Papering over the cracks of history is seen to be a means of survival. Accounts of conflict, massacre and exploitation are often glossed over because a group of people, such as a nation, must ‘move forward’, even if the survivors who have suffered the brunt of such injustices, and their successors—brought up on tales of trauma—have to live with a memorial schizophrenia where what they remember is considered unreal by others.

Or, as Agha Shahid Ali put it: “My memory keeps getting in the way of your history.”

But a present built on the foundation of a cracked past is bound to wobble, and when the wobbling acquires enough of a magnitude on the Richter scale the cracks recur. Yet, we carry on building, floor after floor, unmindful of those having to trod upon paper and fall through the fissures, till this wobble becomes an earthquake, collapsing what was built to look like a sturdy edifice.

For, when you do not listen to history, it simply repeats itself.

So the cracks must be filled. Ideally with redress. If not then, at least, with remembrance— a collective and genuine recognition of the trauma of our own as well as those we have othered with constructed memory. If we don’t, into those cracks—created by a ‘Police Action’ in Hyderabad state in 1948, say, or a Marichjhapi Massacre in West Bengal in 1979—will seep horrors of the likes of those which swept Delhi in 1984, Bombay in 1992-93 and Gujarat in 2002. The deepening of these cracks will, in turn, lead to further deepening, and so on and so forth. Real history, unheard, will repeat itself.

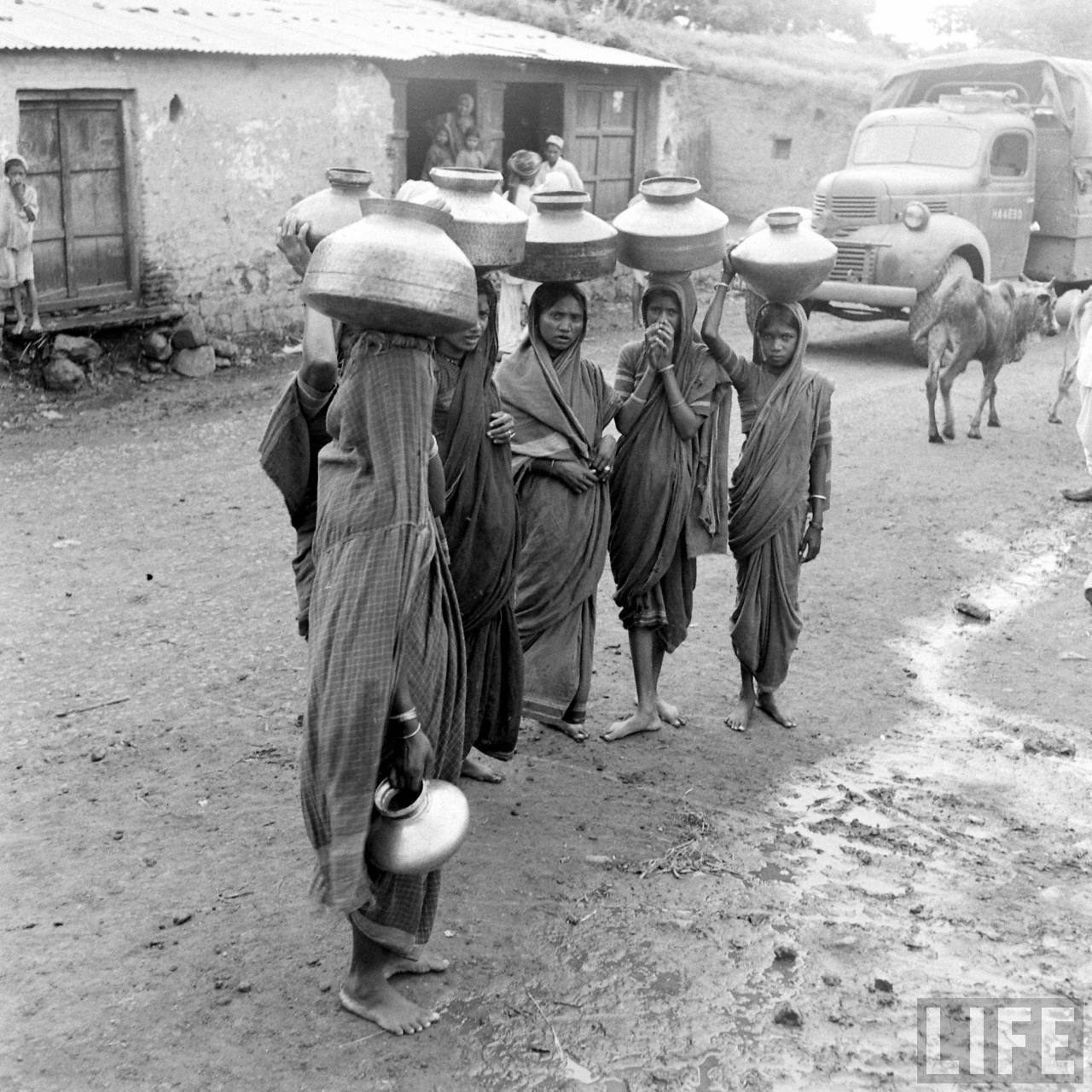

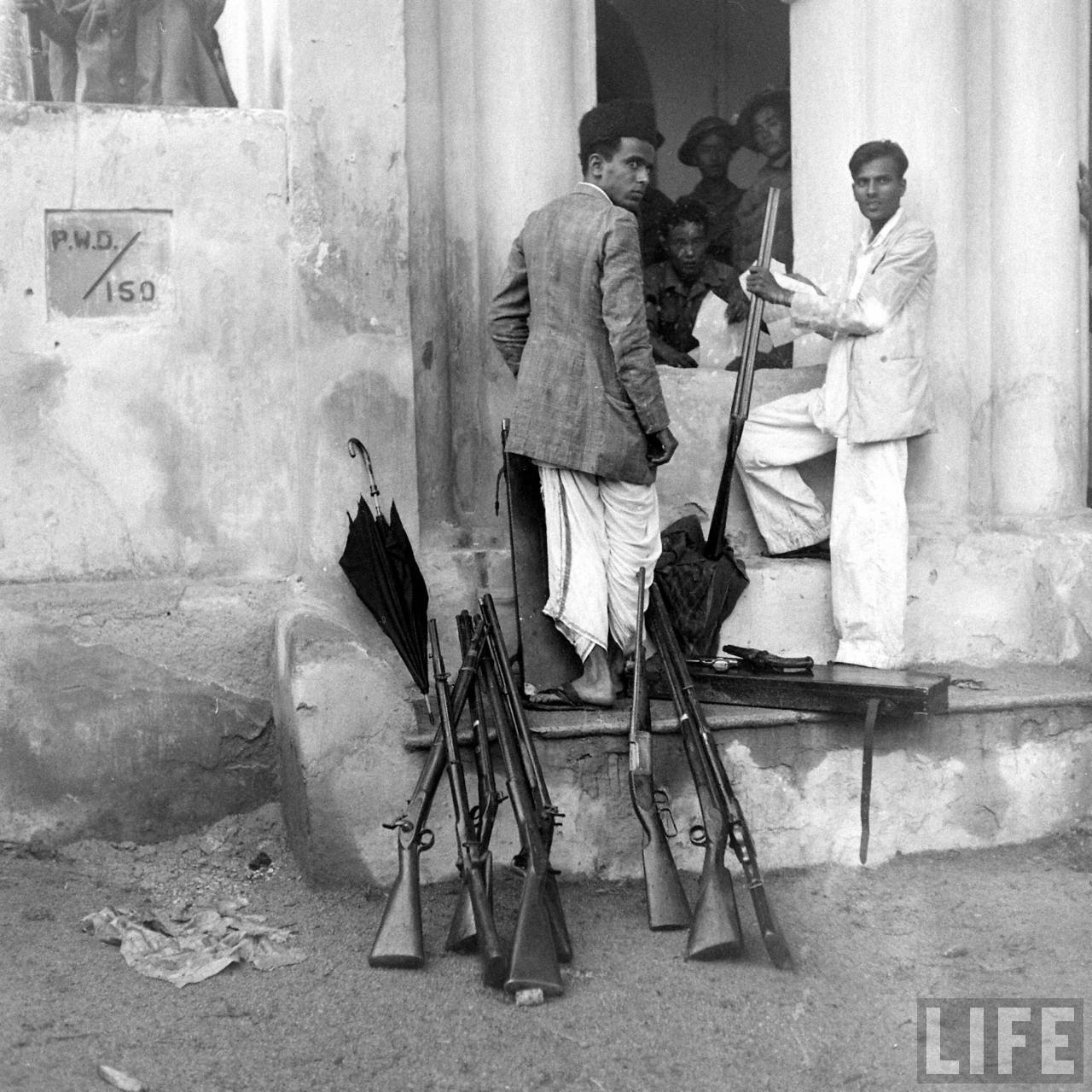

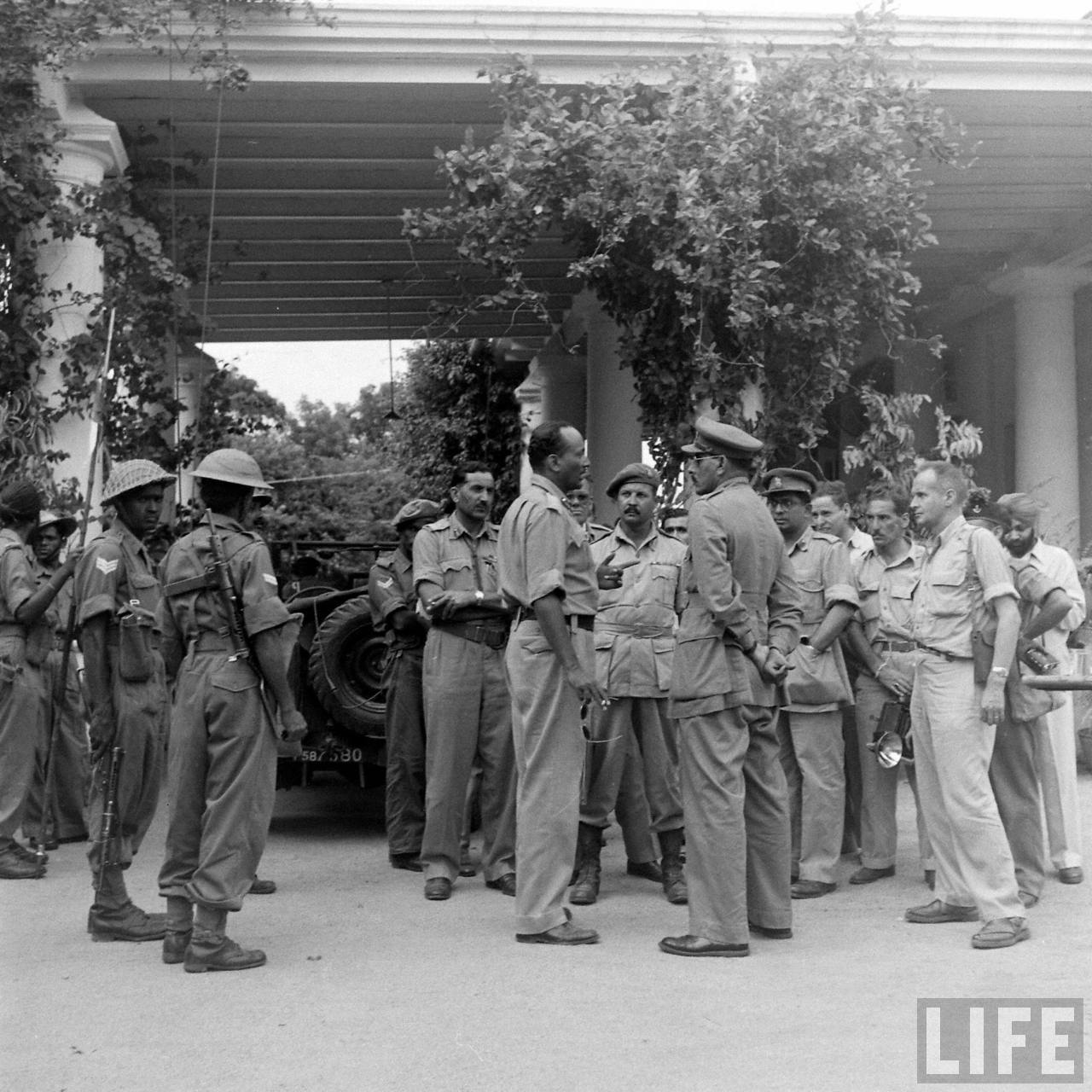

In this excerpt we revisit the events which accompanied the princely state of Hyderabad joining the Indian state in 1948. On September 13th, the Indian army entered the erstwhile princely state and, within five days, conquered the territory. The operation was codenamed ‘Operation Polo’ and known popularly as the ‘Police Action’ (among locals it was referred to, plainly, as ‘the Action’). The Nizam of Hyderabad surrendered to the Indian Union on the 17th of September. Robert Lubar, reporting for Time magazine, wrote, “Everyone is satisfied… Hyderabad, which was never really out of India, is now indisputably part of India. There have been no terrible outbreaks of communal violence… All in all, it is one of the shortest, happiest wars ever seen.” This version of events, characterising the annexation as bloodless and efficient, is the primary narrative that occupies popular memory today.

In 2013, however, the declassification of a report that had been effectively buried, in ‘national interest’, brought to light history from the shadows.

The Pandit Sunderlal Committee—comprising Pandit Sunderlal, Kazi Abdul Ghaffar, Maulana Abdulla Misri, and Farrouk Sayer Shakeri—had been formed by Nehru after he heard rumours of violence in Hyderabad during the Police Action. It was set up to survey existing conditions in the state and recommend what was needed to establish communal harmony.

Here is an excerpt:

“In these Districts as everywhere else in the affected areas of the state, communal frenzy did not exhaust itself in murder alone— murder which does not appear to have spared women or children. Loot, arson, desecration of mosques, forcible ‘conversions’, rape, abduction of women (sometimes out of the state), seizure of houses and lands followed or accompanied the killing. Tens of crores worth of property has been looted, destroyed or seized from their owners. The sufferers everywhere were the Muslims— in the hopeless minority of nearly 1 to 10.

“The perpetrators of these atrocities were unfortunately not limited to those who had suffered at the hands of Razakars, nor only to the non-Muslims of Hyderabad state. These latter were aided and abetted by individuals and bands of people, with and without arms, who had infiltrated through in the wake of the Indian Army from Indian territory across the border. We found definite indications that a number of armed and trained men belonging to a well-known (? notorious) communal organisation from Sholapur and other towns on the Indian side of the border, as also quite a few local and outside Communists participated and in some cases actually led the rioters, killers and abductors.

“Duty compels us to add that we were informed by unimpeachable and independent parties of instances—happily, isolated ones—in which men belonging to the Indian Army and the local police were seen taking part and sharing the loot.”

Reporting from Latur District, the committee wrote, “Out of a population of about 10 thousand Muslims, we found barely 3 still there. Two to three thousand had been killed and the rest had run away escaping with little besides their lives, and ruined financially.”

The excerpt below is from the introductory chapter of Afsar Mohammad’s Remaking History: 1948 Police Action and the Muslims of Hyderabad, a social history pieced together from oral histories of both Muslims and Non-Muslims, as well as a wide variety of written sources and historical documents which, according to Taylor Sherman, “paints a beautiful and nuanced new picture of Hyderabad in the 1940s and 1950s… In listening attentively to these voices, Afsar Mohammad reveals the dilemmas faced and the possibilities that opened up for Muslim belonging and for Hyderabad’s unique shared culture in the tumultuous years surrounding the Police Action in 1948.”

Reading the Pandit Sunderlal Committee Report one might be prompted to raise an eyebrow, or two, at the participation of “Communists” in the violence. While this needs to be probed further, Mohammad’s introductory chapter provides some context:

“In addition, this particular period also witnessed numerous political and religious transformations related to the Hindu-Muslim question. The Nizam of Hyderabad and the Razakars had started circulating the idea of Azad Hyderabad (Independent Hyderabad) and a ‘Muslim State’. Some writers used the Telugu term Mahammadiya rajyam (literally, ‘Mohammadan State’) to claim their independent political authority. On the other hand, the Leftist parties undertook an armed guerilla movement known as the Telangana armed rebellion (Telangana sayudha porātam in Telugu) between 1946 and 1951, against the locally dominant feudal system. Between these two modes of political violence and the battlefield of diverse viewpoints, Telangana was struggling to produce its own tools of political transformation and a local version of modernity.”

While further investigation is warranted it seems that, on the back of the Police Action, anger against Razakars and the Nizam, was redirected against all the Muslims of Hyderabad state. The second chapter of Mohammad’s book is titled ‘All Muslims Are Not The Razakars’. It opens with a quote from Razia Begum, a witness of the Police Action, speaking about young Muslim men and women who “suddenly became suspects… many of them… [fled] from their homes… leaving everything.” She adds: “They just wanted to live somewhere rather than dying in the bloody hands of the Razakars and Hindu fundamentalists”.

In this excerpt, Mohammad also examines the views of interlocutors who liken the time of the Police Action to “another partition” and studies the formation of a political minority of Muslims in this region in the context of the partition of India and Pakistan.

But, perhaps most significantly, he quotes Abdul Qudas Saheb, an interviewee, who says, “The violence followed by those five days of invasion shattered our lives— took away the tehzeeb of our everyday lives.” Mohammad digs deeper into this idea of ‘tehzeeb’ to proceed to an urgent question: that of modern Muslim identity in the region. He cites historian Magrit Pernau who critiques studies which “assume that Muslim identity is primarily informed by religion and that the creation of a community on the basis of religion surpasses and eclipses other forms. This assumption—that the non-religious identities of Muslims are only tenuous or even entirely undeveloped—probably also explains why there are relatively few studies dealing with Muslim women, workers or the Muslim middle classes, despite the flourishing of gender and social historiography in India.” In these times, when reports on the Telangana elections routinely distil Muslim identity into voter blocs, such inquiry begs attention.

At the end, the methodology Mohammad employed in collecting oral history, something followers of Subaltern Studies might find interesting to read, has been outlined.

The Police Action was an end of many good beginnings in our lives. We lost not only many friends, our personal careers, and houses, but also and most importantly, the tehzeeb of our shared culture. If someone says it is just about few Muslims, no, not at all. It’s a pain about the entire community of the then Hyderabad and Telangana.

—Abdul Quddus Saheb, September 20, 2006.

In September 2006, during the field research for my previous book The Festival of Pirs, I took an early morning bus to Karim Nagar, an urban town famous for the public rituals of Muharram. Almost 200 miles away from the city of Hyderabad, this urban town has a significant Muslim population and was also greatly influenced by the Shi’i Islamic practices of Hyderabad.

In Karim Nagar, I met 78-year-old Abdul Quddus Saheb, who began our conversation by talking about the songs of his youth during Muharram, the commemorative event of the martyrdom of the Prophet’s family. After a while, he surprisingly took a detour just to talk about the Police Action of 1948. Being a young man of around twenty at the time of this violent event, Quddus Saheb was one of the witnesses of that traumatic era and the consequent divisive politics that partitioned Muslims and Hindus. Many of his memories, as I document here, narrate the story of the new generation of Muslims whose everyday lives and future dreams were brutally shattered by the Police Action of 1948.

According to Quddus Saheb, “It was a nightmare for us, as every Muslim in the Hyderabad state had suddenly become an enemy of the people. We were experiencing the height of every form of hatred and could not even step out of our homes.” Growing up in such a hateful environment, Quddus’ own story offers a lens through which to glimpse both the external and interior struggles of many Muslims during this period. Before this tragedy, Quddus Saheb was known for his mesmerizing performance of the songs of Muharram, both in Telugu and Urdu. When the Police Action was executed between September 13 and September 17, 1948, along with many other traditions, this narrative performance, according to Quddus Saheb, “started fading out” too. He recalled many memories from this period. During my interview, Quddus said:

Abdul Quddus Saheb (AQS): In those days I would sing the songs of Muharram both in Urdu and Telugu. I was not even twenty and so enthusiastic about this performance as I strongly believed in its ability to connect Hindus and Muslims. There was no separation between Hindus and Muslims either in daily life, or during these religious events. The people of my town or any village around this place never made any distinctions when it comes to Muharram. I thought that was an ideal setting, and I had also trained several groups of the performers of the songs. It’s unfortunate now that I also witnessed a wall of separation and people start using the terms such as “Hindu Muharram,” and “Muslim event.”

Afsar Mohammad (AM): Do you remember when exactly this separation happened?

AQS: In my understanding, it was all either before or after the Police Action, 1948! The violence followed by those five days of invasion shattered our lives— took away the tehzeeb of our everyday lives. It was nothing short of any war, the jung, yuddham. I am not talking just about the Muslims, but the entire community of Muslims and Hindus.

Whereas Qudus Saheb’s usage of the terms jung and yuddham, meaning “battle”, for the Police Action is key for my argument in this book, I was also reflecting on how he emphasized the term tehzeeb, and towards the end of the conversation, we returned to the same idea:

AM: I want to learn more about the idea of tehzeeb in this context. How do you make a connection here?

AQS: The tehzeeb of our town’s life comes from Muharram and many other devotional practices that we shared. That’s where we learn about co-existence and sharing milan sar, “way of life” [milan sar in Urdu and kalupugolu in Telugu].

Then he suddenly switched to Telugu to say: “idanta a yaksan taravata cediripovadam suru ayindi. jumg ante yuddham vaccimdi” (All this had begun to shatter after the Action. The battle had started!). Somewhat prompted by his words, I took on the task of researching the archives of written and oral sources about the Police Action of 1948. These expressions from the oral accounts also compelled me to start meeting different kinds of people from various parts of the city and Telangana. First, I had intended to talk to the primary witnesses of the Police Action, popularly known as “action” in public memory and Polisu Carya in the political writings on the state of Hyderabad. Many interlocutors consider this as another Partition and narrate the stories of violence and trauma that left many Muslims homeless and displaced. Nevertheless, they were also conscious of the politics of remembering and forgetting. Initially, I asked myself and these witnesses two apparently simple but actually quite complicated questions: Why and how was such a traumatic event ignored by mainstream historiography? How does the politics of mentioning, forgetting, and remembering play into this negligence, denial, or misinterpretation of this violent event?

Whereas a few studies offer more evidence about the political tensions between the nation-state and the Hyderabad state, this book focuses on how such processes resulted in the making of a new Muslim discourse in the wake of the Police Action. It proposes that this historical event was a commingling of multiple aspects that had begun with the tensions between the making of the new nation and the question of Muslim representation in 1948 and then extended further into the recent debates about the strategic minoritization and isolation of Muslims, particularly those in Hyderabad state. Several studies discuss this formation of the political minority of Muslims as related to the Partition of India and Pakistan.

This book begins by questioning various ways of the mainstream historiography that privileged the master narratives of nationalism, the Telangana armed rebellion between 1946 and 1951, and the Telugu linguistic state formation of 1956. Those narratives totally ignored the violent event of the Police Action and the Muslim question. Despite many disenchantments and heavy losses, I argue, the Hyderabad and Telangana situation offers a model for how Hindus and Muslims responded and emerged out of a crisis by offering new strategies such as urbanization, Islamic reformism, and Muslim belonging to resolve the conflict between Hindus and Muslims. This model is much needed today in India, a country ridden with increasingly divisive politics and the rhetoric of Islamophobia. Informed by recent studies on diverse Muslim identities, Islamophobia, nationalism, religious conflicts, majoritarianism, and the post-secularist turn along with the related debates in contemporary literary and cultural engagements, I will discuss multiple dimensions of Muslim identity and religious politics as articulated in various literary narratives and oral histories throughout this book. Unlike the dominant historiography, these sources offer evidence for the mutuality of the shifting Muslim discourses and the rise of the Muslim public sphere, including specifically local Telugu and Urdu hybrid aesthetics in post-1940s Hyderabad. In conversation with global Islamic movements and activism, these locally produced aspects define a new framework to understand the complexities of the Hyderabad and Telangana-based Muslim identity.

By focusing on how this specific period also was successful in producing a new set of modern prose writings in Hyderabad city and Telangana, this book argues that the Muslim question has acquired many nuanced features as it journeyed through different phases of the public sphere. This crucial turn was reflected in both oral and written cultures that emerged in rural and urban locations thus representing a constant flow between the city of Hyderabad to even remote regions of Telangana. Many of these themes from the Police Action are now being revisited and retold against the backdrop of the post-2000 Telangana state movement. In many ways, these connections take on deeper interpretations as the process of retrieval and reconstruction of the historiography of the Hyderabad state and Telangana engenders multilayered discourses.

By documenting the stories of diverse groups of actors and agents in this historical event, I analyze varied understandings of Muslim contextualization between 1940 and 1950. However, it is quite intriguing to define a “Muslim” context within the literary sphere of Telangana and Hyderabad. Many “Hindu” writers, including Nelluri Kesava Swamy (1920-1984), Bhaskarabhatla Krishna Rao (1918-1966), Kavi Raja Murthy (1926-1985), Dasarathi Krishnamacharya (1925-1987), and Samala Sadasiva (1928-2012) whom we meet in this book, always deliberately located themselves in a liminal space which was neither Hindu nor Muslim. In addition, they were all writing in Telugu and Urdu at once while participating in various literary, cultural, and political organizations that promoted a shared Hindu-Muslim tehzeeb. When we read their texts and life stories closely, as I do in this book, we understand that their voices have always been much closer to the idea of Muslimness, thus owning every aspect of Hyderabad and Telangana Muslim practices. How one non-Muslim individual or writer or social activist could locate himself or herself within this Muslim public sphere remains a key question. In the process, the definition of Muslim belonging within this local cultural and religious milieu complicates any understanding of the singular definition of Muslimness by challenging nationalist, secularist, and even leftist readings. Such readings, in fact, have origins in the immediate reports published after the Police Action, as I briefly discuss in the following pages.

On August 15, 1947, as the new nations of India and Pakistan prepared to negotiate land and power, their borders were bloodied by the violence of the Partition. But India’s territorial disputes were not limited to its western and eastern boundaries: instead, the citizens of the princely south-central state of Hyderabad were experiencing an intense political and religious conflict between the union government of India and the princely state of Hyderabad.

A year later in 1948, to control the regional power of the Nizam of Hyderabad and his private army known as the Razakars, the union government of India deployed the central army for a violent intervention under the code-named “Operation Polo,” popularly known as the “Police Action.”

The five-day military invasion of Hyderabad state resulted in tragic consequences, although the media projected it as a “happy war.” Time magazine of London specifically assigned a correspondent to cover this event and published extensive reports. The very first news story on September 20, 1948 began:

Time correspondent Robert Lubar, together with a Life reporter and photographer, set out in a hired 1935 Ford to have a look at the war between India and Hyderabad. The Indian army had undertaken a “police action” (which it also called a “mission of mercy”) against Hyderabad where the predominantly Hindu population was ruled by a stubborn Moslem Nizam. The would-be war correspondent sped 180 miles towards the front, found that the war was over by the time they got there. All in all, it is one of the shortest, happiest wars ever seen. Cabled Lubar:

“Everyone is satisfied. The aggressive section of Indian public opinion has been appeased. Hyderabad, which was never really out of India, is now indisputably part of India. There have been no terrible outbreaks of communal violence.”

Efforts to retrieve the ordinary voices of Muslims against this background were hindered by the media politics of the late 1940s. In one of the stories, as I discuss in Chapter 1, Nelluri Kesava Swamy describes how two radio stations–a national station of the Indian government and a local station in Hyderabad-were busy broadcasting their competing versions of the news materials rather than the actual facts. The ambiguity and utter confusion created by the media exacerbated the havoc of this event. The historian Wilfred Cantwell Smith, who witnessed these developments in the city of Hyderabad, described the situation:

“On September 13, 1948, the Indian army, moving on five fronts, invaded Hyderabad; and in less than a week the conquest was complete. The Nizam’s army, apparently more of an exhibition than a fighting force, offered negligible opposition. There were relatively few battle casualties except amongst Razakars and other Ittehad civilian volunteers, who threw themselves in as a rather pathetic but devoted resistance. Off the battlefield, however, the Muslim community fell before a massive and brutal blow, the devastation of which left those who did survive reeling in bewildered fear. Thousands upon thousands were slaughtered; many hundreds of thousands uprooted.”

According to the Sunderlal Committee, which was appointed by Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of India, and led by Pundit Sunderlal and Qazi Abdul Ghaffar, “only three of sixteen districts in Hyderabad state were free of communal trouble.” Whereas the districts of Osmanabad, Gulburga, Bider, and Nander were the worst affected, Aurangabad, Nalgonda, and Medak had lost 5,000 in each district. The committee reported:

“We can say at a very conservative estimate that in the whole state at least 27 thousand to 40 thousand people lost their lives during and after the police action. We were informed by the authorities that these eight were the worst effected districts and needed most the good offices of our delegation. We, therefore, concentrated on these and succeeded, we might say, to some extent at least, in dispelling the atmosphere of mutual hostility and distrust.”

About the extent of the violence and deaths, Taylor Sherman noted:

“It is difficult to elaborate the scale and nature of the violence that occurred. The information available to the historian is incomplete, both because of the difficulty in capturing such events in historical documents. And because not all of the reports that were drawn up have been opened to public view.”

Indeed, for the most part such stories about the violence, migrations, and survivors remain unexamined in the history of Hyderabad. The suppression of the Sunderlal report, as the historian Omar Khalidi noted, was “due no doubt to its adverse comment on the conduct of the Indian army. Despite its first-ever disclosure of such violence during and after the Police Action, the Sunderlal Commission’s report remained “classified” until recently as the Indian government considered it to be harmful to “national interest.” In his book Hyderabad: After the Fall, Khalidi documented several reports and early writings about the Police Action, which he called “the Hyderabad Holocaust.”

Sardar Patel, the then home minister, who masterminded and supervised the entire Police Action, even went so far as to insist that there was no such thing as a “Good Will Commission” appointed by the government. According to the political scientist Noorani, the government of India also used its media and suppressed the hard facts of the entire action, convincing the authorities that “at times one has to close his (sic) eyes in the national interest.” … There were also reports about how Patel ignored even the warnings of Prime Minister Nehru, who clearly said: “One of the persistent charges made against us is that we intend to kill what is called Muslim culture. Hyderabad is known all over the Middle East as a city of Muslim culture.” Nevertheless… the grand narrative of nationalism ended up marginalizing and suppressing the Muslim side of the story. Recent studies by Taylor Sherman and Sunil Purushotham have presented more evidence for various aspects of violence during the Police Action. Purushotham’s 2015 essay Internal Violence: The ‘Police Action’ in Hyderabad and the 2021 book From Raj to Republic together document and analyze how internal violence became an “important engine of state formation” in post-Independence India. This side of the story of endless violence towards Muslims and the migrations and survival of Muslims is still marginalized in the dominant historiography of Hyderabad. Local newspapers like Inquilab, Zamindar, and Ehsan, as documented by Sunil Purushotham, had extensive coverage of this “Muslim butchering en bloc”.

In addition, this particular period also witnessed numerous political and religious transformations related to the Hindu-Muslim question. The Nizam of Hyderabad and the Razakars had started circulating the idea of Azad Hyderabad (Independent Hyderabad) and a “Muslim State”. Some writers used the Telugu term Mahammadiya rajyam (literally, “Mohammadan State”) to claim their independent political authority. On the other hand, the leftist parties undertook an armed guerilla movement known as the Telangana armed rebellion (Telangana sayudha porātam in Telugu) between 1946 and 1951 against the locally dominant feudal system. Between these two modes of political violence and the battlefield of diverse viewpoints, Telangana was struggling to produce its own tools of political transformation and a local version of modernity. Prior to this violent political moment, argues historian Benjamin Cohen, Hyderabad state had envisioned a clear break from the feudal setting to being an era of a “new Hyderabad.” From 1908 to 1948, many such developments produced an urban Muslim category, which culminated in the making of a new Muslim identity along with the “new Hyderabad” during the Police Action. Against this complex background, any discussion about Police Action, as I show in this book, was not confined to immediate violence and trauma. Despite its unsettling impact, the political event of the Police Action in many ways resulted in revisiting the Muslim question that includes an urban dimension of Muslimness and the Hindu-Muslim composite culture otherwise popularly known as the Hyderabadi tehzeeb. How do we understand these two dimensions when the very identity of Muslims was in danger during the Police Action?

Although a wave of anti-Muslim sentiment pervades many of the writings promoted by the nationalists and leftists, the question about Muslim being and belonging remains largely unanswered or buried. The Muslims of Hyderabad did indeed experience intense moments when their belonging was challenged. But the critical moment of the Police Action, which historians such as Omar Khalidi and A. G. Noorani described as the “fall of Hyderabad,” created a new dilemma. This led to an unprecedented disenchantment with the nationalist mission of the Indian government along with a fear of majoritarian political authority. Being a Muslim in this political and religious context challenged the individuals’ everyday life and survival, beginning in 1948. This book emphasizes the urgency of reading this history through the lens of Muslim belonging to understand various political and religious transformations that fashioned the everyday life of Muslims in the long 1930s and 1940s. It proposes that this historical event was a commingling of multiple aspects that had begun with the tensions between the making of the new nation and the question of Muslim representation in postcolonial India, and then extended further into the recent debates about the strategic minoritization and isolation of Muslims, particularly those in Hyderabad state. Several studies discuss this formation of the political minority of Muslims as related to the Partition of India and Pakistan.

Hyderabadi Muslims perceived the idea of azadi as, to use the Urdu novelist Jeelani Bano’s words, “a broken promise.” Most of my interlocutors of the Police Action including several cultural and political activists; both Muslims and Hindus viewed this violence as “nothing but one of the major side effects of the Partition.” Indeed, some of them said that this entire event and violence was in aid of an immediate political resolution to the Muslim question, which remains unresolved. Whereas we barely have any studies that focus on the Partition or related violence in south India, many of these oral accounts narrate how the idea of Partition and Pakistan transformed the dynamics of Hindu-Muslim everyday lives locally, even in the remotest parts of Hyderabad state.

According to many interlocutors of the Police Action, the entire Muslim community of Hyderabad state experienced deep trauma and paralysis in their everyday life, even in remote parts of the region. While many families lost their livelihood, thousands of young Muslims migrated to the city seeking refuge from the violence caused by the local police and the union army. As the Indian Civil Service Officer M. K. Vellodi remarked, “The majority of the population had resigned themselves to being alternatively beaten up by the Police, by the Army, or by the Communists. Given this deep trauma, it is understandable that the Hyderabad community was experiencing a sense of grave loss and even lost hope of receiving any outside help.”

The evidence in this book portrays manifold ways of encouraging Muslim agency at different levels of political and cultural discourse with an emphasis on how Islam and Muslimness are defined or interpreted in a local idiom— in this case, the Hyderabadi and Telangana language. Finding a voice and searching for alternative ways of reconstructing their everyday lives had positioned the community differently, rather than merely speaking as victims. In essence, the Muslims of Hyderabad, as portrayed in these oral and written sources, refuse to be depicted as victims. Instead, they rebuilt their everyday lives right from scratch by participating in a wide array of contemporary global and local progressive discourses. Many activists even now believe that Muslim voices in particular were either totally silenced or entirely marginalized by the new language produced by these ideological battles. In such a context, how do we understand the efforts made by various organizations affiliated with the Communist Party of India, and various left-affiliated trade unions and the Progressive Writers Association to restore the resilience of the Hyderabadi community?

Speaking from the perspective of a Muslim belonging, well-known progressive writers and political activists such as Makhdoom Mohiuddin also contributed to this dimension of resistance by writing and circulating booklets that discussed the Muslim question even before the Police Action took place. Many of Makhdoom’s Urdu writings and speeches were translated into Telugu and made available to the new generation of political and cultural activists during this period. In addition, several fictional writings and non-fictional works including memoirs, personal essays, and autobiographical writings likewise describe Makhdoom’s role in the making of the Telugu public sphere. Makhdoom’s 1947 essay focused on how the Nizam’s rule exploited the country’s new resources, mainly industrial and business ones. He also explained what Muslims should do against the Nizam’s policies that were bent on promoting local upper-caste landlords.? Arguing that the Nizam was nothing but a representative of British colonialism, Makhdoom called for action against the Nizam’s autocratic rule. Makhdoom’s analysis, published in Telugu, however reveals more about the status of Muslims in the state of Hyderabad and deserves some attention here. Despite his explicit leftist perspective, Makhdoom debates the marginalization of a lower-class/ poor Muslim community that, to use his words, “was being exploited by all means.” This position is similar to what I will describe in Chapter 2 where the novelists Kavi Raja Murthy and Bhaskarabhatla Krishna Rao portray the life stories of two Muslims. Murthy’s novelistic representation of a garb (the poor) and Bhaskarabhatla’s depiction of a middle-class Muslim shatter the stereotype of the Muslim navabi lifestyle. These two novels and Makhdoom’s essay published before and after the Police Action conceptualize the idea of the class, thus unpacking the discourse of a subaltern Muslim identity.

The historian Margrit Pernau’s recent study on Muslims in nineteenth-century Delhi theorizes about how the idea of class should be revisited. Pernau also points out that the “Muslim workers are hardly studied”:

“Since the 1980s and 1990s, Partition has been replaced as the central question by reflections on the origins of fundamentalism and its counter-forces. For all their differences, these studies share a tendency to assume that Muslim identity is primarily informed by religion and that the creation of a community on the basis of religion surpasses and eclipses other forms. This assumption—that the non-religious identities ludo of Muslims are only tenuous or even entirely undeveloped—probably also explains why there are relatively few studies dealing with Muslim women, workers or the Muslim middle classes, despite the flourishing of gender and social historiography in India.”

In the case of Hyderabad, Makhdoom’s essay and literary narratives including Murthy, Bhaskarabhatla, and Swamy, inform us about how even the economic status of middle-class Muslims had deteriorated essentially to that of the lower class due to a major shift in the power structures, the continuing economic hegemony of non-Muslim landlordism, and the marginalization of Muslims in the postcolonial and post-Independence government sector. These writings demonstrate that even during the Nizam’s rule, this particular section of non-Muslim landlords had control over most of the economic resources. These writings explain the process that made Muslims remove themselves from the navabi-centered lifestyle and demonstrate the growing levels of poverty among Muslims. In the process, Makhdoom also questions the version of “modernity” that the Nizam had strived to bring to the state of Hyderabad. For Makhdoom, it was nothing but an attempt to mimic Western modernity. He emphasized that this modernity was meant to promote “the economic needs of the north Indian Muslims and their newly created employment opportunities in the city.” The establishment of Osmania University, likewise, he thought, was intended to support the educational needs of those non-mulki Muslims. In contrast to this debate on the Nizam’s modernity, now I turn to another major topic–the creation of a “New Hyderabad” as a strategic site in the construction of Muslim discourse. However, I argue that this version of Hyderabad modernity has always been much more nuanced and multi-layered, and that it crosses the boundaries of class.

Methodologically, I begin with and make central to my story the oral accounts of different kinds of people, from ordinary Muslims and Hindus to specialists such as writers and political and religious activists. I show how oral and written sources have been in a conversation since the Police Action. These two key sources, I argue, operate in a dialogical space that constructed a specific sense of Muslim being and belonging in the history of Hyderabad state. This dimension led me to understand the multiple ways in which various scholars have explored the Partition by using literary sources.

The oral history accounts in this book offer evidence of the Partition-related violence and the Police Action, which some of my interviewees consider to be “nothing but another Partition when it comes to violence and separation of Muslims and Hindus.” The process of documenting oral histories was also not that simple, as many witnesses of the Police Action were reluctant to speak out. As one of the witnesses said, “it was so painful even to remember those incidents.”

Most of my interviews were conducted in three ways between 2006 and 2020: first, formal and informal conversations with ordinary Muslims and Hindus who personally witnessed the Police Action; second, unstructured and structured interviews with specialists such as writers and representatives of various literary, cultural, religious, and political organizations that had either a direct or indirect connection with various historical and political events of the 1940s; and, third, everyday conversations with various types of people from Hyderabad and different parts of Telangana state which we can categorize as conversational narratives as these people were just mentioning some aspects of the Police Action during their informal conversations. While most of the interviews with the witnesses of the Police Action were conducted in the early phase of this work around 2013, several of these conversations took enormous effort on my part as I had to wait for the interviewees to feel sufficiently safe to open up and speak freely. For some interviews, I had to return repeatedly to the interviewee’s place as they were not yet ready to speak about the violence, loss, and displacement. Hence, I have been in communication with several of these interviewees for a longer time. Many of these interviewees had lost their families and friends and had migrated to the city to escape the violence of both the government army and the private army of the Razakars. Raziya Begum, one of the witnesses, told me:

“I didn’t think at any point of my lifetime I would be able to return to those sad memories of separation and hatred. We suddenly begun to realize that we were actually in the middle of new language— the language of … hatred. Until then we were happy and our lives were peaceful, or at least, confined to our quiet homes. And, with this violence, we were on the streets fighting with each other— Muslims with Hindus, and Hindus with Muslims. And, we’re all surrounded by the troops, troops, and troops! We had never experienced such things before the Police Action.”

Several of my interviewees noticed a shift in the idiom of public language, both in Telugu and Urdu. According to Guduri Seetharam:

“It was not only about ordinary people. Even the literary idiom, too, underwent a major change. As Muslims became more conscious about being Muslims, Hindus also became more conscious about their identity. This actually created a new language in the post-Police Action writings. Added to this, the secular language that was being promoted by the nationalists and … the Congress party was also being questioned. Neither Muslims nor Hindus were owning this secular language propagated by the Congress.”

This excerpt from Remaking History: 1948 Police Action and the Muslims of Hyderabad has been carried with permission from the author and Cambridge University Press. You can buy or read more about the book by clicking on the book cover above.

Dr. Afsar Mohammed is a Senior Lecturer of Foreign Languages in the South Asian Studies department at the University of Pennsylvania, primarily focusing on Telugu. His research interests have revolved around popular Islam and shared devotional practices in South India and most recently on the Police Action in Hyderabad and the subsequent minoritisation of the Hyderabadi Muslims. In addition to the book excerpted here, he is the author of ‘The Festival of Pirs: Popular Islam and Shared Devotion in South India’.

Besides his academic pursuits, he is a celebrated Telugu poet who has published four volumes of poetry. For his contributions to Telugu poetry since 1980 he has been awarded the prestigious Indian national award “Saraswathi Bhasha Samman”. He is also known as a trend-setting literary critic whose writings on Telangana/Andhra-based Hindu-Muslim interfaces have sparked new questions and energised debates. He is the current editor of the Telugu weekly web magazine – Saranga.

You can find more on his research, poetry, and an expanded bio here.

| 2500 BC - Present | |

|

2500 BC - Present |

| Tribal History: Looking for the Origins of the Kodavas | |

| 2200 BC to 600 AD | |

|

2200 BC to 600 AD |

| War, Political Violence and Rebellion in Ancient India | |

| 400 BC to 1001 AD | |

|

400 BC to 1001 AD |

| The Dissent of the ‘Nastika’ in Early India | |

| 600CE-1200CE | |

|

600CE-1200CE |

| The Other Side of the Vindhyas: An Alternative History of Power | |

| c. 700 - 1400 AD | |

|

c. 700 - 1400 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Representing the ‘Other’ in Indian History | |

| c. 800 - 900 CE | |

|

c. 800 - 900 CE |

| ‘Drape me in his scent’: Female Sexuality and Devotion in Andal, the Goddess | |

| 1192 | |

|

1192 |

| Sufi Silsilahs: The Mystic Orders in India | |

| 1200 - 1850 | |

|

1200 - 1850 |

| Temples, deities, and the law. | |

| c. 1500 - 1600 AD | |

|

c. 1500 - 1600 AD |

| A Historian Recommends: Religion in Mughal India | |

| 1200-2020 | |

|

1200-2020 |

| Policing Untouchables and Producing Tamasha in Maharashtra | |

| 1530-1858 | |

|

1530-1858 |

| Rajputs, Mughals and the Handguns of Hindustan | |

| 1575 | |

|

1575 |

| Abdul Qadir Badauni & Abul Fazl: Two Mughal Intellectuals in King Akbar‘s Court | |

| 1579 | |

|

1579 |

| Padshah-i Islam | |

| 1550-1800 | |

|

1550-1800 |

| Who are the Bengal Muslims? : Conversion and Islamisation in Bengal | |

| c. 1600 CE-1900 CE | |

|

c. 1600 CE-1900 CE |

| The Birth of a Community: UP’s Ghazi Miyan and Narratives of ‘Conquest’ | |

| 1553 - 1900 | |

|

1553 - 1900 |

| What Happened to ‘Hindustan’? | |

| 1630-1680 | |

|

1630-1680 |

| Shivaji: Hindutva Icon or Secular Nationalist? | |

| 1630 -1680 | |

|

1630 -1680 |

| Shivaji: His Legacy & His Times | |

| c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. | |

|

c. 1724 – 1857 A.D. |

| Bahu Begum and the Gendered Struggle for Power | |

| 1818 - Present | |

|

1818 - Present |

| The Contesting Memories of Bhima-Koregaon | |

| 1831 | |

|

1831 |

| The Derozians’ India | |

| 1855 | |

|

1855 |

| Ayodhya 1855 | |

| 1856 | |

|

1856 |

| “Worshipping the dead is not an auspicious thing” — Ghalib | |

| 1857 | |

|

1857 |

| A Subaltern speaks: Dalit women’s counter-history of 1857 | |

| 1858 - 1976 | |

|

1858 - 1976 |

| Lifestyle as Resistance: The Curious Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow | |

| 1883 - 1894 | |

|

1883 - 1894 |

| The Sea Voyage Question: A Nineteenth century Debate | |

| 1887 | |

|

1887 |

| The Great Debaters: Tilak Vs. Agarkar | |

| 1893-1946 | |

|

1893-1946 |

| A Historian Recommends: Gandhi Vs. Caste | |

| 1897 | |

|

1897 |

| Queen Empress vs. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: An Autopsy | |

| 1913 - 1916 Modern Review | |

|

1913 - 1916 |

| A Young Ambedkar in New York | |

| 1916 | |

|

1916 |

| A Rare Account of World War I by an Indian Soldier | |

| 1917 | |

|

1917 |

| On Nationalism, by Tagore | |

| 1918 - 1919 | |

|

1918 - 1919 |

| What Happened to the Virus That Caused the World’s Deadliest Pandemic? | |

| 1920 - 1947 | |

|

1920 - 1947 |

| How One Should Celebrate Diwali, According to Gandhi | |

| 1921 | |

|

1921 |

| Great Debates: Tagore Vs. Gandhi (1921) | |

| 1921 - 2015 | |

|

1921 - 2015 |

| A History of Caste Politics and Elections in Bihar | |

| 1915-1921 | |

|

1915-1921 |

| The Satirical Genius of Gaganendranath Tagore | |

| 1924-1937 | |

|

1924-1937 |

| What were Gandhi’s Views on Religious Conversion? | |

| 1900-1950 | |

|

1900-1950 |

| Gazing at the Woman’s Body: Historicising Lust and Lechery in a Patriarchal Society | |

| 1925, 1926 | |

|

1925, 1926 |

| Great Debates: Tagore vs Gandhi (1925-1926) | |

| 1928 | |

|

1928 |

| Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose? | |

| 1930 Modern Review | |

|

1930 |

| The Modern Review Special: On the Nature of Reality | |

| 1932 | |

|

1932 |

| Caste, Gandhi and the Man Beside Gandhi | |

| 1933 - 1991 | |

|

1933 - 1991 |

| Raghubir Sinh: The Prince Who Would Be Historian | |

| 1935 | |

|

1935 |

| A Historian Recommends: SA Khan’s Timeless Presidential Address | |

| 1865-1928 | |

|

1865-1928 |

| Understanding Lajpat Rai’s Hindu Politics and Secularism | |

| 1935 Modern Review | |

|

1935 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Mind of a Judge | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: When Netaji Subhas Bose Was Wrongfully Detained for ‘Terrorism’ | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 1 | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: An Indian MP in the British Parliament | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| Annihilation of Caste: Part 2 | |

| 1936 | |

|

1936 |

| A Reflection of His Age: Munshi Premchand on the True Purpose of Literature | |

| 1936 Modern Review | |

|

1936 |

| The Modern Review Special: The Defeat of a Dalit Candidate in a 1936 Municipal Election | |

| 1937 Modern Review | |

|

1937 |

| The Modern Review Special: Rashtrapati | |

| 1938 | |

|

1938 |

| Great Debates: Nehru Vs. Jinnah (1938) | |

| 1942 Modern Review | |

|

1942 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government In British India (Part 1) | |

| 1943-1945 | |

|

1943-1945 |

| Origin Of The Azad Hind Fauj | |

| 1942-1945 | |

|

1942-1945 |

| IHC Uncovers: A Parallel Government in British India (Part 2) | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| Our Last War of Independence: The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 | |

| 1946 | |

|

1946 |

| An Artist’s Account of the Tebhaga Movement in Pictures And Prose | |

| 1946 – 1947 | |

|

1946 – 1947 |

| “The Most Democratic People on Earth” : An Adivasi Voice in the Constituent Assembly | |

| 1946-1947 | |

|

1946-1947 |

| VP Menon and the Birth of Independent India | |

| 1916 - 1947 | |

|

1916 - 1947 |

| 8 @ 75: 8 Speeches Independent Indians Must Read | |

| 1947-1951 | |

|

1947-1951 |

| Ambedkar Cartoons: The Joke’s On Us | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| “My Father, Do Not Rest” | |

| 1940-1960 | |

|

1940-1960 |

| Integration Myth: A Silenced History of Hyderabad | |

| 1948 | |

|

1948 |

| The Assassination of a Mahatma, the Princely States and the ‘Hindu’ Nation | |

| 1949 | |

|

1949 |

| Ambedkar warns against India becoming a ‘Democracy in Form, Dictatorship in Fact’ | |

| 1950 | |

|

1950 |

| Illustrations from the constitution | |

| 1951 | |

|

1951 |

| How the First Amendment to the Indian Constitution Circumscribed Our Freedoms & How it was Passed | |

| 1967 | |

|

1967 |

| Once Upon A Time In Naxalbari | |

| 1970 | |

|

1970 |

| R.C. Majumdar on Shortcomings in Indian Historiography | |

| 1973 - 1993 | |

|

1973 - 1993 |

| Balasaheb Deoras: Kingmaker of the Sangh | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: Shadow Power | |

| 1975 | |

|

1975 |

| The Emergency Package: The Prehistory of Turkman Gate – Population Control | |

| 1977 – 2011 | |

|

1977 – 2011 |

| Power is an Unforgiving Mistress: Lessons from the Decline of the Left in Bengal | |

| 1984 | |

|

1984 |

| Mrs Gandhi’s Final Folly: Operation Blue Star | |

| 1916-2004 | |

|

1916-2004 |

| Amjad Ali Khan on M.S. Subbulakshmi: “A Glorious Chapter for Indian Classical Music” | |

| 2008 | |

|

2008 |

| Whose History Textbook Is It Anyway? | |

| 2006 - 2009 | |

|

2006 - 2009 |

| Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh: Movements that Remade Mamata Banerjee | |

| 2020 | |

|

2020 |

| The Indo-China Conflict: 10 Books We Need To Read | |

| 2021 | |

|

2021 |

| Singing/Writing Liberation: Dalit Women’s Narratives | |

Leave a Reply