ARCHIVE

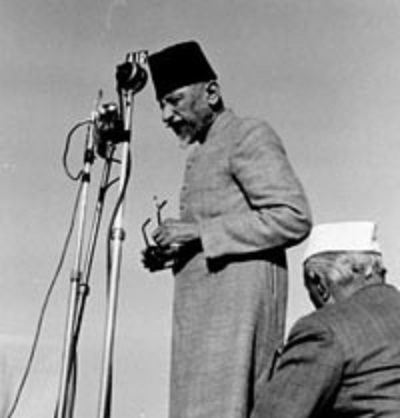

New Leaders and Their Different Ideologies

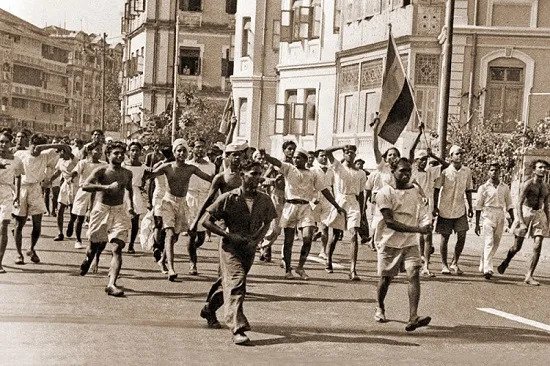

After the failure of the non-cooperation movement, the Indian people had lost hope. Communal conflict between Hindus and Muslims wiped out the little resolve that still remained. But once a sense of awakening has come upon a nation, it cannot remain asleep for long. In just a few days, the public is back on its feet and ready for battle. Today, India is full of life and vigour again; it is awake. We may not see clear signs of a great mass movement, but the ground is certainly being prepared for it. Many new leaders with a modern sensibility are emerging. Young leaders are at the forefront this time, and youth movements are proliferating. Only young leaders are commanding the attention of patriotic-minded Indians. Even the tallest veteran leaders are being left behind.

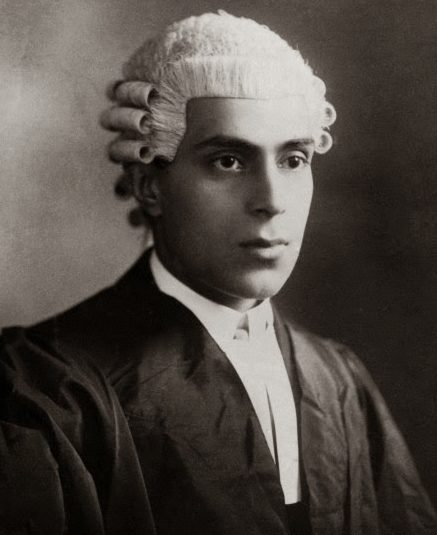

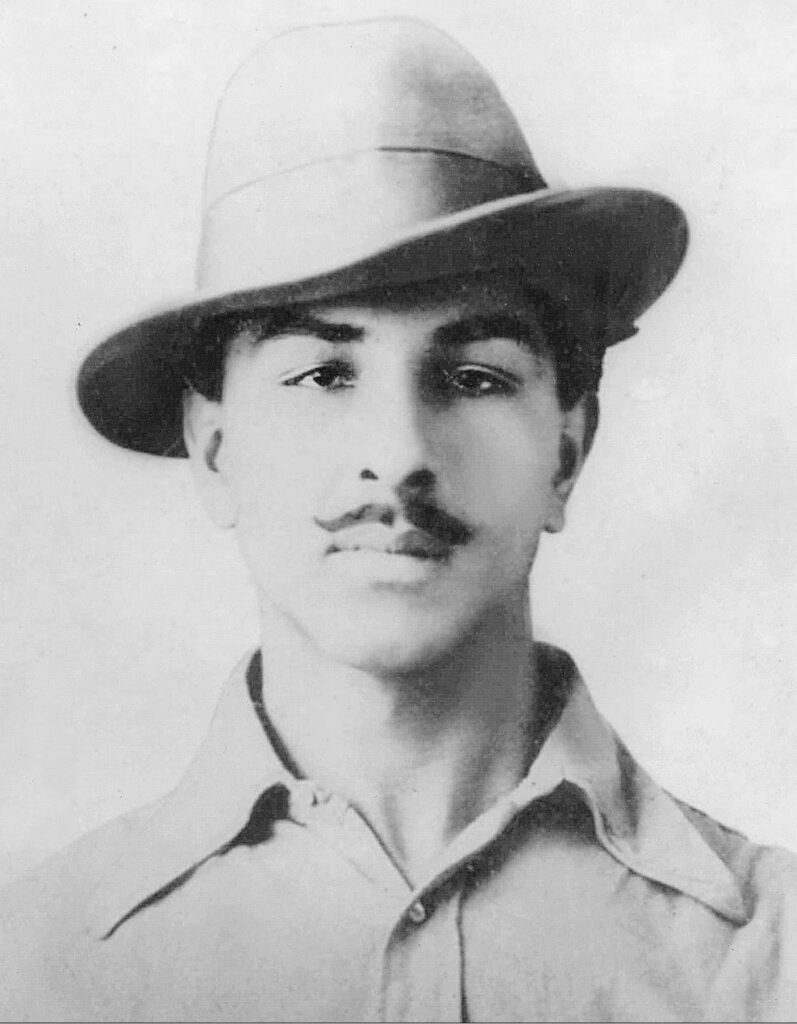

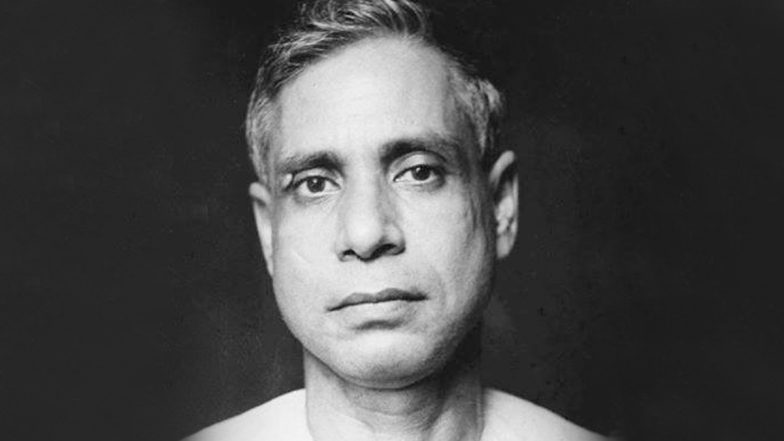

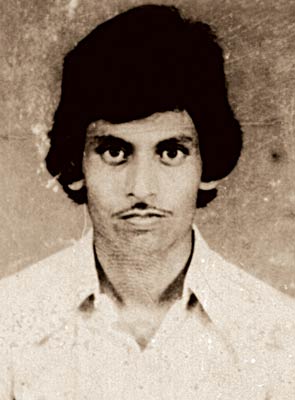

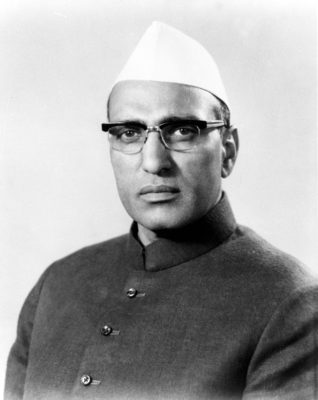

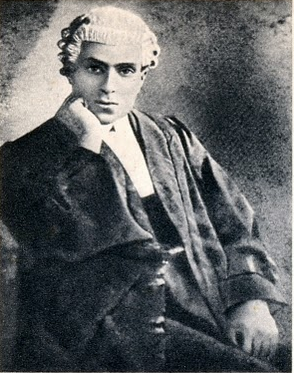

Bhagat Singh

Many new leaders with a modern sensibility are emerging. Young leaders are at the forefront this time, and youth movements are proliferating. Only young leaders are commanding the attention of patriotic-minded Indians.

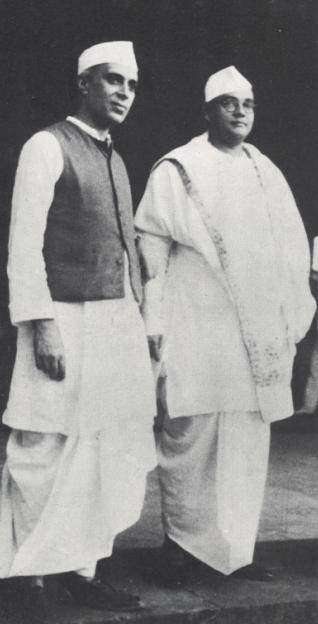

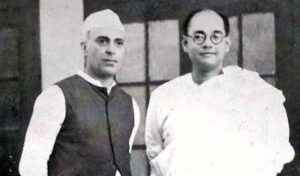

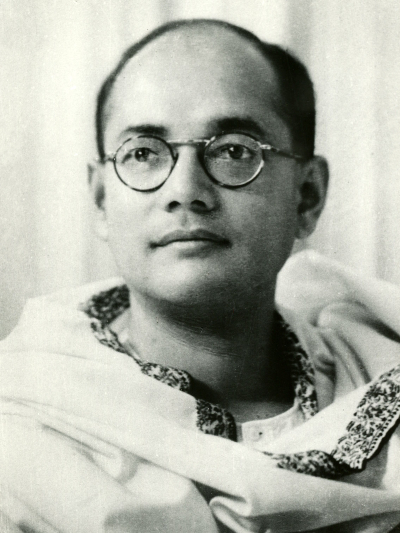

The leaders who have gained prominence this time are the venerable Subhash Chandra Bose of Bengal and the eminent Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. These are the two leaders who appear to be rising above all others in India and involving themselves in youth movements in particular. They are both uncompromising champions of Indian independence; both intelligent and genuine patriots. And yet, their ideologies are as different as night and day. One is believed to be a devotee and proponent of India’s ancient culture and the other a committed follower of western civilization. If one is regarded as tender-hearted and sensitive, the other is spoken of as a quintessential revolutionary. Our attempt in this essay will be to present their respective ideologies before the public, so that people understand the difference between the two and make up their own minds.

But before we examine the ideas of these two leaders, it is important to mention another who is a champion of independence just as they are, and is also a prominent figure in certain youth movements. Sadhu Vaswani may not be as well known as the leading lights of the Congress, he may not occupy a special place in the country’s political arena, yet his influence is apparent among the youth, who will shape the country’s future. The organization Sadhu Vaswani founded — Bharat Yuva Sangh — has a particular hold on young Indians. Vaswani’s ideology can be summed up in a single phrase: back to the Vedas. This call was first given by the Arya Samaj. It is based on the belief that the Almighty has poured all the knowledge of the world into the Vedas. No progress is possible beyond them. Therefore, the world has not and cannot achieve anything greater than the wonders our very own India had achieved in the ancient past! So that is the entire faith of people like Vaswani. Which why he says:

“Up until now, our politics has either considered Mazzini and Voltaire as its ideals, or it has sought inspiration from Lenin and Tolstoy. This, when they should know that they have far greater ideals in our ancient rishis…”

Vaswani is convinced that once upon a time, our country had reached the final summit of development and today there is no reason for us to move forward at all; we only need to go back to the past.

Vaswani is a poet. Everything about his ideology is poetic. He is also a great practitioner of religious dharma. He wants to establish ‘Shakti-dharma’. He says, ‘At this time we need shakti — power — more than ever. He does not use the word ‘shakti’ only for India. He sees the word as the path and means to a kind of Devi, a special godhead. Like a very emotional poet he tells us:

‘For in solitude have I communicated with her, our admired Bharat Mata and my aching head has heard voices saying — “The day of freedom is not far off.” Sometimes indeed a strange feeling visits me and I say to myself: Holy, holy is Hindustan. For still is she under the protection of her mighty Rishis and their beauty is around us, but we behold it not.’

It must be the poet’s lament that makes him declare, over and over like a man deranged or distracted: ‘Our mother is the greatest. She is the mightiest. No one alive can vanquish her!’ In this fashion, driven purely by emotion, he ends up saying things like this: ‘Our national movement must become a purifying mass movement, if it is to fulfill its destiny without falling into class war one of the dangers of Bolshevism.’

He believes that all one needs to do is to say — ‘Go among the poor, go to the villages, give them free medicines’ — and our mission is accomplished. He’s a romantic poet. His poetry can offer no special purpose, it can only excite the heart a little. In fact, he has no vision to offer, except great noise about our ancient civilisation. He gives nothing to young minds. His only aim is to fill every heart with plain emotion. He has obvious influence among the youth, and it is growing. His ideas are regressive and patchy, as we’ve seen above. Such ideas have no direct connection with politics, and yet they have a significant effect. Mainly because it is the youth who are the future, and it is among them that such ideas are being propagated.

The leaders who have gained prominence this time are the venerable Subhash Chandra Bose of Bengal and the eminent Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. These are the two leaders who appear to be rising above all others in India and involving themselves in youth movements in particular. They are both uncompromising champions of Indian independence; both intelligent and genuine patriots. And yet, their ideologies are as different as night and day.

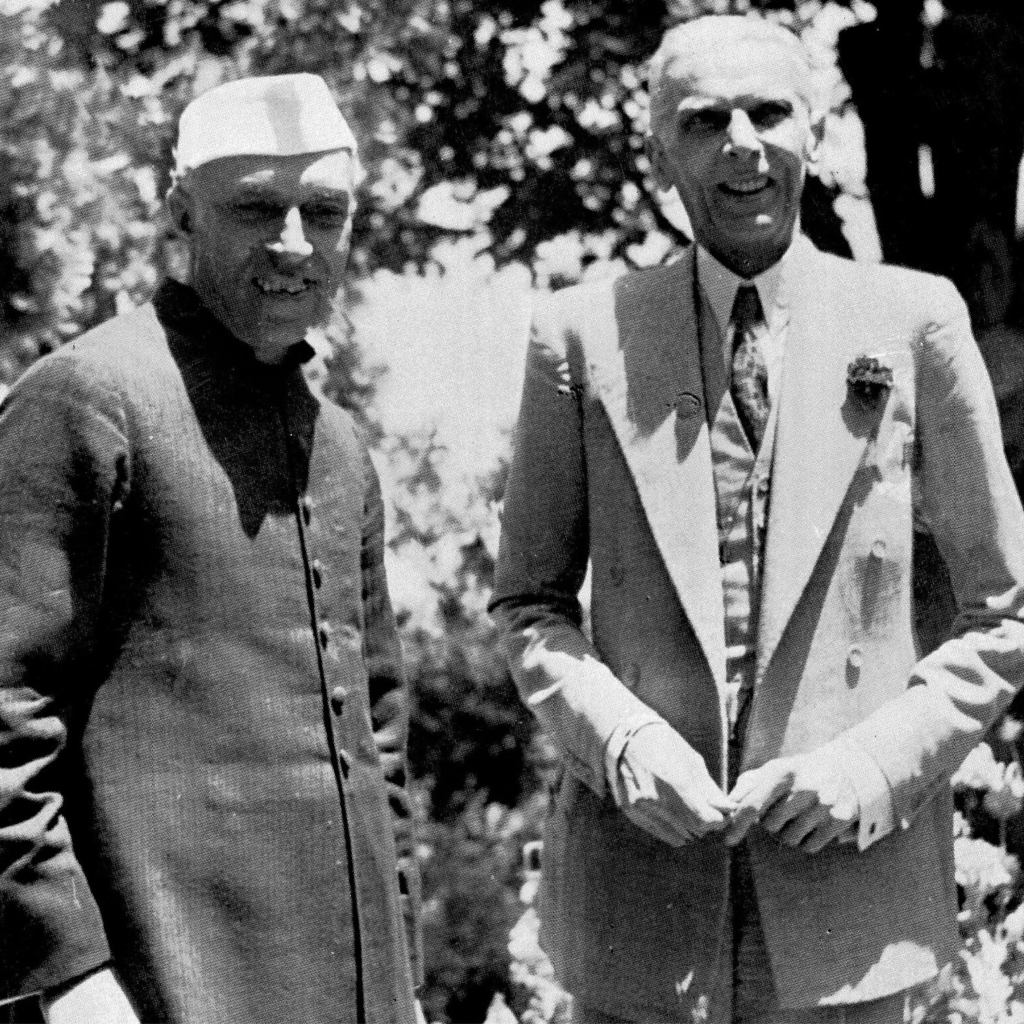

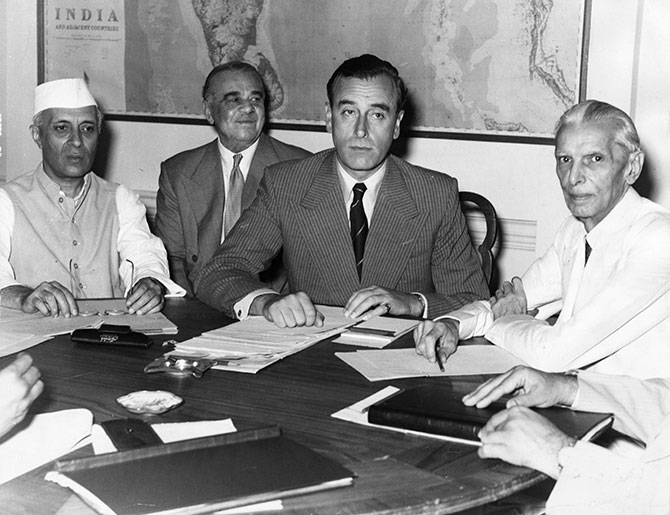

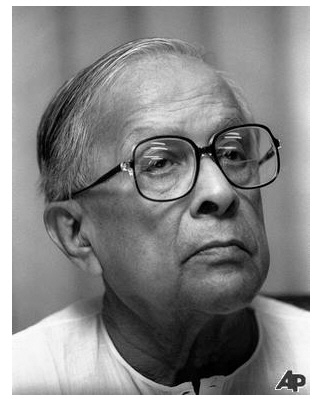

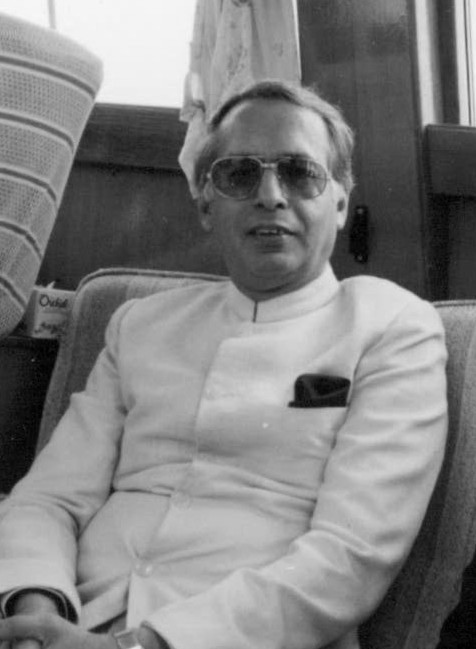

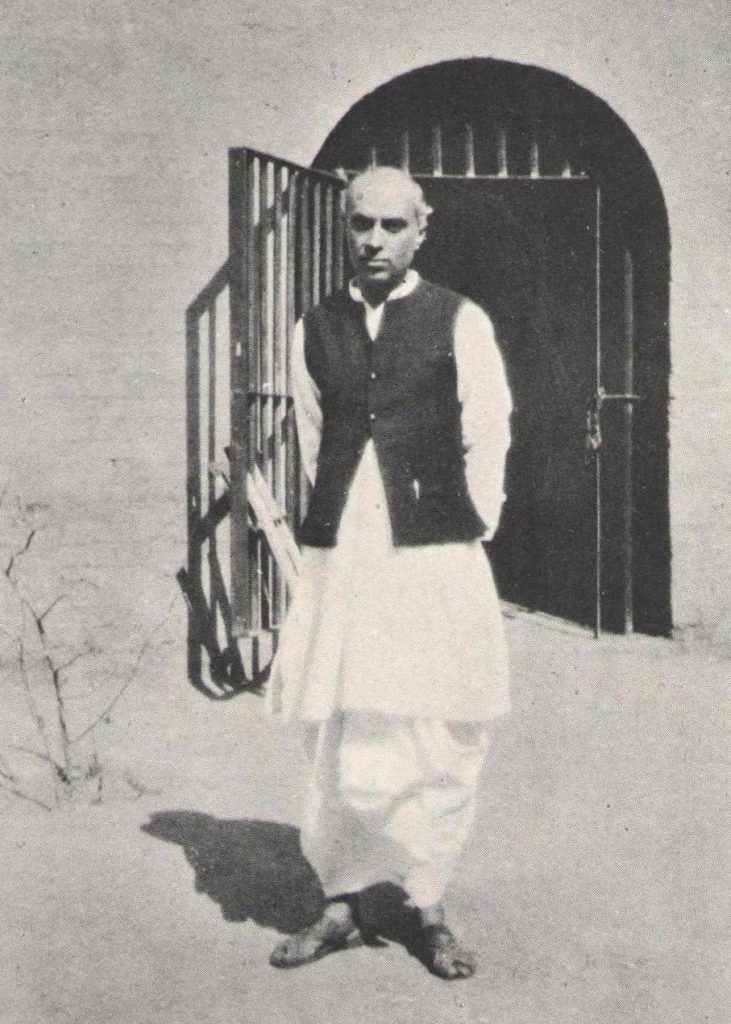

Jawaharlal Nehru with Subhas Chandra Bose

Let us now return to Subhash Chandra Bose and Jawaharlal Nehru. During the last three months, they have both chaired many conferences and put their thoughts and ideas before people. The government considers Subhash Babu a member of the group that is committed to overthrowing it, for which reason it had charged and imprisoned him under the Bengal Act. Upon his release, he was chosen as the leader of the Extremist group [of the Congress]. He espouses Purna Swaraj [complete independence], and argued for this in his presidential address at the Maharashtra session [of the Congress].

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru is the son of the Swaraj Party leader Motilal Nehru. He is a barrister, and a very learned man. He has travelled to Russia and other countries. He is also a leader of the Extremist group, and it was due to his efforts, and those of his fellow leaders, that the resolution for Purna Swaraj was passed and adopted at the Madras session. Before this, he had spoken emphatically in favour of Purna Swaraj at the Amritsar session.

And yet, the two leaders are poles apart in their thinking. Reading the transcripts of their speeches at the Amritsar and Maharashtra sessions, this difference was apparent to us. But the difference became clear as daylight after a speech delivered in Bombay. Pandit Nehru was chairing the conference and Subhash Bose made a speech. He is a very emotional Bengali. He began his address with the statement that India has a special message for the world. It has a lesson in spirituality for humanity. And then he launched into his speech like a man in the grip of disorienting emotion — ‘Behold the Taj Mahal on a moonlit night and think of the vision of that heart that imagined it. Recall that a Bengali novelist has written that “our flowing tears hardened into stone within us”. Bose also declares that we should return to the Vedas. In his Poona [Congress session] address, he had expounded on ‘nationalism’ and said that internationalists criticize nationalism as narrow, chauvinistic ideology, but that this is a mistake. Indian nationalist thought, according to him, is nothing of the kind. It is not chauvinistic. It is not born of self-interest, and it is not oppressive, because at its root is the philosophy of Satyam Shivam Sundaram — Truth is bountiful and beautiful.

The same old romanticism. Pure emotionalism. And [like Vaswani], Bose too has great faith in his ancient past. He sees only greatness in this ancient era. In his thinking, there’s nothing new in the system of panchayati raj, or the rule of the people, which he says is very old in India. He goes so far as to say that Communism isn’t new to India either. Anyway, that day in Bombay, he went on long and hard about India’s special message for the world.

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, like many others, holds an entirely different view: ‘Every country thinks it has a special message for the world. England has arrogated to itself the right to teach the world culture. I don’t see anything special that belongs to my country alone. But Subhash Babu has great belief in such things!’ Nehru also says, ‘Every youth must rebel. Not only in the political sphere, but in social, economic and religious spheres also. I have not much use for any man who comes and tells me that such and such thing is said in the Koran. Everything unreasonable must be discarded, even if they find authority for it in the Vedas and the Koran.’

One man thinks our old systems are very superior; the other man believes we should rebel against these systems. Yet the latter is called emotional, sensitive, and the former a transformative revolutionary!

These are the thoughts of a true revolutionary, while Subhash Chandra’s are the thoughts of someone who wants to replace one regime with another. One man thinks our old systems are very superior; the other man believes we should rebel against these systems. Yet the latter is called emotional, sensitive, and the former a transformative revolutionary! At one point Pandit Nehru says:

“To those who still fondly cherish old ideas and are starving to bring back the conditions which prevailed in Arabia 1300 years ago or in the vedic age in India, I say that it is inconceivable that you can bring back the hoary past. The world of reality will not retrace its steps, the world of imagination may remain stationary.”

This is why it feels necessary to revolt.

Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhash Chandra Bose

Subhash Babu supports Purna Swaraj, complete independence, because the British are people of the West and we are of the East. Pandit Ji’s position is that we need to establish our own rule so that we can change the entire social structure. This is why we must have complete and absolute independence.

Subhash Babu is in sympathy with labour, the working class, and wants to improve their condition. Pandit ji wants to bring in revolution and change the existing system altogether. Subhash Chandra is emotional and romantic — he is giving the young food for their hearts, and only their hearts. The other man is an epochal change — maker who is fuelling not just the heart but also the mind:

“They should aim at Swaraj for the masses based on Socialism. That was a revolutionary change which they could not bring about without revolutionary methods… Mere reform or gradual repairing of the existing machinery could not achieve the real, proper Swaraj for the general masses.”

Subhash Babu feels the need to focus on national politics only as long as it is necessary to safeguard and promote India’s position in world politics. But Pandit ji has freed himself of the narrow confines of plain nationalism and emerged into an open field.

Subhash Babu feels the need to focus on national politics only as long as it is necessary to safeguard and promote India’s position in world politics. But Pandit ji has freed himself of the narrow confines of plain nationalism and emerged into an open field.

Now the ideas of the [two] leaders are before us. Which way should we incline? One Punjabi newspaper has heaped praise upon Subhash Chandra and said of Pandit ji and others that such rebels destroy themselves beating their heads against stone. We must of course remember that Punjab has always been a rather emotional province. People’s passions here rise very quickly and just as quickly subside, like foam.

Subhash Chandra doesn’t appear to be providing any intellectual nourishment, only food for the heart. The need of the hour now is for the youth of Punjab to understand and strengthen revolutionary ideas. At this time, Punjab needs food for the mind, does not mean we should become his blind followers. But as far as ideas are concerned, the young people of Punjab should align themselves with him, so that they can know the true meaning of revolution, realize the need for a revolution in India, understand the significance of revolution in the world at large, and so on Through serious thought and analysis, the youth should bring clarity and conviction to their ideas, so that even in times of very little hope, times of disillusionment and defeat, they should not lose direction, stand tall and strong against a hostile world and not give up. This is how the public will achieve the goal of revolution.

— Bhagat Singh

This is a translation of Bhagat Singh’s ‘Naye Netaaon ke Alag Alag Vichar’ in the July 1928 issue of the journal Kirti. This translated version has been carried courtesy the permission of Purushottam Agrawal.

You can buy Who is Bharat Mata? On History, Culture and the Idea of India: Writings by and On Jawaharlal Nehru here.

ARCHIVE

At Benares Hindu University (Benares, February, 1916)

MOHANDAS KARAMCHAND GANDHI

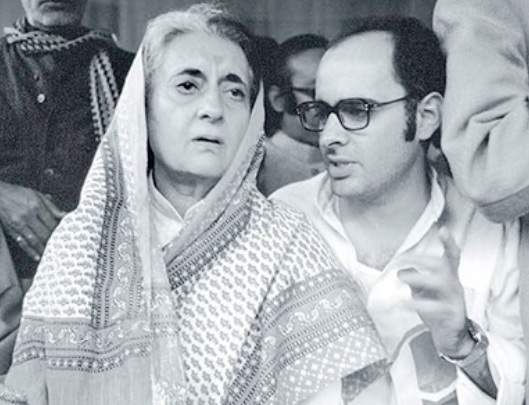

Mahatma Gandhi

I wish to tender my humble apology for the long delay that took place before I was able to reach this place. And you will readily accept the apology when I tell you that I am not responsible for the delay nor is any human agency responsible for it. The fact is that I am like an animal on show, and my keepers in their over kindness always manage to neglect a necessary chapter in this life, and, that is, pure accident. In this case, they did not provide for the series of accidents that happened to us—to me, keepers, and my carriers. Hence this delay.

Friends, under the influence of the matchless eloquence of Mrs Besant who has just sat down, pray, do not believe that our University has become a finished product, and that all the young men who are to come to the University, that has yet to rise and come into existence, have also come and returned from it finished citizens of a great empire. Do not go away with any such impression, and if you, the student world to which my remarks are supposed to be addressed this evening, consider for one moment that the spiritual life, for which this country is noted and for which this country has no rival, can be transmitted through the lip, pray, believe me, you are wrong. You will never be able merely through the lip, to give the message that India, I hope, will one day deliver to the world. I myself have been fed up with speeches and lectures. I accept the lectures that have been delivered here during the last two days from this category, because they are necessary. But I do venture to suggest to you that we have now reached almost the end of our resources in speech-making; it is not enough that our ears are feasted, that our eyes are feasted, but it is necessary that our hearts have got to be touched and that our hands and feet have got to be moved.

We have been told during the last two days how necessary it is, if we are to retain our hold upon the simplicity of Indian character, that our hands and feet should move in unison with our hearts. But this is only by way of preface. I wanted to say it is a matter of deep humiliation and shame for us that I am compelled this evening under the shadow of this great college, in this sacred city, to address my countrymen in a language that is foreign to me. I know that if I was appointed an examiner, to examine all those who have been attending during these two days this series of lectures, most of those who might be examined upon these lectures would fail. And why? Because they have not been touched.

I wanted to say it is a matter of deep humiliation and shame for us that I am compelled this evening under the shadow of this great college, in this sacred city, to address my countrymen in a language that is foreign to me. I know that if I was appointed an examiner, to examine all those who have been attending during these two days this series of lectures, most of those who might be examined upon these lectures would fail. And why? Because they have not been touched.

I was present at the sessions of the great Congress in the month of December. There was a much vaster audience, and will you believe me when I tell you that the only speeches that touched the huge audience in Bombay were the speeches that were delivered in Hindustani? In Bombay, mind you, not in Benaras where everybody speaks Hindi. But between the vernaculars of the Bombay Presidency on the one hand and Hindi on the other, no such great dividing line exists as there does between English and the sister language of India; and the Congress audience was better able to follow the speakers in Hindi. I am hoping that this University will see to it that the youths who come to it will receive their instruction through the medium of their vernaculars. Our languages are the reflection of ourselves, and if you tell me that our languages are too poor to express the best thought, then say that the sooner we are wiped out of existence the better for us. Is there a man who dreams that English can ever become the national language of India? Why this handicap on the nation? Just consider for one moment what an equal race our lads have to run with every English lad.

I had the privilege of a close conversation with some Poona professors. They assured me that every Indian youth, because he reached his knowledge through the English language, lost at least six precious years of life. Multiply that by the numbers of students turned out by our schools and colleges, and find out for yourselves how many thousand years have been lost to the nation. The charge against us is that we have no initiative. How can we have any, if we are to devote the precious years of our life to the mastery of a foreign tongue? We fail in this attempt also. Was it possible for any speaker yesterday and today to impress his audience as was possible for Mr Higginbotham? It was not the fault of the previous speakers that they could not engage the audience. They had more than substance enough for us in their addresses. But their addresses could not go home to us. I have heard it said that after all it is English educated India which is leading and which is doing all the things for the nation. It would be monstrous if it were otherwise. The only education we receive is English education. Surely we must show something for it. But suppose that we had been receiving during the past fifty years’ education through our vernaculars, what should we have today? We should have today a free India, we should have our educated men, not as if they were foreigners in their own land but speaking to the heart of the nation; they would be working amongst the poorest of the poor, and whatever they would have gained during these fifty years would be a heritage for the nation. Today even our wives are not the sharers in our best thought. Look at Professor Bose and Professor Ray and their brilliant researches. Is it not a shame that their researches are not the common property of the masses?

I have heard it said that after all it is English educated India which is leading and which is doing all the things for the nation. It would be monstrous if it were otherwise. The only education we receive is English education. Surely we must show something for it. But suppose that we had been receiving during the past fifty years’ education through our vernaculars, what should we have today? We should have today a free India, we should have our educated men, not as if they were foreigners in their own land but speaking to the heart of the nation; they would be working amongst the poorest of the poor, and whatever they would have gained during these fifty years would be a heritage for the nation.

Let us now turn to another subject.

The Congress has passed a resolution about self-government, and I have no doubt that the All-India Congress Committee and the Muslim League will do their duty and come forward with some tangible suggestions. But I, for one, must frankly confess that I am not so much interested in what they will be able to produce as I am interested in anything that the student world is going to produce or the masses are going to produce. No paper contribution will ever give us self-government. No amount of speeches will ever make us fit for self-government. It is only our conduct that will make us fit for it. And how are we trying to govern ourselves?

I want to think audibly this evening. I do not want to make a speech and if you find me this evening speaking without reserve, pray, consider that you are only sharing the thoughts of a man who allows himself to think audibly, and if you think that I seem to transgress the limits that courtesy imposes upon me, pardon me for the liberty I may be taking. I visited the Vishwanath temple last evening, and as I was walking through those lanes, these were the thoughts that touched me. If a stranger dropped from above on to this great temple, and he had to consider what we as Hindus were, would he not be justified in condemning us? Is not this great temple a reflection of our own character? I speak feelingly, as a Hindu. Is it right that the lanes of our sacred temple should be as dirty as they are? The houses round about are built anyhow. The lanes are tortuous and narrow. If even our temples are not models of roominess and cleanliness, what can our self-government be? Shall our temples be abodes of holiness, cleanliness and peace as soon as the English have retired from India, either of their own pleasure or by compulsion, bag and baggage?

I entirely agree with the President of the Congress that before we think of self-government, we shall have to do the necessary plodding. In every city there are two divisions, the cantonment and the city proper. The city mostly is a stinking den. But we are a people unused to city life. But if we want city life, we cannot reproduce the easy-going hamlet life. It is not comforting to think that people walk about the streets of Indian Bombay under the perpetual fear of dwellers in the storeyed building spitting upon them. I do a great deal of railway travelling. I observe the difficulty of third-class passengers. But the railway administration is by no means to blame for all their hard lot.

We do not know the elementary laws of cleanliness. We spit anywhere on the carriage floor, irrespective of the thoughts that it is often used as sleeping space. We do not trouble ourselves as to how we use it; the result is indescribable filth in the compartment. The so-called better class passengers overawe their less fortunate brethren. Among them I have seen the student world also; sometimes they behave no better. They can speak English and they have worn Norfolk jackets and, therefore, claim the right to force their way in and command seating accommodation.

We do not know the elementary laws of cleanliness. We spit anywhere on the carriage floor, irrespective of the thoughts that it is often used as sleeping space. We do not trouble ourselves as to how we use it; the result is indescribable filth in the compartment. The so-called better class passengers overawe their less fortunate brethren.

I have turned the searchlight all over, and as you have given me the privilege of speaking to you, I am laying my heart bare. Surely we must set these things right in our progress towards self-government. I now introduce you to another scene. His Highness the Maharaja who presided yesterday over our deliberations spoke about the poverty of India. Other speakers laid great stress upon it. But what did we witness in the great pandal in which the foundation ceremony was performed by the Viceroy? Certainly a most gorgeous show, an exhibition of jewellery, which made a splendid feast for the eyes of the greatest jeweler who chose to come from Paris. I compare with the richly bedecked noble men the millions of the poor. And I feel like saying to these noble men, ‘There is no salvation for India unless you strip yourselves of this jewellery and hold it in trust for your countrymen in India.’ I am sure it is not the desire of the King-Emperor or Lord Hardinge that in order to show the truest loyalty to our King-Emperor, it is necessary for us to ransack our jewellery boxes and to appear bedecked from top to toe. I would undertake, at the peril of my life, to bring to you a message from King George himself that he accepts nothing of the kind.

Sir, whenever I hear of a great palace rising in any great city of India, be it in British India or be it in India which is ruled by our great chiefs, I become jealous at once, and say, ‘Oh, it is the money that has come from the agriculturists.’ Over seventy-five percent of the population are agriculturists and Mr Higginbotham told us last night in his own felicitous language, that they are the men who grow two blades of grass in the place of one. But there cannot be much spirit of self-government about us, if we take away or allow others to take away from them almost the whole of the results of their labour. Our salvation can only come through the farmer. Neither the lawyers, nor the doctors, nor the rich landlords are going to secure it.

Now, last but not the least, it is my bounden duty to refer to what agitated our minds during these two or three days. All of us have had many anxious moments while the Viceroy was going through the streets of Benares. There were detectives stationed in many places. We were horrified. We asked ourselves, ‘Why this distrust?’ Is it not better that even Lord Hardinge should die than live a living death? But a representative of a mighty sovereign may not. He might find it necessary to impose these detectives on us? We may foam, we may fret, we may resent, but let us not forget that India of today in her impatience has produced an army of anarchists. I myself am an anarchist, but of another type. But there is a class of anarchists amongst us, and if I was able to reach this class, I would say to them that their anarchism has no room in India, if India is to conquer the conqueror. It is a sign of fear. If we trust and fear God, we shall have to fear no one, not the maharajas, not the viceroys, not the detectives, not even King George.

I myself am an anarchist, but of another type. But there is a class of anarchists amongst us, and if I was able to reach this class, I would say to them that their anarchism has no room in India, if India is to conquer the conqueror. It is a sign of fear. If we trust and fear God, we shall have to fear no one, not the maharajas, not the viceroys, not the detectives, not even King George.

I honour the anarchist for his love of the country. I honour him for his bravery in being willing to die for his country; but I ask him— is killing honourable? Is the dagger of an assassin a fit precursor of an honourable death? I deny it. There is no warrant for such methods in any scriptures. If I found it necessary for the salvation of India that the English should retire, that they should be driven out, I would not hesitate to declare that they would have to go, and I hope I would be prepared to die in defense of that belief. That would, in my opinion, be an honourable death. The bombthrower creates secret plots, is afraid to come out into the open, and when caught pays the penalty of misdirected zeal.

I have been told, ‘Had we not done this, had some people not thrown bombs, we should never have gained what we have got with reference to the partition movement.’ (Mrs Besant: ‘Please stop it.’) This was what I said in Bengal when Mr Lyon presided at the meeting. I think what I am saying is necessary. If I am told to stop I shall obey. (Turning to the Chairman) I await your orders. If you consider that by my speaking as I am, I am not serving the country and the empire I shall certainly stop. (Cries of ‘Go on.’) (The Chairman: ‘Please, explain your object.’) I am simply… (another interruption). My friends, please do not resent this interruption. If Mrs Besant this evening suggests that I should stop, she does so because she loves India so well, and she considers that I am erring in thinking audibly before you young men. But even so, I simply say this, that I want to purge India of this atmosphere of suspicion on either side, if we are to reach our goal; we should have an empire which is to be based upon mutual love and mutual trust. Is it not better that we talk under the shadow of this college than that we should be talking irresponsibly in our homes? I consider that it is much better that we talk these things openly. I have done so with excellent results before now. I know that there is nothing that the students do not know. I am, therefore, turning the searchlight towards ourselves. I hold the name of my country so dear to me that I exchange these thoughts with you, and submit to you that there is no room for anarchism in India. Let us frankly and openly say whatever we want to say our rulers, and face the consequences if what we have to say does not please them. But let us not abuse.

I was talking the other day to a member of the much-abused Civil Service. I have not very much in common with the members of that Service, but I could not help admiring the manner in which he was speaking to me. He said: ‘Mr Gandhi, do you for one moment suppose that all we, Civil Servants, are a bad lot, that we want to oppress the people whom we have come to govern?’ ‘No,’ I said. ‘Then if you get an opportunity put in a word for the much-abused Civil Service.’ And I am here to put in that word. Yes, many members of the Indian Civil Service are most decidedly overbearing; they are tyrannical, at times thoughtless. Many other adjectives may be used. I grant all these things and I grant also that after having lived in India for a certain number of years some of them become somewhat degraded. But what does that signify? They were gentlemen before they came here, and if they have lost some of the moral fibre, it is a reflection upon ourselves.

Just think out for yourselves, if a man who was good yesterday has become bad after having come in contact with me, is he responsible that he has deteriorated or am I? The atmosphere of sycophancy and falsity that surrounds them on their coming to India demoralizes them, as it would many of us. It is well to take the blame sometimes. If we are to receive self-government, we shall have to take it. We shall never be granted self-government. Look at the history of the British Empire and the British nation; freedom loving as it is, it will not be a party to give freedom to a people who will not take it themselves. Learn your lesson if you wish to from the Boer War. Those who were enemies of that empire only a few years ago have now become friends…

If we are to receive self-government, we shall have to take it. We shall never be granted self-government. Look at the history of the British Empire and the British nation; freedom loving as it is, it will not be a party to give freedom to a people who will not take it themselves. Learn your lesson if you wish to from the Boer War. Those who were enemies of that empire only a few years ago have now become friends…

(At this point there was an interruption and a movement on the platform to leave. The speech, therefore, ended here abruptly).

Election Speech (December, 1926)

KAMALADEVI CHATTOPADHYAY

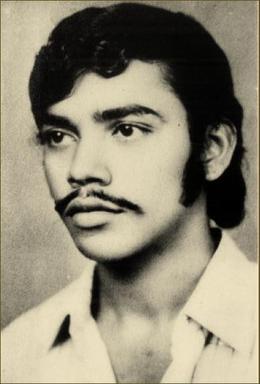

Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay

If you peep into the dim unknown history of India, the history of which is written not on palm leaves or papers, but is alive in the hearts of everyone of us, you will find that the position of women was indeed an enviable one. Never in the history of any country, at any time, has woman been so honoured as she has been in this country. Though apparently she seems to have lost her voice, she has always been the vital element in the evolution of the country and the nation. When I was travelling abroad, I was often asked how the suffragist movement in India was progressing. I could only tell them that there was no suffragist movement in India. In fact, there was no need for such a movement. The last few years have proved this. As soon as the new reforms came in the franchise was granted, and closely following upon its heels came the removal of the ban on sex-disqualification. The time has now come when women should come forward and share the responsibilities equally with men. All over the world women are now taking a keen and an active part in all departments of life.

The time has now come when women should come forward and share the responsibilities equally with men. All over the world women are now taking a keen and an active part in all departments of life.

I stand now as an Independent. I stand for no party or community. I stand as a representative of women. I am not a Swarajist candidate and I am not a member of the Swarajya Party. I do not believe in the policy of obstruction and walk-out. What the Swarajya programme for this year is, I do not know. Whether it is going to accept office or not, does not concern me. That temptation does not come in my way.

People have been questioning me what my political precedents are. I have been interested in politics for several years now. When the great Non-Co-operation Movement was started, my husband and I were pursuing studies in England. The great message came to us over the waters. Our hearts throbbed to the cries of the great nation. Gandhi’s message of love thrilled us, and we felt that we should not be led away by the glamor of foreign degrees. A golden opportunity had been offered to us to do our bit for our country. By the time we had completed our tour and landed in India, Mahatamaji had been imprisoned for some time. When we landed in India we were met by Mrs. [Sarojini] Naidu. The first question we asked her was: What was the condition of the country? She said there was no condition at all. Death had already set in. Our burning spirits were as defeated with this reply. We enlisted ourselves as Congress members and and tried to do our bit, but a good many difficulties arose in our way.

We soon found much of our precious time getting scattered. We then decided to do the same work through the arts and achieve the same end. So at the Belgaum Congress, we consulted Mahatmaji. He gladly assented to our plans and with his blessings we started upon our work. We have been trying to wake up the political consciousness of the country through poetry, through music and through drama. It was just a month ago that we met Mahatma Gandhi in Bombay and he said: “Though I am pressed with heavy work, I have found time to watch with pleasure your progress. Though I cannot be with you in person, let me admire you from a distance. When you have a little leisure come to my Ashram and show my boys the beauties of your art.” Even on the day I was leaving for Mangalore we received two wires asking us to go to him. It was indeed a great temptation I had to resist. All these three years, though I have not been active in the political field, all the time I have been in close touch with politics.

If women in other countries have proved competent enough to handle these problems I do not think an Indian woman will prove an exception. For years you have been sending men to the councils. Some of them have done something for this district. Others have done nothing. So even if a woman fails to fulfill your expectations you have not much to regret.

As to what work I shall do in the council, though no doubt I shall try to tackle problems that are intimately connected with women and children, I feel confident that with time and study I shall be in a position to handle general questions as well. During the course of my tour I have been observing and studying the local grievances. I have been trying to get first-hand information as to the Forest and Land Act. Some of the main problems agitating the public mind just now are the abolition of the old Rent Recovery Act without the introduction of any new compensating one and the Revenue Settlement Act. I have enough of leisure at my disposal to devote it to this work. I appeal to you to give me a chance. If women in other countries have proved competent enough to handle these problems I do not think an Indian woman will prove an exception. For years you have been sending men to the councils. Some of them have done something for this district. Others have done nothing. So even if a woman fails to fulfill your expectations you have not much to regret. Some of you may have some conscientious objections in supporting my candidature either on the ground of sex or otherwise. I appeal to them in that case, at least, to remain neutral as far as possible.

For, remember, when you work against me, you insult all womankind, you work against your own mothers, your sisters, your daughters.

When you lend me your support, it is not merely a personal favour you do to me, but you pay your homage to womankind. If the first Indian woman who has come forward in spite of all difficulties and obstacles is not helped, it will greatly discourage the women who in the future might stand for elections. So the privilege granted to women will be hardly of any service.

When you lend me your support, it is not merely a personal favour you do to me, but you pay your homage to womankind. If the first Indian woman who has come forward in spite of all difficulties and obstacles is not helped, it will greatly discourage the women who in the future might stand for elections. So the privilege granted to women will be hardly of any service. I am not concerned very much with the result. I shall do my best. I wish to prove to the world that a woman can fight and fight well in spite of everything. Woman in India has always stood for strength and not weakness. She is the Divine Shakti. Whether it is a mere sentiment or a living flame, will be proved by the elections.

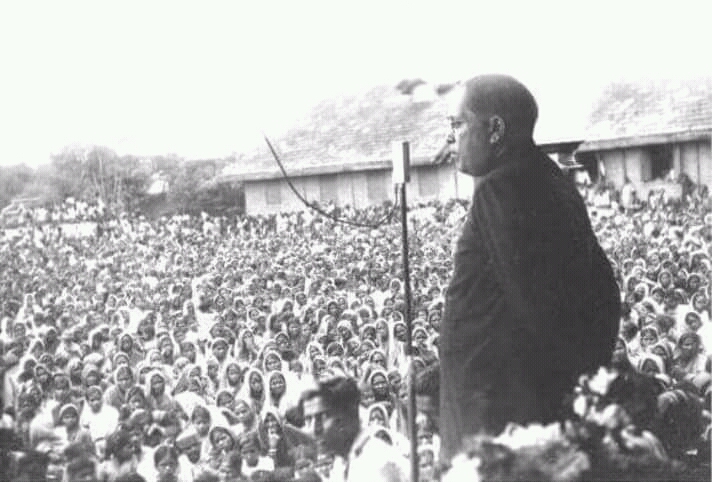

Speech at Mahad (Mahad, December 1927)

BHIMRAO RAMJI AMBEDKAR

B.R. Ambedkar

Gentlemen, you have gathered here today in response to the invitation of the Satyagraha Committee. As the Chairman of that Committee, I gratefully welcome you all.

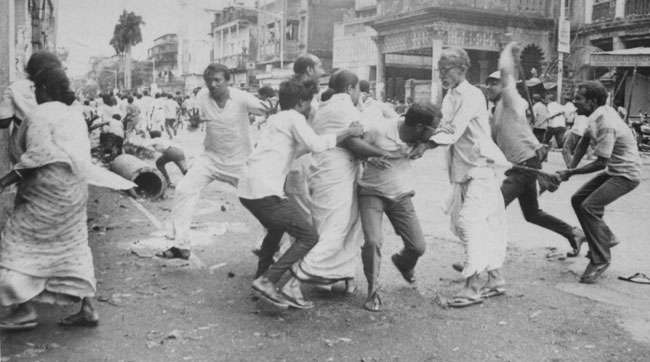

Many of you will remember that on the 19th of last March all of us came to the Chavadar Lake here. The caste Hindus of Mahad had laid no prohibition on us; but they showed they had objections to our going there by the attack they made. The fight brought results that one might have expected. The aggressive caste Hindus were sentenced to four months’ rigorous imprisonment, and are now in jail. If we had not been hindered on 19th March, it would have been proved that the caste Hindus acknowledge our right to draw water from the lake, and we should have had no need to begin our present undertaking.

Unfortunately we were thus hindered, and we have been obliged to call this meeting today. This lake at Mahad is public property. The caste Hindus of Mahad are so reasonable that they not only draw water from the lake themselves but freely permit people of any religion to draw water from it, and accordingly people of other religions such as the Islamic do make use of this permission. Nor do the caste Hindus prevent members of species considered lower than the human, such as birds and beasts, from drinking at the lake. Moreover, they freely permit beasts kept by untouchables to drink at the lake.

Caste Hindus are the very founts of compassion. They practise no hinsa and harass no one. They are not of the class of miserly and selfish folk who would grudge even a crow some grains of the food they are eating. The proliferation of sanyasis and mendicants is a living testimony to their charitable temperament. They regard altruism as religious merit and injury to another as a sin.

Even further, they have imbibed the principle that injury done by another must not be repaid but patiently endured, and so, they not only treat the harmless cow with kindness, but spare harmful creatures such as snakes. That one Atman or Spiritual Self dwells in all creatures has become a settled principle of their conduct. Such are the caste Hindus who forbid some human beings of their own religion to draw water from the Same Chavadar Lake! One cannot help asking the question, why do they forbid us alone?

Such are the caste Hindus who forbid some human beings of their own religion to draw water from the Same Chavadar Lake! One cannot help asking the question, why do they forbid us alone?

It is essential that all should understand thoroughly the answer to this question. Unless you do, I feel, you will not grasp completely the importance of today’s meeting. The Hindus are divided, according to sacred tradition, into four castes; but according to custom, into five: Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, Shudras and Atishudras. The caste system is the first of the governing rules of the Hindu religion. The second is that the castes are of unequal rank. They are ordered in a descending series of each meaner than the one before.

Not only are their ranks permanently fixed by the rule, but each is assigned boundaries it must not transgress, so that each one may at once be recognized as belonging to its particular rank. There is a general belief that the prohibitions in the Hindu religion against intermarriage, interdining, inter drinking and social intercourse are bounds set to degrees of association with one another. But this is an incomplete idea. These prohibitions are indeed limits to degrees of association; but they have been set to show people of unequal rank what the rank of each is. That is, these bounds are symbols of inequality.

Just as the crown on a man’s head shows he is a king, and the bow in his hand shows him to be a Kshatriya, the class to which none of the prohibitions applies is considered the highest of all and the one to which they all apply is reckoned the lowest in rank. The strenuous efforts made to maintain the prohibitions are for the reason that, if they are relaxed, the inequality settled by religion will break down and equality will take its place.

The caste Hindus of Mahad prevent the untouchables from drinking the water of the Chavadar Lake not because they suppose that the touch of the untouchables will pollute the water or that it will evaporate and vanish. Their reason for preventing the untouchables from drinking it is that they do not wish to acknowledge by such a permission that castes declared inferior by sacred tradition are in fact their equals.

Gentlemen! you will understand from this the significance of the struggle we have begun. Do not let yourselves suppose that the Satyagraha Committee has invited you to Mahad merely to drink the water of the Chavadar Lake of Mahad.

It is not as if drinking the water of the Chavadar Lake will make us immortal. We have survived well enough all these days without drinking it. We are not going to the Chavadar Lake merely to drink its water. We are going to the Lake to assert that we too are human beings like others. It must be clear that this meeting has been called to set up the norm of equality.

It is not as if drinking the water of the Chavadar Lake will make us immortal. We have survived well enough all these days without drinking it. We are not going to the Chavadar Lake merely to drink its water. We are going to the Lake to assert that we too are human beings like others. It must be clear that this meeting has been called to set up the norm of equality.

I am certain that no one who thinks of this meeting in this light will doubt that it is unprecedented. I feel that no parallel to it can be found in the history of India. If we seek for another meeting in the past to equal this, we shall have to go to the history of France on the continent of Europe. A hundred and thirty-eight years ago, on 24 January 1789, King Louis XVI had convened, by royal command, an assembly of deputies to represent the people of the kingdom. His French National Assembly has been much vilified by historians. The Assembly sent the King and the Queen of France to the guillotine; persecuted and massacred the aristocrats; and drove their survivors into exile. It confiscated the estates of the rich and plunged Europe into war for fifteen years. Such are the accusations leveled against the Assembly by the historians. In my view, the criticism is misplaced; further, the historians of this school have not understood the gist of the achievement of the French National Assembly. That achievement served the welfare not only of France but of the entire European continent. If European nations enjoy peace and prosperity today, it is for one reason: the revolutionary French National Assembly convened in 1789 set new principles for the organization of society before the disorganized and decadent French nation of its time, and the same principles have been accepted and followed by Europe.

To appreciate the importance of the French National Assembly and the greatness of its principles, we must keep in mind the suite of French society at the time. You are all aware that our Hindu society is based on the system of castes. A rather similar system of classes existed in the France of 1789: the difference was that it was a society of three castes. Like the Hindu society, the French had a class of Brahmins and another of Kshatriyas. But instead of three different castes of Vaishya, Shudra, and Atishudra, there was one class that comprehended these. This is a minor difference. The important thing is that the caste or class system was similar. The similarity to be noted is not only in the differentiation between classes: the inequality of our caste system was also to be found in the French social system. The nature of the inequality in the French society was different: it was economic in nature. It was, however, equally intense. The thing to bear in mind is there is a great similarity between the French National Assembly that met on 5 May 1789 at Versailles and our meeting today. The similarity is not only in the circumstances in which the two meetings took place but also in their ideals.

That Assembly of the French people was convened to reorganize French society. Our meeting today too has been convened to reorganize Hindu society. Hence, before discussing on what principles our society should be reorganized, we should all pay heed to the principles on which the French Assembly relied and the policy it adopted. The scope of the French Assembly was far wider than that of our present meeting. It had to carry out the threefold organization of the French political, social and religious systems. We must confine ourselves to how social and religious reorganization can be brought about. Since we are not, for the present, concerned with political reorganization, let us see what the French Assembly did in the matter of the religious and social reorganization of their nation. The policy adopted by the French National Assembly in this area can be seen plainly by anyone from three important proclamations issued by that Assembly. The first was issued on 17 June 1789. This was a proclamation about the class systems in France. As said before, French society was divided into three classes. The proclamation abolished the three classes and blended them into one. Further, it abolished the seats reserved separately for the three classes (or estates) in the political assembly. The second proclamation was about the priests. By ancient custom, to appoint or remove these priests was outside the power of the nation, that being the monopoly of a foreign religious potentate, the Pope. Anyone appointed by the Pope was a priest, whether or not he was fit to be one in the eyes of those to whom he was to preach. The proclamation abolished the autonomy of the religious orders and assigned to the French nation the authority to decide who might follow this vocation, who was fit for it and who was not, whether he was to be paid for preaching or not, and so on. The third proclamation was not about the political, economic or religious systems. It was of a general nature and laid down the principles on which all social arrangements ought to rest. From that point of view, the third proclamation is the most important of the three; it might be called the king of these proclamations. It is renowned the world over as the declaration of human birthrights. It is not only unprecedented in the history of France; more than that, it is unique in the history of civilized nations. For every European nation has followed the French Assembly in giving it a place in its own constitution. So one may say that it brought about a revolution not only in France but the whole world. This proclamation has seventeen clauses, of which the following are important:

Any person is free to act according to his birthright. Any limit placed upon this freedom must be only to the extent necessary to permit other persons to enjoy their birthrights. Such limits must be laid down by law: they cannot be set on the grounds of the religion or on any other basis than the law of the land.

1) All human beings are equal by birth; and they shall remain equal till death. They may be distinguished in status only in the public interest. Otherwise, their equal status must be maintained.

2) The ultimate object of politics is to maintain these human birthrights.

3) The entire nation is the mother-source of sovereignty. The rights of any individual, group or special class, unless they are given by the nation, cannot be acknowledged as valid on any other ground, be it political or religious.

4) Any person is free to act according to his birthright. Any limit placed upon this freedom must be only to the extent necessary to permit other persons to enjoy their birthrights. Such limits must be laid down by law: they cannot be set on the grounds of the religion or on any other basis than the law of the land.

5) The law will forbid only such actions as are injurious to society. All must be free to do what has not been forbidden by law. Nor can anyone be compelled to do what the law has not laid down as a duty.

6) The law is not in the nature of bounds set by any particular class. The right to decide what the law shall be rests with the people or their representatives. Whether such a law is protective or punitive, it must be the same for all. Since justice requires that all social arrangements be based on the equality of all, all individuals are equally eligible for any kind of honour, power and profession. Any distinction in such matters must be owing to differences of individual merit; it must not be based on birth.

I feel our meeting today should keep the image of this French National Assembly before the mind. The road it marked out for the development of the French nation, the road that all progressed nations have followed, ought to be the road adopted for the development of Hindu society by this meeting. We need to pull away the nails which hold the framework of caste-bound Hindu society together, such as those of the prohibition of intermarriage down to the prohibition of social intercourse so that Hindu society becomes all of one caste. Otherwise untouchability cannot be removed nor can equality be established.

To raise men, aspiration is needed as much as outward efforts. Indeed it is to be doubted whether efforts are possible without aspiration. Hence, if a great effort is to be made, a great aspiration must be nursed. In adopting an aspiration one need not be abashed or deterred by doubts about one’s power to satisfy it. One should be ashamed only of mean aspirations; not of failure that may result because one’s aspiration is high. If untouchability alone is removed, we may change from Atishudras to Shurdas; but can we say that this radically removes untouchability? If such puny reforms as the removal of restrictions on social intercourse etc. were enough for the eradication of untouchability I would not have suggested that the caste system itself must go.

Some of you may feel that since we are untouchables, it is enough if we are set free from the prohibitions of interdrinking and social intercourse. That we need not concern ourselves with the caste system; how does it matter if it remains? In my opinion, this is a total error. If we leave the caste system alone and adopt only the removal of untouchability as our policy, people will say that we have chosen a low aim. To raise men, aspiration is needed as much as outward efforts. Indeed it is to be doubted whether efforts are possible without aspiration. Hence, if a great effort is to be made, a great aspiration must be nursed. In adopting an aspiration one need not be abashed or deterred by doubts about one’s power to satisfy it. One should be ashamed only of mean aspirations; not of failure that may result because one’s aspiration is high. If untouchability alone is removed, we may change from Atishudras to Shurdas; but can we say that this radically removes untouchability? If such puny reforms as the removal of restrictions on social intercourse etc. were enough for the eradication of untouchability I would not have suggested that the caste system itself must go. Gentlemen! You all know that if a snake is to be killed it is not enough to strike at its tail – its head must be crushed. If any harm is to be removed, one must seek out its root and strike at it. An attack must be based on the knowledge of the enemy’s vital weakness. Duryodhana was killed because Bheema struck at his thigh with his mace. If the mace had hit Durydhana’s head he would not have died; for his thigh was his vulnerable spot. One finds many instances of a physician’s efforts to remove a malady proving fruitless because he has not perceived fully what will get rid of the disease; similar instances of failure to root out a social disease when it is not fully diagnosed are rarely recorded in history; and so one does not often become aware of them. But let me acquaint you with one such instance that I have come across in my reading. In the ancient European nation of Rome, the patricians were considered upper class, and the plebians, lower class. All power was in the hands of, the patricians, and they used it to ill-treat the plebians. To free themselves from this harassment, the plebians, on the strength of their unity, insisted that laws should be written down for the facilitation of justice and for the information of all. Their patrician opponents agreed to this; and a charter of twelve laws was written down. But this did not rid the oppressed plebians of their woes. For the officers who enforced the laws were all of the patrician class; moreover, the chief officer, called the tribune, was also a patrician. Hence, though the laws were uniform, there was partiality in their enforcement. The plebians then demanded that instead of the administration being in the hands of one tribune there should be two tribunes, of whom one should be elected by the plebians and the other by the patricians. The patricians yielded to this too, and the plebians rejoiced, supposing they would now be free of their miseries. But their rejoicing was short-lived. The Roman people had a tradition that nothing was to be done without the favourable verdict of the oracle at Delphi. Accordingly, even the election of a duly elected tribune – if the oracle did not approve of him – had to be treated as annulled, and another had to be elected, of whom the oracle approved. The priest who put the question to the oracle was required, by sacred religious custom, to be one born of parents married in the mode the Romans called conferatio and this mode of marriage prevailed only among the patricians; so that the priest of Delphi was always a patrician.

The wily priest always saw to it that if the plebians elected a man really devoted to their cause, the oracle went against him. Only if the man elected by the plebians to the position of tribune was amenable to the patricians, would the oracle favour him and give him the opportunity of actually assuming office. What did the plebians gain by their right to elect a tribune? The answer must be, nothing in reality. Their efforts proved meaningless because they did not trace the malady to its source. If they had, they would, at the same time that they demanded a tribune of their election, have also settled the question of who should be the priest at Delphi. The disease could not be eradicated by demanding a tribune; it needed control of the priestly office; which the plebians failed to perceive. We too, while we seek a way to remove untouchability, must inquire closely into what will eradicate the disease; otherwise we too may miss our aim. Do not be foolish enough to believe that removal of the restrictions on social intercourse or interdrinking will remove untouchability.

Remember that if the prohibitions on social intercourse and interdrinking go, the roots of untouchability are not removed. Release from these two restrictions will, at the most, remove untouchability as it appears outside the home; but it will leave untouchability in the home untouched. If we want to remove untouchability in the home as well as outside, we must break down the prohibition against intermarriage. Nothing else will serve. From another point of view, we see that breaking down the bar against intermarriage is the way to establish real equality. Anyone must confess that when the root division is dissolved, incidental points of separateness will disappear by themselves. The interdictions on interdining, interdrinking and social intercourse have all sprung from the one interdiction against intermarriage. Remove the last and no special efforts are needed to move the rest. They will disappear of their own accord. In my view the removal of untouchability consists in breaking down the ban on intermarriage and doing so will establish real equality. If we wish to cut out untouchability, we must recognize that the root of untouchability is in the ban on intermarriage. Even if our attack today is on the ban against interdrinking, we must press it home against the ban on intermarriage; otherwise untouchability cannot be removed by the roots. Who can accomplish this task? It is no secret that the Brahmin class cannot do it.

If we wish to cut out untouchability, we must recognize that the root of untouchability is in the ban on intermarriage. Even if our attack today is on the ban against interdrinking, we must press it home against the ban on intermarriage; otherwise untouchability cannot be removed by the roots. Who can accomplish this task? It is no secret that the Brahmin class cannot do it.

While the caste system lasts, the Brahmin caste has its supremacy. No one, of his own will, surrenders power which is in his hands. The Brahmins have exercised their sovereignty over all other castes for centuries. It is not likely that they will be willing to give it up and treat the rest as equals. The Brahmins do not have the patriotism of the Samurais of Japan. It is useless to hope that they will sacrifice their privileges as the Samurai class did, for the sake of national unity based on a new equality. Nor does it appear likely that the task will be carried out by other caste Hindus. These others, such as the class comprising the Marathas and other similar castes, are a class between the privileged and those without any rights.

A privileged class, at the cost of a little self-sacrifice, can show some generosity. A class without any privileges has ideals and aspirations; for, at least as a matter of self-interest, it wishes to bring about a social reform. As a result it develops an attachment to principles rather than to self-interest. The class of caste Hindus, other than Brahmins, lies in between: it cannot practise the generosity possible to the class above and it does not develop the attachment to principles that develops in the class below. This is why this class is seen to be concerned not so much about attaining equality with the Brahmins as about maintaining its status above the untouchables.

For the purposes of the social reform required, the class of caste Hindus other than Brahmins is feeble. If we are to await its help, we should fall into the difficulties that the farmer faced, who depended on his neighbour’s help for his harvesting, as in the story of the mother lark and her chicks found in many textbooks.

The task of removing untouchability and establishing equality that we have undertaken, we must carry out ourselves. Others will not do it. Our life will gain its true meaning if we consider that we are born to carry out this task and set to work in earnest. Let us receive this merit which is awaiting us.

The task of removing untouchability and establishing equality that we have undertaken, we must carry out ourselves. Others will not do it. Our life will gain its true meaning if we consider that we are born to carry out this task and set to work in earnest. Let us receive this merit which is awaiting us.

This is a struggle in order to raise ourselves; hence we are bound to undertake it, so as to remove the obstacles to our progress. We all know how at every turn, untouchability muddies and soils our whole existence. We know that at one time our people were recruited in large numbers into the troops. It was a kind of occupation socially assigned to us and few of us needed to be anxious about earning our bread. Other classes of our level have found their way into the troops, the police, the courts and the offices, to earn their bread. But in the same areas of employment you will no longer find the untouchables.

It is not that the law debars us from these jobs. Everything is permissible as far the law is concerned. But the Government finds itself powerless because other Hindus consider us untouchables and look down upon us, and it acquiesces in our being kept out of Government jobs. Nor can we take up any decent trade. It is true, partly, that we lack money to start business, but the real difficulty is that people regard us as untouchables and no one will accept goods from our hands.

To sum up, untouchability is not a simple matter; it is the mother of all our poverty and lowliness and it has brought us to the abject state we are in today. If we want to raise ourselves out of it, we must undertake this task. We cannot be saved in any other way. It is a task not for our benefit alone; it is also for the benefit of the nation.

Untouchability is not a simple matter; it is the mother of all our poverty and lowliness and it has brought us to the abject state we are in today. If we want to raise ourselves out of it, we must undertake this task. We cannot be saved in any other way. It is a task not for our benefit alone; it is also for the benefit of the nation.

Hindu society must sink unless the untouchability that has become a part of the four-castes system is eradicated. Among the resources that any society needs in the struggle for life, a great resource is the moral order of that society. And everyone must admit that a society in which the existing moral order upholds things that disrupt the society and condemns those that would unite the members of the society, must find itself defeated in any struggle for life with other societies. A society which has the opposite moral order, one in which things that unite are considered laudable and things that divide are condemned, is sure to succeed in any such struggle.

This principle must be applied to Hindu society. Is it any wonder that it meets defeat at every turn when it upholds a social order that fragments its members, though it is plain to anyone who sees it that the four-castes system is such a divisive force and that a single caste for all, would unite society? If we wish to escape these disastrous conditions, we must break down the framework of the four-castes system and replace it by a single caste system.

Even this will not be enough. The inequality inherent in the four-castes system must be rooted out. Many people mock at the principles of equality. Naturally, no man is another’s equal. One has an impressive physique; another is slow-witted. The mockers think that, in view of these inequalities that men are born with, the egalitarians are absurd in telling us to regard them as equals. One is forced to say that these mockers have not understood fully the principle of equality.

If the principle of equality means that privilege should depend, not on birth, wealth, or anything else, but solely on the merits of each man, then how can it be demanded that a man without merit, and who is dirty and vicious, should be treated on a level with a man who has merit and is clean and virtuous? Such is a counter-question sometimes posed. It is essential to define equality as giving equal privileges to men of equal merit.

But before people have had an opportunity to develop their inherent qualities and to merit privileges, it is just to treat them all equally. In sociology, the social order is itself the most important factor in the full development of qualities that any person may possess at birth. If slaves are constantly treated unequally, they will develop no qualities other than those appropriate to slaves, and they will never become fit for any higher status. If the clean man always repulses the unclean man and refuses to have anything to do with him, the unclean man will never develop the aspiration to become clean. If the criminal or immoral castes are given no refuge by the virtuous castes, the criminal castes will never learn virtue.

The examples given above show that, although an equal treatment may not create good qualities in one who does not have them at all, even such qualities where they exist need equal treatment for their development; also, developed good qualities are wasted and frustrated without equal treatment.

On the one hand, the inequality in Hindu society stuns the progress of individuals and in consequence stunts society. On the other hand, the same inequality prevents society from bringing into use powers stored in individuals. In both ways, this inequality is weakening Hindu society, which is in disarray because of the four-castes system.

Hence, if Hindu society is to be strengthened, we must uproot the four-castes system and untouchability, and set the society on the foundations of the two principles of one caste only and of equality. The way to abolish untouchability is not any other than the way to invigorate Hindu society. Therefore I say that our work is beyond doubt as much for the benefit of the nation as it is in our own interest.

If Hindu society is to be strengthened, we must uproot the four-castes system and untouchability, and set the society on the foundations of the two principles of one caste only and of equality. The way to abolish untouchability is not any other than the way to invigorate Hindu society. Therefore I say that our work is beyond doubt as much for the benefit of the nation as it is in our own interest.

Our work has been begun to bring about a real social revolution. Let no one deceive himself by supposing that it is a diversion to quieten minds entranced with sweet words. The work is sustained by strong feeling, which is the power that drives the movement. No one can now arrest it. I pray to God that the social revolution which begins here today may fulfill itself by peaceful means.

None can doubt that the responsibility of letting the revolution take place peacefully rests more heavily on our opponents than on us. Whether this social revolution will work peacefully or violently will depend wholly on the conduct of the caste Hindus. People who blame the French National Assembly of 1789 for atrocities forget one point. That is, if the rulers of France had not been treacherous to the Assembly, if the upper classes had not resisted it, had not committed the crime of trying to suppress it with foreign help, it would have had no need to use violence in the work of the revolution and the whole social transformation would have been accomplished peacefully.

We say to our opponents too: please do not oppose us. Put away the orthodox scriptures. Follow justice. And we assure you that we shall carry out our programme peacefully.

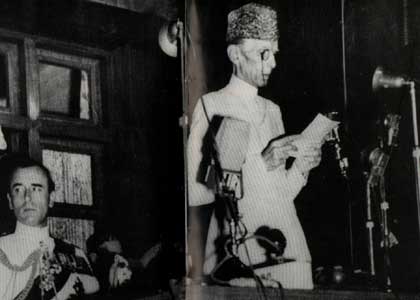

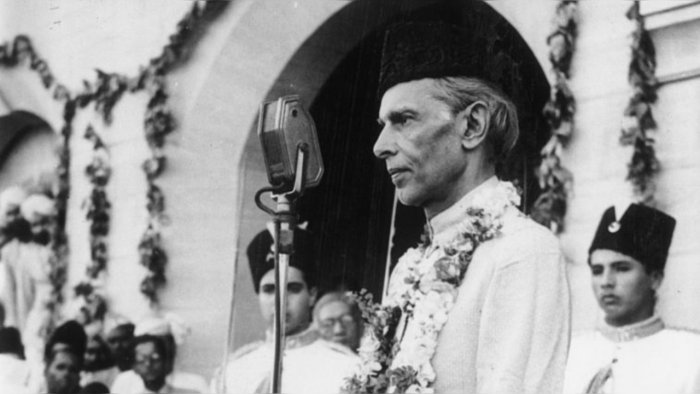

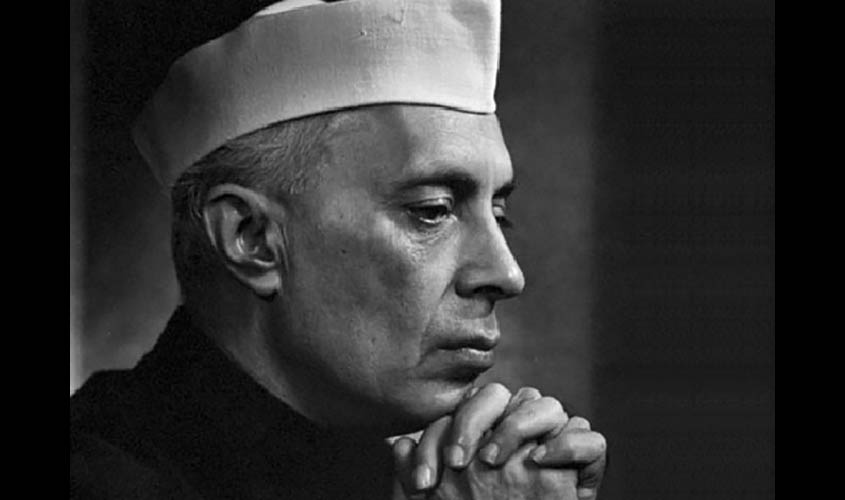

Purna Swaraj (Lahore, December 1929)

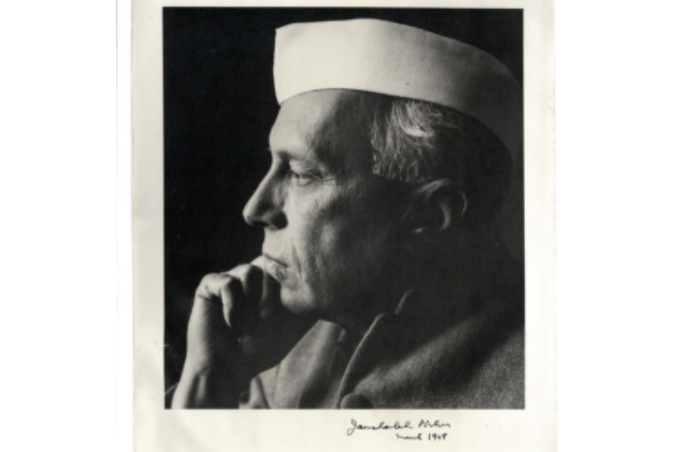

JAWAHARLAL NEHRU

Pledge for Purna Swaraj, Jawaharlal Nehru

Comrades— for four and forty years this National Congress has laboured for the freedom of India. During this period it has somewhat slowly, but surely, awakened national consciousness from its long stupor and built up the national movement. If, today we are gathered here at a crisis of our destiny, conscious of our strength as well as of our weakness, and looking with hope and apprehension to the future, it is well that we give first thought to those who have gone before us and who spent out their lives with little hope of reward, so that those that followed them may have the joy of achievement. Many of the giants of old are not with us and we of a later day, standing on an eminence of their creation, may often decry their efforts. That is the way of the world. But none of you can forget them or the great work they did in laying the foundations of a free India. And none of us can ever forget that glorious band of men and women who, without tacking the consequences, have laid down their young lives or spent their bright youth in suffering and torment in utter protest against a foreign domination.

Many of their names even are not known to us. They laboured and suffered in silence without any expectation of public applause, and by their heart’s blood they nursed the tender plant of India’s freedom. While many of us temporized and compromised, they stood up and proclaimed a people’s right to freedom and declared to the world that India, even in her degradation, had the spark of life in her, because she refused to submit to tyranny and serfdom. Brick by brick has our national movement been built up, and often on the prostrate bodies of her martyred sons has India advanced. The giants of old may not be with us, but the courage of old is with us still and India can yet produce martyrs like Jatin Das and Wizaya. This is the glorious heritage that we have inherited and you wish to put me in charge of it. I know well that I occupy this honoured place by chance more than by your deliberate design. Your desire was to choose another — one who towers above all others in this present day world of ours — and there could have been no wiser choice. But fate and he conspired together and thrust me against your will and mine into this terrible seat of responsibility. Should I express my gratitude to you for having placed me in this dilemma? But I am grateful indeed for your confidence in one who strangely lacks it himself.

Brick by brick has our national movement been built up, and often on the prostrate bodies of her martyred sons has India advanced. The giants of old may not be with us, but the courage of old is with us still and India can yet produce martyrs like Jatin Das and Wizaya. This is the glorious heritage that we have inherited and you wish to put me in charge of it.

You will discuss many vital national problems that face us today and your decisions may change the course of Indian history. But you are not the only people that are faced with problems. The whole world today is one vast question-mark and every country and every people is in the melting pot. The age of faith, with the comfort and stability it brings, is past and there is questioning about everything, however permanent or sacred it might have appeared to our forefathers. Everywhere, there is doubt and restlessness and the foundations of the state and society are in process of transformation. Old established ideas of liberty, justice, property, and even the family are being attacked and the outcome hangs in the balance. We appear to be in a dissolving period of history when the world is in labour and out of her travail will give birth to a new order.

The future lies with America and Asia. Owing to false and incomplete history many of us have been led to think that Europe has always dominated over the rest of the world, and Asia has always let the legions of the West thunder past and plunged in thought again. We have forgotten that for millennia the legions of Asia overran Europe and modern Europe itself largely consists of the descendants of these invaders from Asia. We have forgotten that it was India that finally broke the military power of Alexander.

No one can say what the future will bring, but we may assert with some confidence that Asia and even India, will play a determining part in future world policy. The brief day of European domination is already approaching its end. Europe has ceased to be the centre of activity and interest. The future lies with America and Asia. Owing to false and incomplete history many of us have been led to think that Europe has always dominated over the rest of the world, and Asia has always let the legions of the West thunder past and plunged in thought again. We have forgotten that for millennia the legions of Asia overran Europe and modern Europe itself largely consists of the descendants of these invaders from Asia. We have forgotten that it was India that finally broke the military power of Alexander.

Thought has undoubtedly been the glory of Asia and specially of India, but in the field of action the record of Asia has been equally great. But none of us desires that the legions of Asia or Europe should overrun the continents again. We have all had enough of them.

India today is a part of a world movement. Not only China, Turkey, Persia, and Egypt but also Russia and the countries of the West are taking part in this movement, and India cannot isolate herself from it. We have our own problems — difficult and intricate — and we cannot run away from them and take shelter in the wider problems that affect the world. But if we ignore the world, we do so at our peril. Civilization today, such as it is, is not the creation or monopoly of one people or nation. It is a composite fabric to which all countries have contributed and then have adapted to suit their particular needs. And if India has a message to give to the world as I hope she has, she has also to receive and learn much from the messages of other peoples.

Few things in history are more amazing than the wonderful stability of the social structure in India, which withstood the impact of numerous alien influences and thousands of years of change and conflict. It withstood them because it always sought to absorb them and tolerate them. Its aim was not to exterminate, but to establish an equilibrium between different cultures. Aryans and non-Aryans settled down together recognizing each other’s right to their culture, and outsiders who came, like the Parsis, found a welcome and a place in the social order. With the coming of the Muslims, the equilibrium was disturbed, but India sought to restore it, and largely succeeded. Unhappily for us before we could adjust our differences, the political structure broke down, the British came and we fell.

When everything is changing it is well to remember the long course of Indian history. Few things in history are more amazing than the wonderful stability of the social structure in India, which withstood the impact of numerous alien influences and thousands of years of change and conflict. It withstood them because it always sought to absorb them and tolerate them. Its aim was not to exterminate, but to establish an equilibrium between different cultures. Aryans and non-Aryans settled down together recognizing each other’s right to their culture, and outsiders who came, like the Parsis, found a welcome and a place in the social order. With the coming of the Muslims, the equilibrium was disturbed, but India sought to restore it, and largely succeeded. Unhappily for us before we could adjust our differences, the political structure broke down, the British came and we fell.

Great as was the success of India in evolving a stable society, she failed and in a vital particular, and because she failed in this, she fell and remains fallen. No solution was found for the problem of equality. India deliberately ignored this and built up her social structure on inequality, and we have the tragic consequences of this policy in the millions of our people who till yesterday were suppressed and had little opportunity for growth.

And yet when Europe fought her wars of religion and Christians massacred each other in the name of their saviour, India was tolerant, although alas, there is little of this toleration today. Having attained some measure of religious liberty, Europe sought after political liberty, and political and legal equality. Having attained these also, she finds that they mean very little without economic liberty and equality. And so today politics have ceased to have much meaning and the most vital question is that of social and economic equality.

India also will have to find a solution to this problem and until she does so, her political and social structure cannot have stability. That solution need not necessarily follow the example of any other country. It must, if it has to endure, be based on the genius of her people and be an outcome of her thought and culture. And when it is found, the unhappy differences between various communities, which trouble us today and keep back our freedom, will automatically disappear.

What shall we gain for ourselves or for our community, if all of us are slaves in a slave country? And what can we lose if once we remove the shackles from India and can breathe the air of freedom again? Do we want outsiders who are not of us and who have kept us in bondage, to be the protectors of our little rights and privileges, when they deny us the very right to freedom? No majority can crush a determined minority and no minority can be protected by a little addition to its seats in a legislature. Let us remember that in the world today, almost everywhere a very small minority holds wealth and power and dominates over the great majority.