This article by the writer Mulk Raj Anand, titled Gaganendranath Tagore’s Realm of the Absurd, was published in JISOA (the Journal of the Indian Society of Oriental Art) in 1972. By one account, it was first published before this, in 1951.

Gaganendranath, brother of the artist Abanindranath Tagore, and nephew of Rabindranath Tagore, was one of the first modern Indian painters, who wore different creative hats at different stages of his life. Training under the watercolourist Harinarayan Bandopadhyay, he went on to learn Japanese brushwork from Kakuzo Okakura and other visiting Japanese artists. He played a key role in founding the Indian Society of Oriental Art, along with his brother Abanindranath, and pioneered experiments in modern painting. According to Partha Mitter he was “the only Indian painter before the 1940s who made use of the language and syntax of Cubism in his painting”. He also took a keen interest in theatre (especially acting and set-designing; along with brothers Abanindranath and Samarendranath, he was the founder of a creative initiative called the Bichitra Club) and wrote a children’s book titled Bhodor Bahadur (Otter, the Great) after the manner of Lewis Carroll’s fiction.

However, “From ink sketches to watercolour landscapes, cartoons to cubist compositions, Gaganendranath Tagore’s art suggests a refusal of affiliation, a denial of closure too,” writes Sanjukta Sunderason in her article Arts of Contradiction: Gaganendranath Tagore and the Caricatural Aesthetic of Colonial India. It is this “refusal of affiliation” and this “denial of closure” that permeates his satirical caricatures that we have presented for you here today (along with some of his other art).

These cartoons, drawn from three books – Adbhut Loke: Realm of the Absurd, Virup Vajra and Reform Screams – published from 1915 to 1921, as well as The Modern Review, emerged in an Indian society on the cusp, where the battle between modernity and tradition was being waged as fervently as ever, in society, religion and politics, among landlords and peasants, and industrialists and workers, by men and women, and in the courts of public opinion, as well as people’s minds and daily lives.

And who better to read in between the vital lines that make up these caricatures than Anand, a founder of Indian-English fiction, founder-editor of the art magazine Marg, a voice for the downtrodden, and a relentless surveyor of the contours – good and bad – that continually challenge an Indian mindscape negotiating the idea of modernity. Challenges that lead, in Anand’s words: “in most ordinary cases, to the compartmentalisation of ordinary existence and, in some intense cases, to schizophrenia or split mind.”

Gaganendranath identifies this compartmentalisation and schizophrenia and hits out at the hypocrisy – which he views as “deformities” growing “unchecked” “but… cherished by blind habit” – in every direction. He tears into the anglicised aspirations of the Bhadra Log, ever in search of sahibdom, as well as ubiquitous cases of fraud and superstition that have sprung up among the Hindu priestly caste, and the terrifying oppressiveness of caste. His ire then turns to a Maharaja, a British Viceroy, Prime Minister and Secretaries of State, and Indian politicians and their hollow speeches. And scientists, industrialists and university vice-chancellors, as well as the parents of students. The list is endless. No one is spared. Gaganendranath’s pencil doesn’t hesitate to caricature his own uncle Rabindranath Tagore, for flying above the rest and not being clear on whether or not he supports the Non-Cooperation Movement. While some of the issues he raised may not be applicable today, and serve primarily as a lens through which to distill the past, many – sadly – still are.

And yet, it isn’t all ire. Anand writes about how, in his depictions of the Bhadra Log, “The catharsis of Gagan Babu’s art lay in the tremendous pity he felt for these victims of his felicitous and eager pencil and brush.”

Gaganendra passed away at the age of 70. Sunderason writes: “Bed-ridden after a paralytic attack in 1929 and immobilized until his premature death in 1938, Gaganendranath Tagore is himself an incomplete tryst with the modern. Situated right in the middle of his oeuvre, his cartoons reveal, thereby, a density that needs to be retrieved, not just to study the artist’s disposition, but for its potential resonances both for the genre of visual satire as well as the political unconscious of modernism in India.”

Today we live in an India where attacks on satirists, humorists and comedians – both by the state as well as non-state actors – have become unfortunate news. It would serve us well, at such times, to remember and appreciate both the unabashed boldness as well as the intuitive – and still relevant – genius of Gaganendranath Tagore’s satire.

Our country has been witnessing the emergence of a kind of “montage” man in the last two hundred years. Our montage has been pieced together after selection and cutting, like the shots in the making of a film. We have got too used to him by habit to have noticed his peculiarities. Especially as we are ourselves montage men. Nevertheless, the personality of this extraordinary human hovers between the sublime and the ridiculous, or is, rather, entirely ludicrous, because the sublimity he has achieved is in itself somewhat amusing.

The fact that the montage man has not been recognized is due partly to the fact that we are traditionally an assimilative people, who can reconcile in our persons the collection of most diverse qualities and attributes, and partly because we are romantics who, if only because we had not the choice to create a new order, prefer a patched quilt colourful disorder to classical perfection, and thus made a virtue of our disintegration. For, after all what can a naked fakir do if he can only afford an assortment of rags to clothe himself with. The trouble is, however, that even those who are not exactly beggars prefer to wear the most mixed habiliments as, for instance, the Madrassi High Court Judge who sports a navy-blue suit, a butterfly collar, a small ready-made child’s turban on the head, the Shiva mark on the forehead and the complete absence of footwear, compensated for by the adornment of a dignified umbrella.

This view of our montage character, based on the adhoc combination of Western and Eastern motives in our clothes may be somewhat superficial, but it is indicative of the assortment of impressions and ideas which make up our inner lives and it points to the contradiction of values which has led, in most ordinary cases, to the compartmentalisation of ordinary existence and, in some intense cases, to schizophrenia or split mind.

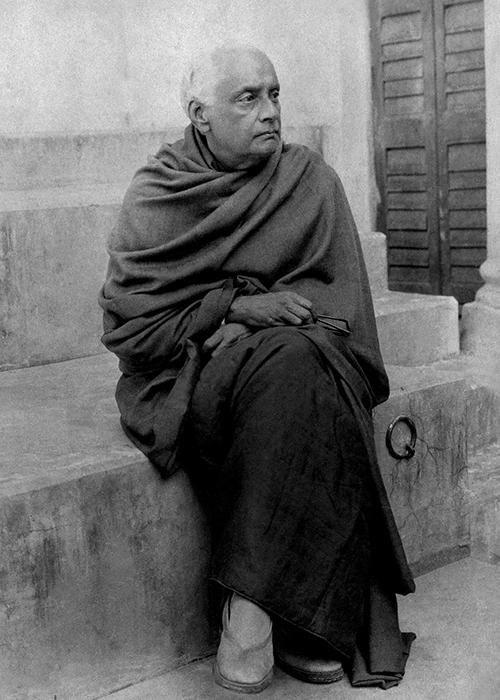

Gaganendranath Tagore

If there has been a corrective against such decomposition, it has risen from the various intellectual movements which deliberately sought to create the new order. The freedom struggle was the biggest of these forces, and it had as its ancillaries the social and cultural influences which arose in the wake of the renaissance in Bengal in the 19th century under the inspiration of men like Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Isvar Chander Vidyasagar, the Tagores and various others.

All the contraries in our natures could not, however, be affected by these broad movements, and it was left to isolated individuals to call attention to the disruption of values, from time to time, through the unconventional media of satirical literature and art. Even until today there is not enough of this kind of activity, which could debunk the flagrant neglect of that essential dignity which is inherent in man and which leads him to evolve the rules of good behaviour and achieve civic consciousness in the enjoyment of the corporate life. Still there have been notable protests, which must increase in quantity before the average Indian can cease to be like Edward Lear’s “old man of Thermopylae, who never could do anything properly.”

Poet’s First Flight from London to Paris Gaganendranath Tagore’s caricature of Rabindranath Tagore

One of the most important protests in this connection was made by Gaganendranath Tagore, the brother of Abanindranath Tagore and nephew of the poet Rabindranath. The work of Gagan Babu has been neglected because, although he was a member of the renascent movement in painting which his brother initiated by going back, like the pre-Raphaelites, to an older tradition, he stood out as an individual, apart from the current. During his whole lifetime he produced work which was mostly experimental, at a time when such innovations as have now become respected as the principals of modern art were derided. Also, Gaganendranath suffered from a long illness before he died, and his gentle and shy manner precluded him from seeking the kind of publicity which wins popularity in our country. Nevertheless, he is a legend among the discerning and, as time passes, his work is coming to be recognized as even more significant than the major works of the school with which he was vaguely associated. For both in his mature painting, where he sought to absorb world influences into the service of his own peculiar private vision of forms, and as commentator through his cartoons on current affairs, he displays a depth of understanding about the mental and moral crises in which India has been involved and an extraordinary technical visionary as a craftsman.

I want here to draw attention to his series of caricatures which appeared in some books published during the early years of our century Adbhut Loke (1915), Virup Vajra (1917) and Reform Screams (1921). These portfolios are very rare. They were published at modest prices and were quickly bought up and got lost in the limbo of Bengal’s memories of old times. I believe that not only are they very important as the social history of the epoch in which Gaganendranath lived, but they constitute some of the finest caricatures done in India since the death of the Rajput tradition of the 18th century and certainly models of what cartooning should be in the hands of the current practitioners of this art in our newspapers. As the matter of these caricatures is often similar in content, I shall deal with the three books as one. But in order to clarify the approach of Gagan Babu’s towards his material it may be interesting to see why his violent protest against society arose with such intensity in Bengal and not in any other part in India.

Pratima Visarjan a water colour painting by Gaganendranath Tagore

“When deformities grow unchecked”, wrote Gaganendranath Tagore by way of a preface to Virup Vajra, “but are cherished by blind habit, it becomes the duty of the artist to show that they are ugly and vulgar and therefore abnormal.”

This reveals the artist’s awareness of the deformities which he could see in society. And from the reminiscences published after Gagan Babu’s death by Dr. Brajendranath Seal, the historian of Bengali literature, it becomes clear that he also knew the causes of the deformities. Himself descended from a landlord family, and yet brought up in the era of early industrial enterprise in India, Gaganendranath was conscious of the impact of Britain on India. Though the Tagores were landowners they had also been taking initiative in industry and were typical of the kind of middle class household which had risen through the British invasion. They were, of course, attempting a cultural synthesis between Europe and Asia, far more ardently than any other Bengali family of the time; and, in this case, they were both the actors in the drama as well as spectators of it.

But what was the exact nature of this drama?

It is well known that when the British conquest of India was proceeding apace, the Directors of the East India Company sought to enlist the help of certain elements in the country through whom they hoped to implement their hold on the landscape. With a view to this, they obviously looked for support among people, who were in positions of authority over the mass of the population and in direct contact with the natives. The only class which stood in this peculiar position in India at that time, was composed of the rent collectors of the local chieftains, men who did not stay in the villages but only visited the countryside on behalf of whosoever happened to be the Sultan, Nawab, or Raja in the capital city.

The British decided to enlist the service of this class to collect rents from the peasantry, but in a manner rather different from the one in which they had been collecting revenue for their previous masters. Without analyzing the precise role of the Indian rent collector in his relations both with the Raja and the Ryot, the foreigners thought of these men as constituting the middle class on the English pattern, that is to say, the class standing between the King and the peasantry, as the Barons or the feudal lords had stood between King John, of Magna Carta fame, and the serfs on the feudal estates. Actually, however, the peasantry of the villages of India could not be compared to the serfs on the feudal estates of England, nor could the Barons be superimposed as a model for the rent collectors to emulate. The structure of the Indian village republic had, from times immemorial, been built on the foundation of certain rights in land enjoyed by the peasantry, with extra rights of grazing their cattle on the common pasturage and cutting wood from the communal forests. The rent collector, who was a nominee of the king, came to collect the revenue in kind and did not stay in the village as Lord of the Manor, but went away to the capital.

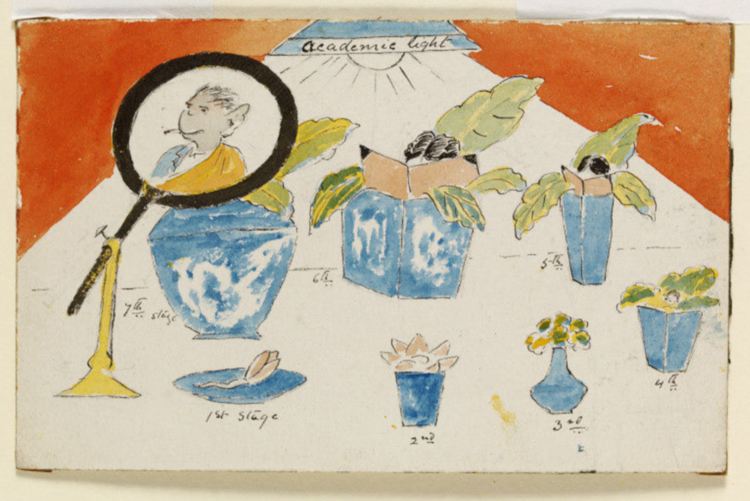

Botanical Sketch A postcard by Gaganendranath Tagore which depicts the evolution of a Westernised Indian academic, with a cigarette, wearing a jacket and tie underneath a saffron robe. The lamplight that the plants ‘grow’ under is labelled “academic light”. The idea for this cartoon, which appeared in the Modern Review, was possibly prompted by experiments conducted by scientist Jagdish Chandra Bose who showed that plant growth was accelerated by constant exposure to simulated sunlight.

The economy of the village continued to work on the basis of an exchange of services and goods. And it was a closed system, until the British came in and imposed the idea of ownership of land on the peasantry in the same way in which this idea had obtained in England from the Norman conquest. Through Lord William Bentinck’s Permanent Settlement Act of Bengal, property in land was vested in a certain number of landlords, whose duty it was to pay a certain feudatory tribute to the Company and to retain the bulk of the rent collected from the peasantry for themselves. Thus was created the first middle-class of India, the landed gentry, called Bhadra Log in Bengal. These gentlemen tended to become, in the hundred years after the Permanent Settlement was in operation, absentee landlords, who derived their earnings from their vast estates in the country, but lived between the enormous palaces in the village and the big houses in the capital of Calcutta. More often than not, they were honoured with the titles of Rajas, Nawabs, Rai Bahadurs, etc., and they were jocularly known as the “Brown Barons”.

They were devout servants of the Company’s Raj, and they began, in the course of time, to adopt certain English manners and customs over and above the traditional dasturs inevitable to their position as members of the Hindu caste order or the Muslim Brotherhoods. In the juxtaposition of the elements of the English and the Indian traditions in their persons and around them, there arose a hotchpotch atmosphere in which fantastic incongruities became visible at every turn. The essence of these incongruities lay in the abject wish of the Bhadra Log to imitate the new masters, while attempting to preserve their habitual forms and modes of life. But the result was as unaesthetic as it can be in the eyes of those who had any sense of taste and were concerned with the creation of harmony—such as the poets and the artists. The catharsis of Gagan Babu’s art lay in the tremendous pity he felt for these victims of his felicitous and eager pencil and brush.

It seems that by a peculiar individualism in his temperament, as well as his great natural gifts as an artist, Gaganendranath Tagore was well equipped to voice the protest against the current vulgarity.

Sir J. C. Bose has said that Gaganendranath’s cartoons “are not the soured delineations of a cynic but scenes which must have wronged the artist’s soul with sorrow.”

This view is borne out from the serious, even fanatical, revolt of Gaganendranath against the superficial impulses of Europe which were gripping Indian life and destroying even the better habits of the Indian people. To an extent this revolt was tinged by the rising nationalism of the time. For instance, Dr. Dinesh Chandra Sen records:

“Once he [Gaganendranath Tagore] and his brothers [Samarendranath and Abanindranath Tagore] removed all the pictures by famous French and Italian artists, which their forefathers had collected, from the walls of their large hall and gave them away. The sumptuous flower-vases and other objects, which for many years adorned the tables in the hall as they were made in Europe, received a similar treatment at the hands of the brothers. In divesting their palatial building of everything of foreign origin the brothers seemed to take such pleasure as is perhaps enjoyed by the iconoclastic. They had heard the call of their motherland and attempted to give a legitimate place to Indian art. Whatever ideas took shape in this family today captured West Bengal on the morrow and found staunch supporters in East Bengal the day after.”

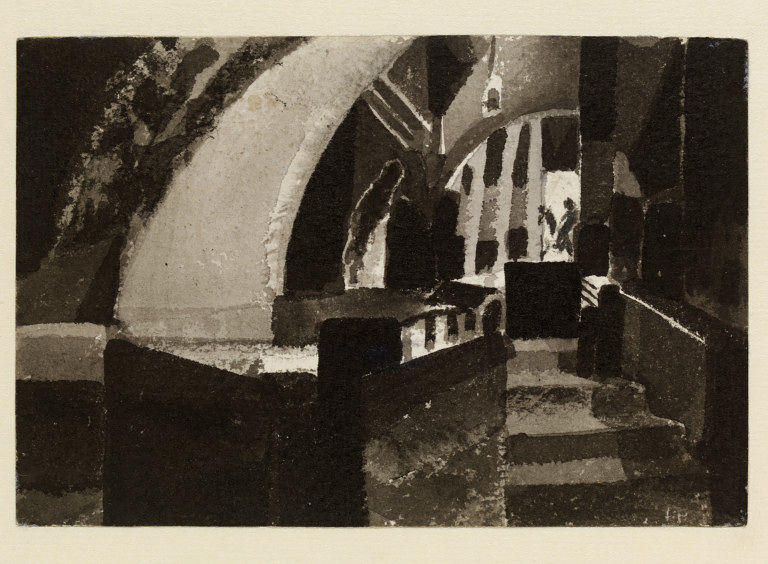

One of Gaganendranath Tagore’s first Cubist experiments, in colour and black ink, depicting the dreamy interior of a house with shadowy figures.

But the iconoclasm, especially that of Gagan Babu, was only a phase. He had a deeper grasp of things. Apart from the fact that he was closely associated with the Brahmo Samaj, which sought to synthesize the cultures of Europe and Asia, especially in religion, and to rid Hinduism of many of its evils, he was concerned to rediscover the emotional basis of Indian values and was not merely chauvinist in his outlook.

In middle life, Gaganendranath suffered a great shock through the death of his eldest son at the age of 16. In his attempt to regain peace of mind he had sought comfort in the narration of old Indian stories, with their insistence on the truths of philosophy, chanted by the Kathak (the professional story-teller) in a melodious voice. Few among the educated and elite of that time would have understood the nature of the miraculous cure in Gaganendranath’s personality which followed the unending flow of pathos in the legendary stories recited to him and his family by the Kshetra bard whom they had engaged for the purpose. And it is conceivable that when the artist told his friend Dinesh Chandra Sen that he derived great consolation and pleasure from Kshetra that he was indicating the occurrence of a process of integration in his fundamental outlook.

He began to feel that the balance between the outer shock administered by Europe, and the inner soul of India, could be struck only by a rediscovery of the Indian way of life, with the attempt to absorb as much of foreign influence as could be really assimilated. Just as he was concerned, unlike his other contemporaries in the world of painting, to struggle for absorption into his painting only those techniques which would fit into his own integral vision, so, in the world of values, he tried to evolve an order in which the basic truths of Indian heritage could be reconciled with foreign impulses. His method was introspection, but it found expression in little symbolic acts which confirm one in the belief that his sense of order and taste had almost become instinctive with him. There is a story told by Dr. Sen which is typical of Gaganendranath’s attitude:

“One wintry morning, Gagan Babu came to my house in Shyambazar and found me covered with a blanket (kantha). The design was run in an exquisitely delicate and decorative style. It was made in some village, and it was presented to me by a lady of my family. Gagan Babu was dressed in a new English overcoat which must have cost him about seventy or eighty rupees. He took it off and threw it on my back and started a regular tug-of-war with me to take away my blanket in exchange for his costly overcoat. I said: ‘I shall get another blanket made for you—this being a token of affection, I am very sorry I am unable to part with it.’ I could clearly realize his feeling of disappointment at my refusal”

Apart from this kind of reaction, one can clearly sense in the memoirs his friends have of Gaganendranath that he had inherited and enlarged certain inherent graces, nobility of character, hospitality and magnanimity, which were the best remnants of the feudal tradition. Rabindranath Tagore speaks of his “spontaneous graciousness” and “combination of sweetness and light” and of his “social wisdom—quiet dignity and distinction which may be called aristocratic, although it had not the slightest hint of proud aloofness, for he strangely attracted even those who belonged to alien races by his genuine spirit of welcome, free from the show of conventional effusiveness usual in our society.” The poet has further written:

“What profoundly attracted me was the uniqueness of his creation, a lively curiosity in his constant experiments and some mysterious depth of their imaginative value… He sought out his own untrodden path of adventure, attempted marvelous experiments in colouring and made fantastic trials in the magic of light and shade.”

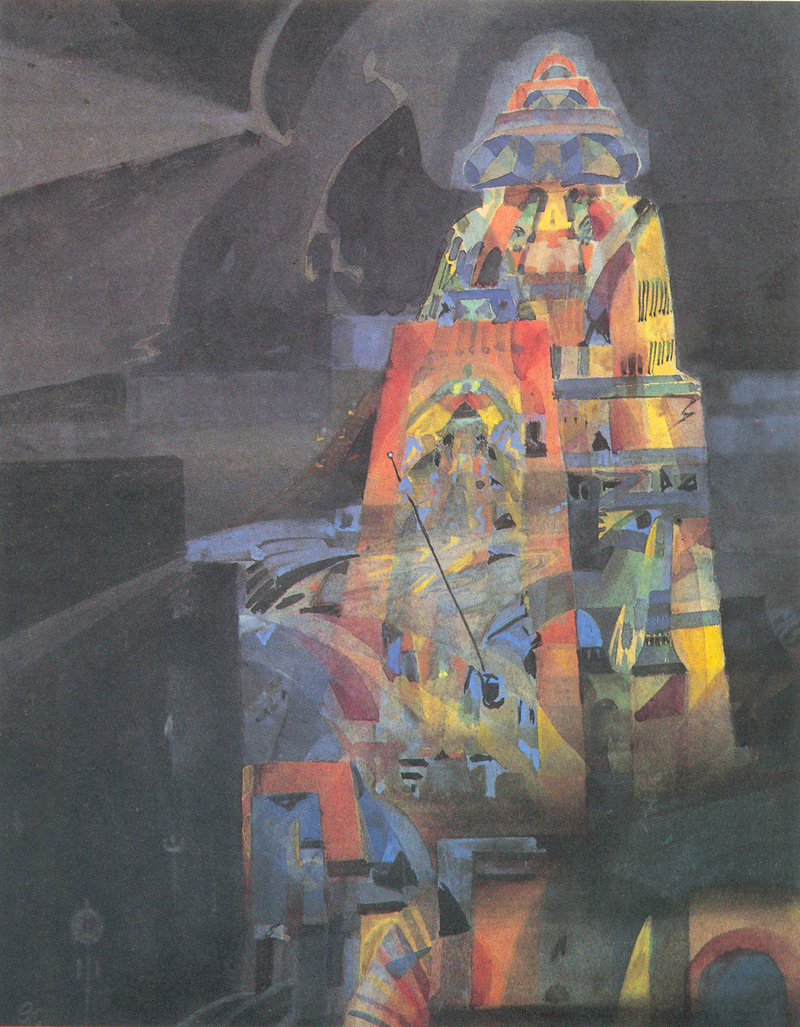

Temple Cubistic A watercolour by Gaganendranath

Added to this peculiar approach towards life, Gaganendranath brought a genius for line, which, without being facile, is so quick to capture the movement of forms that it seems perfectly suited to the real conglomeration of the Bengali scene as it passed before him. He seems to have been observant in the extreme. Dr. Sen tells us while Kshetra, the local bard, was narrating his mythological stories before Gaganendranath and his family; the artist fixed each gesture of the narrator “with a rapid movement of his pencil”. These pencil sketches seldom left the possession of their maker. He never copied any picture. His searching eyes, even when he was engaged in very serious business, followed every person and noticed his peculiarities of speech, of laughter and of expressing annoyance. He had a friend called Moti Babu who did various things for him in the family. Gaganendranath would tease him slightly and excite Moti Babu into a rage. At that stage, he would move his pencil rapidly and finish a sketch of the victim.

Not only did he do this sketching while he was staying at home, hearing legendary tales and songs, but he took a sketch book with him wherever he went. Dr. Sen remarks on the “critical keenness” of Gaganendranath which was to find expression in the cartoons.

“I remember an amusing cartoon in which an orthodox and dignified looking man, with beard and moustache and spectacles, was seen proceeding through a public thoroughfare along with the crowd. While walking, his eyes caught the sight of a woman, looking out from the window of a road-side building and through absent-mindedness one of his feet stepped into a drain. Gagan Babu would at once detect the sham and unreal from anything he saw and expose it in his cartoons to be laughed at. One day I saw him drawing the picture of a Calcutta road. It was jammed with vehicular traffic of all descriptions—motor cars, motor lorries, hackney carriages, but they were all motionless. In front of all these, there was at a little distance, a bullock cart across the road and the driver was chewing and enjoying the juice of a sugar-cane with his eyes half-closed, unmindful of the deadlock created by him.”

It was from this kind of make up in the artist, therefore, that there resulted the series of cartoons included in the books which I have referred to and others which he scattered in the various collections of Bengal or are lost to us through carelessness and vandalism.

I have pointed out that the actual approach of the artist towards his material is through the vital structure of lines, surfaces, forms and colours. Gaganendranath seeks to approach reality with a highly skilled use of his media. And he cuts through to social facts with a pen which becomes rather like a sword hacking away all vanity, imitation and tight rope walking. Thus through a straightforward assemblage of line and colour he gets down to fundamentals and creates a spiritual art which synthesises objective reality with his subjective vision. There is no deception and very little clever artifice employed in these pictures. In fact, the measure of the universe is here not a mature knowing man, but the innocent child, with the same spontaneous and vivid realisation of the awkward hypocrisies of society that a child often displays in its honest horror at all incongruities.

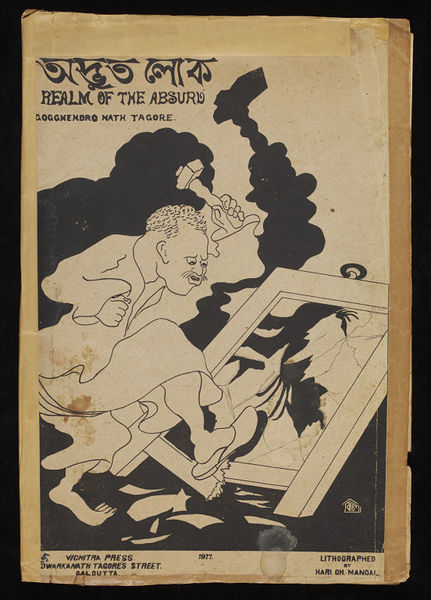

The Offending Shadow This cartoon of a man smashing up his own reflection in a mirror, even as his own shadow behind him still looms large made up the cover of Gaganendranath Tagore’s Realm of the Absurd, the first book of caricature he published in 1915. The book contained 16 lithographs satirising the caste system, the hypocrisy of Hindu priests and the affluent and anglicised Bhadra Log.

And thus is created a new fantastic world, with which the artist plays, in his role, first as a buffoon, then as a bitter critic of the megalomaniacs, both politicians and men of religion, who create the confusion, unrest and insanity which dominates our world and who bring about the frenzied atmosphere in which chaos and disunity crush all beauty and tenderness. In this way, the original image of beauty in order, which is perceived, is hinted at, and all the values, which have been crushed beneath the reins of the twentieth century society of India, begin to emerge as though by implication. The feelings that men have lost are transformed through the catharsis of horror into a kind of balance in which men might be able to live nakedly among men.

Through the presentation of his feelings and ideas there emerges a style in the drawings which is almost the cumulative attitude of Gaganendranath towards art. In spite of the variety of moods and the changes of attitude, there arises a total attitude towards drawing which absorbs the didactic element of his content into a coherent technique. And although the artist was to change his style in his various experiments in colour later on, the cartoons did not show any ambivalence in the whole process by which Gagan Babu took the world into himself and then spat it out. Therefore the style of cartooning associated with Gaganendranath occupies a uniquely individual position in the history of caricature in our country.

There is a hybrid Bengali representative of the Bhadra Log, the new middle class, standing on the rostrum, half of his body clad in kurta and dhoti and the other half in English frock-coat and trousers. This gentleman is the hydra-headed monster who appears again and again in the cruel satire on sartorial manners in Gagan Babu’s portfolios.

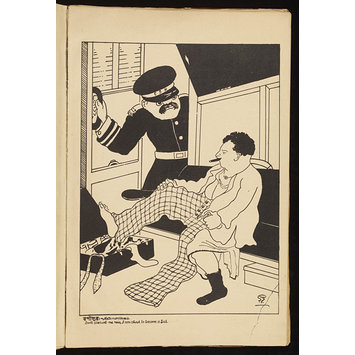

Metamorphosis A man sitting in a colonial Indian train carriage – where compartments were often divided on the basis of race and guards were usually of Anglo-Indian descent – is changing hurriedly from his dhoti into Western attire as the guard looks in. The caption reads: “Don’t come into the room, I’m about to become to become a Sab.”

Let us see the world which Gaganendranath creates:

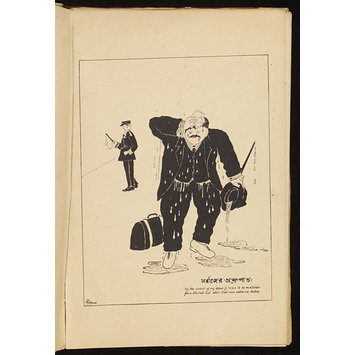

There is a hybrid Bengali representative of the Bhadra Log, the new middle class, standing on the rostrum, half of his body clad in kurta and dhoti and the other half in English frock-coat and trousers. This gentleman is the hydra-headed monster who appears again and again in the cruel satire on sartorial manners in Gagan Babu’s portfolios. For instance, we see him in the Second Class railway compartment reserved for Indian gentlemen dressed in a sports jacket and plus fours, his hair trimmed like the Tommies, a cigar in his hand, announcing to the gentleman in dhoti, who wants to enter with a hand-bag and Henri Bergson’s book on Laughter: “Not here Baboo”. Again, he is seated in the restaurant near the Bar Room of the High Court with his mocking bird’s nose thrust out from the English lawyer’s suit, to which the artist has added the tail of a peacock, announcing Rule No. 7: “Indian dress not admitted, Borrow or Steal”. The borrowed plumes are analysed by the artist to more intensive effect in the garden party where he deposits a puzzle for the younger generation in the question: “Find the Indian”, for all the visitors to the party except the bearer, are dressed in European costume. In another picture still this worthy asks the railway official not to disturb him while he is changing from dhoti into trousers because he is “About to become a Sab”. Not all his labour in ‘becoming a Sab’ is rewarded, however, because in another picture the worthy in English clothes is shown sweating all over, and Gagan Babu adds the caption: “By the sweat of my brow I tried to be mistaken for a Sab but still that man calls me a Baboo”. The contrast of the dignity of a pure Indian style of dress for men and women is shown in yet another picture against the mixed attire of the corpulent monsters who parade the streets. Further still the irony is visible in the young man in tails dancing with a female who has adapted her saree to the European style of frock. The last sartorial comment is on the first appearance of a Bengali Governor in top hat and morning suit, which makes the artist ask: “Where is His Excellency”? Gagan Babu himself draws the moral from the shooting of the guns, which once announced the coming of such exalted personages, in the words of Mark Twain: “Noise proves nothing. Often a hen, who had merely laid an egg, cackles as if she has laid an asteroid”.

By The Sweat Of My Brow A man dressed in a Western three piece suit and carrying a hat, briefcase and walking stick is sweating profusely. In the background a train guard waves a white flag. The caption reads: “By the sweat of my brow I tried to be mistaken for a shaheb but still that man called me Baboo.” ‘Shaheb’ is a word used to indicate those of European descent. ‘Babu’ or ‘Baboo’ was originally a term of respect but, in the early 20th century, was used to deride Indians adopting Western customs.

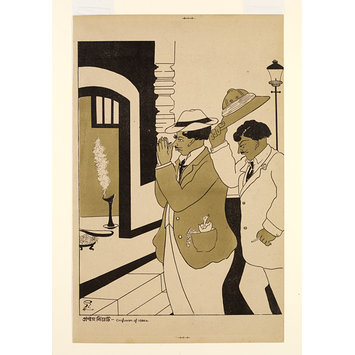

In the attack on religion, Gaganendranath seeks to create his own religion of purity and good conscience through the exposure of inconsistencies of the priest craft. The simplicity of line in these cartoons is also the hall-mark of the artist’s clarity. For instance, no one can mistake the dirt introduced into the ritualistic objects by the bloated demon who, in his capacity as priest, performs purification for the worshippers in lieu of bags of gold. Nor is there any religion left if the Brahmin smears cow-dung on to the flowers in the interest of cleanliness. As to the husband who is horrified at the news that two soldiers were caught fishing in the sacred river near Haridwar, while his devout wife is chopping fish in the kitchen before him, there is no comment necessary. Similarly the coins thrown at the temple in the cartoon “Profitable Devotion”, speak for themselves. The “Imperishable sacredness of the Brahmin”, feting himself with wine, women and flesh, is demonstrated by the artist with an inimitable exaggeration of the priest’s face, so that it resembles one of the doors of hell in the Hindu cosmogony. The “Millstone of caste” crushes everything so cruelly before us in the picture of that name that we hear the howling and screeching and the groans of the oppressed. In short, priests are to Gaganendranath an insensitive tribe who crush all sensibility. But their hypocrisy is surpassed by that of those two devotees who come dressed, one in a sola hat and the other in a felt hat, and join hands before the mandala of the Gods.

‘Confusion of Ideas’ Two babus visit a temple in Western attire. One has a newborn chick bursting out of the egg in his jacket pocket (a site that would be disturbing for vegetarian Hindus). The other, while raising his sola topee to the deity holds a cigarette in his other hand.

The confusion of ideas seems monstrous enough in the sphere of religion, but in the sphere of politics it is worse confounded. There has been a shake up of the old life in Bengal and the way in which the people are upturned from their moorings is shown admirably in the cartoon entitled, “State Funeral of H. H. Old Bengal”, with the caption, “Pity is for the living, envy is for the dead”. And the pity for the living increases when we see the human being turned into an “Automatic Speech-making machine (a wonderful scientific invention by an Edison of Bengal) which will enable any speechless Maharaja, Zamindar, or Member of Council to deliver a speech of any length and breadth without the aid of a highly paid Private Secretary or Speech Writer”. The artist given adequate direction for the use of the machine and the mockery becomes more bitter in the picture. “Collapse of the Artist—after his visit to the Legislative Council—the endless speeches wriggling all around the point have given him the creeps”. Gaganendranath was so outraged by the stupidity around him that he devoted one volume of his cartoons entirely to a number of Reform Screams.

In this series the most vital is the “Premier Scream”, which comments on the Montague-Chelmsford reforms by showing “Montford in labour” producing the baby “Deficit”. The administration is castigated for wanting to extract their pound of flesh to make up the drain in the country’s economy. And the police is shown oppressing the skeleton-like peasantry. In view of all this the caricature of Lloyd George paying lip sympathy to the Indian people while he wields a whip against them shatters all the vaunting of the politician. And the cowardice of the middle class is shown in the way it advises the lion-faced labourer who wishes to go on strike not to strike because ‘it is a loser’.

As I have already indicated, Gaganendranath was not only conditioned by sight-seeing but was an artist with an insight. He knew how the process of disintegration was being perpetrated. The way he shows the youth of the country being ground under the weight of books and turned into puppets, shows how deep his awareness of the rot was. He takes to task the Vice-Chancellor of Calcutta University for scattering sweetmeats to the doomed generation. Equally, he attacks the politician for giving the child a match-box to make a bonfire of the books; and he does not spare the parents who, while sending their son to read Romeo and Juliet, buy a new wife for him long before the coffin of the first has been taken to the crematorium.

Gaganendranath seems to have had a special sympathy for women, always the neglected half of our nation though fettered with amorous attention. Remark the gentleman who is shown standing away from his wife and child on the railway station, or his counterpart who considers his whole household a nuisance, to another gentleman who is exchanging glances with a woman on the balcony in a kind of “way side digression”. The concentrated attention of all the men in the railway compartment on the two unfortunate women who pass by shows the universal sex frustration of our people in a masterly manner. And in the “matrimonial scream”, where the bride faces up to the “Rising Sun-in-law of Bengal”, the artist drives the point home with the words; “the social cruelties perpetrated on the father of the marriageable girl drives the sensitive daughter in the arms of Mr. Kerosine in order to save her father”.

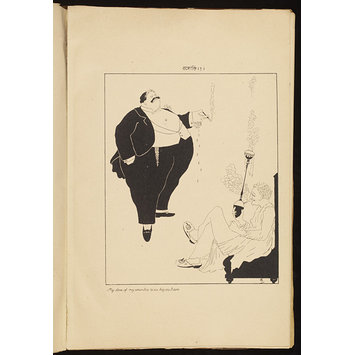

The whole humbug is further exposed through delightful intimate studies. One of the most beautiful sketches shows the typical modern politician boasting to the artist: “My love of my country is as big as I am”. The same gentleman is shown with his vultures sucking up the life-blood of the peasantry while he beats them up with a stick.

My Love of my Country is as big as I am Another caricature resembling the Maharaja of Burdwan, a large man in Western evening-wear, smoking a cigarette in a cigarette holder and telling a lean man in Indian clothes (who resembles Gaganendranath himself) and smoking a hookah: “My love of my country is as big as I am.”

Towards the end of his life Gaganendranath was constrained to protest against almost everything. The screams became very shrill. Even the poet Tagore is shown in the “Poetical Scream” ascending in “his latest flight”, which is obviously a comment on the poet’s bombastic equivocations through which one did not know whether he was for co-operation with the British Raj or for non-co-operation. Sir P. C. Ray, the scientist, also gets it for his chauvinism in the “Chemical Scream”. And the botanist J. C. Bose is shown in the “Nature Scream” where inanimate nature responds to the Professor’s political slogans.

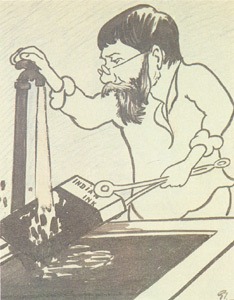

‘Indian Ink’ The chemistry professor (and to-be industrialist) Prafulla Chandra Ray trying to wash out “Indian Ink”. The caption reads: “Out Damned spot, Out, I say!” This is a reference to the scientist’s new inventions during the Swadeshi movement, which were purposeless from the point of view of indigenous manufacturing.

I believe that Gaganendranath had a deeply generous attitude towards people, in spite of the cruelty he so often brought to his delineation of men’s follies. “To be foolish is human”, he quotes from Rabindranath Tagore, “to laugh at it is more so”. This seems to be his justification, or as he quotes Mark Twain to say: “Everything human is pathetic. The secret source of humour is not joy but sorrow. There is no humour in Heaven”.

Inanimate Scream Inanimate Nature Responding to Professor Jagdish Chandra Bose’s Musings.

All the same, such phrases do not cover the quality of tension in his make up which led to the caricatures that I have described above. The spiritual crisis in which he seems to me to have lived, and through which he seems to have expressed himself as an artist, is far more truly described in certain words of the German philosopher Schelling:

“To be drunk and sober, not in different moments, but at once in the same moment—this is the secret of true poetry…”

And what is true of poetry is also true of art.

Gaganendranath Tagore

Considered a founder of the English-language Indian novel, Mulk Raj Anand was born in Peshawar, in 1905, and educated at the universities of Punjab and London. After earning his PhD in philosophy in 1929, Anand began writing for T.S. Eliot’s magazine, the Criterion, as well as books on cooking and art. Recognition came with the publication of his novels Untouchable (1935) and Coolie (1936). His other major works include his well-known trilogy: The Village (1939), Across the Black Waters (1940) and The Sword and the Sickle (1942). By the time he returned to India in 1946 he was easily the best-known Indian writer abroad. Making Bombay his home and centre of activity, Anand threw himself headlong into the cultural and social life of India. He founded and edited the fine art magazine Marg, and has been the recipient of the Sahitya Akademi Award, several honorary doctorates and other distinctions. You can read more about him and his work here, here and here.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1100–1199 CE | |

|

1100–1199 CE |

| Topography as History: Reading Kashmir through Rajatarangini | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1828-1843 | |

|

1828-1843 |

| Scandal of Manners: ‘Urinating Standing Up’ | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1910-1950 | |

|

1910-1950 |

| Forging Unity: Vallabhbhai Patel and the Politics of Nationalism | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Patriarchal Lechery | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1943-1945 | |

|

1943-1945 |

| Origin Of The Azad Hind Fauj | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1950-1951 | |

|

1950-1951 |

| Panikkar’s 1950 Ordeal: China’s Moves, Family Crisis, and Diplomatic Distrust | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

You need to take part in a contest for one of the greatest blogs on the web. I am going to recommend this blog!