The suspension of law released a spectral force of power that was a gift from heaven for someone like Bansi Lal, the Haryana chief minister and Sanjay’s hatchet man. An ambitious man of action, he was not wont to let the law and official rules of conduct stand in the way when it came to outdoing his master’s bidding. Since June 12, the chief minister had been directing government officers in his state to round up people and send them to Delhi for rallies in support of Indira. On the afternoon of June 25, he asked his principal secretary to tell the police to prepare a list of people “prejudicial to the state.” Around 10 p.m., the principal secretary was summoned to the chief minister’s residence, where he handed over the list. Soon, he was in Bansi Lal’s bedroom. The chief minister was sitting on the bed, reading out names on the list to another minister, who was concurring and also suggesting fresh names. The principal secretary and another senior officer in the bedroom stood as silent spectators.

Bansi Lal already enjoyed authority as a chief minister, but his power grew exponentially on June 25. He had been present that afternoon at a meeting called by Dhawan in his office at the PM’s residence. Om Mehta, the minister of state for Home, and Krishan Chand, the former Indian Civil Service officer whom Sanjay had anointed as Delhi’s lieutenant governor, were in attendance. Also present was K. S. Bajwa, the Delhi SP (Crime Investigation Department) (Special Branch), a thirty- seven-year-old intelligence officer tasked with compiling a list of possible detainees. The discussion concluded with directions to carry out arrests in the night, before the president had even signed the Emergency proclamation.

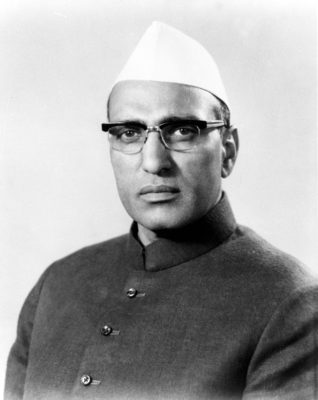

Bansi Lal

While Bansi Lal returned to Haryana to gleefully implement the order, the LG assembled his senior administrative and police officials at his residence late on the evening of June 25. In attendance, among others, was Navin Chawla, the lieutenant governor’s London School of Economics–educated secretary and Sanjay’s friend. Also present was Bhinder, the forty-year-old Sikh police officer who had an uncanny instinct to be present at all such occasions. He was already privy to arrest plans, having been present a day earlier in the discussion of impending arrests with Dhawan and Sanjay at the PM’s residence. LG Krishan Chand opened the meeting by informing the assembled officials that the president was going to declare an Emergency and that they should prepare for arrests. District Magistrate Sushil Kumar protested that there was not enough time to prepare the MISA detention orders and suggested using the ordinary provisions of criminal law instead. But another officer objected to this suggestion, pointing out the absurdity of detaining respected national leaders under criminal law. The LG overruled all objections and directed them to carry out arrests under MISA using the list supplied by the Delhi police officer Bajwa, who was also in attendance. Bajwa then returned to his office, prepared a list of 159 targets for arrest, including 17 top national leaders, and handed it to Bhinder.

DM Kumar had his orders, but issuing so many MISA warrants within a short time was a problem. Dhawan kept phoning him to ask for progress reports. Finally, he went to the PM’s residence to explain the problem to Dhawan. It was to no avail. Left with no option, he assembled his subordinate officers, including ADM Ghosh, handed them the lists supplied by Bajwa, and directed them to make arrests under MISA. The task of typing out individual warrants was so time-consuming that Kumar asked Ghosh to go to the Tees Hazari Court and cyclostyle five hundred copies of blank MISA orders. Ghosh did as directed, but the task took a long time because there was only one machine in working order. Finally, when the job was done, he took the forms to Kumar, who asked him to fill in the names and addresses from Bajwa’s list. Some were left blank to be filled in later with the details of persons arrested. Then Ghosh went to the residence of the SP (South), who organized the raids in his area. The officers conducting the raids were instructed not to investigate the genuineness of charges. The same procedure was followed in other police districts of Delhi.

Writers have described many of these details to highlight the inauguration of the Emergency’s tyranny. I recount them to draw attention to the shadowy power unchained in the darkness before dawn. It was almost lawful but not quite. MISA warrants were used but on cyclostyled forms. Lawful agents of the state conducted the raids and made arrests but the underlying legality of their actions was suspect. Pulling the strings was Sanjay, who occupied no official position but drew his force from the reflected power of Indira. He relied on Indira’s personal assistant and his cronies Dhawan, Bansi Lal, and Om Mehta—all of whom exceeded their official authority. The enforcers were Bajwa, Chawla, and Bhinder. Young and action-oriented, they were dubbed by critics as Sanjay’s crude and ruthless upstarts who had displaced his mother’s suave and talented Kashmiri advisors, willing to ride roughshod over senior leaders and bureaucrats. The suspension of law gave them license to play fast and loose with the rules. Disobeying them ran the risk of retaliation that no one could challenge because the source of their power was shrouded in the enigma of the “PM’s House.”

Delhi’s chief secretary dared to bring to the LG’s notice the questions raised by the law secretary on the legality of grounds for detention in certain cases. LG Chand exploded, saying that it was “legal pettifogging.” When his secretary Chawla heard about the objection raised by the law secretary, his senior by several years and rank, he first chewed him out and then informed him that he had saved him with great difficulty: “I thanked him for the kind turn done to me and saving me from disgraceful exit at the fag end of my career. I left his room a sad man.” Another officer, who arrested only 60 out of the 136 detention requests, found himself transferred. Chawla told ADM Ghosh, a stickler for rules and procedures, that if the grounds for arrest were deficient, “we should fabricate such grounds as might be felt sufficient.” When the magistrate returned several detention orders, Chawla summoned him and threatened both him and his wife, who was also an IAS officer: “The penalty for not cooperating with the Administration in the matter of MISA orders will not be the usual ones like transfer to Andamans, etc. If I know the mind of the present LG, I can say categorically that he will not have the slightest hesitation in putting even senior IAS officers behind the bars under MISA.” Navin Chawla was to deny this later and called ADM Ghosh a liar. But ADM Ghosh, who had been Chawla’s classmate in the IAS, did not want to take chances. He started issuing detention orders as asked by the end of July.

Bajwa generated the list of suspects to be detained and distributed them unsigned to police officers to execute arrests. This was troubling to some in a bureaucracy that was trained to act on written instructions both as a matter of official record and as protection from charges of unlawful conduct. One officer initially took to making a secret note of the detention request to protect himself from possible prosecution later: “Most of us thought that within a day or two the magistracy and the police will be called upon to explain the propriety of these arrests. However, subsequent events belied our apprehension.” As time went on, SP Bajwa began phoning in the list. Some resisted but were pushed back into line. They continued making arrests based on the list furnished by Bajwa, who supplied the grounds some days later. People released on bail by courts were immediately re-arrested.

Second to none in orchestrating and carrying out arrests was Bhinder. On July 11, he wrote to Prakash Singh, SP (North), supplying him with a list of teachers and students at Delhi University who were likely to cause trouble. He urged him to “kindly make arrangements for lifting these teachers and students as early as possible and report compliance.” Bhinder appears to have had a penchant for “lifting.” Thus, on September 25, he lifted Prabir Purkayastha from JNU. In spite of his claim that it was not a case of mistaken identity, and that Prabir had been a target all along, there was no police record on him until after he was abducted. The police field officer assigned to collect information on student activities at JNU had not filed any report mentioning Prabir. But once he was in police custody without a warrant, the paperwork had to be set right to make the unlawful lawful. ADM Ghosh issued a MISA warrant under the direction of his superiors. It was only on September 30, 1975, five days later, that a police report supplied the grounds for the warrant. It claimed that Prabir was a “staunch SFI worker” who had tried to stop students from attending classes, a claim unsupported by the field officer. The report went on to assert that though Prabir had joined JNU only in 1975, so powerful was his political image that Ashoka Lata Jain came under its spell and became romantically involved with him. The report was wrong. Though Prabir joined JNU only in August 1975, he had been spending time on its campus for over a year while conducting computer calculations at the nearby Indian Institute of Technology for his master’s thesis. Unaware of its faulty intelligence, the Delhi police proceeded to invent itself as an expert in matters of the heart. Prabir was a subversive who had beguiled Ashoka with his “political image” within a month of his arrival in JNU.

Four Parliament members wrote to Home Minister Brahmananda Reddy, pointing out that JNU teachers had condemned Prabir’s abduction and requested that he examine the propriety of the police action. Reddy, whom Om Mehta, his junior minister and Sanjay’s pawn, had upstaged, ordered an inquiry. To clear discrepancies, the Home Ministry asked for a report from the Intelligence Bureau, which stated that it had no information to indicate Prabir’s active role in organizing the student boycott of classes. But the Delhi administration closed ranks and flatly asserted otherwise. Prabir’s mother, Mrs. S. Purkayastha, submitted a parole application for her son to the chief secretary of the Delhi administration on November 5, 1975. On November 24, Dr. N. M. Ghatate filed a habeas corpus writ petition under Article 226 on Prabir’s behalf in Delhi High Court. While this was pending, he also filed a parole petition for him to appear in his viva voce examination in Allahabad to complete his master’s degree from Motilal College of Engineering. On December 1, three senior JNU faculty members submitted a petition for Prabir’s release, with supporting affidavits from students who had witnessed the police abduction.

In preparing the legal brief against these petitions, the Delhi administration asked the concerned officers for their opinion. ADM Ghosh recommended parole, but SP Bajwa did not. The police officers closed ranks. No, it was not a case of mistaken identity. The police did not grab Prabir and whisk him off and produce a warrant post facto late that night. Contrary to all documentary records, the SP (South) claimed that a police inspector accompanied by two subinspectors entered the JNU compound in a vehicle and executed a pending MISA warrant at 9:30 a.m. in an orderly fashion. Even Ghosh concurred in the cover-up. Bhinder read the petitions on Prabir’s behalf and recommended no response, as the matter was sub-judice. But everyone lied to protect Bhinder. Even Maneka Gandhi came to his defense. She stated that Prabir was one of the students who stopped her and claimed that she did not go home immediately but sat in the lawns. It was then that some officers in plainclothes came and arrested Prabir. No, there was no Sikh gentleman among them. The logbook of the car contradicted her account.

Meanwhile, the police finally netted Devi Prasad Tripathi, DIG Bhinder’s original target. Along with two friends, Tripathi was walking from Old Campus to New Campus when a posse of policemen grabbed him, dumped him in a waiting van, and spirited him away. A month later, Sitaram Yechury, another JNU SFI leader, also found himself behind bars. These successes did not make the Delhi police go easy on Prabir. When the Delhi High Court ordered his release on parole, the Delhi administration wanted to appeal. But the Supreme Court was closed for winter vacation and would not reopen until January 4. Left with no path of resistance to the court order for parole, the Delhi administration nevertheless defied it by not releasing him and transferred him in handcuffs to Naini Jail in Uttar Pradesh near Allahabad on January 1, 1976. He appeared for his viva voce examination in the prison. Three days later, he was brought back to Tihar Jail in Delhi. His distraught parents ran from pillar to post to obtain his release. Using her Bengali connections, his mother contacted D. P. Chattopadhyaya, a minister in Indira’s government, for help. He wrote to Om Mehta in February 1976, prompting further inquiry by Home Ministry officials. Asked to reexamine the case and revoke Prabir’s detention, the Delhi administration cited Bajwa’s questionable evidence as the truth to rebuff the request. On March 3, Prabir was transferred to Agra Jail, where he spent the remaining days of his imprisonment. The news of his solitary confinement for twenty-five days caused his mother to have a nervous breakdown. There appeared to be no way to get her son released, no way to move, let alone hold accountable, the mysterious power birthed by the suspension of constitutional rights.

Beginning on June 29, the government introduced a series of presidential ordinances to amend MISA that extracted further life out of the rule of law. These ordinances forbade the courts from applying the concept of “natural justice” in cases involving MISA detainees, rendered inapplicable the provisions for the communication of grounds for arrest, and prevented advisory boards from reviewing detentions. No one, including a foreigner, could challenge detention on grounds of natural or common law; and grounds for detention were defined as confidential matters of the state and their disclosure, including to the detainee, against the public interest. This made preventive detention far more draconian and placed it beyond even the quasi-judicial scrutiny of advisory boards. It is worth recalling that critics in the Constituent Assembly had warned against the abolition of due process, fearing that it would lead to executive overreach. A much milder Preventive Detention Bill moved by Patel in 1950 had also provoked objections. The central government went on to immediately use the law. Over the years, various state governments also used versions of preventive detention laws. When MISA was first introduced in 1971 in the wake of the Bangladesh war, the government had stated, in the face of vociferous criticism, that it would not be used against internal dissent. It did not keep its promise. The MISA amendments tightened the screw further.

However, the amended MISA law, draconian as it was, did not permit the state to conduct arrests without recording the grounds for incarceration, even if they were not to be communicated to the detainee. But, as we have seen in Bajwa’s practice of communicating lists of persons to be arrested, often on the telephone, the police routinely violated the law. This was true not just in Delhi but everywhere. The required four-month review of individual cases also remained on paper. The government was callous in responding to requests for parole because of death or illness in the family, or to appear for examinations, as in Prabir’s case. Secretary Chawla warned an official against noting recommendations for parole on the file. It was “friendly advice,” he added.

Licensed to arrest on the flimsiest of grounds, the police detained over 110,000 people under MISA and Defence of Internal Security of India Rules. Many of them were members of banned organizations like the RSS, Anand Marg, Jamaat-e-Islami, and the Maoist CPI(ML), as well as non-CPI opposition parties. Mere membership in the banned organizations or alleged sympathy for them, not any documented prejudicial activity, was grounds for arrest. Alleged participation in secret meetings, criticism of the Emergency or the prime minister in the public arena or private conversations, and opposition to government policies were grounds for detention. A large number of suspected criminals in several states were also put behind bars under MISA. In several cases, their alleged offenses were committed more than five years before 1975. Several trade union activists were rounded up on the grounds that they previously participated in agitations against the management. New Delhi advised state governments against the indiscriminate use of MISA, but it could not control what it had unleashed. The Shah Commission, appointed in 1977 to investigate the Emergency’s “excesses,” concluded: “MISA was used as a weapon against all kinds of activities, not even remotely connected with the security of the state, public order or maintenance of essential supplies.”

There are many examples, including Prabir’s, that substantiate Justice Shah’s conclusion. A notable example was the arrest of Primila Lewis. On July 2, Lewis arrived in Delhi along with her eight-year-old son, Karoki, on a flight from London. At the airport, the immigration officer examined her passport and read out her name with a tone of recognition. Soon, she and Karoki were whisked off to the International Departure Lounge. A long wait followed while Primila tried to reassure her tired and anxious son. Around 12:30 p.m., a posse of police officers entered the lounge and escorted the two into a waiting taxi, which took them to the Parliament Street Police Station. Another long wait followed. Primila knew the Emergency had let loose random arrests. But knowing what could now happen, with a child restless after a long international flight, heightened her anxiety. Around 5 p.m., she was served with a warrant of arrest under MISA. Her crime? She had ruffled some powerful feathers.

Primila, who was then thirty-five years old, had earned a master’s degree from Mount Holyoke College in the United States and taught English literature first at Indraprastha College for Women in Delhi and later at University College, Nairobi. After five years in Nairobi, she returned to India along with her English husband, Charles Lewis. She lived for a year in Bombay, where she became involved in working with those living in poor neighborhoods. The family moved in 1971 when Charles was posted to Delhi. Wishing to live simply, she chose to rent a farmhouse in Mehrauli, on Delhi’s outskirts. The area retained the flavor of the village that it had originally been, except now it sported the farmhouses of the Delhi gentry.

The elite list of farmhouse owners included Indira and her cousin B. K. Nehru, retired generals, prominent industrialists, former royalty, and senior civil servants, whose farmhands were mostly Dalit immigrants from northern and eastern India. Their children became Karoki’s playmates. This is how Primila became involved in their lives. One thing led to another, and she was soon organizing the farmhands. She formed a union that fought against unjust evictions and pressed for the implementation of the minimum wage law. The union scored one success after another, but it also brought Primila in the crosshairs of Navin Chawla, then the ADM of the area, who was soon to become a powerful force in the Delhi administration. The press was beginning to pick up the story of how the rich and powerful were flouting the law on minimum wages. Indira heard the complaints of the incensed elite and chastised LG Chand, who turned up the heat on Chawla. By 1975, Chawla was no longer the ADM of the area but was now the secretary to LG Chand and the power behind the throne. So, when Primila stepped off that plane on July 2, the immigration staff was briefed and the police were ready. She would spend the next eighteen months in prison and was released on parole on January 9, 1977.

As Primila’s swift dumping from an international flight to the prison shows, shadow power was capricious and unrestrained, and it could be brutal. Among the many who suffered was Lawrence Fernandes. The police picked up Lawrence from his home in Bangalore on May 1, 1976. They immediately began torturing him to extract information on the whereabouts of his brother George Fernandes, the Socialist leader who had gone underground. Lawrence knew nothing. Unconvinced, the police continued to interrogate and torture him for days. When his physical condition became grave and the police feared his death in custody, they summoned a doctor. He was not told Lawrence’s identity. With the patient obviously appearing physically abused, the doctor advised immediate admission into a hospital, but he was not taken to a hospital. The police had not even formally recorded Lawrence’s arrest. They fabricated the date of his arrest as May 10, nine days after the actual date, on the false charge of involvement in sabotaging railway tracks with bombs. Later, he was transferred to the Bangalore Central Prison in a broken physical condition. Initially housed with condemned prisoners, he was placed after protest with other MISA detainees. When he was released toward the end of the Emergency, the physical toll of torture and ill treatment was still visible on his body.

Lawrence was seized and tortured because he happened to be the brother of George Fernandes, who had led the crippling 1974 railway strike and was conducting an underground resistance. Lawrence’s misfortune was that he was the elusive George’s brother, but there were others who suffered brutal treatment without association to famous opposition leaders. A case in point is Jasbir Singh, a JNU student and an opposition party activist. The police arrested him and planted some posters and Naxalite pamphlets in his bag. They tied his hands and feet to a pole, which was suspended between two chairs that were dragged apart to make Jasbir swing in the middle. He vomited blood. When he complained, the inspector threatened to kill him and discard his body in the river. Dutifully following the law, the police produced him before a magistrate. Jasbir complained, but the magistrate paid no heed, and the torture became worse.

With no public knowledge and scrutiny allowed, the authorities were able to act without restraint. Jasbir, Prabir, Primila, and countless others were left with no recourse. This was not, however, the first time in India’s history that the police were able to act with impunity. As early as 1902, the Fraser Commission had identified corruption, brutality, and inadequate supervision of the constabulary at the local level as problems. Its recommendations for reforms remained on paper, however. The problem was structural. The British colonial rule established a modern state external to society. The population experienced the arms of the civilian administration and the police as alien forces with coercive command over them. The independent Indian government inherited this coercive structure and its laws but saw no need for a fundamental structural change in how the administrative state functioned.

Several committees in the postcolonial era made recommendations for reforms, but the government did not implement them. The poorly paid and trained police continued to govern the population with habitual arbitrariness and impunity. In 1977 the Shah Commission pointed to widespread police misconduct and suggested reforms, once again. The National Police Commission, established in November 1977 by Morarji Desai’s Janata government, studied policing comprehensively. Its report showed conclusively that the post-Independence monopoly of power by the Congress party produced a pattern of political interference in police work. The interaction between politicians and the administration for implementing government policies degenerated into daily intercession for political advantage. During elections, the police would look the other way as politicians employed criminal elements to intimidate voters. Politicians secured police compliance by wielding the threat of transfer. Under political pressure, the police routinely flouted norms and rules. In the absence of a concerted effort to cultivate a democratic culture, police misconduct at the behest of the socially and politically powerful was endemic.

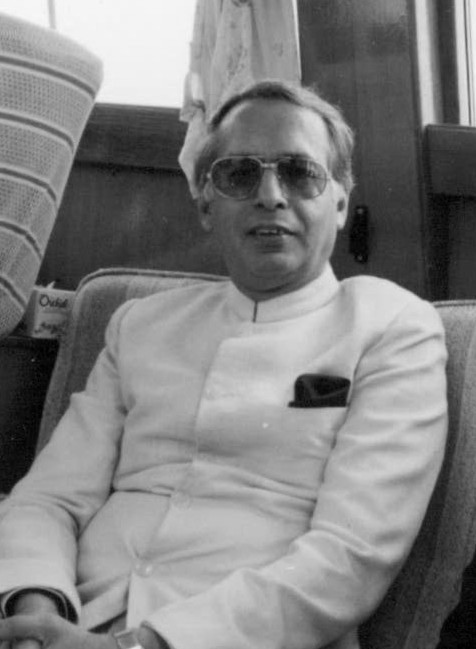

V. C. Shukla

The imposition of press censorship ensured that there was no public knowledge or discussion of police atrocities. Western newspapers, which had universally condemned the imposition of the Emergency, were warned to follow the censorship rules. Sanjay saw to it that his mother booted out Information and Broadcasting Minister I. K. Gujral, who was seen as insufficiently enthusiastic of the new dispensation. Gujral’s replacement was V. C. Shukla, a Sanjay loyalist, who summoned foreign correspondents on June 29 and, “breathing fire and smoke,” warned them they risked expulsion if they defied the censor. On June 30, the government expelled Lewis M. Simons, the Washington Post correspondent. He was given twenty-four hours to leave. Apparently this was in retaliation for his dispatch of June 20 mentioning that the defense minister had asked the army chief to send soldiers in plainclothes for a rally in support of the prime-minister and that the order was withdrawn when the news leaked. Peter Gill of the Daily Telegraph and Peter Hazelhurst of The Times were expelled on July 22 for refusing to pledge that they would comply with the censorship guidelines, and the BBC withdrew Mark Tully rather than have him sign a written undertaking. Kevin Rafferty of the Financial Times was accused of acting as a courier for other foreign journalists and was refused entry. Martin Woollacott of the Guardian, who was then outside India, was told that he would not be admitted unless he signed the pledge.

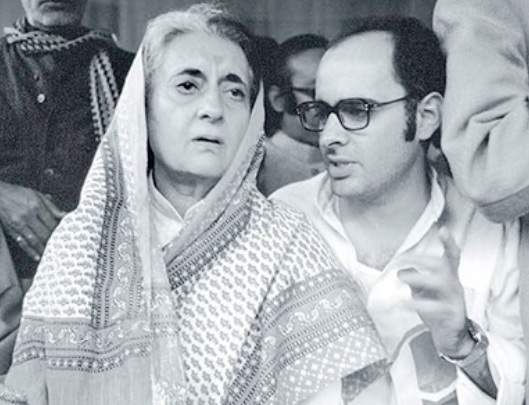

Indira and Sanjay Gandhi

The Western press posed a nuisance with editorial denunciations of the Emergency and press censorship and criticism of Indira from afar. Protest statements and letters from old India hands and intellectuals in the United States and Britain, including her long-time American friend Dorothy Norman, rankled Indira. But irritating and disappointing as these were, she remained defiant. In any case, far more important was the job of taming the Indian press. Having given them a taste of its intentions by cutting off electricity on the night of June 25, the government warned that publishing blank editorials, as the Hindustan Times and Indian Express had done, would not be tolerated. K. R. Malkani, the editor of the RSS daily, the Motherland, which had published sensational stories on Indira and Sanjay, was arrested early on the morning of June 26. A month later, the police arrested the senior journalist Kuldip Nayar. He drew official ire because of his work for the Indian Express, a newspaper sympathetic to JP. The government did not spare his eighty-one-year-old father-in-law, Bhim Sen Sachar. A life-long congressman, he had served twice as the Punjab chief minister and several terms as governor of different provinces. But none of this mattered. The police arrested him for his audacity in writing to the prime minister and demanding the removal of press censorship and the restoration of freedom.

To tame the press, the government circulated detailed censorship guidelines on June 26 under the Defence of India Rules that prohibited any publication of news about the Emergency and actions under MISA without the scrutiny of the censor’s officer. In February 1976, it enacted the Prevention of Publication of Objectionable Matter Act against the printing of “incitement of crime and other objectionable matter.” In addition, daily censorship orders were communicated over the phone to newspapers to prevent the publication of anything considered against or embarrassing to the regime. Navajivan Press, established by Mahatma Gandhi, saw its printing facilities confiscated. Himmat, a weekly edited by Rajmohan Gandhi, the Mahatma’s grandson, was suddenly asked to make a substantial deposit because it published allegedly objectionable reports. Romesh Thapar, who was once Indira’s confidant but had turned a critic by 1974, miraculously continued to publish Seminar until July 1976. Perhaps the ax did not fall on the journal because of its limited subscription and because of Thapar’s previous association with Indira. Seminar published an issue called “Judgments” in December 1975. It contained articles on the laws of detention, writ petitions, the prime minister’s election case, and a statement by Palkhivala on constitutional amendments. As was the journal’s practice, the articles were not overtly political but there was no mistaking the political implications of the interpretations of the laws. There was nothing covert about the politics of its July 1976 issue devoted to “Where do we go from here.” It included an article by political scientist Rajni Kothari on restoring the political process and one by the writer Nirmal Verma on the importance of freedom. That was it. The ax fell, and Seminar ceased publication rather than submit the journal to pre-censorship. The Indian Express and the Statesman also encountered punitive measures from the government for showing signs of resistance.

All these measures had the desired effect. The newspapers complied and published official press releases, statements, and speeches by Indira and her minions. Political cartoons disappeared overnight. The dailies dutifully reported on Indira’s faux socialism, the highlight of which was her vaunted twenty-point program to remove poverty, abolish bonded labor, implement laws on land ceilings, advance social equality, and improve the economy. To this, Sanjay added his five-point program on birth control, slum rehabilitation, and beautification. With the party apparatus destroyed and the administration in a state of paralysis, there was no way to implement even the long-desired and uncontroversial social objectives. The only instrument at the regime’s command was its coercive power, which Sanjay and his lackeys deployed with abandon, as we will see later.

As information and broadcasting minister and Sanjay’s foot soldier, Shukla missed no opportunity to enforce compliance and mount propaganda. One that fell into his lap was a triptych presented to the prime minister in June 1975 by the famous artist M. F. Husain. Later hounded into exile by right-wing Hindu activists, Husain called his work “The Triptych in the Life of a Nation.” It was his response to the political crisis, though it was widely used and seen as an endorsement of the Emergency.

The first, titled Twelfth June ’75 shows the figure of Janaki, the daughter of Earth, set high above in the sky and beyond the reach of the accusing fingers from the menacing headless body below named Janata. The second, titled Twenty fourth June ’75, depicted Mother Earth in turmoil, her hair scattered over the Himalayas, her knees pulled up toward the Bay of Bengal, her breasts drowned in the Indian Ocean, and her gaze fixed on the scales of justice titled “Supreme.” The third, and the most controversial, called Twenty sixth June ’75, was an image of Goddess Durga riding a roaring tiger, determined to eliminate evil.

The Information and Broadcasting Ministry arranged for the exhibition of the triptych in Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta, New York, and Prague. Reporting on the response, the ministry noted that it was favorable, though in Prague some young and old Czechoslovak artists were reportedly startled by the triptych’s “high degree of sex symbolism.” They were assured that the work was not pornographic but modern interpretations of India’s traditional mythology. Perhaps drawing from Husain’s note describing his motivations for the triptych, the ministry’s secretary enthusiastically compared the paintings to Picasso’s Guernica and asked the director of the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi to house them permanently in the museum. The director refused, calling the comparison to Picasso an insult to the great master. Thwarted, the ministry directed that the paintings be returned to Husain’s son, although they were gifts to the prime minister. So tainted was the triptych by its association with the Emergency, it is no longer in public circulation.

Kishore Kumar

Another instance in which the ministry’s propaganda efforts failed spectacularly, though not for want of trying, involved the famous film actor and playback singer Kishore Kumar. Ministry officials traveled to Bombay and summoned him to a meeting to discuss their proposal that he compose and sing songs lauding the twenty-point program. The mercurial singer came on the phone and “curtly and bluntly” declined to meet them, pleading illness, and adding that he did not sing on the radio and TV. Used to compliance, the mandarins from the ministry were enraged by his defiance. They ordered a ban on his recorded songs being played on All India Radio and government-controlled television and unsuccessfully tried to get the record companies to withdraw his records.

When Kishore Kumar’s songs stopped playing on All India Radio, his fans did not know the reason for it. They could guess and speculate, but the real cause remained hidden from them. This was the general condition under strict censorship. It was not a matter of abstract freedom, affecting editors and reporters, and the singer’s fans alone. The news blackout, the absence of public knowledge and accountability, could devastate lives. This is what happened to P. Rajan, an engineering student in Kerala, and his father, Professor T. V. Echara Varier.

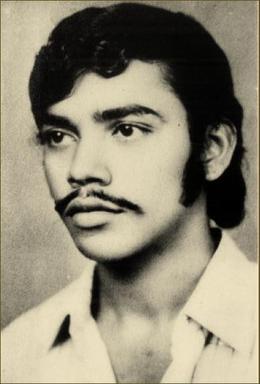

P. Rajan

On February 29, 1976, the police arrested twenty-one-year-old Rajan along with another student from their dormitory at the Regional Engineering College in Calicut. Suspected of being Naxalite sympathizers, they were taken to a nearby police camp and tortured. Rajan’s father, a professor of Hindi, learned of his son’s arrest the following day and immediately went to the police camp. Although Varier was denied entry, the sentry at the gate confirmed that his son was being held inside. This camp was one of several torture chambers, called “workshops” in police parlance, in operation in the state. Among the torture methods they employed was one called the “ruler treatment,” or “rolling.” It involved placing the victim on his back on a bench with his head dangling off one end. The victim’s mouth would then be stuffed with his undergarments to muffle the sound of his cries of pain. A heavy wooden ruler would be placed on his legs and two policemen sitting on either end would roll it up the thighs of the victim. The pain would be excruciating, and the torture would tear the ligaments from the bone, which often cracked under pressure.

From the time he was turned away from the dreaded police camp, Professor Varier’s life, as he relates in his moving Memories of a Father, was consumed by the effort to find his missing son. He tried to move heaven and earth to get information, meeting the CPI leader and Kerala chief minister Achutha Menon and the home minister, petitioning Members of Parliament, and writing to newspapers. But no one was able or willing to provide any information on the whereabouts of his son. Acquaintances shunned him, afraid of associating with the father of a son accused of subversion. He suffered unspeakably, but the experience did not break him. The determined father pressed on, fortified by the memory of and love for his son. When the Emergency was lifted, he filed a habeas corpus petition before the Kerala High Court. The police denied that they had ever had Rajan in custody, but the evidence proved that they had arrested and taken him to the police camp, where he was tortured. The DIG (Crime Branch) was later convicted, but the conviction was overturned on appeal. Rajan’s body was never found. Apparently the police disposed of his body after torturing him. Professor Varier died in 2006, still grieving for the son whose body he never found:

My son is standing outside drenched in the rain.

I still have no answer to the question whether or not I feel vengeance.

But I leave one question to the world:

why are you making my innocent child stand in the rain even after his death.

I don’t close the door.

Let the rain lash inside and drench me.

Let my invisible son at least know that his father never shut the door.

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of Gyan Prakash and Penguin Random House India. You can buy Emergency Chronicles: Indira Gandhi and Democracy’s Turning Point here.

Gyan Prakash is the Dayton-Stockton professor of history at Princeton University. He specializes in the history of modern India. He was a member of the influential Subaltern Studies Collective until its dissolution in 2008, and has been a recipient of the Guggenheim and the National Endowment of Humanities fellowships. He is the author of several books, including Another Reason: Science and the Imagination of Modern India (1999), the widely acclaimed Mumbai Fables (2010), which was adapted for the film Bombay Velvet (2015), for which he wrote the story and co-wrote the screenplay, and Emergency Chronicles: Indira Gandhi and Democracy’s Turning Point (2018). He lives in Princeton, New Jersey. You can read more about him and his work here.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1100–1199 CE | |

|

1100–1199 CE |

| Topography as History: Reading Kashmir through Rajatarangini | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1828-1843 | |

|

1828-1843 |

| Scandal of Manners: ‘Urinating Standing Up’ | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1910-1950 | |

|

1910-1950 |

| Forging Unity: Vallabhbhai Patel and the Politics of Nationalism | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Patriarchal Lechery | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1943-1945 | |

|

1943-1945 |

| Origin Of The Azad Hind Fauj | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1950-1951 | |

|

1950-1951 |

| Panikkar’s 1950 Ordeal: China’s Moves, Family Crisis, and Diplomatic Distrust | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply