Govind Pansare’s bestselling Shivaji Kon Hota? is remarkable not just for the amount of historical research Pansare uses to dispel myths around the Maratha hero but also for the lucid and easy style in which it has been written. The book has sold over 2,00,000 copies in eight languages and has been translated from the Marathi into English (Who Was Shivaji?) by Uday Narkar.

Historian Anirudh Deshpande writes in the introduction to the book: “The strength and popularity of Shivaji Kon Hota? must be perceived in it not being a product of professional history. It is a modern text not tainted by the historical imagination of nationalism. The book’s lasting relevance, readers will realize, lies in its unostentatious application of reason and the historical method of Marx to a highly emotive subject of Indian history.”

Prabhat Patnaik writes, in the afterword, how Pansare portrays Shivaji neither as an “upholder of Hinduism” nor as a “mere ‘backward caste’ leader asserting himself against Brahmanical dominance” but as “a ‘secular’ ruler who pioneered a Welfare State”. Also: “Pansare’s book is based on a speech he delivered in May 1987. It portrayed Shivaji not only as socially progressive, but also as a rationalist.”

In the chapter from the book that we have carried below—‘Shivaji and Religion’—Pansare uses logic as well as historical sources and scholarly works to argue against the assumption that Shivaji is a suitable icon for Hindutva. He does this by breaking up the chapter into 11 sections, each section building up to his thesis. Hence, he takes us through the question of what Shivaji’s approach to religion actually was, to his popular image as a ‘Hindu emperor’, to a similar image being built up for Rana Pratap and Prithviraj Chauhan, to what historical records tell us about the attitudes of Hindu and Muslim rulers of the time as well as Hindus and Muslims who served under rulers from both religions. He goes on to the contentious subject of the ‘Loot and Destruction of Temples’: what these were actually driven by, and purpose they were meant to serve, versus how they are perceived today. He contextualises this with records of endowments given to temples by Muslim rulers, as well as the loot of temples by Hindu rulers. He builds the case that “power” rather than “religion” was the dominant theme behind such attacks. Further, he lists Shivaji’s battles against other Hindus and Marathas, including Shivaji’s own relatives.

In the concluding section, while stressing Shivaji’s “pride” in being a Hindu, Pansare underscores the Maratha hero’s open and rational approach to faith by citing – as he does throughout the chapter – various sources as evidence. One that stands out is a line written by Shivaji’s chief justice, Raghunath Pandit Rao: “Shrimant Mararaj has ordained that everybody is free to follow his religion and nobody is allowed to disturb it.”

Another is a letter written by Shivaji to Aurangzeb, whose translation we have also carried in full below (courtesy LeftWord Books).

What was Shivaji’s approach to religion in general? What was his actual practice in this respect? How did he treat both Hindu and Muslim religions? These are historically very important questions. These are also relevant in today’s times.

Shivaji was a Hindu. He was born in Maharashtra and it remained his place of operations throughout. Hindus therefore are proud of him. It is quite natural. Maharashtrian Hindus in particular are more proud of him. It is also very natural — nothing wrong in it. It is but human to look at one’s own greatness, the greatness of one’s own religion, and the greatness of one’s own country or region in the light of the great heroes belonging to one’s own religion. Moreover, the fewer the number of such heroic people in a community or a religion the more ordinary people take pride in them.

However, we tend to create, unconsciously, a larger than life image of such “heroes.” Many times the image is deliberately projected as one-dimensional as it suits one’s present day purposes and conveniences. In the process, a distortion creeps in and the image itself becomes distorted. It loses its identity.

There are several reasons why Shivaji’s work, his administration, his time, his social reforms and his attitude to religion are not projected adhering to the historical truth. His image in popular imagination is sometimes contrary to the truth.

Even an illiterate Maharashtrian knows Shivaji. They know the stories of his life. They know many things — places, names, incidences related to him. How did all this information reach out to the four corners of Maharashtra?

Innumerable ballads on Shivaji, his times, on miraculous, dramatic and sublime incidences in his life have been sung. Can one name a Marathi shahir, a bard, whether in Shivaji’s time or even today, who has not sung of Shivaji? The answer is an emphatic “No.” Every shahir has done it, and they are right to do so. The same is true of folk songs and all folklore. Kirtanas are no exception. Take anything — speeches, discourses, theatre and cinema. These are the means by which history is taken to people.

Distortions, interpolations in the historical accounts in the process of imaginative reconstruction, are not unlikely. Even if we overlook such distortions, we have to admit that the media mentioned above have their own natural limitations.

There are several reasons why Shivaji’s work, his administration, his time, his social reforms and his attitude to religion are not projected adhering to the historical truth. His image in popular imagination is sometimes contrary to the truth.

How can the miracles be done away with if the audience gathers to be entertained? The ballad would be quite uninteresting without some “imaginative” stories. Various figures of speech become indispensable, especially the hyperbole. If these “performances” were to only enumerate the figures of historical dates, and not use the figures of speech, if they were to logically analyze, and not to resort to the hyperbole, would there be a second “performance”? Moreover, the authors-performers have to take into account the level of understanding of their audiences. They themselves have their own limitations. All this has contributed to creating the image of Shivaji in the way we have received it. Of course there are many other factors involved in the distortion: self-interest, contemporary political expediency, a wrong approach to history or, at the least, inadequate understanding, and so on.

Shivajis image, widespread amongst the masses, could be summarized thus: “Shivaji was anti-Muslim. His life mission was to oppose the Muslim religion. He was a protector of the Hindu religion. He was a Hindu Emperor (Hindu Padpatshah). He was a protector of cows and Brahmans (Go-Brahman Pratipalaka).”

A couplet by his contemporary poet, Bhushan, reflects this image. He wrote, “Shivaji na hota, to sunta hoti sabki” (“But for Shivaji, all would have been forcibly circumcised”). There have been such similar instances of misinterpretation held in a large number. “Shivaji’s war was a kind of crusade. Religion was the inspiration of his mission, Shivaji fought for religion. He succeeded because he fought for religion. In fact, he was a reincarnation of God himself! He was the reincarnation of Vishnu or Shiva. God took on this reincarnation to save the religion. Goddess Bhavani gifted the sword to save the religion.”

So on and so forth.

All these theories need to be tested against the historical facts. It will not be proper to uncritically accept them because we are Hindus or because they are convenient to us in the present circumstances. At the same time we should also beware of its flipside. There is a growing tendency among the Muslims to say, “We belong to the Muslim religion. It is our need to teach Muslims to hate Hindus. As many Hindus worship Shivaji; we should hold him as the savior of Hindu religion and as an aggressor of Muslim religion.” Such an uncritical approach too is erroneous. What is the truth?

Shivajis image, widespread amongst the masses, could be summarized thus: “Shivaji was anti-Muslim. His life mission was to oppose the Muslim religion. He was a protector of the Hindu religion. He was a Hindu Emperor (Hindu Padpatshah). He was a protector of cows and Brahmans (Go-Brahman Pratipalaka).”

