Wajid Ali Shah really thought of the British Resident’s very sensible but obvious word of caution is not known but he assured him that nothing would be done by force.

Meanwhile, Ameer Ali who was still camped on the road to Ayodhya, thought of keeping his ghazis (crusaders) motivated by letting them loose on Hindus and Shias. While stationed near Saheliya, a village that now falls in Barabanki district, his followers, ‘annoyed at the blowing of Sunks [conch shells] in the temples belonging to Roopnarain and Salikram Brahmins of Saheli’, attacked the place and destroyed all the idols and threw them into the adjacent pond. The Brahmins, together with their families, fled to Calcutta, according to a dispatch dated 4 October from the Resident’s office. Besides mentioning the attack on Hindus the same set of dispatches also informed the Governor General in Calcutta that ‘the report is confirmed that a fight had taken place between the Syeeds of Zaidpore (20 kilometres from Saheli) and Ameer Ali’s followers, in consequence of the Maulavi having endeavoured to prevent the Syeeds carrying their Tazeahs in procession until the Musjid should be built in the Hanooman Ghuree, 8 men were killed and 6 wounded on both sides’.

The dispatch by Outram on 4 October was significant as it not only reported the maulvi’s communal excesses but also because it reported that Wajid Ali Shah, responding to the spate of conflicts involving the maulvi’s militia and Hindus—and in one case Shias—had deputed mainly Hindu troops to march to Hanumangarhi and protect it. It also conveyed a rising degree of alarm among the general population which was evidenced by the fact that the richer families of Faizabad and Ayodhya were relocating their women and children in anticipation of violence.

Between 5 October and 8 November a number of events took place that brought an end to Maulvi Ameer Ali’s campaign. His patience exhausted, Ameer Ali gave up on Wajid Ali Shah keeping his reported promise to build the mosque atop Hanumangarhi. The king too had all but abandoned hopes of a peaceful resolution, and now he gave clear orders to intercept the maulvi en route to Ayodhya. On 5 October, Outram reported to Lucknow that it was generally believed ‘that the assault on the Hanooman Ghuree will take place on the 40th day of Mohurram (23 October)’.

In Hanumangarhi, the Bairagis were fortifying their defences and making small holes in the walls of the temple-fortress through which arms could be fired. The word on the street in Ayodhya, Faizabad and Lucknow was that Hanumagarhi was also receiving aid from the kingdoms of Gwalior, Jodhpur and the local talukdars or chiefs of Awadh. Amidst this buildup, Raja Man Singh brought a delegation of Hanumangarhi priests to Lucknow.

The maulvi, still camped on the road to Ayodhya, was also being joined by hordes of Muslim men. In a last-ditch effort to strike a compromise, the king’s deputies met him and once again beseeched him to defer his march. Writing disapprovingly about it, Outram informed Calcutta on 7 October that after much persuasion and ‘begging’, Ameer Ali was ‘induced to grant a further respite of 5 days—if, however, on the Friday next, some steps shall not have been taken by the Durbar, he intends then to proceed to Bansa… eastward of Saheli, and there raise the standard of Islam’.

The maulvi had relented, but only a little. Unbeknownst to him at the time, his predicament was to worsen soon. Outram was totally against the constitution of another commission of enquiry and had rejected the nawab’s request to join such a commission if it were formed. His reason being: ‘he [Wajid Ali Shah] supposed the British Government would be bound to support the subsequent measures of the Durbar for enforcing the decree of the Committee whatever that might be. As I had reason [not specified] to believe that bribery would be employed to induce the Hindoo members to betray their trust, it behoved me I conceived for that reason particularly but also under any circumstances, to reject the overture in explicit terms.’

The British had practically come to rule Awadh in the eighty years since the Battle of Buxar in 1775. Gradually, they had also come to acquire a network of spies that was spread deep and wide across the province as well as in other parts of India. A letter dated 15 October reflects the astuteness with which the East India Company ran its intelligence network. On the basis of information provided by a clerk in a government office in Faizabad, Outram listed the number of local Hindu chiefs who were ready to support the Bairagis of Hanumangarhi; some of them had also offered money. Outram wrote, ‘among others from whom letters and pecuniary contributions have been received, he [the clerk-spy] enumerates the Rajahs of Bansee, Pyrespore, Ramnuggur, Dumeree, Souhan—Ranee of Dairwa— and Maharajahs of Gwalior and Joudhpore’.

Governor General Lord Dalhousie

On the same day, Governor General Dalhousie in Fort William, Calcutta, drew up a note that both summarized the developments in Awadh and laid down British policy for future events. He authorized Outram to use ‘decided language’ to convey the displeasure of the British government should Wajid Ali Shah ‘either direct or not prevent an attack on the Hindoos’. He declared that such a neglect of duty would make the king regret his inaction. Dalhousie approved the actions of the Resident at Lucknow along with his own and patted himself on the back for his commitment to always acting in the interests of the British government. Wajid Ali Shah’s decision to dispatch Hindu troops for the protection of Hanumangarhi was lauded by Dalhousie. That rare praise was overshadowed by his severe criticism of the ‘feebleness and falseness’ of the king of Oude.

And with the characteristic duplicity that defined the era of the British East India Company, Dalhousie noted, ‘the King of Oude having permitted the rise of the present disorders at Awudh near to Fyzabad and having permitted flagrant wrong to be done to the Hindoos, not only contrary to the advice of the resident, but in defiance of his warnings and his resistance, the British troops ought upon no account to be moved to the assistance of the royal troops if hostilities should again break out at Awudh’. If Orr and Hearsey had refrained from interfering in the July clash because of being ‘few in number’, now they were explicitly ordered to stay out of it. Dalhousie seemed to have been hoping that Awadh would soon be engulfed in communal bloodshed, and to make sure it was not impeded by the interference of British troops, he directed his officers to stand by, just as they had done in July when Shah Ghulam Hussein had attacked Hanumangarhi. At that time, it was Muslims who had been massacred. But for Dalhousie, it was not Hindu versus Muslim or right versus wrong. The sole concern was how to justify the annexation of Awadh by the British government.

Wajid Ali Shah’s decision to dispatch Hindu troops for the protection of Hanumangarhi was lauded by Dalhousie. That rare praise was overshadowed by his severe criticism of the ‘feebleness and falseness’ of the king of Oude. And with the characteristic duplicity that defined the era of the British East India Company, Dalhousie noted, ‘ …the British troops ought upon no account to be moved to the assistance of the royal troops if hostilities should again break out at Awudh.’

Therefore, the main purport of his note was the Treaty of 1801, which gave control of more than half of Awadh’s richest cultivable lands in return for an annual stipend to the nawab of Awadh. It also bound the British to defend Awadh against external and internal aggressions. This, technically, stood in the way of the annexation of Awadh, even though many British acts of omission and commission had left the treaty all but abrogated. Now, in the event of the explosion of further violence between Hindus and Muslims, the British would have found a dramatic justification to annex the province. Towards that end, it was also imperative that communal anarchy defeat the writ of the king of Awadh as well as its largely harmonious social culture.

In the event of the explosion of further violence between Hindus and Muslims, the British would have found a dramatic justification to annex the province. Towards that end, it was also imperative that communal anarchy defeat the writ of the king of Awadh as well as its largely harmonious social culture.

Therefore, upon receiving Outram’s letter dated 17 October, Dalhousie must have felt a tinge of disappointment. Outram, who was cast in the same colonial die as his Governor General, reported two instances of Muslim landords refusing to join the maulvi’s crusade. One of them, Shujat Ali of Masauli in Barabanki district, was said to have declared to the maulvi that ‘he said his prayers five times a day, and kept all fasts like a true Moslem, but as to disobeying the order of the King who is a true believer like himself, or going to certain death at Ajoodhea, he chose to decline’. Razabaksh, another Muslim landholder in Barabanki, rejected the maulvi’s inducements on similar grounds. It was not just a sense of communal harmony that drove the general public and landlords to snub Ameer Ali. The king of Oude had issued a proclamation warning all who supported the fanatic crusade of dire consequences. The proclamation and its translation were made available to Outram who forwarded it to Calcutta on 18 October. The proclamation stated:

‘ …that whoever may have ventured to quit his Amaldaree, Talookdaree, or Zamindarees to join the rebels shall have his houses and property seized by our soldiers, and whoever may be on the point of going to the rebels is to be restrained, and wherever either of the above-mentioned parties presumes to refuse obedience to our orders or to abandon his vile intentions, shall be punished by the imprisonment of his family and relatives who are to be forwarded to the capital, and by the demolition of their houses and property; whoever chooses to return home in peace shall not be molested in any way… ’

The king of Oude had issued a proclamation warning all who supported the fanatic crusade of dire consequences.

On 19 October, Outram had reported to Calcutta that the maulvi had decided to proceed with his march towards Ayodhya and was ready to battle the king’s troops if they tried to stop him. Unaware of either the proclamation or the maulvi’s march, the secretary to the Government of India at Fort William in Calcutta had dispatched a set of instructions to Outram in Lucknow on 20 October. They wanted him to clearly state to the nawab of Awadh that the government would never agree to a second commission, and even if formed, ‘the Government will never approve of a mosque being built in the Hanooman Ghuree or near to it’.

The king’s proclamation was successful in restraining Muslims from joining Ameer Ali’s jihad. A letter from Outram, dated 6 November, notes ‘that the effect of the proclamation has been most satisfactory, scarcely an individual from the British districts [land ceded under the Treaty of 1801] having joined the large assemblages of Mahomedans or Hindoos which have been threatening the peace of Oude for some time past’. Outram was now ‘hopeful’ of a speedy and peaceful resolution of the dispute, and he was ‘happy’ to report it (like now, it wasn’t uncommon then for official communication to be ‘tracked’ or even leaked by couriers for a good reward. Therefore, non-secret official letters seldom contained anything that might indict the government in any way). But it would have been a cause of some alarm for the Governor General who was banking on an imminent breakdown of peace and order.

The next day (7 November) began unexpectedly for the British troops and officers who were tasked with monitoring Maulvi Ameer Ali and his zealous followers. For the maulvi it was the day of reckoning which began in a planned way. At Dariabad, he gave the slip to the British troops led by Colonel Barlow and got a lead of an hour before his absence was discovered. The maulvi’s plan seems to have been to attack Hanumangarhi on Diwali, which was going to fall on 9 November. The maulvi’s selection of the day could have not been loaded with more symbolism. Diwali marks the day Ram, the exiled prince of Ayodhya, returned home after defeating Ravan at the culmination of fourteen years of banishment, along with his wife Sita and brother Lakshman. In Ayodhya, the day before Diwali is celebrated as Hanuman Jayanti, or the birthday of Hanuman. Unlike in the rest of the country where Hanuman Jayanti falls in the summer, in Ayodhya it is pegged to Diwali which falls in the winter.

According to an account written by a junior officer named Lieutenant Catania, British troops caught up with the maulvi’s militia at Dhaurahra, a small village situated near Rudauli. Ameer Ali’s force of ghazis was resting under the shade of some trees when Colonel Barlow sent some Indian troopers to tell him to return to Dariabad, and ‘that if he persisted to advance’, they would fire on him. The maulvi defied the warning and resumed the march after midday prayers. Catania writes:

‘ …the 2-9 Pounders attached to our Corps were the only guns that had come up, the rest with the Najeebs and other Telangah Regiments not having arrived. They were immediately placed into position, and laid by Col. Barlow, the Infantry supporting them, the order to fire was given as soon as the enemy was within range, they as instantaneously returned the compliment, and thus the action became general.’

Maulvi Ameer Ali got his head cut off by an Indian sepoy, all other recruits of his cause fought to the death, asking for no quarter nor giving one. In this way Barlow, Catania and their force of 300 soldiers, Indian and British, had successfully eliminated the threat of the maulvi’s band of ‘fanatics’ in a bloody battle near Rudauli which lies nearly 40 kilometres from Faizabad. Lasting for two hours, it ended with the death of Ameer Ali and more than 400 of his followers. About eighty men belonging to the other side were also killed. Ameer Ali’s dead were buried in four large pits in nearby Rudauli. The British-led troops, too, were exhausted by the long and bloody day. Most had had nothing to eat. After the battle they marched on to camp at Mahmudpur where they took care of their dead and wounded. It is here that Catania recorded the details of the battle and its aftermath on 8 November, the eve of Diwali. In the letter detailing this narrow and lucky victory, he indicted the nawab’s troops for not showing up. This battle would be an enduring end of the conflict over Hanumangarhi but that night, on the eve of Diwali, Catania feared a reprisal and an unprecedented outbreak of communal violence. He wrote, ‘it is rumoured that affairs are not yet settled and the Mahomedans are again assembling, if this prove correct, I fancy we have yet a great deal to do’. Soon after receiving Catania’s letter, Lucknow Resident Outram travelled to the British headquarters at Fort William in Calcutta.

Barlow, Catania and their force of 300 soldiers, Indian and British, had successfully eliminated the threat of the maulvi’s band of ‘fanatics’ in a bloody battle near Rudauli which lies nearly 40 kilometres from Faizabad. Lasting for two hours, it ended with the death of Ameer Ali and more than 400 of his followers. About eighty men belonging to the other side were also killed.

Some citations have been removed from this excerpt to make for smoother reading. You will find all of them in the book.

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of Valay Singh. You can buy Ayodhya: City of Faith, City of Discord here.

Valay Singh is an independent journalist based in Delhi. He began his career with NDTV 24×7 as a researcher and editor.

He has been widely published in newspapers and magazines like the Economic Times, Himal Southasian, The Wire, DailyO, and Outlook. Ayodhya: City of Faith, City of Discord is his first book. You can read more of his work here, here and here.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |