Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, from the early 1920s onwards, has been, and continues to be, a towering figure in the Indian discourse. Whether you agree or disagree with what he said and wrote is irrelevant. His assertions stir so much debate that a lot of modern Indian intellectual and popular discourse can be seen to have evolved around him, and this is a continuing phenomenon.

This is one reason why the primary sources the Indian History Collective has carried include so many letters, speeches and articles by Gandhi, or those interacting with him. We have republished Gandhi’s debate with Rabindranath Tagore over Non-Cooperation in 1921 and, again, on Gandhi’s ideas of Swaraj and the charkha (1925-1926). Also, Gandhi’s famous ‘foreigners in their own land’ speech, delivered at the opening of the Benares Hindu University, through which he riles up those present so much that, after repeated interruptions, the president himself leaves the meeting, refusing to hear him anymore. We have also carried Gandhi’s acrimonious exchanges with Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, published by the latter at the end of his groundbreaking Annihilation of Caste. A paper by Sujay Biswas, a Dalit scholar, traces Gandhi’s shifting stances on caste in greater detail, via an array of primary sources. Also, excerpts from the diary of Mahadev Desai, Gandhi’s personal secretary, describing the days leading up to Gandhi’s decision to fast unto death, to protest Ramsay MacDonald’s Communal Award.

Another reason why Gandhi’s writing and speeches make for telling primary sources is his candour. Ramchandra Guha writes in his biography Gandhi: The Years That Changed The World (1914-1948), “Gandhi was singular in that he exposed his defects, his manias, his lusts, his passions and his superstitions, to the whole world, through his writings in periodicals he himself edited and published.” Guha quotes an English Quaker who interacted with him over twenty years: “Gandhiji had no private life, as we Westerners understand the expression.”

But how can we examine Gandhi’s approach towards caste, without considering his views on religion? We have touched upon this through a curation of Gandhi’s writing and speeches on Diwali. But, there is a lot more to look at. To quote Guha again, “Despite his long battles with Hindu orthodoxy, Gandhi still called himself a Hindu. Perhaps this was out of sentimental attachment to an ancestral faith, or for tactical reasons, since positioning himself as an outsider would make it harder to persuade India’s Hindu majority of his reformist and egalitarian credo. Yet, Gandhi’s faith resonates closely with spiritual (or intellectual) traditions that are other than ‘Hindu’. The stress on ethical conduct brings him close to Buddhism, while the avowal of non-violence and non-possession is clearly drawn from Jainism. The exaltation of service is far more Christian than Hindu. The emphasis on the dignity of the individual echoes Enlightenment ideas of human rights.”

Here is an exploration of Gandhi’s idea of Hinduism through six excerpts which carry his thoughts on religious conversion. The excerpts, dating from 1924 to 1937, have been taken from Young India and Harijan— his weekly publications. They are, for the most part, self-explanatory, but some context with regard to the milieu is necessary to understand them.

Gandhi’s understanding of conversion has to be read through the lens of discussions around conversion in the late 19th and early 20th century. In the liberal form of government that the British had constituted in India, political power began to be measured by the representation of a community within a population; i.e. by majorities and minorities. Or, as Arundhati Roy concludes in her essay The Doctor and the Saint, “Under the new dispensation, demography became vitally important.” This set the stage for the politics of conversion within British India.

Before this modern political identification became necessary in the 19th century, many religious communities and castes identified with both Hindu and Muslim lived traditions. There was, relatively speaking, less of a need to affiliate yourself with a religious category exclusively. The boundaries between Hindu and Muslim communities were less binary and more ambiguous than what was to come. For instance, in their paper Mass Conversions to Hinduism among Indian Muslims Sikand Yoginder and Manjari Katju write that the Rajput Malkana community, “followed both Hindu and Muslim customs, because of which they were also known as adhbariya [half Hindu-half Muslim]”. Or, to quote from Richard Eaton’s essay Who are the Bengal Muslims? Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal, “Although today one habitually thinks of world religions as self-contained and complete systems with well-defined borders, such a static or fixed understanding does not apply to Bengal’s premodern frontier, a fluid context in which Islamic superhuman agencies, typically identified with local superhuman agencies, gradually seeped into local cosmologies that were themselves dynamic.”

