ARCHIVE

The Twin Burdens: Historiography and Sources

-

THE BURDEN OF HISTORIOGRAPHY

The history of how ‘others’ were perceived and represented in the past in India has hardly been conscientiously worked upon by historians so far [two exceptions are Romila Thapar’s ‘The Image of the Barbarian in Early India’ and Aloka Parasher’s ‘Mlecchas in Early India: A Study in Attitudes Towards Outsiders upto AD 600’]*, although clear assumptions regarding such perception and representation have been strongly entrenched in Indological studies, since, perhaps their inception. These assumptions continue to dominate, without adequate and fresh references to primary sources, our own understandings of India’s past, and one finds that in the matter of reinforcing assumptions regarding the ‘others’ of the past, different strands of historical thinking—be they Imperialist, ‘Orientalist’, National or of other categories—curiously seem to converge. This is indeed curious, since, for example, while for the Orientalists, the Indian culture, as a segment of the Oriental culture, may represent the other, the prerogative, at the same time, of defining the other within this otherness of lndia was appropriated also by the Orientalists. One example of this is the accentuated dichotomy between the Aryan and the non-Aryan, which continues to haunt Indian historical writings. Equally, or perhaps more, critical, particularly for the purpose of what we intend to investigate in this monograph, are the implications of the periodization of pre ‘British’ Indian history into Hindu and Muslim [James Mill to whom is attributed the scheme of periodization, has a curious assessment of the nature of ‘Muslim rule’ in India: ‘The conquest of Hindustan, effected by the Mahommedan nations, was to no extra-ordinary degree sanguinary or destructive. It substituted sovereigns of one race to sovereigns of another; and mixed with the old inhabitants a small proportion of new; but it altered not the texture of society; it altered not the language of the country; the original inhabitants remained the occupants of the soil; they continued to be governed by their own laws and institutions; nay, the whole detail of administration, with the exception of the army, and a few of the more prominent situations, remained invariably in the hands of the native magistrates and offices. The few occasions of persecution, to which, under the reigns of one or two bigoted sovereigns, they were subjected on the score of religion, were too short and too partial to produce any considerable effects.’ Yet, Mill stresses the dichotomy of two civilizations in the context of lndian History: Hindu and Muslim, and remarks: ‘The question, therefore, is whether by a government, moulded and conducted agreeably to the properties of Persian civilization, instead of a government moulded and conducted agreeably to the properties of Hindu civilization, the Hindu population of India lost or gained; Mill was in no doubt about the distinctiveness and relative qualities of what he considered two nations and two civilizations: ‘itis necessary to ascertain, as exactly as possible, the particular stage of civilization at which these nations had arrived… It is requisite for the purpose of ascertaining whether the civilization of the Hindus received advancement or depression, from the ascendancy over them which the Mohammedans acquired;’ The equation of civilization with religion is implicit in Mill’s comments.]*.

While for the Orientalists, the Indian culture, as a segment of the Oriental culture, may represent the other, the prerogative, at the same time, of defining the other within this otherness of lndia was appropriated also by the Orientalists. One example of this is the accentuated dichotomy between the Aryan and the non-Aryan, which continues to haunt Indian historical writings. Equally, or perhaps more, critical, particularly for the purpose of what we intend to investigate in this monograph, are the implications of the periodization of pre ‘British’ Indian history into Hindu and Muslim.

This schema of periodization has implications, such as construction of homogenous politico-cultural entities which are, by nature, changeless and can be antagonistic to other similarly homogeneous, changeless politico-cultural entities. These and similar other implications await rigorous identification and analysis. However, scrutiny, even at a superficial level, suggests that the schema underscored, in a very clear fashion, how the boundary of the ‘otherness’ was to be defined. The boundary relates to both history and culture—to how the end and beginning of periods of history were to be considered and how cultural lines could be prevented from overlapping [Although ‘nationalist’ historiographical agenda is believed to have been set in motion by challenging Orientalist notions, the nationalists themselves adopted the essential Orientalist premises and methods for writing about their country’s past. Partha Chatterjee has shown recently how big the difference between Mrityunjay Vidyalankar s ‘Rajavali’, written for the use of young officials of the East India Company in Calcutta in 1808, and Tarinicharan Chattopadhyaya’s ‘Bharatvarsher Itihas’ – first published in 1858 – is. While Vidyalankar’s text can be considered a ‘Puranik History’, Chattopadhyaya’s ‘history of the country’, informed by colonial historiography of the period, has a striking opening: ‘India—Bharatavarsa—has been ruled in turn by Hindus, Muslims and Christians. Accordingly, the history of this country—des—is divided into the periods of Hindu, Muslim and Christian rule or rajatva.]*.

This schema of periodization has implications, such as construction of homogenous politico-cultural entities which are, by nature, changeless and can be antagonistic to other similarly homogeneous, changeless politico-cultural entities… scrutiny, even at a superficial level, suggests that the schema underscored, in a very clear fashion, how the boundary of the ‘otherness’ was to be defined… how the end and beginning of periods of history were to be considered and how cultural lines could be prevented from overlapping.

To an extent, the schema and the underlying assumption regarding periodization were derived from an insistence upon a unitary vision, marginalizing regional specificities and thereby putting forward generalizations for Indian history [Antagonism to regional history is articulated clearly in the following words from M.D. Hussain’s ‘A Study of Nineteenth Century Historical works on Muslim Rule in Bengal: Charles Stewart to Henry Beveridge’: ‘It [regional history] gives, if we may so express ourselves, a sort of double plot to the history; and what is worse, it renders the grand plot subservient to the little one. The object too, is not, in our opinion, worthy of the sacrifice.’ Whether it is a question of political sovereignty or of culture, total neglect of localities and regions not only blurs our vision of ground-level patterns but also hinders our understanding of the ‘grand plot’ itself.]*. The periodization schema and the associated characterizations of periods therefore continue to be adopted and used by historians, writing on India, or on a region as its component, even when history writing has departed very substantially from the context in which the schema originated. One can demonstrate this continuity by referring to a wide range of writings—from school textbooks through Nationalist to post-Nationalist analyses of what may be called the twilight zone, in historiography, of ‘pre-medieval-medieval’ juncture of Indian history. While the terms Hindu and Muslim may not continue to be used in the context of periodization, by and large the notion of ‘Hindu’ – ‘Muslim’ divide remains the implicit major boundary line, separating one Indian past from the other, and thereby marginalizing the continuity, interaction and modification of cultural elements in history. It is not the intention of this work to go into historiography in any detail. Nevertheless, the point about the persistent image of politico-cultural dichotomy, and of the stereotypical perception of the ‘other’, needs to be established by referring to particular works of history, precisely dated and therefore evidence of the authentication of assumptions, held as valid at precise chronological points of their articulation. In arguing about the persistence of historiographical premises, I start by citing the Foreword in the fourth volume of a well-known series, which is in regular use among students in Indian universities and to which contributions came from the best available experts in the field.

K.M. Munshi, in his Foreword to The Age of Imperial Kanauj (Vol. 4 of The History and Culture of the Indian People) wrote:

‘The Age begins with the repulse of the Arab invasions on the mainland of India in the beginning of the eighth century and ends with the fateful year AD 997 when Afghanistan passed into the hands of the Turks. With this Age, ancient India came to an end. At the turn of its last century, Sabuktigin and Mahmud came to power in Gazni. Their lust, which found expression in the following decades, was to shake the very foundations of life in India, releasing new forces. They gave birth to medieval India. Till the rise of the Hindu power in the eighteenth century, India was to pass through a period of collective resistance (italics added).’

To an extent, the schema and the underlying assumption regarding periodization were derived from an insistence upon a unitary vision, marginalizing regional specificities and thereby putting forward generalizations for Indian history.

What K.M. Munshi wrote for the series edited by R.C. Majumdar, who too held identical views, is not very different from the dominant approach characterizing Indian history writing generally. In the context of Indian nationalist historiography, the ancestry of the assumptions separating the Hindu period from the Muslim period can be firmly dated to mid-nineteenth century enterprises of writing the history of the country. It has been shown [From Partha Chatterjee’s ‘Claims on the Past’]*:

‘This history, now, is periodized according to the distinct character of rule, and this character, in turn, is determined by the religion of the rulers. The identification here of country (des) and realm (rajatva) is permanent and indivisible. This means that although there may be at times several kingdoms and kings, there is in truth always only one realm which is coextensive with the country and which is symbolized by the capital or the throne. The rajatva, in other words, constitutes the generic sovereignty of the country, whereas the capital or the throne represents the centre of sovereign statehood. Since the country is Bharatvarsa, there can be only one true sovereignty which is co-extensive with it.’

Historiographically, what strikes one as critical is that the ‘otherness’ of sovereign, medieval, Muslim India is a persistent image, and an undifferentiated, ancient, Hindu India continues to be presented as facing, first a threat and then collapse, politically and culturally, when the Muslims arrive. This is a discourse which, despite the accent on synthesis and positive interaction between earlier and Islamic culture in one variety of nationalist history writing, has not been examined adequately with reference to sources which bear upon the early phase of the association of Muslim communities with India. Indeed, the discourse continues to receive reinforcement even in recent, highly accomplished writings as a supportable mindset, and I would like to cite two recent pieces of writing which, I believe, would bear my point out as substantiating evidence. In one, an attempt has been made to bring into sharp relief the apprehension of threat which Muslim invasions generated in Indian society. This, apparently, can be seen in the way in which the text of the Ramayaṇa, woven around the heroic deeds of its central character Rama, came to supply an idiom or ‘vocabulary’ for political imagination for the public mind in India between the eleventh and the fourteenth century. In the context of the historical situation of North India and the Deccan, in what is called the ‘middle period’, the following is thus asserted [from Sheldon Pollock’s ‘Ramayana and Political Imagination in India’]*:

‘In fact, after tracing the historical effectivity of the Ramayaṇa mytheme— tracing, that is, the penetration of its specific narrative into the realms of public discourse of post-epic India, in temple remains, ‘political inscriptions’, and those historical narratives that are available—it is possible to specify with some accuracy the particular historical circumstances under which the Ramayaṇa was first deployed as a central organizing trope in the political imagination of India (italics added).’

Historiographically, what strikes one as critical is that the ‘otherness’ of sovereign, medieval, Muslim India is a persistent image, and an undifferentiated, ancient, Hindu India continues to be presented as facing, first a threat and then collapse, politically and culturally, when the Muslims arrive.

The central organizing trope was the Ramayana’s hero Rama, who represented the victorious divine against the ultimately subdued demon and ‘the tradition of invention—of inventing the king as Rama—begins in the twelfth century’. The need to invent the king as Rama is related to the perception of threat-against the ideal political and moral order of Ramarajya, the Turuska marauders being the demons who posed the threat.

While thus the neat schema of periodization in terms of Hindu-Muslim divide is, by implication, restated, another way of representing the image of an absolute break in Indian history is by relating the discourse of power to the cultural hegemony of Islam. ‘The “arrival” of Islam as a discourse of state power had introduced a “cultural fault-line” between the Muslims and the non-Muslims.’ The ‘cultural resistance’ against Islam as a ‘discourse of power’ throughout the medieval period in India, in this image, could take the form of ‘a strange kind of “silence” on the part of Hindu authors about their Muslim contemporaries’; it could also be of the form of ‘thousands of individual acts of dogmatic ritual behaviour and evasion’.

This historiography of periodization relates to the problem of perception and representation in the following ways. One, it constructs, for the historical past, an agenda of conscious public action, in the form of ‘collective resistance’ or ‘cultural resistance’. Two, it also constructs collective consciousness for a particular past—a past which is confronted with a threat; it is this collective consciousness which can explain a ‘central organizing trope in the political imagination of India’. Both constructions hinge on confident recovery of contemporary perceptions, not individual but cultural, in historical situations which are projected as understandable only in terms of irreconcilable bi-polar differences and fixed identities.

The objective of the present work is to contest both these constructions. The main method in doing this will be the simple expedient of re-examining the sources, but as sources are voluminous, the method of re-examination itself should involve some consideration of the sources in their own cultural contexts. No study can exhaust all sources which may have a bearing on the problem under investigation, but since historians’ own perceptions, rather than the source-by-itself, largely determine the selection and interpretation of sources used, any critique of available generalizations essentially means reading the same or same types of source-material with a measure of mistrust and with new curiosities. This in turn may lead to sources which have not been used adequately in the past.

I would thus like to make it clear that it is not my intention to gloss over the primary difference between Islam, which did become one of the discourses of power (but not the sole discourse because, then, what would be the dominant social discourse within the stratified ‘Hindu’ society?), and the cultural pattern (in a broad socio-religious sense) which was ‘perceived’ as and put into the basket called ‘Hindu’. My attempt is also not to undermine actualities of conflict along lines, sometimes seen even contemporaneously, as Hindu or Muslim. But even this primary difference is one difference out of many, which is mostly presented out of context, and my objection is basically to the way in which Indian history continues to be truncated between ‘Hindu’ and ‘Muslim’, and, obliterating other types of difference, the projected difference is made to represent fundamental historical change as well.

While historians continue to subscribe to this notion of historical change perhaps by adhering to historiographical conventions and perhaps also by attributing their contemporary perceptions to the subjects of their investigation, the point to ask anew is: how does one construct perceptions of the past? To clarify, when we talk about interface between Islam and Indian society in, say, the period between the eighth century and the fourteenth century, are we not, in posing the problem the way we do (i.e. interface between Islam and Indian society), imposing the contradictory notions of polarity and homogeneity implicit in the formulation of the problem, upon a particular past? Further, in relating the actualities of conflict only to particularly constructed polarities, historians tend to underscore the conflict potential of a particular polarity to the exclusion of others; this is taken to further buttress the generalization about cultural characteristics, already made. Finally, once a particular polarity is historiographically argued, one tends to forget to ask: do perceptions change over time? If other things change in history, there is the further possibility that attitudes do so too; and, there is the further possibility too that attitudes do not constitute a homogeneity.

When we talk about interface between Islam and Indian society in, say, the period between the eighth century and the fourteenth century, are we not, in posing the problem the way we do (i.e. interface between Islam and Indian society), imposing the contradictory notions of polarity and homogeneity implicit in the formulation of the problem, upon a particular past? Further, in relating the actualities of conflict only to particularly constructed polarities, historians tend to underscore the conflict potential of a particular polarity to the exclusion of others; this is taken to further buttress the generalization about cultural characteristics, already made. Finally, once a particular polarity is historiographically argued, one tends to forget to ask: do perceptions change over time? If other things change in history, there is the further possibility that attitudes do so too; and, there is the further possibility too that attitudes do not constitute a homogeneity.

There is then no alternative to continuously revisiting the sources which, I have already mentioned, cannot be identified with any finality once for all. The deliberate, or, often, not so deliberate choice of sources by historians, leaves even what is available largely hidden from the audience of history. Sources being thus visible mostly in terms of the historian’s monologue with them, it is all the more necessary then that other voices too intervene.

- THE BURDEN OF WRITTEN SOURCES

‘Literature may provide facts for social scientists, especially in the absence of other documents. But literature refracts as much as it reflects; one needs to take account of the “specific density” of the literary medium, its “refractive index”, before we can truly use literary materials as documents. To use them in a literal straightforward fashion is to misuse them… Unless we enter the realm of symbolic values that writers express through the “facts” and “objective entities”, the facts themselves would be commonplace or misunderstood.’

—A.K. Ramanujan, ‘Toward an Anthology of City Images’, in Richard G. Fox, ed., Urban India: Society, Space and Image.

The realm of symbolic values, or repertoire of perceptions that. K Ramanujan points to, could bear upon representations of historical situations in many ways, and several preliminary points need to be made here. One is that written sources that relate to the ruling groups of the period which is the primary focus of the work, and also from later periods, tend to convey cultural premises and practices of particular sections of society—which in the absence of a better alternative might be called elite. This is not to say that the premises remains confined to permanently fixed sections of society because they are also the adopted premises of those who aspire for elite status; the channels for discrimination of cultural premises too were many. But the production of the written word, in a language like Sanskrit, was the work of the literate elite, the Brahmānas, the Kayasthas, the Jainas and comparable groups. The choice of the premises to be projected in the written text, whether the text is that of a land-grant inscription or that of a mahakavya, at the historical moment when the text was prepared, was that of a literate elite who, in the process of creating the text, was drawing upon a well established pool of conventions, motifs and symbols. His choices, therefore, cannot be material for construction of public consciousness, but only of dominant premises. The point about choice relates to the range of material the creator of texts uses; to select arbitrary samples on his behalf, when analysing the text, would be anachronistic, imposing the analyser’s preferences on the author, and, from there, on to the society at large. We shall take up specific examples for elucidating these points later.

The deliberate, or, often, not so deliberate choice of sources by historians, leaves even what is available largely hidden from the audience of history. Sources being thus visible mostly in terms of the historian’s monologue with them, it is all the more necessary then that other voices too intervene.

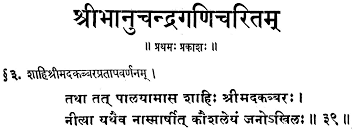

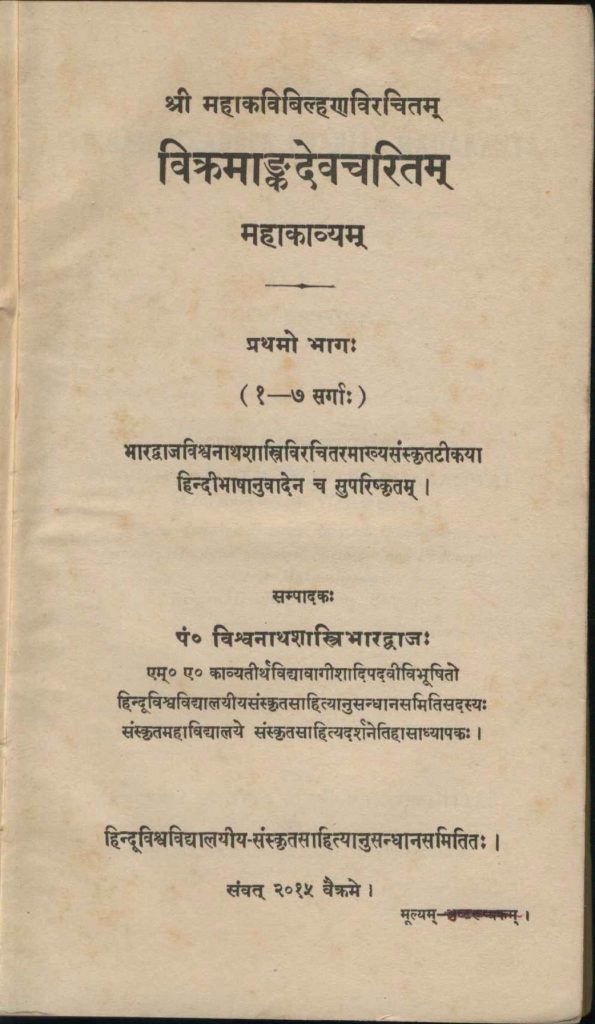

The second point is that written sources, perhaps more than other sources which may be used for historical reconstruction, demand that they be viewed not only diachronically but synchronically as well. An accent on the synchronic view is to ensure that the historian is aware of the available range. While the diachronic view will make it clear that such a textual genre as Carita, woven around a central character, emerges from a certain point of time and therefore requires explanation in terms of the context of its origin, the synchronic view or the horizontal view will ensure that one does not miss out on the simultaneity of many patterns. The Vikramankadeva carita of Bilhana, of which the central character was Vikramaditya Tribhuvanamalla of the later Calukya royal family of what is now Karnataka, is an important text of the late eleventh century. However, it is a text representing a particular genre; it is not a text which can be considered to represent the total range of poetic conventions, not to speak of the range of realities constituting eleventh century Indian society. Consider, for example Subhasitaratnakosa an almost contemporary anthology of Sanskrit poems prepared in eastern India in which the concerns of the poets represented are very much removed from the courtly concerns of the Vikramankadeva-carita. The two represent ‘realities’ of different kinds, although both may have been products of the same literary tradition. If one were speaking of a period closer to our own times—say the period of Akbar—there would surely be a variety of written words (apart from the uncodified ones) besides the major texts in different languages, and they all are important—not because they contain authentic historical material—but because they originate in and relate to different contexts of the same period. One can thus cite Bhanucandra-carita, the ‘biography’ of a Jaina teacher which was written by Bhanucandra’s disciple, placing him in close proximity to the emperor of Delhi, alongside a comparatively unknown inscription from Malwa. The inscription eulogizes both a local family of merchants with Jaina leanings and a local Rajput family which fights local Muslim rulers and looks up to the Muslim emperor of Delhi for grant of landed estates. They are not necessarily complementary sources; they are independently important as texts with separate loci, which nevertheless suggest a linkage in a situation of simultaneity of many patterns.

‘Literature may provide facts for social scientists, especially in the absence of other documents. But literature refracts as much as it reflects; one needs to take account of the “specific density” of the literary medium, its “refractive index”, before we can truly use literary materials as documents. To use them in a literal straightforward fashion is to misuse them… ’ —A.K. Ramanujan

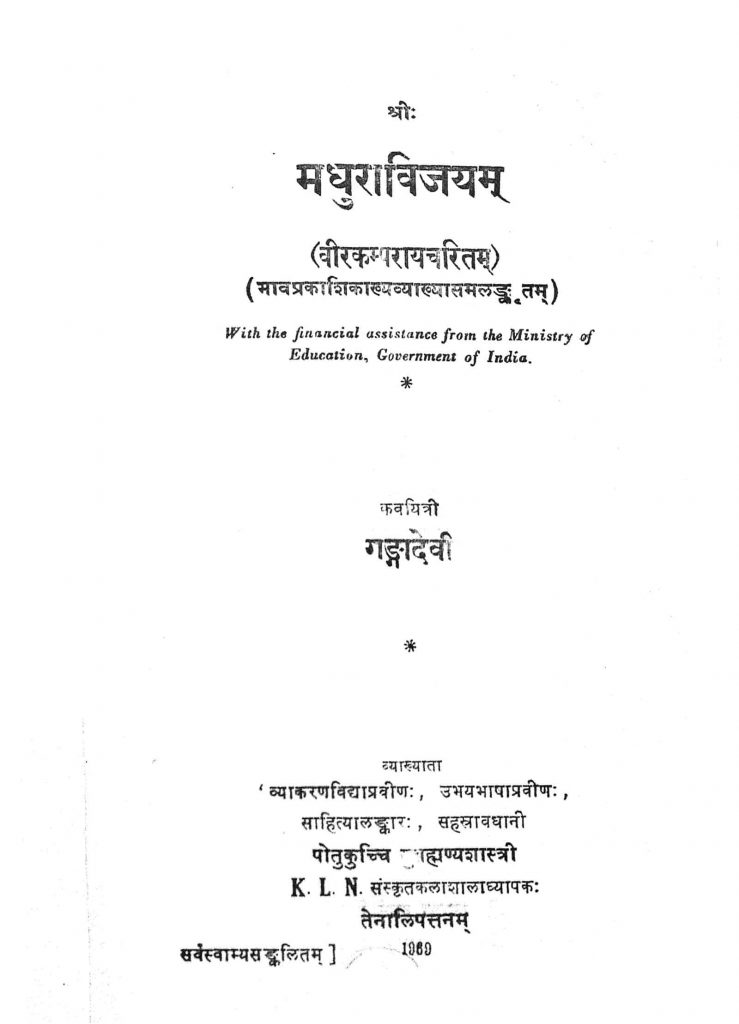

Isolating a single high point in the structure of an individual text may not be a sound methodological device either. At least, cautious comparison with narratives within the text and with other texts is what would be expected of one making generalizations. Let me again cite a few examples. Prthviraja-vijaya of Jayanaka, Hammiramadamardana of Jayasimhasuri, Madhura-vijaya of Gangadevi and Saluvabhyudaya of Rajanatha Dindima are all generally taken to have a single central focus: the narrative of military exploits against a Yavana or Turuska adversary. All these texts do have references to military exploits—quite often at variance with what actually happened—against a Yuvana/Mleccha/Turuska adversary; there are, of course, many other texts created in the same period, which contain other narratives. How does one compare the narratives of the texts cited, which will be shown to have different foci [One can refer to ‘Hammiramadamardana’ the importance of which is underlined in view of its being ‘a drama on a contemporary historical event’. The play which, according to its author, contained all nine sentiments, is on the curbing of the pride of Hammira, the Muslim ruler, by Vaghela ruler Viradhavala’s minister Vastupala, but Yadava ruler Simhana and the ruler of Lata are shown to be equally troublesome adversaries in the play. Vastupala’s diplomatic manouverings against the Muslim ruler are rather complex, and include sending a false report to the Caliph of Baghdad and holding out promises to Gurjara princes with lands of the Turuskas; the curbing of Hammira’s pride in the end consists in entering a friendly alliance, through a kind of black-mail.]*, with narratives in such texts as Sandhyakaranandi’s Ramacaritam or Padmagupta’ s Navasahasanka-carita? In analyzing what historians tend to take as a political narrative with a single focus but what may have had a broader significance for the creator of a text writing in a particular historical period, it is necessary to be careful about stock-taking. In other words, if one is considering adversaries in a political narrative, then it needs to be noted who, according to the author of the text, needed to be subdued by the central character of the text; isolating one opponent from a multitude of others, or one text from contemporary others, can be very much misleading when one is trying to comprehend the ideological world of the authors.

Understanding the ideological world through texts takes us on to the internal structures of the texts: both to the ways the segments of the text may be seen to have related to one another and to the ways the authors deal with conventions, language, similes, images and so on. I would like to argue that instead of being necessarily jolted into projecting a world of sharply bipolarized and antagonistic elements, the creators of texts rather tended to expand this world by using existing literary conventions to incorporate within it new empirical elements of history. These literary conventions, with their elements of diversity, also had space for perceptions of ‘others’ and of the threats which the society may have been perceived to have confronted. If new historical situations were perceived in terms of threats or in terms of ‘others’ being associated with them, the existing conventions could be extended for textual explications of the situation. This could be done, even when remaining fully cognizant of the details of a historical situation which could be stylized. Only, what was accommodated within available concepts, conventions and vocabularies, can hardly be taken as a statement made for the communication of historical reality.

If one is considering adversaries in a political narrative, then it needs to be noted who, according to the author of the text, needed to be subdued by the central character of the text; isolating one opponent from a multitude of others, or one text from contemporary others, can be very much misleading when one is trying to comprehend the ideological world of the authors.

From the foregoing, how should one characterize the written sources that bear upon the question of ‘otherness’ of communities that interacted with society in India from around the seventh-eighth century onward? I think it is indeed necessary, when one is using a cluster of texts for understanding perceptions and representations, to clarify whether our concern about perceptions was the concern of the texts at all. This is not to say that the historian’s concern is invalidated that way. Nevertheless, my preliminary answer to this query would be that neither the epigraphic nor the literary texts of the early medieval period-taken in their collectivity were composed with the purpose of communicating perceptions of communities. They had altogether different functions. The inscriptions, despite the fact that early medieval inscriptions differed substantially from their earlier counterparts in contents and in styIe, had one central concern: recording of gift and of patronage. The context of the gift introduced the royal element whose presence and whose temporal qualities, like the spiritual qualities of a Brahmana, a preceptor or a priest, had to be located in the context of the gift. The inscriptions, even when rulers were eulogized by highlighting their real or imagined military exploits and personal qualities were thus not political inscriptions per se, because political could not be separated from the broad social context in which grants were made. The more appropriate perspective from which to view the inscriptions would therefore be legitimational rather than overtly political. It is important to note this difference, because, as I shall try to demonstrate later on, legitimation, rather than any handy political explanation, will clarify much better the way the rulers in general—and not necessarily rulers belonging to any particular community—continued to be portrayed in the texts in ‘indigenous’ languages. If there are political references to other communities—and there often are in early medieval/medieval sources—then they, I feel, have to be understood in terms of the overall context of legitimation, in which gift and patronage were what were relevant. This was a context which could—and did—make bipolar distinction, but this would be a distinction between those who could be legitimized and those who could not; this is not the distinction, as envisaged by modern scholars, between ‘indigenous’ and ‘non-indigenous’ categories.

The texts of the genre of Carita or Mahakavya similarly were not ‘historical narratives’ as such; they were both ‘biographies’ and ‘not biographies’. They were biographies in the sense that the text was woven around a historical character; they were not biographies as they were not simply intended to record only the actual events in the life of the hero, irrespective of whether the hero was a royal figure or a merchant. The portrayed life was the reflection of an ideal reality which, of course, had to match the specific station of the hero. For a king, the reality had to relate to the relevant spheres of conquests, love and munificence; for a merchant, it was the qualities of piety and munificence in consonance with social and economic status. Varieties of reference, including reference to social and ethnic groups, would constitute the world of the hero of the biography. The meaning of a particular reference, whether it relates to conquest, love, piety or munificence, should derive from the meaning of the total world—political, economic, social, cultural ideological—of the biography; it should not stand in isolation from the meaning of the rest of the biography. [The conventions applied to the creation of epigraphic texts as much as to those of Caritas. It has been recently shown that since women were not supposed to be rulers, the representations of the achievements and the person of Kakatiya queen Rudramma were those of a male ruler. However, ‘The ideal of kingship was so strongly correlated with the notion of manliness that even inscriptions referring to Rudramadevi as a woman could praise her only in distinctly masculine ways. That is, Rudrama’s greatness as a ruler could be expressed only by lauding her heroic acts.’ Further, ‘Depiction of men as champions or as warriors whose fierceness struck terror in the hearts of enemies were widespread in this period. Indeed, it would appear from a survey of male prasastis that the main claim to legitimacy and prestige was success in battle…. Religious beneficence was considered desirable in a man but not essential to his fame.’ From Cynthia Talbot’s ‘Rudrama Devi, the Female King: Gender and Political Authority in Medieval India’.]

It is possible to try and reconstruct perceptions and representations of ‘others’ from such texts, but, then, the reconstruction has to be in consonance with the overall structure of the text and its repertoire of words, expressions and images. My attempt therefore is not to single out but to understand multiplicity. Growing intensity of specific terms or of specific images may indeed be a pointer to historical change and change in perception. That such change is already evident in the period under discussion is not a given historical truth, necessarily not even a satisfactory assumption. The contexts in which the terms and images appear will be taken up in the next two chapters.

*Footnotes and citations have been removed from the excerpt for purposes of smoother reading. They can be found in the book. However, certain footnotes which were essential to the understanding of the excerpt have been included at the places where the author had intended them to be in crochets.

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya. You can buy Representing the Other? Sanskrit Sources and the Muslims here.

In the colonial period, the threat of the lecherous male gaze was used by the new patriarchy to restrict access to employment and public space for women, maintaining a patriarchal division of labour. Read how this process unfolded in our newest excerpt.

Saurav Kumar Rai

__

Was Lala Lajpat Rai's Hindu nationalism congruent with the principles of secularism? Explore our latest excerpt from Vanya Vaidehi Bhargav's fresh off-the-press book - Being Hindu, Being Indian: Lala Lajpat Rai's Ideas of Nation for more.

Vanya Vaidehi Bhargav

__

Popularly, we think that political cartoons question the powerful but what if this was not the case? What if political cartoons, replicated structures of the socially dominant? Read how in our new excerpt on political cartoons featuring Dr. Ambedkar.

Unnamati Syama Sundar

__

On Martyrs' day 2024, read the poet Sarojini Naidu's tribute to Gandhi given over All India Radio two days after his assassination.

Sarojini Naidu

__

On Republic Day, the Indian History Collective presents you, twenty-two illustrations from the first illustrated manuscript (1954) of our Constitution.

Indian History Collective

__

One of the key petitioners in the Ayodhya title dispute was Bhagwan Sri Ram Virajman. This petitioner was no mortal, but God Ram himself. How did Ram find his way from heaven to the Supreme Court of India to plead his case? Read further to find out.

Richard H Davis

__

Labelled "one of the shortest, happiest wars ever seen", the integration of the princely state of Hyderabad in 1948 was anything but that. Read about the truth behind the creation of an Indian Union, the fault lines left behind, and what they signify

Afsar Mohammad

__

How did Bengal get a large Muslim population? Was it conversion by ruling elites was there something deeper at play? Read Dr. Eaton's classic essay to find out.

Richard Eaton

__

An excerpt from Shailaija Paik's new book 'Vulgarity of Caste' that documents the pivotal role Tamasha (the popular art form) has played in reinforcing and producing caste dynamics in Marathi society.

Shailaja Paik

__

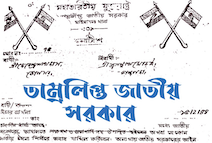

In 1942, two sub-districts in Bengal declared independence and set up a parallel government. The second part of our story brings you archival papers in the form of letters, newspaper reports, and judicial records documenting this remarkable movement.

Indian History Collective

__

In 1942, five years before India was independent, two sub-divisions in Bengal not only declared their independence— they also instituted a parallel government. The first in a new series.

Indian History Collective

__

In his own words, read Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi's views on the proselytising efforts taken on by the organisations such as Arya Samaj, Tabhligi Jamaat, and the Church Missionary Society of England.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

__