ARCHIVE

The Battle of the Somme

Nariman Karkaria

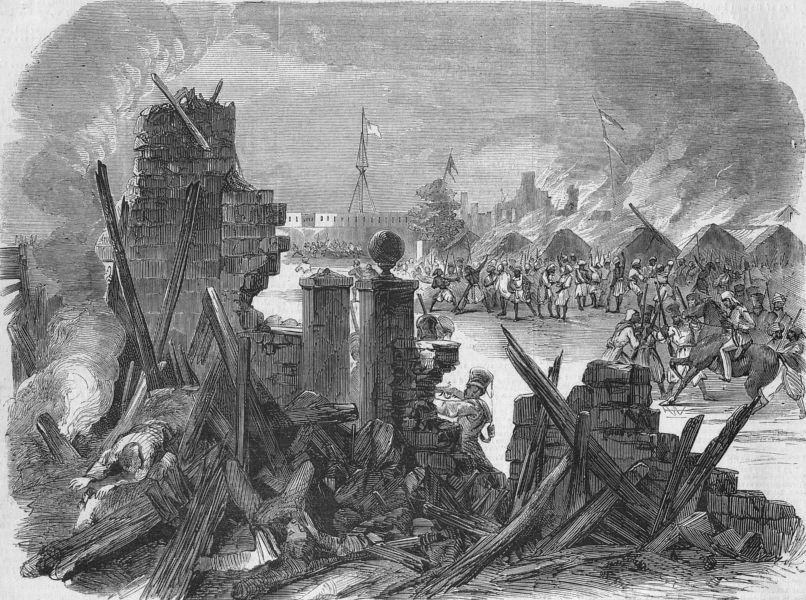

At last, it was our turn to see action, something we had been waiting for with our eyes peeled. Some of the soldiers were very eager to see the Germans in person and flaunt their muscle power, while quite a few were most distressed by the orders to advance forward to the front lines. We were to participate in the Battle of the Somme, which has already achieved legendary status in the Great War.

The Role of the Indian Army

Indian bicycle troops at a crossroads on the Fricourt-Mametz Road, Somme, France. Dated July 1916. From the collection of Imperial War Museums, London.

The Indian Army also took part in the Battle of the Somme.

The Bengal Lancers advanced under heavy fire from the Germans right up to the German trenches and forced them to retreat. On this occasion, our platoon was ordered to advance to the firing line. Our undercover march started at about one o’clock in the night. We had been strictly warned not to utter a single word. With great difficulty, we managed to advance, digging a few trenches and walking all through the night, only to find ourselves in a very unfortunate position in the morning. A German observation balloon which had been flying above us had spotted us, and very soon our route came under heavy fire. Shells were exploding all around us. To escape them, we would lie flat on the ground for a short while before running to advance a little forward. A wave of fear rippled through our platoon. Soldiers were falling all around us with piteous shrieks, but there was nothing that could be done. Each man was on his own and could not be bothered about anybody else. Others would advance by stepping on those injured soldiers who had fallen to the ground. We had no option but to move forward. We also had no idea what kinds of difficulties we were to face as we advanced. Many of our men were lagging behind, but we could not wait for them, and at about twelve noon we reached the famous jungles of Del Ville Wood where we felt we could finally heave a sigh of relief. But fate had other things in store for us. There were no trenches beyond the next twenty-five yards from where we were located. We could not step out of the trenches as we would have been sitting ducks for German guns. The Germans were hardly at any distance from where we were—say about a hundred yards away in their trenches. In spite of this situation, the Commanding Officer gave orders to advance further. We had no option but to run, and we ran in pairs. We would advance about ten steps before throwing ourselves flat on the ground. Our progress did not last very long. Soon enough, the enemy started firing at us with their machine guns.

We were staring death in the eye. But as luck would have it, there had been a fierce battle on this very site just four days ago, and the bodies of dead soldiers were lying all around us. These corpses proved very useful in sheltering us from the enemy gunfire. As we advanced, we would lie behind these corpses, and they would act as our shield taking all the gunfire. Ah, what a terrible experience! Just one bullet and we would also have joined the army of cold corpses!

War in the Skies

After a very desperate battle and the loss of over fifty soldiers, we were lucky enough to be able to take possession of the trenches. Because of the non-stop action during the night and the better part of the day, we had not even had a cup of tea, much less anything to eat. I had managed to eat a couple of biscuits while moving forward. This was all I had had, with which I had to be content for the whole day. Once we took possession of the trenches, the different companies of the platoon were immediately assigned positions. While the A and C Companies were assigned the forward trenches, the B Company was assigned the communication line, which was about ten yards behind us, and the D Company was a further fifteen yards behind them in the support line. We were immediately ordered to make structural improvements in the trenches, which meant more digging. These trenches were not deep enough for a man to stand erect. The soldiers were tired of standing with their backs bent for extended lengths of time. The trenches were also rather narrow and we could hardly move around in them. We began using our small shovels and spades, and started digging at a steady pace, making as little noise as possible. We had hardly started digging when the sky above us was criss-crossed by enemy planes. They had been sent to monitor our progress and signal our position. Soon enough, our lines were bombarded by their artillery positions and we had to suspend our digging operations. Before we go further ahead with our story, let us take a look at the role of these aeroplanes in the war.

These aerial barques would fly high over enemy camps and their trenches, and photograph our positions to determine where the enemy was concentrated and how their lines were positioned. They would then go back and relay all the information to the base. They were, however, most deadly when they worked in conjunction with the artillery. These planes would be assigned to specific batteries; during an assault, these planes would hover above the enemy lines and relay back information on where the shells were landing. If the shells were landing at too short or too long a distance from the enemy trenches, they would immediately ask the battery to adjust its range. If they spotted a shell that had landed at the right place, they would immediately signal a ‘repeat fire’ to completely pulverize the position. Sometimes they would come in huge numbers and we would be carpeted with aerial fire. These aerial barques completely terrorized everybody in the trenches. The minute they appeared above us, we would be ordered to remain as still as possible. If we froze in our positions, it was possible that they might not spot us.

These planes were also mounted with machine guns that would merrily go ‘Bang! Bang!’ and wreak havoc on those below. Occasionally, planes from both the sides would engage each other in the skies, and this was indeed a sight to behold.

To contain these demons of the skies, a different kind of specially designed artillery known as ‘anti-aircraft guns’ would be deployed. They would keep up a relentless fire on the planes from the minute they were spotted.

Storm on a Dark Night

This being our first day in the firing-line trenches, all the soldiers were not assigned specific duties. Some of them were free while others were stationed at specific locations on sentry duty in batches. As these trenches were not deep enough for the soldiers to stand erect and peep over them to monitor the enemy’s movements, a special glass contraption was designed, which could be attached to the tip of the bayonet of one’s gun. This helped the sentry sit down and monitor the space between our trenches and those of the enemy. At short intervals, they would slightly raise their guns very carefully, and peep into the glass and see if there were any enemy advances. Every so often, German snipers would shoot at the bayonets of these soldiers with perfect aim. These German snipers were a real nuisance. At night, snipers from both sides would emerge from the trenches and shoot at the slightest movement. Besides these man-made miseries, we also had to face the fury of nature. In addition to the relentless noise of heavy guns firing through the dark night, we had to brave the most frightful thunder accompanied by incessant rain. It would rain all through the night and the trenches would be flooded. We would be standing in chest-deep water, wondering when the enemy would mount a surprise attack. Even as our boots and clothes were weighed down by the squelching mud and water, our officers would keep braying at us: ‘Beware! The enemy might attack!’ Buffeted from all sides and terrorized by the incessant guns, there were many soldiers who felt it would be far better to emerge from the trenches and take a chance with the enemy gunfire. There were others who were so paralysed by fear that they would appear almost insane and would not stir from their positions. Even if they had to answer nature’s call, they would be unable to take a single step. They would just dig a shallow hole right where they were and do their dirty business. In spite of their paralysis, they were somehow drafted to do some work by the booming orders of the officers. As mentioned earlier, the front line was manned by batches, each batch consisting of one sentry and five soldiers, with a non-commissioned officer in charge of them. They were responsible for holding the front line, and each soldier had to be on strict lookout for one hour at a time. A Lewis gun or a machine gun would be placed between every three batches. If the sentry felt that the enemy was trying to make an advance or if there was the slightest movement detected in the enemy lines, the guns would start firing. These Lewis guns played a very important role in this devastating war. These lightweight guns weighed only twenty-nine pounds and could be easily handled by one man who could move it from place to place, and when ordered, start firing at the rate of four hundred bullets per minute. Each of these guns was equivalent to a hundred rifles. We always had to be prepared at the firing line with all these arrangements.

Tear-Inducing Chilli Bombs

Indian infantry in the trenches, prepared against a gas attack [Fauquissart, France]. Dated 9th August, 1915. From the HD Girdwood collection, British Library.

After spending a miserable night in the trenches, we were shivering in our wet clothes in the morning. Suddenly we were ordered to ‘Stand to!’ Now what was this for? Even as we were wondering what it was all about, a gas that felt like chillies began pervading the trenches. Shrill orders to wear our goggles were urgently issued.

When the gas first attacked us, we could hardly understand what was happening. The gas began to envelop us from every direction and gas shells lobbed from the enemy lines were silently exploding all around us. Our eyes were in a state of extreme irritation. It felt as if they would burst.

We could hardly see anything; tears were flowing freely from our eyes, and it felt dark and terrifying. In spite of all this, everybody got into fighting position, facing the enemy lines and waiting for the inevitable attack. It was generally understood that the enemy released this gas just before it launched an attack. It rendered our soldiers blind and immobile for a brief while, and during this period, they could get the better of us and wrest our trenches. We could hardly open our eyes since the chilli gas had caused our eyes to turn red and swell up. How was a soldier to fight under such adverse circumstances? Along with this chilli gas, regular artillery fire was also kept up by the enemy, which further exacerbated the situation. To combat the nuisance of these ‘tear shells’ and to protect the eyes, a special kind of protective spectacles had been designed. They were made of ordinary glass through which everything could be seen, and the frame was fringed with flannel which ensured that the gas did not make contact with the eyes. The only saving grace was that exposure to tear gas, unlike poison gas, was not fatal; it merely left you blind for a short while.

On a Starvation Diet

Besides all the problems described above, we had yet another major problem to contend with: how to silence our hunger pangs. Soldiers on the firing line had to remain awake day and night and had no chance to lie down. To make matters worse, they had to scrounge for food. Admittedly, there was a lot of food dumped beyond the support lines as the motor transport guys would weave through the heaviest artillery fire to supply the food. Transporting the food from the dump to the firing lines was a major challenge for the soldiers. They would step out in large numbers to bring the food stuffed in small gunny bags back from the dump to the front line. The extreme conditions in the trenches, what with them being flooded with rainwater and slush, and the incessant firing of the enemy many a time prevented them from returning safely. They would be injured and fall down en route, and the food would also lie rotting there. The situation at the firing line was indeed desperate. The D Company had been assigned the support line and was responsible for supplying us with food, but as they came under heavy fire, they could not venture out of their trenches. Even though we were at the very front, the lines immediately to our rear suffered the most, bearing the brunt of the artillery fire. At least fifteen to twenty men from one company would get injured every day, and the condition of the injured was indeed very pitiable. How was food to reach us under this situation? We had to subsist on the few packets of biscuits and bully beef we had carried with us. Where was the question of getting a hot cup of tea? Not a single wisp of smoke was supposed to escape from the trenches. If the enemy spotted smoke coming from a trench, they would consider it to be a live target and fire immediately. The poor soldiers would go scrounging around for cigarette stubs.

Such was the dire situation at the front lines—starvation, mud and slush—and the relentless artillery fire had so harassed the soldiers that they were a pathetic sight to behold.

They had not shaved for days. How do you think they looked? It is best left to the imagination!

Our Final Assault

King George V inspecting Indian troops attached to the Royal Garrison Artillery, at Le Cateau on 2 December 1918. Imperial War Museums, London.

This was to be our last day at the famous Del Ville Wood. After many days of suffering and troubles, would it be too much to say that our imminent relief seemed like a new lease of life to us? Early in the morning, the news had already spread in the trenches that we were to be relieved tonight; our faces were aglow with delight. Just after noon, more authoritative news reached us, which was slightly different. We were indeed to be relieved, but we would have to perform some more arduous tasks tonight; the soldiers welcomed this news as a means of getting out of the trenches. All of us had been eagerly looking forward to being relieved for many days. Instead of spending yet another day in the slushy trenches, it was more preferable to emerge from them and show our courage in hand-to-hand combat. As per the orders issued to us, we were to launch our attack at ten in the night. Two companies were to lead the attack while the other two companies were to support us in the assault, and the trenches which we were to evacuate were to be occupied by the 4th Suffolk Regiment. All preparations had been made for a full-on artillery assault at the same time. Some of the soldiers were eagerly looking forward to the hour of the assault, while the colour had drained out of the faces of others. This supposedly minor assault was sure to claim the lives of many soldiers, but nobody knew who it would be. As things turned out, luck was on our side on this dark and evil night. It was pitch dark and the rain was falling steadily, and the roads were so slushy that they were of a porridge-like consistency. The enemy might have felt that there was very little likelihood of an attack from us in such awful weather. Our strategy was to attack under the cover of bad weather. Every minute seemed like an hour. As we waited, we could hear our hearts beating within our chests. After a seemingly eternal wait, it was finally the dark hour when we were to launch our attack. Just as orders were barked out to get us ready for the final assault, a volley of artillery fire passed over our heads towards the enemy lines. Within the blink of an eye, the Germans returned fire. Hundreds of shells were exploding loudly all around us. Their smoke darkened the skies, and we were already so scared that any enthusiasm we might have had for escaping from the trenches evaporated. Before we could think any further, orders were screamed out: ‘Over the top! Best to luck!’ The minute we heard the orders, we jumped out of the trenches and emerged into the open. We could soon hear the plaintive screams of our fellow soldiers, many of whom had fallen victim to the fire from the mortars and the machine guns. The rest of us braves, mindless of the fate of our colleagues, kept advancing. Lying flat on the ground, we crawled for over an hour and were lucky enough to finally make it to the enemy front lines. We then lobbed small bombs into their trenches and soon jumped into the trenches for a face-to-face duel. At this stage, many soldiers lost their lives to close-range enemy bullets, while some were bayoneted to death. We were able to take ten prisoners and capture one machine gun. We were about to turn back but heavy enemy artillery fire prevented us from doing so.

This was the heaviest bombardment I had ever seen, with thousands of shells exploding simultaneously all around us.

Because of the rain, mud and slush, our clothes felt like they weighed a ton. Dragging all this paraphernalia with us, a few of us were lucky enough to get back to our lines. Even as we were luxuriating in our good fortune, Lady Luck finally deserted us. A heavy shell landed just ten yards from where we were and exploded very loudly; we tried to jump away from it, but were not lucky enough to escape without being hit. I was also hit by a fragment. Even though I jumped as quickly as I could into a trench, my leg was injured in a gruesome manner. This had to happen just on the very last day when we were about to be relieved from trench duty. When fate turns against you, there is nothing you can do!

Adding Insult to Injury

Like me, there were hundreds of injured soldiers moaning and lying unattended in the trenches.

There was nobody to listen to our groans or pay any attention to us. Our troubles were just starting. If you managed to reach the dressing station, your troubles could come to an end. But in this bloody battle, it seemed like an impossibility. It was routine for hundreds of soldiers to get injured every day, and each platoon had its own stretcher-bearers who were supported by men from the Royal Army Medical Corps. For this assault, special working parties had also been formed. The firing and the destruction was, however, so severe that all these arrangements came to nought. Unlucky soldiers with stomach or leg injuries would frequently die a painful death in the trenches. If an injured soldier managed to drag himself away from the action, he stood a better chance of survival. Once you reached the dressing station, you would be one among thousands of injured soldiers crying for medical attention. The best possible care was given to them. There would be trolleys and vehicles from the Ambulance Corps to take them to the casualty clearing station. Once you reached this location, you could safely assume that your troubles had come to an end. All it needed was a cup of hot tea to make the injured soldier feel much better. After the seemingly endless days of nightmarish existence starving in the trenches, a cup of tea and the ministrations of female nurses felt like heaven. And then it was ‘Back for Blighty!’

This excerpt has been reproduced in arrangement with Harper Collins Publishers India Private Limited from the book The First World War Adventures of Nariman Karkaria: A Memoir written by Nariman Karkaria and translated by Murali Ranganathan. All rights reserved. Unauthorised copying is strictly prohibited. You can buy the book here.

ARCHIVE

Hinduism: Major Schools other than Bhakti

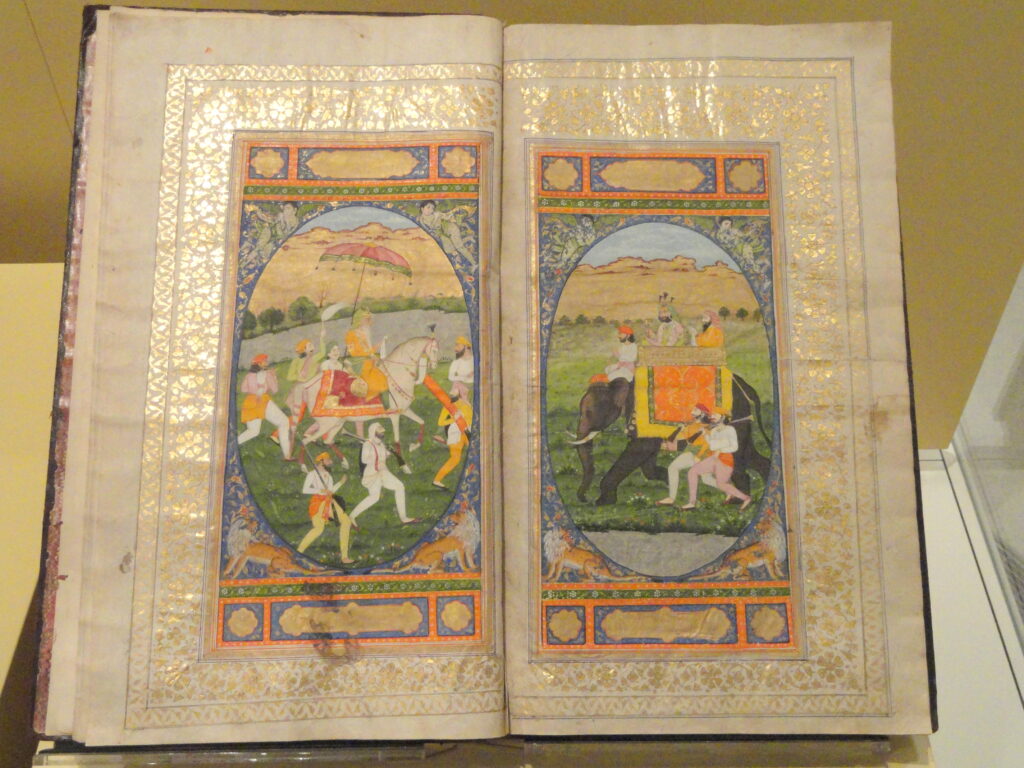

On a first view the continuing coexistence of Hinduism and Islam seems to be the most significant aspect of religious life in Mughal India. This very observation, however, tends to obscure the fact that Hinduism and Islam were not religions in the same sense. In his remarkable work on the religions of the world, the anonymous author of the Dabistan (written, c.1653), notes that “among the Hindus there are numerous religions, and countless faiths and customs.” In other words, while “Hindu” was the appellation of an Indian who was not a Muslim, it was yet difficult to speak of Hinduism as a single body of doctrine in the same sense as one could speak of Islam or, indeed, of the Semitic religions in general. It was equally true, however, that, having developed in mutual interaction and expressed in a large part in the same language (Sanskrit), the different sects of Hinduism yet shared the same idiom and even the same or similar deities. Written sixty years earlier, Abu’l Fazl’s A’in-i Akbarī (1595) precedes the Dabistan in giving us a very detailed and comprehensive description of Hindu beliefs.

On a first view the continuing coexistence of Hinduism and Islam seems to be the most significant aspect of religious life in Mughal India. This very observation, however, tends to obscure the fact that Hinduism and Islam were not religions in the same sense.

The Mughal period witnessed a continuing assertion in Brahmanical texts of almost all the basic elements of Higher or Orthodox Hinduism that the Ain-i Akbarī and the Dabistan outline. There was a notable exposition of Mimamsa in Narayana Bhatta’s Manameyodaya (c.1600). The school upheld the automatic functioning of the system of transmigration of souls in life-cycles, the station in each life being the result of deeds (karma) in the previous cycles. The author of the Dabistan makes the interesting observation that the “common belief” among the Hindus was that though there was one Creator, the created beings in their lives remained bound by the influence of their own deeds. The emphasis on karma was now the key to dharma, or prescribed conduct of the smriti schools. In this field the traditional doctrine continued to be reasserted in digests, commentaries and elaborations. Vachaspati (c.1510) wrote the Vivädachintamani in Mithila (Bihar). In Bengal, c.1567, Raghunandana of Navadvip wrote his twenty-eight treatises, the Smrititattva, which became an authority on ritual and inheritance. The Nirnayasindhu of Kamalakara Bhatta (1612), which cites Raghunandana as an authority, in turn, obtained legal and religious authority in Maharashtra. An encyclopedic legal work, the Viramitrodaya was compiled by Mitra Mishra under the patronage of Bir Singh, a leading noble of Emperor Jahangir (1605-27).

Ain-i-Akbari

![]() These works did not generally make any noteworthy deviations from positions adopted in respect of the supremacy of the Brahmans and the caste-rules as defined by the earlier Smritis. If anything, they repeated and elaborated the restrictions imposed on the lower castes and women. Raghunandana went so far as to declare that the Brahmanas were the only ‘twice-born’ left, since, according to him, the Kshatriyas and Vaishyas had by now fallen among the ranks of the Shudras!

These works did not generally make any noteworthy deviations from positions adopted in respect of the supremacy of the Brahmans and the caste-rules as defined by the earlier Smritis. If anything, they repeated and elaborated the restrictions imposed on the lower castes and women. Raghunandana went so far as to declare that the Brahmanas were the only ‘twice-born’ left, since, according to him, the Kshatriyas and Vaishyas had by now fallen among the ranks of the Shudras!

In Vedanta, the Shankaracharya tradition was influential enough to produce a number of texts. It is clear from various statements in the Dabistan that the pantheism of Shankaracharya had by the mid-seventeenth century permeated a large number of sects and schools. Sadananda in his Vedantasära (c.1500) exhibits an admixture of Samkhya principles. On the other hand, Vijñänabhikshu (c.1650), author of the Samkhyasara, admitted the truth of Vedanta, professing to see the Samkhya Duality as no more than one aspect of the Truth. A similar reconciliation of Vedanta with Shaivite beliefs seems to have been developed by Appayya Dikshita (1520-92) of Vellore, a prolific writer on many subjects. A Shaivite theologian of the south of a later phase was Shivananar (fl.1785).

Commensurate with the widespread currency of Tantrik beliefs and practices reported by the Dabistan, Tantrik literature received considerable additions during this period. Mahidhara of Varanasi wrote the Mantra-mahodadhi in 1589. In Bengal Pürnända (fl. 1571) wrote treatises on philosophy and magical rites; in the next century Krishnänanda Agamavägisha of Navadvip wrote the authoritative textbook, Tantrasara.

Bhakti Sects

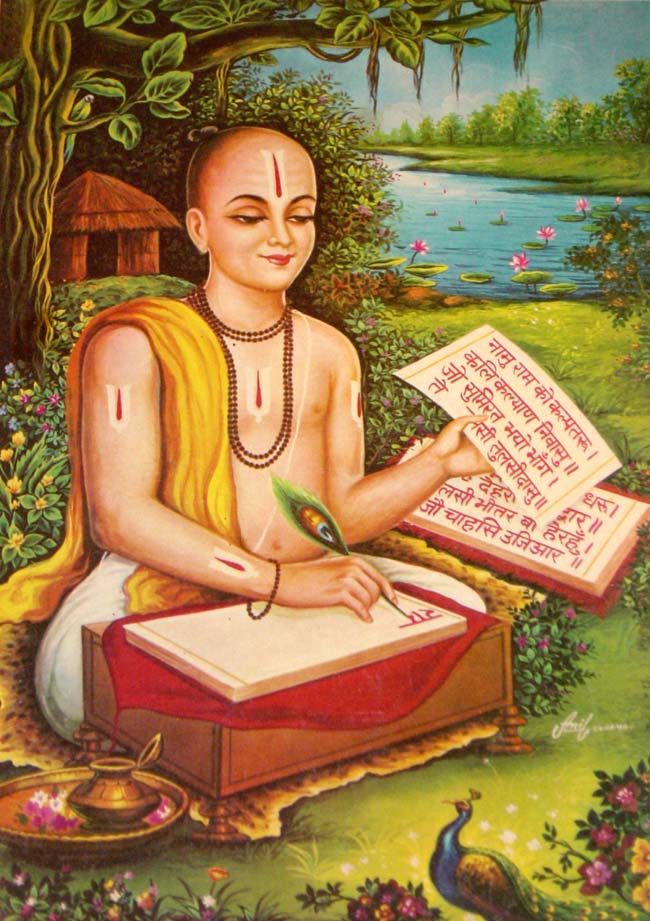

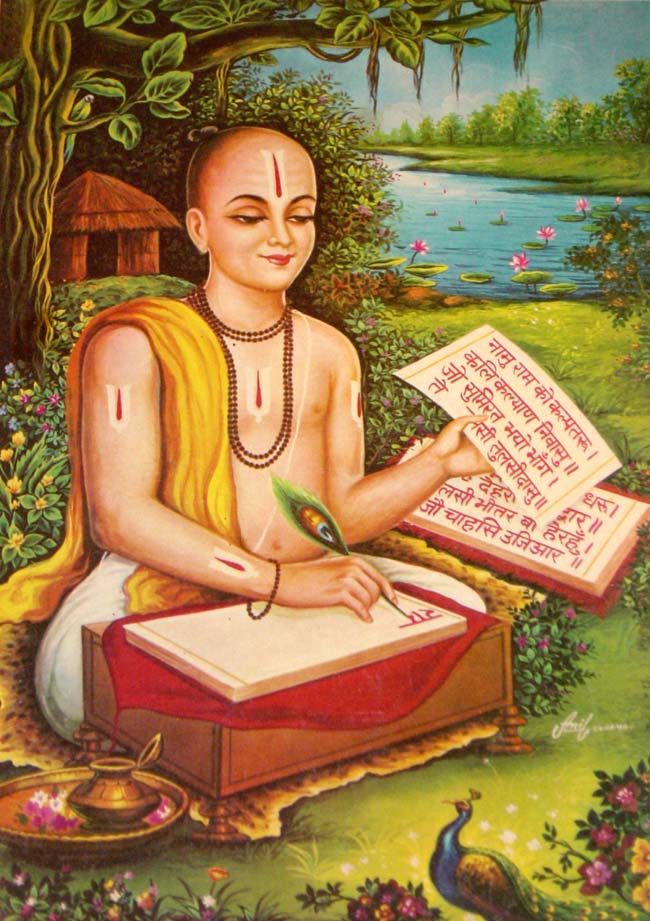

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were, however, essentially the centuries of Vaishnavism. In the Northern India the Rama cult had its greatest propagator in Tulsidas who in his Ramcharitmanas, written in the Awadhi dialect, gave a popular garb to the original Rāmāyaṇa. Tulsidas was a firm believer in the dharmashastra, and he regarded the popular monotheistic cults, with their Shudra leaders, as signs of the degradation of the present age (kalijug). Yet this was not the main message of his work. In his fervent verses of devotion and portrayal of a just Rama, the incarnated deity became God, in full control of destiny.

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were, however, essentially the centuries of Vaishnavism.

The expression was still more emotional when the object of bhakti (devotion) was Krishna, another incarnation of Vishnu. Chaitanya (1485-1533), a Brahman priest of Navadvip (Bengal) initiated a cult of Krishna and his female lover Radhā, in which the devotee, repeating the deity’s name, pictured himself as a companion of Krishna at Vrindaban, re-enacting in his mind His “manifest” sports (lilas). These mental visions were the means of a communion with the Lord, in which Krishna too relished the devotee’s love. While Chaitanya had his followers mainly in Bengal, he left very active successors, the gosvamins, at Vrindaban near Mathura, who in a series of Sanskrit works gave a philosophical basis to the cult and outlined its ritual. To his followers Chaitanya himself appeared as a joint incarnation of Krishna and Radha. Though in their life as householders, the devotees followed the caste ritual, the right of worship was not denied to the lower classes; and the Sahajiya sect (eighteenth century) rejected life as ordained by the smritis and introduced shaktik and tantrik practices. In Assam, a Vaishnava sect paralleling that of Chaitanya was founded by a junior contemporary of his, Shankaradeva (d.1568), who however avoided image-worship and emphasized an Absolute, Personal God, to Whom all devotion directed in the form of love for Krishna.

Vallabhacharya (d.1531) and his son Vitthalnath (d.1576) propagated a religion of grace (pushtimarga); and Surdās, owing allegiance to this sect, wrote Sur-saravali (1545) in the local language, Braj, in which the sports of Krishna with Radhā and others were described as manifestations of the Lord’s supreme powers. The sect obtained some popularity in Gujarat and Rajasthan; there developed an excessive adoration of the descendants of Vallabhacharya (now regarded as an incarnation of Krishna), who obtained the designation ‘Mahārāj’, and relied on the following of a rich mercantile community. The Rädha vallabhis owed their foundation to Hita Harivamsha (d.1553) and assigned to Radha the more crucial position in the Duality of Divinity.

Tulsidas composing his famous Avadhi Ramcharitmanas (Wikipedia Commons)

The Vaishnavite movement in Maharashtra contained both Unitarian and conservative elements. Eknath (d.1599), a Brahman, expounded the principle of bhakti and allowed all castes as well as women to assemble and praise the Lord and join in the ecstasy of devotional chants (kirtan). He also tended to discount mere ritual. Tukārām, (d.1649), a Shūdra peasant, might possibly have been influenced by the Chaitanya sect yet while addressing himself to Vithoba, the Lord of Pandhari, his God (Vitthal) tends to be closer to the Ram of the monotheist Kabir than to the Krishna of Chaintaya. He sings of the possibility of recourse to God by a devotee, howsoever lowly in status, and does not hesitate to use the word Allah for his God. Quite different in approach was his junior contemporary, Rāmdās (d.1681), who combined the propagation of the worship of Rama as God with the upholding of the dharma (“the Maharashtra Dharma”), i.e. maintenance of “the holiness of the Brahmans and deities”. He organized maths or centres of ascetics, and was patronized by Shivaji, the Maratha ruler (d.1680),

In Karnataka, the Dāsakūta movement seems formally to have belonged to Madhvächärya’s system. It originated with Shripadaraya (d.1492), but was mainly spread by his disciple Vyasaraya (d.1539). The songs of the sect in Kannada show attachment to Viththala, the deity of Pandharpur, and yet revel in an ecstasy of devotion which recalls Chaitanya. A disciple of Vyasaraya, Kanakadas was a shepherd (Kurub) and in his popular compositions insisted on the lowly to the Lord.

Other Sects; Jainism

Logic and dialectics (nyaya and tarka) continued to attract attention through the compilation of commentaries and text-books. The Navadvip schools produced Raghunātha Siromani’s commentary (c.1500) on Gañgesha; and on this commentary Gadhādara (c.1700) in turn commented. Shañkara Mishra in Upaskära (c.1600) commented on the Nyāya-sütra. Among textbooks, Annam Bhațța wrote Tarkasamgraha (c.1585) and Jagadisha, the Tarkamyita (c.1700). A.B. Keith comments unfavorably on the obscurity and scholasticism of this literature; he also notes that all the schools were now “fully theistic”.

The survival of the materialist ideas of the Chārvākas, described in the Dabistān as constituting the ninth tradition within Hinduism, is of considerable interest. The Chārvākas believed that only the world perceived by the senses was real; “whether one becomes high or low results from the nature of the world”, and not from divine direction. The existence of a Creator or of gods was denied, and so also the truth of the Vedas. A number of specific criticisms by them of the beliefs in the miraculous and divine are quoted; possibly these circulated by word of mouth or are derived from the texts of opponents, for our author does not name any text or votary of the sect for his source.

The main area of strength of Jainism during this period was Gujarat, though Jain communities were found elsewhere too. Jain religious literature was composed in Gujarati, Sanskrit, Präkrit, Braj, Kannada and other languages, but much of it is described as repetitive or hagiological. The Jain version of dialectics was set out by Yashovijayaji in Jaina tarka-bhāshā, c.1670; he was the author of other religious books as well. Both the sects of the Jains, the Shvetāmbara and Digambara, flourished in the Vijayanagara empire. Jain priests also claimed exceptional proximity to Akbar and his court. The Jain laity was increasingly confined to “the Banya and Bohra castes of tradesmen, most of them selling foodgrains and some taking to service” (Dabistān).

Kabir and the Monotheistic Movement

A change of substantive proportions in the Indian mode of religious thought was marked by the preaching of the weaver Kabir (d., c. 1518) of Varanasi. One could, on the other hand, see in his compositions a distilling of Vaishnavite, Nath-yogic, even Tantric beliefs to obtain a rigorous monotheism, parallel to the Islamic; or see, alternatively, a rigorous acceptance of the logic of the monotheism of Islam, while rejecting its theology, with the exposition necessarily offered in a language that those outside the culture of Islam could understand. Strong arguments can be urged in favor of both views; but in whatever manner Kabir came to espouse the views he proclaimed, his contemporaries were deeply struck by their boldness and vigor.

A change of substantive proportions in the Indian mode of religious thought was marked by the preaching of the weaver Kabir (d., c. 1518) of Varanasi. One could, on the other hand, see in his compositions a distilling of Vaishnavite, Nath-yogic, even Tantric beliefs to obtain a rigorous monotheism, parallel to the Islamic; or see, alternatively, a rigorous acceptance of the logic of the monotheism of Islam, while rejecting its theology, with the exposition necessarily offered in a language that those outside the culture of Islam could understand. Strong arguments can be urged in favor of both views; but in whatever manner Kabir came to espouse the views he proclaimed, his contemporaries were deeply struck by their boldness and vigor.

Kabir propounded an absolute monotheism that countenanced no image-worship and no ritual. Servitude to God rather than offer of love to Him is the true means of salvation – love, though not absent, is clearly a subordinate element. This weakens any argument that Kabir derived his thought from either Vaishnav bhakti or Islamic Sufism. It was by one’s faith in God and work in this life one would be judged by God, for –

Kabir, the capital belongs to the Sah (Principal Merchant/Usurer)

And you waste it all.

There would be great difficulty for you

At the time of rendering of accounts.

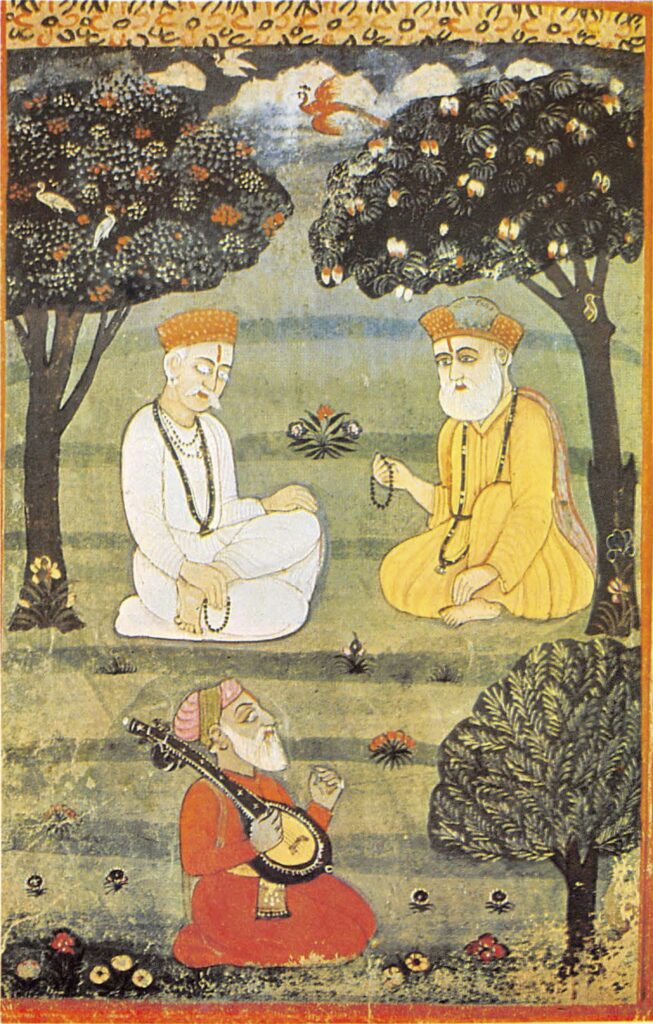

Kabir with Namadeva, Raidas and Pipaji. Jaipur, early 19th century

The Islamic influence in this concept of exact measurement of one’s thought and deed at the Day of Judgement is manifest; at the same time, the vision of God as a usurer certainly reflects not the traditional Muslim, but the impoverished artisan’s natural view of the Master. But if Kabir warns of punishment, he does not look forward to a heaven where one’s desires would be fulfilled this marks another departure from Islamic theology:

As long as man desires to go to heaven,

So long he shall find no dwelling at God’s feet.

Kabir’s rejection of the concepts of ritual purity and pollution, the laws of the smritis and the caste system is uncompromising in its completeness. As a late-sixteenth century summary of his teaching tells us, Kabir refused to acknowledge caste distinctions or to recognize the authority of the six schools of Hindu philosophy; nor did he set any store by the four divisions of life (ashrams) prescribed by the Brahmans.

As for the two contending religions, Kabir says scornfully: The Hindu dies crying “Rām”, the Muslim, “O Khudā (God).”

Says Kabir: He who lives, shall not go amongst either.

And then the triumphant revelation:

Ka’ba has once more become Kāsi, Rām has become Rahim!

Moth (a coarse pulse) has become fine flour; so sits down Kabir to enjoy it.

To a region, now torn in the struggle between temple and mosque, this teaching still retains a living and vibrant message.

Kabir’s audience was the common man, the artisan, the peasant, the village headman; his similes and metaphors came from their life and travels; and his language was the tongue that they spoke. Different regional dialects have left their imprint on his original Awadhi, as he or his verses traveled about. True, he is also influenced by some of the prejudices in his environment (chiefly poor and male) against women. Still, he had found a new dignity for the poor and the downtrodden in the world of his Lord. So came now a procession of his peers, lowly like him, seeking God in this land of Homo Hierarchicus. No one can, perhaps, improve upon how in 1604 Arjan, the fifth gurū of the Sikhs, saw this dramatic movement and made Dhannā, a Jāt peasant, sing of it.

To a region, now torn in the struggle between temple and mosque, this teaching still retains a living and vibrant message.

The evidence of their compositions show that Ravidās (or Räidās), the worker in hides, and Sain, the barber, both belonging to the sixteenth century, regarded Kabir as their precursor. A similar position with regard to Kabir was adopted by Dadū, the cotton-carder (d.1603), who obtained a considerable following in Rajasthan. A little later (1657) there appeared in Haryana the Satnāmi sect, again owing explicit allegiance to Kabir, and counting among its followers “peasants and tradesmen with small capital”. The sects of the follower of these teachers were called panth; in time, in spite of preserving the anti-ritualistic compositions of their founders, these tended to develop rituals of their own and to introduce notions and institutions taken from traditional religion, notably the ascription of avatār status to their original preceptor, and a caste-like status to the monotheistic community itself. Even a Brahman parentage came to be sought for Kabir, the weaver. Such a reshaping of the original message of the masters, is a testimony to the strong roots of ritual and the caste-order in those times; and our own times are, perhaps, no different.

Sikhism

The sixteenth century saw the rise of Sikhism, now one of the recognized religions of the world. It began as a sect (panth) of the followers of Gurū Nanak (1469-1538), a Khatrī (an accountant and mercantile caste) of the Panjab, more or less on the pattern of other sects of the contemporary popular monotheistic movement. The Gurü Granth Sahib, the scripture of the Sikhs, compiled by Gurū Arjan in 1604, includes, besides compositions of Nānak and the succeeding Gurus, those of the Muslim saint Shaikh Farid, and of Nāmdev, Kabir and Ravidās and other bhagats (saints), in the same manner as such compositions are included in the compilations of the Dādū panthis, viz., the Panchvānīs and the Sarbangī of Rajjabdās. This suggests that, at least till the beginning of the seventeenth century, there was a strong sense among Gurū Nānak’s followers that they belonged to a general monotheistic movement, with only some differences of both nuance and substance separating its different components.

Gurū Nanak believed in One God, and saw an intensely personal relationship between Him and the devotee, who would humbly serve and love Him and obtain His grace in return. At the same time God was formless and omnipresent and could not be represented in a physical form. Image worship and ritual were thus condemned. Nānak strongly emphasized ethical conduct, especially kindness to fellow human beings. He condemned arrogance of birth, the cult of ritual pollution and differences of caste. The salvation to be aimed at was nirvān or sach khand, the true abode, when man at last realizes God.

The Gurü Granth Sahib, the scripture of the Sikhs, compiled by Gurū Arjan in 1604, includes, besides compositions of Nānak and the succeeding Gurus, those of the Muslim saint Shaikh Farid, and of Nāmdev, Kabir and Ravidās and other bhagats (saints), in the same manner as such compositions are included in the compilations of the Dādū panthis, viz., the Panchvānīs and the Sarbangī of Rajjabdās. This suggests that, at least till the beginning of the seventeenth century, there was a strong sense among Gurū Nānak’s followers that they belonged to a general monotheistic movement, with only some differences of both nuance and substance separating its different components.

It is not clear to what extent Gurū Nānak gave an organizational form to his sect, nor whether the word gurū used in his compositions, e.g. in Japjī, means God or spiritual guide. But two processes appeared soon enough. First, a line of Gurūs or spiritual successors to Nānak was established. Their status came to be exalted to incarnations of the same perfect spirit (each gurū being known as the mahalla from Arabic mahall, or station); and total obedience to the Gurū was expected from each disciple, the Sikh-Gurū, whence the abbreviated name Sikh.” The second was the expansion of the sect among the Jatts or peasants of the Panjab: the Gurus were all Khatris, but their principal lieutenants, the masands, were already mostly Jatts in the seventeenth century.

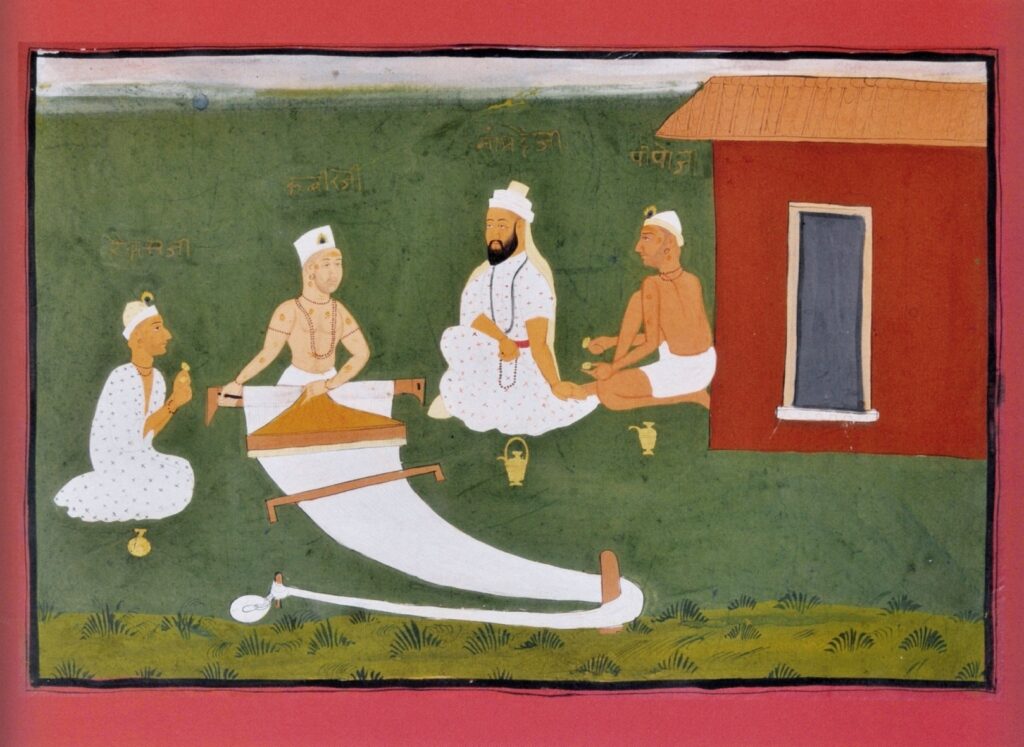

Nanak (right) and Mardana (foreground) with Bhagat Kabir (left). This painting is found in the B-40 Janamsakhi, written and painted in 1733. The painting was made by Alam Chand Raj

These two developments provided ground for a third, the acquisition of armed power. After the martyrdom of Gurū Arjan (1606), a conflict with the Mughal authorities could not be long avoided. The military power of the Gurüs reached its apex under the tenth and last Gurū, Gobind Singh (1666-1708). In 1699 he sought to weld his followers into a militant community (Khālsa’) by prescribing a common baptism for men of all castes and appointing the items everyone had to carry, including the dagger or sword (kirpān), which was part of the public bearing of a professional soldier of the time.

Immediately after Gurū Gobind Singh’s death at Nander in the Deccan (1708), his disciple Banda Bahādur returned to the North and raised a massive plebeian rebellion, in which Sikhs, including many fresh converts, joined along with discontented zamindars. He operated over large portions of the Panjab and Haryana plains, retiring to the hills for some time. The rebellion was ultimately suppressed, and Banda was executed in 1716. A period of demoralization and division followed, but recovery began as Mughal power collapsed under the impact of Nādir Shāh’s invasion (1739) and the repeated invasions of Ahmad Shah, the Afghan ruler (1747-73). From the 1750s onwards, the Sikh dals and misals (groups) became more and more powerful, led by individual chiefs (sardārs), who organized troops of increasingly professional mounted musketeers. Many of the chiefs came from peasant or artisan stock, like one of their foremost leaders at this time, Jassa Singh, reputed to be originally a carpenter. A semblance of unity was sought to be maintained by the tradition of an annual ‘sarbat Khālsa‘ at Chak Gurū (Amritsar); but dissensions grew apace, and each chief tended to carve out a separate territory for himself. The process was at last checked by Ranjit Singh (1780-1839), who established a traditional kingdom in the Punjab, ostensibly in the name of the Khālsa.

Islam: Sixteenth Century

Islam in India remained ideologically so closely linked to the main currents of Islamic thought transmitted through Arabic and Persian that it may not perhaps be wholly correct to speak of “Indian Islam” as an isolated compartment within the larger world of Islam. Such specificities in customs and beliefs as existed here were partly linked to the fact that India had much greater association with Iran and Central Asia than with the Arab countries. The continued co-existence with Hinduism brought into focus, in course of time, the problem of assessing non-Muslim faiths and beliefs. Sufism or Muslim mysticism, whose ‘chains’ (silsilahs) came from Iran and Central Asia, found a congenial soil in India. By the sixteenth century Sufism had been accepted by most orthodox theologians as a permissible discipline so long as the formal requirements of Sharīa, the law and ritual of Islam, were met. But the comfortable arrangement was seriously disturbed when mysticism opened the doors to the pantheistic doctrines and speculations of ibn al-‘Arabi (d. Damascus, 1240).

It may be justly held that ibn al-‘Arabi’s views were a bold but logical elaboration of the sufic concept of communion with God (fana). With him Separation, from being unnatural, became illusory, and the communion, from being the ultimate object, became the only eternal Reality. His doctrine of Wahdat al-Wujüd (Unity of Existence) had, by the latter half of the fourteenth century, begun to influence sufic circles in India and, despite opposition, had steadily gained adherents. For a country like India, where Islam’s co-existence with the totally different religious tradition of Hinduism could not but lead to inner questioning, ibn al- Arabi’s doctrines seemed to offer a persuasive explanation of diversity that belonged only to the sphere of illusion. Alongside this, there was the proposition of the Perfect Man (insān al-kāmil), in which ibn al-‘Arabi idealized the mystic guide (shaikh) as ‘a microcosm in whom the One is manifested to Himself. This vision inevitably supplemented or reinforced the concept of mahdi, the reformer and redeemer coming in advance of the Day of Judgement, the expectation of whose arrival was part of popular Muslim beliefs. The two concepts could influence each other, and as the close of the first millennium of Islam drew near (AH 1000 = AD 1592), they produced a millenary wave.

The Mahdawi movement was the first indication of the new intellectual turbulence. Saiyid Muhammad of Jaunpur (d.1505), a well-traveled scholar, proclaimed himself Mahdi. Apparently, the hope for redemption by following the Mahdi’s message and his call for ethical conduct, continued to win followers for his sect, who began to establish their communities (da ‘iras) at various places. Theologians tirelessly denounced them; but the sect survived.

In the last quarter of the sixteenth century in the Kabul province of the Mughal Empire there arose another sect with similar millenary tendencies, except that its founder Bāyazid (Miyän Raushan) (d.1585) claimed that he was a Prophet (nabi), and not a Mahdī. Believing in a pantheistic mysticism, he envisioned the state of sukunat, where the self merged with God. His refusal to countenance anyone who refused to accept his message helped forge the Raushaniyas into a militant sect among the Afghans, in whose language (Pashtu) his book Khairu i Bayān was composed. The Raushaniya militancy led to a long war with the Mughals, during which the sect was suppressed.

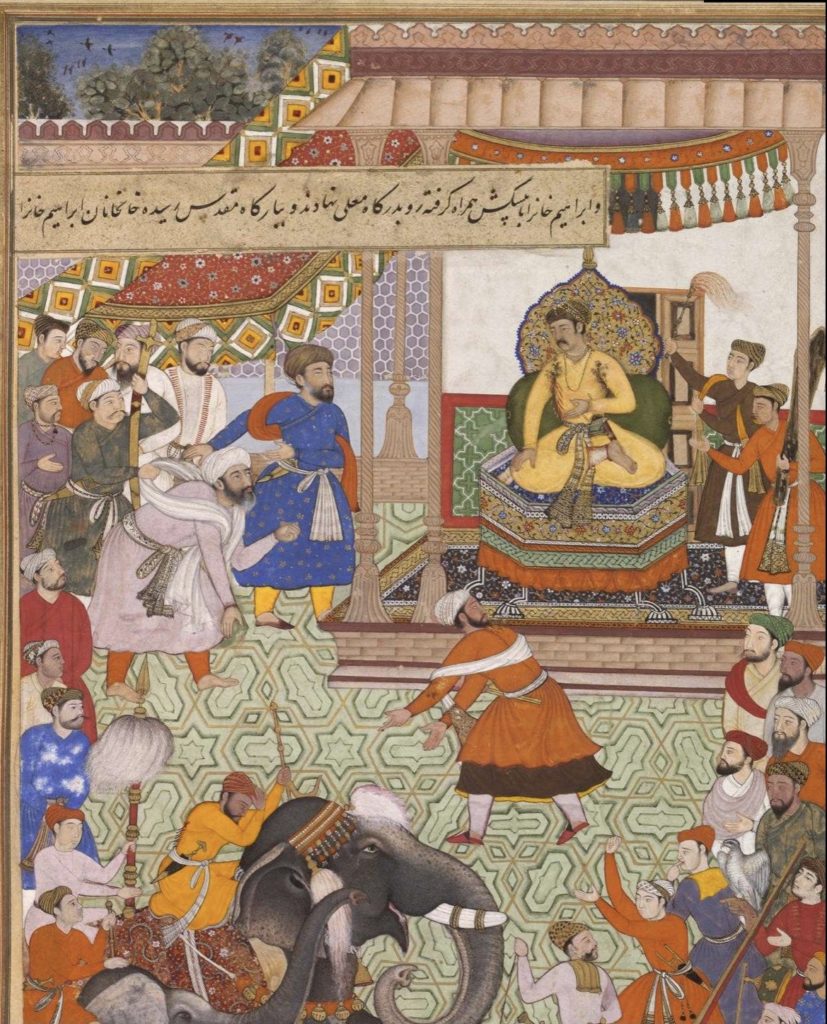

Akbar: A Supra-religious Sovereignty

The great upheaval in thought that was to come under Akbar (emperor, 1556-1605) had its origins partly at least in the same two intellectual impulses of Pantheism and the Messiah-cult, which we have just discussed. Akbar’s religious interests initially lay within traditional Islam. His splendid city of Fatehpur Sikri, dominated by the great mosque, was built early in the 1570’s in honour of Shaikh Salim Chishti (d.1572), the sūfi saint. But in the 1570’s Shaikh Taju’ddin, a protagonist of ibn al-’Arabi, introduced his principal concepts at the Court. Shaikh Mubārak (d.1593) gained in influence, and not only had he read ibn al- Arabi and the Iluminationist (Ishrāqi) doctrines of Shihäbu’ddin Maqtūül (twelfth century), but had also been suspected of Mahdawi inclinations. The popular belief in the need of renewal at the end of the first millennium of Islam, and of a reformer for the purpose, lay partly behind Akbar’s direction in 1582 for the compilation of the Tarīkh-i Alafi, a history of the millennium beginning with the death of the Prophet. Akbar himself could be seen as such a reformer, while being identified as the Perfect Man in the ibn al-’Arabi tradition. An early limited application of this concept was attempted in the mahzar of 1579. This was a statement signed by leading Muslim theologians at the court, declaring that Akbar, in his position as a Just Sultan, was entitled to exercise limited powers of interpretation and elaboration of Muslim law, which was to be binding on all Muslims.

Akbar’s religious interests initially lay within traditional Islam. His splendid city of Fatehpur Sikri, dominated by the great mosque, was built early in the 1570’s in honour of Shaikh Salim Chishti (d.1572), the sūfi saint. But in the 1570’s Shaikh Taju’ddin, a protagonist of ibn al-’Arabi, introduced his principal concepts at the Court.

The growing influence of pantheism, however, soon took matters beyond the rather modest and sectarian position assigned to the Emperor in the mahzar. Discussions had taken place in the presence of Akbar, among representatives of Sunni Muslim scholars, at a special building, the “ibadatkhana (house of prayer), at Fatehpur Sikri. These discussions and debates were now extended to involve Muslim divines, Sunni and Shi’a, şūfis and rational scholars (hakims), and, subsequently, Brahman scholars, other Hindu recluses, Jains, Parsis and Christians (Jesuits), whose first mission reached the court in1580. These discussions convinced Akbar that no single interpretation of Islam was correct or even forthcoming, and further that no single religion could be true, but that all drew, but only in part, upon the same Truth. It was for him, as the chosen man of God, to assist in the realization of a consciousness of Absolute Peace (Sulh-i Kul) in order to prevent idle strife between the votaries of different religions and factions. It was held that both “religion (din) and the, secular world (duniya)” were patterns drawn by “the cloud of duality,” that is, by consciousness of an existence separate from God. This being so, all religions were to be tolerated, but did not need to be followed.

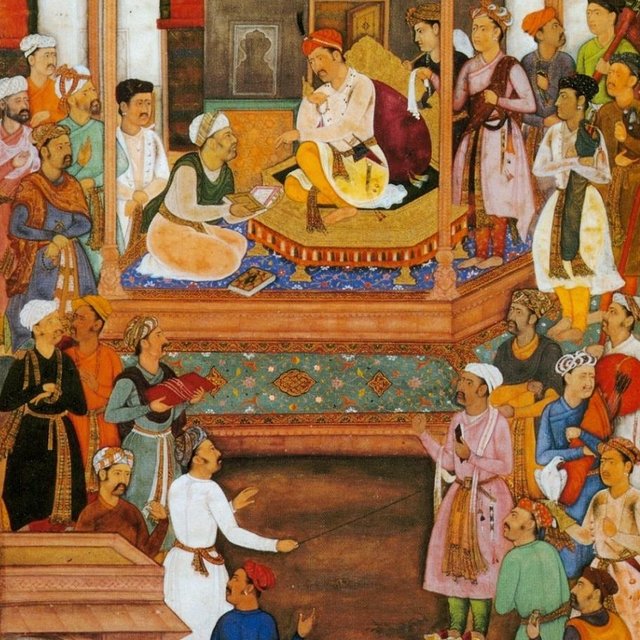

Jesuits at Akbar’s court

For an elite corps of disciples (irādat-gazinān), there was prescribed by Akbar a total submission to the imperial preceptor and certain principles and code of conduct, which his son Jahangir summed up as follows:

Let the disciples not blacken and spoil their time by engaging in hostility with any religious community and let them follow in their relations with members of all religious communities the path of Absolute Peace (Sulh-i Kul). Let them not kill any animal by their own hand, nor wear weapons except in battle or chase… Respect must be shown to the Sun and the Moon, which exhibit the Light of God, according to the degrees of each. God must be conceived as the true Creator and Cause in all times and circumstances, and one should so meditate on this that, whether in seclusion or in company, one’s thought should not be away from God for a single moment.

It may be mentioned that there is no sanction for the belief that Akbar wished to institute any new religion or that it was called Din-i llāhī.

The growing influence of pantheism, however, soon took matters beyond the rather modest and sectarian position assigned to the Emperor in the mahzar. Discussions had taken place in the presence of Akbar, among representatives of Sunni Muslim scholars, at a special building, the “ibadatkhana (house of prayer), at Fatehpur Sikri. These discussions and debates were now extended to involve Muslim divines, Sunni and Shi’a, şūfis and rational scholars (hakims), and, subsequently, Brahman scholars, other Hindu recluses, Jains, Parsis and Christians (Jesuits), whose first mission reached the court in1580.

The policy of equal treatment of all religions (as distinct from a simple policy of tolerance) that Akbar enforced, permitting full freedom of religious expression, conversion and construction of places of worship to all, was consistent with his views as they came to be formulated by the early 1580’s. It was, perhaps, a policy for which it was not easy to find a parallel in the contemporary world – a fact underlined with great pride by his son. It is, however, more likely that Akbar’s own views took direction, because a policy of tolerance was politically very useful and had, indeed, been adopted much before his philosophical views took the form they did in the last twenty- five years of his life. His minister Abu’l Fazl declared that sovereignty is itself in the nature of farr-i izadi, God’s light, and the sovereign, like God, was parent to all mankind; it was therefore his function to ensure that “out of differences of religion, there does not arise the dust of antipathy.” This declaration, it will be seen, draws not on any philosophical or religious tradition, but on a simple assertion of the Sovereign’s absolute power, and the obligation that such absoluteness imposed on him, to keep all his subjects contented.

It is, however, more likely that Akbar’s own views took direction, because a policy of tolerance was politically very useful and had, indeed, been adopted much before his philosophical views took the form they did in the last twenty- five years of his life.

Inter-Religious Investigation

Akbar’s proclamation of belief in pantheism and șulh-i kul, in its turn, had some significant ideological consequences, in that it suddenly threw open orthodox beliefs to criticism ôn the most delicate issues of ethics and theology. Internally, it created within Islam, a recognized niche for the Shi’ite trend in spite of considerable polemics existing between Sunnis and Shi’as. It provoked restatements of orthodox position, while it also generated a fresh interest in reason and science. Finally, a most interesting movement was fostered among Muslims towards a study of Brahmanical texts and of Vedānta, with a view to obtaining a knowledge of “truth” as perceived by Hindus. Akbar initiated a series of translations of Sanskrit works, among which the religious literature included the Atharva-veda, the Mahābhārata, and the Rāmāyana, while the Yogavasishtha was translated for Akbar’s eldest son Salim (the later Jahāngir). In the Ai’n-i Akbarī, Abūl Fazl was able to give a fairly cogent and accurate description of the various Hindu schools of philosophy, theology, beliefs and laws, based on a fresh scrutiny of the texts through translations made “after much difficulty”. Such scrutiny exhibited much common ground between Islam and Hinduism, since “though in some of the purposes and arguments there is room for dispute, it became established that the Hindus believe in the worship of God and in monotheism” (Abū’l Fazl). There is a greater appreciation of the logic of the Karma doctrine; and later, with Jahāngir, came the recognition that Vedānta “is the knowledge of taşawwuf (mysticism)”, presumably because it was pantheistic.

A painting depicting the scenes of the Ibādat Khāna. (Wikipedia Commons)

Islam’s recognition of Hinduism reached its culmination in Dara Shukoh (1615-59), the eldest son of Emperor Shähjahān. Därā began his intellectual career with an immersion in Muslim mysticism through attachment to the Qadiriya order of Mian Mir (d.1635) and Mulla Shah Badakhshi (d.1661); and his early writings were on Muslim mystics. But interest in monotheism and mystic practice led him to the composition of the Majma ‘u-l Bahrain (‘the mingling of two oceans’) in 1654-55. In this tract he explains the major terms and concepts used in Hindu spiritual discourse, and sees an identity between the Hindu and Muslim seekers of God, in all things except language. In 1657 came what was, from the philosophical point of view, the most important effort: a translation of fifty-two Upanishads, under the title Sirru’l Asrar, the Great Secret, a faithful rendering of very difficult texts.

Islam’s recognition of Hinduism reached its culmination in Dara Shukoh (1615-59), the eldest son of Emperor Shähjahān.

This was in some respects a momentous event, since it was this translation which, from its being rendered into Latin by Anquetil Duperron (1801-02), led ultimately to a world-wide recognition of the philosophical richness of these ancient texts. In 1655-56 at Dara Shukoh’s instance Habibullah made a fresh translation of Yogavasishtha.

Indicative of the spirit of the times is a work already referred to, the Dabistān (‘School), written in 1653 by an author who does not divulge his name or religion, but incidentally gives many facts about himself, which suggest he was the member of a Parsi sect, with the pen-name ‘Mobid’. He set out to write in Persian a work giving a truthful, unbiased account of all religions, and so deals in his work with the Parsis, Hindus, Buddhists (Tibetan), Jews, Christians and Muslims, along with different sects within each religious tradition. Most of the information was gathered by the author himself by his reading of the writings of the votaries of each sect or by his conversations with them. His linguistic equipment appears to have been considerable; and it is doubtful whether a work of this kind existed in any other language at this time. Clearly, even if the author was not a Muslim, but a leading light of a Parsi sect, his readership, given the language in which he wrote, consisted largely of Muslims. That the interest it evoked among them was widespread is shown by the large number of manuscripts of the work that have survived.

Islam: Major Currents after Akbar

The freedom of religious discussion accorded to all under Akbar assisted in the transformation of Shi’ism from a ‘heresy’ into a recognized variant of Islam in India. Qāzi Nūrullah Shustarī (1549-1610) was the first isnā- ‘asharī Shi’a theologian in India to have left important writings. Disdaining taqiyya (or permitted dissimulation), expressly on account of the freedom accorded under Akbar, he openly defended Shi’ite position against Sunni criticisms. He died in 1610 as a result of physical punishment inflicted on him at Jahāngir’s orders and is considered a Shi’a martyr. Though the details of the incident are obscure, it was apparently not a part of any general persecution of the Shi’as. Immigrants from Iran, who were mostly Shi’as, held high offices in the Mughal empire; and Shī’a observances were publicly held. Haidarabad in the Deccan in the seventeenth century and Lucknow and Faizabad in Awadh in the eighteenth, became important centres of Shi’ite learning.

Muslim or Sunni orthodoxy responded in various ways to challenges from the free airing of views hitherto thought to be unacceptably heterodox. How complex the responses could be is shown by the ideas of Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi (1564-1624). His first surviving work, a rather slight tract, is devoted to a refutation of Shi’a beliefs (Risāla dar radd-i rawāfiz). His strong attachment to the Shari’a was displayed in his hostility to Akbar’s policies of tolerance and in his bitter opposition to Hindus and Hindu beliefs that he gives expression to in his letters soon after Akbar’s death. But he had in the meantime (1600) become a disciple of the Naqshbandi mystic Bãqi Billāh (d.1603); and from this point onwards he became increasingly concerned with Ibn al-‘Arabi’s theories of Unity of Existence (wahdat al-wujud) and the Perfect Man. His acceptance of the first idea was only partial. The seeker, he asserted, must transcend this notion in order to grasp separateness, the unity being for him now, only the unity of all that he sees, for in the final stage he looks only at God and none else (wahdat ash- shuhud). A rigorous conformity with the Sharī’a was to him as much a requisite for the mystic as for anyone else; and he condemned all innovations. Ibn al-‘Arabi’s theory of the Perfect Man was, on the other hand, incorporated in Sirhindi’s own concept of the qaiyum (‘the maintainer ‘). The possessor of gnosis (ãrif). by being the Perfect Man, is chosen as the qaiyüm, or God’s vizier or vicegerent, and thus attains a function assigned previously to prophets. This function is identified with yet another- that of the renovator (mujaddid) of Islam in its second millennium (alf-i șān). It was clear that to him and his followers both the offices of qaiyüm and mujaddid were united in Shaikh Ahmad himself.

In Mughal India Shaikh Ahmad’s seems to have been the last major statement of a claim to be the Chosen Man within the framework of Islamic theology. Predictably, it invited criticism, notably from ‘Abdu’l Haqq Muhaddiş; and Emperor Jahāngir had Sirhindi briefly imprisoned (1619).

There was, by the side of Shaikh Ahmad’s mystical revivalism, a restatement of the orthodox position in terms of what might be called the Islam of Ghazāli’s conception, a combination of Law (Sharı’a) and Mysticism (Tariqa). The restatement was, by definition unoriginal, though much learning and care often went into it. ‘Abdu’l Haqq Muhaddis (1551 1642), already mentioned, was a prolific writer on Muslim law and a recognized authority on hadīş, or sayings of the Prophet. Yet he fully accepted the sufic tradition, being the author of a volume of biographies of Indian mysties; and he inherited from his father a belief in wahdat al-wujüd. He could also sympathetically refer to the radical monotheist Kabir, while recognizing him to be neither Muslim nor Hindu.

Emperor Aurangzeb (reigned, 1659-1707), despite his patronage of the descendants of Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi, could not accept the latter’s extreme spiritual claims, and generally supported traditional and legal Islam. This was particularly shown by his commissioning of the massive work Fatāwā-i ‘Alamgiri, prepared in Arabic by Shaikh Nizām with the assistance of many scholars and designed to be a comprehensive compendium of jurists’ opinions on diverse matters, systematically arranged.

The Mughal Empire in its decline brought forth the important Muslim thinker and jurist, Shäh Walilullah (1702- 1762). He was exceptional in reflecting on the oppression of peasants and craftsmen as factors behind the decline of the Empire; an oppression he ascribed to growth of love of luxury among the ruling classes. He sometimes linked the enforcement of the various elements of the Shari’a to particular social needs, though these were rather naively formulated. Thus usury is prohibited, because if it is practiced, people would tend to abandon agriculture and crafts altogether in pursuit of usurious gain. On other matters, such as concerning Shi’as, he took an orthodox Sunni position, and translated Sirhindis polemical anti-Shi’a tract into Arabic. He was fairly harsh on non-Muslims who were to be the hewers of wood and drawers of water under an ideal Sharī’a regime. Shäh Waliullah largely accepted the sufic heritage of Islam. Claiming to be a spiritual guide (murshid) himself, he propounded an ‘inspired’ (not reasoned) reconciliation of wahdat al-wuyjüd with Sirhindī’s theory of wahdat ash-shuhūd. Hereafter the element of pantheism in Indian Islamic thought seems to have increasingly receded into the background.

Emperor Aurangzeb (reigned, 1659-1707), despite his patronage of the descendants of Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi, could not accept the latter’s extreme spiritual claims, and generally supported traditional and legal Islam. This was particularly shown by his commissioning of the massive work Fatāwā-i ‘Alamgiri, prepared in Arabic by Shaikh Nizām with the assistance of many scholars and designed to be a comprehensive compendium of jurists’ opinions on diverse matters, systematically arranged.

Christianity

Syrian Christian and Jewish communities had long lived on the Kerala coast, the Red Sea trade keeping alive their contacts with easternm Christendom and Judaism. With the arrival of the Portuguese, Catholic Christianity also arrived: Francis Xavier (1506-52) was the great pioneer of Catholic missionary activity. Another Jesuit, the Italian Robert de Nobili (1577- 1656), tried the innovation of presenting Christianity in Indian garb, incorporating the caste system by having separate churches for the upper and the untouchable castes. Much use was made by the Jesuits of the printing press to produce literature on Christianity in Indian languages. Goa became an archdiocese in 1557. The decline of Portuguese power, however, affected Catholic activity, and in 1653 a number of Syrian Christian communities in Kerala, which had been previously pressed or persuaded into accepting Papal authority, shifted to their older allegiance to Antioch. In 1759 Portugal itself suppressed the Jesuit order (‘Society of Jesus’). But Catholicism long remained the only version of Christianity that Indians could more easily become familiar with. The Dabistān, in its chapter on Christianity, provides a fairly accurate statement of Catholic beliefs, but the author seems entirely unaware of the Protestant Reformation.

The direct effect of Christianity on the mainstreams of Indian religious thought, whether Hindu or Islamic, was as yet limited; the impact became significant only in the first half of the nineteenth century.

The first Lutheran missionaries under Danish patronage, arrived in 1706 at Tranquebar (Tamilnadu), and one of them, Ziegenbalg, translated the four Gospels into Tamil in 1714. The direct effect of Christianity on the mainstreams of Indian religious thought, whether Hindu or Islamic, was as yet limited; the impact became significant only in the first half of the nineteenth century.

ARCHIVE

My Future Visit to America, 1883

— Anandibai Joshi

. . . Our subject to-day is, “My future visit to America, and public inquiries regarding it.” I am asked hundreds of questions about my going to America. I take this opportunity to answer some of them. . .

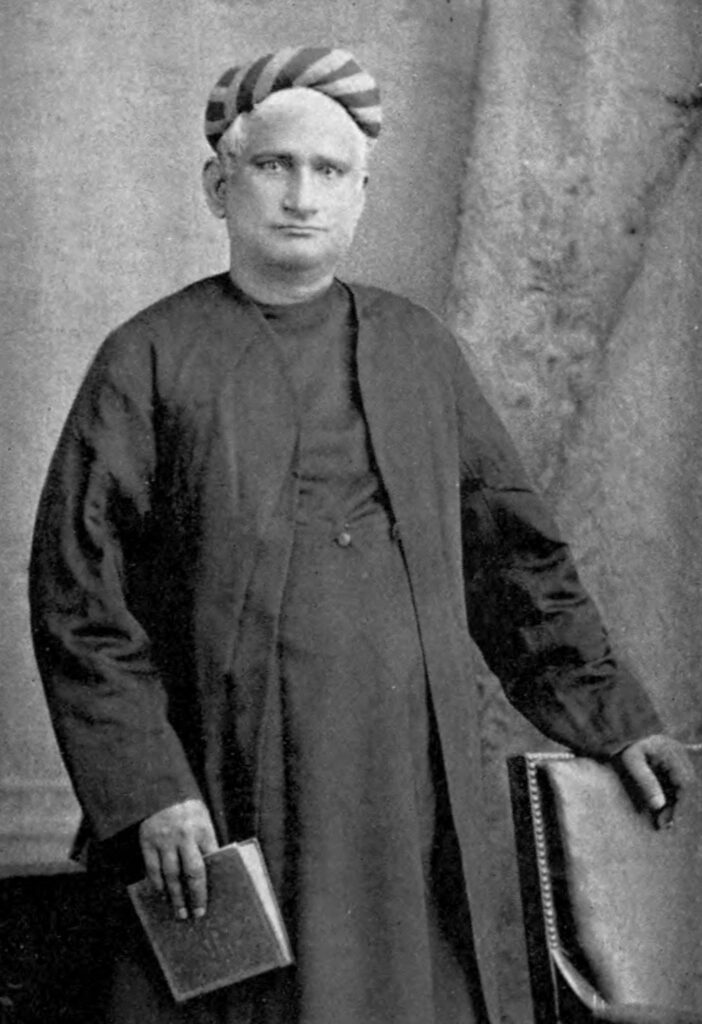

Anandibai Joshi

Why do I go to America? I go to America because I wish to study medicine. I now address the ladies present here, who will be the better judges of the importance of female medical assistance in India. I never consider this subject without being surprised that none of those societies so laudably established in India for the promotion of sciences and female education have ever thought of sending one of their female members into the most civilized parts of the world to procure thorough medical knowledge, in order to open here a College for the instruction of women in medicine. There is probably no country that would not disclose all her wants and try to stand on her own feet. The want of female doctors in India is keenly felt in every quarter. Ladies both European and Native are naturally averse to expose themselves in cases of emergency to treatment by doctors of the other sex. There are some female doctors in India from Europe and America, who, being foreigners and different in manners, customs and language, have not been of such use to our women as they might. As it is very natural that Hindu ladies who love their country and people should not feel at home with the natives of other countries, we Indian women absolutely derive no benefit from these foreign ladies. They indeed have the appearance of supplying our need, but the appearance is delusive. In my humble opinion there is a growing need for Hindu lady doctors in India, and I volunteer to qualify myself for one.

There is one College at Madras, and midwifery classes are opened in all the Presidencies; but the education imparted is defective and not sufficient, as the instructors who teach the classes are conservative, and to some extent jealous. I do not find fault with them. That is the characteristic of the male sex.

Are there no means to study in India? No. I do not mean to say there are no means, but the difficulties are many and great. There is one College at Madras, and midwifery classes are opened in all the Presidencies; but the education imparted is defective and not sufficient, as the instructors who teach the classes are conservative, and to some extent jealous. I do not find fault with them. That is the characteristic of the male sex. We must put up with this inconvenience until we have a class of educated ladies to relieve these men.

I am neither a Christian nor a Brahmo. To continue to live as a Hindu and to go to school in any part of India is very difficult. A convert who wears an English dress is not so much stared at. Native Christian ladies are free from the opposition or public scandal which Hindu ladies like myself have to meet within and without the zenana. If I go alone by train or in the street some people come near to stare and ask impertinent questions to annoy me. Example is better than precept. Some few years ago, when I was in Bombay, I used to go to school. When people saw me going with my books in my hands, they had the goodness to put their heads out of the window just to have a look at me. Some stopped their carriages for the purpose. Others walking in the streets stood laughing and crying out so that I could hear:—

“What is this? Who is this lady who is going to school with boots and stockings on?”

“Does not this show that the Kali Yuga has stamped its character on the minds of the people?”

Ladies and gentlemen, you can easily imagine what effect questions like these would have on your minds if you had been in my place!

Once it so happened that I was obliged to stay in school for some time, and go twice a day for my meals to the house of a relation. Passers-by, whenever they saw me going, gathered round me. Some of them made fun, and were convulsed with laughter. Others, sitting respectably in their verandahs, made ridiculous remarks, and did not feel ashamed to throw pebbles at me. The shopkeepers and venders spit at the sight of me, and made gestures too indecent to describe. I leave it to you to imagine what was my condition at such a time, and how I could gladly have burst through the crowd to make my home nearer!

If I go to take a walk on the Strand, Englishmen are not so bold as to look at me. Even the soldiers are never troublesome; but the Babus lay bare their levity by making fun of everything. “Who are you?” “What caste do you belong to?” “Whence do you come,” “Where do you go?” are, in my opinion, questions that should not be asked by strangers.

Yet the boldness of my Bengali brethren cannot be exceeded, and it is still more serious to contemplate than the instances I have given from Bombay. Surely it deserves pity! If I go to take a walk on the Strand, Englishmen are not so bold as to look at me. Even the soldiers are never troublesome; but the Babus lay bare their levity by making fun of everything. “Who are you?” “What caste do you belong to?” “Whence do you come,” “Where do you go?” are, in my opinion, questions that should not be asked by strangers. There are some educated native Christians here in Serampore who are suspicious; they are still wondering whether I am married or a widow; a woman of bad character or ex-communicated! Dear audience, does it become my native and Christian brethren to be so uncharitable? Certainly not. I place these unpleasant things before you, that those whom they concern most may rectify them, and those who have never thought of the difficulties may see that I am not going to America through any whim or caprice.

Anandibai Joshee graduated from Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP) in 1886. Seen here with Kei Okami (center) and Sabat Islambooly (right). All three completed their medical studies and each of them was among the first women from their respective countries to obtain a degree in Western medicine.

Why do I go alone? It was at first the intention of my husband and myself to go together, but we were forced to abandon this thought. We have not sufficient funds; but that is not the only reason. There are others still more important and convincing. My husband has his aged parents and younger brothers and sisters to support. You will see that his departure would throw those dependent upon him into the arena of life, penniless and alone. How cruel and inhuman it would be for him to take care of one soul and reduce so many to starvation! Therefore I go alone.

Shall I not be excommunicated when I return to India? Do you think I should be filled with consternation at this threat? I do not fear it in the least. Why should I be cast out, when I have determined to live there exactly as I do here? I propose to myself to make no change in my customs and manners, food or dress. I will go as a Hindu, and come back here to live here as a Hindu. I will not increase my wants, but be as plain and simple as my forefathers, and as I am now. If my countrymen wish to excommunicate me, why do they not do it now? They are at liberty to do so. I have come to Bengal and to a place where there is not a single Maharashtrian. Nobody here knows whether I behave according to my customs and manners, or not. Let us therefore cease to consider what may never happen, and what, when it may happen, will defy human speculation.

Shall I not be excommunicated when I return to India? Do you think I should be filled with consternation at this threat? I do not fear it in the least. Why should I be cast out, when I have determined to live there exactly as I do here? I propose to myself to make no change in my customs and manners, food or dress. I will go as a Hindu, and come back here to live here as a Hindu.

What will I do if misfortune befall me? Some persons fall into the error of exaggerated declamation, by producing in their talk examples of national calamities and scenes of extensive misery which are found in books rather than in the world, and which, as they are horrid, are ordained to be rare. A man or a woman who wishes to act does not look at that dark side which others easily foresee. On necessary and inevitable evils which crush him or her to dust, all dispute is vain. When they happen they must be endured, but it is evident they are oftener dreaded than experienced. Whether perpetual happiness can be obtained in any way, this world will never give us an opportunity to decide. But this we may say, we do not always find visible happiness in proportion to visible means. It is not a thing which may be divided among a certain number of men. It depends upon feeling. If death be only miserable, why should some rejoice at it, while others lament? On the other hand, death and misery come alike to good and bad, virtuous and vicious, rich and poor, travelers and housekeepers; all are confounded in the misery of famine and not greatly distinguished in the fury of faction. No man is able to prevent any catastrophe. Misery and death are always near, and should be expected. When the result of any hazardous work is good, we praise the enterprise which undertook it; when it is evil, we blame the imprudence. The world is always ready to call enterprise imprudence when fortune changes.

Some say that those who stay at home are happy, but where does their happiness lie? Happiness is not a readymade thing to be enjoyed because one desires it. Some minds are so fond of variety that pleasure if permanent would be insupportable, and they solicit happiness by courting distress. To go to foreign countries is not bad, but in some respects better than to stay in one place. [The knowledge of history as well as other places is not to be neglected. The present state of things is the consequence of the former, and it is natural to enquire what were the sources of the good that we enjoy or the evils we suffer. To neglect the study of sciences is not prudent; it is not just if we are entrusted with the care of others. Ignorance when voluntary is criminal, and one may perfectly be charged with evils who refused to learn how he might prevent it. When the eyes and imagination are struck with any uncommon work, the next transition of an active mind is to the means by which it was performed. Here begins the true use of seeing other countries. We enlarge our comprehension by new ideas and perhaps recover some arts lost by us, or learn what is imperfectly known in our country. So I hope my going to America will not be disadvantageous.]

[I have seriously considered our manners and future prospects and find that we have mistaken our interests.] Everyone must do what he thinks right. Every man has owed much to others. His effort ought to be to repay what he has received. [This world is like a vast sea, mankind like a vessel sailing on its tempestuous bosom. Our prudence is its sails; the sciences serve us for oars; good or bad fortunes are the favorable or contrary winds and judgement is the rudder; without this last the vessel is tossed by every billow and will find ship-wreck in every breeze.] Let us follow the advice of Goldsmith who says: “Learn to pursue virtue of a man who is blind, who never takes a step without first examining the ground with his staff.” I take my Almighty Father for my staff, who will examine the path before He leads me further. I can find no better staff than He.

I ask my Christian friends, “Do you think you would have been saved from your sins, if Jesus Christ, according to your notions, had not sacrificed his life for you all?” Did he shrink at the extreme penalty that he bore while doing good? No, I am sure you will never admit that he shrank! Neither did our ancient kings Shibi and Mayurdhwaj. To desist from duty because we fear failure or suffering is not just. We must try. Never mind whether we are victors or victims. Manu has divided people into three classes.

And last you ask me, why I should do what is not done by any of my sex? [To this I cannot but say that we are bound by the rights of society to the labours of individuals. Everyone has his duty and he must perform it in the best way he can; otherwise his fear and backwardness are supposed to be a desertion of duty. It is very difficult to decide the duties of individuals. It is enough that the good of the whole is the same with the good of an individual. If anything seems best for mankind, it must evidently be best for an individual and that duty is to try one’s best, according to his sentiments to do good to the society.] According to Manu, the desertion of duty is an unpardonable sin. So I am surprised to hear that I should not do this, because it has not been done by others. [I cannot help asking them in return “who should stand the first if all will say so?”] Our ancestors whose names have become immortal had no such notions in their heads. I ask my Christian friends, “Do you think you would have been saved from your sins, if Jesus Christ, according to your notions, had not sacrificed his life for you all?” Did he shrink at the extreme penalty that he bore while doing good? No, I am sure you will never admit that he shrank! Neither did our ancient kings Shibi and Mayurdhwaj. To desist from duty because we fear failure or suffering is not just. We must try. Never mind whether we are victors or victims. Manu has divided people into three classes. [Those who do not begin for fear of failure, are reckoned among the meanest; those who begin but give it up through obstacles belong to the middle class; and those who begin but [do] not give it up till they attain success, through repeated difficulties, are the best. Let us not therefore be guilty of the very crime we absolutely hate. The more the difficulties, the greater must be the attempt. Let it be our boast never to desist from anything begun. Sufferance should be our badge.]

The Hindu Sea Voyage Movement in Bengal, 1894

— Standing Committee on the Hindu Sea-Voyage Question