An Illustration to the Mahabharata: The Pandava and Kaurava armies face each other

“The line between justified force and unjustified violence is difficult to draw and depends on perspective,” writes Upinder Singh, in her book ‘Ancient India: Culture of Contradictions’. “Violence is difficult to define.”

History is biased by politics and it has come to pass, time and again, that politically charged narratives of history summon up a memory of the ancient Indian past in the form of a peaceful, non-violent ‘golden age’. In his essay ‘The “Golden Age” and National Renewal’, Anthony D Smith writes, “ …[for] Indian nationalists, …the post-Vedic era of classical city-states marked the apogee of Hindu Indian civilization… The fact that this… excluded Muslims and Sikhs and their golden ages, only served to strengthen the exclusive and hegemonic tendencies in Indian nationalism.”

It is presumed often enough, in popular discourse, that this golden era came to an end after what is perceived as a ‘Muslim invasion’ of ‘Hindu India’.

This golden age theory has been challenged by historians, time and again. DN Jha in his book ‘Against the Grain: Notes on Identity, Intolerance and History’ challenged the depiction of the “ancient period of Indian history as a golden age marked by social harmony devoid of any religious violence”. According to him, this supposed era of peace enabled Hindutva ideologues to “portray the middle ages as… a reign of terror unleashed by the Muslim rulers on Hindus”.

Singh, like Jha, examines the history of religious violence, but she also shines a spotlight on ‘political violence’, and violence by the state, in ancient India.

“Some of the evidence for violence in ancient India is so obvious that we may wonder why we never noticed it,” Singh writes. “Some has to be prised out because the sources are past masters at concealing violence and transforming it into something else— something desirable, necessary, even beautiful.”

To challenge the notion that Indian civilisation has been essentially non-violent since its inception, Singh takes us back to the prehistoric period, exemplifying the prevalence of violence through the hunting scenes that dominate Stone Age art. She questions the theory that Harappan culture was peaceful, on the basis of finds of weaponry and walled citadels. Moving on, she cites examples from Rig Vedic hymns that have clear references to violent conflicts between tribes (Aryas and Dasyus). Even the royal rituals (Rajasuya, Ashvamedha and Vajapeya) “must have been scripted on the lines of actual, bloody contests for power”.

And so, with the help of textual and archaeological evidence of warfare, and struggles that involved blood-shed, Singh takes us through a telling tour of the rise and fall of empires in ancient India. The story of Magadha, for instance, involves patricide, following which, the Shaishunaga dynasty also meets a violent end. Then come the Nandas, who are subsequently overpowered by the Mauryas. Chandragupta and his son Bindusara fight wars to expand the Maurya empire. And while the third Mauryan king, Ashoka, may have come down to us in history as a pacifist and patron of Buddhism, “The four-year gap between his accession and consecration and the reference in Buddhist texts to his killing ninety-nine brothers (clearly hyperbole!) suggest a prolonged and violent succession struggle.”

The political history of South India is no less non-violent. Arguing that war was, indeed, central to ancient Indian political culture, Singh elaborates on the ‘puram poems’ of the Sangam corpus that “attach great value to a heroic death”.

That war was also essential for the obeying of one’s “dharma” is evident from the emphasis placed on the same in the two epics— Mahabharata and Ramayana. “Dharma is complicated,” writes Singh. “Nothing illustrates this better than what transpires over eighteen days at Kurukshetra. War is the stage on which many questions related to human existence are asked and answered, often inconclusively.”

How, then, despite the wars and violence, has India’s ancient past come to be associated with non-violence? Should political violence, or violence by the state, be overlooked?

Singh writes: “There is no such thing as a non-violent war… The functions of the prashasti (praise of the king) in royal inscriptions include giving an impression of smooth and seamless political transitions; concealing violent intra-dynastic conflicts; celebrating the king’s military victories and omitting his defeats; and tempering his martial image and achievements with pacific and benevolent attributes. So the increase of political violence was accompanied by increasingly sophisticated attempts to legitimize, invisibilize, and aestheticize it.”

Nevertheless, when it comes to violence by the state, Singh reminds us that apart from warfare, certain forms of “coercion and violence were, and still are, inherent in the state”. The relationship between a king and his subjects has been highlighted in several ancient texts. Extracting taxes from subjects on a regular basis, and harnessing labour for state projects were two very common activities that linked the state directly to the subjects. Both usually involved coercion from the state.

While ancient texts may conceal a state’s coercive power, it is quite evident from the prescribed punishments, demarcated as per the subject’s wrong-doing, that the state was violent. This power of the state has been discussed in the Arthashastra. Punishments, Singh writes, included “fines, confiscation of property, exile, corporeal punishment, mutilation, branding, torture, forced labour, and death.” The Arthashastra also refers to capital punishment, “distinguishing between shuddha-vadha (simple death), and chitra-vadha (death by torture)”.

“Given the pervasiveness of warfare and the force or threat of force implied in systems of taxation and justice, violence can indeed be described as an intrinsic part of human history, and ancient India is no exception,” writes Singh.

Ancient Indian sources hardly mention any popular rebellions against the state. Does this mean that ancient Indians never questioned the oppression of their rulers? Singh argues that there could be other possible reasons: “The concealment of such incidents by the sources; the effectiveness of the state’s coercive and repressive machinery in preventing and crushing any resistance; and the absence of collective will, resources, and organization that would have enabled the victims of state oppression to come together and revolt against the state.”

A few incidents of violent rebellion are, however, known in early medieval India. The Kaivarta rebellion in eastern India in the late eleventh century and the Damara rebellion in Kashmir are examples. But were these ‘popular’ in nature? Singh disagrees. On the contrary, she cites a thirteenth-century inscription from Karnataka which states that when farmers protested against their village being converted into a brahmadeya (Brahmana village) a royal army was sent to punish them.

“Then, as now, farmers were no match for an all-powerful state,” Singh writes. But then again, since the publishing of her book ‘Ancient India: Culture of Contradictions’, three contentious farm laws have been repealed. The book however, including the excerpt we have reproduced below, remains searingly relevant. Not just for historical misconceptions that need clearing, but for lessons we urgently need to imbibe from our past.

Like inequality, violence too has always been a part of human history, although its forms, scale, and intensity have varied. The advent of the state ushered major changes in the structures for its perpetuation and control. The theory that the Harappan civilization was a peaceful culture held together by tradition rather than force can be questioned on the basis of finds of weaponry and walled citadels. In later centuries too, cities continued to be surrounded by fortification walls, indicating the need for defence against military attack.

As discussed in Chapter 1, Rig Vedic hymns contain many references to violent conflicts among the arya tribes and between the aryas on the one hand and dasas and dasyus on the other. Later Vedic royal rituals such as the rajasuya, ashvamedha, and vajapeya, which included ritual contests between the king and his kinsmen, must have been scripted on the lines of actual, bloody contests for power. Aryavarta, a land inhabited by the culturally superior aryas, was distinguished from that of the uncivilized people of the east. The aryas also distinguished themselves from mlechchhas or barbarians, a category that included foreigners and tribals. Apart from the textual references to warfare, weapons found at archaeological sites in various parts of India in second and first millennium BCE contexts indicate the endemic nature of war.

The sixth/fifth century BCE was not only the age of Mahavira and the Buddha; it was also a period of warring states. The sixteen mahajanapadas (great states) included rajyas (kingdoms) and ganas or sanghas (oligarchies) which were constantly engaged in internecine war. This was a period of military transition when hereditary warriors were being increasingly replaced by a recruited and salaried class of soldiers. The story of the rise of the kingdom of Magadha in eastern India is a bloody one. Bimbisara, king of the Haryanka dynasty, had the title ‘Seniya’ (one who has an army). He is said to have been killed by his son Ajatashatru, and the latter’s four successors were also patricides. The short-lived Shaishunaga dynasty that followed met a violent end. Then came the Nandas. Mahapadma, the first Nanda king, was militarily successful and expanded the Magadhan kingdom. Dhanananda, the last Nanda ruler, was greedy, cruel, and unpopular and was overthrown by Chandragupta Maurya. Chandragupta and his son Bindusara fought wars to expand the Maurya empire. The third Maurya king, Ashoka, is known in history for his pacifism and patronage of Buddhism, but the four-year gap between his accession and consecration and the reference in Buddhist texts to his killing ninety-nine brothers (clearly hyperbole!) suggest a prolonged and violent succession struggle. When the curtain rises on the political history of early historic South India in the third century BCE, it reveals the Chola, Chera, and Pandya kings warring among themselves and with many less powerful chieftains.

The sixth/fifth century BCE was not only the age of Mahavira and the Buddha; it was also a period of warring states. The sixteen mahajanapadas (great “states) included rajyas (kingdoms) and ganas or sanghas (oligarchies) which were constantly engaged in internecine war. This was a period of military transition when hereditary warriors were being increasingly replaced by a recruited and salaried class of soldiers.

It would be tedious (and unnecessary) to list all the wars fought in ancient India. The pervasiveness of violence and war is woven into the history of the rise and fall of dynasties, kingdoms, and empires over the centuries. There is no eye-witness reportage, but it can be assumed that ancient wars involved killing, looting, and raping. This is what armies have often been known to do, across cultures, across time. There is no such thing as a non-violent war. Ancient warfare would also have involved capturing prisoners of war and reducing them to slavery. The functions of the prashasti (praise of the king) in royal inscriptions include giving an impression of smooth and seamless political transitions; concealing violent intra-dynastic conflicts; celebrating the king’s military victories and omitting his defeats; and tempering his martial image and achievements with pacific and benevolent attributes. So the increase of political violence was accompanied by increasingly sophisticated attempts to legitimize, invisibilize, and aestheticize it.

There is no such thing as a non-violent war. Ancient warfare would also have involved capturing prisoners of war and reducing them to slavery. The functions of the prashasti (praise of the king) in royal inscriptions include giving an impression of smooth and seamless political transitions; concealing violent intra-dynastic conflicts; celebrating the king’s military victories and omitting his defeats; and tempering his martial image and achievements with pacific and benevolent attributes. So the increase of political violence was accompanied by increasingly sophisticated attempts to legitimize, invisibilize, and aestheticize it.

Apart from warfare, certain forms of coercion and violence were, and still are, inherent in the state. Throughout history, states have been based on the systematic appropriation of economic and human resources from subjects. There may be no agricultural tax in India today, but in ancient Indian agrarian societies, rulers took a share of the surplus agricultural produce in the form of taxes. Extracting taxes on a regular basis involved coercion and the threat or actual use of force. The harnessing of labour for state projects also involved coercion.

Theories of the origin of kingship in the Agganna Sutta of the Buddhist Digha Nikaya and the Shanti Parva of the Mahabharata highlight the relationship between the king and his subjects. They describe people handing over taxes to the king in return for his performing certain duties, especially maintaining social order and preventing crime and violence. Many texts describe one-sixth of the produce as the king’s share and advise the ruler to be fair and moderate while levying taxes. This fiction of a voluntary social contract between the king and his subjects deliberately conceals the coercion that was involved in making farmers pay taxes.

Violence was also inherent in the interactions of ancient Indian states with forest people. The expansion of agriculture, cities, and states involved a steady clearance of forests, but the most massive forest clearance took place in the middle of the nineteenth century as a result of population increase, commercial farming, and the expansion of the railways. Till then, states lived cheek by jowl with forest tribes. Extracting and controlling valuable economic and military resources like wood, ivory, and elephants involved a steady encroachment on forest habitats and constant conflicts with forest people. The forest was an important object of the exploitation and violence of the state; but it was also a constant source of violent challenge to the state. The term mlechchha included tribals as well as foreigners and presented them as a threat to ‘civilized’ people. But it could also be used to justify the use of violence against tribals and foreigners. One of the theories of the origins of kingship in the Mahabharata (discussed later in this chapter) mentions the Nishada and indicates a recognition of the political importance of forest tribes.

While ancient texts conceal the coercive element involved in taxation and the state’s interface with forest people, they loudly proclaim that the king’s use of danda (literally the rod; by extension, force or punishment) is essential to maintain social order. A favoured metaphor for chaos in ancient texts is matsya-nyaya, literally, the law of the fish, a situation where the big fish eat the small fish, that is, where the mighty oppress the weak. We do not know the details of the mechanisms for settling civil and criminal disputes in ancient times, but the development of a judicial system (howsoever rudimentary) gave the state and its agents the right to adjudicate civil and criminal disputes and to impose punishment, even death. The king’s rod is said to inspire fear in people and prevents them from committing crimes. But all ancient texts emphasize that a ruler must use the rod in accordance with the principles of justice.

While ancient texts conceal the coercive element involved in taxation and the state’s interface with forest people, they loudly proclaim that the king’s use of danda (literally the rod; by extension, force or punishment) is essential to maintain social order. A favoured metaphor for chaos in ancient texts is matsya-nyaya, literally, the law of the fish, a situation where the big fish eat the small fish, that is, where the mighty oppress the weak.

The power of the state to punish subjects is discussed in great detail in the Arthashastra. Although there is little evidence suggesting that the ‘laws’ contained in this text were actually used in civil or criminal cases, they are important for the history of legal ideas. The system of criminal and civil law in the Arthashastra involves judges, with the king theoretically presiding over the justice system at a higher level. Punishments include fines, confiscation of property, exile, corporeal punishment, mutilation, branding, torture, forced labour, and death. Torture is both a punishment and a means of acquiring information during interrogation and includes striking, whipping, caning, suspension from a rope, and inserting needles under the nails. The Arthashastra also refers to capital punishment, distinguishing between shuddha-vadha (simple death), and chitra-vadha (death by torture). The latter refers to painful deaths which may have involved public spectacle. They include burning on a pyre, drowning in water, cooking in a big jar, impaling on a stake, setting fire to different parts of the body, and tearing the body apart by bullocks.

To be fair to him, Kautilya was not, as is often imagined, an advocate of unrestricted or wanton state violence. In line with the larger ancient Indian political discourse, he argues that the king’s punishment must be rooted in vinaya (discipline). A ruler who imposes wrongful punishment cannot escape punishment himself. If used indiscriminately, unfairly, out of anger or malice, the rod destroys the king. In the absence of institutional checks, the political theorists sought to control the king’s propensity to exercise brute force by warning of the disastrous consequences of excessive force and by emphasizing the need for rulers to be wise, educated, disciplined, and receptive to good advice.

Given the pervasiveness of warfare and the force or threat of force implied in systems of taxation and justice, violence can indeed be described as an intrinsic part of human history, and ancient India is no exception.

Given the pervasiveness of warfare and the force or threat of force implied in systems of taxation and justice, violence can indeed be described as an intrinsic part of human history, and ancient India is no exception.

Beyond the pervasiveness of warfare in ancient Indian political history, I would like to suggest that war was central to ancient Indian culture (as it was to many other cultures). It is impossible to imagine the Sanskrit epics—Mahabharata and Ramayana—without war. The oldest Tamil literature, the Sangam poems, also reflect a warrior ethos. In these and other texts, war forms a context within which many other important issues are discussed—human relationships, social duty, the goals of life, happiness, death and its aftermath, heaven and hell, and the relationship with the gods. The ideas and values represented in such texts must have percolated down to various strata of society.

The puram poems of the Sangam corpus attach great value to a heroic death. Bravery in battle was an attribute of masculinity, cowardice a source of shame. The spirit of a warrior who died in battle was believed to dwell in paradise. Consider the following poem, supposed to have been written by a poetess:

Many said,

That old woman, the one whose veins show

on her weak, dry arms where the flesh is hanging,

whose stomach is flat as a lotus leaf,

has a son who lost his nerve in battle and fled.

At that, she grew enraged and she said,

‘If he has run away in the thick of battle,

I will cut off these breasts from which he sucked,’

and, sword in hand, she turned over fallen corpses,

groping her way on the red field.

Then she saw her son lying there in pieces

and she rejoiced more than the day she bore him.

Bodies of warriors who did not die in battle were cut with swords before the funerary rites, in order to simulate death in battle. At times, kings who had been defeated in war committed ritual suicide through starvation, accompanied by their near and dear ones. A poet describes King Kopperuncholan performing this act after defeat in war; he is grief-stricken that the king had not asked him to accompany him into death.

Hero Stone with a 1286 AD old Kannada inscription during rule of Yadava King Ramachandra in the Kedareshvara Temple, Balligavi, in Shimoga district, Karnataka

Sangam poems speak of memorial stones known as natukal and virakal set up in honour of heroes who had died fighting. These stones were decorated with garlands and peacock feathers; the warrior’s weapons were sometimes placed beside them. The spirit of the dead hero was believed to reside in the stone and it was worshipped with ritual offerings of rice balls, liquor, and animals.

Apart from poetry, hero stones (mentioned in Chapter 3) commemorating the death of men in battles proliferated over the centuries, not only in South India, but also in other parts of the subcontinent. The events they commemorated were usually not the large-scale wars celebrated in royal inscriptions but small-scale local events, often cattle raids, that were important in the life and historical memory of villagers and local communities. These stones consist of one or more carved panels and are usually uninscribed. It is not easy to date them, but the practice seems to go back to the third century BCE. More elaborate hero stones make their appearance in the third and fourth centuries CE, for instance at Nagarjunakonda in the Krishna valley. Here, at the site of the ancient Ikshvaku capital of Vijayapuri, there are a large number of memorial pillars commemorating the heroic death of army generals and groups of soldiers.

Although the details of the beliefs and customs associated with them must have varied across time and regions, the thousands of hero stones found in various parts of India reflect the pervasiveness of ideas of masculinity and honour that valorized a violent, heroic death.

The close connection between war and social values is expressed more eloquently in the various tellings of the Mahabharata and Ramayana, which had great cultural impact across India and Southeast Asia. The Mahabharata was probably woven around the memory of an actual conflict between warring kin and reflects the rivalry that must have commonly existed among ruling elites. The war at Kurukshetra is said to have been one of many episodes of conflict between gods and demons, a dharma-yuddha (righteous war). This is because it was fought for Yudhishthira’s right to the throne (he was the eldest son); the Pandavas were semi-divine; and the god Krishna fought on their side. But the ideas about this dharma-yuddha are accompanied by questions and doubt which bring out the problematic nature of both dharma and war. The Mahabharata combines the old idea of the Kshatriya warrior whose aim was to die in battle and attain heaven with a newer, higher goal—moksha. In the epic, war becomes a setting that triggers discussion and debate about many other profound issues, especially dharma. All important issues have to be sorted out in the face of possible death on the battlefield, after which no further discussion and debate would be possible.

The Mahabharata combines the old idea of the Kshatriya warrior whose aim was to die in battle and attain heaven with a newer, higher goal—moksha. In the epic, war becomes a setting that triggers discussion and debate about many other profound issues, especially dharma. All important issues have to be sorted out in the face of possible death on the battlefield, after which no further discussion and debate would be possible.

The relationship between war and dharma is best illustrated in the Bhagavad Gita, which brings together many diverse philosophical strands to create a new synthesis. The narrative setting of the battlefield is dramatic. Arjuna stands in his chariot and sees his kin, teachers, and friends arrayed before him. His mouth goes dry, his body feels weak and tremulous, his bow slips from his hands. He is assailed by a terrible confusion. Killing is not the problem; that is what Kshatriyas do. It is the killing of one’s own people (sva-jana)—one’s close relatives, teachers, and friends—that is problematic. The killing of kin leads to the destruction of the kula (lineage), the corruption of its women, and social chaos. Surely, fighting such a war would be a papa (great sin). Arjuna expresses these misgivings to his charioteer, Krishna. He puts away his bow and arrows, sits down in his chariot, and says that he will not fight.

The rest of the Bhagavad Gita consists of Krishna’s teaching to Arjuna. One must follow one’s dharma (sva-dharma), that is the dharma of the varna one belongs to. A warrior who dies fighting in such a dharma-yuddha will attain heaven and eternal fame. Turning away from battle will result in shame and infamy, which is much worse than death. Killing the enemy is not something to feel sorrowful about because death is inevitable. In any case, it is only the physical body of the enemy that is killed; the embodied self (atman) is indestructible and eternal.

“Weapons do not pierce this (the embodied Self), fire does not burn this, water does not wet this, nor does the wind cause it to wither.

This cannot be pierced, burned, wetted or withered; this is eternal, all pervading, fixed; this is unmoving and primeval.”

A wise man performs his duty with complete mastery over his senses, unconcerned about their consequences. This is desireless action.

Krishna also uses the argument of bhakti. If Arjuna seeks shelter in him (Krishna), is absorbed in him (Krishna), in return, he (Arjuna) will be set free from all sin. Arjuna’s doubts are removed and he picks up his bow and arrows, ready to fight. The Pandavas ultimately win the war at Kurukshetra, but it is after a great deal of slaughter, and they do not live happily ever after. Although the Mahabharata contains a powerful philosophical justification of war, it also contains in its eleventh book, the Stri Parva, a powerful lament on its consequences.

While the Mahabharata war is fought between two confederate armies for the sake of a kingdom, in the Ramayana, none of the princes hanker for the throne. Rama goes to war to rescue his beloved wife Sita, who has been abducted by Ravana, the demon king of Lanka. This war too is presented as another round of the conflict between the gods and demons. Rama and his three brothers are parts of Vishnu. Rama’s birth as a man is part of a divine plan to kill Ravana, who has created mayhem by obstructing the activities of the gods, Brahmanas, gandharvas, yakshas, and sages. But this war is very different from the one fought at Kurukshetra. Rama and Lakshmana set out for the island of Lanka seated on the shoulders of the vanaras Hanuman and Angada, their army consisting almost entirely of vanaras. The vanaras are monkeys only in appearance—they are actually the sons of various gods and have been created in order to help Rama defeat Ravana.

Epic Tales from Ancient India. Paintings from The San Diego Museum of Art

Both epics have the idea of a code of honour in battle but acknowledge the occasional need to resort to unfair practices to achieve one’s goals. Rama transgresses the warrior’s code when he shoots the vanara Vali in the back while the latter is fighting Sugriva. But by and large, Rama is presented as compassionate even towards his enemies. The practice of deceit for the sake of victory is much more pronounced in the Mahabharata, and it is practised by both sides. The Pandavas rattle and then kill Drona by announcing that Ashvatthama—the name of Drona’s son, but also that of an elephant that Bhima had killed for the deceit—is dead. Karna is killed while trying to free his chariot wheel from the mud. Bhima kills Duryodhana by giving a low blow to his thigh. As the Pandavas shamefacedly watch Duryodhana die, recalling all their transgressions of the warrior’s honour code, Krishna offers a justification. The Kauravas were militarily stronger and could not have been defeated in fair fight; that is why he had devised these strategies.

“You should not take it to heart that this king [Duryodhana] has been slain, for, when enemies become too numerous and powerful, they should be slain by deceit and strategems. This is the path formerly trodden by the gods to slay the demons; and a path trodden by the virtuous may be trodden by all.”

Dharma is complicated. Nothing illustrates this better than what transpires over eighteen days at Kurukshetra. War is the stage on which many questions related to human existence are asked and answered, often inconclusively.

Dharma is complicated. Nothing illustrates this better than what transpires over eighteen days at Kurukshetra. War is the stage on which many questions related to human existence are asked and answered, often inconclusively.

The importance of war in ancient Indian politics is clear from the fact that political theorists discuss it in great detail. War is the subject of Book 10 of the Arthashastra but is also a prominent subject of discussion in several other books. In fact, it seems that the analysis of war was one of Kautilya’s important contributions to the discussion of statecraft. The theory of the raja-mandala (circle of kings) presumes the existence of multiple warring states, vying for political supremacy. Kautilya advises the vijigishu—the king desirous of victory—on how to overreach his rivals and become the hub of the circle of kings, that is, to attain paramountcy.

The theory of the circle of kings is connected to the six measures (gunas) of inter-state policy and the four expedients (upayas). The six measures are peace/treaty (sandhi), war/initiating hostilities (vigraha), staying quiet (asana), initiating a military march (yana), seeking shelter (samshraya), and the dual policy of peace or treaty with one king and war against another (dvaidhibhava). The four expedients are an important part of governance as well as the conduct of inter-state relations; they comprise pacification (sama), giving gifts (dana), force (danda), and creating dissension (bheda).

Apart from military strategy, the Arthashastra has a great deal to say about the organization of the army. It talks of the four-fold army (chaturanga-bala) consisting of infantry, cavalry, chariot wing, and elephant corps. It lists six types of troops (bala)—hereditary (maula), hired (bhrita), banded (shreni), ally’s (mitra), alien (amitra), and forest (atavika). Hereditary troops are considered the best and forest troops the worst. Battle arrays, siege tactics, salaries, and keeping soldiers happy and loyal are important issues that are addressed. Kautilya talks of the harassment and oppression of the people as a result of war. According to him, the harassment inflicted on the people by another’s army is worse than that inflicted by one’s own army. The harassment by the enemy’s army afflicts the entire land, ruins it through plunder, killing, burning, destruction, and deportation. The destruction of the enemy’s crops in the course of the march is mentioned. Plunder is part of warfare and Kautilya suggests how to divide it up among confederate armies. But according to Kautilya, war must never be waged without a careful cost-benefit calculation. If the gains of war and peace are likely to be similar, the king should opt for peace, because war has many negative results.

Kautilya gives a basic three-fold classification of war—prakashayuddha (open war), kuta-yuddha (crooked war), and tushnim-yuddha (silent war). Open war is when fighting takes place at a designated and announced time and place. Crooked war involves creating fright, sudden assault, striking when there is an error or calamity on the enemy’s side, and retreating and then striking at the same place. All these tactics have the element of sudden, unexpected attack. Silent war includes pretence, ambush, and luring the enemy’s troops with the prospect of gain. It involves the use of trickery, secret practices, and instigation. There is also a fourth type of war—mantra-yuddha (diplomatic warfare). This involves discussion, persuasion, and negotiation with the enemy, as opposed to military action. Kautilya talks of three kinds of victors. The dharma-vijayi (righteous victor) is satisfied with submission. The lobha-vijayi (greedy victor) is satisfied with the seizure of land and goods. The asura-vijayi (demonic victor) is only satisfied with seizing the enemy’s land, goods, sons, wives, and life. But apart from this passing reference to dharma-vijaya, the Arthashastra is more concerned with victory than honour.

While Kautilya has no compunctions about the use of force to attain political ends, he also warns of its dangers. Going against the other experts, he argues that mantra-shakti (the power of counsel) is superior to prabhu-shakti (military might) and utsaha-shakti (the power of energy). He also suggests that the results of war can be achieved through other means, including marriage alliances, buying peace, and assassination. Other recommended ways of dealing with enemies include the use of poison, magic, spells, and charms. Kautilya views judicious force as one of the many ways whereby the vijigishu can achieve his political aims, but force should always be a last resort. A ruler’s greatest weapon is his intellect.

Many centuries later, another political theorist, Kamandaka, wrote a work titled the Nitisara. This too discusses war. It details the uncertain and possibly disastrous results of war, especially one launched hastily without due consideration and consultation. Kamandaka lists sixteen types of war that should not be fought. War is a risky business and should hence be avoided by a prudent king. ‘As victory in war is always uncertain, it should not be launched without careful deliberation.’ War, Kamandaka asserts, has inherently disastrous doshas (qualities). While Kautilya urges caution in war, Kamandaka expresses stronger reservations. But war is still considered an integral part of politics and the aim is carefully calculated military victory.

Political theorists deliberated on the nature and conduct of war. Poets, playwrights, royal biographers, and composers of royal inscriptions celebrated the military prowess and victories of kings. Through an elegant sleight of hand, they divested war of its ugliness and violence and presented it as something necessary, desirable, even beautiful. Two examples of this stand out—the Allahabad pillar inscription of Samudragupta and the Raghuvamsha of Kalidasa.

Political theorists deliberated on the nature and conduct of war. Poets, playwrights, royal biographers, and composers of royal inscriptions celebrated the military prowess and victories of kings. Through an elegant sleight of hand, they divested war of its ugliness and violence and presented it as something necessary, desirable, even beautiful. Two examples of this stand out—the Allahabad pillar inscription of Samudragupta and the Raghuvamsha of Kalidasa.

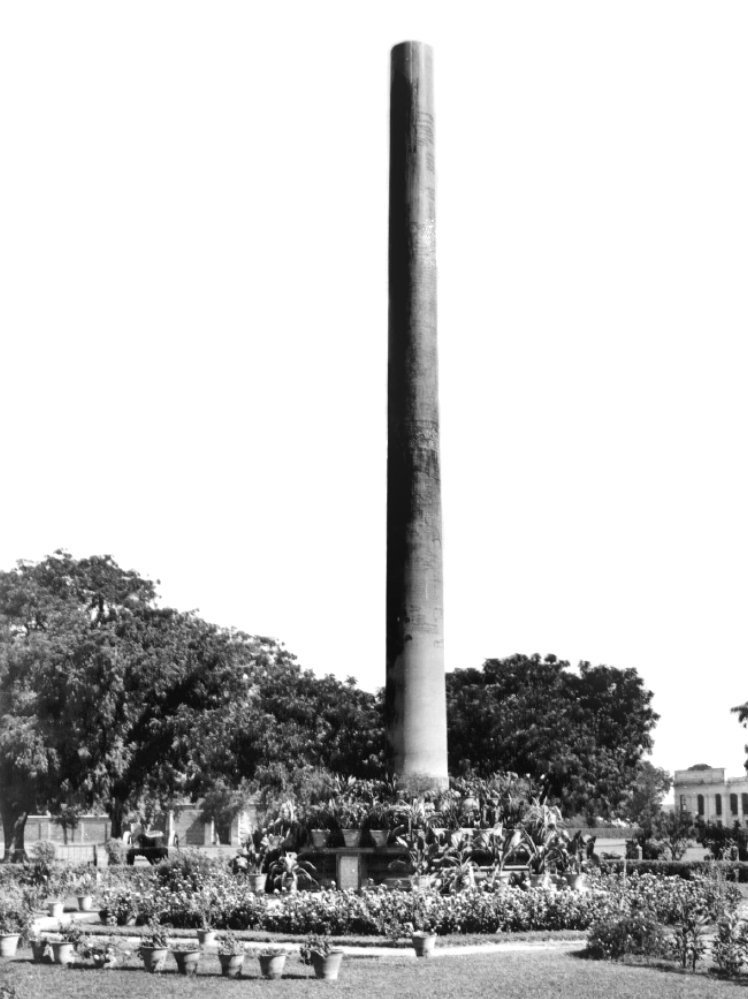

A remarkable sandstone pillar, presently standing in the Allahabad Fort, bears inscriptions of four emperors—a set of six edicts and two minor pillar edicts of the Maurya emperor Ashoka; a prashasti paneygyric) of the Gupta emperor Samudragupta; and an inscription of the Mughal emperor Jahangir. The inscription of Samudragupta (c. 350–370 CE) was composed by Harishena, a high-ranking official and military commander.

The Allahabad Pillar, in Allahabad. Photo, Circa 1900 . The pillar also contains inscriptions on Samudragupta and Jahangir. The pillar is made of polished stone, extends 10.7 m in height and is incised with an Ashokan edict.

Samudragupta’s martial qualities and achievements are described in detail in the Allahabad pillar inscription. Harishena’s achievement was to give an account of Samudragupta’s irresistible and spectacular wars and successes, which, at first glance, gives the illusion of his being emperor of the whole subcontinent, but on closer reading, presents a more complex and limited picture of the empire. Also striking is the way he aestheticizes war. He describes the king as one who has engaged in hundreds of battles, and whose body is beautiful on account of being covered with hundreds of scars caused by various types of enemy weapons. This is a king whose ‘…fame has tired itself with a journey over the whole world caused by the restoration of many fallen kingdoms and overthrown royal families.’ But the references to the king’s many military victories are regularly punctuated by references to his non-martial qualities and achievements.

Kalidasa’s Raghuvamsha (fourth/fifth century CE) is an extremely important and influential poetic work, which deals both with the ideals and realities of kingship. It tells the history of kings of the Ikshvaku dynasty, including Dilipa, Raghu, and Rama. The fourth canto describes the digvijaya (victory over the quarters) of Raghu. Kalidasa describes this as an elaborate clockwise military circumambulation of the subcontinent. The description is marked by great poetic beauty and elegance, with references to the landscape, trees and flowers, and the produce of various regions. By and large, Kalidasa avoids graphic descriptions of the violence of war in favour of aestheticized descriptions.

“His [Raghu’s] march was clearly marked by many kings who were dispossessed, deposed or overthrown, as the march of an elephant is marked by uprooted, broken trees, devoid of fruit.”

And yet, notwithstanding the importance of victories in battle, Kalidasa makes it clear that great kings do not seek political paramountcy for the sake of land or riches but for the sake of fame. Nor do they cling to power. After his conquest of the quarters, Raghu performs a grand sacrifice called the vishvajit (victory over the world) in which he uses up all the wealth he had obtained in his wars. Having discharged his duties, Raghu hands over the reins of power to his son Aja, retires from worldly life, and realizes the ultimate reality through the performance of yoga and meditation. The Raghuvamsha expresses the idea that empire involved military victories but not necessarily conquest. War is idealized and aestheticized and combined with renunciation. Its mundane objectives and violence are erased.

The upheavals of ancient Indian political history indicate that kings and dynasties faced frequent challenges from rivals. Further evidence of threats of violence against the state comes from reading between the lines of texts, especially taking note of their apprehensions, insecurities, and anxieties.

One of the accounts of the origin of kingship in the Shanti Parva of the Mahabharata talks of the gods approaching Brahma and Vishnu to intervene in order to put an end to social disorder. Vishnu produced a mind-born son Virajas, who was followed by his son Kirtiman and grandson Kardama. But these three men wanted to renounce the world and did not want to rule. Then came Ananga (who was a good king) and Atibala (who did not have control over his senses). They were followed by Vena, who was dominated by passion and hate and was unrighteous in his behaviour towards his subjects. The sages decided to get rid of him and stabbed him to death with blades of kusha grass. They churned his right thigh and out of it emerged an ugly man named Nishada who was told to go away because he was unfit to be king. Then they churned Vena’s right hand and therefrom emerged Prithu, a man with a refined mind and an understanding of the Vedas, dharma, artha, the military arts, and politics. Prithu proved to be an exemplary ruler. Although this story cannot be considered an account of historical events, it is significant for the many ideas it enfolds—kings who do not want to rule, the tension between kingship and renunciation, the inferiority of forest tribes, and the justification for killing evil kings.

The Mahabharata discusses the king’s duties and warns of the consequences of not performing them. A just king goes to heaven, one who is unjust goes to hell. There are other warnings as well:

“A cruel king, who does not protect his people, who robs them in the name of levying taxes, is evil [Kali] incarnate and should be killed by his subjects. A king who, after declaring ‘I will protect you,’ does not protect them, should be killed by his people coming together, as though he were a mad dog.”

So once again, as in the story of Vena, the epic sanctions the killing of bad kings. There are several stories in ancient Indian texts of evil men who are also kings being killed (Duryodhana, Ravana, and Kamsa are some of the well-known ones), but the overall attitude of the Mahabharata—indeed of all ancient Indian texts—is pro-government and pro-monarchy. Kinglessness is seen as the equivalent of anarchy.

The most comprehensive and pragmatic discussion of violence against the state occurs in the Arthashastra. Kautilya advocates ruthless, carefully calculated, and effective use of violence by the state in order to prevent and respond to violence against the state. Kautilya’s king lives in constant fear of assassination, especially at the hands of his wives and sons. Other threats include enemy kings, neighbouring rulers, angry subjects, forest tribes, robbers, mlechchhas, and rebellious troops. Kautilya advises the king to have an elaborate espionage system and to deal firmly with revolts and conspiracies. Those who cannot be killed openly, such as high-ranking officers, should be dealt with through upamshu-danda (silent punishment), that is, secret killing. Silent punishment can also be used against hostile subjects.

Kautilya recognizes violence against the king as a serious political problem that has to be dealt with ruthlessly and effectively through pre-emptive action, punishment, and retaliation. The punishment for one who reviles or spreads evil news about the king or reveals secret counsel is the tearing out of the tongue. More severe crimes against the king and kingdom invite more violent punishments. Death by setting fire to the hands and head is the punishment for one who covets the kingdom, attacks the king’s palace, incites forest people or enemies, or causes rebellion in the fortified city, countryside, or army. In several cases (including crimes which invite mutilation), Kautilya refers to the possibility of commuting punishments to fines. But unless there is some crucial mitigating circumstance, no commutation is suggested where the crime merits the death penalty, especially for treason or loss to the state Whether or not Kautilya’s recommendations were actually applied, we know that autocracies tend to react violently to criticism and come down hard on rebels.

Kautilya recognizes violence against the king as a serious political problem that has to be dealt with ruthlessly and effectively through pre-emptive action, punishment, and retaliation. The punishment for one who reviles or spreads evil news about the king or reveals secret counsel is the tearing out of the tongue. More severe crimes against the king and kingdom invite more violent punishments. Death by setting fire to the hands and head is the punishment for one who covets the kingdom, attacks the king’s palace, incites forest people or enemies, or causes rebellion in the fortified city, countryside, or army.

The Arthashastra contains several references to disaffection among subjects and prakriti-kopa (the anger of the people). These suggest an anxiety about the possibility of a mass rebellion of unhappy, dissatisfied subjects. But ancient Indian sources do not record a single historical instance of popular rebellion against the state. Does this mean that ancient Indians were docile and obedient, never questioning the inequities and oppression of their rulers? There are other possible reasons—the concealment of such incidents by the sources; the effectiveness of the state’s coercive and repressive machinery in preventing and crushing any resistance; and the absence of collective will, resources, and organization that would have enabled the victims of state oppression to come together and revolt against the state.

Occasionally, cracks can be seen in the façade. Land grant inscriptions routinely state that the gifted village land was not to be entered by the king’s troops. This only makes sense in a context of a military presence in the countryside. The fifth century Chammak copper plate of the Vakataka king Pravarasena II records the gift of Charmanka village to a thousand Brahmanas and states that the grant was to last as long as the sun and the moon endured (that is, forever). But it adds the curious caveat that the grant would last as long as the Brahmanas in question committed no treason against the kingdom; were not found guilty of the murder of a Brahmana, theft, or adultery; did not wage war; and did not harm other villages. If they did any of these things, the king would do no wrong in taking the land away from them. This inscription suggests that Brahmanas patronized by the king were considered capable of presenting a threat to society and to the state.

Incidents of violent rebellion are known in early medieval India, but none of them were ‘popular’ rebellions. For instance, the Kaivarta rebellion in eastern India in the late eleventh century was basically a revolt of politically powerful landowners. The Damara rebellion in Kashmir too involved powerful landlords, not ordinary folk. On the other hand, there are a few inscriptional references to agrarian conflicts, in some cases involving the state. For instance, a thirteenth century inscription from Karnataka states that when farmers protested against their village being converted into a brahmadeya (Brahmana village) a royal army was sent to punish them. Then, as now, farmers were no match for an all-powerful state.

Incidents of violent rebellion are known in early medieval India, but none of them were ‘popular’ rebellions. For instance, the Kaivarta rebellion in eastern India in the late eleventh century was basically a revolt of politically powerful landowners. The Damara rebellion in Kashmir too involved powerful landlords, not ordinary folk. On the other hand, there are a few inscriptional references to agrarian conflicts, in some cases involving the state. For instance, a thirteenth century inscription from Karnataka states that when farmers protested against their village being converted into a brahmadeya (Brahmana village) a royal army was sent to punish them. Then, as now, farmers were no match for an all-powerful state.

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of Upinder Singh and Aleph Book Company. You can buy Ancient India: Culture of Contradictions, here.

Upinder Singh is an Indian historian and the former head of the History Department at the University of Delhi. Currently, she is the dean of faculty and professor of history at Ashoka University. She has edited and written several books including Kings, Brāhmaṇas and temples in Orissa: an epigraphic study AD 300-1147, A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Rethinking Early Medieval India: A Reader, and With Dhar, Parul Pandya & Vatsyayan, Kapila – Asian Encounters: Exploring Connected Histories, Political Violence in Ancient India. Her area of specialisation is in ancient Indian history. In 2009, she was awarded the prestigious Infosys Prize for Social Sciences-Humanities. You can read more about her and her works, here.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

please edit the font size of The large quotes in the paragraphs.