Rana Pratap and Prithviraj Chauhan

Let us take the claim: Shivaji succeeded because he was a savior of Hindu religion. If this were the fact why did Rana Pratap or Prithviraj Chauhan not succeed? In actual fact, both of them were high caste Kshatriya Hindus. At least some people had doubts about Shivaji’s being a Kshatriya. Both Rana Pratap and Prithviraj Chauhan were no less than Shivaji in respect of bravery, sacrifice, determination and hard work. Possibly they could be a grade better than him in these aspects. Then why did history take the course it did? If it was a religious crusade, why did one succeed and why were the other two badly defeated? If it was God’s will that the Hindu Rashtra be founded then why was it founded in Maharashtra alone? Why did God not will that it be founded in Rana Pratap’s and Prithviraj Chauhan’s land as well?

It is not true that Shivaji succeeded because he believed in the Hindu religion. Evidence suggests that he set out to do something better for the world than merely save his religion.

Let us assume for a moment that his contemporary rulers belonged to a religion other than Islam. Suppose, there were kings belonging to the Hindu religion. Would Shivaji, then, hate Muslims? Why did Shivaji fight against the Muslim kings? Was it because they were Muslims or because they were kings? If he fought for both the reasons, then which of the two was the main reason? What was important: their being kings or their being Muslims?

The historical record shows that not all Muslim kings were intolerant to Hindus and to the Hindu religion. History provides us with several instances of the tolerance of Muslim rulers. In Maharashtra, Shivaji’s province, we find many Muslim rulers who had political and familial relations with Hindus. Dattatray Balwant Parasnis’ Marathe Sardar offers the following analysis:

“Marathas were very powerful in Nizam Shahi, Qutb Shahi and Adil Shahi. Gangavi, the founder of Nizam Shahi, who was converted to Islam, was the son of Bahirambhat Kulkarni, a Brahman. The father of Ahmednagar King too was a Hindu. Yusuf Adil Shah of Vijapur [Bijapur] had married a Maratha girl. Qasim Barid was the founder of the throne of Bidar kingdom. His son also had married Sabaji’s daughter. Owing to such relations and customs there was tolerance to Hindus and the Marathas were quite powerful in these kingdoms.”

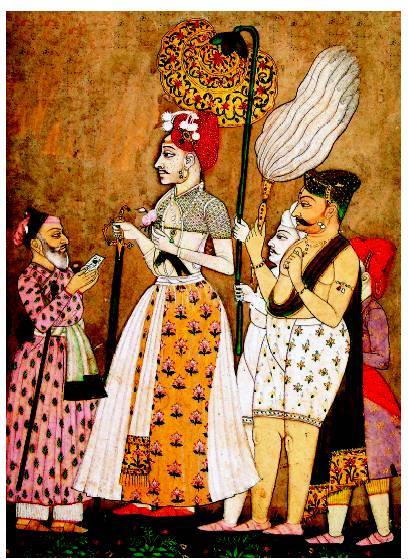

Yusuf Adil Shah of Vijapur [Bijapur]

In the same book, Parasnis quotes Justice Mahadev Govind Ranade:

“Hindus under the Southern Muslim kingdoms were encouraged by the kings (in many ways) and they were given many concessions and powers. This was because of a number of factors: alienation of the South Indian Muslims from the radical Muslims of the North, dominant position and a general goodwill of the Hindus in the Bahmani sultanate, the entry of Brahmans and Prabhus in the departments of Treasury and Tax Collection, entry of Marathi language in the administration because of them, the balance of forces resulting in Marathi warriors and officers getting promotions, the king’s court donning a deep imprint as a consequence of his marriage with Hindu girls, and deep affection of those converted to Islam for the people of their own caste.”

What does the name Hasan Gangu Bahmani, the founder of the Bahmani sultanate, tell us? A Muslim person called Hasan Jaffer had been working for a Brahman called Gangu. Later on he became a courtier of Tughlaq, the Emperor of Delhi. Gangu became the Emperor’s subedar in Maharashtra. He rebelled against the Emperor and founded his own throne in Maharashtra. As a sign of gratitude to and in memory of his former master he adopted a new name, half Hindu and half Muslim: Hasan Gangu. His own state was called Bahmani, i.e., related to Brahmans. If the relations between the Hindus and the Muslims had always been of extreme enmity, this would not have happened.

Ahmednagar fort

Hindu lords and Hindus remained loyal to Muslim kings, and the latter were tolerant to their subjects. If the subjects — whether Hindus or Muslims — threatened the state and if the state became endangered, the kings would become intolerant. What was important was not their being Hindus or Muslims, but the stability of the state.

“Marathas were very powerful in Nizam Shahi, Qutb Shahi and Adil Shahi. Gangavi, the founder of Nizam Shahi, who was converted to Islam, was the son of Bahirambhat Kulkarni, a Brahman. The father of Ahmednagar King too was a Hindu. Yusuf Adil Shah of Vijapur had married a Maratha girl. Qasim Barid was the founder of the throne of Bidar kingdom. His son also had married Sabaji’s daughter. Owing to such relations and customs there was tolerance to Hindus and the Marathas were quite powerful in these kingdoms.” —Dattatray Balwant Parasnis

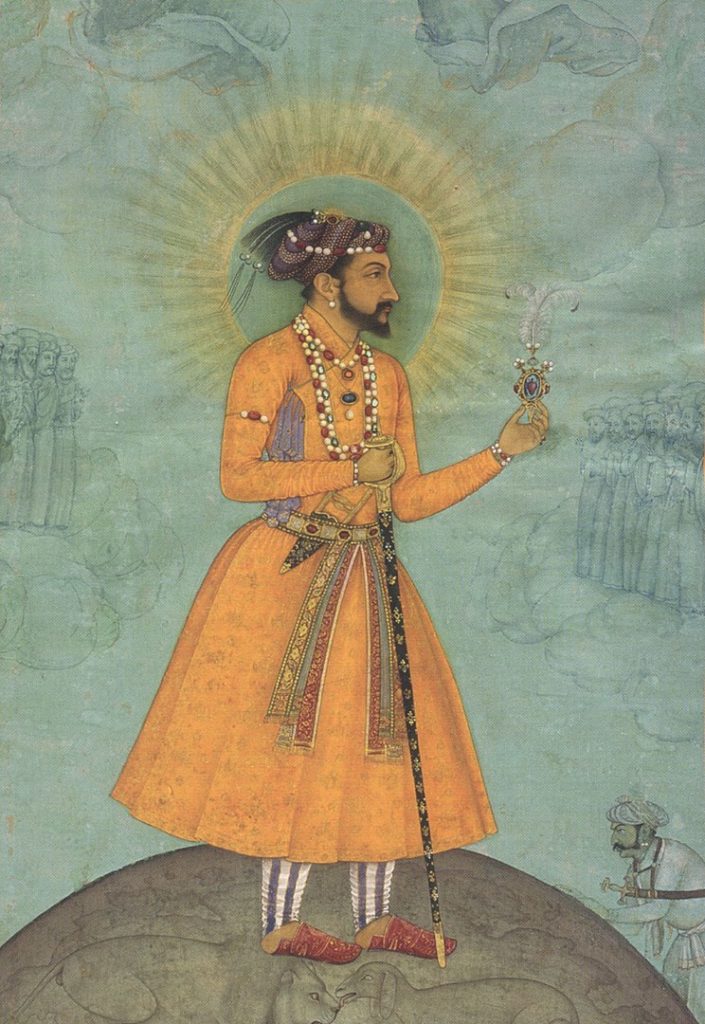

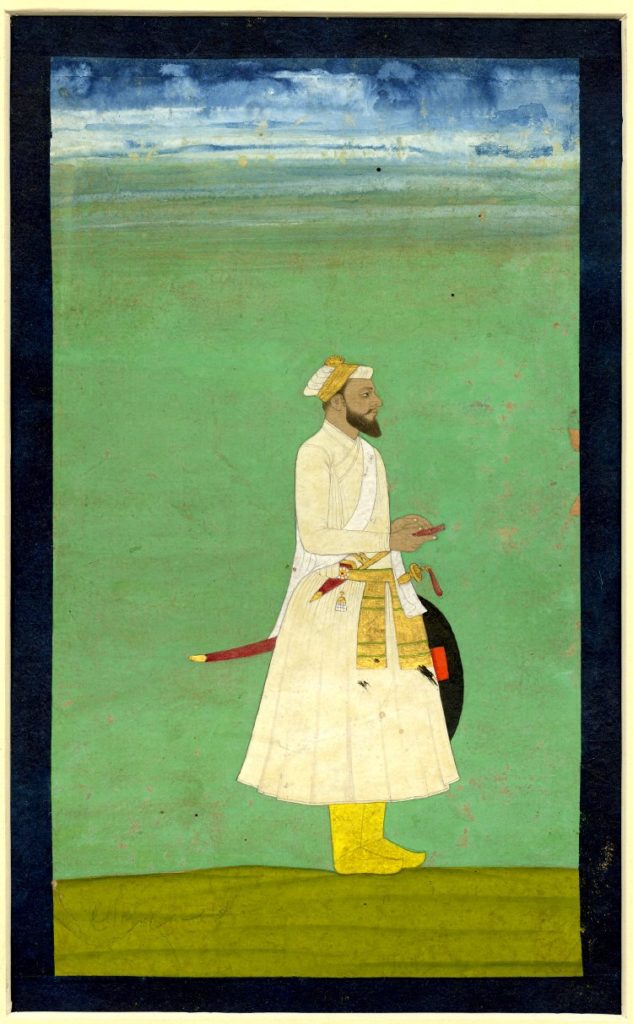

Shah Jahan, painted by Bichitr, c.1630, Chester Beatty Library

All the emperors of Delhi were not fundamentalist Muslims. This is an error of historical judgment. Akbar’s tolerance is well-known. He even tried to found a new syncretic religion called Din-e-Ilahi. In his times there was considerable cultural unity. Hindu Todar Mal, as revenue Minister, used his intelligence for the cause of a king who happened to be a Muslim. Jagannath Pandit, a high caste Brahman, was happily writing Sanskrit poetry in the court of Shah Jahan.

A story of Pandit Jagannath is quite well known. The Hindu king of Jaipur made great efforts to get this Hindu Pandit under his tutelage so as to add to the king’s status. Jagannath Pandit’s reply to his invitation is very revealing,

Only the Lord of Delhi or the Lord of the World has the might to fulfill my wishes. If any other king desires to do something for me it will be just enough for my hand to mouth existence.

The caste of the Lord of Delhi was not important. What was important was what he gave and how much he gave. Shah Jahan’s son Dara Shikoh was a Sanskrit scholar. He used to regularly meet with the scholars from Kashi. In this milieu, someone composed the Allopanishad — or the Allah Upanishad — on the lines of the well-known Upanishads such as the Chandogya Upanishad and Brihadaranyaka Upanishad. It was a sign of cultural complexity.

A scholar of the stature of Tryambak Shankar Shejwalkar argued that if Dara Shikoh, Aurangzeb’s elder brother, had ascended the throne rather than Aurangzeb, this continent would have come under one rule and would have become a very powerful country. In short, it can easily be seen that all the Muslim rulers were not the haters of the Hindus.

Todar Mal, Revenue Minister of Akbar

Shivaji had many Muslims working under him. They held very important positions in his army and administration. Many of them were appointed to very high and responsible posts.

Those who study the life and work of Shivaji cite the formation of his navy as an example of his foresight. The Konkan coastline is very long, and a well-equipped navy was essential for its defense. Shivaji installed such a naval force, with its leader being Darya Sarang Daulat Khan. He was a Muslim.

Shivaji’s personal bodyguard included a Muslim youth called Madari Mehtar. He was a trusted servant. Why should he, a Muslim, have helped Shivaji in his most dramatic and legendary escape from Agra? Would it have been possible if Shivaji had been a hater of Muslims?

Shivaji had many such Muslims in his employ. One of them was Kazi Hyder. After the battle of Saleri, Aurangzeb’s lieutenants in the South sent a Hindu Brahman ambassador so as to establish amicable relations with Shivaji. Shivaji in turn sent Kazi Hyder as his emissary. Thus a Muslim ruler had under him a Hindu ambassador and a Hindu ruler had a Muslim. If society were vertically split between the Hindu and Muslim communities this could not have happened.

Siddi Hilal was one such Muslim working for Shivaji. Shivaji defeated Rustum Zama and Fazal Khan near Raibaug in 1660. Siddi Hilal fought on Shivaji’s side. Adil Shah II’s uncle Siddi Jauhar came to lay siege against Shivaji at Panhala Fort that same year. Shivaji’s trusted aide, Netaji Palkar, used his armed detachments to dislodge the siege. Siddi Hilal and his son were at Netaji’s side at the time. Hilal’s son Siddi Wahwah was wounded and captured in this battle.

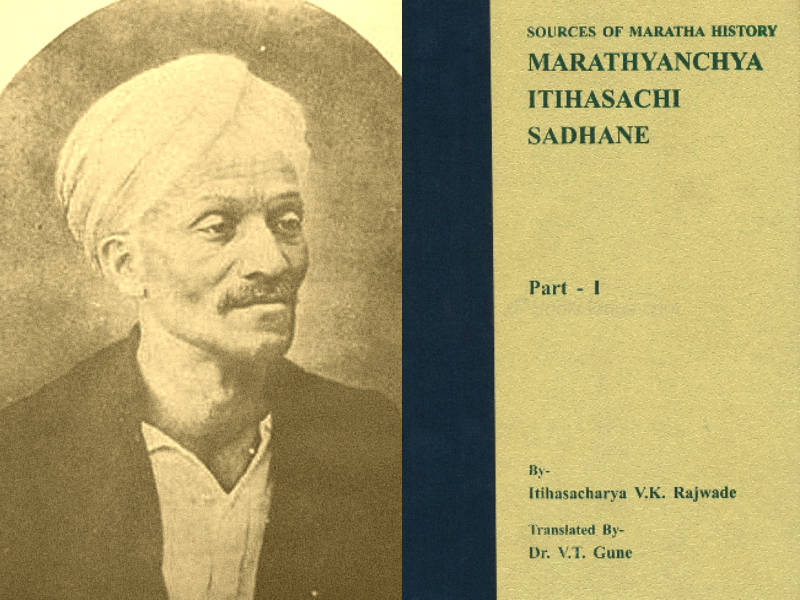

The Muslim chieftain Siddi Hilal, along with his son, fought for Shivaji, a Hindu, against a Muslim. Would this happen if the nature of wars at that time was communal, as a war between Hindus and Muslims? The chronicle Sabhasad Bakhar mentions the name of Shivaji’s lieutenant — Shama Khan. V.K. Rajwade points out in his Marathyanchya Itihasachi Sadhane (“Sources of Maratha History”) that Shivaji’s Sarnobat or chief of infantry was Noor Khan Beg. These were not isolated individuals. Muslim sardars worked for Shivaji along with the anonymous Muslim soldiers under them.

