ARCHIVE

My Future Visit to America, 1883

— Anandibai Joshi

. . . Our subject to-day is, “My future visit to America, and public inquiries regarding it.” I am asked hundreds of questions about my going to America. I take this opportunity to answer some of them. . .

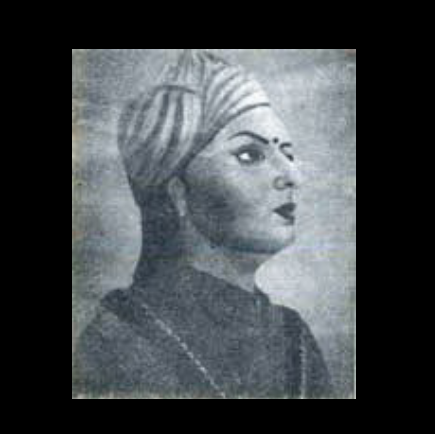

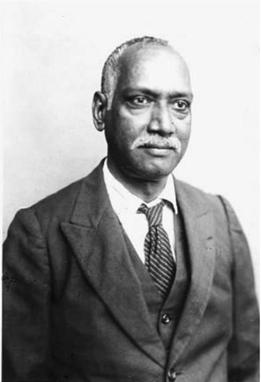

Anandibai Joshi

Why do I go to America? I go to America because I wish to study medicine. I now address the ladies present here, who will be the better judges of the importance of female medical assistance in India. I never consider this subject without being surprised that none of those societies so laudably established in India for the promotion of sciences and female education have ever thought of sending one of their female members into the most civilized parts of the world to procure thorough medical knowledge, in order to open here a College for the instruction of women in medicine. There is probably no country that would not disclose all her wants and try to stand on her own feet. The want of female doctors in India is keenly felt in every quarter. Ladies both European and Native are naturally averse to expose themselves in cases of emergency to treatment by doctors of the other sex. There are some female doctors in India from Europe and America, who, being foreigners and different in manners, customs and language, have not been of such use to our women as they might. As it is very natural that Hindu ladies who love their country and people should not feel at home with the natives of other countries, we Indian women absolutely derive no benefit from these foreign ladies. They indeed have the appearance of supplying our need, but the appearance is delusive. In my humble opinion there is a growing need for Hindu lady doctors in India, and I volunteer to qualify myself for one.

There is one College at Madras, and midwifery classes are opened in all the Presidencies; but the education imparted is defective and not sufficient, as the instructors who teach the classes are conservative, and to some extent jealous. I do not find fault with them. That is the characteristic of the male sex.

Are there no means to study in India? No. I do not mean to say there are no means, but the difficulties are many and great. There is one College at Madras, and midwifery classes are opened in all the Presidencies; but the education imparted is defective and not sufficient, as the instructors who teach the classes are conservative, and to some extent jealous. I do not find fault with them. That is the characteristic of the male sex. We must put up with this inconvenience until we have a class of educated ladies to relieve these men.

I am neither a Christian nor a Brahmo. To continue to live as a Hindu and to go to school in any part of India is very difficult. A convert who wears an English dress is not so much stared at. Native Christian ladies are free from the opposition or public scandal which Hindu ladies like myself have to meet within and without the zenana. If I go alone by train or in the street some people come near to stare and ask impertinent questions to annoy me. Example is better than precept. Some few years ago, when I was in Bombay, I used to go to school. When people saw me going with my books in my hands, they had the goodness to put their heads out of the window just to have a look at me. Some stopped their carriages for the purpose. Others walking in the streets stood laughing and crying out so that I could hear:—

“What is this? Who is this lady who is going to school with boots and stockings on?”

“Does not this show that the Kali Yuga has stamped its character on the minds of the people?”

Ladies and gentlemen, you can easily imagine what effect questions like these would have on your minds if you had been in my place!

Once it so happened that I was obliged to stay in school for some time, and go twice a day for my meals to the house of a relation. Passers-by, whenever they saw me going, gathered round me. Some of them made fun, and were convulsed with laughter. Others, sitting respectably in their verandahs, made ridiculous remarks, and did not feel ashamed to throw pebbles at me. The shopkeepers and venders spit at the sight of me, and made gestures too indecent to describe. I leave it to you to imagine what was my condition at such a time, and how I could gladly have burst through the crowd to make my home nearer!

If I go to take a walk on the Strand, Englishmen are not so bold as to look at me. Even the soldiers are never troublesome; but the Babus lay bare their levity by making fun of everything. “Who are you?” “What caste do you belong to?” “Whence do you come,” “Where do you go?” are, in my opinion, questions that should not be asked by strangers.

Yet the boldness of my Bengali brethren cannot be exceeded, and it is still more serious to contemplate than the instances I have given from Bombay. Surely it deserves pity! If I go to take a walk on the Strand, Englishmen are not so bold as to look at me. Even the soldiers are never troublesome; but the Babus lay bare their levity by making fun of everything. “Who are you?” “What caste do you belong to?” “Whence do you come,” “Where do you go?” are, in my opinion, questions that should not be asked by strangers. There are some educated native Christians here in Serampore who are suspicious; they are still wondering whether I am married or a widow; a woman of bad character or ex-communicated! Dear audience, does it become my native and Christian brethren to be so uncharitable? Certainly not. I place these unpleasant things before you, that those whom they concern most may rectify them, and those who have never thought of the difficulties may see that I am not going to America through any whim or caprice.

Anandibai Joshee graduated from Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP) in 1886. Seen here with Kei Okami (center) and Sabat Islambooly (right). All three completed their medical studies and each of them was among the first women from their respective countries to obtain a degree in Western medicine.

Why do I go alone? It was at first the intention of my husband and myself to go together, but we were forced to abandon this thought. We have not sufficient funds; but that is not the only reason. There are others still more important and convincing. My husband has his aged parents and younger brothers and sisters to support. You will see that his departure would throw those dependent upon him into the arena of life, penniless and alone. How cruel and inhuman it would be for him to take care of one soul and reduce so many to starvation! Therefore I go alone.

Shall I not be excommunicated when I return to India? Do you think I should be filled with consternation at this threat? I do not fear it in the least. Why should I be cast out, when I have determined to live there exactly as I do here? I propose to myself to make no change in my customs and manners, food or dress. I will go as a Hindu, and come back here to live here as a Hindu. I will not increase my wants, but be as plain and simple as my forefathers, and as I am now. If my countrymen wish to excommunicate me, why do they not do it now? They are at liberty to do so. I have come to Bengal and to a place where there is not a single Maharashtrian. Nobody here knows whether I behave according to my customs and manners, or not. Let us therefore cease to consider what may never happen, and what, when it may happen, will defy human speculation.

Shall I not be excommunicated when I return to India? Do you think I should be filled with consternation at this threat? I do not fear it in the least. Why should I be cast out, when I have determined to live there exactly as I do here? I propose to myself to make no change in my customs and manners, food or dress. I will go as a Hindu, and come back here to live here as a Hindu.

What will I do if misfortune befall me? Some persons fall into the error of exaggerated declamation, by producing in their talk examples of national calamities and scenes of extensive misery which are found in books rather than in the world, and which, as they are horrid, are ordained to be rare. A man or a woman who wishes to act does not look at that dark side which others easily foresee. On necessary and inevitable evils which crush him or her to dust, all dispute is vain. When they happen they must be endured, but it is evident they are oftener dreaded than experienced. Whether perpetual happiness can be obtained in any way, this world will never give us an opportunity to decide. But this we may say, we do not always find visible happiness in proportion to visible means. It is not a thing which may be divided among a certain number of men. It depends upon feeling. If death be only miserable, why should some rejoice at it, while others lament? On the other hand, death and misery come alike to good and bad, virtuous and vicious, rich and poor, travelers and housekeepers; all are confounded in the misery of famine and not greatly distinguished in the fury of faction. No man is able to prevent any catastrophe. Misery and death are always near, and should be expected. When the result of any hazardous work is good, we praise the enterprise which undertook it; when it is evil, we blame the imprudence. The world is always ready to call enterprise imprudence when fortune changes.

Some say that those who stay at home are happy, but where does their happiness lie? Happiness is not a readymade thing to be enjoyed because one desires it. Some minds are so fond of variety that pleasure if permanent would be insupportable, and they solicit happiness by courting distress. To go to foreign countries is not bad, but in some respects better than to stay in one place. [The knowledge of history as well as other places is not to be neglected. The present state of things is the consequence of the former, and it is natural to enquire what were the sources of the good that we enjoy or the evils we suffer. To neglect the study of sciences is not prudent; it is not just if we are entrusted with the care of others. Ignorance when voluntary is criminal, and one may perfectly be charged with evils who refused to learn how he might prevent it. When the eyes and imagination are struck with any uncommon work, the next transition of an active mind is to the means by which it was performed. Here begins the true use of seeing other countries. We enlarge our comprehension by new ideas and perhaps recover some arts lost by us, or learn what is imperfectly known in our country. So I hope my going to America will not be disadvantageous.]

[I have seriously considered our manners and future prospects and find that we have mistaken our interests.] Everyone must do what he thinks right. Every man has owed much to others. His effort ought to be to repay what he has received. [This world is like a vast sea, mankind like a vessel sailing on its tempestuous bosom. Our prudence is its sails; the sciences serve us for oars; good or bad fortunes are the favorable or contrary winds and judgement is the rudder; without this last the vessel is tossed by every billow and will find ship-wreck in every breeze.] Let us follow the advice of Goldsmith who says: “Learn to pursue virtue of a man who is blind, who never takes a step without first examining the ground with his staff.” I take my Almighty Father for my staff, who will examine the path before He leads me further. I can find no better staff than He.

I ask my Christian friends, “Do you think you would have been saved from your sins, if Jesus Christ, according to your notions, had not sacrificed his life for you all?” Did he shrink at the extreme penalty that he bore while doing good? No, I am sure you will never admit that he shrank! Neither did our ancient kings Shibi and Mayurdhwaj. To desist from duty because we fear failure or suffering is not just. We must try. Never mind whether we are victors or victims. Manu has divided people into three classes.

And last you ask me, why I should do what is not done by any of my sex? [To this I cannot but say that we are bound by the rights of society to the labours of individuals. Everyone has his duty and he must perform it in the best way he can; otherwise his fear and backwardness are supposed to be a desertion of duty. It is very difficult to decide the duties of individuals. It is enough that the good of the whole is the same with the good of an individual. If anything seems best for mankind, it must evidently be best for an individual and that duty is to try one’s best, according to his sentiments to do good to the society.] According to Manu, the desertion of duty is an unpardonable sin. So I am surprised to hear that I should not do this, because it has not been done by others. [I cannot help asking them in return “who should stand the first if all will say so?”] Our ancestors whose names have become immortal had no such notions in their heads. I ask my Christian friends, “Do you think you would have been saved from your sins, if Jesus Christ, according to your notions, had not sacrificed his life for you all?” Did he shrink at the extreme penalty that he bore while doing good? No, I am sure you will never admit that he shrank! Neither did our ancient kings Shibi and Mayurdhwaj. To desist from duty because we fear failure or suffering is not just. We must try. Never mind whether we are victors or victims. Manu has divided people into three classes. [Those who do not begin for fear of failure, are reckoned among the meanest; those who begin but give it up through obstacles belong to the middle class; and those who begin but [do] not give it up till they attain success, through repeated difficulties, are the best. Let us not therefore be guilty of the very crime we absolutely hate. The more the difficulties, the greater must be the attempt. Let it be our boast never to desist from anything begun. Sufferance should be our badge.]

The Hindu Sea Voyage Movement in Bengal, 1894

— Standing Committee on the Hindu Sea-Voyage Question

. . . Hindoo young men, in appreciable numbers, proceed to England to receive education in the universities, to qualify for the Bar, to compete for the Indian Civil Service, for the Medical Service, and in various other ways to equip themselves for the practical work of life. The number is on the increase, of gentlemen, who, if all restrictions were removed, would like to proceed to Europe for purposes of travel, and all the pleasures and profits it brings. There is a growing desire also in some quarters to make excursions to the West for commercial purposes. It cannot be a matter of indifference to the Hindoo community if the gentlemen who come back from Europe after perfecting their education and enlarging their experience are to be received back into society or excluded from it. It cannot be a matter of indifference also whether adventurous gentlemen should have free scope given to them in the matter of travel, or they should have their ambition curbed by social restrictions. The welfare of a country is the welfare of its individuals, and no subject can be of greater national importance than the discussion of the limits which custom may have prescribed to the liberty of movement of the men who compose the nation.

On economic grounds alone the question of sea-voyages is of great practical importance. People may feel themselves driven by sheer necessity to try their fortune in remote countries, to seek new careers, learn the arts of foreign nations, and come back home with added qualification and augmented resources. If these poor, adventurous souls should be denied the opportunities they sought, it is not they alone that would be sufferers, but the country as well. Social restrictions, however, are likely to prove an effectual barrier to most of them, and the legitimacy of those restrictions therefore deserves serious consideration. The possibility of natives of India marching out in quest of occupation to distant lands may now appear to be too remote, and as a dream. But there are reasons to believe that if the restrictions were repealed or relaxed, opportunities of adventure would often be utilized.

Hindoo society is governed by rules which have their basis in the Hindoo religion. That religion is enshrined in the shastras, of which the recognised, authoritative interpreters are the Pandits. The Pandits give their vyavasthas or ordinances founded upon the texts. These are accepted by the leaders of the different castes which make up society, and they thus come to regulate usage. On the subject of sea-voyage, therefore, the first thing necessary was to obtain the opinions of the Pandits. That step has already been taken. It was not of course to be expected that the opinion of every single Pandit in Bengal should be obtained, but many of the leading Pandits have been consulted. . . . The next step that was taken was to refer the subject to some of the leading members of Hindoo society, all of the higher castes, and their opinions have also been recorded. Attention may be specially called to the opinion of so distinguished an apostle of Hinduism as Bankim Chandra Chatterjee. Lastly, a large body of public opinion from various sources, which had been elicited by the discussion, has been set forth in its proper place. It includes the opinions as well of eminent Englishmen as of newspapers, Hindoo and English. These opinions have a value which must not be overlooked. Pandits interpret the shastras; social leaders judge practicability; but an intelligent public have also a right to be heard, for, unfettered by considerations of authority and custom, they are able to utter the voice of abstract reason. Mere reasonableness is not an excuse for an innovation, but it will hardly be denied that a practice which is manifestly contrary to reason cannot long remain unmodified, and that so long as it does exist it will work mischief. The opinions, therefore, of intelligent and educated men who are even outsiders to our society have an importance that should not be underrated. . . .

For a full appreciation of the issues involved in the sea-voyage question it is necessary to bear in mind a few well-known facts which may be thus stated:

- For a long time past the practice of eating things condemned by Hindoo rules or custom has been pretty common in Hindoo society, but the gentlemen who have indulged in such practices have not been put out of caste. Their number is growing. They include not merely schoolboys or wild young men, not merely a few insignificant people who might be regarded as the waifs and strays of society, but also and mainly, elderly, respectable, influential gentlemen, some of whom have been recognised as social leaders. In their own private residences or those of their friends, European or Native, in garden houses, in hotels kept by Europeans or Mohammedans, on steamers, in railway refreshment rooms, numbers of Hindoo gentlemen dine in the European style, and the orthodox members of society find it convenient to connive at these practices. Demand creates supply. Hence it is we find that restaurants where European dishes are offered, are multiplying. They are set upon largely frequented streets, and near offices and theatres. Year after year, in every town in which the Indian National Congress is held, it is found necessary by the organizers to make special arrangements for those delegates and visitors who are to live in the European style. In a word, the rules as regards orthodox living are every day trampled underfoot, and the violations are in no way punished.

- There was a time when it was considered an un-Hindoo practice to drink pipe-water. Not only is pipe-water drunk today by Hindus of unquestioned orthodoxy, but aerated waters, European wines and spirits, and medicines prepared by Europeans, are habitually consumed by large numbers of them. Bread, biscuits and confectionery of European or Mahomedan manufacture are also largely indulged in.

- Hindu society has not been able consistently to keep out of its pale all those who have made voyages to Europe. Some of them received recognition in society, at any rate among their friends and relations; and after their death, their sons and other relations have had no difficulty in being accepted as members of society, though no prayaschitta [penance] had ever been performed by them.

- Some of those that have made voyages to Europe have, on their return to this country, lived, permanently or for a time, with their relations. Many of their friends and relations have also dined with them on many occasions. Orthodox society has never ceased to recognise these friends and relations.

- Either for purposes of business or on pleasure trips, several Hindoos have made voyages to Rangoon, to Madras, to Ceylon. Nobody dreams of excommunicating them.

- Esteemed Hindoo gentlemen have on some occasions taken part, as host or guest, in entertainments, almost of a public character, conducted in the European style. The names of those who dined on the occasions have sometimes been reported in the newspapers, but orthodox society has never cared to take any notice of their errors.

- Hindoo Society has exhibited nothing like consistency, observed no definite principle, in dealing with those of its members who have made voyages to Europe. The same men that recognise them on one occasion do not recognise them on another. They dine with them today and decline to dine with them tomorrow. If they are to be excommunicated, those who have dined with them, or otherwise mixed with them in formal social intercourse on ceremonial occasions, should be excommunicated also. But the utmost that the ultra-orthodox members of the community seek to do is to omit to recognise only the travelled men, while they permit themselves to mix freely with men who have been tainted by association with the chief offenders.

What is the inference to be drawn from these facts? Obviously this, that it would not be fair or consistent to exclude from society men who had made only a voyage by sea without transgressing Hindoo rules of living. Surely it cannot be contended that a mere crossing of the sea is a grosser offence than living in a non-Hindu style, or even as gross as that. When open, or, at any rate, well-known violations of Hindoo rules of eating and drinking are connived at and excused, neither reason nor orthodoxy demands the exclusion of men who living as Hindoos had merely travelled to the West. . . That a voyage by sea as such, does not militate against Hinduism seems to be tacitly admitted by Hindoo society by the manner in which it has been treating Swami Vivekananda’s visit to America. The Swami, so far from being regarded as an apostate by reason of his visit, is being looked up to as a prince of Hindoos and the pride of Hinduism. It is inconceivable, therefore, that the sea-voyage movement should be opposed on grounds either of religion or logic. If there could be any objection to it, it would be its conservative rather than its revolutionary character. . .

Letter regarding the Movement, 1894

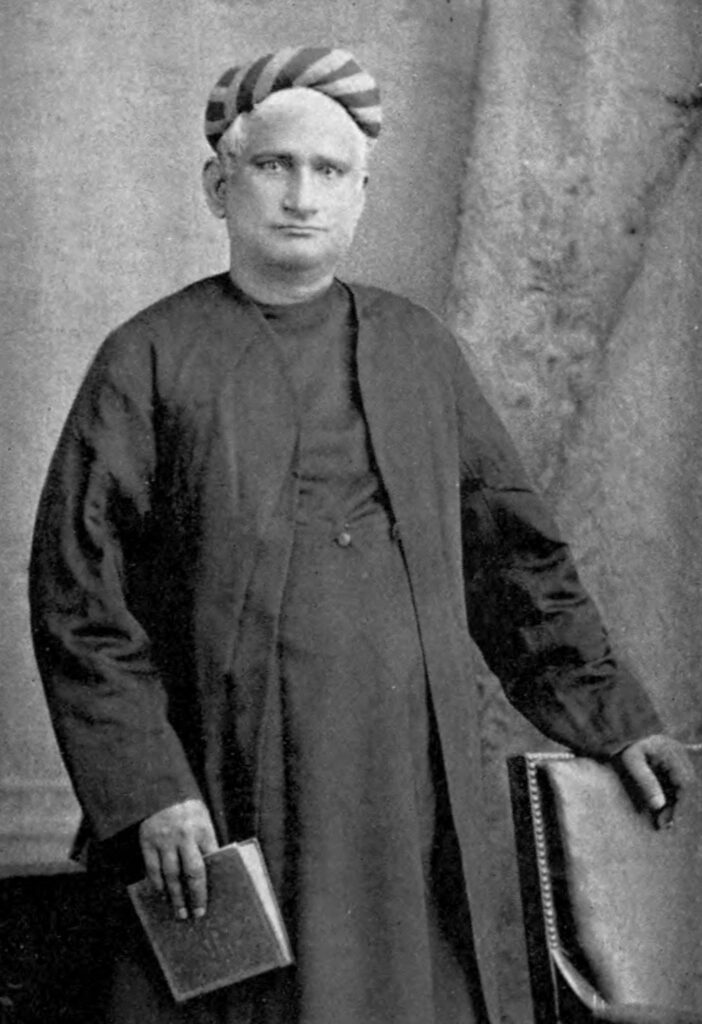

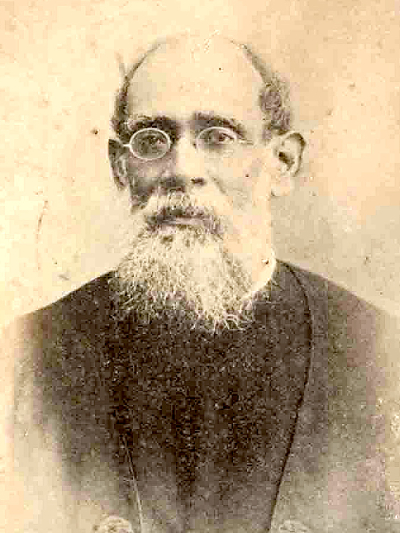

— Bankim Chandra Chatterjee

. . . The questions which you wish me to answer are such as are best answered by professors of the Dharma Sastras. I do not profess the Dharma Sastras, nor am I prepared to undertake the office of expounding them. But I have no objection to offer a few observations regarding the present agitation about sea-voyages by Hindus.

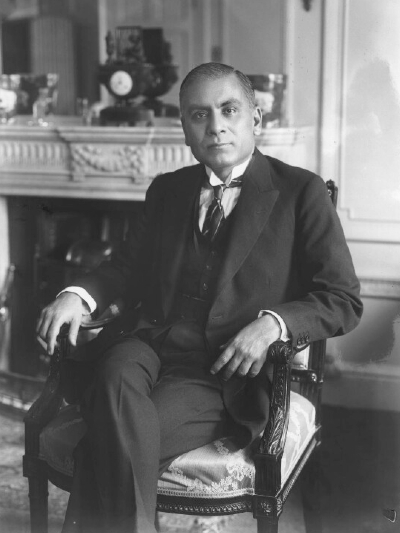

Bankim Chattapadhyay

In the first place, I do not believe that it is either possible or desirable to promote social reforms by invoking the authority of the Sastras. I had to object on the same ground to the late lamented Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar’s proposals to suppress polygamy with the aid of the Sastras; and I have seen no ground since then to change my opinion. This opinion I hold on two grounds. The first is, that Bengali society is governed not by the Sastras but by custom. It is true, that very often custom follows the Sastras; but as often again custom conflicts with the Sastras. When there is such a conflict custom carries the day.

You seek to collect the behests of the Sastras, regarding sea-voyages, and to induce society to follow them;—are you prepared to induce society to be guided by the Sastras on all other matters as well? One of the precepts of the Dharma Sastras is, that it is the duty of the Shudras to perform menial offices for the Brahmins and other superior castes;—do the Shudras of Bengal follow the precept?

The second reason for my opinion is that if society were everywhere governed by the Sastras, it is doubtful whether the result will be social welfare. You seek to collect the behests of the Sastras, regarding sea-voyages, and to induce society to follow them;—are you prepared to induce society to be guided by the Sastras on all other matters as well? One of the precepts of the Dharma Sastras is, that it is the duty of the Shudras to perform menial offices for the Brahmins and other superior castes;—do the Shudras of Bengal follow the precept? The Sastras are not a guide here. Are any of you prepared to enforce this precept? Do you think that any endeavours to enforce it will succeed? Will a Sudra Judge of the High Court leave the bench, or will the prosperous Shudra zamindar leave the zamindar’s seat, to respectfully tend the feet of the Brahmin manufacturer of eatables? By no means. Bengali society obeys a portion of the Dharma Sastras according to its necessities. The rest it has cast off because of its necessities. The same feeling of necessity may induce it to cast off what still remains. What good then there is in seeking to ascertain the commands of the Dharma Sastras?

My own conviction is that it is impossible to carry out social reformation regarding any particular practice merely on the strength of the Sastras without religious and moral regeneration along the whole line. This I have tried to explain at length in my work on Krishna Charitra. I have already stated that society here is governed by custom, not by the Sastras. Reforms in custom can be achieved only when there is an advance in religion and morals along the whole line. The present agitation is the outcome of the advance that has already taken place. As society advances gradually in religion and morals, the objections against sea-voyages will disappear, or if any opposition should still continue to exist, it would be powerless. But so long as the full measure of advance is not attained, so long it will be impossible to make sea-voyages acceptable to society.

But it has also to be observed that none of us are aware of the exact measure of opposition which exists in Bengali society towards sea-voyages. I see that whoever commands the necessary means and is otherwise favorably circumstanced, does proceed to Europe when willing to do so. I have not come across a single instance in which the journey to Europe was abandoned out of respect to the authority of the Sastras. But I am also bound to admit that most of those who return from Europe remain outside the pale of Hindu society. It is a question whether the fault lies with them, or with Hindu society. On their return to this country they voluntarily keep away from Bengali society by adopting European habits and customs. They separate themselves from us by adopting foreign costumes, foreign habits of living, and foreign usages. Those who on their return from Europe did not adopt this course have in many instances been re-admitted into Hindu society. If gentlemen returning from Europe did generally resume habits and usages conformable to Hindu society, it is impossible to say that they would be as a body left outside its precincts.

I have not come across a single instance in which the journey to Europe was abandoned out of respect to the authority of the Sastras. But I am also bound to admit that most of those who return from Europe remain outside the pale of Hindu society. It is a question whether the fault lies with them, or with Hindu society.

Lastly, I have to point out that before deciding the question as to whether sea-voyages are in conformity to the Dharma Sastras of the Hindus, it is necessary to decide whether it is not in conformity to Dharma (religion) itself. Must we reject that which is conformable to religion but opposed to the Dharma Sastras, merely because it is opposed to the Dharma Sastras? Many will say that alone which is conformable to the Hindu Dharma Sastras is religion; and that which is not conformable to them is irreligion. I am not prepared to admit this. None of the older sacred books of Hindus say so. Krishna in the Mahabharata says— “Dharma is so called because it holds all. Know that for certain to be Dharma, which contributes to the general welfare.” If the Mahabharata is not guilty of a falsehood, if he whom the Hindus worship as the Divine Incarnation is not guilty of falsehood, then that which is for the general welfare is religious. Now, are sea-voyages for the general welfare or not? If they are, why should they be opposed because they do not happen to be encouraged by the Smritis? . . . Sea-voyages are conformable to religion because they tend to the general good. Therefore, whatever the Dharma Sastras may say, sea-voyages are conformable to the Hindu religion.

These excerpts have been carried courtesy the permission of Rahul Sagar and Juggernaut. You can buy To Raise a Fallen People, here.

ARCHIVE

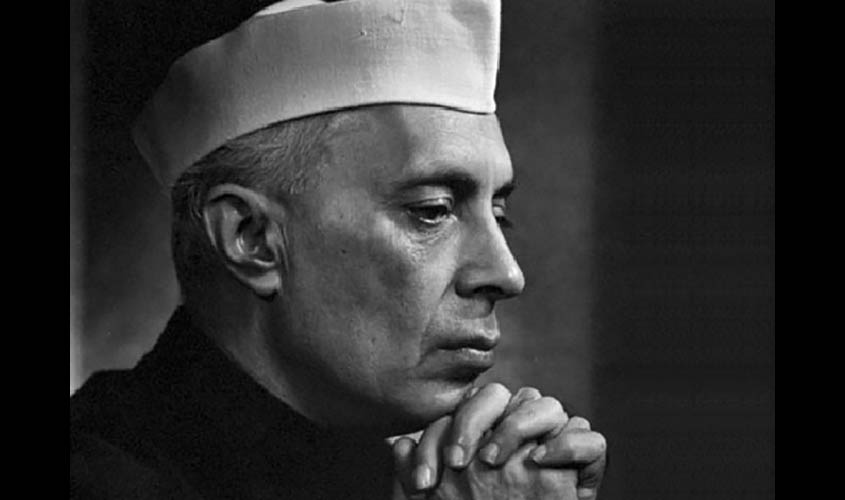

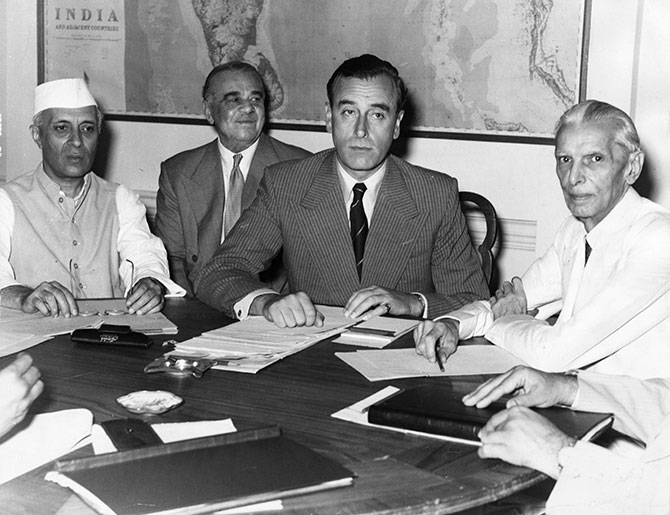

New Leaders and Their Different Ideologies

After the failure of the non-cooperation movement, the Indian people had lost hope. Communal conflict between Hindus and Muslims wiped out the little resolve that still remained. But once a sense of awakening has come upon a nation, it cannot remain asleep for long. In just a few days, the public is back on its feet and ready for battle. Today, India is full of life and vigour again; it is awake. We may not see clear signs of a great mass movement, but the ground is certainly being prepared for it. Many new leaders with a modern sensibility are emerging. Young leaders are at the forefront this time, and youth movements are proliferating. Only young leaders are commanding the attention of patriotic-minded Indians. Even the tallest veteran leaders are being left behind.

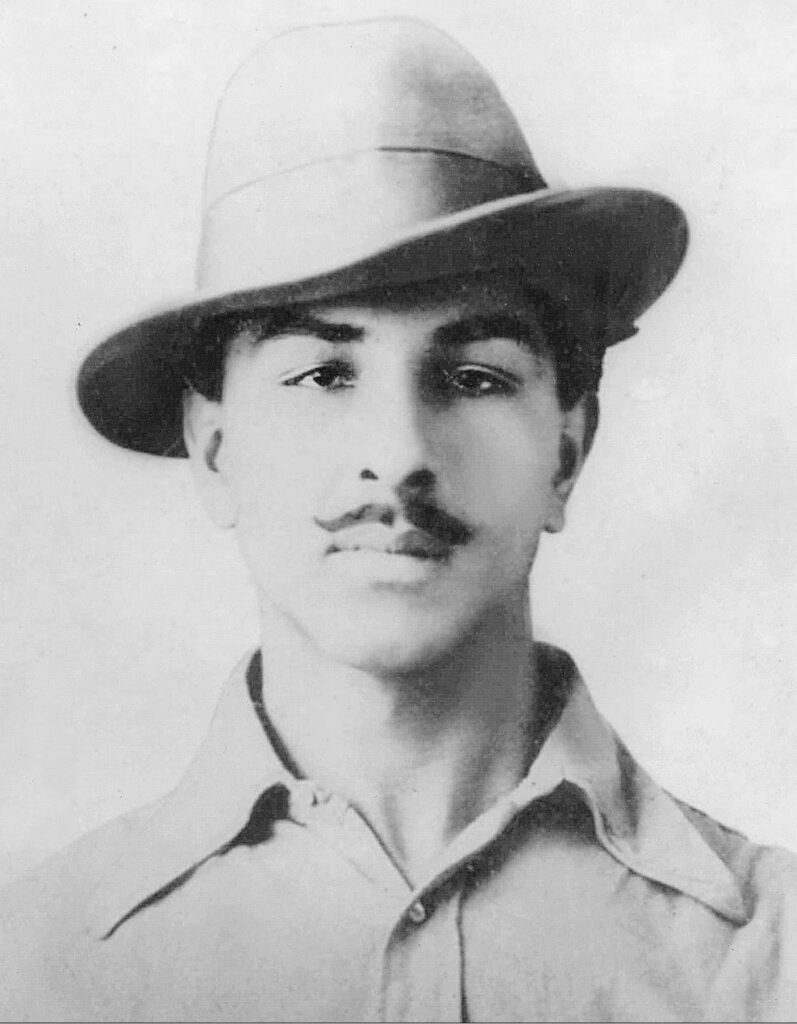

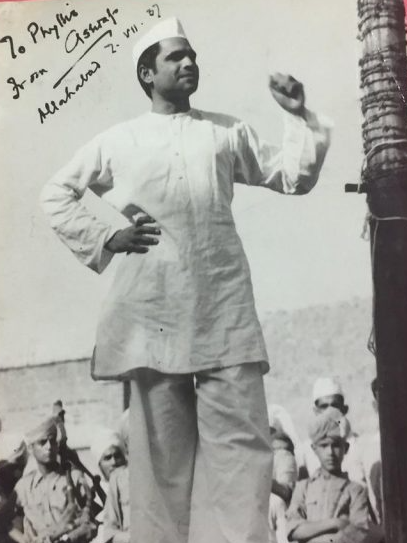

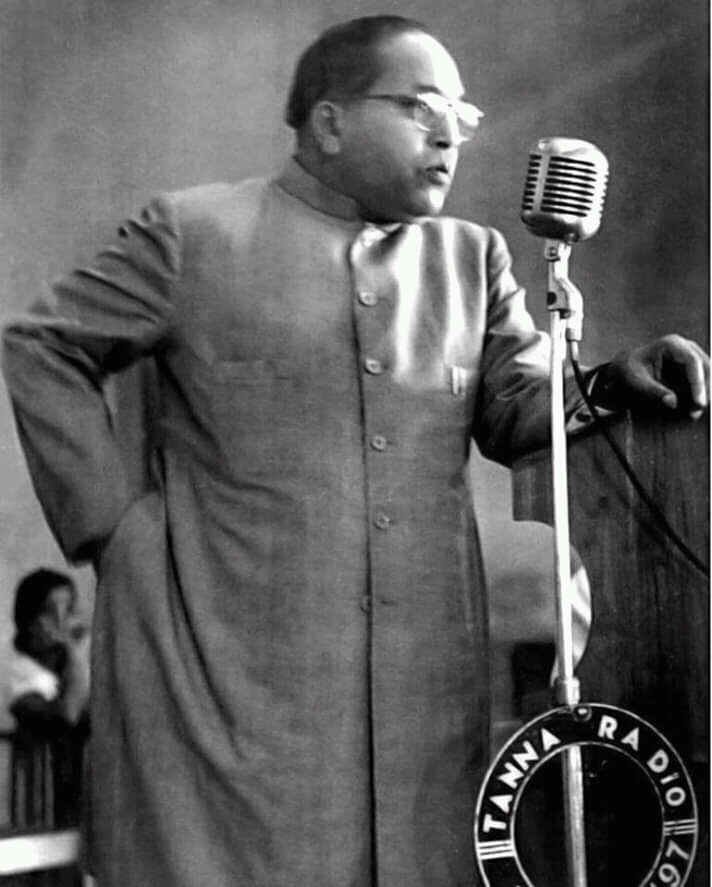

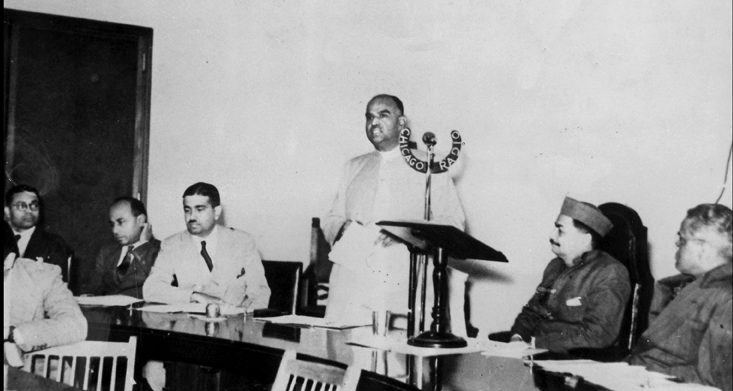

Bhagat Singh

Many new leaders with a modern sensibility are emerging. Young leaders are at the forefront this time, and youth movements are proliferating. Only young leaders are commanding the attention of patriotic-minded Indians.

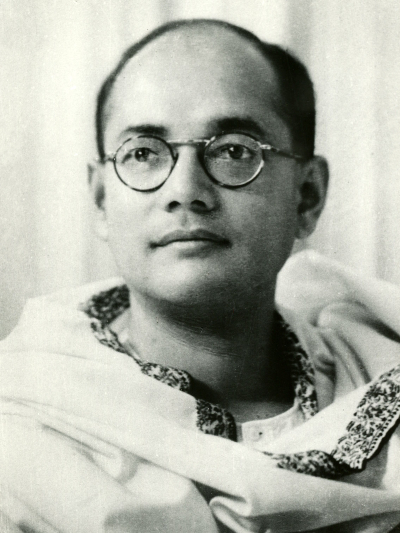

The leaders who have gained prominence this time are the venerable Subhash Chandra Bose of Bengal and the eminent Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. These are the two leaders who appear to be rising above all others in India and involving themselves in youth movements in particular. They are both uncompromising champions of Indian independence; both intelligent and genuine patriots. And yet, their ideologies are as different as night and day. One is believed to be a devotee and proponent of India’s ancient culture and the other a committed follower of western civilization. If one is regarded as tender-hearted and sensitive, the other is spoken of as a quintessential revolutionary. Our attempt in this essay will be to present their respective ideologies before the public, so that people understand the difference between the two and make up their own minds.

But before we examine the ideas of these two leaders, it is important to mention another who is a champion of independence just as they are, and is also a prominent figure in certain youth movements. Sadhu Vaswani may not be as well known as the leading lights of the Congress, he may not occupy a special place in the country’s political arena, yet his influence is apparent among the youth, who will shape the country’s future. The organization Sadhu Vaswani founded — Bharat Yuva Sangh — has a particular hold on young Indians. Vaswani’s ideology can be summed up in a single phrase: back to the Vedas. This call was first given by the Arya Samaj. It is based on the belief that the Almighty has poured all the knowledge of the world into the Vedas. No progress is possible beyond them. Therefore, the world has not and cannot achieve anything greater than the wonders our very own India had achieved in the ancient past! So that is the entire faith of people like Vaswani. Which why he says:

“Up until now, our politics has either considered Mazzini and Voltaire as its ideals, or it has sought inspiration from Lenin and Tolstoy. This, when they should know that they have far greater ideals in our ancient rishis…”

Vaswani is convinced that once upon a time, our country had reached the final summit of development and today there is no reason for us to move forward at all; we only need to go back to the past.

Vaswani is a poet. Everything about his ideology is poetic. He is also a great practitioner of religious dharma. He wants to establish ‘Shakti-dharma’. He says, ‘At this time we need shakti — power — more than ever. He does not use the word ‘shakti’ only for India. He sees the word as the path and means to a kind of Devi, a special godhead. Like a very emotional poet he tells us:

‘For in solitude have I communicated with her, our admired Bharat Mata and my aching head has heard voices saying — “The day of freedom is not far off.” Sometimes indeed a strange feeling visits me and I say to myself: Holy, holy is Hindustan. For still is she under the protection of her mighty Rishis and their beauty is around us, but we behold it not.’

It must be the poet’s lament that makes him declare, over and over like a man deranged or distracted: ‘Our mother is the greatest. She is the mightiest. No one alive can vanquish her!’ In this fashion, driven purely by emotion, he ends up saying things like this: ‘Our national movement must become a purifying mass movement, if it is to fulfill its destiny without falling into class war one of the dangers of Bolshevism.’

He believes that all one needs to do is to say — ‘Go among the poor, go to the villages, give them free medicines’ — and our mission is accomplished. He’s a romantic poet. His poetry can offer no special purpose, it can only excite the heart a little. In fact, he has no vision to offer, except great noise about our ancient civilisation. He gives nothing to young minds. His only aim is to fill every heart with plain emotion. He has obvious influence among the youth, and it is growing. His ideas are regressive and patchy, as we’ve seen above. Such ideas have no direct connection with politics, and yet they have a significant effect. Mainly because it is the youth who are the future, and it is among them that such ideas are being propagated.

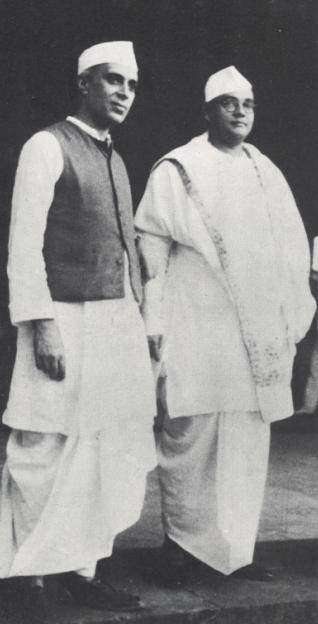

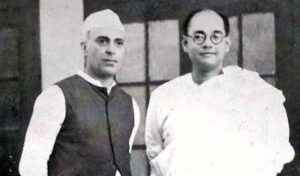

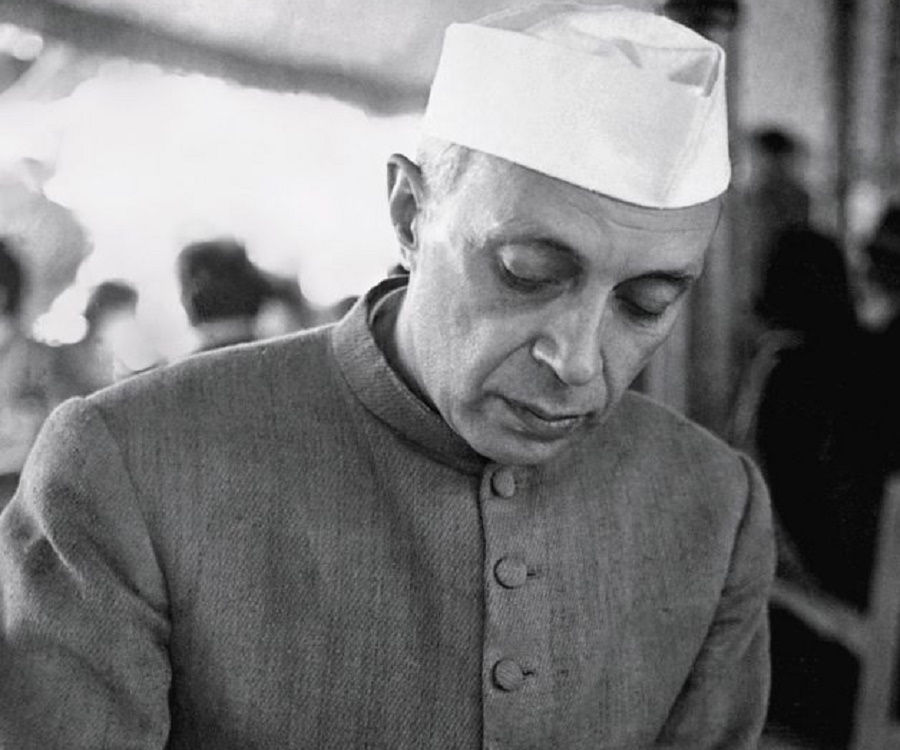

The leaders who have gained prominence this time are the venerable Subhash Chandra Bose of Bengal and the eminent Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. These are the two leaders who appear to be rising above all others in India and involving themselves in youth movements in particular. They are both uncompromising champions of Indian independence; both intelligent and genuine patriots. And yet, their ideologies are as different as night and day.

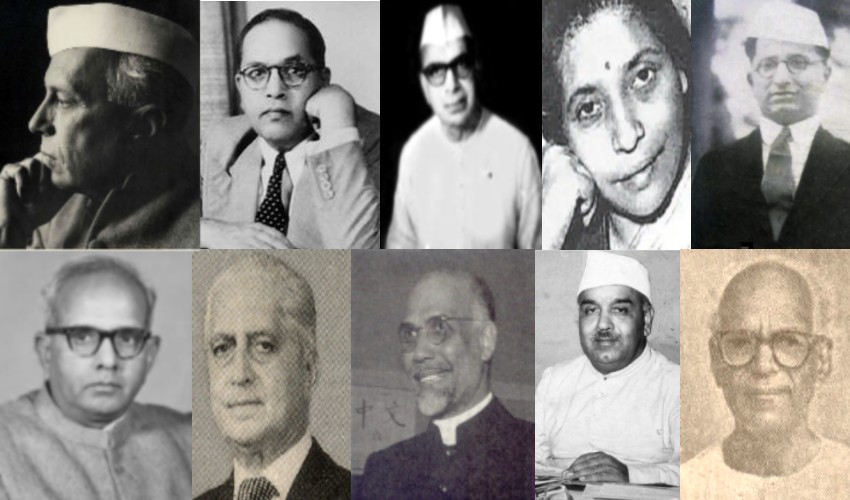

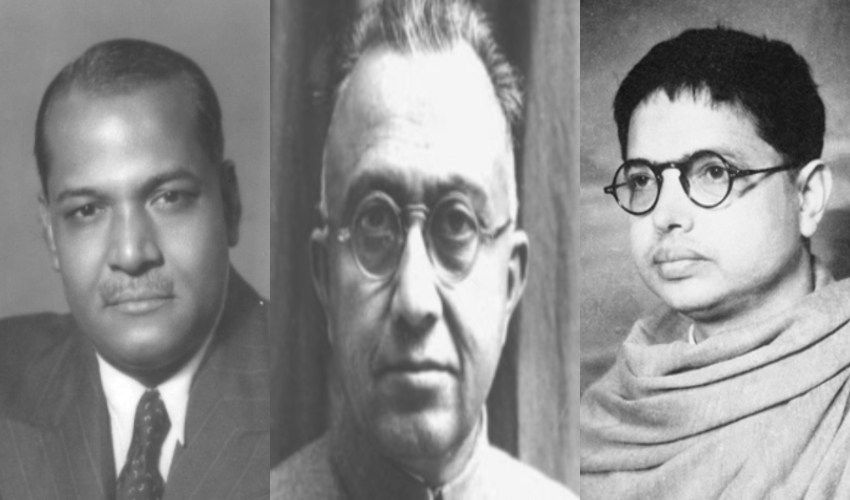

Jawaharlal Nehru with Subhas Chandra Bose

Let us now return to Subhash Chandra Bose and Jawaharlal Nehru. During the last three months, they have both chaired many conferences and put their thoughts and ideas before people. The government considers Subhash Babu a member of the group that is committed to overthrowing it, for which reason it had charged and imprisoned him under the Bengal Act. Upon his release, he was chosen as the leader of the Extremist group [of the Congress]. He espouses Purna Swaraj [complete independence], and argued for this in his presidential address at the Maharashtra session [of the Congress].

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru is the son of the Swaraj Party leader Motilal Nehru. He is a barrister, and a very learned man. He has travelled to Russia and other countries. He is also a leader of the Extremist group, and it was due to his efforts, and those of his fellow leaders, that the resolution for Purna Swaraj was passed and adopted at the Madras session. Before this, he had spoken emphatically in favour of Purna Swaraj at the Amritsar session.

And yet, the two leaders are poles apart in their thinking. Reading the transcripts of their speeches at the Amritsar and Maharashtra sessions, this difference was apparent to us. But the difference became clear as daylight after a speech delivered in Bombay. Pandit Nehru was chairing the conference and Subhash Bose made a speech. He is a very emotional Bengali. He began his address with the statement that India has a special message for the world. It has a lesson in spirituality for humanity. And then he launched into his speech like a man in the grip of disorienting emotion — ‘Behold the Taj Mahal on a moonlit night and think of the vision of that heart that imagined it. Recall that a Bengali novelist has written that “our flowing tears hardened into stone within us”. Bose also declares that we should return to the Vedas. In his Poona [Congress session] address, he had expounded on ‘nationalism’ and said that internationalists criticize nationalism as narrow, chauvinistic ideology, but that this is a mistake. Indian nationalist thought, according to him, is nothing of the kind. It is not chauvinistic. It is not born of self-interest, and it is not oppressive, because at its root is the philosophy of Satyam Shivam Sundaram — Truth is bountiful and beautiful.

The same old romanticism. Pure emotionalism. And [like Vaswani], Bose too has great faith in his ancient past. He sees only greatness in this ancient era. In his thinking, there’s nothing new in the system of panchayati raj, or the rule of the people, which he says is very old in India. He goes so far as to say that Communism isn’t new to India either. Anyway, that day in Bombay, he went on long and hard about India’s special message for the world.

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, like many others, holds an entirely different view: ‘Every country thinks it has a special message for the world. England has arrogated to itself the right to teach the world culture. I don’t see anything special that belongs to my country alone. But Subhash Babu has great belief in such things!’ Nehru also says, ‘Every youth must rebel. Not only in the political sphere, but in social, economic and religious spheres also. I have not much use for any man who comes and tells me that such and such thing is said in the Koran. Everything unreasonable must be discarded, even if they find authority for it in the Vedas and the Koran.’

One man thinks our old systems are very superior; the other man believes we should rebel against these systems. Yet the latter is called emotional, sensitive, and the former a transformative revolutionary!

These are the thoughts of a true revolutionary, while Subhash Chandra’s are the thoughts of someone who wants to replace one regime with another. One man thinks our old systems are very superior; the other man believes we should rebel against these systems. Yet the latter is called emotional, sensitive, and the former a transformative revolutionary! At one point Pandit Nehru says:

“To those who still fondly cherish old ideas and are starving to bring back the conditions which prevailed in Arabia 1300 years ago or in the vedic age in India, I say that it is inconceivable that you can bring back the hoary past. The world of reality will not retrace its steps, the world of imagination may remain stationary.”

This is why it feels necessary to revolt.

Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhash Chandra Bose

Subhash Babu supports Purna Swaraj, complete independence, because the British are people of the West and we are of the East. Pandit Ji’s position is that we need to establish our own rule so that we can change the entire social structure. This is why we must have complete and absolute independence.

Subhash Babu is in sympathy with labour, the working class, and wants to improve their condition. Pandit ji wants to bring in revolution and change the existing system altogether. Subhash Chandra is emotional and romantic — he is giving the young food for their hearts, and only their hearts. The other man is an epochal change — maker who is fuelling not just the heart but also the mind:

“They should aim at Swaraj for the masses based on Socialism. That was a revolutionary change which they could not bring about without revolutionary methods… Mere reform or gradual repairing of the existing machinery could not achieve the real, proper Swaraj for the general masses.”

Subhash Babu feels the need to focus on national politics only as long as it is necessary to safeguard and promote India’s position in world politics. But Pandit ji has freed himself of the narrow confines of plain nationalism and emerged into an open field.

Subhash Babu feels the need to focus on national politics only as long as it is necessary to safeguard and promote India’s position in world politics. But Pandit ji has freed himself of the narrow confines of plain nationalism and emerged into an open field.

Now the ideas of the [two] leaders are before us. Which way should we incline? One Punjabi newspaper has heaped praise upon Subhash Chandra and said of Pandit ji and others that such rebels destroy themselves beating their heads against stone. We must of course remember that Punjab has always been a rather emotional province. People’s passions here rise very quickly and just as quickly subside, like foam.

Subhash Chandra doesn’t appear to be providing any intellectual nourishment, only food for the heart. The need of the hour now is for the youth of Punjab to understand and strengthen revolutionary ideas. At this time, Punjab needs food for the mind, does not mean we should become his blind followers. But as far as ideas are concerned, the young people of Punjab should align themselves with him, so that they can know the true meaning of revolution, realize the need for a revolution in India, understand the significance of revolution in the world at large, and so on Through serious thought and analysis, the youth should bring clarity and conviction to their ideas, so that even in times of very little hope, times of disillusionment and defeat, they should not lose direction, stand tall and strong against a hostile world and not give up. This is how the public will achieve the goal of revolution.

— Bhagat Singh

This is a translation of Bhagat Singh’s ‘Naye Netaaon ke Alag Alag Vichar’ in the July 1928 issue of the journal Kirti. This translated version has been carried courtesy the permission of Purushottam Agrawal.

You can buy Who is Bharat Mata? On History, Culture and the Idea of India: Writings by and On Jawaharlal Nehru here.

ARCHIVE

Dalit ‘Viranganas’ and Reinvention of 1857

The past three decades particularly have seen a flourishing of popular dalit literature, pamphlets and booklets, which have emerged as a critical resource for deeper insights into dalit politics and identity. Dalits themselves are disentangling received knowledge from the apparatus of control. This literature brings fresh hope, as it is believed that now dalits are in charge of their own images and narratives, witness to and participants in their own experience. They are rescuing dalit culture from degeneration and stereotypes, and bringing in a new dalit aesthetic. They are not the “Other”, and are themselves articulating critical questions of choice and difference.

Most of this literature is mass produced in thousands, usually in the form of thin pamphlets. It is sold in large quantities through small ad hoc stalls put up at various public rallies, conglomerations and melas of dalits, on pavements, and through dalit presses and publishers, reaching through such commercial networks into a large number of dalit households. Most of the authors are not known much or well established. There is a technical lack of sophistication in the production of these pamphlets, and they are usually thin, reproduced with many editions, priced very cheaply at approximately between Rs 2 and Rs 50, printed on cheap paper, through private dalit presses. They are written in simple colloquial Hindi, and encompass various literary genres.

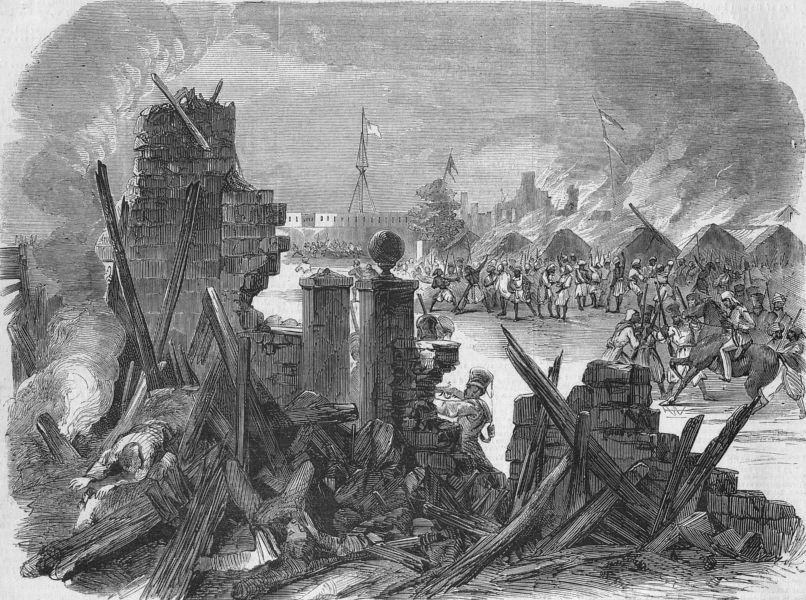

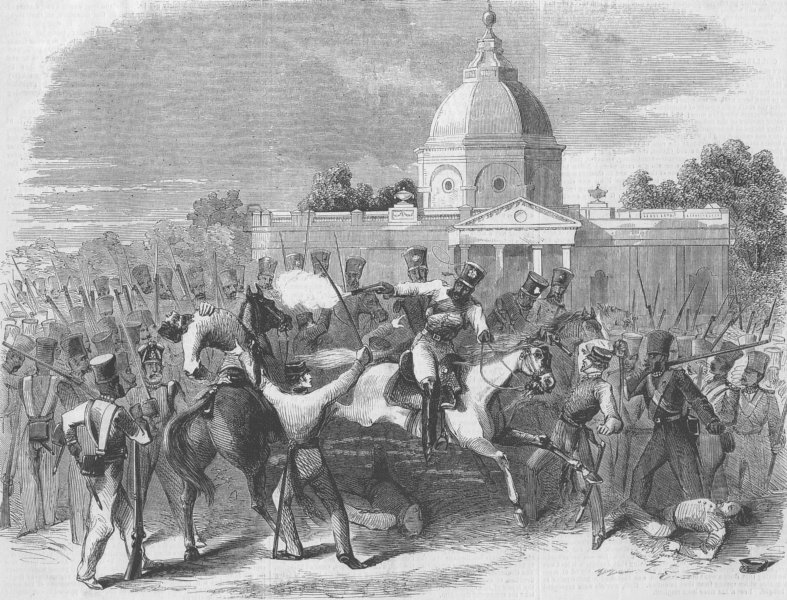

“The Sepoy revolt at Meerut,” wood-engraving from the Illustrated London News, 1857

While covering a huge range, from works by and on Ambedkar, status of dalits and atrocities on them, reservations, conversions, dalit literary writings, theatre and songs, what interests me here are the representations of nationalist struggle in this literature. It has been argued that dalits have had an ambivalent relationship with both Indian nationalism and colonialism, often contradictory with the views of dominant Hindu communities. Some dalit intellectuals argue that the British liberated the dalit masses from the oppressions of Hindu society, and that British rule was good for the dalits. In Uttar Pradesh, many of the activists within the dalit movement had articulated similar ideas as early as the 1920s. For example, the Adi-Hindu movement in the 1920s and 1930s and its leaders were against the Congress and the national movement, and were pro-British. However, in post-independent India, given the imperative political assertions by the dalits, there has been a need felt to assert the nationalist credentials of the dalits and the positive role they played in the freedom struggle. Thus dalit histories have come out with copious volumes on their contribution and role in the independence movement, digging out hitherto ignored accounts. The social constructions of the role played by dalits in the struggle for India’s freedom have thus been changed by the dalits themselves in tandem with changing social and political conditions in specific historical moments within dalit communities. What is significant, however, is that weather dalits argue for an anti-nationalist or a pro-nationalist stance in the colonial period, their agendas and articulations are substantially different, departing from and challenging conventional nationalists and mainstream historians of the period. Dalit perspectives on their own histories offer a dramatically different account from the received wisdoms taught in most Indian universities.

Thus dalit histories have come out with copious volumes on their contribution and role in the independence movement, digging out hitherto ignored accounts. The social constructions of the role played by dalits in the struggle for India’s freedom have thus been changed by the dalits themselves in tandem with changing social and political conditions in specific historical moments within dalit communities. What is significant, however, is that weather dalits argue for an anti-nationalist or a pro-nationalist stance in the colonial period, their agendas and articulations are substantially different, departing from and challenging conventional nationalists and mainstream historians of the period. Dalit perspectives on their own histories offer a dramatically different account from the received wisdoms taught in most Indian universities.

Promoting alternative accounts of role of dalits in the freedom struggle, this literature portrays itself as the real and comprehensive truth. It catalogues their enormous sacrifices and enumerates the many occasions on which dalits rose in defence of the nation. These stories are endlessly repeated in pamphlets after pamphlets, though they have not found their way in canonised/ mainstream history. What is being proposed by dalit writers here is the concreteness and the almost palpable truth of this history. This popular dalit literature can be seen to represent alternative and dissident voices, coexisting with and simultaneously challenging hegemonic ideologies. It is a counterpoint to hegemony. It also reflects Bakhtin’s notions of dialogics and heteroglossia, and Stuart Hall’s concept of “oppositional” decoding, challenging “dominant-hegemonic” and “negotiated” reading positions.

1857 Revolt, Conventional Histories and Dalit Retellings

The revolt of 1857 figures in a major way in the narratives of popular dalit histories, where a completely alternative account of the revolt emerges, converging histories, myths, realities and retelling of the pasts. The outbreak of 1857 has been regarded as a memorable episode in Indian history. It was in a sense one of the first formidable revolt that had broken out against foreign domination. To prove the nationalist credentials of dalits, their popular histories have thus completely transformed 1857.

Before going into these narratives let us briefly examine conventional and standardised histories of the revolt. Various strands of historiography largely seem to converge, particularly on the question of the caste character of the revolt. According to nationalist historians like S B Chaudhuri, Tara Chand and R C Mazumdar, the social composition of 1857 consisted of the ruling class and the traditional elite of the society, who were the “natural leaders” of the revolt. The elitist character of the revolt is highlighted by referring to it as a general movement of the Muslims and the Hindus-princes, landholders, soldiers, scholars and theologians. Marxist scholars seem to fall within the same paradigm where they basically see the revolt as a last attempt of the elite medieval order to halt the process of its dissolution and recover its lost status. Thomas R Metcalf too emphasises that it was not merely a mutiny nor a war of independence. For him 1857 was “a traditionalist movement in which those who had the most to lose in the new sought the restoration of the old pre-British order”. In his significant work, Eric Stokes, while highlighting the local background of the upsurge, also argues that it was the fear of the loss of an upper caste status due to the use of fat-greased cartridges that precipitated the uprising. He shows how ashraf Muslims, brahmins and rajputs had secured a near monopoly over entry into the Bengal army and they were afraid of a loss to their status. Many other contemporary accounts too emphasise the hurt and the fears of pollution felt up upper caste Hindus as an important reason for the revolt. How do dalit histories of 1857 sit in with these accounts? The purity/pollution ties of the upper castes and classes, linked with the crossing of seas or biting of the flesh of the cow or the pig, do not fit in with dalits. There have been other scholars who have emphasised the lower caste base of the revolt as well. Thus, for example, Rudrangshu Mukherjee emphasises the mutual dependence between peasantry and talukdars, which provided the basis for common and united action at this tumultuous juncture. He thus links the seemingly disjointed and contradictory realms of the elite and the common masses. Gautam Bhadra also highlights the common leaders of the revolt. However, even these scholars, in spite of their best intentions, do not explicitly focus on dalits and even less so on women. As Bhadra says, “In all these representations what has been missed out is the ordinary rebel, his role and his perception of alien rule and contemporary crisis” (emphasis in original).

How do dalit histories of 1857 sit in with these accounts? The purity/pollution ties of the upper castes and classes, linked with the crossing of seas or biting of the flesh of the cow or the pig, do not fit in with dalits. There have been other scholars who have emphasised the lower caste base of the revolt as well. Thus, for example, Rudrangshu Mukherjee emphasises the mutual dependence between peasantry and talukdars, which provided the basis for common and united action at this tumultuous juncture. He thus links the seemingly disjointed and contradictory realms of the elite and the common masses. Gautam Bhadra also highlights the common leaders of the revolt. However, even these scholars, in spite of their best intentions, do not explicitly focus on dalits and even less so on women.

With the rise of the dalit movement and literature in north India, the history of 1857 however has been completely inversed, with many histories of it being rewritten, particularly since the 1960s. Contemporary dalit perceptions and compositions of 1857 are very different from scholarly historical studies on the subject, or even constructed “popular” perceptions, and represent the historical consciousness of the revolt in the public memory of the dalits. The pamphlets and books on dalit histories of 1857 – which may also be described as unofficial dalit histories of colonial India – combine myths, memories and histories, depicting dalit versions of the revolt. Dalit writers are attempting here to look upon the mutiny as part of their struggle for freedom. The revolt has taken on the character of a dalit resistance, where alternative dalit heroes are represented as the real symbols of 1857 in dalit popular nationalist consciousness. The rebel dalit heroes – some constructed, some exaggerated, some “discovered” – have become heroes fighting for a free India. In these accounts, the armies of soldiers against British consist largely of dalits. New dalit histories argue that the dalits had nothing much to lose in pre-British times, as their condition had been miserable even then. So it was actually dalits who fought for independence in 1857, while the upper caste Hindus and Indian rulers only fought to restore their rule. The focus of this literature is no longer on the sepoys or the greased cartridges, but on dalits groaning under foreign oppression. As the famous dalit poet Bihari Lal Harit says regarding 1857:

nai, dhobi, kurmi, kachchi/bharbhuje bhaat kumhaar lare.

Lare khak rub mochi dhanak/sab daliton ke parivar lare.

(Barbers, washermen, kurmis, gardeners, grain-parchers, bards and potters fought.

Cobblers rolling in dust and cotton-carders fought. All dalit families fought.)

Dalit narratives of 1857 deploy an impassioned language, and are written usually by dalit men who are not trained historians. These writers are inspired by altogether different sentiments, and their writings reveal the inner dynamics of dalit politics as well. They are writing history with a mission by claiming a past and using it for the furtherance of their future. One of their purposes in writing inspirational histories of this kind is to stimulate dalit nationalism, dalit patriotic sentiment, and their pride. They are rewriting history to provide dignity to the dalits. Present day feelings are ascribed to dalit heroes of 1857, and they are seen as teaching a moral lesson that the dalits of today need to emulate the heroic deed of their past heroes, and fight for their rights today as well. In the dalit literature, 1857 has become the Caesar of India, which is more powerful when dead than alive. It has got inscribed as a heroic popular uprising fought by the lowly, a symbol of challenge to the British power by the dalits. It entailed united dalit activism and sacrifice of enormous numbers. Its history is constantly being reshaped in the present socio-cultural and political context. It has an inspirational quality, an effective conviction, which signifies a present political importance.

Wood-engraving depicting the massacre of officers by insurgent cavalry at Delhi

1857 has also become a marker for the dalits to prove their nationalist credentials, and claim their own space in the freedom struggle and the history of a nation in the making. By this, dalits also seek to win acceptance from the wider society by creating and legitimising a space for themselves within the nationalist narratives. However, these histories are not just reinventions of the past or inspirational histories. They also reveal a deep impassioned plea to recognise the unsung heroes of the revolt, who were often illiterate and left no written records. Folksongs, oral narratives and myths also thus become the basis of these accounts. As says one:

yatra-tatra sarvatra milegi, unki gaatha ki charcha.

kintu upekshit veervaron ka – kabhi nahin chapta parcha.

(Here, there and everywhere, you will find discussions on their deeds, but the scorned [dalit] heroes are never written about in papers.)

However, this literature has not found its way in mainstream, conventional and canonised historical narratives of 1857, be it school textbooks, restructured curricula or scholarly works. The reasons for this may be camouflaged in a language about “quality”, authenticity and written historical records. Dalit literature on 1857 may be seen as “inferior”, sensational, mimetic and unintellectual, though moving and passionate. The cannon fodder of 1857 history has thus kept dalit versions of 1857 away from the loci of authority – university departments, literary associations and syllabi. Dalit literature on 1857 occupies a different publicpolitical domain and presents an alternate form of knowledge. The language and vocabulary deployed in dalit literature on 1857 stresses the need for dalitisation of history and to examine the dalit leaders of the revolt. Dalits claim that reinventing 1857 from a dalit perspective is imperative in order to represent reality. While appropriating the past, dalit writers are simultaneously questioning the blurred presentations and partial/prejudiced histories of historians, arguing that dalit heroes of the revolt have been completely erased by them. They argue that most historians implicitly hold their high caste biases when writing histories of 1857.

Dalit ‘Viranganas’ of 1857

A chief feature of these popular dalit histories of 1857 is the way dalit women get represented in them. Here myths about dalit viranganas (heroic women) are being reinvented as a potent symbol for identity formation and as a critical part of a movement to define political and social positioning of dalits. Narratives of dalit viranganas abound, with a long list of them littering the Indian past. These women are ascribed particularly heroic roles. In fact, dalit female icons, engaged in radical armed struggles, far outnumber dalit men in 1857. These writings invoke political and public dalit memories, where women like Jhalkari Bai of the kori caste, Uda Devi, a pasi, Mahabiri Devi, a bhangi and Asha Devi, a gurjari, all stated to be involved in the 1857 revolt, have become the symbols of bravery of particular dalit castes and ultimately of all dalits.

Jhalkari Bai statue at Gwalior

Representing the dalit woman in certain modes in 1857 also indicates ways in which pasts are remembered and retailed, and the relationships of such pasts to people’s sense of belonging. As has been remarked, representation can pose afresh the relationship between memory, myth and history, oral and written, transmitted and inscribed, stereotypicality and lived history. Reading the histories of dalit women viranganas of 1857 through the lens of representation adds important dimensions to our understandings of it, while also revealing tensions between the pedagogical and the performative, the rhetoric and the reality. Foucault has argued that all representations are by their very nature insidious instruments of surveillance, oppression and control – both tools and effects of power. However, if we argue that representations of dalit women are constructed only to support dominant modes of ideology, and that their aim is ultimately coercive, then how can we use this space also for confrontation? Does representation have the scope of carving out more contingent, varied and flexible modes of resistances? Within the field of representation, counter-images can emerge, challenging hegemonic images.

Representing the dalit woman in certain modes in 1857 also indicates ways in which pasts are remembered and retailed, and the relationships of such pasts to people’s sense of belonging. As has been remarked, representation can pose afresh the relationship between memory, myth and history, oral and written, transmitted and inscribed, stereotypicality and lived history. Reading the histories of dalit women viranganas of 1857 through the lens of representation adds important dimensions to our understandings of it, while also revealing tensions between the pedagogical and the performative, the rhetoric and the reality.

In India, there have been a significant number of studies concerned with the representations of high caste, middle class women, particularly of the colonial period. My own earlier work had focused on this. While significant in their own right, there is an implicit implication in these works that since dalit women fall within the category of “women”, their representation need not be singled out for a separate study. Thus, portrayal of dalit women of the colonial period as a major area of feminist scholarly examination has remained negligible and on the fringes. Dalit literature on 1857 provides us a significant moment to examine alternative representations of dalit women. It can be an important source of insight into gender politics from a dalit perspective and a site of struggle over meanings. While highlighting the centrality of these dalit women viranganas in the symbolic constitution of dalit identity, this literature simultaneously reveals a world turned upside down, challenging textual, academic and historical narratives of 1857. It further shows how resistance to dominant discourses about dalit women has been coded and lived by various groups of dalits within dalit communities at different historical moments. Dalit women viranganas emerge here as not only visible, but as conspicuous and central characters, and objects of attention and adulation.

Thus for example, to take the case of Jhalkari Bai, there has been a proliferation of a vast number of popular Hindi tracts, written by various authors, and cultural invocations on her, including comics, poems, plays, novels, biographies, ‘nautankis’, and even magazines and organisations in her name. To name just a few, there is the comic Jhalkari Bai; poems variously titled Virangana Jhalkari Bai Kavya, Jhansi ki Sherni: Virangana Jhalkari Bai ka Jeevan Charitra and Virangana Jhalkari Bai Mahakavya; plays and nautankis called Virangana Jhalkari Bai and Achhut Virangana Nautanki; novels and biographies like Virangana Jhalkari Bai and Achhut Virangana; and a magazine called Jhalkari Sandesh, published from Agra. Various dalit magazines have published articles on her. Similarly, on Uda Devi, there are poems, plays, stories and magazines penned and narrated on various occasions.

The various narratives go something like this. Jhalkari Bai is depicted as an ‘amar shaheed’ (immortal martyr) of 1857, belonging to the kori caste. Jhalkari Bai hailed from Jhansi. Her husband Puran Kori was an ordinary soldier in the kingdom of raja Gangadhar Rao. Jhalkari Bai is depicted as an ideal woman, occasionally helping her husband in his traditional occupation of cloth weaving, and also sometimes accompanying him to the royal palace. She is stated to be brave since her childhood and further got training from her husband in archery, wrestling, horseriding and shooting. Her face and body structure is said to resemble Lakshmibai exactly. Slowly Jhalkari Bai and Lakshmibai become friends. Jhalkari was entrusted with the charge of leading the women’s wing of the army, known as the “Durga Dal”. When the 1857 revolt began, the rulers were mostly interested in just saving their thrones and it was not a freedom struggle for them. It was dalits who made it a freedom struggle. When the British besieged the fort of Jhansi, Jhalkari Bai fought fiercely. She urged Rani Lakshmibai to escape from the palace and instead she herself took on the guise of the Rani and led the movement from Dantiya gate and Bhandari gate to Unnao gate. Her husband died while fighting with the British and when Jhalkari Bai heard this, she became a “wounded tigress”. She killed many British, and managed to hoodwink them for a long time, before they discovered her true identity. According to some versions, suddenly many bullets hit her, and she died. Some state that she was set free, lived till 1890 and became a legend of her time.

Uda Devi

Uda Devi is said to have been born in the village Ujriaon of Lucknow. She was also known as Jagrani and was married to Makka Pasi. She became an associate of Begum Hazrat Mahal, and Uda formed a women’s army, with herself as the commander. Her husband became a martyr in the battle at Chinhat. Uda decided to take revenge. When the British attacked Sikandar Bagh in Lucknow under Campbell, he was faced with an army of dalit women:

koi unko habsin kehta, koi kehta neech achchut.

abla koi unhein batlaye, koi kahe unhe majboot.

(Some called them black African women, some untouchable. Some called them weak, others strong.)

It is significant here that even W Gordon-Alexander’s account of the storming of Sikandar Bagh by British troops states:

In addition…there were…even a few amazon negresses, amongst the slain. These amazons having no religious prejudices against the use of greased cartridges, whether of pigs’ or other animal fat, although doubtless professed Muhammadans, were armed with rifles, while the Hindu and Muhammadan East Indian rebels were all armed with musket; they fought like wild cats, and it was not till after they were killed that their sex was even suspected.

Uda Devi was one of them, who is said to have climbed over a ‘pipal’ tree and shot dead, according to some accounts 32 and some 36, British soldiers. One soldier spotted someone in the tree and shot the person dead, and only then it was discovered that she was a woman. Realising her brave feat, even British officers like Campbell bowed their heads over her dead body in respect.

Asha Devi Gurjari is portrayed as a leader to a large number of young girls and women and it is stated that on May 8, 1857, she along with a large number of other women like Valmiki Mahaviri Devi, Rahimi Gurjari, Bhagwani Devi, Bhagwati Devi, Habiba Gurjari, Indrakaur, Kushal Devi, Naamkaur, Raajkaur, Ranviri Valmiki, Seheja Valmiki and Shobha Devi attacked the British army and died while fighting.

Certain features stand out in these various narratives. Many of them claim to be centred around neglected dalit women warriors specifically, whose marginalisation cannot be tolerated by dalits any longer. In all of them, these dalit women are depicted as brave from their very childhood, and the 1857 revolt becomes the turning point which sparks them to accomplish great deeds in the face of high odds. However, the voices of dalit viranganas themselves are usually faint discursive threads, as their stories of adventure and bravery are narrated through a variety of sources – oral, official accounts and dalit male authors. It is these authors who provide narrative coherence, filling in the gaps, and slipping into the present tense to add dramatic flourish and detail to the stories. The past and the present blur and mingle to provide a cohesive narrative of dalit oppression and the bravery of these women against all odds. Many of these dalit viranganas become the symbols of pride for one particular dalit caste. Thus Uda Devi is revered by the pasis particularly, and has emerged as a symbol of Pasi honour, dignity, pride, mobilisation and rights. On the other hand, Jhalkari Bai has been appropriated, eulogised and celebrated by all dalit groups, irrespective of divisions between them, and has become a symbol of unity of all dalits.

Many of them claim to be centred around neglected dalit women warriors specifically, whose marginalisation cannot be tolerated by dalits any longer. In all of them, these dalit women are depicted as brave from their very childhood, and the 1857 revolt becomes the turning point which sparks them to accomplish great deeds in the face of high odds. However, the voices of dalit viranganas themselves are usually faint discursive threads, as their stories of adventure and bravery are narrated through a variety of sources – oral, official accounts and dalit male authors. It is these authors who provide narrative coherence, filling in the gaps, and slipping into the present tense to add dramatic flourish and detail to the stories. The past and the present blur and mingle to provide a cohesive narrative of dalit oppression and the bravery of these women against all odds. Many of these dalit viranganas become the symbols of pride for one particular dalit caste.

Most of these dalit viranganas have Devi or Bai suffixed to their names. They are also projected as highly moral, very “noble”, super brave and super nationalist dalit women. They are emblems of shakti. The written and visual images of these viranganas in the texts itself and on the cover of these pamphlets spectacularise them as usually clad in “masculine” attires, with their bodies all covered up. They are shown to be expert in horse-riding, swimming, bow-arrow and sword fighting. Through such portrayals, dalits hope to garner greater respect, opportunity and dignity to these viranganas, and through them to all dalits. Simultaneously this feeds into conceptions of masculinity. It also covertly challenges notions of dalit female sexuality, and can be seen as a reaction to images of sexually immoral dalit women. By shunning outward expressions of sexuality, dalit women can also hope to build a space where they can wield more control over their bodies and gain dignity and respect within the dominant culture.

Poems and songs occupy a central place in these narratives, which eulogise the viranganas. It is interesting that many of these narrative poems (‘khand kavyas’) have cleverly appropriated the famous poem written by Subhadrakumari Chauhan on Jhansi ki Rani Lakshmibai. Not only are the lines and the words given new meanings and completely reinterpreted, they are also easy to remember. Thus goes one on Jhalkari Bai:

Jhalkari Bai

khub lari jhalkari tu tau, teri ek jawani thi.

dur firangi ko karne mein, veeron mein mardani thi.

har bolon ke much se sun hum teri yeh kahani thi.

rani ki tu saathin banker, jhansi fatah karani thi….

datiya fatak raund firangi, agge barh jhalkari thi.

kali roop bhayankar garjan, mano karak damini thi.

kou firangi aankh uthain, dhar se shish uteri thi.

har bolon ke much se sun ham, roop chandika pani thi.

(Jhalkari you really fought, your youthfulness was unique.

You were a man among the brave in ousting the British.

We heard your story from the mouth of warriors.

You pledged for Jhansi to be victorious by being a friend of the queen.

Jhalkari, you rode from the Datiya gate, trampling the British.

You were like the Kali, and your strike was like lightning.

As soon as a British raised his head, you struck immediately.

We heard your deeds from the warriors, reciting tales of your bravery.)

These songs and poems are often recited in dalit melas and rallies, using dance and musical instruments. Plays too are enacted around them.

The main narrative plots have become more elaborate with time and many stories have been added on, connected to larger purposes of dalit identity. Thus in the Jhalkari Bai story, one episode repeatedly narrated is of Jhalkari being blamed for killing a cow, which had actually been hidden by a brahmin, but the truth is revealed. This story may be linked to challenging dominant colonial and Hindu narratives which have regarded dalits, along with Muslims, as killers of the “holy” cow. Another feature of these writings is that as they have grown, they have become more “sure” in their narrative. Thus for example, the earlier narratives on Jhalkari Bai claim her to be an accomplice of Lakshmibai, who took on her garb to save the rani’s life. We can discern here a tentativeness or uncertainty regarding the role of Rani Lakshmibai in the revolt, where Jhalkari Bai is shown to be an accomplice or at most an equal of Lakshmibai. This has slowly given way to a more sure, authoritative and “mature” dalit history in which Lakshmibai, instead of a model nationalist ruler, appears as a weakling, as reluctant to fight the British, and in fact, is shown as a British supporter and agent. It is stated that Jhalkari Bai was even worried that Lakshmibai might surrender herself to the British as she was very scared of war. Challenging myths and histories surrounding Lakshmibai, it is argued that in reality Lakshmibai not only managed to escape to the forests of Nepal with the help of the ruler of Pratapgarh, she died only in 1915 at the age of 80. It is Jhalkari Bai who is the real martyr and virangana. It is her name that ought to be written in golden letters. She was a dalit woman, with no kingdom, no palace, no expensive jewellery, and no silken clothes. She was neither a queen nor the daughter of a feudal lord, nor the wife of a ‘jagirdar’. She fought selflessly, only for the love of her country, and thus her sacrifice far surpasses anyone else’s.

As a historian, when I started working on these dalit viranganas of 1857, what concerned me was the absence of “hard core”, “written” historical evidence on them in the archives. At one level, I am tempted to argue that anything that mesmerises one is worth cherishing and the magic is ruined by questioning its “authenticity”. Carlo Ginzburg effectively shows how an early manifesto on history “from below” appeared in the form of an “imaginary biography”, where the intention was to salvage through a symbolic character, a multitude of lives crushed by poverty and oppression. The mixture of imaginary biography and historical documents makes it possible even for these dalit histories to leap at a single bound over a threefold obstacle: the lack of evidence, the lack of importance of the subject according to commonly accepted criteria and the absence of stylistic models. A multitude of lives that have been cancelled, destined to count for nothing, find their symbolic redemption in the depiction of immortal characters. But this is not enough. Dalits themselves are keen to prove the historical credibility of their viranganas, and constantly site sources from literary accounts, British narratives, archaeology and oral histories. They claim their works to be “scientific”, “truthful”, “detailed”. As says one:

aithihasik sandarbhon bhitar, ankit sari hai ghatna.

nahin kalpana se kalpit hai – amar humari yeh rachna.

(The whole incident is noted inside historical sources. This immortal story of ours is not a figment of imagination.)

Scattered, often thin, evidence is sited and quoted by dalits repeatedly. Thus on Jhalkari Bai, a constantly quoted source is Vrindavan Lal Varma’s Jhansi ki Rani Lakshmibai. It was published in 1946 after intense personal research and historical reflection, and it mentioned the dusky-complexioned newly wed Jhalkari Dulaiya of the kori caste, who bore a striking resemblance to the Rani. Vishnu Rao Godse, who is said to have been present in the fort when the Rani had fought against General Rose, too had made a reference to Jhalkari in his Marathi book Majha Pravas (My Travels). Similarly on Uda Devi, Amritlal Nagar’s Gadar ke Phool and William Forbes-Mitchell’s Reminiscences of the Great Mutiny are often cited.

And today these stories stand as given, visible truths, with stamps issued in their name, many statues constructed, public rallies and meeting organised, celebrations and festivities conducted, and even colleges and medical institutions formed in their name. Thus, for example, a huge public rally and a mela is organised in Lucknow every year near the statue of Uda Devi at Sikandar Bagh on November 16, the stated day of her martyrdom. With constant evocation, these names have become inscribed in popular dalit memories. Different political parties have repeatedly used these viranganas and made them an integral part of their electoral campaigns and mobilisation strategies, the most successful being the Bahujan Samaj Party, who have used them to build the image of Mayawati particularly.

Are these representations of dalit viranganas historical fictions or fictive histories or something more? How real, exact and truthful in any case are “official”, canonised histories of 1857? Scholars have questioned the possibility of any one authentic history. Histories of dalit viranganas, who are simultaneously dalit and women, stand as persuasive accounts, as histories from below, reaching towards their own “reality”. They take recourse to recorded historical events and intermesh it with subaltern renderings of lost histories, deracinated by mainstream historiography. They are counter-histories of 1857.

Reading Dalit Histories of Viranganas

These popular histories of dalit viranganas are open to simultaneously persuasive, multiple and contradictory readings. There are, of course, limitations of this literature as a historical source. Their representation of dalit women too needs to be questioned. Very few dalit women themselves have penned these popular pamphlets. It is dalit men who are largely engaged in controlling the way images of dalit women are depicted.

While these dalit viranganas are portrayed as “superwomen”, full of bravery, and doing “impossible” acts, these glorifications and celebratory accounts do not extend to all dalit women in general. They offer a filtered vision, viewed through the eyes of the creators of these images. Victimhood is replaced by a new archetype of heroism. Jhalkari Bai is shown as even killing a tiger single-handedly. Although empowering, these images are not necessarily more representative of dalit women. Further, many of these viranganas are physically attractive in their appearance, “classic” beauties, falling into the stereotype of female beauty. Simultaneously, there is an assertion of a super moral dalit female subject perhaps also allowing dalit men to police the behaviour of dalit women in general. Some of these tracts appear didactic in their endorsement of certain patriarchal values. They are often replete with images of the loyal wife and an ideal mother.

Although empowering, these images are not necessarily more representative of dalit women. Further, many of these viranganas are physically attractive in their appearance, “classic” beauties, falling into the stereotype of female beauty. Simultaneously, there is an assertion of a super moral dalit female subject perhaps also allowing dalit men to police the behaviour of dalit women in general. Some of these tracts appear didactic in their endorsement of certain patriarchal values. They are often replete with images of the loyal wife and an ideal mother.