ARCHIVE

An Indian in New York (1913-1916)

A young Ambedkar during his Columbia University days. Wikimedia Commons.

Young Ambedkar’s emerging academic understanding of caste was helping him give systematic expression to his many prior years of the lived experience of systemic caste prejudice. Alongside and as impetus to this were also his widening experiences regarding issues of race, class and gender. To some extent, this new exposure was a result of his coursework at Columbia. But much of this exposure came more concretely, from treading the streets of upper Manhattan and Harlem.

Describing his usual New York day, Ambedkar emphasized that the vast majority of his time, some 18 hours daily, was spent on campus, either attending lectures and seminars, or otherwise working in Columbia University’s magnificent and exceptionally-stocked Low Library. But he often ate off of campus, opting to eat only one meal per day to save both time and money. For food he spent on average $1.10 daily, which would buy him a cup of coffee, two muffins, and either a meat or a fish dish. He was on a tight budget. New York City living was not cheap, and he had to send money home to his family as well. But that was not all. His voracious reading habit, that had been cultivated in young Ambedkar within the shadow thrown by the Bombay-gothic tower of Elphinstone, had only grown stronger atop the grand staircase of the Roman-neoclassical library of Columbia. Ambedkar was now in the first stage of what would turn out to be a life-long obsession with collecting books. He spent all the leisure time that he had browsing Manhattan’s numerous second-hand book shops and sidewalk stalls, amassing a personal library of some 2000 volumes during his three-year stay.

The quest for books led young Ambedkar out of upper Manhattan down to 42nd street on Fifth Avenue, where the imposing beaux-arts styled New York Public Library had recently opened its doors, and opened them to all – including to black people and to women. So impressed was Ambedkar with the public library that upon learning of the death of Sir Pherozeshah Mehta in Bombay, and the Bombay municipality’s plan to prominently erect his statue, Ambedkar shot off a provocative letter from New York to the Bombay Chronicle, the English-language weekly that Mehta had himself launched in 1910. Ambedkar, fresh from another inspiring visit to the New York Public Library, argued in his letter that erecting a public library in Bombay instead of a ‘trivial and unbecoming’ statue would be a far better tribute to the memory of this great man:

It is unfortunate that we have not as yet realized the value of the library as an institution in the growth and advancement of a society. But this is not the place to dilate upon its virtues. That an enlightened public as that of Bombay should have suffered so long to be without an up-to-date public library is nothing short of disgrace and the earlier we make amends for it the better. There are some private libraries in Bombay operating independently by themselves. If these ill-managed concerns be mobilized into one building, built out of the Sir P.M. Mehta memorial fund and called after him, the city of Bombay shall have achieved both these purposes.

It is unfortunate that we have not as yet realized the value of the library as an institution in the growth and advancement of a society. But this is not the place to dilate upon its virtues. That an enlightened public as that of Bombay should have suffered so long to be without an up-to-date public library is nothing short of disgrace and the earlier we make amends for it the better. There are some private libraries in Bombay operating independently by themselves. If these ill-managed concerns be mobilized into one building, built out of the Sir P.M. Mehta memorial fund and called after him, the city of Bombay shall have achieved both these purposes.

The week following Pherozeshah Mehta’s death in Bombay, Booker T. Washington died in Tuskegee, Alabama. Washington, who had been born into slavery, was the most prominent Southern black activist of his day. As Principal of the Tuskegee Institute and author of a best-selling autobiography, Up From Slavery, Washington’s work and writings would have been well known to Ambedkar. Indeed, he would have heard his name prior to reaching America given that his patron, Maharaja Sayajirao Gaikwad, had long before taken to referring to the great social reformer Jotirao Phule, author of Gulamgiri (or, Slavery) as ‘India’s Booker T. Washington’.

The streets of upper Manhattan were beginning to buzz with a new black consciousness that expressed itself not only socio-politically – as for example with the writings and activism of W.E.B. DuBois and the National Negro Committee (which would soon become the NAACP) – but also aesthetically, with emerging literary, theatrical and musical innovations that would set the stage for the later Harlem Renaissance.

Besides his letter to the Bombay Chronicle, Ambedkar sent off numerous letters to family and friends in India during his stay in New York. The letters show that Ambedkar was as attuned to issues regarding gender as he was to those regarding race. One worth mentioning was addressed to a friend of his father, a retired Jamedar of the Indian army, also from the Mahar caste. In it, he implored the recipient – who was the father of a young girl gaining notoriety for having made it all the way to 4th standard in school, unheard of for a Mahar girl – to preach the idea of education to anyone from their community who was willing to listen to him. Ambedkar wrote that he should continue the education of his daughter, and that the entire community would progress more quickly if males and females were educated side-by-side, with no difference between them.

This letter, too, can be seen to reflect the environment Ambedkar now found himself in. For, alongside the emergence of a new black consciousness, New York City was also buzzing with the tireless activism of suffragists demanding the enfranchisement of women in America. And some of the most dynamic of these suffragists were young Ambedkar’s fellow Columbia classmates – and some, as luck would have it, turned out to be his favourite professors.

This letter, too, can be seen to reflect the environment Ambedkar now found himself in. For, alongside the emergence of a new black consciousness, New York City was also buzzing with the tireless activism of suffragists demanding the enfranchisement of women in America. And some of the most dynamic of these suffragists were young Ambedkar’s fellow Columbia classmates – and some, as luck would have it, turned out to be his favourite professors.

The summer just prior to Ambedkar’s arrival at Columbia, his soon-to-be classmate, Chinese-born Mabel Ping-Hua Lee was one of fifty horse-back suffragettes leading a procession of 10,000 people up Fifth Avenue to Carnegie Hall. Among those marching were Ambedkar’s future philosophy professor John Dewey and his future economics professor Vladimir Simkhovitch. In the spring of 1914, Lee published, in a campus paper, an article entitled ‘The Meaning of Woman Suffrage’, advocating for equality of educational opportunities and the economic liberation of women. In terms identical to those Ambedkar would himself utter frequently in his later speeches, Lee referred to ‘equality of opportunity’ as the essence of ‘democracy’. To her, feminism meant ‘nothing more than the extension of democracy or social justice and equality of opportunities to women’.

Lee, supervised by Simkhovitch, and Ambedkar, supervised by Seligman, were together enrolled in the course leading toward the PhD in economics at Columbia’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Later, Mabel Lee would become the first Chinese woman to earn a doctorate in economics in the United States, just as Ambedkar was one of the first Indians (and certainly the first Dalit) to do so.

Vladimir Simkhovitch, apart from being Lee’s doctoral supervisor, was one of the world’s leading experts in socialist economics and Marxist thought. Ambedkar enrolled in his Econ 114 (Marx and Post-Marxian Socialism), Econ 303 (Seminar on Political Economy), Econ 109 (History of Socialism), Econ 242 (Radicalism and Social Reform), and Econ 119 (Economic History) – that’s five full courses on Marxism and socialism! At least for some of these courses, if not out of wider interest, Ambedkar would have had to have purchased some of Marx’s original writings; books by Marx must have been among the 2000 volumes that he had acquired while in New York. As we will later learn, the vast majority of these 2000 books never made it back with Ambedkar to India. Several of them, such as the writings of John Dewey, Ambedkar subsequently repurchased elsewhere. But curiously, we can find none of Marx’s books among Ambedkar’s extant library. It seems that his later experience with Brahmanical Indian Marxists so soured Ambedkar’s view of Marx that he never even bothered to replace his lost books.

John Dewey (left) and Edwin Seligman (right). Ambedkar’s professors at Columbia University.

One book that Ambedkar purchased in New York that clearly made it with him to India, as apparent from his inscription, was Mrs Rhys Davids’ Buddhism: A Study of the Buddhist Norm (first published in New York in 1912). This book focused on the most ancient, Pali sources of the Buddhist tradition. Ambedkar inscribed the first page in his hand, ‘Columbia Varsity, New York’, and then later on the right-hand side adjacent to it, ‘Bombay, India’. The book and its inscription both show a continuity of his interest in Buddhism, initiated by Dada Keluskar years before.

Of course, Ambedkar’s main focus of study, and the degree toward which he was working, was economics. The study of ancient Buddhism proved useful toward the first iteration of his Master’s thesis, entitled ‘Ancient Indian Commerce’, which may have first been written up as an original research paper for submission as a component of the MA examination. About 75 pages of this manuscript are extant, first covering the trade and commercial relations of ancient India with ancient Egypt, west and east Asia, and then the Greeks and the Romans. Ambedkar strikes a proud, nationalist tone in the work, citing sources to emphasize the superior science, technology and splendours of ancient India over ancient Europe:

It is in the orient, especially in these countries of old civilization, that we must look for industry and riches, for technical ability and artistic productions, as well as for intelligence and science, even before Constantine made [the Roman empire] the centre of political power. Nay, all branches of learning were affected by the spirit of the orient, which was her superior in the extent and precision of its technical knowledge, as well as in the inventive genius and ability of its workman.

It is in the orient, especially in these countries of old civilization, that we must look for industry and riches, for technical ability and artistic productions, as well as for intelligence and science, even before Constantine made [the Roman empire] the centre of political power. Nay, all branches of learning were affected by the spirit of the orient, which was her superior in the extent and precision of its technical knowledge, as well as in the inventive genius and ability of its workman.

Remember that Ambedkar was by now thoroughly familiar with the political, economic, and intellectual history of classical Europe and Ancient Rome, so his claims regarding ancient India’s technical superiority were not merely rhetorical.

‘Ancient Indian Commerce’ then goes on to treat of India’s commercial relations in the Middle Ages, covering industry, trade and commerce throughout the rise of Islam and the expansion of western Europe. The next couple of chapters are missing, and the extant thesis ends with a chapter entitled ‘India on the Eve of the Crown Government’. In this chapter, too, Ambedkar exhibits a fierce nationalism, excoriating British imperialism and taking to task historians of British India who misrepresent the achievements of India prior to the arrival of the British: ‘Not only have they been loud in their denunciation of the Moghul and the Maratha rulers as despots and brigands, they cast slur on the morale of the entire population and their civilization’. What follows are 20 pages of argument and evidence, replete with tables, graphs and charts, of how India systematically contributed to the prosperity of Britain, while itself consistently degenerated, being beaten down and sucked dry.

This tour-de-force of Indian nationalist commercial and economic history then concludes with these damning words:

The supplanters of the Moghuls and the Marathas were persons with no better moral fiber, and the economic condition of India under the so-called native despots was better than what it was under the rule of those who boasted being of superior culture. It is with industries ruined, agriculture overstocked and overtaxed, with productivity too low to bear the high taxes, and with few avenues for display of native capacities, the people of India passed from the rule of the Company to the rule of the Crown.

The supplanters of the Moghuls and the Marathas were persons with no better moral fiber, and the economic condition of India under the so-called native despots was better than what it was under the rule of those who boasted being of superior culture. It is with industries ruined, agriculture overstocked and overtaxed, with productivity too low to bear the high taxes, and with few avenues for display of native capacities, that the people of India passed from the rule of the Company to the rule of the Crown.

American academia was far more accommodating of this magnitude of critique of British imperialism than either British or Indian universities were. Nevertheless, for reasons still unknown to us, Ambedkar abandoned the topic of ancient Indian commerce as his MA thesis, and instead drafted and submitted a much more technical, scope-limited, and positivist text entitled ‘Administration and Finance of the East India Company’. The most likely explanation is that Professor Edwin Seligman had been assigned as Ambedkar’s supervisor, and Seligman was a no-nonsense, technical economist, who viewed the subject of economics as a fact-based, impartial ‘science’. Seligman taught Ambedkar ‘the Science of Finance’, and was averse to the introduction of subjective viewpoints. As Seligman would write 10 years later in a Preface to Ambedkar’s published Ph.D., ‘The value of Mr. Ambedkar’s contribution to this discussion lies in the objective recitation of the facts and the impartial analysis…’.

The officially-submitted thesis, at only 45 pages in length, avoided speaking of history at all (the opening line reads: ‘Without going into the historical development of it…’), and was more restrained in claims regarding the systematic cultural destruction and impoverishment of India by the British. Nevertheless, in the end, Ambedkar exhibits the irrepressibility of his innate need to call out injustice, and closes the thesis with these reproaching words:

It remains, however, to estimate the contribution of England to India. Apparently the immenseness of India’s contribution to England is as astounding as the nothingness of England’s contribution to India….England has added nothing to the stock of gold and silver in India; on the contrary, she has depleted India—‘the sink of the world’.

It remains, however, to estimate the contribution of England to India. Apparently the immenseness of India’s contribution to England is as astounding as the nothingness of England’s contribution to India… England has added nothing to the stock of gold and silver in India; on the contrary, she has depleted India—‘the sink of the world’.

The thesis was accepted by Seligman and passed, and on 02 June 1915 Ambedkar was awarded the degree of Master of Arts in Economics. He had completed the requisite 30 credit hours for the M.A., but 60 credit hours were required for a doctorate. He thus continued in his coursework and in his research and writing, and from that point on, all the credits were counted toward the completion of his Ph.D.

Ambedkar continued working on the ‘science of finance’ as the subject of his doctoral dissertation under Seligman at Columbia. The tentative title for his Ph.D. thesis was ‘The National Dividend of India’, a historical and analytical study of Indian finance. But interestingly, following the award of his M.A. in economics, nearly every course that Ambedkar enrolled in as credit toward his Ph.D. in economics were non-econ courses. After the summer of 1915, Ambedkar took only one economics course (econ 183, on Railways); all of the rest were in languages (French and German), History (4 courses), Philosophy (4 courses), Politics (1 course), and Anthropology (4 courses).

All four of these Anthro courses were taught by Alexander Goldenweiser, himself a student of Franz Boas, the ‘father of American anthropology’. Boas also taught Anthropology at Columbia, in fact he co-taught a course with his friend John Dewey during the same semester that Ambedkar was attending Dewey’s philosophy course. In short, there is no doubt that young Ambedkar was exposed to the modern anthropological method of Boas. One of the primary features of Boas’ approach was his flat rejection of racial typologies which were so popular in late 19th-century anthropology. These racialist theories attributed fixed mental and physical characteristics to specific races. Boas (and indeed Dewey and Goldenweiser) rejected race as the dominant characteristic of a peoples and emphasized far more malleable and conditional characteristics such as culture, history and psychology instead.

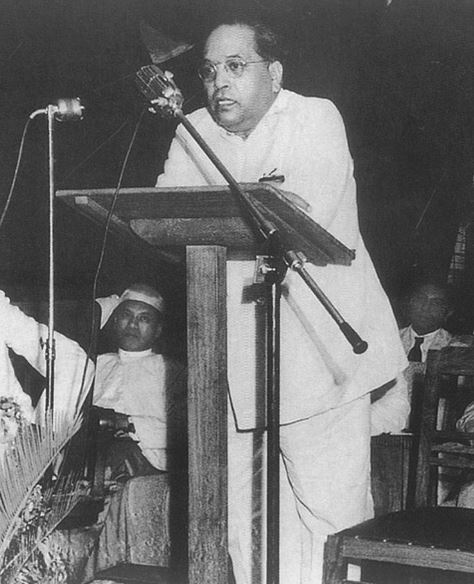

Dr. BR Ambedkar presiding over the joint Columbia Bicentennial – American Alumni Banquet at National Sports Club of India, New Delhi, October 30, 1954. Columbia University.

In May 1916, Ambedkar wrote an extensive and innovative research paper for one of Goldenweiser’s general ethnology courses, where the influence of Boas’ ideas against racial fixity is clear. In addition to opposing a basic Marxist tenet about class antagonism that Ambedkar learned from Simkhovitch’s courses, also discernable within the paper are many echoes of Ambedkar’s everyday experiences regarding race and gender from his wanderings away from campus. In the paper, entitled ‘Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development’, Ambedkar argued that caste was a distinct social category that could not be accounted for either by theories of race or by class antagonism. Rejecting the standard explanation of the racial origins of caste popular in colonial ethnography (i.e. a consequence of Aryan invasions wherein the darker-skinned earlier inhabitants were subjugated) and rejecting the dominant sociological claim that caste was maintained through a hierarchy of purity and pollution, Ambedkar boldly asserted that the essence of caste was the control of women’s sexuality – foremost, the practice of endogamy.

In the paper, entitled ‘Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development’, Ambedkar argued that caste was a distinct social category that could not be accounted for either by theories of race or by class antagonism. Rejecting the standard explanation of the racial origins of caste popular in colonial ethnography (i.e. a consequence of Aryan invasions wherein the darker-skinned earlier inhabitants were subjugated) and rejecting the dominant sociological claim that caste was maintained through a hierarchy of purity and pollution, Ambedkar boldly asserted that the essence of caste was the control of women’s sexuality – foremost, the practice of endogamy.

Ambedkar was exceptionally proud of the work. A year later, it became his first scholarly publication, appearing in the professional journal The Indian Antiquary. Later, when publishing his Ph.D. dissertation as a book, he is described on the title page as the ‘author of Castes in India’. Years later, in 1944, when he was publishing a third edition of his explosive essay Annihilation of Caste, he revealed that the third edition had been delayed for so long after the print run of the 1937 second edition was exhausted because he had been trying to find the time to recast Annihilation of Caste ‘so as to incorporate into it another essay of mine called Castes in India’. Indeed, even Ambedkar’s latest writings from the 1950s, when he was nearing the end of his life, referenced assertions that he had first posited as a young doctoral candidate at Columbia.

In many ways, Ambedkar’s ‘Caste’ paper captured everything other than ‘the science of finance’ that Ambedkar had learned and discovered, both on and off campus, during his three formative years in New York. The formal structure of this rich education was giving shape to his profound lived experiences being Dalit – all of those childhood experiences that he had written about in his autobiographical fragments, Waiting for a Visa – forging an uncommon and unprecedented concatenation of events that helped to make Ambedkar the extraordinary person that he was.

This excerpt has been reproduced with permission from Aakash Singh Rathore from the book Becoming Babasaheb: The Life and Times of Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar: Birth to Mahad (1891-1929) written by Aakash Singh Rathore. All rights reserved. Unauthorised copying is strictly prohibited. You can buy the book here.

ARCHIVE

Contesting Power – Contesting Memories: the Obelisk at Koregaon

The obelisk at Koregaon is characterised by a surprising commemorative history. A memorial to a bloody encounter within an imperial war, this monument provides a case study which illustrates that contestations of memories often bear the imprint of contestations for hegemony that are played out in the present.

The obelisk at Koregaon in Western India, built as a demonstration of empire builders’ belief in their own power and military prowess, serves a similar function today, but for a different group of people: the former Untouchables who had collaborated with the colonizers against what they perceived as a tyrannical indigenous regime.

The recently emerged tradition of an annual pilgrimage to the memorial, should be seen as an effort at creating and popularizing an alternative culture of the former Untouchables, now known as Neo-Buddhists. While Indian society grapples with the problem of accepting the equality of its various castes, one can witness different pathologies of memory surrounding the monument. Today, both amnesia and pseudomnesia are associated with the Koregaon memorial, defying the locus of a person in the discourse on social justice in present-day India. The memorial had faded into oblivion from British public memory long before the end of the imperial rule. However, it has undergone a metamorphosis of commemoration and now signifies something quite different from what was originally intended.

The Battle of Koregaon and its Memorial

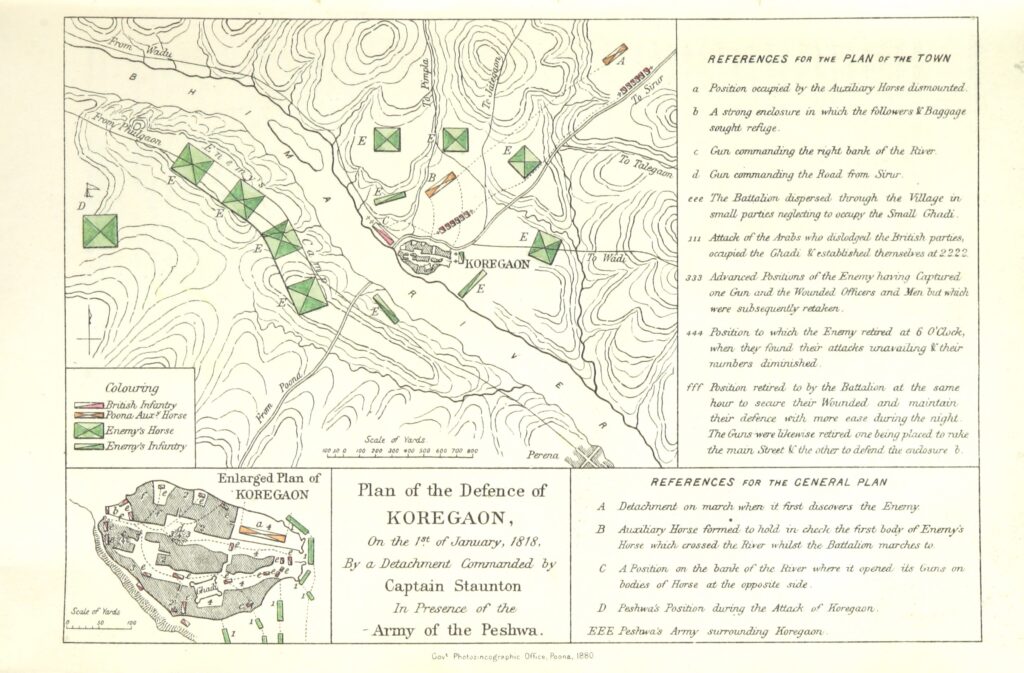

British defence plan during the Battle of Koregaon from Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency (Ed). Sir James M. Campbell, p. 259. Published in 1896. British Library.

The political ascendancy of the British East India Company in Eastern and Northern parts of India dates back to the battle of Plassey in 1757. From then on it gradually began extending its political hold to the other parts of India. During the same period, from their base in Pune in Western India, the Peshwa rulers (1707-1818) were also extending their political influence. Clashes between the Peshwas and the Company seemed inevitable. On 1 January 1818, a battalion of about 900 Company soldiers, led by F. F. Staunton from Seroor to Pune, suddenly faced a 20,000-strong army commanded by the Peshwa himself. The encounter took place at the village of Koregaon on the banks of the river Bheema. In the words of Grant Duff, a contemporary official and historian, “Captain Staunton was destitute of provisions, and this detachment, already fatigued from want of rest and a long night march, now, under a burning sun, without food or water, began a struggle as trying as ever was maintained by the British in India.” The battle was not decisively won by either side, but in spite of heavy casualties, Staunton’s outnumbered troops managed to recover their guns and carry the wounded officers and men back to Seroor.

As it was one of the last battles of the Anglo-Maratha wars, which ended with a complete victory of the Company, the encounter quickly came to be remembered as a triumph. The East India Company wasted no time in showering recognition on its soldiers.

While Staunton was promoted to the honorary post of aide de camp by the Governor General, the battle received special mention in Parliamentary debates next year. A memorial was commissioned and a year later, Lt Col Delamin, who was passing by the village, could already witness the construction of a 60-foot commemorative obelisk.

The Koregaon memorial still stands intact today. It is supposed to commemorate the British and Indian soldiers who ‘defended the village with so much success’ when the British East India Company confronted the Peshwa army in a ‘desperate engagement’. Marble plaques adorn the four sides of the obelisk. The two plaques in English are accompanied by translations into the local Marathi language. The Memorial Plaque declares that the obelisk is meant to commemorate the defence of Koregaon wherein Captain Staunton and his corps “accomplished one of the proudest triumphs of the British army in the East.” Soon after, the word ‘Corregaum’ and the obelisk were chosen to adorn the official insignia of the Regiment. In the Parliamentary debates in March 1819, the events were described as follows. “In the end, they not only secured an unmolested retreat, but they carried off their wounded!” In his volume published in 1844, Charles MacFarlane quotes from an official report to the Governor calling the engagement “one of the most brilliant affairs ever achieved by any army in which the European and Native soldiers displayed the most noble devotion and the most romantic bravery.” Twenty years later, Henry Morris confidently added: “Captain Staunton returned to Seroor, which he entered with colours flying and drums beating, after one of the most gallant actions ever fought by the English in India.” Later chroniclers of colonial rule continued to shower praise on the plucky Company force for displaying “the most noble devotion and most romantic bravery under the pressure of thirst and hunger almost beyond human endurance.” In 1885, even the ‘Grey River Argus’, a newspaper published in far-off New Zealand, described the battle in glowing terms. After the turn of the century, though, the colonial commemoration began to fade and gradually the event slipped from Britain’s public memory. The battle is now only mentioned in specialized literature on military history as an example not of British martial capabilities, but of that of the Sepoys.

Memories: ‘Ours’ and ‘Theirs’

Today the memorial finds itself just off a busy highway toll booth – a common site in the post-globalisation Indian landscape. Every New Year Day, the urban middle classes who need to use the highway, remind each other to avoid the particular stretch of the highway that passes by the memorial. Their reason for doing so is that “those people would be swarming their site at Koregaon.” Indeed, the memorial has become a site of pilgrimage attracting thousands of people who gather there every 1 January. If one asks the pilgrims what brings them together, there is a clear answer.

“We are here to remember that our Mahar forefathers fought bravely and brought down the unjust Peshwa rule. Dr Ambedkar has started this pilgrimage. He asked us to fight injustice. We have come to take inspiration from the brave soldiers and Dr Ambedkar’s memories.”

Initially, one might be baffled by this admiration for the native soldiers who fought on the British side and lost their lives in a fight against their own countrymen. A careful scrutiny of the list of casualties inscribed on the memorial reveals, however, that twenty-two names from amongst the native casualties listed end with the suffix “-nac”: Essnac, Rynac, Gunnac. The suffix ‘-nac’ was used exclusively by the untouchables of the Mahar caste who served as soldiers. This observation becomes particularly relevant when considered within the context of the caste profile of the Peshwas, who were orthodox and high-caste Brahmin rulers. The story of Koregaon is thus not just about a straightforward struggle between a colonial and a native power. There is another important but largely ignored dimension to it: caste.

Peshwa Bajirao II, who fought at the Battle of Koregaon. Coloured lithograph, Chitrashala Press, Poona, 1888. Wellcome Collection.

The Peshwas, Brahmin rulers of Western India, were infamous for their high caste orthodoxy and their persecution of the untouchables. Numerous sources document in great detail that under the Peshwa rulers, the ‘untouchable’ people who were born in certain so-called low castes were given harsher punishments than high-caste people for the same crimes. They were forbidden to move in public spaces in the mornings and evenings lest their long shadows defile high-caste people on the streets. Besides physical mobility, occupational and social mobility were also denied to these people who formed a major part of the population. Human sacrifices of ‘untouchable’ people were not uncommon under these eighteenth century rulers who had framed elaborate rules and mechanisms to ensure that the untouchables stayed just as their name suggests – untouchable. In 1855, Mukta Salave, a 15-year-old girl from the untouchable Mang caste who attended the first native school for girls in Pune, wrote an animated piece about the atrocities faced by her caste:

‘Let that religion, where only one person is privileged and the rest are deprived, perish from the earth and let it never enter our minds to be proud of such a religion. These people drove us, the poor mangs and mahars, away from our own lands, which they occupied to build large mansions. And that was not all. They regularly used to make the mangs and mahars drink oil mixed with red lead and then buried them in the foundations of their mansions, thus wiping out generation after generation of these poor people. Under Bajirao’s rule, if any mang or mahar happened to pass in front of the gymnasium, they cut off his head and used it to play “bat ball,” with their swords as bats and his head as a ball, on the grounds.’

Peshwa atrocities against the low-caste people have remained ingrained in public memory to this very day.

When the East India Company began recruiting soldiers for the Bombay Army, the untouchables seized the opportunity and enlisted. Military service was perceived as a means to opening the doors of economic as well as social emancipation. Political freedom and nationalism had little meaning for a population who had to choose between a life where the best meal on offer was a dead buffalo in the village and a life where their human dignity was respected – not to mention a decent monthly payment in cash.

While the untouchable soldiers fought on the British side against their own countrymen, the valour they showed is not at all perceived as a shameful memory today. In fact, Koregaon has become an iconic site for the former untouchables as it serves as a reminder of the bravery and strength shown by their ancestors – the very virtues that the caste system claimed they lacked. The memories related to the Koregaon memorial, help to explain how a memorial of colonial victory built in the early nineteenth century has been adapted to serve as a site that gives inspiration to the formerly untouchable people of India.

Mahars and the Military

Throughout much of the nineteenth century, the battle of Koregaon and the memorial were warmly remembered amongst military, imperial and political circles in Britain. At the beginning of the twentieth century, though, British rule was firmly established all over India, and the Koregaon Memorial faded from mainstream commemorative practices. Neither Britain at the height of colonial glory, nor India, which was beginning to receive small doses of independence, had time to commemorate the violent struggle of the days of the Honourable Company. Other lines of tradition were broken, too. The Mahar regiment had continued to demonstrate its bravery and loyalty in the battles of Kathiawad (1826) and Multan (1846). But then, in spite of the low castes’ long-standing military alliance with the British, some Sepoys from the Mahar Regiment, which formed a part of the Bombay Army, joined the “Indian Mutiny” in 1857. This added to a certain reluctance the British had always shown at the enlistment of Mahars. Subsequently, they were declared to be a non-martial race and their recruitment was stopped in May 1892.

Once their recruitment was discontinued, the Mahars soon began to feel the pinch. Gopal Baba Valangkar, a retired army-man founded a ‘Society for Removing the Problems of Non-Aryans.’ In 1894 the members of this society sent a petition to the Governor of Bombay to remind him that the Mahars had fought for the British to acquire their present dominion over India and requested a reconsideration of the decision to exclude Mahars from the Martial races, which deprived them of entry into the military service. The petition was rejected in 1896.

Another leader of the untouchables, Shivram Janba Kamble made an even more sustained effort to achieve the emancipation of the Untouchables. He had been involved in the work of the ‘Depressed Classes Mission’ which ran schools for untouchable children. In October 1910, R. A. Lamb of the Bombay Governor’s Executive Council was invited as the chief guest for a prize-giving ceremony in one of these schools. In his speech, Lamb mentioned his annual visits to the Koregaon Memorial. He drew attention to the ‘many names of Mahars who fell wounded or dead fighting bravely side by side with Europeans and with Indians who were not outcastes’ and regretted that ‘one avenue to honourable work had been closed to these people.’ It is not known whether it was Lamb’s speech that put the Koregaon Memorial back into the limelight or whether it had remained in living memory.

His words certainly lent weight to the argument that it was the Mahars who fought for the British and made them ‘masters of Poona.’

Within the first two decades of the twentieth century, Kamble organised a number of meetings of the Mahar people at the memorial site. In 1910, he arranged a grand Conference of the Deccan Mahars from 51 villages in Western India. The Conference sent an appeal to the Secretary of State demanding their ‘inalienable rights as British subjects from the British Government.’ They made a strong case for letting Mahars re-enter the army and argued that the Mahars were ‘not essentially inferior to any of our Indian fellow-subjects.’ Up until 1916 this request was repeated by various gatherings of untouchables in Western India. As the First World War gathered momentum, the Bombay government eventually issued orders in 1917 providing for the formation of two platoons of Mahars.

The Coming of Ambedkar

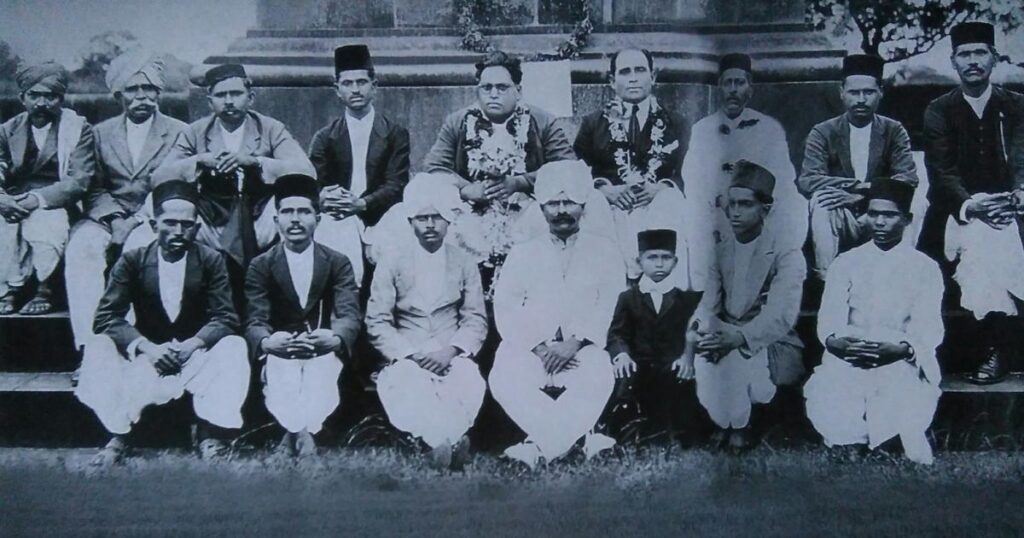

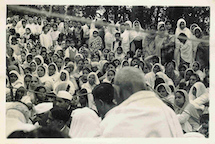

The happiness of the Mahars was, however, short-lived. Recruitment was stopped as soon as the war ended. This led to a renewed campaign for recognizing the valour of the Untouchables. By then, the demand had long since assumed the level of a movement for the general emancipation of the Untouchables. Within this campaign the Koregaon Memorial had become a focal point. Various meetings were held at the obelisk during which Kamble and other leaders invariably reminded the Untouchables of the valour and prowess exhibited by their forefathers. On the anniversary of the Koregaon battle on 1 January 1927, Kamble invited Dr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar to address the gathering of Untouchables. Ambedkar was not merely another leader of the untouchables. He was by now, as far as Indian politics was concerned, a force to be reckoned with.

Ambedkar was born in 1891, the son of a retired army subhedar from the Mahar caste. In spite of his first-hand experience of caste-based discrimination, he attained a doctorate from Columbia University, a D. Sc. from London School of Economics and was called to the Bar at Gray’s Inn by the age of 32. In 1926, he became a member of the Bombay Legislative Assembly.

He could not fail to appreciate the significance of the memorial for advancing the cause of the emancipation of the Untouchables. Not only did he make an inspiring speech at the gathering, he also supported the idea of reviving the memory of the valour of the forefathers by an annual pilgrimage to the site on the anniversary of the battle.

As a representative of the Untouchables, he was invited by the British to the Round Table Conference in 1931 where the future of the Indian Nation was to be decided. Based on his arguments at the conference, he wrote a small treatise called The Untouchables and the Pax Britannica in which he referred to the Koregaon battle to support his argument that the Untouchables had been instrumental in the establishment and consolidation of British power in India.

BR Ambedkar and his followers at the Koregaon victory pillar on 28 December 1927. Wikimedia Commons.

Indian mainstream politics from the 1920s until 1947 is recognised as the Gandhian era. Gandhi, having been born in the middle order caste of traders, had a different outlook on the systemic exploitation of the Untouchables on the basis of caste. He called the Untouchables Harijans, meaning people of God. Ambedkar and his followers resented both this name and the patronising attitude behind it. Underlying this surface issue, there were major ideological differences between Ambedkar and Gandhi. For the India represented by Gandhi and the Indian National Congress, the primary contradiction was that between colonial supremacy and Indians’ aspirations for political freedom. For Ambedkar and the Untouchable masses he represented, the oppression was not primarily located in the political system but arose from the socio-economic sphere. There was a clash of interests. The Indian National Congress under Gandhi sought to represent all Indians in a unified front against the colonial rule. Although Ambedkar was, unlike some “sections of Dalits and non-Brahmans who believed that colonial rule had been an unambiguous liberating force”, by no means a staunch supporter of British rule, he had quite a different new India in mind. While Gandhi saw the ideal social order arising from a reformed Hinduism, Ambedkar sought “political representation independent of the Hindu community.” In 1930, Gandhi embarked upon the Civil Disobedience Movement against the systems and institutions of the colonial rule. Kamble and a few other representatives of the depressed classes retaliated by launching what they called the “Indian National Anti-Revolutionary Party”. Its manifesto was quoted in The Bombay Chronicle:

In view of the fact that Mr Gandhi, Dictator of the Indian National Congress has declared a civil disobedience movement before doing his utmost to secure temple entry for the “depressed” classes and the complete removal of “untouchability”, it has been decided to organise the Indian National Anti-Revolutionary Party in order to persuade Gandhiji and his followers to postpone their civil disobedience agitation and to join whole-heartedly the Anti-Untouchability movement as it is… the root cause of India’s downfall…. The Party will regard British rule as absolutely necessary until the complete removal of untouchability…

Though this party did not attract much support in mainstream politics, it demonstrates that for the Untouchables, social and economic well-being was of greater and more immediate concern than political freedom, and hence colonial rule was regarded as a possibly necessary evil for the time being. It also shows that there were other and often contradictory voices in the independence movement of India. These have often been glossed over in nationalist rhetoric.

A New Memory

India won her independence in 1947, and Ambedkar chaired the committee tasked with the drafting of the new constitution. The ‘annihilation of caste’, however, remained a distant dream. The Hindu Code Bill proposed by Ambedkar in order to bring about extensive reforms in the Hindu socio-cultural scene was not accepted by parliament. In 1951 a disillusioned Ambedkar resigned from the Cabinet. Five years later, under his leadership, millions of Untouchables converted en masse to Buddhism in a step towards attaining total freedom from exploitation. The same year, after Ambedkar’s death, a political party, called the Republican Party of India, was formed to represent the interests of the low-caste people.

The conversion opened the floodgates for cultural conflicts with the high castes. The immediate reaction of the Hindu right was one of denial. The strategy of cultural appropriation that has worked so well for Hinduism from the times of the Buddha is employed even today to project the Buddhists as just another sect within Hinduism.

For the neo-Buddhists, this necessitated the creation of new and different cultural practices. Amongst the neo-Buddhists in western India one of the invented cultural practices that emerged as a result is the pilgrimage to the Koregaon Memorial. Thousands of neo-Buddhists throng to the memorial every New Year’s Day to commemorate the valour of the Mahars who helped to overthrow the high caste rule of the Peshwa. They also commemorate the visit of their leader, Dr. Ambedkar, on 1st January 1927.

Unlike any Hindu pilgrimage site, the Koregaon memorial is devoid of the tell-tale signs of a holy marketplace. No sellers of garlands and sweets and images of Gods are to be found here. It is a deserted place all through the year. However, come New Year, the place is dotted with little stalls selling books, cassettes and compact disks. Various publishers of Ambedkarite literature set up their stalls of books. Neo-Buddhist songs are played loudly in the stalls extolling the greatness of Ambedkar and emphasizing the need to change the world. Leaders of the now numerous factions of the Republican Party of India address their followers. Neo-Buddhist families visit the memorial obelisk. They offer flowers or light candles. An important part of the ritual is to offer a Vandana, a recital of verses from Buddhist texts.

An equally important element of their ritualised behaviour is the buying of books. Interviews with various booksellers have shown a surprising fact: whenever there is a gathering or a pilgrimage of the neo-Buddhists, the bookstalls do roaring business. It may be interesting to note that the average length of books sold at these stalls is short – volumes of 30-70 pages priced between 10 to 50 rupees. It might be an indication of the fact that the readers may be neo-literate, have very little time to spend on reading and can only afford cheaper books. Many publishers of related literature have indicated that their daily sales figures at the Koregaon pilgrimage and other such important pilgrimages (eg. Mumbai and Nagpur) often exceed their sales figures for the rest of the year. It could be perceived as an indication of the belief in emancipatory potential of education among the neo-Buddhists, especially of the former Mahar caste. Some of the best-selling titles include Marathi translations of books authored by Ambedkar himself, eg. Buddha and His Dhamma, Annihilation of Caste, Who Were the Shudras? Other popular books include Dalit autobiographies. They also sell Dalit poetry and small biographies of Dalit leaders.

These books offer a Dalit perspective on Indian history wherein colonial rule is portrayed as instrumental for emancipation, even though it remained ignorant of realities of caste exploitation. Jotirao Phule and Ambedkar are among the prominent Dalit writers who propounded this view of the colonial rule in which Gandhi and the movement for India’s independence do not figure very positively. The fact that Ambedkar chaired the Committee that created the Indian Constitution in 1950, however, is considered supremely important. Any attempt to criticise or seek a change in the Indian Constitution, therefore, provokes fierce opposition from the Dalit population. The anti-corruption movement led by Anna Hazare and his team in 2011 is a recent example. The extra-constitutional structure to create a powerful ombudsman (Lokpal) for resolving the issues of corruption was not welcomed by Dalit leaders and public.

The Importance of Forgetting

Though the Koregaon Memorial was constructed by the Colonial rulers, it does not feature on the commemorative landscape of today’s British public. This amnesia might be attributed to the fact that the colonial memories, especially of violent battles are no longer the object of pride in present-day Britain. This amnesia is matched by the high castes in India. Poona, the capital of Peshwas has become a software and education city called Pune. When a sample of 130 members of the high caste, newly rich people (who have come to be nicknamed as Computer Coolies) were asked about the Koregaon memorial, none of them knew what it was.

Elite amnesia is not total, though. There are also, what may be called conflicting memories. During the 1970s the Western Indian state of Maharashtra witnessed a spate of popular (a)historical novels topping the best-seller lists in Marathi. Many of them dominate the historical understanding and perceptions of the Marathi-speaking middle classes even today. Two important novels from this genre, both authored by Brahmins, describe the battle of Koregaon in passing. Mantravegla by N. S. Inamdar is based on the life of the Last Peshwa. It claims that the battle was, in fact, won by the Peshwas. Recently, this trend of creating alternative memories about the Peshwa battles has become even stronger. The battle of Panipat, which saw a complete defeat of the Peshwa armies in 1761, is commemorated today by high-sounding rallies. The kind of rhetoric used during these rallies suggests that it was the Peshwa who won the battle.

The Koregaon Memorial occupies a very significant place in today’s neo-Buddhist culture. The internet and other electronic media are used to document and commemorate the Koregaon battle and Ambedkar’s visit to it. An image search for Koregaon Pillar yields hundreds of digital pictures of the Memorial Obelisk. Film clips are available on Youtube. At least a dozen blogs in English and Marathi have entries related to the Koregaon memorial. They describe the battle and the role of the Mahar soldiers and also remind the readers about what the Untouchables could achieve if they show the resolve.

Conclusion

The obelisk of Koregaon Bheema is thus a site which has generated conflicting memories. These memories represent the divergent interests of the groups involved in their creation. Those wishing to commemorate the greatness of the Peshwa rule – the symbol of high caste supremacy – either choose to ignore the Koregaon battle, or create a Pseudomnesia of Peshwa victory. While the obelisk marks an imperial site of memory that is largely forgotten in the homeland of the empire, the monument has undergone a metamorphosis of commemoration in Western India.

It no longer reminds the public of imperial power, but for the former Untouchables whose forefathers fought at Koregaon it serves the purpose of providing “historical evidence” of the ability of the Untouchables to overthrow the high caste oppression.

Considering the fact that Indian society is still dominated by the system of caste hierarchy, the Koregaon Memorial is also a reminder that present-day contestation for hegemony is often manifested in contesting memories.

This paper has been carried out courtesy with the permission of Shraddha Kumbhojkar. It has been presented without its abstract, citations, footnotes and bibliography for purposes of easier reading.

The paper has also been published in Sites of Imperial Memory, (ed.) Dominik Geppert, Frank Lorenz Muller, Manchester University Press, Manchester, New York, 2015. as Politics, Caste and the remembrance of the Raj: the Obelisk at Koregaon. You can buy the book here.

ARCHIVE

PREFACE

Andal’s life and legend is so completely founded in the divine that merely thinking of translating Andal ought to make one speechless, struck with ineffability. Additionally, the genre of ancient Tamil poetry to which the Thiruppavai and the Naciyar Thirumoli belong is said to incorporate inner spaces, hidden meanings. How, then, might a translator go about the task of translating Andal, if one dares at all? Priya Sarukkai Chabbria and Ravi Shankar seem to derive their translation strategy from this openfield in Andal’s poetics.

There are two Andals in this book: Priya’s Andal, and Ravi’s Andal. The two translators do not divide Andal, they share her entirely, translating the same poems. Reading their translations one after another may alarm a reader who has dogmatic expectations of translations, or fixed ideas about fidelity; she may stop and wonder, which is the ‘real’ translation, which particular, ‘true’? Are Andal’s breasts in Pasuram 8 the ‘full hills’ of Priya’s translation or supple ‘upturned blossoms’ of Ravi’s?

Recognising the distinct styles and divergent translations of Priya and Ravi calls to mind the story of the Septuagint, where seventy-two translators come up with an identical translation of the Hebrew Bible. While this example is usually cited to establish the authenticity and the fidelity of that translation, it has always raised for me another question, the reality of the process. Can the translator be said to exist, if she is transparent? Even Anne Carson, whose exacting translation of Sappho places us as if right next to a poem fragment on an ancient papyrus, admits: “I like to think that, the more I stand out of the way, the more Sappho shows through. This is an amiable fantasy (transparency of self) within which most translators labor.” Every translator has a unique lens. This is not just about interpretation, an intellectual activity, this is also about personality, personal history, biography. An Urdu couplet explains it well: Ishq ki chot toh padti hi har dil pe iksaan. Zarf ke farq se avaaz badal jati hai. ‘The strike or the hurt of love falls the same way on each heart/mind, but depending on the material (i.e., nature, character, what stuff the person is made of) it sounds different.’ We must expect translations to be individual, otherwise the task of the translator may as well be the ‘task of the computer,’ or even the ‘task of the dictionary.’

Andal’s life and legend is so completely founded in the divine that merely thinking of translating Andal ought to make one speechless, struck with ineffability. Additionally, the genre of ancient Tamil poetry to which the Thiruppavai and the Naciyar Thirumoli belong is said to incorporate inner spaces, hidden meanings.

Priya uses imperatives (‘come, make this vow’), nouns as verbs (‘to hymn his magic’), and graphic images (‘lightning nerved air’) for a translation charged with momentum and force. Her triptych in Nachiyar is an enactment (abhinaya) much like in a dance-drama, where a statement is presented once, and then again, and then again, slightly different each time, the rasa more heightened. Assuming the first part is most literal, or as literal as you can get with Andal, and the second stanza yet another translation or telling, carrying an echo or trace of the first, the third stanza is a mutter, a trailing off, an entry into the psyche of Andal and the translator so impacted that she continues to voice her, not quite consciously. Ravi’s translation startles expectations that we may have of men-translators translating a woman-poet. In Take Me to the Land of My Lord, Andal asks, ‘[l]eave me there on my haunches,’ the limbs of Hrisikesa (Krishna) ‘quivering in time like a veena string’ – his translation embodies Andal. Ravi also circumambulates the ideas and images of a poem with each stanza, but works his imaginary into a smooth, narrative flow. Both translators bring us the textures of Tamil; whereas Ravi intersperses Tamil words in his translation, Priya’s English itself seems shaped by the source language. Their two Andals walk alongside. If Priya’s Thiruppavai is solemn, chant-like, Ravi’s Thiruppavai is conversational. Priya tells us that the gopis’ hands are too small to enclose the udders of the cows. Ravi tells us the udders groan to fill the pots. Two sets of eyes trained on the scene, the vision of the reader gains depth; and returning to the same poems from two different angles that are also rich spectrums in themselves drives the reader into the deep, of Andal. While Priya and Ravi respond to Andal, they also seem to respond to each other. What Ravi presents in Dark Flower expands into a bouquet in Priya, or perhaps Priya first shows us the flowers, and then Ravi the bunch? The collaborative strategy has an expansive effect, it is Andal who proliferates.

In order to appreciate, understand, or just locate the methodology of this Andal translation, it is useful to consider the conventions of how a ‘text’ or a source thrives in the Indian tradition. When we find railway metaphors in a song attributed to circa 15th century Kabir, we know that the corpus of Kabir represents an imaginary, Kabir songs pay homage to the collective idea of Kabir. And we do not split hairs over the definition of the Tulsidas Ramayana, wonder whether it is a translation, version, adaptation, creative translation, transcreation, retelling or commentary. It is multiplicity that achieves the transmission and continuity of source texts, whether oral, or written. Texts that we think of as ‘fixed’ also assimilate the voices of readers. Look at the tradition of Gita dissemination—it has relied, and continues to rely, on people who study, recite, translate, explain and comment on the Gita while drawing from previous commentaries (bhasyas). It is only in the context of modern book-culture that we expect a Gita translation to be the ‘representation’ of a source text, and expect commentary within footnotes and with reduced emphasis. And if we do not regard many Gita translations as many Gitas, that is a comment on our expectations of translations, and on our naiveté about interpretation, not on a translation’s management of fidelity.

In order to appreciate, understand, or just locate the methodology of this Andal translation, it is useful to consider the conventions of how a ‘text’ or a source thrives in the Indian tradition. When we find railway metaphors in a song attributed to circa 15th century Kabir, we know that the corpus of Kabir represents an imaginary, Kabir songs pay homage to the collective idea of Kabir.

Then the bhakti tradition admits intuition as methodology. In The Flute Calls Still, Dilip Kumar Roy writes about Indira Devi who became his disciple in 1949 in Pondicherry. Indira was such an intense seeker and bhakta, devotional singing sessions sent her into trances. She had visions of Mirabai singing in “a voice throbbing with “love’s yearning and pain,” recalled and wrote down these songs, and sang them. Commenting on this phenomenon, Sri Aurobindo (who was Roy’s guru) said, it was evident that “her consciousness and the consciousness of Mira are collaborating on some plane superconscient to the ordinary human mind.”

This book is a translation that must also be located within this Indic tradition, deriving its freedoms from it. It is a conversation with a mystic text, and must be appraised as one. Priya and Ravi utilize a range of methodologies from past and contemporary rubrics of translation, they are Indian and not only Indian, they are translators and poets besides, they work from Andal’s text and over and above, they translate, and they do more. Dear reader, may you be open to Andal in all sorts of ways.

– Mani Rao

INTRODUCTION

Andal and her Poetry

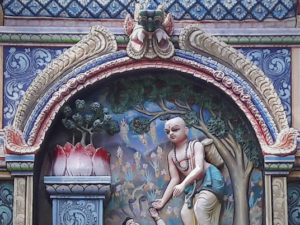

Andal (often referred to as Andal/Aandaal or Antal), the 9th-century mystic poet was elevated to goddess status within a few centuries of her birth in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. She was the only woman among the twelve medieval Vaishnava saints, known as the Alvars who ‘dived deep and drowned themselves in the love of god’ implying their complete devotion to Vishnu-Narayana, one of three main deities in the Hindu pantheon, often called Tirumal, The Sacred Dark One, in Tamil. Unlike other mystics Andal is unique in demanding to be taken as bride by Vishnu not as spirit but as a living maiden. Legend goes that when she was around sixteen she merged with her god at his temple in Srirangam, Tamil Nadu. Since then she has existed as myth and deity.

The Alvars, along with their counterparts, the Siva-worshipping Nayanmars, are the earliest proponents of the bhakti movement, a devotional and socially radical form of worship that emerged in medieval India which emphasized the quality of god as saulabhyam, or easily accessible to all. This celebration of personal prayer stressed composing in the poets’ mother tongue –as against Brahminic Sanskrit – some see it as striking against the caste system. Even as kings ‘re-converted’ to Hindu faith, the bhakti movement became a popular force instrumental in the retreat of wealthy Buddhist and Jain sects and, simultaneously, curtailed Brahmin monopoly on religion.

Andal’s first work – composed when she was about thirteen – the Tiruppavai (The Path to Krishna) is a lyrical description of the vows undertaken by young women to obtain a good husband; it is a song of congregational worship. In her second and last work, Nacciyar Tirumoli (The Sacred Songs of The Lady), Andal sings of her individual need for spiritual and sexual congress with her chosen god and of an abundant female desire explicitly sited in the body which too is holy. The Tiruppavai and the Nacciyar Tirumoli are included in the circa 11th century compilation Nalayira Divya Prabandham (Four Thousand Divine Compositions) that Tamil Srivaishanvas consider on par with the Sanskrit Vedas. The compilation’s literal translation is ‘Four’ (nali) ‘Thousand’ (aayiram) ‘Divine’ (divya) ‘affection’ (pra) ‘bonding’ (bandham) again is indicative of the Alwars’ intimacy of address to Vishnu-Narayana.

Andal calls to Vishnu, The Pervader, the cohesive principle of sattva, supreme illumination. The Brhad-devata (2.69.[213]) suggests his name may originate in the Sanskrit root vis which means to spread, to enter and to surround. “Having created the universe, he entered it” states the Taittiriya Upanishad (1.2.6. [274]). In Vaishnava theology, Vishnu is the Self in all of life and manifests endlessly in the world of forms and orders of creation, “just as from an inexhaustible lake thousands of streams flow on all sides” to guide and protect creation. Vishnu is prayed to as Hari, Remover of Sorrow and Illusions which is especially poignant in Andal’s case as she beseeches him time and again to accept and to save her. She addresses him variously: as Narayana (who moves on causal waters on the serpent Seshnaga), as Narayana Nampi (Universal Abode), Tirumal or Mal (The Dark One of Tamil theology) and through seven of his ten prominent avatars. But most often she addresses him as Krishna, divine child and lover.

Andal (often referred to as Andal/Aandaal or Antal), the 9th-century mystic poet was elevated to goddess status within a few centuries of her birth in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. She was the only woman among the twelve medieval Vaishnava saints, known as the Alvars who ‘dived deep and drowned themselves in the love of god’ implying their complete devotion to Vishnu-Narayana, one of three main deities in the Hindu pantheon, often called Tirumal, The Sacred Dark One, in Tamil.

Each of Andal’s pasurams (songs) is drenched in the way the sacred is embedded in every material that constitutes ephemeral life; at the same time she summons timeless grace, arul, to illumine her. Her work calls to question all markers of identity and boundaries as she passionately sings for bliss to enter her body and spirit. When we receive Andal, we must keep her youthfulness in mind. She conflates extreme violence with swooning surrender; splices the desires of the sexual body with visions of cosmic temporality. Yet we refrain from applying the term ‘transgressive’ to Andal as it suggests a deliberate breaking of rules. It appears she did not bother with any social conventions or rules at all – except those of poetry.

From Saint-Poet to Goddess and Teen Icon

Andal’s first work – composed when she was about thirteen – the Tiruppavai (The Path to Krishna) is a lyrical description of the vows undertaken by young women to obtain a good husband; it is a song of congregational worship. In her second and last work, Nacciyar Tirumoli (The Sacred Songs of The Lady), Andal sings of her individual need for spiritual and sexual congress with her chosen god and of an abundant female desire explicitly sited in the body which too is holy. Andal eventually would become a teenage saint-poet and then a goddess, when she became Vishnu’s consort, famously rejecting any marriage to a mortal man, considering herself betrothed to the divine.

Performative interpretations of Andal’s life of an all-surrendering love and passionate piety are enacted in Chennai during the annual music and dance festival as ‘high’ art, as also in films and popular TV dramas. Dingy roadside photo studios exhibit saturated images of girls in their coming-of-age ceremony dressed as Andal in vibrant silk saris, flower garlanded, hair dressed in a small bun on the right and then left to cascade. (The girls are also photographed variably as faux geishas, in salvar-kameez ‘suits’, as Bollywood starlets in jeans and spangling tops etc, thereby co-opting every current image of desirability. The Andal iconographic image, however, is a constant.) Perhaps the photographs imply that each girl is a fit bride for a god or perhaps they are shaded with upper caste aspirations, but it seems possible that there is a more powerful and unfathomed cultural imagination at work 13 centuries after Andal’s brief life.

Andal’s first work – composed when she was about thirteen – the Tiruppavai (The Path to Krishna) is a lyrical description of the vows undertaken by young women to obtain a good husband; it is a song of congregational worship. In her second and last work, Nacciyar Tirumoli (The Sacred Songs of The Lady), Andal sings of her individual need for spiritual and sexual congress with her chosen god and of an abundant female desire explicitly sited in the body which too is holy.

Andal’s first work, Tiruppavai (The Path to Krishna) is famed in Southern India, especially Tamil Nadu and sung by devotees during the sacred month of Markali. It is a lyrical and bhakti-filled description of vows undertaken by young women to obtain a good husband and is a song of congregational worship. However, in the later Nacciyar Tirumoli (The Sacred Songs of the Lady), Andal sings of her individual need for sexual congress with her chosen god. Except for Hymn Six – which elucidates her dreams of the marriage rituals and is sung at weddings even today – the other 13 hymns are not as often heard, perhaps because they speak of an abundant female desire explicitly sited in the body. Similar to the Gnostic texts which were omitted from what is commonly referred to as the Judeo-Christian Bible for their more overt sexual symbolism and heterodoxy which verged on the heretical, many of Andal’s hymns from the Nacciyar Tirumoli are considered by many (though not by us) to be ‘transgressive’.

Prismatic Soundings

We, the two translators of this project, are poets ourselves and so approach the translation with neither a historiographical nor theological approach, but rather a poetic one that sees her utterances as songs that need an innovative approach in order to sing fully in English. Priya grew up hearing Andal’s collection of hymns sung at weddings and festivals. For decades, the holy-poet-become-goddess hovered in her imagination like a cloud over the sea, nebulous yet lit on the horizon of the liminal, until one day she decided the goddess must land on the shore of her first language: English. At this time she met Ravi Shankar, the Indian American poet and professor, who shared her passion for Tamil literature and Andal in particular.

That’s how the two of us became collaborators and in working together, we realized that a new approach was necessary if we were to do justice to the richness and spiritual intensity of these poems. Our intention is to make the poems come alive in English and so we dispensed with attempting a literal translation, verging instead into a polyphonous mode of capturing the multiplicity inherent in Andal’s songs by experimenting with form and sometimes including multiple versions of the same poem, as well as more collaborative translations. We spoke about our aspirations for this project to the elder of the two scholar-poets whom we consulted for help with the manuscript, octogenarian S.V. Seshadri, who helped us understand the complexity of Tamil Sangam era (2 BCE–2 CE) poetics in which Andal composed.

Andal’s first work, Tiruppavai (The Path to Krishna) is famed in Southern India, especially Tamil Nadu and sung by devotees during the sacred month of Markali. It is a lyrical and bhakti-filled description of vows undertaken by young women to obtain a good husband and is a song of congregational worship.

To provide a sense of the difficulty in translating Old Tamil, consider the following saying, poem and verse which present conundrums because of specific poetic codes and suggested ‘unmarked’ meanings compressed in each.

- ‘If you wish to destroy a thorn tree, call for the axe.’

- When told of her lover’s interest in another woman she smiled and said:

Drunk

with honey

from the opening lotus

pond the bee flies

to its hive in the sandalwood grove.

- Bring me his garments translucent, yellow, shimmering

as pollen through which the dark majesty of his thighs rise

glistening and drape me in his scent

so my every pore is perfumed. Then shall I be content!

The meanings of these three distinctive utterances need contextual clues in order to be unravelled. The first is an epigram that translates as words of advice:

If you wish to kill your enemy, O king, do so quickly.

The second is a secular poem in which the woman implies that her lover enjoys her deeply, mutually as she enjoys him, that their love is sweet and as fresh and pure as blossoming lotuses whose roots are deep and entwined as their vows to each other and that he will carry her love with him as faithfully as a bee returning to its hive as he journeys to his home high on the hill far away, and that their love will remain fragrant and long lasting as sandalwood until he returns to her.

The third is a sacred hymn that follows the rules of Old Tamil prosody in making a similar, yet very different erotic demand. Unlike the earlier poem, its desires are not veiled in symbolic allegory. But while it seems direct, it could misdirect, for the desired ‘he’ is not a mortal, but the Protector of Universes, the dreaming Vishnu, who, in the starry cosmic ocean, rests on the cloud-coloured serpent Ananta, who represents ‘the eternity of time’s endless revolutions’. The speaker of this verse is Andal who was possibly fifteen at the time. This instance of sexual and devotional intensity is from the Nacciyar Tirumoli, Song Thirteen, verse one. In theological terms, the yellow silk is often interpreted as the veiling of the sacred wisdom of Narayana’s body. The speaker’s assumed extreme familiarity with god gives these poems their uncanny edge of heightened eroticism.

We have translated her bhakti or devotion-drenched hymns as The Autobiography of a Goddess. Alongside, we refer to the commentary of the 13th century scholar, Periyavaccan Pillai (Veritable Great Teacher) as he is the most revered early interpreter of these hymns.

We have translated her bhakti or devotion-drenched hymns as The Autobiography of a Goddess. Alongside, we refer to the commentary of the 13th century scholar, Periyavaccan Pillai (Veritable Great Teacher) as he is the most revered early interpreter of these hymns. We sought the guidance of Dr S. Raghuraman-Pulavar who has lectured and published extensively on the daunting Tholkaapiyameypaatiyal and is possibly the leading expert on cen or ancient Tamil grammar and poetics. He induced our passion for the holographic Tamil poetic form. At times we consulted Dr Prema Nandakumar, scholar of visistadvita philosophy (qualified non-dualism) to tease out inherent theological references. Also invaluable to us were Vidya Dehejia’s Andal and Her Path of Love: Poems of a Woman Saint from South India (State University of New York Press, 1990) and Archana Venkatesan’s The Secret Garland: Antal’s Tiruppavai and Nacciyar Tirumoli (Oxford University Press, 2010), the two most recent translations of Andal’s work into English, albeit in a very different form and manner than what we have attempted.

Drowning in love and language

As a bhakti saint, Andal composed in cen or Old Tamil. However, this implied following many of the rules codified in the Tolkaappiyam, the classical treatise on grammar and poetics. She did not follow its tinnai conventions that morph moods of love and evocative landscape into symbolic spaces of passion but worked with much of its other riddling complexities. Compounding the difficulty of translating this work, here is the catch: the ancient Tamils relied on the listeners and readers to ‘complete’ the poems by comprehending various allusions, including the invocation of myth and the utilization of complex poetic strategies. This is similar to postmodern reader-response theory that argues against the concept that meaning is embedded in the text, but rather believes that meaning only emerges dialectically between the relationship of text and reader.

A staggeringly exhaustive and codified compendium, the Tolkaappiyam recommends that both poet and reader immerse themselves in systems of poetics, grammar, versification, forms, metrical and rhythm schemes and possess an adequate mental thesaurus before attempting to read or write poetry. The level of sophistication of classical Tamil poetry is profound and there have been many manuals written on its prosodic elements, which included an elaboration of elullu, or the phoneme, acai, or the metreme, cir, or the metrical foot, talai, or the linkage, ali, or the line, and totai, or ornamentation. Sangam literature, written in classical Tamil, offers us poetic works with re-combinations of the above elements in extremely refined ways.

As a bhakti saint, Andal composed in cen or Old Tamil. However, this implied following many of the rules codified in the Tolkaappiyam, the classical treatise on grammar and poetics. She did not follow its tinnai conventions that morph moods of love and evocative landscape into symbolic spaces of passion but worked with much of its other riddling complexities.

For example, Andal’s Tiruppavai is written in eight-line stanzas in the koccakakalippa meter, or four metrical feet, whereas the Nacciyar Tirumoli employs five different meters in lines that range from four to eight feet. We have not attempted to mimic that complex meter in English, as it would be a virtual impossibility, as well as resultant in a stilted form of poetry. We have instead attempted to abide in her imagery and metaphor, and find a suitable form that reinforces and mirrors the ecstatic content of her songs, especially as relates to the traditions of Tamil love poetry.

Take this anonymous verse about amorous poetry which states:

Aagapaattuvaannam

mudindadu polmudiyadadi

aahum

Here’s a literal translation, compounded by the difficulty that Tamil morphology is akin to a mantra with a maraiporul, or a secret hidden meaning:

Love-poetry sounds/forms/presents

complete as if not complete

is like that

or, put another way:

Love poetry seems

completed

but isn’t.

The loop is only completed when the listener participates in the performance of the poem somatically and collectively, and that kind of participatory model of interpretation points to the thriving local literary culture that existed at that time. Translating this element of historicity for a contemporary audience now provides us the space and freedom to make multiple connections between lines and between verses, and productive misinterpretations notwithstanding, allows for the liberation of imagination in trying to bring to light the numerous flowing undercurrents and holographic affects that are taking place simultaneously. For this reason, we have developed a radical mode of translation meant to illuminate a wide spectrum of Andal’s spirit, rather than to slavishly hew to the letter of her work.

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of Zubaan Books. You can buy Andal: The Autobiography of a Goddess, here.

ARCHIVE

Dalit Women as Active Participants in Ambedkarite Movement

Majhi aaji manhayachi

Ovi hee jatya warr,

Bhim banala sawali

Koti koti chya mathywar

My grandmother used to sing

This couplet while working the stone grinder

Bhim has become a shelter

Over the heads of millions.

The lines above are from Majhi Aaji, a poem by Kiran Sonwane, whose most popular version in Maharashtra is the one sung by Aniruddha Vankar. From the song, it is apparent that when Dalit women conceive of literature or music, they choose Ambedkar as their protagonist or hero. In their works, he is portrayed as no less than their emancipator.

Their portrayal of Ambedkar as a staunchly feminist ideal makes the role of Dalit women in the Ambedkarite movement significant on two levels: first as active participants in the movement, and second, as producers of literary narratives, including the ‘cradle songs’ that are crooned to youngsters.

In Vidarbha – and I am sure in other regions of Maharashtra – the tradition of Bhim Palana, or Bhim’s cradle songs, are an antithesis to the children’s songs based on mythological themes. A Bhim Palana is written with the intent to educate children about figures such as Ambedkar, to create individuals and citizens who will uphold the notion of equality, liberty and fraternity in their social and personal life.

Jyotiba Phule

After Mahatma Phule’s massive attack on the inhumane, unnatural and artificial caste system, which he did by opening the doors of education for girls across all castes, it was Babasaheb Ambedkar who went to great lengths to conceive of strategies to educate women, especially Dalit women. Urmila Pawar and Meenakshi Moon have compiled the most significant book on Dalit women’s history of struggle and triumphs, We Also Made History. They say in the book: “…the education of women and girls was an integral part of Ambedkar’s vision of social emancipation for the Dalits.” Some of his speeches, made on occasions of historical importance for the struggle, are quoted extensively, notably the speech addressing women at Mahaad satyagraha and the 1942 speech at the All-India Dalit Mahila Parishad held on 20th July 1942 in Nagpur.

From the moment he entered public life in 1927, Ambedkar’s movement made education for women integral to its agenda. He nurtured the desire for education within the hearts of Dalit women, using the Buddha’s egalitarian teachings as a basis for his arguments. Inspired, barely-educated women and those who had never climbed up the stairs of a school started to write songs that featured him and sing them.

From the moment he entered public life in 1927, Ambedkar’s movement made education for women integral to its agenda. He nurtured the desire for education within the hearts of Dalit women, using the Buddha’s egalitarian teachings as a basis for his arguments

From the 1940s onwards, Parbatabai Meshram from Nagpur worked for Ambedkar‘s movement. She wrote a few songs about how Ambedkar helped him feel confident and instilled the vision of a casteless society among them. In one of her songs she says:

He gave up his life for the good of the people,

That’s why, bai, I am passionate about Buddha.

Some say Buddha is Vishnu reborn,

But I ask you, bai, was Vishnu like the Buddha?

Did Brahma, Vishnu, Mahesh, ever behave like this?

That’s why, bai, I am passionate about Buddha.

In India, irrationality is propagated through the telling and retelling of mythological stories. All this is done in the name of religion, giving it a veneer of respectability that makes it very difficult to renounce. Yet, Ambedkar’s movement replaced such illogic with the history of the Buddha and his egalitarian teachings. The result was an incredible increase in education among the Mahar (now Buddhist) people, especially women. Parbatabai Meshram wrote:

Let your self-respect awake,

Don’t ask for charity.

Bhimdada told us this and left us:

Get ready to serve the people.

The sculptor of our lives said this and left.

Such songs do glorify or deify, but they intend only to convey history and inculcate a sense of dignity among listener and singer alike. They envision a casteless future with equality, liberty and fraternity at its foundation.

Thus unfolded on India’s literary scene of the time a unique phenomena. A living human being became a vigorous and passionate symbol in literary expression, as Ambedkar became both symbol and subject in the creative imagination of Dalit women’s songs.

The ‘Ambedkari Jalsa’ introduced by Bhimrao Kardak in the late 1920s had already planted Ambedkar‘s ideology into the musical tradition of Dalits. Dalit women further created the Bhim Palana genre, a result of their close association with the community’s earlier musical traditions. They are proof, as Mark Abel, who describes himself as a Marxist musicologist who works on the aesthetics of music and its interface with history and politics, has pointed out in Is Music a Language?, “creative musical ideas do not emerge from a mystical process of inspiration, but are the result of a practical and mental engagement with existing musical culture, or musical language.”

![Jilha Yuvak Sangh. Bhimrao Kardak (In the middle row, sitting on chair, second from the right) [Photo Credits: Yogesh Maitreya]](http://indianhistorycollective.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Bhimrao-Kardak-1.jpeg)