ARCHIVE

Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders

The paths

are many

The Destination

is one

Do you not see?

There are many paths

to the Ka’ba.

– Mevlana Jalaluddin Rumi

I am standing in the courtyard of Dewa Sharif, in Uttar Pradesh, surrounded by a sea of yellow as I wait for the urs ceremony to start. A first-time visitor may not know that the Warsis of Dewa Sharif wear this distinctive shade of yellow or about its significance.

Haji Syed Waris Ali Shah (1817-1905), the founder of this silsilah, not only wore yellow in his daily life, he also performed his hajj in an abram (unstitched robe worn by pilgrims) of the same colour. Was it because yellow symbolizes paleness? The lover is pale and anguished, longing for his Beloved Divine, and he suffers till he becomes ‘golden’, like metal, in the crucible of love.

Is yellow associated with Sufism? Or do followers of a certain saint wear it? To understand this one must understand what a silsilah or Sufi order is.

The Sufi

When the uninitiated think of Sufism in India, it is the very popular dargahs of Khwaja Garib Nawaz and Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya that come to mind. Most people probably don’t know that they belong to the Chishti silsilah, or indeed what silsilahs are, and how they helped in the spread of Sufism.

The Arabic word ‘silsilah’ literally means chain, and in Sufism it refers to the formal chain of spiritual descent. The chain runs across centuries but starts with the master who passes on their mystic wisdom to disciples, who in turn pass it on to theirs and so on.

The Arabic word ‘silsilah’ literally means chain, and in Sufism it refers to the formal chain of spiritual descent. The chain runs across centuries but starts with the master who passes on their mystic wisdom to disciples, who in turn pass it on to theirs and so on.

In the previous chapter, we have seen how the first Sufis came to the Indian subcontinent in the eighth and ninth centuries. But it was only with the establishment of the Sufi silsilahs (orders) in the twelfth century that Sufism became popular. Many graves of pir babas (saints) from the early period are revered even today. They are scattered across various parts of the subcontinent. Although they often have a strong localized following, not much is known about them.

For instance, Haji Rozbih, the first Sufi saint to reach Delhi, lies buried just outside the walls of the Chauhan Fort, Lal Kot, Mehrauli in Delhi. Next to his simple open air grave in the forest is the grave of another devotee, said to be his female disciple from the Chauhan clan and a daughter of Prithviraj Chauhan. This claim maybe far-fetched, especially because Prithviraj Chauhan never came to Delhi. Besides, we don’t know enough about the saint, so we can’t be certain he had disciples at all. Chishti saint Qutub Sahib, too, is in Mehrauli; he holds sway over the hearts of not just the locals but people the world over. In his case, because the Chishti silsilah is well documented, we know of his history and karamat and disciples.

With the consolidation of the Delhi Sultanate came the establishment of khanqahs (Sufi hospices), and state patronage of saints, with the new conducive atmosphere, the Sufi orders were able to establish themselves firmly in the Indian subcontinent. The urs (death anniversary) celebrations of Sufis slowly began to attract thousands from across the globe, and it continues to do so even now. The most popular urs ceremony in India is that of the Chishti saint of Ajmer, Khwaja Muinuddin Chishti, known popularly as Khwaja Garib Nawaz.

In this and the subsequent chapters, I delve into the formation of silsilahs, as their emergence is very important to understand Sufism.

From the tenth century onwards we see the popularity of Sufism spread across Central Asia. The establishment of the Delhi Sultanate (1192) coincided with unrest in Central Asia due to the Mongol invasions, leading to the large scale exodus of immigrants into India. Many Sufi saints, too, thus arrived in India during this period and set up their khanqahs.

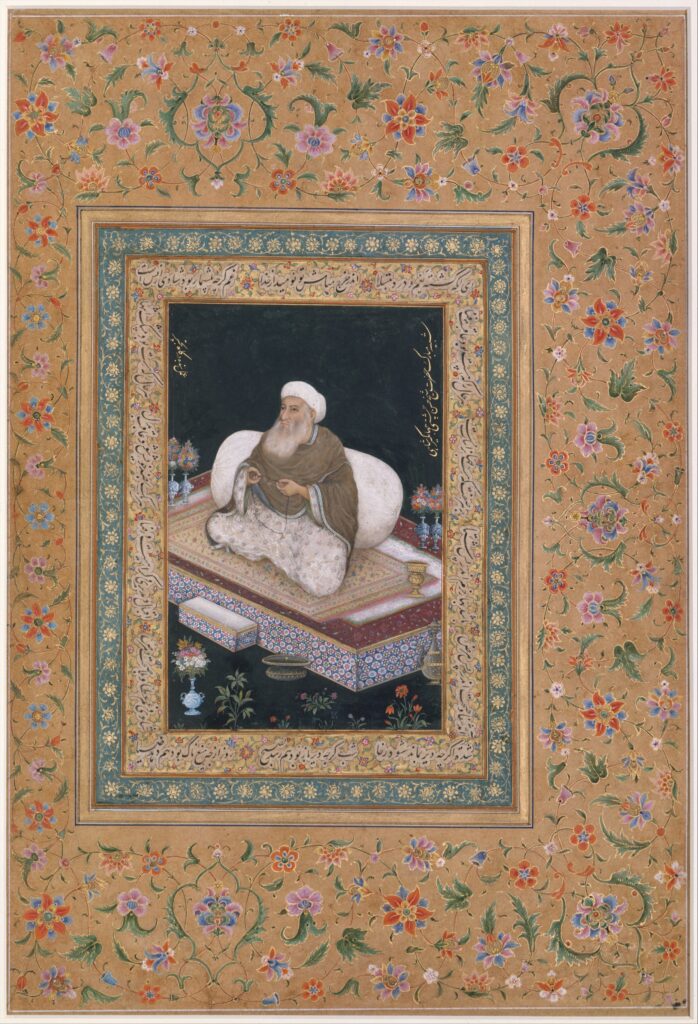

“Portrait of Shaikh Mu’in al-Din Hasan Chishti”, Folio from the Shah Jahan Album

This led to the emergence of many new traditions and according to Raziuddin Aquil, an academic, the ‘interactions between various strands of Islam and diverse Indic religious traditions led to the emergence of new forms of religiosity, cults and sects, the most prominent being Sufism, Bhakti and Sikhism’. Aquil then proceeds to elaborate on this succinctly:

“Sufis were able to evolve an acceptable language and common grounds, which the self-styled guardians of Islam, the ulama, could not. Low-caste Bhakti saints could speak against social inequities, the Brahmin pandits could not. Some of the exalted gurus did speak of social harmony, but their ill-trained chelas [disciples] did not. For some, bigotry was the guiding principle of life; for others, justice and humanity were the ideals to adhere to.”

“Sufis were able to evolve an acceptable language and common grounds, which the self-styled guardians of Islam, the ulama, could not. Low-caste Bhakti saints could speak against social inequities, the Brahmin pandits could not. Some of the exalted gurus did speak of social harmony, but their ill-trained chelas [disciples] did not. For some, bigotry was the guiding principle of life; for others, justice and humanity were the ideals to adhere to.”

Raziuddin Aquil

As the number of Sufis began to increase, they began to feel the need to formalize and legitimize their spiritual training. This led to the rise of mystical orders or silsilahs from the twelfth century. Silsilahs gave the followers a spiritual hierarchy and a place within it, along with ‘greater respectability and a stronger base of defence against the onslaught of the orthodox’.

The earliest stage of the formation of such orders was marked by the presence of ascetic Sufis who renounced worldly pleasures, and lived in constant remembrance of Allah, and in solitude. They were mainly based in the cities of Basra and Kufa in Iraq. This was in adherence to Prophet Muhammad’s example.

A very popular hadith given in Sahih Muslim (no. 1479) describes the time when the second caliph of Islam, Umar ibn al-Khattab, found the Prophet lying on a straw mat with only a handful of barley in the corner of the cell. The imprint of the Prophet’s bare upper body was still on the mat. On seeing the extremely austere life the Holy Prophet was leading, Umar ibn al-Khattab started weeping. When the Prophet asked him why he was crying, he replied that he was saddened by the realization that the Caesars and Khusraus of the world (kings) lived a life of luxury, while the Messenger of God was living in such poverty. The Prophet said that he was satisfied with the prosperity of the hereafter – meaning he didn’t hanker after worldly pleasures, which were temporary.

Aquil summarizes the spread of Sufism, ‘Beginning with the influential mystic circles of Baghdad, Sufi networks were established in lower Iraq, Iberia, Egypt, north-eastern Iran and Central Asia between the ninth and twelfth centuries.’ The rise of silsilahs was a natural progression when Sufi saints became more organized.

To understand Sufism and its impact in India, it is essential to understand the various silsilahs that flourished here and their important saints, for it was these saints who attracted people to their khanqahs in the early stages. The major saints of each order sent their disciples to various parts of the subcontinent to establish their mission. These were called vilayats (spiritual territories). Today the teachings, legacy, and the karamat (miracles) attributed to these disciples draw people seeking their intercession to the shrines.

To understand Sufism and its impact in India, it is essential to understand the various silsilahs that flourished here and their important saints, for it was these saints who attracted people to their khanqahs in the early stages. The major saints of each order sent their disciples to various parts of the subcontinent to establish their mission. These were called vilayats (spiritual territories). Today the teachings, legacy, and the karamat (miracles) attributed to these disciples draw people seeking their intercession to the shrines.

Though there were many female Sufi saints, they did not establish silsilahs which remained a male privilege.

The silsilahs began to develop in the tariqah stage, discussed in the previous chapter. They were built around a particular saint and his teachings, and the rules of khilafat (succession) were formed. The relationship between the pir and murid became very clear.

The initial silsilahs were formed and named after their masters. Take the example of the first group to organize itself as an order, the Qadriya silsilah; it was named after Sheikh Abdul Qadir Jilani. There was also the Muhasibi silsilah named after Abu Abdullah al Harith Ibn Asad al Anazi al Muhasibi (781-857), and the Junaydi Order named after Junaydi Baghdadi (830-910).

As the Sufi silsilahs developed, they split into a number of branches. Today, there are innumerable silsilahs in the world, but I will limit myself to the major Indian silsilahs.

As these silsilahs formalized their teachings, they also imbibed many other regional influences, which they adapted within the Islamic framework. So while Sufism didn’t grow out of these, as its main source is the Quran, and the life of the Prophet, the monastic traditions of Buddhism and Christianity, and the philosophies of the Vedas, the Upanishads, and Neo Platonism were all absorbed into its discourse.

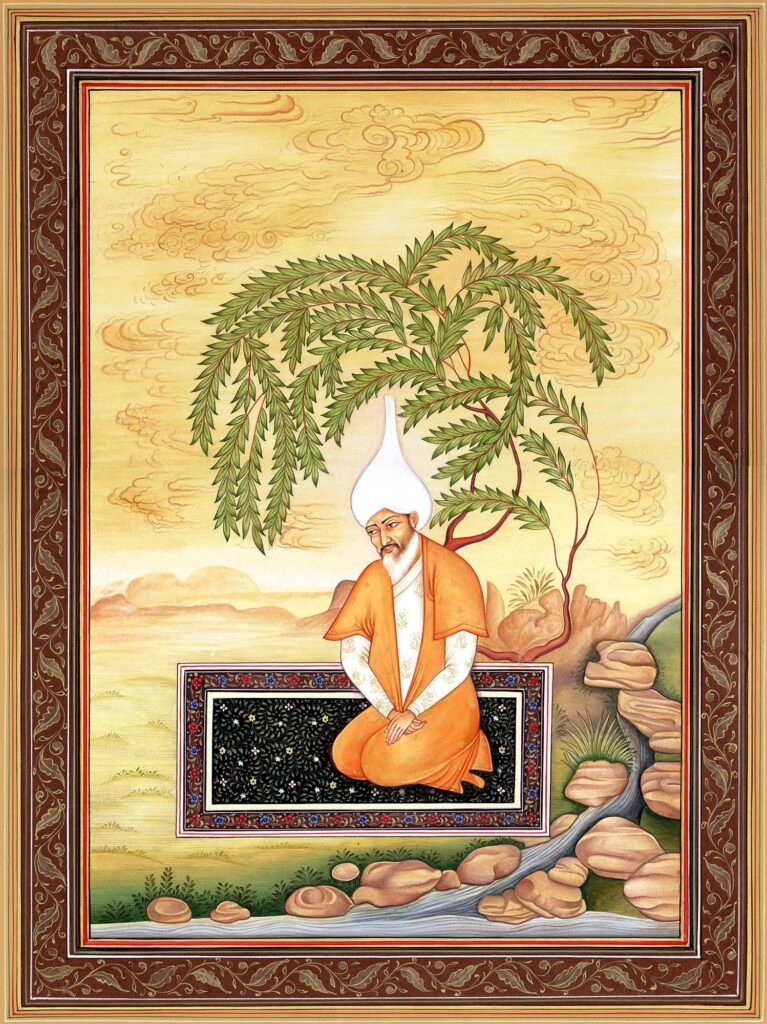

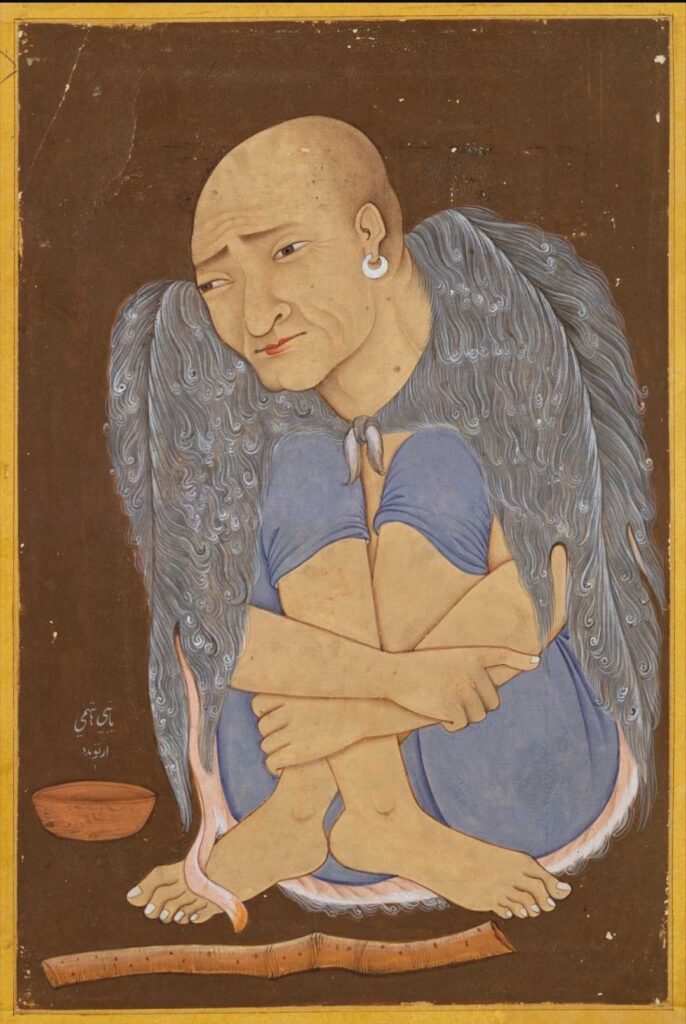

Portrait of a Sufi

Every silsilah had its own particular methods, rituals, and techniques. There is, for instance, a difference in the method of zikr (remembrance of Allah) in each order. While the Naqshbandi order lays emphasis on silent zikr, with breath control and meditation, the Chishti order does it aloud — almost always through the medium of sama mehfils (musical assemblies) to create momentum to lead to a state of trance. The Chishti silsilah today is the main promoter of the tradition of qawwali; you will always find qawwalls being sung in their dargahs. Scholar and author Omar Khalidi writes about this:

“Of the four Sufi orders popular in India the Chishtis alone sought ecstatic inspiration in music. The Suhrawardis were generally indifferent to it and recommended instead the chanting of the Quran: the Qadiris were opposed to music generally, and to instrumental music in particular. The Naqshbandi attitude to music was even more hostile.”

The silsilahs are of two types: those that adhere strictly to shariah and are called ba-shara, and the non-conformist ones referred to as be-shara. According to Aquil, the terms and the ‘distinction smacks of fatwa-baazi [Islamic rulings] in Islam. If at all one needs to identify and judge some people such as the madaris or qalandars, they may be referred to for being non-conformist, and even somewhat deviant.’

The silsilahs are of two types: those that adhere strictly to shariah and are called ba-shara, and the non-conformist ones referred to as be-shara. According to Aquil, the terms and the ‘distinction smacks of fatwa-baazi [Islamic rulings] in Islam. If at all one needs to identify and judge some people such as the madaris or qalandars, they may be referred to for being non-conformist, and even somewhat deviant.’

Therefore, the term used in this book is non-conformist.

The non-conformists called qalandari or mazjub (intoxicated) do not belong to any one silsilah and spend their time wandering from one place to another. They believed in rejecting the material world, according to scholar Ute Falasch, ‘opting for celibacy, itinerancy, poverty, and mendicancy instead.’

“The deviance from social and moral norms in the attitude towards plety is often presented to the community by peculiar dress and paraphernalia, or the lack of appropriate clothing, as well as a provocative behaviour that is regarded as offensive. Not only the neglect of social standards may characterize this piety, but also that of religious normativity, which is why they are labelled antinomian. It may be expressed in different ways, such as ecstatic states that revolve around music and dance or the experimentation with drugs, mostly hashish, as well as a disregard for religious duties, such as fasting and praying. Because of these aspects, these groups always have been an object of criticism. Movements such as the Qalandariyyah, which spread in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries across the Muslim world up to India, have been looked down upon by the intellectual elite of the society, regarding them as false Sufis who lack religious sentiments or imposters that misuse the sensitivities of the people.”

This is not to say that these fakirs or qalandars were rejected by Muslim society. They found a space for themselves in society and dargahs. Though they did not follow the widespread social norms, there is nothing to suggest that they rejected normative Islamic practices.

Many Sufi silsilahs have flourished in India over time. Abul Fazl lists fourteen orders that were functioning in sixteenth-century India. Of these, the four most prominent ba-shara silsilahs are the Chishti, Suhrawardi, Qadriya, and Naqshbandi. Among the non-conformist silsilahs, the dewangan section of the Madari silsilah and the Rasul-Shahis are two prominent ones in India.

Many Sufi silsilahs have flourished in India over time. Abul Fazl lists fourteen orders that were functioning in sixteenth-century India. Of these, the four most prominent ba-shara silsilahs are the Chishti, Suhrawardi, Qadriya, and Naqshbandi. Among the non-conformist silsilahs, the dewangan section of the Madari silsilah and the Rasul-Shahis are two prominent ones in India.

While mystic centres had been established in many areas by Muslim saints long before the establishment of Turkish rule, the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate saw the emergence of Sufi saints and systematic organization of silsilahs in India. Two of the most important mystic orders — the Chishti and the Suhrawardi — were also introduced in north India during the Delhi Sultanate years. These silsilahs often played an important role in society of the times, as will be discussed later.

The Suhrawardi and the Chishti silsilahs were and are on friendly terms with each other, and the latter even rely on the works of the saints from the former silsilah, like Sheikh Shihabuddin Suhrawardi and Sheikh Hamiduddin Nagauri. The goal of both the orders is to surrender their souls to God’s will and achieve union with the Divine.

Yet, despite all these similarities, there are also differences. The rituals and ceremonies of the two orders reflect their contrasting attitudes towards society and politics. While the Suhrawardis emphasize salat (prayers) and zikr, fasting only in the month of Ramzan, the devotion of the Chishtis leads them not just to offer prayers but indulge in difficult ascetic practices and fast almost continuously. The former believe in eating all that is pure, and in acting righteously, while the latter focus on self-mortification, penance, and meditation.

Their contact with yogis has led the Chishtis to practice zikr with strenuous coordination of limb movements and postures associated with exhalation and inhalation.

The sama mehfils of the Chishtis are attended by the Suhrawardi saints of Delhi but not encouraged by the Multani Suhrawardis.

The Naqshbandis felt it essential to connect and interact with the powers that be, as the life of the rulers had a deep impact on the life of the people. The Suhrawardis mixed with the kings, and ‘gave moral support to them but did not attempt any reorientation of their thought’.

The Chishtis, on the other hand, didn’t seek active involvement but they didn’t shun the rulers totally either, accepting grants and land from them. The well-known Chishti Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya did seek to stay away from rulers, though, and there is a famous incident pertaining to the time when Sultan Jalaluddin Khilji wanted to visit him. Hearing of the ruler’s desire, he is said to have famously quipped that a Sufi khanqah has two doors and if the sultan entered by one, he’d use the other to leave. However, his with Alauddin Khilji were cordial — with the sultan seeking ‘Nizam-ud-Din’s spiritual assistance for knowing the fate of his campaign in southern India — the Sufi master had predicted its victory’.

A very famous story described in Fawaid al-Fuad is of a Sufi saint named Shaikh Ali. The saint was sitting with outstretched legs repairing his tattered cloak when the ruler and his wazir (prime minister) visited him. The wazir asked him to fold his legs, but he remained still and unperturbed. When the ruler drew closer, he showed his fists and said that he has closed his hands instead!

This should not be taken to mean that these saints did not influence the rulers — only that they did it indirectly by narrating stories and parables, or quoting from the hadiths and the life of the Prophet, to show rulers that their tyranny was wrong.

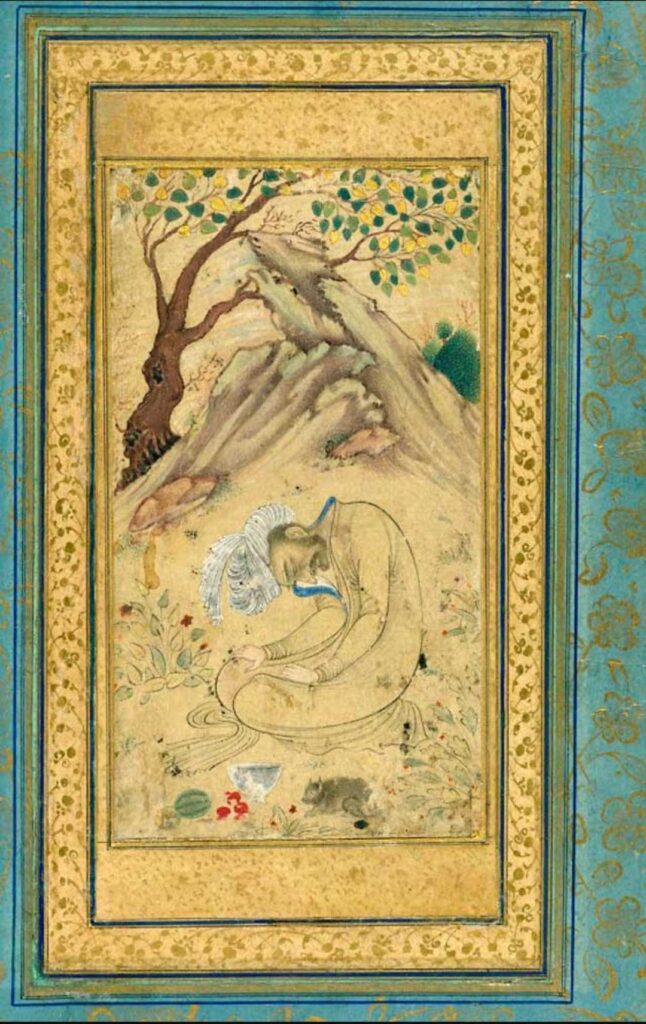

Sufi in a Landscape, Iran, Isfahan, Circa 1650–1660. Los Angeles Museum of County Art.

The Naqshbandi order was the last of the major silsilahs to find its way into India via Khwaja Nasiruddin Ubaidullah Ahrar’s descendants, Khwaja Abdul Shahid, and Khwaja Kalan. The two men came to the Mughal court on Babur’s invitation but didn’t stay long. This silsilah attained popularity later via Khwaja Muhammad Baqi, also known as Baqi Billah Berang.

Apart from the four main silsilahs, there were many offshoots and independent silsilhas, such as the Sabri, Firdausi, Shattari, Kubravi, Warsi, and Kazmiya Qalandari.

Throughout the lands where the khanqahs and dargahs established were governed by the local rulers, the Sufi saints were considered the spiritual rulers. According to historian Sunil Kumar, the political ruler with his army ‘were the intrusive and sometimes violent and usually coercive element that appeared in South Asian history with the establishment of the Sultanate (c. 1200+).’ Further, he says:

“Conversely, as proponents of a mystical Islam, Sufis have been regarded as the ecumenical face of Islam, preaching to the commoners, often using the vernacular, and communicating complex aspects of Islam and Sufi philosophy through pithy maxims derived from the quotidian experiences of the common people and not just the elites. As an extension of this idea, since Sufis were not involved in the mundane temporal world but with abstract, spiritual praxis, historiographical narratives often placed them outside the realm of history and the vicissitudes of change.”

The role of the Sufi was multi-layered and thus they played a very important role in shaping the religious outlook of the rulers, thereby shaping history. Sheikh Abdul Quddus Gangohi, the Chishti Sabri saint, in a letter to Babur sets forth his views in regard to the functions and duties of a Muslim king. He expressed his faith in Babur’s firm conviction in Islam and Hanafi law, and his devotion to the ulema and the Mashaikh, whom he entreated for the theologians, mystics, weak, and the depressed to be maintained and subsidized by the state. In M. Zameer Uddin Siddiqi’s words:

“It was specially stressed that the obligation of deep gratitude to God demanded that [the] all-pervading Justice of the King cast its shadow on the people and that no one should subject another to torture and tyranny and that all the people and soldiers hold fast to all that has been ordained by shara and abstain from all that is forbidden.

Since each silsilah had its own dynamics with the rulers and the people of the subcontinent, I will examine each one separately in the subsequent chapters.

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of Rana Safvi and Hachette India. You can buy In Search of the Divine: Living Histories of Sufism in India, here.

ARCHIVE

Altars

There were two facets to the devotees’ exertions on behalf of Ghazi Miyan: pilgrimage to Bahraich or to a surrogate fair nearer home, and the worship of the Ghazi at domestic altars. The common appellation of Salar Masud’s devotees was Panchpiriya, that is, the followers of the quintet consisting of Ghazi Miyan and his four associates. ‘Panchpiriya’ was the country demotic for Panj Pir, the ‘five saints’ of Islam, especially Shia Islam: the Prophet; Fatima, his daughter; Ali, her husband; and their sons, Hasan and Husain, whose tragic death at the battle of Karbala is mourned widely across the Hindu–Muslim divide.

Late nineteenth-century accounts of north Indian religious life present a bewildering variety of ‘Panch Pirs’ or five personages worthy of devotion and propitiation.

In western Punjab, the quintet frequently consisted of the pedigreed Indian saints of Multan, Ucch, Pakpattan, Ajmer and Delhi. In eastern Punjab and the Gangetic corridor, the Panchpiriya was a demotic concatenation, led invariably by Ghazi Miyan, yet malleable enough to accommodate more generally the myriad ‘deified worthies propitiated by the lowest classes’.

The 1.7 million individuals who were recorded at the 1891 Census as belonging to the Panchpiriy a sect—almost entirely in the Gorakhpur and Banaras divisions of eastern UP—did not have a uniform set of Five Worthies. That year’s census reported Ghazi Miyan, Buhana Pir, Palihar, Amina Sati and Hathile in that order of popularity. These were some of the principal characters from the Ghazi Miyan lore: Hathile the Adamant who helps attack idols in Banaras; the virtuous Amina Sati, banished for feeding a Turkic brother; and Buhana, or Birahana the naked, a marijuanated bodyguard of Masud, in whose lap the warrior saint breathed his last on that first Sunday of June in 1034 .

Ghazi Miyan’s shrine. Credits: Maharajatrails.com

In the villages of eastern UP, the term ‘Panchpiriya’ encompassed equally godlings, worthies and local Muslim saints. Ghazi Miyan and the upright Amina Sati figured in most such groupings, but with curious anomalies. Among the caste of Kahar-palanquin bearers, the ferocious Amina Bhavani was ‘the most venerated’ of their Panchon Pirs—a bloody mother goddess who, uncharacteristically for a Panchpiriya godling, received ‘libations of wine and a young pig’ as offerings. The potters of Basti who worshipped Panchon Pir alongside a clutch of local godlings and forest deities were careful not to offer pigs to these Muslim godlings—‘Musalmani deotār’ as the Panchpiriyas were called generically. Muslim devotees of the Ghazi also shared their Five Pirs with sundry local deified beings, mother goddesses, guardian deities, and disease-causing and repelling worthies. Musalman bangle sellers and armourers propitiated the Hindu goddesses of destruction. Similarly, darzi-tailors and Ghosi herdsmen, ardentworshippers of Ghazi Miyan, retained ‘like many other lower Muhammadan tribes, some Hindu belief and practices’.

The archetypal Panchpiriya follower was a low-caste Hindu, usually from the eastern Banaras-Gorakhpur region. ‘A panchpiriya is a Hindu who worships Musalman saints’—Ghazi Miyan, Hathila, Parihar, Sahja Mai, and Ajab Salar—noted an authoritative compendium on Bihar Peasant Life.

The 1911 Census of UP put the ‘total population of the Hindu castes who worship[ped] these five saints’ at 13.5 million, laying stress on the fact that ‘of the 53 castes devoted to the Panchpiriyas in the province, 44 were ‘wholly or partly Hindus.’7 That was for the province as a whole.

Forty years earlier in 1873 at the Bahraich Fair, ‘the proportion of Mahomedans … was … [found to be] less than the Hindoos’.

The Muslim devotees were largely weavers, cotton carders, butchers and Jats—low-bred razla as these were characterised in a major historical work of early nineteenth century. As for the Hindus, Koris, Kurmi and Ahir peasants and cowherds were the largest groups among the 105,306 pilgrims who entered the shrine on Sunday, 18 May 1873.

A picture from the Ghazi Miyan fair. Credits: livehindustan.com

We know the exact number as entry to the fair that year to was regulated by district officials by the sale of 1 paisa tickets. Local officials were emphatic that it were the Hindu menu peuple (nānh jāt in the local dialect) who were the pukka or ‘real’ devotees of the Miyan. These non-Muslim lower castes appeared ‘to have more belief in Syud Salar than the rest’; they came into the shrine ‘leaping and jumping with the flag bearer[s]’ and made the most offerings of flags, chadars and cash at the Bahraich shrine. Akbar Ali, a junior functionary stationed at the fair in 1873, identified them as ‘the people of the East’—the purabiyas from Gorakhpur-Banaras—‘who came only wearing a “Dhoti”’.

The translation from the Urdu is jarring, but the awkward sartorial image of the true devotee is intriguing and requires some unpacking. Clearly, these pilgrims—members of the Ghazi’s ‘marriage parties’ as they perceived themselves—did not march bare-chested in the scorching heat of May all the way from their villages ‘only wearing a long dhoti’ tied at the waist. Something has been lost in the translation, for it was customary both for the groom and for male members of a marriage party to wear yellow dhotis, dyed traditionally with turmeric or safflower. The curious allusion to the Hindu devotees’ attire, it seems, is a pointer rather to their coloured dhotis, for the same officer set them apart from the ‘white clothes wearing … people of Bahraich who had gone’ to the shrine ‘for the purpose of witnessing the fair’, and who ‘seldom went inside to offer anything’.

Now the dyeing of dhotis was not the norm in eastern UP and Bihar. Mārkīn, that is, mill-made cloth with the distinguishing ‘mark’ of English or Indian mills, was the cloth most used for dhotis, and it was usually white. Where white was customary, the dyeing of cloth had a special significance attached to it. Dhotis are still dyed primarily for marriages and other special occasions, ritual and social—even political. When in 1922, peasants in the Gorakhpur district of eastern UP consciously donned the mantle of Congress volunteers as part of Gandhi’s ‘army’ of non-cooperators, they marched wearing yellow-dyed dhotis. Piyari, or the coloured dhotis worn by males of a groom’s party, were clearly in evidence at Bahraich that summer of 1873—an extension to the fair of a ritual practice followed more routinely at home. Indeed, the Panchon Pir or ‘Heroes Five’, when propitiated at domestic altars, received the special presents due to a groom: the characteristic maur head dress, the full-length dhoti, or the smaller ‘langot’ which grooms put on for a full body massage. The offering of the yellow dhoti or smaller langot was also the norm with two other groom-godlings: Hardiha Lala and the eponymous Dulha Deo.

Hardiha Lala or Hardaul was the ‘great cholera godling’ of north India, propitiated during an epidemic with the sacrifice of ‘goats, fowls and suckers.’ However, among the potters, Hardaul had become ‘a household godling’, worshipped with the cooked food and condiments associated with marriage rituals. And this groom-godling was offered ‘a pair of loin-cloths (dhoti) dyed with turmeric’.

In central India, Hardaul, if propitiated, ensured that weddings took place as scheduled, unmarred by rain or storm. At the slightest sign of a brewing storm, a prayer was offered in praise of the hero. The trope of a storm disrupting marriage is also central to the Ghazi Miyan pilgrimage: an early nineteenth-century poetic description of the festivals of north India alluded to the popular belief that the storm is caused every year by an ogre trying to sweep the fairground clean. For the pilgrims constituting the Ghazi’s marriage party, it is a dust storm that disrupts his marriage at Bahraich on a yearly basis.

The preeminent groom-godling of the tribal communities of the plateau of the Son in Mirzapur and central India was Dulha Deo. In several variants, the groom is killed by lightening or turned to stone on his way to the bride. During the marriage season he was worshipped in the family’s kitchen, and ‘at weddings oil and turmeric [were] offered to him’19—as these are routinely rubbed on the groom’s body in all marriages, including the fateful one of Ghazi Miyan in the month of Jeth in 1034 CE.

It is these intriguing parallels that appear to make Dulha Deo and Ghazi Miyan so alike—both ‘of the class of divine youths, snatched away from life at the height of their strength and beauty’, as a nineteenth-century ethnographer put it. Killed by a tiger before the consummation of his marriage in one variant, for some scholars Dulha Deo was perhaps ‘absorbed into the Ghazi Miyan corpus … to facilitate … the adoption of the [warrior saint] cult by the non- Muslims’ of north India.

Whether parallels suggest that key structural elements of one, presumably prior cult are consciously grafted on to a subsequent cult remains an open question. In any event, merely seeking structural parallels subtracts from the particular inversion of marriage/death embedded in the Ghazi Miyan story.

The poignancy of the Ghazi-Groom story lies crucially in the unraveling of the lines of fate: a mother forewarned of the death of her (long-desired) son at his marriage, yet persisting with the celebrations. It is this tragic figure of mother Mamula straining at the wheel of fortune and failing to turn it around that makes the Ghazi saga more than a death of a bridegroom story. That destiny intervenes, not as the bland binary of victory and death in battle, but as a righteous call to ‘save the cows’, imbues a social dimension to the relatively straightforward tragedy of a groom’s death, foreclosing the possibility of consummation and procreation.

And crucially for history, it is not the transposition of a prior groom-godling on to the figure of Ghazi Miyan, but the obeisance paid to a Turkic warrior saint by a representative swath of Hindu society over several centuries, that propels continually the afterlife of Salar Masud as a hero located in an identifiable conflictual past of the early eleventh century—the time of seventeen incursions into northern India by purported uncle Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni.

That the tensility of the Ghazi Miyan cult may have inhered in a layered memorialisation of medieval Turkish conquerors bewildered the late nineteenth-century British officer-ethnographers. The writer of the 1891 Census Report, which recorded over 1.5 million ‘special worshippers of Panchon Pir’ in UP, faced some difficulty explaining the origin and development of the cult. It was the sheer incredibility, matched by numbers ‘of the adoption into the Hindu system as …beneficient … divinities … those men who were most instrumental in the subjection of Hindus to an alien rule’ that puzzled the Census Commissioner.

The grave of Ghazi Miyan. Credits: scroll.in

For the data were unequivocal that ‘even the Brahman makes his daily offerings of food and water to the spirits of the great [Ghazi] Pir and his associates, and for the low caste man the household worship of the five Pirs is in many districts his sole religious trust’. Officer D. C. Bailee ventured that the cult ‘probably spread through its early adoption by low caste converts [to Islam] who … found their gods … [whom] they had abandoned … in the dead heroes, whom genuine Muhammadans reverenced [sic] as martyrs who had fallen on behalf of their faith’. Unable to quite explain the wide appeal of the cult, Bailee asked his readers to imagine a sequence by which ‘the worship of the low caste Muhammadans at shrines dotted all over the country and known by all extended to the low caste and then to all Hindus’.

One additional feature added to the puzzlement of the English officer: ‘the Muhammdan origin of the worship even when adopted into the households of Hindus is never forgotten’.

It is Muslim Dafalis and servitors of the shrine who benefit from this conundrum of Hindu religiosity, concluded this official notice on the Ghazi Miyan phenomenon—a theme picked up in subsequent decades by publicists out to wean ‘innocent Hindu peasants’ from the clutches of charlatan Dafalis.

Late nineteenth-century notices marvelled at the amazing crossreligious hold of the Ghazi cult even among the most unlikely of communities. It was reported that while thieving in the great fairs of north India, the nefarious Bawarias scrupulously abstained from plundering the tomb and the fair of Ghazi Miyan. Instead, they went annually as pilgrims, and offered their own lahbar (flag) to the Bahraich shrine. There seems to be no reason to believe that this was a new development. Another such ‘criminal caste’, the Barwars, laid aside 1 per cent of their pickings from other fairs while propitiating the Panchpiriya, their ‘tutelary god’, in an elaborate domestic ritual:

“Each Barwar family keeps a small altar in honour of this tutelary god in his house, in the shape of a tomb, at which in the month of Bhadon (August) of every year, on the third or the fifth day of the first half of the month, he sacrifices a domestic fowl and bakes thin loaves of bread called “lugra”, and then gives both the bread and the meat of the sacrificed fowl, together with cooked dāl of gram [chane ki dāl], to a Musalman beggar [Dafali?], who goes about from house to house beating on a kettle-drum.”

That was in the 1880s.

In the Mewat region of villages near Delhi, Dafalis on the day of his martyrdom carried a procession of the Ghazi’s flag, singing in his honour and begging through the main village site and its satellite settlements.

At the other end of the sprawling province of UP, an ethnographic study of an eastern UP village suggests that well into the 1940s, each household of the caste of Teli oil pressers similarly had a clay altar in its house dedicated to Ghazi Miyan.

Every year on return from the Bahraich pilgrimage, householders would offer a big feast (kandūri): goats were sacrificed to the saint and money gifted to the Dafali. At the key domestic puja, the Dafalis were treated like Brahmans: the Teli householders washing their feet, and sprinkling this water inside their houses. The Dafalis would then sing and drum, in an effort to induce Ghazi Miyan to possess one member of the family. In Senapur (the village studied by Cornell University anthropologists in early 1950s), all Teli oil pressers, Kalwar distillers and ‘a majority of clean shudra and untouchable population as well, worshipped Ghazi Miyan as a family god’

By 1953, the ‘ethnographic present’ of the anthropologist Jack Planalp, the cult of Ghazi Miyan had suffered a decline in Senapur. Only two Nonia makers of saltpeter, earth-diggers, households and a few untouchable Chamar leather tanners and more generally agricultural labourers’ families worshipped the Ghazi in the early 1950s, and that too as an individual deity rather than as a ‘family god’. The dominant Thakur landlords of the village had succeeded in enforcing a ban on the public display of the Ghazi’s flag. Dafalis were now restricted to taking out their procession in the segregated untouchable Chamar quarters, away from the main village site. Even then, women of all castes continued to ascribe misfortunes in the family to the dereliction of the Ghazi’s worship. Oil presser Telis seem to have retained their close association with Ghazi Miyan. To this day, a miniature nuptial cot is taken out annually to Bahraich from the house of a Rudauli Teli in celebration of that marriage that death had stymied in the summer of 1034 CE! Nor has the Bahraich Fair been reduced to a solely Muslim affair.

This excerpt has been carried with the permission of Shahid Amin, author of ‘Conquest and Community: The afterlife of Warrior Saint Ghazi Miyan’. You can buy the book here.

In the colonial period, the threat of the lecherous male gaze was used by the new patriarchy to restrict access to employment and public space for women, maintaining a patriarchal division of labour. Read how this process unfolded in our newest excerpt.

Saurav Kumar Rai

__

Was Lala Lajpat Rai's Hindu nationalism congruent with the principles of secularism? Explore our latest excerpt from Vanya Vaidehi Bhargav's fresh off-the-press book - Being Hindu, Being Indian: Lala Lajpat Rai's Ideas of Nation for more.

Vanya Vaidehi Bhargav

__

Popularly, we think that political cartoons question the powerful but what if this was not the case? What if political cartoons, replicated structures of the socially dominant? Read how in our new excerpt on political cartoons featuring Dr. Ambedkar.

Unnamati Syama Sundar

__

On Martyrs' day 2024, read the poet Sarojini Naidu's tribute to Gandhi given over All India Radio two days after his assassination.

Sarojini Naidu

__

On Republic Day, the Indian History Collective presents you, twenty-two illustrations from the first illustrated manuscript (1954) of our Constitution.

Indian History Collective

__

One of the key petitioners in the Ayodhya title dispute was Bhagwan Sri Ram Virajman. This petitioner was no mortal, but God Ram himself. How did Ram find his way from heaven to the Supreme Court of India to plead his case? Read further to find out.

Richard H Davis

__

Labelled "one of the shortest, happiest wars ever seen", the integration of the princely state of Hyderabad in 1948 was anything but that. Read about the truth behind the creation of an Indian Union, the fault lines left behind, and what they signify

Afsar Mohammad

__

How did Bengal get a large Muslim population? Was it conversion by ruling elites was there something deeper at play? Read Dr. Eaton's classic essay to find out.

Richard Eaton

__

An excerpt from Shailaija Paik's new book 'Vulgarity of Caste' that documents the pivotal role Tamasha (the popular art form) has played in reinforcing and producing caste dynamics in Marathi society.

Shailaja Paik

__

In 1942, two sub-districts in Bengal declared independence and set up a parallel government. The second part of our story brings you archival papers in the form of letters, newspaper reports, and judicial records documenting this remarkable movement.

Indian History Collective

__

In 1942, five years before India was independent, two sub-divisions in Bengal not only declared their independence— they also instituted a parallel government. The first in a new series.

Indian History Collective

__

In his own words, read Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi's views on the proselytising efforts taken on by the organisations such as Arya Samaj, Tabhligi Jamaat, and the Church Missionary Society of England.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

__

TIMELINE

-

2500 BC - Present

2500 BC - Present Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas -

2200 BC to 600 AD

2200 BC to 600 AD War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India -

400 BC to 1001 AD

400 BC to 1001 AD The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India -

600CE-1200CE

600CE-1200CE The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power -

c. 700 - 1400 AD

c. 700 - 1400 AD A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History -

c. 800 - 900 CE

c. 800 - 900 CE ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess -

1192

1192 Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India -

1200 - 1850

1200 - 1850 Temples, deities, and the law. -

c. 1500 - 1600 AD

c. 1500 - 1600 AD A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India -

1200-2020

1200-2020 Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra -

1530-1858

1530-1858 Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan -

1575

1575 Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court -

1579

1579 Padshah-i Islam -

1550-1800

1550-1800 Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal -

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ -

1553 - 1900

1553 - 1900 What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? -

1630-1680

1630-1680 Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? -

1630 -1680

1630 -1680 Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times -

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D.

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power -

1818 - Present

1818 - Present The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon -

1831

1831 The Derozians’ India -

1855

1855 Ayodhya 1855 -

1856

1856 “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib -

1857

1857 A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 -

1858 - 1976

1858 - 1976 Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow -

1883 - 1894

1883 - 1894 The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate -

1887

1887 The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar -

1893-1946

1893-1946 A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste -

1897

1897 Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy -

1913 - 1916 Modern Review

1913 - 1916 A Young Ambedkar in New York -

1916

1916 A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier -

1917

1917 On Nationalism, by Tagore -

1918 - 1919

1918 - 1919 What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? -

1920 - 1947

1920 - 1947 How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi -

1921

1921 Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) -

1921 - 2015

1921 - 2015 A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar -

1915-1921

1915-1921 The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore -

1924-1937

1924-1937 What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? -

1900-1950

1900-1950 Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society -

1925, 1926

1925, 1926 Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) -

1928

1928 Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? -

1930 Modern Review

1930 The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality -

1932

1932 Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi -

1933 - 1991

1933 - 1991 Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian -

1935

1935 A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address -

1865-1928

1865-1928 Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism -

1935 Modern Review

1935 The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge -

1936 Modern Review

1936 The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ -

1936

1936 Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 -

1936 Modern Review

1936 The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament -

1936

1936 Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 -

1936

1936 A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature -

1936 Modern Review

1936 The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election -

1937 Modern Review

1937 The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati -

1938

1938 Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) -

1942 Modern Review

1942 IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) -

1942-1945

1942-1945 IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) -

1946

1946 Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 -

1946

1946 An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose -

1946 – 1947

1946 – 1947 “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly -

1946-1947

1946-1947 VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India -

1916 - 1947

1916 - 1947 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read -

1947-1951

1947-1951 Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us -

1948

1948 “My Father, Do Not Rest” -

1940-1960

1940-1960 Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad -

1948

1948 The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation -

1949

1949 Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ -

1950

1950 Illustrations from the constitution -

1951

1951 How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed -

1967

1967 Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari -

1970

1970 R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography -

1973 - 1993

1973 - 1993 Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh -

1975

1975 The Emergency Package: Shadow Power -

1975

1975 The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control -

1977 – 2011

1977 – 2011 Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal -

1984

1984 Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star -

1916-2004

1916-2004 Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” -

2008

2008 Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? -

2006 - 2009

2006 - 2009 Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee -

2020

2020 The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read -

2021

2021 Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives