ARCHIVE

Origin of the Kodavas

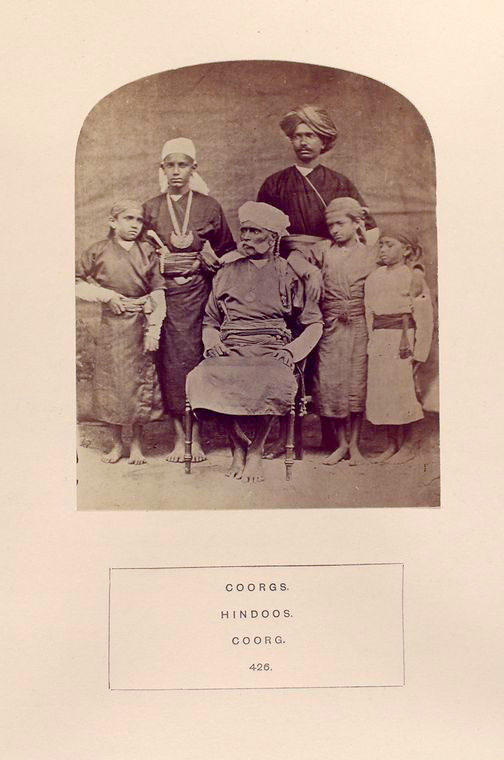

Our knowledge of the pre-history of Kodagu and the Kodavas is very scanty. There are no written documents or inscriptions from which we could deduce a credible story regarding the origin of the Kodavas. Even the history of Kodagu till the 17th century is very scanty and we find no mention of the Kodavas in the pages of the history of this period.

But many attempts have been made by various historians, anthropologists and others to unravel the mystery regarding the origin of the Kodavas. Especially after the advent of British rule in Kodagu many westerners and others have bestowed their attention on this subject. Having no written evidences or historic documents or stone inscriptions to probe their origin, efforts were made to unfathom the secret with the help of other material evidences that were available.

Pre-historic dolmens or burial cairns were found in Kodagu as in other parts of South India. Though these cairns throw some light on the life of those pre-historic-people, we cannot form an opinion as to who they were. Whether the remains that are found were of the Kodavas or that of the original inhabitants of this tract of land viz., Yeravas, Holeyas, Kudiyas, etc., is not clear.

The first discovery of the dolmens in large numbers was made by Lt. Mackenzie in 1868 on a bane near Virajpet. Capt. Rob Cole the then police superintendent of Kodagu followed it up and his excavations yielded interesting results. All the cairns found are either level with the ground or their tops crop up just a little out of it. When laid bare they present a stone chamber? of 7x4x5 feet composed of four upright granite slabs 7 or 8 inches thick and a cup stone with projects over the upright. The flooring is likewise of stone. The narrow front slab has an aperture of an irregular curve nearly two feet in diameter broken out from the top and generally facing east. Sometimes a compartment may be two-chambered. These cairns are either solitary or in groups, in some cases forming regular rows.

The relics found in them are peculiarly shaped pottery buried in the earth that nearly filled the chambers. These vessels contain earth, sand, bones, iron spearheads and beads. The pottery consists of chatties, and urns of burnt clay and is of a lead or black colour. They are smooth and shining and can hardly be said to be glazed. Bones, ashes and bits of charcoal are usually found at the bottom of the urns grains like paddy. ragi have also been found inside the chambers. Beads of red cornelian of cylindrical shape are occasionally met within the smaller pottery. The iron implements, spears and arrowheads are hardly distinguishable. These cairns apparently were resting places of the earthly remains, of a generation that existed anterior to the historical records of the present local races. The Kodavas call the dolmens as “pandukulis” or dwellings of the pandus. However, these pre-historic relics do not shed any light on the origin of the Kodavas.

Since the dawn of history the Kodavas are said to be the dominant community in Kodagu. The name of the land itself denotes that only after the advent of the Kodavas, the land took its name as Kodagu. Historians and other research scholars opine that the Kudiyas, Yerawas, and Kembatti Holeyas were perhaps living in Kodagu as the original inhabitants when the Kodavas came on the scene.

Since the dawn of history the Kodavas are said to be the dominant community in Kodagu. The name of the land itself denotes that only after the advent of the Kodavas, the land took its name as Kodagu. Historians and other research scholars opine that the Kudiyas, Yerawas, and Kembatti Holeyas were perhaps living in Kodagu as the original inhabitants when the Kodavas came on the scene.

The migration of Kodavas to Kodagu was set down by some of the European historians to the third century A.D. At that time according to them the servile or plebian class in Kodagu must have been composed of the Yeravas, Kurubas, Male-kudi yas and Holeyas. The Kodavas having conquered them formed themselves into an aristocracy.

The Kodagu inscriptions, copper plates and writings on palm leaves unearthed so far hardly throw any light on the Kodavas. However the first mention about the Kodavas was found in the Palpare inscription found in Nallur village in South Kodagu which is published in the Imperial Gazetteer of India 1908, vol XI. page 20, in which it is said.

“In 1174 Ballala II of Mysore sent his general Bettarasa to fight against the Chengalva king in Kodagu and in the fight that ensued at Palpare, Bettarasa was victorious and built a township at Palpare as his capital. But after some time Pemma Veerappa joined by Badigondeya Nandideva, Udayaditya of Kurchi and the Kodavas of all the nads marched against Palpare and attacked Bettarasa, who seems to have got the worst of it at first but was victorious.”

This inscription though does not shed any light on the Kodavas, gives an idea that the Kodavas were the dominant race in Kodagu during the 12th century. Though we are nowhere near the solution regarding the origin of the Kodavas we shall have a quick glimpse of the various efforts made by several books, people and researchers in quest of the object.

The first mention about the Kodavas was found in the Palpare inscription found in Nallur village in South Kodagu which is published in the Imperial Gazetteer of India 1908

The Cauvery Purana the oldest literature pertaining to the family deity of the Kodavas viz., Cauvery and the origin of river Cauvery after her, narrates that the Kodavas are the descendents of king Chandraverma of the Kadamba dynasty who ruled over Kodagu from the fourth century to the middle of the sixth century. Kadamba rule over Kodagu is recent and comprises subsequent history whereas Cauvery Purana dates back to a much earlier time. The Cauvery Purana mentions that when their family deity Cauvery transformed herself into the holy river, the Kodavas, of the land were present in good number and she blessed and assured them of her protective grace. This shows that the Kodavas were there before the birth of river Cauvery. This being purely a Puranic story we cannot base our findings on that and as Capt. Rob Cole rightly avers, the mythical nature of Cauvery Purana lacks credibility and it does not help us in any way in finding the origin of the Kodavas.

Col. Wilks in his book “History” expostulates the theory of the Kadambas and says that the Kodavas “descended from the conquering army of the Kadamba kings.” He further says that the first colonist were made out to have migrated from the Kadamba kingdom-Banavasi. Lewis Rice supports this view and says that it is consistent with what is known as the Kadamba history as corroborated by the modern annals of Kodagu: He expresses that the tales of Chandrashekhara, and Chitrashekhara as expounded by professor Wilson lend support to the same view.

Kadambas ruled over Karnataka from the third century A.D. to the middle of the sixth century. But we hear about Kodavas and Kodagu from a much earlier date even from the time of the Ramayana and Mahabharata that is, from the fourth or fifth century before Christ.

But we must note one important factor. The kings and chieftains who ruled over Kodagu were always aliens. A powerful chieftain or a king from outside comes with his army and invades a country, over-comes the opposition if any and establishes his suzerainty. With the invader some people of his ilk and a contingent of his soldiers may settle in the conquered land. But the majority of the people of the subdued land remains as they are. Thus the saga of conquests and establishment of kingdoms does not much change the ethnic and social structure of society.

The kings and chieftains who ruled over Kodagu were always aliens. A powerful chieftain or a king from outside comes with his army and invades a country, over-comes the opposition if any and establishes his suzerainty. With the invader some people of his ilk and a contingent of his soldiers may settle in the conquered land. But the majority of the people of the subdued land remains as they are. Thus the saga of conquests and establishment of kingdoms does not much change the ethnic and social structure of society.

The Kodava community had nothing to do with the Kadamba rulers or the subsequent ones. Whoever ruled Kodagu, the Kodava community maintained their separate identity, culture and customs as could be vouched from the recent happenings during Lingayat and British rule over Kodagu. Let alone the ethnic polarisation, the Kodavas were not influenced by the customs, mode of life, religious beliefs, dress etc.. of the rulers though there may be minor adaptations in the style of dress etc. Hence the Kadamba theory does not stand any charice of acceptance.

Some research scholars take back the advent of the Kodavas to the Mohenjodaro period. Attempts were made in the past to establish the existence of the Kodavas during the Vedic period. There is an assumption By Rev. Heras that there occurs the name of the Kodavas and some of the seals and references belonging to the pre-vedic (?) Mohenjodaro and Harappa culture refer to the Kodavas. But these are theories that are still in the realm of speculation.

Lt. P. Connor in his book “Memoirs of Kodagu survey (1817) says that the Kodavas themselves do not know anything about their origin. There is no trace of any helpful material to find out their origin of anything even to deduce a reasonable and convincing assumption. Though there are no historical data or evidences to establish their origin, there is no doubt that the Ködavas are one of the oldest races. Their land being a forest-ridden area with no outside contact and moreover, there being nothing attractive to arrest the covetous eyes of conquerors and even if anyone attempted the forbidding hilly terrain inclement weather and the heavy monsoon completely thwarted and made outside conquest well nigh impossible. As such it remained for years cut off from the external world and the face preserved its purity, its customs, traditions and culture unsullied.

Sri Erskine Perry who also failed to establish the origin of the Ködavas points out that “the Kodavas have no resemblance to any of the races of south India and that it clearly indicates that they must have come from outside“. He also describes that the kodavas are by far the finest race he had seen in India in point of independent bearing good looks and all the outward signs of well-being”.

Sri Erskine Perry who also failed to establish the origin of the Ködavas points out that “the Kodavas have no resemblance to any of the races of south India and that it clearly indicates that they must have come from outside”. He also describes that the kodavas are by far the finest race he had seen in India in point of independent bearing good looks and all the outward signs of well-being”.

Mr. L. A. Krishna Iyer in his book, “The Coorg Tribes and Castes writes that “their (Kodavas) mode of life, pride of race, impart in their whole being an air of manly independence and dignified self-assertion, well sustained by their peculiar and picturesque costumes”. Giving the maximum and minimum and the average státure and cephalic and nasal indices he concludes that “they bear no comparison with the other races of South India”. He says that “the Kodavas have a finer nose, a larger head with a distinct tendency towards brachyce phalism. Their average cephalic index is 80.6 and the nasal Index 65.2”. Giving all these details Mr. Krishna Iyer also fails to unravel the origin of the Kodavas.

Mr. Abdul Gaffar Khan who wrote a book entitled “Kodavaru Arabiyaru” (Kodavas are Arabs) assumes that the Kodavast must have migrated from Arabia. Though he does not substantiate his assumption with any reliable data he simply bases his findings on the similarity of the mode of dresses between them, This does not justify as sufficient evidence to establish the origin of a race. As a matter of fact dress patterns change from time to time and place to place according to weather and other conditions. Hence the mode of dresses can hardly be the basis to ascertain the origin of any community. We know that the Kashmiris and some tribes who live in the Himalayan region do wear dresses closely resembling the dress pattern of the Kodavas and by no stretch of imagination could one conclude that they belong to the ethnic group of the Kodavas.

Some of the educated Kodavas claim that they are the descendants of the Pandavas of Mahabharata and cite in support some of the social customs like the younger brother marrying the widow of the elder brother etc. One need not say that these are decidedly very flimsy and unreliable grounds to determine the identity of a community.

Some of the educated Kodavas claim that they are the descendants of the Pandavas of Mahabharata and cite in support some of the social customs like the younger brother marrying the widow of the elder brother etc.

Some modern research workers have classified the Kodavas with the Todas of Nilgiris, the Caucasians of the country around mount Caucasus in Russia. Some others have classified them with the Kapalas, one of the original inhabitants of Kodagu. Mr. Herbutt Rishely opines that “the Scythians (an Asian nomadic people of Asia) who were residing in the Balkans region during the fifth or the sixth century were forced by their neighbors, the Yuvachi community to migrate to the East and settle in Punjab. They built a new kingdom in Punjab. The people with bigger heads, taller physique and longer limbs who are found in the region comprising Western Punjab to South Deccan were said to be the descendants of these Scythians. At that time cattle-raring being the principal occupation, they migrated with their herds of cattle in search of grazing plains and that is how, we find their progeny viz.. the people with larger heads, longer limbs and taller physique scattered along the western ghats and especially in Kodagu.”

Some recent research workers are definite about the Kodavas coming from the Dravidian stock. Though almost all the recognised anthropologists are unanimous in denouncing this assumption yet the protagonists of Dravidian theory argue that the Kodavas and the Todas of Nilgiris belong to the same ethnic group of the Dravidian family. They say that their traits are biologically useful and related to mental capacity and intellectual endowment. They further say that the mountainous habitat, climate, food, contact with Western races are responsible for what the Kodavas are today and these factors have differentiated them from the people of the plains. They argue that the jungles of Kodagu satisfied their highly developed propensities of hunting and outward life and they were noted for their predatory excursions into the country of their wealthier and less war-like neighbours. It is their conclusion that these traits are still with them and even at the present time they revel in their fighting and sporting qualities, which have ample scope in their socio and religious ceremonies and customs.

There are others who are of definite opinion that the Kodava language is nothing but a mixture of the Southern languages of the Dravidian group and on that basis they are definite that the Kodavas belong to the Dravidian heritage. They further say that if the Kodavas had come from the North or elsewhere they should atleast have had their own language, but in reality Kodava language is only a dialect a mixture of Dravidian languages. They quote Richtor to substantiate that the “Kodava language has a close relationship with the other Dravidian languages, but being neither cultivated beyond its colloquial use, nor possessing any original literature, it hardly deserves the distinction of being elevated into a special Dravidian language”.

These arguments of the Dravidian enthusiasts come in the realm of speculation and hardly can be reckoned as reliable data. The martial tradition of the Kodavas, the rugged nature of their home-land and the inevitable battles they had to wage against the wild animals and out-ward enemies, the inhospitable conditions of the forest area account for their highly developed martial traits but in no way or at any time they were the predators who invaded their docile neighbouring countries for loot or lucre. Their history is replete with events of high propriety, orderly behaviour and ideal neighborliness.

Regarding the issue concerning their language it is pertinent to ask the Dravidian enthusiasts as to why the Kodavas-a microscopic little community-instead of speaking one of the languages of the Southern group should speak a different language? The fact that Kodava language consists of many words and traits of the neighbouring languages does not disprove that it is an original language. Some of the recent linguists, who have done sufficient research on this language and published the grammar and compiled a vocabulary for the language say that it has many traits which we don’t find in the other Dravidian languages. They also are definite that Kodava language is of great antiquity and even older than Malayalam. As this issue is discussed at length, elsewhere in the book, it is sufficient to say here that languages which are always changing and which absorb words freely from contemporary other languages are not reliable data to determine the origin of any race or community. Once upon a time our ancestors were speaking Samskritha and it was the original language of our country but today it has yeilded place to other languages. But it does not mean that Samskritha was not the dominant and mother-tongue in our land.

The so-called authorities who easily tag the Kodava community to this or that ethnological group in South India must explain as to how a small community numbering within a lakh of people could develop and maintain a special mode of dress, a unique culture, a special way of life, a different language in spite of the heterogeneous influx and pressure of other major forces that dominated the South during the millennium. They must explain how this microscopic community could build up a tradition, which is markedly different from those of their neighbours.

The so-called authorities who easily tag the Kodava community to this or that ethnological group in South India must explain as to how a small community numbering within a lakh of people could develop and maintain a special mode of dress, a unique culture, a special way of life, a different language in spite of the heterogeneous influx and pressure of other major forces that dominated the South during the millennium.

The time of the settlement of the Kodavas in Kodagu is also a point of uncertainty. There are people who argue that the Kodavas lived during the Mohenjodaro and Harappa culture and must have migrated to the South at that time, The Indus Valley Civilization is said to have thrived for thousand years from 2500.B.C According to modern dating this is prior to the happenings of the epics Mahabharata and Ramayana. They say that there is the mention of “Kroda Desha” in Mahabharata and it refers to Kodagu only. This can only be an assumption and does not stand any scientific scrutiny. However there are certain credible assumptions to show that the Kodavas must have migrated to Kodagu much before the Christian era.

We know from history about the Greek invasion of India during the rule of Chandragupta Maurya. Alexander of Greece with an army of 40, 000 men, with the intension of conquering the world marched towards India. He crossed the Hindu-Kush and wanted to conquer Maghada (Southern part of Bihor). He had heard about this powerful kingdom and its wealth and grandeur. But the soldiers of Alexander refused to go further and he had to abandon his march appointing Selukus his general to rule over the conquered kingdoms. Selukus and his fellow soldiers settled down in a country called Bactria. After sometime when they saw that there were no powerful rulers they came down and conquered Punjab and ruled that part of the country for over a hundred years. One of their kings was Menander. Hel was a wise and good king. He was completely taken by the life and philosophy of the Indians and adopted Indian ways of life and called himself an Indian. His followers also adopted Indian ways of life and became Indians, and in the course of time they mingled with the local people giving rise to a new community with broader heads taller stature and sturdier limbs.

We know from history that when Alexander withdrew from India leaving Selukus, Chandragupta Maurya, the young and powerful king who wanted to be an empire builder like Alexander, himself, fought against Selukus, defeated him and married his daughter. Thus we see a fusion of races. How this new race came down to the South is corroborated by various historians.

“What is the earliest date in the historical period when the South came into contact with the North? The answer to this question is not very precise. Of course we have Ashoka’s inscriptions located in the various parts of Karnataka, but what about the pre-Ashokan period? Certain epigraphs of the 12th and 13th centuries in the Kannada language found in the Shimoga district refer to the rule of Nandas over Karnataka. We know that Ashoka conquered Kalinga but who among the Mauryan kings conquered the South is not known. Prof. Nilakanta Sastri suggests that the Mauryans came by their southern possessions as a matter of course by over-whelming the Nandas. The coming of Chandragupta Maurya to Sravanabelagola with his teacher Bhadrabhahu is well-known. The smaller hill at Sravanabelagola where the teacher and the pupil lived is referred to as Katavapura and Chandragupta lived here for twelve years after his guru’s death and the place is named after him as Chandragiri” (Karnataka through the Ages, page 99).

“Bindusara son of Chandragupta ruled in the South (298 272 B.C.) including certain portions of Mysore then known as Mahismamandala. This fact has been conceded by historians on the basis of Taranath the tibetan historian and Mamoolnar the Tamil poet. We have ample proof of the sway of Ashokan rule in the shape of pillars and rock edicts at Brahmagiri and other places of Chitradurga and other districts. The Brahmagiri excavations by the Archaeological Survey of Mysore in 1939 and the Archaeological Survey of India in 1947 respectively have amply unearthed objects belonging to the Mauryan period. Sir Mortimer Wheeler excavated some of the megalithic burials at Brahmagiri and dated them to the period of Ashoka. It is significant to note that the megalithic monuments are locally known as Mauryana” or “Morera mane” by the people thus associating them with the Mauryas”.

This conclusively proves that there was migration of the people of the North to the South as far back as the Mauryan period i.e,. round about 200 years before the Christian era. As explained above the inter-mixing of the Greeks, Indians, and the Pahalavas of Persia gave rise to a new community known as the Aryans. The word Arya in Samskritha means noble. This mingling gave rise to a new ethnic group of Aryans with bigger heads, taller stature, longer and sturdier limbs, grecian nose and special cephalic indices other than the local population,

The people being nomadic were moving from place to place with their cattle in search of grazing grounds gradually moved South. With the extension of the Mauryan Empire till Mysore (Mahishamandala) these sturdy people settled along the Western coast as far as Kodagu.

The people being nomadic were moving from place to place with their cattle in search of grazing grounds gradually moved South. With the extension of the Mauryan Empire till Mysore (Mahishamandala) these sturdy people settled along the Western coast as far as Kodagu.

Dr. J. H. Hutton states that, “it appears to be a much simpler and more satisfactory view to regard this stock of people as Aryans. We may suppose them to have migrated to the South and to have extended down to the West Coast as far as Kodagu forming the physical basis of several of the brachycephalic or mesatocephalic groups of Western India,”

From the above it can be safely inferred that the progenitors of the Kodava community have come from Aryan stock (Greek Indian mixture) and they migrated and settled along the Western Ghats and Kodagu at about 200 B.C. that is during the rule of the Mauryan dynasty. This brachycephalic stock which settled along the many parts of Western India could not maintain its identity as it was gradually absorbed by the local groups though we find people of longer heads, taller stature with Grecian noses here and there. But those groups who settled in Kodagu have maintained their specialities and separate entity to some extent as to be distinguished from the others. This was possible because of the mountainous and forest nature of Kodagu and the lack of communcation and outside contact with the nighbouring groups of the South. As outer contact increased this process of assimilation is being accelerated and it is but natural that in the present mode of life, and inter-mingling, the Kodava way of life, language, etc have been much influenced by the neighbours. Though this process is going on, the small community of the Kodavas have maintained their separate identity, culture, customs and other social traits with zealous care.

From the above it can be safely inferred that the progenitors of the Kodava community have come from Aryan stock (Greek Indian mixture) and they migrated and settled along the Western Ghats and Kodagu at about 200 B.C. that is during the rule of the Mauryan dynasty.

It is estimated that there are in India about three thousand different communities. Among them perhaps the Kodavas are one of the smallest numbering not even a lakh. This microscopic community with its great cultural tradition, with its high water mark of independence, integrity and valour has etched an indelible mark in the annals of Indian history.

This excerpt has been carried from B.D. Ganapathy’s Kodavas.

ARCHIVE

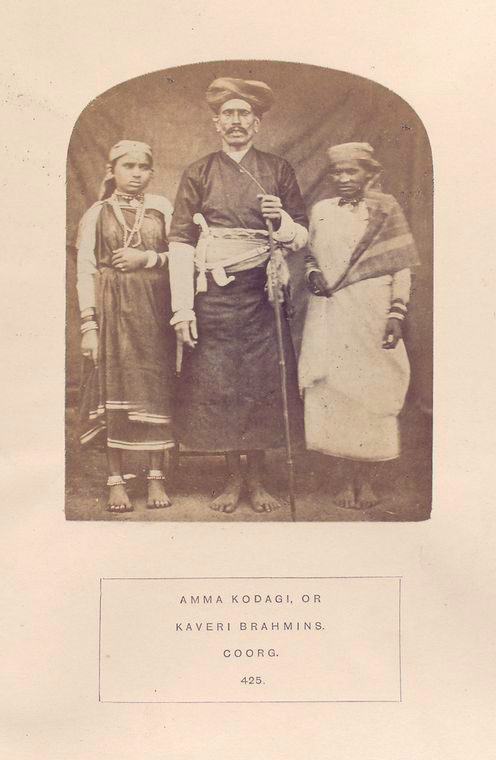

Today, it is difficult to imagine Hinduism without temples, or even to imagine temples as being more than places for worship. That was not the case during the time of the early Chalukyas. Then, the idea of building permanent shrines to ‘Hindu’ gods was somewhat of an innovation. Buddhists, on the other hand, were used to worshipping idols and

congregating around permanent religious institutions such as monasteries or stupas, and folk religion in the subcontinent always had a strong idol-based aspect to its worship of yakshas and other fertility deities. But orthodox Hinduism, even up to the early centuries CE, had still relied primarily on Vedic rituals – expensive and difficult undertakings for kings, and rather ephemeral in how they displayed royal power and political messages. These rituals were performed in temporary altars, built specifically to perform a sacrifice and destroyed after.

But by the fourth century, aided by the patronage of the Gupta emperors of northern India, Hindu cults adopted permanent iconic representations of gods and introduced radical theological innovations in a bid to increase popularity and capture patronage. In the Vedic worldview, the gods, who always remained invisible presences through the rituals, needed periodic sacrifices from mortals to help them defeat anti-gods and bring rains. In the new, temple-based, Puranic Hinduism, gods such as Shiva and Vishnu were embodied as idols and were declared Supreme. They no longer needed sacrifices to help them order the cosmos, but went about their business according to a plan that mortals could not hope to understand. Mortals could also bring them to Earth as permanent residents in temples, not just as temporary visitors to sacrifices. There, they could propitiate these mighty deities with new rituals that were presented as reworked versions of Vedic sacrifices: periodic, daily offering of animals, food, flowers and so on. This innovation proved popular with rich and poor alike. Royals across northern India soon started to build shrines to Hindu gods, while continuing their patronage of existing Buddhist and Jain institutions.

However, temples did not spread only for devotional reasons.

Vishnu image in Badami Cave 3

Major temples and the deities they enshrined were associated with legends contained in the Puranas, and were believed to have potent boons to offer devotees and donors. They attracted pilgrims and, more importantly, commercial activity, creating hubs where India’s flourishing religious cults could preach, squabble, sing, celebrate and make money. The popularity of temple-based Hinduism also led to the gradual creation of new religious communities, more amenable to supporting the activities of warlike aristocrats who claimed a special relationship with the gods8 – all of which were in stark contrast to what Buddhists in south India were willing or able to offer, as will be seen later. Building a temple could also help royals curry favour with existing groups of worshippers, monastic communities, pilgrims and so on. The crowds of devotees that visited temples would frequently hear of the land grants and military exploits of kings, and associate them with the inscrutable world-ordering activities of deities, in contrast to the moralistic tales of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas that they might hear in a stupa. As one scholar puts it, the rise of ever more elaborate temples and the growth of royal power inevitably went hand in hand.

This was why it was so important for medieval kings to build temples, though we may often misinterpret these activities as stemming purely from devotion. Early Chalukya temples, in particular, show us how medieval kings used these buildings as a crucial aspect of their power. Chalukya temples are replete with subtle and not-so-subtle political messages.

Keshava temple, Somnathapura, Karnataka. Credit: Human History In Brief

Pulakeshin I’s earliest attested activities were Vedic sacrifices, meant to establish his status amongst other elites conversant with their meaning – kings, Brahmins, generals, poets, astrologers – rather than the average Deccani. By the end of his reign, he had begun to seek more permanent means to express his power to the mass of his subjects. His imperial title, Sri-Prithivi-Vallabha, had already established his relationship to Vishnu. But he also used the soft sandstone of the cliffs of Vatapi to state his personal relationship to the other great god of temple-based Hinduism Shiva – whose cults were already popular in the northern Deccan.

Pulakeshin I’s sculptors were ordered to make sculptures totally unique to the Chalukyas, expressing royal support for these new religious practices. One such image, a spectacular eighteen-armed image of a dancing Shiva still welcomes visitors to the cliffs of Vatapi (modern-day Badami). The god’s arms swirl around him like a blooming lotus, his left foot poised an instant away from striking the ground.

Pulakeshin I’s two warlike sons (Mangalesha and Pulakeshin II’s father) also engaged in a spurt of cave temple building in Vatapi and other Chalukya towns in the Malaprabha valley, such as Aryapura (modern-day Aihole). Ancient sacred springs and wells and dolmen burial sites, where the indigenous peoples of the land had congregated for centuries to celebrate nature’s rhythms, were now incorporated into the sites of flashy new temples. Of course, the Chalukyas by no means confined their patronage to Hindu gods; the religious composition of early medieval India was very much in flux, and they built Buddhist and Jain temples to appeal to those audiences as well.

Durga temple, Aihole, Karnataka

Today, the constructions of the early Chalukya kings are among the oldest known temples in southern India, and they tell us a fair bit about the political clashes and competitive religious environment of the sixth century. For example, the Kadambas of Banavasi, their deadly rivals, associated themselves with the Saptamatrikas, goddesses of victory and liberation with roots in ancient cults. Pulakeshin I’s sons went out of their way to use images of these Seven Mothers in their cave temples, competing with the Kadambas to claim the favour of these popular deities.

Mangalesha commissioned an image of the original Sri-Prithivi-Vallabha, Varaha, the man–boar form of Vishnu, who had earned the love of the goddess Earth by rescuing her from a demon at the time of the Great Deluge. The sculpture, evidently meant to establish a visual parallel with the king, can be seen in Cave 3 in modern-day Badami. To this day it retains traces of its original lustrous blue paint. Mangalesha’s campaigns against the Kadambas and Kalachuris, it seems to say, are analogous to Vishnu’s rescue of Earth from darkness. This Chalukya king’s association with Varaha would go on to become one of the subcontinent’s most iconic visual motifs: his nephew Pulakeshin II would use the boar as his battle standard, and it would continue to be used intermittently for nearly one thousand years after, even during the time of the Deccan empires of Bijapur and Vijayanagara.

Pulakeshin II inherited some of his uncle Mangalesha’s skill at visual propaganda, introducing innovations of his own to Chalukya political messaging. He, however, wanted to make a new sort of temple – not the dark, concealed cave temples that the Deccan was familiar with, but elegantnew structures that embraced open air, space, and light. His sculptors and sthapatis (‘establishers’, or master architects) oversaw the removal of great blocks of sandstone from the cliffs of Vatapi. These were then assembled into some of the oldest surviving free-standing temples in southern India. Their clean lines were adorned with subtle sculptural motifs – artistic representations of gods, myths and miniature shrines. Built to support their own weight through careful balancing and positioning of joints, Pulakeshin II’s temples have endured nearly 1400 years of erosion.

Their design borrows from both north and south to make something new, something uniquely Deccan. The shape of Pulakeshin II’s temples, using the distinctive south Indian tiered superstructure ascending in ever-smaller layers from a wide base, seems to reflect a south-centric worldview. And yet, there are many northern influences, which would only have been included by sculptor guilds at Pulakeshin II’s express wish, in order to impress audiences in Vatapi. For example, in sculptural panels on the walls, Shiva can be seen standing straight and calm in the samabhanga posture with a snake in his right hand and a trident in his left, all of which are ‘common North Indian attributes’. These influences came by way of the northern Deccan, a region that was now firmly in Chalukya hands, though it had been a foreign country just a generation ago. Religions and goods from there were now becoming more popular in the Chalukya home territories, as these once-poor lands grew into prosperous towns and were integrated into the subcontinent’s webs of trade and religious exchange. Pulakeshin’s splendid new buildings must have been a great hit with the increasingly religious and cosmopolitan people of the Malaprabha valley, a shrewd investment of the loot he had gained from his military campaigns.

Pulakeshin II’s temples thus tell us a great deal about the complex ways in which medieval Indian elites went about the business of solidifying and perpetuating their power.

Given what temple-based Hinduism could offer to the wealthiest and most powerful people, the decline of monastic Buddhism at this time makes much more sense.

Pulakeshin II also brought innovations to other aspects of Chalukya power. Temples helped structure social activity in urban centres, with their consistent daily and seasonal rhythms where the people of the Malaprabha river valley could congregate. But their audience was limited to a radius of a few dozen miles, at most. For faraway subjects and vassals, more concise religio-political messages were needed.

Pulakeshin II now proved himself the equal of his grandfather in propaganda, inventing a legendary backstory for the Chalukyas, erasing their humble chalke-wielding past. This was interwoven with land grant formulae once used by the Kadambas, ensuring that the aura of glory that surrounded that old dynasty would now accrue to his clan.

According to Pulakeshin, the Chalukya were a clan ‘nourished by the breasts of the Seven Mothers … who have acquired an uninterrupted continuity of prosperity through the protection of Karttikeya [the war god], who have had all kings made subject to them at the sight of the boar-crest which they have acquired through the favour of the divine Narayana [Vishnu]’. He declared that they were a race of heroes sprung from a pot, a chuluka, filled with water from the Ganga by an ancestor who defended the gods from demons. In another version, the Chalukya progenitor was Brahma the Creator himself. In another, there is no pot, but there was a hero whose name is Chalukya. Finally, Pulakeshin also adopted for himself a bevy of titles designed to inspire awe among his vassals and rivals, including Satyashraya, Refuge of Truth – this would be the title by which he was remembered by his successors for centuries after.

The point of all this intense activity in architecture, iconography and political propaganda was manifold. It established that the Chalukyas had rescued the Deccan from all the darkness and anarchy that came before, just as Varaha had rescued the Earth. It established that they were no ordinary mortals, but the favourites of the most popular gods – even the gods of their erstwhile rivals. It established that they ruled over north as well as south, that their power extended into areas that had never bowed to the might of the Deccan before. And, most importantly, it laid the popular and institutional foundations for many more generations of Chalukyas to build temples, make land grants and reorder the Deccan as their ancestors had.

You can find the book here.

In the colonial period, the threat of the lecherous male gaze was used by the new patriarchy to restrict access to employment and public space for women, maintaining a patriarchal division of labour. Read how this process unfolded in our newest excerpt.

Saurav Kumar Rai

__

Was Lala Lajpat Rai's Hindu nationalism congruent with the principles of secularism? Explore our latest excerpt from Vanya Vaidehi Bhargav's fresh off-the-press book - Being Hindu, Being Indian: Lala Lajpat Rai's Ideas of Nation for more.

Vanya Vaidehi Bhargav

__

Popularly, we think that political cartoons question the powerful but what if this was not the case? What if political cartoons, replicated structures of the socially dominant? Read how in our new excerpt on political cartoons featuring Dr. Ambedkar.

Unnamati Syama Sundar

__

On Martyrs' day 2024, read the poet Sarojini Naidu's tribute to Gandhi given over All India Radio two days after his assassination.

Sarojini Naidu

__

On Republic Day, the Indian History Collective presents you, twenty-two illustrations from the first illustrated manuscript (1954) of our Constitution.

Indian History Collective

__

One of the key petitioners in the Ayodhya title dispute was Bhagwan Sri Ram Virajman. This petitioner was no mortal, but God Ram himself. How did Ram find his way from heaven to the Supreme Court of India to plead his case? Read further to find out.

Richard H Davis

__

Labelled "one of the shortest, happiest wars ever seen", the integration of the princely state of Hyderabad in 1948 was anything but that. Read about the truth behind the creation of an Indian Union, the fault lines left behind, and what they signify

Afsar Mohammad

__

How did Bengal get a large Muslim population? Was it conversion by ruling elites was there something deeper at play? Read Dr. Eaton's classic essay to find out.

Richard Eaton

__

An excerpt from Shailaija Paik's new book 'Vulgarity of Caste' that documents the pivotal role Tamasha (the popular art form) has played in reinforcing and producing caste dynamics in Marathi society.

Shailaja Paik

__

In 1942, two sub-districts in Bengal declared independence and set up a parallel government. The second part of our story brings you archival papers in the form of letters, newspaper reports, and judicial records documenting this remarkable movement.

Indian History Collective

__

In 1942, five years before India was independent, two sub-divisions in Bengal not only declared their independence— they also instituted a parallel government. The first in a new series.

Indian History Collective

__

In his own words, read Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi's views on the proselytising efforts taken on by the organisations such as Arya Samaj, Tabhligi Jamaat, and the Church Missionary Society of England.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

__

TIMELINE

-

2500 BC - Present

2500 BC - Present Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas -

2200 BC to 600 AD

2200 BC to 600 AD War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India -

400 BC to 1001 AD

400 BC to 1001 AD The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India -

600CE-1200CE

600CE-1200CE The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power -

c. 700 - 1400 AD

c. 700 - 1400 AD A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History -

c. 800 - 900 CE

c. 800 - 900 CE ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess -

1192

1192 Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India -

1200 - 1850

1200 - 1850 Temples, deities, and the law. -

c. 1500 - 1600 AD

c. 1500 - 1600 AD A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India -

1200-2020

1200-2020 Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra -

1530-1858

1530-1858 Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan -

1575

1575 Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court -

1579

1579 Padshah-i Islam -

1550-1800

1550-1800 Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal -

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ -

1553 - 1900

1553 - 1900 What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? -

1630-1680

1630-1680 Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? -

1630 -1680

1630 -1680 Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times -

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D.

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power -

1818 - Present

1818 - Present The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon -

1831

1831 The Derozians’ India -

1855

1855 Ayodhya 1855 -

1856

1856 “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib -

1857

1857 A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 -

1858 - 1976

1858 - 1976 Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow -

1883 - 1894

1883 - 1894 The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate -

1887

1887 The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar -

1893-1946

1893-1946 A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste -

1897

1897 Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy -

1913 - 1916 Modern Review

1913 - 1916 A Young Ambedkar in New York -

1916

1916 A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier -

1917

1917 On Nationalism, by Tagore -

1918 - 1919

1918 - 1919 What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? -

1920 - 1947

1920 - 1947 How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi -

1921

1921 Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) -

1921 - 2015

1921 - 2015 A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar -

1915-1921

1915-1921 The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore -

1924-1937

1924-1937 What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? -

1900-1950

1900-1950 Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society -

1925, 1926

1925, 1926 Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) -

1928

1928 Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? -

1930 Modern Review

1930 The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality -

1932

1932 Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi -

1933 - 1991

1933 - 1991 Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian -

1935

1935 A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address -

1865-1928

1865-1928 Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism -

1935 Modern Review

1935 The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge -

1936 Modern Review

1936 The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ -

1936

1936 Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 -

1936 Modern Review

1936 The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament -

1936

1936 Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 -

1936

1936 A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature -

1936 Modern Review

1936 The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election -

1937 Modern Review

1937 The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati -

1938

1938 Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) -

1942 Modern Review

1942 IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) -

1942-1945

1942-1945 IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) -

1946

1946 Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 -

1946

1946 An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose -

1946 – 1947

1946 – 1947 “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly -

1946-1947

1946-1947 VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India -

1916 - 1947

1916 - 1947 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read -

1947-1951

1947-1951 Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us -

1948

1948 “My Father, Do Not Rest” -

1940-1960

1940-1960 Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad -

1948

1948 The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation -

1949

1949 Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ -

1950

1950 Illustrations from the constitution -

1951

1951 How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed -

1967

1967 Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari -

1970

1970 R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography -

1973 - 1993

1973 - 1993 Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh -

1975

1975 The Emergency Package: Shadow Power -

1975

1975 The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control -

1977 – 2011

1977 – 2011 Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal -

1984

1984 Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star -

1916-2004

1916-2004 Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” -

2008

2008 Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? -

2006 - 2009

2006 - 2009 Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee -

2020

2020 The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read -

2021

2021 Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives