ARCHIVE

An Indian in New York (1913-1916)

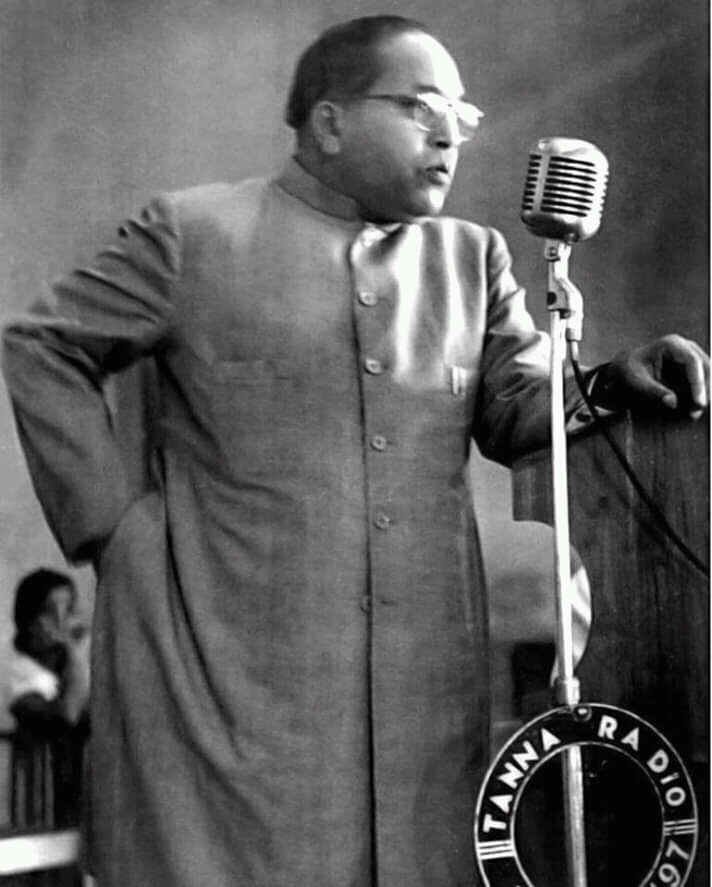

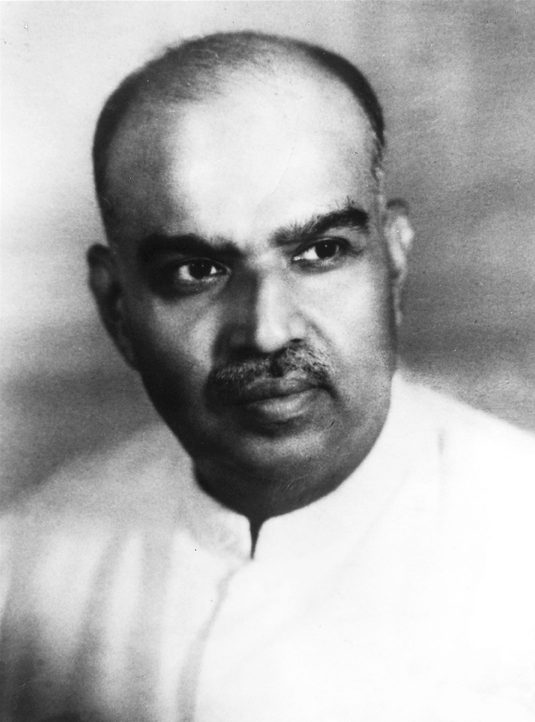

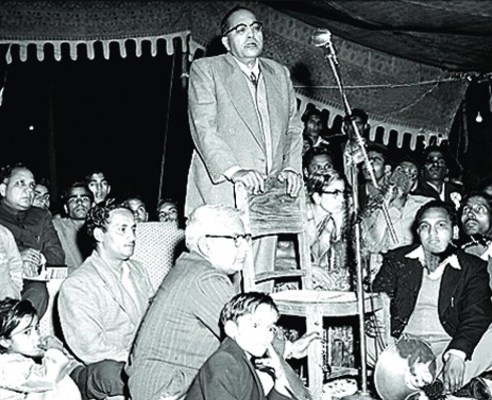

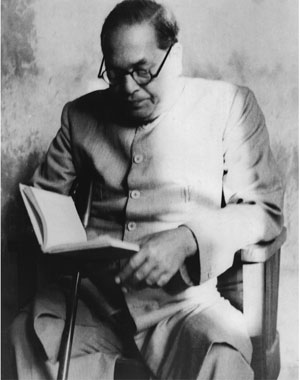

A young Ambedkar during his Columbia University days. Wikimedia Commons.

Young Ambedkar’s emerging academic understanding of caste was helping him give systematic expression to his many prior years of the lived experience of systemic caste prejudice. Alongside and as impetus to this were also his widening experiences regarding issues of race, class and gender. To some extent, this new exposure was a result of his coursework at Columbia. But much of this exposure came more concretely, from treading the streets of upper Manhattan and Harlem.

Describing his usual New York day, Ambedkar emphasized that the vast majority of his time, some 18 hours daily, was spent on campus, either attending lectures and seminars, or otherwise working in Columbia University’s magnificent and exceptionally-stocked Low Library. But he often ate off of campus, opting to eat only one meal per day to save both time and money. For food he spent on average $1.10 daily, which would buy him a cup of coffee, two muffins, and either a meat or a fish dish. He was on a tight budget. New York City living was not cheap, and he had to send money home to his family as well. But that was not all. His voracious reading habit, that had been cultivated in young Ambedkar within the shadow thrown by the Bombay-gothic tower of Elphinstone, had only grown stronger atop the grand staircase of the Roman-neoclassical library of Columbia. Ambedkar was now in the first stage of what would turn out to be a life-long obsession with collecting books. He spent all the leisure time that he had browsing Manhattan’s numerous second-hand book shops and sidewalk stalls, amassing a personal library of some 2000 volumes during his three-year stay.

The quest for books led young Ambedkar out of upper Manhattan down to 42nd street on Fifth Avenue, where the imposing beaux-arts styled New York Public Library had recently opened its doors, and opened them to all – including to black people and to women. So impressed was Ambedkar with the public library that upon learning of the death of Sir Pherozeshah Mehta in Bombay, and the Bombay municipality’s plan to prominently erect his statue, Ambedkar shot off a provocative letter from New York to the Bombay Chronicle, the English-language weekly that Mehta had himself launched in 1910. Ambedkar, fresh from another inspiring visit to the New York Public Library, argued in his letter that erecting a public library in Bombay instead of a ‘trivial and unbecoming’ statue would be a far better tribute to the memory of this great man:

It is unfortunate that we have not as yet realized the value of the library as an institution in the growth and advancement of a society. But this is not the place to dilate upon its virtues. That an enlightened public as that of Bombay should have suffered so long to be without an up-to-date public library is nothing short of disgrace and the earlier we make amends for it the better. There are some private libraries in Bombay operating independently by themselves. If these ill-managed concerns be mobilized into one building, built out of the Sir P.M. Mehta memorial fund and called after him, the city of Bombay shall have achieved both these purposes.

It is unfortunate that we have not as yet realized the value of the library as an institution in the growth and advancement of a society. But this is not the place to dilate upon its virtues. That an enlightened public as that of Bombay should have suffered so long to be without an up-to-date public library is nothing short of disgrace and the earlier we make amends for it the better. There are some private libraries in Bombay operating independently by themselves. If these ill-managed concerns be mobilized into one building, built out of the Sir P.M. Mehta memorial fund and called after him, the city of Bombay shall have achieved both these purposes.

The week following Pherozeshah Mehta’s death in Bombay, Booker T. Washington died in Tuskegee, Alabama. Washington, who had been born into slavery, was the most prominent Southern black activist of his day. As Principal of the Tuskegee Institute and author of a best-selling autobiography, Up From Slavery, Washington’s work and writings would have been well known to Ambedkar. Indeed, he would have heard his name prior to reaching America given that his patron, Maharaja Sayajirao Gaikwad, had long before taken to referring to the great social reformer Jotirao Phule, author of Gulamgiri (or, Slavery) as ‘India’s Booker T. Washington’.

The streets of upper Manhattan were beginning to buzz with a new black consciousness that expressed itself not only socio-politically – as for example with the writings and activism of W.E.B. DuBois and the National Negro Committee (which would soon become the NAACP) – but also aesthetically, with emerging literary, theatrical and musical innovations that would set the stage for the later Harlem Renaissance.

Besides his letter to the Bombay Chronicle, Ambedkar sent off numerous letters to family and friends in India during his stay in New York. The letters show that Ambedkar was as attuned to issues regarding gender as he was to those regarding race. One worth mentioning was addressed to a friend of his father, a retired Jamedar of the Indian army, also from the Mahar caste. In it, he implored the recipient – who was the father of a young girl gaining notoriety for having made it all the way to 4th standard in school, unheard of for a Mahar girl – to preach the idea of education to anyone from their community who was willing to listen to him. Ambedkar wrote that he should continue the education of his daughter, and that the entire community would progress more quickly if males and females were educated side-by-side, with no difference between them.

This letter, too, can be seen to reflect the environment Ambedkar now found himself in. For, alongside the emergence of a new black consciousness, New York City was also buzzing with the tireless activism of suffragists demanding the enfranchisement of women in America. And some of the most dynamic of these suffragists were young Ambedkar’s fellow Columbia classmates – and some, as luck would have it, turned out to be his favourite professors.

This letter, too, can be seen to reflect the environment Ambedkar now found himself in. For, alongside the emergence of a new black consciousness, New York City was also buzzing with the tireless activism of suffragists demanding the enfranchisement of women in America. And some of the most dynamic of these suffragists were young Ambedkar’s fellow Columbia classmates – and some, as luck would have it, turned out to be his favourite professors.

The summer just prior to Ambedkar’s arrival at Columbia, his soon-to-be classmate, Chinese-born Mabel Ping-Hua Lee was one of fifty horse-back suffragettes leading a procession of 10,000 people up Fifth Avenue to Carnegie Hall. Among those marching were Ambedkar’s future philosophy professor John Dewey and his future economics professor Vladimir Simkhovitch. In the spring of 1914, Lee published, in a campus paper, an article entitled ‘The Meaning of Woman Suffrage’, advocating for equality of educational opportunities and the economic liberation of women. In terms identical to those Ambedkar would himself utter frequently in his later speeches, Lee referred to ‘equality of opportunity’ as the essence of ‘democracy’. To her, feminism meant ‘nothing more than the extension of democracy or social justice and equality of opportunities to women’.

Lee, supervised by Simkhovitch, and Ambedkar, supervised by Seligman, were together enrolled in the course leading toward the PhD in economics at Columbia’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Later, Mabel Lee would become the first Chinese woman to earn a doctorate in economics in the United States, just as Ambedkar was one of the first Indians (and certainly the first Dalit) to do so.

Vladimir Simkhovitch, apart from being Lee’s doctoral supervisor, was one of the world’s leading experts in socialist economics and Marxist thought. Ambedkar enrolled in his Econ 114 (Marx and Post-Marxian Socialism), Econ 303 (Seminar on Political Economy), Econ 109 (History of Socialism), Econ 242 (Radicalism and Social Reform), and Econ 119 (Economic History) – that’s five full courses on Marxism and socialism! At least for some of these courses, if not out of wider interest, Ambedkar would have had to have purchased some of Marx’s original writings; books by Marx must have been among the 2000 volumes that he had acquired while in New York. As we will later learn, the vast majority of these 2000 books never made it back with Ambedkar to India. Several of them, such as the writings of John Dewey, Ambedkar subsequently repurchased elsewhere. But curiously, we can find none of Marx’s books among Ambedkar’s extant library. It seems that his later experience with Brahmanical Indian Marxists so soured Ambedkar’s view of Marx that he never even bothered to replace his lost books.

John Dewey (left) and Edwin Seligman (right). Ambedkar’s professors at Columbia University.

One book that Ambedkar purchased in New York that clearly made it with him to India, as apparent from his inscription, was Mrs Rhys Davids’ Buddhism: A Study of the Buddhist Norm (first published in New York in 1912). This book focused on the most ancient, Pali sources of the Buddhist tradition. Ambedkar inscribed the first page in his hand, ‘Columbia Varsity, New York’, and then later on the right-hand side adjacent to it, ‘Bombay, India’. The book and its inscription both show a continuity of his interest in Buddhism, initiated by Dada Keluskar years before.

Of course, Ambedkar’s main focus of study, and the degree toward which he was working, was economics. The study of ancient Buddhism proved useful toward the first iteration of his Master’s thesis, entitled ‘Ancient Indian Commerce’, which may have first been written up as an original research paper for submission as a component of the MA examination. About 75 pages of this manuscript are extant, first covering the trade and commercial relations of ancient India with ancient Egypt, west and east Asia, and then the Greeks and the Romans. Ambedkar strikes a proud, nationalist tone in the work, citing sources to emphasize the superior science, technology and splendours of ancient India over ancient Europe:

It is in the orient, especially in these countries of old civilization, that we must look for industry and riches, for technical ability and artistic productions, as well as for intelligence and science, even before Constantine made [the Roman empire] the centre of political power. Nay, all branches of learning were affected by the spirit of the orient, which was her superior in the extent and precision of its technical knowledge, as well as in the inventive genius and ability of its workman.

It is in the orient, especially in these countries of old civilization, that we must look for industry and riches, for technical ability and artistic productions, as well as for intelligence and science, even before Constantine made [the Roman empire] the centre of political power. Nay, all branches of learning were affected by the spirit of the orient, which was her superior in the extent and precision of its technical knowledge, as well as in the inventive genius and ability of its workman.

Remember that Ambedkar was by now thoroughly familiar with the political, economic, and intellectual history of classical Europe and Ancient Rome, so his claims regarding ancient India’s technical superiority were not merely rhetorical.

‘Ancient Indian Commerce’ then goes on to treat of India’s commercial relations in the Middle Ages, covering industry, trade and commerce throughout the rise of Islam and the expansion of western Europe. The next couple of chapters are missing, and the extant thesis ends with a chapter entitled ‘India on the Eve of the Crown Government’. In this chapter, too, Ambedkar exhibits a fierce nationalism, excoriating British imperialism and taking to task historians of British India who misrepresent the achievements of India prior to the arrival of the British: ‘Not only have they been loud in their denunciation of the Moghul and the Maratha rulers as despots and brigands, they cast slur on the morale of the entire population and their civilization’. What follows are 20 pages of argument and evidence, replete with tables, graphs and charts, of how India systematically contributed to the prosperity of Britain, while itself consistently degenerated, being beaten down and sucked dry.

This tour-de-force of Indian nationalist commercial and economic history then concludes with these damning words:

The supplanters of the Moghuls and the Marathas were persons with no better moral fiber, and the economic condition of India under the so-called native despots was better than what it was under the rule of those who boasted being of superior culture. It is with industries ruined, agriculture overstocked and overtaxed, with productivity too low to bear the high taxes, and with few avenues for display of native capacities, the people of India passed from the rule of the Company to the rule of the Crown.

The supplanters of the Moghuls and the Marathas were persons with no better moral fiber, and the economic condition of India under the so-called native despots was better than what it was under the rule of those who boasted being of superior culture. It is with industries ruined, agriculture overstocked and overtaxed, with productivity too low to bear the high taxes, and with few avenues for display of native capacities, that the people of India passed from the rule of the Company to the rule of the Crown.

American academia was far more accommodating of this magnitude of critique of British imperialism than either British or Indian universities were. Nevertheless, for reasons still unknown to us, Ambedkar abandoned the topic of ancient Indian commerce as his MA thesis, and instead drafted and submitted a much more technical, scope-limited, and positivist text entitled ‘Administration and Finance of the East India Company’. The most likely explanation is that Professor Edwin Seligman had been assigned as Ambedkar’s supervisor, and Seligman was a no-nonsense, technical economist, who viewed the subject of economics as a fact-based, impartial ‘science’. Seligman taught Ambedkar ‘the Science of Finance’, and was averse to the introduction of subjective viewpoints. As Seligman would write 10 years later in a Preface to Ambedkar’s published Ph.D., ‘The value of Mr. Ambedkar’s contribution to this discussion lies in the objective recitation of the facts and the impartial analysis…’.

The officially-submitted thesis, at only 45 pages in length, avoided speaking of history at all (the opening line reads: ‘Without going into the historical development of it…’), and was more restrained in claims regarding the systematic cultural destruction and impoverishment of India by the British. Nevertheless, in the end, Ambedkar exhibits the irrepressibility of his innate need to call out injustice, and closes the thesis with these reproaching words:

It remains, however, to estimate the contribution of England to India. Apparently the immenseness of India’s contribution to England is as astounding as the nothingness of England’s contribution to India….England has added nothing to the stock of gold and silver in India; on the contrary, she has depleted India—‘the sink of the world’.

It remains, however, to estimate the contribution of England to India. Apparently the immenseness of India’s contribution to England is as astounding as the nothingness of England’s contribution to India… England has added nothing to the stock of gold and silver in India; on the contrary, she has depleted India—‘the sink of the world’.

The thesis was accepted by Seligman and passed, and on 02 June 1915 Ambedkar was awarded the degree of Master of Arts in Economics. He had completed the requisite 30 credit hours for the M.A., but 60 credit hours were required for a doctorate. He thus continued in his coursework and in his research and writing, and from that point on, all the credits were counted toward the completion of his Ph.D.

Ambedkar continued working on the ‘science of finance’ as the subject of his doctoral dissertation under Seligman at Columbia. The tentative title for his Ph.D. thesis was ‘The National Dividend of India’, a historical and analytical study of Indian finance. But interestingly, following the award of his M.A. in economics, nearly every course that Ambedkar enrolled in as credit toward his Ph.D. in economics were non-econ courses. After the summer of 1915, Ambedkar took only one economics course (econ 183, on Railways); all of the rest were in languages (French and German), History (4 courses), Philosophy (4 courses), Politics (1 course), and Anthropology (4 courses).

All four of these Anthro courses were taught by Alexander Goldenweiser, himself a student of Franz Boas, the ‘father of American anthropology’. Boas also taught Anthropology at Columbia, in fact he co-taught a course with his friend John Dewey during the same semester that Ambedkar was attending Dewey’s philosophy course. In short, there is no doubt that young Ambedkar was exposed to the modern anthropological method of Boas. One of the primary features of Boas’ approach was his flat rejection of racial typologies which were so popular in late 19th-century anthropology. These racialist theories attributed fixed mental and physical characteristics to specific races. Boas (and indeed Dewey and Goldenweiser) rejected race as the dominant characteristic of a peoples and emphasized far more malleable and conditional characteristics such as culture, history and psychology instead.

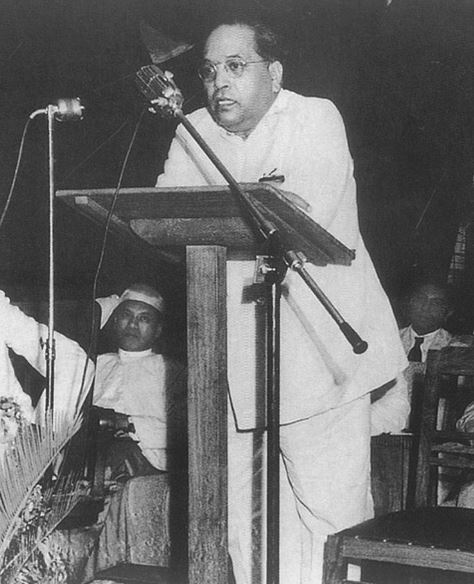

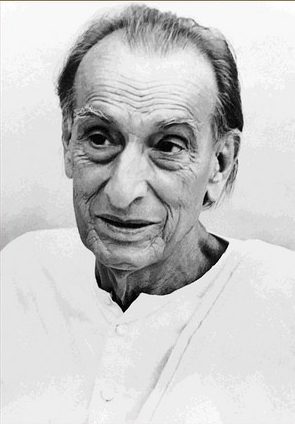

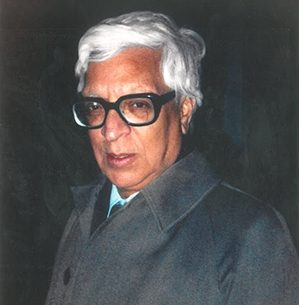

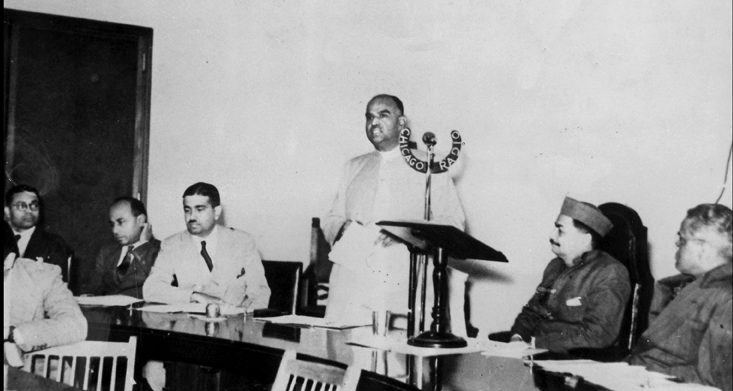

Dr. BR Ambedkar presiding over the joint Columbia Bicentennial – American Alumni Banquet at National Sports Club of India, New Delhi, October 30, 1954. Columbia University.

In May 1916, Ambedkar wrote an extensive and innovative research paper for one of Goldenweiser’s general ethnology courses, where the influence of Boas’ ideas against racial fixity is clear. In addition to opposing a basic Marxist tenet about class antagonism that Ambedkar learned from Simkhovitch’s courses, also discernable within the paper are many echoes of Ambedkar’s everyday experiences regarding race and gender from his wanderings away from campus. In the paper, entitled ‘Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development’, Ambedkar argued that caste was a distinct social category that could not be accounted for either by theories of race or by class antagonism. Rejecting the standard explanation of the racial origins of caste popular in colonial ethnography (i.e. a consequence of Aryan invasions wherein the darker-skinned earlier inhabitants were subjugated) and rejecting the dominant sociological claim that caste was maintained through a hierarchy of purity and pollution, Ambedkar boldly asserted that the essence of caste was the control of women’s sexuality – foremost, the practice of endogamy.

In the paper, entitled ‘Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development’, Ambedkar argued that caste was a distinct social category that could not be accounted for either by theories of race or by class antagonism. Rejecting the standard explanation of the racial origins of caste popular in colonial ethnography (i.e. a consequence of Aryan invasions wherein the darker-skinned earlier inhabitants were subjugated) and rejecting the dominant sociological claim that caste was maintained through a hierarchy of purity and pollution, Ambedkar boldly asserted that the essence of caste was the control of women’s sexuality – foremost, the practice of endogamy.

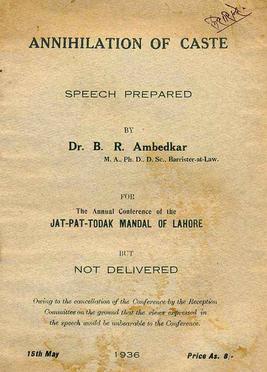

Ambedkar was exceptionally proud of the work. A year later, it became his first scholarly publication, appearing in the professional journal The Indian Antiquary. Later, when publishing his Ph.D. dissertation as a book, he is described on the title page as the ‘author of Castes in India’. Years later, in 1944, when he was publishing a third edition of his explosive essay Annihilation of Caste, he revealed that the third edition had been delayed for so long after the print run of the 1937 second edition was exhausted because he had been trying to find the time to recast Annihilation of Caste ‘so as to incorporate into it another essay of mine called Castes in India’. Indeed, even Ambedkar’s latest writings from the 1950s, when he was nearing the end of his life, referenced assertions that he had first posited as a young doctoral candidate at Columbia.

In many ways, Ambedkar’s ‘Caste’ paper captured everything other than ‘the science of finance’ that Ambedkar had learned and discovered, both on and off campus, during his three formative years in New York. The formal structure of this rich education was giving shape to his profound lived experiences being Dalit – all of those childhood experiences that he had written about in his autobiographical fragments, Waiting for a Visa – forging an uncommon and unprecedented concatenation of events that helped to make Ambedkar the extraordinary person that he was.

This excerpt has been reproduced with permission from Aakash Singh Rathore from the book Becoming Babasaheb: The Life and Times of Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar: Birth to Mahad (1891-1929) written by Aakash Singh Rathore. All rights reserved. Unauthorised copying is strictly prohibited. You can buy the book here.

ARCHIVE

Contesting Power – Contesting Memories: the Obelisk at Koregaon

The obelisk at Koregaon is characterised by a surprising commemorative history. A memorial to a bloody encounter within an imperial war, this monument provides a case study which illustrates that contestations of memories often bear the imprint of contestations for hegemony that are played out in the present.

The obelisk at Koregaon in Western India, built as a demonstration of empire builders’ belief in their own power and military prowess, serves a similar function today, but for a different group of people: the former Untouchables who had collaborated with the colonizers against what they perceived as a tyrannical indigenous regime.

The recently emerged tradition of an annual pilgrimage to the memorial, should be seen as an effort at creating and popularizing an alternative culture of the former Untouchables, now known as Neo-Buddhists. While Indian society grapples with the problem of accepting the equality of its various castes, one can witness different pathologies of memory surrounding the monument. Today, both amnesia and pseudomnesia are associated with the Koregaon memorial, defying the locus of a person in the discourse on social justice in present-day India. The memorial had faded into oblivion from British public memory long before the end of the imperial rule. However, it has undergone a metamorphosis of commemoration and now signifies something quite different from what was originally intended.

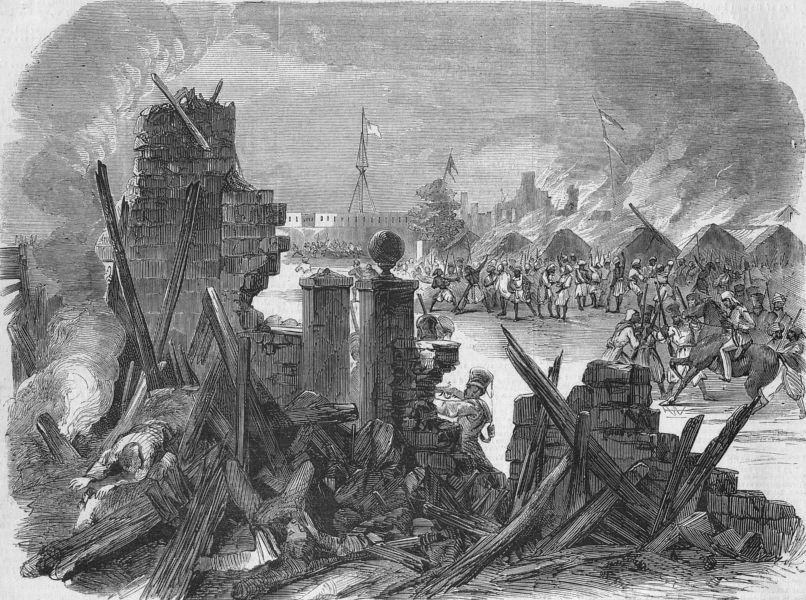

The Battle of Koregaon and its Memorial

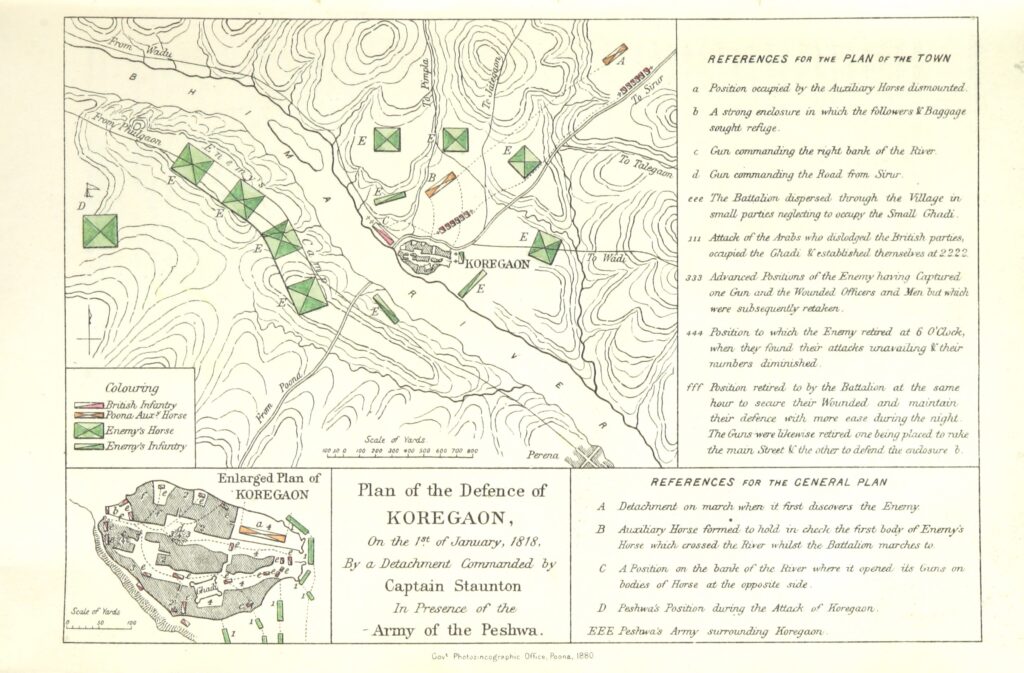

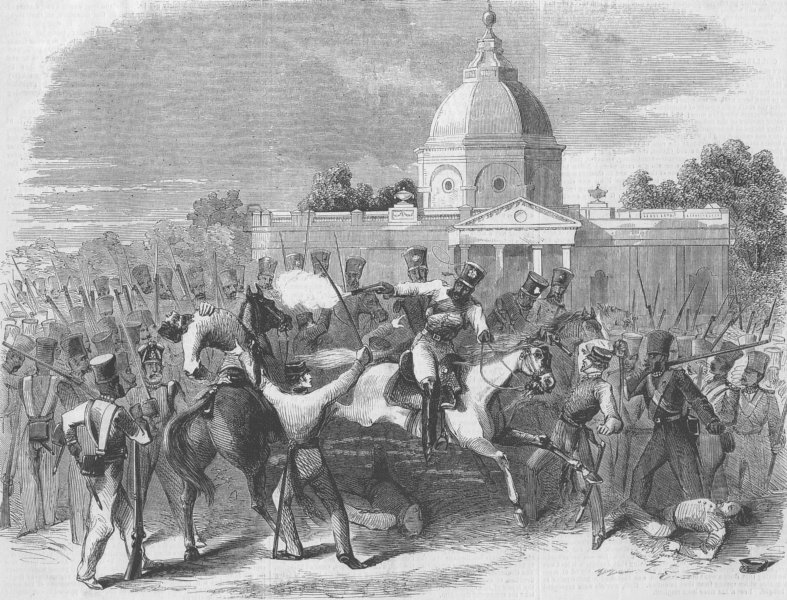

British defence plan during the Battle of Koregaon from Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency (Ed). Sir James M. Campbell, p. 259. Published in 1896. British Library.

The political ascendancy of the British East India Company in Eastern and Northern parts of India dates back to the battle of Plassey in 1757. From then on it gradually began extending its political hold to the other parts of India. During the same period, from their base in Pune in Western India, the Peshwa rulers (1707-1818) were also extending their political influence. Clashes between the Peshwas and the Company seemed inevitable. On 1 January 1818, a battalion of about 900 Company soldiers, led by F. F. Staunton from Seroor to Pune, suddenly faced a 20,000-strong army commanded by the Peshwa himself. The encounter took place at the village of Koregaon on the banks of the river Bheema. In the words of Grant Duff, a contemporary official and historian, “Captain Staunton was destitute of provisions, and this detachment, already fatigued from want of rest and a long night march, now, under a burning sun, without food or water, began a struggle as trying as ever was maintained by the British in India.” The battle was not decisively won by either side, but in spite of heavy casualties, Staunton’s outnumbered troops managed to recover their guns and carry the wounded officers and men back to Seroor.

As it was one of the last battles of the Anglo-Maratha wars, which ended with a complete victory of the Company, the encounter quickly came to be remembered as a triumph. The East India Company wasted no time in showering recognition on its soldiers.

While Staunton was promoted to the honorary post of aide de camp by the Governor General, the battle received special mention in Parliamentary debates next year. A memorial was commissioned and a year later, Lt Col Delamin, who was passing by the village, could already witness the construction of a 60-foot commemorative obelisk.

The Koregaon memorial still stands intact today. It is supposed to commemorate the British and Indian soldiers who ‘defended the village with so much success’ when the British East India Company confronted the Peshwa army in a ‘desperate engagement’. Marble plaques adorn the four sides of the obelisk. The two plaques in English are accompanied by translations into the local Marathi language. The Memorial Plaque declares that the obelisk is meant to commemorate the defence of Koregaon wherein Captain Staunton and his corps “accomplished one of the proudest triumphs of the British army in the East.” Soon after, the word ‘Corregaum’ and the obelisk were chosen to adorn the official insignia of the Regiment. In the Parliamentary debates in March 1819, the events were described as follows. “In the end, they not only secured an unmolested retreat, but they carried off their wounded!” In his volume published in 1844, Charles MacFarlane quotes from an official report to the Governor calling the engagement “one of the most brilliant affairs ever achieved by any army in which the European and Native soldiers displayed the most noble devotion and the most romantic bravery.” Twenty years later, Henry Morris confidently added: “Captain Staunton returned to Seroor, which he entered with colours flying and drums beating, after one of the most gallant actions ever fought by the English in India.” Later chroniclers of colonial rule continued to shower praise on the plucky Company force for displaying “the most noble devotion and most romantic bravery under the pressure of thirst and hunger almost beyond human endurance.” In 1885, even the ‘Grey River Argus’, a newspaper published in far-off New Zealand, described the battle in glowing terms. After the turn of the century, though, the colonial commemoration began to fade and gradually the event slipped from Britain’s public memory. The battle is now only mentioned in specialized literature on military history as an example not of British martial capabilities, but of that of the Sepoys.

Memories: ‘Ours’ and ‘Theirs’

Today the memorial finds itself just off a busy highway toll booth – a common site in the post-globalisation Indian landscape. Every New Year Day, the urban middle classes who need to use the highway, remind each other to avoid the particular stretch of the highway that passes by the memorial. Their reason for doing so is that “those people would be swarming their site at Koregaon.” Indeed, the memorial has become a site of pilgrimage attracting thousands of people who gather there every 1 January. If one asks the pilgrims what brings them together, there is a clear answer.

“We are here to remember that our Mahar forefathers fought bravely and brought down the unjust Peshwa rule. Dr Ambedkar has started this pilgrimage. He asked us to fight injustice. We have come to take inspiration from the brave soldiers and Dr Ambedkar’s memories.”

Initially, one might be baffled by this admiration for the native soldiers who fought on the British side and lost their lives in a fight against their own countrymen. A careful scrutiny of the list of casualties inscribed on the memorial reveals, however, that twenty-two names from amongst the native casualties listed end with the suffix “-nac”: Essnac, Rynac, Gunnac. The suffix ‘-nac’ was used exclusively by the untouchables of the Mahar caste who served as soldiers. This observation becomes particularly relevant when considered within the context of the caste profile of the Peshwas, who were orthodox and high-caste Brahmin rulers. The story of Koregaon is thus not just about a straightforward struggle between a colonial and a native power. There is another important but largely ignored dimension to it: caste.

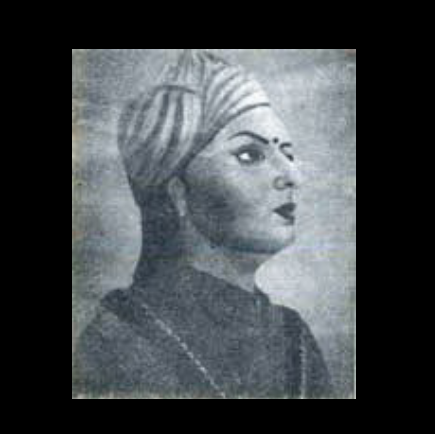

Peshwa Bajirao II, who fought at the Battle of Koregaon. Coloured lithograph, Chitrashala Press, Poona, 1888. Wellcome Collection.

The Peshwas, Brahmin rulers of Western India, were infamous for their high caste orthodoxy and their persecution of the untouchables. Numerous sources document in great detail that under the Peshwa rulers, the ‘untouchable’ people who were born in certain so-called low castes were given harsher punishments than high-caste people for the same crimes. They were forbidden to move in public spaces in the mornings and evenings lest their long shadows defile high-caste people on the streets. Besides physical mobility, occupational and social mobility were also denied to these people who formed a major part of the population. Human sacrifices of ‘untouchable’ people were not uncommon under these eighteenth century rulers who had framed elaborate rules and mechanisms to ensure that the untouchables stayed just as their name suggests – untouchable. In 1855, Mukta Salave, a 15-year-old girl from the untouchable Mang caste who attended the first native school for girls in Pune, wrote an animated piece about the atrocities faced by her caste:

‘Let that religion, where only one person is privileged and the rest are deprived, perish from the earth and let it never enter our minds to be proud of such a religion. These people drove us, the poor mangs and mahars, away from our own lands, which they occupied to build large mansions. And that was not all. They regularly used to make the mangs and mahars drink oil mixed with red lead and then buried them in the foundations of their mansions, thus wiping out generation after generation of these poor people. Under Bajirao’s rule, if any mang or mahar happened to pass in front of the gymnasium, they cut off his head and used it to play “bat ball,” with their swords as bats and his head as a ball, on the grounds.’

Peshwa atrocities against the low-caste people have remained ingrained in public memory to this very day.

When the East India Company began recruiting soldiers for the Bombay Army, the untouchables seized the opportunity and enlisted. Military service was perceived as a means to opening the doors of economic as well as social emancipation. Political freedom and nationalism had little meaning for a population who had to choose between a life where the best meal on offer was a dead buffalo in the village and a life where their human dignity was respected – not to mention a decent monthly payment in cash.

While the untouchable soldiers fought on the British side against their own countrymen, the valour they showed is not at all perceived as a shameful memory today. In fact, Koregaon has become an iconic site for the former untouchables as it serves as a reminder of the bravery and strength shown by their ancestors – the very virtues that the caste system claimed they lacked. The memories related to the Koregaon memorial, help to explain how a memorial of colonial victory built in the early nineteenth century has been adapted to serve as a site that gives inspiration to the formerly untouchable people of India.

Mahars and the Military

Throughout much of the nineteenth century, the battle of Koregaon and the memorial were warmly remembered amongst military, imperial and political circles in Britain. At the beginning of the twentieth century, though, British rule was firmly established all over India, and the Koregaon Memorial faded from mainstream commemorative practices. Neither Britain at the height of colonial glory, nor India, which was beginning to receive small doses of independence, had time to commemorate the violent struggle of the days of the Honourable Company. Other lines of tradition were broken, too. The Mahar regiment had continued to demonstrate its bravery and loyalty in the battles of Kathiawad (1826) and Multan (1846). But then, in spite of the low castes’ long-standing military alliance with the British, some Sepoys from the Mahar Regiment, which formed a part of the Bombay Army, joined the “Indian Mutiny” in 1857. This added to a certain reluctance the British had always shown at the enlistment of Mahars. Subsequently, they were declared to be a non-martial race and their recruitment was stopped in May 1892.

Once their recruitment was discontinued, the Mahars soon began to feel the pinch. Gopal Baba Valangkar, a retired army-man founded a ‘Society for Removing the Problems of Non-Aryans.’ In 1894 the members of this society sent a petition to the Governor of Bombay to remind him that the Mahars had fought for the British to acquire their present dominion over India and requested a reconsideration of the decision to exclude Mahars from the Martial races, which deprived them of entry into the military service. The petition was rejected in 1896.

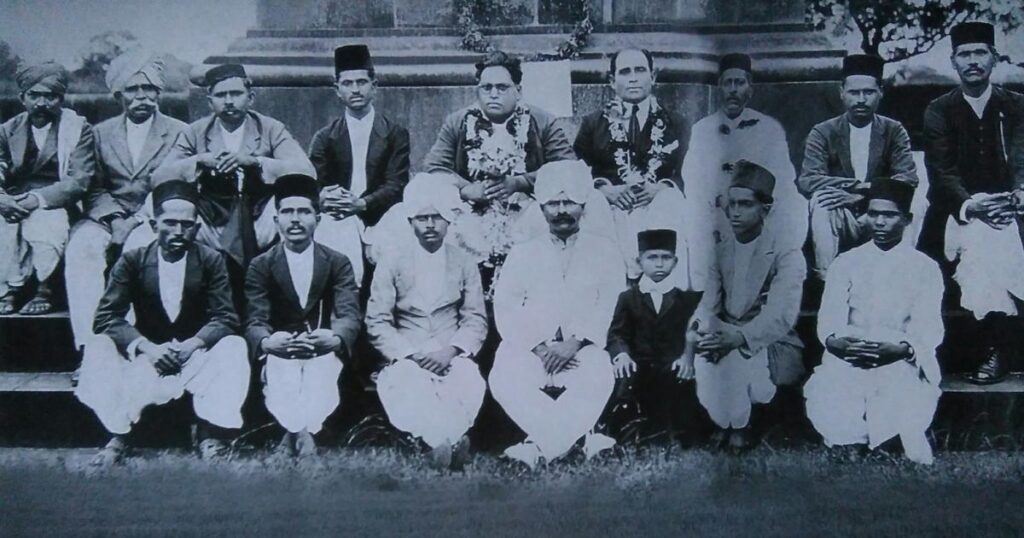

Another leader of the untouchables, Shivram Janba Kamble made an even more sustained effort to achieve the emancipation of the Untouchables. He had been involved in the work of the ‘Depressed Classes Mission’ which ran schools for untouchable children. In October 1910, R. A. Lamb of the Bombay Governor’s Executive Council was invited as the chief guest for a prize-giving ceremony in one of these schools. In his speech, Lamb mentioned his annual visits to the Koregaon Memorial. He drew attention to the ‘many names of Mahars who fell wounded or dead fighting bravely side by side with Europeans and with Indians who were not outcastes’ and regretted that ‘one avenue to honourable work had been closed to these people.’ It is not known whether it was Lamb’s speech that put the Koregaon Memorial back into the limelight or whether it had remained in living memory.

His words certainly lent weight to the argument that it was the Mahars who fought for the British and made them ‘masters of Poona.’

Within the first two decades of the twentieth century, Kamble organised a number of meetings of the Mahar people at the memorial site. In 1910, he arranged a grand Conference of the Deccan Mahars from 51 villages in Western India. The Conference sent an appeal to the Secretary of State demanding their ‘inalienable rights as British subjects from the British Government.’ They made a strong case for letting Mahars re-enter the army and argued that the Mahars were ‘not essentially inferior to any of our Indian fellow-subjects.’ Up until 1916 this request was repeated by various gatherings of untouchables in Western India. As the First World War gathered momentum, the Bombay government eventually issued orders in 1917 providing for the formation of two platoons of Mahars.

The Coming of Ambedkar

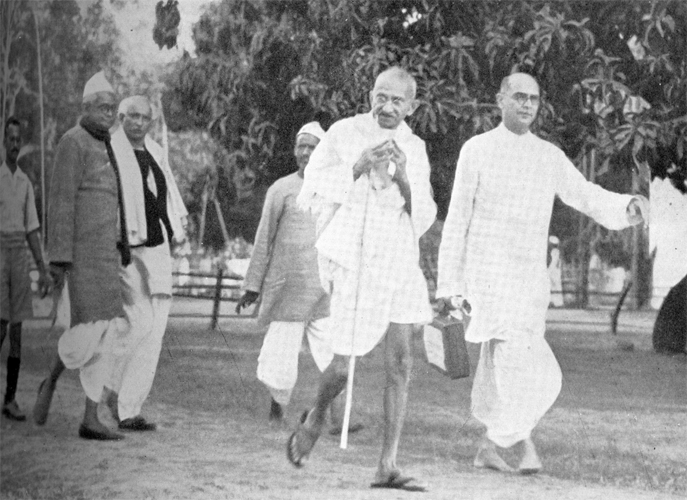

The happiness of the Mahars was, however, short-lived. Recruitment was stopped as soon as the war ended. This led to a renewed campaign for recognizing the valour of the Untouchables. By then, the demand had long since assumed the level of a movement for the general emancipation of the Untouchables. Within this campaign the Koregaon Memorial had become a focal point. Various meetings were held at the obelisk during which Kamble and other leaders invariably reminded the Untouchables of the valour and prowess exhibited by their forefathers. On the anniversary of the Koregaon battle on 1 January 1927, Kamble invited Dr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar to address the gathering of Untouchables. Ambedkar was not merely another leader of the untouchables. He was by now, as far as Indian politics was concerned, a force to be reckoned with.

Ambedkar was born in 1891, the son of a retired army subhedar from the Mahar caste. In spite of his first-hand experience of caste-based discrimination, he attained a doctorate from Columbia University, a D. Sc. from London School of Economics and was called to the Bar at Gray’s Inn by the age of 32. In 1926, he became a member of the Bombay Legislative Assembly.

He could not fail to appreciate the significance of the memorial for advancing the cause of the emancipation of the Untouchables. Not only did he make an inspiring speech at the gathering, he also supported the idea of reviving the memory of the valour of the forefathers by an annual pilgrimage to the site on the anniversary of the battle.

As a representative of the Untouchables, he was invited by the British to the Round Table Conference in 1931 where the future of the Indian Nation was to be decided. Based on his arguments at the conference, he wrote a small treatise called The Untouchables and the Pax Britannica in which he referred to the Koregaon battle to support his argument that the Untouchables had been instrumental in the establishment and consolidation of British power in India.

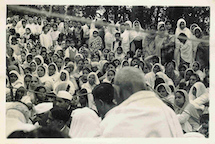

BR Ambedkar and his followers at the Koregaon victory pillar on 28 December 1927. Wikimedia Commons.

Indian mainstream politics from the 1920s until 1947 is recognised as the Gandhian era. Gandhi, having been born in the middle order caste of traders, had a different outlook on the systemic exploitation of the Untouchables on the basis of caste. He called the Untouchables Harijans, meaning people of God. Ambedkar and his followers resented both this name and the patronising attitude behind it. Underlying this surface issue, there were major ideological differences between Ambedkar and Gandhi. For the India represented by Gandhi and the Indian National Congress, the primary contradiction was that between colonial supremacy and Indians’ aspirations for political freedom. For Ambedkar and the Untouchable masses he represented, the oppression was not primarily located in the political system but arose from the socio-economic sphere. There was a clash of interests. The Indian National Congress under Gandhi sought to represent all Indians in a unified front against the colonial rule. Although Ambedkar was, unlike some “sections of Dalits and non-Brahmans who believed that colonial rule had been an unambiguous liberating force”, by no means a staunch supporter of British rule, he had quite a different new India in mind. While Gandhi saw the ideal social order arising from a reformed Hinduism, Ambedkar sought “political representation independent of the Hindu community.” In 1930, Gandhi embarked upon the Civil Disobedience Movement against the systems and institutions of the colonial rule. Kamble and a few other representatives of the depressed classes retaliated by launching what they called the “Indian National Anti-Revolutionary Party”. Its manifesto was quoted in The Bombay Chronicle:

In view of the fact that Mr Gandhi, Dictator of the Indian National Congress has declared a civil disobedience movement before doing his utmost to secure temple entry for the “depressed” classes and the complete removal of “untouchability”, it has been decided to organise the Indian National Anti-Revolutionary Party in order to persuade Gandhiji and his followers to postpone their civil disobedience agitation and to join whole-heartedly the Anti-Untouchability movement as it is… the root cause of India’s downfall…. The Party will regard British rule as absolutely necessary until the complete removal of untouchability…

Though this party did not attract much support in mainstream politics, it demonstrates that for the Untouchables, social and economic well-being was of greater and more immediate concern than political freedom, and hence colonial rule was regarded as a possibly necessary evil for the time being. It also shows that there were other and often contradictory voices in the independence movement of India. These have often been glossed over in nationalist rhetoric.

A New Memory

India won her independence in 1947, and Ambedkar chaired the committee tasked with the drafting of the new constitution. The ‘annihilation of caste’, however, remained a distant dream. The Hindu Code Bill proposed by Ambedkar in order to bring about extensive reforms in the Hindu socio-cultural scene was not accepted by parliament. In 1951 a disillusioned Ambedkar resigned from the Cabinet. Five years later, under his leadership, millions of Untouchables converted en masse to Buddhism in a step towards attaining total freedom from exploitation. The same year, after Ambedkar’s death, a political party, called the Republican Party of India, was formed to represent the interests of the low-caste people.

The conversion opened the floodgates for cultural conflicts with the high castes. The immediate reaction of the Hindu right was one of denial. The strategy of cultural appropriation that has worked so well for Hinduism from the times of the Buddha is employed even today to project the Buddhists as just another sect within Hinduism.

For the neo-Buddhists, this necessitated the creation of new and different cultural practices. Amongst the neo-Buddhists in western India one of the invented cultural practices that emerged as a result is the pilgrimage to the Koregaon Memorial. Thousands of neo-Buddhists throng to the memorial every New Year’s Day to commemorate the valour of the Mahars who helped to overthrow the high caste rule of the Peshwa. They also commemorate the visit of their leader, Dr. Ambedkar, on 1st January 1927.

Unlike any Hindu pilgrimage site, the Koregaon memorial is devoid of the tell-tale signs of a holy marketplace. No sellers of garlands and sweets and images of Gods are to be found here. It is a deserted place all through the year. However, come New Year, the place is dotted with little stalls selling books, cassettes and compact disks. Various publishers of Ambedkarite literature set up their stalls of books. Neo-Buddhist songs are played loudly in the stalls extolling the greatness of Ambedkar and emphasizing the need to change the world. Leaders of the now numerous factions of the Republican Party of India address their followers. Neo-Buddhist families visit the memorial obelisk. They offer flowers or light candles. An important part of the ritual is to offer a Vandana, a recital of verses from Buddhist texts.

An equally important element of their ritualised behaviour is the buying of books. Interviews with various booksellers have shown a surprising fact: whenever there is a gathering or a pilgrimage of the neo-Buddhists, the bookstalls do roaring business. It may be interesting to note that the average length of books sold at these stalls is short – volumes of 30-70 pages priced between 10 to 50 rupees. It might be an indication of the fact that the readers may be neo-literate, have very little time to spend on reading and can only afford cheaper books. Many publishers of related literature have indicated that their daily sales figures at the Koregaon pilgrimage and other such important pilgrimages (eg. Mumbai and Nagpur) often exceed their sales figures for the rest of the year. It could be perceived as an indication of the belief in emancipatory potential of education among the neo-Buddhists, especially of the former Mahar caste. Some of the best-selling titles include Marathi translations of books authored by Ambedkar himself, eg. Buddha and His Dhamma, Annihilation of Caste, Who Were the Shudras? Other popular books include Dalit autobiographies. They also sell Dalit poetry and small biographies of Dalit leaders.

These books offer a Dalit perspective on Indian history wherein colonial rule is portrayed as instrumental for emancipation, even though it remained ignorant of realities of caste exploitation. Jotirao Phule and Ambedkar are among the prominent Dalit writers who propounded this view of the colonial rule in which Gandhi and the movement for India’s independence do not figure very positively. The fact that Ambedkar chaired the Committee that created the Indian Constitution in 1950, however, is considered supremely important. Any attempt to criticise or seek a change in the Indian Constitution, therefore, provokes fierce opposition from the Dalit population. The anti-corruption movement led by Anna Hazare and his team in 2011 is a recent example. The extra-constitutional structure to create a powerful ombudsman (Lokpal) for resolving the issues of corruption was not welcomed by Dalit leaders and public.

The Importance of Forgetting

Though the Koregaon Memorial was constructed by the Colonial rulers, it does not feature on the commemorative landscape of today’s British public. This amnesia might be attributed to the fact that the colonial memories, especially of violent battles are no longer the object of pride in present-day Britain. This amnesia is matched by the high castes in India. Poona, the capital of Peshwas has become a software and education city called Pune. When a sample of 130 members of the high caste, newly rich people (who have come to be nicknamed as Computer Coolies) were asked about the Koregaon memorial, none of them knew what it was.

Elite amnesia is not total, though. There are also, what may be called conflicting memories. During the 1970s the Western Indian state of Maharashtra witnessed a spate of popular (a)historical novels topping the best-seller lists in Marathi. Many of them dominate the historical understanding and perceptions of the Marathi-speaking middle classes even today. Two important novels from this genre, both authored by Brahmins, describe the battle of Koregaon in passing. Mantravegla by N. S. Inamdar is based on the life of the Last Peshwa. It claims that the battle was, in fact, won by the Peshwas. Recently, this trend of creating alternative memories about the Peshwa battles has become even stronger. The battle of Panipat, which saw a complete defeat of the Peshwa armies in 1761, is commemorated today by high-sounding rallies. The kind of rhetoric used during these rallies suggests that it was the Peshwa who won the battle.

The Koregaon Memorial occupies a very significant place in today’s neo-Buddhist culture. The internet and other electronic media are used to document and commemorate the Koregaon battle and Ambedkar’s visit to it. An image search for Koregaon Pillar yields hundreds of digital pictures of the Memorial Obelisk. Film clips are available on Youtube. At least a dozen blogs in English and Marathi have entries related to the Koregaon memorial. They describe the battle and the role of the Mahar soldiers and also remind the readers about what the Untouchables could achieve if they show the resolve.

Conclusion

The obelisk of Koregaon Bheema is thus a site which has generated conflicting memories. These memories represent the divergent interests of the groups involved in their creation. Those wishing to commemorate the greatness of the Peshwa rule – the symbol of high caste supremacy – either choose to ignore the Koregaon battle, or create a Pseudomnesia of Peshwa victory. While the obelisk marks an imperial site of memory that is largely forgotten in the homeland of the empire, the monument has undergone a metamorphosis of commemoration in Western India.

It no longer reminds the public of imperial power, but for the former Untouchables whose forefathers fought at Koregaon it serves the purpose of providing “historical evidence” of the ability of the Untouchables to overthrow the high caste oppression.

Considering the fact that Indian society is still dominated by the system of caste hierarchy, the Koregaon Memorial is also a reminder that present-day contestation for hegemony is often manifested in contesting memories.

This paper has been carried out courtesy with the permission of Shraddha Kumbhojkar. It has been presented without its abstract, citations, footnotes and bibliography for purposes of easier reading.

The paper has also been published in Sites of Imperial Memory, (ed.) Dominik Geppert, Frank Lorenz Muller, Manchester University Press, Manchester, New York, 2015. as Politics, Caste and the remembrance of the Raj: the Obelisk at Koregaon. You can buy the book here.

ARCHIVE

The Diary of Mahadev Desai

March 10, 1932

I had not the faintest idea that such a day as this would dawn for me. But I did once dream in Nasik prison that I was all of a sudden taken to Bapu in Yeravda prison and that I fell at his feet, crying all the while and unable to check my tears.

Roche came to me in the morning and said, “You are being transferred from here; you get ready in one hour.” I asked him, “Where will they take me?” He replied, “You will be happy and thankful when you know it but I must not say a word.” I asked to meet Dr. Chandulal Desai but my request was turned down. We left Nasik at nine. The policemen who escorted me were the same as had a few days ago accompanied Vitthalbhai here. One of them turned out to be an old acquaintance of the days when Bapu saw Lord Reading. He remembered the date correctly — June 17, 1921. He was then a bearer to Sir Charles Innes. He had subsequently served elsewhere and was now in the police.

When Akbar Ali embraced me with tearful eyes and told me from his closed cell about his prayerful wish that I should be kept with Gandhiji, I said, “You may pray for me, but can I be so lucky as that?” He replied, “True, but I can only hope and pray.” What stories had I heard about Akbar Ali! But he showered his affection on me, and his prayers bore fruit. Pyarelal used to tell everybody at Nasik that they had fixed this up with Martin. This was also true though I regarded it as a mere joke.

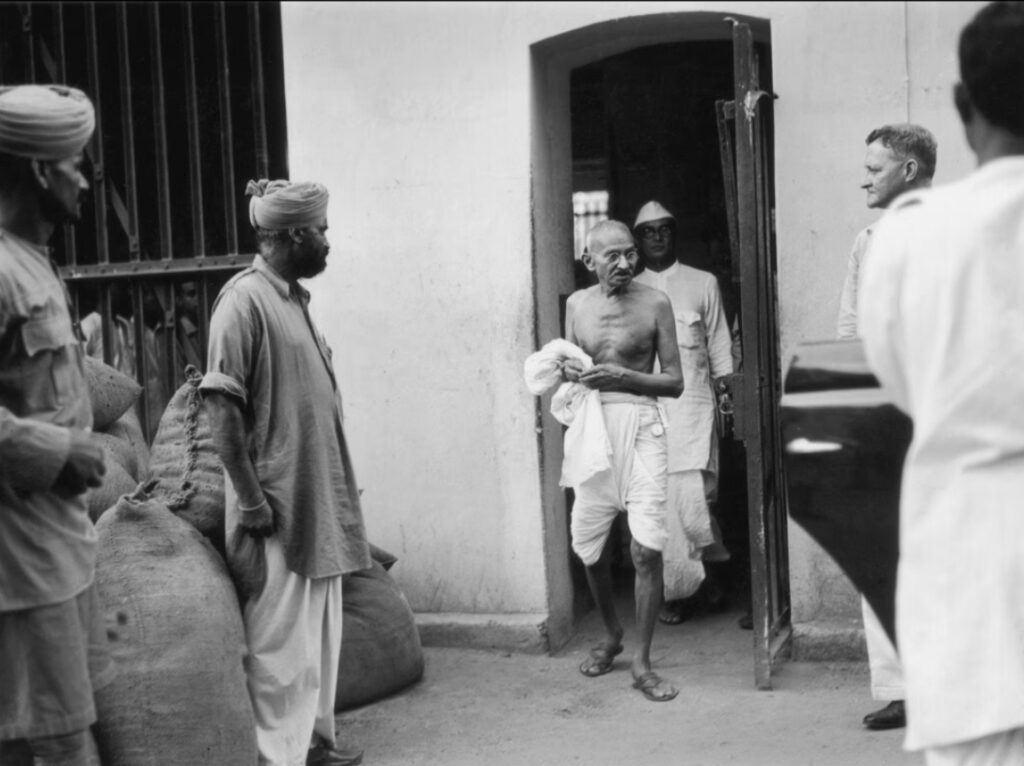

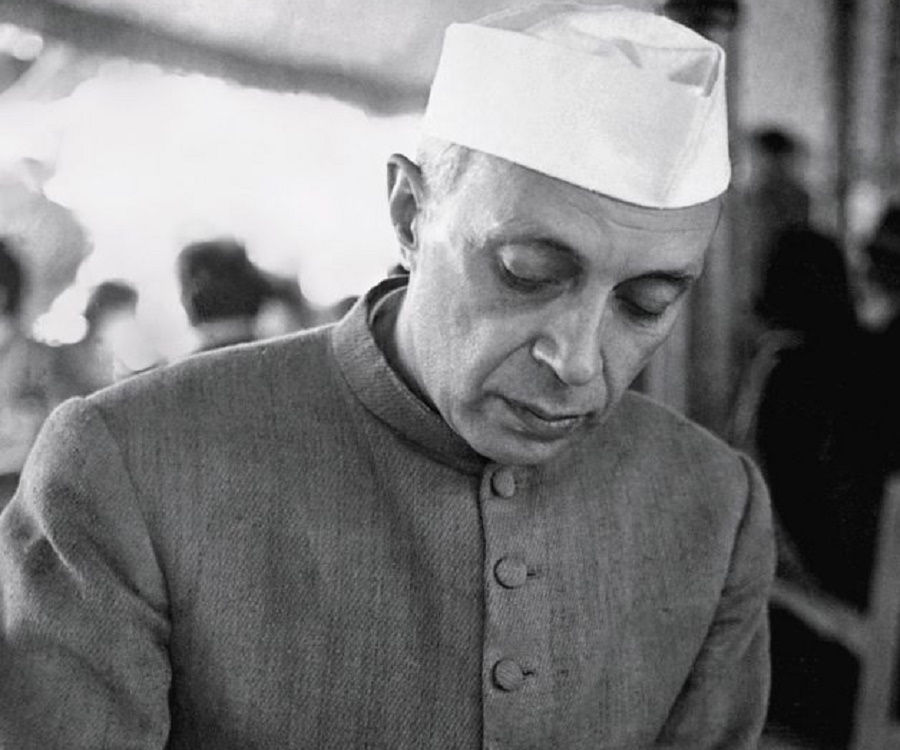

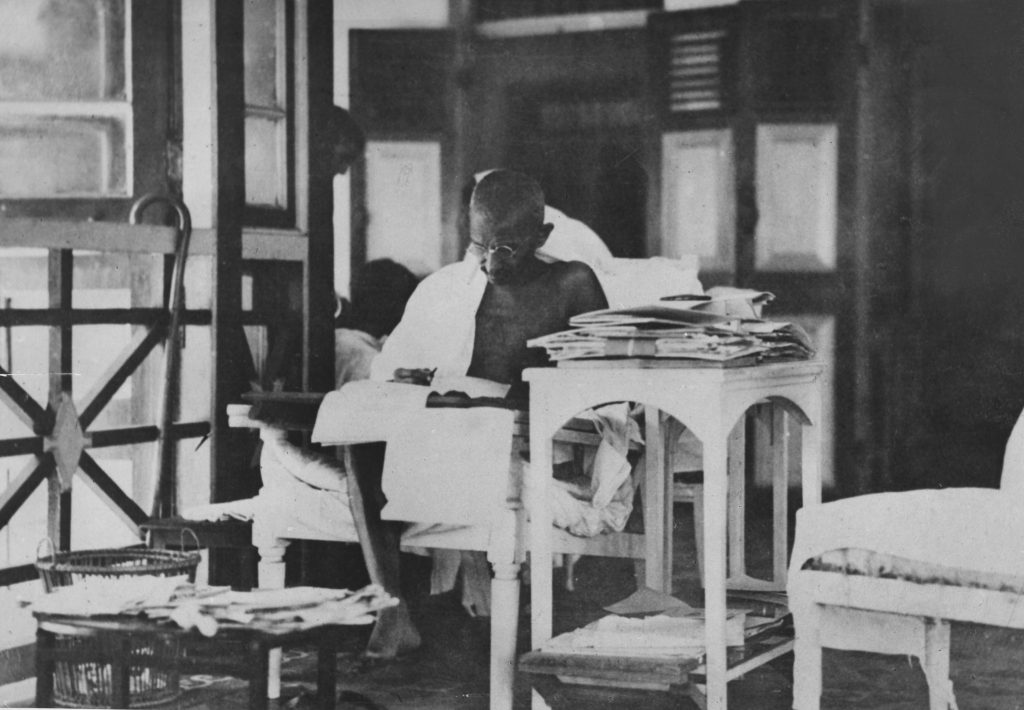

Gandhi in jail

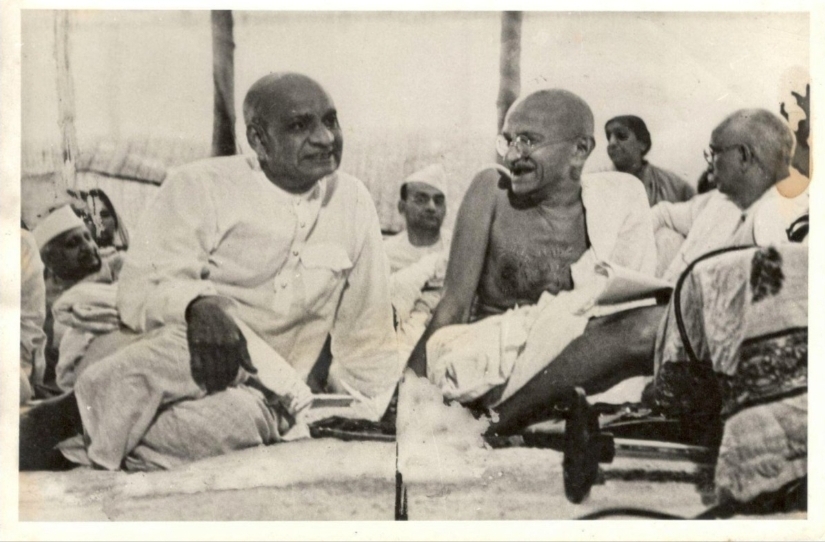

I was received rather coldly at Yeravda prison and I feared they just wanted to get rid of me at Nasik, without keeping me in Bapu’s company here. Then came Kateli, smiling, and asked me to go with him. He was informed at four in the morning that I was to be kept with Gandhiji. Bapu too was surprised when I placed my head at his feet. He patted me on the back, the head and the cheeks more fondly than ever before. I felt deeply grateful but was overwhelmed by a sense of my unworthiness. Later I learnt from Bapu and the Sardar that Shri Purushottamdas also had a hand in bringing me to Yeravda. Last time Dahyabhai did say that — had done the needful.

Bapu too was surprised when I placed my head at his feet. He patted me on the back, the head and the cheeks more fondly than ever before. I felt deeply grateful but was overwhelmed by a sense of my unworthiness.

After some rambling talk, Bapu said, “You have come at the right moment, for Vallabhbhai is at his wit’s end. Did he tell you about it?” Vallabhbhai suggested that I should eat something before we started our discussions. He brought me food — bread, butter, curds and boiled sweet potatoes. He and Bapu had already finished their meals. When I finished, Bapu gave me his letter to Sir Samuel Hoare and asked me what I thought of it.

I said, “I find the reasoning sound. I have often felt about the repression that one need not be surprised if some day it leads Bapu thus to voice his indignation. Why does Vallabhbhai object? Is it because as President of Congress, he finds himself unable to endorse this step of yours?”

Bapu said, “No, he is not worried on that account. He doubts if he can give his consent as a co-worker. But I have never imagined Vallabhbhai looking at things from a religious viewpoint. It is only to be expected that he should look at this from the political angle. My relations with Vallabhbhai are not on a religious basis, as they are with you. Vallabhbhai is afraid that I shall lay myself open to misinterpretation. The Government will say: ‘Gandhi has always been a man of this type. He has gone mad; Let him alone with his madness.’ And Vallabhbhai also thinks the people will be shocked, and then again there is the grave danger of such fasts being imitated in the wrong spirit. But that does not matter. What if I am taken for a mad man and die? That would be the end of my mahatmaship, if it is false and undeserved. Friends like Remain Rolland will understand my standpoint. But even if they don’t, I should be concerned only with my duty as a man of religion.”

I said, “The world can understand fast as a protest against repression but not perhaps on the question of Harijan representation. The British will try to mislead the world into believing that most if not all Harijans favour separate electorates. I should also suggest you make it clearer how the separate electorates are intended to strike a blow at the body politic. I am pretty sure, however, that even honest Britons will fail to see how.”

Gandhi with Mahadev Desai

Bapu said, “If we tried to make this clearer, we would have to describe the Muslims’ share in this sordid business. And that would increase Hindu-Muslim tension. This would be very much like what happened in connection with the earlier twenty-one days’ fast when Mahomed Ali got a few sentences in my statement scored out.”

I said, “Some will ask if this really was a sin more heinous than that committed by the Hindus so that you felt yourself compelled to undertake a fast.”

“Some will ask if this really was a sin more heinous than that committed by the Hindus so that you felt yourself compelled to undertake a fast.”

Bapu said, “We have been trying to make Hindu society repent of its sin. But the separate electorates are meant to perpetuate the sin or to make it impossible for the Hindus to repent. They will end in nothing but a civil war between the caste Hindus and Harijans, and between Hindus and Muslims.”

Vallabhbhai said, “I am unconvinced of the rightness of your move, but now you are free to do what you think is right.”

Bapu corrected the letter and went to bed. But I did not sleep till after midnight.

We got up at a quarter to four for the morning prayers. We had a wash and as we gathered together, Bapu gave the programme: “Vallabhbhai recites the shlokas (stanzas). He has little knowledge of Sanskrit and his pronunciation is bad. So I thought this was the only way it could be improved. You will find that he has made considerable progress. I sing the hymn, but not from memory. So we read one hymn after another from the Ashram hymnal. We thought we would start with the Marathi section today. But now that you are here, you will lead us in singing the hymn and in “Ramadhun”. I requested Bapu to lead us in Ramadhun. This discussion we had had at night. My first hymn was Prabhu mere etc., ‘O God, do not mind my heavy load of sin.’ What else could I have sung?

March 30, 1932

This morning we happened to talk about a certain Muslim leader. Vallabhbhai said, “He too took a narrow communal view in time of crisis and asked for a separate relief fund for Muslims and a separate appeal for it.” Bapu said, “He is not at fault on that score. What is he to do if we create such an environment for him? What amenities do we offer Muslims? They are mostly treated like untouchables. If I wished to send Amtul Salam to Devlali, could I ask — to put her up? The fact is that we should not go to the Bhatia sanatorium or for that matter any other place which excludes Amtul or any one else. Indeed it is up to the Hindus to take a step forward. As it is, the bitterness is increasing. It can be mitigated only if the Hindus wake up and break down the barriers they have erected. Perhaps the barriers were needed at a certain time, but now there is no earthly use for them.” Vallabhbhai said, “But the manners and customs of Muslims are different. They take meat while we are vegetarians. How are we to live with them in the same place?” Bapu replied, “No, sir. Hindus as a body are nowhere vegetarians except in Gujarat. Almost every Hindu takes meat in the Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Sindh. . . . All at present are on their trial. Let us wait and see, with faith that all will be well in the end.”

What is he to do if we create such an environment for him? What amenities do we offer Muslims? They are mostly treated like untouchables.

The Civil Surgeon examined Bapu, and placing the stethoscope on his chest said, “I would be proud to possess a heart like that.” So saying he passed on to other prisoners. Bapu did not tell him about the pain in his fingers. He examined my leg but had no treatment to suggest. It seemed as if he wanted to finish an unpleasant task somehow or other. No other Civil Surgeon went away like this without wanting to have a word with Bapu. This one is capable of amazing self-restraint.

Gandhi and Patel

Sir John Anderson has come with testimonials from all. I showed to Bapu Laski’s remarks about him. Bapu said, “Perhaps that is true. If so he will capture Bengali hearts, win over Subhas Bose and Sengupta and disregard Congress. The same fate is perhaps in store for the Punjab. I do not think there will be peace in all parts of India at the same time. I imagine they will pacify one province after another.”

Bapu compelled me to sleep in the open from today and asked the Major for a cot for me.

The Major said, “Thirty or forty women prisoners all want to write to you. What shall I do about it? Would it not do if they just sent you their signatures ?” Bapu replied, “If you wish, I will ask them to be satisfied with writing only a couple of lines each. Why deprive them of this satisfaction? They are all so gentle.”

April 1, 1932

… We happened to talk about Ambedkar. Bapu said, “Till I went to England, I did not know that he was a Harijan. I thought he was some Brahman who took deep interest in Harijans and therefore talked intemperately.” Vallabhbhai said he knew he was a Harijan, as he had made his acquaintance when the Harijan leader toured Gujarat with Thakkar. Then we turned to Thakkar Bapa and the Servants of India Society’s attitude to Harijans.

“Till I went to England, I did not know that he was a Harijan. I thought he was some Brahman who took deep interest in Harijans and therefore talked intemperately.”

Bapu said, “Their attitude is responsible for the shape that question has assumed nowadays. I noticed this when I lived in the Poona home of the Society in 1915 after the death of Gokhale. I asked Devadhar for a brief note on their activities, so that I would see what I could do. This note advised that we should deliver speeches before Harijan meetings, and create in them a consciousness of the injustice done to them by Hindu society. I said to Devadhar, ‘Here you give me a stone when I asked you for bread. We cannot serve Harijans in this fashion. It is not service, but patronage pure and simple. Who are we to uplift Harijans? We can only atone for our sin against them or discharge the debt we owe to them, and this we can do only by adopting them as equal members of society, and not by haranguing them.’ At this Sastri was taken aback and said, ‘ We did not expect that you would speak in such a magisterial tone.’ And Hari Narayan Apte was very angry. I said to him, ‘I am afraid you will make Harijans rise in rebellion against society.’ Apte replied, ‘Yes, let there be a rebellion. That is just what I want.’ In this way there was a lot of discussion, so that the next day I said to Sastri, Devadhar, Apte and others that I had no idea I would cause them pain. This apology left a good impression on their minds. And afterwards we pulled on well together.” Vallabhbhai said, “You can work in harmony with everybody. It does not cost you any effort. Vaniks (merchants) do not mind humbling themselves.”

Who are we to uplift Harijans? We can only atone for our sin against them or discharge the debt we owe to them, and this we can do only by adopting them as equal members of society, and not by haranguing them.

August 17, 1932

The communal decision was published today. Bapu went about his work till the evening as if nothing had happened. He asked me to prepare a hajra cake and ate it with relish. Almond butter was made with the help of the machine. As we were taking the usual evening walk, he read Horniman’s article and liked it. In the course of conversation in the morning he said: ‘The decision only confirms the minorities’ pact. Everything has gone according to the plan in Benthall’s letter.’

I said the new constitution was worse than the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms. “Certainly,” replied Bapu. “Those reforms were based on the Lucknow agreement between Congress and the Muslim League. But this constitution seeks to create such divisions in the country that it can never again stand up on its own legs.” Just before the evening prayer he said to me, “Well, you and the Sardar think over the situation and tell me whatever you feel like saying. The letter to Samuel Hoare details the steps I should take in order to deal with the present situation. I have therefore to serve the British Government with a notice.” I was taken aback and said nothing. The Sardar also had a similar feeling. I sang Surdas’s hymn and began to read the Ashram post.

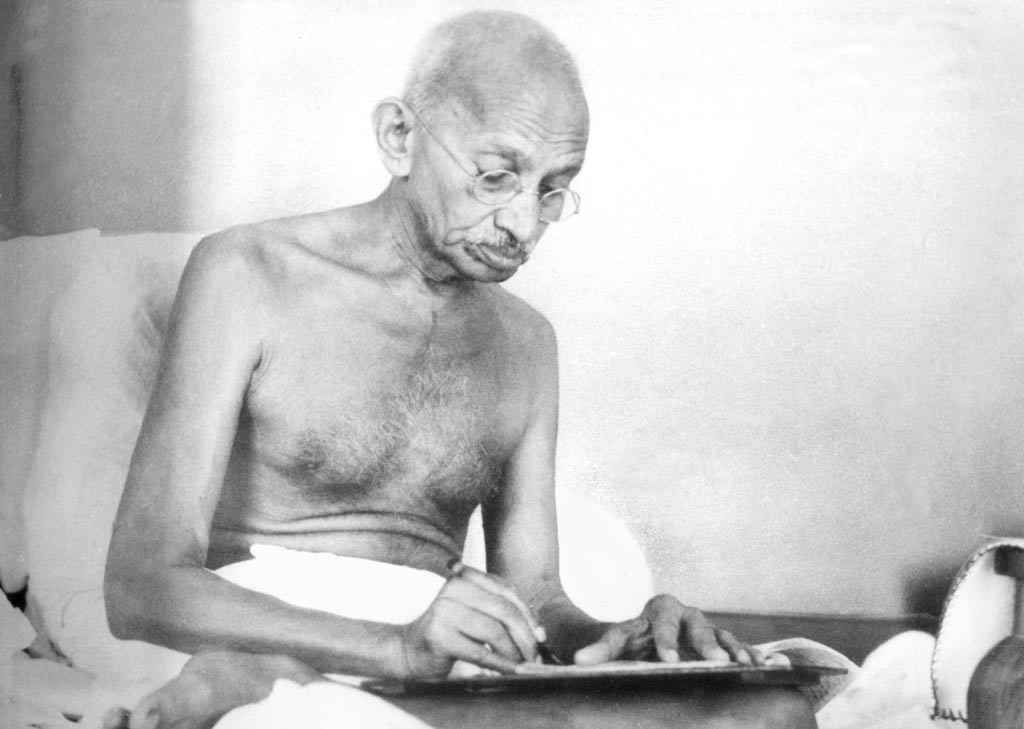

The letters which had to be written were written at once, and then Bapu began to write the letter to MacDonald.

August 18, 1932

After finishing it in the morning Bapu said, “You stop spinning for a while and go through this letter so that it may be sent at once.” The Sardar and I read it. Then he said, ‘There is no reference in the letter to other parts of the decision. May not this be misinterpreted to mean that they are approved by you?” “No,” replied Bapu. “My views are well-known. Still if you wish, I will insert one paragraph, although I would then have to enter into argument. In this letter I propose to leave out all argument, this having been included in the letter to Samuel Hoare.” I suggested that Bapu should only say his soul rebelled against the decision as a whole, but part of it was so vicious that he would lay down his life in the attempt to get it annulled. “No,” said Bapu. “No such comparison may fairly be instituted. If it were, they would say that I wanted to get the decision annulled in its entirety and had seized upon a certain part of it as a pretext. I do want the whole decision to go. But at night I thought for a moment over the question whether other points should be included and decided against their inclusion.”

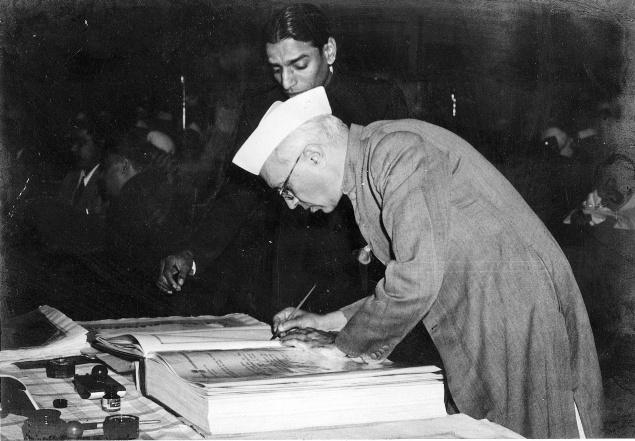

Gandhi writing a letter

The same subject was discussed in the evening. Bapu observed, “I cannot put in other things at all, for that would be tantamount to mixing politics with religion. The two questions are in fact distinct from each other.” He then continued, “I have rehearsed everything in my own mind. Everything you have suggested was considered by me before I reached the decision. Separate electorates for the Muslims and the rest are fraught with danger. They will combine with the British to suppress the Hindus. But I can think of methods by which the combination can be dealt with. When once the outsider who foments quarrels is gone, we can tackle our problems with success. But as regards the so-called untouchables I have no other remedy. How possibly am I to explain things to these poor fellows? To draw suffering on oneself when misfortune dogs one’s footsteps is no novelty. How did Sudhanva fall into the pan full of hot oil and how did Prahlad embrace a pillar of red-hot iron? There will be many Satyagraha movements even after the attainment of Swaraj. I have often had the idea that after the establishment of Swaraj I should go to Calcutta and try to stop animal sacrifice offered in the name of religion. The goats at Kalighat are worse off even than untouchables. They cannot attack men with their horns. They can never throw up an Ambedkar from their midst. My blood boils when I think of such violence. Why do they not offer tigers instead of goats?”

“Separate electorates for the Muslims and the rest are fraught with danger. They will combine with the British to suppress the Hindus. But I can think of methods by which the combination can be dealt with. When once the outsider who foments quarrels is gone, we can tackle our problems with success. But as regards the so-called untouchables I have no other remedy.”

In the morning we discussed the possible repercussions of Bapu’s step. I said, “It will be misinterpreted in a variety of ways. Here in India there will be senseless imitation of it while in America they will say Gandhi obtained his release by his fast.” “I know,” replied Bapu. “In America they will swallow anything, and there are British agents ready to help them to do so. Many will even say that I am now a bankrupt, that my spirituality is not paying dividends; therefore, I committed suicide like cunning insolvents. And in this country there will be blind imitation, and misinterpretation. The Government will perhaps release me and let me die outside prison, or perhaps they will let me die in jail, as in the case of MacSwiney. Our own men will be critical. Jawaharlal will not like it at all. He will say we have had enough of such religion. But that does not matter. When I am going to wield a most powerful weapon in my spiritual armoury, misinterpretation and the like may never act as a check.”

ARCHIVE

At Benares Hindu University (Benares, February, 1916)

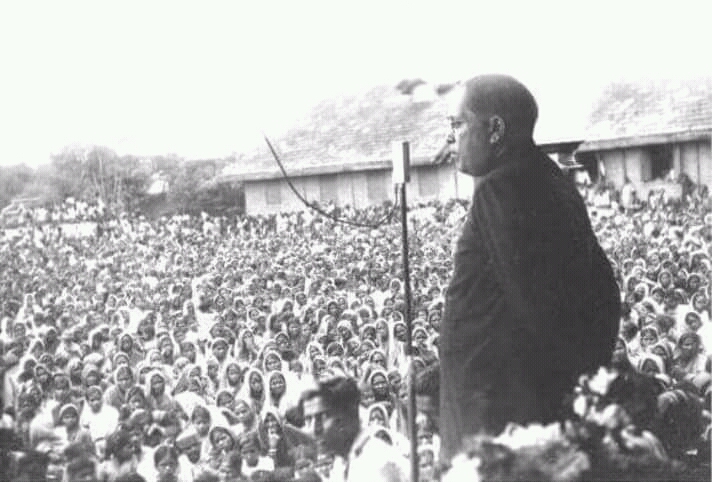

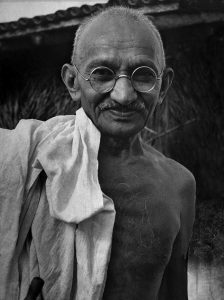

MOHANDAS KARAMCHAND GANDHI

Mahatma Gandhi

I wish to tender my humble apology for the long delay that took place before I was able to reach this place. And you will readily accept the apology when I tell you that I am not responsible for the delay nor is any human agency responsible for it. The fact is that I am like an animal on show, and my keepers in their over kindness always manage to neglect a necessary chapter in this life, and, that is, pure accident. In this case, they did not provide for the series of accidents that happened to us—to me, keepers, and my carriers. Hence this delay.

Friends, under the influence of the matchless eloquence of Mrs Besant who has just sat down, pray, do not believe that our University has become a finished product, and that all the young men who are to come to the University, that has yet to rise and come into existence, have also come and returned from it finished citizens of a great empire. Do not go away with any such impression, and if you, the student world to which my remarks are supposed to be addressed this evening, consider for one moment that the spiritual life, for which this country is noted and for which this country has no rival, can be transmitted through the lip, pray, believe me, you are wrong. You will never be able merely through the lip, to give the message that India, I hope, will one day deliver to the world. I myself have been fed up with speeches and lectures. I accept the lectures that have been delivered here during the last two days from this category, because they are necessary. But I do venture to suggest to you that we have now reached almost the end of our resources in speech-making; it is not enough that our ears are feasted, that our eyes are feasted, but it is necessary that our hearts have got to be touched and that our hands and feet have got to be moved.

We have been told during the last two days how necessary it is, if we are to retain our hold upon the simplicity of Indian character, that our hands and feet should move in unison with our hearts. But this is only by way of preface. I wanted to say it is a matter of deep humiliation and shame for us that I am compelled this evening under the shadow of this great college, in this sacred city, to address my countrymen in a language that is foreign to me. I know that if I was appointed an examiner, to examine all those who have been attending during these two days this series of lectures, most of those who might be examined upon these lectures would fail. And why? Because they have not been touched.

I wanted to say it is a matter of deep humiliation and shame for us that I am compelled this evening under the shadow of this great college, in this sacred city, to address my countrymen in a language that is foreign to me. I know that if I was appointed an examiner, to examine all those who have been attending during these two days this series of lectures, most of those who might be examined upon these lectures would fail. And why? Because they have not been touched.

I was present at the sessions of the great Congress in the month of December. There was a much vaster audience, and will you believe me when I tell you that the only speeches that touched the huge audience in Bombay were the speeches that were delivered in Hindustani? In Bombay, mind you, not in Benaras where everybody speaks Hindi. But between the vernaculars of the Bombay Presidency on the one hand and Hindi on the other, no such great dividing line exists as there does between English and the sister language of India; and the Congress audience was better able to follow the speakers in Hindi. I am hoping that this University will see to it that the youths who come to it will receive their instruction through the medium of their vernaculars. Our languages are the reflection of ourselves, and if you tell me that our languages are too poor to express the best thought, then say that the sooner we are wiped out of existence the better for us. Is there a man who dreams that English can ever become the national language of India? Why this handicap on the nation? Just consider for one moment what an equal race our lads have to run with every English lad.

I had the privilege of a close conversation with some Poona professors. They assured me that every Indian youth, because he reached his knowledge through the English language, lost at least six precious years of life. Multiply that by the numbers of students turned out by our schools and colleges, and find out for yourselves how many thousand years have been lost to the nation. The charge against us is that we have no initiative. How can we have any, if we are to devote the precious years of our life to the mastery of a foreign tongue? We fail in this attempt also. Was it possible for any speaker yesterday and today to impress his audience as was possible for Mr Higginbotham? It was not the fault of the previous speakers that they could not engage the audience. They had more than substance enough for us in their addresses. But their addresses could not go home to us. I have heard it said that after all it is English educated India which is leading and which is doing all the things for the nation. It would be monstrous if it were otherwise. The only education we receive is English education. Surely we must show something for it. But suppose that we had been receiving during the past fifty years’ education through our vernaculars, what should we have today? We should have today a free India, we should have our educated men, not as if they were foreigners in their own land but speaking to the heart of the nation; they would be working amongst the poorest of the poor, and whatever they would have gained during these fifty years would be a heritage for the nation. Today even our wives are not the sharers in our best thought. Look at Professor Bose and Professor Ray and their brilliant researches. Is it not a shame that their researches are not the common property of the masses?

I have heard it said that after all it is English educated India which is leading and which is doing all the things for the nation. It would be monstrous if it were otherwise. The only education we receive is English education. Surely we must show something for it. But suppose that we had been receiving during the past fifty years’ education through our vernaculars, what should we have today? We should have today a free India, we should have our educated men, not as if they were foreigners in their own land but speaking to the heart of the nation; they would be working amongst the poorest of the poor, and whatever they would have gained during these fifty years would be a heritage for the nation.

Let us now turn to another subject.

The Congress has passed a resolution about self-government, and I have no doubt that the All-India Congress Committee and the Muslim League will do their duty and come forward with some tangible suggestions. But I, for one, must frankly confess that I am not so much interested in what they will be able to produce as I am interested in anything that the student world is going to produce or the masses are going to produce. No paper contribution will ever give us self-government. No amount of speeches will ever make us fit for self-government. It is only our conduct that will make us fit for it. And how are we trying to govern ourselves?

I want to think audibly this evening. I do not want to make a speech and if you find me this evening speaking without reserve, pray, consider that you are only sharing the thoughts of a man who allows himself to think audibly, and if you think that I seem to transgress the limits that courtesy imposes upon me, pardon me for the liberty I may be taking. I visited the Vishwanath temple last evening, and as I was walking through those lanes, these were the thoughts that touched me. If a stranger dropped from above on to this great temple, and he had to consider what we as Hindus were, would he not be justified in condemning us? Is not this great temple a reflection of our own character? I speak feelingly, as a Hindu. Is it right that the lanes of our sacred temple should be as dirty as they are? The houses round about are built anyhow. The lanes are tortuous and narrow. If even our temples are not models of roominess and cleanliness, what can our self-government be? Shall our temples be abodes of holiness, cleanliness and peace as soon as the English have retired from India, either of their own pleasure or by compulsion, bag and baggage?

I entirely agree with the President of the Congress that before we think of self-government, we shall have to do the necessary plodding. In every city there are two divisions, the cantonment and the city proper. The city mostly is a stinking den. But we are a people unused to city life. But if we want city life, we cannot reproduce the easy-going hamlet life. It is not comforting to think that people walk about the streets of Indian Bombay under the perpetual fear of dwellers in the storeyed building spitting upon them. I do a great deal of railway travelling. I observe the difficulty of third-class passengers. But the railway administration is by no means to blame for all their hard lot.

We do not know the elementary laws of cleanliness. We spit anywhere on the carriage floor, irrespective of the thoughts that it is often used as sleeping space. We do not trouble ourselves as to how we use it; the result is indescribable filth in the compartment. The so-called better class passengers overawe their less fortunate brethren. Among them I have seen the student world also; sometimes they behave no better. They can speak English and they have worn Norfolk jackets and, therefore, claim the right to force their way in and command seating accommodation.

We do not know the elementary laws of cleanliness. We spit anywhere on the carriage floor, irrespective of the thoughts that it is often used as sleeping space. We do not trouble ourselves as to how we use it; the result is indescribable filth in the compartment. The so-called better class passengers overawe their less fortunate brethren.

I have turned the searchlight all over, and as you have given me the privilege of speaking to you, I am laying my heart bare. Surely we must set these things right in our progress towards self-government. I now introduce you to another scene. His Highness the Maharaja who presided yesterday over our deliberations spoke about the poverty of India. Other speakers laid great stress upon it. But what did we witness in the great pandal in which the foundation ceremony was performed by the Viceroy? Certainly a most gorgeous show, an exhibition of jewellery, which made a splendid feast for the eyes of the greatest jeweler who chose to come from Paris. I compare with the richly bedecked noble men the millions of the poor. And I feel like saying to these noble men, ‘There is no salvation for India unless you strip yourselves of this jewellery and hold it in trust for your countrymen in India.’ I am sure it is not the desire of the King-Emperor or Lord Hardinge that in order to show the truest loyalty to our King-Emperor, it is necessary for us to ransack our jewellery boxes and to appear bedecked from top to toe. I would undertake, at the peril of my life, to bring to you a message from King George himself that he accepts nothing of the kind.

Sir, whenever I hear of a great palace rising in any great city of India, be it in British India or be it in India which is ruled by our great chiefs, I become jealous at once, and say, ‘Oh, it is the money that has come from the agriculturists.’ Over seventy-five percent of the population are agriculturists and Mr Higginbotham told us last night in his own felicitous language, that they are the men who grow two blades of grass in the place of one. But there cannot be much spirit of self-government about us, if we take away or allow others to take away from them almost the whole of the results of their labour. Our salvation can only come through the farmer. Neither the lawyers, nor the doctors, nor the rich landlords are going to secure it.

Now, last but not the least, it is my bounden duty to refer to what agitated our minds during these two or three days. All of us have had many anxious moments while the Viceroy was going through the streets of Benares. There were detectives stationed in many places. We were horrified. We asked ourselves, ‘Why this distrust?’ Is it not better that even Lord Hardinge should die than live a living death? But a representative of a mighty sovereign may not. He might find it necessary to impose these detectives on us? We may foam, we may fret, we may resent, but let us not forget that India of today in her impatience has produced an army of anarchists. I myself am an anarchist, but of another type. But there is a class of anarchists amongst us, and if I was able to reach this class, I would say to them that their anarchism has no room in India, if India is to conquer the conqueror. It is a sign of fear. If we trust and fear God, we shall have to fear no one, not the maharajas, not the viceroys, not the detectives, not even King George.

I myself am an anarchist, but of another type. But there is a class of anarchists amongst us, and if I was able to reach this class, I would say to them that their anarchism has no room in India, if India is to conquer the conqueror. It is a sign of fear. If we trust and fear God, we shall have to fear no one, not the maharajas, not the viceroys, not the detectives, not even King George.