ARCHIVE

The Battle of the Somme

Nariman Karkaria

At last, it was our turn to see action, something we had been waiting for with our eyes peeled. Some of the soldiers were very eager to see the Germans in person and flaunt their muscle power, while quite a few were most distressed by the orders to advance forward to the front lines. We were to participate in the Battle of the Somme, which has already achieved legendary status in the Great War.

The Role of the Indian Army

Indian bicycle troops at a crossroads on the Fricourt-Mametz Road, Somme, France. Dated July 1916. From the collection of Imperial War Museums, London.

The Indian Army also took part in the Battle of the Somme.

The Bengal Lancers advanced under heavy fire from the Germans right up to the German trenches and forced them to retreat. On this occasion, our platoon was ordered to advance to the firing line. Our undercover march started at about one o’clock in the night. We had been strictly warned not to utter a single word. With great difficulty, we managed to advance, digging a few trenches and walking all through the night, only to find ourselves in a very unfortunate position in the morning. A German observation balloon which had been flying above us had spotted us, and very soon our route came under heavy fire. Shells were exploding all around us. To escape them, we would lie flat on the ground for a short while before running to advance a little forward. A wave of fear rippled through our platoon. Soldiers were falling all around us with piteous shrieks, but there was nothing that could be done. Each man was on his own and could not be bothered about anybody else. Others would advance by stepping on those injured soldiers who had fallen to the ground. We had no option but to move forward. We also had no idea what kinds of difficulties we were to face as we advanced. Many of our men were lagging behind, but we could not wait for them, and at about twelve noon we reached the famous jungles of Del Ville Wood where we felt we could finally heave a sigh of relief. But fate had other things in store for us. There were no trenches beyond the next twenty-five yards from where we were located. We could not step out of the trenches as we would have been sitting ducks for German guns. The Germans were hardly at any distance from where we were—say about a hundred yards away in their trenches. In spite of this situation, the Commanding Officer gave orders to advance further. We had no option but to run, and we ran in pairs. We would advance about ten steps before throwing ourselves flat on the ground. Our progress did not last very long. Soon enough, the enemy started firing at us with their machine guns.

We were staring death in the eye. But as luck would have it, there had been a fierce battle on this very site just four days ago, and the bodies of dead soldiers were lying all around us. These corpses proved very useful in sheltering us from the enemy gunfire. As we advanced, we would lie behind these corpses, and they would act as our shield taking all the gunfire. Ah, what a terrible experience! Just one bullet and we would also have joined the army of cold corpses!

War in the Skies

After a very desperate battle and the loss of over fifty soldiers, we were lucky enough to be able to take possession of the trenches. Because of the non-stop action during the night and the better part of the day, we had not even had a cup of tea, much less anything to eat. I had managed to eat a couple of biscuits while moving forward. This was all I had had, with which I had to be content for the whole day. Once we took possession of the trenches, the different companies of the platoon were immediately assigned positions. While the A and C Companies were assigned the forward trenches, the B Company was assigned the communication line, which was about ten yards behind us, and the D Company was a further fifteen yards behind them in the support line. We were immediately ordered to make structural improvements in the trenches, which meant more digging. These trenches were not deep enough for a man to stand erect. The soldiers were tired of standing with their backs bent for extended lengths of time. The trenches were also rather narrow and we could hardly move around in them. We began using our small shovels and spades, and started digging at a steady pace, making as little noise as possible. We had hardly started digging when the sky above us was criss-crossed by enemy planes. They had been sent to monitor our progress and signal our position. Soon enough, our lines were bombarded by their artillery positions and we had to suspend our digging operations. Before we go further ahead with our story, let us take a look at the role of these aeroplanes in the war.

These aerial barques would fly high over enemy camps and their trenches, and photograph our positions to determine where the enemy was concentrated and how their lines were positioned. They would then go back and relay all the information to the base. They were, however, most deadly when they worked in conjunction with the artillery. These planes would be assigned to specific batteries; during an assault, these planes would hover above the enemy lines and relay back information on where the shells were landing. If the shells were landing at too short or too long a distance from the enemy trenches, they would immediately ask the battery to adjust its range. If they spotted a shell that had landed at the right place, they would immediately signal a ‘repeat fire’ to completely pulverize the position. Sometimes they would come in huge numbers and we would be carpeted with aerial fire. These aerial barques completely terrorized everybody in the trenches. The minute they appeared above us, we would be ordered to remain as still as possible. If we froze in our positions, it was possible that they might not spot us.

These planes were also mounted with machine guns that would merrily go ‘Bang! Bang!’ and wreak havoc on those below. Occasionally, planes from both the sides would engage each other in the skies, and this was indeed a sight to behold.

To contain these demons of the skies, a different kind of specially designed artillery known as ‘anti-aircraft guns’ would be deployed. They would keep up a relentless fire on the planes from the minute they were spotted.

Storm on a Dark Night

This being our first day in the firing-line trenches, all the soldiers were not assigned specific duties. Some of them were free while others were stationed at specific locations on sentry duty in batches. As these trenches were not deep enough for the soldiers to stand erect and peep over them to monitor the enemy’s movements, a special glass contraption was designed, which could be attached to the tip of the bayonet of one’s gun. This helped the sentry sit down and monitor the space between our trenches and those of the enemy. At short intervals, they would slightly raise their guns very carefully, and peep into the glass and see if there were any enemy advances. Every so often, German snipers would shoot at the bayonets of these soldiers with perfect aim. These German snipers were a real nuisance. At night, snipers from both sides would emerge from the trenches and shoot at the slightest movement. Besides these man-made miseries, we also had to face the fury of nature. In addition to the relentless noise of heavy guns firing through the dark night, we had to brave the most frightful thunder accompanied by incessant rain. It would rain all through the night and the trenches would be flooded. We would be standing in chest-deep water, wondering when the enemy would mount a surprise attack. Even as our boots and clothes were weighed down by the squelching mud and water, our officers would keep braying at us: ‘Beware! The enemy might attack!’ Buffeted from all sides and terrorized by the incessant guns, there were many soldiers who felt it would be far better to emerge from the trenches and take a chance with the enemy gunfire. There were others who were so paralysed by fear that they would appear almost insane and would not stir from their positions. Even if they had to answer nature’s call, they would be unable to take a single step. They would just dig a shallow hole right where they were and do their dirty business. In spite of their paralysis, they were somehow drafted to do some work by the booming orders of the officers. As mentioned earlier, the front line was manned by batches, each batch consisting of one sentry and five soldiers, with a non-commissioned officer in charge of them. They were responsible for holding the front line, and each soldier had to be on strict lookout for one hour at a time. A Lewis gun or a machine gun would be placed between every three batches. If the sentry felt that the enemy was trying to make an advance or if there was the slightest movement detected in the enemy lines, the guns would start firing. These Lewis guns played a very important role in this devastating war. These lightweight guns weighed only twenty-nine pounds and could be easily handled by one man who could move it from place to place, and when ordered, start firing at the rate of four hundred bullets per minute. Each of these guns was equivalent to a hundred rifles. We always had to be prepared at the firing line with all these arrangements.

Tear-Inducing Chilli Bombs

Indian infantry in the trenches, prepared against a gas attack [Fauquissart, France]. Dated 9th August, 1915. From the HD Girdwood collection, British Library.

After spending a miserable night in the trenches, we were shivering in our wet clothes in the morning. Suddenly we were ordered to ‘Stand to!’ Now what was this for? Even as we were wondering what it was all about, a gas that felt like chillies began pervading the trenches. Shrill orders to wear our goggles were urgently issued.

When the gas first attacked us, we could hardly understand what was happening. The gas began to envelop us from every direction and gas shells lobbed from the enemy lines were silently exploding all around us. Our eyes were in a state of extreme irritation. It felt as if they would burst.

We could hardly see anything; tears were flowing freely from our eyes, and it felt dark and terrifying. In spite of all this, everybody got into fighting position, facing the enemy lines and waiting for the inevitable attack. It was generally understood that the enemy released this gas just before it launched an attack. It rendered our soldiers blind and immobile for a brief while, and during this period, they could get the better of us and wrest our trenches. We could hardly open our eyes since the chilli gas had caused our eyes to turn red and swell up. How was a soldier to fight under such adverse circumstances? Along with this chilli gas, regular artillery fire was also kept up by the enemy, which further exacerbated the situation. To combat the nuisance of these ‘tear shells’ and to protect the eyes, a special kind of protective spectacles had been designed. They were made of ordinary glass through which everything could be seen, and the frame was fringed with flannel which ensured that the gas did not make contact with the eyes. The only saving grace was that exposure to tear gas, unlike poison gas, was not fatal; it merely left you blind for a short while.

On a Starvation Diet

Besides all the problems described above, we had yet another major problem to contend with: how to silence our hunger pangs. Soldiers on the firing line had to remain awake day and night and had no chance to lie down. To make matters worse, they had to scrounge for food. Admittedly, there was a lot of food dumped beyond the support lines as the motor transport guys would weave through the heaviest artillery fire to supply the food. Transporting the food from the dump to the firing lines was a major challenge for the soldiers. They would step out in large numbers to bring the food stuffed in small gunny bags back from the dump to the front line. The extreme conditions in the trenches, what with them being flooded with rainwater and slush, and the incessant firing of the enemy many a time prevented them from returning safely. They would be injured and fall down en route, and the food would also lie rotting there. The situation at the firing line was indeed desperate. The D Company had been assigned the support line and was responsible for supplying us with food, but as they came under heavy fire, they could not venture out of their trenches. Even though we were at the very front, the lines immediately to our rear suffered the most, bearing the brunt of the artillery fire. At least fifteen to twenty men from one company would get injured every day, and the condition of the injured was indeed very pitiable. How was food to reach us under this situation? We had to subsist on the few packets of biscuits and bully beef we had carried with us. Where was the question of getting a hot cup of tea? Not a single wisp of smoke was supposed to escape from the trenches. If the enemy spotted smoke coming from a trench, they would consider it to be a live target and fire immediately. The poor soldiers would go scrounging around for cigarette stubs.

Such was the dire situation at the front lines—starvation, mud and slush—and the relentless artillery fire had so harassed the soldiers that they were a pathetic sight to behold.

They had not shaved for days. How do you think they looked? It is best left to the imagination!

Our Final Assault

King George V inspecting Indian troops attached to the Royal Garrison Artillery, at Le Cateau on 2 December 1918. Imperial War Museums, London.

This was to be our last day at the famous Del Ville Wood. After many days of suffering and troubles, would it be too much to say that our imminent relief seemed like a new lease of life to us? Early in the morning, the news had already spread in the trenches that we were to be relieved tonight; our faces were aglow with delight. Just after noon, more authoritative news reached us, which was slightly different. We were indeed to be relieved, but we would have to perform some more arduous tasks tonight; the soldiers welcomed this news as a means of getting out of the trenches. All of us had been eagerly looking forward to being relieved for many days. Instead of spending yet another day in the slushy trenches, it was more preferable to emerge from them and show our courage in hand-to-hand combat. As per the orders issued to us, we were to launch our attack at ten in the night. Two companies were to lead the attack while the other two companies were to support us in the assault, and the trenches which we were to evacuate were to be occupied by the 4th Suffolk Regiment. All preparations had been made for a full-on artillery assault at the same time. Some of the soldiers were eagerly looking forward to the hour of the assault, while the colour had drained out of the faces of others. This supposedly minor assault was sure to claim the lives of many soldiers, but nobody knew who it would be. As things turned out, luck was on our side on this dark and evil night. It was pitch dark and the rain was falling steadily, and the roads were so slushy that they were of a porridge-like consistency. The enemy might have felt that there was very little likelihood of an attack from us in such awful weather. Our strategy was to attack under the cover of bad weather. Every minute seemed like an hour. As we waited, we could hear our hearts beating within our chests. After a seemingly eternal wait, it was finally the dark hour when we were to launch our attack. Just as orders were barked out to get us ready for the final assault, a volley of artillery fire passed over our heads towards the enemy lines. Within the blink of an eye, the Germans returned fire. Hundreds of shells were exploding loudly all around us. Their smoke darkened the skies, and we were already so scared that any enthusiasm we might have had for escaping from the trenches evaporated. Before we could think any further, orders were screamed out: ‘Over the top! Best to luck!’ The minute we heard the orders, we jumped out of the trenches and emerged into the open. We could soon hear the plaintive screams of our fellow soldiers, many of whom had fallen victim to the fire from the mortars and the machine guns. The rest of us braves, mindless of the fate of our colleagues, kept advancing. Lying flat on the ground, we crawled for over an hour and were lucky enough to finally make it to the enemy front lines. We then lobbed small bombs into their trenches and soon jumped into the trenches for a face-to-face duel. At this stage, many soldiers lost their lives to close-range enemy bullets, while some were bayoneted to death. We were able to take ten prisoners and capture one machine gun. We were about to turn back but heavy enemy artillery fire prevented us from doing so.

This was the heaviest bombardment I had ever seen, with thousands of shells exploding simultaneously all around us.

Because of the rain, mud and slush, our clothes felt like they weighed a ton. Dragging all this paraphernalia with us, a few of us were lucky enough to get back to our lines. Even as we were luxuriating in our good fortune, Lady Luck finally deserted us. A heavy shell landed just ten yards from where we were and exploded very loudly; we tried to jump away from it, but were not lucky enough to escape without being hit. I was also hit by a fragment. Even though I jumped as quickly as I could into a trench, my leg was injured in a gruesome manner. This had to happen just on the very last day when we were about to be relieved from trench duty. When fate turns against you, there is nothing you can do!

Adding Insult to Injury

Like me, there were hundreds of injured soldiers moaning and lying unattended in the trenches.

There was nobody to listen to our groans or pay any attention to us. Our troubles were just starting. If you managed to reach the dressing station, your troubles could come to an end. But in this bloody battle, it seemed like an impossibility. It was routine for hundreds of soldiers to get injured every day, and each platoon had its own stretcher-bearers who were supported by men from the Royal Army Medical Corps. For this assault, special working parties had also been formed. The firing and the destruction was, however, so severe that all these arrangements came to nought. Unlucky soldiers with stomach or leg injuries would frequently die a painful death in the trenches. If an injured soldier managed to drag himself away from the action, he stood a better chance of survival. Once you reached the dressing station, you would be one among thousands of injured soldiers crying for medical attention. The best possible care was given to them. There would be trolleys and vehicles from the Ambulance Corps to take them to the casualty clearing station. Once you reached this location, you could safely assume that your troubles had come to an end. All it needed was a cup of hot tea to make the injured soldier feel much better. After the seemingly endless days of nightmarish existence starving in the trenches, a cup of tea and the ministrations of female nurses felt like heaven. And then it was ‘Back for Blighty!’

This excerpt has been reproduced in arrangement with Harper Collins Publishers India Private Limited from the book The First World War Adventures of Nariman Karkaria: A Memoir written by Nariman Karkaria and translated by Murali Ranganathan. All rights reserved. Unauthorised copying is strictly prohibited. You can buy the book here.

ARCHIVE

Contesting Power – Contesting Memories: the Obelisk at Koregaon

The obelisk at Koregaon is characterised by a surprising commemorative history. A memorial to a bloody encounter within an imperial war, this monument provides a case study which illustrates that contestations of memories often bear the imprint of contestations for hegemony that are played out in the present.

The obelisk at Koregaon in Western India, built as a demonstration of empire builders’ belief in their own power and military prowess, serves a similar function today, but for a different group of people: the former Untouchables who had collaborated with the colonizers against what they perceived as a tyrannical indigenous regime.

The recently emerged tradition of an annual pilgrimage to the memorial, should be seen as an effort at creating and popularizing an alternative culture of the former Untouchables, now known as Neo-Buddhists. While Indian society grapples with the problem of accepting the equality of its various castes, one can witness different pathologies of memory surrounding the monument. Today, both amnesia and pseudomnesia are associated with the Koregaon memorial, defying the locus of a person in the discourse on social justice in present-day India. The memorial had faded into oblivion from British public memory long before the end of the imperial rule. However, it has undergone a metamorphosis of commemoration and now signifies something quite different from what was originally intended.

The Battle of Koregaon and its Memorial

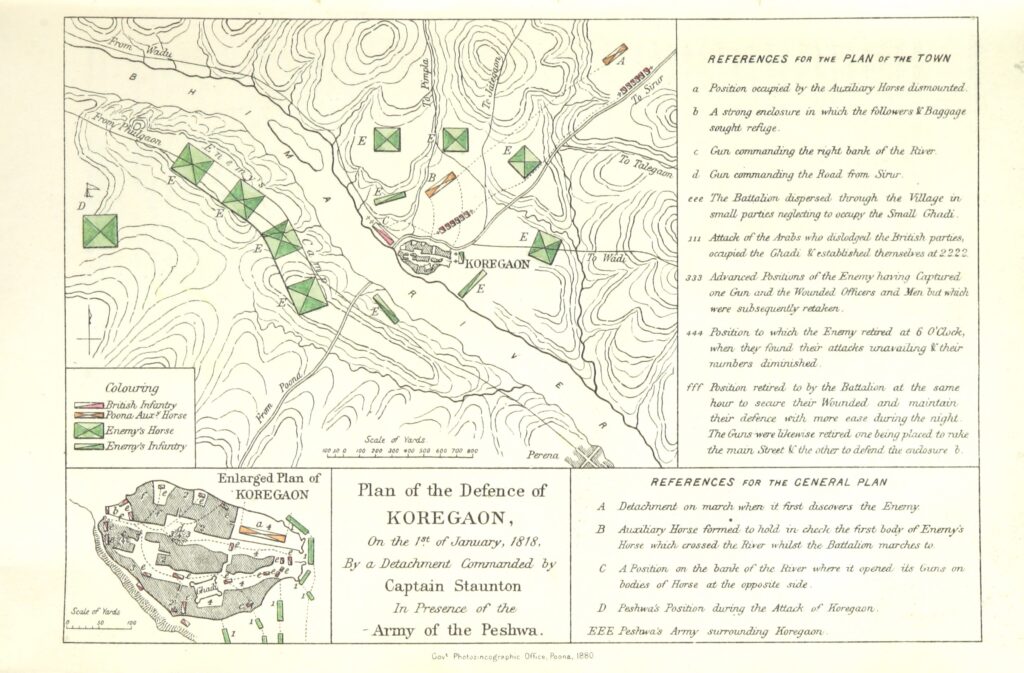

British defence plan during the Battle of Koregaon from Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency (Ed). Sir James M. Campbell, p. 259. Published in 1896. British Library.

The political ascendancy of the British East India Company in Eastern and Northern parts of India dates back to the battle of Plassey in 1757. From then on it gradually began extending its political hold to the other parts of India. During the same period, from their base in Pune in Western India, the Peshwa rulers (1707-1818) were also extending their political influence. Clashes between the Peshwas and the Company seemed inevitable. On 1 January 1818, a battalion of about 900 Company soldiers, led by F. F. Staunton from Seroor to Pune, suddenly faced a 20,000-strong army commanded by the Peshwa himself. The encounter took place at the village of Koregaon on the banks of the river Bheema. In the words of Grant Duff, a contemporary official and historian, “Captain Staunton was destitute of provisions, and this detachment, already fatigued from want of rest and a long night march, now, under a burning sun, without food or water, began a struggle as trying as ever was maintained by the British in India.” The battle was not decisively won by either side, but in spite of heavy casualties, Staunton’s outnumbered troops managed to recover their guns and carry the wounded officers and men back to Seroor.

As it was one of the last battles of the Anglo-Maratha wars, which ended with a complete victory of the Company, the encounter quickly came to be remembered as a triumph. The East India Company wasted no time in showering recognition on its soldiers.

While Staunton was promoted to the honorary post of aide de camp by the Governor General, the battle received special mention in Parliamentary debates next year. A memorial was commissioned and a year later, Lt Col Delamin, who was passing by the village, could already witness the construction of a 60-foot commemorative obelisk.

The Koregaon memorial still stands intact today. It is supposed to commemorate the British and Indian soldiers who ‘defended the village with so much success’ when the British East India Company confronted the Peshwa army in a ‘desperate engagement’. Marble plaques adorn the four sides of the obelisk. The two plaques in English are accompanied by translations into the local Marathi language. The Memorial Plaque declares that the obelisk is meant to commemorate the defence of Koregaon wherein Captain Staunton and his corps “accomplished one of the proudest triumphs of the British army in the East.” Soon after, the word ‘Corregaum’ and the obelisk were chosen to adorn the official insignia of the Regiment. In the Parliamentary debates in March 1819, the events were described as follows. “In the end, they not only secured an unmolested retreat, but they carried off their wounded!” In his volume published in 1844, Charles MacFarlane quotes from an official report to the Governor calling the engagement “one of the most brilliant affairs ever achieved by any army in which the European and Native soldiers displayed the most noble devotion and the most romantic bravery.” Twenty years later, Henry Morris confidently added: “Captain Staunton returned to Seroor, which he entered with colours flying and drums beating, after one of the most gallant actions ever fought by the English in India.” Later chroniclers of colonial rule continued to shower praise on the plucky Company force for displaying “the most noble devotion and most romantic bravery under the pressure of thirst and hunger almost beyond human endurance.” In 1885, even the ‘Grey River Argus’, a newspaper published in far-off New Zealand, described the battle in glowing terms. After the turn of the century, though, the colonial commemoration began to fade and gradually the event slipped from Britain’s public memory. The battle is now only mentioned in specialized literature on military history as an example not of British martial capabilities, but of that of the Sepoys.

Memories: ‘Ours’ and ‘Theirs’

Today the memorial finds itself just off a busy highway toll booth – a common site in the post-globalisation Indian landscape. Every New Year Day, the urban middle classes who need to use the highway, remind each other to avoid the particular stretch of the highway that passes by the memorial. Their reason for doing so is that “those people would be swarming their site at Koregaon.” Indeed, the memorial has become a site of pilgrimage attracting thousands of people who gather there every 1 January. If one asks the pilgrims what brings them together, there is a clear answer.

“We are here to remember that our Mahar forefathers fought bravely and brought down the unjust Peshwa rule. Dr Ambedkar has started this pilgrimage. He asked us to fight injustice. We have come to take inspiration from the brave soldiers and Dr Ambedkar’s memories.”

Initially, one might be baffled by this admiration for the native soldiers who fought on the British side and lost their lives in a fight against their own countrymen. A careful scrutiny of the list of casualties inscribed on the memorial reveals, however, that twenty-two names from amongst the native casualties listed end with the suffix “-nac”: Essnac, Rynac, Gunnac. The suffix ‘-nac’ was used exclusively by the untouchables of the Mahar caste who served as soldiers. This observation becomes particularly relevant when considered within the context of the caste profile of the Peshwas, who were orthodox and high-caste Brahmin rulers. The story of Koregaon is thus not just about a straightforward struggle between a colonial and a native power. There is another important but largely ignored dimension to it: caste.

Peshwa Bajirao II, who fought at the Battle of Koregaon. Coloured lithograph, Chitrashala Press, Poona, 1888. Wellcome Collection.

The Peshwas, Brahmin rulers of Western India, were infamous for their high caste orthodoxy and their persecution of the untouchables. Numerous sources document in great detail that under the Peshwa rulers, the ‘untouchable’ people who were born in certain so-called low castes were given harsher punishments than high-caste people for the same crimes. They were forbidden to move in public spaces in the mornings and evenings lest their long shadows defile high-caste people on the streets. Besides physical mobility, occupational and social mobility were also denied to these people who formed a major part of the population. Human sacrifices of ‘untouchable’ people were not uncommon under these eighteenth century rulers who had framed elaborate rules and mechanisms to ensure that the untouchables stayed just as their name suggests – untouchable. In 1855, Mukta Salave, a 15-year-old girl from the untouchable Mang caste who attended the first native school for girls in Pune, wrote an animated piece about the atrocities faced by her caste:

‘Let that religion, where only one person is privileged and the rest are deprived, perish from the earth and let it never enter our minds to be proud of such a religion. These people drove us, the poor mangs and mahars, away from our own lands, which they occupied to build large mansions. And that was not all. They regularly used to make the mangs and mahars drink oil mixed with red lead and then buried them in the foundations of their mansions, thus wiping out generation after generation of these poor people. Under Bajirao’s rule, if any mang or mahar happened to pass in front of the gymnasium, they cut off his head and used it to play “bat ball,” with their swords as bats and his head as a ball, on the grounds.’

Peshwa atrocities against the low-caste people have remained ingrained in public memory to this very day.

When the East India Company began recruiting soldiers for the Bombay Army, the untouchables seized the opportunity and enlisted. Military service was perceived as a means to opening the doors of economic as well as social emancipation. Political freedom and nationalism had little meaning for a population who had to choose between a life where the best meal on offer was a dead buffalo in the village and a life where their human dignity was respected – not to mention a decent monthly payment in cash.

While the untouchable soldiers fought on the British side against their own countrymen, the valour they showed is not at all perceived as a shameful memory today. In fact, Koregaon has become an iconic site for the former untouchables as it serves as a reminder of the bravery and strength shown by their ancestors – the very virtues that the caste system claimed they lacked. The memories related to the Koregaon memorial, help to explain how a memorial of colonial victory built in the early nineteenth century has been adapted to serve as a site that gives inspiration to the formerly untouchable people of India.

Mahars and the Military

Throughout much of the nineteenth century, the battle of Koregaon and the memorial were warmly remembered amongst military, imperial and political circles in Britain. At the beginning of the twentieth century, though, British rule was firmly established all over India, and the Koregaon Memorial faded from mainstream commemorative practices. Neither Britain at the height of colonial glory, nor India, which was beginning to receive small doses of independence, had time to commemorate the violent struggle of the days of the Honourable Company. Other lines of tradition were broken, too. The Mahar regiment had continued to demonstrate its bravery and loyalty in the battles of Kathiawad (1826) and Multan (1846). But then, in spite of the low castes’ long-standing military alliance with the British, some Sepoys from the Mahar Regiment, which formed a part of the Bombay Army, joined the “Indian Mutiny” in 1857. This added to a certain reluctance the British had always shown at the enlistment of Mahars. Subsequently, they were declared to be a non-martial race and their recruitment was stopped in May 1892.

Once their recruitment was discontinued, the Mahars soon began to feel the pinch. Gopal Baba Valangkar, a retired army-man founded a ‘Society for Removing the Problems of Non-Aryans.’ In 1894 the members of this society sent a petition to the Governor of Bombay to remind him that the Mahars had fought for the British to acquire their present dominion over India and requested a reconsideration of the decision to exclude Mahars from the Martial races, which deprived them of entry into the military service. The petition was rejected in 1896.

Another leader of the untouchables, Shivram Janba Kamble made an even more sustained effort to achieve the emancipation of the Untouchables. He had been involved in the work of the ‘Depressed Classes Mission’ which ran schools for untouchable children. In October 1910, R. A. Lamb of the Bombay Governor’s Executive Council was invited as the chief guest for a prize-giving ceremony in one of these schools. In his speech, Lamb mentioned his annual visits to the Koregaon Memorial. He drew attention to the ‘many names of Mahars who fell wounded or dead fighting bravely side by side with Europeans and with Indians who were not outcastes’ and regretted that ‘one avenue to honourable work had been closed to these people.’ It is not known whether it was Lamb’s speech that put the Koregaon Memorial back into the limelight or whether it had remained in living memory.

His words certainly lent weight to the argument that it was the Mahars who fought for the British and made them ‘masters of Poona.’

Within the first two decades of the twentieth century, Kamble organised a number of meetings of the Mahar people at the memorial site. In 1910, he arranged a grand Conference of the Deccan Mahars from 51 villages in Western India. The Conference sent an appeal to the Secretary of State demanding their ‘inalienable rights as British subjects from the British Government.’ They made a strong case for letting Mahars re-enter the army and argued that the Mahars were ‘not essentially inferior to any of our Indian fellow-subjects.’ Up until 1916 this request was repeated by various gatherings of untouchables in Western India. As the First World War gathered momentum, the Bombay government eventually issued orders in 1917 providing for the formation of two platoons of Mahars.

The Coming of Ambedkar

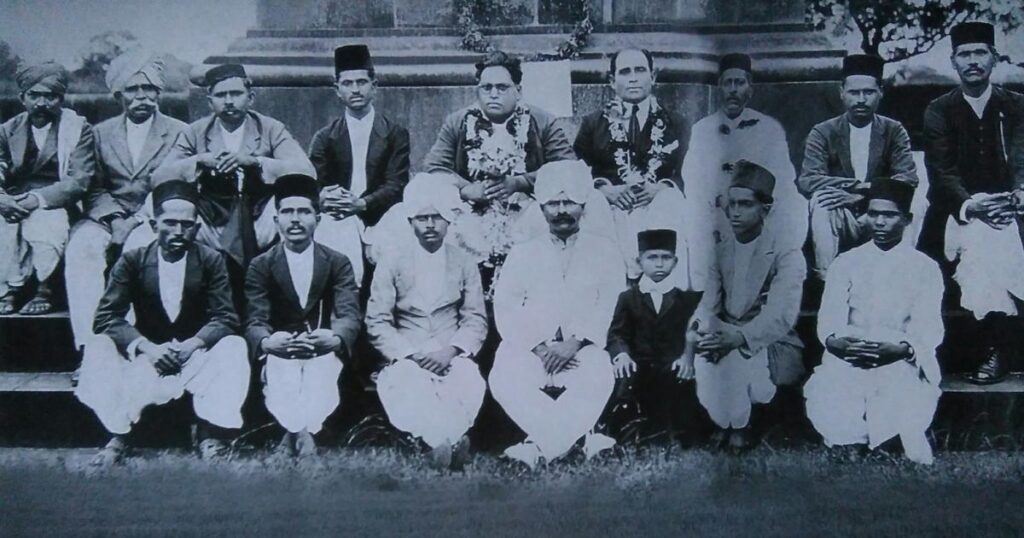

The happiness of the Mahars was, however, short-lived. Recruitment was stopped as soon as the war ended. This led to a renewed campaign for recognizing the valour of the Untouchables. By then, the demand had long since assumed the level of a movement for the general emancipation of the Untouchables. Within this campaign the Koregaon Memorial had become a focal point. Various meetings were held at the obelisk during which Kamble and other leaders invariably reminded the Untouchables of the valour and prowess exhibited by their forefathers. On the anniversary of the Koregaon battle on 1 January 1927, Kamble invited Dr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar to address the gathering of Untouchables. Ambedkar was not merely another leader of the untouchables. He was by now, as far as Indian politics was concerned, a force to be reckoned with.

Ambedkar was born in 1891, the son of a retired army subhedar from the Mahar caste. In spite of his first-hand experience of caste-based discrimination, he attained a doctorate from Columbia University, a D. Sc. from London School of Economics and was called to the Bar at Gray’s Inn by the age of 32. In 1926, he became a member of the Bombay Legislative Assembly.

He could not fail to appreciate the significance of the memorial for advancing the cause of the emancipation of the Untouchables. Not only did he make an inspiring speech at the gathering, he also supported the idea of reviving the memory of the valour of the forefathers by an annual pilgrimage to the site on the anniversary of the battle.

As a representative of the Untouchables, he was invited by the British to the Round Table Conference in 1931 where the future of the Indian Nation was to be decided. Based on his arguments at the conference, he wrote a small treatise called The Untouchables and the Pax Britannica in which he referred to the Koregaon battle to support his argument that the Untouchables had been instrumental in the establishment and consolidation of British power in India.

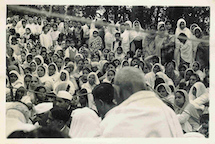

BR Ambedkar and his followers at the Koregaon victory pillar on 28 December 1927. Wikimedia Commons.

Indian mainstream politics from the 1920s until 1947 is recognised as the Gandhian era. Gandhi, having been born in the middle order caste of traders, had a different outlook on the systemic exploitation of the Untouchables on the basis of caste. He called the Untouchables Harijans, meaning people of God. Ambedkar and his followers resented both this name and the patronising attitude behind it. Underlying this surface issue, there were major ideological differences between Ambedkar and Gandhi. For the India represented by Gandhi and the Indian National Congress, the primary contradiction was that between colonial supremacy and Indians’ aspirations for political freedom. For Ambedkar and the Untouchable masses he represented, the oppression was not primarily located in the political system but arose from the socio-economic sphere. There was a clash of interests. The Indian National Congress under Gandhi sought to represent all Indians in a unified front against the colonial rule. Although Ambedkar was, unlike some “sections of Dalits and non-Brahmans who believed that colonial rule had been an unambiguous liberating force”, by no means a staunch supporter of British rule, he had quite a different new India in mind. While Gandhi saw the ideal social order arising from a reformed Hinduism, Ambedkar sought “political representation independent of the Hindu community.” In 1930, Gandhi embarked upon the Civil Disobedience Movement against the systems and institutions of the colonial rule. Kamble and a few other representatives of the depressed classes retaliated by launching what they called the “Indian National Anti-Revolutionary Party”. Its manifesto was quoted in The Bombay Chronicle:

In view of the fact that Mr Gandhi, Dictator of the Indian National Congress has declared a civil disobedience movement before doing his utmost to secure temple entry for the “depressed” classes and the complete removal of “untouchability”, it has been decided to organise the Indian National Anti-Revolutionary Party in order to persuade Gandhiji and his followers to postpone their civil disobedience agitation and to join whole-heartedly the Anti-Untouchability movement as it is… the root cause of India’s downfall…. The Party will regard British rule as absolutely necessary until the complete removal of untouchability…

Though this party did not attract much support in mainstream politics, it demonstrates that for the Untouchables, social and economic well-being was of greater and more immediate concern than political freedom, and hence colonial rule was regarded as a possibly necessary evil for the time being. It also shows that there were other and often contradictory voices in the independence movement of India. These have often been glossed over in nationalist rhetoric.

A New Memory

India won her independence in 1947, and Ambedkar chaired the committee tasked with the drafting of the new constitution. The ‘annihilation of caste’, however, remained a distant dream. The Hindu Code Bill proposed by Ambedkar in order to bring about extensive reforms in the Hindu socio-cultural scene was not accepted by parliament. In 1951 a disillusioned Ambedkar resigned from the Cabinet. Five years later, under his leadership, millions of Untouchables converted en masse to Buddhism in a step towards attaining total freedom from exploitation. The same year, after Ambedkar’s death, a political party, called the Republican Party of India, was formed to represent the interests of the low-caste people.

The conversion opened the floodgates for cultural conflicts with the high castes. The immediate reaction of the Hindu right was one of denial. The strategy of cultural appropriation that has worked so well for Hinduism from the times of the Buddha is employed even today to project the Buddhists as just another sect within Hinduism.

For the neo-Buddhists, this necessitated the creation of new and different cultural practices. Amongst the neo-Buddhists in western India one of the invented cultural practices that emerged as a result is the pilgrimage to the Koregaon Memorial. Thousands of neo-Buddhists throng to the memorial every New Year’s Day to commemorate the valour of the Mahars who helped to overthrow the high caste rule of the Peshwa. They also commemorate the visit of their leader, Dr. Ambedkar, on 1st January 1927.

Unlike any Hindu pilgrimage site, the Koregaon memorial is devoid of the tell-tale signs of a holy marketplace. No sellers of garlands and sweets and images of Gods are to be found here. It is a deserted place all through the year. However, come New Year, the place is dotted with little stalls selling books, cassettes and compact disks. Various publishers of Ambedkarite literature set up their stalls of books. Neo-Buddhist songs are played loudly in the stalls extolling the greatness of Ambedkar and emphasizing the need to change the world. Leaders of the now numerous factions of the Republican Party of India address their followers. Neo-Buddhist families visit the memorial obelisk. They offer flowers or light candles. An important part of the ritual is to offer a Vandana, a recital of verses from Buddhist texts.

An equally important element of their ritualised behaviour is the buying of books. Interviews with various booksellers have shown a surprising fact: whenever there is a gathering or a pilgrimage of the neo-Buddhists, the bookstalls do roaring business. It may be interesting to note that the average length of books sold at these stalls is short – volumes of 30-70 pages priced between 10 to 50 rupees. It might be an indication of the fact that the readers may be neo-literate, have very little time to spend on reading and can only afford cheaper books. Many publishers of related literature have indicated that their daily sales figures at the Koregaon pilgrimage and other such important pilgrimages (eg. Mumbai and Nagpur) often exceed their sales figures for the rest of the year. It could be perceived as an indication of the belief in emancipatory potential of education among the neo-Buddhists, especially of the former Mahar caste. Some of the best-selling titles include Marathi translations of books authored by Ambedkar himself, eg. Buddha and His Dhamma, Annihilation of Caste, Who Were the Shudras? Other popular books include Dalit autobiographies. They also sell Dalit poetry and small biographies of Dalit leaders.

These books offer a Dalit perspective on Indian history wherein colonial rule is portrayed as instrumental for emancipation, even though it remained ignorant of realities of caste exploitation. Jotirao Phule and Ambedkar are among the prominent Dalit writers who propounded this view of the colonial rule in which Gandhi and the movement for India’s independence do not figure very positively. The fact that Ambedkar chaired the Committee that created the Indian Constitution in 1950, however, is considered supremely important. Any attempt to criticise or seek a change in the Indian Constitution, therefore, provokes fierce opposition from the Dalit population. The anti-corruption movement led by Anna Hazare and his team in 2011 is a recent example. The extra-constitutional structure to create a powerful ombudsman (Lokpal) for resolving the issues of corruption was not welcomed by Dalit leaders and public.

The Importance of Forgetting

Though the Koregaon Memorial was constructed by the Colonial rulers, it does not feature on the commemorative landscape of today’s British public. This amnesia might be attributed to the fact that the colonial memories, especially of violent battles are no longer the object of pride in present-day Britain. This amnesia is matched by the high castes in India. Poona, the capital of Peshwas has become a software and education city called Pune. When a sample of 130 members of the high caste, newly rich people (who have come to be nicknamed as Computer Coolies) were asked about the Koregaon memorial, none of them knew what it was.

Elite amnesia is not total, though. There are also, what may be called conflicting memories. During the 1970s the Western Indian state of Maharashtra witnessed a spate of popular (a)historical novels topping the best-seller lists in Marathi. Many of them dominate the historical understanding and perceptions of the Marathi-speaking middle classes even today. Two important novels from this genre, both authored by Brahmins, describe the battle of Koregaon in passing. Mantravegla by N. S. Inamdar is based on the life of the Last Peshwa. It claims that the battle was, in fact, won by the Peshwas. Recently, this trend of creating alternative memories about the Peshwa battles has become even stronger. The battle of Panipat, which saw a complete defeat of the Peshwa armies in 1761, is commemorated today by high-sounding rallies. The kind of rhetoric used during these rallies suggests that it was the Peshwa who won the battle.

The Koregaon Memorial occupies a very significant place in today’s neo-Buddhist culture. The internet and other electronic media are used to document and commemorate the Koregaon battle and Ambedkar’s visit to it. An image search for Koregaon Pillar yields hundreds of digital pictures of the Memorial Obelisk. Film clips are available on Youtube. At least a dozen blogs in English and Marathi have entries related to the Koregaon memorial. They describe the battle and the role of the Mahar soldiers and also remind the readers about what the Untouchables could achieve if they show the resolve.

Conclusion

The obelisk of Koregaon Bheema is thus a site which has generated conflicting memories. These memories represent the divergent interests of the groups involved in their creation. Those wishing to commemorate the greatness of the Peshwa rule – the symbol of high caste supremacy – either choose to ignore the Koregaon battle, or create a Pseudomnesia of Peshwa victory. While the obelisk marks an imperial site of memory that is largely forgotten in the homeland of the empire, the monument has undergone a metamorphosis of commemoration in Western India.

It no longer reminds the public of imperial power, but for the former Untouchables whose forefathers fought at Koregaon it serves the purpose of providing “historical evidence” of the ability of the Untouchables to overthrow the high caste oppression.

Considering the fact that Indian society is still dominated by the system of caste hierarchy, the Koregaon Memorial is also a reminder that present-day contestation for hegemony is often manifested in contesting memories.

This paper has been carried out courtesy with the permission of Shraddha Kumbhojkar. It has been presented without its abstract, citations, footnotes and bibliography for purposes of easier reading.

The paper has also been published in Sites of Imperial Memory, (ed.) Dominik Geppert, Frank Lorenz Muller, Manchester University Press, Manchester, New York, 2015. as Politics, Caste and the remembrance of the Raj: the Obelisk at Koregaon. You can buy the book here.

ARCHIVE

The Presence of the Shramanas

Let me now turn to my second and rather different example: an existing culture gives rise to an alternative Other from within itself. The Other here was not regarded as being of an alien culture but, evolving out of a similar culture, was nevertheless dissenting from the codes of dominant groups. I am taking you now into the early ADs, to the emergence of groups that were a different Other and were jointly called the Shramanas—these were the Jainas, Buddhists and Ajivikas. Some would include the Charvakas / Lokayatas as well, although their thinking was very different.

The teachings of the Shramanas revolved round each of their historical founders. The Buddhists, for example, accepted the Buddha, the dhamma / dharma and the Sangha as the pillars of their teaching. They had fewer elaborate public rituals and used discussion or texts when stating their principles. They had a few demarcated places of worship, the chaityas and stupas. The latter held the relics of the venerated dead, contrary to Vedic practice.

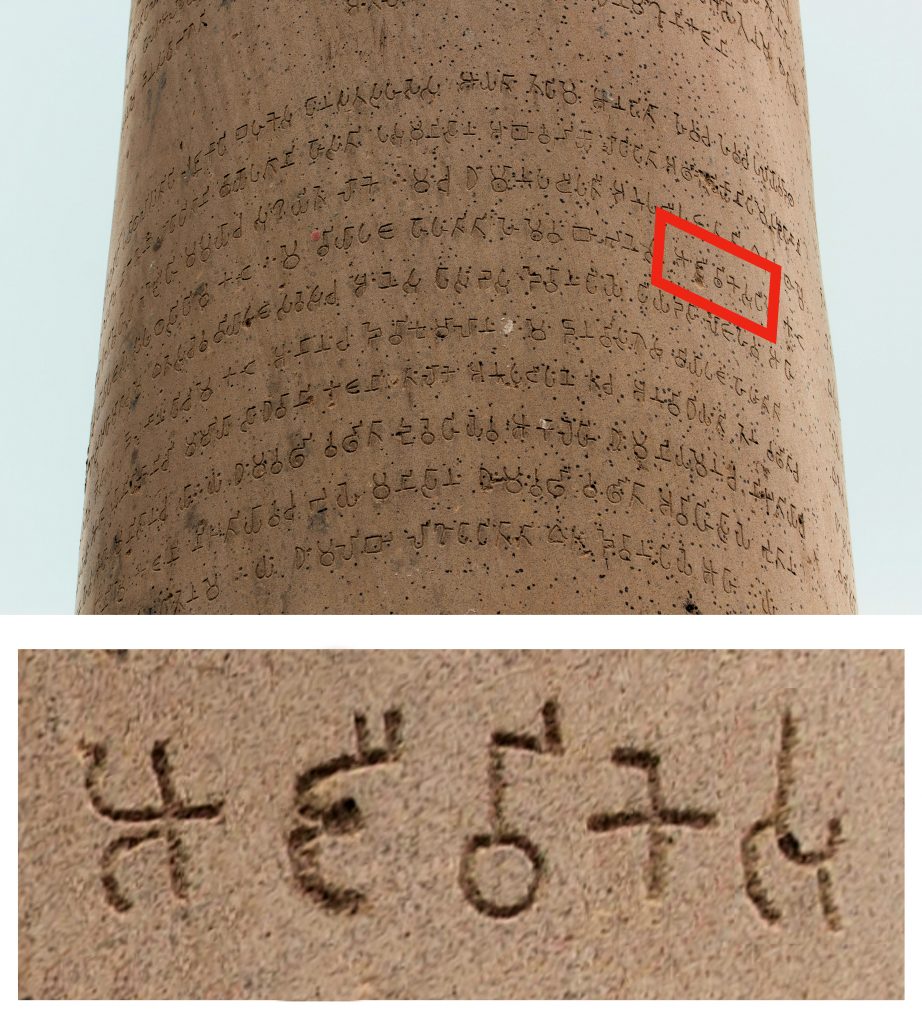

Mention of the Ajivikas on the Ashoka pillar, Feroz Shah Kotla, Delhi.

The question of ahimsa / nonviolence was central to the teaching of the Buddhists and Jainas. This was not so in the texts endorsed by Brahmanism nor in its rituals of sacrifice. It became a matter of debate, as is reflected in various texts such as the Mahabharata and the Bhagavad-Gita. Where violence is permitted if it is against evil, as in the Gita, the issue becomes somewhat ambivalent. Who decides that certain actions are evil and opposed to the code of ethics—the Self or the Other? (I shall refer to this discussion again later.) The Buddha’s emphasis on karuna / compassion reflects what was being said about this by various teachers. The emphasis on ahimsa is underlined more frequently in Shramanic teaching than in the other. Of the Vedic corpus, the Upanishads are perhaps more open to these discussions.

The Charvakas were not Shramanas and on occasion their views conflicted. They not only denied the existence of deity but extended this denial to all that cannot be verified. Atheism, rationalism and the need to question was not heresy, it was a right exercised by thinking people. The search was for explaining the real world. We are responsible for our actions and are aware of the consequences. These occur in this life as there is no rebirth. Rituals were rejected and dismissed. A number and variety of such groups debated these ideas and the liveliness sometimes led to entanglements of thought. That is why the Buddha referred to some among them as ‘eel-wrigglers’.

The Shramanas were opposed in varying degrees to Vedic Brahmanism. They questioned the belief in deities, in the Vedas being divinely revealed, in the efficacy of the yajna / ritual of sacrifice, and in the existence of the individual soul or atman. Brahmanical literature refers to the Shramanas categorically as nastika, the non-believers, the astika being the believers. This duality of belief and non-belief remained fundamental to the Brahmanical view of itself and of non-brahmanical religions. It should be differentiated from other dualities in Indian thought. As a term for non-brahmanical belief and practice, nastika continued to be used through the centuries. The concept was not limited to religious thought and it would obviously have carried a social message as well. If deity could be doubted, then so could the laws that were made in the name of the deities as well as the claim of communication between men and gods.

The Shramanas were opposed in varying degrees to Vedic Brahmanism. They questioned the belief in deities, in the Vedas being divinely revealed, in the efficacy of the yajna / ritual of sacrifice, and in the existence of the individual soul or atman. Brahmanical literature refers to the Shramanas categorically as nastika, the non-believers, the astika being the believers. This duality of belief and non-belief remained fundamental to the Brahmanical view of itself and of non-brahmanical religions.

These opposed ideologies underwent many changes as they meandered their way through history. The persons associated with the founding of the more important Shramana religions were from the upper castes, as were many initial followers. Shramanism was open to lower castes who could become lay followers and monks. Rituals were less dramatic than the Vedic ones and were not tied to caste status. Abiding by caste norms was not a criterion of admission to their ranks and the existence of caste was not essential to their teaching. Their dissent was more in the nature of opposing beliefs rather than restructuring society, although the latter was not marginal to their thinking and some restructuring was inevitable. The continuance of caste could be problematic since social ethics was implicit to Shramanic thinking. However, even for the post-Vedic formal religions that evolved around Shaivism and Vaishnavism, the Shramanas were the nastika Others. That Puranic religion was facing a threat is apparent from the mention in the Puranas of dissenters who question the Vedas through false arguments and who can be recognized by their red robes, a reference to the robes worn by the shramana monks.

Apart from their differences of belief religious sects were competitors for royal patronage in the form of donations to their institutions and later there were grants of land to maintain these institutions. Patronage kept the Shramana sects going and gave them a place in society. The competition would doubtless have added to the ideological hostility. The patrons of the shramanas included a large segment of society such as householders owning land or gahapatis, and wealthy merchants or setthis, mercantile guilds and craftsmen and their families, apart from the gradually increasing royal patronage. Their popularity extended to wider levels of society and that would doubtless have added to their ideological differences with Brahmanism.

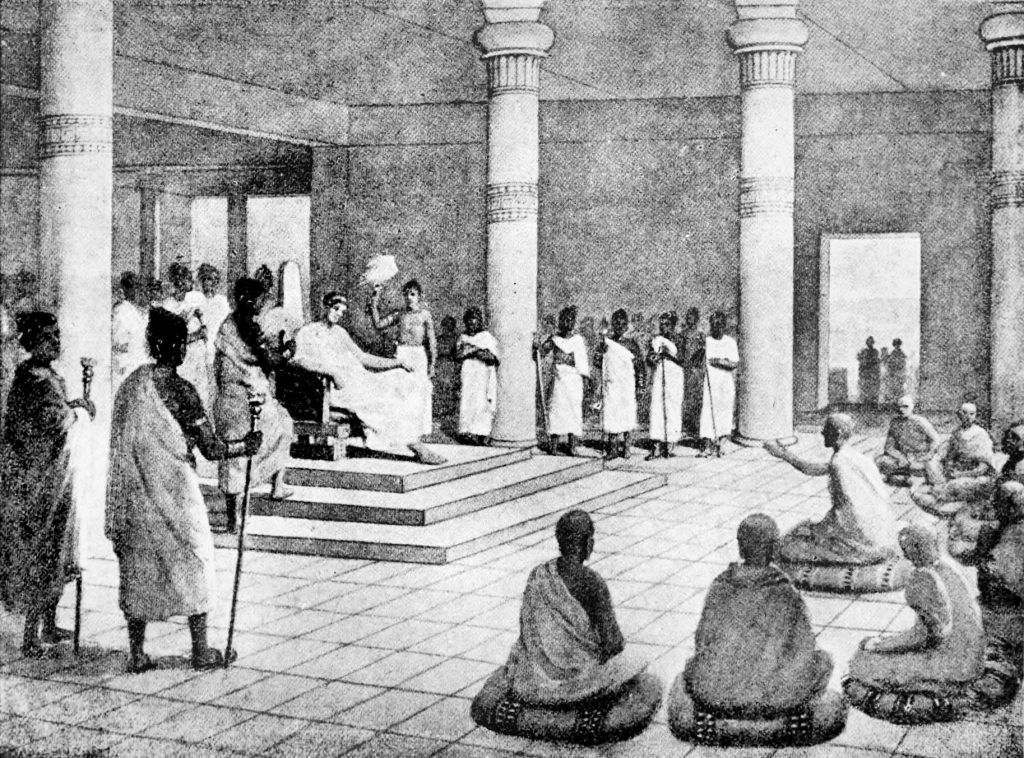

Ashoka’s visit to the Ramagrama Stupa; relief from the Sanchi Stupa.

Various historical sources refer to two streams of what might be called religion, two dharmas visible on the historical scene. To list a few here: Megasthenes visited Mauryan India in the fourth century BC, coming from the neighbouring Hellenistic Seleucid kingdom in West Asia. He wrote an account of his visit, the Indika. In this he speaks of the seven castes of Indian society of which the highest is divided into two: the Brachmanes and the Sarmanes / the Brahmanas and the Shramanas. The Shramanas, described as philosophers, are not included among the Brahmanas but are listed as distinctive and separate. The edicts of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka issued in the third century BC make repeated pleas for harmony between the various sects. These are often included in the compound phrase in Prakrit bahmanam-samanam when speaking of the sects. The Sanskrit grammarian Patanjali, writing just before the Christian era, compares the antagonism between the brahmana and the shramana to that between the snake and the mongoose.

Various historical sources refer to two streams of what might be called religion, two dharmas visible on the historical scene… Megasthenes visited Mauryan India in the fourth century BC, coming from the neighbouring Hellenistic Seleucid kingdom in West Asia. He wrote an account of his visit, the Indika. In this he speaks of the seven castes of Indian society of which the highest is divided into two: the Brachmanes and the Sarmanes / the Brahmanas and the Shramanas. The Shramanas, described as philosophers, are not included among the Brahmanas but are listed as distinctive and separate. The edicts of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka issued in the third century BC make repeated pleas for harmony between the various sects. These are often included in the compound phrase in Prakrit bahmanam-samanam when speaking of the sects. The Sanskrit grammarian Patanjali, writing just before the Christian era, compares the antagonism between the brahmana and the shramana to that between the snake and the mongoose.

That the differentiation between the two increased over the centuries is apparent from a text that evokes the idea of a conversion to the Buddhist dhamma. Nagasena, a Buddhist monk claims to be recording his conversation about Buddhism with the Indo-Greek king Menander in his text Milinda-panho / The Questions of King Menander. The questions posed and the answers given are fascinating in as much as they draw variously on belief and rational argument. So far no comparable text has been found from the Brahmanical tradition. Perhaps this illustrates one of the fundamental differences between the two in their approach to religion. The brahmana would have regarded Menander as a mleccha and kept him away from participating in the rituals or would have had to bestow upper-caste status on him, whereas the Buddhist was anxious to recruit him as he was, as a Buddhist lay follower.

‘King Milinda (Menander) Asks Questions’; sketch from Hutchinson’s Story of the Nations (published before 1923).

Clearly, there were by now many sects with dissenting views. No religion was uniformly observed, nor was it strictly monolithic in its teaching. The two significant traditions of thought are frequently referred to in the sources. This is further confirmed in the early Puranas where hostile remarks on the Shramanas indicate the antagonism between the two. Al-Biruni describes the Brahmana religion at length but also mentions those that are opposed to it as the Sammaniyas.

In the period between the Mauryas and the Guptas, there is a striking presence of impressive Buddhist stupas, and an equally striking absence of temples, a situation that was slowly reversed in the subsequent post-Gupta period. Religious buildings are among the indicators of patronage and popularity. It was a time of intense social change with clan societies giving way to caste societies and many kingdoms being established in areas where earlier there had been clan assemblies, or minimal governmental control, or even none at all. Possibly, it could be said that it was a period when the Shramanas were the more established Selves as it were, and the emerging Puranic Hinduism was a competitor— a position that was reversed in the post-Gupta period. Was the Buddhist Dhammapada facing the dharmashastras of Brahmana authorship more centrally than before? The vision of universal concerns was being slowly recast into the restricted concerns of a caste-bound society.

It was subsequent to this that the Buddhists and Jainas, described as heretics and dissidents in the Puranas of the early centuries AD, began to experience persecution. It seemed to coincide with increasing royal patronage being bestowed on brahmanas. The hostility of Shaiva sects against the Shramanas finds mention, whether in Kashmir or in Tamil Nadu. Buddhist monks and monasteries were attacked in Gandhara as stated in the Rajatarangini of Kalhana, and Jaina monks met a similar fate elsewhere. Why this was so has still to be convincingly explained. Was it just a conflict over patronage between the Puranic and Shramana religions?

The Sanchi Stupa.

In the period between the Mauryas and the Guptas, there is a striking presence of impressive Buddhist stupas, and an equally striking absence of temples, a situation that was slowly reversed in the subsequent post-Gupta period… Possibly, it could be said that it was a period when the Shramanas were the more established Selves as it were, and the emerging Puranic Hinduism was a competitor— a position that was reversed in the post-Gupta period… It was subsequent to this that the Buddhists and Jainas, described as heretics and dissidents in the Puranas of the early centuries AD, began to experience persecution. It seemed to coincide with increasing royal patronage being bestowed on brahmanas… Buddhist monks and monasteries were attacked in Gandhara as stated in the Rajatarangini of Kalhana, and Jaina monks met a similar fate elsewhere. Why this was so has still to be convincingly explained. Was it just a conflict over patronage between the Puranic and Shramana religions?

The Shramana religions were facing their own internal divisions. Buddhism was split into two major schools— the Mahayana / Greater Vehicle, and the Hinayana / Lesser Vehicle. The former had a marked presence in north-western India and Central Asia. Innumerable sects emerged and, based on belief and practice, were connected loosely or firmly to the school of their choice. In subsequent centuries, further schools were added, such as the Vajrayana, influenced by the Tantric religion.

Buddhism tended to be active in a few pockets and more so in eastern India, although for a shorter period. It gradually faded from being foremost among the Shramana religions having conceded ground to the idea of deity and related practices. Its decline was furthered by other socioeconomic changes. A decline in commerce doubtless affected its patronage as did the diversion of royal donations elsewhere. The argument that Islam dealt a death-blow to Buddhism in India is untenable since Buddhism had ceased to be pre-eminent even before the coming of Islam to North India. This is suggested by the assessment of the seventh-century AD Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang, who travelled widely in India and eventually spent a few years studying in Nalanda.

Portrait of Xuanzang (Genjō) with Attendant, 14th Century.

As a contrast to Buddhism’s quietude in India, this was the period when it had a spectacular following in most parts of Asia. Buddhist missionary activity marked a major difference from other Indian religions that tended to be stay-at-home. Buddhist monks pioneered missions to Central Asia in the early centuries AD, travelling with the merchants active in establishing trade links along many routes that have come to be called the Silk Routes. They also travelled along the maritime trade routes through South-East Asia. Curiously, Puranic Hinduism that also did a modicum of travelling at this time, and through the same channels as Buddhism, remained a marginal religion if at all in most places. In South-East Asia it offered some competition initially but eventually gave way to Buddhism.

The Jainas survived perhaps by consolidating their patronage and rooting themselves in specific areas such as Karnataka and Western India, supported substantially by the wealthy mercantile community and occasionally by royalty. The teaching was largely split into two major schools, the Digambara and the Shvetambara, each with many sects. Their monasteries became centres of scholarship focusing on their own teaching and thus forming a kind of counterpart to the mathas of the brahmanas. Many had a proficiency in accounting and finance that linked them to the commercial activities of those times and to the lives of trading communities. Possibly some concession was made here or there in ritual and worship, as in the spectacular temples they built, that indicated their well-being. This again has to be examined.

Among the philosophical Others that we often dismiss were the materialist philosophers of the Charvaka teaching. They are neglected because of our obsession with the idea that India has only respected non-materialist philosophies in the past. Unfortunately, there is no surviving text of major significance that they authored on their philosophy, much of it being taught orally. Had there been some texts, then they would have been given greater space. There are, however, references to them and summaries of their teachings in diverse texts. Some regard the Arthashastra as a text that shows traces of Charvaka thinking. This may be because Kautilya underlines the importance of critical enquiry, with an emphasis on tarka / logic. This may suggest that dissent was latent in various schools of Indian thought and we have to be more sensitive to its presence.

In the Mahabharata, a rakshasa named Charvaka upbraids Yudhishthira on the futility of the killing that resulted from the battle at Kurukshetra. He is silenced when he is himself killed by the brahmanas present. Buddhist texts were also not, on the whole, friendly towards the Charvakas, even though the teaching of both was opposed to that of the brahmanas. Gradually, there developed a tendency for Brahmanical texts to list the non-Brahmanical schools altogether in one list and describe them all as nastika / non-believers.

Sarva-darshana-samgraha

However, it would seem that Charvaka thinking was present through the centuries to medieval times. A compendium of current fourteenth-century philosophies, the Sarva-darshana-samgraha, written by Madhvacharya, a philosopher of the time, has as its opening chapter a discourse on Charvaka philosophy. The author explains that although he himself did not agree with its arguments, it was nevertheless a known school of thought. This suggests that the philosophy of materialism was present both among philosophers and others. We are also told that when Emperor Akbar invited representatives of various philosophical schools, the Charvakas were one among them. We need to restore them to their rightful place in our assessment of the philosophical spectrum in Indian thought. Even if this is not stated directly, they are likely to have been in dialogue with the other streams, else they would have faded out before the fourteenth century. Of the two main streams, the dialogue of the Charvakas would more likely have been with the Shramanas.

Among the philosophical Others that we often dismiss were the materialist philosophers of the Charvaka teaching. They are neglected because of our obsession with the idea that India has only respected non-materialist philosophies in the past. Unfortunately, there is no surviving text of major significance that they authored on their philosophy, much of it being taught orally… We need to restore them to their rightful place in our assessment of the philosophical spectrum in Indian thought. Even if this is not stated directly, they are likely to have been in dialogue with the other streams, else they would have faded out before the fourteenth century.

So much by way of a very brief sketch of the background.

Dissent that uses the idiom of religion, as did many pre-modern dissenting groups, did not confine itself to writing dissenting texts. It is not enough to look only at the texts that resulted from conflicting ideas, although this is a necessary step. These provide some of the explanation that gave rise to dissent. It is equally important to study the institutions that religious groups built to support their activities and through which conformity or dissent was expressed. In some instances, these had more than a marginal role in formulating either the one or the other. I shall refer to just a few examples to illustrate the point.

The Shramanas established a new personality on the social landscape—that of the renouncer. This entity occasionally took on the characteristics of a counterculture. It was a new kind of Other. The renouncers as monks lived separately in their own institutions—the monasteries that were sometimes identified by sect. They were dependent on society for alms, mainly food. They broke the rules of caste by being celibate, by eating cooked food given by anyone irrespective of caste, and (in theory at least) by not segregating the savarna, those belonging to a varna / caste, from the avarna, those without a varna identity. The well-established sects among these intervened in politics and social concerns although claiming to be focused on religion, a situation that continues to this day in the nexus between many religious sects and politics and in the political activities of religious organizations. Patronage is frequently the link. The renouncer opting out of society but claiming to have the welfare of society as his concern acquires a degree of moral authority within society, and this can increase in accordance with his teaching and activity. This was a feature of pre-modern times and, as we shall see, is not unknown to modern times as well.

In order to maintain the institutions of the renouncers, the granting of land and large donations towards their maintenance continued. It enabled them to become powerful social and political institutions but their role as Others gradually diminished. Donations to brahmanas as individuals or as groups or as institutions helped in building up a strong religious base for Brahmanism, as had earlier been so for Buddhism. The institutionalizing of a religion inevitably gives it a certain control over secular functioning. It subsumes the secular into the religious authority. The multitude of inscriptions from the late first millennium AD recording grants of land and wealth donated to brahmanas gave to Brahmanism a larger political and economic status than merely the role of ritual specialists conducting Vedic sacrificial and other rituals, building temples and worshipping icons placed therein. Inevitably the religion itself underwent a shift.

The success of Brahmanism in unsettling the Shramanas was in part due to brahmanas now receiving a large share of patronage. Royal patronage to Vedic Brahmanism continued but had also to adjust to the growing demands of the institutions of a form of Hinduism that might be better referred to as Puranic Hinduism. This was the worship of various manifestations of Vaishnavism and Shaivism to begin with and later included the Shakta-Shakti and other cults. Within these larger assemblages were included on occasion some local deities inducted into the Puranic pantheon. When this happened, the ritual specialists either became a separate caste category or were drawn into the brahmana caste. Evidence of this is more common after the Gupta period. In some ways it is minimally reminiscent of the brahmana sons of dasis being given brahmana status. Local deities could be from another tradition, but if it was expedient to induct them into Puranic Hinduism, it was done.

Dissent that uses the idiom of religion, as did many pre-modern dissenting groups, did not confine itself to writing dissenting texts. It is not enough to look only at the texts that resulted from conflicting ideas, although this is a necessary step. These provide some of the explanation that gave rise to dissent. It is equally important to study the institutions that religious groups built to support their activities and through which conformity or dissent was expressed.

In fact, Puranic Hinduism, although it invokes Vedic Brahmanism, was in many respects distinct. Some of its major features suggest a reaction to the competition with Shramanism. This would be an example of dissent helping to engineer a new formulation of an existing religion. Its texts were the Puranas, composed in a more widely spoken Sanskrit than the now-rather-archaic Vedic Sanskrit of the Vedas, and in later centuries even more in local languages. The study and recitation of the Vedas was restricted to appropriate people, but the Puranas were recited and made familiar to popular audiences. Unlike the major Vedic sacrificial rituals that were not associated with the worship of idols and could be performed wherever thought suitable, and whose locations were disbanded at the conclusion of the ritual, Puranic Hinduism now began building permanent places of worship, namely, temples housing images of deities with an increasing focus on their worship, and accompanying the changes in the religion. These innovations are reflected in the late dharma-shastras where, for example, there is a discussion on which brahmana is to be given priority—the one who is a specialist in the Vedas or the temple priest.

Beginning as places housing icons being worshipped, temples were to gradually become immensely large and complex institutions supported by the offerings of the worshippers and the donations of land and money by wealthy patrons. All this had to be administered by a large body of priests. They also became major places of pilgrimage, and with gatherings of people from a variety of places, they doubled up as commercial centres that in turn gave them an added economic importance.

Buddhist Vihara, Nalanda University.

The Shramanas had their institutions that impinged on society in the form of viharas / monasteries, chaityas / halls of worship and stupas / relic mounds. Puranic Hinduism had its institutions that were entirely different in the form of temples and of mathas / centres of textual religion and learning. That religious institutions were extending their reach over the socioeconomic and political activities of the time becomes evident. This brought about a change from earlier times in the inter-relation between religion and society. It was no longer limited to religion providing a path to worship, since it now extended to religious institutions intervening in the activities of society. Patronage was absolutely crucial to the continuance of these socio-religious institutions.

There was a gradual shift in patronage, especially among royal families with greater support going to the brahmanas who by now were increasingly the authors and the ritual specialists of Puranic Hinduism. Two obvious factors might explain this change. The brahmanas could supply the upstart dynasties with lineage links to ancient kshatriya genealogies to legitimize their being called the new kshatriyas as many were; and the claim of the brahmanas that they could perform effective rituals to avert evil and bad luck in order to ensure the continuous and successful rule of these dynasties.

Coinciding with this, patronage from wealthy merchants and guilds to the Shramana institutions possibly declined in this period when there was a fall in trade and wealth to donate was not easily available. Monasteries and trading groups had a close connection with the former, sometimes as participants in commercial activities. Changes in the volume of trade would therefore decrease the patronage available to monasteries and thereby curtail their activities.

Puranic Hinduism, although it invokes Vedic Brahmanism, was in many respects distinct. Some of its major features suggest a reaction to the competition with Shramanism. This would be an example of dissent helping to engineer a new formulation of an existing religion. Its texts were the Puranas, composed in a more widely spoken Sanskrit than the now-rather-archaic Vedic Sanskrit of the Vedas, and in later centuries even more in local languages. The study and recitation of the Vedas was restricted to appropriate people, but the Puranas were recited and made familiar to popular audiences. Unlike the major Vedic sacrificial rituals that were not associated with the worship of idols and could be performed wherever thought suitable, and whose locations were disbanded at the conclusion of the ritual, Puranic Hinduism now began building permanent places of worship, namely, temples housing images of deities with an increasing focus on their worship, and accompanying the changes in the religion.

Nevertheless, this period saw substantial scholarship both among the shramanas and the brahmanas in a remarkable articulation of philosophical ideas. Given that the premises of each were so different, there was naturally much debate that drew on both orthodoxy and dissent. Dissent was not restricted to the instituting of renunciatory orders. It also focused on the discussion of philosophical ideas. Debates were known to take place at royal courts, as, for instance, at that of Harshavardhana, the seventh-century ruler of Thanesar-Kanauj. Among the well-known philosophers of around that period were Dignaga and Dharmakirti. Subsequently, the practice is associated with Shankaracharya and others.

Even within what may broadly be called the different Shramana traditions, there evolved a large range of sects that differed among themselves and asserted a degree of autonomy. The differences focused on the interpretation of the teachings of the founders, on the rules of the monastic orders, and on the precepts required to be observed by lay followers. Such differences could be theological in origin or more often due to a changing historical context.

For instance, when the money economy gained currency in early times, an obvious question arose as to whether monks could accept donations of money, and this was one of the causes of a rift in the early Buddhist Sangha. Later when patrons and donors included more than just the lay following and registered gifts from diverse categories such as royalty and mercantile interests, the particular requirements of each of these categories had to be accommodated. Large donations of land generally from royalty led to what Max Weber described as monastic landlordism. This was counter to the rule that the monastery should not own property, and more so when the landed property was so large that it required the monks to do administrative work and supervise the labour employed to work the land. In such situations, the monastery was also a socioeconomic institution not entirely divorced from political connections. As such its nurturing of dissent might have been muted. The imprint of having to administer landed property would also have altered the patterns of living in the mathas and agraharas of the brahmanas, not to mention the richly endowed temples. Not all brahmanas could spend their time studying the texts, for some among them had to supervise the farming and its ancillary produce and some others had to keep the accounts in order. The monks of the monasteries were familiar with these procedures.

From the mid-first millennium AD, the Shramanic religions were not invariably dissenting groups in relation to the increasingly well-endowed Puranic Hinduism. By this time, they had evolved both their own orthodoxies and their own dissenting ideas and practices vis-à-vis these orthodoxies. The survival of these varied.

From the mid-first millennium AD, the Shramanic religions were not invariably dissenting groups in relation to the increasingly well-endowed Puranic Hinduism. By this time, they had evolved both their own orthodoxies and their own dissenting ideas and practices vis-à-vis these orthodoxies. The survival of these varied.

Virtually every religion in India consisted by now of multiple sects, each seeking its own patronage and asserting its identity. This pattern was applicable to later religions as well. Having an institution and an identity helped in locating it in the gamut of sects and this allowed it to be characterized as conforming to or dissenting from, or locating itself somewhere in-between the original teaching and its variant. The feasibility of differences and their coexistence was recognized, although some among them faced animosity and conflict. But in either case, the relationship between sects, whether friendly or hostile, was confined to small, local groups. A single, uniformly applicable, overarching religion was unfamiliar. Nor was there a single sacred overarching text even for what might be taken as a formal religion. A canon was recognized by some of the followers but no text was singled out as unquestionably the single and most sacred one over and above all others. This made the localization of religious practices and ideas far stronger than the somewhat abstract loyalty to an overarching single text.

Later when attempts were made to write on past events linked to the religion, these tended to be potted histories or documented recalls of the sect rather than a story of the larger religion. Even where they began with the larger story, they moved into the particulars of the sect. The Shramana religions had better documentation on their pasts but this may have been because they were rooted in the thoughts of a historical founder, and they were initially dissident groups that made it a point to construct and recall the past, perhaps in part to give themselves legitimacy. One of the purposes of claiming a history is to claim legitimacy. Today, however, we require that the history not be a casual narrative, but be such that it draws on reliable evidence for supporting the claim.