ARCHIVE

Our second extract from Gyan Prakash’s Emergency Chronicles reveals how one of the Emergency’s worst excesses was actually alive and kicking before the Emergency and how the policy behind it was crafted through the lens of a developed world elite.

If yesterday was the anniversary of the bloodcurdling Emergency – that was declared shortly before midnight on the 25th of June, 1975 – then today is the anniversary of its first day. Yesterday we carried an excerpt from Gyan Prakash’s ‘Emergency Chronicles: Indira Gandhi and Democracy’s Turning Point’ that comprised a close look at the “shadow power” that was unleashed before dawn on this date, as well as the atrocities committed by these unbridled dark forces – enabled by flawed laws and systems to become authorities unto themselves – through the length of the Emergency.

Today’s excerpt, from the same book, is a section named ‘The Prehistory of Turkman Gate: Population Control’ from another chapter titled ‘Bodies and Bulldozers’.

The introduction to yesterday’s extract points out how Prakash’s thesis differs from a lot of previous analysis because it tracks the roots of Emergency to various points in India’s postcolonial history. Not to belabour the point – rather, to explain it better – here are lines from the beginning of a chapter called ‘The Fine Balance’:

“Indira Gandhi’s biographers and several accounts of the Emergency draw a sharp contrast and Jawaharlal Nehru, her father and predecessor as India’s prime minister. She did not share, it is said, her father’s deep faith in the liberal values enshrined in the Indian Constitution… The daughter’s failings as a democrat, however, have to be understood in relation to the larger history of postcolonial India. Indira did not concoct the Emergency regime out of ether… Historical forces with roots in the past and implications for the future were at work in the extraordinary turn of events of 1975-77. They signaled a twist in the functioning of the postcolonial state that she had inherited from her father and his associates in the nationalist movement. In this sense, the Emergency was not a momentary episode but a turning point in the history of Indian democracy.”

Often enough, even the most fervently documented periods of history – like the Emergency in India – leave in their wake an incomplete understanding of what happened. This is both because of a lack of nuance, in some cases, as well as, in others, the absence of a bird’s eye view of history. Researchers, in their diligence, sometimes miss the wood for the trees.

For instance, ask Indians today about images that come to mind when you say “Emergency” and many will immediately recall ‘coercive sterilizations’. The coerced population control measures and slum demolitions around Old Delhi’s Turkman Gate and consequent protests and police firing catapulted the structure into the centre of this discourse as a symbol in popular imagination.

But while coercive sterilizations, as well as the zealotry for population control that sought to justify them, may have been exacerbated during the period of Emergency, they actually predated the emergency by quite a few years.

In fact, the following extract shows, even someone like Asoka Mehta, who faced the brunt of the Emergency and thundered against its oppression was, before the Emergency, a vociferous proponent of coercive population control. As Planning Minister, he had said about population control that it was “the enemy at the gate… It is war we have to wage, and as in all wars, we cannot be choosy, some will get hurt, something will go wrong. What is needed is the will to wage the war so as to win it.” Also, about coercive campaigns, that they possess “an element of inhumanity.” But, “here we have to wield the surgeon’s knife. It may hurt a little, at a point, for a while, but it will help to impart health.”

In the following excerpt, Prakash pursues the obsession with birth control and family planning back in time to uncover its roots, abroad, in the late 1700s, and in the 1930s in India. But things become really interesting in the 1940s and 50s, when America and the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations make their entry. By the mid-1960s the Ford Foundation in India was “the largest foreign foundation presence anywhere in the world” and a staff member of the Population Council (founded by John D. Rockefeller) notes that the Indian “government does whatever the Ford Foundation says it should do in Family Planning.”

It is rare to find such meticulous documentation of policy history, full of rigorously researched details which make this extract an eye-opening read. It reveals the influencing, if not actual formulation, of developing world policy through the lens of a developed world elite. Post World War II, the work of demographers like Frank Notestein and Kingsley Davis goaded powerful international bodies (dominated by developed countries) to focus population control efforts on developing countries like India and Pakistan. Was this influenced by racist opinions (the “rising tide of colour”; “the yellow peril”)? The extract, while drawing our attention to these prevalent views, doesn’t establish causation, even as the question lingers.

An interim report sent by the Ford Foundation to the Indian government in 1970 – the year that its Delhi chief, Douglas Ensminger, left after a nearly two decade tenure – speculated on employing compulsory sterilizations, taxation and property laws to achieve targets, saying, “While some of these measures may seem harsh or punitive, the magnitude of the task ahead, the crucial role that population plays in the entire developmental scheme and the urgency of the problem may well warrant action along these lines.”

And what of the Indian elite? They fell in line. “Even without being explicitly intended,” writes Prakash, “Coercion was inherent in a program designed by international and Indian elites and directed at the poor. This was the poisoned fruit of the nature of the regime that came to power in 1947. Instead of enacting and implementing radical land reforms and promoting the overall health and education of subordinate groups by empowering them with resources, the postcolonial elite chose state-directed modernization.”

“The concern was that the poorest and the least capable would soon outnumber the fittest and the best,” Prakash writes while underscoring the subtext of the global elite’s mid-twentieth century gaze towards African and Asian nations. This seems to have held true for the gaze of much of the Indian elite – towards its own country’s poor – as well.

Undoubtedly, Sanjay’s aggressive advocacy of population control and slum clearance for “urban beautification” drove them into high gear. But not only did these programs predate the Emergency but so did the deployment of coercion. Let us turn first to population control.

As Mathew Connelly has shown, the objective to limit family size in India not only went back decades before the Emergency but actually originated as a global project. Thomas Malthus fired the opening shot with the publication of his Essay on the Principle of Population in 1798. It laid out an apocalyptic future in which population growth would outstrip food supply, with only famines and wars acting to maintain the balance. When Asians and Africans also began to live longer and grow in numbers in the twentieth century, European and North American elites began to worry about “the rising tide of color” and the impending “yellow peril.” The concern was that the poorest and the least capable would soon outnumber the fittest and the best.

The late-nineteenth-century development of the science of demography gave concrete shape to these worries. Legible in numbers, people became “population,” which had to be managed. Connelly advisedly uses “population control” rather than “family planning” to describe this project. The “term family planning, in the sense of promoting reproductive rights, means the opposite of population control.” Instead of rights, nutrition, and overall well-being of the family, it means a narrower set of policies and programs aimed at achieving and manipulating population growth targets. Sharing these objectives, a movement developed out of the activities of the eugenicists, Malthusians, pro-natalists, and birth control and public health advocates, who pushed for population control with a diversity of motives.

Undoubtedly, Sanjay’s aggressive advocacy of population control and slum clearance for “urban beautification” drove them into high gear. But not only did these programs predate the Emergency but so did the deployment of coercion.

Beginning with a concern about the growth of the human species outstripping natural resources, the population control movement took on a planetary perspective. It made the biological process of reproduction a branch of history, subject to human control on a world scale. Even concerns within nation-states about immigration and its effect on the social composition of the citizenry drew on the differential racial growth of the world population. Government leaders, scientists, and population control activists “thought globally” in pressing for new reproductive norms and devising campaigns to control population.

An indefatigable campaigner for global population control was Margaret Sanger. The founder of the American Birth Control League, the precursor of Planned Parenthood, Sanger famously traveled to Wardha to meet Mahatma Gandhi to convince him of the value of birth control. While Gandhi shared the goal of limiting births, he steadfastly stuck to his idea that sex without reproduction was sin. For him, only abstinence, not birth control, was the approved method to limit procreation. Undaunted, Sanger pressed on with her efforts to establish birth control clinics in the country in the 1930s.

Like their international counterparts, Indian elites became concerned about population growth. While one Brahman advocate of Sanger’s birth control mission argued, unsupported by data, that lower castes and Muslims procreated at a higher rate, another called for either voluntary or coercive sterilization. Gyan Chand, a professor of economics in Patna University, published India’s Teeming Millions in 1939, followed five years later by The Problem of Population, arguing that reducing the birth rate was crucial for reducing poverty and misery. Radhakamal Mukherjee, a professor of economics and sociology at Lucknow University, was another key figure in setting the tone for the population discourse in the nationalist economic policy community. He founded the Indian Population Conference in 1936 and wrote Food Planning for 400 Millions in 1938, which recommended that population growth be brought in line with national production. Mukherjee went on to head the subcommittee on population of the Congress party’s National Planning Committee.

In a report in 1940, the planning committee warned that the “disparity in the natural increase of different social strata shows a distinct trend of mispopulation.” It cautioned that the greater likelihood of upper classes and advanced castes practicing contraception was leading to the “gradual predominance of inferior social strata.” The report urged the removal of barriers to intermarriage among upper castes and the dissemination of birth control propaganda among the masses to avert “deterioration of the racial makeup.” Nehru, who chaired the committee, endorsed population control while also recommending other measures such as improved nutrition so that the poor would cease using a high birth rate to hedge against high infant mortality. The National Planning Committee finally recommended broad economic development as a national goal as well as reducing population pressure.

In a report in 1940, the Congress party’s National Planning Committee warned that the “disparity in the natural increase of different social strata shows a distinct trend of mispopulation.” It cautioned that the greater likelihood of upper classes and advanced castes practicing contraception was leading to the “gradual predominance of inferior social strata.” The report urged the removal of barriers to intermarriage among upper castes and the dissemination of birth control propaganda among the masses to avert “deterioration of the racial makeup.”

The Indian elite discourse on population was in line with the global project that made rapid strides after World War II. With the world population growing in spite of the devastating war, researchers invoked the “demographic transition” theory to advance policies to limit the birth rate globally. A leading figure in formalizing and globalizing the idea of demographic transition was Frank Notestein, who founded the Office of Population Research at Princeton University in 1936 to offer graduate training in demography. Building on his study of Europe and the Soviet Union, he offered the demographic transition as a theory to explain and manage the rising population in the developing world. According to him, societies moved from high to low birth and death rates in discrete stages, which correlated to successive phases of modernization. Applying this theory, the Office of Population Research under Notestein internationalized demography, initiating studies of the world population, and sponsored Kingsley Davis’s influential The Population of India and Pakistan (1951), which proposed control over reproduction as the critical battleground against poverty.

For population and development activists, frequently one and the same, the mantra was modernization, and the small family was its embodiment and instrument. Notestein was at the center of this activism. Partly because of his advocacy, the United Nations established its Population Division in 1946, with Notestein as its first director. UN agencies like the Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organization became eager partners as UN officials saw population policy as a step toward the global governance of population. An international population policy establishment rapidly took shape after 1952 with the founding of the Population Council by John D. Rockefeller. The council brought together the International Planned Parenthood Foundation (IPPF), the Ford and Rockefeller foundations, and pharmaceutical companies, becoming a network for the major actors in the field.

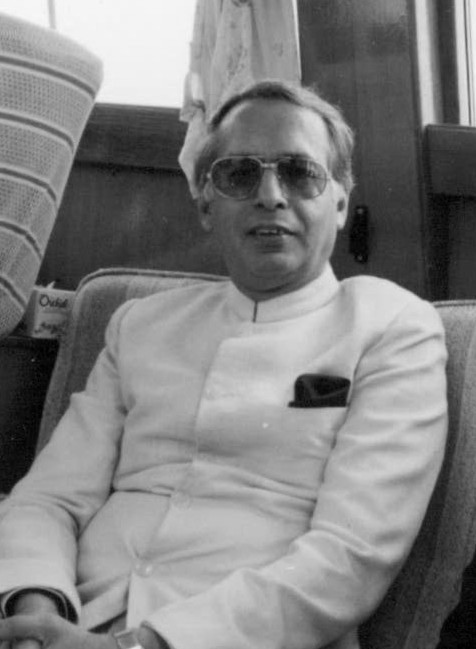

Douglas Ensminger

India was the most important country for population activists, and the key driver of the project was the Ford Foundation under its Delhi chief, Douglas Ensminger. The foundation’s promotion of modernization was part of the anti-communist U.S. agenda against the Soviet Union, but Ensminger skillfully delinked Ford India from Cold War geopolitics and positioned it as India’s partner in a broad strategy of development. The agreement establishing Ford’s India field office at Nehru’s invitation stated that the foundation would assist in initiating programs deemed urgent by the Indian government but delayed by routine budgetary procedures. Additionally, Ford would provide the resources required to test methods of development for which the government could not readily release funds. This agreement aligned Ford with Indian government programs, projecting the foundation only as a source of technical advice and financial assistance for projects initiated and run by Indians.

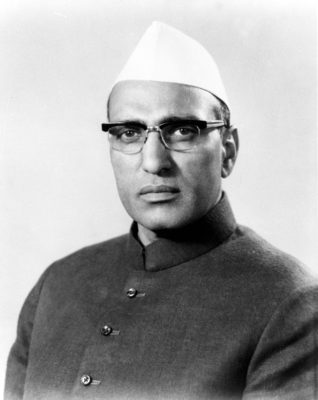

Rajkumari Amrit Kaur

Population control, which was already part of India’s First Five-Year Plan, was high on Ensminger’s list of priorities. Accordingly, he approached Nehru, who needed no convincing about the need for restraining population growth. But he expressed his government’s inability to act without Health Minister Rajkumari Amrit Kaur getting on board. Kaur was a leader of some stature. Belonging to a Punjabi royal family, she had gone to school in England, had graduated from Oxford, and became an activist in the nationalist struggle and Gandhi’s follower on her return to India. After Independence, she was one of two Christians, and the only woman, inducted into Nehru’s first cabinet. As a Gandhian, she was prickly about sex unmotivated by procreation implied by the birth control program.

India was the most important country for population activists, and the key driver of the project was the Ford Foundation under its Delhi chief, Douglas Ensminger… he approached Nehru, who needed no convincing about the need for restraining population growth. But he expressed his government’s inability to act without Health Minister Rajkumari Amrit Kaur getting on board. Kaur was a leader of some stature. Belonging to a Punjabi royal family, she had gone to school in England, had graduated from Oxford, and became an activist in the nationalist struggle and Gandhi’s follower on her return to India. After Independence, she was one of two Christians, and the only woman, inducted into Nehru’s first cabinet. As a Gandhian, she was prickly about sex unmotivated by procreation implied by the birth control program.

Undeterred, Ensminger set to work. In March 1955, he sought an appointment with her and began the meeting by saying that while he wanted to talk about family planning, he would not if she so wished. Disarmed, she asked him to present his views. Finding his opening, Ensminger went on to speak about the relationship between population growth and mass poverty and that it was their duty to help all those who sought help in limiting their families. After an hour of their exchange, Kaur asked if he could arrange for experts who could help her think through the issue and formulate policies. Ensminger was prepared. Planning ahead, he had already obtained a promise from John D. Rockefeller III in New York to personally pay for two consultants to come to India so that they did not appear to be representing either the Ford or Rockefeller Foundation but were simply experts in the field. So, when Kaur asked for expert advice, Ensminger readily agreed, knowing he could deliver. Accordingly, Leona Baumgartner, the head of New York Public Health Services, and Frank Notestein of Princeton University visited Delhi and helped formulate the health minister’s first policy statement on population control.

The report submitted by Baumgartner and Notestein to Health Minister Kaur encouraged the government to boost its family planning efforts with sustained research and field trials to gain knowledge on different contraceptive methods, cultural preferences, and demographic patterns. Its most important recommendation was the establishment of a semiautonomous family planning body within the Health Ministry to formulate policies and coordinate their implementation. The government heeded the advice and established the Central Family Planning Board in 1956, with Colonel B. N. Raina of the Army Medical Corps at its head. Population control also received high priority in the Second Five-Year Plan, which commenced in 1956. It allocated a budget of nearly 50 million rupees to the new board and created advisory boards at the center and in the states. The vigorous push for population control included devising a flexible system of financial assistance to the states and a call for establishing family planning clinics nationwide, offering contraceptive services. Ford made its first major grant of $300,000 in 1959 to the Health Ministry and went on to provide substantial financial assistance in subsequent years to pay for training Indian personnel, research, pilot projects, fellowships, consultants, drugs, and equipment and supplies. The Third Five-Year Plan (1961–66) ramped up the family planning budget to 270 million rupees, over five times the Second Plan’s allocation. Ford proposed assistance of $12 million, though its board eventually approved only $5 million, which was still a substantial increase in its commitment. This was to fund a number of new programs, institutions, consultants, and training schemes.

By the mid-1960s, Ford was burrowed so deep into the Indian government’s family planning programs that a Population Council staff member noted in 1965 that he had encountered several Indians who contend that the “government does whatever the Ford Foundation says it should do in Family Planning.” With 72 expatriate professionals, 177 Indian technical and administrative staff, 63 assorted full-time employees, and 16 foreign individuals in various institutions supported with funds, Ensminger developed Ford in India as the largest foreign foundation presence anywhere in the world. It provided the ideas and funds for many of the government family planning programs and organizations, its consultants were planted in the Health Ministry, and the foundation arranged for family planning officials to visit New York. It vigorously promoted and assisted the distribution of the intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD or the loop) and mass marketing of the low-priced condom Nirodh (protection). With a strong belief in communications, Ford also employed a consultant who devised an advertising program using a female elephant. She was named Lal Tikon, or the Red Triangle, the symbol of family planning. She would go from village to village, distributing leaflets with her trunk with information on family planning and condoms. On one side she sported a colorful image of the Red Triangle and a happy couple with the words (in Hindi): “You don’t need another child now—Don’t ever have another after three.” On the other side was another Red Triangle with the words: “My name is Red Triangle—My job is spreading happiness.”

It was one thing to advertise and educate but quite another to get people to come to the clinic and take advantage of the contraceptives being offered. Recognizing the problem, the Third Plan had shifted to an “extension approach” that called for the population control program to seek out people rather than wait for them to come to clinics. As the head of the Family Planning Board, it was up to Colonel Raina to lead the new effort. Associated with the population control movement since 1937, he brought optimism and energy to his position, a quality that Ford officials appreciated; some in the Population Council, however, worried that the colonel cared more for jeeps, equipment, and dollars for the program than “real research.”

By the mid-1960s, Ford was burrowed so deep into the Indian government’s family planning programs that a Population Council staff member noted in 1965 that he had encountered several Indians who contend that the “government does whatever the Ford Foundation says it should do in Family Planning.” With 72 expatriate professionals, 177 Indian technical and administrative staff, 63 assorted full-time employees, and 16 foreign individuals in various institutions supported with funds, Ensminger developed Ford in India as the largest foreign foundation presence anywhere in the world. It provided the ideas and funds for many of the government family planning programs and organizations, its consultants were planted in the Health Ministry, and the foundation arranged for family planning officials to visit New York. It vigorously promoted and assisted the distribution of the intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD or the loop) and mass marketing of the low-priced condom Nirodh (protection).

A man of action, Colonel Raina directed every village and town to form a family planning committee and arranged for “natural group leaders” to be paid an honorarium of a thousand rupees to develop a “small family norm” among their communities. Furthermore, mobile vasectomy camps, anticipating the practices during the Emergency, appeared in Maharashtra, which was held up as an example for other states. Sterilizing men rather than women was the preferred option because a surgeon could carry out the operation within fifteen minutes under local anesthesia. The camps were organized in a carnival-like atmosphere to build group pressure. Heartened by the 172,000 sterilizations performed in 1962, 70 percent of them on men, the Ministry of Health began encouraging the use of mobile vans as a more effective way to reach and sterilize patients institutionalized for tuberculosis, leprosy, and mental illness. By 1965, Colonel Raina was writing an enthusiastic report to John D. Rockefeller III, the chair of the Population Council in New York, about the successes of the government’s family planning program. Rockefeller was taken aback, for he had not asked for a report, nor did he know the colonel, but Raina was fervent about his mission and knew who the international players were.

By 1965, Colonel Raina was writing an enthusiastic report to John D. Rockefeller III, the chair of the Population Council in New York, about the successes of the government’s family planning program. Rockefeller was taken aback, for he had not asked for a report, nor did he know the colonel, but Raina was fervent about his mission and knew who the international players were.

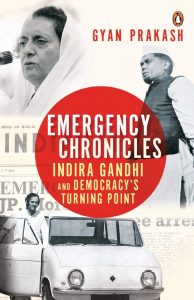

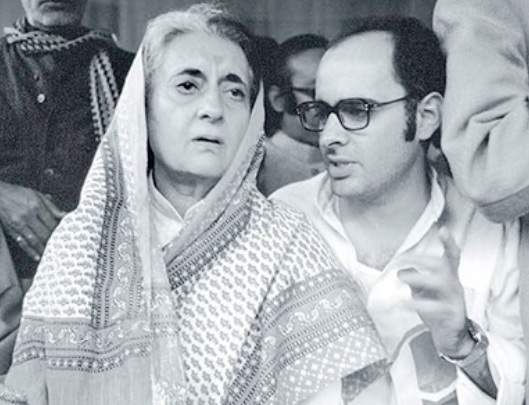

Indira Gandhi and Lyndon Baines Johnson

The American proponents of population control found a sympathetic ear in Indira Gandhi. Her family’s ancestral home in Allahabad, Anand Bhawan, came to house a family planning institute. When she was information and broadcasting minister in the Lal Bahadur Shastri government, she pushed for a program to distribute transistor radios in the countryside to broadcast the family planning message. She also pressed her health minister, Sushila Nayar, to adopt the policy of offering financial incentives to women for IUD insertions. When she took over as prime minister in 1966, the Ministry of Health was renamed the Ministry of Health and Family Planning, with a separate department, a secretary, and a minister of state. During her visit to the United States, population control came up in her discussions with President Lyndon Johnson over food aid. Although no record exists of their conversations, Johnson reported that the Indian government had agreed that food and population problems were intertwined. Soon after she returned from Washington, Indira accepted a report from a committee recommending policies to reverse a decline in IUD insertions. Clearly the Americans had used foreign aid as leverage in pressing population control.

For international population control zealots, India’s failure to drastically cut its birth rate was a cause for panic. Paul Ehrlich set the anxious tone in his 1968 international best seller, Population Bomb:

I have understood the population explosion intellectually for a long time. I came to understand it emotionally one stinking hot night in Delhi a couple of years ago… The streets seemed alive with people. People eating, people washing, people sleeping. People visiting, arguing and screaming. People thrusting their hands through the taxi window, begging. People defecating and urinating. People clinging to buses. People herding animals. People, people, people, people.

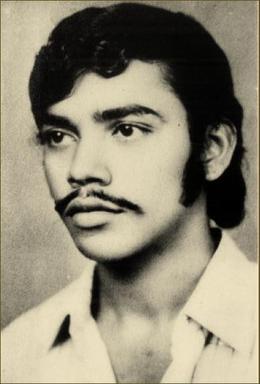

Asoka Mehta

If Ehrlich sounded the ticking time bomb theory, Indian officials were adopting the metaphor of war in approaching population control. Planning Minister Asoka Mehta, who was later imprisoned during the Emergency and would rail against Indira’s tyranny, could not be clearer about the war at hand and what it required. Population growth is “the enemy at the gate. . . . It is war we have to wage, and as in all wars, we cannot be choosy, some will get hurt, something will go wrong. What is needed is the will to wage the war so as to win it.” He teamed up with other ministerial colleagues in the cabinet to sideline Sushila Nayar, who was clearly not an enthusiastic population warrior. Indira replaced her in 1967 with the demographer Sripati Chandrasekhar, who wished to make sterilization compulsory for every man with more than three children. The cabinet did not go along with this recommendation, but his proposal signaled the direction in which the wind of population control was blowing.

In 1966, New Delhi formally accepted as policy what the Population Council, IPPF, the Ford Foundation, and the World Bank had been recommending: financial incentives for sterilization and IUD insertions. Every state was to be provided with 11 rupees for every IUD insertion, thirty rupees for every vasectomy, and forty for a tubectomy (later increased to ninety rupees), from which they could allocate whatever they deemed fit to individuals, staff, and “motivators.” The number of sterilizations and IUD insertions spiked. Bihar, which had previously had the lowest number of per capita sterilizations and had met only 12 percent of its target for IUD insertions, saw 100,000 people come forward in 1966–67. The next year, the figure jumped to 200,000, with an overwhelming majority opting for sterilization that offered a higher payment. The key factor was the Bihar Famine of 1966–67, which drove the poor to sterilization camps. It was the same story in Madhya Pradesh where the number of people who opted for sterilization jumped from 130,000 in 1966–67 to 230,000 the following year, which was the third year of continuous drought. The experiences in Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Orissa were the same. The UP administration directed the family planning officials to report directly to district magistrates, who were pressured to ensure that the staff met targets.

Several states that were not stricken by drought also pursued coercive campaigns. Kerala and Mysore began barring maternity leave to government employees with three or more children; Maharashtra proposed denying medical treatment and maternity benefits to families who had three or more children and recommended making sterilization mandatory for them. Haryana and UP expressed their intent to adopt similar policies. Asoka Mehta acknowledged that such measures had “an element of inhumanity.” But, he continued, “here we have to wield the surgeon’s knife. It may hurt a little, at a point, for a while, but it will help to impart health.”

Planning Minister Asoka Mehta, who was later imprisoned during the Emergency and would rail against Indira’s tyranny, could not be clearer about the war at hand and what it required. Population growth is “the enemy at the gate. . . . It is war we have to wage, and as in all wars, we cannot be choosy, some will get hurt, something will go wrong. What is needed is the will to wage the war so as to win it.” … Kerala and Mysore began barring maternity leave to government employees with three or more children; Maharashtra proposed denying medical treatment and maternity benefits to families who had three or more children and recommended making sterilization mandatory for them. Haryana and UP expressed their intent to adopt similar policies. Asoka Mehta acknowledged that such measures had “an element of inhumanity.” But, he continued, “here we have to wield the surgeon’s knife. It may hurt a little, at a point, for a while, but it will help to impart health.”

In spite of financial incentives and disincentives, sterilizations and IUD insertions were beginning to decline by 1969. Ensminger, who was to leave New Delhi in 1970 after a successful nineteen-year tenure of promoting Ford programs, among which population control occupied a central place, was worried about the overall state of its progress. He wrote to the health minister in July 1969, forwarding a consultant’s report on strengthening the government’s program on family planning. It stressed enhanced training of the family planning staff and the use of incentives as motivation. An interim Ford report a year later rang the population alarm bells loudly, warning that a whopping addition of 130 million projected for the decade to the already existing 540 million would crush the economy. The government effort was laudable but unequal to the task. The report concluded by speculating on the use of compulsory sterilizations, as well as the use of taxation and property regulations to achieve targets: “While some of these measures may seem harsh or punitive, the magnitude of the task ahead, the crucial role that population plays in the entire developmental scheme and the urgency of the problem may well warrant action along these lines.”

In fact, this was where India’s population control policies were headed starting in 1971. It started holding vasectomy camps consisting of mobile field hospitals, which were preceded by sustained propaganda. The number of male sterilizations spiked from 1.3 million in 1970–71 to 3.1 million in 1972–73. Behind the achievement of these impressive numbers was the allocation of targets and the lead taken by district authorities to mobilize the subordinate bureaucracy and the health staff in mobile camps.

Marika Vicziany has shown that the Emergency did not invent coercion. Force was inherent in the pre-Emergency use of financial incentives and disincentives, the employment of motivators, and the mobilization of district officers. Contrary to the “myth” that India was a “soft state” that relied on voluntarism for population control, she shows that the program was coercive. People agreed to accept IUD insertions and undergo sterilizations for money, not out of free will. This was evident in the fact that poor and lower castes constituted the majority of those who underwent these operations for payment. They went under the knife simply for the money, particularly when faced with destitution during times of drought and famine. Consider also the deeply unequal power relations marshaled for the program. The “community leaders” recruited as motivators were men of influence; they were often local magnates whose “persuasive” power the poor could scarcely be expected to resist. Nor could they have easily defied the state machinery, which the poor routinely experienced as distant and overbearing. The intimidating sight of the district magistrate arriving with mobile vans and health workers in the villages and small towns could not but have wilted the free will of the underprivileged.

Marika Vicziany has shown that the Emergency did not invent coercion. Force was inherent in the pre-Emergency use of financial incentives and disincentives, the employment of motivators, and the mobilization of district officers. Contrary to the “myth” that India was a “soft state” that relied on voluntarism for population control, she shows that the program was coercive.

Even without being explicitly intended, coercion was inherent in a program designed by international and Indian elites and directed at the poor. This was the poisoned fruit of the nature of the regime that came to power in 1947. Instead of enacting and implementing radical land reforms and promoting the overall health and education of subordinate groups by empowering them with resources, the postcolonial elite chose state-directed modernization. Along with industrial growth and the Green Revolution, population control was an outcome of this strategy of change from above. Indian elites believed in it, and they were encouraged and prodded by the Ford and Rockefeller foundations, IPPF, and transnational experts. Together, they exuded the prevalent high-modernist confidence in the social engineering of humanity with scientific data and methods. Such a lens impelled the postcolonial regime to decide that control over reproduction was “a critical battleground in the war against poverty, in which sterilization, pills, and IUDs could be used as weapons.”

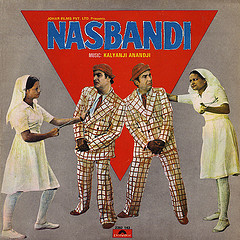

Nasbandi, a film by I. S. Johar, made during Emergency but released only after it was lifted, in 1978.

Even without being explicitly intended, coercion was inherent in a program designed by international and Indian elites and directed at the poor. This was the poisoned fruit of the nature of the regime that came to power in 1947. Instead of enacting and implementing radical land reforms and promoting the overall health and education of subordinate groups by empowering them with resources, the postcolonial elite chose state-directed modernization.

Thus, even when the 1973 oil crisis tightened the budget allocation for family planning and led to a nationwide reduction in the number of sterilizations, Health Minister Karan Singh remained undaunted. He announced that the government would redouble its efforts and increase payments to those who underwent tubectomies or vasectomies. He struck a different note at the 1974 Bucharest World Population Conference where he memorably declared, “The best contraceptive was development.” But it was empty rhetoric. It did not mean any retreat from aggressive population control to tackle poverty. In April 1975, the Central Family Planning Council passed a resolution that proposed to revitalize the sterilization program with higher financial incentives. The failure in the strategy to fight poverty with population control did not give the government pause but drove it to reinvigorate the sterilization drive. The stage was set for the program to ratchet up its built-in coercive nature by several notches.

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of Gyan Prakash and Penguin Random House India. You can buy Emergency Chronicles: Indira Gandhi and Democracy’s Turning Point here.

ARCHIVE

An excerpt from Gyan Prakash’s Emergency Chronicles: Indira Gandhi and Democracy’s Turning Point that will make you shudder, remember and, most importantly, understand what one of Indian democracy’s darkest chapters felt like, and how it came to pass. And why we must never allow it to come to pass again.

It is important to remember the night of June 25th, 1975, when – as Gyan Prakash writes in the introduction to the chapter ‘Lawful Suspension of Law’ in his ‘Emergency Chronicles: Indira Gandhi and Democracy’s Turning Point’ – President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed signed a draft Emergency proclamation and then “swallowed a tranquilizer and went to bed”.

We have republished a section called ‘Shadow Power’ from the same chapter because – even as that day, 45 years hence, passes by, and before the night arrives – it is important to remember the hundreds, then thousands, then well over hundred thousand arrests, the clampdown on and ignominious defeat of a free press – both by direct action and chilling effect – and the arbitrariness with which the shadowy figures of the night-state (for what else should one call this) were appointed and operated. It is equally important to remember the victims of this night-state, and the horrors they experienced. The mother of a JNU student – “lifted” from campus without a warrant – pushed to a nervous break-down. The brother of a socialist leader, tortured, then denied medical care. A woman “whisked off” upon arrival at the airport, with her eight year old child. This is just the tip of the iceberg. More students tortured, killed. More parents left distraught, without information of their children’s whereabouts. More dissent quelled, even as the comedy of horrors laid out by the government by way of propaganda regressed from the banal to the ridiculous. Many of us know all this. But we must try to relive it – the horror and the grief – else those small but significant acts of defiance, of those whose heads were held high above this darkness, will mean nothing.

But there is another reason we must remember. “After all,” writes Prakash in his prologue to the book. “Indira Gandhi and her distortion of the political system did not fall out of the sky, however much the remembrance of the trauma of the Emergency persuades us to believe it is so.” “Prakash argues… ” writes political scientist Ben Margulies in his review of ‘Emergency Chronicles’. “That the Emergency was not a departure from Indian norms, but rather an intensification of authoritarian practices New Delhi had employed from independence.”

“The operation of the political will… did not mean lawlessness because the constitution provided for the declaration of emergency,” Prakash writes. “The regime used a combination of existing laws on preventive detention, decrees and constitutional amendments passed by the Parliament to dress its rules in a legal disguise.” The following excerpt outlines how recommendations for police reforms from as early on as 1902, and by so many committees in the post-colonial era, have remained on paper enabling a deep state to act with varying degrees of impunity at various times, often in service of their political masters, often serving themselves.

It is interesting to note that the anniversary of the Emergency comes close on the heels of the anniversary of the Battle of Plassey (on which Sudeep Chakravarti – whose insights you can read here – has written a book recently). One event set in motion a series of consequences that saw our freedoms being held in a stranglehold by powers from afar. The other saw the suspension of our freedoms courtesy the powers within.

While Prakash holds Indira Gandhi squarely responsible for the abhorrence that was the Emergency, he traces – in his epilogue – the enablement of this terror way back to constituent assembly debates: “For all his concerns about inequality, Ambedkar was also worried about the danger posed by the ‘grammar of anarchy’ (you can read an excerpt of Ambedkar’s speech, being referred to, here) of popular politics. Additionally, the postwar turmoil and the violence of Partition drove lawmakers to craft a powerful state that would secure national unity. They set aside the criticisms of emergency powers and the removal of due process and restrictions on rights to freedom.”

Margulies writes, “Consequently, India’s ruling elites embedded sweeping emergency provisions in the Indian constitution (adopted in 1950), while working to strengthen the central government and limit restrictions on its executive power.”

Our obsession with a “powerful” or ‘strong’ “central government” persists. This manifests itself not just in the sword of an Emergency 2.0 hanging over our heads but, equally, in the laws of preventive detention we see in force around us. While writing about an “afterlife” of the Emergency, Prakash notes how “the short-lived Charan Singh government brought back preventive detention in spite of the Janata Party’s rhetoric about fully undoing the emergency”.

The afterlife continues. And as one reads in the following excerpt about the state excesses that MISA enabled during the Emergency, can one truly ignore the excesses that the UAPA is enabling today?

‘SHADOW POWER’

The suspension of law released a spectral force of power that was a gift from heaven for someone like Bansi Lal, the Haryana chief minister and Sanjay’s hatchet man. An ambitious man of action, he was not wont to let the law and official rules of conduct stand in the way when it came to outdoing his master’s bidding. Since June 12, the chief minister had been directing government officers in his state to round up people and send them to Delhi for rallies in support of Indira. On the afternoon of June 25, he asked his principal secretary to tell the police to prepare a list of people “prejudicial to the state.” Around 10 p.m., the principal secretary was summoned to the chief minister’s residence, where he handed over the list. Soon, he was in Bansi Lal’s bedroom. The chief minister was sitting on the bed, reading out names on the list to another minister, who was concurring and also suggesting fresh names. The principal secretary and another senior officer in the bedroom stood as silent spectators.

Bansi Lal already enjoyed authority as a chief minister, but his power grew exponentially on June 25. He had been present that afternoon at a meeting called by Dhawan in his office at the PM’s residence. Om Mehta, the minister of state for Home, and Krishan Chand, the former Indian Civil Service officer whom Sanjay had anointed as Delhi’s lieutenant governor, were in attendance. Also present was K. S. Bajwa, the Delhi SP (Crime Investigation Department) (Special Branch), a thirty- seven-year-old intelligence officer tasked with compiling a list of possible detainees. The discussion concluded with directions to carry out arrests in the night, before the president had even signed the Emergency proclamation.

Bansi Lal

While Bansi Lal returned to Haryana to gleefully implement the order, the LG assembled his senior administrative and police officials at his residence late on the evening of June 25. In attendance, among others, was Navin Chawla, the lieutenant governor’s London School of Economics–educated secretary and Sanjay’s friend. Also present was Bhinder, the forty-year-old Sikh police officer who had an uncanny instinct to be present at all such occasions. He was already privy to arrest plans, having been present a day earlier in the discussion of impending arrests with Dhawan and Sanjay at the PM’s residence. LG Krishan Chand opened the meeting by informing the assembled officials that the president was going to declare an Emergency and that they should prepare for arrests. District Magistrate Sushil Kumar protested that there was not enough time to prepare the MISA detention orders and suggested using the ordinary provisions of criminal law instead. But another officer objected to this suggestion, pointing out the absurdity of detaining respected national leaders under criminal law. The LG overruled all objections and directed them to carry out arrests under MISA using the list supplied by the Delhi police officer Bajwa, who was also in attendance. Bajwa then returned to his office, prepared a list of 159 targets for arrest, including 17 top national leaders, and handed it to Bhinder.

On the afternoon of June 25, he (Chief Minister Bansi Lal) asked his principal secretary to tell the police to prepare a list of people “prejudicial to the state.” Around 10 p.m., the principal secretary was summoned to the chief minister’s residence, where he handed over the list. Soon, he was in Bansi Lal’s bedroom. The chief minister was sitting on the bed, reading out names on the list to another minister, who was concurring and also suggesting fresh names.

DM Kumar had his orders, but issuing so many MISA warrants within a short time was a problem. Dhawan kept phoning him to ask for progress reports. Finally, he went to the PM’s residence to explain the problem to Dhawan. It was to no avail. Left with no option, he assembled his subordinate officers, including ADM Ghosh, handed them the lists supplied by Bajwa, and directed them to make arrests under MISA. The task of typing out individual warrants was so time-consuming that Kumar asked Ghosh to go to the Tees Hazari Court and cyclostyle five hundred copies of blank MISA orders. Ghosh did as directed, but the task took a long time because there was only one machine in working order. Finally, when the job was done, he took the forms to Kumar, who asked him to fill in the names and addresses from Bajwa’s list. Some were left blank to be filled in later with the details of persons arrested. Then Ghosh went to the residence of the SP (South), who organized the raids in his area. The officers conducting the raids were instructed not to investigate the genuineness of charges. The same procedure was followed in other police districts of Delhi.

Writers have described many of these details to highlight the inauguration of the Emergency’s tyranny. I recount them to draw attention to the shadowy power unchained in the darkness before dawn. It was almost lawful but not quite. MISA warrants were used but on cyclostyled forms. Lawful agents of the state conducted the raids and made arrests but the underlying legality of their actions was suspect. Pulling the strings was Sanjay, who occupied no official position but drew his force from the reflected power of Indira. He relied on Indira’s personal assistant and his cronies Dhawan, Bansi Lal, and Om Mehta—all of whom exceeded their official authority. The enforcers were Bajwa, Chawla, and Bhinder. Young and action-oriented, they were dubbed by critics as Sanjay’s crude and ruthless upstarts who had displaced his mother’s suave and talented Kashmiri advisors, willing to ride roughshod over senior leaders and bureaucrats. The suspension of law gave them license to play fast and loose with the rules. Disobeying them ran the risk of retaliation that no one could challenge because the source of their power was shrouded in the enigma of the “PM’s House.”

Delhi’s chief secretary dared to bring to the LG’s notice the questions raised by the law secretary on the legality of grounds for detention in certain cases. LG Chand exploded, saying that it was “legal pettifogging.” When his secretary Chawla heard about the objection raised by the law secretary, his senior by several years and rank, he first chewed him out and then informed him that he had saved him with great difficulty: “I thanked him for the kind turn done to me and saving me from disgraceful exit at the fag end of my career. I left his room a sad man.” Another officer, who arrested only 60 out of the 136 detention requests, found himself transferred. Chawla told ADM Ghosh, a stickler for rules and procedures, that if the grounds for arrest were deficient, “we should fabricate such grounds as might be felt sufficient.” When the magistrate returned several detention orders, Chawla summoned him and threatened both him and his wife, who was also an IAS officer: “The penalty for not cooperating with the Administration in the matter of MISA orders will not be the usual ones like transfer to Andamans, etc. If I know the mind of the present LG, I can say categorically that he will not have the slightest hesitation in putting even senior IAS officers behind the bars under MISA.” Navin Chawla was to deny this later and called ADM Ghosh a liar. But ADM Ghosh, who had been Chawla’s classmate in the IAS, did not want to take chances. He started issuing detention orders as asked by the end of July.

The task of typing out individual warrants was so time-consuming that Kumar asked Ghosh to go to the Tees Hazari Court and cyclostyle five hundred copies of blank MISA orders. Ghosh did as directed, but the task took a long time because there was only one machine in working order. Finally, when the job was done, he took the forms to Kumar, who asked him to fill in the names and addresses from Bajwa’s list. Some were left blank to be filled in later with the details of persons arrested.

Bajwa generated the list of suspects to be detained and distributed them unsigned to police officers to execute arrests. This was troubling to some in a bureaucracy that was trained to act on written instructions both as a matter of official record and as protection from charges of unlawful conduct. One officer initially took to making a secret note of the detention request to protect himself from possible prosecution later: “Most of us thought that within a day or two the magistracy and the police will be called upon to explain the propriety of these arrests. However, subsequent events belied our apprehension.” As time went on, SP Bajwa began phoning in the list. Some resisted but were pushed back into line. They continued making arrests based on the list furnished by Bajwa, who supplied the grounds some days later. People released on bail by courts were immediately re-arrested.

Second to none in orchestrating and carrying out arrests was Bhinder. On July 11, he wrote to Prakash Singh, SP (North), supplying him with a list of teachers and students at Delhi University who were likely to cause trouble. He urged him to “kindly make arrangements for lifting these teachers and students as early as possible and report compliance.” Bhinder appears to have had a penchant for “lifting.” Thus, on September 25, he lifted Prabir Purkayastha from JNU. In spite of his claim that it was not a case of mistaken identity, and that Prabir had been a target all along, there was no police record on him until after he was abducted. The police field officer assigned to collect information on student activities at JNU had not filed any report mentioning Prabir. But once he was in police custody without a warrant, the paperwork had to be set right to make the unlawful lawful. ADM Ghosh issued a MISA warrant under the direction of his superiors. It was only on September 30, 1975, five days later, that a police report supplied the grounds for the warrant. It claimed that Prabir was a “staunch SFI worker” who had tried to stop students from attending classes, a claim unsupported by the field officer. The report went on to assert that though Prabir had joined JNU only in 1975, so powerful was his political image that Ashoka Lata Jain came under its spell and became romantically involved with him. The report was wrong. Though Prabir joined JNU only in August 1975, he had been spending time on its campus for over a year while conducting computer calculations at the nearby Indian Institute of Technology for his master’s thesis. Unaware of its faulty intelligence, the Delhi police proceeded to invent itself as an expert in matters of the heart. Prabir was a subversive who had beguiled Ashoka with his “political image” within a month of his arrival in JNU.

Four Parliament members wrote to Home Minister Brahmananda Reddy, pointing out that JNU teachers had condemned Prabir’s abduction and requested that he examine the propriety of the police action. Reddy, whom Om Mehta, his junior minister and Sanjay’s pawn, had upstaged, ordered an inquiry. To clear discrepancies, the Home Ministry asked for a report from the Intelligence Bureau, which stated that it had no information to indicate Prabir’s active role in organizing the student boycott of classes. But the Delhi administration closed ranks and flatly asserted otherwise. Prabir’s mother, Mrs. S. Purkayastha, submitted a parole application for her son to the chief secretary of the Delhi administration on November 5, 1975. On November 24, Dr. N. M. Ghatate filed a habeas corpus writ petition under Article 226 on Prabir’s behalf in Delhi High Court. While this was pending, he also filed a parole petition for him to appear in his viva voce examination in Allahabad to complete his master’s degree from Motilal College of Engineering. On December 1, three senior JNU faculty members submitted a petition for Prabir’s release, with supporting affidavits from students who had witnessed the police abduction.

In preparing the legal brief against these petitions, the Delhi administration asked the concerned officers for their opinion. ADM Ghosh recommended parole, but SP Bajwa did not. The police officers closed ranks. No, it was not a case of mistaken identity. The police did not grab Prabir and whisk him off and produce a warrant post facto late that night. Contrary to all documentary records, the SP (South) claimed that a police inspector accompanied by two subinspectors entered the JNU compound in a vehicle and executed a pending MISA warrant at 9:30 a.m. in an orderly fashion. Even Ghosh concurred in the cover-up. Bhinder read the petitions on Prabir’s behalf and recommended no response, as the matter was sub-judice. But everyone lied to protect Bhinder. Even Maneka Gandhi came to his defense. She stated that Prabir was one of the students who stopped her and claimed that she did not go home immediately but sat in the lawns. It was then that some officers in plainclothes came and arrested Prabir. No, there was no Sikh gentleman among them. The logbook of the car contradicted her account.

Bhinder appears to have had a penchant for “lifting.” Thus, on September 25, he lifted Prabir Purkayastha from JNU. In spite of his claim that it was not a case of mistaken identity, and that Prabir had been a target all along, there was no police record on him until after he was abducted. The police field officer assigned to collect information on student activities at JNU had not filed any report mentioning Prabir. But once he was in police custody without a warrant, the paperwork had to be set right to make the unlawful lawful… The report went on to assert that though Prabir had joined JNU only in 1975, so powerful was his political image that Ashoka Lata Jain came under its spell and became romantically involved with him. The report was wrong… Unaware of its faulty intelligence, the Delhi police proceeded to invent itself as an expert in matters of the heart.

Meanwhile, the police finally netted Devi Prasad Tripathi, DIG Bhinder’s original target. Along with two friends, Tripathi was walking from Old Campus to New Campus when a posse of policemen grabbed him, dumped him in a waiting van, and spirited him away. A month later, Sitaram Yechury, another JNU SFI leader, also found himself behind bars. These successes did not make the Delhi police go easy on Prabir. When the Delhi High Court ordered his release on parole, the Delhi administration wanted to appeal. But the Supreme Court was closed for winter vacation and would not reopen until January 4. Left with no path of resistance to the court order for parole, the Delhi administration nevertheless defied it by not releasing him and transferred him in handcuffs to Naini Jail in Uttar Pradesh near Allahabad on January 1, 1976. He appeared for his viva voce examination in the prison. Three days later, he was brought back to Tihar Jail in Delhi. His distraught parents ran from pillar to post to obtain his release. Using her Bengali connections, his mother contacted D. P. Chattopadhyaya, a minister in Indira’s government, for help. He wrote to Om Mehta in February 1976, prompting further inquiry by Home Ministry officials. Asked to reexamine the case and revoke Prabir’s detention, the Delhi administration cited Bajwa’s questionable evidence as the truth to rebuff the request. On March 3, Prabir was transferred to Agra Jail, where he spent the remaining days of his imprisonment. The news of his solitary confinement for twenty-five days caused his mother to have a nervous breakdown. There appeared to be no way to get her son released, no way to move, let alone hold accountable, the mysterious power birthed by the suspension of constitutional rights.

Beginning on June 29, the government introduced a series of presidential ordinances to amend MISA that extracted further life out of the rule of law. These ordinances forbade the courts from applying the concept of “natural justice” in cases involving MISA detainees, rendered inapplicable the provisions for the communication of grounds for arrest, and prevented advisory boards from reviewing detentions. No one, including a foreigner, could challenge detention on grounds of natural or common law; and grounds for detention were defined as confidential matters of the state and their disclosure, including to the detainee, against the public interest. This made preventive detention far more draconian and placed it beyond even the quasi-judicial scrutiny of advisory boards. It is worth recalling that critics in the Constituent Assembly had warned against the abolition of due process, fearing that it would lead to executive overreach. A much milder Preventive Detention Bill moved by Patel in 1950 had also provoked objections. The central government went on to immediately use the law. Over the years, various state governments also used versions of preventive detention laws. When MISA was first introduced in 1971 in the wake of the Bangladesh war, the government had stated, in the face of vociferous criticism, that it would not be used against internal dissent. It did not keep its promise. The MISA amendments tightened the screw further.

However, the amended MISA law, draconian as it was, did not permit the state to conduct arrests without recording the grounds for incarceration, even if they were not to be communicated to the detainee. But, as we have seen in Bajwa’s practice of communicating lists of persons to be arrested, often on the telephone, the police routinely violated the law. This was true not just in Delhi but everywhere. The required four-month review of individual cases also remained on paper. The government was callous in responding to requests for parole because of death or illness in the family, or to appear for examinations, as in Prabir’s case. Secretary Chawla warned an official against noting recommendations for parole on the file. It was “friendly advice,” he added.

Licensed to arrest on the flimsiest of grounds, the police detained over 110,000 people under MISA and Defence of Internal Security of India Rules. Many of them were members of banned organizations like the RSS, Anand Marg, Jamaat-e-Islami, and the Maoist CPI(ML), as well as non-CPI opposition parties. Mere membership in the banned organizations or alleged sympathy for them, not any documented prejudicial activity, was grounds for arrest. Alleged participation in secret meetings, criticism of the Emergency or the prime minister in the public arena or private conversations, and opposition to government policies were grounds for detention. A large number of suspected criminals in several states were also put behind bars under MISA. In several cases, their alleged offenses were committed more than five years before 1975. Several trade union activists were rounded up on the grounds that they previously participated in agitations against the management. New Delhi advised state governments against the indiscriminate use of MISA, but it could not control what it had unleashed. The Shah Commission, appointed in 1977 to investigate the Emergency’s “excesses,” concluded: “MISA was used as a weapon against all kinds of activities, not even remotely connected with the security of the state, public order or maintenance of essential supplies.”

Licensed to arrest on the flimsiest of grounds, the police detained over 110,000 people under MISA and Defence of Internal Security of India Rules. Many of them were members of banned organizations like the RSS, Anand Marg, Jamaat-e-Islami, and the Maoist CPI(ML), as well as non-CPI opposition parties. Mere membership in the banned organizations or alleged sympathy for them, not any documented prejudicial activity, was grounds for arrest… New Delhi advised state governments against the indiscriminate use of MISA, but it could not control what it had unleashed.

There are many examples, including Prabir’s, that substantiate Justice Shah’s conclusion. A notable example was the arrest of Primila Lewis. On July 2, Lewis arrived in Delhi along with her eight-year-old son, Karoki, on a flight from London. At the airport, the immigration officer examined her passport and read out her name with a tone of recognition. Soon, she and Karoki were whisked off to the International Departure Lounge. A long wait followed while Primila tried to reassure her tired and anxious son. Around 12:30 p.m., a posse of police officers entered the lounge and escorted the two into a waiting taxi, which took them to the Parliament Street Police Station. Another long wait followed. Primila knew the Emergency had let loose random arrests. But knowing what could now happen, with a child restless after a long international flight, heightened her anxiety. Around 5 p.m., she was served with a warrant of arrest under MISA. Her crime? She had ruffled some powerful feathers.

Primila, who was then thirty-five years old, had earned a master’s degree from Mount Holyoke College in the United States and taught English literature first at Indraprastha College for Women in Delhi and later at University College, Nairobi. After five years in Nairobi, she returned to India along with her English husband, Charles Lewis. She lived for a year in Bombay, where she became involved in working with those living in poor neighborhoods. The family moved in 1971 when Charles was posted to Delhi. Wishing to live simply, she chose to rent a farmhouse in Mehrauli, on Delhi’s outskirts. The area retained the flavor of the village that it had originally been, except now it sported the farmhouses of the Delhi gentry.

The elite list of farmhouse owners included Indira and her cousin B. K. Nehru, retired generals, prominent industrialists, former royalty, and senior civil servants, whose farmhands were mostly Dalit immigrants from northern and eastern India. Their children became Karoki’s playmates. This is how Primila became involved in their lives. One thing led to another, and she was soon organizing the farmhands. She formed a union that fought against unjust evictions and pressed for the implementation of the minimum wage law. The union scored one success after another, but it also brought Primila in the crosshairs of Navin Chawla, then the ADM of the area, who was soon to become a powerful force in the Delhi administration. The press was beginning to pick up the story of how the rich and powerful were flouting the law on minimum wages. Indira heard the complaints of the incensed elite and chastised LG Chand, who turned up the heat on Chawla. By 1975, Chawla was no longer the ADM of the area but was now the secretary to LG Chand and the power behind the throne. So, when Primila stepped off that plane on July 2, the immigration staff was briefed and the police were ready. She would spend the next eighteen months in prison and was released on parole on January 9, 1977.

As Primila’s swift dumping from an international flight to the prison shows, shadow power was capricious and unrestrained, and it could be brutal. Among the many who suffered was Lawrence Fernandes. The police picked up Lawrence from his home in Bangalore on May 1, 1976. They immediately began torturing him to extract information on the whereabouts of his brother George Fernandes, the Socialist leader who had gone underground. Lawrence knew nothing. Unconvinced, the police continued to interrogate and torture him for days. When his physical condition became grave and the police feared his death in custody, they summoned a doctor. He was not told Lawrence’s identity. With the patient obviously appearing physically abused, the doctor advised immediate admission into a hospital, but he was not taken to a hospital. The police had not even formally recorded Lawrence’s arrest. They fabricated the date of his arrest as May 10, nine days after the actual date, on the false charge of involvement in sabotaging railway tracks with bombs. Later, he was transferred to the Bangalore Central Prison in a broken physical condition. Initially housed with condemned prisoners, he was placed after protest with other MISA detainees. When he was released toward the end of the Emergency, the physical toll of torture and ill treatment was still visible on his body.

Primila knew the Emergency had let loose random arrests. But knowing what could now happen, with a child restless after a long international flight, heightened her anxiety. Around 5 p.m., she was served with a warrant of arrest under MISA. Her crime? She had ruffled some powerful feathers.

Lawrence was seized and tortured because he happened to be the brother of George Fernandes, who had led the crippling 1974 railway strike and was conducting an underground resistance. Lawrence’s misfortune was that he was the elusive George’s brother, but there were others who suffered brutal treatment without association to famous opposition leaders. A case in point is Jasbir Singh, a JNU student and an opposition party activist. The police arrested him and planted some posters and Naxalite pamphlets in his bag. They tied his hands and feet to a pole, which was suspended between two chairs that were dragged apart to make Jasbir swing in the middle. He vomited blood. When he complained, the inspector threatened to kill him and discard his body in the river. Dutifully following the law, the police produced him before a magistrate. Jasbir complained, but the magistrate paid no heed, and the torture became worse.

With no public knowledge and scrutiny allowed, the authorities were able to act without restraint. Jasbir, Prabir, Primila, and countless others were left with no recourse. This was not, however, the first time in India’s history that the police were able to act with impunity. As early as 1902, the Fraser Commission had identified corruption, brutality, and inadequate supervision of the constabulary at the local level as problems. Its recommendations for reforms remained on paper, however. The problem was structural. The British colonial rule established a modern state external to society. The population experienced the arms of the civilian administration and the police as alien forces with coercive command over them. The independent Indian government inherited this coercive structure and its laws but saw no need for a fundamental structural change in how the administrative state functioned.

Several committees in the postcolonial era made recommendations for reforms, but the government did not implement them. The poorly paid and trained police continued to govern the population with habitual arbitrariness and impunity. In 1977 the Shah Commission pointed to widespread police misconduct and suggested reforms, once again. The National Police Commission, established in November 1977 by Morarji Desai’s Janata government, studied policing comprehensively. Its report showed conclusively that the post-Independence monopoly of power by the Congress party produced a pattern of political interference in police work. The interaction between politicians and the administration for implementing government policies degenerated into daily intercession for political advantage. During elections, the police would look the other way as politicians employed criminal elements to intimidate voters. Politicians secured police compliance by wielding the threat of transfer. Under political pressure, the police routinely flouted norms and rules. In the absence of a concerted effort to cultivate a democratic culture, police misconduct at the behest of the socially and politically powerful was endemic.

V. C. Shukla

The imposition of press censorship ensured that there was no public knowledge or discussion of police atrocities. Western newspapers, which had universally condemned the imposition of the Emergency, were warned to follow the censorship rules. Sanjay saw to it that his mother booted out Information and Broadcasting Minister I. K. Gujral, who was seen as insufficiently enthusiastic of the new dispensation. Gujral’s replacement was V. C. Shukla, a Sanjay loyalist, who summoned foreign correspondents on June 29 and, “breathing fire and smoke,” warned them they risked expulsion if they defied the censor. On June 30, the government expelled Lewis M. Simons, the Washington Post correspondent. He was given twenty-four hours to leave. Apparently this was in retaliation for his dispatch of June 20 mentioning that the defense minister had asked the army chief to send soldiers in plainclothes for a rally in support of the prime-minister and that the order was withdrawn when the news leaked. Peter Gill of the Daily Telegraph and Peter Hazelhurst of The Times were expelled on July 22 for refusing to pledge that they would comply with the censorship guidelines, and the BBC withdrew Mark Tully rather than have him sign a written undertaking. Kevin Rafferty of the Financial Times was accused of acting as a courier for other foreign journalists and was refused entry. Martin Woollacott of the Guardian, who was then outside India, was told that he would not be admitted unless he signed the pledge.

This was not, however, the first time in India’s history that the police were able to act with impunity. As early as 1902, the Fraser Commission had identified corruption, brutality, and inadequate supervision of the constabulary at the local level as problems. Its recommendations for reforms remained on paper, however. The problem was structural. The British colonial rule established a modern state external to society. The population experienced the arms of the civilian administration and the police as alien forces with coercive command over them. The independent Indian government inherited this coercive structure and its laws but saw no need for a fundamental structural change in how the administrative state functioned.

Indira and Sanjay Gandhi

The Western press posed a nuisance with editorial denunciations of the Emergency and press censorship and criticism of Indira from afar. Protest statements and letters from old India hands and intellectuals in the United States and Britain, including her long-time American friend Dorothy Norman, rankled Indira. But irritating and disappointing as these were, she remained defiant. In any case, far more important was the job of taming the Indian press. Having given them a taste of its intentions by cutting off electricity on the night of June 25, the government warned that publishing blank editorials, as the Hindustan Times and Indian Express had done, would not be tolerated. K. R. Malkani, the editor of the RSS daily, the Motherland, which had published sensational stories on Indira and Sanjay, was arrested early on the morning of June 26. A month later, the police arrested the senior journalist Kuldip Nayar. He drew official ire because of his work for the Indian Express, a newspaper sympathetic to JP. The government did not spare his eighty-one-year-old father-in-law, Bhim Sen Sachar. A life-long congressman, he had served twice as the Punjab chief minister and several terms as governor of different provinces. But none of this mattered. The police arrested him for his audacity in writing to the prime minister and demanding the removal of press censorship and the restoration of freedom.

To tame the press, the government circulated detailed censorship guidelines on June 26 under the Defence of India Rules that prohibited any publication of news about the Emergency and actions under MISA without the scrutiny of the censor’s officer. In February 1976, it enacted the Prevention of Publication of Objectionable Matter Act against the printing of “incitement of crime and other objectionable matter.” In addition, daily censorship orders were communicated over the phone to newspapers to prevent the publication of anything considered against or embarrassing to the regime. Navajivan Press, established by Mahatma Gandhi, saw its printing facilities confiscated. Himmat, a weekly edited by Rajmohan Gandhi, the Mahatma’s grandson, was suddenly asked to make a substantial deposit because it published allegedly objectionable reports. Romesh Thapar, who was once Indira’s confidant but had turned a critic by 1974, miraculously continued to publish Seminar until July 1976. Perhaps the ax did not fall on the journal because of its limited subscription and because of Thapar’s previous association with Indira. Seminar published an issue called “Judgments” in December 1975. It contained articles on the laws of detention, writ petitions, the prime minister’s election case, and a statement by Palkhivala on constitutional amendments. As was the journal’s practice, the articles were not overtly political but there was no mistaking the political implications of the interpretations of the laws. There was nothing covert about the politics of its July 1976 issue devoted to “Where do we go from here.” It included an article by political scientist Rajni Kothari on restoring the political process and one by the writer Nirmal Verma on the importance of freedom. That was it. The ax fell, and Seminar ceased publication rather than submit the journal to pre-censorship. The Indian Express and the Statesman also encountered punitive measures from the government for showing signs of resistance.

All these measures had the desired effect. The newspapers complied and published official press releases, statements, and speeches by Indira and her minions. Political cartoons disappeared overnight. The dailies dutifully reported on Indira’s faux socialism, the highlight of which was her vaunted twenty-point program to remove poverty, abolish bonded labor, implement laws on land ceilings, advance social equality, and improve the economy. To this, Sanjay added his five-point program on birth control, slum rehabilitation, and beautification. With the party apparatus destroyed and the administration in a state of paralysis, there was no way to implement even the long-desired and uncontroversial social objectives. The only instrument at the regime’s command was its coercive power, which Sanjay and his lackeys deployed with abandon, as we will see later.

As information and broadcasting minister and Sanjay’s foot soldier, Shukla missed no opportunity to enforce compliance and mount propaganda. One that fell into his lap was a triptych presented to the prime minister in June 1975 by the famous artist M. F. Husain. Later hounded into exile by right-wing Hindu activists, Husain called his work “The Triptych in the Life of a Nation.” It was his response to the political crisis, though it was widely used and seen as an endorsement of the Emergency.

All these measures had the desired effect. The newspapers complied and published official press releases, statements, and speeches by Indira and her minions. Political cartoons disappeared overnight. The dailies dutifully reported on Indira’s faux socialism, the highlight of which was her vaunted twenty-point program… As information and broadcasting minister and Sanjay’s foot soldier, Shukla missed no opportunity to enforce compliance and mount propaganda. One that fell into his lap was a triptych presented to the prime minister in June 1975 by the famous artist M. F. Husain. Later hounded into exile by right-wing Hindu activists, Husain called his work “The Triptych in the Life of a Nation.” It was his response to the political crisis, though it was widely used and seen as an endorsement of the Emergency.

The first, titled Twelfth June ’75 shows the figure of Janaki, the daughter of Earth, set high above in the sky and beyond the reach of the accusing fingers from the menacing headless body below named Janata. The second, titled Twenty fourth June ’75, depicted Mother Earth in turmoil, her hair scattered over the Himalayas, her knees pulled up toward the Bay of Bengal, her breasts drowned in the Indian Ocean, and her gaze fixed on the scales of justice titled “Supreme.” The third, and the most controversial, called Twenty sixth June ’75, was an image of Goddess Durga riding a roaring tiger, determined to eliminate evil.

The Information and Broadcasting Ministry arranged for the exhibition of the triptych in Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta, New York, and Prague. Reporting on the response, the ministry noted that it was favorable, though in Prague some young and old Czechoslovak artists were reportedly startled by the triptych’s “high degree of sex symbolism.” They were assured that the work was not pornographic but modern interpretations of India’s traditional mythology. Perhaps drawing from Husain’s note describing his motivations for the triptych, the ministry’s secretary enthusiastically compared the paintings to Picasso’s Guernica and asked the director of the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi to house them permanently in the museum. The director refused, calling the comparison to Picasso an insult to the great master. Thwarted, the ministry directed that the paintings be returned to Husain’s son, although they were gifts to the prime minister. So tainted was the triptych by its association with the Emergency, it is no longer in public circulation.

Kishore Kumar