Evidence of Shivaji’s tolerance toward Muslims is found across the archives, deep in the chronicles of the time. Here is one example. Around 1648, about five hundred to seven hundred Pathans belonging to Vijapur army came to join Shivaji. Shivaji accepted the advice given to him at that time by Gomaji Naik Pansambal, his military advisor. Gomaji said, “These people have come hearing about your reputation. It will not be proper to turn them away. If you think that you should organize Hindus alone and will not be bothered about others, you will not succeed in establishing your rule. The one who wishes to establish rule must gather all the eighteen castes and the four varnas and assign to them their functions.” Shivaji had not yet established his ecumenical policy in 1648. He would base his policy on such advice. Grant Duff, in his History of the Marhattas (1830) mentions Gomaji Naik’s advice to Shivaji and then notes, “After this, Shivaji enlisted a large number of Muslims also in his army and this helped a great deal in founding his rule.”

V.K. Rajwade and his Marathyanchya Itihasachi Sadhane

Shivaji installed… a naval force, with its leader being Darya Sarang Daulat Khan… Shivaji’s personal bodyguard included a Muslim youth called Madari Mehtar. He was a trusted servant. Why should he, a Muslim, have helped Shivaji in his most dramatic and legendary escape from Agra? Would it have been possible if Shivaji had been a hater of Muslims? Shivaji had many such Muslims in his employ. One of them was Kazi Hyder. After the battle of Saleri, Aurangzeb’s lieutenants in the South sent a Hindu Brahman ambassador so as to establish amicable relations with Shivaji. Shivaji in turn sent Kazi Hyder as his emissary… Siddi Hilal was one such Muslim working for Shivaji. Shivaji defeated Rustum Zama and Fazal Khan near Raibaug in 1660. Siddi Hilal fought on Shivaji’s side. Adil Shah II’s uncle Siddi Jauhar came to lay siege against Shivaji at Panhala Fort that same year. Shivaji’s trusted aide, Netaji Palkar, used his armed detachments to dislodge the siege. Siddi Hilal and his son were at Netaji’s side at the time. Hilal’s son Siddi Wahwah was wounded and captured in this battle… The chronicle Sabhasad Bakhar mentions the name of Shivaji’s lieutenant — Shama Khan. V.K. Rajwade points out in his Marathyanchya Itihasachi Sadhane (“Sources of Maratha History”) that Shivaji’s Sarnobat or chief of infantry was Noor Khan Beg.

Shivaji’s lieutenants, soldiers and chieftains were not Hindus alone. They were Muslims as well. If Shivaji had undertaken the task of eliminating Islam, these Muslims would certainly not have joined him. Shivaji had set out to demolish the despotic and exploitative rule of Muslim rulers. He had set out to bring in a rule that cared for the ryots. This is the reason why the Muslims too joined him in his cause.

The question of religion was not the main question. The main question was of the state.

Not loyalty to religion, but loyalty to the state, to a master was more important.

Just as there were Muslim Sardars and soldiers working with Shivaji, there were numerous Hindu Sardars and soldiers serving Muslim kings and emperors.

In fact Shivaji’s own father, Shahaji, was an influential Sardar working for Adil Shah, Vijapur’s Muslim ruler. Shahaji’s father-in-law, Lakhuji Jadhav, was the Nizam’s Mansabdar in Maharashtra. Adil Shahi’s other Mansabdars included More of Javali, Nimbalkar of Phaltan, Khem Sawant of Sawantwadi and Suryarao Shringarpure of Shringarpur.

Mirza Raja Jai Singh, a high caste Rajput Hindu, came on behalf of the Mughal emperor to defeat Shivaji, force him to sign a humiliating agreement, took him to Agra, where he arrested him and his son Sambhaji. All he was doing was to serve honourably under a Mughal emperor. When Mirza Raja Jai Singh invaded Shivaji’s dominion he had several Hindu Sardars under him. They were Jats, Marathas, Rajputs including Raja Rai Singh Sisodiya, Sujan Singh Bundela, Hari Bhan Gaur, Uday Bhan Gaur, Sher Singh Rathod, Chaturbhuj Chauhan, Mitra Sen, Indra Man Bundela, Baji Chandrarao, Govind Rao, etc.

Tanaji Malusare, a lieutenant of Shivaji, died in action while capturing Fort Kondana. This fort was renamed as Simhagadh to commemorate Tanaji’s heroic sacrifice. The officer in charge of Fort Kondana was a Hindu Rajput, Uday Bhanu, and he was a lieutenant of a Muslim Emperor.

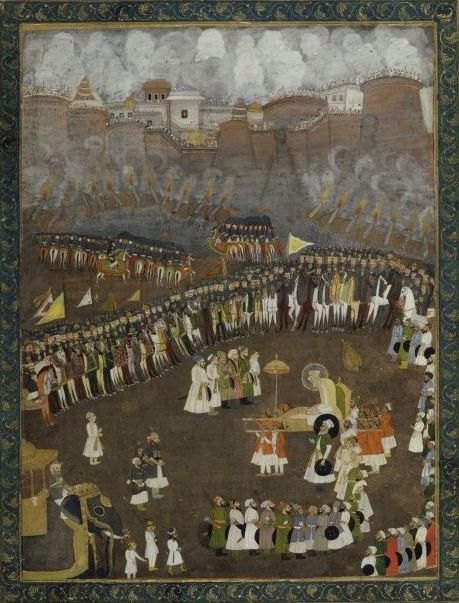

Aurangzeb leading the Mughal Army during the Battle of Satara

There were about 500 Sardars holding different mansabs under Akbar. Out of those 22.5 per cent were Hindus. In Shah Jahan’s empire, the ratio stood at 22.4 per cent. Aurangzeb is supposed to be the most fanatic of all the Muslim rulers. When he took over the empire, Hindus accounted for 21.6 per cent of the Mansabdars. When his reign ended, this figure rose to 31.6 per cent. It was Aurangzeb who had appointed Raja Jaswant Singh, a Hindu Rajput, as the Subedar (governor) of the Deccan. Aurangzeb’s first Minister too was a Hindu, Raghunath Das. He was a Rajput and yet fought against Rajputs on behalf of Aurangzeb. One of Rana Pratap Singh’s generals was Hakim Khan Soor, a Muslim. The Chief of the Peshwa’s artillery in the battle of Panipat was Ibrahim Khan Gardi.

The Hindus who served Muslim Kings with loyalty and occasionally fought against them were not castigated as sinners or religious renegades. They were not called anti-Hindu or pro-Muslim. Loyalty to the Master, rather than to religion, was more important in those times.

In ancient or medieval India wars were not waged on the grounds of religion. The main motive behind wars was to capture or to strengthen power. It was true that religion was temporarily used to support the main purpose. But it never was the sole or main motive.

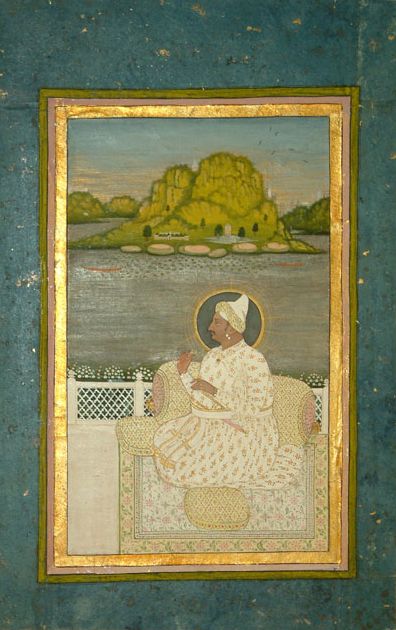

Sadashivrao Peshwa with Ibrahim Khan Gardi

It is true that there were several Muslims working under Shivaji and many more working under Muslim rulers. Similarly it is revealing to see who fought against whom. It becomes very clear that these wars were not Hindus versus Muslims as such. Muslim rulers fought amongst themselves.

Babar, a Muslim, became the Emperor of Delhi by defeating Sultan Ibrahim Khan Lodhi, a Muslim. Babar founded the Mughal dynasty. Both Sher Shah and Humayun were Muslims yet they fought a bitter war against each other. The rulers of Bijapur and Golconda were both Muslims. Aurangzeb fought a protracted war against these so-called Muslim rules. This shows that what was important was not religion but power. If at all religion had any importance it was secondary. The primary concern was political power.

The legendary battle of Haldi was fought between Rana Pratap and Akbar. This battle had a great importance for Rana Pratap in particular, and for Rajputs and Rajasthan in general. But can this battle of Haldi be described, by any stretch of imagination, as a battle between Hindus and Muslims?

Statue of Hakim Khan Soor, Udaipur

Akbar’s army was led by the Rajput Man Singh. That army consisted of 60,000 Mughal troops and 40,000 Rajput troops. Whereas Rana Pratap’s army had 40,000 Rajput soldiers, it consisted of a large division of Pathans under Hakim Khan Soor. It also had a cavalry under a Pathan called Taj Khan. The chief of Rana Pratap’s artillery too was a Muslim Sardar.

In fact Shivaji’s own father, Shahaji, was an influential Sardar working for Adil Shah, Vijapur’s Muslim ruler. Shahaji’s father-in-law, Lakhuji Jadhav, was the Nizam’s Mansabdar in Maharashtra. Adil Shahi’s other Mansabdars included More of Javali, Nimbalkar of Phaltan, Khem Sawant of Sawantwadi and Suryarao Shringarpure of Shringarpur.

Mirza Raja Jai Singh, a high caste Rajput Hindu, came on behalf of the Mughal emperor to defeat Shivaji, force him to sign a humiliating agreement, took him to Agra, where he arrested him and his son Sambhaji. All he was doing was to serve honourably under a Mughal emperor. When Mirza Raja Jai Singh invaded Shivaji’s dominion he had several Hindu Sardars under him. They were Jats, Marathas, Rajputs including Raja Rai Singh Sisodiya, Sujan Singh Bundela, Hari Bhan Gaur, Uday Bhan Gaur, Sher Singh Rathod, Chaturbhuj Chauhan, Mitra Sen, Indra Man Bundela, Baji Chandrarao, Govind Rao, etc.

Tanaji Malusare, a lieutenant of Shivaji, died in action while capturing Fort Kondana. This fort was renamed as Simhagadh to commemorate Tanaji’s heroic sacrifice. The officer in charge of Fort Kondana was a Hindu Rajput, Uday Bhanu, and he was a lieutenant of a Muslim Emperor.

Guru Govind Singh too fought against the central Muslim power. His army also had, along with Sikhs, thousands of Muslims. After Aurangzeb died, there was a fierce struggle for succession among his heirs. Guru Govind Singh helped Bahadur Shah in that feud.

The religious basis behind the uprising by the Jats, Rajputs, Marathas and Sikhs was flimsy. Their uprisings were basically against despotic central rule. The soldiers and noblemen were loyal to their masters irrespective of religion. Neither Hindu nationalism nor the mission of spreading Islam inspired the standing armies of the feudal period. To serve a master as long as he fed, was the general social practice.

The refrain of fundamentalist Hindu organisations is commonly heard: “The Muslim kings were cruel and barbaric. They destroyed and desecrated temples. They attacked the Hindu religion. Therefore, all the Muslims are necessarily anti-Hindu. And, since they are anti-Hindu, the Hindus also must have to be anti-Muslim.”

Just as Hindu organisations use this kind of argument, the Muslim organisations too use a similar argument.

They tell their followers, “Hindu religion is the religion of Kafirs. What our forefathers did to destroy it was quite correct. If possible, we should also do the same. We should be at least against the Hindus.” The organisations tell their followers to regret the loss of their rule. They use such language to organise themselves on a religious basis.

It is true that the invading Muslim armies, while expanding their rule, looted and destroyed temples. But this is not the whole truth. It is a half-truth. The tribe-like armies of Arabs, Turks and Afghans were not regularly paid. It was an accepted practice for them to loot and keep their share with them as wage. Certain Hindu temples used to be very rich. While looting, the invaders destroyed some temples and divided the booty.

These armies would not care to touch the temples situated atop mountain peaks or deep inside the ravines. What could be the reason for this? The main purpose was to loot the wealth in temples and not to destroy them.

Looting wealth was the prime concern; religion was secondary. Destruction of temples was a means of achieving this purpose. A major portion of this loot went to the king. It was the chief source of the king’s revenue.

A second motive of attacking temples was to discourage the people who live in areas surrounding the temples. The violence was intended to create fear among them, to break their fighting spirit. People believed in religion and in god. It was easy for the invaders to make them believe that those who had looted god would easily loot them too. “Such a powerful god could not do anything; what can we mortals do?” This kind of helplessness and panic would spread all over. This would make it easy for the invaders to conquer the enemy. In Shivaji’s time, temples were not centers of religion alone. They were centers of wealth, of power and status. There was another benefit of looting temples. The invaders claimed that they were breaking the temples of kafirs, that they were destroying their religion. This worked as a camouflage to hide the real thing, the loot of wealth. This would help in garnering support of the priestly elites, mullahs and maulavis, as a device to get the support of the Muslim masses. Religion was used as a ruse to cover foul deeds.

The tribe-like armies of Arabs, Turks and Afghans were not regularly paid. It was an accepted practice for them to loot and keep their share with them as wage. Certain Hindu temples used to be very rich. While looting, the invaders destroyed some temples and divided the booty… The invaders claimed that they were breaking the temples of kafirs, that they were destroying their religion. This worked as a camouflage to hide the real thing, the loot of wealth. This would help in garnering support of the priestly elites, mullahs and maulavis, as a device to get the support of the Muslim masses. Religion was used as a ruse to cover foul deeds.

The rulers who initially looted and demolished temples on their way to assuming power, would, once the enemy kingdom was conquered and their own rule was stabilized, award endowments and grants to those very temples. There are numerous such examples. Aurangzeb, who is known as a religious fanatic, destroyed many temples while invading kingdoms to expand his own empire. But the same Aurangzeb donated money to temples. He awarded two hundred villages to the Jagannath temple of Ahmedabad. He donated money to Hindu temples at Mathura and Benaras too. There are differences among scholars as to whether the Adil Shahi commander and Shivaji’s adversary, Afzal Khan, broke the idols in Pandharpur and Tuljapur temples. Some believe he did. Tryambak Shankar Shejwalkar, however, suggests otherwise. He writes that the idols in place today in these temples are quite ancient. Whatever the truth, it is recorded in the chronicles that Afzal Khan, while camping at Wai before launching his assault on Shivaji at Pratapgadh, not only continued the traditional rights of Brahman priests but also awarded new ones. Moreover, can we forget that when Afzal Khan supposedly destroyed the Bhavani temple at Tuljapur, he was accompanied by Pilaji Mohite, Shankarraoji Mohite, Kalyanrao Yadav, Naikji Sarate, Nagoji Pandhare, Prataprao More, Zunjarrao Ghatge, Kate, Baji Ghorpade and Sambhajirao Bhonsle. It is well known that Goddess Sharada temple at Shringeri was damaged while the Marathas looted it in 1791 and the Muslim King Tipu Sultan restored it later.

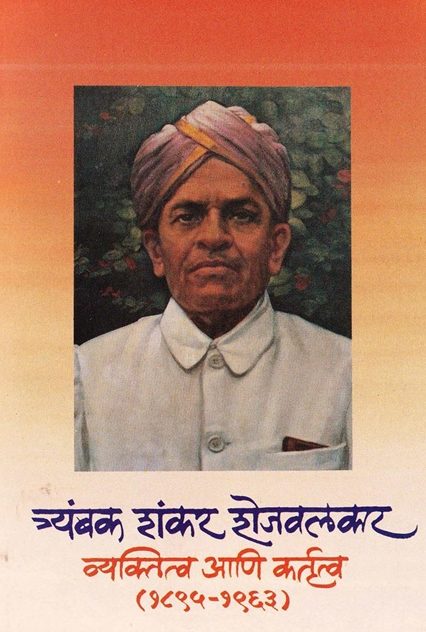

Tryambak Shankar Shejwalkar

Why was money donated to temples after a rule was stabilized? It was done to appease the sentiments of the Hindus and prevent any rebellion against the new rulers. Because of this, the Muslim rulers encouraged such donations.

Political power was the cause for looting and demolishing temples. It was the motivation of political power, once more, that led to the donations of money and property toward the repair of destroyed temples and the construction of new ones.

Political power was the cause for looting and demolishing temples. It was the motivation of political power, once more, that led to the donations of money and property toward the repair of destroyed temples and the construction of new ones.

Mohammed bin Tughlaq

Muslim kings were not alone in their loot of temples. Hindu kings also looted temples for their wealth.

Chronicles such as Kalhana’s Rajatarangini tell us that Harsha Dev, king of Kashmir, used to loot Hindu temples. He would melt idols for their metals. Harsha would even desecrate the idols by sprinkling them with human waste and urine before melting. What we do not find in these chronicles is evidence of communal riots having taken place because of the desecration of these idols by Harsha. It is telling that the revenue department of Harsha’s administration had a section called Devotpatan, Demolition of Gods.

If the Muslims started being a hindrance and a nuisance to the Muslim rule, the rulers would not hesitate to harass them in spite of the Mullahs and Maulavis. Marathi bakhars accuse Mohammed bin Tughlaq of massacring Mullahs and Sayyeds. Some historical accounts describe the fear amongst Mullahs of Emperor Jahangir. When he approached, some would hide.

What is the conclusion of all this? More important for the rulers of that era was their power, not their religion.

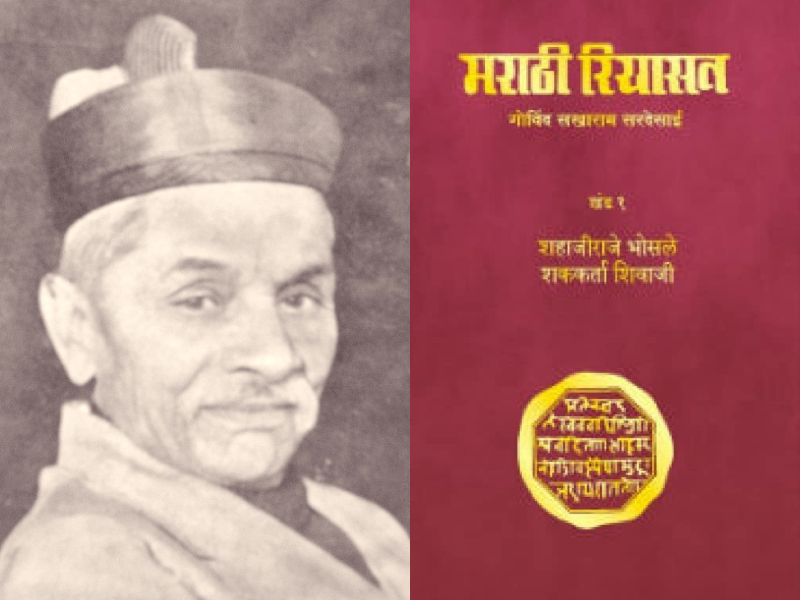

Shivaji fought several big and small wars to found his kingdom. The rulers before him in the area were mainly Muslims. He waged wars against them. At the same time, Shivaji had to fight the Marathas as well. His was not a war against Islam, but a war for power. In Marathi Riyasat, Riyasatkar Sardesai writes, “The war against Vijapurkars did not mean the war between Hindus and Muslims. It could not have acquired such character.” There are meticulously kept historical records about this. It is not right to ignore them.

Riyasatkar Sardesai and his Marathi Riyasat

Shivaji faced an enormous challenge from powerful Maratha noblemen who served the Vijapurkars, such as Mohite, Ghorpade, More, Sawant, Dalavi, Surve, and Nimbalkar. Riyasatkar Sardesai, Krisnajee Anant Sabhasad (who wrote a bakhar for Shivaji), Grant Duff and Parasnis list the names of great and powerful Maratha noblemen who opposed Shivaji. They did not respect Shivaji and challenged his authority. Why were these and other such Hindu Maratha noblemen against Shivaji? They were all Hindus. They observed their religion with great faith. If Shivaji had undertaken the cause of protecting the Hindu religion — a Dharmakarya — why should all these Hindu noblemen have opposed him? Sardesai writes, “They feared to lose what they possessed.” What did they possess? Grant Duff describes Shivaji as a destroyer. What did he destroy? “In the regions that he won from the Vijapurkars, Shivaji replaced the old system of monopoly in tax collection with the collection of revenue based on evaluation of yields of crops every year.” This makes Shivaji’s destruction clear. Duff was angry that Shivaji had destroyed the monopoly system. But Capon’s ethical judgment could not help itself, “It was possibly beneficial to the people.” It was obvious who benefitted from Shivaji and who was disenfranchised.

The chief Maratha Hindu noblemen (Ghatge, Khandagale, Baji Ghorpade, Baji Mohite, Nimbalkar, Dabir, More, Bandal Sawant, Surve, Khopade, Pandhare, the Desais of Konkan and the Deshmukhs of Maval) all opposed Shivaji because of their vested interests. Shivaji’s close relations — Vyankoji Bhonsle and Mambaji Bhonsle as well as Jagdevrao Jadhav and Rathoji Mane — stood against him. It is no surprise that when Shaista Khan invaded Shivaji’s dominion from the north, Hindu noblemen accompanied him. Among the Maratha noblemen who joined Shaista Khan, we number Sakhaji Gaikwad, Dinkarrao Kakade, Rambhajirao Pawar, Sarjerao Ghatge, Kamlojirao Kakade, Jaswantrao Kakade. Tryambkrao Khandagale, Kanakojirao Gade, Antajirao and Dattajirao Khandagale. More surprising and painful is the fact that Shivaji’s own blood relations, Tryambakraoji, Jivajirao, Balajiraje and Parasojiraje Bhonsle were with the Mughal warlord, Shaista Khan. This Mughal army included Dattajiraje and Rustumrao Jadhav of Sindkhed. These Jadhavs were from Jijabai’s family. Krishnaji Kalbhor of Loni had joined Shaista Khan with the hope of obtaining the fiefdom of Pune. Shaista Khan confiscated the Deshmukhi from Shitole and awarded it to Kalbhor. Balajirao Honap lived near Lal Mahal in Pune. He had spent some time of his life under the protection of the umbrella of the Swaraj. But he felt more affinity to Shaista Khan than to Shivaji. Such were the Hindus. So much for their religiously-defined identity! Their loyalty was to their fief. It is clear as daylight. The only exception was Kanhoji Jedhe.

Shivaji held a very clear, and very bitter, view of these lords and noblemen. His Prime Minister has said, “They have a natural predisposition, a natural hunger to become powerful, to rob others. They become friendly with the enemy on the eve of the latter’s invasion with the hope of obtaining a fief. They meet the enemy on their own, without invitation. They pass on the secret information and abet the enemy’s entry into our state. They kill the nation.” The fief was all. Their religion was marginal. They burned for their fief, not for their religion.

Shaista Khan

Riyasatkar Sardesai, Krisnajee Anant Sabhasad (who wrote a bakhar for Shivaji), Grant Duff and Parasnis list the names of great and powerful Maratha noblemen who opposed Shivaji. They did not respect Shivaji and challenged his authority. Why were these and other such Hindu Maratha noblemen against Shivaji? … Sardesai writes, “They feared to lose what they possessed.” What did they possess? Grant Duff describes Shivaji as a destroyer. What did he destroy? “In the regions that he won from the Vijapurkars, Shivaji replaced the old system of monopoly in tax collection with the collection of revenue based on evaluation of yields of crops every year.”

Grant Duff and his History of the Marhattas

Shivaji was not a non-believer or an atheist. He did not declare his state to be secular. Shivaji was a Hindu. He had faith in religion. He worshipped gods, goddesses and saints as well as donated wealth to temples.

But was he against Islam? If he had faith in his religion, did it mean that he hated Islam? Was it his intention or effort to Hinduise the Muslims? Was he trying to Maharashtrianise them?

If we wish to be faithful to history, the answers to these questions are plainly negative.

Shivaji had looted Surat on two occasions. The detailed accounts of both are well recorded. There are also records of the looting of the market at Junnar and other places. However, is there the tiniest of evidence that he demolished a single mosque? Or is there any evidence of him having constructed a temple in place of a mosque, which was supposed to have been built by demolishing a temple? Not at all. On the contrary, there are records that he donated money and land to mosques. Sabhasad’s Bakhar notes, “There were places of worship all over. Proper arrangement of their worship and care was made. He also looked after the arrangements in pirs and mosques.”

What was true of the mosques was also true of the Muslim sadhus and saints. Shivaji and his contemporary Marathas and Hindus worshipped and donated money to dargahs. They respected Muslim sadhus, pirs and fakirs. Shivaji had many gurus. They included a Muslim saint called Yakut Baba.

Shivaji’s tolerance for Muslim religion is recorded in many ways in historical documents. Khafi Khan’s Muntakhabu-l Lubab notes, “Shivaji had made a strict rule that wherever his soldiers went they were not to harm mosques, the Quran or women. If he found a volume of Quran, he would show respect to it and hand it over to his Muslim servant. If any helpless Hindu or Muslim were found, Shivaji would personally look after them until their relatives came to take them.” Shivaji’s chief justice, Raghunath Pandit Rao, in a letter of 2nd November 1669 writes, “Shrimant Mararaj has ordained that everybody is free to follow his religion and nobody is allowed to disturb it.”

Those who try to appropriate Shivaji for their narrow purposes will have to answer for the historical record. If there are any buyers for their hatred for Islam they should sell it on their own merit. They should not sell their commodity in Shivaji’s name. They should not sell that commodity under the brand of Shivaji.

At the same time, Muslims should not equate Shivaji with his image created by these so-called Shivabhaktas. They should look at history; they should appreciate his attitude to Islam. Only then should they form their opinion.

Shivaji was Hindu and he believed in his religion. But, as the king, he did not discriminate against his people on the basis of religion. He did not treat Hindus in one way and Muslims in another. He did not discriminate against Muslims because they belonged to another religion. Both Hindus and Muslims must understand this.

There were two kinds of Islamic kings. Some, like Akbar, were tolerant to Hindus. Some, like Aurangzeb, were intolerant. Aurangzeb levied the jaziya tax at the behest of the mullahs and the maulvis. There was an uprising against this tax. Shivaji wrote a letter, in Persian, to Aurangzeb about this. The letter gives a graphic idea of how Shivaji looked at various religions. Shivaji writes that levying the jaziya tax on the poor and helpless populace is against the basic tenets of Mughal rule. Aurangzeb’s great-grandfather Akbar had ruled for fifty-two years. He treated everyone with justice. The people therefore honored him as Jagatguru. Jahangir and Shah Jahan continued his policy. All of them became famous all over the world for this. These emperors could easily have collected the jaziya tax, but they did not do so. That is why they could become so rich and so honoured. Their empires grew. But in Aurangzeb’s rule both Hindu and Muslim soldiers were unhappy. The price of grains went up. It was not reasonable, as far as Shivaji was concerned, for the empire to collect the jaziya tax from poor Brahmans, Jogis, Bairagis, Jain Sadhus and Sanyasis. Such an act would ultimately only discredit the Mughal dynasty. Shivaji writes, “The Quran is the word of God himself. It is a heavenly Book. It calls God the ‘God of the entire World.’ It does not call him the God of Muslims alone. This is because both Hindus and Muslims are one before him. When the Muslims pray in the mosques, they in fact pray to Bhagwan. And Hindus too do the same when they toll the bell in a temple. To oppress a religion is therefore to pronounce enmity with God.”

Shivaji therefore appeals to Aurangzeb not to ignore reason. The Sultan of Gujarat had earlier sacrificed reason. But he had to pay for it. The Emperor would have to pay similarly. “Any inflammable matter burns out if it comes in contact with fire. Similarly, any rule perishes in people’s discontent. The fire of rebellion, born of the torture of innocents, can burn the whole kingdom faster than any fire. The Emperor therefore should not discriminate against any religious creed and oppress them. People, like insects, are harmless. However, if Hindu people are subjected to misery, your empire will be reduced to ashes in the fire of their anger.”

Shivaji has propounded an important principle for us Indians here. Akbar and other emperors did not subject the Indian people to religious cruelty and oppression. Because of such religious tolerance Akbar was hailed as Jagatguru. But Aurangzeb, by taxing poor people, acted against the principles of Islam. If the Quran is the word of God, for God Hindus and Muslims are not different. If the king harms people, they will destroy him, however powerful he might be.

In the context of his time, Shivaji’s thoughts and his policy were unique and unparalleled. Religion had a deep impact upon people’s life. But Shivaji taught us that other religions are as great as one’s own religion, and that though the forms of worship in each religion are different their goal is one. The thoughts of Akbar, Dara Shikoh and Ibrahim Adil Shah were not different from this.

Shivaji was religious. He was proud of being a Hindu. He awarded large gifts to temples and Brahmans. All this is true. However, his pride in his religion was not based on the hatred for other religions. He never thought that he could not be a great Hindu unless he hated Muslims. Even in medieval times his faith in religion was rational.

Shivaji had looted Surat on two occasions. The detailed accounts of both are well recorded. There are also records of the looting of the market at Junnar and other places. However, is there the tiniest of evidence that he demolished a single mosque? Or is there any evidence of him having constructed a temple in place of a mosque, which was supposed to have been built by demolishing a temple? Not at all. On the contrary, there are records that he donated money and land to mosques. Sabhasad’s Bakhar notes, “There were places of worship all over. Proper arrangement of their worship and care was made. He also looked after the arrangements in pirs and mosques.”

What was true of the mosques was also true of the Muslim sadhus and saints. Shivaji and his contemporary Marathas and Hindus worshipped and donated money to dargahs. They respected Muslim sadhus, pirs and fakirs. Shivaji had many gurus. They included a Muslim saint called Yakut Baba.

Shivaji’s tolerance for Muslim religion is recorded in many ways in historical documents. Khafi Khan’s Muntakhabu-l Lubab notes, “Shivaji had made a strict rule that wherever his soldiers went they were not to harm mosques, the Quran or women. If he found a volume of Quran, he would show respect to it and hand it over to his Muslim servant. If any helpless Hindu or Muslim were found, Shivaji would personally look after them until their relatives came to take them.” Shivaji’s chief justice, Raghunath Pandit Rao, in a letter of 2nd November 1669 writes, “Shrimant Mararaj has ordained that everybody is free to follow his religion and nobody is allowed to disturb it.”

Circa 1657

From Shivaji, true to His Words, to Aurangzeb

I had to leave, due to a quirk of Destiny, without a

farewell. . . .

After our return we heard that the Emperor’s treasury has become empty. It is also learnt that the government of the Empire is running its daily administration by collecting jaziya from Hindus. In fact, formerly, Emperor Akbar ruled with great equanimity for fifty-two years. Therefore, apart from the Daudis and Mohammedis, the religious practices of Hindus such as Brahmans and Shevades were protected. The Emperor helped these religions. Therefore, he was hailed as a Jagatguru. This ensured success to him in all the endeavours that he undertook. He conquered land after land. After him Emperor Nuruddin Jehangir ruled for twenty-two years with the blessings of the Almighty and went to the heaven. Shah Jahan too ruled for thirty-two years. They were brave Emperors and earned great respect. They established many new practices. They too were capable of levying the jaziya. But all, small and big, follow their own religion and are God’s children. In spite of all this they never resorted to injustice. Even now all sing in their praise. All, big and small, feel blessed by them. One reaps as one sows. Those Emperors had always their eyes fixed on people’s welfare. Now, under your rule, you have lost many forts and provinces. The rest are also likely to be lost. This is because you do not spare in doing everything that is base. The ryots have become miserable. None of the revenue divisions is paying you even one per cent of its total produce. Even the Emperor and his progeny are living in impoverished condition. It is therefore not hard to imagine under what conditions the other lords must be living. In sum, soldiers are frustrated, merchants are howling and Muslims are crying. Hindus burn from within. Several cannot get sufficient food to eat. Is this governance? Over and above all this, there is jaziya. The word has spread east and west, far and wide, that the Emperor of Hindustan levies jaziya on Fakirs, Brahmans, Shevades, Jogis, Sanyasis, Bairagis, poor and miserable. The Emperor takes pride in this and even surpasses Emperor timur’s deeds. The Quran is a Heavenly Book. It is God’s utterance. It commands that God belongs to all Muslims and, in fact, the entire world. Good or bad, both are God’s creation. In masjids, it is He who is prayed. In temples, it is He for whom the bells are tolled. to oppose anyone’s religion is like forsaking one’s own religion. It is wiping out what God wrote; it is to blame God Himself. You should therefore discriminate between good and bad. This is all the more necessary as defaming matter is like defaming the Creator of matter Himself. Jaziya can in no way be called just. Sultan Ahmed Gujrathi ruled in this manner and soon bit dust. Those who are made to suffer injustice finally blow out smoke through their mouth hotter than even the fire that burns the Devil. The perpetrator burns out faster than the Devil himself. So it is advisable that the soiled mind is washed sooner than later. Above all this, if you feel that the true religion is in persecuting Hindus, you should first collect the jaziya from Raja Jai Singh. Others will easily follow suit. The poor are like ants and gnats. There is nothing heroic in persecuting them. It is very surprising to see that even loyal ones blatantly try to hide fire under hay. So be it. Let the Sun of the Empire shine bright from the Eastern Mountains of Heroism.

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of LeftWord Books. You can buy Who Was Shivaji? here.

Govind Pansare was one of Maharashtra’s leading Communist leaders and public intellectuals. Starting out in the Rashtra Seva Dal, he joined the Communist Party of India in 1952, and went on to become its Maharashtra State Secretary, as well as a member of the party’s National Executive. An active trade unionist, he was also a labour lawyer. Pansare took part in many social reform movements in Maharashtra, including movements against superstition and for inter-caste marriage. He was a prolific writer and speaker, and authored at least ten books, including the bestselling Shivaji Kon Hota? or Who Was Shivaji? You can read more about his life and work here and here.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1943-1945 | |

|

1943-1945 |

| Origin Of The Azad Hind Fauj | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Sir, I am so fortunate that I have found this article on the internet while searching for material for my studies. I think every Indian should read this article and learn from it.

Such a beautifully written article. no words to appreciate this article, sir.

just phenomenal

A very interesting article supported by evidence from various credible sources. Goes against the rewriting of history happening now.