Yoginder and Katju go on to write, “The mass conversions of Muslims to Hinduism assumed significant proportions only in the 1920s, in the backdrop of concerted efforts by the Muslim and Hindu elites to inflate their numbers so as to enhance their political bargaining power.” Caste elites within religions wanted to consolidate their power and organise their communities politically as majorities on the census. This consolidation of identity happened in two primary ways. Socio-religious reform movements focused on reforming syncretic cultures and customs of various castes and communities to fit a hegemonic tradition, excising ‘outside’ influence. To quote Yoginder and Katju again, “It is interesting to note that… group conversions to Hinduism organised by the Arya Samaj entailed essentially the giving up of a certain Islamic customs such as the burial of the dead, ‘nikah’, the visiting of ‘dargahs’ and circumcision, rather than the imparting of Hindu religious knowledge to the new convert.” Roy writes, “When reformers began to use the word ‘Hindu’ to describe themselves and their organisations, it had less to do with religion than with trying to forge a unified political constitution out of a divided people. This explains the reformers’ constant references to the ‘Hindu nation’ or the ‘Hindu race’.” Such a hegemonic tradition also modelled itself more to the understanding of religion as practised by ‘upper’ caste Hindus and Muslims. Some of the opposition and anxiety caste Hindu elites expressed against separate Dalit electorates can also be ascribed to their fear of becoming a ‘minority’ or losing ‘cohesion’.

Christian Missionaries, Arya Samaj ‘shuddhi’ preachers, and Tablighi Jamaat preachers were all trying to convert communities with syncretic traditions into their own ‘modern’ religious identifications. Leaders of the Arya Samaj, such as Swami Shraddhanand, began the Shuddhi movement to welcome communities ‘lost’ to Islam ‘back’ to the Hindu fold. The Arya Samaj brought 1,63,000 Malkana Rajputs back to the Hindu fold through episodes of mass conversion.

“The founders of the Deoband movement responded to the eradication of Muslim sovereignty in India (in 1858) by focusing on the moral uplift of the Muslim community,” writes Farina Mir. “The leaders of the movement were ulema who saw the salvation of India’s Muslims in this group. To this end, they started a seminary in the North Indian town of Deoband in 1867 to train ulema. The reformed Sunni Islam taught at the seminary… advocated doing away with what were deemed un-Islamic practices, particularly popular rituals at births, deaths, and marriages. Although Sufism was an integral feature of the movement—many Deoband ulema simultaneously served as Sufi spiritual guides—the movement denounced particular kinds of Sufi devotion, such as prostration at a saint’s tomb, that it interpreted as approaching ‘shirk’, or associating any being or thing too closely with God.”

Such movements were opposed by Gandhi. Writing for Young India in March 1929, he wrote, “I disbelieve in the conversion of one person by another. My effort should never be to undermine another’s faith but to make him a better follower of his own faith.” He saw these movements as a major cause for Hindu-Muslim-Christian tension, as is described in the first excerpt we have carried— Hindu-Muslim Tension: Its Causes and Cure. Sarah Claerhout and Jakob De Roover in their paper The Question of Conversion in India attribute Gandhi’s attitude towards conversion due to Christian missionary activity as a fundamental difference in how Hindus and Christians understand the meaning of ‘religion’ and the freedom to practise it. For Christianity practising their freedom of religion, they write, “is said to consist of one path through which God saves humanity from eternal damnation, while the other paths are devil’s snares”. They continue, that for Hinduism, “The diversity of religions corresponds to the innate diversity among human beings. Various valid paths exist, which have been developed for and by different groups of people.” Hindus, the authors argue, viewed their freedom to practise Hinduism as the freedom to follow the traditions passed down by their ancestors.

To return to the excerpts, in Hindu-Muslim Tension: Its Causes and Cure ‘Tabligh’ refers to the Tablighi Jamaat, an offshoot of the Deobandi socio-religious reform movement among Muslims, a parallel to the Shuddhi movement led by the Arya Samaj. In No Conversion Permissible the ashram referred to is the Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad. Mirabai or Madeleine Slade was Gandhi’s lifelong disciple. Originally from a British aristocratic family, she came to believe greatly in Gandhi’s mission. He nicknamed Slade after the famous 16th century poet and devotee of Krishna: Mirabai. The C.F. Andrews conversing with Gandhi in Equality of Religions refers to Charles Freer Andrews. He was an English Anglican priest who came to teach at St . Stephens College, Delhi in 1904. After meeting Rabindranath Tagore in 1912, he left Stephens to teach at Shantiniketan. Around that time, in 1914, he met Gandhi. They remained life-long friends. Importantly, he was a long-time supporter of the struggle for Indian Independence. Eric J Sharpe writes, “Gandhi, in particular, often cited Andrews as a model Christian missionary who never proselytised but was always prepared to serve the people of India.”

Hindu-Muslim Tension: Its Causes and Cure

In my opinion there is no such thing as proselytism in Hinduism as it is understood in Christianity or to a lesser extent in Islam. The Arya Samaj has, I think, copied the Christians in planning its propaganda. The modern method does not appeal to me. It has done more harm than good. Though regarded as a matter of the heart purely and one between the Maker and oneself, it has degenerated into an appeal to the selfish instinct. The Arya Samaj preacher is never so happy as when he is reviling other religions. My Hindu instinct tells me that all religions are more or less true. All proceed from the same God, but all are imperfect human instrumentality. The real shuddhi movement should consist in each one trying to arrive at perfection in his or her own faith. In such a plan character would be the only test. What is the use of crossing from one compartment to another, if it does not mean a moral rise? What is the meaning of my trying to convert to the service of God (for that must be the implication of shuddhi or tabligh) when those who are in my fold are every day denying God by their actions? ‘Physician, heal thyself is more true in matters religious than mundane. But these are my views. If the Arya Samajists think that they have a call from their conscience, they have a perfect right to conduct the movement. Such a burning call recognizes no time limit, no checks of experience. If Hindu-Muslim unity is endangered because an Arya Samaj preacher or a Mussulman preacher preaches his faith in obedience to a call from within, that unity is only skin-deep. Why should we be ruffled by such movements? Only they must be genuine. If the Malkanas wanted to return to the Hindu fold, they had a perfect right to do so whenever they liked. But no propaganda can be allowed which reviles other religions. For that would be negation of toleration. The best way of dealing with such propaganda is to publicly condemn it.

Young India, 29 May 1924

Why I am a Hindu?

An American friend who subscribes herself as a lifelong friend of India writes:

As Hinduism is one of the prominent religions of the East, and as you have made a study of Christianity and Hinduism, and on the basis of that study have announced that you are a Hindu, I beg leave to ask of you if you will do me the favour to give me your reasons for that choice. Hindus and Christians alike realize that man’s chief need is to know God and to worship Him in spirit and in truth. Believing that Christ was a revelation of God, Christians of America have sent to India thousands of their sons and daughters to tell the people of India about Christ. Will you in return kindly give us your interpretation of Hinduism and make a comparison of Hinduism with the teachings of Christ? I will be deeply grateful for this favour.

I have ventured at several missionary meetings to tell English and American missionaries that if they could have refrained from ‘telling’ India about Christ and had merely lived the life enjoined upon them by the Sermon on the Mount, India instead of suspecting them would have appreciated their living in the midst of her children and directly profited by their presence. Holding this view, I can ‘tell’ American friends nothing about Hinduism by way of ‘return’. I do not believe in people telling others of their faith, especially with a view to conversion. Faith does not admit of telling. It has to be lived and then it becomes self-propagating.

Nor do I consider myself fit to interpret Hinduism except through my own life. And if I may not interpret Hinduism through my written word, I may not compare it with Christianity. The only thing it is possible for me therefore to do is to say as briefly as I can, why I am a Hindu.

Believing as I do in the influence of heredity, being born in a Hindu family, I have remained a Hindu. I should reject it, if I found it inconsistent with my moral sense or my spiritual growth. On examination I have found it to be the most tolerant of all religions known to me. Its freedom from dogma makes a forcible appeal to me inasmuch as it gives the votary the largest scope for self-expression. Not being an exclusive religion, it enables the followers of that faith not merely to respect all the other religions, but it also enables them to admire and assimilate whatever may be good in the other faiths. Non-violence is common to all religions, but it has found the highest expression and application in Hinduism. (I do not regard Jainism or Buddhism as separate from Hinduism.) Hinduism believes in the oneness not of merely all human life but in the oneness of all that lives. Its worship of the cow is, in my opinion, its unique contribution to the evolution of humanitarianism. It is a practical application of the belief in the oneness and, therefore, sacredness, of all life. The great belief in transmigration is a direct consequence of that belief. Finally the discovery of the law of varnashrama is a magnificent result of the ceaseless search for truth. I must not burden this article with definitions of the essentials sketched here, except to say that the present ideas of cow-worship and varnashrama are a caricature of what in my opinion the originals are. In this all too brief a sketch I have mentioned what occurs to me to be the outstanding features of Hinduism that keep me in its fold.

Young India, 20th October 1927.

No Conversion Permissible

The English press cuttings contain among many delightful items the news that Miss Slade, known in the Ashram as Mirabai, has embraced Hinduism. I may say that she has not. I hope that she is a better Christian than when four years ago she came to the Ashram. She is not a girl of tender age. She is past thirty and has travelled all alone in Egypt, Persia and Europe befriending trees and animals. I have had the privilege of having under me Mussulman, Parsi and Christian minors. Never was Hinduism put before them for their acceptance. They were encouraged and induced to respect and read their own scriptures. It is with pleasure that I can recall instances of men and women, boys and girls, having been induced to know and love their faiths better than they did before if they were also encouraged to study the other faiths with sympathy and respect. We have in the Ashram today several faiths represented. No proselytizing is practised or permitted. We recognize that all these faiths are true and divinely inspired, and all have suffered through the necessarily imperfect handling of imperfect men. Miss Slade bears not a Hindu name but an Indian name. And this was done at her instance and for convenience.

Young India, 20 February 1930

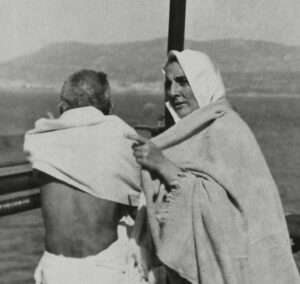

Photo by James A. Mills/AP/REX/Shutterstock (7400934j) Mahatma Gandhi with Madeleine Slade (Mirabehn) aboard the S.S. Rajputana en route to the Second Round Table Conference on Dominion Status for India (September – December 1931) in London.

Equality of Religions (1)

C.F. Andrews: “What would you say to a man who after considerable thought and prayer said that he could not have his peace and salvation except by becoming a Christian?”

Gandhiji: “I would say if a non-Christian (say a Hindu) came to a Christian and made that statement, he should ask him to become a good Hindu rather than find goodness in change of faith.

C.F.A.: “I cannot in this go the whole length with you, though you know my own position. I discarded the position that there is no salvation except through Christ long ago. But supposing the Oxford Group Movement people changed the life of your son, and he felt like being converted, what would you say?”

Gandhiji: “I would say that the Oxford Group may change the lives of as many as they like, but not their religion. They can draw their attention to the best in their respective religions and change their lives by asking them to live according to them. There came to me a man, the son of brahmana parents, who said his reading of your book had led him to embrace Christianity. I asked him if he thought that the religion of his forefathers was wrong. He said, ‘No.’ Then I said: ‘Is there any difficulty about your accepting the Bible as one of the great religious books of the world and Christ as one of the great teachers?’ I said to him that you had never through your books asked Indians to take up the Bible and embrace Christianity, and that he had misread your book–unless of course your position is like that of the late M. Mahomed Ali’s, viz. that ‘a believing Mussulman, however bad his life, is better than a good Hindu’.”

C.F.A.: “I do not accept M. Mahomed Ali’s position at all. But, I do say that if a person really needs a change of faith I should not stand in his way.”

Gandhiji: “But don’t you see that you do not even give him a chance? You do not even cross-examine him. Supposing a Christian came to me and said he was captivated by a reading of the Bhagawata and so wanted to declare himself a Hindu, I should say him: ‘No. What the Bhagawata offers the Bible also offers. You have not yet made the attempt to find it out. Make the attempt and be a good Christian.”

C.F.A.: “I don’t know. If someone earnestly says that he will become a good Christian, I should say, ‘You may become one,’ though you know that I have in my own life strongly dissuaded ardent enthusiasts who came to me. I said to them, ‘Certainly not on my account will you do anything of the kind.’ But human nature does require a concrete faith.”

Gandhiji: “If a person wants to believe in the Bible let him say so, but why should he discard his own religion? This proselytization will mean no peace in the world. Religion is a very personal matter. We should by living the life according to our lights share the best with one another, thus adding to the sum total of human effort to reach God.”

“Consider,” continued Gandhiji, “Whether you are going to accept the position of mutual toleration or of equality of all religions. My position is that all the great religions are fundamentally equal. We must have innate respect for other religions as we have for our own. Mind you, not mutual toleration, but equal respect.”

Harijan, 28 November 1936

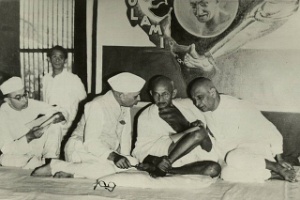

Gandhi and C. F. Andrews, December 1938

Equality of religions (2)

There is in Hinduism room enough for Jesus, as there is for Mohammed, Zoroaster and Moses. For me the different religions are beautiful flowers from the same garden, or they are branches of the same majestic tree. Therefore they are equally true, though being received and interpreted through human instruments equally imperfect. It is impossible for me to reconcile myself to the idea of conversion after the style that goes on in India and elsewhere today. It is an error which is perhaps the greatest impediment to the world’s progress towards peace. “Warring creeds” is a blasphemous expression. And it fitly describes the state of things in India, the mother, as I believe her to be, of Religion or religions. If she is truly the mother, the motherhood is on trial. Why should a Christian want to convert a Hindu to Christianity and vice versa? Why should he not be satisfied if the Hindu is a good or godly man? If the morals of a man are a matter of no concern, the form of worship in a particular manner in a church, a mosque or a temple is an empty formula; it may even be a hindrance to individual or social growth, and insistence on a particular form or repetition of a credo may be a potent cause of violent quarrels leading to bloodshed and ending in utter disbelief in Religion, i.e. God Himself.

Harijan, 30 January 1937

Attitude of Christian Missions to Hinduism

My fear is that though Christian friends nowadays do not say or admit that Hindu religion is untrue, they must harbour in the breasts the belief that Hinduism is an error and that Christianity as they believe it is the only true religion. Without some such thing it is not possible to understand, much less to appreciate, the C.M.S. appeal* from which I reproduced in these columns some revealing extracts the other day. One could understand the attack on untouchability and many other errors that have crept into Hindu life. And if they would help us to get rid of the admitted abuses and purify our religion, they would do helpful constructive work which would be gratefully accepted. But so far as one can understand the present effort, it is to uproot Hinduism from the very foundation and replace it by another faith. It is like an attempt to destroy a house which though badly in want of repair appears to the dweller quite decent and habitable. No wonder he welcomes those who show him how to repair it and even offer to do so themselves. But he would most decidedly resist those who sought to destroy that house that had served well with him and his ancestors for ages, unless he, the dweller, was convinced that the house was beyond repair and unfit for human habitation. If the Christian world entertains that opinion about the Hindu house, ‘Parliament of Religions’ and “International Fellowship’ are empty phrases. For both the terms presuppose equality of status, a common platform. There cannot be a common platform as between inferiors and superiors, or the enlightened and unenlightened, the regenerate and the unregenerate, the high-born and the low-born, the caste-man and the outcaste. My comparison may be defective, may even sound offensive. My reasoning may be unsound. But my proposition stands.

Harijan, 13 March 1937

To write a short biography for a personality like Mohanchand Karamchand Gandhi, who kept redefining himself and his impact, and whose enormous persona and impact the world is still struggling to define, would be an audacity. If one were to attempt such an audacity, one would perhaps say that this man, accorded the title ‘Mahatma’ (loose translation: ‘great soul’) cast a gigantic influence over the twentieth century and continues to cast one over the twenty first. As a political figure he arguably did more than anyone else to bring the British Raj down. As a practical philosopher his legacy of non-violence and satyagraha remains invaluable. But along with the ills of a tyrannical government, Gandhi also fought the ills of an oppressive society, along the faultlines of caste, gender and religion. He ran many journalistic publications and outlined his distinct body of thought in many books. You can read more about him and his work here.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1100–1199 CE | |

|

1100–1199 CE |

| Topography as History: Reading Kashmir through Rajatarangini | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1828-1843 | |

|

1828-1843 |

| Scandal of Manners: ‘Urinating Standing Up’ | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1910-1950 | |

|

1910-1950 |

| Forging Unity: Vallabhbhai Patel and the Politics of Nationalism | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Patriarchal Lechery | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1943-1945 | |

|

1943-1945 |

| Origin Of The Azad Hind Fauj | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1950-1951 | |

|

1950-1951 |

| Panikkar’s 1950 Ordeal: China’s Moves, Family Crisis, and Diplomatic Distrust | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply