While theory lends substance to a movement, life is breathed into it not by detached, ‘objective’ accounts, but rather by personalised, emotional appeals: whether they be in the form of music, literature, or art. Many oppressive systems generate a subculture wherein the oppressed talk of their struggles and lived experiences through common idioms, using popular mediums and modes. Or, as Bertolt Brecht put it, “Yes, there will also be singing. About the dark times.”

We write ‘subculture’ because of the format in which such art is born, as a strident revolution against the dominant culture that is a mainstay of the oppressor. But as the subculture grows and spreads and encompasses millions in its sweep, it becomes a ‘culture’ as relevant as any. It becomes an identity. It becomes history.

“It comes as a great shock,” James Baldwin once said, “Around the age of five or six or seven, to discover that Gary Cooper killing off the Indians… when you were rooting for Gary Cooper… that the Indians were you. It comes as a great shock to discover the country which is your birthplace and to which you owe your life and your identity has not in its whole system of reality evolved any place for you.” This culture becomes such a place, built up of literature, poetry and songs.

In India, the anti-caste movement has a rich history, wherein art (particularly autobiographical) has played a significant part in mobilisation as well as the creation of an anti-caste consciousness. These chapters from Singing/Thinking Anti-Caste: Essays on Anti-Caste Music and Text, by Yogesh Maitreya, look at the role of Dalit women in the Ambedkarite movement, and particularly at their production of anti-caste music and literature.

As the foremost icon of the movement is Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, it is natural that he is accorded a central position in the art of Dalit women as well. As Maitreya writes, “A living human being became a vigorous and passionate symbol in literary expression, as Ambedkar became both symbol and subject in the creative imagination of Dalit women’s songs.”

Furthermore, for Dalit women particularly, Ambedkar holds a special place as a staunch supporter of women’s education and liberation. Since its very inception, “Ambedkar’s movement made education for women integral to its agenda.” And so the Ambedkarite agenda was key to Dalit women finding the tools with which to articulate their unique experiences in the first place.

Ambedkar also deconstructed the roots of sexism in orthodox Hinduism, tracing these, for a great part, to the Manusmriti, which is also the text which most explicitly talks about caste-based hierarchies and corresponding ‘rules.’ Thus, he showed that sexism and caste-based discrimination in India have the same roots. In his enunciation of this issue and, further, by leading Dalits on the path to Buddhism, which “offered women equality in the field of knowledge, equal treatment and the freedom to make independent life choices,” Ambedkar was intrinsic in the shaping of the futures of Dalit women. As a consequence, Maitreya writes, “There are hundreds of Dalit women from this period who had lived Ambedkar as a philosophy of liberation in their lives.”

However, to imagine that Dalit women were passive actors in their own struggle would amount to a severe misconstruing of historic narrative. As the chapters below show, Dalit women have been and continue to be dynamic catalysts in the Ambedkarite Movement, directing it as well as infusing it with new life, time and again. They spread the message of a casteless society through songs about Ambedkar which served an important sociological purpose: to “convey history and inculcate a sense of dignity” amongst listeners, whether through tamashas or ‘Bhim palana,’ i.e. cradle songs dedicated to Ambedkar.

Dalit women have also been crucial in the inculcating of an anti-caste consciousness among young children of the community, through the leadership of “cultural processes,” where they were first introduced to the history and philosophy of Ambedkar as well as other icons.

Dalit women have also written some of the most illuminating works of Indian literature, especially in the genre of autobiography, which are discussed in the second chapter below. Ambedkar and his philosophy “remains at the core” of such autobiographies, which also reflect the “potential of Ambedkar as the foremost Indian feminist.”

Due to the intersection of casteism and patriarchy, writes Maitreya, Dalit women’s lived experiences are impacted by a “patriarchal-casteist brahmanism,” which can be fully understood neither by savarna women nor by Dalit men. Thus, “Dalit women writing their stories were doubly more liberating than Dalit men writing.”

(Quotes, where unattributed, are from Yogesh Maitreya’s Singing/Thinking Anti-Caste: Essays on Anti-Caste Music and Text).

Majhi aaji manhayachi

Ovi hee jatya warr,

Bhim banala sawali

Koti koti chya mathywar

My grandmother used to sing

This couplet while working the stone grinder

Bhim has become a shelter

Over the heads of millions.

The lines above are from Majhi Aaji, a poem by Kiran Sonwane, whose most popular version in Maharashtra is the one sung by Aniruddha Vankar. From the song, it is apparent that when Dalit women conceive of literature or music, they choose Ambedkar as their protagonist or hero. In their works, he is portrayed as no less than their emancipator.

Their portrayal of Ambedkar as a staunchly feminist ideal makes the role of Dalit women in the Ambedkarite movement significant on two levels: first as active participants in the movement, and second, as producers of literary narratives, including the ‘cradle songs’ that are crooned to youngsters.

In Vidarbha – and I am sure in other regions of Maharashtra – the tradition of Bhim Palana, or Bhim’s cradle songs, are an antithesis to the children’s songs based on mythological themes. A Bhim Palana is written with the intent to educate children about figures such as Ambedkar, to create individuals and citizens who will uphold the notion of equality, liberty and fraternity in their social and personal life.

Jyotiba Phule

After Mahatma Phule’s massive attack on the inhumane, unnatural and artificial caste system, which he did by opening the doors of education for girls across all castes, it was Babasaheb Ambedkar who went to great lengths to conceive of strategies to educate women, especially Dalit women. Urmila Pawar and Meenakshi Moon have compiled the most significant book on Dalit women’s history of struggle and triumphs, We Also Made History. They say in the book: “…the education of women and girls was an integral part of Ambedkar’s vision of social emancipation for the Dalits.” Some of his speeches, made on occasions of historical importance for the struggle, are quoted extensively, notably the speech addressing women at Mahaad satyagraha and the 1942 speech at the All-India Dalit Mahila Parishad held on 20th July 1942 in Nagpur.

From the moment he entered public life in 1927, Ambedkar’s movement made education for women integral to its agenda. He nurtured the desire for education within the hearts of Dalit women, using the Buddha’s egalitarian teachings as a basis for his arguments. Inspired, barely-educated women and those who had never climbed up the stairs of a school started to write songs that featured him and sing them.

From the moment he entered public life in 1927, Ambedkar’s movement made education for women integral to its agenda. He nurtured the desire for education within the hearts of Dalit women, using the Buddha’s egalitarian teachings as a basis for his arguments

From the 1940s onwards, Parbatabai Meshram from Nagpur worked for Ambedkar‘s movement. She wrote a few songs about how Ambedkar helped him feel confident and instilled the vision of a casteless society among them. In one of her songs she says:

He gave up his life for the good of the people,

That’s why, bai, I am passionate about Buddha.

Some say Buddha is Vishnu reborn,

But I ask you, bai, was Vishnu like the Buddha?

Did Brahma, Vishnu, Mahesh, ever behave like this?

That’s why, bai, I am passionate about Buddha.

In India, irrationality is propagated through the telling and retelling of mythological stories. All this is done in the name of religion, giving it a veneer of respectability that makes it very difficult to renounce. Yet, Ambedkar’s movement replaced such illogic with the history of the Buddha and his egalitarian teachings. The result was an incredible increase in education among the Mahar (now Buddhist) people, especially women. Parbatabai Meshram wrote:

Let your self-respect awake,

Don’t ask for charity.

Bhimdada told us this and left us:

Get ready to serve the people.

The sculptor of our lives said this and left.

Such songs do glorify or deify, but they intend only to convey history and inculcate a sense of dignity among listener and singer alike. They envision a casteless future with equality, liberty and fraternity at its foundation.

Thus unfolded on India’s literary scene of the time a unique phenomena. A living human being became a vigorous and passionate symbol in literary expression, as Ambedkar became both symbol and subject in the creative imagination of Dalit women’s songs.

The ‘Ambedkari Jalsa’ introduced by Bhimrao Kardak in the late 1920s had already planted Ambedkar‘s ideology into the musical tradition of Dalits. Dalit women further created the Bhim Palana genre, a result of their close association with the community’s earlier musical traditions. They are proof, as Mark Abel, who describes himself as a Marxist musicologist who works on the aesthetics of music and its interface with history and politics, has pointed out in Is Music a Language?, “creative musical ideas do not emerge from a mystical process of inspiration, but are the result of a practical and mental engagement with existing musical culture, or musical language.”

![Jilha Yuvak Sangh. Bhimrao Kardak (In the middle row, sitting on chair, second from the right) [Photo Credits: Yogesh Maitreya]](http://indianhistorycollective.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Bhimrao-Kardak-1.jpeg)

Jilha Yuvak Sangh. Bhimrao Kardak (In the middle row, sitting on chair, second from the right) [Photo Credits: Yogesh Maitreya]

The Tamasha – which has a legacy of imposition by the patriarchal elite-caste society on Dalit women – is one of the most popular forms of entertainment in Maharashtra. Earlier, it was performed mostly by Mahar and Kolhati-caste Dalit women. Ambedkar’s conversion to Buddhism in 1956 offered Tamasha performers a new form of cultural expression. Mahar (Buddhist) women went through a colossal psychological transformation, turning their musical talent into songs that feature the Buddha and Ambedkar.

Bhim Palana songs marked the culmination of Dalit women’s transition into intellectual life. At exactly this stage, the women were enacting what Friedrich Engels explains in Anti-Duhring, published in 1878: “Each mental image of the world system is and remains in actual fact limited, objectively by the historical conditions and subjectively by the physical and mental constitution of its originator.”

With Bhim Palana, Dalit women adopt the legacy of Theris, or Buddhist female monks, who wrote poetry known as Therigathas. Many Palanas from Vidarbha were based on popular Hindi movie tunes, but their lyrics have a completely different effect and intent than entertainment. For example, consider this Palana:

Mang na sarava bala pudh pudh raav

Mata pityach naav motha karava

Asa shikshan, asa shikshan ghyaw

Pardesh jav, pardesh jav

Molmajoori karun shikvin

Karin sambhal katkasarin

Kar vichar tu sodu nako shala

Bol tula kav hav.

Oh Child! Don’t step back, stand ahead

Bring prestige to the name of parents

So you study, such you must study

Go abroad, go abroad.

I’ll toil hard and make you study

I will take care of you with frugality

What do you think – would you leave school?

Tell me what you want.

The Palana narrates Ambedkar’s struggle for education abroad and inspires children to follow his footsteps. The emphasis on education is a manifestation of the cultural transformation among Dalit women. It reflects their strong desire to get the younger generation into school and their own struggle to make it possible.

The Palana narrates Ambedkar’s struggle for education abroad and inspires children to follow his footsteps. The emphasis on education is a manifestation of the cultural transformation among Dalit women. It reflects their strong desire to get the younger generation into school and their own struggle to make it possible.

Their quest to rebuild their history through songs also resurrects the past and the struggles in Buddhist history. For example, this song about Amrapali, a disciple of the Buddha who belonged to a non-elite caste:

With undefiled mind

I do my duty by the Buddha’s feet!

I am blessed-my life is blessed

By learning Sheel, Samadhi, Pradnya

I keep entire Dhamma intact

I follow the noble eight-fold path

I will practice all, through my acts

The mangroves of Amrapali

Lichhvis have known the mind

Impermanent is the body, so is wealth

Experiencing the wisdom of impermanence.

Even Buddhist history often omits the role of women in spreading its message, especially that of emancipation of women of all castes. (Read Ambedkar’s The Buddha and His Dhamma.) But to those aware of Buddhist history, the meaning of this poem will not be lost. It is inseparable from the history of social discourses on gender in a caste society.

Amrapali, a dancer, had invited the Buddha and his sangha to offer them daana in the form of food. The Licchavi elite-caste rulers had also invited the Buddha. The Buddha had accepted Amrapali’s invitation. Later, she became his disciple and pursued an intellectual life, which was denied to women of the time. This is the history the song excerpted above narrates.

Ramabai Ambedkar

Sushma Devi, one of the earlier singers of Bhim-Buddha songs, has immortalised Ramabai, Ambedkar’s first wife. In Majhya Bhimachya naavach, kunku kavil ramaan she narrates how hard Ramabai worked at home, alone, when Ambedkar was away studying in Columbia and the London School of Economics. The newest singer in this tradition is Kadubai Kharat, whose Bhiman mai sonyan bharali oti and Tumhi khata tya bhakriwar babasahebanchi hai rrr became a household number in Maharashtra days after it was launched. Kharat explains how Ambedkar made his way into her songs:

Thus, in Dalit women’s songs, emotions stimulate intellectualism in order to annihilate brahminical values from our minds. In them, melody is constructed through historical fact, and music is a medium to pursue a life of the mind, emancipating singers and listeners from social constructs.

Even before I was born, in my house there were images of the Buddha and Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar. My grandmother, I vividly remember, used to light incense sticks and candles in front of their images in the early morning and late evening. She also used to attend daily prayers at the Buddha Vihara which was just a few meters from my home. She used to “worship” them. But the stories narrated at the daily congregation at the Vihara were of Ambedkar’s struggle and his quest for education.

During a child-naming ceremony at our basti, “Bhim Palana” or Bhim’s cradle songs were sung to all of us children. This was our lyrical introduction to Ambedkar. In singing the Bhim Palanas, Ambedkar used to become a subject of music for us. All such cultural processes were led by women.

This is not just my story but one shared by millions of my generation who were born and raised in Vidarbha and other parts of Maharashtra. Women kept Ambedkar alive for us through songs and poems that we heard in childhood. As I have grown up and started reading literature written by Dalit women, I have understood why they have made him the protagonist of their literature, why they have made him the foremost feminist in their lives.

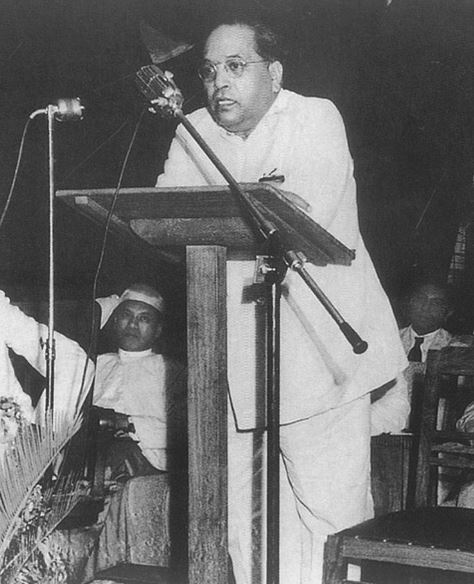

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar

In his succinct essay, Rise and Fall of Hindu Women, Ambedkar traces the fall of Hindu women to the period after the Manusmriti had been written. Decoding history with an anti-caste approach and the egalitarian agenda of the Buddha, he explains that Hindu women lost status due to the growing popularity of Buddhism. Buddhism offered women equality in the field of knowledge, equal treatment and the freedom to make independent life choices. These were not permitted to women in brahmani dharma.

In his succinct essay, Rise and Fall of Hindu Women, Ambedkar traces the fall of Hindu women to the period after the Manusmriti had been written. Decoding history with an anti-caste approach and the egalitarian agenda of the Buddha, he explains that Hindu women lost status due to the growing popularity of Buddhism.

The Manusmriti was written after the Mahaparinirvana of the Buddha. According to Ambedkar, who drew on references from the Therigathas or the Psalms of Buddhist female monks, this text was written in order to prohibit Hindu women from making their own choices. It sought to confine them to rigid Brahmanical codes of conduct and pulled them away from a life of the mind, quelling their chances at individual liberation.

Even in his movement to emancipate society, Ambedkar enacted these Buddhist strategies and wanted Dalit women to be the leaders of their own struggle. His candidly feminist approach was a revolutionary idea he derived from the stories of female Buddhist monks. Evidence of this exists in the form of narratives of Dalit women leaders who worked with Ambedkar. Sample this: Mukta Sarvagod, one of the earliest activists and writers from Ambedkar’s movement, recounts:

“In those days, there was a great awakening because of Babasaheb Ambedkar’s newspaper Bahiskrut Bharat, his satyagrahas, campaign tours and speeches. Girls had begun to take an interest in education. The names of women who had passed the vernacular examination and, who had become teachers, etc., were on everyone’s lips.”

Thus, Ambedkar helped bring the intellectual achievements of women into the public imagination at a time when women were forced to remain indoors. During this period, women leading social agitations were a rare sight. But Ambedkar turned out to be a guiding light and force that propelled women. Due to him, an ‘Untouchable’ woman, Shantabai Dani, became a MLC and led many agitations and committees populated by men. Dani, from Nashik, was a close associate of Ambedkar’s and a writer and social activist who rose to prominence. Her role in the agitation in support of landless people in Maharashtra is incomparable. Dani recounts:

There are hundreds of Dalit women from this period who had lived Ambedkar as a philosophy of liberation in their lives. Ambedkar appears in savarna women’s narratives, but inconsistently and this only started happening recently. Their earlier narratives erased Ambedkar’s feminist strategies and approaches.

Thus, Ambedkar helped bring the intellectual achievement of women into the public imagination at a time when women were forced to remain indoors. During this period, women leading social agitations were a rare sight. But Ambedkar turned out to be a guiding light and force that propelled women.

Even today, it is only Dalit women whose narratives and literature can offer insights into the potential of Ambedkar as the foremost Indian feminist. As Gopal Guru says, this is because “social location, which determines the perception of reality is a major factor which makes the representation of Dalit women’s issues by non-Dalit women less valid and less authentic.”

For the same reason, literature produced by Dalit women demands special attention and a revolutionary perspective because it is essentially more diverse than savarna women’s literature.

Ambedkar was carrying forward the legacy of Mahatma Phule who revolutionised India for women by opening schools for them in the eighteenth century in Maharasthra. In Ambedkar’s movement, substantial attention was given to education among women. In around 1932, to promote education among ‘Untouchable’ girls, some community associations set up scholarships and provided free schooling.

Shantabai Dani

For instance, the Somawanshi Mandal held a ceremony, attended by about 3,000 ‘Untouchable’ women, in which a scholarship of Rs. 10 was awarded to Mirabai Jadhav, a school student in Thane. Similarly, in Satara P.N. Rajbhoj declared that ‘Untouchable’ girls should be given scholarships and those studying in board schools should get the facilities they need. These efforts have been recorded by D.L. Kosare in Vidarbhateel Dalit Chalvalicha Itihas published by Dnyandepp Prakashan, Nagpur in 1984.

Such major steps became responsible for making Ambedkar a feminist leader. Later, when writings by Dalit women from Maharashtra emerged on the literary horizon, Ambedkar and his thoughts remained at their core. Their narratives were guided by the scientific approach spread by Babasaheb Ambedkar among the community. No autobiography by a Dalit woman from Maharashtra has glorified gods or goddesses of the Hindu pantheon. Instead, they have launched scathing attacks on them. Ambedkar sparked among them the quest for scientific thinking.

Such major steps became responsible for making Ambedkar a feminist leader. Later, when writings by Dalit women from Maharashtra emerged on the literary horizon, Ambedkar and his thoughts remained at their core. Their narratives were guided by the scientific approach spread by Babasaheb Ambedkar among the community

In 1981, Kumud Pawade’s autobiography, Antyasphot had been published. By 1982-83, Shantabai Kamble’s Majhya Jalmachi Chittarkatha had been periodicised. In 1987, Babytai Kamble’s Jina Amuch had been published. In the truest sense, Dalit women’s writings had started to appear as a collective expression. Dalit women have since published many remarkable books such as Mittlele Kawade by Mukta Sarvagod, Ratradi Amha by Shantabai Dani, Aiydan by Urmila Pawar, Majhi Mi by Yashodhara Gaikwad, Mi Nanda by Nada Keshav Meshram, and many more. The waves of poets and writers unleashed then continues to rise unbated.

Kumud Pawade

Ambedkar lives on in these books as the philosophy of liberation that informs the lived experience of their authors. These women have tasted the power of Ambedkar’s views on Buddhism and ideas about women’s liberation in caste society. Although their subjects are their lives, their culture, their experiences, their tragedies and triumphs, at their epicentre is Ambedkar’s vision for liberation of women.

It is the impact of Ambedkar’s movement on the minds of Dalit women—that those who were once enslaved by patriarchal-casteist brahminism—started to demolish its narrative body by writing their liberation in their own words. Dalit women writing their stories were doubly more liberating than Dalit men writing.

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of Yogesh Maitreya. You can buy Singing/Thinking Anti-Caste: Essays on Anti-Caste Music and Text, here.

Yogesh Maitreya is a writer, poet, translator, cultural critic and publisher. He is a PhD scholar at TISS, Mumbai. He became a full-time writer and translator after a brief stint as a journalist. He decided to establish his own publishing house, Panther’s Paw Publications, when he was confronted by the lack of mainstream publishers’ interest in Dalit writers. He is the author of The Bridge of Migration, Flowers on the Grave of Caste, Of Oppressor’s Body and Mind and Singing/Thinking Anti-Caste. You can read more about him here and more about Panther’s Paw Publications here. Information about Panther’s Paw Publications’ latest titles is available here.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1943-1945 | |

|

1943-1945 |

| Origin Of The Azad Hind Fauj | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply