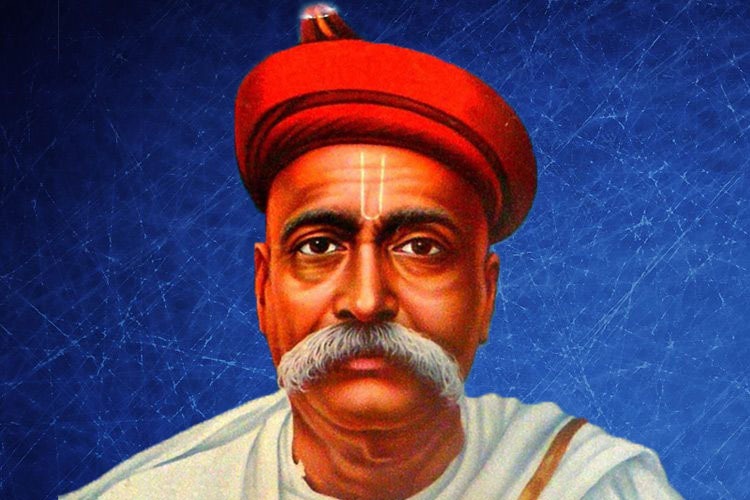

History is complex, but rarely do you come upon a point in history with as many angles to it as we uncovered when we came upon a record in the Indian Law Reports (Criminal) of Queen Empress V. Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Keshav Mahadev Bal in 1897— India’s first ‘sedition’ conviction.

We were looking for something from a time like the one we are experiencing now, when the nation was facing a public health crisis. Tilak’s trial and conviction was a consequence of such a crisis and the government’s mishandling of it.

But, as mentioned, a sedition conviction (an upshot of the ridiculous interpretation of sedition by the judge Sir Arthur Strachey) is merely one of the many sides to this historical event. Besides that there is Tilak’s social conservatism and the Hindu Nationalist angle, the question of violence as a legitimate tool against oppression and, finally, the transformation of the courtroom and jail into emblems of national discontent.

But first, the context.

The Bubonic Plague came to Bombay in 1896, and spread inland. Authorities conducted surprise checks in people’s homes to find those who may be infected and take them away for quarantine or treatment. Many Indians were afraid of going to hospitals or quarantine camps and did everything they could to prevent this. As noted by Abhinav Chandrachud (advocate and author of Republic of Religion: The Rise and Fall of Colonial Secularism in India, who has studied this period), records indicate that the manner in which such checks were conducted caused great unrest. In Poona, the army was responsible for these checks and was accused of disrespecting the modesty of women, removing and destroying people’s possessions and intruding into kitchens and personal spaces of worship in homes. According to Narasimhan Kelkar (writer and historian from those days), “Either through ignorance or impudence, they would mock, indulge in monkey tricks, talk foolishly, intimidate, touch innocent people, shove them, enter any place without justification, pocket valuable items, etc.”

It was in such an atmosphere, on the 15th of June, 1897, that Tilak published in the Kesari – a Marathi weekly he ran and edited – two articles, among others.

The articles can be read in the law report linked at the end, from page 112, the second page of the report of the case. They had been translated for the trial by an “oriental translator”, appointed by the government, and so these translations must be read keeping this fact in mind.

The first is in the form of a poem titled ‘Shivaji’s Utterances and signed “Mark of the Bhawani Sword”. In it, Shivaji awakens from his slumber in the heavens (“I was asleep: why then did you, my darlings, awaken me?”) to launch into a fiery tirade at what the British have reduced his countrymen to. It is written, at least partly, in metre, and uses vigorous metaphor (“Foreigners are dragging out Lakshmi violently by the hand by means of persecution”- the word used originally was ‘kara’, which could have meant ‘by hand’ or ‘taxes’, hence pointing to the unfair taxes imposed on Indian earnings). Shivaji goes on to decry the flight of health from the lives of people. Also that: “The wicked Akabaya (misfortune) stalks with famine through the whole country.” The article then takes a few conservative and traditionalist – some may even say reactionary – turns. Shivaji denounces the incarceration of brahmins and the slaughter of cows, turns to the issue of women being assaulted (“opportunities are availed of at railway carriages and women are dragged by the hand” – conceivably referring to plague inspections at railway stations), then again to the mishandling of “royal families”. It ends with rebuking the British for their misrule and reminding them of the time when they were but merchants visiting India: “How have you forgotten that old way of yours, when with scales in hand you used to sell (your goods) in (your) warehouses? (As) my expeditions in that direction were frequent, it was at that time possible (for me) to drive you back to (your own) country. The Hindus, however, being magnanimous by nature, I protected you.” Shivaji then asks the British to return the favour by taking care of his people (“my own children”) and making them “happy”.

The second article is a report on three days of the Shri Shivaji Coronation Festival in Poona, which hosted a gamut of events from readings and philosophical commentary on the Mahabharata to Kirtans to athletic sports, including a Malkhamb display. A good deal of text is devoted to reporting the refutation by scholars during the festival – with presentations of sources, argument and zeal – of a colonial interpretation of Shivaji’s killing of Afzal Khan. Towards the end comes the account of a speech of the president of the festival, Tilak himself, who took the question of the ethicality of Shivaji’s killing of Afzal Khan beyond “historical researches”. “The laws which bind society are for common men like yourself and myself,” he said. “Great men are above the common principles of morality.”

Shortly after, comes the following excerpt from this account of his speech:

“Shrimat Krishna’s advice (teaching) in the Gita is to kill even our teachers (and) our kinsmen. No blame attaches (to any person) if (he) is doing deeds without being actuated by a desire to reap the fruit (of his deeds). Shri Shivaji Maharaja did nothing with a view to fill the void of his own stomach (i.e., from interested motives). With benevolent intentions he murdered Afzulkhan for the good of others. If thieves enter our house and we have not (sufficient) strength in our wrists to drive them out, we should without hesitation shut them up and burn them alive.”

The translator says, in a note, that the text for “burn them alive” could also be translated to mean “oppress or torment them exceedingly”.

There was also this line: “Get out of the Penal Code, enter into the extremely high atmosphere of the Shrimat Bhagavatgita, and (then) consider the actions of great men.”

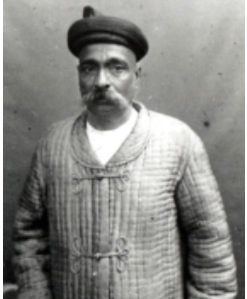

A week after these articles, the British Plague Commissioner of Pune Walter Rand and his military escort Lieutenant Charles Ayerst were shot by the brothers Damodar and Balkrishna Chapekar. Both Rand and Ayerst died. This was followed by Tilak’s arrest and his trial. The trial took place from September 8th to 11th, and then the 13th and 14th, in the year 1897. The jury comprised six Europeans and three Indians. They took forty minutes to pronounce him guilty, by a vote of six to three. He was sentenced to rigorous imprisonment for eighteen months. Bal, the acting manager and printer of Kesari, was acquitted as the jury did not find him responsible for the actual content of the weekly.

The social conservatism inherent in the first article, and in flashes in the second, is reflective of Tilak’s own legacy. Arguably the most popular leader of the Indian freedom struggle before Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, the latter had called him “the maker of modern India”. But what modern India was this? A scholar, mathematician, philosopher and tireless crusader for education (the New English School and Deccan Education Society, which established the Fergusson College, are among the institutions Tilak founded with friends and colleagues) he opposed the establishment as well as the curriculum of schools and colleges for girls vociferously. He supported widow remarriage but fought back actively on abolishing child marriage and his known stands on caste, untouchability and inter-caste marriage range from shaky to starkly problematic. Foundations of Tilak’s Nationalism: Discrimination, Education and Hindutva is a book that points to these aspects of Tilak’s legacy as well as his support for the then prevalent socio-economic order by, for instance, opposing pro-peasant legislations.

Also, Tilak’s conflation of Hindu religion, culture and symbology (glimpses of which can be seen in both the above articles) with social and political activism (eg. the household Ganesh festival he transformed into a grand public event and a rallying point for the national cause) won him and the freedom movement a vast number of supporters and adherents (as it was to win Gandhi later). But it may have had the effect of alienating many non-Hindus from his political vision of Swadesh and Swaraj.

It is interesting, for instance, that L. P. E. Pugh, the barrister defending Tilak in this trial, is noted to have argued (Page 125 of the report) that there was no suggestion in these articles of opposing the British Government and that, “That could never be attempted except by a combination of Hindus and Mohamedans, and praises of Shivaji were not likely to bring about such a combination.” This is interesting as Tilak was also credited with the founding of the Shivaji Festival in Maharashtra.

Evidence, however, makes us pause and wonder whether Tilak would have been in agreement with Pugh.

For, towards the end of the second article itself, are the following lines from Tilak’s address: “A country which (i.e. a people who) cannot unite even on a few occasions should never hope to prosper. Bickerings about religious and social matters are bound to go on until death; but it is most desirable that on one day out of the 365 we should unite at least in respect of one matter. To be one in connection with Shivaji does not mean that we are completely to forget our other opinions. For quarrelling there are other days of course.”

More to the point, less than a decade after this trial, in 1906, Tilak wrote an essay in The Mahratta (the other newspaper he ran, in English) titled ‘Is Shivaji not a National Hero?’.

It reads: “It is true that the Mahomedans and Hindus were then (during Shivaji’s time) divided; and Shivaji who respected the religious scruples of the Mahomedans had to fight against the Mogul rule that had become unbearable to the people. But does it follow from this that now that the Mahomedans and Hindus are equally shorn of the power they once possessed and are governed by the same laws and rules, they should not agree to accept as a hero one who in his own days took a bold stand against the tyranny of his time.”

Further, Tilak writes towards the end of the essay: “It was only in conformity with the political circumstances of the country at the time that Shivaji was born in Maharashtra. But a future leader may be born anywhere in India and, who knows, may even be a Mahomedan.”

Tilak was also instrumental in the signing of the 1916 Lucknow Pact, seen as a beacon of hope for Hindu-Muslim unity, between the Indian National Congress and the All India Muslim League led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah (who had also defended Tilak in his second sedition trial of 1908).

The first of the two articles Tilak was convicted for – ‘Shivaji’s Utterances’ – has lines like: “Could any man have dared to cast an improper glace at the wife of another, a thousand sharp swords (would have) leapt out of (their) scabbards instantly… You eunuchs! How do you brook this? Get that redressed!… How have all these kings become quite effeminate, like those on the chess board!”

The second article is unabashed in its justification of the violence of “great men”.

Sukeshi Kamra in a paper titled ‘Law and Radical Rhetoric in British India: The 1897 Trial of Bal Gangadhar Tilak’ examines these articles and their impact in the courtroom as well as in the press. “Tilak was not found to be involved in acts of physical violence against the government or, indeed, the European community, nor was the connection with revolutionaries of the Bombay Presidency (the Chapekar brothers) proved, by the government’s own admission,” Kamra writes in the paper’s conclusion. “Discursive violence, that too with several layers of mediation separating Tilak from their articulation, was declared sufficient (for the purpose of convicting him) unto the law.”

“Discursive”, meaning ‘of or relating to discourse or modes of discourse’. Tilak – through his interpretation of historical and mythical narratives as well as his commentary on current events – justified the violent acts of Indian revolutionaries. But he did not openly encourage or engage in such acts, nor refrain from condemning them.

For instance, when the Times of India, in 1897, linked the Rand assassination with Tilak’s writing, accusing him of sedition, he responded with a letter to the editor calling the murder a “shocking tragedy at Poona which we all deplore”. But he added: “Still I must state what I honestly believe to be the case, viz., that the unnecessary stringency of the plague measures, and not the writings of the Native Press, are responsible for the feelings of dissatisfaction referred to by you.”

In 1908, Tilak was convicted for sedition again. This time he was sentenced for six years. Again, for two articles— ‘The Country’s Misfortune’ and ‘These Remedies are not Lasting’. Again, in the Kesari. The judgment as well as the translated articles are available here. Broadly speaking, the articles expanded the public gaze, then directed towards the accidental killing of two women by revolutionaries Prafulla Chaki and Khudiram Bose (they had thrown a bomb on a carriage at Muzzafarpur, believe the Chief Presidency Magistrate Douglas Kingsford was in it) to include in its ambit the oppression of the British Government which had led to this act in the first place.

“The bomb-outrages were quickly condemned in my paper as in the Anglo-Indian papers,” Tilak said in his address to the jury at the trial. “We do not hold that bomb throwing is not a criminal act and is not reprehensible. We condemn it. But in condemning it we say that we must also condemn the repressive measures of Government.” Or perhaps Tilak’s views on the violence of his times can be summed up even more succinctly in a phrase from a series of articles he wrote on the arrival of the Bomb on the Indian scene— in an atmosphere of suppression by the government even as the people’s urge for freedom grew, he wrote, “violence, however deplorable, became inevitable”.

This attitude of Tilak’s was reflected in that of the extremist faction of the Indian National Congress that he, along with Lala Lajpat Rai and Bipin Chandra Pal, was a face of. The Extremists believed in education for Indians- free of British government control, agitations, boycotts, strikes, passive resistance, Swadeshi and non-cooperation to demand Swaraj or self-rule. These were radical (at the time) but nevertheless non-violent methods that were also adopted and evolved by Gandhian resistance later.

Finally, more lines from Tilak’s essay on Shivaji being a national hero: “It is not preached nor is it at all to be expected that the methods adopted by Shivaji should be adopted by the present generation… No one ever dreams that every incident in Shivaji’s life is to be copied by any one at present. It is the spirit which actuated Shivaji in his doings that is held forth as the proper ideal to be kept constantly in view by the rising generation.”

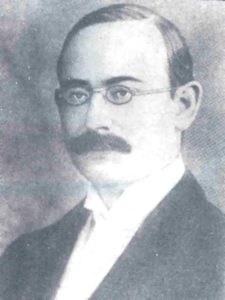

The part of the law report that deals with the judge Sir Arthur Strachey’s interpretation of sedition begins from Page 128. He began by outlining for the jury the dual charges against Tilak, for the two articles in Kesari, according to Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code.

Tilak was charged with:

– not only “having excited feelings of disaffection towards the Government established by law in British India”

– but also “having attempted to excite feelings of disaffection towards the Government established by law in British India”.

Strachey explained: “ …the section places on absolutely the same footing, the successful exciting of feelings of disaffection and the unsuccessful attempt to excite them, so that, if you find either of the prisoners has tried to excite such feelings in others, you must convict him even if there is nothing to show that he succeeded.”

Strachey went on to say (Page 132), “But there is a preliminary question to be considered, and that is, what is the meaning of Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, and what is the nature of the offence which makes it punishable? That preliminary question is for me to decide. The Code of Criminal Procedure requires you to accept from me the explanation of the section and of the offence—if my explanation is wrong, the responsibility rests on me and me alone… ”

Tedious as those acquainted with how the law works may find our stressing of the above, it cannot be stressed enough. Judges, too, write history. The law often gives them this power. The dark history that Strachey wrote in his interpretation of Section 124A lasted through some of modern India’s most significant decades and continues to pervade our national consciousness today, for it forms the backbone of sedition cases against Indian freedom fighters in these years. This doesn’t take away from the liability of sections like those dealing with sedition of course— a relic of colonialism that continues to thrive in India. But, on the whole, there are few mixes more potent than an oppressive law and an oppressive judge.

Finally, the crux of Strachey’s directions to the jury: his interpretation of the “disaffection” that the accused may be imprisoned for exciting towards the government and how that disaffection may be determined. Here are the key elements, in his own words, followed by our commentary.

– Page 134. The ‘absence’ of affection

“What are feelings of disaffection? I agree with Sir Comer Petheram in the Bangobasi case that disaffection means simply the absence of affection. It means hatred, enmity, dislike, hostility, contempt, and every form of ill-will to the Government. ‘Disloyalty’ is perhaps the best general term, comprehending every possible form of bad feeling to the Government.”

Note: The first assertion was incorrect. Sir Comer Petheram in the Bangobasi case (India’s first sedition case, one which didn’t result in a conviction) said that disaffection meant “a feeling contrary to affection”, not “the absence of affection”. However, he went on to define it like Strachey did: “dislike or hatred”. The problem with this definition has been discussed after the next point, but it’s important to note that, while Strachey corrected himself in the fineprint, his first false assertion – “that disaffection means simply the absence of affection” – had already biased the jury towards a much wider interpretation of disaffection than what existed in even Indian law.

– Page 135. “feelings of enmity” Vs. “mutiny or rebellion”

“The offence consists in exciting or attempting to excite in others certain bad feelings towards the Government. It is not the exciting or attempting to excite mutiny or rebellion, or any sort of actual disturbance, great or small… even if he (the accused) neither excited nor intended to excite any rebellion or outbreak or forcible resistance to the authority of the Government, still if he tried to excite feelings of enmity towards the Government, that is sufficient to make him guilty under the section.”

Note: In England at that time for words to be considered seditious they would have to encourage readers to violently overthrow the Government. But Strachey ignored English law, resorting instead to his own interpretation of the Indian Penal Code, which stretched the meaning of Sedition to merely exciting “feelings of disaffection”; ‘disaffection’ meaning, we reiterate, “the absence of affection”, “hatred”, “enmity”, “contempt” or even simply “dislike” and “every form of ill-will to the Government”.

– From Pages 139 and 140. “the minds of the readers”

“But you may ask, how are we to ascertain whether the intention of the accused was this, that, or the other? How can we tell whether his intention was simply to publish a historical discussion about Shivaji and Afzul Khan, or whether it was to stir up, under that guise, hatred against the Government?… In considering this, you must first ask yourselves what was the natural and probable effect of reading such articles in the minds of the readers of the Kesari, to whom they were addressed? Read these articles, and ask yourselves how the ordinary readers of the Kesari would probably feel when reading them?… If you think that such readers would naturally and probably be excited to entertain feelings of enmity to the Government, then you will be justified in presuming that the accused intended to excite feelings of enmity or disaffection.

Note: In 1949, George Orwell published ‘1984’, a novel about a dystopian future. But, with its themes of mind control, he might as well have been writing about the past. The idea that a jury can know what “the natural and probable effect” of reading every article will be in the mind of a reader is ridiculous. Even more ridiculous is the idea that the accused will know the “natural and probable effect” of every article she writes.

– Page 140. “At a time of agitation and unrest”

“ …I must impress upon you, as perhaps the most important point in my summing up, that you must bear in mind the time, the place, the circumstances and the occasion of the publication… An article which if published at a time of profound peace, prosperity and contentment would excite no bad feeling, might, at a time of agitation and unrest, excite intense hatred to the Government.”

Note: This set a dangerous precedent that haunts us till this day, especially in moments of history such as the one we are passing through now: the fear that, in times of “agitation and unrest”, a judge may be instrumental in taking away essential freedoms. Also, in taking them away such that they remain taken, even after such times have passed.

– Page 142. “It does not matter what form it takes”

“If the object of a publication is really seditious, it does not matter what form it takes. Disaffection may be excited in a thousand different ways. A poem, an allegory, a drama, a philosophical or historical discussion, may be used for the purpose of exciting disaffection, just as much as direct attacks on the Government.”

Note: The very nature of “a poem, an allegory, a drama, a philosophical or historical discussion” dictates that they may have many different meanings, that they are open to interpretation, often even beyond what their author intended. Exposing the writers of such to imprisonment for the “natural and probable effect” a judge or jury believes such forms of literature or scholarship may have “on the minds of readers” is equivalent, almost, to banning a lot of literature and academic and journalistic enquiry altogether.

To quote, once again, from Kamra’s paper:

“As Sudipta Kaviraj puts it, political trials were intended by the government of India to be ‘dramas of deterrence’, which, of course, they were not. They emerged, instead, as empowering fictions, with press reporting educating the reading public in a newly-politicised genre of melodrama. The texts that were on trial were broadcast far and wide in newspaper accounts, spreading the very arguments for which they were under question.”

This is something governments wishing to implement the sedition law often forget. If the accused is strategic, trying someone for sedition can easily defeat its own cause. In present times we have seen this in the cases of Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code being invoked against Kanhaiya Kumar, Hardik Patel, Umar Khalid and Anirban Bhattacharya. The cases against them, while causing untold harassment, have had the effect of amplifying what the accused stood for manifold.

The effect of invoking the section pertaining to sedition is, in one word, counter-intuitive.

“The two texts published in the newspaper Kesari and the trial-as-text can be said to have initiated a decades-long moment in which both thought and feeling, intellect and affect, were developed as social and political categories of knowledge and experience that had a significant bearing on the question of political self-determination,” writes Kamra. “There is a fairly profound question that emerges from the Kesari texts and the representation of the trial in the Indian press: if colonialism produced and depended on the circulation of and acquiescence to imperial narratives of colonisation, as well as the cultivation of affective bonds that naturalised loyalty to Empire, what would a national struggle, and its aim of securing political freedom, require by way of thought and affect?”

She reveals a part of the answer later in her paper, that reveals a telling account of the media around Tilak’s trial as well as of the way Tilak uses the trial itself, and his impending imprisonment, as symbols around which to rally a national imagination. Something other freedom fighters – from Gandhi to Bhagat Singh – were to do as well, later.

Tilak was reported to have said to his friends after the assassination of Rand and Ayerst, “The Anglo-Indians have thrown off their usual dignity and have turned to the law of the jungle. I am afraid some of us must be prepared to be sacrificed on the altar of their wrath. I expect they will lock me up soon.”

“If this hearsay is to be taken at face value,” writes Kamra. “Not only did he anticipate the legal action of the Bombay government, but was actively engaged in re-imagining it as an opportunity, which is exactly what it turned out to be.”

Here is her listing of the responses, of the prominent newspapers and political figures of the time, to Tilak’s trial:

– The front page of the Bengalee sported a black border, announcing this was out of “respect and sympathy” for Tilak.

– Hindu said, “The conviction of Mr. Tilak has cast a gloom over the whole country. The news has been received everywhere with intense grief and with a sense of humiliation. It is not that law and justice have been vindicated, but that the policy of reaction which for some time the enemies of the Indian people have been urging, has triumphed.”

– Advocate (an Allahabad based paper): “The sensation created by Mr. Tilak’s conviction throughout the length and breadth of India is natural… . The State trial has made his name a household word, and we think we are not exaggerating to say that every Indian who reads newspapers, or keeps himself in any way in touch with public opinion feels strongly for him on his misfortune, while there are thousands, nay, lakhs of men, who consider him a martyr to his country.”

– Surendranath Banerjee: “For Mr. Tilak my heart is full of sympathy, my feelings go forth to him in his prison-house. A nation is in tears.”

– Gopal Krishna Gokhale: “His conviction is a great national calamity.”

– But most significantly Tilak’s own English paper, The Mahratta: “It would be doing an injustice both to Mr. Tilak and his country if we concentrate our thoughts only on his undeserved sufferings. Does not Mr. Tilak serve his country, even by his imprisonment? Will he not have shown to his country-men, that the course of constitutional emancipation, like that of love, does not run smooth, and that the course is not to be abandoned simply because there are dark pitfalls in it? If there is any moral in the conviction of Mr. Tilak, it is this. Law does oftentimes go against justice and morality.”

Kamra writes in her conclusion: “The politicised image of the jail in nationalist rhetoric quite self-consciously takes as its mobilising discourse the dishonour, violation, pain and threat posed to survival itself, and effects a rhetorical transformation of the same into sacrificial violence.”

But the most compelling evidence of what Tilak (branded by Valentine Chirol as “the father of Indian unrest”) had pioneered – the image of courtroom and prison as emblems of national unrest – is Tilak himself. When warned, nearly a decade later, that he was going to be arrested, tried and sentenced for sedition again, he said to the friendly police officer cautioning him, “The government has converted the entire nation into a prison and we are all prisoners. Going to prison only means that from a big cell one is confined to a smaller one.”

To the jury he said: “There are higher powers that rule the destiny of men and nations; and it may be the Will of Providence that the cause which I represent may prosper more by my sufferings than by my remaining free.”

Soon enough, in 1909 this commitment to suffer, bravely embracing imprisonment, was mythologized in a poem published in Punjab’s radical newspaper Jhang Sial: “We pass our days in jail for the sake of India / Just as children suffer for the sake of their mother… We have suffered the pain inflicted by the baton and have also seen ourselves in irons / We endure all this for the sake of India… Say, what it is, then, if not a place of pilgrimage / Where Tilak Maharaj passes his days? / How can that be a fearful place?”

You can read the 41-page law report of Queen Empress V. Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Keshav Mahadev Bal from the Indian Law Reports (Criminal) 1898 here:

Law report of Queen Empress V. Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Keshav Mahadev Bal

Aims to make widely available primary sources, work by professional historians and scholars and writers who bring a fresh insight to historical understanding.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1943-1945 | |

|

1943-1945 |

| Origin Of The Azad Hind Fauj | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

[…] In this case, Tilak wrote two articles- ‘Shivaji’s Utterances’. Tilak and C.G. Bhanu, a notable Pune intellectual, spoke on this article at the Shivaji festival. The Bombay government claimed that through the speech, they incited disaffection that led to the killing of two British Officials. The Bombay High Court stated that it is the question of whether these articles can be considered as inciting disaffection against the government and has nothing to do with the case. Thus it merely reduced the interpretation of the legal text to ‘incitement of feelings of “disaffection”’. However, after the perusal of the article, it was observed that it illuminated the political ideology of Tilak as he stood at the radical side of liberalism. The High Court accepted the definition propounded in the Jogendra Chunder Bose about the word “disaffection” and opined that bad feeling against the government is criminal. They also held that it is immaterial whether there were any consequences. The intention of the offender is the primacy for qualifying for the offence of sedition. […]

[…] 3. Queen Empress v. Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Available Here. […]