(Quotes in this introduction, where not attributed, are from Monobina Gupta’s book Left Politics in Bengal: Time Travels Among Bhadralok Marxists.)

The Communist Party of India (Marxist) is a much depleted force in Indian politics. Looking at the party today, few would be able to imagine that it was at the head of the longest surviving elected state government: not only of this country, but perhaps of the world. The CPI-M led Left Front ruled over West Bengal for 34 long years and a record five terms.

It would perhaps have been equally impossible for people living in the 1980s or 1990s – maybe even the early 2000s – to imagine that the party would one day become a near-irrelevant actor in politics.

So what happened to the Left in Bengal?

It is precisely this question that Monobina Gupta, a veteran journalist, seeks to answer in this chapter from her book Left Politics in Bengal: Time Travels Among Bhadralok Marxists.

Gupta delves deep into various key aspects of the Left Front’s politics, ranging from the use of political violence and surveillance techniques to its alliance with cultural and intellectual stalwarts. She also simultaneously dissects important events in its history.

Along with drawing from multiple rich sources, she augments the narrative with notes of her own personal experience of growing up in Calcutta and as a young student activist. The book is interspersed with evocative descriptions of Calcutta in all its vibrancy and chaos. In the chapter below, for instance, she describes the social practices of the city’s babus: “The area around the secretariat has the lazy somnolence of a holiday. Stalls cluttering the footpath outside the building sell a variety of food, from toast to fish curry, rice, pakoras and phuluris.”

The chapter we share today, titled ‘The Romance of Power’, picks up after the Left Front’s surprising victory in 1977, which put a stop to the “the frenzy of political violence—the bloody clashes masterminded by the Siddhartha Shankar Ray government.” CPI-M cadres who had ‘gone underground’, resurfaced, and eagerly took on their new role in the state.

The early years would not be easy. As Monobina Gupta writes, “the first ten years felt like walking on a bed of hot coals, a legacy left by the Congress.” Nothing seemed to work properly – the education system had collapsed, the electricity department was struggling, and traffic jams had become endemic to Calcutta long before the country’s other big cities even knew what they were.

The Left Front was thus confronted with “a state in tatters,” which expected much from them after decades of Congress (mis)rule. Considered “clean and pro-poor,” the CPI-M turned into a corrupt and morally compromised institution much later. Back then, it represented a welcome change.

The weight of these expectations was compounded by the CPI-M’s uncertain future. Everyone assumed that all it would get would be “a short stint in power,” for a maximum of five years (or less, if the Centre felt vengeful). Despite their unfamiliarity with “the world of constitutionality and governance,” the leaders of the Left quickly got to work, aided by their committed and energetic cadre. Their goal was to deliver remarkable results in a short time, establishing support for future fights.

It started with Operation Barga, in 1978, and the introduction of the country’s “first three-tiered panchayat structure.” Under Operation Barga, approximately 1.3 million sharecroppers’ names were recorded (by the mid-1980s) and they were granted protection from eviction as well as an assurance of the due share of the crop through the Land Reform Act. This mammoth task was only possible because the government was able to mobilise the bureaucracy and party cadres “on a war footing.”

An “expansive, well-knit network” came into being hence. Initially, this machinery was used for working for the genuine benefit of the people, but soon its purpose became the service of the party instead. And the party committed itself to one goal above all others: to hold on to power at all costs.

This became easier from the 1980s onwards, since an opposition all but disappeared from the state. CPI-M could cruise through elections, winning two-thirds majority despite not having much to show for its rule. Numbers became more important than the people and the party changed from “a livewire, organic party to a vote-spinning machine.”

With longevity of power also came compromises, both ideological and organisational. An example of the former was the change in the Left Front’s relationship with workers, up till then an important bastion of support. The Left had always encouraged militant labour struggles in the past, in keeping with its ideological orientation. However, once in power it was felt that disruptions in industrial activity due to such upsurges caused more harm than good. Therefore, the Left “started distancing itself from the concerns of the working class.”

On an organisational level, after the CPI-M’s status as “a ‘feel-good’ party” was cemented, it lost the edge it had over other parties. Attracted by a near definite guarantee of power, “all shades of people” began flocking to the party. Once known for a dedicated and inspired cadre, filtered through an induction procedure that was the stuff of legend, the CPI-M now began to operate like a corporation – inducting all and sundry, without any need or demand for ideological commitment.

The destructive impact of these compromises was not apparent in the early years; the recognition of their harm was made doubly difficult since the culture within the CPI-M discouraged dissent. These authoritarian tendencies grew stronger and structured both the party and its presence on the ground. As Gupta describes it, “The CPI-M presides over a Kafkaesque world mapped by an `invisible third eye’—tracking, recording, filing.” The police force was turned into an extension of the party, which utilised it to eliminate alternative political forces before they could emerge.

It also kept a watchful eye on the people within the party, strictly monitoring the very strict line that separated “‘aamader lok’ (our people) and ‘aamader lok na’ (not our people).” As the chapter shows through the example of Badshah Alam, not following the ‘party line’ could prove expensive. The CPI-M protected those loyal to it just as fiercely as it punished the ‘traitors’.

While party cadre began to thrive, people suffered. Corruption and lawlessness became wide spread, while the party leadership tried to brush everything under the carpet. Then Chief Minister Jyoti Basu’s attitude sums up the ubiquity of violence perfectly: when he was made aware of the murder of a senior officer of the UNICEF on the outskirts of Calcutta, he remarked, “These things happen, don’t they?”

In short, too many contradictions had emerged in the Left Front’s rule. Some that had already existed became sharper as well. The CPI-M was never as progressive about gender as it claimed to be but coupled with a culture of violence and goondaism, its patriarchy became fatal. The starkest evidence of this can be found in the sexual violence carried out at Nandigram, which the party then tried to cover up (with the help of its women’s wing!).

In many other ways as well, Nandigram was the culmination of a decades long process: all the Left’s compromises for power finally caught up with them. It was the beginning of the end. The party realised this too, as they desperately scrambled for allies and tried returning to those it had once alienated, like Chandrayee Gupta, Badshah Alam’s wife.

And then in 2011 came the end. Not only did the Left Front fail to gain a majority, they lost dismally, scrambling together a total of 60 seats with the CPI-M winning just forty. It was too late, but perhaps they finally realised the ramifications of prioritising power over all else. As Monobina Gupta described it succinctly, “being in power became [for the Left Front] the means to endlessly reproduce itself.”

Only, nothing can be permanent in politics.

The city was still—the trams, the trees whose leaves were covered with a film of dust, the junctions, Lower Circular and Lansdowne road, the three-storeyed houses on Southern Avenue, the ten-storeyed buildings on Ballygunge Circular Road. Soon the machinery would start working again, not out of any sense of purpose, but like a watch that has been wound daily by someone’s hand. Almost without any choice in the matter, people would embark upon the minute frustrations and satisfactions of their lives. It was at this moment of postponement that the azaan was heard, neither announcing the day nor keeping it a secret.

Amit Chaudhuri, Freedom Song

1977 was an unusual year in Indian politics—not just for the country as a whole but also for West Bengal. The extraordinariness of that ‘magical year’ manifested itself in the ascendancy of a new set of rulers in Delhi and Calcutta, in the beginnings of a political culture that has lived ever since. The political convulsions hit India’s oldest party hard, and one of its most charismatic leader, Indira Gandhi, bit the dust. The Congress prime minister and architect of the infamous Emergency lost the general elections to a coalition of diverse political parties, ranging from Right to Left. The winners laid down a plinth, though somewhat fragile, for multi-party coalition rule, bringing the curtain down on three decades of Congress monopoly over governance at the Centre.

Within a span of three months, Indian political parties put together new power structures that resembled nothing we had seen in the past. In March that year a Janata government headed by Morarji Desai, supported by the CPI-M from outside, took charge of the Central government. Three months down the line the hammer-and-sickle-emblazoned flag of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) was flying high from the seat of power in West Bengal. Trouncing the Congress and its infamous Chief Minister Siddhartha Shankar Ray, a CPI-M-led Left Front government — the state’s new ruling ‘elite’ – embarked on an uninterrupted journey of thirty-three long years, a journey that still continues. The Left Front won 230 seats and a 54 per cent vote share in the 294-member Assembly. The CPI-M on its own ratcheted up a clear majority; what a fall it was for the high and mighty Congress, suddenly finding itself stripped down to 20 seats with a mere 23 per cent vote share.

Morarji Desai, who replaced Indira Gandhi as Prime Minister in 1977.

Who would have imagined such a stunning change of political equations? Who would have believed the ‘party of struggle’ would be in the seat of governance for the next three decades; that it would walk a tightrope, balancing contradictions arising out of its past history and present obligations? In the years and decades to come, compulsions of governance would increasingly collide with the politics of militant struggle, in the process making the ‘revolutionary’ party an expert at doublespeak. The compulsions of governance landed the CPI-M in a predicament it would hardly have anticipated. With each passing year in Writers’ Building, the CPI-M found it more and more complex to balance the obligations of governance with its core politics of struggle. The doublespeak became inevitable as the party grappled with contradictory pulls and tried to address the conflicting needs by adopting multi-layered strategies.

But that is a story that would unfold later.

Back in June 1977 it was a moment of relief and euphoria for the victorious Marxists. Not only were their days of being on the run over, it was an hour of ‘sweet revenge,’ when the party could call the shots from West Bengal’s citadel of power. In that moment of glorious victory the CPI-M spoke a language of assurance and promise that eventually disappeared. Chief Minister Jyoti Basu promised to run his government not from Writers’ Building, the imposing red brick building built by British designer Thomas Lyon in 1780, but from run-down villages and dusty small towns scattered through West Bengal.

Back in June 1977 it was a moment of relief and euphoria for the victorious Marxists. Not only were their days of being on the run over, it was an hour of ‘sweet revenge,’ when the party could call the shots from West Bengal’s citadel of power. In that moment of glorious victory the CPI-M spoke a language of assurance and promise that eventually disappeared.

In the flush of victory Jatin Chakraborty, the Left Front government’s public works minister, painted bright scarlet the dome of Calcutta’s iconic Shaheed Minar, rising regally from the grounds of the Maidan. To me and in the perception of the public, the sudden burst of aesthetic defiance was like swishing a red cloth in front of the Congress! The sight of the red dome glinting in Calcutta’s scorching sun did not go down well with the Bengalis. Hissing under their breath each time the gleaming red turret came into their line of vision, they cursed Chakraborty, responsible for sullying one of Calcutta’s prized monuments and creating an eyesore. An incessant lament over the disfigurement and the ‘unaesthetic, propagandist’ souls of the ruling communists!

As the fresh coat of paint began to dry under a merciless Calcutta sun, the Left Front got down to its mammoth and daunting job of governance. The first ten years felt like walking on a bed of hot coals, a legacy left by the Congress.

Writers’ Building, Kolkata. Photo Credit: Matt Stabile, Flickr.

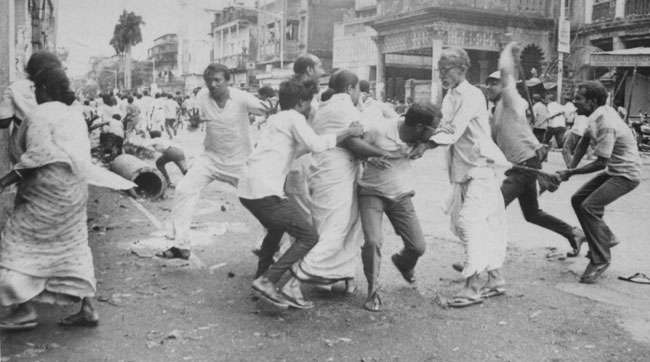

In the collective memory of West Bengal, 1977 was a special year. During the previous five years people had watched in disbelief the frenzy of political violence—the bloody clashes masterminded by the Siddhartha Shankar Ray government. Tens of thousands of CPI-M cadres had lived in the depths of shadows, chased and hounded by the ruling Congress. The relentless terror had groomed the CPI-M well to withstand the assault of the Emergency. When Indira Gandhi trained her guns on her opponents, the Marxists tested by fire, trained in the teeth of violence, were more than equipped to counter the excesses of the Emergency. ‘The intensity of state repression unleashed in the city [Calcutta] between 1970 and 1973 was of such magnitude that, unlike many other parts of India, Calcutta saw little in the year and a half of the Emergency to add to what it already knew about the ways of an authoritarian regime,’ writes political scientist Partha Chatterjee. In West Bengal more than 18,000 people had been rounded up under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA). Perhaps few other Indian states were then so torn by political violence. When the Left Front won the people’s mandate it inherited a state in tatters, where everything apart from violence seemed to have come to a standstill. Once considered among the best educational institutions in the country, Calcutta University was haemorrhaging. Examination schedules were running late by more than a couple of years. Results were delayed long enough to prevent students from applying to universities outside West Bengal. At Calcutta University’s Department of Ancient History and Archaeology, where I did my post-graduation between 1978 and 1979, students of Law College, next to our department, often spoke of the rough times. ‘This was where a bomb exploded that morning. I had just come in. Chhatra Parishad (Congress’s student wing) activists were on the other side. They hurled a bomb. It was all smoke. Students ran for cover,’ said Parthada, a student of Law College. (Since he was a couple of years older than me I had succumbed to the Bengali tradition of adding a ‘da’ after his name)

Parthada spoke of many similar mornings when lecturers and students fled classes as activists of the Chhatra Parishad and SFI hurled bombs at each other, across the street. In 1978 I found it difficult to imagine the delirium of violence described by him. The street outside my department hummed with normalcy – with its steady stream of traffic, buses and cars honking madly, the rush of chattering students. I often thought Parthada, despite his cut-and-dried, pragmatic Marxism, secretly nurtured the imagination of a storyteller.

In West Bengal more than 18,000 people had been rounded up under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA). Perhaps few other Indian states were then so torn by political violence. When the Left Front won the people’s mandate it inherited a state in tatters, where everything apart from violence seemed to have come to a standstill.

But repairing the badly damaged system took time. My MA examination in archaeology, scheduled in 1980, was held two years later. The chief minister said the government was doing its best to bring the examination schedule back on track. The backlog was stunningly high. The results almost never came on time. It was not just the education system that was mangled—essential services like electricity supply were in a complete mess. I remember studying by the light of lanterns through much of my school and college days. The Calcutta State Electricity Board, crippled by a chronic shortage of power supply, plunged the city into darkness after the sun went down. Through the day you sweated and grumbled. Generators were yet to become part of household furniture. Summers, always agonising in Calcutta with its heat and humidity, became excruciating with long stretches of power cuts. Fans would suddenly taper off to a halt as we wrestled with Brahmi and Kharoshthi scripts in epigraphy and inscription classes. Calcuttans had to submit themselves to a gruelling regime of rationed power. Each area had its daily chart of power cuts, which turned your fans and lights off at least twice, for a minimum of a couple of hours. Often unscheduled power cuts would drag on for five to six hours, if supply from the Damodar Valley Corporation’s mega thermal power plant dried up. Sometimes for half the night you would battle droning mosquitoes, fanning yourself with newspapers. The sale of hathpakhas (hand fans) made of bamboo prospered. I remember days when I would leave home hot and sticky, have a few hours respite at the department till load-shedding struck and then return home to darkness. It seemed Calcuttans were mandated to spend their evenings in the flickering shadow of candlelight. In buses and local trains people cursed the government and the power supply, spinning yarns and jokes around the ubiquitous phenomenon of load-shedding which dictated their lives.

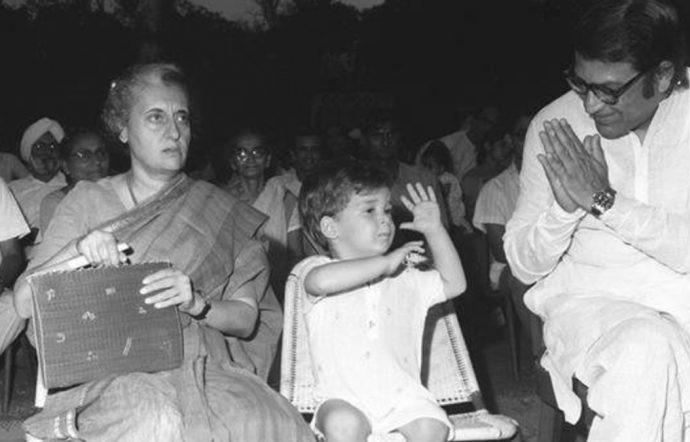

Siddhartha Shankar Ray (Right), CM of West Bengal from 1972 – 1977, pictured with Indira Gandhi. Photo Credit: Twitter.

Calcuttans did not just have to plough through the darkness; the mayhem on the city’s roads made travel an agonising ordeal. The city was being turned upside down to build India’s first and Asia’s fifth underground metro railway; its faltering, chaotic construction went on for years. People dreaded hitting the roads, which looked like they had been bombed. Traffic was a crazy maze in which buses and cars would stay knotted for hours on end, without moving an inch. Work went on endlessly inside trenches dug at crucial traffic junctures, where the tangle of vehicles was especially thick. Through the pile of mud and rubble people would make their way. Suddenly the rains would come, flooding the trenches, leaving the ground slushy. Metro traffic cops, the kind we see around Delhi’s Metro construction sites, standing to attention and waving road diversion signs, did not exist. There were no signboards indicating what lay ahead on the jagged stretch of road. Anyway Calcutta never had the luxury of road space like Delhi to flag off endless diversionary routes. So traffic mayhem raged unchecked.

In Freedom Song author Amit Chaudhuri describes a deadly traffic jam, which was fast becoming to Calcutta what local trains were to Mumbai and DTC (Delhi Transport Corporation) buses to Delhi.

But repairing the badly damaged system took time… The backlog was stunningly high. The results almost never came on time. It was not just the education system that was mangled—essential services like electricity supply were in a complete mess.

`It took them forty-five minutes to negotiate Circular Road, Chowringhee, the junction before Bentinck Street and finally to pass Mahajati Sadan and to arrive at the small lane on the left. By then, they felt they’d come to what was probably another city. Just on the right what looked like a deep ditch had been dug in Central Avenue, where actually unfinished work for the underground had been begun and then interrupted. Although the ditch almost looked fearful, there were in fact two children playing and rushing upon it, climbing from one side to the other and then disappearing again’. This ‘jam’ as it was called in popular parlance, became the emblem of Calcutta long before any of the other metropolises had even heard of it.

The genesis of Calcutta Metro went back to 1949 when West Bengal’s first Chief Minister Bidhan Chandra Ray planned it. Two decades later in 1972, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi laid the foundation stone. It took almost another two years for the work to start. Dogged by lack of funds, court injunctions, shifting of underground facilities, the work continued with long pauses in between. After the Left Front government came to power the people waited another seven years for the Metro to start even a partial service. And meanwhile the Calcutta Metropolitan Development Authority, which really had nothing to do with the digging, became in popular rendering khurchhi maati dekhbi aaye (come, watch us digging earth).

*

Jyoti Basu had inherited a badly messed up state from his Congress predecessor, which had to be cleaned up fast. Expectations were running high. Communists, yet to metamorphose into ‘power junkies’, had a clean and pro-poor image, unlike their predecessors, known to be a refuge for the rich and influential.

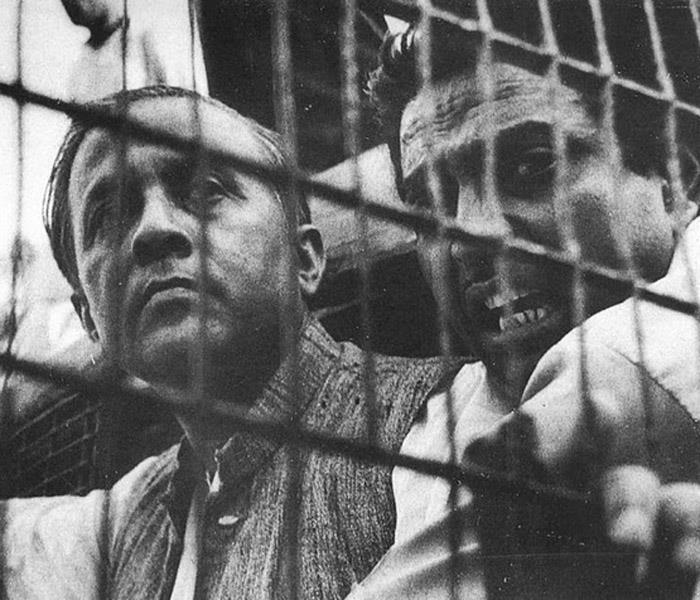

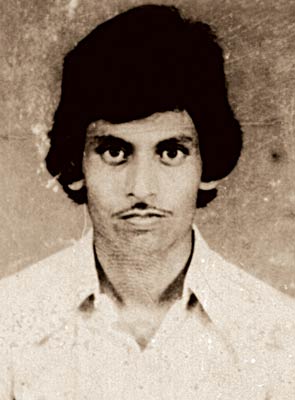

Jyoti Basu (Left) during his days of activism. Photo Credit: Communist Party of India (Marxist), Facebook.

The educational system had to be overhauled on a priority basis. Bit by bit university examinations reclaimed their schedules on the academic calendar. Students received degrees in time for them to appear in competitive examinations outside the state. The power situation started improving. Summers became bearable as fans and lights stopped playing whimsical pranks. Street lights came on and stayed that way. Lanterns were tucked away; candles were brought out only on special occasions. Calcutta moved from ‘darkness to light’ and the term ‘load shedding’ gradually lost its currency in conversations. It took the Left Front government time but it finally managed to retrieve the power sector from the depths of darkness; effectively enough to provide West Bengal with a surfeit of electricity. However, an apprehension that load shedding could return with a vengeance once factories started functioning, lurked somewhere at the back of the mind.

The raw political violence that lashed Calcutta for more than a decade ebbed. The macho aggression displayed by the Congress in the early 70s disappeared with the Assembly election results. Parts of Calcutta that had been swathed in smoke from explosions of crude bombs, ‘off-limits’ for youngsters, reclaimed their normal rhythm. But the spirit of violence, like the spirit of resilience, has a way of surviving. The oxygen of violence on which the politics of that decade survived and flourished never ran out of reserves; not even after the Left Front government brought enduring stability to the state. Violence was merely tamed and brought under control. West Bengal till today has the highest incidence of political violence.

But the spirit of violence, like the spirit of resilience, has a way of surviving. The oxygen of violence on which the politics of that decade survived and flourished never ran out of reserves; not even after the Left Front government brought enduring stability to the state. Violence was merely tamed and brought under control.

How do I describe this city of dreams, madness and desire?

On the body of each city are etched the marks of identification by which it wants to be recognised and known. Suketu Mehta writes in his book Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found, ‘The history of each city is marked by a catalytic event just like each life has a central event around which it is organised. For New York it is now September 11, 2001, attacks on the World Trade Center. For the Bombay of my time it is the riots and the blasts of 1993. Bombay was spared the horrors of Partition in 1947’. He then adds, ‘But there was an earlier trauma in the psychic life of the city, which marked the before and after for old-timers: the explosion of the Fort Stikine on 14 April 1944…. Fort Stikine, a ship carrying bales of cotton, a secret cargo of gold and silver and wartime explosives caught fire and went up in smoke as it stood in the harbour waiting to be docked. The sky over Bombay was filled with gold and silver, masonry, bricks, steel girders and human limbs and torsos flying through the air as far as Crawford Market,’ writes Mehta.

When I try to think of the catalytic events that made Calcutta what it is today, simply too many of them jostle for attention: the stormy agitation against the one paise hike in tram fare in the heart of Calcutta, killings of CPI-M activists by the Siddhartha Shankar Ray government, the slaughter of Marxist-Leninist cadres by the men of the CPI-M and the Congress, the birth of the Left Front government, the announcement of Operation Barga and then the hail of bullets putting to death resisting peasants at Nandigram…

Jyoti Basu at the head of a march along with other leaders of the Left Front government. Photo Credit: Surjya Kanta Mishra, Twitter.

The Left Front’s raison d’etre, which actualised itself with Operation Barga, was lost forever at the barricades of Nandigram. The two developments were woven by a special bond – a history of land reforms, initiated in 1977. Later in the book, I will talk about how the reforms were derailed a decade later, how the ruling CPI-M lost the will to carry them to their logical conclusion. For the moment let me return to 1977 and the landmark Operation Barga. Few people, even dyed-in-the-wool supporters of the Left, would have believed the Marxists would preside over the state for more than three decades. Given its past experience of President’s Rule and sudden dismissals of state governments by the Congress at the Centre, the Left Front was looking at a short run on the pitch. Its aim was simple: initiate landmark policies carving out a political and electoral niche as a buffer against storms in the future; an investment necessary to reap dividends later.

Not the first instance of land reforms in the state, the Left’s ascendancy definitely unleashed for the first time a sincere effort to implement them.

The Left Front’s raison d’etre, which actualised itself with Operation Barga, was lost forever at the barricades of Nandigram. The two developments were woven by a special bond – a history of land reforms, initiated in 1977.

Between 1972 and 1977 the Congress regime of Siddhartha Shankar Ray had listlessly dabbled in land reforms without any serious inclination to implement them. The Land Reform Act was amended as far back as 1955. The Congress government had even passed legislation to introduce a three-tier panchayat system. The decisions, which would have significantly changed the power structure in rural Bengal, remained on paper till the Left Front government won the elections. The Front had gone to the Assembly polls with a 36-point programme which included promises of land reforms, reorganisation of Panchayati Raj, improvement in agriculture, new roads, better irrigation system, safer drinking water, improvement in health and education systems. When the CPI-M came to power in 1977, it did not anticipate the destiny that would unfold over the next three decades; never did it perceive itself as running a State government year after year. The leadership readied itself for a short stint in power—at best a five-year term, at worst a sudden guillotine by the Centre. Undoubtedly the party was under pressure to bring about, in what it perceived as borrowed time, a qualitative change in the balance of power, fulfil its ideological commitment as well as build a solid reservoir of political and electoral support. The CPI-M gave land reforms top priority, combining its ideological belief with the need for a mass social base. It must be remembered that even during the earlier United Front governments in the late 1960s, the CPI-M had made agrarian reforms its main plank. The food movement, the engine of change, created a groundswell of support for the party, enhancing its credibility and image as an ally of the poor. Under the leadership of Land Reform Minister Harekrishna Konar, the party had seized large tracts of benami land, tilting the power balance in favour of the poor in the countryside. But once the United Front governments collapsed, retaining these gains became difficult. After coming to power this time round, the Left Front wanted to ensure that the changes would endure: Operation Barga was a milestone in this direction, a wise strategic political investment, which, as time passed, became the fulcrum of the Left Front’s continued existence at the helm of power.

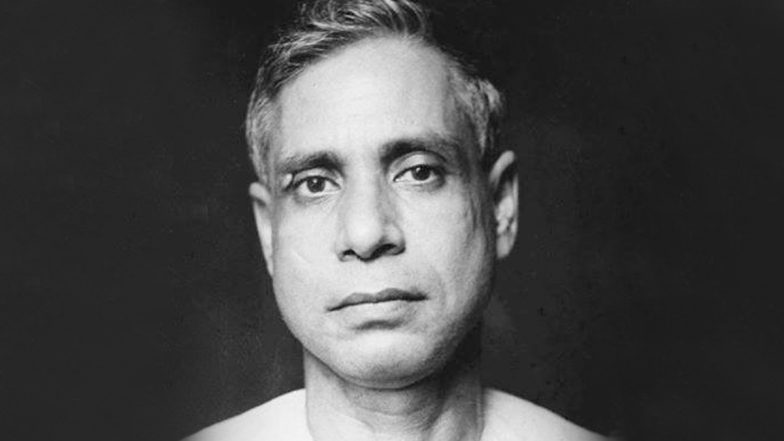

Ajoy Mukherjee, leader of the Bangla Congress and Chief Minister of Bengal in the United Front government.

Operation Barga set in motion this process of building the indispensable political tools the party used to electorally preserve itself so well. An expansive, well-knit network, politicised to the hilt stood at the beck and call of Alimuddin Street, ready to execute every command. The sharecroppers registered under the programme were provided with protection from eviction and given their due share of crop under the Land Reform Act. The Left Front government mobilised the bureaucracy and the party cadres on a war footing to put the programme in place. Side by side the CPI-M organised elections to the country’s first three-tier panchayat structure. ‘Prior to 1977, only some 275,000 sharecroppers had bucked the rural power structure and registered. By December 1985 as many as 1.3 million of the estimated 2 million West Bengal sharecroppers-96 per cent of all `tenants’—were recorded,’ writes T J. Nossiter of Operation Barga. Later I will talk at length about the CPI-M’s manipulation of the institution of panchayati raj and its subsequent abandonment of land reforms.

The leadership readied itself for a short stint in power—at best a five-year term, at worst a sudden guillotine by the Centre. Undoubtedly the party was under pressure to bring about, in what it perceived as borrowed time, a qualitative change in the balance of power, fulfil its ideological commitment as well as build a solid reservoir of political and electoral support. The CPI-M gave land reforms top priority, combining its ideological belief with the need for a mass social base.

Before June 1977 the world of constitutionality and governance was far removed from the CPI-M’s concerns. If anything, the party was engaged in direct conflict with that world. Inside the secretariat it was time to shift to Plan B. Disengaging itself bit by bit from the path of struggles the new ruling elite, in the beginning, leveraged the state machinery to provide relief to the people but gradually that gave way to something else: being in power became the means to endlessly reproduce itself. Cynical manipulation of power saw an end to the romantic age of innocence as the CPI-M lost that distinctive edge which had once set it apart from the rest of the political class. Plan B was not something that the CPI-M had in mind when it came to power. It was crafted bit by bit over the years as the CPI-M struggled with its internal contradictions—moving away from its ideological axis. Once it became clear that the party would have to rule and produce results and not just for a brief period, the strategies diversified, some conflicting with the CPI-M’s essential political philosophy. Matters started becoming complicated. In fact in 1984-85 after the party suffered serious electoral losses, following the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, there seemed to have been some sort of disquiet within the party. Paragraph 112 of the party constitution allowed the CPI-M to run state governments, but with the rider that in this process, it should impact and change the state machinery, as well as mobilise the people. The paragraph was added to the new constitution of the CPI-M in 1964 when, in the light of the 1957 experience of the Namboodiripad government, the party debated whether it should form a government in case the possibility arose. In a sense, it was the CPI-M’s Plan B.

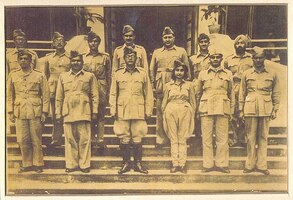

Kerala’s Council of Ministers, 1957, led by EMS Namboodiripad. One of the first democratically elected state governments of the world, it was dismissed in 1959 by the Central Government.

In the 1980s M. Basavapunnaiah, in an article in Desh Hitaishi raised certain questions about the spirit of Para 112 and whether the ruling CPI-M in West Bengal was being true to it. The questions he posed were: How much has the CPI-M been able to do in West Bengal? Has the party been able to provide relief, rally the people and scale up their political consciousness? Without being overly critical, the tone of the article suggested that all was not well. A discussion followed in the party but it was muted. The fall of the socialist bloc subsequently lent weight to the debate on whether socialism can flourish in a multi-party democracy, a debate that found a lively platform in the 1992 party congress in Chennai.

As Operation Barga got off the ground, its impact could be seen in the outcome of the 1978 panchayat elections. The Left Front won 69 per cent of seats and polled 54 per cent of votes. The dominance of landlords, rich peasants and moneylenders, which had been the bedrock of Congress support, broke. ‘For the first time in West Bengal, democratic devolution of powers took place. The new leaders of the panchayats were not moneylenders or rich peasants. They were marginal farmers, primary or secondary teachers, unemployed young men, or landless agricultural labourers’, writes Sudhir Ray. ‘During the panchayat elections of 1993 and 1998, it was found that Marxist parties could retain their support base in the rural areas. The reason for these successive victories is to be found in the changed co-relation of classes. The landlords, rich peasants and moneylenders no longer dominate in the rural areas,’ he continues. The panchayats included a large number of the rural poor, marginal peasants, teachers, women and Dalits.

Disengaging itself bit by bit from the path of struggles the new ruling elite, in the beginning, leveraged the state machinery to provide relief to the people but gradually that gave way to something else: being in power became the means to endlessly reproduce itself.

Even as rural Bengal was coming to life, West Bengal’s straggling, moribund industries were still gasping for breath, Outlining the historic backdrop stunting the state’s industrial growth T J. Nossiter writes, ‘At partition in 1947 West Bengal was deprived of its hinterland; its key industries, in key instances have been overtaken by technological innovation; communications are poor, and from the point of view of available investors, private, public, international, other areas of India have seemed more attractive, in some measure because of the uncertainty of the political situation at least prior to 1977 and because of industrial agitation.’

Political unrest and violence that crippled the state in the 60s and 70s deepened the severity of industrial depression. Small scale industries located on Calcutta’s outskirts, the hotbed of clashes between Naxals and men of the CPI-M and the Congress, disappeared one after another. Militant trade union activities led by the CPI-M’s trade union wing, Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU), which continued even after 1977, did not help matters. Employers retaliated with lockouts. Shutters were downed, gates padlocked. Lockouts happened in the blink of an eye. The industrial belt along the Hoogly river became a haunted expanse of dilapidated buildings, their padlocked gates corroded by rust and moss. The responsibility for the corrosive decay lay in multiple quarters: at the door of the party and the government—for pretending to look the other way even as industries were vanishing overnight; with managements for their flightiness and financial corruption; with the CITU — for sticking to old strategies. Ostrich-like, the trade union had a habit of walling itself in, every time workplaces reinvented themselves, keeping pace with technological changes, launching modernisation drives. Failing to anticipate the rush of technological innovations, CITU in the 1980s slammed the door on computers and modernisation of factories, chanting instead the tired old slogans.

Workers protesting outside Kanoria Jute Mills in 2020. Photo Credit: Workers’ Unity Bengali, Facebook.

There was no single cause behind the stagnation. Post 1977 the workers were virtually left to fend for themselves as the CPI-M and the CITU tried to fulfil the economic mandate thrust on them by liberalisation. But the working class in Bengal, with its tradition of militant activism in the late 60s and 70s, had come to regard the notion of work not simply as a source of income and material incentive, but also of rights and entitlements. ‘It was a potent political construct for all workers,’ writes Nandini Gooptu. The Left Front could not turn its back on the electoral support of workers but the transformation of the CPI-M from a party of struggles to the ruling elite hit them hard as the CITU, cutting corners, tried moulding itself to suit the government’s new economic plans. Labour militancy had to be contained and eventually snuffed out. Functioning within the neo-liberal system the Left Front government started distancing itself from the concerns of the working class, thrown into a state of anxiety, as liberalisation sounded the death knell for traditional industries like textile and jute. Unwilling to support labour agitations, the government and the CITU hastened to clinch deals with employers. Pushed to the wayside by the party and the trade union, workers struck out on their own. Through the 1990s, labour unrest assumed different forms. Violence broke out at Victoria Jute Mills in 1992 as workers turned on trade union leaders, attacking the union office and policemen. One person lost his life. In Howrah’s Kanoria Jute Mills the workers adopted a different path, declaring autonomy from the party and the trade union. They instituted the Sangrami Shramik Union, an independent non-party trade union in February 1993, sending a clear message of their loss of trust in the CPI-M and the CITU. Rather than in vain for a successful negotiation with the management, the union occupied the closed mill and resumed production. The unusual and spontaneous workers’ movement taking off without trade union banners created a ripple, even though the experiment did not translate into enduring results. Many middle-class members, including artistes, allied with Kanoria workers who hoped to turn the mill into a workers’ cooperative. Despite public support to the notion of workers’ participation in the management, the CPI-M-led government offered the union no help, sealing the fate of a Kanoria workers’ cooperative. The mill was turned over to the management. Though short-lived and unsuccessful, the Kanoria Jute Mills experiment pointed to a new direction in the labour movement, not adopting the most practiced form of resistance like striking work.

The Left Front could not turn its back on the electoral support of workers but the transformation of the CPI-M from a party of struggles to the ruling elite hit them hard as the CITU, cutting corners, tried moulding itself to suit the government’s new economic plans. Labour militancy had to be contained and eventually snuffed out.

The transformation of the CPI-M from a livewire, organic party to a vote-spinning machine became more and more evident from the 1980s, when the party and the government became virtually one. Without a demanding opposition breathing down its neck, it was easy to get away with poor governance; easy to win a two-thirds mandate in election after election. The democratic cycle of elections, the principle of rewards and punishments came to a halt.

Writers’ Building on Kolkata’s bustling B. B. D. Bagh stood as indelible proof to the sloth that had crept in and settled on the government. Nothing in the secretariat—the Left Front’s nerve centre—seemed to have changed in the last three decades. As if the grand old building had settled into an inexorable time warp. In thirty-three years of Left Front rule, Jyoti Basu alone ruled for 23 years (1977-2000). The babus of Writers’ Building have been taking orders from the same cabinet and implementing them desultorily, unlike their predecessors during colonial rule who worked long and hard. The first inhabitants of Writers’ Building, which started functioning as early as 1690, worked under tough conditions. Employed by the East India Company, the clerks lived in mud hovels at the present site of the brick-red structure. In 1965 a storm destroyed the huts. A second Writers’ Building was built followed by a new structure—from where the state secretariat now functions.

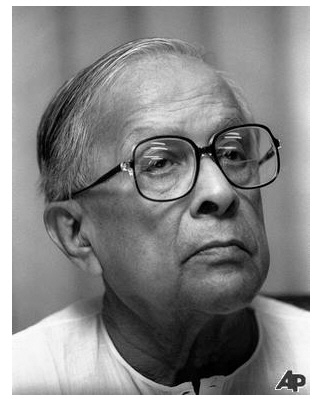

Jyoti Basu was West Bengal’s CM for 23 years (1977 – 2000).

The ‘modern’ Writers’ Building inhabitant is the quintessential babu, who rarely keeps office hours but seldom forgets to take his chhata (umbrella) and jhola (cotton bag) to work. He goes through the motions of a daily routine: gets off a jam-packed local train at Howrah station, boards an equally packed, rickety state bus, steps down at Dalhousie Square, ambles into the secretariat after the clock has ticked well past the hour of reporting for work.

The area around the secretariat has the lazy somnolence of a holiday. Stalls cluttering the footpath outside the building sell a variety of food, from toast to fish curry, rice, pakoras and phuluris. Famous for its street food, Calcutta is a hedonist’s paradise and a nutritionist’s nightmare. For the babus the food mart outside the secretariat is a place to ‘pass time’ when the files get too boring. Every once in a while they stroll out for a bite. Rows of honey jars stand at one corner and the air hangs heavy with the aroma of frying and cooking. Not surprisingly Jyoti Basu found the ‘eating disorder’ annoying and detrimental to the efficiency of his government. Hemming and hawing for a long time, the exasperated chief minister finally slapped a curfew on food vendors, restraining them from camping out on the footpath and tempting the Writers’ Building staff through the day. You can find them engaged in brisk business only between one and two-thirty now.

The transformation of the CPI-M from a livewire, organic party to a vote-spinning machine became more and more evident from the 1980s, when the party and the government became virtually one. Without a demanding opposition breathing down its neck, it was easy to get away with poor governance; easy to win a two-thirds mandate in election after election.

Like he would pull up the CITU, Basu, from time to time lectured Writers’ Building employees—also unwavering supporters of his party—on reporting to work on time, resisting the temptation of leaving the building before the sun went down. But counsel and caution came late when the employee was secure in the CITU’s protection. As liberalisation settled in and the economic environment became competitive, the Marxists felt the nudge to shed sloth and instil an efficient work culture. They had been ‘efficient’ in capturing political, educational and cultural institutions; taking them over systematically, appointing in key positions persons loyal to them, regardless of qualification or merit. From the very beginning, people inhabiting the world of the CPI-M were split into two categories: ‘aamader lok’ (our people) and ‘amader lok na’ (not our people). True, the Left Front government had ended the anarchy of the past that was destroying educational institutions. But in that process it also appropriated them, striking at the autonomy of academia. The universities and institutions had already begun to lose their shine and intellectual vibrancy in the early 1970s, the years of anarchy, and the decline continued after the takeover by the Left. Presidency College, a centre of excellence, caught in the throes of violence between the CPI-M and the Congress, later by the Naxal upsurge, deteriorated further during the Left Front government. Law College, a site of political violence in the 1970s, never regained its academic eminence. In place of intellectual autonomy reigned a dull culture of patronage, a relentless search for amenable, loyal appointees who would intone the party’s position on every issue of consequence. The challenge of a lively intellectual debate of contesting beliefs, in which the proponents heard each other out, was strictly absent. Those who played the game of passive compliance were rewarded; the ‘deviants’ who refused to extend intellectual endorsement were subtly and often not so subtly punished.

Moving from one election to the other, emerging a clear victor each time, the CPI-M over the decades came-to acquire the status of a ‘feel-good’ party. In the past the Congress had exuded a similar aura, before people started delivering fractured mandates, stripping the party of its monopolistic rule over India. We had journalistic slang for those drawn like a magnet to a party in power, regardless of its creed and politics. We called it the Opportunistic Party of India (OPI)! Its members were forever ready to do a 180-degree turn and switch loyalties to the party at the steering wheel at any given time!

Jyoti Basu with Nelson Mandela. Photo Credit: Communist Party of India (Marxist), Facebook.

West Bengal had more than its share of OPI members. In the political context of the state it ensured loyalty to only one party—the CPI-M. No other political party in India, or for that matter in the rest of the world, has held on to ‘absolute’ power electorally, without a break for so long. The people of West Bengal, some who would never have ordinarily crossed the path of communists, suddenly found in them a safe and lucrative refuge. The CPI-M appeared to offer the incentives of an attractive investment policy. The ‘jholawala shabby Marxist’ suddenly became the cynosure of all eyes. Joining the party was like signing up with a football club that unfailingly kicked the winning goal in the goalpost. The party’s membership in West Bengal galloped even as it floundered and lost whatever faltering base it had in the Hindi heartland to the Mandal parties. The irresistible pull of power worked wonders for the CPI-M when it came to a headcount of its members.

They had been ‘efficient’ in capturing political, educational and cultural institutions; taking them over systematically, appointing in key positions persons loyal to them, regardless of qualification or merit. From the very beginning, people inhabiting the world of the CPI-M were split into two categories: ‘aamader lok’ (our people) and ‘amader lok na’ (not our people).

Hunter Thompson in Kingdom of Fear said: ‘Res ipsa loquitur’ (Let the good times roll). Good times indeed were rolling for the CPI-M. In that heady process however, the inherent democratic principle propelling change ended up as the casualty. The withering of a credible opposition perpetuated the stagnation of the political status quo. For a while Trinamool Congress leader Mamata Banerjee seemed to rattle the Left Front’s composure, especially around 1999, when she called for a mahajot or a Grand Alliance with the Congress against the Left Front and did draw significant popular response. However, she lost that moment, oscillating between opposing and supporting the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government and quitting her cabinet post as Railway Minister. It took the Nandigram-Singur developments for the Trinamool Congress leader to return to West Bengal’s political centre stage.

How does the CPI-M’s balance sheet look at the end of thirty-three years?

A graph of losses and gains would show the party neck-deep in bankruptcy following the drain of ‘ideological wealth’. A comfortable existence of political dominance without resistance worth its name broke the party’s ideological spine. Driven by prospects of easy opportunity, all shades of people invaded the CPI-M. Once discerning, exacting in its choice of members, the party’s gruelling `rite of passage’, mandatory and inflexible in the past, became loose and flexible. The party loomed like a powerful corporation beckoning one and all, political and social climbers, ideological ignoramuses, rank opportunists, tantalising them all with possibilities that had nothing to do with the ideology of politics.

Before the ‘feel good times’ set in, becoming a card-holding member of the CPI-M wasn’t easy. It was like sitting for a test, one that went on for years. Only after passing through that critical wringer could you be certified as a card holding member – the term itself not part of the CPI-M language, but a quaint leftover from the days of the united CPI. There were no shortcuts and few lateral entries from the top. It was a little like the way journalists functioned before the onset of the internet and easy news gathering through wires. Editors then were tough, ensuring by the time the afternoon sun rose high, that reporters would be out of their air-conditioned offices; no short cuts. Bracing the heat and the cold was clubbed under `leg work.’ In the CPI-M’s terminology ‘leg work’ meant organising, mobilising students, youths, workers, peasants, women, teachers. You had to prove your skills as a ‘mass worker’ in any one of the party’s mass organisations and get at least a minimal idea of Marxist-Leninist philosophy. In fact it was considered infra dig to graduate to membership within a short time. Since I joined the party in West Bengal in the early 1980s – when the Left Front had its feet firmly planted in Writers’ Building – I knew myself to be part of that ‘non rigorous,’ maybe a trifle ‘looked-down upon’ membership, with an easy entry.

But even in those days of laxity you could not barge in like you could in the 1990s, the period of confusion and disenchantment when members started dropping out, disillusioned with the emerging face of socialism. These were also the times when the CPI-M further lowered its ideological guard and drafted new members without making too much of a fuss. The ‘nouveau’ communist—the ‘Marxist come lately’—strutted about, brandishing the ‘party card,’ using ‘brand CPI-M’ to further his/her interests. Gone was the Spartan communist epitomised by Harekrishna Konar or Promode Dasgupta—almost Gandhian in frugality, honed razor sharp in political battles, far removed from the labyrinthine power games of the establishment. The new lot went about ‘doing’ their politics like unscrupulous businessmen; bullying, extorting, terrorising became part of the ‘ideology.’ The West Bengal party leadership regularly carried out ‘cleansing’ operations to weed out the rot. But it ran too deep, too thick.

A graph of losses and gains would show the party neck-deep in bankruptcy following the drain of ‘ideological wealth’. A comfortable existence of political dominance without resistance worth its name broke the party’s ideological spine. Driven by prospects of easy opportunity, all shades of people invaded the CPI-M.

The CPI-M’s organisational documents circulated at its congress every three years routinely regretted the ideological downturn, but the slide, too rapid by then, could not be halted. Here lies one of the keys to the transformation of the CPI-M machine. For it was the machine that was supposed to cleanse, that itself got mired in a whole range of corrupt nexuses – with builders, contractors, police and local anti-socials. Try as they might, the state leaders never managed to control these new nexuses. Media and human rights groups regularly revealed the involvement of CPI-M members – often district level leaders – in incidents of rape and murder. Alimuddin Street almost unfailingly responded by scoffing at the allegations as part of a political conspiracy, or promising an inquiry, which invariably made its way into the files of unresolved crimes. This expressed more than anything else, Alimuddin Street’s helplessness rather than its complicity. Eventually, one can say, it was the leadership that was dependent on the monster it had created.

Anatonia was living in a communal apartment where the house elder was an ardent Stalinist, widely suspected as an informer, who made her suspicions of Anatonia clear. On one occasion, when a neighbour showed off her new pair of shoes, Anatonia had let her guard down by saying that her father would have made them better because he had been a shoemaker (a trade associated with the `kulaks’ in the countryside). Frightened that she would be exposed, it was a huge relief for Anatonia when Georgii Znamensky asked her to marry him. Marriage to Znamensky, an engineer and a citizen of Leningrad, would give her a new name and a new set of documents to let her stay in Leningrad.

Orlando Figes, The Whisperers

The CPI-M presides over a Kafkaesque world mapped by an `invisible third eye’—tracking, recording, filing. Communists have been known to make good, though not artful snoops. In West Bengal, under their thumb for more than thirty-odd years, comrades keep an eagle eye not just on each other, but on each other’s families and friends. ‘Guilty by association’, a dictum practiced by and consummated in communist regimes across the world, still carries with it a frightening respectability.

Chandrayee Gupta, daughter of Sadhan Gupta, among the six Lok Sabha MPs fielded by the undivided Communist Party in the first general elections of independent India in 1953, found herself condemned under the CPI-M’s ‘guilty by association’ fiat. Chandrayee’s was a classic ‘communist family’, bound intrinsically to the communist movement for at least two decades before its romance with Writers’ Building had bloomed. Her mother Manjari Gupta was the first president of the CPI-M backed All India Democratic Women’s Association. ‘I grew up in the party. I remember participating in the 1965 khadya andolan (food movement), civil liberties movement, in every election from 1967 to 1991,’ said Chandrayee. A member of Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) since 1971, Chandrayee became active in the SFI from 1974. She joined the party in 1977.

The CPI-M presides over a Kafkaesque world mapped by an `invisible third eye’—tracking, recording, filing. Communists have been known to make good, though not artful snoops. In West Bengal, under their thumb for more than thirty-odd years, comrades keep an eagle eye not just on each other, but on each other’s families and friends.

Her whole-timer husband Badshah Alam had been in active Left politics since the 1967 general elections. Two years later he became a member of the CPI-M, and then Democratic Youth Federation of India’s (DYFI) Calcutta district secretary. In 1983 Badshah was elevated to the post of the first CPI-M secretary of Padmapukur local committee, which included Beck Bagan and Bhowanipur – areas with highly diverse economic, religious and linguistic populations. His conflict with the party began after the Left Front, completing its second term in power, started shifting its priorities from the poor to the powerful vested interest groups – the land mafia and realtors. ‘The so-called class enemies were being wooed by key personalities in the party. Badshah’s differences grew with party leaders who wanted him to yield to money power. The strained relations exploded in 1990,’ said Chandrayee.

Following a brutal attack on Mamata Banerjee on 16 August 1990 by CPI-M workers in Calcutta, an influential section of the Calcutta District Committee wanted Badshah to make statements according to their diktat, contradictory to the truth. Already in an uneasy co-existence with the party, Badshah’s refusal led to his expulsion in 1991. `We knew if we compromised nothing would happen but we were determined not to. We were also aware that the party was making an example of Badshah’s expulsion to rein in other restless workers,’ said Chandrayee. The party accused Badshah of making money from the Muslim-dominated area of Padmapukur – an important one on the CPI-M’s list of local committees.

A visit to Chandrayee’s flat inside an alley in the Bek Bagan area would leave you wondering why Badshah and his family would choose to inhabit such a cramped place, when they, according to the CPI-M, had stockpiled such wealth. A narrow flight of tacky, ill-lit stairs takes you upstairs. For additional space Badshah had turned the roof into a kind of a make-shift room where you could cook in one cornet In the middle lay a few chairs. Sitting here Chandrayee and I chatted, returning to the events that changed the drift of her life.

‘After Badshah was expelled someone close to the party visited us. As he entered our home, he could not hide his surprise. He asked me “Is this where Badshah Alam lives?”’ since nothing in that humble flat suggested a hidden stash. With the expulsion began the party’s hounding of the family, economically and emotionally. `The party attempted to disrupt our family life. It spread rumours of our divorce. Badshah’s siblings were all party members. The party engineered a rift within the family,’ said Chandrayee. ‘We went through hard times. Could not send our two sons to the best schools. Virtually overnight people we were familiar with and knew for ages stopped recognising us,’ she added. Though she had not expressed any wish to sever association with the CPI-M, the party refused to renew her membership, throwing her into the ‘guilty by association’ lot.

Mamata Banerjee was attacked in 1991 by communist party goons. Photo Credit: AITC Official

That was not all. The CPI-M began to squeeze Chandrayee out of the court where she practiced. ‘The party stopped giving references for the public sector cases that used to come to me from different districts. State government briefs which had been dwindling from 2000, finally stopped in 2004. These have again begun to come to me after Nandigram in 2007.’

‘We went through hard times. Could not send our two sons to the best schools. Virtually overnight people we were familiar with and knew for ages stopped recognising us,’ she [Chandrayee] added. Though she had not expressed any wish to sever association with the CPI-M, the party refused to renew her membership, throwing her into the ‘guilty by association’ lot.

A year following his expulsion, Badshah and some of his ‘axed’ comrades formed a group, Marxbadi Kendra, trying to consolidate other Left forces in a common platform against the Left Front’s misrule. It did not take long to realise that the CPI-M would not allow them to function democratically. By-elections to Calcutta’s Ballygunge Assembly seat were held that year. The CPI-M fielded Rabin Deb, and Marxbadi Kendra, Swapan Chakraborty, once a popular CPI-M councillor, later thrown out by the party. ‘That election experienced unprecedented rigging, resulting in a CPI-M victory by a vote margin of 30,000. The sitting CPI-M MLA, however, had won by just 1500 votes,’ said Chandrayee. She described the way cadres from all parts of Calcutta poured into the constituency and the violence that followed. `Badshah protested when voters of Swinhoe Lane were prevented by the police from entering the polling station. In retaliation the police threw him into the van took him into “safe custody”. When the deputy superintendent came he found Badshah sleeping. Throwing him on the floor, he began hitting him, opening his eyes with his boot. All along the DSP shouted: “Take dekhte hobe, police manusher upore (you have to concede police is above the common man).”‘ ‘At about 9.00 p.m. I went to the barracks and found Badshah with boot marks on his face, injured and unattended. After my written complaint, he was given medical attention at 1.00 a.m.,’ she added. A case is still pending against Badashah, the trial continuing since 1996.

Marxbadi Kendra, however, proved a short lived experiment as Badshah joined the BJP in 1997, which seemed to him the only party capable, at that time, of taking on the CPI-M. ‘I cannot say the decision made me happy. But he needed a political platform,’ said Chandrayee. Quitting the BJP in 2007, Badshah joined the land movement led by Siddiqullah Chowdhury, secretary of the People’s Democratic Conference of India (PDCI). He found the agitation for land more effective.

After more than a decade Chandrayee went with her father Sadhan Gupta to Alimuddin Street following the death of Nripen Chakraborty. The veteran communist leader expelled by the party had been taken back a day before his death. His body was kept at the CPI-M headquarters. `Nripen Chakraborty had lived at our 47 Theatre Road residence for some time. He enjoyed being with the family, playing with the kids. When he passed away, Baba wanted to go to the party office. I went with him. It was strange. Nobody would talk to us. We just stood there. After some time Anil Biswas came and spoke with me. As if on cue others followed, though not Buddhada (Buddhadeb Bhattacherjee). He did not even bother to speak to baba,’ said Chandrayee.

Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee was the Chief Minister of West Bengal from 2000 to 2011.

Within a year of taking over the reins, the CPI-M had become a ubiquitous presence in West Bengal, sometimes with open aggression, but more often a lurking shadow — a snooping, hovering third eye.

Maimoona, an acquaintance of Chandrayee, tells of how her husband, a party member in Beck Bagan, was a victim of the snooping brigade. `The Municipal Corporation was proposing to hand over Park Circus Market to Reliance. Siddiqullah of PDCI had organised a meeting protesting the move. My mother wanted to listen to Siddiqullah. So I took her to the meeting. We sat at the back’.

Within a year of taking over the reins, the CPI-M had become a ubiquitous presence in West Bengal, sometimes with open aggression, but more often a lurking shadow — a snooping, hovering third eye. Maimoona, an acquaintance of Chandrayee, tells of how her husband, a party member in Beck Bagan, was a victim of the snooping brigade

‘At the party’s local committee office the next day a CPI-M leader asked my husband if he had attended yesterday’s meeting. My husband said no. The leader promptly fished out a photograph of me sitting with my mother at the meeting! Party workers were actually present at the meeting, snooping, taking photographs,’ said Maimoona.

`The CPI-M is calling us communal. But a day before the meeting party cadres went around Beck Bagan saying Sidiqullah was going to hold a meeting of Muslims and the Hindus should stay away,’ said Chandrayee.

*

Since the 1980s much of the party machinery was wielded through suspicious means. One of these important ‘bonding’ activities was party ‘collection’. No longer were party members assessed by their organisational skills, and the ability to attract new members. The CPI-M now seemed to measure the political worth of its members from their fund-raising skills.

Every unit of the party – student, youth, women and trade union – was caught up in the collection drive, ‘Collecting funds and mobilising people for rallies and meetings are two of my main political activities,’ said Aparna De, a former attendant in Calcutta’s Modern High School. A member of the party and the Ganatantrik Mahila Samiti since 1982, Aparna went around with her comrades on house-to-house, shop-to-shop fund collection. ‘We have shops allotted to us and the collections can range between Rs 5 to Rs 100. We also visit people at home and at clubs. No, there is no coercion. They give the money because they love our party’.

If this is the state of affairs with those who are the party’s ‘own’, one can easily imagine what happens to those who do not belong there. Often, they simply disappear.

The list of missing persons has grown too long to be dismissed or taken lightly. West Bengal, in the last two decades, has been home to many mysterious deaths and inexplicable disappearances, explained by theories of political conspiracy.

I remember Manisha Mukherjee from my years in the Department of Archaeology. Most students on the campus knew her – a slim, attractive student, who sat on the steps and joined our addas. An active member of the SFI, I guess it was part of Manisha’s ‘mass work’ to chat with the students. But she had a genuine, endearing friendliness, and it came as a shock more than a decade later to learn about her disappearance. In December 1994, Manisha, then Calcutta University’s deputy controller of examinations, suddenly vanished from her house. As of May 2010, there is still no word of what happened to her. Manisha’s mother, Chinu Devi, knocking on every possible door, trying to get news of her daughter, is believed to have told the police where she could be hiding. Said a news report, ten years after her disappearance: ‘Calcutta University’s deputy controller of examinations Manisha Mukherjee disappeared from her house in December 1994. Her mother, Chinu Devi, initially gave the police a lot of information about the possible places where she could be hiding, apparently to save herself from “some university people” who wanted to kill her, as she knew about a lot of corrupt deals on for her all over eastern India, and amidst talk of political “fixing”, Manisha remained untraced. But the case file, the thickest with the Calcutta Police, hasn’t been opened for a while.’

The list of missing persons has grown too long to be dismissed or taken lightly. West Bengal, in the last two decades, has been home to many mysterious deaths and inexplicable disappearances, explained by theories of political conspiracy.

Or take for example, this story: On 30 October 1993, a police team led by Harmanprit Singh, then Additional Superintendent of Police in Hoogly, picked up Bhikari Paswan, a jute mill worker from his residence. That was the last that people heard of Bhikari Paswan. The case was handed over to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) but the inquiry resolved nothing. Why was the jute mill worker picked up from his home? Where did he disappear to?

Bhikari Paswan was a casual worker in Victoria Jute Mill in Telinipara, in the Hoogly district, which witnessed massive workers’ unrest following unpaid wages, Provident Fund and bonus dues. The workers’ anger was directed, in large part, against the unions. Following the outbreak of clashes and the police crackdown on agitating workers, Bhikari Paswan was allegedly one of the workers picked up and sent to police custody. Though the police denied arresting Paswan, the Association of Protection of Democratic Rights, investigating the case, concluded in its report, ‘in the light of the facts which have come to light during the investigations, it can be concluded that Bhikari Paswan was indeed picked up by the police party from his residence on the night of 30/31 October 1993 at about 12.30 a.m. His whereabouts since then are not known.’

Bhikari Paswan was a worker at the Victoria Jute Mill.

In an earlier incident in the mid eighties, CPI-M goondas attacked, molested and murdered a senior officer of United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), severely hurting another officer of the Central government in Bantala, on the outskirts of Calcutta. ‘The reason was that these two lady officers had detected huge embezzlement of UNICEF funds and relief materials by CPI-M functionaries. When the matter was reported to the then Chief Minister Jyoti Basu, he reacted saying: “Such incidents happen, don’t they?” And that was the end of the matter.’

In 2009 the sessions court at Ranaghat in Nadia convicted four persons in connection with the looting of a marriage party in February 2003, in which the driver of the bus was killed and six women passengers raped. However the court let off 17 others, including two local CPI-M leaders Subal Bagchi and Saidul Islam, for lack of evidence. ‘Bagchi was then a member of the CPI-M zonal committee from Ranaghat and Islam was the pradhan of Kamalpur gram panchayat. A large number of witnesses had turned hostile in the case affecting the prosecution. Ninety per cent of the witnesses out of the 158 turned hostile, said Dilip Chatterjee, the counsel of the state government.’

In an earlier incident in the mid eighties, CPI-M goondas attacked, molested and murdered a senior officer of United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), severely hurting another officer of the Central government in Bantala, on the outskirts of Calcutta… ‘When the matter was reported to the then Chief Minister Jyoti Basu, he reacted saying: “Such incidents happen, don’t they?” And that was the end of the matter.’

In fact membership has become so easy that a person like Subal Bagchi, and many more like him nesting with the party, could not only enter the membership ranks but elevate their stature to that of a ‘leader’. These incidents speak volumes for the slackening of the political and ideological rigour that had perhaps once given a place of distinction to the CPI-M, setting it apart from the wider political class.

*

The stories of political murders and disappearances in West Bengal are endless. And they do not usually come out into the open. But sometimes they do. To be more precise, of late they have started coming out. This is no doubt due to the winds of change blowing in the state, where the domination of the CPI-M and the Left Front is breaking. For the first time the effect of the ‘fear factor’ is declining. The well-known Rizwanur Rehman case was a turning point.

Sujato Bhadra—member of the Association for Protection of Democratic Rights (APDR) and a key person to blow the whistle on the Rizwanur murder case—can, by the mere whisper of his name, raise Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee’s blood pressure by several notches. Given the CPI-M’s chilling disregard for transparency and democratic norms, Buddha’s revulsion towards Sujato is predictable. But the genesis of the bad blood between the two individuals, the omnipresent chief minister and the much vilified human rights activist, goes back to an incident that begs to be told.

In 1992 Jyoti Basu hosted a conference as a prelude to instituting a Human Rights Commission in West Bengal. Ironic, since the comrades have a human rights record humiliating enough to make them hang their heads in shame. Custodial deaths stand at a record high under the Left Front’s vigilant eye. The state government bears the infamy of extricating the police whenever they are in deep trouble. Thirty-three years of uninterrupted rule gave the CPI-M ample time and expansive leverage to make ‘party cadres’ out of the state police, waiting to be co-opted. Arrogance running high, the party’s writ turned into commands to which every ancillary of the state bowed its head. The party feared no one.

Custodial deaths stand at a record high under the Left Front’s vigilant eye. The state government bears the infamy of extricating the police whenever they are in deep trouble. Thirty-three years of uninterrupted rule gave the CPI-M ample time and expansive leverage to make ‘party cadres’ out of the state police, waiting to be co-opted.

Before instituting the State Human Rights Commission the government put out a notification in newspapers about a conference on human rights—an open meeting anybody could participate in. `We decided to attend the meeting and made the necessary preparations,’ says Sujato. APDR members charted out a list of human rights violations in West Bengal, distributing it among the speakers a day before the conference. ‘I even gave one to Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee’s secretary, who happens to be my cousin,’ says Sujato.

The next day APDR members turned up at Shishir Mancha, the venue of the meeting. Naranarayan Gooptu was delivering the inaugural address, in the course of which he denounced the manner in which the Congress government in Tripura had hushed up reports on mass killing probed by a judicial commission. I raised my hand. Jyoti Basu was on the podium. He did not want to allow me my question. But Dr Bela Dutta Gupta (former chairperson, West Bengal Women’s Commission) sitting next to him, allowed, me. I drew the speaker’s attention to similar instances in West Bengal in which the state government had swept judicial commission reports under the carpet.’

Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, then minister in charge of the police, information and culture (a pungent cocktail!) was not on the podium. The moment the question rang out he rushed to the dais, took the mike, and asked the person asking the question to meet him outside the hall. ‘This sparked a furore. APDR members scattered in the hall rose to their feet, protesting the muzzling of questions at a seminar. We walked out.’

Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee after the 2006 Assembly Elections Victory.

‘The moment I stepped out of the hall Buddha came towards me—rolling his sleeves and asking who had raised the question. When I identified myself he asked me to repeat the question. As I did so there was an altercation. Buddha signalled to the police who started to thrash me.’

Amid all this, unnoticed by most in the audience, was Maitreyo Ghatak, well-known litterateur. ‘None of us saw him,’ says Sujato. When he was being whisked away from the seminar hall Ghatak voiced his protest. Raising his hand, he stood up and kept repeating in a well-mannered tone: `Seminare prashna kora to anyay noi’ (It is not a crime to raise questions at a seminar).

It was rather funny. This man who had just casually walked into the meeting got caught in the fracas. As Buddha ordered the police to arrest us, he also gave an order, to arrest Ghatak, who passed off unrecognised in the ruckus. We were in the police van when we noticed the author sitting with us. I asked him “Aaapni ekhane ki korchhen?” (What are you doing here?) He looked at me and said: “All I said was that it’s not a crime to ask questions at a seminar!”‘

The police van disgorged the APDR members and Ghatak at the Lai Bazaar headquarters. Here the police discovered they had messed up by rounding up Ghatak in the melee. The police then would not register a case. They just asked us to leave their headquarters. We refused, insisting our names had to be recorded since we were arrested,’ narrates Sujato.

‘The moment I stepped out of the hall Buddha came towards me—rolling his sleeves and asking who had raised the question. When I identified myself he asked me to repeat the question. As I did so there was an altercation. Buddha signalled to the police who started to thrash me.’

The arrest could not be stamped out of the public glare. The state government was in a spot. It was learnt Buddhadeb later attempted a conciliatory meeting with APDR. It was also subsequently learnt that as chief minister he refused to meet any delegation that had Sujato in it.

Of its many baffling, conflicting cultural traits, Bengal’s attitude towards women is worth a discussion. Bengalis like to believe they are intrinsically ‘superior’ vis-a-vis other communities in the way they treat their women. A popular myth in wide circulation propagates that the women in this state are treated with unique respect, absent in most ‘uncivilised’ parts of the country. Marxists would like to claim a large share of this glory, combating patriarchy in addition to being the most deserving inheritors of the legacy of the ‘Bengal Renaissance’ and the participation of women in the national movement. The Left movement, according to the communists, humanised gender relations. The ground situation, however, testifies to a different fact: patriarchy is as native to Bengal as its inalienable Rabindrasangeet; male chauvinism as deeply entrenched as the roots of Left politics.

The qualities that Bengal in general and the CPI-M in particular would like to bestow on themselves are rather imaginary – fond illusions in the light of the collective experience of Bengal’s women. The tragedy is compounded by the fact that the ruling Communist Party, which perhaps could have initiated a different culture, is itself yet to break free from male chauvinism.

During my years in Calcutta as an SFI activist I remember my exasperation over the sexist division of labour that would invariably mark organisational conclaves. In 1982, preparations were underway for the SFI conclave in Dum Dum. We were meeting in Calcutta University, deciding on delegation of responsibilities. The dadas instructed us women to come in Bengal’s traditional red-bordered white sarees; it was also our duty to put tikas on foreign delegates and shower flower petals on them. As if this were not galling enough we were also given the duty of distributing water! Questioning such stereotypical division of labour would usually brand me a `feminist’ – as if it were a curse!

The idea of respect for women goes with the expectation of conforming to a stereotypical image of womanhood – women primarily as mothers and nurturers – as a necessary pre-requisite for earning any form of social regard. Essentially conservative, the CPI-M unfailingly stays away from critiques of the patriarchal family, let alone from controversial issues like gay rights, sexuality – now dominant strands of feminist discourse. Like much of our political and social class, the CPI-M too fights shy of discussing, much less taking a decisive position on the rights of marginalised groups, lesbians, homosexuals, transgender persons. Instances of this crippling reluctance are many.

Let’s take a look at some of the scenes witnessed on the floor of Parliament. The somewhat desultory protests in a somnolent post-lunch session of Lok Sabha, following the attack on Deepa Mehta’s Fire, indicate the social psyche of our secular political class.

The idea of respect for women goes with the expectation of conforming to a stereotypical image of womanhood – women primarily as mothers and nurturers – as a necessary pre-requisite for earning any form of social regard. Essentially conservative, the CPI-M unfailingly stays away from critiques of the patriarchal family, let alone from controversial issues like gay rights, sexuality – now dominant strands of feminist discourse.