53 years ago, around this time, a struggle whose ideas and actions continue to bear great influence was born. Indian History Collective’s first in a series on the Naxalite Movement.

In the 1960s India was free from British rule but still shackled by colonial era land laws that created a system such that, as per the 1971 census, 60% of the population was landless and the lion’s share of land was owned by the richest 4%. It was in this context that a peasant uprising in a small village in North Bengal, called Naxalbari, became the epicentre of armed struggle against the government and the establishment for the rights of the poorest of poor – in this case tribal sharecroppers.

The movement was crushed by the state machinery within months but had found sympathisers outside of North Bengal, particularly in the state capital of Calcutta. Its ideas were to spread even further— to other parts of the country, and are seeded in violent strife in tribal belts in India to date.

The Indian History Collective will bring to you writings that help understand and contextualise this decades long struggle and its various ramifications, starting with this introduction of the events in Naxalbari that started it all, excerpted from, ‘In The Wake of Naxalbari’ by Sumanta Banerjee.

Covering an area Of 300 square miles, Naxalbari, Phansidwa, and Kharibari were the three important bases in the Darjeeling district, where the peasants were mainly comprised of the tribals – Santhals, Oraons, and Rajbanshis.

Exploited by the jotedars under the adhiar system they were mainly employed on contractual basis. The landlords provided seeds, ploughs and bullocks, in exchange for which they cultivated the plots and got a share of the crops. Disputes over shares leading to evictions of the peasants were quite common, and increased with the coming to office of the United Front. To quote Harikrishna Konar, “No sooner than the United Front had formed the government, the jotedars and other reactionary elements began to spread the lie that the United Front government would rob small and medium owners of their land.” The first response of all the land owners — whether big or small — to such a propaganda was to get rid immediately of the sharecroppers who worked on their plots and who might, they were afraid, demand possession of these blocks. As a result, there was a spate of evictions in the countryside. In fact, right in Naxalbari, just after the United Front came to office, a sharecropper, Bigul Kishan, was evicted by a landlord in spite of a court judgment which favoured the sharecropper. The landlord and his gang attacked Bigul Kishan and got away with it. If anything else was needed, the incident coming fast on the heels of the United Front’s assumption of office, opened the eyes of the peasantry to the futility of expecting the coalition government to help them.

There was also a considerable number of workers in the tea gardens, most of whom were also tribals who worked as sharecroppers on the tea Garden owners’ surplus land. Used for Paddy cultivation, these lands were shown as tea Gardens to escape the ceiling on paddy lands. The sharecropper cum plantation workers were often retrenched by the employers, and they were thrown out of their homes. The CPI (M) dissidents wanted to draw in the tea garden workers into the peasants’ struggle. Kanu Sanyal claimed later that tea garden workers armed themselves and participated in every struggle from May 1967, which “helped the tea garden workers to come out from the mire of simple trade unionism and economicism.”

Naxalbari had a strategic importance too. A look at the map of West Bengal would reveal that the northern tip of the state has only a slender and vulnerable connection with the rest of India, through the Naxalbari neck. The neck is sandwiched between Nepal on the west and then East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) on the east. Between Naxalbari and Nepal flows the Mechi river, which in winter, can be crossed on foot. All these conditions render the area ideal for rebel activities, providing them with an opportunity to set up a liberated base area for some time, and with an escape route to foreign countries if things became too hot.

In fact, right in Naxalbari, just after the United Front came to office, a sharecropper, Bigul Kishan, was evicted by a landlord in spite of a court judgment which favoured the sharecropper. The landlord and his gang attacked Bigul Kishan and got away with it.

THE MAIN EVENTS

The Siliguri subdivision peasants’ conference proved to be a great success. The peasants, quickened and strengthened by their earlier militant struggles, looked forward expectantly. Faces, deadened and dulled with the grinding routine of labor on the jotedars’ fields in sun and rain, glowed with hope and understanding. According to Kanu Sanyal’s later claims, from March 1967 to April 1967, all the villagers were organized. From 15,000 to 20,000 peasants were enrolled as full-time activists. Peasants’ committees were formed in every village and they were transformed into armed guards. They soon occupied land in the name of the peasants’ committees, burnt all land records which had been used to cheat them of their dues, cancelled all hypothecary debts, passed death sentences on oppressive landlords, formed armed bands by looting guns from the landlords, armed themselves with conventional weapons, like bows, arrows and spears, and set up a parallel administration to look after the villages.

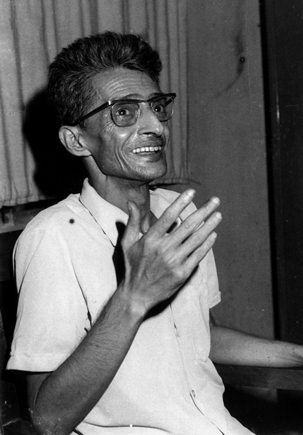

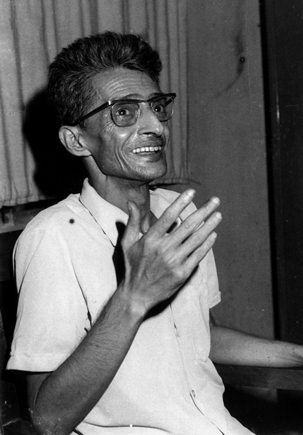

Charu Mazumdar addressed a meeting of party cadres of the area on 13th April 1967. Clarifying the attitude towards middle and rich peasants, he said, “We shall always have to decide on whose side or against which side we are. We are always on the side of poor and landless peasants. If there is a conflict of interests between the middle peasant on the one hand and the landless peasant on the other, we will certainly be on the side of the landless peasant. If there is a conflict of interests between the middle peasant and the rich peasant, we will then be on the side of the middle peasant.”

He then added, “Our relations with the rich peasant will always be one of struggle. For, unless the rich peasant’s influence is weeded out from the village, the leadership of the poor and landless peasants cannot be established, and the middle peasant cannot be drawn over to us.”

By May that year, the rebels could claim as their strongholds Hatighisha under the Naxalbari police station, Buraganj under the Kharibari police station, and Chowpukhuria under the Phansidewa police station, where no outsider would enter without their permission.

They soon occupied land in the name of the peasants’ committees, burnt all land records which had been used to cheat them of their dues, cancelled all hypothecary debts, passed death sentences on oppressive landlords, formed armed bands by looting guns from the landlords, armed themselves with conventional weapons, like bows, arrows and spears, and set up a parallel administration to look after the villages.

Finding the situation going out of control, Harikrishna Konar came to Siliguri and met some of the dissident leaders. According to Konar, it was agreed that all “unlawful activities” would be suspended. The peasants would submit petitions for the land vested with the government, and land would be redistributed through official agencies in consultation with the local peasants’ organizations. It was also agreed that all the persons wanted by the police, including Kanu Sanyal and Jangal Santhal would surrender. The dissidents of North Bengal, however, denied that there was any such agreement. They complained that the CPI(M) ministers in the government were attempting redistribution of land through the same official agencies, which were in league with the local feudal interest, and were respecting the same old colonial laws, and describing any violation of such laws as ‘unlawful activities’. The CPI (M), in the face of the obduracy of the rebels, pleaded helplessness. It seemed to have lost control over the police also. In a statement released on 30th May 1967, by the West Bengal State Secretariat of the party, the latter expressed its inability to “understand why immediately after the return to Calcutta of Mr Hari Krishna Konar, a police camp was opened instead of pursuing the agreement arrived at.”

Charu Mazumdar at this stage felt it was necessary to warn his comrades of the impending attack by the state. In a letter to one of the comrades, he stressed the need for rousing hatred against the police. “The police obey orders; the moment the orders come they will launch the attack. They will get scared only when we attack them… explain this to the peasant masses.”

He reminded him, “The jotedars are still there in the villages; they will guide the police and take them into the villages and indiscriminately kill the peasants. So we must drive out these class enemies from the village; they are secretly maintaining contact with police thana; the police will launch attack with their help.”

He also urged his followers to make preparations to ambush police parties and snatch rifles from them.

The first serious clash between the peasants and the state machinery occurred on 23rd, May 1967, when a policeman named Sonam Wangdi was killed in an encounter with armed tribals, after a police party had gone to a village to arrest some wanted leaders. On 25th May the police retaliated by sending a force to Prasadjote in Naxalbari and fired upon a crowd of villagers killing nine including six women and two children. While the police version of the incident was that the rebels had attacked them from behind a wall of women and children, forcing the police to open fire, the dissident Marxist leaders alleged that the police deliberately killed the women and children. Later, several peasants were arrested. In the face of persistent police interrogation as to their leaders’ hideouts and the reasons for their confrontation with the police force, their stubborn and laconic reply was that they came out “for a breath of fresh air”.

Later, several peasants were arrested. In the face of persistent police interrogation as to their leaders’ hideouts and the reasons for their confrontation with the police force, their stubborn and laconic reply was that they came out “for a breath of fresh air”.

THE REPERCUSSIONS

The incident created tensions both within and outside the United Front. The West Bengal State Secretariat of the CPI (M) at a meeting on 29th May condemned the police firing and demanded a judicial inquiry into the incident. It added that “behind the peasant unrest in Naxalbari lies a deep social malady – malafide transfers, evictions and other anti-people activities of jotedars and tea gardeners.” It also accused the chief minister, Ajoy Mukherjee, an ex-Congressman, of laying one-sided stress on the police measures to maintain law and order. The next day, walls in the College Street area – the scene of the Presidency College agitation in the previous year – were littered with posters carrying the slogans “Murderer Ajoy Mukherjee Must Resign!” It was evident that these were the handiwork of the CPI (M) students, who were becoming disenchanted with their parliamentary leaders.

Meanwhile, reports of clashes between the rebel peasants and landlords kept pouring in from Naxalbari. According to official sources, only between 8th and 10th June, there were as many as 80 cases of lawlessness,13 dacoities, two murders and one abduction, and armed bands were reported to have been dispensing justice and collecting taxes. The West Bengal chief minister told newsmen on 12th June that ‘a reign of terror’ had been created in Darjeeling. The Centre immediately took up the cue, and the next day, the then Union Home Minister, Y. B. Chavan, told the Lok Sabha that a state of ‘serious lawlessness’ prevails in the area. He added that the government had reasons to suspect that extremists were playing a prominent role in it, thus dissociating them from the official CPI (M) leadership. It was evident that the entire establishment was ganging up. To them Naxalbari was the signal of popular retribution at last arriving. Finally, the United Front government sent a cabinet mission to Naxalbari, consisting among others of Harikrishna Konar and the CPI peasant front leader, Biswanath Mukherjee, who was then the Irrigation Minister but their appeal to the rebels to give up violence did not yield any result.

By the end of June while the CPI (M) leadership was openly coming out against the Naxalbari rebels, in Calcutta the various groups within and outside the CPI (M) who had been critical of the leadership, were coming together, thus gradually crystallizing the political differences. Mainly led by the Presidency College student leaders, the CPI (M) dissidents held a meeting in the Rammohan Library Hall of Calcutta, and formed the Naxalbari Peasants Struggle Aid Committee, which became a nucleus for a separate party of the future. They also staged a demonstration in front of the West Bengal Assembly on 27th June 1967. Meanwhile, The CPI (M) politburo in a resolution adopted on 20th June, on organization matters, referred to “the activities of certain individual party members, especially in West Bengal” and concluded that “they were no more a political trend in the party but have grouped themselves into an organized anti-party group advocating an adventuristic line and actions, challenging the party programme and resolution and directive, passed by the Central Committee”. The resolution further directed the “State Secretaries, specially of the West Bengal State Secretariat, to immediately expel them from party membership”. In pursuance of this decision 19 members were expelled from the CPI (M). Among them was Sushital Ray Chowdhury, a member of the party’s State Committee, who was to play a leading role in the CPI (M-L).

As the rebel activities continued in Darjeeling, a significant development took place. In a comment on 28th June 1967, Radio Peking described the Naxalbari incidents as “the front paw of the revolutionary armed struggle launched by the Indian people under the guidance of Mao Tse-Tung”. And dubbed the United Front government as a “tool of the Indian reactionaries to deceive the people”. This was the first evidence of Chinese support to the rebels and of Peking’s disenchantment with the CPI (M).

On 12 July 1967, a major police action was launched at Naxalbari, to round up the rebels and their leaders. Although Ajoy Mukherjee claimed that the CPI (M) was also a party to the cabinet decision to launch the action, the West Bengal State Secretariat of the CPI (M) in a statement issued in Calcutta on 19th July, sought to disassociate itself from the police action. It said, “The top police officials have thrown to the winds all the instructions given by the Cabinet and have launched a repressive drive against the peasantry.” The Chief Minister also came in for attack: “It seems that the Chief Minister of the United Front Ministry who is also in charge of the Home portfolio, has succumbed to the pressure of the Union Home Ministry and must be held responsible for the atrocious excesses in Naxalbari.”

In a comment on 28th June 1967, Radio Peking described the Naxalbari incidents as “the front paw of the revolutionary armed struggle launched by the Indian people under the guidance of Mao Tse-Tung”. And dubbed the United Front government as a “tool of the Indian reactionaries to deceive the people”.

By 20th July, Jangal Santhal and some other leaders of the Naxalbari peasants were arrested. Although Kanu Sanyal evaded arrest till October 1968, several followers also surrendered by the end of the month. With that, an apparent lull set in in Naxalbari.

‘In The Wake of Naxalbari’ by Sumanta Banerjee was originally published in 1980. It was republished in 1984 as ‘India’s Simmering Revolution: The Naxalite Uprising’. It is one of the most comprehensive studies of the Naxalite movement, unique for the reason of it being a study from within, a work of investigative journalism. Banerjee, a journalist at the time Naxalbari erupted, joined the movement and observed and learnt about it from among the company of its cadres. You can buy the book here.

Leave a Reply