Gandhi stands tall over the past, present and future of Indian, and often global, discourse. It doesn’t matter whether you agree or disagree with him or agree with him on some things and disagree with him over others; he remains a lodestone marking out North and South, leaving you to decide with direction you will take in its context. Besides his sweeping and substantial impact on history, this has been made possible because of the searing honesty with which he examined his own life, even as he was living it, while allowing others to do the same.

Of these others a figure that stands out is Mahadev Desai, Gandhi’s personal secretary, variously described as his Boswell, a Plato to his Socrates, an Ananda to his Buddha. But Desai was much more. An outstanding scholar, writer (in English, Gujarati and Bengali) and translator who received the Sahitya Akademi Award only posthumously, for a period he ran Motilal Nehru’s The Independent from Allahabad, printing it on a cyclostyle machine after the paper suffered a crackdown (with the caption ‘I change but I cannot die’) for which he was eventually jailed. Verrier Elwin describes Desai as “Home and Foreign Secretary combined”, “equally at home in the office, the guest-house and the kitchen”. The excerpts from Desai’s diaries, below, reveal how Desai was not just a personal secretary but also a political adviser to Gandhi. Rajmohan Gandhi says Desai lived Gandhi’s life thrice over: “first in an attempt to anticipate it, next in spending it alongside Gandhi, and finally in recording it into his diary”.

These diaries are an invaluable primary source, not just because of the lucid way in which they have been written, but also because they record events with a candid insight that speeches, articles and interviews — which are far more calculated — are often bereft of. Most importantly, they record events leading up to events: the behind-the-scenes turning-of-the-wheels in the minds of thinkers and leaders who, consequently, turn the wheels of history.

As is wont for those who stand tall over history, politics and society, Gandhi’s birth anniversary serves as an occasion for bouquets on the one hand and brickbats on the other. The brickbats are often lobbed from the standpoint of his controversial positions on caste (you can read a paper we have republished on the same here). One brickbat, in particular, has to do with his fast unto death to protest Ramsay MacDonald’s Communal Award, ordering separate electorates for ‘untouchables’, which led to the Poona Pact (which instead allocated reserved legislative seats instead) being signed by BR Ambedkar.

The following excerpts from Desai’s diary, however, have not been chosen to indicate any sort of argument for or against Gandhi’s historic fast. They have been chosen, instead, to offer a microscopic view into the minds of a thinker and leader, as well as those around him, when confronted with a difficult situation, and in the lead-up to a decision that would impact, and continues to impact millions (it has been argued that the decision to go with the Poona Pact over the Communal Award set in place a paradigm for the politics of representation that continues till this day). There is, after all, no better time to study a thinker-leader, than when he is in the middle of a conundrum.

The excerpts also offer a glimpse into the prison life of freedom fighters like Gandhi, Vallabhbhai Patel and Desai (Desai spent a considerable amount of time in prison with Gandhi, right up to his — i.e. Desai’s — last breath), but, more significantly, they comprise frank and open conversations. One must remember that these were private conversations taking place in 1932, but it’s interesting how Gandhi’s attitude drifts from the nonchalantly patronising — “Till I went to England, I did not know that he was a Harijan,” he says of Ambedkar. “I thought he was some Brahmin who took deep interest in Harijans and therefore talked intemperately.” — to one of humility: “Who are we to uplift Harijans? We can only atone for our sin against them or discharge the debt we owe to them… ”

Another interesting aspect of the conversations is the prevalence of debate, dissent and discussion among Gandhi’s prison circle (in these excerpts this comprises primarily Patel and Desai) though Gandhi eventually decides on going ahead with the fast, as well as the original draft of the letter he has penned for British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, regardless.

Finally, what makes such primary sources doubly valuable are the intuitive, if plain-spoken, asides that diaries such as Desai’s record, such as this one from Patel to Gandhi: “You can work in harmony with everybody. It does not cost you any effort. Vaniks (merchants) do not mind humbling themselves.”

I had not the faintest idea that such a day as this would dawn for me. But I did once dream in Nasik prison that I was all of a sudden taken to Bapu in Yeravda prison and that I fell at his feet, crying all the while and unable to check my tears.

Roche came to me in the morning and said, “You are being transferred from here; you get ready in one hour.” I asked him, “Where will they take me?” He replied, “You will be happy and thankful when you know it but I must not say a word.” I asked to meet Dr. Chandulal Desai but my request was turned down. We left Nasik at nine. The policemen who escorted me were the same as had a few days ago accompanied Vitthalbhai here. One of them turned out to be an old acquaintance of the days when Bapu saw Lord Reading. He remembered the date correctly — June 17, 1921. He was then a bearer to Sir Charles Innes. He had subsequently served elsewhere and was now in the police.

When Akbar Ali embraced me with tearful eyes and told me from his closed cell about his prayerful wish that I should be kept with Gandhiji, I said, “You may pray for me, but can I be so lucky as that?” He replied, “True, but I can only hope and pray.” What stories had I heard about Akbar Ali! But he showered his affection on me, and his prayers bore fruit. Pyarelal used to tell everybody at Nasik that they had fixed this up with Martin. This was also true though I regarded it as a mere joke.

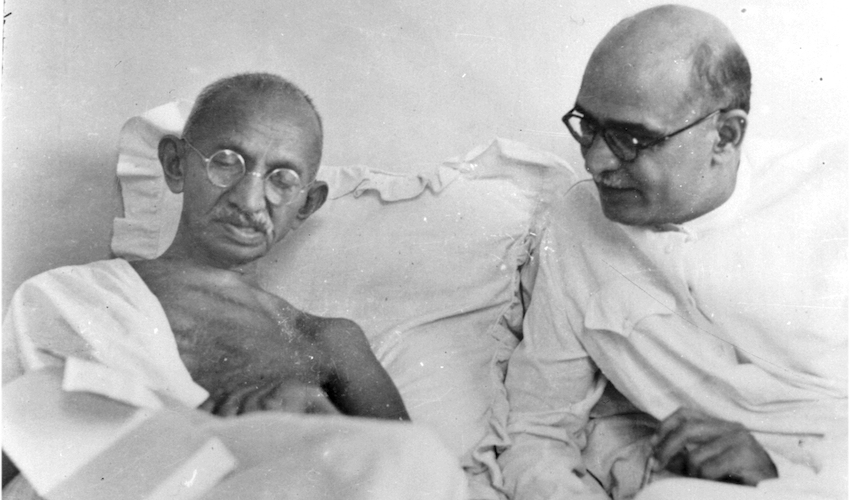

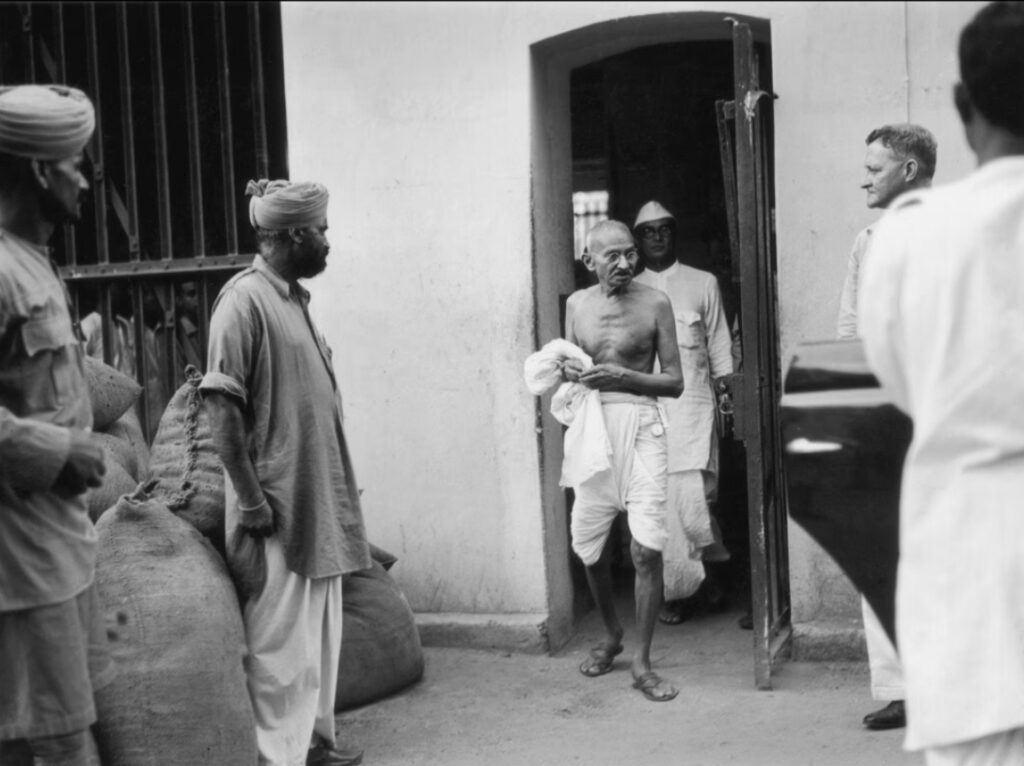

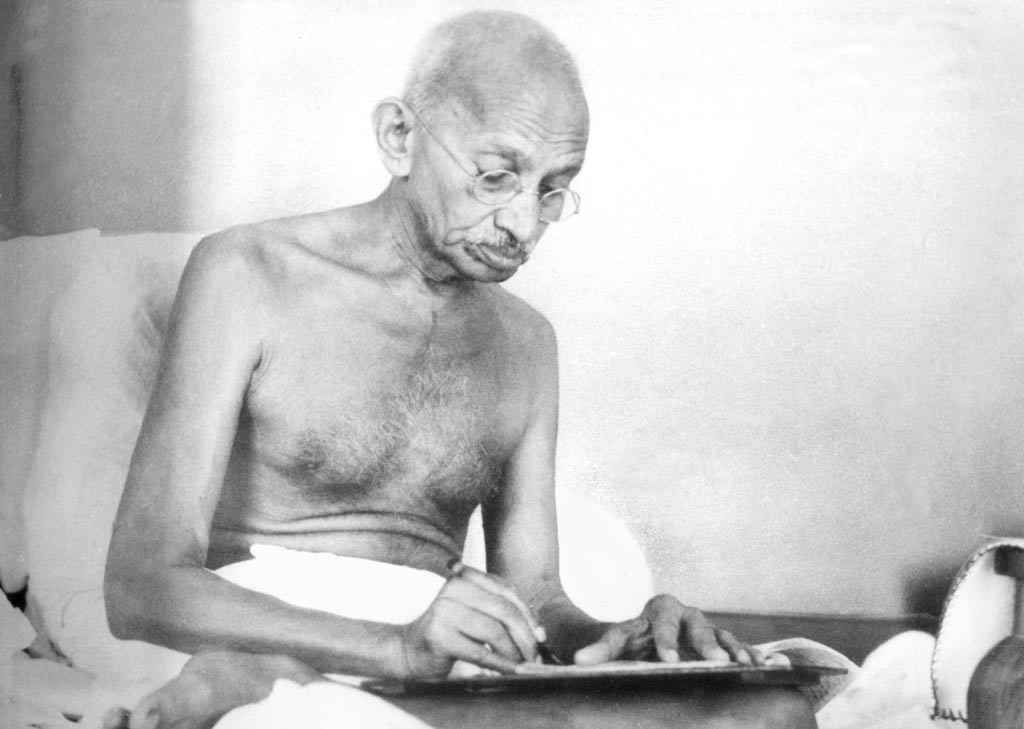

Gandhi in jail

I was received rather coldly at Yeravda prison and I feared they just wanted to get rid of me at Nasik, without keeping me in Bapu’s company here. Then came Kateli, smiling, and asked me to go with him. He was informed at four in the morning that I was to be kept with Gandhiji. Bapu too was surprised when I placed my head at his feet. He patted me on the back, the head and the cheeks more fondly than ever before. I felt deeply grateful but was overwhelmed by a sense of my unworthiness. Later I learnt from Bapu and the Sardar that Shri Purushottamdas also had a hand in bringing me to Yeravda. Last time Dahyabhai did say that — had done the needful.

Bapu too was surprised when I placed my head at his feet. He patted me on the back, the head and the cheeks more fondly than ever before. I felt deeply grateful but was overwhelmed by a sense of my unworthiness.

After some rambling talk, Bapu said, “You have come at the right moment, for Vallabhbhai is at his wit’s end. Did he tell you about it?” Vallabhbhai suggested that I should eat something before we started our discussions. He brought me food — bread, butter, curds and boiled sweet potatoes. He and Bapu had already finished their meals. When I finished, Bapu gave me his letter to Sir Samuel Hoare and asked me what I thought of it.

I said, “I find the reasoning sound. I have often felt about the repression that one need not be surprised if some day it leads Bapu thus to voice his indignation. Why does Vallabhbhai object? Is it because as President of Congress, he finds himself unable to endorse this step of yours?”

Bapu said, “No, he is not worried on that account. He doubts if he can give his consent as a co-worker. But I have never imagined Vallabhbhai looking at things from a religious viewpoint. It is only to be expected that he should look at this from the political angle. My relations with Vallabhbhai are not on a religious basis, as they are with you. Vallabhbhai is afraid that I shall lay myself open to misinterpretation. The Government will say: ‘Gandhi has always been a man of this type. He has gone mad; Let him alone with his madness.’ And Vallabhbhai also thinks the people will be shocked, and then again there is the grave danger of such fasts being imitated in the wrong spirit. But that does not matter. What if I am taken for a mad man and die? That would be the end of my mahatmaship, if it is false and undeserved. Friends like Remain Rolland will understand my standpoint. But even if they don’t, I should be concerned only with my duty as a man of religion.”

I said, “The world can understand fast as a protest against repression but not perhaps on the question of Harijan representation. The British will try to mislead the world into believing that most if not all Harijans favour separate electorates. I should also suggest you make it clearer how the separate electorates are intended to strike a blow at the body politic. I am pretty sure, however, that even honest Britons will fail to see how.”

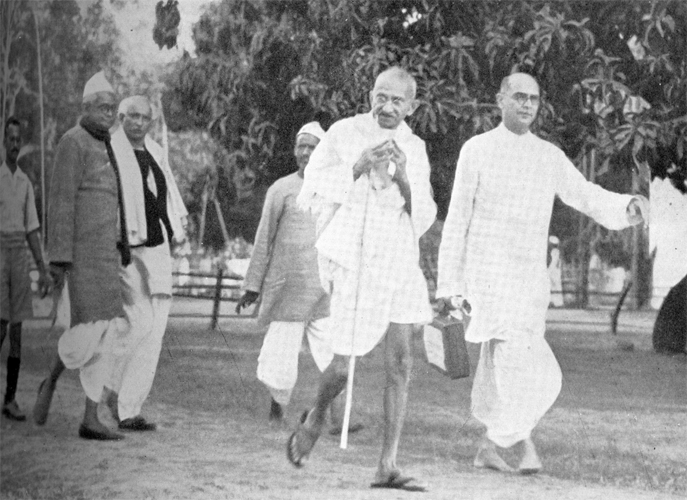

Gandhi with Mahadev Desai

Bapu said, “If we tried to make this clearer, we would have to describe the Muslims’ share in this sordid business. And that would increase Hindu-Muslim tension. This would be very much like what happened in connection with the earlier twenty-one days’ fast when Mahomed Ali got a few sentences in my statement scored out.”

I said, “Some will ask if this really was a sin more heinous than that committed by the Hindus so that you felt yourself compelled to undertake a fast.”

“Some will ask if this really was a sin more heinous than that committed by the Hindus so that you felt yourself compelled to undertake a fast.”

Bapu said, “We have been trying to make Hindu society repent of its sin. But the separate electorates are meant to perpetuate the sin or to make it impossible for the Hindus to repent. They will end in nothing but a civil war between the caste Hindus and Harijans, and between Hindus and Muslims.”

Vallabhbhai said, “I am unconvinced of the rightness of your move, but now you are free to do what you think is right.”

Bapu corrected the letter and went to bed. But I did not sleep till after midnight.

We got up at a quarter to four for the morning prayers. We had a wash and as we gathered together, Bapu gave the programme: “Vallabhbhai recites the shlokas (stanzas). He has little knowledge of Sanskrit and his pronunciation is bad. So I thought this was the only way it could be improved. You will find that he has made considerable progress. I sing the hymn, but not from memory. So we read one hymn after another from the Ashram hymnal. We thought we would start with the Marathi section today. But now that you are here, you will lead us in singing the hymn and in “Ramadhun”. I requested Bapu to lead us in Ramadhun. This discussion we had had at night. My first hymn was Prabhu mere etc., ‘O God, do not mind my heavy load of sin.’ What else could I have sung?

This morning we happened to talk about a certain Muslim leader. Vallabhbhai said, “He too took a narrow communal view in time of crisis and asked for a separate relief fund for Muslims and a separate appeal for it.” Bapu said, “He is not at fault on that score. What is he to do if we create such an environment for him? What amenities do we offer Muslims? They are mostly treated like untouchables. If I wished to send Amtul Salam to Devlali, could I ask — to put her up? The fact is that we should not go to the Bhatia sanatorium or for that matter any other place which excludes Amtul or any one else. Indeed it is up to the Hindus to take a step forward. As it is, the bitterness is increasing. It can be mitigated only if the Hindus wake up and break down the barriers they have erected. Perhaps the barriers were needed at a certain time, but now there is no earthly use for them.” Vallabhbhai said, “But the manners and customs of Muslims are different. They take meat while we are vegetarians. How are we to live with them in the same place?” Bapu replied, “No, sir. Hindus as a body are nowhere vegetarians except in Gujarat. Almost every Hindu takes meat in the Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Sindh. . . . All at present are on their trial. Let us wait and see, with faith that all will be well in the end.”

What is he to do if we create such an environment for him? What amenities do we offer Muslims? They are mostly treated like untouchables.

The Civil Surgeon examined Bapu, and placing the stethoscope on his chest said, “I would be proud to possess a heart like that.” So saying he passed on to other prisoners. Bapu did not tell him about the pain in his fingers. He examined my leg but had no treatment to suggest. It seemed as if he wanted to finish an unpleasant task somehow or other. No other Civil Surgeon went away like this without wanting to have a word with Bapu. This one is capable of amazing self-restraint.

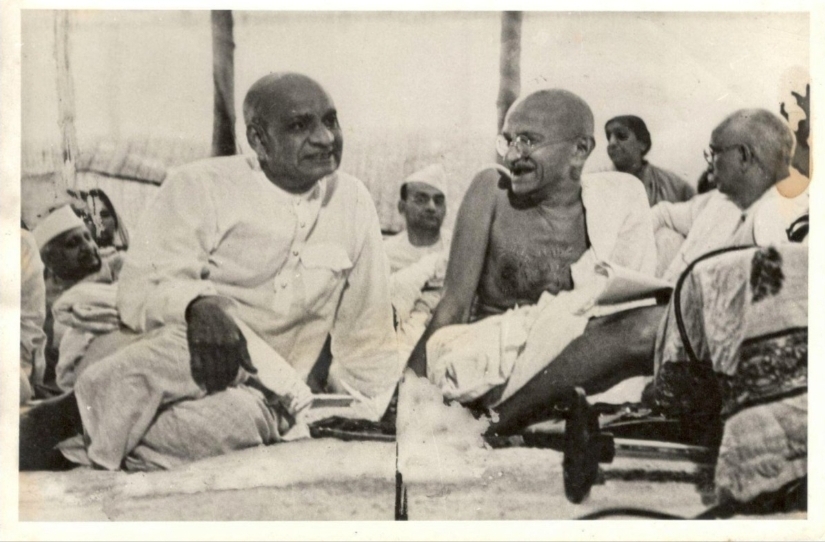

Gandhi and Patel

Sir John Anderson has come with testimonials from all. I showed to Bapu Laski’s remarks about him. Bapu said, “Perhaps that is true. If so he will capture Bengali hearts, win over Subhas Bose and Sengupta and disregard Congress. The same fate is perhaps in store for the Punjab. I do not think there will be peace in all parts of India at the same time. I imagine they will pacify one province after another.”

Bapu compelled me to sleep in the open from today and asked the Major for a cot for me.

The Major said, “Thirty or forty women prisoners all want to write to you. What shall I do about it? Would it not do if they just sent you their signatures ?” Bapu replied, “If you wish, I will ask them to be satisfied with writing only a couple of lines each. Why deprive them of this satisfaction? They are all so gentle.”

… We happened to talk about Ambedkar. Bapu said, “Till I went to England, I did not know that he was a Harijan. I thought he was some Brahman who took deep interest in Harijans and therefore talked intemperately.” Vallabhbhai said he knew he was a Harijan, as he had made his acquaintance when the Harijan leader toured Gujarat with Thakkar. Then we turned to Thakkar Bapa and the Servants of India Society’s attitude to Harijans.

“Till I went to England, I did not know that he was a Harijan. I thought he was some Brahman who took deep interest in Harijans and therefore talked intemperately.”

Bapu said, “Their attitude is responsible for the shape that question has assumed nowadays. I noticed this when I lived in the Poona home of the Society in 1915 after the death of Gokhale. I asked Devadhar for a brief note on their activities, so that I would see what I could do. This note advised that we should deliver speeches before Harijan meetings, and create in them a consciousness of the injustice done to them by Hindu society. I said to Devadhar, ‘Here you give me a stone when I asked you for bread. We cannot serve Harijans in this fashion. It is not service, but patronage pure and simple. Who are we to uplift Harijans? We can only atone for our sin against them or discharge the debt we owe to them, and this we can do only by adopting them as equal members of society, and not by haranguing them.’ At this Sastri was taken aback and said, ‘ We did not expect that you would speak in such a magisterial tone.’ And Hari Narayan Apte was very angry. I said to him, ‘I am afraid you will make Harijans rise in rebellion against society.’ Apte replied, ‘Yes, let there be a rebellion. That is just what I want.’ In this way there was a lot of discussion, so that the next day I said to Sastri, Devadhar, Apte and others that I had no idea I would cause them pain. This apology left a good impression on their minds. And afterwards we pulled on well together.” Vallabhbhai said, “You can work in harmony with everybody. It does not cost you any effort. Vaniks (merchants) do not mind humbling themselves.”

Who are we to uplift Harijans? We can only atone for our sin against them or discharge the debt we owe to them, and this we can do only by adopting them as equal members of society, and not by haranguing them.

The communal decision was published today. Bapu went about his work till the evening as if nothing had happened. He asked me to prepare a hajra cake and ate it with relish. Almond butter was made with the help of the machine. As we were taking the usual evening walk, he read Horniman’s article and liked it. In the course of conversation in the morning he said: ‘The decision only confirms the minorities’ pact. Everything has gone according to the plan in Benthall’s letter.’

I said the new constitution was worse than the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms. “Certainly,” replied Bapu. “Those reforms were based on the Lucknow agreement between Congress and the Muslim League. But this constitution seeks to create such divisions in the country that it can never again stand up on its own legs.” Just before the evening prayer he said to me, “Well, you and the Sardar think over the situation and tell me whatever you feel like saying. The letter to Samuel Hoare details the steps I should take in order to deal with the present situation. I have therefore to serve the British Government with a notice.” I was taken aback and said nothing. The Sardar also had a similar feeling. I sang Surdas’s hymn and began to read the Ashram post.

The letters which had to be written were written at once, and then Bapu began to write the letter to MacDonald.

After finishing it in the morning Bapu said, “You stop spinning for a while and go through this letter so that it may be sent at once.” The Sardar and I read it. Then he said, ‘There is no reference in the letter to other parts of the decision. May not this be misinterpreted to mean that they are approved by you?” “No,” replied Bapu. “My views are well-known. Still if you wish, I will insert one paragraph, although I would then have to enter into argument. In this letter I propose to leave out all argument, this having been included in the letter to Samuel Hoare.” I suggested that Bapu should only say his soul rebelled against the decision as a whole, but part of it was so vicious that he would lay down his life in the attempt to get it annulled. “No,” said Bapu. “No such comparison may fairly be instituted. If it were, they would say that I wanted to get the decision annulled in its entirety and had seized upon a certain part of it as a pretext. I do want the whole decision to go. But at night I thought for a moment over the question whether other points should be included and decided against their inclusion.”

Gandhi writing a letter

The same subject was discussed in the evening. Bapu observed, “I cannot put in other things at all, for that would be tantamount to mixing politics with religion. The two questions are in fact distinct from each other.” He then continued, “I have rehearsed everything in my own mind. Everything you have suggested was considered by me before I reached the decision. Separate electorates for the Muslims and the rest are fraught with danger. They will combine with the British to suppress the Hindus. But I can think of methods by which the combination can be dealt with. When once the outsider who foments quarrels is gone, we can tackle our problems with success. But as regards the so-called untouchables I have no other remedy. How possibly am I to explain things to these poor fellows? To draw suffering on oneself when misfortune dogs one’s footsteps is no novelty. How did Sudhanva fall into the pan full of hot oil and how did Prahlad embrace a pillar of red-hot iron? There will be many Satyagraha movements even after the attainment of Swaraj. I have often had the idea that after the establishment of Swaraj I should go to Calcutta and try to stop animal sacrifice offered in the name of religion. The goats at Kalighat are worse off even than untouchables. They cannot attack men with their horns. They can never throw up an Ambedkar from their midst. My blood boils when I think of such violence. Why do they not offer tigers instead of goats?”

“Separate electorates for the Muslims and the rest are fraught with danger. They will combine with the British to suppress the Hindus. But I can think of methods by which the combination can be dealt with. When once the outsider who foments quarrels is gone, we can tackle our problems with success. But as regards the so-called untouchables I have no other remedy.”

In the morning we discussed the possible repercussions of Bapu’s step. I said, “It will be misinterpreted in a variety of ways. Here in India there will be senseless imitation of it while in America they will say Gandhi obtained his release by his fast.” “I know,” replied Bapu. “In America they will swallow anything, and there are British agents ready to help them to do so. Many will even say that I am now a bankrupt, that my spirituality is not paying dividends; therefore, I committed suicide like cunning insolvents. And in this country there will be blind imitation, and misinterpretation. The Government will perhaps release me and let me die outside prison, or perhaps they will let me die in jail, as in the case of MacSwiney. Our own men will be critical. Jawaharlal will not like it at all. He will say we have had enough of such religion. But that does not matter. When I am going to wield a most powerful weapon in my spiritual armoury, misinterpretation and the like may never act as a check.”

Mahadev Haribhai Desai (1 January 1892 – 15 August 1942) was an Indian independence activist, scholar and writer best remembered as Mahatma Gandhi’s personal secretary. He has variously been described as “Gandhi’s Boswell, a Plato to Gandhi’s Socrates, as well as an Ananda to Gandhi’s Buddha”.

He is highly regarded as a translator and writer in Gujarati. He wrote several biographies such as Antyaj Sadhu Nand (1925), Sant Francis (1936), Vir Vallabhbhai (1928) and Be Khudai Khidmatgar (1936) which was a biography of Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan and his brother Khan Abdul Jabbar Khan. He was also a regular contributor to Gandhi’s publications Young India, Navjivan and the Harijanbandhu. He wrote several works in English including Gandhiji in Indian Villages (1927), With Gandhiji in Ceylon (1928), and The Story of Bardoli (1929).

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Great article.