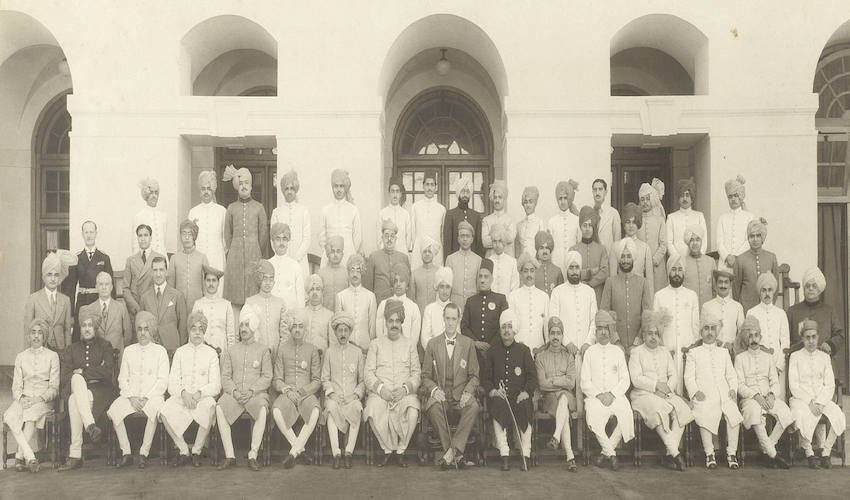

Chamber of Princes (17 March, 1941)

“Some work of noble note, may yet be done,

Not unbecoming men [or women] that strove with Gods.”

Historiography, or the methods employed by historians to develop history as a discipline, through the ages, has often led to the creation of pantheons. This is not entirely the historian’s fault. The writer of any narrative requires a peg to hang a story on, and history is a narrative. While many (especially recent) historiographies strive, pointedly, to shift the focus away from individuals, ‘people’ simply make for more relatable storytelling. Hence, the pantheon; especially in popular historical narratives.

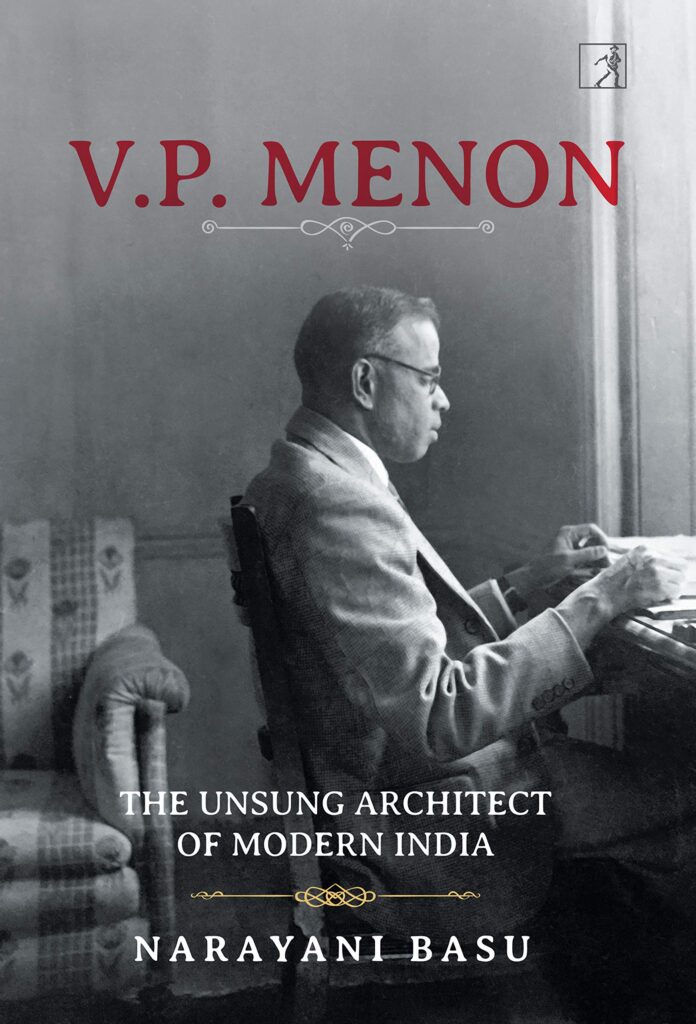

One way to look beyond the pantheons of popular historical discourse (for while they may be illuminating for a while they can also be severely limiting) is to relook at its figures with a fresh, or more probing, lens to develop more nuanced perspectives (this is what Tripurdaman Singh and Adeel Hussain have attempted in their book Nehru: The Debates that Defined India; you can read our excerpt). Another, is what Narayani Basu has done in V. P. Menon: The Unsung Architect of Modern India: after pinpointing decisive moments in time you look around the pantheon to locate the movers and shakers it overshadows.

Menon was Basu’s great-grandfather but, as she puts it, “that is not why I wrote the book”. He was also Reforms Commissioner to India’s last three Viceroys. And as Secretary, States Ministry, he was Vallabhbhai Patel’s right hand, “coaxing, cajoling and coercing Princes across India to accede to the Union of India”. To quote Basu again, “He drafted the Plan that would play midwife to India’s birth as a free nation.”

This is one reason why, on the eve of India’s 75th year of independence we have chosen to republish two chapters from the book below. But it is not the only reason. The two chapters, titled ‘Instrument of Execution’ and ‘Endgame’ deal with a critical aspect of the long drawn process that was ‘Indian’ independence (while Nehru’s “stroke of the midnight hour” might have underlined our moment of freedom, independence is always a process, not a point): the accession of the princely states to form the union of India that we have come to know and recognise today. As Basu writes, princely India at its peak, “spread over an acreage of half-a-million square miles” and “were home to nearly a quarter of India’s 300 million population”. To not have them accede to the Union would necessarily mean balkanisation.

Much has been written about this, including by Menon himself in his book The Story of the Integration of Indian States. Chapters tracing — with delightful anecdotes and insight — the quest for the “full basket of apples”, that Patel asked Viceroy Mountbatten for, exist in Ramchandra Guha’s India After Gandhi as well as Alex Von Tunzelmann’s Indian Summer. What Basu’s book highlights, however, besides the contribution of unsung architects like Menon and Sir N. Gopalaswamy Ayyangar (another figure that, according to Basu, “has been allowed to lapse into the shadow”), is the pragmatic politics at play (‘Saam, Daam, Bhed, Dand’, if you will), to ensure the welding together of the nation that we celebrate today. More specifically, it reveals how much of this politics, like God or the devil, lay in the details, or the fineprint. This is why we must swivel the spotlight on the shadows of those who produce them— to turn the fineprint of history bold.

For instance, Basu writes, “Patel and VP [Menon] had to convince Mountbatten — no arduous task — that their plan [the accession of the states] was actually his plan. At different points that summer, then, the Viceroy was told deferentially that the only way history could move forward was if he played his part. It worked a little too well.” They both knew that the plan would work only “if the Viceroy was not just on board, but was its ambassador”.

Or, to cite another example of the diligent maneuvering that has been swallowed by the shadows, the difference between the stance Menon took with the Maharaja of Patiala (“I told him frankly that independent of us, you cannot exist.”) and the Dewan of Travancore: “I assured him of my high regard for both his realistic attitude to affairs and for the part he had played in the past. It ought not to be said of him that at India’s critical hour, he had not made his contribution towards building a united India when he had it in his power to do so.”

Finally, writes Basu, “it was the ceremonial pomp of the Chamber of Princes that would seal the deal”, where the princes’ eyes would be fixed on Mountbatten, “their herdsman— who was about to tell them the best way to the abattoir” (Ann Morrow).

On the eve of India’s 75th, read this compelling story of the birth of a nation. Know that, for every giant of history historians produce, there are those whose shoulders the giant stands upon.

“Before sunset, there is at times a mellow glow,” wrote Narendra, Raja of Sarila, wistfully. “Princely India in the 1930s and 1940s was bathed in such radiance …” The Princes of India were a fascinating study in eccentricity. They were hedonistic, imperious and flamboyant. Some ruled States the size of Germany, others lorded it over tiny specks the size of pocket-handkerchiefs. The last decade of the Raj was halcyon in their memories. Nearly every ruler remembers armies of retainers, solid gold plates at dinner, chukkas of polo, jewels by Cartier and coffers overflowing with diamonds, rubies, emeralds and gold. They had been, for the most part, willing vassals of the British.

However, one step out of line and a swift reprimand followed. Their choice of their heir was vetted. Going abroad was out of the question unless they applied—humiliatingly—for permission from the Viceroy. And yet, they positively delighted in their vassalage. The British had been quick to cotton on to the fact that many of these rulers were essentially overgrown children at heart. Foolish sops—such as elaborate coats of arms—were given to each royal house.

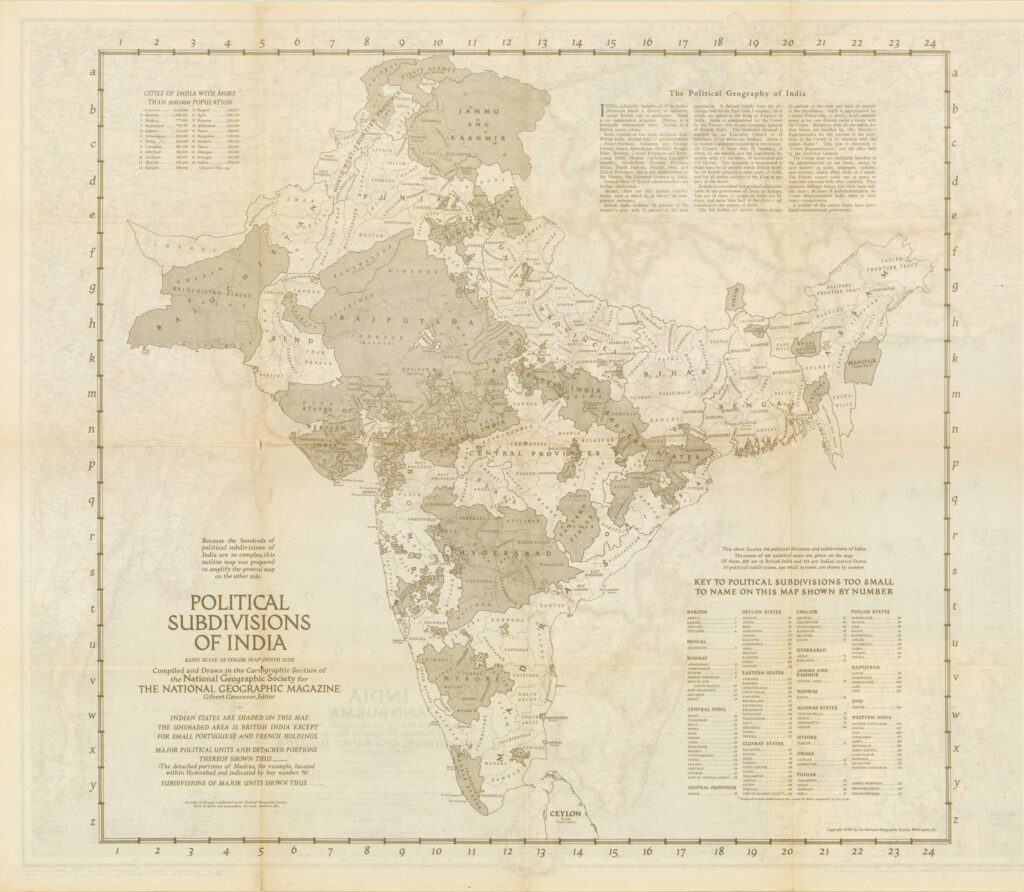

Political Subdivisions of India, 1946

Honorifics for good behaviour were doled out. Some were given the title of “Highness”, others were not. The Nizam of Hyderabad was rewarded for his financial generosity in coming to Britain’s aid with the highest honour of all. He was elevated from a mere “Highness” to “His Exalted Highness” and alone among the princes, his heir was given the independent title of Prince of Berar. Gun salutes were awarded according to the rank of princes—a stipulation that made grown men squabble like cats and dogs over who was of higher status. The rulers willingly accepted servitude in return. By the 1920s and 1930s, they had little other than their own pleasures to occupy them. And they took their pleasures very seriously indeed. A few—Baroda, Udaipur, Bikaner, Patiala and Bhopal—had some kind of vision for their States. Most had no vision at all. “He is a poor sort of moon-calf but quite biddable,” was an approving description of the Maharaja of Manipur. Obeying the Raj’s bidding was more than enough qualification, whether the prince was a fool, a knave or worse. “Some of them run their States very well and maintain a good level of administration but generally speaking, few men can overcome the handicaps to character of almost unlimited wealth, leisure and power,” commented Lord Wavell.

By the late 1940s, there was not a prince who did not own a Savile Row suit (or fifty) or a Rolls-Royce (or forty). Hedonists and morally corrupt though many were, they believed equally in leading their people on spiritual pilgrimages and in the signs foretold by the stars. Some of them, like Maharaja Vibhuti Narayan Singh of Benares, were deeply religious. When he visited the Nawab of Rampur, he insisted that the first object that met his gaze in the morning should be a cow. This put the Nawab—whose guest apartments were all on the first floor—in a quandary. The matter was resolved by borrowing a crane from a nearby sugar factory. Every morning, an astonished cow was hoisted up to the windows of the Maharaja’s suite, there to dangle until His Highness chose to wake up and settle his royal gaze upon the hapless cow. By the end of the Raj’s time in India, the princes had become a strange hybrid, superficially Western but essentially Eastern, both devoted to the Crown [the Maharajah of Dholpur took his devotion to an extreme, earning King George VI’s displeasure when he sent a message of congratulations to the former King, Edward VIII, on his marriage to Mrs Simpson. In his naivete, the Maharajah had forgotten Edward VIII had been forced to abdicate for having married a twice-divorced woman of ill-repute]. Whatever their shortcomings, the princes technically ruled over powerful swathes of land. At its peak, it spread over an acreage of half-a-million square miles. It was home to nearly a quarter of India’s 300 million population. Little wonder that V.P. Menon and Sardar Patel desired as many States as possible to join the Indian Union in 1947. However, the States Ministry did not have the faith and trust that the Raj assumed as a matter of right. It would have to be earned.

Whatever their shortcomings, the princes technically ruled over powerful swathes of land. At its peak, it spread over an acreage of half-a-million square miles. It was home to nearly a quarter of India’s 300 million population. Little wonder that V.P. Menon and Sardar Patel desired as many States as possible to join the Indian Union in 1947. However, the States Ministry did not have the faith and trust that the Raj assumed as a matter of right. It would have to be earned.

The story of the earning of that trust [and its subsequent betrayal by Nehru’s daughter, Indira Gandhi] is a convoluted one. There are several long-standing charges that V.P. Menon and Sardar Patel broke their promises to the Indian princes as embodied in the Instrument of Accession, which was drawn up and circulated that summer. They are accused of blackmail, coercion or its implied use, in compelling the more reluctant princes to accede to India. They are said to have known, long before they sat down to talk terms with Indian rulers, that this was all a charade. These are charges that have been levied by disgruntled princely loyalists: Corfield, Sir Arthur Lothian and Sir Edward Wakefield, as well as by disillusioned rulers and their consorts. Vijaya Raje Scindia, the Rajmata of Gwalior, gave VP the starring role in—what she called—“finishing off” the princely states. It is perfectly true that VP and Patel were not above—when neither their powers of persuasion or offers of empty honours worked—engaging in a judicious mix of arm-twisting and veiled threats. But they did not set out to betray the princes. Nor is there the slightest evidence to prove these charges.

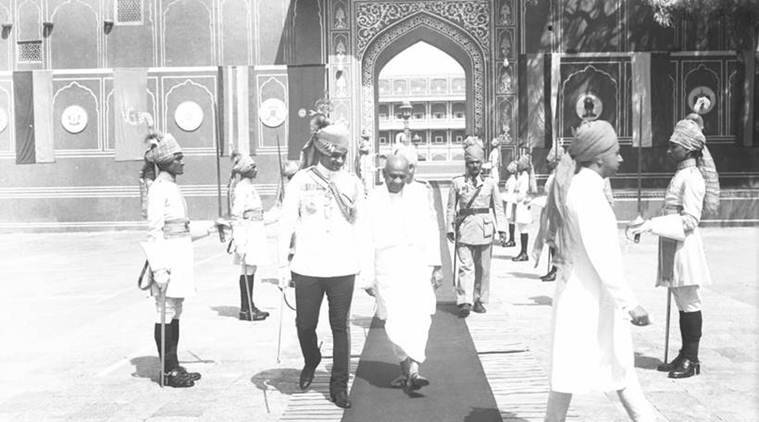

Sardar and Menon with Maharaja of Kochin

The Instrument of Accession was drawn up as a stopgap (and it might be remembered that VP’s official chapter on this in The Story of the Integration of the Indian States is titled “Stopping the Gap”) measure to ensure that some kind of orderly transition took place. Given the bloodcurdling events that were to follow independence and Partition, it is hardly likely that either Patel or VP hatched a long-term plot to hoodwink the princes. The fact was that the princes had been deeply suspicious since the Cabinet Mission’s botched attempts to safeguard their future. Since 1946, controversy had been raging over the meaning of sovereignty—apparently, the Diwans and their rulers understood it differently from India’s political leadership. In December 1946, N. Gopalaswamy Ayyangar and Jawaharlal Nehru both declared publicly that sovereignty within the States rested with the people, not with the rulers. This was, of course, a wholly tactless assertion. These were rulers who had, for centuries, claimed to trace their descent back to the Gods, and yet others to the sun and the moon. Over time, the rulers had come to almost believe this preposterous claim. Very few of them were ready to admit that their power came from a more earthly source: their subjects. Sir C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar, the brilliant, calculating Dewan of Travancore, for one, was incensed. “It is historically untrue to say that in Travancore, the sovereignty resides anywhere else than in the Ruler,” he declared sanctimoniously. “It was conquered and consolidated by a long line of rulers and the State was dedicated to the tutelary deity of the Monarch, as whose representative the Maharaja reigns.” From there, it was but a skip to refusing to join the Indian Union. “It is my painful but inescapable duty to declare that if the Constituent Assembly deliberately takes the line suggested in Sir N. Gopalaswamy Ayyangar’s speech as reported, my States, including Travancore … may find themselves unable to do so (cooperate with the Constituent Assembly). Deadlock was reached with an editorial in Hindustan Times, which warned ominously that the States would do well to be a little sensible. “If, through short-sightedness, any ruler should refuse to accept and prefer to stand outside the constitution, he will be reducing himself to the state of a feudatory to the Indian Republic … The States cannot be independent in any real sense. It is for them to choose whether they will be equal and honoured partners of the Indian Republic, or its subordinates.” Before VP was brought into the States Ministry, it was Ayyangar who led many of the initial discussions with princes across India.

Gopalaswamy Ayyangar

The figure of Sir N. Gopalaswami Ayyangar has been allowed to lapse somewhat into shadow. Born on 31 March, 1882, in the Tanjore district of the Madras Presidency, Ayyangar was appointed Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir in 1937, a post which he would occupy until 1943. Ayyangar would go on to be elected to the Constituent Assembly of India, and then to the thirteen-member Drafting Committee that formulated the Indian Constitution. His was the hand that drafted Article 370, which continues to haunt India to this day. He would lead the delegation that represented India in the United Nations over the Kashmir dispute in 1948 and again in 1952. His private papers reveal a fine legal mind, a gently persuasive charm and disarming forthrightness in his dealings with Kashmir, India’s status in the Commonwealth and with crotchety Diwans across the country. VP and Sardar may have been at the forefront of shaping a cohesive Indian Union, but Gopalaswami Ayyangar was a vital man behind the scenes, in the early days of talks with the Indian States. These were the months before Attlee’s dramatic declaration of 20th February, and in the last days of Wavell’s Viceroyalty. From December 1946 to March 1947, it is Ayyangar’s voice that is important. To give his role context, it must be remembered that V.P. Menon—having reinvented himself at this stage as Sardar Patel’s unofficial personal aide—was destined to be somewhat eclipsed for a short period of time. He would only come back into the spotlight later that summer. Ayyangar was not yet close to VP, though that equation would reverse itself radically once VP involved himself more closely with the integration of the States. It would be on his legal expertise that VP would quite often later rely.

VP and Sardar may have been at the forefront of shaping a cohesive Indian Union, but Gopalaswami Ayyangar was a vital man behind the scenes, in the early days of talks with the Indian States. These were the months before Attlee’s dramatic declaration of 20th February, and in the last days of Wavell’s Viceroyalty. From December 1946 to March 1947, it is Ayyangar’s voice that is important.

Ayyangar was present at a dinner at Bikaner House on 30 January 1947, attended by Nehru and by representatives of nearly every major princely house from Baroda to Udaipur to Gwalior. The discussions, which lasted well into the night, were frank and open. Every prince present referred, either obliquely or directly, to their suspicions about their future and the intentions of the Indian Union. Nehru was pleasant, recorded Ayyangar, and very cordial. He assured the princes that it was all in their minds, and that nothing dangerous was likely to happen, and that the Centre had no intentions of intervening in internal affairs.

The talks were amicable, and attempts to build bridges with the other States continued throughout February and March. Attended by rulers and representatives of states ranging from Bhopal to Travancore, from Dungarpur to Nawanagar and from Bilaspur to Bikaner and Kashmir, meetings were held with Patel, Nehru, Azad and Ayyangar in attendance. They were crammed with legalese, and often rambled beyond the agendas that were set for each particular day. The princes were deeply worried about boundary issues, about territorial encroachment in the event of grouping, in the allocation of seats for the Constituent Assembly and over questions of sovereignty.

The proceedings were volatile, though markedly polite. Nehru tried his best to diffuse the situation on multiple occasions. It did not always work: a discussion on allocation of seats between Sir C.P. and himself ended in an exchange of words that stopped short of an argument, with Nehru insisting he was free to say that he thought the States were obsolete in modern India. Incensed, Sir C.P. retorted that by that yardstick, he was free to say that he thought some political parties in India were “totalitarian.” Sardar Patel, who had no patience for Nehru’s verbal gymnastics, rarely spoke. When he did, it was to issue a thinly veiled warning. India would have no intentions of forcing anyone to join her, he said, adding enigmatically, “Events may force them.” At another meeting, this time on 9 February, Patel told the outraged Nawab of Bhopal, “To the extent to which you hand over your burdens, there will be no desire to take over your burdens.” The upshot of this was that by early March, when the last meetings of the States Negotiating Committees were held, the princes were split sharply down the middle. Some of the bigger houses—led by Bikaner and Patiala—thought it was better to be safe than sorry and decided to go ahead and join the Constituent Assembly. Others were unconvinced. Bhopal was growing warier by the day of India’s intentions and when Nehru refused to agree that the Constituent Assembly would ratify the understanding of the States Negotiating Committees before any State decided to join, it was the last straw. Hamidullah Khan resigned his post that day, on 18 April 1947.

Sardar Patel with the Maharaja of Jaipur

Although a number of States acceded to the Constituent Assembly by the end of April, Sardar Patel was far from satisfied. He had not liked what he had seen or heard of the princes, but he decided, with his usual cool pragmatism, that he should start gently. In the first weeks of May 1947, while plans for the transfer of power were being thrashed out, a flurry of royal personages arrived at 1, Aurangzeb Road. There was lunch with the Maharaja of Jodhpur on 6 May; the Jam Sahib of Nawanagar arrived for lunch with his wife on 11 May, followed on 16 May by the Maharaja of Patiala. Patel’s wooing the Jam Sahib was, as Rajmohan Gandhi has pointed out, shrewd. He had suspected that not only was the Jam Sahib in league with Corfield and the Political Department in trying to stay independent, but he had been behind the disturbances in Rajkot in 1939, that came so close to endangering the Sardar’s own life. What is more, Nawanagar held a powerful position in Kathiawar, with many of the minor princes calling the Jam Sahib “uncle.” The Sardar—always perceptive—deployed a personal touch. He used the ruler’s brother, a Colonel in the Indian Army, to reach out to the Jam Sahib. By the end of the meal, the Jam Sahib promised solemnly to do his best to unite the princes with the rest of India, prompting Sir B.L. Mitter (then the Diwan of Baroda) to exclaim enviously, “You have converted the Jam Sahib!” It wasn’t quite so easy. Nawanagar would always be particularly tricky, as events of nearly two months later would show.

The upshot of all this personal diplomacy was that by the time the Sardar brought in VP, a solid foundation had already been laid. The last Viceroy’s recollections of how the process of integration began are typically conceited. “The interesting thing is that when I talked to Nehru about this (about integration), he said that it was a tremendous problem, but he would like me to talk to Patel who was specialising in this.” Mountbatten recalled, “This was before he (Patel) came to be the designate to head the States Ministry. Patel’s position was very clear. He raised his hands and said, ‘You haven’t got to worry about the princes, or the princely states … They will all be toppled. None of them will be left on their gaddis. They will be out. The people will take over the government. There will be no worry.’ I said, That’s what you think. Let me tell you something. I know the princes very well, because I was on the Prince of Wales’ staff in 1921-1922, and ten of them became personal friends … The Indian states have extremely efficient forces. Hyderabad has a division, Jaipur has a brigade, Kapurthala has a battalion, Faridkot has a company. Whatever the unit is, these have been trained now by the British to take part in the war. They’re equipped with the latest weapons … If you try and topple these Maharajas, they would call out their state forces … they will mow down all the unarmed Congress people with their machine-guns and if you try and call the army out to fight them, you will find that the thing won’t work and there will be a civil war … if that’s your solution of the states, then I’m not interested in staying out here. He then said, ‘What do you suggest?’ I said, ‘I will suggest one thing. It is this. You and I are going to sit down and work out a solution. I don’t know what it is yet, but I now know you realise you can’t use force.’ He said, ‘If that’s your solution, that is not all.’” This entire farrago is neither true nor accurate. Not only had Mountbatten, by his own admission, even thought of the States at this point, but this conversation was not likely to have taken place in May.

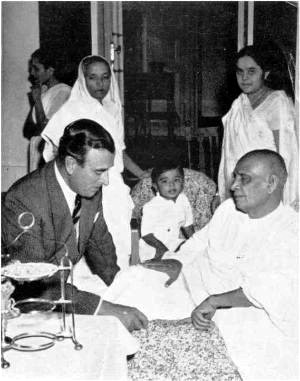

Mountbatten and Sardar Patel

Sardar Patel was well acquainted with the States, but in May 1947, he was not the Minister for States. His ongoing charm offensive meant that he was not, despite his enigmatic remarks during the meetings of the States Negotiation Committees, going to be so reckless as to speak of “toppling” any rulers. It would conflict with Nehru’s public stand that India would not intervene in any State, big or small. Mountbatten’s recollection of the moment has him then summoning VP, and insisting that the States acceded to India on the subjects of defence, external affairs and communication. “I talked to VP Menon, who was Reforms Commissioner, and gradually built up this idea of accession on three subjects: External Affairs, Communications and Defence. Now even there, many of the princes have told me that if it had not been for my relationship with the King, and my personal knowledge of the princes, they would not have trusted anybody else to negotiate this.” This statement is also untrue.

VP’s official narrative, published when Mountbatten was very much alive, [a narrative which Mountbatten was to laud], states quite clearly that he went back to his original plan for accession which he had handed to Linlithgow six years ago. Mountbatten’s calm assumption of ownership over the smooth integration of the princely states becomes understandable only when one conflates his enormous ego with Sardar Patel and V.P. Menon’s joint tactic of pandering to it. Both Patel and VP knew that any plan they had could only work if the Viceroy was not just on board, but was its ambassador. Patel, for example, knew the Nawab of Bhopal and knew that his friendship with Mountbatten would be invaluable in coaxing him from his high horse. This was a shrewd move. Records prove that Hamidullah Khan did, predictably, seek an assurance from the Viceroy that Patel and Menon would not renege on the Instrument they were offering. Mountbatten replied tartly that he would be in an “extremely strong position to expose them if they did not,” considering that he was going to remain in India until April 1948. But this was still in the future. For now, Patel and VP had to convince Mountbatten—no arduous task—that their plan was actually his plan. At different points that summer, then, the Viceroy was told deferentially that the only way history could move forward was if he played his part. It worked a little too well.

By the time the States Ministry was established, in June 1947, Travancore and Hyderabad had declared their intentions to stand aloof from both India and Pakistan. However, in an ominous warning, Sir C.P. had announced that Travancore would be appointing a “trade agent” to Pakistan. Several other States were having a hard time accepting a new intermediary between themselves and the Government. Gopalaswamy Ayyangar’s note on the prospects facing those States, which chose to remain independent, struck another chill into royal hearts. “From 15 August, there would be two Dominion Governments in the country. Barring a few States like Bahawalpur, Khairpur, Kalat and the tiny principalities in the Tribal Areas, the overwhelming majority of Indian States will be in India proper and not Pakistan.” Ayyangar wrote, “… Therefore, if things are not anticipated and suitable arrangements made in advance, the Indian States and their Governments will be left to fend for themselves … Some of them have claimed the right to be so independent as to have the freedom to enter into political, economic and other relations with foreign countries outside India, without any reference to the Government of India. It is not in their interests to do so.” The note loses no time in becoming more explicit, “Nor could the dominant power in India, namely the future Government of India, afford to look on while Indian States, most of which will be islands within the Union, attempt to establish political and other relations with foreign countries …” For all these reasons, Ayyangar concluded smoothly, a States Department was vital for the future of India. The only problem was—every ruler in the country knew that with Sardar Patel in charge, it was not going to be a neutral prospect. No one could say so outright, of course, but Ayyangar was the recipient of several agitated letters that summer. V.T. Krishnamachari, the clever Prime Minister of Jaipur, wrote to explain—at length—how disastrous a States Department would be. “I do not think it (the States Department) is good either in the interests of India as a whole or of the States,” K.M. Panikkar, Diwan of Bikaner, wrote too, to advocate for some kind of transitory administrative machinery to be put in place in the States while the transfer of power was being effected.

Gopalaswamy Ayyangar’s note on the prospects facing those States, which chose to remain independent, struck another chill into royal hearts. “From 15 August, there would be two Dominion Governments in the country. Barring a few States like Bahawalpur, Khairpur, Kalat and the tiny principalities in the Tribal Areas, the overwhelming majority of Indian States will be in India proper and not Pakistan.”

Of all these flutterings, Ayyangar took suave and kindly notice, promising that royal concerns would be looked into. In reality, of course, his ideas were very different. India’s geography, history, economics and political prospects required that Indian States needed to be compelled to stay within the Indian Union. There could be no question, as in the case of Travancore and Hyderabad, of their staying independent and demanding equality with the Government of India. Not only would it mean the effective “balkanisation” of India, but it would be contrary to every aim of the independence movement so far. It would, Ayyangar was convinced, lead to chaos and anarchy—which a newly independent country could do very well without. “India cannot permit this, and should either re-subjugate these bits of State territory in her midst or force them to make the choice between the Cabinet Mission’s two alternatives.” Significant, then, that the men who led the formation of the States Department all had the same views on the subject.

V P Menon

V.P. Menon assumed his post as Secretary of the States Ministry on 5 July 1947. He would also continue holding his post as Constitutional Advisor to the Viceroy. In effect then, the summer of 1947 saw him in charge of not only India’s transfer of power, but her integration as well. By this time, he had been fully briefed about the paranoia of the princes, and having read through Ayyangar’s notes and seen copies of his correspondence with Diwans across the country, he knew that the first thing to do was to calm royal fears. He prepared a statement for the Sardar to read out on 5 July to the press. It was a satisfactorily conciliatory one, which, as VP mentioned later with simple pride, took inspiration from Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural address.

V.P. Menon assumed his post as Secretary of the States Ministry on 5 July 1947. He would also continue holding his post as Constitutional Advisor to the Viceroy. In effect then, the summer of 1947 saw him in charge of not only India’s transfer of power, but her integration as well. By this time, he had been fully briefed about the paranoia of the princes, and having read through Ayyangar’s notes and seen copies of his correspondence with Diwans across the country, he knew that the first thing to do was to calm royal fears. He prepared a statement for the Sardar to read out on 5 July to the press. It was a satisfactorily conciliatory one, which, as VP mentioned later with simple pride, took inspiration from Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural address.

“We ask no more of the States,” declared Patel, “than their accession on these three subjects in which the common interests of the country are involved. In other matters, we would scrupulously respect their autonomous existence.” Patel’s statement soothed those of the princes who had agreed to join the Constituent Assembly in preparation for independence. The Maharaja of Bikaner spoke to the press on 8 July, “If I may say so, a more appropriately worded statement, breathing genuine friendliness and goodwill towards the States could hardly have been made at this momentous juncture …” The Maharaja of Alwar sent a personal cable to Sardar Patel, “Your recent statement regarding the States is most welcome at this juncture … There can be no manner of doubt that the hand of friendship and cooperation extended by you will be grasped firmly by the States.”

The stage was set.”

The only problem was—there were no officials.

The Political Department had been shutting down all through April and May. By July, most senior officials had gone home on leave or had applied for their pensions. Only Sir Conrad Corfield clung on to office. Hurriedly, VP arranged for the transfer of C.C. Desai, from the Ministry of Supply. Desai had a long history in administration across the country and was available on short notice. He turned out to be a most able deputy, and together with two junior aides, formed VP’s own core team. These were the men who would put their heads together over the reordering of India’s political map. It wasn’t long before the States Ministry would become a juggernaut by itself. Under the leadership of Patel, with VP as his deputy, the Ministry began to weed out the men it believed were detrimental to the integration of India. The first to go was Corfield—who had probably known that his days in the service were numbered, after VP—long his bête noire—took over. The denouement came in consequence of the heated discussions between VP, Corfield and others over clauses regarding the States in the Indian Independence Bill. The issue at stake centred around, as did everything else when it came to the States, the lapse of paramountcy. VP had his eye on the undoubtedly strategically important agreements with Bahawalpur and Bikaner (struck in 1920) over the Sutlej Valley canals, and on British India’s agreement on salt with Jaipur and Jodhpur. It would be, quite obviously, to India’s immense advantage if she could inherit these agreements from Britain. This infuriated Corfield who saw in it a trap for the States in question, not without good reason. In this argument, VP lost—Pethick-Lawrence stepped in at the last moment and said that he really had no choice except to support the Political Department’s stand. But the enmity simmered.

Matters would not take long to come to a head. Knowing full well that Corfield was working unrelentingly to ensure that the princes stayed out of the independent Union of India, VP decided to begin meeting the princes himself. His first meeting was with the six-foot-four, impressively bearded, intelligent Maharaja of Patiala. Yadavindra Singh was nothing like his scandalous, hedonistic father. He was an intelligent man and VP decided to not insult his intelligence by feeding him with flattery and hollow promises. “I told him frankly that independent of us, you cannot exist.” VP’s decision to be blunt worked. The Maharajah may well have left the meeting with the uncomfortable knowledge that Patiala had been given no choice but to accede to India. What are we to make of VP’s statement that the Maharaja and he “parted as friends”? The fact is that, in late 1951, when VP had retired from government service, the Maharajah not only officiated at Angu’s civil wedding in Simla, as a witness, but housed the Menon family in Simla for the duration of their stay. Soon, nearly every major ruler, all of whom met the new Secretary to the Ministry of States, realised that here was a man who enjoyed the full backing of the government.

Knowing full well that Corfield was working unrelentingly to ensure that the princes stayed out of the independent Union of India, VP decided to begin meeting the princes himself. His first meeting was with the six-foot-four, impressively bearded, intelligent Maharaja of Patiala. Yadavindra Singh was nothing like his scandalous, hedonistic father. He was an intelligent man and VP decided to not insult his intelligence by feeding him with flattery and hollow promises. “I told him frankly that independent of us, you cannot exist.” VP’s decision to be blunt worked. The Maharajah may well have left the meeting with the uncomfortable knowledge that Patiala had been given no choice but to accede to India.

In July, the Maharaja of Jodhpur’s ADC, called upon VP. The ADC remains unnamed in VP’s personal recollection, but it was well-known that Jodhpur was wavering between joining India or Pakistan and that Jinnah was circling him like a vulture. “That ADC told me that Jodhpur had been to see Corfield many times. Sir Conrad had come often to see him too—long meetings, which sometimes went on into the night. I was so angry.” VP was even more livid when he discovered plans—laid carefully by Corfield—to encourage the Nawab of Bhopal to believe in the viability of deploying a “Third Force”, Bhopal’s own independent militia against the Union of India. It was the last straw. VP went straight to Lord Mountbatten and told him in no uncertain terms that keeping Corfield on in India was a catastrophic mistake. “I told him that either Corfield should go, or I would. The two of us could not be in Delhi any longer at the same time. I told Mountbatten that I did not need or want his advice and if he thought we could get along together, he was making a big mistake.” VP’s threat was all it took to persuade Mountbatten, no great admirer of Corfield himself. By the middle of July, Conrad Corfield departed the country he had always loved. It was a lonely, unsung exit, lent a touch of drama only by his orders to have great sheaves of official documents of the Government of India—all pertaining to the princes and their more scandalous activities and four tons in all—destroyed before he left. It was the final act of a vandal, who served the interests of the princes more than the interests of the government that employed him.

The Maharaja of Bikaner, the Maharaja of Gwalior, the Nawab of Bhopal & the Maharaja of Patiala in the Chamber of Princes comprised of native rulers who traditionally do Britain’s bidding

On 10 July, a bevy of senior princes—Patiala, Baroda, Bikaner and Gwalior—descended upon 1, Aurangzeb Road. It was not a formal conference, but one intended to break the ice and allow some of the major—and willing—princes to get to know the new Minister and his Secretary. The Sardar explained their terms of accession, and also explained the role of the States Ministry in the process. The rulers present agreed to the agenda set for the upcoming conference at the Chamber of Princes, scheduled to be held on 25 July. Pleased by the smoothness with which the meeting had gone, VP dashed off a formal agenda for accession (the draft of what would become the Instrument of Accession), which he handed to a junior official in the States Ministry, asking that it be delivered to Abdur Rab Nishtar. There was a predictable explosion from Jinnah. Jinnah, deeply suspicious of Indian intentions, began dangling promises to the princes of their guaranteed independence in Pakistan. But by this point, most of these distractions were just that—distractions. Sir C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar, the Diwan of Travancore sent Mountbatten a letter on 15 July, saying in effect, that since Travancore had chosen to be independent, there was no point in sending a representative for the meeting of the Chamber of Princes on 25 July. More dangerously, Travancore was threatening a campaign of direct action, to begin on 1 August 1947. Hastily Mountbatten summoned Sir C.P. to Delhi, where he was promptly closeted with VP. This time VP chose to deploy a different set of tactics to the ones he used with the Maharajah of Patiala. He spoke of the strategic advantages to Travancore after accession, appealing first to the Diwan’s intelligence. Sir C.P. was ready for him. Travancore was a maritime State, he pointed out. If, as the Instrument stated it must, it would hand over half its revenues from customs, and import-export duties, then it would be a “fifth-rate” State. Not at all, VP replied reassuringly. The Instrument put no weight on financial commitments. All Sir C.P. had to do was to accede on defence, external affairs and communications. Perhaps he might like to rethink matters? After all, independence would leave Travancore—a great and prosperous state—wholly open to all kinds of anarchy. Seeing Sir C.P.—whose pride in his State was unparalleled—soften a little, VP switched deftly to a more personal tack. “I assured him of my high regard for both his realistic attitude to affairs and for the part he had played in the past. It ought not to be said of him that at India’s critical hour, he had not made his contribution towards building a united India when he had it in his power to do so. It was a tack that had worked brilliantly on Mountbatten—and it would work its charm on Sir CP now. For the first time in months, the Diwan thawed a little, unbending enough in front of the Viceroy to say that he could “agree” on the three subjects, rather than “accede.” This wouldn’t do. VP was brought in again, and this time he changed his tactics again. There would be no talk of any “agreement”. Travancore had to sign on the dotted line. Nothing else would do. On 23 July 1947, the Diwan of Travancore returned to Thiruvananthapuram. In his bag, he carried the draft Instrument of Accession. On 24 July, another conference was held, this time with Patiala, Gwalior, Bikaner, Mysore, Nawanagar and Jodhpur. It was a hopeful sign. “It showed that we were making headway with our plan.” More importantly, it showed that Hamidullah Khan’s feverish, incessant machinations to keep his peers free from the clutches of a new Union of India were failing. However, it was the ceremonial pomp of the Chamber of Princes that would seal the deal, as far as the princes were concerned.

This was one of the last meetings of the Chamber, and there was not a prince present who did not feel a twinge of regret as they drove down the highways into the lush greenery of Lutyen’s Delhi. Some came, borne on flying-boats from their summer retreats in Cannes and the Riviera. Narendra of Sarila drove through the day for ten hours, arriving from Charkhari as dusk was dropping over Delhi, in his brother’s convertible Sunbeam Talbot. It was a sight to behold— and certainly one that would never be seen again. It was hardly a Chamber—a cramped room, built like a semi-circular amphitheatre, to house not more than 150 princes. Into this room filed the Maharajas who had chosen to attend. Kashmir, Hyderabad, Mysore and Travancore were notably absent. There were others who had chosen to deliberately stay away, persuaded by the Nawab of Bhopal. The 25-odd rulers who were present were all tanned and prosperous from their holidays on the Continent. They had come to listen to the Viceroy speak. Mountbatten strode in, and leaped nimbly up onto the dais. He was in full military uniform, the white of the cloth and the glittering medals standing out in sharp relief against the red carpeting. For a minute, he was caught in a blaze of flashbulbs. The press was present to document this occasion. Standing beside him was the Maharaja of Patiala. Mountbatten spoke fluently and well. He explained to the princes that India was moving towards a new chapter in her history. After 15 August 1947, he would no longer be in a position to help them as he could help them now. “He succeeded in creating the impression that he was a friend who was trying to help the princes,” recalled Narendra of Sarila. It was not a difficult impression to create. Mountbatten was on excellent terms with most rulers. He was a personal friend of Bikaner and Dholpur, he shot tigers in Gwalior and enjoyed fishing in Mysore. Most princes referred to him, quite simply and with great affection, as “Dickie.” Small wonder then, that they merely sat there, looking at him, “like plump, velvet, cattle, their large, sad, calm, brown eyes fixed trustingly on their herdsman—who was about to tell them the best way to the abattoir.

The meeting was thrown open subsequently for questions and answers. The range of questions that were asked showed that despite Sardar Patel and V.P. Menon’s best intervention, the rulers were either wilfully misunderstanding the terms of accession or were downright stupid. There were demands about exclusive rights to big-game hunting, about the number of gun salutes on ceremonial occasions, on the titles and honorifics they were allowed to keep. There were some princes who stayed silent through everything and merely left at the end of the session. There were yet others, like the Maharawal of Dungarpur who muttered something under his breath about an “Instrument of Execution.”

The meeting was thrown open subsequently for questions and answers. The range of questions that were asked showed that despite Sardar Patel and V.P. Menon’s best intervention, the rulers were either wilfully misunderstanding the terms of accession or were downright stupid. There were demands about exclusive rights to big-game hunting, about the number of gun salutes on ceremonial occasions, on the titles and honorifics they were allowed to keep. There were some princes who stayed silent through everything and merely left at the end of the session. There were yet others, like the Maharawal of Dungarpur who muttered something under his breath about an “Instrument of Execution.” The Diwan of Bhavnagar was caught off-guard by the realisation that he needed to give Mountbatten an answer pretty rapidly. He got up to say that since his ruler had left no instructions behind before leaving to go abroad he could not say whether or not his master would sign. “I do not know my Ruler’s mind,” he pleaded. Quick as a flash, the Viceroy picked up a heavy glass paperweight from the dais and pretended to consult it, “Let me look into my crystal ball,” he announced. There was a dramatic hush for several seconds while Mountbatten gazed deeply into the paperweight. Then he laid it down and smiled, “His Highness asks you to sign the Instrument of Accession.” The Chamber echoed with laughter for several minutes. It is a sad little anecdote in retrospect and shines an uncomfortable light on just what the Viceroy really thought of his devoted audience.

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of Narayani Basu and Simon & Schuster. You can buy V.P. Menon: The Unsung Architect of Modern India here.

Narayani Basu is the bestselling author of V.P. Menon: The Unsung Architect of Modern India (Simon & Schuster India, 2020). A historian and foreign policy analyst, her current area of interest focuses on highlighting less-known key players behind the story of Indian independence. Her most recent book, Allegiance: Azaadi and the End of Empire (Fifty Two, 2022) is now available on Kindle.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

A comprehensive biography of V P Menon was long overdue and Narayani Basu should be congratulated for her book. Readers may be interested in the following shorter biography of Menon entitled V P Menon – The Forgotten Architect of Modern India which was published over 10 years ago and contains more of Menon’s own opinions of the important players and decisions taken:

http://www.forgotten-raj.org/doc/menon.htm