(Quotes, where unattributed, have been excerpted from Monobina Gupta’s Didi: A Political Biography.)

Mamata Banerjee is a resident of Kolkata and has traditionally contested elections from the Bhabanipur constituency. For the 2021 Assembly elections, however, she has chosen to contest from Nandigram. The opposing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has been quick to brand her an ‘outsider’ and question her intentions for doing this. Commentators have attributed the decision to strategy, so that she could keep Suvendu Adhikari—a key rival politician from BJP, who was once her own partyman—occupied with Nandigram instead of touring the state. However, as this excerpt shows, not only does Banerjee have a significant connect with the constituency, it has been—in many ways—the (re)birthing ground for her political career.

Though she had been active both at the state and the national level for decades—including holding the post of railway minister in National Democratic Alliance (NDA) and United Progressive Alliance (UPA) cabinets—Didi (or ‘elder sister’, as Banerjee is popularly known) and the All India Trinamool Congress (TMC) were unable to do much to loosen the Left Front’s grip on the Chief Minister’s seat. It was only in the aftermath of the events of 2006 to 2009, marked by the milestones of three major people’s movements—Singur, Nandigram and Lalgarh—that the TMC emerged as a powerful electoral force in the state. As Monobina Gupta writes in Didi: A Political Biography, “Within three years of her Singur struggle, Mamata found an acceptance among all sections and classes of people that far exceeded her own expectation.”

Prior to her participation in these movements, Mamata Banerjee might have been admired for her “sheer ordinariness” or appreciated for her dramatic, firebrand style of politics, but she was not able to earn the support of the bhadralok or win enough mass votes to topple the CPI(M) in West Bengal.

The middle-classes of West Bengal, while known, Gupta writes, for their “radical, anti-establishment character,” are also marked by a “deep social and political conservatism.” In this context, Mamata Banerjee with her unpolished manners and ideologically uncommitted politics was unacceptable to them. Her lack of appeal was such that “even those sections of the bhadralok that were anti-CPI-M did not automatically accept Mamata.” But, with these three movements, not only was she able to “transcend barriers of class, culture and politics,” she also took over an important bastion of Communist support: the peasantry.

How did this change take place? What was the significance of Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh for a political career which had already witnessed many “catalytic agents”? What was Banerjee’s contribution to these movements? And, most importantly, as Gupta puts it, “Did the movements ‘make’ Mamata Banerjee? Or did she ‘make’ them?”

This chapter from Gupta’s book, titled ‘The Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh Journey’ answers all these questions and more.

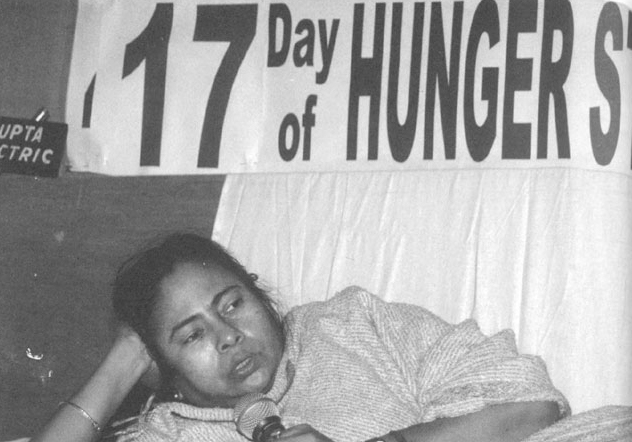

The chapter opens with reports of the rape and murder of a sixteen-year old activist from Singur: Tapasi Malik. The state government and its forces had established a veritable reign of terror in the region, intimidating, assaulting and even killing activists. Support was forthcoming—Mamata Banerjee herself was on an indefinite hunger strike protesting the land grab—but it was limited. The killing of Tapasi Malik became the tipping point. Perhaps because of its sheer shock value, it gave “the Singur agitation a razor-sharp edge,” Gupta writes, winning it the support of “civil society members, intellectuals, artistes, political activists of all stripes and NGO activists.”

In the early days of the agitation, the role of the TMC was limited to the participation of local MLA, Rabindranath Bhattacharya, in a broad-based, open movement, led by the Singur Krishi Jami Raksha Committee [SKJRC]. After September, 2006, the movement began to attract the support of more distant political and non-political personalities, including Mamata Banerjee. As leaders began to arrive at the site, the Left Front government initiated police action in a manner that had become its chief characteristic during its last few years. Banerjee was also attacked and manhandled and on the 4th of December, 2006, she began a fast to protest these state actions.

It was this moment, writes Gupta, which marked the shift from a “‘keep-away-from Mamata’ attitude”, amongst the state’s intellectuals, to a show of solidarity. But the change was slow. Kabir Suman, a singer-songwriter, who became an MP on a TMC ticket in 2009, was one of the first to visit her at the fasting site. As he himself admits, intellectuals and artistes were initially uncomfortable with supporting Mamata, especially considering her former alliance with the BJP. The tide began to turn slowly, in 2006, and by the end of the “Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh journey,” in 2009, she was able to win their support.

Her political style and rhetoric also underwent a change and, as Gupta astutely revals, she adopted the Left’s own arguments against liberalization and corporatization. Her skillful appropriation of the “political language and the idiom of the Left” is illustrated through her adoption of the slogan “Maa, Maati, Manush”, wherein each term referenced a different “aspect of the emotional-political charge” of the Singur-Nandigram movements. Of these, “Manush” (meaning ‘human being’) perhaps best exemplified Mamata’s political ideology as well as her personal image at the time: humanity, or humanism, in the face of a brutal and repressive state.

Changes in the attitude to Mamata were further solidified as the Nandigram and Lalgarh movements materialised and ran their course. Singur—an agitation against the government handing over to the Tatas over 1000 acres of fertile multi-crop land—would not, on its own, have been enough for such a drastic change in the TMC’s fortunes as the movement, playing out over two years, had begun to disappear from public discourse. But as that movement reached its end, Nandigram appeared on the horizon and “revitalized the final stages of the Singur movement as well.”

The Nandigram movement came up in response to the government’s decision to hand over 14,000 acres of land to Indonesia’s Salim Group of Industries. The region, which up till then was a CPI-M stronghold, was on edge as the peasants speculated about their future, while the party “operated with a total lack of transparency and made no attempt to initiate a democratic dialogue on the process of acquisition.” Eventually, the peasants threw their weight behind the Bhumi Uchchhed Pratirodh Committee (Committee against Eviction from Land) and drove CPI-M workers out. Much like Singur, the movement was initially broad based, with multiple actors and parties participating.

Similarly, it was initially the local TMC MLA, Suvendu Adhikari who represented TMC’s role in the movement. It is this same Suvendu Adhikari who is Mamata Banerjee’s chief opponent in Nandigram today, as a member of the BJP. The mainstream media had labelled him Mamata’s “lieutenant” at Nandigram, who continued to be TMC’s representative in that constituency as she chose to contest elections from her traditional Bhabanipur. It was only in 2021, as internal party rifts surfaced and Adhikari joined the BJP, that Mamata decided to test her electoral fortunes in Nandigram.

“Nandigram fortified Mamata’s image,” Gupta writes. It was in the aftermath of a brutal attack by policemen and CPI-M cadre, on 14th March 2007, that she became involved at a personal level. On the night of the attack, even as she was warned of the threat to her own safety, she insisted on going to Nandigram.

Though she was eventually unsuccessful, her resolve and bravery impressed many and drew her even greater support. In a state suffering from extreme political violence, corruption and autocracy, Didi became a symbol for “Paribartan (Change).” The ability to inspire hope for change in a state which had, for all practical purposes, been under one-party rule for three decades, reflected the status Banerjee had achieved in West Bengal’s politics. Even members of the “Leftist political stream,” particularly from the Marxist-Leninist parties, began to gravitate towards Banerjee. Some leaders, like Dola Sen, joined the TMC.

The CPI-M, despite its arrogance and complacency, realised the threat Banerjee posed. In a desperate last ditch attempt, it tried to accuse her of colluding with Maoists, who were responsible for a lot of violence in the state (interestingly, this was a charge that Didi occasionally levelled at political opponents herself). These accusations picked up strength as the Lalgarh resistance erupted, led by tribals who had long been neglected by the state government— a fact Banerjee was conscious of and was making into an issue. Mahasweta Devi, well-known for her support for adivasi rights, “remembers Mamata as a co-fighter in her battle against the Left Front government on behalf of the de-notified tribes.”

The Lalgarh movement had its origins in the brutal police action after a bomb blast on 2nd November 2008, targeting a centre-state delegation which included then CM Buddhadeb Bhattacharya. Though the leaders escaped, the state was vengeful in its response and innocent tribals had to face the brunt of it. Initially, a diverse group organised itself under the banner of the Pulishi Santrash Birodhi Janasadharaner Committee (People’s Committee against Police Atrocities), but the Maoists eventually “wrested control of the movement.” Subsequently, joint central and state forces occupied the region known as Jangalmahal.

Mamata’s support to and participation in this movement allowed the CPI-M to claim more assertively that she was colluding with Maoists. They tried to substantiate this charge by quoting her supporters, like Kabir Suman, out of context, or pointing to her disapproval of the extra-judicial killing of a top Maoist leader. Even the media picked up this line: “all anti-Left agitators as Maoists of one sort or another.”

In the midst of all this, writes Gupta “no one bothered to question the clear disconnect between the politics of the Maoists and the Trinamool Congress.” For a party whose goal was to win elections, it would be fatal to ally with an organisation that rejected the concept of democratic and electoral politics altogether. The only substance to this argument comes from the violence carried out by TMC cadres, particularly after 2009. However, given the culture of violence in the state, and the ready availability of arms, it was not really necessary to ally with Maoists to commit violence. It was easy, commonplace and accessible.

Perhaps the absurdity of this charge was clear to the public, if not the media and CPI-M leaders. The trajectory of TMC’s rise remained unaffected by it. It went from a dismal performance in the 2006 Assembly elections to “pulling off one electoral coup after another.” And then came the final victory in 2011. The CPI-M lost its grip on the state and Mamata emerged a winner. She has now been the Chief Minister for two terms consecutively while the Left front has been struggling to make a comeback.

At 7.30 a.m. on 18 December 2006, Mamata Banerjee heard of the murder of sixteen-year-old Tapasi Malik, an activist in the Singur agitation. At that time, the Trinamool leader was on an indefinite fast protesting coercive land acquisition in Singur. The agitation against handing over 1,000 acres of fertile multi-crop land to the Tatas for their Nano factory, where they would build the cheapest car in India, was spreading like wildfire.

‘I am writing this from the podium where I have been on fast. Here I learnt at 7.30 on the morning of the 18th that Tapasi Malik, who till yesterday was on fast with the rest of the protestors in Singur, has been raped and murdered earlier this morning at five. […] I spoke to Tapasi’s brother from the podium. I was told that despite the presence of the family, the police had rushed the body to hospital. Immediately, I urged Trinamool MP Mukul Roy, leader of the Opposition Partha Chatterjee, and Amitabha Bhattacharya to leave for the spot so that the police and CPI-M cannot brush the incident under the carpet,’ Mamata wrote.

Terror was stalking Singur. Activists were being intimidated and thrashed; some, like Rajkumar Bhulu and Tapasi Malik, were killed. Tapasi’s murder stunned the people of West Bengal, giving the Singur agitation a razor-sharp edge. Civil society members, intellectuals, artistes, political activists of all stripes and NGO activists all joined in.

Mamata Banerjee became the general secretary of the Indian Youth Congress in 1984, also the year where she defeated veteran Somnath Chatterjee to become one of the youngest parliamentarians of the country.

Mamata demanded a CBI inquiry into the murder. She finally had her way, but not before the CPI-M had launched a smear campaign, accusing Tapasi’s father of raping her. A look at the CPI-M’s rhetoric during this period may help us understand the dynamics of the Singur upsurge—a phenomenon that marked the beginning of Mamata’s ascendance in West Bengal politics.

Within three years of her Singur struggle, Mamata found an acceptance among all sections and classes of people that far exceeded her own expectation. She was finally the ‘real’ face of a political alternative. The more the CPI-M railed against the Trinamool Congress, the more people perceived Mamata as their deliverer from an arrogant ruling coalition. To understand her swift and dramatic transition from an erratic leader to a people’s person who could transcend barriers of class, culture and politics, we must revisit those three crucial years, 2006 to 2009.

By then, their backs to the wall on the Singur issue, the communists were lashing out. Much of the rhetoric—its lack of gender sensitivity for instance—would have been only too familiar to Mamata. Here is an example of the party’s vocabulary following Tapasi’s murder, from an article in the CPI-M mouthpiece People’s Democracy:

The Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) probing the case now believes that the young woman’s father and brother might have had something to do with her murder.

Tapasi’s death had been utilized shamelessly and to the hilt by the Naxalites, the SUCI initially, then followed up by the Trinamul Congress, the Pradesh Congress, and the BJP, to try to embarrass the CPI(M) and the Bengal Left Front government.

B. Prasant, author of the article, went on to say: ‘In all probability, the duo [Tapasi’s father Monoranjan and brother Surajit] will be subjected to sophisticated probing techniques, such as narco-analysis, brain-mapping and DNA testing. The blood samples taken from the murder site apparently do not match the samples of blood collected from Monoranjan and Surajit. The father-and-son may also be subjected to a “lie-detector” or “polygraph” test. The CBI has no doubt that young Tapasi Malik was killed in planned manner and that the story runs much deeper than what appearances would tell.’

Within three years of her Singur struggle, Mamata found an acceptance among all sections and classes of people that far exceeded her own expectation. She was finally the ‘real’ face of a political alternative. The more the CPI-M railed against the Trinamool Congress, the more people perceived Mamata as their deliverer from an arrogant ruling coalition. To understand her swift and dramatic transition from an erratic leader to a people’s person who could transcend barriers of class, culture and politics, we must revisit those three crucial years, 2006 to 2009.

A month later, the CBI arrested Suhrid Datta, secretary of the CPI-M Zonal Committee in Singur, and Debu Malik, a CPI-M supporter, in connection with Tapasi’s rape and murder. In 2008, the Chandannagar sub-divisional court sentenced both Suhrid and Debu to life imprisonment. Next year, the Calcutta High Court released Suhrid on bail, and jubilant CPI-M supporters organized a victory rally to celebrate their leader’s release.

West Bengal entered a new phase of its political history in 2006. The catalysts were Singur, Nandigram and, later, Lalgarh. Mamata stood at the threshold of a momentous phase of politics.

These developments impacted the quality of Mamata’s politics, moulding and transforming it. Her political plans had not involved becoming the nerve centre of movements of the calibre of Singur and Nandigram, with such far-reaching political and economic implications. But an unforeseen turn of events led her to this unfamiliar arena of peasants’ struggles, a quintessential feature of communist politics, a preserve of the Left. A qualitative shift marked Mamata’s transition from a theatrical activist to a figure around whom leaders, intellectuals, activists and artistes rallied. Even the well heeled, so far suspicious of her subaltern and unpolished ways, now began to view her with interest, if not admiration.

Mamata Banerjee’s first day at the Writers’ Building. Photo Credits: AITC Official.

The exit of the Tatas from Singur provoked political and economic pundits to pronounce Mamata’s doom. They said she’d be perceived as driving industrialization out of a state that was economically stagnant and in desperate need of industries. However, Mamata continued to gain electoral ground. The middle classes, dismayed though they were over the collapse of the Nano project and the exit of the Tatas, voted for the Trinamool Congress in the municipal elections. Even the middle-class Salt Lake area went the Mamata way. Clearly, anger against the Left exceeded innate reservations of class, politics and culture that in the past had weighed Mamata Banerjee down.

Today, most commentators, at least at the national level, believe that the continuum of movements—beginning with Singur, gaining ground at Nandigram, and then flowing into the tribal upsurge at Lalgarh—had their genesis in the Trinamool Congress and Mamata Banerjee. Without a doubt, Mamata—who had been virtually written off until then—was the most effective beneficiary of the movements. The pertinent question though is: did the movements ‘make’ Mamata Banerjee? Or did she ‘make’ them?

The CPI-M rhetoric is that these struggles are part of a Trinamool-Maoist conspiracy to derail industrialization and destabilize the progressive, secular, democratic (the Left Front’s three pet words) government.

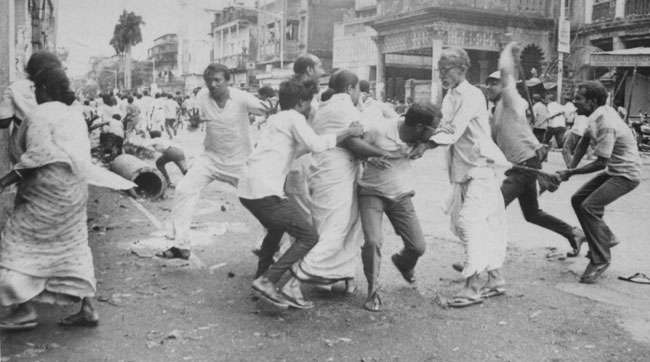

Mamata Bannerjee was attacked in 1990 by communist party goons. Photo Credits: AITC Official

But to return to our examination of the significance of these events in Mamata’s political life. There have been many catalytic agents in Mamata’s career: 1984, the victory against Somnath Chatterjee; 1990, the Hazra junction attack; 1998, founding the Trinamool; 1999, her appointment as railway minister. Like Singur and Nandigram, each one of these developments had been a marker of radical change in Mamata’s career. She defeated the veteran CPI-M MP when she was only twenty-nine years old and in the first lap of her political journey. The attack at Hazra junction on 16 August 1990 stamped her with the image of a bleeding victim, an incredibly brave woman, battling almost single-handedly, even if in vain, the CPI-M’s indomitable organization and state machinery. Mamata’s appointment as minister of railways marked her presence in West Bengal in a significantly different fashion, not just as the CPI-M’s aggressive combatant, but also as West Bengal’s ‘very own’ railway minister.

A qualitative shift marked Mamata’s transition from a theatrical activist to a figure around whom leaders, intellectuals, activists and artistes rallied. Even the well heeled, so far suspicious of her subaltern and unpolished ways, now began to view her with interest, if not admiration.

But the significance of Singur-Nandigram—coming as it did in the wake of the Left Front’s stunning electoral victory in 2006 and the Trinamool’s utter rout—was of another magnitude altogether. Between 2006 and 2009, the peasant movements changed all that, reinventing the Trinamool Congress, resurrecting and re-energizing its leader. All of a sudden, Mamata, went from being the chastened Opposition leader to becoming the most formidable contestant for power that the Left had ever tackled. Singur-Nandigram recast the image of the Trinamool, lending it the political content it sorely lacked. Crucially, the Trinamool breached the Left’s political territory, representing itself as a party of peasants and the underclass. As events unfolded, the party acquired a fundamentally new image, almost as if it had morphed into a new political entity.

In the past, Mamata Banerjee’s popularity had stemmed from her aura: her lower-middle-class background, her humble residence in a run-down area of Kolkata and her deliberate shunning of accoutrements of privilege. The Trinamool Congress leader seemed to stand out in her sheer ordinariness. But none of this helped her break through to the Left-leaning bhadralok activists, artistes and intellectuals. Not long ago, comments like ‘you do not entrust the maid with the keys to your house’ could commonly be heard in Kolkata. The radical, anti-establishment character of the bhadralok has always coexisted with a deep social and political conservatism. So even those sections of the bhadralok that were anti-CPI-M did not automatically accept Mamata.

Mamata Banerjee being sworn in as West Bengal’s Chief Minister for the second time. Photo Credit: AITC Official.

For all of these reasons, 2006 was a watershed in Mamata Banerjee’s political career. Armed with her breakthrough experience of popular political movements, the Trinamool president could now negotiate political business with the CPI-M from a position of strength. She was no longer an inconsequential, muddle-headed adversary.

The change in the political barometer was evident, and Mamata was now pulling off one electoral coup after another. Even her rhetoric was more than just emotional outbursts now. Many argue that, during this period, she acquired the political language and the idiom of the Left. For instance, her slogan ‘Maa, Maati, Manush’ was essentially born out of the struggles in Singur and Nandigram, each word drawing attention to a different aspect of the emotional-political charge of those movements: ‘Maa’ synonymous with Bengal, which to Mamata, was always supreme; ‘Maati’ standing for ‘land’ not just in an economic sense, but as something people are wedded to, around which their lives revolve; ‘Manush’ referring to humanity, to humanism, which Mamata believes to be her only political ideology in the face of brutal state repression and killing.

Peasant struggles, Mamata well knew, were what had given Left politics in West Bengal its unique identity. In Andoloner Katha, a collection of essays, Mamata seems to have imbibed—if not outright appropriated—the Left’s polemics on liberalization and the need for an alternative trajectory of development. She writes: ‘In the name of development, unethical and unprincipled professional politicians-turned-businessmen are out to sell the country’s education, civilization, culture and economy.’ Again: ‘Truly, the development of twenty people is today the primary objective of politicians. Why should they think of the concerns of millions of people? They have to think of just those twenty inordinately wealthy people. […] They call it industrialization, but it is actually a narrative of destruction.’

All of a sudden, Mamata, went from being the chastened Opposition leader to becoming the most formidable contestant for power that the Left had ever tackled. Singur-Nandigram recast the image of the Trinamool, lending it the political content it sorely lacked. Crucially, the Trinamool breached the Left’s political territory, representing itself as a party of peasants and the underclass.

Suddenly, Mamata’s party of ’non-intellectuals’ started drawing to its fold a large number of Left-wing academics, intellectuals, artistes. A section of the Left-oriented disenchanted voters began to seriously consider the Trinamool Congress as a viable electoral alternative. Many, however, still held out in the early days of turbulence. ‘More than Nandigram, Singur made a qualitative difference to the party,’ says a senior Trinamool Congress leader, adding: ‘It was the first in the series of movements that changed the political landscape.’

But Nandigram and Singur were certainly not the first time that Mamata had led agitations or mobilized huge crowds. If anything, fasts and dharnas were her most tested forms of agitation. For instance, human rights activists speak of her twenty-four-day dharna at Dharamtala against deaths in police custody. So what lent the Singur movement its special quality? In Mamata’s words: ‘I have agitated in the past; I have seen huge gatherings on the Brigade Parade Ground on

21 July as well as on other occasions. There would be a sea of people, but just on that one day. But never before have I seen a constant stream of people for so many days. Do remember, this place is really far and not easily accessible. It is difficult to reach the spot and stay here.’

Mamata Banerjee’s image being carried at a protest march in Singur. Photo Credit: AITC Official.

It’s true that Mamata gained immeasurably from these agitations then. But she did not ‘make’ them. Though Singur and Nandigram—even Lalgarh—are often tied to the Trinamool Congress, the reality is somewhat different. The roots of these resistances were scattered, not concentrated in one single individual or party. To the CPI-M, the diverse people in the movements were simply ‘outsiders’ (interestingly a term which was also used recently by Libyan President Col. Gaddafi against protesters demanding liberty in Libya). The CPI-M either failed to or refused to recognize the unusual character of these movements. Before we go on, it is important to outline the broad contours of the Singur-Nandigram movements to understand the context for the re-emergence of Mamata.

In the initial stages of the Singur movement, the Trinamool Congress’s contribution was confined to the active role played by Rabindranath Bhattacharya, the party’s local MLA. ‘It was everybody’s movement. The Singur Krishi Jami Raksha Committee [SKJRC] was heading the agitation, which included the SUCI and various factions of Marxist-Leninist parties,’ Pradip Banerjee, who headed the SKJRC for a while, told me.

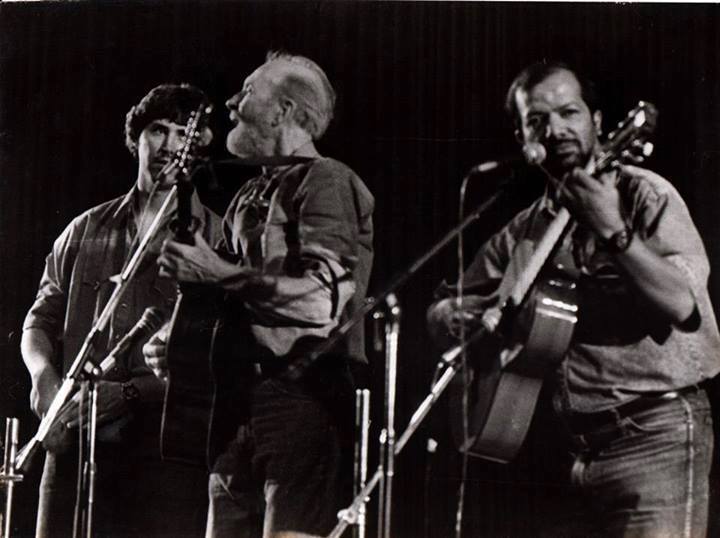

In the words of singer-songwriter Kabir Suman, who was elected to Parliament on a Trinamool ticket in the 2009 general elections, ‘The huge setback the Left suffered since 2006 was not due to any particular political party or leadership. The credit goes to the people of Bengal and the role of grambanglar jhanta (the broomstick of rural Bengal).’

Kabir Suman (Right) performing with Pete Seeger.

Leaders of political parties as well as members of non-political organizations started arriving at Singur following a gherao of the district magistrate and the block division officer on 25 September 2006. The protesters wanted to prevent ‘fake’ claimants from picking up the compensation cheques for the land acquired in the area. ‘Leaders and individuals—Mamata Banerjee, Saugata Roy, Asim Chatterjee, Barnali Mukherjee, Naba Datta—started arriving at the site of the dharna,’ Pradip Banerjee recounts. The police mounted a brutal attack, arresting over seventy women, including a two-and-a-half-year-old girl. Historian Kunal Chattopadhyay wrote: ‘A little after midnight, a blackout was created, and under the cover of darkness, a huge police force, according to the victims well lubricated with alcohol, attacked and brutally beat up the protestors, men, women and children. Ms. Banerjee was also manhandled, and her sari torn. She was then bundled off to Kolkata by force, and had to be admitted to a hospital.’ This attack escalated the tempo of the agitation. Mamata was emerging as the political and electoral symbol of the agitation. But even then, the SKJRC, the nerve centre of the movement and a platform of diverse non-partisan groups and individuals, enjoyed a great deal of autonomy in decision making.

In the initial stages of the Singur movement, the Trinamool Congress’s contribution was confined to the active role played by Rabindranath Bhattacharya, the party’s local MLA. ‘It was everybody’s movement. The Singur Krishi Jami Raksha Committee [SKJRC] was heading the agitation, which included the SUCI and various factions of Marxist-Leninist parties,’ Pradip Banerjee, who headed the SKJRC for a while, told me.

In the words of singer-songwriter Kabir Suman, who was elected to Parliament on a Trinamool ticket in the 2009 general elections, ‘The huge setback the Left suffered since 2006 was not due to any particular political party or leadership. The credit goes to the people of Bengal and the role of grambanglar jhanta (the broomstick of rural Bengal).’

‘All parties were invited—Subrata Mukherjee, then a Congress leader, Anuradha Talwar and Swapan Ganguly of the Paschim Banga Khet Mazdoor Samiti, Saifuddin Chowdhury and Samir Putatunda of the Party for Democratic Socialism,’ says Pradip Banerjee. After police attacked and arrested delegates on their way to Singur to attend an open convention, the range of participants widened. ‘We then approached the Congress, the breakaway Forward Bloc, Janata Dal (Secular), and Samajwadi Party to join the movement,’ adds Banerjee. Mamata began her fast on 4 December 2006, on a podium near Kolkata’s Metro Channel, in protest against the police action.

In Nishaaner Naam Tapasi Malik, his recently published best-selling book, Kabir Suman traces the beginning of his journey with Mamata as a participant in the Singur movement: ‘Mamata Banerjee had begun her fast. Abhash Munshi from the Mazdoor Kranti Parishad, Bijoy Upadhyay, president of the Samajwadi Party’s West Bengal unit, and radical activist Barnali Upadhyay had also joined her.’ Suman was then working with the current affairs programme at Tara News channel. ‘On the TV monitor, I saw CPI-M leaders addressing the media. A CPI-M leader cracked a joke about Mamata Banerjee getting hurt in the police attack at Singur. In full camera glare he said, “Why does she get hurt on her chest so much?” He kept repeating the ugly comment. I made up my mind, deciding to go to the spot where Mamata was fasting, to show my solidarity with her.’

Mamata Banerjee on a Hunger Strike. Photo Credit: AITC Official.

Suman describes his first face-to-face encounter with Mamata thus: ‘This was the first time I saw Mamata from close quarters and spoke with her. Exhausted from fasting, she was lying down, wrapped in a blanket. She tried to get up on seeing me and would not heed my protests. We had a brief conversation. She spoke in a low but spirited tone. I told her, “I have come here in solidarity. I am concerned about your health.” Folding her hands in gratitude, she said, “Please do not worry. I will continue my fast.”’

But Bengal’s intellectuals and artistes were still hesitant about sharing a podium with Mamata. ‘How many artistes and intellectuals had gone to the fasting site?’ asks Suman. Mahasweta Devi was one of the first ones to visit her and express solidarity. ‘For a long time, I have noticed the “keep-away-from Mamata” attitude. I really cannot claim that I myself was totally free from it. Truthfully, I did not like her alliance with the BJP; I could not accept its continuation even after the massacre of Muslims in Gujarat by Hindu fascists,’ is Suman’s candid confession. Rather than shun the sceptics, Mamata waited her turn, which arrived at the end of the Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh journey. Finally, she seemed to have whittled down the reservations of the large group of intellectuals and artistes. They were now firmly by her side.

[Kabir] Suman was then working with the current affairs programme at Tara News channel. ‘On the TV monitor, I saw CPI-M leaders addressing the media. A CPI-M leader cracked a joke about Mamata Banerjee getting hurt in the police attack at Singur. In full camera glare he said, “Why does she get hurt on her chest so much?” He kept repeating the ugly comment. I made up my mind, deciding to go to the spot where Mamata was fasting, to show my solidarity with her.’

The initial activity around land acquisition in Singur didn’t breach the barrier totally. In fact, after a point, the noise died down. Then in 2007, Nandigram erupted when police opened fire on protestors there. The long saga of the pitched battle in Nandigram seemed to re-infuse energy across the rest of the state. By 2008, Singur was on the boil again, and in the long run it would be Singur that would tip the scales politically in the state. In August 2008, dramatic scenes unfolded along the Durgapur Expressway. Different political parties and organizations set up twenty-one camps on the side of the road. Earlier, in 2006, Mamata had gone on a twenty-six-day hunger strike, demanding that the state government return 400 acres of land to the peasants of Singur. The finale to the tussle over the Nano project in Singur had begun.

‘Leaders, workers and, above all, people are staying here through day and night. […] People are bringing a handful of rice and dal for all the satyagrahis. MLA Rabinbabu is supervising the cooking of khichri. As soon as dawn breaks, the volunteers get down to work, cleaning the area. A total of twenty-one camps: the first one supervised by Mukul [Mukul Roy] and the twenty-first by Bani Sinha Roy.’ This was Mamata’s description of those days.

Kabir Suman and Mamata Banerjee.

The movement had its own brand of ‘Mamata aesthetics’ as she sat with an easel on the podium and applied her paintbrushes to canvas. Some people sang Rabindrasangeet and others sang songs of the revolutionary IPTA composer Salil Chowdhury. Meanwhile, hectic negotiations were under way inside Raj Bhavan. Upon Mamata’s request, Governor Gopalkrishna Gandhi, the mediator, was trying to find a face-saver for the Left Front government; a last-minute unravelling of the hopelessly tangled plot of Singur. But the intractable deadlock remained in place as firmly. Finally, the Tatas packed up and left. The Nano, supposed to have been a feather in the CPI-M government’s worn-out crown, lay in tatters.

‘The CPI-M transferred the entire blame for the situation to the Opposition. According to them, Mamata Banerjee had prevented West Bengal’s industrialization. To me, that explanation is not acceptable,’ says Abhirup Sarkar, an economist at Kolkata’s Indian Statistical Institute. Sarkar is close to Mamata and was at one point rumoured to be in the running for the post of finance minister in the Trinamool government. Though Sarkar did not accept her offer to contest the polls, he continues to be an advisor to Mamata. He points to data from the manufacturing sector to shore up his arguments: ‘West Bengal’s industrial decline had started from the 1980s. In this period, the state’s contribution to the all-India manufacturing sector was a little less than 13 per cent. In 2009, that figure stood at a little above 2 per cent. In the 1980s, only four states— Maharashtra and Gujarat (the industrially advanced), and Punjab and Haryana (the agriculturally prosperous)—were ahead of us. Now the entire south and Himachal Pradesh have overtaken us; soon Rajasthan will too. Industrial decline was an ongoing process. It did not suddenly dip because the Singur project could not take off.’

The initial activity around land acquisition in Singur didn’t breach the barrier totally. In fact, after a point, the noise died down. Then in 2007, Nandigram erupted when police opened fire on protestors there. The long saga of the pitched battle in Nandigram seemed to re-infuse energy across the rest of the state. By 2008, Singur was on the boil again, and in the long run it would be Singur that would tip the scales politically in the state.

So does he give no credence to the argument that Mamata forcefully stalled the Nano project? ‘When Mamata Banerjee began her opposition she had no political support. In 2006, she could not have stopped the Singur project forcefully, simply because she hardly had any political power then. In fact, things worked the other way: the Singur movement made Mamata Banerjee powerful,’ Sarkar suggests. Many have argued that the West Bengal government could have neutralized the resistance had it drawn up a better compensation deal. Perhaps––but even that would not have worked if the government had gone ahead and terrorized people, hoping to bully them into submission. Sarkar draws an interesting parallel between the experiences of peasants in Singur and Mexico City.

In 2002, a proposal was mooted to build a second airport outside Mexico City. Land belonging to peasants had to be acquired. There was resistance to the project. The compensation that was initially offered fell far below expectations, and to add salt to injury, the police beat up and arrested resistance leaders. Eventually, popular discontent forced the government to offer a huge compensation amount. But the peasants refused. ‘The lesson from here and Singur is that we are dealing with human beings, not robots,’ Sarkar says. He argues that the resistance in Singur met with a similar aggressive, violent response from the government. ‘At first they beat up people, raped women and then they offered more money. Why should [the people] take it?’

He describes the experience of working on a project in Singur as being straight out of a film. ‘I went to Singur with a couple of economists doing a project in the area. During our work—just like in Bengali films—two men came on a motorbike, followed by three chamchas and started heckling us.’ The men, from the CPI-M cadre, were suspicious of ’outsiders’ and obstructed their work. This intimidation of perceived outsiders is characteristic of the CPI-M’s politics, its constant distrust of those who are not its own. Sarkar’s comparison to scenes like this in popular Bengali cinema is quite apt. In many a popular film, the damsel in distress or the hero is attacked by hooligans who work for the villain—often a rich landowner or member of the bourgeoisie, and sometimes of an unnamed ‘party’!

The Singur saga played out over two years—from 2006 (when a confident Left Front government acquired the land) to 2008 (when the Tatas finally left). And when the Singur crisis seemed to have reached a point of stasis, Nandigram exploded, an explosion that revitalized the final stages of the Singur movement as well.

In 2002, a proposal was mooted to build a second airport outside Mexico City. Land belonging to peasants had to be acquired. There was resistance to the project. The compensation that was initially offered fell far below expectations, and to add salt to injury, the police beat up and arrested resistance leaders. Eventually, popular discontent forced the government to offer a huge compensation amount. But the peasants refused. ‘The lesson from here and Singur is that we are dealing with human beings, not robots,’ Sarkar says. He argues that the resistance in Singur met with a similar aggressive, violent response from the government. ‘At first they beat up people, raped women and then they offered more money. Why should [the people] take it?’

In 2006, Chief Minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee handed over 14,000 acres of land in Nandigram to Indonesia’s Salim Group of industries to set up a chemical hub. Like in Singur, the CPI-M looked the other way while resentment simmered and a Bhumi Uchchhed Pratirodh Committee (Committee against Eviction from Land) was set up. For almost a year, people were left to speculate in the dark, uncertain and apprehensive about the ramifications of the decision. The government operated with a total lack of transparency and made no attempt to initiate a democratic dialogue on the process of acquisition. Despite arm-twisting by Lakshman Seth, CPI-M’s powerful MP in the area, the peasants threw their weight behind the forces of resistance. They drove CPI-M workers out of Nandigram, until then a party stronghold. The violence that CPI-M workers unleashed against the protesters is by now well known. The best known of these incidents occurred on 14 March 2007, when the police—among them a section of CPI-M workers masquerading as policemen—brutally attacked peasants, unintentionally ‘creating’ a mass movement.

Singur and Nandigram shared many similarities, among them the diversity of the participants in these struggles. Mamata did not personally intervene in the initial stages of the agitations. Trinamool Congress MLA Shubhendhu Adhikari was at the forefront of the Nandigram movement alongside activists from many other organizations and parties. The presence of activists from various factions of Marxist-Leninist parties gave the CPI-M fodder for its ‘Mamata-Maoist nexus’ campaign, which reached its height in the wake of the Lalgarh crisis.

Suvendu Adhikari, once a close aide of Banerjee, is now a member of the BJP. Photo Credits: PTI.

Nandigram fortified Mamata Banerjee’s image. Her colleagues and fellow activists from those days recall 14 March 2007 with special clarity. At Mamata’s Kalighat residence, everybody was on their mobile phone. News of a savage attack by CPI-M cadres and policemen in Nandigram had thrown them into a tizzy. Mamata was talking to journalists. She had decided to go to Nandigram. On her way, she spoke to leaders of the Congress and the BJP, including L.K. Advani. But nobody seemed to have a clue about how to rein the CPI-M in. Kabir Suman, who was travelling in a car with Mamata then, writes:

I notice the Congress is not paying that much heed. Where is the prime minister? He must know what is happening here. Why can he not call up Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee and ask him to stop the rape and murder? Then, does everyone want such chaos to continue in West Bengal?

At Mecheda, the CPI-M stopped our convoy. Mamata’s car was right in front. Sitting right behind her, I could see what kind of lewd gestures the party cadres were making at Mamata… In that crowd there were boys, men—both young and old—and women too. I cannot believe that such terrible, ugly comments can be made targeting a woman. Mamata sat furious. After continuing like this for a long time, the cadres moved away.

Mamata Banerjee riding pillion to visit violence affected people in Tamluk, Nandigram.

In the evening, Mamata reached Tamluk hospital, where the wounded had been brought. Some grievously injured, some dying. Mamata was by the side of a woman with a bullet in her lower stomach. As cameras zeroed in on the scene, Mamata pulled up the media. Subrata Mukherjee arrived at the hospital fighting attacks on his car by CPI-M workers. Mamata, despite repeated warnings of danger, was determined to go to Nandigram that very night. She was stalled finally by a barricade set up by a massive CPI-M contingent. It took a great deal of persuasion to get Mamata to turn back. The one quality that impressed and widened Mamata’s circle of friends, supporters and colleagues was her courage and fearlessness. Some of them say that her years of life-threatening combat with the CPI-M had left her virtually without fear of death. For Abhirup Sarkar, Mamata’s persona is a combination of three ‘sha-s’. ‘I would describe Mamata Banerjee’s personality as a sum total of Bengali shahas (courage), shatata (honesty) and sharalya (simplicity),’ he says.

Mamata did not personally intervene in the initial stages of the agitations. Trinamool Congress MLA Shubhendhu Adhikari was at the forefront of the Nandigram movement alongside activists from many other organizations and parties. The presence of activists from various factions of Marxist-Leninist parties gave the CPI-M fodder for its ‘Mamata-Maoist nexus’ campaign, which reached its height in the wake of the Lalgarh crisis.

Nandigram fortified Mamata Banerjee’s image. Her colleagues and fellow activists from those days recall 14 March 2007 with special clarity. At Mamata’s Kalighat residence, everybody was on their mobile phone. News of a savage attack by CPI-M cadres and policemen in Nandigram had thrown them into a tizzy. Mamata was talking to journalists. She had decided to go to Nandigram.

The Singur and Nandigram movements worked at many levels. Primarily, they sparked an ‘audacity of hope,’ says Sujato Bhadra, playing on Barack Obama’s famous phrase. ‘Mamata Banerjee has become a symbol of change,’ he told me. ‘Paribartan’, a word that had fallen out of Bengal’s political dictionary, was now on everybody’s lips. Amid the churnings, Mamata gained some unexpected allies, many of them from the Leftist political stream. Sections of the Marxist-Leninist factions in the state were one such group. Their intrinsic suspicion of Mamata broke down when they saw her grit and involvement in Singur, Nandigram and, later, Lalgarh. Mamata’s association with Marxist-Leninist parties, inconceivable even a few years ago, firmed up during 2006-09. Some, like Purnendu Bose and Dola Sen, who formally joined the Trinamool Congress, are now among her closest political aides. Others, like Pradip Banerjee, did not join Mamata’s party, but did actively campaign for her in the assembly elections. But the political Left wasn’t the only force that took a sudden interest in Mamata, as we shall see in the next chapter.

Following the epic confrontations in Singur and Nandigram, a third rebellion gathered force in the tribal districts of rural Bengal, for long repressed by an uncaring establishment and an indifferent state.

In Lalgarh, in the West Medinipur district of West Bengal, the tribal people began agitating in the winter of 2008. It was an exemplary struggle—democratic and diverse—till the Maoists wrested control of the movement and the joint Central and state forces occupied the region known as Jangalmahal. In the initial stages, like in Singur and Nandigram, many different organizations and political parties gathered and functioned democratically under the Pulishi Santrash Birodhi Janasadharaner Committee (People’s Committee against Police Atrocities). Later, the Maoists hijacked the movement, stifling it before the resisting tribals could achieve some of their basic demands.

A mass meeting of the PCPA at Lalgarh. Photo Credits: Democratic Students Union, Facebook.

The genesis of the Lalgarh resistance was a bomb blast on 2 November 2008, targeting a high-profile Central and state delegation, including Chief Minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee. They narrowly escaped with their lives from the blast set up by Maoists in Shalboni. In spite of extensive reconnaissance before the delegation’s arrival, the police had failed to detect the long wire that set off the ambush. To make up for this major lapse, the police began a massive hunt for the culprits, with savage reprisals on the tribals. But inhabitants of this region had long been familiar with police brutality. And from about 2000, the Maoists too were gaining influence in the poverty-ridden areas of Jangalmahal, including the three most backward districts, Purulia, Medinipur and Bankura.

The success of the peasant movements in Singur and Nandigram inspired the restless tribals of Lalgarh to teach the uncaring government a lesson. Mamata Banerjee became part of the upsurge much later. In fact, she was allowed to join a rally of the People’s Committee against Police Atrocities (PCPA) on condition that she would not carry a Trinamool Congress banner.

In Andoloner Katha, Mamata recounts her memory of Lalgarh as she had seen it in 1992 when she was criss-crossing West Bengal, trying to revive the Congress through her interactions with people. She began her month-long journey from Belpahari in West Medinipur on 12 January, coinciding with Vivekananda’s birthday. ‘I got news of the desperate plight of the adivasis—nine out of twelve months a year, they cannot get rice. I decided to visit an adivasi village. Without informing anyone, I hitched a ride with a local boy on his scooter and reached Jeb, an adivasi village. With us, some friends in the media also reached the spot,’ she writes.

The success of the peasant movements in Singur and Nandigram inspired the restless tribals of Lalgarh to teach the uncaring government a lesson. Mamata Banerjee became part of the upsurge much later. In fact, she was allowed to join a rally of the People’s Committee against Police Atrocities (PCPA) on condition that she would not carry a Trinamool Congress banner.

In Andoloner Katha, Mamata recounts her memory of Lalgarh as she had seen it in 1992 when she was criss-crossing West Bengal, trying to revive the Congress through her interactions with people. She began her month-long journey from Belpahari in West Medinipur on 12 January, coinciding with Vivekananda’s birthday. ‘I got news of the desperate plight of the adivasis—nine out of twelve months a year, they cannot get rice. I decided to visit an adivasi village… ” In the village she met women who, she claims, cooked a broth of red ants with roots of trees for food.

In the village she met women who, she claims, cooked a broth of red ants with roots of trees for food. ‘I not only raised the plight of the adivasis at public meetings, but also brought it to the notice of the government so that justice could be done. Sections of the media also put out the news. But the suffering of the adivasis still continues,’ Mamata says in the book. Mahasweta Devi remembers Mamata as a co-fighter in her battle against the Left Front government on behalf of the de-notified tribes. ‘She helped me when I filed a case against the state government,’ the author-activist told me.

Mamata’s association with the Lalgarh movement sharpened the Left’s accusation that the Trinamool was colluding with the Maoists, an allegation that went back to the days of the Nandigram agitation. While in Lalgarh, the Maoists did have a dominant presence even before they took over the movement lock, stock and barrel, in Nandigram the Trinamool-Maoist nexus might have been just a flight of CPI-M fancy. Without going into the intricacies of a movement as complex and diverse as Lalgarh—at least when it first started—various sections branded the PCPA as a Maoist front and its leader Chhatradhar Mahato as a Maoist agent. Mamata’s meeting with Mahato was touted as incontrovertible proof of a Trinamool-Maoist nexus, as was Mahato’s membership of the Trinamool in his younger days. By the same logic, film actors, authors, poets and artistes who had gone to Lalgarh and spoken to Mahato were said to be helping the Maoist cause.

Mamata Banerjee with Chhatradhar Mahato (Right). Photo Credits: Alechtron.

In all that noise, no one bothered to question the clear disconnect between the politics of the Maoists and the Trinamool Congress. The media too seemed content to club all anti-Left agitators as Maoists of one sort or another. It is important here to make a distinction between the democratic politics of the various Marxist-Leninist parties, which played a crucial role in the Singur and Nandigram agitations, and the project of violent overthrow of the Indian state as espoused by the Maoists. Some people from the Marxist-Leninist parties who had worked closely with Mamata in Singur and Nandigram even switched loyalties to align firmly with the Trinamool.

‘One afternoon Mamata telephoned me. She seemed agitated. She told me, “I don’t know, Kabir-da, in this situation created by the CPI-M, how long we can practise democracy in this state. I will take one more chance, then I will take up arms,”’ Kabir Suman says in his book, adding: ‘Considering the situation from all aspects, my mental state was also similar. How can I take up arms at my age? Yet I felt, to hell with everything. What is the point of living like this?’

The CPI-M pounced on this section of Suman’s book, splashing it across its party organ, Ganashakti, and pointing to it as a confirmation of their theory of Trinamool-Maoist nexus. If you care to read till the end of the page, however, you find this: ‘I concede that, given the state of my mind, Mamata’s suggestion of taking up arms touched a chord in me. At that point, I did believe Mamata was my comrade, one of us. […] I do agree there was certain romanticism in that thought. But can you fight a battle without any romanticism?’

‘One afternoon Mamata telephoned me. She seemed agitated. She told me, “I don’t know, Kabir-da, in this situation created by the CPI-M, how long we can practise democracy in this state. I will take one more chance, then I will take up arms,’” Kabir Suman says in his book… The CPI-M pounced on this section of Suman’s book, splashing it across its party organ, Ganashakti, and pointing to it as a confirmation of their theory of Trinamool-Maoist nexus.

Battling the establishment, particularly through armed insurrection, has always carried with it a certain aura of romance, the dangerous bravura of staring death in the face. Che Guevara, now heavily marketed the world over by multinational companies, would undoubtedly be the face of this romantic, ruthless battle. The first armed uprising of the Naxals in India was indeed imbued with this spirit of adventure, romance, even innocence. Suman, who wears his empathy with the Maoists on his sleeve, was referring to this spirit of romance. All that Suman’s quote suggests is that taking up arms against the CPI-M’s armed militia was a fleeting, impulsive thought that crossed both Suman’s and Mamata’s mind in a situation that seemed to have become desperate, tinged with a sense of poetry rather than a desire for programmatic political violence.

Did Mamata plot with the Maoists to subvert the law and order situation in West Bengal in order to dislodge the already tottering Left Front government? Highly unlikely. Was there a convergence of the Maoists’ and Trinamool’s political objectives? To an extent, yes. All three movements—Singur, Nandigram and Lalgarh—were born outside the pale of formal party structures. Their diversity accommodated groups that may not have been in agreement about strategies of protest and resistance.

Mamata Banerjee at a rally in Nandigram, from where she contested the 2021 State Assembly elections, in January 2021. Photo Credits: PTI.

The discussion of West Bengal’s culture of competitive violence shared by armed workers belonging to both CPI-M and the Trinamool Congress camps should not be conflated to the thesis that the Trinamool Congress was working in perfect tandem with the Maoists to realize their political project. The questions that seem relevant are: Do the Trinamool workers on the ground, and across districts, keep their distance from the Maoists? Or do the Trinamool workers and Maoists exchange arms and fortify each other against the Left Front government?

Interestingly, Mamata too has accused the CPI-M of being in league with the Maoists, a somewhat fantastic charge. The dominance of violence in West Bengal’s political culture makes it possible that the Trinamool fought the comrades with arms. The escalation of violence in the aftermath of CPI-M’s crushing defeat in 2009 and the Trinamool Congress’s recent electoral victories are just a couple of the many corroborating evidences. In a culture where knives and bullets are wielded freely to claim political ground, to square up with political opposition in day-to-day life, the Trinamool need not enter into a pact with the Maoists. Arms are easily available and acquired here.

The discussion of West Bengal’s culture of competitive violence shared by armed workers belonging to both CPI-M and the Trinamool Congress camps should not be conflated to the thesis that the Trinamool Congress was working in perfect tandem with the Maoists to realize their political project. The questions that seem relevant are: Do the Trinamool workers on the ground, and across districts, keep their distance from the Maoists? Or do the Trinamool workers and Maoists exchange arms and fortify each other against the Left Front government? …

The dominance of violence in West Bengal’s political culture makes it possible that the Trinamool fought the comrades [the CPI-M] with arms. The escalation of violence in the aftermath of CPI-M’s crushing defeat in 2009 and the Trinamool Congress’s recent electoral victories are just a couple of the many corroborating evidences. In a culture where knives and bullets are wielded freely to claim political ground, to square up with political opposition in day-to-day life, the Trinamool need not enter into a pact with the Maoists. Arms are easily available and acquired here.

The CPI-M did not get much electoral mileage out of its Mamata-Maoist nexus campaign. But it did try hard. After every incident of violence in the state, after every public meeting the Trinamool chief attended, after every speech she delivered, the accusations would resurface. On 9 August 2010, addressing a public meeting in the heart of Lalgarh, Mamata said the manner in which Azad, a top Maoist leader, had been killed was ‘not right’. She demanded that the government investigate the incident. All hell broke loose when the media picked up this speech and the CPI-M pointed to the statement as further vindication of its theories. Interestingly, four

months later, in January 2011, the Supreme Court asked the Central government and the state administration in Andhra Pradesh to explain how exactly Azad had died in the Adilabad forests of Andhra Pradesh, making it clear that the case was far from a simple ‘anti-terrorist’ action by the administration.

As West Bengal’s assembly elections approached, the CPI-M accelerated the thrust of this campaign. Chief Minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee responded to Home Minister P. Chidambaram’s request for disbanding the CPI-M’s armed militias (Harmad Vahini) with his own list of camps testifying to the ‘Trinamool-Maoist alliance’. In October 2010, sabotage by suspected Maoists led to the horrifying Gyaneshwari Express accident, claiming 150 lives. In her first reaction to the incident, Mamata pointed a finger at the CPI-M, insinuating that the ruling party could have plotted the sabotage to defame her. The CPI-M retaliated, coming down like a ton of bricks on the ‘absentee’ railway minister, accusing her of ’hobnobbing’ with the Maoists. Umakanta Mahato, a prime Maoist suspect in the Gyaneshwari sabotage, was later killed by the security forces in a gun battle.

As usual, the truth probably lies somewhere in between. It is highly unlikely that Mamata Banerjee would have jeopardized her political prospects by endorsing the brand of politics practised by the Maoists. Electoral democracy is not the way that the Maoists engage with the political class. Even if Mamata, as Opposition leader, had hoped to befriend them in pursuit of the classic ‘my enemy’s enemy is my friend’ approach, the political cost of swinging deals with the Maoists would have been far too dear. She had waited a long time to reach where she is now.

As usual, the truth probably lies somewhere in between. It is highly unlikely that Mamata Banerjee would have jeopardized her political prospects by endorsing the brand of politics practised by the Maoists. Electoral democracy is not the way that the Maoists engage with the political class.

Acquiring arms however has become as common to West Bengal’s political culture as abarodh or blockades on streets, highways and railway tracks on every issue of importance. But how convincing is the CPI-M’s continued attribution of all the ills that have befallen it to the handiwork of Mamata and the Maoists? Not very, for the people did not bite the bait. Mamata won the corporation elections hands down after the horrifying Gyaneshwari Express derailment—the continuation of a political trend that began in the 2008 panchayat elections and culminated in the 2011 assembly elections. The Lalgarh movement ought not to be remembered as a symbol of a Mamata-Maoist alliance, but for what it actually represented: yet another section of Bengali society, long forgotten by the government, rising in protest against the order of things, demanding basic needs that it had long been deprived of.

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of Monobina Gupta. You can buy Didi: A Political Biography here.

Monobina Gupta is a journalist, and author of Didi: A Political Biography of Mamata Banerjee; and Left Politics in Bengal: Time Travels Among Bhadralok Marxists. She is currently completing a book on the subterranean history of the Hindu Right in Bengal. You can read her articles here and here.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply