Almost exactly 90 years ago, Albert Einstein and Rabindranath Tagore had a long conversation faithfully recorded in The Modern Review. An unbiased observer reading that, without context, might assume that the two intellectual giants were essentially talking past each other, as they discussed truth, beauty and the divine.

They may well have had some communication issues since neither spoke English as a first language. But this actually serves as a wonderful illustration of two different ways of looking at the universe. And, no, it wasn’t a dialogue that can simply be glibly characterised as East meets West.

A quick look at their backgrounds may be helpful. Einstein was a secular Jew. He never took religion very seriously. If he believed in God at all, it was not in the patriarchal Yahweh of the Torah, who laid down the law to Moses and appeared in a burning bush.

That’s very clear from other statements Einstein made, starting with the off-the-cuff, “Does the Old Man play dice with the Universe?” That was when he was discussing quantum action, with Nils Bohr who responded with the classic: “Don’t tell Him what to do!”

Einstein also said, “I do not believe in a personal God and I have never denied this, but have expressed it clearly. If something is in me which can be called religious then it is the unbounded admiration for the structure of the world so far as our science can reveal it.”

Tagore on the other hand, was brought up in the Brahmo tradition by a great preacher, his father, Maharishi Debendranath. Brahmoism can be described as a Unitarian religion. It acknowledges one Advaita Param Brahma, a formless, eternal creator. The religion is focused on the Vedas, while rejecting caste, food fads, other later Sanatan Hindu writing and customs.

Tagore however broke out of the rather puritanical perspective imposed by his father. He embraced a broader mysticism, some of which he tries to articulate in this conversation. In his play Achalayatan, Tagore created a character, Dadathakur, who may have encapsulated his attitude to religion. Dadathakur is a free spirit who has a joyous, untrammelled direct relationship with the divine, rejecting a narrow rule-and-ritual-bound existence.

The poet set up Santiniketan in Birbhum District, which has a strong baul tradition reaching back to the Bhakti cult with its philosophy of building personal connections to the divine. Birbhum District also has its fair share of tribals who are animists, not mainstream Hindus. Some of that – Bhakti certainly, quite possibly the animistic worship of the divine in the natural – exerted influence on the poet.

But insofar as one can analyse a free-flowing conversation of this nature, the best framework is perhaps provided by a look at the anthropic principle (AP). Although the AP was only defined and articulated from the 1960s onwards, long after the demise of these two, it provides a context that actually allows us to make sense of the conversation.

Tagore was a believer in the Strong Anthropic Principle: The Universe was created the way it was, with natural laws that led to the emergence of sapient life because it could only be observed and appreciated if there was life. According to this philosophical stance, truth and beauty cannot exist in the absence of sentient observers.

There is also a Weak Anthropic Principle which can be defined as a belief that life can only appreciate the wonders of a universe which happens, by some statistical chance, to have natural laws that support life.

Going by this conversation Einstein was not a believer in the Anthropic Principle at all: His position is that the laws of nature are the laws of nature. They exist and they create their own beauty and harmony, regardless of observers.

I hope this helps provide some context for the conversation. Now take a deep breath and dive in!

—Devangshu Datta

TAGORE: You have been busy, hunting down with mathematics, the two ancient entities, time and space, while I have been lecturing in this country on the eternal world of man, the universe of reality.

EINSTEIN: Do you believe in the divine isolated from the world?

TAGORE: Not isolated. The infinite personality of man comprehends the universe. There cannot be anything that cannot be subsumed by the human personality, and this proves that the truth of the universe is human truth.

EINSTEIN: There are two different conceptions about the nature of the universe — the world as a unity dependent on humanity, and the world as reality independent of the human factor.

TAGORE: When our universe is in harmony with man, the eternal, we know it as truth, we feel it as beauty.

EINSTEIN: This is a purely human conception of the universe.

TAGORE: The world is a human world — the scientific view of it is also that of the scientific man. Therefore, the world apart from us does not exist; it is a relative world, depending for its reality upon our consciousness. There is some standard of reason and enjoyment which gives it truth, the standard of the eternal man whose experiences are made possible through our experiences.

EINSTEIN: This is a realization of the human entity.

TAGORE: Yes, one eternal entity. We have to realize it through our emotions and activities. We realize the supreme man, who has no individual limitations, through our limitations. Science is concerned with that which is not confined to individuals; it is the impersonal human world of truths. Religion realizes these truths and links them up with our deeper needs. Our individual consciousness of truth gains universal significance. Religion applies values to truth, and we know truth as good through our own harmony with it.

EINSTEIN: Truth, then, or beauty, is not independent of man?

TAGORE: No, I do not say so.

EINSTEIN: If there were no human beings any more, the Apollo Belvedere no longer would be beautiful?

TAGORE: No!

A self-portrait by Rabindranath Tagore.

EINSTEIN: I agree with this conception of beauty, but not with regard to truth.

TAGORE: Why not? Truth is realized through men.

EINSTEIN: I cannot prove my conception is right, but that is my religion.

TAGORE: Beauty is in the ideal of perfect harmony, which is in the universal being; truth is the perfect comprehension of the universal mind. We individuals approach it through our own mistakes and blunders, through our accumulated experience, through our illumined consciousness. How otherwise can we know truth?

EINSTEIN: I cannot prove, but I believe in the Pythagorean argument, that the truth is independent of human beings. It is the problem of the logic of continuity.

TAGORE: Truth, which is one with the universal being, must be essentially human; otherwise, whatever we individuals realize as true, never can be called truth. At least, the truth which is described as scientific and which only can be reached through the process of logic—in other words, by an organ of thought which is human. According to the Indian philosophy there is Brahman, the absolute truth, which cannot be conceived by the isolation of the individual mind or described by words, but can be realized only by merging the individual in its infinity. But such a truth cannot belong to science. The nature of truth which we are discussing is an appearance; that is to say, what appears to be true to the human mind, and therefore is human, and may be called maya, or illusion.

EINSTEIN: It is no illusion of the individual, but of the species.

TAGORE: The species also belongs to a unity, to humanity. Therefore the entire human mind realizes truth; the Indian and the European mind meet in a common realization.

A portrait of Albert Einstein by post-impressionist painter Leonid Pasternak. 1924.

EINSTEIN: The word species is used in German for all human beings; as a matter of fact, even the apes and the frogs would belong to it. The problem is whether truth is independent of our consciousness.

TAGORE: What we call truth lies in the rational harmony between the subjective and objective aspects of reality, both of which belong to the superpersonal man.

EINSTEIN: We do things with our mind, even in our everyday life, for which we are not responsible. The mind acknowledges realities outside of it, independent of it. For instance, nobody may be in this house, yet that table remains where it is.

TAGORE: Yes, it remains outside the individual mind, but not the universal mind. The table is that which is perceptible by some kind of consciousness we possess.

EINSTEIN: If nobody were in the house the table would exist all the same, but this is already illegitimate from your point of view, because we cannot explain what it means, that the table is there, independently of us. Our natural point of view in regard to the existence of truth apart from humanity cannot be explained or proved, but it is a belief which nobody can lack—not even primitive beings. We attribute to truth a superhuman objectivity. It is indispensable for us—this reality which is independent of our existence and our experience and our mind—though we cannot say what it means.

TAGORE: In any case, if there be any truth absolutely unrelated to humanity, then for us it is absolutely non-existing.

EINSTEIN: Then I am more religious than you are!

TAGORE: My religion is in the reconciliation of the superpersonal man, the universal spirit, in my own individual being.

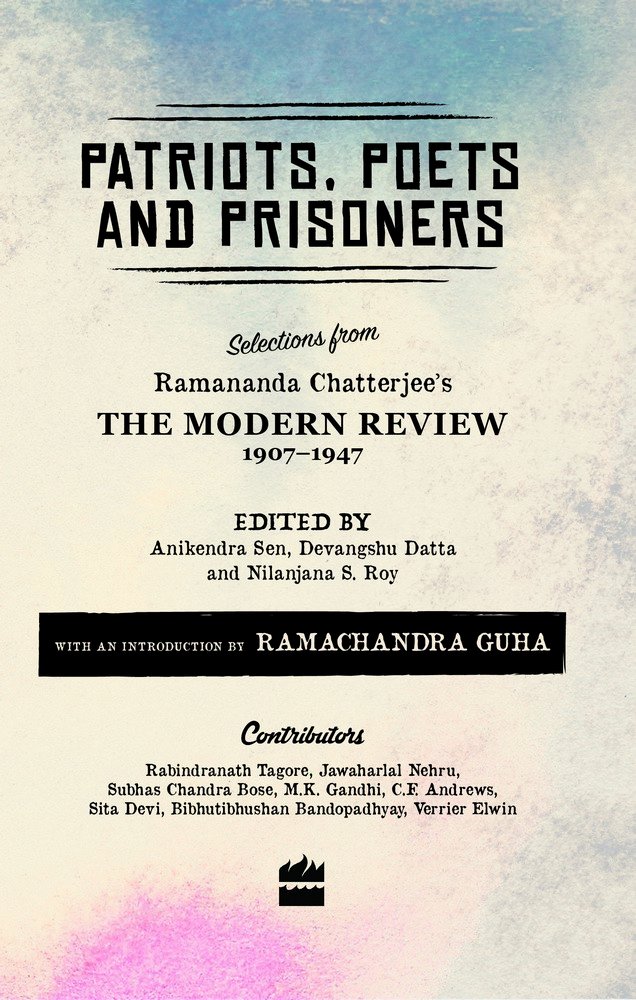

The Modern Review was founded in 1907 by Ramananda Chatterjee, who also founded and edited the Bengali magazine, Prabasi and the Hindi magazine, Vishal Bharat. All three periodicals can be best described as journals of opinion.

The Modern Review published essays by practically every well-known leader of the Indian nationalist movement, along with the views of foreign sympathisers. It also carried rousing editorials from Ramananda Babu himself. After his demise in 1943, his son Kedarnath carried on the good work until he passed away in 1965. The magazine also published fiction, book and art reviews, travelogues, etc., including essays by pioneers like the anthropologist Verrier Elwin and historian, Jadunath Sarkar.

Ramananda Babu allowed his contributors to present every shade of opinion and argue their cases, while ensuring the magazine itself maintained an impartial editorial stance. He was happy to publish long multi-issue arguments between luminaries like Tagore-Gandhi and Subhas Bose-Sardar Patel about the shape and direction of the nationalist movement. Contemporary opinions about topics such as education, women’s rights, the relations between religions and castes, electoral politics, India’s place in the world, and international relations can be accessed and contextualised by leafing through the archives of this journal of record.

—Devangshu Datta

To read a select anthology of articles, interviews, poetry and fiction published from 1907-1947 in the Modern Review, you can buy‘Patriots, Poets and Prisoners’ here.

Albert Einstein was a German-born physicist who developed the general and special theories of relativity and won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1921 for his explanation of the photoelectric effect. He is arguably the most influential scientist of the 20th century but, besides the more than 300 scientific papers Einstein wrote, he also wrote more than 150 non-scientific works that established him as one of the leading thinkers of his era. His intellectual proficiency and original thinking have made the word ‘Einstein’ synonymous with ‘genius’. You can read more about him and his work here.

Rabindranath Tagore was a polymath who reshaped Indian literature, music and art with contextual modernism in the late 19th and 20th centuries. He was the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913, but he was much more than that. He was an alternative face of modernity that arrived on the horizon just in time: when India and the world had begun to grow weary of modernity’s older face. You can read more about his life and work here.

Devangshu Datta is consulting editor and science and technology correspondent at the Business Standard. He is an editor, along with Nilanjana S. Roy and Anikendra Nath Sen of Patriots, Poets and Prisoners.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1943-1945 | |

|

1943-1945 |

| Origin Of The Azad Hind Fauj | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

I am sorry to say that the conversation and the words provided here are not the right one. After consulting other sources, I am sorry to tell this as the very first line:

TAGORE: You have been busy, hunting down with mathematics, the two ancient entities, time and space, while I have been lecturing in this country on the eternal world of man, the universe of reality.

is not included in the conversation. It is misleading as from the “Religion of Man” and other writings do not suggest this as the starting line of the conversation. Also the third line

TAGORE: Not isolated…. contains further details like this:

I have taken a scientific fact to explain this —

Matter is composed of protons and electrons, with gaps between them; but matter may seem to be solid. Similarly humanity is composed of individuals, yet they have their interconnection of human relationship, which gives living unity to man’s world. The entire universe is linked up with us in a similar manner, it is a human universe. I have pursued this thought through art, literature and the religious consciousness of man.

which is also missing. I think this is not the original one but just an abriged version,