ARCHIVE

Alwar and the princely affair

2 February 1948

Soon after the assassination, the police and intelligence agencies started putting the pieces together. The anti-Gandhi rhetoric from Delhi’s neighbouring princely state Alwar was too loud to escape the radar of the intelligence bureau. Alwar is barely three hours from Delhi and was a stronghold of the right-wing movement at that time, which received patronage from its Maharaja and his strongman prime minister, Dr. Narayan Bhaskar Khare. There were also intelligence reports from Alwar that a godman, a guest of Alwar Municipal Commissioner Giridhar Sharma, had announced that Gandhi was dead at least two hours before the assassination.

Because of this, just two days after the assassination, a police team was dispatched to the state.

Prime Minister N.B. Khare should have been a natural suspect. It was only a few months back, on 12 October 1947, that he had put a ‘Brahmin’s Curse’ on Gandhi. There was also overwhelming evidence of Khare supporting militant Hindu leaders. However, he did not figure in the final charge sheet of the Delhi Police, nor was he indicted by the Jeevan Lal Kapur Commission set up twenty years later. The commission did cast a shadow over the roles of Khare and Alwar state in the conspiracy but gave them the benefit of doubt.

Once again, a key figure in the assassination was let go in absence of ‘conclusive evidence’. The commission, in its report, established Khare’s role in the following words:

“Dr. Khare’s antecedents and his encouragement to the R.S.S. and to the militant Hindu Mahasabha leaders were indicative of conditions being produced which were conducive to strong anti-Gandhi activities including a kind of encouragement to those who thought that Mahatma Gandhi’s removal will bring about a millennium of a Hindu Raj. But on this evidence the Commission cannot come to the conclusion that there was an active or tacit encouragement to people like Nathuram Godse to achieve the objective of their conspiracy to commit murder of Mahatma Gandhi. But there is no doubt that an atmosphere was being created which was anti-Gandhi even though it may not have been an encouragement to the persons who wanted to murder Mahatma Gandhi.”

“Dr. Khare’s antecedents and his encouragement to the R.S.S. and to the militant Hindu Mahasabha leaders were indicative of conditions being produced which were conducive to strong anti-Gandhi activities including a kind of encouragement to those who thought that Mahatma Gandhi’s removal will bring about a millennium of a Hindu Raj. But on this evidence the Commission cannot come to the conclusion that there was an active or tacit encouragement to people like Nathuram Godse to achieve the objective of their conspiracy to commit murder of Mahatma Gandhi. But there is no doubt that an atmosphere was being created which was anti-Gandhi even though it may not have been an encouragement to the persons who wanted to murder Mahatma Gandhi.”

Did the commission have full access to the material collected by the Delhi Police and the Intelligence Bureau against Khare? The internal investigation documents tell a different story from its report and suggest strong evidence linking Khare’s role to Gandhi’s assassination.

The godman in question who announced Gandhi’s assassination two hours in advance was Gopi Krishna Vyas alias Om Baba. He was the same person Madanlal had mentioned meeting at the Hindu Mahasabha Bhawan ahead of the failed assassination attempt. Om Baba and Madanlal shared Room No. 3 on the night of 19 January after a police car dropped the former at the Hindu Mahasabha Bhawan. He had been in jail for disrupting Gandhi’s prayer meeting on 13 January. On that day, when Gandhi had started reciting verses from the Quran, Om Baba chanted Vedic mantras. In police custody, Om Baba began a hunger strike which led to his eventual release.

Room No. 3 is where the dots around the conspiracy of Gandhi’s assassination start to get connected to Alwar.

On 7 March, DSP Jaswant Singh wrote a secret note to the director, Intelligence Bureau, and to Inspector General D.W. Mehra:

“Ram Singh, an employee of the Hindu Mahasabha Bhawan, Delhi, has been traced today. He states that four or five men (One Hindu Punjabi and four Marhattas) stayed in Room No. 3 of the Hindu Mahasabha Bhawan. He saw these men on 20.1.1948 and talked with them. These men left the place at about 8 A.M. They again came at 12.00 hours and after a short time they left in a car. He further states that one of them came at about 8. P.M and gave him a chit bearing him address of Poona in Hindi for delivering to one Inder Prakash member of the Hindu Mahasabha. He could not deliver it to Inder Prakash as the latter was not present in the Bhawan … [sic]”

This is the part recorded by Singh in his case diary. His secret note continues:

“He further states that a secret meeting took place at Hindu Mahasabha Bhawan 2/3 days before the bomb explosion and Sham Lal Verma, Professor Ram Singh [not the same as the Ram Singh mentioned earlier], Dr. Khere and Mrs. Dr. Khere took part in the meeting. He cannot tell anything about the proceedings of the meeting. Ram Singh states that he can identify all the men who stayed in room No. 3. This Ram Singh claimed to be an ex- I.N.A worker. He was arrested in Chittagong in 1943 and the death sentence was awarded to him on the charge of being 5th columnist but was later on released on appeal. [sic]”

It could be that Singh was waiting for directions from his superiors to pursue the lead, but the case diaries show that it was not investigated any further.

*

Back to Room No. 3.

During his stay, Om Baba met Shyam Lal Verma, the editor of a Delhi-based Hindi newspaper, Singh Nad. This person was also named by Ram Singh, the servant at the Hindu Mahasabha, as part of the secret meeting ahead of the failed assassination attempt.

On 28 January 1948, Shyam Lal and Om Baba travelled to Alwar by train. Both stayed at Girdhar Sharma’s house. On the day of the assassination, according to Om Baba, ‘I remember that day he [Shyam Lal] wanted to see the Maharaja of Alwar.’

If this was not enough, an undated interrogation report of Har Lal further independently links those who were mentioned by Ram Singh to the alleged Alwar conspiracy.

Har Lal, a shawl merchant in Old Delhi who was part of the police intelligence network, gave a statement to the Delhi Police in which he said that his business partner Ram Gopal and Har Lal’s son had prior knowledge of the assassination. A thorough reading of the statement indicates that Har Lal was trying to exonerate himself and obtain the benefit of doubt for his son. His statement reads as follows: ‘I also heard Ram Gopal talk with Om Prakash a few day before the assassination of Mahatma Ji, that Doctor Khare had been arranging for the assassination of Mahatma Ji, and he would know the result very soon that Mahatma Ji would be shot down.’ [sic]

Har Lal, a shawl merchant in Old Delhi who was part of the police intelligence network, gave a statement to the Delhi Police in which he said that his business partner Ram Gopal and Har Lal’s son had prior knowledge of the assassination. A thorough reading of the statement indicates that Har Lal was trying to exonerate himself and obtain the benefit of doubt for his son.

The Ram Gopal in question was a leader of the Arya Samaj and a member of the Hindu Mahasabha Working Committee, who was very thick with Professor Ram Singh.

The case diaries related to the investigations show that none of these leads was actively pursued. Which is surprising, considering that M.M.L. Hooja, then deputy director of the Intelligence Bureau who was investigating the Delhi locals for possible links to Gandhi’s assassination, said, in a note dated 23 February 1948 to the director of the Intelligence Bureau, that Nathuram Shukla was ‘suspected to be the same man as Nathuram Godse’.

During the initial phase of the investigation, as early as 7 February, the probe team in Alwar had concluded that Nathuram Shukla, who was rumoured to be in Alwar ahead of the assassination, was a Hindi journalist. Hooja, who later became director, Intelligence Bureau, was incidentally holding office when the Jeevan Lal Kapur Commission was conducting the re-investigation of the case.

Let us look at the contradictions in the case.

Appearing before the Kapur Commission, Khare was quoted as saying that he ‘knew Nathuram Godse only slightly because when he visited Poona as Member of Viceroy’s council, Godse came to call on him.’

The word that needs emphasis here is ‘slightly’. The report made it sound as if Godse was a distant acquaintance of Khare whom he had met at a function. The commission continued citing Khare in its report: ‘He [Khare] did not know that he [Godse] was a leader of the Rashtriya Dal but he did know that he was the editor of the paper Agrani.’

Sometimes a simple lie can reveal a lot.

One of the early interrogation reports of Godse recorded him as saying: ‘I have never been to Alwar. I had seen in the newspapers that I have been reported to visit Alwar but this is incorrect. I am not acquainted to any of the Hindu Sabha worker of Alwar.’9 [sic] He thus distanced Khare or any other senior functionaries of Alwar state from being linked to the assassination conspiracy. But his following remarks contradict the public stand taken by Khare:

“But I know Doctor Kharai [Khare], the prime minister of Alwar. The last time I have met Doctor Kharai [Khare] about a year back at Poona when he had met Dr Kharai [Khare] over there. Before this I had met Dr Kharai [Khare] so many times. I had been knowing Doctor Kharai [Khare] because he was a Hindu Sabha leader. [sic]”

Clearly, the familiarity between Godse and Khare is much more than ‘slight’. It was a relationship that Khare, of course, wanted to hide. But it is intriguing why the investigating officers at the time did not confront both Khare and Godse with the contradictions of their statements, instead of simply accepting their respective versions.

Clearly, the familiarity between Godse and Khare is much more than ‘slight’. It was a relationship that Khare, of course, wanted to hide. But it is intriguing why the investigating officers at the time did not confront both Khare and Godse with the contradictions of their statements, instead of simply accepting their respective versions.

Khare did not just lie about Godse. He claimed no previous association with another accused, Dattatreya Parchure. The Kapur Commission, quoting Khare, stated in its report, ‘He did not meet Parchure before 1952 but met him at Gwalior when he went there for election to Parliament. He knew Apte also slightly.’

Nilkantha Dattatreya Parchure, son of Dr Parchure, gave a statement to the police on 15 February 1948: ‘Dr N.B. Khare had visited after the last Dusera festival to preside over the Vijaya Lashmi Utsavs and he addressed a meeting stressing the need of Consolidation of the Hindu Rashtra Sangh.’ [sic]

The Dusshera of 1947 was on 24 October. This was just a few weeks before Parchure had gone to Bombay and also met with Savarkar and Karkare.

An undated, unsigned statement recorded by the police probe team does not touch on any aspect of the intelligence that was available to them at that time. Going by the content, the two-page statement seems to be a mere formality.

The probe officer recorded:

“I had a talk with Doctor Khare at 11 Cannen Lane, New Delhi, this morning … he further stated that he does not know anything about any Hindu Rashtriya Dal [sic] whether or not it came to existence in Alwar or in any other place … He has no knowledge of any posters having been distributed by any Sadhu or a sanyasi in Alwar state. He, however, heard in Alwar on his visit to that place on 4.2.1948 that some police officers from Delhi had been to Alwar and recovered Hindi poster against Mahatma Gandhi.”

Right from the beginning, officials of Alwar state were defensive. Inspector Balmukund from the Delhi Police, who was deputed to visit Alwar on 2 February to investigate the incident involving Om Baba announcing Gandhi’s murder prior to the actual incident, noted the following conversation with the inspector general of police, Alwar, in his report to his seniors:

“The state police would be very glad to give every kind of help to Delhi Police in carrying out the investigation of this case but they would request the Investigation Officer to investigate all the charges against the State people at the spot i.e., at Alwar. They fear that the interested persons from the State may not misguide the Investigating Officer and other high officials by giving them wrong informations. [sic]”

The Kapur Commission, while discussing whether Nathuram Shukla was indeed Nathuram Godse, made the following observation that laid out the inherent bias: ‘Investigation was unfortunately hampered by the fact that the local police was unreliable and even the I.G.P. was a “staunch Rajput”.’

Clearly, the police in Delhi as well as in Alwar were soft on Khare.

The Kapur Commission, while discussing whether Nathuram Shukla was indeed Nathuram Godse, made the following observation that laid out the inherent bias: ‘Investigation was unfortunately hampered by the fact that the local police was unreliable and even the I.G.P. was a “staunch Rajput”.’

Clearly, the police in Delhi as well as in Alwar were soft on Khare.

*

It was the month of August in 1947 that brought together the different actors who were suspected of planning Gandhi’s assassination.

N.B. Khare started the All India Hindu National Front in Delhi in August 1947, which was presided over by Savarkar. It was a meeting of important leaders, including some princes. According to the Kapur Commission reports, Khare couldn’t be present at the meeting because of trouble in Alwar. Nor was the Maharaja of Alwar present. However, this does not mean that Khare did not have the opportunity to meet with Savarkar before the assassination; they met in November 1947 in Bombay.

Bloodstained Shawl of Gandhi. Photo Division

The Alwar episode raises the question: Why would the princely states want Gandhi assassinated? The answer lies in the views Gandhi expressed in the years closer to Independence.

The Alwar episode raises the question: Why would the princely states want Gandhi assassinated? The answer lies in the views Gandhi expressed in the years closer to Independence.

The first clue is in a letter Gandhi wrote to Shriman Narayan on 1 December 1945 while on board a train to Calcutta: ‘It is worth considering if Pakistan and the Princes can have any place in my conception [of India]. Remember that the Gandhian plan can be successful only if it can be achieved through non-violent means.’

Shriman Narayan was a Gandhian economist and professor in Wardha, the site of Gandhi’s ashram Sevagram. He had a longstanding correspondence with Gandhi on several matters, particularly on Gandhian economics. He had even sent the proofs of his book on Gandhian economics to Mahatma Gandhi for his comments.

Gandhi’s position vis-à-vis the princes and the princely states is made clearer in his later letters. His letter to Sir Stafford Cripps, who led the Cripps Mission to India in 1942, on 12 April 1946 was a step closer to the hardening stand one observes in his writings ahead of Independence.

Dear Sir Stafford,

What I wanted to say and forgot last night was about the States of India. Pandit Nehru is the President of the States’ People’s Conference and Sheikh Abdullah of Kashmir its Vice-President. I met the committee of the Conference last Wednesday. Their complaint was that they were ignored by the Cabinet Delegation whereas the Princes were receiving more than their due attention. Of course this may be good policy. It may also be bad policy and morally indefensible. The ultimate result may be quite good, as it must be, if the whole of India becomes independent. It will then be bad to irritate the people of the States by ignoring them. After all the people are everything and the Princes, apart from them, nothing. They owe their artificial status to the Government of India but their existence to the people residing in the respective States. This may be shared with your colleagues or not as you wish. It is wholly unofficial as our talk last night was.

Yours sincerely,

M. K. GANDHI

An expert political strategist, Gandhi’s letter to Sir Stafford was no coincidence as the Cabinet Delegation to discuss transfer of power from the British to the Indian leaders, which included Cripps, had arrived in Delhi three weeks ago on 24 March 1946.

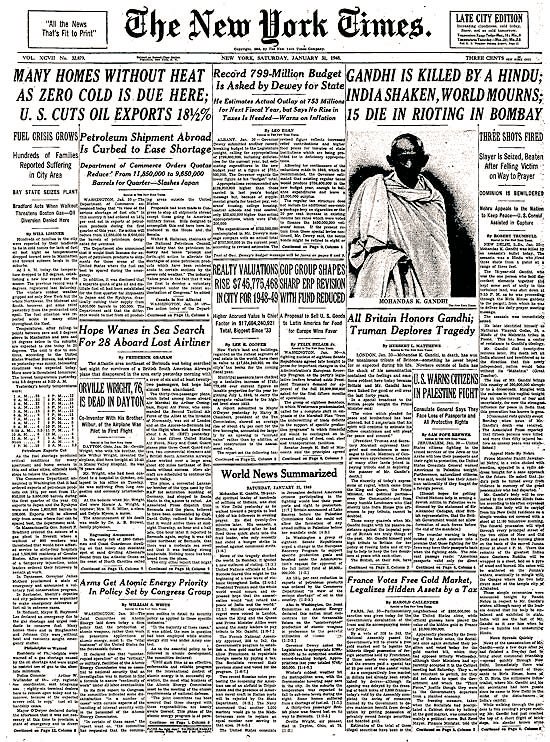

The New York Times Front Page On Gandhi’s Assassination

With independence in sight, Gandhi’s attention was focused on the post-colonial governance. This was also the time that Gandhi was formulating his thoughts on trusteeship, which ran diametrically opposite to the economic interests of the elite, particularly the Hindu elite represented by the princely states.

With independence in sight, Gandhi’s attention was focused on the post-colonial governance. This was also the time that Gandhi was formulating his thoughts on trusteeship, which ran diametrically opposite to the economic interests of the elite, particularly the Hindu elite represented by the princely states.

Before these letters, Gandhi had aired his views on ‘trusteeship’ in an article about him in The Hindu on 9 September 1945, a week after the Second World War ended on 2 September 1945. The war had broken the back of the British empire and it was no secret that the British government was inclined to hand over the reins to India.

“On the question of trusteeship, which was absent from the constitution of the Sangh, Mahatma Gandhi is said to have pointed out that since the theory of trusteeship was stressed by him and had a permanent association with his name, it was legitimate to make it a matter of dispute. He said that he did not want to accentuate class-struggle. The owners should become trustees. They might insist that they should become trustees and yet they might choose to remain owners. We shall then have to oppose and fight them. Satyagraha will then be our weapon. Even if we want a classless society we should not engage in a civil war. Non-violence should be depended upon to bring a classless society.”

The Hindu elite, particularly the Hindu Mahasabha, were of the view that the princely states were the custodians of Indian culture. Contrast the Gandhian view, as explicitly expressed in his letter to Narayan, with that of the Hindu Mahasabha, led by Savarkar’s effort to strategically position the princely states in the future of India.

The Hindu elite, particularly the Hindu Mahasabha, were of the view that the princely states were the custodians of Indian culture. Contrast the Gandhian view, as explicitly expressed in his letter to Narayan, with that of the Hindu Mahasabha, led by Savarkar’s effort to strategically position the princely states in the future of India.

Since the electoral debacle for the Hindu Mahasabha in 1937 and the heightened focus on militarization of Hindus, the princely states had become a strategic partner to the Hindu right. In April 1944, the Mahasabha under Savarkar organized three major conferences on the topic of the role of princely states in the idea of India.

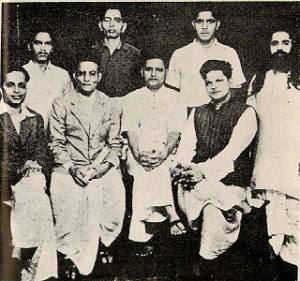

A group photo of people accused in the Gandhi murder case. Standing: Shankar Kistaiya, Gopal Godse, Madanlal Pahwa, Digambar Badge. Sitting: Narayan Apte, Vinayak D. Savarkar, Nathuram Godse, Vishnu Karkare

Dr Balkrishna Shivram Moonje, Savarkar’s close aide and a prominent Mahasabha leader as well as the man leading the efforts to militarize the Hindus, in his presidential address to the Baroda Hindu Sabha in April 1944, one of the three aforementioned conferences, laid out the Mahasabha vision.

“The Prince who is ruling the States is a representative of the Hindu Raj of the past and as such incorporates in himself all traditions of dignity and is suffering and fighting for maintaining the Hindu Raj against foreign opponents who were opposing them during the past 500 years or so … The Hindu Mahasabha therefore calls upon all Hindus to respect and love their Hindu Princes as embodiments of Hindu pride and Hindu achievements in the political world of the past and as hopeful in the future.”

“The Prince who is ruling the States is a representative of the Hindu Raj of the past and as such incorporates in himself all traditions of dignity and is suffering and fighting for maintaining the Hindu Raj against foreign opponents who were opposing them during the past 500 years or so … The Hindu Mahasabha therefore calls upon all Hindus to respect and love their Hindu Princes as embodiments of Hindu pride and Hindu achievements in the political world of the past and as hopeful in the future.”

The princely state was not a single unit. There was the Prince or Maharaja who was an inheritor of the right to rule and a princely bureaucracy comprising officials such as Khare who had more clout than the inheritor himself. Gandhi correctly identified that the princely bureaucracy was interested in continuing to hold power in a post-colonial structure.

In an article in Harijan on 4 August 1946, Gandhi called out the princes but his target was the princely bureaucracy.

“As it is, the Princes have taken the lead only in copying the bad points of the British system. They allow themselves to be led by the nose by their Ministers, whose administrative talent consists only in extorting money from their dumb, helpless subjects. By their tradition and training they are unfitted [sic] to do the job you have let them do.”

In the mêlée of Hindu-Muslim conflict and the partition politics, an unnoticed war was being waged between Gandhi and the princely states, even as the ideologues of Hindutva courted the princely states, some led by Savarkar and others by Moonje. The ten-year period between 1937 and 1947 saw the perfect marriage between the militant Hindu nationalism of Savarkar–Moonje and the princely states.

In the mêlée of Hindu-Muslim conflict and the partition politics, an unnoticed war was being waged between Gandhi and the princely states, even as the ideologues of Hindutva courted the princely states, some led by Savarkar and others by Moonje. The ten-year period between 1937 and 1947 saw the perfect marriage between the militant Hindu nationalism of Savarkar–Moonje and the princely states.

Savarkar wrote to the Maharaja of Jaipur on 19 July 1944:

“Your Highness must have noted or heard personally from other princes that it was entirely due to my lead that the Hindu Mahasabha as an organization has avowedly embraced a policy of standing by the Hindu states and defending their prestige, stability and power against the Congressites, the Communists, the Moslems and such other internal and external sections who openly declared that they aimed to uproot the Hindu states and encourage every effort to embarrass them and create bad blood between their subjects and themselves. Every Hindu Sabha in a Hindu state is today the only body which takes its stand on the fundamental principle of protecting Hindu states as a part of their duty as Hindus. The Hindu Mahasabha has declared that the Hindu states are centres of Hindu power. The policy carried into effect by my tour of different states succeeded in creating in every Hindu State organised bodies of Hindu Sanghatanists whose loyalty to the State and the Prince was above question.”

The essence of this letter portrays—and rightfully so—Gandhi as an arch enemy of the princely states. This conflict escalated closer to Independence. Both Gandhi and the princely states had a different idea about the role of the states in independent India.

In a 26 November 1946 article in Harijan, Gandhi was blunt:

“It is the people who want and are fighting for independence, not the Princes who are sustained by the alien power even when they claim not to be its creation for the suppression of the liberties of the people. The Princes, if they are true to their professions, should welcome this popular use of paramountcy so as to accommodate themselves to the sovereignty of the people envisaged.”

Contrast this stand by Gandhi with that of the Maharaja of Alwar: ‘It is the forefathers of the present rulers who have saved India from Muslim domination. The same task lies ahead and we call upon the Hindu Princes to play their rightful role and save the Hindu nation from extinction.’

This appeared as a lead article in the Hindu Outlook, the mouthpiece for the Hindu Mahasabha, on 11 March 1947.

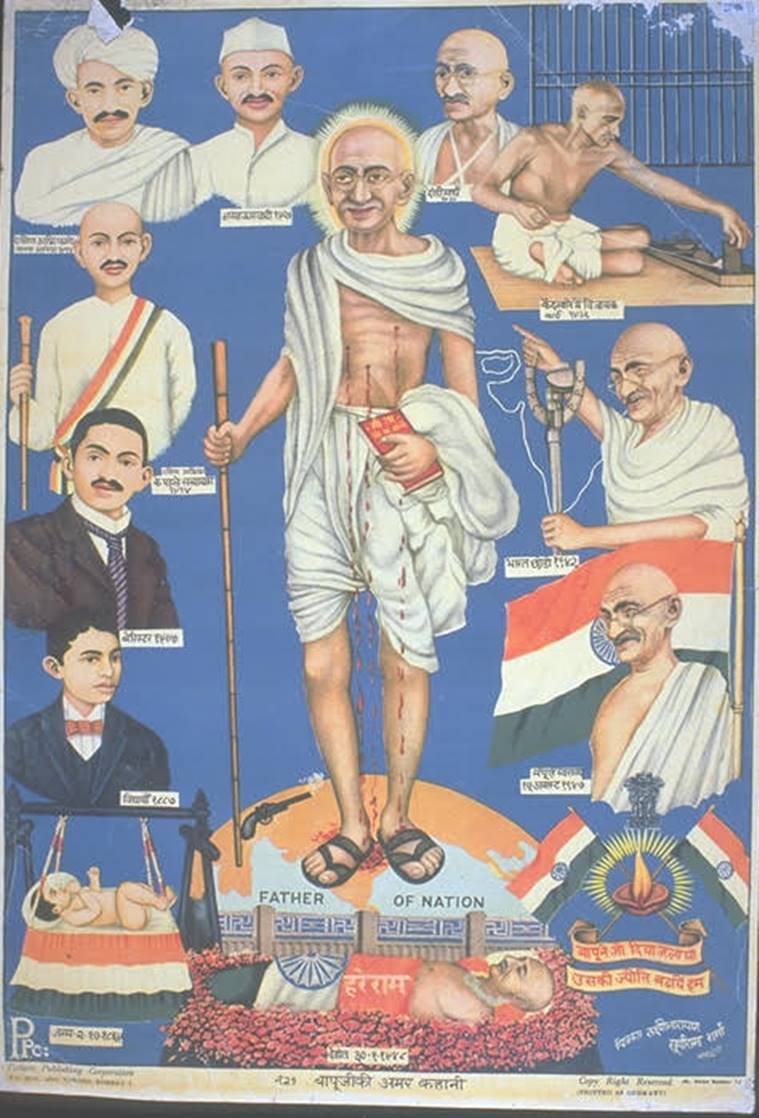

Gandhi’s assassination in poster art (Picture provided by Sumathy Ramaswamy) Credit: The Indian Express

Less than a month later, on 4 April 1947, Gandhi, in a one-on-one meeting with Lord Mountbatten, brought up the British strategy of fighting princely states against the Muslim League.

The minutes of the meeting marked ‘top secret’ stated:

“Mr. Gandhi spoke about the Princes. He said that the Princes were really the creation of the British; that many of them had been gradually created up from small chieftains to the position they now held, because the British realized that they would become strong allies of the British under the system of paramountcy.

In fact he maintained that the British had, from the imperialistic point of view, acted very correctly in backing the Princes and the Muslim League, since between these two, had we played our cards really well, we could have claimed it was impossible for us even to leave India.”

“Mr. Gandhi spoke about the Princes. He said that the Princes were really the creation of the British; that many of them had been gradually created up from small chieftains to the position they now held, because the British realized that they would become strong allies of the British under the system of paramountcy….”

*

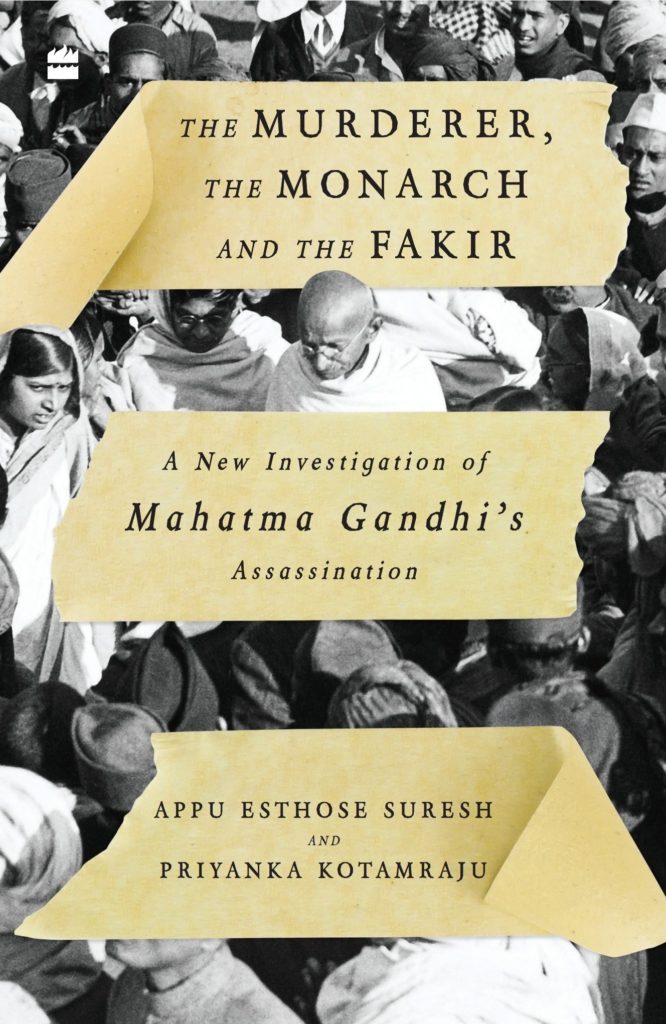

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of HarperCollins India. You can buy The Murderer, The Monarch and The Fakir: A New Investigation of Mahatma Gandhi’s Assassination here.

ARCHIVE

PREFACE

Andal’s life and legend is so completely founded in the divine that merely thinking of translating Andal ought to make one speechless, struck with ineffability. Additionally, the genre of ancient Tamil poetry to which the Thiruppavai and the Naciyar Thirumoli belong is said to incorporate inner spaces, hidden meanings. How, then, might a translator go about the task of translating Andal, if one dares at all? Priya Sarukkai Chabbria and Ravi Shankar seem to derive their translation strategy from this openfield in Andal’s poetics.

There are two Andals in this book: Priya’s Andal, and Ravi’s Andal. The two translators do not divide Andal, they share her entirely, translating the same poems. Reading their translations one after another may alarm a reader who has dogmatic expectations of translations, or fixed ideas about fidelity; she may stop and wonder, which is the ‘real’ translation, which particular, ‘true’? Are Andal’s breasts in Pasuram 8 the ‘full hills’ of Priya’s translation or supple ‘upturned blossoms’ of Ravi’s?

Recognising the distinct styles and divergent translations of Priya and Ravi calls to mind the story of the Septuagint, where seventy-two translators come up with an identical translation of the Hebrew Bible. While this example is usually cited to establish the authenticity and the fidelity of that translation, it has always raised for me another question, the reality of the process. Can the translator be said to exist, if she is transparent? Even Anne Carson, whose exacting translation of Sappho places us as if right next to a poem fragment on an ancient papyrus, admits: “I like to think that, the more I stand out of the way, the more Sappho shows through. This is an amiable fantasy (transparency of self) within which most translators labor.” Every translator has a unique lens. This is not just about interpretation, an intellectual activity, this is also about personality, personal history, biography. An Urdu couplet explains it well: Ishq ki chot toh padti hi har dil pe iksaan. Zarf ke farq se avaaz badal jati hai. ‘The strike or the hurt of love falls the same way on each heart/mind, but depending on the material (i.e., nature, character, what stuff the person is made of) it sounds different.’ We must expect translations to be individual, otherwise the task of the translator may as well be the ‘task of the computer,’ or even the ‘task of the dictionary.’

Andal’s life and legend is so completely founded in the divine that merely thinking of translating Andal ought to make one speechless, struck with ineffability. Additionally, the genre of ancient Tamil poetry to which the Thiruppavai and the Naciyar Thirumoli belong is said to incorporate inner spaces, hidden meanings.

Priya uses imperatives (‘come, make this vow’), nouns as verbs (‘to hymn his magic’), and graphic images (‘lightning nerved air’) for a translation charged with momentum and force. Her triptych in Nachiyar is an enactment (abhinaya) much like in a dance-drama, where a statement is presented once, and then again, and then again, slightly different each time, the rasa more heightened. Assuming the first part is most literal, or as literal as you can get with Andal, and the second stanza yet another translation or telling, carrying an echo or trace of the first, the third stanza is a mutter, a trailing off, an entry into the psyche of Andal and the translator so impacted that she continues to voice her, not quite consciously. Ravi’s translation startles expectations that we may have of men-translators translating a woman-poet. In Take Me to the Land of My Lord, Andal asks, ‘[l]eave me there on my haunches,’ the limbs of Hrisikesa (Krishna) ‘quivering in time like a veena string’ – his translation embodies Andal. Ravi also circumambulates the ideas and images of a poem with each stanza, but works his imaginary into a smooth, narrative flow. Both translators bring us the textures of Tamil; whereas Ravi intersperses Tamil words in his translation, Priya’s English itself seems shaped by the source language. Their two Andals walk alongside. If Priya’s Thiruppavai is solemn, chant-like, Ravi’s Thiruppavai is conversational. Priya tells us that the gopis’ hands are too small to enclose the udders of the cows. Ravi tells us the udders groan to fill the pots. Two sets of eyes trained on the scene, the vision of the reader gains depth; and returning to the same poems from two different angles that are also rich spectrums in themselves drives the reader into the deep, of Andal. While Priya and Ravi respond to Andal, they also seem to respond to each other. What Ravi presents in Dark Flower expands into a bouquet in Priya, or perhaps Priya first shows us the flowers, and then Ravi the bunch? The collaborative strategy has an expansive effect, it is Andal who proliferates.

In order to appreciate, understand, or just locate the methodology of this Andal translation, it is useful to consider the conventions of how a ‘text’ or a source thrives in the Indian tradition. When we find railway metaphors in a song attributed to circa 15th century Kabir, we know that the corpus of Kabir represents an imaginary, Kabir songs pay homage to the collective idea of Kabir. And we do not split hairs over the definition of the Tulsidas Ramayana, wonder whether it is a translation, version, adaptation, creative translation, transcreation, retelling or commentary. It is multiplicity that achieves the transmission and continuity of source texts, whether oral, or written. Texts that we think of as ‘fixed’ also assimilate the voices of readers. Look at the tradition of Gita dissemination—it has relied, and continues to rely, on people who study, recite, translate, explain and comment on the Gita while drawing from previous commentaries (bhasyas). It is only in the context of modern book-culture that we expect a Gita translation to be the ‘representation’ of a source text, and expect commentary within footnotes and with reduced emphasis. And if we do not regard many Gita translations as many Gitas, that is a comment on our expectations of translations, and on our naiveté about interpretation, not on a translation’s management of fidelity.

In order to appreciate, understand, or just locate the methodology of this Andal translation, it is useful to consider the conventions of how a ‘text’ or a source thrives in the Indian tradition. When we find railway metaphors in a song attributed to circa 15th century Kabir, we know that the corpus of Kabir represents an imaginary, Kabir songs pay homage to the collective idea of Kabir.

Then the bhakti tradition admits intuition as methodology. In The Flute Calls Still, Dilip Kumar Roy writes about Indira Devi who became his disciple in 1949 in Pondicherry. Indira was such an intense seeker and bhakta, devotional singing sessions sent her into trances. She had visions of Mirabai singing in “a voice throbbing with “love’s yearning and pain,” recalled and wrote down these songs, and sang them. Commenting on this phenomenon, Sri Aurobindo (who was Roy’s guru) said, it was evident that “her consciousness and the consciousness of Mira are collaborating on some plane superconscient to the ordinary human mind.”

This book is a translation that must also be located within this Indic tradition, deriving its freedoms from it. It is a conversation with a mystic text, and must be appraised as one. Priya and Ravi utilize a range of methodologies from past and contemporary rubrics of translation, they are Indian and not only Indian, they are translators and poets besides, they work from Andal’s text and over and above, they translate, and they do more. Dear reader, may you be open to Andal in all sorts of ways.

– Mani Rao

INTRODUCTION

Andal and her Poetry

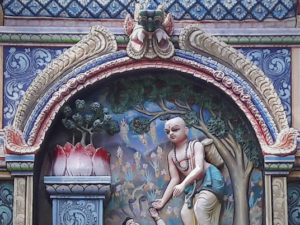

Andal (often referred to as Andal/Aandaal or Antal), the 9th-century mystic poet was elevated to goddess status within a few centuries of her birth in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. She was the only woman among the twelve medieval Vaishnava saints, known as the Alvars who ‘dived deep and drowned themselves in the love of god’ implying their complete devotion to Vishnu-Narayana, one of three main deities in the Hindu pantheon, often called Tirumal, The Sacred Dark One, in Tamil. Unlike other mystics Andal is unique in demanding to be taken as bride by Vishnu not as spirit but as a living maiden. Legend goes that when she was around sixteen she merged with her god at his temple in Srirangam, Tamil Nadu. Since then she has existed as myth and deity.

The Alvars, along with their counterparts, the Siva-worshipping Nayanmars, are the earliest proponents of the bhakti movement, a devotional and socially radical form of worship that emerged in medieval India which emphasized the quality of god as saulabhyam, or easily accessible to all. This celebration of personal prayer stressed composing in the poets’ mother tongue –as against Brahminic Sanskrit – some see it as striking against the caste system. Even as kings ‘re-converted’ to Hindu faith, the bhakti movement became a popular force instrumental in the retreat of wealthy Buddhist and Jain sects and, simultaneously, curtailed Brahmin monopoly on religion.

Andal’s first work – composed when she was about thirteen – the Tiruppavai (The Path to Krishna) is a lyrical description of the vows undertaken by young women to obtain a good husband; it is a song of congregational worship. In her second and last work, Nacciyar Tirumoli (The Sacred Songs of The Lady), Andal sings of her individual need for spiritual and sexual congress with her chosen god and of an abundant female desire explicitly sited in the body which too is holy. The Tiruppavai and the Nacciyar Tirumoli are included in the circa 11th century compilation Nalayira Divya Prabandham (Four Thousand Divine Compositions) that Tamil Srivaishanvas consider on par with the Sanskrit Vedas. The compilation’s literal translation is ‘Four’ (nali) ‘Thousand’ (aayiram) ‘Divine’ (divya) ‘affection’ (pra) ‘bonding’ (bandham) again is indicative of the Alwars’ intimacy of address to Vishnu-Narayana.

Andal calls to Vishnu, The Pervader, the cohesive principle of sattva, supreme illumination. The Brhad-devata (2.69.[213]) suggests his name may originate in the Sanskrit root vis which means to spread, to enter and to surround. “Having created the universe, he entered it” states the Taittiriya Upanishad (1.2.6. [274]). In Vaishnava theology, Vishnu is the Self in all of life and manifests endlessly in the world of forms and orders of creation, “just as from an inexhaustible lake thousands of streams flow on all sides” to guide and protect creation. Vishnu is prayed to as Hari, Remover of Sorrow and Illusions which is especially poignant in Andal’s case as she beseeches him time and again to accept and to save her. She addresses him variously: as Narayana (who moves on causal waters on the serpent Seshnaga), as Narayana Nampi (Universal Abode), Tirumal or Mal (The Dark One of Tamil theology) and through seven of his ten prominent avatars. But most often she addresses him as Krishna, divine child and lover.

Andal (often referred to as Andal/Aandaal or Antal), the 9th-century mystic poet was elevated to goddess status within a few centuries of her birth in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. She was the only woman among the twelve medieval Vaishnava saints, known as the Alvars who ‘dived deep and drowned themselves in the love of god’ implying their complete devotion to Vishnu-Narayana, one of three main deities in the Hindu pantheon, often called Tirumal, The Sacred Dark One, in Tamil.

Each of Andal’s pasurams (songs) is drenched in the way the sacred is embedded in every material that constitutes ephemeral life; at the same time she summons timeless grace, arul, to illumine her. Her work calls to question all markers of identity and boundaries as she passionately sings for bliss to enter her body and spirit. When we receive Andal, we must keep her youthfulness in mind. She conflates extreme violence with swooning surrender; splices the desires of the sexual body with visions of cosmic temporality. Yet we refrain from applying the term ‘transgressive’ to Andal as it suggests a deliberate breaking of rules. It appears she did not bother with any social conventions or rules at all – except those of poetry.

From Saint-Poet to Goddess and Teen Icon

Andal’s first work – composed when she was about thirteen – the Tiruppavai (The Path to Krishna) is a lyrical description of the vows undertaken by young women to obtain a good husband; it is a song of congregational worship. In her second and last work, Nacciyar Tirumoli (The Sacred Songs of The Lady), Andal sings of her individual need for spiritual and sexual congress with her chosen god and of an abundant female desire explicitly sited in the body which too is holy. Andal eventually would become a teenage saint-poet and then a goddess, when she became Vishnu’s consort, famously rejecting any marriage to a mortal man, considering herself betrothed to the divine.

Performative interpretations of Andal’s life of an all-surrendering love and passionate piety are enacted in Chennai during the annual music and dance festival as ‘high’ art, as also in films and popular TV dramas. Dingy roadside photo studios exhibit saturated images of girls in their coming-of-age ceremony dressed as Andal in vibrant silk saris, flower garlanded, hair dressed in a small bun on the right and then left to cascade. (The girls are also photographed variably as faux geishas, in salvar-kameez ‘suits’, as Bollywood starlets in jeans and spangling tops etc, thereby co-opting every current image of desirability. The Andal iconographic image, however, is a constant.) Perhaps the photographs imply that each girl is a fit bride for a god or perhaps they are shaded with upper caste aspirations, but it seems possible that there is a more powerful and unfathomed cultural imagination at work 13 centuries after Andal’s brief life.

Andal’s first work – composed when she was about thirteen – the Tiruppavai (The Path to Krishna) is a lyrical description of the vows undertaken by young women to obtain a good husband; it is a song of congregational worship. In her second and last work, Nacciyar Tirumoli (The Sacred Songs of The Lady), Andal sings of her individual need for spiritual and sexual congress with her chosen god and of an abundant female desire explicitly sited in the body which too is holy.

Andal’s first work, Tiruppavai (The Path to Krishna) is famed in Southern India, especially Tamil Nadu and sung by devotees during the sacred month of Markali. It is a lyrical and bhakti-filled description of vows undertaken by young women to obtain a good husband and is a song of congregational worship. However, in the later Nacciyar Tirumoli (The Sacred Songs of the Lady), Andal sings of her individual need for sexual congress with her chosen god. Except for Hymn Six – which elucidates her dreams of the marriage rituals and is sung at weddings even today – the other 13 hymns are not as often heard, perhaps because they speak of an abundant female desire explicitly sited in the body. Similar to the Gnostic texts which were omitted from what is commonly referred to as the Judeo-Christian Bible for their more overt sexual symbolism and heterodoxy which verged on the heretical, many of Andal’s hymns from the Nacciyar Tirumoli are considered by many (though not by us) to be ‘transgressive’.

Prismatic Soundings

We, the two translators of this project, are poets ourselves and so approach the translation with neither a historiographical nor theological approach, but rather a poetic one that sees her utterances as songs that need an innovative approach in order to sing fully in English. Priya grew up hearing Andal’s collection of hymns sung at weddings and festivals. For decades, the holy-poet-become-goddess hovered in her imagination like a cloud over the sea, nebulous yet lit on the horizon of the liminal, until one day she decided the goddess must land on the shore of her first language: English. At this time she met Ravi Shankar, the Indian American poet and professor, who shared her passion for Tamil literature and Andal in particular.

That’s how the two of us became collaborators and in working together, we realized that a new approach was necessary if we were to do justice to the richness and spiritual intensity of these poems. Our intention is to make the poems come alive in English and so we dispensed with attempting a literal translation, verging instead into a polyphonous mode of capturing the multiplicity inherent in Andal’s songs by experimenting with form and sometimes including multiple versions of the same poem, as well as more collaborative translations. We spoke about our aspirations for this project to the elder of the two scholar-poets whom we consulted for help with the manuscript, octogenarian S.V. Seshadri, who helped us understand the complexity of Tamil Sangam era (2 BCE–2 CE) poetics in which Andal composed.

Andal’s first work, Tiruppavai (The Path to Krishna) is famed in Southern India, especially Tamil Nadu and sung by devotees during the sacred month of Markali. It is a lyrical and bhakti-filled description of vows undertaken by young women to obtain a good husband and is a song of congregational worship.

To provide a sense of the difficulty in translating Old Tamil, consider the following saying, poem and verse which present conundrums because of specific poetic codes and suggested ‘unmarked’ meanings compressed in each.

- ‘If you wish to destroy a thorn tree, call for the axe.’

- When told of her lover’s interest in another woman she smiled and said:

Drunk

with honey

from the opening lotus

pond the bee flies

to its hive in the sandalwood grove.

- Bring me his garments translucent, yellow, shimmering

as pollen through which the dark majesty of his thighs rise

glistening and drape me in his scent

so my every pore is perfumed. Then shall I be content!

The meanings of these three distinctive utterances need contextual clues in order to be unravelled. The first is an epigram that translates as words of advice:

If you wish to kill your enemy, O king, do so quickly.

The second is a secular poem in which the woman implies that her lover enjoys her deeply, mutually as she enjoys him, that their love is sweet and as fresh and pure as blossoming lotuses whose roots are deep and entwined as their vows to each other and that he will carry her love with him as faithfully as a bee returning to its hive as he journeys to his home high on the hill far away, and that their love will remain fragrant and long lasting as sandalwood until he returns to her.

The third is a sacred hymn that follows the rules of Old Tamil prosody in making a similar, yet very different erotic demand. Unlike the earlier poem, its desires are not veiled in symbolic allegory. But while it seems direct, it could misdirect, for the desired ‘he’ is not a mortal, but the Protector of Universes, the dreaming Vishnu, who, in the starry cosmic ocean, rests on the cloud-coloured serpent Ananta, who represents ‘the eternity of time’s endless revolutions’. The speaker of this verse is Andal who was possibly fifteen at the time. This instance of sexual and devotional intensity is from the Nacciyar Tirumoli, Song Thirteen, verse one. In theological terms, the yellow silk is often interpreted as the veiling of the sacred wisdom of Narayana’s body. The speaker’s assumed extreme familiarity with god gives these poems their uncanny edge of heightened eroticism.

We have translated her bhakti or devotion-drenched hymns as The Autobiography of a Goddess. Alongside, we refer to the commentary of the 13th century scholar, Periyavaccan Pillai (Veritable Great Teacher) as he is the most revered early interpreter of these hymns.

We have translated her bhakti or devotion-drenched hymns as The Autobiography of a Goddess. Alongside, we refer to the commentary of the 13th century scholar, Periyavaccan Pillai (Veritable Great Teacher) as he is the most revered early interpreter of these hymns. We sought the guidance of Dr S. Raghuraman-Pulavar who has lectured and published extensively on the daunting Tholkaapiyameypaatiyal and is possibly the leading expert on cen or ancient Tamil grammar and poetics. He induced our passion for the holographic Tamil poetic form. At times we consulted Dr Prema Nandakumar, scholar of visistadvita philosophy (qualified non-dualism) to tease out inherent theological references. Also invaluable to us were Vidya Dehejia’s Andal and Her Path of Love: Poems of a Woman Saint from South India (State University of New York Press, 1990) and Archana Venkatesan’s The Secret Garland: Antal’s Tiruppavai and Nacciyar Tirumoli (Oxford University Press, 2010), the two most recent translations of Andal’s work into English, albeit in a very different form and manner than what we have attempted.

Drowning in love and language

As a bhakti saint, Andal composed in cen or Old Tamil. However, this implied following many of the rules codified in the Tolkaappiyam, the classical treatise on grammar and poetics. She did not follow its tinnai conventions that morph moods of love and evocative landscape into symbolic spaces of passion but worked with much of its other riddling complexities. Compounding the difficulty of translating this work, here is the catch: the ancient Tamils relied on the listeners and readers to ‘complete’ the poems by comprehending various allusions, including the invocation of myth and the utilization of complex poetic strategies. This is similar to postmodern reader-response theory that argues against the concept that meaning is embedded in the text, but rather believes that meaning only emerges dialectically between the relationship of text and reader.

A staggeringly exhaustive and codified compendium, the Tolkaappiyam recommends that both poet and reader immerse themselves in systems of poetics, grammar, versification, forms, metrical and rhythm schemes and possess an adequate mental thesaurus before attempting to read or write poetry. The level of sophistication of classical Tamil poetry is profound and there have been many manuals written on its prosodic elements, which included an elaboration of elullu, or the phoneme, acai, or the metreme, cir, or the metrical foot, talai, or the linkage, ali, or the line, and totai, or ornamentation. Sangam literature, written in classical Tamil, offers us poetic works with re-combinations of the above elements in extremely refined ways.

As a bhakti saint, Andal composed in cen or Old Tamil. However, this implied following many of the rules codified in the Tolkaappiyam, the classical treatise on grammar and poetics. She did not follow its tinnai conventions that morph moods of love and evocative landscape into symbolic spaces of passion but worked with much of its other riddling complexities.

For example, Andal’s Tiruppavai is written in eight-line stanzas in the koccakakalippa meter, or four metrical feet, whereas the Nacciyar Tirumoli employs five different meters in lines that range from four to eight feet. We have not attempted to mimic that complex meter in English, as it would be a virtual impossibility, as well as resultant in a stilted form of poetry. We have instead attempted to abide in her imagery and metaphor, and find a suitable form that reinforces and mirrors the ecstatic content of her songs, especially as relates to the traditions of Tamil love poetry.

Take this anonymous verse about amorous poetry which states:

Aagapaattuvaannam

mudindadu polmudiyadadi

aahum

Here’s a literal translation, compounded by the difficulty that Tamil morphology is akin to a mantra with a maraiporul, or a secret hidden meaning:

Love-poetry sounds/forms/presents

complete as if not complete

is like that

or, put another way:

Love poetry seems

completed

but isn’t.

The loop is only completed when the listener participates in the performance of the poem somatically and collectively, and that kind of participatory model of interpretation points to the thriving local literary culture that existed at that time. Translating this element of historicity for a contemporary audience now provides us the space and freedom to make multiple connections between lines and between verses, and productive misinterpretations notwithstanding, allows for the liberation of imagination in trying to bring to light the numerous flowing undercurrents and holographic affects that are taking place simultaneously. For this reason, we have developed a radical mode of translation meant to illuminate a wide spectrum of Andal’s spirit, rather than to slavishly hew to the letter of her work.

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of Zubaan Books. You can buy Andal: The Autobiography of a Goddess, here.

In the colonial period, the threat of the lecherous male gaze was used by the new patriarchy to restrict access to employment and public space for women, maintaining a patriarchal division of labour. Read how this process unfolded in our newest excerpt.

Saurav Kumar Rai

__

Was Lala Lajpat Rai's Hindu nationalism congruent with the principles of secularism? Explore our latest excerpt from Vanya Vaidehi Bhargav's fresh off-the-press book - Being Hindu, Being Indian: Lala Lajpat Rai's Ideas of Nation for more.

Vanya Vaidehi Bhargav

__

Popularly, we think that political cartoons question the powerful but what if this was not the case? What if political cartoons, replicated structures of the socially dominant? Read how in our new excerpt on political cartoons featuring Dr. Ambedkar.

Unnamati Syama Sundar

__

On Martyrs' day 2024, read the poet Sarojini Naidu's tribute to Gandhi given over All India Radio two days after his assassination.

Sarojini Naidu

__

On Republic Day, the Indian History Collective presents you, twenty-two illustrations from the first illustrated manuscript (1954) of our Constitution.

Indian History Collective

__

One of the key petitioners in the Ayodhya title dispute was Bhagwan Sri Ram Virajman. This petitioner was no mortal, but God Ram himself. How did Ram find his way from heaven to the Supreme Court of India to plead his case? Read further to find out.

Richard H Davis

__

Labelled "one of the shortest, happiest wars ever seen", the integration of the princely state of Hyderabad in 1948 was anything but that. Read about the truth behind the creation of an Indian Union, the fault lines left behind, and what they signify

Afsar Mohammad

__

How did Bengal get a large Muslim population? Was it conversion by ruling elites was there something deeper at play? Read Dr. Eaton's classic essay to find out.

Richard Eaton

__

An excerpt from Shailaija Paik's new book 'Vulgarity of Caste' that documents the pivotal role Tamasha (the popular art form) has played in reinforcing and producing caste dynamics in Marathi society.

Shailaja Paik

__

In 1942, two sub-districts in Bengal declared independence and set up a parallel government. The second part of our story brings you archival papers in the form of letters, newspaper reports, and judicial records documenting this remarkable movement.

Indian History Collective

__

In 1942, five years before India was independent, two sub-divisions in Bengal not only declared their independence— they also instituted a parallel government. The first in a new series.

Indian History Collective

__

In his own words, read Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi's views on the proselytising efforts taken on by the organisations such as Arya Samaj, Tabhligi Jamaat, and the Church Missionary Society of England.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

__

TIMELINE

-

2500 BC - Present

2500 BC - Present Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas -

2200 BC to 600 AD

2200 BC to 600 AD War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India -

400 BC to 1001 AD

400 BC to 1001 AD The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India -

600CE-1200CE

600CE-1200CE The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power -

c. 700 - 1400 AD

c. 700 - 1400 AD A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History -

c. 800 - 900 CE

c. 800 - 900 CE ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess -

1192

1192 Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India -

1200 - 1850

1200 - 1850 Temples, deities, and the law. -

c. 1500 - 1600 AD

c. 1500 - 1600 AD A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India -

1200-2020

1200-2020 Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra -

1530-1858

1530-1858 Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan -

1575

1575 Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court -

1579

1579 Padshah-i Islam -

1550-1800

1550-1800 Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal -

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ -

1553 - 1900

1553 - 1900 What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? -

1630-1680

1630-1680 Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? -

1630 -1680

1630 -1680 Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times -

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D.

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power -

1818 - Present

1818 - Present The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon -

1831

1831 The Derozians’ India -

1855

1855 Ayodhya 1855 -

1856

1856 “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib -

1857

1857 A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 -

1858 - 1976

1858 - 1976 Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow -

1883 - 1894

1883 - 1894 The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate -

1887

1887 The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar -

1893-1946

1893-1946 A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste -

1897

1897 Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy -

1913 - 1916 Modern Review

1913 - 1916 A Young Ambedkar in New York -

1916

1916 A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier -

1917

1917 On Nationalism, by Tagore -

1918 - 1919

1918 - 1919 What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? -

1920 - 1947

1920 - 1947 How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi -

1921

1921 Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) -

1921 - 2015

1921 - 2015 A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar -

1915-1921

1915-1921 The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore -

1924-1937

1924-1937 What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? -

1900-1950

1900-1950 Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society -

1925, 1926

1925, 1926 Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) -

1928

1928 Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? -

1930 Modern Review

1930 The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality -

1932

1932 Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi -

1933 - 1991

1933 - 1991 Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian -

1935

1935 A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address -

1865-1928

1865-1928 Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism -

1935 Modern Review

1935 The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge -

1936 Modern Review

1936 The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ -

1936

1936 Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 -

1936 Modern Review

1936 The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament -

1936

1936 Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 -

1936

1936 A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature -

1936 Modern Review

1936 The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election -

1937 Modern Review

1937 The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati -

1938

1938 Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) -

1942 Modern Review

1942 IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) -

1942-1945

1942-1945 IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) -

1946

1946 Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 -

1946

1946 An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose -

1946 – 1947

1946 – 1947 “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly -

1946-1947

1946-1947 VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India -

1916 - 1947

1916 - 1947 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read -

1947-1951

1947-1951 Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us -

1948

1948 “My Father, Do Not Rest” -

1940-1960

1940-1960 Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad -

1948

1948 The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation -

1949

1949 Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ -

1950

1950 Illustrations from the constitution -

1951

1951 How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed -

1967

1967 Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari -

1970

1970 R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography -

1973 - 1993

1973 - 1993 Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh -

1975

1975 The Emergency Package: Shadow Power -

1975

1975 The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control -

1977 – 2011

1977 – 2011 Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal -

1984

1984 Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star -

1916-2004

1916-2004 Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” -

2008

2008 Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? -

2006 - 2009

2006 - 2009 Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee -

2020

2020 The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read -

2021

2021 Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives