ARCHIVE

Mark Tully reads ‘Operation Blue Star’, a chapter from his book ‘Amritsar: Mrs Gandhi’s Final Battle’ for the Indian History Collective.

OPERATION BLUE STAR

At seven o’clock on the evening of 5th June, tanks of the 16th Cavalry Regiment of the Indian army started moving up to the Golden Temple complex. They passed the Jallianwala Bagh, the enclosed garden where General Dyer massacred nearly 400 people. That massacre dealt a mortal blow to Britain’s hopes of continuing to rule India and was one of the most powerful inspirations of the freedom movement. When Mrs. Gandhi was told that Operation Blue Star had started, she must have wondered whether it would provide the decisive inspiration for the Sikh independence movement, a movement which at that time had very little support outside Bhindranwale’s entourage and small groups of Sikhs living in Britain, Canada and the United States.

Major-General Brar had addressed his men before he ordered them to enter the Golden Temple complex. He was commanding a mixed bag of troops, representative of the widespread recruiting pattern of the modern Indian army, which has broken with the British tradition of limiting recruitment to certain ‘martial castes’. There were Dogras and Kumaonis from the foothills of the Himalayas, India’s northern border. There were Rajputs, the desert warriors from Rajasthan. There were Madrasis from Tamil Nadu, one of the most southern states. There were Biharis from the tribes of central India, and there were some Sikhs. Major- General Brar told his men that entering the Golden Temple complex was a ‘last resort’, that they had to do it to ‘stop the country being held to ransom any longer.’

Bhindrawale was identified as ‘the enemy’, and the attacking force was told that he had ‘seized control of the Temple’. Every man was told that he must not fire at either of the shrines inside the Temple complex, the Golden Temple and the Akal Takht, without direct orders.It was almost thirty years to the day since Brar had joined the Maratha Light Infantry as a lieutenant. He had fought in the Bangladesh war under Lieutenant-General Jagjit Singh Aurora, the Sikh general who was to be one of the most outspoken critics of Operation Blue Star. Brar had been decorated for gallantry. He had also held an important staff post in the Defence Ministry, and was now commanding one of the crack Infantry Divisions, the 9th. Brar was a stylish soldier with curly grey hair emerging from under the beret he wore pulled well down over his right ear.

Brar’s superior officer was Lt-General Krishnaswamy Sunderji, the General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Western Command. He had joined the Mahar Regiment, a new regiment designed to bring a ‘non-martial’ caste into the army. During the 1965 war with Pakistan, Sunderji commanded a battalion and during the Bangladesh war he was a brigadier on the staff in the Eastern Sector. Sunderji had also commanded the College of Combat at Mhow, one of the most important training institutes of the Indian army. He had a reputation as a strategist, and was in the running for the number one job, the Chief of the Army Staff.

Bhindrawale was identified as ‘the enemy’, and the attacking force was told that he had ‘seized control of the Temple’. Every man was told that he must not fire at either of the shrines inside the Temple complex, the Golden Temple and the Akal Takht, without direct orders.

Sunderji asked his Chief Staff Officer, Lt-General Ranjit Singh Dayal, to draw up the plans for Operation Blue Star. Dayal, like Brar, was a Sikh, but he had not shaved his beard or cut his hair, and still wore a turban. Dayal was also an infantry soldier, having served in the 1st Battalion, the Parachute Regiment, which was to spearhead the attack on the Golden Temple complex. During the 1965 war with Pakistan, Dayal became a legend by capturing a pass which had previously been thought to be impregnable, and blocking off one of the most important routes from Pakistan- controlled Kashmir into the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. A frontal assault was impossible and so Lt-General Daval climbed up the mountain towering over the Haji Pir Pass and came down on top of the Pakistanis. He described the operation himself:

I then sought permission of my commanding officer to capture the Haji Pir Pass. The permission was granted, and then began the march forward. The enemy fired from two directions. I sent one platoon to silence the enemy guns. I and the rest of my men continued to advance and reached Hyderabad Nullah by 7 p.m.

From then on it was bad going. The pass from there was a 4,ooo-foot-steep climb. It was raining heavily. The ground was slushy. I left the beaten track and took another route. In fact, it was not a route at all. It was a steep climb. Despite the heavy odds, we reached the road leading to the pass at 4.30 a.m. on August 28. I decided to give my men carrying guns and batteries the much needed rest. After two hours, we again started climbing and at 8 a.m. we reached a bund [embankment] near the pass.

Leaving some men there to keep the enemy engaged, along with the rest of the party, I climbed another hill feature and from there rolled down and stormed the enemy position at the pass. The enemy fled in confusion leaving their guns. By 10.30 a.m. we were in complete control of the pass.

When he briefed the press after Operation Blue Star, Lt-General Sunderji described the orders the government had given him:

![Snipers taking aim from buildings, overlooking the streets leading to the Temple. [Credits: 47roots.com]](http://indianhistorycollective.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/47roots.jpeg)

Snipers taking aim from buildings, overlooking the streets leading to the Temple. [Credit: 47roots.com]

Dayal also gave an example of the piety of Indian army soldiers from his own experience.

Lieutenant-General Sunderji also stressed the religious aspect of the operation. He said, ‘We went inside with humility in our hearts and prayers on our lips. We in the army hold all places of religion in equal reverence.’

Lieutenant-General Dayal told the press, ‘The principle of minimum force was to be applied throughout.’ He described Operation Blue Star as ‘a typical infantry operation.’ Dayal also stressed that all troops were ordered not to damage the Golden Temple. He was a deeply religious man who had been coming to the Golden Temple to pray since he was fourteen years old. The Lieutenant-General told the press that he never doubted that his men would obey their orders not to damage the shrine.

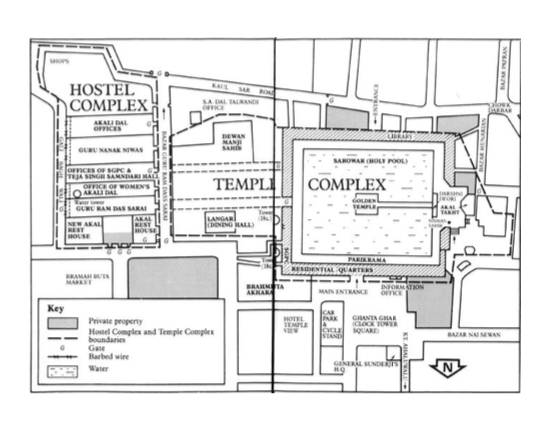

To achieve his objectives of ‘flushing out’ the extremists from the Golden Temple complex, doing minimum damage to the shrines, and preventing a battle breaking out in the hostel complex, Dayal drew up a twofold plan. The essence of the plan was to separate the hostel complex from the Temple complex, so that the hostels could be evacuated without becoming involved in the main battle. To achieve his prime objective of getting Bhindranwale out of the Temple complex, Dayal had planned commando operations. The commandos were to be supported by infantry. Tanks were only to be used as platforms for machine-guns to neutralise fire on troops approaching the Golden Temple complex, and to cover the Temple exits in case anyone tried to escape. Armoured personnel carriers were to be positioned on the road separating the hostels from the Temple complex to keep the two potential battle fields apart.

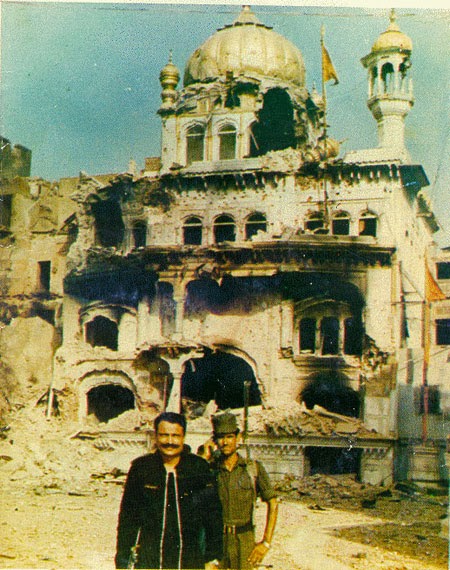

The three Generals succeeded in achieving only one of their objectives. The Golden Temple complex was cleared, but to say that Bhindranwale was flushed out would be, to put it mildly, an understatement. He was blasted out of the Akal Takht by the 105 mm. main armament of Indian Vijayanta (Victory) tanks. In the process much of the Akal Takht, the shrine which according to the original orders was to suffer ‘as little as possible damage’, was reduced to rubble. At the start of the operation troops had even been forbidden to use automatic weapons against the Akal Takht. The evacuation of the hostel complex was completed but not without heavy civilian casualties.

Sketch map of the Golden Temple and hostel complex. [Credits: Amritsar: Mrs. Gandhi’s Last Battle]

The essence of the plan was to separate the hostel complex from the Temple complex, so that the hostels could be evacuated without becoming involved in the main battle. To achieve his prime objective of getting Bhindranwale out of the Temple complex, Dayal had planned commando operations. The commandos were to be supported by infantry. Tanks were only to be used as platforms for machine-guns to neutralise fire on troops approaching the Golden Temple complex, and to cover the Temple exits in case anyone tried to escape.

Major-General Brar said that he ordered artillery to blast off the tops of the three towers. However he decided not to capture the seventeen houses because he did not have ‘the resources to do so’. Firing continued from these houses for days after the Golden Temple complex had been captured. The use of artillery in an area as crowded and densely populated as the old city of Amritsar proved, not surprisingly, to be very costly. Artillery is an ‘area weapon’, used to kill and suppress fire over a wide area, and is not commonly used against special targets. Severe damage was caused to several bazaars, but Brar had to secure the posts commanding the entrance to the Temple and the inside of the Temple itself before he could send his soldiers into the historic headquarters of the Sikh religion.

It was only when he was convinced the approaches to the Temple complex were clear that Brar ordered the tanks to move into the square in front of the northern entrance to the Golden Temple, known as the ghantaghar, or clock tower entrance. One of the tank commanders said, ‘As soon as I turned right from Jallianwala Bagh I heard the tik-tik sound of shells landing on my tank. Over the headphones I got the order to neutralise the fire.’ According to the Lieutenant of the 16th Cavalry, there were four tanks and three armoured cars. He said that Shahbeg Singh appeared to be monitoring their movements because, once the armour was in position, firing from the walls of the Temple stopped. The Lieutenant reported back to his commanding officer that the firing had been neutralised. But as soon as the assault on the Temple started it became clear that Shahbeg Singh’s firepower was far from neutralised.

Major-General Shabeg Singh, who was dismissed from the army on corruption charges one day before his retirement. A civil court later acquitted him.

Meanwhile in the narrow alley behind the Akal Takht, those paramilitary commandos who had trained on the model of the Golden Temple complex were trying to get into Bhindranwale’s fortress. This operation was a dismal failure. Some commandos did get on to the roof of the shrine, but they were caught in the crossfire and had to withdraw. For some reason this part of the operation was not mentioned at all by the Generals when they briefed the press after it was all over.

It was between ten and ten-thirty in the evening that Major-General Brar decided he must launch a frontal attack on the Akal Takht. Commandos from the 1st Battalion, the Parachute Regiment, wearing black denims, were ordered to run down the steps under the clock tower on to the parikrama, or pavement, turn right and move as quickly as they could round the edge of the sacred tank to the Akal Takht. But as the paratroopers entered the main gateway of the Temple they were mown down. Most of the casualties were caused by Sikhs with light machine-guns who were hiding on either side of the steps leading down to the parikrama. The few commandos who did get down the steps were driven back by a barrage of fire from the buildings on the south side of the sacred pool. In the control room, in a house on the opposite side of the clock-tower square, Major- General Brar was waiting anxiously with his two superior officers to hear that the commandos had established positions inside the complex. When no report came through he was heard over the command network saying, ‘You bastards, why don’t you go in.’

However he decided not to capture the seventeen houses because he did not have ‘the resources to do so’. Firing continued from these houses for days after the Golden Temple complex had been captured. The use of artillery in an area as crowded and densely populated as the old city of Amritsar proved, not surprisingly, to be very costly. Artillery is an ‘area weapon,’ used to kill and suppress fire over a wide area, and is not commonly used against special targets.

The few commandos who survived regrouped in the square outside the Temple, and reported back to Major- General Brar. He reinforced them and ordered them to make another attempt to go in. The commandos were to be followed by the 10th Battalion of the Guards commanded by a Muslim, Lieutenant-Colonel Israr Khan. This battalion had Sikh soldiers in its ranks. The second commando attack managed to neutralise the machine-gun posts on either side of the steps and get down on to the parikrama. They were followed by the Guards who came under withering fire and were not able to make any progress towards their objective, the Akal Takht. Lt-Colonel Israr Khan radioed for permission to fire back at the buildings on the other side of the tank. That would have meant that the Golden Temple itself, which is in the middle of the tank, would have been in the line of fire. Brar refused permission. He still believed it would be possible to achieve all his objectives, including preserving the Golden Temple and the Akal Takht intact. But then he started to get messages from the commander of the Guards reporting heavy casualties. They had suffered almost 20 per cent casualties without managing to turn the corner of the parikrama to the western side of the complex where the Akal Takht is situated. The Guards were not only being fired at from the northern and western sides. Sikhs would also suddenly appear from man-holes in the parikrama the Guards were fighting from, let off a burst of machine-gun fire or throw lethal grenades, made in the complex itself, and disappear into the passages which run under the Temple. These machine-gunners had been taught to fire at knee-level because Major-General Shahbeg Singh expected the army to crawl towards its objective. But the Guards and commandos were not crawling, and so many of them received severe leg injuries.

Brar then decided on a change of plan. As he said after the battle, ‘I realised that it was difficult for this battalion to progress operations any further and there was no point in them remaining at the ground-floor level. Unless you got on to the first floor and to the rooftop, and got it to control the situation, you would continue suffering casualties. So the task given to them was, under all circumstances, to get a lodgement in spite of all the casualties they had suffered and I must give full credit to the battalion commander, a very dashing young soldier, Lt-Colonel Israr Khan, who rallied his boys together and worked his way up and did succeed in getting an allotment in this particular area.’ That allotment enabled the Guards to neutralise some of the positions on the south side of the tank, but they were still hampered by the order not to fire in any direction which would endanger either of the historic shrines.

The second commando attack managed to neutralise the machine-gun posts on either side of the steps and get down on to the parikrama. They were followed by the Guards who came under withering fire and were not able to make any progress towards their objective, the Akal Takht. Lt-Colonel Israr Khan radioed for permission to fire back at the buildings on the other side of the tank. That would have meant that the Golden Temple itself, which is in the middle of the tank, would have been in the line of fire. Brar refused permission

In spite of the very heavy firing, some of the commandos did manage to get round that corner of the parikrama and make their way to the courtyard in front of the Akal Takht. But they fought their way into a lethal trap. The Akal Takht itself was heavily fortified; there were sandbag and brick gun emplacements in its windows and arches, and holes had been made in its sacred marble to provide firing positions. On either side of the shrine are buildings which overlook the courtyard. They had been fortified too, as had the Toshakhana or Temple Treasury opposite the Akal Takht and the houses which overlooked the building from behind. So when the commandos got into that courtyard, bullets rained down on them from all sides. They were driven back suffering 30 per cent casualties. The courtyard in front of the Akal Takht had been turned, in Major-General Brar’s words, ‘into a killing ground’. To make matters worse, there was no sign of the Madrasis who were meant to be entering the Golden Temple complex from the southern side to form the other half of a pincer movement on the Akal Takht. When it became clear that the Madrasis had either got bogged down or lost in the narrow alleys, Brar asked his superiors for permission to use troops from another Division, the 15th. The infantry from his own division was fully deployed. The Guards were inside the Temple on the northern side, the Madrasis were trying to make their way to the eastern entrance, the Kumaons were clearing the hostel complex, and the Bihars had thrown a cordon round the Temple. Their main responsibility was to ensure that neither Bhindranwale nor any of his followers escaped.

Sunderji and Dayal agreed to reinforcing the operation and so two companies of the 7th Garhwal Rifles were put under Brar’s command. The Garhwals also come from the foothills of the Himalayas in the state of Uttar Pradesh. Brar ordered them to enter the Temple from the southern side and try to relieve the pressure on the Guards and the commandos on the northern side. As soon as they entered the southern gate they came under heavy fire. An officer of the Garhwals said, ‘They seemed to be firing on us from everywhere. It was impossible to know where to fire back.’ But the Garhwals did manage to establish a position on the roof of the Temple library. Their commanding officer reported this to his Brigadier, A.K. Dewan.

Dewan was very much a soldier’s soldier, always wanting to be in the thick of it. His nickname was, surprisingly, Chicken. Apparently he was called Chicken when he was an officer cadet because he had a very long and thin neck. The Brigadier should have left the fighting inside the complex to the battalion officers, but he could not resist the temptation to join in himself. The Lieutenant-Colonel commanding the Garhwals tried to dissuade him, saying that his men were under very heavy fire, but this was an added attraction for Dewan. When he got into the Temple he reported to Major- General Brar on the wireless. Brar, whose temper was wearing a little thin by this time, could be heard over the whole network shouting at Dewan: ‘What the hell are you doing in there? I am in command of this operation. You don’t move without my orders.’

The Akal Takht itself was heavily fortified; there were sandbag and brick gun emplacements in its windows and arches, and holes had been made in its sacred marble to provide firing positions. On either side of the shrine are buildings which overlook the courtyard. They had been fortified too, as had the Toshakhana or Temple Treasury opposite the Akal Takht and the houses which overlooked the building from behind. So when the commandos got into that courtyard, bullets rained down on them from all sides.

Then Brar calmed down and asked Dewan to stay inside and let him have a sitrep as soon as possible. Dewan realised that it was very unlikely that the Guards and the commandos would be able to achieve their objective. But he did reckon that his position on the southern side was fairly secure and that if he could reinforce it, he might be able to storm the shrine. When he reported this back to Brar he was given permission to call up two companies of the 15th Kumaons. By this time the operation had been in progress for about two hours and Brar was nowhere near achieving his objective. His short, sharp commando operation had got bogged down; so he decided to allow Dewan to fight his own battle inside the Temple complex.

Dewan made repeated attempts to storm the Akal Takht but each time the Kumaons or Garhwals turned the corner of the parikrama and ran into the courtyard in front of the Akal Takht, they came under withering fire and had to retreat. Dewan himself was striding up and down the southern side of the parikrama encouraging his men. But their task was impossible. Although both the northern and southern sides of the parikrama were by now in the control of the army, they had not been able to make any impression on the main fortress and the defences surrounding it, and the four companies had suffered 137 casualties. Of course they were still hampered by the order not to fire in any direction which would endanger the Golden Temple.

![General Kuldip Singh Brar, General Krishnaswamy Sundarji and General AS Vaidya at the Golden Temple after Operation Bluestar. [Credit: Gateway to Sikhism Foundation]](http://indianhistorycollective.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/3genmain.jpeg)

General Kuldip Singh Brar, General Krishnaswamy Sundarji and General AS Vaidya at the Golden Temple after Operation Blue Star. [Credit: Gateway to Sikhism Foundation]

There was no way anyone could get into that fortress without taking out its defences first. Dewan’s repeated charges were as futile as the charge of the Light Brigade, and he now realised it. He got on the wireless and told Brar that he would have to call up tanks to bombard the Akal Takht. He said, ‘I can’t afford to lose any more men. I can’t accept defeat.’ Brar later told the press his version of what happened next:

Although both the northern and southern sides of the parikrama were by now in the control of the army, they had not been able to make any impression on the main fortress and the defences surrounding it, and the four companies had suffered 137 casualties. Of course they were still hampered by the order not to fire in any direction which would endanger the Golden Temple.

Sunderji’s reaction was not instantaneous. He first contacted Delhi where a special operations room had been set up to keep track of the battle. The Deputy Defence Minister, K.P. Singh Deo, a former army officer himself, was in charge, assisted by Rajiv Gandhi’s most trusted aide, Arun Singh, who, although not a practising Sikh, came from one of the Punjab royal families. The army and the government were now faced with a dilemma. Sunderji had always insisted that the operation must be completed by daybreak, otherwise his men inside the Temple would be sitting ducks for Bhindranwale’s snipers. There could be no question of withdrawing and trying again the next night, because the news that Bhindranwale and Shahbeg Singh had forced the Indian army to withdraw would certainly leak out somehow. That would have disastrous consequences in the villages of Punjab and among Sikhs in the army. The only answer seemed to be tanks. They were the only equipment with the firepower and the accuracy to blast a way into Bhindranwale’s fortress. But tanks meant that the army would fail in one of its tasks – the preservation of the Akal Takht. They also meant the horrifying prospect of one mistake by a gunner seriously damaging the Golden Temple itself. In the end Delhi agreed that the tanks should be used and a message was sent back to Lieutenant-General Sunderji, nearly two hours after Chicken Dewan had asked for them.

Vijayanta Tanks used in the operation.

In the meanwhile Major-General Brar had made one more effort to get his men into the Akal Takht. He called up a Skot OT64 armoured personnel carrier. Tanks had to break down the steps leading to the parikrama from the hostel side so that the eight-wheeled, Polish-built APC could get in. The aim was to drive the APC right up to the Akal Takht so that the men from the mechanised infantry, one of the newest units of the Indian army, could get into the fortress under the cover of its wall. But as the armoured personnel carrier approached the Akal Takht it came under fire from two Chinese-made, rocket-propelled grenade launchers. One of the grenades found its target and the armoured personnel carrier was knocked out. The Captain commanding the platoon was wounded.

This forced the Generals to rethink their strategy once again. They had no intelligence reports of Shahbeg Singh having armour-piercing weapons at his disposal. Even the tanks, which had by now made their way on to the parikrama to await government clearance to open fire, were now at risk, although the maximum armour of the tanks was more than twice as thick as the APC’s. The tanks had been trying to blind the marksmen in Bhindranwale’s fortress with their searchlights. As soon as Brar realised that the enemy had armour-piercing weapons, he ordered the tank commanders to switch off their searchlights. The tanks had ploughed up the parikrama, each of whose marble slabs was inscribed with the name of the devotee who had donated it to the Temple.

Sunderji had always insisted that the operation must be completed by daybreak, otherwise his men inside the Temple would be sitting ducks for Bhindranwale’s snipers. There could be no question of withdrawing and trying again the next night, because the news that Bhindranwale and Shahbeg Singh had forced the Indian army to withdraw would certainly leak out somehow…The only answer seemed to be tanks. They were the only equipment with the firepower and the accuracy to blast a way into Bhindranwale’s fortress.

The Vijayanta was the army’s main battle tank, being an Indian-built version of the Vickers 38-ton tank. When the orders came, they opened up with their main armament. Photographs of the shattered shrine indicate quite clearly that the Vijayantas 105 mm. main armaments pumped high- explosive squash-head shells into the Akal Takht. Those shells were designed for use against ‘hard targets’ like armour and fortifications. When the shells hit their targets, their heads spread or ‘squash’ on to the hard surface. Their fuses are arranged to allow a short delay between the impact and the shells igniting, so that a shock-wave passes through the target and a heavy slab of armour or masonry is forced away from the inside of the armoured vehicle or fortification. Lieutenant- General Jagjit Singh Aurora, who studied the front of the Akal Takht before it was repaired, reckoned that as many as eighty of these lethal shells could have been fired into the shrine. The advantage of a tank’s main armament is that it fires with pinpoint accuracy. Indian army officers talk of the Vijayanta’s ability to post shells through letter-boxes.

The effect of this barrage on the Akal Takht was devastating. The whole of the front of the sacred shrine was destroyed, leaving hardly a pillar standing. Fires broke out in many of the different rooms blackening the marble walls and wrecking the delicate decorations dating from Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s time. They included marble inlay, plaster and mirror work, and filigree partitions. The gold-plated dome of the Akal Takht was also badly damaged by artillery fire. At one stage during the night Major-General Brar had ordered his Colonel (Administration) to mount a 3.7-inch Howell gun on to the roof of a building behind the shrine and fire at the dome in an attempt to frighten the Sikhs into surrender. Brar explained to his Colonel, ‘Maybe the noise and the sting will have its effect.’

Damaged front facade of the Akal Takht after the operation.

The artillery did not scare Bhindranwale’s men; but the tank barrage was a different matter. The effect it must have had is impossible to imagine. As shockwave after shockwave rocked the building, the gallant, if misguided, defenders must have feared it was going to come down on top of them. Deafened by the explosions, they were driven to the back of the building by the flames and falling masonry. The deadly machine-gun fire which had been raining down on the army stopped.

Still sporadic resistance continued from some of the buildings overlooking the courtyard in front of the Akal Takht. By now it was light and Brar decided it was too dangerous to make the final assault necessary to re-establish control over the shrine from which Bhindranwale and Shahbeg Singh had withstood the Indian infantry attack. So Brigadier Dewan was ordered not to follow up the tank attack until darkness fell again. The three Generals at the command post knew that they had knocked out Bhindranwale’s fortress, but they still faced the agonising possibility that the Sant himself might have escaped.

The effect of this barrage on the Akal Takht was devastating. The whole of the front of the sacred shrine was destroyed, leaving hardly a pillar standing. Fires broke out in many of the different rooms blackening the marble walls and wrecking the delicate decorations dating from Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s time. They included marble inlay, plaster and mirror work, and filigree partitions. The gold-plated dome of the Akal Takht was also badly damaged by artillery fire.

After the battle Brar told the press that only one tank had been driven on to the parikrama, and that it had only fired its secondary armament, a 7.62 mm. machine-gun. But the damage to the Akal Takht tells a different story. There was no machine-gun which could have brought down so much masonry, and the shell marks were clearly those of high- explosive squash-heads. As for the number of tanks involved, other officers Satish Jacob talked to said that as many as six were brought into the complex. As one Vijayanta only carries forty-four rounds of main armament ammunition, it is certain that more than one was used. It also seems likely that the gunners fired from more than one position because the Golden Temple itself was in their arc of fire, standing as it does in the middle of the sacred tank.

The battle for the Akal Takht was not the only one raging that night. Across the road running along the eastern side of the Golden Temple complex, another battalion of the Kumaon Regiment was involved in the second operation that Lieutenant-General Sunderji had been ordered to carry out. He had been told by the government to ‘prevent internecine fighting between the two major groups lodged in the Temple and the hostel complexes, the one of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale and the second of Mr Longowal and his followers’. To prevent the two groups fighting each other, the Generals had decided that the hostel complex housing Longowal and his men must be cleared at the same time as the Golden Temple.

The first problem was to get into the complex. The iron gates at the top of the public road between the hostels and the Temple had been barred. A tank had to break them down. Armoured cars were then positioned along that road to separate the two battlefields, and the 9th Kumaons moved in. They came under fire from the roofs on both sides of the road but unlike their colleagues inside the Temple complex, they managed to fight their way into the buildings they had been ordered to clear.

The Teja Singh Samundri Hall, Amritsar, which preserves the bullet marks from Operation Blue Star.

Most of the terrified pilgrims, supporters of the Akali Morcha, and of course the two members of the Akali Trinity with their staff were huddled together in two buildings. They were without water because the water tower had been destroyed during the preliminary operations, and without electricity. Longowal, Tohra, and some of their senior colleagues were in Tohra’s office on the ground floor of the Teja Singh Samundari Hall. The SGPC Secretary, Bhan Singh, later described the situation in that building:

The army entered the Teja Singh Samundari Hall at about one o’clock in the morning. According to one officer, Tohra and Longowal were in their vests and underpants. The army says they surrendered. Bhan Singh did not accept that statement. He said, ‘We did not give ourselves up. The army forced its way in and took us prisoners.’ That is really just a matter of semantics. What is absolutely clear is that Longowal and Tohra made no attempt to resist the army.

Across the road running along the eastern side of the Golden Temple complex, another battalion of the Kumaon Regiment was involved in the second operation that Lieutenant-General Sunderji had been ordered to carry out. He had been told by the government to ‘prevent internecine fighting between the two major groups lodged in the Temple and the hostel complexes, the one of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale and the second of Mr Longowal and his followers’.

The Akali leaders were kept inside one of their offices. The rest of the people in the building were ordered to come out and sit in a courtyard of the Guru Ram Das Hostel. According to Bhan Singh, there were about 250 of them. Some terrorists, seeing the people pouring out of the offices and surrendering, threw a grenade at them. Bhan Singh explained what happened.

The White Paper admitted that seventy people including thirty women and five children died in that incident; but the government put all the blame on the terrorists, saying nothing about the army firing.

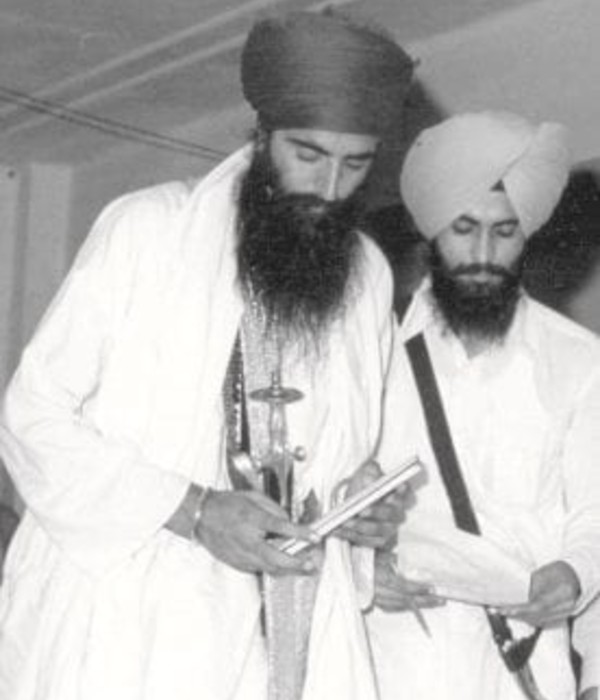

Harminder Singh Sandhu, Bhindrawale’s interpreter and close associate, General Secretary of All India Sikh Students’ Federation. [Credit: sikh24.com]

Bhan Singh also told the journalist and historian, Khushwant Singh, that the army did shoot some of the young men they had brought out from the Teja Singh Samundari Hall. He said:

But not everyone the army rounded up in the Teja Singh Samundari Hall was innocent. Among those who surrendered was Bhindranwale’s talkative young interpreter, Harminder Singh Sandhu, who was also the General Secretary of the All India Sikh Students Federation. When I had seen him on the day before the army action started, he had boasted, ‘Every one of Santji’s followers will lay down their lives to save the Golden Temple.’ But when the time came Harminder Singh Sandhu surrendered meekly.

Bhan Singh also told the journalist and historian, Khushwant Singh, that the army did shoot some of the young men they had brought out from the Teja Singh Samundari Hall. He said: “I saw about thirty-five or thirty-six Sikhs lined up with their hands raised above their heads. And the major was about to order them to be shot. When I asked him for medical help, he got into a rage, tore my turban off my head, and ordered his men to shoot me.”

Inside the Guru Ram Das Hostel, where the rooms were crowded with pilgrims, conditions were reminiscent of the Black Hole of Calcutta. The school teacher Ranbir Kaur and her husband had locked themselves into Room 141 with the twelve children they were looking after. Ranbir Kaur said:

The Kumaon Regiment also entered the Hostel at about one o’clock in the morning and ordered everyone to come out; but this was not the end of their ordeal. Ranbir Kaur described what happened next.

The people in the basement were Muslims from Bangladesh who had nothing to do with the Akali agitation. They were non-Bengalis known as Biharis, who had sided with the Pakistan army during the liberation struggle in 1971, and had been living in refugee camps in Bangladesh for the last thirteen years. The Pakistan government had refused to accept responsibility for any more Biharis and so Bhindranwale and his followers were operating a profitable sideline smuggling them across the border.

Two young Sikhs, Sardul Singh and Maluk Singh, who had gone to the Golden Temple to celebrate Guru Arjun’s martyrdom day, were not released when the army entered the hostel. An elder from their village wrote to the Sikh President of India, Zail Singh, about their experiences. In his letter the elder, Sajjan Singh Margindpuri, said:

The five survivors of that night of horror were arrested by the army and taken away to interrogation camps. So were Ranbir Kaur, her husband, and the children in their care. Two months later three of the children that Ranbir Kaur had been looking after were released after a well-known social worker had filed a petition in the Supreme Court in Delhi. Ranbir Kaur was released at the end of August. She rejoined the three children who had been released but no one could tell her what had happened to the other nine.

The five survivors of that night of horror were arrested by the army and taken away to interrogation camps. So were Ranbir Kaur, her husband, and the children in their care. Two months later three of the children that Ranbir Kaur had been looking after were released after a well-known social worker had filed a petition in the Supreme Court in Delhi. Ranbir Kaur was released at the end of August. She rejoined the three children who had been released but no one could tell her what had happened to the other nine.

Speaking later of the battle of the hostel complex, Major- General Brar said:

That claim is not borne out by eye-witness accounts.

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of Mark Tully. You can buy Amritsar: Mrs Gandhi’s Last Battle here.

In the colonial period, the threat of the lecherous male gaze was used by the new patriarchy to restrict access to employment and public space for women, maintaining a patriarchal division of labour. Read how this process unfolded in our newest excerpt.

Saurav Kumar Rai

__

Was Lala Lajpat Rai's Hindu nationalism congruent with the principles of secularism? Explore our latest excerpt from Vanya Vaidehi Bhargav's fresh off-the-press book - Being Hindu, Being Indian: Lala Lajpat Rai's Ideas of Nation for more.

Vanya Vaidehi Bhargav

__

Popularly, we think that political cartoons question the powerful but what if this was not the case? What if political cartoons, replicated structures of the socially dominant? Read how in our new excerpt on political cartoons featuring Dr. Ambedkar.

Unnamati Syama Sundar

__

On Martyrs' day 2024, read the poet Sarojini Naidu's tribute to Gandhi given over All India Radio two days after his assassination.

Sarojini Naidu

__

On Republic Day, the Indian History Collective presents you, twenty-two illustrations from the first illustrated manuscript (1954) of our Constitution.

Indian History Collective

__

One of the key petitioners in the Ayodhya title dispute was Bhagwan Sri Ram Virajman. This petitioner was no mortal, but God Ram himself. How did Ram find his way from heaven to the Supreme Court of India to plead his case? Read further to find out.

Richard H Davis

__

Labelled "one of the shortest, happiest wars ever seen", the integration of the princely state of Hyderabad in 1948 was anything but that. Read about the truth behind the creation of an Indian Union, the fault lines left behind, and what they signify

Afsar Mohammad

__

How did Bengal get a large Muslim population? Was it conversion by ruling elites was there something deeper at play? Read Dr. Eaton's classic essay to find out.

Richard Eaton

__

An excerpt from Shailaija Paik's new book 'Vulgarity of Caste' that documents the pivotal role Tamasha (the popular art form) has played in reinforcing and producing caste dynamics in Marathi society.

Shailaja Paik

__

In 1942, two sub-districts in Bengal declared independence and set up a parallel government. The second part of our story brings you archival papers in the form of letters, newspaper reports, and judicial records documenting this remarkable movement.

Indian History Collective

__

In 1942, five years before India was independent, two sub-divisions in Bengal not only declared their independence— they also instituted a parallel government. The first in a new series.

Indian History Collective

__

In his own words, read Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi's views on the proselytising efforts taken on by the organisations such as Arya Samaj, Tabhligi Jamaat, and the Church Missionary Society of England.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

__

![The Golden Temple, Amritsar. [Credit: sandeepachetan.com, Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)]](http://indianhistorycollective.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Gtempke.jpeg)