On March 8, 1936, the Indian Government detained Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose under an anti-terrorism act, Regulation No. III of OP 1818.

At the time, the ICS officer, Sir Hugh Stephenson, who had served as Governor of Orissa and Burma said, “Subhas Chandra Bose could not be conceived of being implicated in any terrorist crime. His arrest and detention were due to his great love for his country, his high intellectual power and his great organising abilities, his unbounded influence over the youth of the country and the great love and respect in which he is held by his countrymen at large.”

Why does this incident have resonance in the India of today, 125 years after Bose’s birth on January 23, and 74 years after the British quit India?

Well, coming to the present, there are literally hundreds of Indians languishing in jail for years under similar draconian laws, such as the UAPA. There have been arrests under “black laws” in Kashmir, in the North East, in UP, in Maharashtra, in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, in Madhya Pradesh, in Delhi…

The detainees have been accused of terrorism, of sedition, of offending religious sentiments, what have you. In the latest round of this demonization, the NIA is now investigating farmers protesting against new farm laws, and there is a concerted campaign in the state-influenced media to brand them anti-nationals and Khalistani.

The list of current detainees includes intellectuals, college professors, doctors, cartoonists, stand-up comedians and other persons who live their lives very publicly. The charges of terrorism are absurd. So are the charges of sedition.

But bail applications have been routinely opposed and refused in these cases, even when the charges are patently absurd (including those made under non-existent sections of the law), when the detainees are medical risks, and when the charge-sheets admit there is no concrete evidence.

At the same time, members of the ruling party who face concrete charges of terrorism backed by evidence, and of rioting, and other violent crimes have had cases against them withdrawn, and in at least one case, entered Parliament.

This injustice perpetrates a horrible tradition where men like Jayaprakash Narayan who spoke up against authoritarianism were held under the MISA in the 1970s. The Emergency ended in 1977 but the mindset of the Emergency never really went away. Successive governments, across party lines, both in the centre and in states have used draconian laws to silence dissent, threaten and punish free speech and suppress the aspirations of civil society. It has also been embraced enthusiastically by the ruling party of the moment, which ironically contains a number of people who had to run and hide from similar black laws during the Emergency.

In most of these cases, the people being punished have the unpleasant habit of speaking truth to power, or working with marginalised communities, or demonstrating against undemocratic legislation.

This is why the case against Bose in 1936 is relevant today.

As Satyendra Chandra Mitra wrote: “But nothing can completely satisfy the public except the repeal of all laws, regulations and other measures sanctioning the arbitrary imprisonment of men and women for indefinite periods without trial and conviction according to ordinary judicial processes.”

Black laws like this should not exist in any nation that claims to be a democracy. And, any law that does exist, should be applied even handedly without fear or political favour.

—Devangshu Datta

The moment Sj. Subhas Chandra Bose touched the Indian soil on the 8th of March, he was arrested under Regulation No. III of 1818. We would like to discuss here primarily the legal and constitutional aspect of his detention.

The Home Member of the Government of India has declared in the Legislative Assembly that Sj. Bose was involved in a terrorist crime. There is clear provision both in the Bengal Criminal Law Amendment Act and in the Bengal Suppression of Terrorist Outrages Act to deal with offenders who are in any way connected with terrorism. The provisions of these enactments are so wide and all-comprehensive that any activities connected with terrorism can be effectively dealt with under the various sections.

If Government seriously maintains that Sj. Subhas Bose is in any way connected with terrorism, it is the bounden duty of the Government to deal with his case under any of those emergency legislations. The only ground for not proceeding against him under the Emergency Laws, as stated by the Hon’ble Home Member, is that the sources of information might be dried up and the life of the witnesses would be endangered. The argument of the Law Member Sir Nripendra Nath Sircar that the reason for not enforcing the Criminal Law Amendment Act was that Government out of kindness was giving him better facilities due to his higher station in life is not only frivolous but also very unkind.

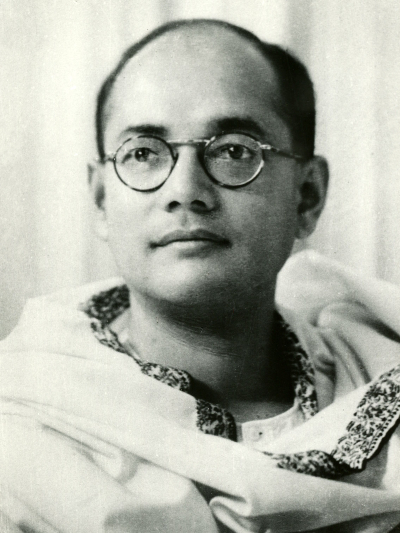

Subhas Chandra Bose

It was demanded by Sj. Bose and all his friends as well as in the public Press that he should be placed under regular trial. We propose to quote some of the sections from the recently enacted Emergency Laws to show conclusively that the apprehensions of the Home Member of the Government of India are also without any foundation.

Under section 31 of Bengal Act XII of 1932 the trying courts have power to exclude persons or the public from the precincts of courts. The section runs thus:

“The Special Magistrate may, if he thinks fit, order at any stage of a trial that the public generally, or any particular person, shall not have access to, or be or remain in, the room or building used by the Special Magistrate as a court.

“Provided that where in any case the public prosecutor or Advocate-General, as the case may be, certifies in writing to the Special Magistrate that it is expedient in the interests of the public peace or safety or of the peace or safety of any of the witnesses in the trial that the public generally should not have access to, or be or remain in, the room or building used by the Special Magistrate as a court, the Special Magistrate shall order accordingly.”

There is clear provision both in the Bengal Criminal Law Amendment Act and in the Bengal Suppression of Terrorist Outrages Act to deal with offenders who are in any way connected with terrorism… The argument of the Law Member Sir Nripendra Nath Sircar that the reason for not enforcing the Criminal Law Amendment Act was that Government out of kindness was giving him (Bose) better facilities due to his higher station in life is not only frivolous but also very unkind. It was demanded by Sj. Bose and all his friends as well as in the public Press that he should be placed under regular trial.

The same powers of exclusion of the public for safety of witnesses were extended to trials by commissioners by Secs. VIIIA and VIIIB by the Bengal Criminal Law Second Amendment Act, 1932. So it is clear that the plea of the safety of the witnesses and the fear of drying up of the sources of police information are now absolutely groundless.

The court will certainly take the initiative or in any case the Public Prosecutor will not hesitate in the least to have in-camera trials when there is the least danger to the life of the witnesses. It is a fact that various terrorist offences have been tried in Bengal by Special Commission under these sections of Emergency legislation and no witnesses to our knowledge during recent years have been murdered or interfered with. The Bengal Suppression of Terrorist Outrages Act is so drastic that under its provision any officer of Government authorized in this behalf may arrest and detain, have power to take possession of immovable and movable properties and have also the power to prohibit or limit access to any building or place in their occupation and may requisition the assistance of any person and can prohibit the use of any place and can take possession of places used for purposes of certain association and also have the general power of searches, can impose collective fines on inhabitants of a locality, and can make offences cognizable and non-bailable, while under the ordinary law they are not such.

Subhas Chandra Bose arrives at Calcutta’s Dum Dum Aerodrome

As we have already quoted, special arrangements have been made for the trial of such cases and of special rules of evidence to be adopted, if found necessary, and of trial en camera.

We are not contending about the rigour of the law. But we maintain that when the scope of the law is so wide and every safeguard has been provided for the protection of witnesses and against the fear of drying up of the sources of police information, it does not lie in the mouth of the Government now further to plead that a person like Sj. Subhas Chandra Bose cannot have a trial.

During recent years there have been several big conspiracy cases connected with terrorist crimes which have been tried under the Emergency laws and convictions have been secured, unattended by any of the evil effects as apprehended by the Home Member. In the eye of the law there should be no distinction between one person and another. If other people can be tried and convicted with impunity under the Emergency Laws, why should Sj. Subhas Chandra Bose, who does not pray for any special mercies, be spared the consequences of his alleged action? We know from our long and intimate acquaintance with Sj. Subhas Bose that he is incapable of having any connection with terrorist crime, and that is the reason why we challenge Government to deal with him legally. We shall now show that Regulation No. III of 1818 is inapplicable in his case.

In the preamble to the Regulation it is stated that it would apply:

(i) “For the due maintenance of alliances formed by the British Government with foreign powers.

(ii) “For the preservation of tranquillity in the territories of Native Princes entitled to the protection of the British Government.

(iii) “For the security of the British Dominions from foreign hostility or internal commotion.’’

It is on one of these three grounds that a person can be arrested and kept under detention under Regulation III.

We maintain that when the scope of the law is so wide and every safeguard has been provided for the protection of witnesses and against the fear of drying up of the sources of police information, it does not lie in the mouth of the Government now further to plead that a person like Sj. Subhas Chandra Bose cannot have a trial… We know from our long and intimate acquaintance with Sj. Subhas Bose that he is incapable of having any connection with terrorist crime, and that is the reason why we challenge Government to deal with him legally.

We shall try to show that none of these provisions are applicable in Sj. Bose’s case. When this Regulation was made there were in the country numerous and powerful feudatories of the sovereign recently conquered and several ceded provinces, nominally subjects of His Majesty but from whom danger might at any time be apprehended. So this regulation was not intended for application against political agitators, sedition-mongers or terrorists.

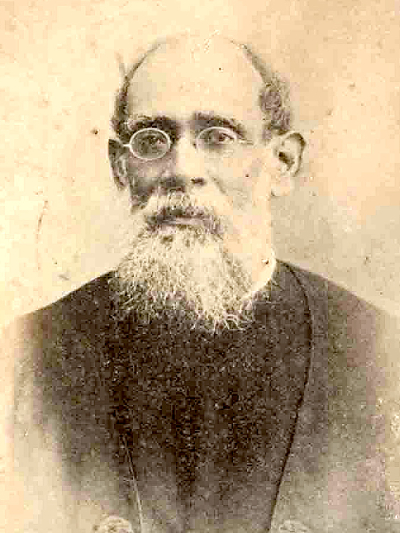

Victims of Regulation III First Row (L to R): Lala lajpat Rai, Sirdar Ajit Singh, Subhas Chandra Bose; Second Row (L to R): Sj. Krishna Kr. Mitra, Ashwini Kumar Dutt, Sj. Pulin Behary Das.

The first application of this regulation was in July, 1869, in connection with the Wahabi movements when Ameer Khan was a victim of Regulation III in Bengal. The next case was in 1897 when the two Natu brothers of Poona were dealt with under the same regulation. In 1907, Lala Lajpat Rai and Sirdar Ajit Singh were deported under the provision of the Regulation and in 1908 the late Aswini Kumar Dutt, Sj. Krishna Kr. Mitra, Raja Subodh Ch. Mallik, the late Shyam Sundar Chakravarty, Sj. Pulin Behary Das, Sj. Satish Ch. Chatterjee, the late Monoranjan Guha Thakurta, Sj. Sachindra Prasad Bose, and Sj. Bhupesh Chandra Nag were deported under the same regulation.

During the Great War numerous persons were dealt with under the same regulation.

So there is no reason why the ordinary laws should be suspended at a time when there is no war in which England is involved or there is any insecurity of the British Dominions “from foreign hostility and from internal commotion.”

We do not know what were the charges framed against Sj. Subhas Chandra Bose for his arrest and detention. All that we can gather from the speeches of the Home Member of the Government of India is that Mr. Bose is guilty of possessing intellectual powers and organizing capacity and the bold assertion is that he is deeply involved in terrorist crime.

During the recent discussion on the question of the repeal of repressive laws in the Legislative Assembly both the Home Member and the Law Member made large promises that they would substantiate by facts the complicity of Sj. Subhas Chandra Bose with terrorist crime.

From the scrappy report that appeared in the daily press it appeared that the only point there to be made was about the letter of Sj. Krishnadas, the paid secretary of the All-India Congress Office, who in one of his intercepted letters to Gandhiji wrote that Sj. Subhas Chandra Bose was connected with the Jugantar group.

Krishnadas himself in a recent statement said that his information about several schools of revolutionaries in Bengal was gathered by him in prison from all sorts of people including a host of Government emissaries and agent provocateurs. He made it clear that he had no direct knowledge of Sj. Subhas Chandra Bose’s complicity with the Jugantar party of the revolutionaries and what he wrote was based on hearsay or gossip.

All that we can gather from the speeches of the Home Member of the Government of India is that Mr. Bose is guilty of possessing intellectual powers and organizing capacity and the bold assertion is that he is deeply involved in terrorist crime… From the scrappy report that appeared in the daily press it appeared that the only point there to be made was about the letter of Sj. Krishnadas… who in one of his intercepted letters to Gandhiji wrote that Sj. Subhas Chandra Bose was connected with the Jugantar group. Krishnadas himself in a recent statement… made it clear that he had no direct knowledge of Sj. Subhas Chandra Bose’s complicity with the Jugantar party of the revolutionaries and what he wrote was based on hearsay or gossip.

It is to be regretted that Government sometimes comes to conclusion from such flimsy and unsubstantial evidence. It is much to be regretted that the lives and liberties of such respected citizens are jeopardized on such untrustworthy evidence, and that Government could not disclose any better evidence than the flimsy hearsay evidence contained in the letter of Sj. Krishnadas. All this would appear to show that their declaration of having definite proof against Sj. Subhas Chandra Bose is a mere myth. They dare not face a trial in open court when the witnesses may be properly tested by thorough cross-examination.

With a view to find out if any substantial allegation has been made out against Sj. Subhas Chandra Bose, we have carefully gone through the Note presented by the Secretary of State for India on terrorism in India which he laid before the Joint Committee on Indian Constitutional Reforms.

There are a few references to Sj. Subhas Chandra Bose in that note and we shall presently mention them to evaluate their worth. On page 333 of the said report it is said:

“According to the confession of Dr. Narayan Roy, ‘his mind had been inflamed’ by speeches made by Subhas Chandra Bose and another well-known political agitator.”

If those speeches of Sj. Subhas Bose were seditious which inflamed the mind of Dr. Narayan Roy, it was the clear duty of the Government to prosecute him for sedition. But if they have failed to do so, it is no use arguing now that he was involved in terrorism.

On page 348 it is stated:

“Dr. Bhupendra Nath Dutta (an old terrorist), Kanai Lal, Subhas Bose (detained twice under Regulation III), Bankim Chandra Mukherjee and others devoted their energies, from varying motives, to the development and growth of organizations based on communist or semicommunist ideas.”

There was a conspiracy case known as the Meerut Conspiracy case in which alleged communist leaders of varying degrees were arraigned and found convicted, but Sj. Subhas Chandra Bose is not one of them. In the same report it is stated:

“At the instance of Subhas Chandra Bose, Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru presided over the All-Bengal Students’ Conference in 1928 and in his speech advocated communism and internationalism for India. Immediately on his departure an Independence League was started by Subhas Bose with a number of ex-detenus and State Prisoners. They drew up a manifesto on Bolshevik lines, which evoked some protest. When later, however, Jawahar Lal himself started the ‘Independence for India League,’ having for its object the achievement of Swaraj for India, with the help and support of Kanai Ganguli and Bhupendra Dutt, it met with strong opposition from Subhas Chandra Bose and his followers, who now formed a separate ‘Independence for India League’ in Bengal.”

Bhupendra Nath Dutta

“At the instance of Subhas Chandra Bose, Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru presided over the All-Bengal Students’ Conference in 1928 and in his speech advocated communism and internationalism for India. Immediately on his departure an Independence League was started by Subhas Bose with a number of ex-detenus and State Prisoners. They drew up a manifesto on Bolshevik lines, which evoked some protest.” —Note presented by the Secretary of State for India on terrorism in India which he laid before the Joint Committee on Indian Constitutional Reforms

In a later passage it is said:

“During the Jute Mills Strike of 1929 there were indications that the Congress Scheme was to get the intelligentsia to organize a mass upheaval through the youth and students’ and volunteer movements with a view to coerce the Government. The scheme did not materialize and the Meerut case has for the time being ended attempts to form organizations on communist lines.”

There are other passages as on page 338 as follows:

“To complete the picture it is necessary to say a word about the connection of the Congress Committee, and the Calcutta Corporation and the manner in which subversive movements in general and terrorism in particular have received encouragement from the Corporation.

The present Calcutta Corporation was the creation of the Act of 1923. In 1929 the Congress under the leadership of late Mr. C. R. Das obtained a large majority in it and since then has dominated it under the leadership successively of late Mr. J. M. Sen Gupta and Mr. Subhas Ch. Bose, both ex-presidents of the Bengal Provincial Congress Committee and of Dr. B. C. Roy. The former two were bitter critics of Government and at various times were incarcerated under Regulation III of 1818 and the latter suffered imprisonment during the Civil Disobedience Movements.”

Those are some of the specimens cited by the Secretary of State as indicative of terrorism in Bengal. It has been opined that:

“It is true that the Congress formally dissociated itself from terrorism but it was equally clear that, if some of the workers and leaders of Congress were given a free hand, they would not be averse to giving their general support to terrorism.”

This is the bold inference of the Secretary of State on Mahatma Gandhi’s Civil Disobedience Movement, which, according to him, “aroused anti-British sentiment and a spirit of lawlessness in the province” and that “seditious literature of the most violent description was being broadcast in the shape of pamphlets and books”. It is certainly claimed that the Government saved the situation by passing of ordinances and emergency legislation and the “situation had apparently greatly improved” and we do not see any reason why the law was not applied against Sj. Subhas Chandra Bose, if the Government considered him guilty, and why the old Regulation, which was not designed to meet such situations, was misapplied. Sj. Bose has been suffering from serious intestinal troubles for the last four or five years and he was away from India for his treatment.

His immediate arrest on his return from the continent of Europe to his native land after a prolonged absence makes it clear that his detention is not due to his activities but to his pronounced views about Swaraj for India. That Government officials are not known for consistency or accuracy of their remarks about Indian leaders will be evident from the following anecdote.

Lord Morley in his letter to Lord Minto wrote:

“You have nine men locked up a year ago by ‘letter de cache!’ because you believed them to be criminally connected with criminal plots, and because you expected their arrest to check these plots.”

“You have nine men locked up a year ago by ‘letter de cache!’ because you believed them to be criminally connected with criminal plots, and because you expected their arrest to check these plots.” — Lord Morley in his letter to Lord Minto

But speaking on the 7th January, 1924, on the Ordinance Bill in the Bengal Legislative Council Sir Hugh Stephenson referred to those arrests and said that Sj. Krishna Kumar Mitra and others were deported because of violent boycott speeches and not for their connection with terrorist crime.

Lord Minto

But speaking on the 7th January, 1924, on the Ordinance Bill in the Bengal Legislative Council Sir Hugh Stephenson referred to those arrests and said that Sj. Krishna Kumar Mitra and others were deported because of violent boycott speeches and not for their connection with terrorist crime. We quote his exact words:

“The first two are those of Babu Aswini Kumar Dutta and Babu Krishna Kumar Mitra. It has been said that no one will believe that they had anything to do with terrorist crime and that therefore the secret information of the police must have been false and Government may equally well be deceived by such false information now.

Sir Hugh Stephenson

“I never knew Babu Aswini Kr. Dutta but I hope Babu Krishna Kumar will not be ashamed if I call him my friend and I wholeheartedly acquit him of sympathy with terrorist crime, but as far as I know no one has ever accused him or Babu Aswini Kumar Dutta of promoting crime still less of taking part in it. The Bengal Government asked for the arrest under the Bengal Regulation III of 1818 of Babu Krishna Kumar Mitra in 1908 because of his violent boycott speeches and his activity in organising volunteers involved in the danger of internal commotion. In the same way the Eastern Bengal Government asked for the use of the said Regulation in the case of Babu Aswini Kumar Dutta because of his whirlwind campaign of anti-Government speeches and of his control of the Brojo Mohan Institution, from which a stream of Swadeshi preachers was constantly pouring.

“We believe the time will come when an equally highly placed official from his place in the Government will declare that Sj. Subhas Chandra Bose could not be conceived of being implicated in any terrorist crime, but that his arrest and detention were due to his great love for his country, his high intellectual power and his great organizing abilities, his unbounded influence over the youth of the country and the great love and respect in which he is held by his countrymen at large.”

Lord Morley has truly said:

“Excess of severity is not the path to order. On the contrary it is the path to the bomb.”

If Government sincerely believe that Sj. Subhas Chandra Bose is implicated in any terrorist activities, it is the clear duty of the Government to haul him up before a Court of Law. Arbitrary detention for an indefinite period as a regular weapon of Government should now cease. Punishment without trial is abhorrent. Sir Surendra Nath Banerjea rightly said that:

“Security of life and property are the great foundation upon which rests the vast, the stupendous, the colossal fabric of British rule in India. What becomes then of these inestimable blessings, if at any moment your property may be confiscated, you may be arrested, kept in custody for months together without a trial and without a word of explanation? What becomes of the boasted vaunt of the boon of personal liberty and personal security under British rule under the circumstances?”

Sir Surendra Nath Banerjea

“Excess of severity is not the path to order. On the contrary it is the path to the bomb.” —Lord Morley

Arbitrary detention for an indefinite period as a regular weapon of Government should now cease. Punishment without trial is abhorrent.

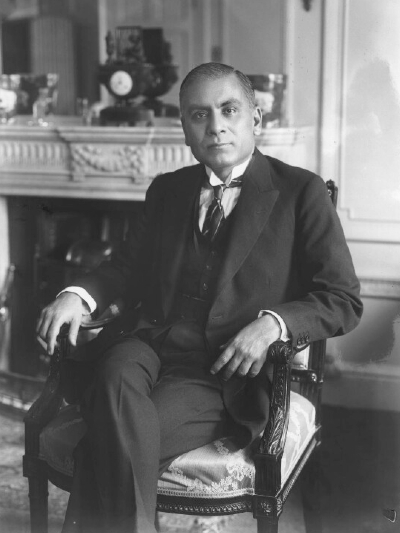

Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru

The Repressive Laws Committee was constituted in compliance with a resolution passed by the Council of State in 1921 with Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru, the then Law Member, as its President. In their report they said that Regulation III of 1818 should not, in future, be put in operation anywhere, except the North-western Frontier Province. The Government of India accepted the recommendations of the Committee. But it seems they have resiled from their former position and are now making free use of the old Regulation.

All that we want is that there should be the rule of law and persons should not suffer merely for their love of their country.

Sarat Chandra Bose

It is some relief that Mr. Subhas Chandra Bose has been removed from the sultry climate of Poona, where he was confined in Yeravada Central Prison, to the cool heights of Kurseong in the Darjeeling district, where he is interned in the house of his brother Mr. Sarat Chandra Bose, who had himself been interned there.

The (unproved) allegations made by Government against both the brothers are similar. Both in turn have been interned in the same town and house. May it be hoped then that Mr. Subhas Chandra Bose will be now released as his brother was? That will give some satisfaction to the public.

But nothing can completely satisfy the public except the repeal of all laws, regulations and other measures sanctioning the arbitrary imprisonment of men and women for indefinite periods without trial and conviction according to ordinary judicial processes.

May 1936

The Modern Review was founded in 1907 by Ramananda Chatterjee, who also founded and edited the Bengali magazine, Prabasi and the Hindi magazine, Vishal Bharat. All three periodicals can be best described as journals of opinion.

The Modern Review published essays by practically every well-known leader of the Indian nationalist movement, along with the views of foreign sympathisers. It also carried rousing editorials from Ramananda Babu himself. After his demise in 1943, his son Kedarnath carried on the good work until he passed away in 1965. The magazine also published fiction, book and art reviews, travelogues, etc., including essays by pioneers like the anthropologist Verrier Elwin and historian, Jadunath Sarkar.

Ramananda Babu allowed his contributors to present every shade of opinion and argue their cases, while ensuring the magazine itself maintained an impartial editorial stance. He was happy to publish long multi-issue arguments between luminaries like Tagore-Gandhi and Subhas Bose-Sardar Patel about the shape and direction of the nationalist movement. Contemporary opinions about topics such as education, women’s rights, the relations between religions and castes, electoral politics, India’s place in the world, and international relations can be accessed and contextualised by leafing through the archives of this journal of record.

—Devangshu Datta

To read a select anthology of articles, interviews, poetry and fiction published from 1907-1947 in the Modern Review, you can buy‘Patriots, Poets and Prisoners’ here.

Satyendra Chandra Mitra was an Indian freedom fighter and advocate, who started his political career as a revolutionary in the Jugantar Party in 1916, was elected Chief Whip of the Swarajya Party in the Central Legislative Assembly and later became the President of the Bengal Legislative Council (of undivided Bengal). He was imprisoned in Mandalay Jail in Burma along with Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose for his nationalist activities. You can read more about him and his work here.

Devangshu Datta is consulting editor and science and technology correspondent at the Business Standard. He is an editor, along with Nilanjana S. Roy and Anikendra Nath Sen, of Patriots, Poets and Prisoners.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1943-1945 | |

|

1943-1945 |

| Origin Of The Azad Hind Fauj | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply