The title we have chosen for this excerpt is the same as the first line of Manan Ahmed Asif’s illuminating book, where it’s from: The Loss of Hindustan – The Invention of India.

Did South Asia have a shared regional identity prior to the arrival of Europeans in the late fifteenth century? Asif believes it did and:

“Yet, in the nineteenth century, the word Hindustan begins to fade from the colonial archive. The major histories of the subcontinent, written in the early parts of the nineteenth century, were now histories of ‘British India.’ With the British East India Company (BEIC) ascendant, the Maratha or the Sikh polities did not invoke Hindustan in their political claims. There was a brief last resurgence of Hindustan in 1857. The rebels and revolutionaries who opposed BEIC rule rallied to the flag of the Mughal king, Bahadur Shah Zafar. He was, once again, hailed as the Shahanshah-i Hindustan—clearly there remained an idea of Hindustan. After violently crushing the revolution, Queen Victoria took British India under her direct rule and assumed the title of Empress of India, sending Bahadur Shah Zafar to die in exile in Burma. His contemporary, the poet Mirza Ghalib recognized the momentous change in the fate of the subcontinent with this verse:

‘Hindustan sayah-i gul pa-e takht tha

Jah-o-jalal-i ‘ahd-e visal-e butan nah puchh’

(Hindustan was the shadow of a rose at the foot of the throne

the grandeur, the splendor of that age of union with the gods, don’t ask!).

And so, per Ghalib, Hindustan became the past.”

Throughout the book as well as in the chapter that this excerpt has been drawn from (titled ‘The Places In Hindustan’) Asif lays out meticulously what the historians and writers of this Hindustan, that “became the past”, have chronicled. Historians and writers like Mas’udi (Muruj Al Dhahab), Firdausi (Shahnama), Gardizi (Zain al-Akhbar), Fakhr-i Mudabbir Mubarakshah (Shajara-i Ansab and Adab al-Harb wa al Shuja‘a), Juzjani (Tabaqat-i Nasiri), Khusrau (Khaza’in al-Futuh, Nuh Sipihr), Barani (Tarikh-i Firuz Shahi), Shams Siraj ‘Afif (also Tarikh-i Firuz Shahi) and Abu’l Fazl (A’in-i Akbari, part of his Akbarnama).

But particularly Firishta, a Deccan historian writing “far from the Mughal polity” in the early seventeenth century, who wrote Tarikh-i Firishta. Writes Asif:

“Who was Firishta? He did not leave any sustained autobiographical account, and what we know of him is parsed only through his two major works—the Tarikh and his work on medicine, Dastur al-atibba. Based on Briggs, writing in the early nineteenth century, the conventional take is that Firishta was an immigrant from Astarbad (now Gorgan in Iran by the Caspian Sea). This is, however, doubtful. Firishta was likely born in or around Ahmadnagar where his father had moved during the Nizam Shahi polity. His name was Muhammad Qasim. He once refers to himself, in his Tarikh, as ‘Astarabadi’ (meaning his ancestors hailed from Astarabad) and once as ‘Hindu Shah.’ However, in all references to himself he says he was commonly known as ‘Firishta.’ He began his career at the Nizam Shahi court as the captain of the palace guard. In 1589, Firishta moved to Bijapur, to the court of Ibrahim ‘Adil Shah II. Firishta’s patron, ‘Adil Shah, built a new city called Nauraspur and also wrote a treatise on musical theory and songs called Kitab-i Nauras. We do not know when or where Firishta died.”

Tarikh-i Firishta, which Asif calls “the first comprehensive history of Hindustan in terms of time and geography”, runs to over a thousand folio pages (a recent edition is in four volumes) and comprises a prologue and twelve chapters. Eleven delve into the histories of rulers across Hindustan (Lahore, Delhi, the Deccan, Gujarat, Malwa, Khandesh, Bengal, Multan, Singh, Kashmir and Malabar) and the last chapter is about the Sufis as well as religious scholars. A conclusion reflects on Hindustan as a marker of heaven on earth. Firishta steers clear of the genealogical table approach where history was written as a series of births, beginning from the creation of Adam. He also avoids the kind of history writing which charts the rise and fall of royal families.

Instead, writes Asif “his history is a history of place first and foremost”. After “spatial reframing” (as per his way of ‘seeing’ Hindustan) Firishta draws from written and spoken texts, Sanskrit and Persian, including oral histories and travelers’ tales. “He is keen,” Asif says, “To incorporate dissenting voices, and eager to resolve conflicts in his own tabulations.” Sometimes he “sits in judgment” and sometimes “lets the contradiction remain on page”.

What is remarkable, is how the narrative of Firishta’s Tarikh “expertly intertwines the Mahabharata and Shahnama cosmologies”. As Asif puts it: “This history of inventions—regions, cities, idol worship, mathematics, music, taming of elephants—theorized within Firishta’s frame is thus a history for both Muslims and Hindus in Hindustan.” Also: “Firishta’s history is the first history of Hindustan as a concept, an idea and a place that contains multitudes of faiths and polities. Firishta is providing a unified history of Hindustan, stretching back through Noah and Adam to the Indra. His emphasis is also in the Deccan as the center of Hindustan. The rulers of the Deccan are the inheritors of the whole history of Hindustan even as they remain politically and formally a smaller power compared to the Mughals.”

Gazing back at the history of Hindustan through this conceptual lens, we are able to avoid not just colonial biases, but also religio-cultural ones and those that revolve around a Delhi-based or North Indian centrism.

The Loss of Hindustan, writes Asif, “is a history of the Tarikh-i Firishta and its intellectual world”. It “is not a work of political history.” It “sees Hindustan through the eyes of Firishta’s Tarikh” to “crystallize a vision of a concept that is now opaque at best.” Also, “It is only through an intellectual history of history writing that one can see the work of a concept like Hindustan in full effect.”

However, according to Asif, even as we “reassess the historical traditions of Hindustan” we need to rethink “the historiography of the colonial period”, and that is where this excerpt comes in. Asif argues that his “aim is not to rehash” the “debates” fired up by Edward Said’s famous critique of Orientalism, rather to “argue for a methodological shift for the historian of the medieval and early modern periods in the subcontinent.” He writes: “I would like to insist that the material and intellectual frames of colonial knowledge-making be thoroughly investigated in any effort at a history of the precolonized world.”

And so the book juxtaposes “the colonial imagination of the histories and peoples of India against the world-making in histories of Hindustan.” The following excerpt, after a short introduction to the broader ideas, examines the former, in the context of the “geography of Hindustan”. The chapter goes on, after the section we have excerpted ends, to explore the histories of this geography by historians such as those we have mentioned above, particularly Firishta, but in this excerpt Asif lays bare the “colonial obsession of carving out the territory of the subcontinent into domains of political control and resource extraction, of treaties and recognitions of indirect rule” as opposed to “Firishta’s Hindustan” which “reflected the broader political and cultural landscape of the subcontinent that was firmly present in the seventeenth century.”

To eke out the contours of the European gaze, Asif cites writings such as those of Richard Hakluyt, Samuel Purchas, Thomas Roe, Joseph Tieffenthaller, Anquetil du Perron and James Rennell. He follows closely the transitions in European narratives:

“The first transition… is that the ‘first-person’ account of their travels in the subcontinent begins to take priority over the abstract geographies from Greek or Roman sources… ”

“The second transition was the inclusion of local knowledge, first incorporated as oral reports, and then more authoritatively as ‘translations’ from local sources… ”

He highlights how “the map emerged in the early seventeenth century as, analytically, the most powerful instrument of colonization. It was a representative medium, and an aspirational visual, for European power in the subcontinent.”

Finally, he exposes the biases that accompany these narratives, despite their transitions. Biases that extend to and flourish in the European cartography as well. For example, viewing the history and geography of the subcontinent from primarily “the Mughal perspective”. Or “the gaze that looked for wonder or marvel or horror”: “Delarouchette labels ‘the Beels a Wild Nation of Robbers,’ ‘Village of Robbers,’ ‘Bhoodie where they adore a Serpent,’ ‘the Khands a wild people,’ ‘Rettenpour Wild People,’ ‘subterraneous caves out of which issue Fire, Wind, and Water,’ the ‘Diamond Mines,’ and much else in translating the accounts of Tieffenthaller and du Perron into the cartographic.”

These biases continue to threaten or influence historians and lay people, in subtle or blatant avatars, today. This, too, is why it is important to read this excerpt.

Where was Hindustan? The nineteenth-century colonial obsession of carving out the territory of the subcontinent into domains of political control and resource extraction, of treaties and recognitions of indirect rule, remains starkly clear in the themes of the histories they produced, the archives they assembled, and the people they enslaved. The colonial episteme organized Hindustan under the rubric of politics, extracting the Mughal administrative vocabulary to transfer land management. It delimited sacred spaces: temples from mosques, shrines from cemeteries. It defined public and private places, rural and urban places. Through the census, they began to carve out the Muslim-majority and Hindu-majority places. With the logic of political rule the marker of Hindustan, the space of the subcontinent was fractured into particular territorial claims and slowly the pink hue of the British East India Company maps crept up to swallow all of the subcontinent. All of the complex ways of being in space, belonging to a place, were reduced to a cartographic certainty of control. The map emerged as the most robust truth, the ontologically secure representation of what was British India. The other ways of description, the relations between people and place, were grimly wiped out. By the end of the nineteenth century, there was no Hindustan to be located on any map, and no text, no monument, could stand and attest to its once-there-ness.

It is thus uncanny to read Firishta. His history is organized as a geography of a Hindustan that stretched from west to east, north to south, with the Deccan at the center. He notes at the beginning that when prompted to write a history, he looked to gather “the histories of various kings and countries of Hindustan.” Unlike many of his predecessors and contemporaries, his history is not organized as a genealogy of kings, but around the vast spaces that make up Hindustan. Firishta is not writing for a court that claims ownership of Hindustan, but a universal history that he clearly imagines to be constituted through his location, the Deccan. While he is in conversation with imperial Mughal histories, and with an intellectual genealogy that came before him, he is most committed to his own expertise in depicting the whole of Hindustan’s historical geography. As shown in Chapter 3, Firishta develops a philosophy of history that incorporates and extends the history and geographies from the Mahabharata to the Shahnama.

Firishta’s history is organized in a particular spatial order. The text has a prologue, twelve chapters, and a short conclusion. Each of the twelve chapters tells us of polities in a particular geography in the vast subcontinent. Firishta starts with polities in the Northwest, moves to the southern center, travels up to the eastern shores, and returns again to the South by the ocean—Lahore, Delhi, the Deccan, Gujarat, Malwa, Khandesh, Bengal, Multan, Sindh, Kashmir, Malabar. He expresses his love for this geography in the conclusion, titled “An Account of Conditions of the Heaven- Representing Hindustan,” where he narrates the diversity and expansiveness of this geography.

The nineteenth-century colonial obsession of carving out the territory of the subcontinent into domains of political control and resource extraction, of treaties and recognitions of indirect rule, remains starkly clear in the themes of the histories they produced, the archives they assembled, and the people they enslaved… The map emerged as the most robust truth, the ontologically secure representation of what was British India. The other ways of description, the relations between people and place, were grimly wiped out. By the end of the nineteenth century, there was no Hindustan to be located on any map, and no text, no monument, could stand and attest to its once-there-ness.

Firishta’s Hindustan is constituted first by multiple dominions, and then by cities. He gives specific origins to these dominions, providing a notion of sacral and political power in these spaces, and their relationships to each other. Hindustan already had an extensive corpus of historical narratives for each of the “regions,” imagined as polities or cities. Firishta relied on such histories and accounts for his own work—citing and using pre-existing regional histories for some of these spaces, but Firishta makes an effort to organize such pre-existing spaces into discrete historical places. He gives each of these spaces a chronology, an ethics, a set of actors, and multiple stories in order to assimilate these spaces into a unified history of Hindustan. The places described in time and across geography, collectively, make up Firishta’s Hindustan. Firishta’s invention was to give this Hindustan a universal history that reflected a diversity of cosmological political claims.

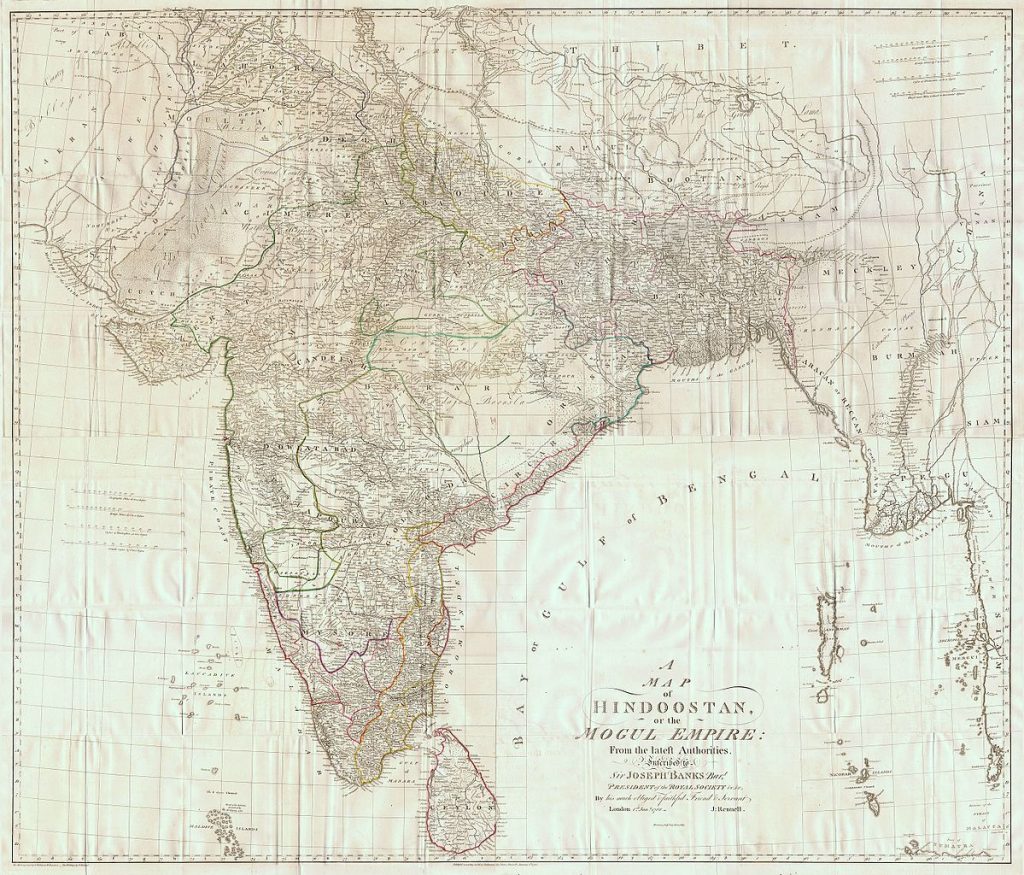

‘A Map of Hindoostan or the Mogul Empire’, by James Rennell, published in 1788, dedicated to Joseph Banks

Firishta’s Hindustan had a deep past and an immediate political present. The present, in the early seventeenth century, was the dominant Mughal imperium toward which European embassies, merchants, missionaries, and travelers were flocking. The Mughals, of course, had adopted and used the label of the kings of Hindustan since Babur in the early sixteenth century. This identification, paradoxically, did not shrink the conceptual boundaries of Hindustan to the political boundaries of the Mughal dominion. That Firishta was writing a history of Hindustan in the Deccan, outside of Mughal rule, specifically means that Hindustan was greater than the Mughal court. Firishta’s Hindustan reflected the broader political and cultural landscape of the subcontinent that was firmly present in the seventeenth century.

The making of the subcontinent as Hindustan is a political and cultural process stretching across nearly a millennium. It happened in textual representations, in legal and liturgical forms, in titular conventions; it was deployed and used by a wide variety of the people of the subcontinent. Firishta had inherited the idea of a multi-polity Hindustan with the Deccan holding a prominent position. Firishta quotes a chronogram composed by his father, Ghulam Ali Hindushah, in a year when three kings of Hindustan died, which gives us a sense of how Hindustan was imagined in the sixteenth century:

Three kings expired at one time

By these just kings, Hind was a place of peace

One, Mahmud the king of kings of Gujarat

who was as young as his fortune

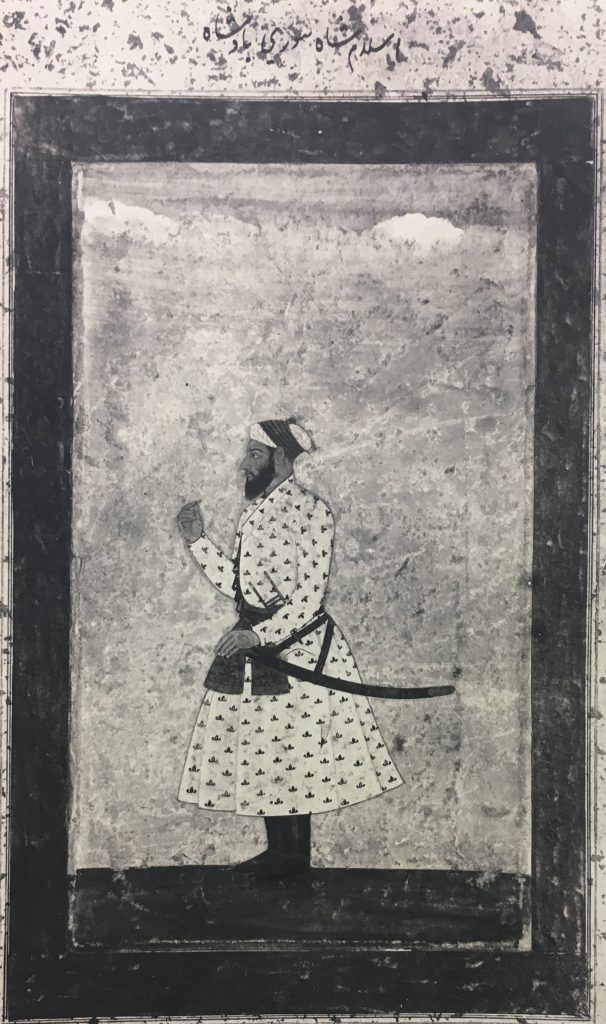

Second, Islam Shah [Suri] the sultan of Delhi

In Hindustan, he was the master of felicity

Third was Nizam Shah Bahri [Ahmednagar]

Who held the royal insignia of the country of Deccan

Why do you ask me of the date of the death of these

Three kings?

It was “Fall of the Kings.” (961 AH/1553–1554)

The three kings, in Delhi, in Gujarat, and in the Deccan, all belong to places within Hindustan.

Islam Shah Suri: “the sultan of Delhi”

Today in the subcontinent, Hindustan is colloquially understood as a synecdoche for a particular set of customary practices tied to north Indian languages, or as an attitude toward interfaith relations and social decorum—“the Hindustani civilization” (Ganga-Yamuni tahzib). Yet today’s colloquial understanding is not the history of Hindustan as a political and historical entity that endured for centuries. The Hindustan evoked in the titles of kings or in histories and treatises was a geographic, social, and cultural construct. That Hindustan created a public, an affect, a desire, a set of characteristics—in territory and in the individual self. It is that particular history of Hindustan as a political geography that is erased analytically by the substitution of “India” to represent the medieval and early modern subcontinent.

Today’s colloquial understanding is not the history of Hindustan as a political and historical entity that endured for centuries. The Hindustan evoked in the titles of kings or in histories and treatises was a geographic, social, and cultural construct. That Hindustan created a public, an affect, a desire, a set of characteristics—in territory and in the individual self. It is that particular history of Hindustan as a political geography that is erased analytically by the substitution of “India” to represent the medieval and early modern subcontinent.

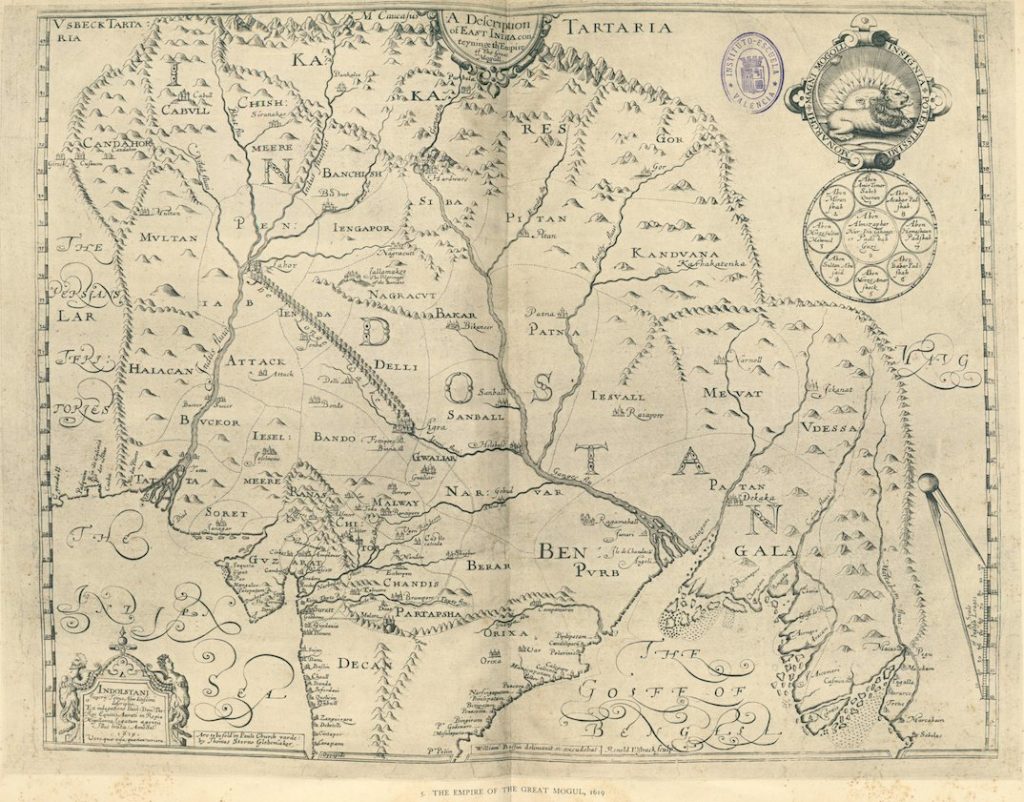

‘Indostan’, the first cartographic representation of Hindustan in England

The erasure of Hindustan as a political concept began with the European arrival to the subcontinent. India, the East Indies, or Indostan was, of course, known to Europeans; the quest for it, its imagined riches, propelled both Christopher Columbus and Vasco de Gama. This India of wonders and wealth was a space that attracted Portuguese settlements and Dutch factories. It was where the Jesuit missionaries and priests flocked—to the land of a small band of Christians, the reputed followers of St. Thomas the Apostle, living among “faithless” people. It was India, whose ports like Diu, and Surat, were to be controlled or burned down.

Lto R: Vasco de Gama; Christopher Columbus

Throughout the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, the imagined riches and curiosities, the miracles and mystiques persisted despite repeated and extensive encounters of Europeans with the sub-continent. The European project engaged in its own task of describing the geography of Hindustan, breaking it down, extracting riches, and finally surveying and mapping it back into a whole, finally named, British India. The maps of British India, deemed scientific, framed the subcontinent solely in relation to its land as an expanding colonial project.

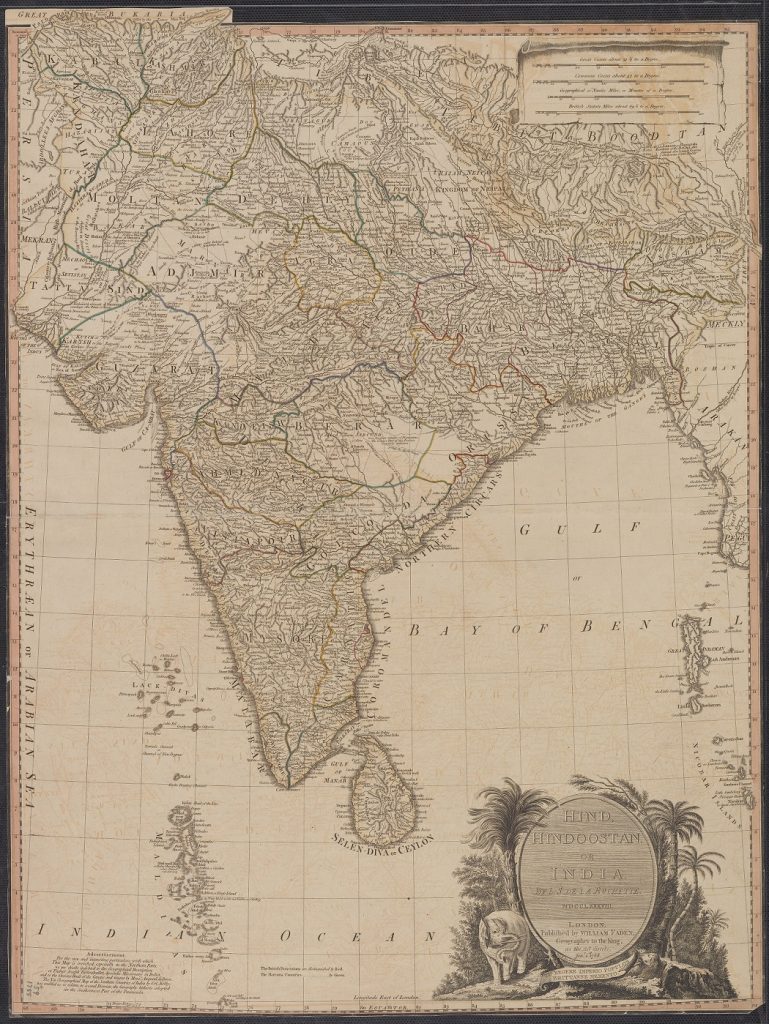

Louis Delarochette’s 1788 map “Hind, Hindoostan, or India” published by William Faden

I begin this chapter with the ways in which Hindustan was seen by European—largely English—visitors. They labeled Hindustan the “East Indies” or “Grand Mogor”— sometimes “Hindoostan”—but ultimately “British India.” My interest, in this first section, is to present what the British saw as their experience and knowledge of the geography of the subcontinent. In essence, the British military conquests of subcontinental territories were intimately tied to the cartographic representations of the subcontinent. I then move to some of the key historians who wrote about the space of Hindustan prior to the seventeenth century. In these histories, we find a Hindustan that is the center of the world, a heavenly geography. The third section focuses on Firishta’s history and examines his engagement with the space of Hindustan. I focus on Firishta’s novel use of multiple cosmologies and histories to discuss the natural and political landscape.

A series of transitions was taking place in the sixteenth century in the ways in which the subcontinent was perceived by Europeans: from the earliest sources of information in Greek to Latinate Roman accounts of “Peninsula Indiæ,” to the Portuguese, Dutch, French, and English renderings. The first transition came with the introduction of the eyewitness traveler, the first-person testimonial, the European sailor, merchant, diplomat, or missionary who physically traverses the landscape of the subcontinent and describes it in detail for the audiences in the metropole.

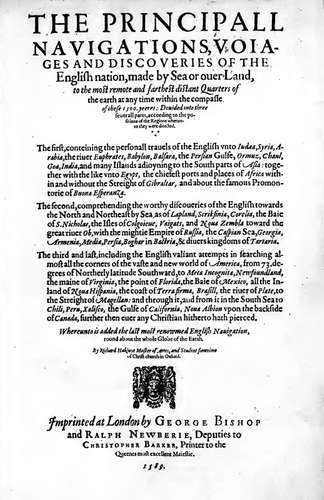

The Principal Navigations, Voyages and Discoveries of the English Nation by Richard Hakluyt

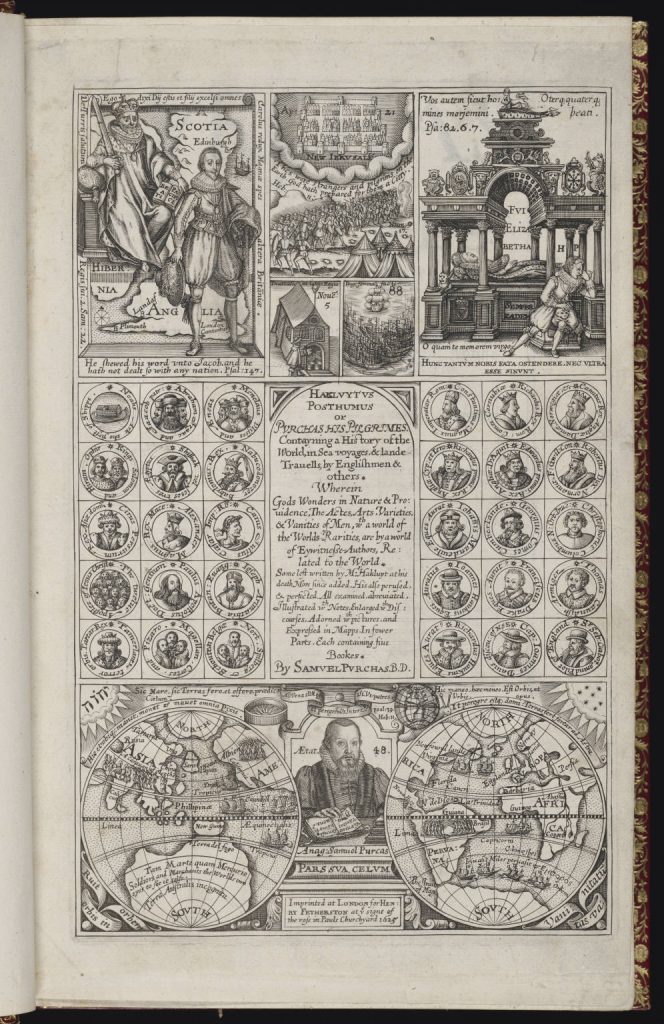

The earliest European gaze saw the subcontinent as a series of political forms, divided between Muhammadans and Gentiles, and with Akbar—the one possessing the most wealth, the most power—as a key ruler. This is in contrast to the ways in which the European colonial gaze had described the Americas as terra nullius. Collected in the compendiums of Richard Hakluyt’s The Principal Navigations, Voyages and Discoveries of the English Nation (1598) and its successor, Samuel Purchas’s Hakluyt Posthumous, or Purchas His Pilgrims (first edition 1613, fourth completed edition 1626), are scores of authors and travelers whose accounts describe the lands and peoples of the “East Indies” or the “Grand Mogols.” Hakluyt’s text contained both English accounts and others translated from Portuguese, Italian, and German in order to give a territory to the colonizable worlds. In these early accounts, the geography of the subcontinent begins at its sea limit, and it is described from the port cities inland. The information provided (or noted) tends to favor travel routes, market details, customs of trade, and natural and artisanal products—everything from diamonds and pepper to ivory bangles. The places described—Goa most frequently, but also Daman, Calicut, Vijayanagar, and Bijapur —are first noted for their markets and then for their political realm, and finally for their, often termed barbaric, customs.

Hakluyt Posthumous or Purchas His Pilgrims by Samuel Purchas

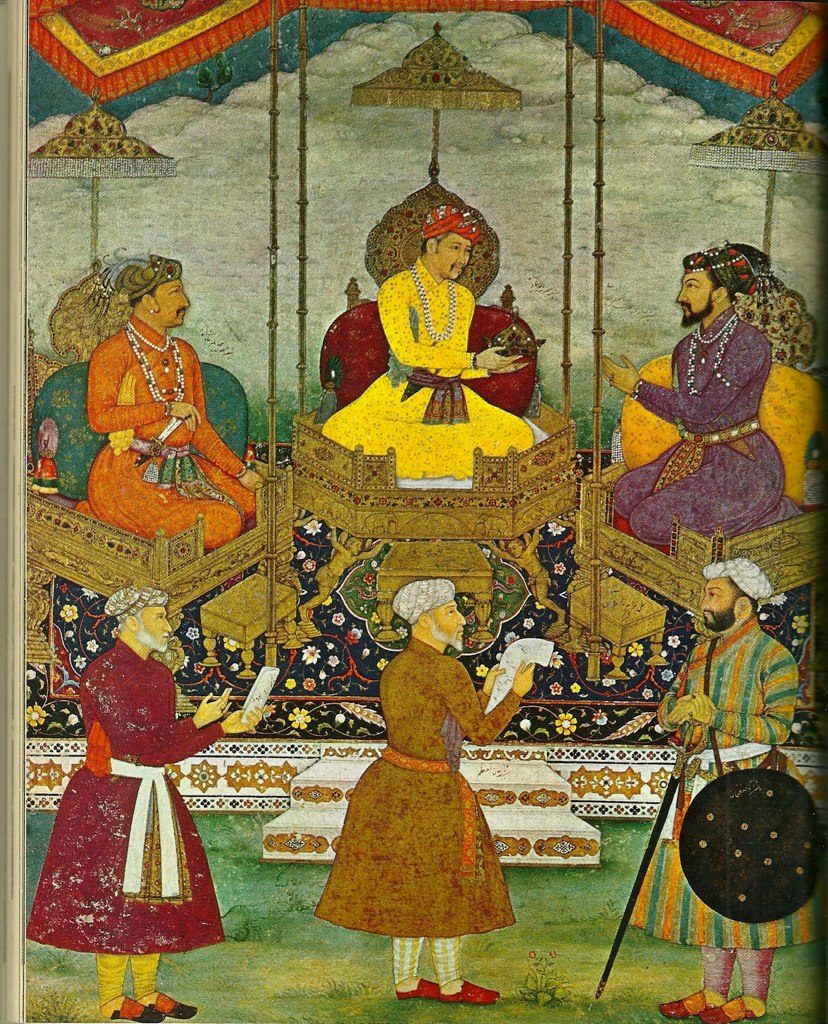

The earliest European gaze saw the subcontinent as a series of political forms, divided between Muhammadans and Gentiles, and with Akbar—the one possessing the most wealth, the most power—as a key ruler. This is in contrast to the ways in which the European colonial gaze had described the Americas as terra nullius.

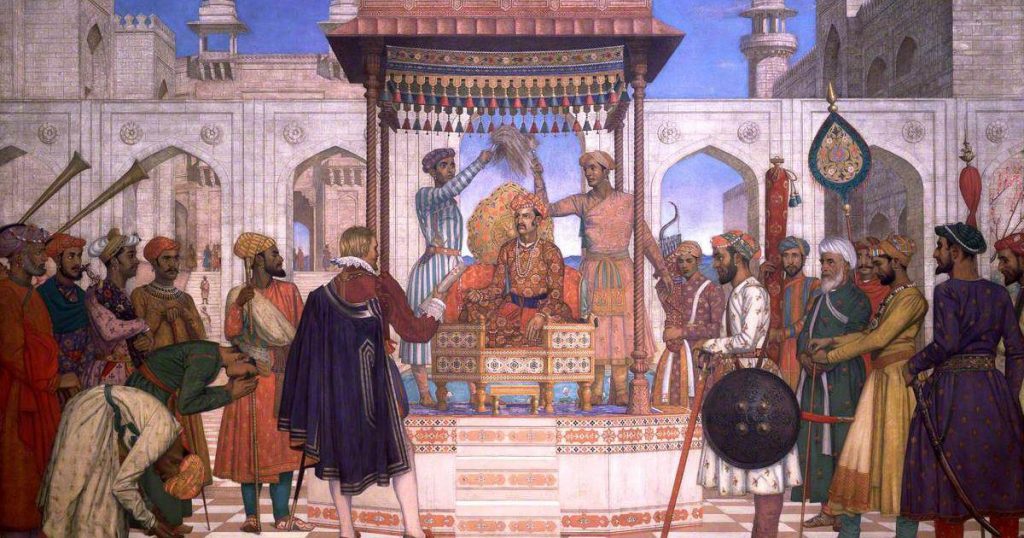

Jalaluddin Akbar “The great Mogor”

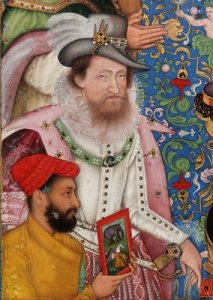

An exemplar of the myriad ways of imagining the subcontinent is in Hakluyt’s account of M. Ralph Fitch, a merchant who travels, with M. John Newberie, from London to “all the kingdome of Zelabdim Echebar the great Mogor” and back between 1583 and 1591. Fitch’s itinerary reflects what would have been a typical route for a merchant in the late sixteenth century who traveled from London to the subcontinent and back. We see the port of entry (Gujarat on the Indian Ocean) as well as the main cities and regions traversed within the subcontinent. The itinerary moves from the western shores into the Deccan plain, up to the Gangetic plains, follows the Ganges river to Bengal, goes up to Burma, then back down via Orissa to Cochin and to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) before returning to the starting point of Goa. The route he takes is: London, Tripoli, Aleppo, Birra, Babylon, Felugia, Basora (Basra), Ormus (Hormuz), Diu, Daman, Basaim (Vasai), Tana (Thana), Chaul, Goa, Bellergan (Belgaum), Bisapor (Bijapur), Gulconda, Masulipatam, Servidore, Bellapore (Balapur), Barrampore (Burhanpur), Mandoway (Mandogarh), Ugini (Ujjain), Serringe (Sironji), Agra, Fatepore, Prage (Allahabad), Bannaras, Patenaw (Patna), Tanda, Cacchegate, Hugeli, Angeli, Satagam (Satgaon), Bottia, Chatigan (Chittagong), Bacola, Serrapore (Serampur), Cosmin, Medon, Dela, Cirion (Syriam), Macao, Pegu, Jamahey, Malaca, Cosmin, Cochin, Ceylon, Cochin, Goa, Chaul, Ormus, Basora, Babylon, Mosul, Medin, Orfa (Urfa), Birra, Aleppo, Tripoli, and London.

In Fitch’s travels, the triangle of the subcontinent, starting from Diu, is formed, in order of appearance, by the political “countreys” of the Portuguese, the Adil Shahi (Hidalcan), the country of Zelabdim Echebar (Jalaluddin Akbar) out to Bengal, and Burma, where there are many countries ruled by “Gentiles.” At each stop on his itinerary, Fitch discusses the political rule, the wondrous elements, and the material or mercantile resources. The entry for Bijapur gives us a good sense of this political geography:

One of the first towns which we came unto, is called Bellergan, where there is a great market kept of Diamonds, Rubies, Saphires, and many other soft stones. From Bellergan we went to Bisapor which is a very great town where the king doeth keep his court. He hath many Gentiles in his court and they be great idolaters. And they have their idols standing in the Woods, which they call Pagodes. Some be like a Cow, some like a Monkey, some like Buffaloes, some like peacockes, and some like the devil. Here be very many elephants which they go to war with. Here they have good store of gold and silver: their houses are of stone very fair and high. From hence we went for Gulconda, the king whereof is called Cutup de lashach [Abdullah Qutb Shah]. Here and in the kingdom of Hidalcan [ʿAdil Shah], and in the country of the king of Deccan be the Diamonds found of the old water. It is a very fair town, pleasant, with fair houses of brick and timber, it aboundeth with great store of fruits and fresh water. Here the men and the women do go with a cloth bound about their middles without any more apparel. We found it here very hot.

M. Ralph Fitch

What Fitch notes, or annotates, are deities and riches—a template of seeing wonders and marvels in the landscape of Hindustan. When Fitch enters the Mughal realm, he announces its grandeurs, and presents Akbar as one among the great kings:

From thence we went to Agra passing many rivers, which by reason of the rain were so swollen, that we waded and swam oftentimes for our lives. Agra is a very great city and populous, built with stone, having fair and large streets, with a fair river running by it, which falleth into the gulf of Bengala. It hath a fair castle and a strong with a very fair ditch. Here be many Moores and Gentiles, the king is called Zelabdim Echebar [Akbar]: the people for the most part call him The great Mogor.

In Fitch’s travels, the triangle of the subcontinent, starting from Diu, is formed, in order of appearance, by the political “countreys” of the Portuguese, the Adil Shahi (Hidalcan), the country of Zelabdim Echebar (Jalaluddin Akbar) out to Bengal, and Burma, where there are many countries ruled by “Gentiles.” At each stop on his itinerary, Fitch discusses the political rule, the wondrous elements, and the material or mercantile resources… What Fitch notes, or annotates, are deities and riches—a template of seeing wonders and marvels in the landscape of Hindustan. When Fitch enters the Mughal realm, he announces its grandeurs, and presents Akbar as one among the great kings.

Just a short while after Fitch, William Hawkins landed in Surat in 1605, traveled to Agra, and left for England in 1608. His account is included in the Hakluytus Posthmus or Purchas His Pilgrimes by Samuel Purchas in 1625. Hawkins ends with “a brief discourse of the strength, wealth and government, with some customs of the Great Mogol.” For Hawkins, political power defines the geography of the subcontinent. In other words, his was an account principally of Mughal dominions. For him, Hindustan was the kingdom of the Mughals, with Agra at its center: “The compass of his country is two years travel with Carrauan, to say, from Candahar to Agra, from Soughtare to Agra, from Tatta in Sinde to Agra. Agra is in a manner in the heart of all his Kingdomes.”

Thomas Roe

In contrast to Fitch, Hawkins’s geography centers around the Mughal court—Agra is the “heart,” a space labeled as “Great Mogol.” The accounts of the Mughal king, built on the wide success and circulation of Hakluyt and Purchas, add to the immediate urgency and luster of one of the most significant political journeys to the subcontinent: Thomas Roe’s embassy to Jahangir’s court in 1615. To his narrative account of the Mughal realms, Roe added a geographical note on the “Mogul’s territories.” Roe reported that he gathered the information about the “Seuerall Kingdomes and Prouinces Subiect to the Great Mogoll Sha-Selim Gehangier [Jahangir]” from “the Kings Register.”

Roe begins his listing of the countries from the Northwest: Candahar, Tata (Thatta), Buckar (Bhakkar), Multan, Haagickan, Cabull (Kabul), Kyshmier (Kashmir), Bankish, Atack, Kakares, Pen-Jab (Punjab), Jenba, Peitan, Nakarkutt, Syba, Jesvall, Delly (Delhi), Meuat (Mewat), Sanball, Bakar (Bikaner), Agra, Jenupar, Bando, Patna, Gor, Bengala, Roch, Vdeza, Kanduana, Kualiar (Gwalior), Ckandes (Khandesh), Malva, Berar, Guzratt, Sorett, Naruar, and Chytor (Chitor). Agra is the “hart of the Mogolles territorye,” and the road from Lahore to Agra is “one of the great woorkes and woonders of the world.” For the British, the Mughal imperium became the central object of attention, and their political realms were properly situated and understood as part of the “East Indies.”

The first transition in the European narratives, such as those of Fitch above, is that the “first-person” account of their travels in the subcontinent begins to take priority over the abstract geographies from Greek or Roman sources. While many of these accounts continue to reference the Latinate canon—the import of wonders and marvels and the modes of description—the newness comes from the very personhood of the writer. His authority derives from his experiences “walking the landscape,” “speaking to the people,” and “seeing the place.”

The second transition was the inclusion of local knowledge, first incorporated as oral reports, and then more authoritatively as “translations” from local sources. Roe introduced this convention by linking to the authority of the Mughal king himself in using the “King’s Register” for his listing of the dominions. The “King’s Register” would later be understood as Abuʾl Fazl’s Aʾin-i Akbari (ca. 1595). This was a compendium of places, customs, and traditions of Hindustan that was appended to Abuʾl Fazl’s history of the Mughal kings Akbarnama. The Aʾin had been rendered into English, in bits and pieces, by Francis Gladwin since 1777, and it was finally published in 1783. By then, the descriptions of place names and spaces from Roe’s account were canonical.

The first transition in the European narratives, such as those of Fitch above, is that the “first-person” account of their travels in the subcontinent begins to take priority over the abstract geographies from Greek or Roman sources… The second transition was the inclusion of local knowledge, first incorporated as oral reports, and then more authoritatively as “translations” from local sources.

Thomas Roe’s embassy to Jahangir’s court in 1615

The colonial efforts at mapmaking relied on these two foundations: the colonial agent who walked, described, and wrote the subcontinent; and sources of geographical information that could be translated and rendered into cartographies. In the European imagination, the geography of the whole of Hindustan began to be the geography of colonial dominions and their relationship to the Mughal polity. Roe’s account was the basis for the first British map of Hindustan, produced by William Baffin, in 1619, “A Description of East India conteyninge th’Empire of the Great Mogoll.” The map is labeled “Indolstani.” The map reproduced almost all of the territories and kingdoms mentioned by Roe, but with the Deccan—while represented—as an empty space. The authority of Roe’s account and Baffin’s map became enshrined in the public imagination with their inclusion in the influential and widely circulating Purchas His Pilgrimes. With Baffin’s map, the efforts of colonial map makers became focused on seeking more travel accounts and further translations of Sanskrit or Persian texts in order to construct better and more detailed maps of the subcontinent.

The map emerged in the early seventeenth century as, analytically, the most powerful instrument of colonization. It was a representative medium, and an aspirational visual, for European power in the subcontinent. The cartouche, the colorization, the “filled in” spaces as well as the terra nullis, were ideological tools for the enactment of European territorial expansion. The map was among the first and most vital instruments of colonialism.

Louis Delarochette’s 1788 map “Hind, Hindoostan, or India”—published by William Faden—captures the many modes of British representation of the subcontinent at a pivotal moment in time. The map bears the legend “Tu Regere Imperio Populos Brittanne Memento” (You, O Britain, govern the nations with your power, remember this), adapted from Virgil’s plea to the Romans in the Aeneid. It carries a note for how to think spatially about the subcontinent: “NB. Hindoostan is comprehended under Two General Divisions viz. Hindoostan (proper) to the North of the River Nerbudda and Decan to the South of that River.”

The equivalence drawn in the cartouche between “Hind, Hindoostan, or India” gestures to the many textual traditions that are feeding the spatial representation. The map’s “Advertisement” carries the texts being used: “For the new and interesting particulars with which This Map is enriched, especially in the Northern Parts, we are chiefly indebted to the Geographical Description of Father Joseph Tieffenthaller, Apostolic Missionary in India, and to the Curious Draft of the Ganges and Gagra by Mons. Anquetil du Perron.” Not mentioned or cited in the copy are the Arabic and Persian historical texts inscribed into the very fabric of the territory: “Attock R. According to the Ayin Acbarri,” “Minhaûareh afterwards al Mansura according to Abu Rihan al Biruni,” and so on. The Jesuit missionary Joseph Tieffenthaller’s account was translated by M. Jean Bernoulli in 1786 alongside the works of Anquetil du Perron and James Rennell on the description of “l’Indoustan.”

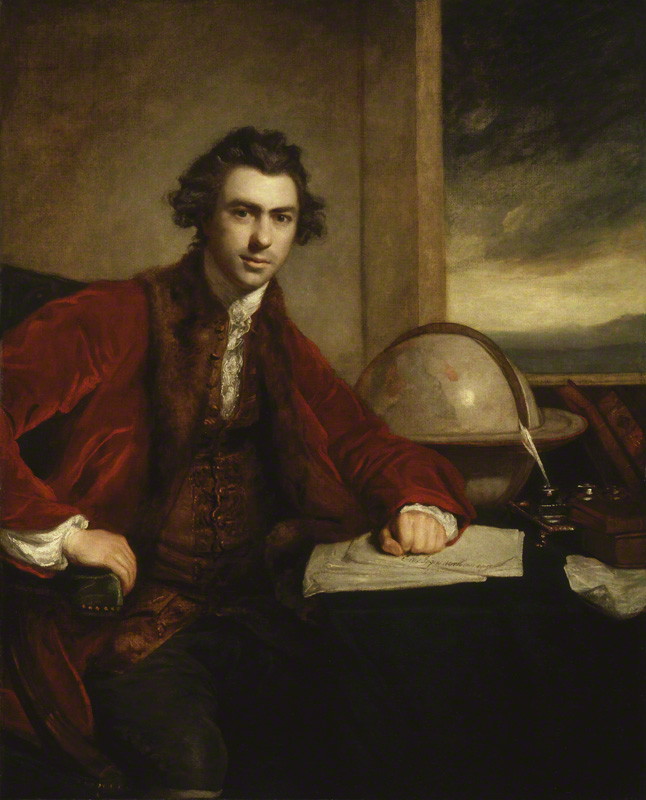

James Rennell

The map emerged in the early seventeenth century as, analytically, the most powerful instrument of colonization. It was a representative medium, and an aspirational visual, for European power in the subcontinent. The cartouche, the colorization, the “filled in” spaces as well as the terra nullis, were ideological tools for the enactment of European territorial expansion.

Baffin’s map based on Roe’s account, and Delarochette’s map based on Tieffenthaller and du Perron’s accounts represent a flattened visualization of a territory that comes with a godlike perspective. Yet, there is another crucial act of knowing that goes missing from the text to the map: the specific ordering of the geography of Hindustan from textual sources like Fitch’s itinerary or Roe’s geography—an ordering that, in text, had created a specific path through which to traverse the territory. Tieffenthaller, though coming a hundred and fifty years after Roe, maintains the specific order in which he walks the subcontinent: Kaboul, Kandahar, Cachemire, Lahor, Moultan, Tatta, Delhi, Agra, l’Elhabad, d’Oude, d’Adjmer, Malva, Barar, Chandess, Guzarate, Behar, Bengale, d’Oressa, d’Aurengabad, Bhalagate, Safarabad ou de Bedor, d’Hederabad, and Bedjapour. This particular ordering, like Roe’s, begins from the Northwest, goes south to Sindh, then to the Gangetic plains, back to western Ghats, then to Bengal, and finally to the Deccan. The ordering privileges one particular form of thinking about the subcontinent—the Mughal perspective.

The movements of the travelers from Europe to the subcontinent—from Fitch onward—were shaped by the sea and the vagaries of those controlling passages across the subcontinent. The maps produced from those textual renderings of place could not incorporate the ordering, but they did incorporate the particular biases, the gaze that looked for wonder or marvel or horror. Delarouchette labels “the Beels a Wild Nation of Robbers,” “Village of Robbers,” “Bhoodie where they adore a Serpent,” “the Khands a wild people,” “Rettenpour Wild People,” “subterraneous caves out of which issue Fire, Wind, and Water,” the “Diamond Mines,” and much else in translating the accounts of Tieffenthaller and du Perron into the cartographic.

In the 1780s, the effort to create a cartographic representation of British India to match the empire that was emerging in the territory was in full swing. James Rennell was appointed surveyor-general in Bengal by Robert Clive and created the Bengal Atlas, which served as the basis of British administration. He also published the first general map of Hindoostan in 1782, with revisions in 1788 and 1791. He would go on to publish a history of his mapmaking endeavor. Rennell’s Memoir of a Map of Hindoostan or the Mogul Empire, published in 1788, was dedicated to Joseph Banks, colonialist and president of the Royal Society and African Society, and labeled an “attempt to improve the geography of India, and the Neighboring Countries.”

Joseph Banks

British India is ascendant and hegemonic in Rennell’s account: “The Mogul empire was now become merely nominal: and the emperors must in future be regarded as of no political consequence.” Rennell introduces the space of the subcontinent thusly: “Hindoostan, has by the people of modern Europe, been understood to mean the tract situated between the rivers Ganges and Indus, on the east and west; the Thibetian and Tartarian mountains, on the north; and the sea on the south.” This, he argues, is “a lax sense,” and for the subcontinent “it may be necessary to distinguish the northern part of it, by the name of Hindustan proper.”

To define this Hindustan, Rennell looks to the works of history: “There is no known history of Hindoostan (that rests on the foundation of Hindoo materials or records) extant, before the period of the Mahomedan conquests: for either the Hindoos kept no regular histories; or they were all destroyed, or secluded from common eyes by the Pundits.” Their histories, even if they had written them, would not amount to much, for they would have

contained nothing more than that of Mahomedan conquests; that is, an account of the battles and massacres, an account of the subversion of (apparently) one of the mildest and most regular governments in the world, by the vilest and most unworthy of all conquerors: for such the Mohamedans undoubtedly were, considered either in respect to their intolerant principles; contempt of learning, and science, habitual sloth; or their imperious treatment of women: to whose lot, in civilized societies, it chiefly falls to form the minds of the rising generations of both sexes; as far as early lessons of virtue and morality may be supposed to influence them.

The movements of the travelers from Europe to the subcontinent—from Fitch onward—were shaped by the sea and the vagaries of those controlling passages across the subcontinent. The maps produced from those textual renderings of place could not incorporate the ordering, but they did incorporate the particular biases, the gaze that looked for wonder or marvel or horror.

As already argued, Rennell’s portrayal of the Muslim conquerors as despotic rulers and the invocation of the plight of women were two emerging, and soon to be dominant, tropes within British depictions of subcontinental politics and society.

Yet, Rennell saw value in the Persian histories, for they still had a geography embedded in them that Rennell could cull for his scientific mapping project. In order to do so, Rennell turns to Firishta:

It is chiefly to Persian pens that we are indebted for that portion of Indian history, which we possess. The celebrated Mahomed Ferishta, early in the 17th century, compiled a history of Hindoostan, from various materials; much of which, in the idea of Col. Dow (who gave a translation to the world, about 20 years ago) were collected from Persian authors.

While Rennell praises Firishta and uses him extensively for resolving place names, his cartouche confirms his prejudicial eye toward the Muslim rulers and their knowledge systems. It depicts Brahmins bowing and presenting an envelope labeled “Shaſter” (Shastra) to Brittannia.

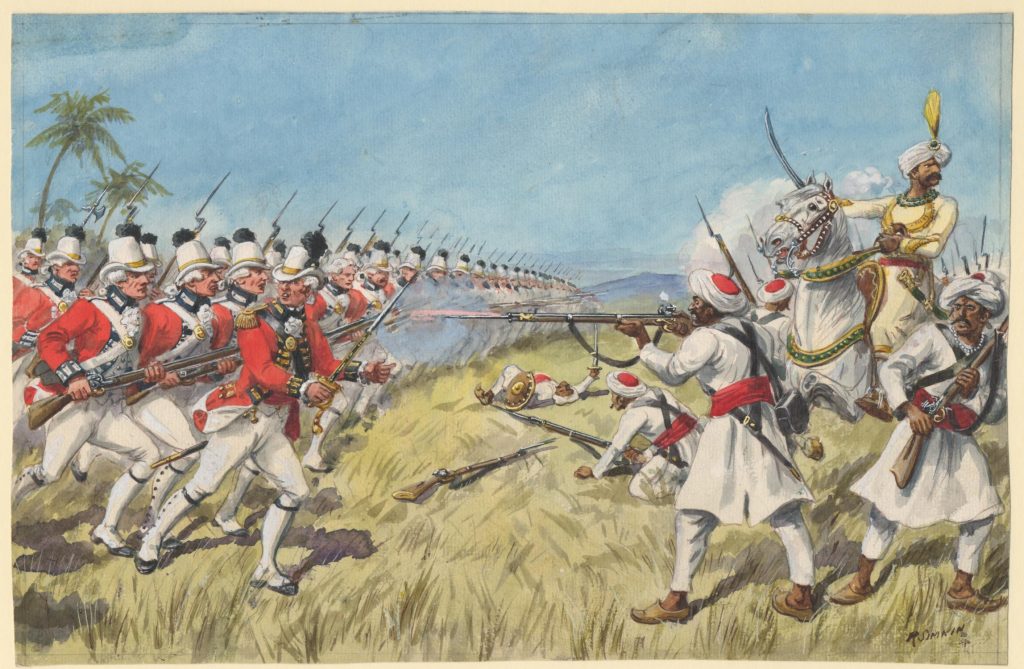

The Battle of Assaye, from the Second Anglo-Maratha war

Rennell relies specifically on Firishta for the history of the Maratha polity with which the British East India Company was engaged in active warfare at that time. Firishta was one among several key sources used by Rennell to make his map. The war itself was one key source of information for the map. Rennell credits the “war with Hyder Ally and Tipoo Sultan,” which provided information through “the marches of different armies.” There was also the information from Ayin Acbaree (ʿAin-i Akbari) through an earlier, piecemeal rendering by Boughton Rouse and then by Francis Gladwin. Then there were the letters from various military attachés and travelers such as du Perron. Despite these sources, much of the middle of the subcontinent and some of the Northwest is empty in Rennell’s map—labeled “little known to Europeans,” while the parts colored in pink are denoted as “British Possessions.”

The Siege Of Cuddalore from the Second Anglo-Mysore War (the British against “Hyder Ally and Tipoo Sultan”)

British colonialism, after sketching out the various countries of the Mughals, turned swiftly to marking out the cartography of British India. The Persian sources—from Abuʾl Fazl to Firishta—that had played a significant role from the sixteenth to the late eighteenth centuries, vanished by the early decades of the nineteenth century. No longer were histories of Hindustan required for their place-names or facts. Their accounts were replaced by the data collected by the colonial geographer (and his “native help”) on the ground in the science of the “Great Trigonometric Survey.”

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of Manan Ahmed Asif and Harper Collins India. You can buy The Loss of Hindustan – The Invention of India here.

Manan Ahmed Asif, Associate Professor at Columbia University, is a historian of South Asia and the littoral western Indian Ocean world from 1000-1800 CE. His areas of specialization include intellectual history in South and Southeast Asia; critical philosophy of history, colonial and anti-colonial thought. He is interested in how modern and pre-modern historical narratives create understandings of places, communities, and intellectual genealogies for their readers. He has written the books The Loss of Hindustan: The Invention of India, A Book of Conquest: The Chachnama and Muslim Origins in South Asia and Where the Wild Frontiers Are: Pakistan and the American Imagination. He is also the founder of the blog Chapati Mystery which explores “the histories and cultures of Hindustan”, and co-founder of Columbia’s Group for Experimental Methods in Humanistic Research. You can read more about him and his work here.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply